User login

62-year-old woman • dysuria • dyspareunia • urinary incontinence • Dx?

THE CASE

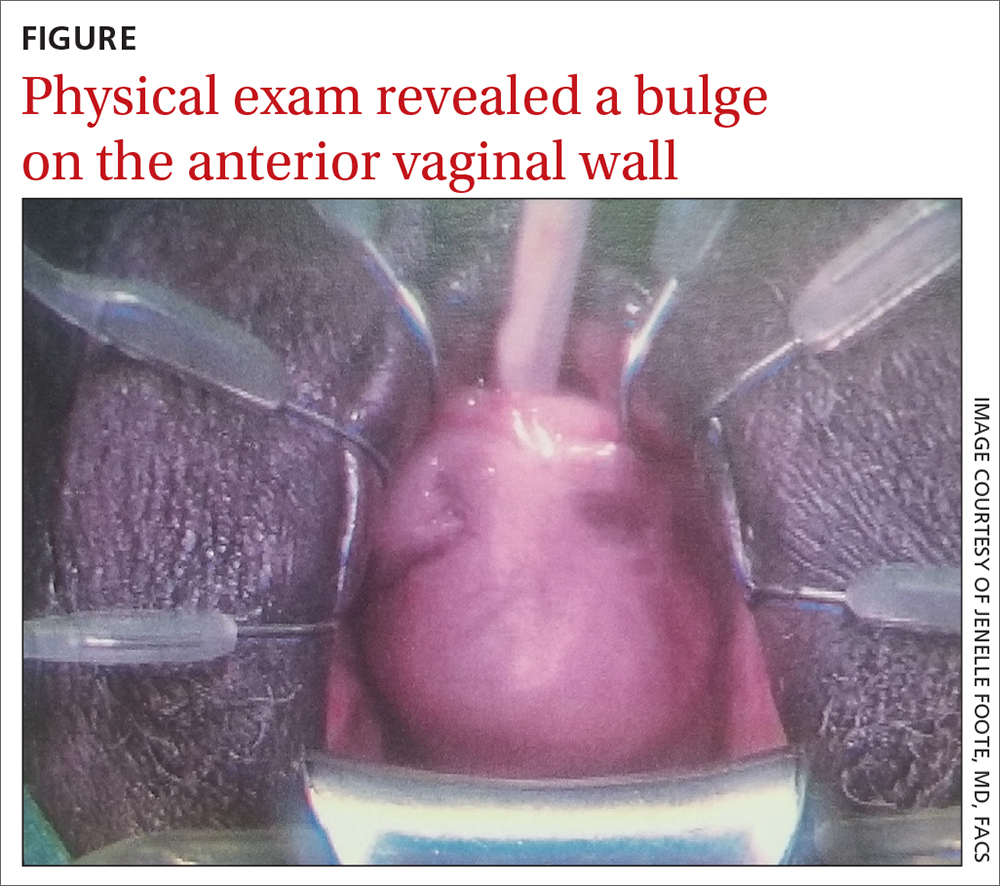

A 62-year-old postmenopausal woman presented to the clinic as a new patient for her annual physical examination. She reported a 9-year history of symptoms including dysuria, post-void dribbling, dyspareunia, and urinary incontinence on review of systems. Her physical examination revealed an anterior vaginal wall bulge (FIGURE). Results of a urinalysis were negative. The patient was referred to Urology for further evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large periurethral diverticulum with a horseshoe shape.

DISCUSSION

Women are more likely than men to develop urethral diverticulum, and it can manifest at any age, usually in the third through seventh decade.4,5 It was once thought to be more common in Black women, although the literature does not support this.6 Black women are 3 times more likely to be operated on than White women to treat urethral diverticula.7

Unknown origin. Most cases of urethral diverticulum are acquired; the etiology is uncertain.8,9 The assumption is that urethral diverticulum occurs as a result of repeated infection of the periurethral glands with subsequent obstruction, abscess formation, and chronic inflammation.1,2,4 Childbirth trauma, iatrogenic causes, and urethral instrumentation have also been implicated.3,4 In rare cases of congenital urethral diverticula, the diverticula are thought to be remnants of Gartner duct cysts, and yet, incidence in the pediatric population is low.8

Diagnosis is confirmed through physical exam and imaging

The urethral diverticulum manifests anteriorly and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall may reveal a painful mass.10 A split-speculum is used for careful inspection and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall.9 If the diverticulum is found to be firm on palpation, or there is bloody urethral drainage, malignancy (although rare) must be ruled out.4,5 Refer such patients to a urologist or urogynecologist.

Radiologic imaging (eg, ultrasound,

Continue to: Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis

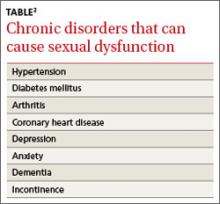

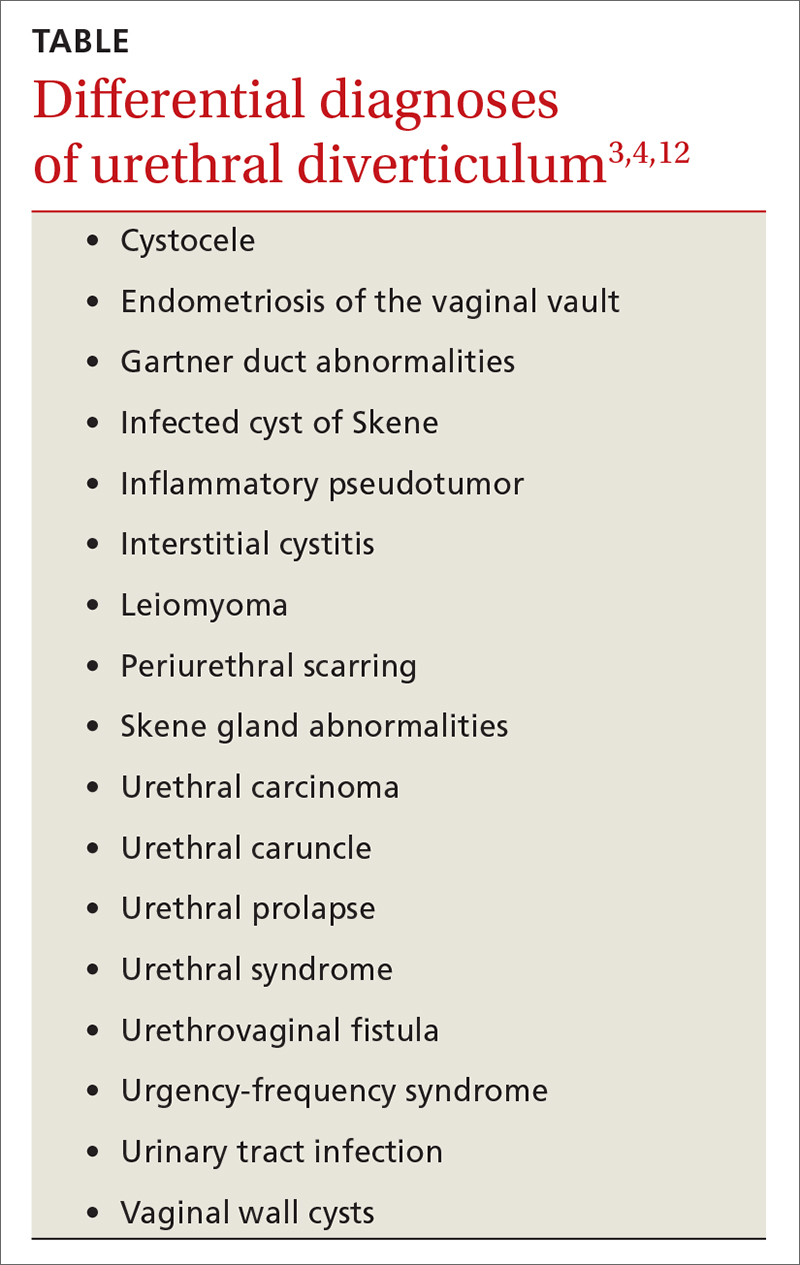

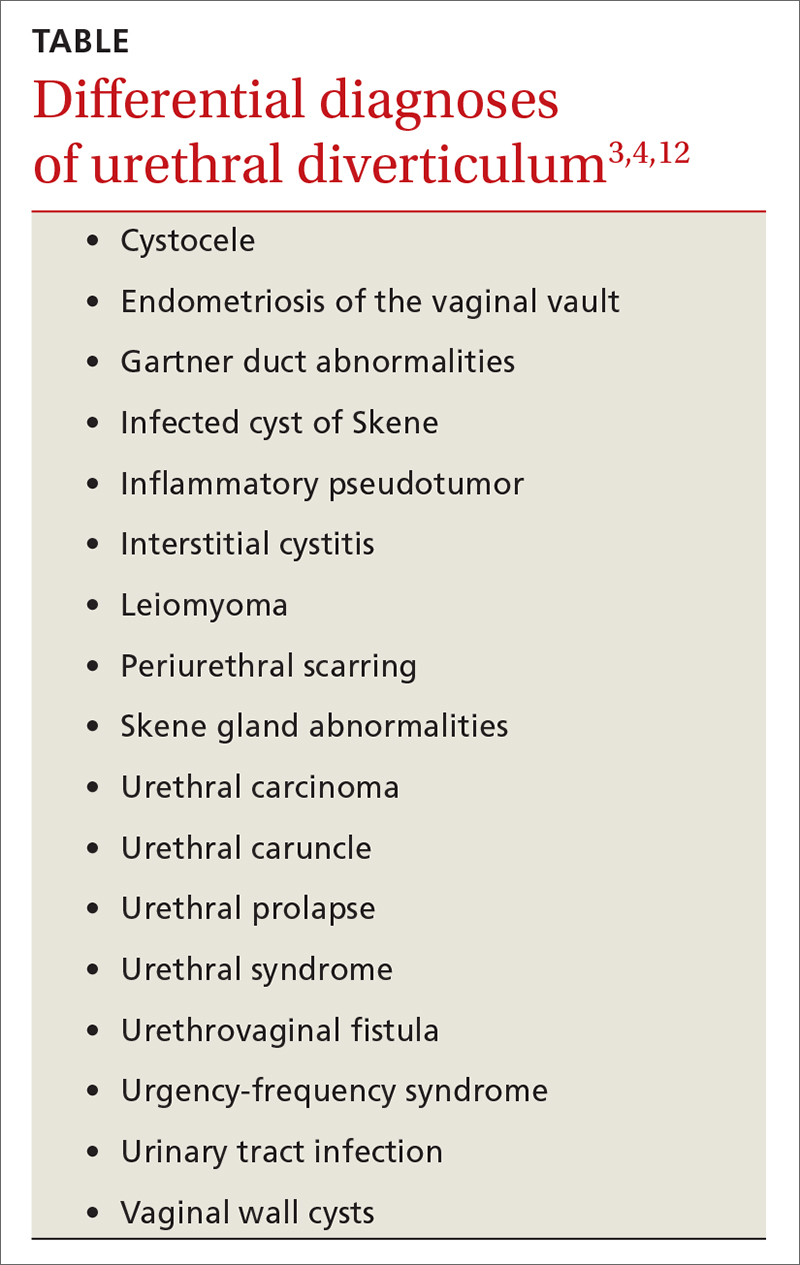

Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis. The symptoms associated with urethral diverticulum are diverse and linked to several differential diagnoses (TABLE).3,4,12 The most common signs and symptoms are pelvic pain, urethral mass, dyspareunia, dysuria, urinary incontinence, and post-void dribbling—all of which are considered nonspecific.3,10,11 These nonspecific symptoms (or even an absence of symptoms), along with a physician’s lack of familiarity with urethral diverticulum, can result in a misdiagnosis or even a delayed diagnosis (up to 5.2 years).3,10

Managing symptoms vs preventing recurrence

Conservative management with antibiotics, anticholinergics, and/or observation is acceptable for patients with mild symptoms and those who are pregnant or who have a current infection or serious comorbidities that preclude surgery.3,9 Complete excision of the urethral diverticulum with reconstruction is considered the most effective surgical management for symptom relief and recurrence prevention.3,4,11,14

Our patient underwent a successful transvaginal suburethral diverticulectomy.

THE TAKEAWAY

The diagnosis of female urethral diverticulum is often delayed or misdiagnosed because symptoms are diverse and nonspecific. One should have a high degree of suspicion for urethral diverticulum in patients with dysuria, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, and irritative voiding symptoms who are not responding to conservative management. Ultrasound is an appropriate first-line imaging modality. However, a pelvic MRI is the most sensitive and specific in diagnosing urethral diverticulum.12

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 720 Westview Drive, Atlanta, GA 30310; fomole@msm.edu

1. Billow M, James R, Resnick K, et al. An unusual presentation of a urethral diverticulum as a vaginal wall mass: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:171. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-171

2. El-Nashar SA, Bacon MM, Kim-Fine S, et al. Incidence of female urethral diverticulum: a population-based analysis and literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:73-79. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2155-2

3. Cameron AP. Urethral diverticulum in the female: a meta-analysis of modern series. Minerva Ginecol. 2016;68:186-210.

4. Greiman AK, Rolef J, Rovner ES. Urethral diverticulum: a systematic review. Arab J Urol. 2019;17:49-57. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2019.1589748

5. Allen D, Mishra V, Pepper W, et al. A single-center experience of symptomatic male urethral diverticula. Urology. 2007;70:650-653. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1111

6. O’Connor E, Iatropoulou D, Hashimoto S, et al. Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females—a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:703-729. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.07.08

7. Burrows LJ, Howden NL, Meyn L, et al. Surgical procedures for urethral diverticula in women in the United States, 1979-1997. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:158-161. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1145-9

8. Riyach O, Ahsaini M, Tazi MF, et al. Female urethral diverticulum: cases report and literature. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2014;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-8-1

9. Antosh DD, Gutman RE. Diagnosis and management of female urethral diverticulum. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:264-271. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318234a242

10. Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. J Urol. 2000;164:428-433.

11. Reeves FA, Inman RD, Chapple CR. Management of symptomatic urethral diverticula in women: a single-centre experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:164-172. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.041

12. Dwarkasing RS, Dinkelaar W, Hop WCJ, et al. MRI evaluation of urethral diverticula and differential diagnosis in symptomatic women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:676-682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6144

13. Porten S, Kielb S. Diagnosis of female diverticula using magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Urol. 2008;2008:213516. doi: 10.1155/2008/213516

14. Ockrim JL, Allen DJ, Shah PJ, et al. A tertiary experience of urethral diverticulectomy: diagnosis, imaging and surgical outcomes. BJU Int. 2009;103:1550-1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08348.x

THE CASE

A 62-year-old postmenopausal woman presented to the clinic as a new patient for her annual physical examination. She reported a 9-year history of symptoms including dysuria, post-void dribbling, dyspareunia, and urinary incontinence on review of systems. Her physical examination revealed an anterior vaginal wall bulge (FIGURE). Results of a urinalysis were negative. The patient was referred to Urology for further evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large periurethral diverticulum with a horseshoe shape.

DISCUSSION

Women are more likely than men to develop urethral diverticulum, and it can manifest at any age, usually in the third through seventh decade.4,5 It was once thought to be more common in Black women, although the literature does not support this.6 Black women are 3 times more likely to be operated on than White women to treat urethral diverticula.7

Unknown origin. Most cases of urethral diverticulum are acquired; the etiology is uncertain.8,9 The assumption is that urethral diverticulum occurs as a result of repeated infection of the periurethral glands with subsequent obstruction, abscess formation, and chronic inflammation.1,2,4 Childbirth trauma, iatrogenic causes, and urethral instrumentation have also been implicated.3,4 In rare cases of congenital urethral diverticula, the diverticula are thought to be remnants of Gartner duct cysts, and yet, incidence in the pediatric population is low.8

Diagnosis is confirmed through physical exam and imaging

The urethral diverticulum manifests anteriorly and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall may reveal a painful mass.10 A split-speculum is used for careful inspection and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall.9 If the diverticulum is found to be firm on palpation, or there is bloody urethral drainage, malignancy (although rare) must be ruled out.4,5 Refer such patients to a urologist or urogynecologist.

Radiologic imaging (eg, ultrasound,

Continue to: Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis

Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis. The symptoms associated with urethral diverticulum are diverse and linked to several differential diagnoses (TABLE).3,4,12 The most common signs and symptoms are pelvic pain, urethral mass, dyspareunia, dysuria, urinary incontinence, and post-void dribbling—all of which are considered nonspecific.3,10,11 These nonspecific symptoms (or even an absence of symptoms), along with a physician’s lack of familiarity with urethral diverticulum, can result in a misdiagnosis or even a delayed diagnosis (up to 5.2 years).3,10

Managing symptoms vs preventing recurrence

Conservative management with antibiotics, anticholinergics, and/or observation is acceptable for patients with mild symptoms and those who are pregnant or who have a current infection or serious comorbidities that preclude surgery.3,9 Complete excision of the urethral diverticulum with reconstruction is considered the most effective surgical management for symptom relief and recurrence prevention.3,4,11,14

Our patient underwent a successful transvaginal suburethral diverticulectomy.

THE TAKEAWAY

The diagnosis of female urethral diverticulum is often delayed or misdiagnosed because symptoms are diverse and nonspecific. One should have a high degree of suspicion for urethral diverticulum in patients with dysuria, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, and irritative voiding symptoms who are not responding to conservative management. Ultrasound is an appropriate first-line imaging modality. However, a pelvic MRI is the most sensitive and specific in diagnosing urethral diverticulum.12

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 720 Westview Drive, Atlanta, GA 30310; fomole@msm.edu

THE CASE

A 62-year-old postmenopausal woman presented to the clinic as a new patient for her annual physical examination. She reported a 9-year history of symptoms including dysuria, post-void dribbling, dyspareunia, and urinary incontinence on review of systems. Her physical examination revealed an anterior vaginal wall bulge (FIGURE). Results of a urinalysis were negative. The patient was referred to Urology for further evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large periurethral diverticulum with a horseshoe shape.

DISCUSSION

Women are more likely than men to develop urethral diverticulum, and it can manifest at any age, usually in the third through seventh decade.4,5 It was once thought to be more common in Black women, although the literature does not support this.6 Black women are 3 times more likely to be operated on than White women to treat urethral diverticula.7

Unknown origin. Most cases of urethral diverticulum are acquired; the etiology is uncertain.8,9 The assumption is that urethral diverticulum occurs as a result of repeated infection of the periurethral glands with subsequent obstruction, abscess formation, and chronic inflammation.1,2,4 Childbirth trauma, iatrogenic causes, and urethral instrumentation have also been implicated.3,4 In rare cases of congenital urethral diverticula, the diverticula are thought to be remnants of Gartner duct cysts, and yet, incidence in the pediatric population is low.8

Diagnosis is confirmed through physical exam and imaging

The urethral diverticulum manifests anteriorly and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall may reveal a painful mass.10 A split-speculum is used for careful inspection and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall.9 If the diverticulum is found to be firm on palpation, or there is bloody urethral drainage, malignancy (although rare) must be ruled out.4,5 Refer such patients to a urologist or urogynecologist.

Radiologic imaging (eg, ultrasound,

Continue to: Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis

Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis. The symptoms associated with urethral diverticulum are diverse and linked to several differential diagnoses (TABLE).3,4,12 The most common signs and symptoms are pelvic pain, urethral mass, dyspareunia, dysuria, urinary incontinence, and post-void dribbling—all of which are considered nonspecific.3,10,11 These nonspecific symptoms (or even an absence of symptoms), along with a physician’s lack of familiarity with urethral diverticulum, can result in a misdiagnosis or even a delayed diagnosis (up to 5.2 years).3,10

Managing symptoms vs preventing recurrence

Conservative management with antibiotics, anticholinergics, and/or observation is acceptable for patients with mild symptoms and those who are pregnant or who have a current infection or serious comorbidities that preclude surgery.3,9 Complete excision of the urethral diverticulum with reconstruction is considered the most effective surgical management for symptom relief and recurrence prevention.3,4,11,14

Our patient underwent a successful transvaginal suburethral diverticulectomy.

THE TAKEAWAY

The diagnosis of female urethral diverticulum is often delayed or misdiagnosed because symptoms are diverse and nonspecific. One should have a high degree of suspicion for urethral diverticulum in patients with dysuria, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, and irritative voiding symptoms who are not responding to conservative management. Ultrasound is an appropriate first-line imaging modality. However, a pelvic MRI is the most sensitive and specific in diagnosing urethral diverticulum.12

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 720 Westview Drive, Atlanta, GA 30310; fomole@msm.edu

1. Billow M, James R, Resnick K, et al. An unusual presentation of a urethral diverticulum as a vaginal wall mass: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:171. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-171

2. El-Nashar SA, Bacon MM, Kim-Fine S, et al. Incidence of female urethral diverticulum: a population-based analysis and literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:73-79. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2155-2

3. Cameron AP. Urethral diverticulum in the female: a meta-analysis of modern series. Minerva Ginecol. 2016;68:186-210.

4. Greiman AK, Rolef J, Rovner ES. Urethral diverticulum: a systematic review. Arab J Urol. 2019;17:49-57. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2019.1589748

5. Allen D, Mishra V, Pepper W, et al. A single-center experience of symptomatic male urethral diverticula. Urology. 2007;70:650-653. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1111

6. O’Connor E, Iatropoulou D, Hashimoto S, et al. Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females—a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:703-729. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.07.08

7. Burrows LJ, Howden NL, Meyn L, et al. Surgical procedures for urethral diverticula in women in the United States, 1979-1997. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:158-161. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1145-9

8. Riyach O, Ahsaini M, Tazi MF, et al. Female urethral diverticulum: cases report and literature. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2014;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-8-1

9. Antosh DD, Gutman RE. Diagnosis and management of female urethral diverticulum. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:264-271. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318234a242

10. Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. J Urol. 2000;164:428-433.

11. Reeves FA, Inman RD, Chapple CR. Management of symptomatic urethral diverticula in women: a single-centre experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:164-172. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.041

12. Dwarkasing RS, Dinkelaar W, Hop WCJ, et al. MRI evaluation of urethral diverticula and differential diagnosis in symptomatic women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:676-682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6144

13. Porten S, Kielb S. Diagnosis of female diverticula using magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Urol. 2008;2008:213516. doi: 10.1155/2008/213516

14. Ockrim JL, Allen DJ, Shah PJ, et al. A tertiary experience of urethral diverticulectomy: diagnosis, imaging and surgical outcomes. BJU Int. 2009;103:1550-1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08348.x

1. Billow M, James R, Resnick K, et al. An unusual presentation of a urethral diverticulum as a vaginal wall mass: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:171. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-171

2. El-Nashar SA, Bacon MM, Kim-Fine S, et al. Incidence of female urethral diverticulum: a population-based analysis and literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:73-79. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2155-2

3. Cameron AP. Urethral diverticulum in the female: a meta-analysis of modern series. Minerva Ginecol. 2016;68:186-210.

4. Greiman AK, Rolef J, Rovner ES. Urethral diverticulum: a systematic review. Arab J Urol. 2019;17:49-57. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2019.1589748

5. Allen D, Mishra V, Pepper W, et al. A single-center experience of symptomatic male urethral diverticula. Urology. 2007;70:650-653. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1111

6. O’Connor E, Iatropoulou D, Hashimoto S, et al. Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females—a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:703-729. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.07.08

7. Burrows LJ, Howden NL, Meyn L, et al. Surgical procedures for urethral diverticula in women in the United States, 1979-1997. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:158-161. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1145-9

8. Riyach O, Ahsaini M, Tazi MF, et al. Female urethral diverticulum: cases report and literature. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2014;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-8-1

9. Antosh DD, Gutman RE. Diagnosis and management of female urethral diverticulum. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:264-271. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318234a242

10. Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. J Urol. 2000;164:428-433.

11. Reeves FA, Inman RD, Chapple CR. Management of symptomatic urethral diverticula in women: a single-centre experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:164-172. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.041

12. Dwarkasing RS, Dinkelaar W, Hop WCJ, et al. MRI evaluation of urethral diverticula and differential diagnosis in symptomatic women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:676-682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6144

13. Porten S, Kielb S. Diagnosis of female diverticula using magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Urol. 2008;2008:213516. doi: 10.1155/2008/213516

14. Ockrim JL, Allen DJ, Shah PJ, et al. A tertiary experience of urethral diverticulectomy: diagnosis, imaging and surgical outcomes. BJU Int. 2009;103:1550-1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08348.x

Spirituality can play a role in treating depression

We would like to commend Larzelere et al on their article, “Treating depression: What works besides meds?” (J Fam Pract. 2015;64:454-459). These authors pointed out that the value of medications is limited in patients with mild to moderate depression. They also noted that nonpharmacologic interventions have proven beneficial and that, specifically, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and problem-solving therapy have been linked to moderate to large improvements in depressive symptoms. We agree, and would also like to highlight the role of religion and spirituality in the context of CBT as a valuable treatment for depression.

Religion/spirituality is a protective factor against depression and has been proven to be beneficial in patients with mild to moderate depression.1,2,3 In a randomized clinical trial that compared CBT that incorporated patients’ religion vs conventional CBT, Koenig et al found that religious and conventional CBT were equally effective in increasing optimism in patients with major depressive disorder and chronic medical illness.1

Afolake Mobolaji, MD

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP

Atlanta, Ga

1. Koenig HG, Pearce MJ, Nelson B, et al. Effects of religious versus standard cognitive-behavioral therapy on optimism in persons with major depression and chronic medical illness. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:835-842.

2. Miller L. Spiritual awakening and depression in adolescents: a unified pathway or “two sides of the same coin.” Bull Menninger Clin. 2013;77:332-348.

3. Balbuena L, Baetz M, Bowen R. Religious attendance, spirituality, and major depression in Canada: a 14-year follow-up study. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:225-232.

We would like to commend Larzelere et al on their article, “Treating depression: What works besides meds?” (J Fam Pract. 2015;64:454-459). These authors pointed out that the value of medications is limited in patients with mild to moderate depression. They also noted that nonpharmacologic interventions have proven beneficial and that, specifically, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and problem-solving therapy have been linked to moderate to large improvements in depressive symptoms. We agree, and would also like to highlight the role of religion and spirituality in the context of CBT as a valuable treatment for depression.

Religion/spirituality is a protective factor against depression and has been proven to be beneficial in patients with mild to moderate depression.1,2,3 In a randomized clinical trial that compared CBT that incorporated patients’ religion vs conventional CBT, Koenig et al found that religious and conventional CBT were equally effective in increasing optimism in patients with major depressive disorder and chronic medical illness.1

Afolake Mobolaji, MD

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP

Atlanta, Ga

1. Koenig HG, Pearce MJ, Nelson B, et al. Effects of religious versus standard cognitive-behavioral therapy on optimism in persons with major depression and chronic medical illness. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:835-842.

2. Miller L. Spiritual awakening and depression in adolescents: a unified pathway or “two sides of the same coin.” Bull Menninger Clin. 2013;77:332-348.

3. Balbuena L, Baetz M, Bowen R. Religious attendance, spirituality, and major depression in Canada: a 14-year follow-up study. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:225-232.

We would like to commend Larzelere et al on their article, “Treating depression: What works besides meds?” (J Fam Pract. 2015;64:454-459). These authors pointed out that the value of medications is limited in patients with mild to moderate depression. They also noted that nonpharmacologic interventions have proven beneficial and that, specifically, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and problem-solving therapy have been linked to moderate to large improvements in depressive symptoms. We agree, and would also like to highlight the role of religion and spirituality in the context of CBT as a valuable treatment for depression.

Religion/spirituality is a protective factor against depression and has been proven to be beneficial in patients with mild to moderate depression.1,2,3 In a randomized clinical trial that compared CBT that incorporated patients’ religion vs conventional CBT, Koenig et al found that religious and conventional CBT were equally effective in increasing optimism in patients with major depressive disorder and chronic medical illness.1

Afolake Mobolaji, MD

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP

Atlanta, Ga

1. Koenig HG, Pearce MJ, Nelson B, et al. Effects of religious versus standard cognitive-behavioral therapy on optimism in persons with major depression and chronic medical illness. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:835-842.

2. Miller L. Spiritual awakening and depression in adolescents: a unified pathway or “two sides of the same coin.” Bull Menninger Clin. 2013;77:332-348.

3. Balbuena L, Baetz M, Bowen R. Religious attendance, spirituality, and major depression in Canada: a 14-year follow-up study. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:225-232.

Headache • fatigue • blurred vision • Dx?

THE CASE

One month after moving into her mother’s apartment, a 27-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for fatigue, headache, blurred vision, nausea, and morning vomiting. She had weakness and difficulty sleeping, but denied any fever, rashes, neck stiffness, recent travel, trauma, or tobacco or illicit drug use. She did, however, have a 6-year history of migraines. Her physical exam was normal. She was sent home with a prescription for tramadol 50 mg bid for her headaches.

The patient subsequently went to the emergency department 3 times for the same complaints; none of the treatments she received there (mostly acetaminophen with codeine) relieved her symptoms. Three weeks later she returned to our clinic. She was distressed that the symptoms hadn’t gone away, and noted that her family was now experiencing similar symptoms.

Her temperature was 98.1°F (36.7°C), blood pressure was 131/88 mm Hg, pulse was 85 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min. Physical and neurologic exams were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Although most of the patient’s lab test results were within normal ranges, her carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) level was 4.2%. COHb levels of >2% to 3% in nonsmokers or >9% to 10% in smokers suggest carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning.1,2 Based on this finding and our patient’s symptoms, we diagnosed unintentional CO poisoning. We recommended that she and her mother vacate the apartment and have it inspected.

DISCUSSION

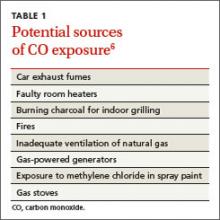

CO is the leading cause of poisoning mortality in the United States, and causes half of all fatal poisonings worldwide.1,3,4 It is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas that is produced by the incomplete combustion of carbon-based products, such as coal or gas.5,6 Exposure can occur from car exhaust fumes, faulty room heaters, and other sources (TABLE 1).6 The incidence of CO poisoning is higher during the winter months and after natural disasters. Individuals who have a lowered oxygen capacity, such as older adults, pregnant women (and their fetuses), infants, and patients with anemia, cardiovascular disease, or cerebrovascular disease, are more susceptible to CO poisoning.5,6

COHb, a stable complex of CO that forms in red blood cells when CO is inhaled, impairs oxygen delivery and peripheral utilization, resulting in cellular hypoxia.1 Signs and symptoms of CO poisoning are nonspecific and require a high degree of clinical suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment. Although cherry-red lips, peripheral cyanosis, and retinal hemorrhages are often described as “classic” symptoms of CO poisoning, these are rarely seen.6 The most common symptoms are actually headache (90%), dizziness (82%), and weakness (53%).7 Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, confusion, visual disturbances, loss of consciousness, angina, seizure, and fatigue.6,7 Symptoms of chronic CO poisoning may differ from those of acute poisoning and can include chronic fatigue, neuropathy, and memory deficit.8

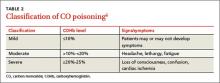

The differential diagnosis for CO poisoning includes flu-like syndrome/influenza/other viral illnesses, migraine or tension headaches, depression, transient ischemic attack, encephalitis, coronary artery disease, gastroenteritis or food poisoning, seizures, and dysrhythmias.1,4 Lab testing for COHb can help narrow the diagnosis. CO poisoning can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on COHb levels and the patient’s signs and symptoms (TABLE 2).6 However, COHb level is a poor predictor of clinical presentation and should not be used to dictate management.2,7

Oxygen therapy is the recommended treatment

Early treatment with supplemental oxygen is recommended to reduce the length of time red blood cells are exposed to CO.1 A COHb level >25% is the criterion for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.1,3 Patients should receive treatment until their symptoms become less intense.

Delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae (DNS) can occur in up to one-third of patients with acute CO poisoning more than a month after apparent recovery.1,6,9 DNS symptoms include cognitive changes, emotional lability, visual disturbances, disorientation, depression, dementia, psychotic behavior, parkinsonism, amnesia, and incontinence.1,6,9 Approximately 50% to 75% of patients with DNS recover spontaneously within a year with symptomatic treatment.1,6,9

Our patient

After recommending that our patient (and her mother) leave the apartment and have it inspected, we later learned that the fire department was unable to determine the source of the CO. A CO detector was installed and our patient was advised to keep the windows in the apartment open to allow for adequate oxygen flow. One month later she returned to our clinic and reported that her symptoms resolved; serum COHb was negative upon repeat lab tests.

THE TAKEAWAY

Patients who present with headaches, dizziness and/or fatigue should be evaluated for CO poisoning. The patient’s environmental history should be reviewed carefully, especially because CO poisoning is more common during the winter months. Oxygen therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Up to one-third of patients with acute poisoning may develop delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae, including cognitive changes, emotional lability, visual disturbances, disorientation, and depression, that may resolve within one year.

1. Nikkanen H, Skolnik A. Diagnosis and management of carbon monoxide poisoning in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2011;13:1-14.

2. Hampson NB, Hauff NM. Carboxyhemoglobin levels in carbon monoxide poisoning: do they correlate with the clinical picture? Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:665-669.

3. Kao LW, Nañagas KA. Toxicity associated with carbon monoxide. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:99-125.

4. Varon J, Marik PE, Fromm RE Jr, et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning: a review for clinicians. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:87-93.

5. Harper A, Croft-Baker J. Carbon monoxide poisoning: undetected by both patients and their doctors. Age Ageing. 2004;33:105-109.

6. Smollin C, Olson K. Carbon monoxide poisoning (acute). BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010. pii:2103.

7. Wright J. Chronic and occult carbon monoxide poisoning: we don’t know what we’re missing. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:366-390.

8. Weaver LK. Clinical practice. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1217-1225.

9. Bhatia R, Chacko F, Lal V, et al. Reversible delayed neuropsychiatric syndrome following acute carbon monoxide exposure. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2007;11:80-82.

THE CASE

One month after moving into her mother’s apartment, a 27-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for fatigue, headache, blurred vision, nausea, and morning vomiting. She had weakness and difficulty sleeping, but denied any fever, rashes, neck stiffness, recent travel, trauma, or tobacco or illicit drug use. She did, however, have a 6-year history of migraines. Her physical exam was normal. She was sent home with a prescription for tramadol 50 mg bid for her headaches.

The patient subsequently went to the emergency department 3 times for the same complaints; none of the treatments she received there (mostly acetaminophen with codeine) relieved her symptoms. Three weeks later she returned to our clinic. She was distressed that the symptoms hadn’t gone away, and noted that her family was now experiencing similar symptoms.

Her temperature was 98.1°F (36.7°C), blood pressure was 131/88 mm Hg, pulse was 85 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min. Physical and neurologic exams were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Although most of the patient’s lab test results were within normal ranges, her carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) level was 4.2%. COHb levels of >2% to 3% in nonsmokers or >9% to 10% in smokers suggest carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning.1,2 Based on this finding and our patient’s symptoms, we diagnosed unintentional CO poisoning. We recommended that she and her mother vacate the apartment and have it inspected.

DISCUSSION

CO is the leading cause of poisoning mortality in the United States, and causes half of all fatal poisonings worldwide.1,3,4 It is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas that is produced by the incomplete combustion of carbon-based products, such as coal or gas.5,6 Exposure can occur from car exhaust fumes, faulty room heaters, and other sources (TABLE 1).6 The incidence of CO poisoning is higher during the winter months and after natural disasters. Individuals who have a lowered oxygen capacity, such as older adults, pregnant women (and their fetuses), infants, and patients with anemia, cardiovascular disease, or cerebrovascular disease, are more susceptible to CO poisoning.5,6

COHb, a stable complex of CO that forms in red blood cells when CO is inhaled, impairs oxygen delivery and peripheral utilization, resulting in cellular hypoxia.1 Signs and symptoms of CO poisoning are nonspecific and require a high degree of clinical suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment. Although cherry-red lips, peripheral cyanosis, and retinal hemorrhages are often described as “classic” symptoms of CO poisoning, these are rarely seen.6 The most common symptoms are actually headache (90%), dizziness (82%), and weakness (53%).7 Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, confusion, visual disturbances, loss of consciousness, angina, seizure, and fatigue.6,7 Symptoms of chronic CO poisoning may differ from those of acute poisoning and can include chronic fatigue, neuropathy, and memory deficit.8

The differential diagnosis for CO poisoning includes flu-like syndrome/influenza/other viral illnesses, migraine or tension headaches, depression, transient ischemic attack, encephalitis, coronary artery disease, gastroenteritis or food poisoning, seizures, and dysrhythmias.1,4 Lab testing for COHb can help narrow the diagnosis. CO poisoning can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on COHb levels and the patient’s signs and symptoms (TABLE 2).6 However, COHb level is a poor predictor of clinical presentation and should not be used to dictate management.2,7

Oxygen therapy is the recommended treatment

Early treatment with supplemental oxygen is recommended to reduce the length of time red blood cells are exposed to CO.1 A COHb level >25% is the criterion for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.1,3 Patients should receive treatment until their symptoms become less intense.

Delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae (DNS) can occur in up to one-third of patients with acute CO poisoning more than a month after apparent recovery.1,6,9 DNS symptoms include cognitive changes, emotional lability, visual disturbances, disorientation, depression, dementia, psychotic behavior, parkinsonism, amnesia, and incontinence.1,6,9 Approximately 50% to 75% of patients with DNS recover spontaneously within a year with symptomatic treatment.1,6,9

Our patient

After recommending that our patient (and her mother) leave the apartment and have it inspected, we later learned that the fire department was unable to determine the source of the CO. A CO detector was installed and our patient was advised to keep the windows in the apartment open to allow for adequate oxygen flow. One month later she returned to our clinic and reported that her symptoms resolved; serum COHb was negative upon repeat lab tests.

THE TAKEAWAY

Patients who present with headaches, dizziness and/or fatigue should be evaluated for CO poisoning. The patient’s environmental history should be reviewed carefully, especially because CO poisoning is more common during the winter months. Oxygen therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Up to one-third of patients with acute poisoning may develop delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae, including cognitive changes, emotional lability, visual disturbances, disorientation, and depression, that may resolve within one year.

THE CASE

One month after moving into her mother’s apartment, a 27-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for fatigue, headache, blurred vision, nausea, and morning vomiting. She had weakness and difficulty sleeping, but denied any fever, rashes, neck stiffness, recent travel, trauma, or tobacco or illicit drug use. She did, however, have a 6-year history of migraines. Her physical exam was normal. She was sent home with a prescription for tramadol 50 mg bid for her headaches.

The patient subsequently went to the emergency department 3 times for the same complaints; none of the treatments she received there (mostly acetaminophen with codeine) relieved her symptoms. Three weeks later she returned to our clinic. She was distressed that the symptoms hadn’t gone away, and noted that her family was now experiencing similar symptoms.

Her temperature was 98.1°F (36.7°C), blood pressure was 131/88 mm Hg, pulse was 85 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min. Physical and neurologic exams were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Although most of the patient’s lab test results were within normal ranges, her carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) level was 4.2%. COHb levels of >2% to 3% in nonsmokers or >9% to 10% in smokers suggest carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning.1,2 Based on this finding and our patient’s symptoms, we diagnosed unintentional CO poisoning. We recommended that she and her mother vacate the apartment and have it inspected.

DISCUSSION

CO is the leading cause of poisoning mortality in the United States, and causes half of all fatal poisonings worldwide.1,3,4 It is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas that is produced by the incomplete combustion of carbon-based products, such as coal or gas.5,6 Exposure can occur from car exhaust fumes, faulty room heaters, and other sources (TABLE 1).6 The incidence of CO poisoning is higher during the winter months and after natural disasters. Individuals who have a lowered oxygen capacity, such as older adults, pregnant women (and their fetuses), infants, and patients with anemia, cardiovascular disease, or cerebrovascular disease, are more susceptible to CO poisoning.5,6

COHb, a stable complex of CO that forms in red blood cells when CO is inhaled, impairs oxygen delivery and peripheral utilization, resulting in cellular hypoxia.1 Signs and symptoms of CO poisoning are nonspecific and require a high degree of clinical suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment. Although cherry-red lips, peripheral cyanosis, and retinal hemorrhages are often described as “classic” symptoms of CO poisoning, these are rarely seen.6 The most common symptoms are actually headache (90%), dizziness (82%), and weakness (53%).7 Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, confusion, visual disturbances, loss of consciousness, angina, seizure, and fatigue.6,7 Symptoms of chronic CO poisoning may differ from those of acute poisoning and can include chronic fatigue, neuropathy, and memory deficit.8

The differential diagnosis for CO poisoning includes flu-like syndrome/influenza/other viral illnesses, migraine or tension headaches, depression, transient ischemic attack, encephalitis, coronary artery disease, gastroenteritis or food poisoning, seizures, and dysrhythmias.1,4 Lab testing for COHb can help narrow the diagnosis. CO poisoning can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on COHb levels and the patient’s signs and symptoms (TABLE 2).6 However, COHb level is a poor predictor of clinical presentation and should not be used to dictate management.2,7

Oxygen therapy is the recommended treatment

Early treatment with supplemental oxygen is recommended to reduce the length of time red blood cells are exposed to CO.1 A COHb level >25% is the criterion for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.1,3 Patients should receive treatment until their symptoms become less intense.

Delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae (DNS) can occur in up to one-third of patients with acute CO poisoning more than a month after apparent recovery.1,6,9 DNS symptoms include cognitive changes, emotional lability, visual disturbances, disorientation, depression, dementia, psychotic behavior, parkinsonism, amnesia, and incontinence.1,6,9 Approximately 50% to 75% of patients with DNS recover spontaneously within a year with symptomatic treatment.1,6,9

Our patient

After recommending that our patient (and her mother) leave the apartment and have it inspected, we later learned that the fire department was unable to determine the source of the CO. A CO detector was installed and our patient was advised to keep the windows in the apartment open to allow for adequate oxygen flow. One month later she returned to our clinic and reported that her symptoms resolved; serum COHb was negative upon repeat lab tests.

THE TAKEAWAY

Patients who present with headaches, dizziness and/or fatigue should be evaluated for CO poisoning. The patient’s environmental history should be reviewed carefully, especially because CO poisoning is more common during the winter months. Oxygen therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Up to one-third of patients with acute poisoning may develop delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae, including cognitive changes, emotional lability, visual disturbances, disorientation, and depression, that may resolve within one year.

1. Nikkanen H, Skolnik A. Diagnosis and management of carbon monoxide poisoning in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2011;13:1-14.

2. Hampson NB, Hauff NM. Carboxyhemoglobin levels in carbon monoxide poisoning: do they correlate with the clinical picture? Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:665-669.

3. Kao LW, Nañagas KA. Toxicity associated with carbon monoxide. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:99-125.

4. Varon J, Marik PE, Fromm RE Jr, et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning: a review for clinicians. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:87-93.

5. Harper A, Croft-Baker J. Carbon monoxide poisoning: undetected by both patients and their doctors. Age Ageing. 2004;33:105-109.

6. Smollin C, Olson K. Carbon monoxide poisoning (acute). BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010. pii:2103.

7. Wright J. Chronic and occult carbon monoxide poisoning: we don’t know what we’re missing. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:366-390.

8. Weaver LK. Clinical practice. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1217-1225.

9. Bhatia R, Chacko F, Lal V, et al. Reversible delayed neuropsychiatric syndrome following acute carbon monoxide exposure. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2007;11:80-82.

1. Nikkanen H, Skolnik A. Diagnosis and management of carbon monoxide poisoning in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2011;13:1-14.

2. Hampson NB, Hauff NM. Carboxyhemoglobin levels in carbon monoxide poisoning: do they correlate with the clinical picture? Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:665-669.

3. Kao LW, Nañagas KA. Toxicity associated with carbon monoxide. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:99-125.

4. Varon J, Marik PE, Fromm RE Jr, et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning: a review for clinicians. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:87-93.

5. Harper A, Croft-Baker J. Carbon monoxide poisoning: undetected by both patients and their doctors. Age Ageing. 2004;33:105-109.

6. Smollin C, Olson K. Carbon monoxide poisoning (acute). BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010. pii:2103.

7. Wright J. Chronic and occult carbon monoxide poisoning: we don’t know what we’re missing. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:366-390.

8. Weaver LK. Clinical practice. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1217-1225.

9. Bhatia R, Chacko F, Lal V, et al. Reversible delayed neuropsychiatric syndrome following acute carbon monoxide exposure. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2007;11:80-82.

How to discuss sex with elderly patients

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

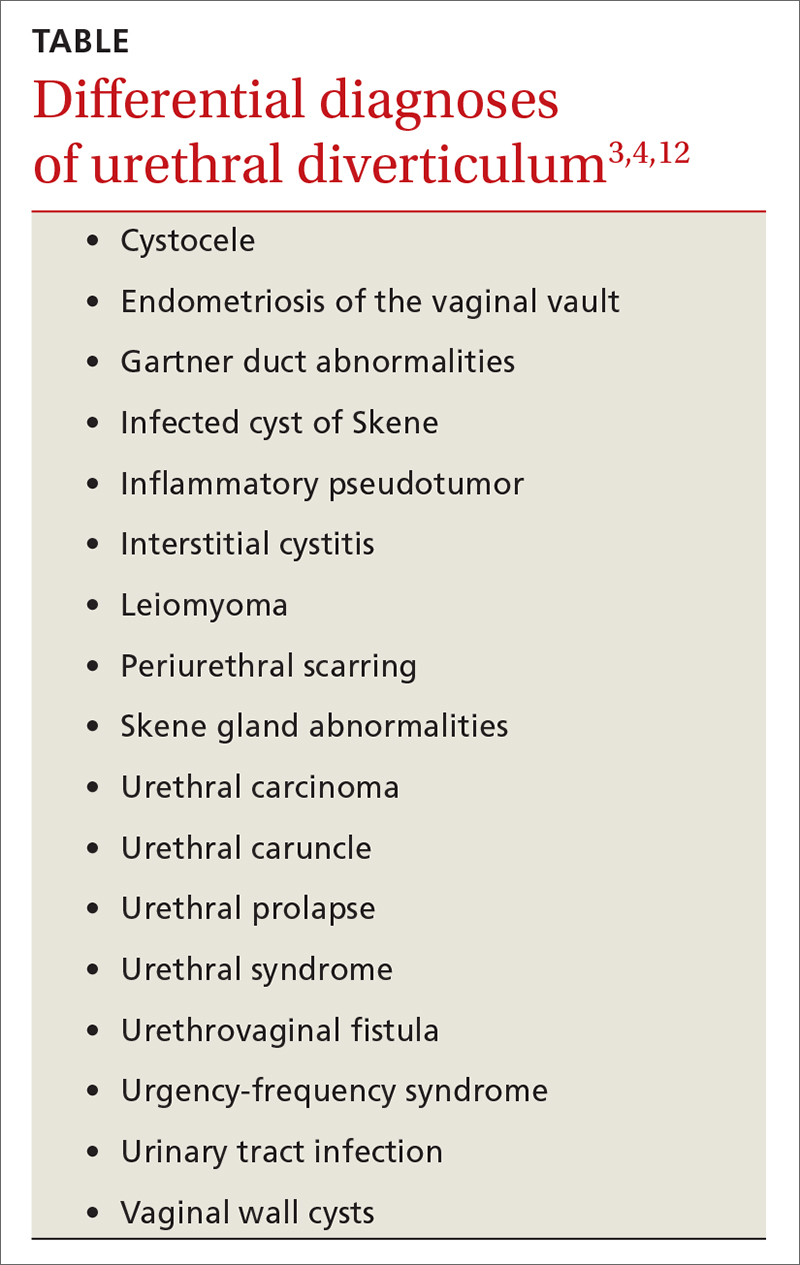

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; fomole@msm.edu

1. Balami JS. Are geriatricians guilty of failure to take a sexual history? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;2:17-20.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

3. Bradford A, Meston CM. Senior sexual health: The effects of aging on sexuality. In: VandeCreek L, Petersen FL, Bley JW, eds. Innovations in Clinical Practice: Focus on Sexual Health. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2007:35-45.

4. Graber C. Sex keeps elderly happier in marriage. Scientific American.

Available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/sex-keeps-elderly-happier-in-marria-11-11-29. Accessed March 26, 2014.

5. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

6. Tobin JM, Harindra V. Attendance by older patients at a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:289-291.

7. Bauer M, McAuliffe L, Nay R. Sexuality, health care and the older person: an overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:63-68.

8. Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, et al. The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011;(PB2011-2):1-8.

9. Henry J, McNab W. Forever young: a health promotion focus on sexuality and aging. Gerontol Geriatr Education. 2003;23:57-74.

10. Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093-2103.

11. Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1705-1712.

12. Burd ID, Nevadunsky N, Bachmann G. Impact of physician gender on sexual history taking in a multispecialty practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3:194-200.

13. Kazer MW. Sexuality Assessment for Older Adults. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing Web site. Available at: http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_10.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed March 14, 2014.

14. Wallace MA. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nursing. 2012;108:52-60.

15. Sexuality in later life. National Institute on Aging Web site. Available at: http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexualitylater-life. Updated March 11, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2014.

16. Hajjar RR, Kamel HK. Sexuality in the nursing home, part 1: attitudes and barriers to sexual expression. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(2 suppl):S42-S47.

17. Bildtgård T. The sexuality of elderly people on film—visual limitations. J Aging Identity. 2000;5:169-183.

18. Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6-16.

19. Gott M, Hinchliff S. Barriers to seeking treatment for sexual problems in primary care: a qualitative study with older people. Fam Pract. 2003;20:690-695.

20. Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:511-516.

21. Bouman W, Arcelus J, Benbow S. Nottingham study of sexuality & ageing (NoSSA I). Attitudes regarding sexuality and older people: a review of the literature. Sex Relationship Ther. 2006;21:149-161.

22. Low LPL, Lui MHL, Lee DTF, et al. Promoting awareness of sexuality of older people in residential care. Electronic J Human Sexuality. 2005;8:8-16.

23. Rheaume C, Mitty E. Sexuality and intimacy in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29:342-349.

24. Nagaratnam N, Gayagay G Jr. Hypersexuality in nursing care facilities—a descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35:195-203.

25. HIV among older Americans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/olderamericans/. Updated December 23, 2013. Accessed February 28, 2014.

26. Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:453-472.

27. Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; fomole@msm.edu

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; fomole@msm.edu

1. Balami JS. Are geriatricians guilty of failure to take a sexual history? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;2:17-20.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

3. Bradford A, Meston CM. Senior sexual health: The effects of aging on sexuality. In: VandeCreek L, Petersen FL, Bley JW, eds. Innovations in Clinical Practice: Focus on Sexual Health. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2007:35-45.

4. Graber C. Sex keeps elderly happier in marriage. Scientific American.

Available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/sex-keeps-elderly-happier-in-marria-11-11-29. Accessed March 26, 2014.

5. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

6. Tobin JM, Harindra V. Attendance by older patients at a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:289-291.

7. Bauer M, McAuliffe L, Nay R. Sexuality, health care and the older person: an overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:63-68.

8. Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, et al. The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011;(PB2011-2):1-8.

9. Henry J, McNab W. Forever young: a health promotion focus on sexuality and aging. Gerontol Geriatr Education. 2003;23:57-74.

10. Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093-2103.

11. Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1705-1712.

12. Burd ID, Nevadunsky N, Bachmann G. Impact of physician gender on sexual history taking in a multispecialty practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3:194-200.

13. Kazer MW. Sexuality Assessment for Older Adults. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing Web site. Available at: http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_10.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed March 14, 2014.

14. Wallace MA. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nursing. 2012;108:52-60.

15. Sexuality in later life. National Institute on Aging Web site. Available at: http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexualitylater-life. Updated March 11, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2014.

16. Hajjar RR, Kamel HK. Sexuality in the nursing home, part 1: attitudes and barriers to sexual expression. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(2 suppl):S42-S47.

17. Bildtgård T. The sexuality of elderly people on film—visual limitations. J Aging Identity. 2000;5:169-183.

18. Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6-16.