User login

Teledermatology in the US Military: A Historic Foundation for Current and Future Applications

Telemedicine arose from the need to provide critical and timely advice directly to health care providers and patients in remote or resource-scarce settings. Whether by radio, telephone, or other means of telecommunication technology, the US military has long utilized telemedicine. What started as a way to expedite the delivery of emergency consultations and medical expertise to remote populations in need has since evolved into a billion-dollar innovation industry that is poised to improve health care efficiency and access to specialist care as well as to lower health care costs for all patients.

Teledermatology in the Military

A primary mission of military medicine is to keep service members anywhere in the world in good health on the job during training, combat, and humanitarian operations.1 Telemedicine greatly supports this mission by bringing the expertise of medical specialists to service members in the field without the cost or risks of travel for physicians. Telemedicine also is effective in promoting timely triage of patients and administration of the most appropriate levels of care. With the advent and globalization of high-speed wireless networks, advancements in telemedicine continue to develop and are becoming increasingly useful in military medicine.

As a specialty, dermatology is heavily reliant on visual information and therefore is particularly amenable to telemedicine applications. The rising popularity of such services has led to the development of the term teledermatology. While early teledermatology services were provided using radio, telephone, fax, and videoconferencing,2 three distinct visual methods typically are used today, including (1) store-and-forward (S&F), (2) live-interactive, and (3) a hybrid of the two.3 Military dermatology predominantly utilizes an S&F system, as still photographs of lesions generally are preferred over video for more focused visualization.

In 2004, the US Army Medical Department established a centralized telemedicine program using Army Knowledge Online,1 an S&F system that allows providers in remote locations to store and forward information about a patient’s clinical history along with digital photographs of the patient’s condition to a military dermatologist to review and make a diagnosis or suggest a treatment from a different location at a later time. Using this platform to provide asynchronous teledermatology services avoids the logistics required to schedule appointments and promotes convenience and more efficient use of physicians’ time and resources.

Given the ease of use of S&F systems among military practitioners, dermatology became one of the most heavily utilized teleconsultation specialties within the Army Knowledge Online system, accounting for 40% of the 10,817 consultations initiated from April 2004 to December 2012.5 It also is important to note that skin conditions historically account for 15% to 75% of outpatient visits during wartime; therefore, there is a need for dermatologic consultations, as primary care providers typically are responsible for providing dermatologic care to these patients.6 Because of the high demand for and low volume of US military dermatologists, the use of teledermatology (ie, Amy Knowledge Online) in the US military became a helpful educational tool and specialist extender for many primary care providers in the military.

Teledermatology in the military has evolved to not only provide timely and efficient care but also to reduce health care costs.

Advances in Teledermatology

While the military continues to use S&F teleconsultations—a model in which a deployed referring clinician sends information to a military dermatologist for diagnosis and/or management recommendations—a number of teledermatology programs have been developed for civilians that provide additional advantages over standard face-to-face dermatology care. The advantages of S&F teledermatology applications are many, including faster communication with dermatology providers, diagnostic concordance comparable to face-to-face appointments, cost-effective care for patients, the ability to educate providers remotely,8 and similar outcomes to in-person care.9 However, as to be expected, in-person care remains the gold standard, especially when diagnostic accuracy depends on biopsy findings.

The development of the smartphone along with advances in digital photography and consumer-friendly mobile applications has allowed for the emergence of direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology applications. Regardless of the user’s ability, the quality of photographs taken with smartphones has improved, as standard features such as high-resolution cameras with image stabilization, automatic focus, and lighting have become commonplace. The popularity of smartphone technology also has increased, with nearly 75% of all adults and more than 90% of adults younger than 35 years of age owning a smartphone according to a 2016 survey.11

In 2015, there were at least 29 DTC teledermatology applications available on various mobile platforms,12 accounting for an estimated 1.25 million teleconsultations with providers.13 Teledermatology platforms such as DermatologistOnCall and Spruce Health have made accessing dermatologic care convenient, timely, and affordable for patients via patient-friendly mobile applications.

Regular access to dermatologic care is especially important for patients who have chronic skin conditions. Several unique practice models have emerged as innovative solutions to providing more convenient and timely care. For example, Curology (https://curology.com) is an online teledermatology practice specializing in acne treatment.

Although DTC teledermatology practices are convenient for many patients and providers, some have been criticized for providing poor quality of care12 or facilitating fragmented care by not integrating with established electronic health record (EHR) systems.15 As a result, recommended practice guidelines for DTC teledermatology have been developed by the American Academy of Dermatology and some state medical boards.16 Moreover, several EHR systems, such as Epic (www.epic.com) and Modernizing Medicine’s EMA (www.modmed.com), have developed fully integrated S&F teledermatology platforms to be incorporated with established brick-and-mortar care.17

The Future of Teledermatology in the Military

The Army Knowledge Online telemedicine platform used by the US military has continued to be useful, particularly when treating patients in remote locations, and shows promise for improving routine domestic dermatology care. It has reduced the number of medical evacuations and improved care for those who do not have access to a dermatologist.4 Furthermore, one study noted that most consultations submitted via teledermatology applications from a combat zone received a diagnosis and treatment recommendation from a military dermatologist faster than they would have stateside, where the wait often is 4 to 8 weeks. On average, a teledermatology consultation from Afghanistan was answered in less than 6 hours.4 Although this response time might not be realistic for all dermatology practices, there clearly is potential in certain situations and utilizing certain models of care to diagnose and treat more patients more efficiently utilizing teledermatology applications than in an in-person office visit. A review of 658 teledermatology consultations in the US military from January 2011 to December 2012 revealed that the leading diagnoses were eczematous dermatitis (14%), contact dermatitis (9%), nonmelanoma skin cancer (5%), psoriasis (4%), and urticaria (4%).4 Increased use of teledermatology evaluation of these conditions in routine US-based military practice could help expedite care, decrease patient travel time, and utilize in-clinic dermatologist time more efficiently. Teledermatology visits for postoperative concerns also have demonstrated utility and convenience for triage and management of patients in the civilian setting and may be an additional novel use of teledermatology in the military setting.18 With the use of an integrated S&F teledermatology platform within an existing EHR system that is paired with a secure patient mobile application that allows easy upload of photos, medical history, and messaging, it can be argued that quality of life could greatly be enhanced for both military patients and providers.

Limitations of Teledermatology

Certainly, there are and will always be limitations to teledermatology. Even as digital photography improves, the quality and context of clinical images are user dependent, and key associated skin findings in other locations of the body can be missed. The ability to palpate the skin also is lacking in virtual encounters. Therefore, teledermatology might be considered most appropriate for specific diseases and conditions (eg, acne, psoriasis, eczema). Embracing teledermatology does not mean replacing in-person care; rather, it should be seen as an adjunct used to manage the high demand for dermatology expertise in military and civilian practice. For the US military, the promise and potential to embrace innovation in providing dermatologic care is there, as long as there are leaders to continue to champion it. In the current state of health care, many of the perceived barriers of teledermatology applications have already been overcome, including lack of training, lack of reimbursement, and perceived medicolegal risks.19

The US Federal Government is a large entity, and it will undoubtedly take time and effort to implement new and innovative programs such as the ones described here in the military. The first step in implementation is awareness that the possibilities exist; then, with the cooperation of dermatologists and support from the chain of command, it will be possible to incorporate advances in teledermatology and cultivate new ones.

Final Thoughts

The S&F teledermatology method used in the military setting has become commonplace in both military and civilian settings alike. Newer innovations in telemedicine, particularly in teledermatology, will continue to shape the future of military and civilian medicine for years to come.

- Vidmar DA. The history of teledermatology in the Department of Defense. Dermatol Clin. 1999;17:113-124.

- McManus J, Salinas J, Morton M, et al. Teleconsultation program for deployed soldiers and healthcare professionals in remote and austere environments. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:210-216.

- Tensen E, Van Der Heijden JP, Jaspers MW, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353.

- McGraw TA, Norton SA. Military aeromedical evacuations from central and southwest Asia for ill-defined dermatologic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:165-170.

- Shissel DJ, Wilde J. Operational dermatology. Mil Med. 2004;169:444-447.

- Henning JS, Wohltmann W, Hivnor C. Teledermatology from a combat zone. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:676-677.

- Whited JD, Hall RP, Simel DL, et al. Reliability and accuracy of dermatologists’ clinic-based and digital image consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:693-702.

- Pak H, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, et al. Store-and-forward teledermatology results in similar clinical outcomes to conventional clinic-based care. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13:26-30.

- Finnane A, Dallest K, Janda M, et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327.

- Poushter J. Smartphone ownership and internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. www.pewglobal.org/2016/02/22/smartphone-ownership-and-internet-usage-continues-to-climbin-emerging-economies/. Published February 22, 2016. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Peart JM, Kovarik C. Direct-to-patient teledermatology practices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:907-909.

- Huff C. Medical diagnosis by webcam? Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons. www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-2015/telemedicine-health-symptoms-diagnosis.html. Published December 2015. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Mehrotra A. The convenience revolution for the treatment of low-acuity conditions. JAMA. 2013;310:35-36.

- Resneck JS Jr, Abrouk M, Steuer M, et al. Choice, transparency, coordination, and quality among direct-to-consumer telemedicine websites and apps treating skin disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:768-775.

- Teledermatology toolkit. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/practicecenter/managing-a-practice/teledermatology. Accessed April 24, 2018.

- Carter ZA, Goldman S, Anderson K, et al. Creation of an internalteledermatology store-and-forward system in an existing electronic health record: a pilot study in a safety-net public health and hospital system. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:644-650.

- Jeyamohan SR, Moye MS, Srivastava D, et al. Patient-acquired photographs for the management of postoperative concerns. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:226-227.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:650-651.

Telemedicine arose from the need to provide critical and timely advice directly to health care providers and patients in remote or resource-scarce settings. Whether by radio, telephone, or other means of telecommunication technology, the US military has long utilized telemedicine. What started as a way to expedite the delivery of emergency consultations and medical expertise to remote populations in need has since evolved into a billion-dollar innovation industry that is poised to improve health care efficiency and access to specialist care as well as to lower health care costs for all patients.

Teledermatology in the Military

A primary mission of military medicine is to keep service members anywhere in the world in good health on the job during training, combat, and humanitarian operations.1 Telemedicine greatly supports this mission by bringing the expertise of medical specialists to service members in the field without the cost or risks of travel for physicians. Telemedicine also is effective in promoting timely triage of patients and administration of the most appropriate levels of care. With the advent and globalization of high-speed wireless networks, advancements in telemedicine continue to develop and are becoming increasingly useful in military medicine.

As a specialty, dermatology is heavily reliant on visual information and therefore is particularly amenable to telemedicine applications. The rising popularity of such services has led to the development of the term teledermatology. While early teledermatology services were provided using radio, telephone, fax, and videoconferencing,2 three distinct visual methods typically are used today, including (1) store-and-forward (S&F), (2) live-interactive, and (3) a hybrid of the two.3 Military dermatology predominantly utilizes an S&F system, as still photographs of lesions generally are preferred over video for more focused visualization.

In 2004, the US Army Medical Department established a centralized telemedicine program using Army Knowledge Online,1 an S&F system that allows providers in remote locations to store and forward information about a patient’s clinical history along with digital photographs of the patient’s condition to a military dermatologist to review and make a diagnosis or suggest a treatment from a different location at a later time. Using this platform to provide asynchronous teledermatology services avoids the logistics required to schedule appointments and promotes convenience and more efficient use of physicians’ time and resources.

Given the ease of use of S&F systems among military practitioners, dermatology became one of the most heavily utilized teleconsultation specialties within the Army Knowledge Online system, accounting for 40% of the 10,817 consultations initiated from April 2004 to December 2012.5 It also is important to note that skin conditions historically account for 15% to 75% of outpatient visits during wartime; therefore, there is a need for dermatologic consultations, as primary care providers typically are responsible for providing dermatologic care to these patients.6 Because of the high demand for and low volume of US military dermatologists, the use of teledermatology (ie, Amy Knowledge Online) in the US military became a helpful educational tool and specialist extender for many primary care providers in the military.

Teledermatology in the military has evolved to not only provide timely and efficient care but also to reduce health care costs.

Advances in Teledermatology

While the military continues to use S&F teleconsultations—a model in which a deployed referring clinician sends information to a military dermatologist for diagnosis and/or management recommendations—a number of teledermatology programs have been developed for civilians that provide additional advantages over standard face-to-face dermatology care. The advantages of S&F teledermatology applications are many, including faster communication with dermatology providers, diagnostic concordance comparable to face-to-face appointments, cost-effective care for patients, the ability to educate providers remotely,8 and similar outcomes to in-person care.9 However, as to be expected, in-person care remains the gold standard, especially when diagnostic accuracy depends on biopsy findings.

The development of the smartphone along with advances in digital photography and consumer-friendly mobile applications has allowed for the emergence of direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology applications. Regardless of the user’s ability, the quality of photographs taken with smartphones has improved, as standard features such as high-resolution cameras with image stabilization, automatic focus, and lighting have become commonplace. The popularity of smartphone technology also has increased, with nearly 75% of all adults and more than 90% of adults younger than 35 years of age owning a smartphone according to a 2016 survey.11

In 2015, there were at least 29 DTC teledermatology applications available on various mobile platforms,12 accounting for an estimated 1.25 million teleconsultations with providers.13 Teledermatology platforms such as DermatologistOnCall and Spruce Health have made accessing dermatologic care convenient, timely, and affordable for patients via patient-friendly mobile applications.

Regular access to dermatologic care is especially important for patients who have chronic skin conditions. Several unique practice models have emerged as innovative solutions to providing more convenient and timely care. For example, Curology (https://curology.com) is an online teledermatology practice specializing in acne treatment.

Although DTC teledermatology practices are convenient for many patients and providers, some have been criticized for providing poor quality of care12 or facilitating fragmented care by not integrating with established electronic health record (EHR) systems.15 As a result, recommended practice guidelines for DTC teledermatology have been developed by the American Academy of Dermatology and some state medical boards.16 Moreover, several EHR systems, such as Epic (www.epic.com) and Modernizing Medicine’s EMA (www.modmed.com), have developed fully integrated S&F teledermatology platforms to be incorporated with established brick-and-mortar care.17

The Future of Teledermatology in the Military

The Army Knowledge Online telemedicine platform used by the US military has continued to be useful, particularly when treating patients in remote locations, and shows promise for improving routine domestic dermatology care. It has reduced the number of medical evacuations and improved care for those who do not have access to a dermatologist.4 Furthermore, one study noted that most consultations submitted via teledermatology applications from a combat zone received a diagnosis and treatment recommendation from a military dermatologist faster than they would have stateside, where the wait often is 4 to 8 weeks. On average, a teledermatology consultation from Afghanistan was answered in less than 6 hours.4 Although this response time might not be realistic for all dermatology practices, there clearly is potential in certain situations and utilizing certain models of care to diagnose and treat more patients more efficiently utilizing teledermatology applications than in an in-person office visit. A review of 658 teledermatology consultations in the US military from January 2011 to December 2012 revealed that the leading diagnoses were eczematous dermatitis (14%), contact dermatitis (9%), nonmelanoma skin cancer (5%), psoriasis (4%), and urticaria (4%).4 Increased use of teledermatology evaluation of these conditions in routine US-based military practice could help expedite care, decrease patient travel time, and utilize in-clinic dermatologist time more efficiently. Teledermatology visits for postoperative concerns also have demonstrated utility and convenience for triage and management of patients in the civilian setting and may be an additional novel use of teledermatology in the military setting.18 With the use of an integrated S&F teledermatology platform within an existing EHR system that is paired with a secure patient mobile application that allows easy upload of photos, medical history, and messaging, it can be argued that quality of life could greatly be enhanced for both military patients and providers.

Limitations of Teledermatology

Certainly, there are and will always be limitations to teledermatology. Even as digital photography improves, the quality and context of clinical images are user dependent, and key associated skin findings in other locations of the body can be missed. The ability to palpate the skin also is lacking in virtual encounters. Therefore, teledermatology might be considered most appropriate for specific diseases and conditions (eg, acne, psoriasis, eczema). Embracing teledermatology does not mean replacing in-person care; rather, it should be seen as an adjunct used to manage the high demand for dermatology expertise in military and civilian practice. For the US military, the promise and potential to embrace innovation in providing dermatologic care is there, as long as there are leaders to continue to champion it. In the current state of health care, many of the perceived barriers of teledermatology applications have already been overcome, including lack of training, lack of reimbursement, and perceived medicolegal risks.19

The US Federal Government is a large entity, and it will undoubtedly take time and effort to implement new and innovative programs such as the ones described here in the military. The first step in implementation is awareness that the possibilities exist; then, with the cooperation of dermatologists and support from the chain of command, it will be possible to incorporate advances in teledermatology and cultivate new ones.

Final Thoughts

The S&F teledermatology method used in the military setting has become commonplace in both military and civilian settings alike. Newer innovations in telemedicine, particularly in teledermatology, will continue to shape the future of military and civilian medicine for years to come.

Telemedicine arose from the need to provide critical and timely advice directly to health care providers and patients in remote or resource-scarce settings. Whether by radio, telephone, or other means of telecommunication technology, the US military has long utilized telemedicine. What started as a way to expedite the delivery of emergency consultations and medical expertise to remote populations in need has since evolved into a billion-dollar innovation industry that is poised to improve health care efficiency and access to specialist care as well as to lower health care costs for all patients.

Teledermatology in the Military

A primary mission of military medicine is to keep service members anywhere in the world in good health on the job during training, combat, and humanitarian operations.1 Telemedicine greatly supports this mission by bringing the expertise of medical specialists to service members in the field without the cost or risks of travel for physicians. Telemedicine also is effective in promoting timely triage of patients and administration of the most appropriate levels of care. With the advent and globalization of high-speed wireless networks, advancements in telemedicine continue to develop and are becoming increasingly useful in military medicine.

As a specialty, dermatology is heavily reliant on visual information and therefore is particularly amenable to telemedicine applications. The rising popularity of such services has led to the development of the term teledermatology. While early teledermatology services were provided using radio, telephone, fax, and videoconferencing,2 three distinct visual methods typically are used today, including (1) store-and-forward (S&F), (2) live-interactive, and (3) a hybrid of the two.3 Military dermatology predominantly utilizes an S&F system, as still photographs of lesions generally are preferred over video for more focused visualization.

In 2004, the US Army Medical Department established a centralized telemedicine program using Army Knowledge Online,1 an S&F system that allows providers in remote locations to store and forward information about a patient’s clinical history along with digital photographs of the patient’s condition to a military dermatologist to review and make a diagnosis or suggest a treatment from a different location at a later time. Using this platform to provide asynchronous teledermatology services avoids the logistics required to schedule appointments and promotes convenience and more efficient use of physicians’ time and resources.

Given the ease of use of S&F systems among military practitioners, dermatology became one of the most heavily utilized teleconsultation specialties within the Army Knowledge Online system, accounting for 40% of the 10,817 consultations initiated from April 2004 to December 2012.5 It also is important to note that skin conditions historically account for 15% to 75% of outpatient visits during wartime; therefore, there is a need for dermatologic consultations, as primary care providers typically are responsible for providing dermatologic care to these patients.6 Because of the high demand for and low volume of US military dermatologists, the use of teledermatology (ie, Amy Knowledge Online) in the US military became a helpful educational tool and specialist extender for many primary care providers in the military.

Teledermatology in the military has evolved to not only provide timely and efficient care but also to reduce health care costs.

Advances in Teledermatology

While the military continues to use S&F teleconsultations—a model in which a deployed referring clinician sends information to a military dermatologist for diagnosis and/or management recommendations—a number of teledermatology programs have been developed for civilians that provide additional advantages over standard face-to-face dermatology care. The advantages of S&F teledermatology applications are many, including faster communication with dermatology providers, diagnostic concordance comparable to face-to-face appointments, cost-effective care for patients, the ability to educate providers remotely,8 and similar outcomes to in-person care.9 However, as to be expected, in-person care remains the gold standard, especially when diagnostic accuracy depends on biopsy findings.

The development of the smartphone along with advances in digital photography and consumer-friendly mobile applications has allowed for the emergence of direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology applications. Regardless of the user’s ability, the quality of photographs taken with smartphones has improved, as standard features such as high-resolution cameras with image stabilization, automatic focus, and lighting have become commonplace. The popularity of smartphone technology also has increased, with nearly 75% of all adults and more than 90% of adults younger than 35 years of age owning a smartphone according to a 2016 survey.11

In 2015, there were at least 29 DTC teledermatology applications available on various mobile platforms,12 accounting for an estimated 1.25 million teleconsultations with providers.13 Teledermatology platforms such as DermatologistOnCall and Spruce Health have made accessing dermatologic care convenient, timely, and affordable for patients via patient-friendly mobile applications.

Regular access to dermatologic care is especially important for patients who have chronic skin conditions. Several unique practice models have emerged as innovative solutions to providing more convenient and timely care. For example, Curology (https://curology.com) is an online teledermatology practice specializing in acne treatment.

Although DTC teledermatology practices are convenient for many patients and providers, some have been criticized for providing poor quality of care12 or facilitating fragmented care by not integrating with established electronic health record (EHR) systems.15 As a result, recommended practice guidelines for DTC teledermatology have been developed by the American Academy of Dermatology and some state medical boards.16 Moreover, several EHR systems, such as Epic (www.epic.com) and Modernizing Medicine’s EMA (www.modmed.com), have developed fully integrated S&F teledermatology platforms to be incorporated with established brick-and-mortar care.17

The Future of Teledermatology in the Military

The Army Knowledge Online telemedicine platform used by the US military has continued to be useful, particularly when treating patients in remote locations, and shows promise for improving routine domestic dermatology care. It has reduced the number of medical evacuations and improved care for those who do not have access to a dermatologist.4 Furthermore, one study noted that most consultations submitted via teledermatology applications from a combat zone received a diagnosis and treatment recommendation from a military dermatologist faster than they would have stateside, where the wait often is 4 to 8 weeks. On average, a teledermatology consultation from Afghanistan was answered in less than 6 hours.4 Although this response time might not be realistic for all dermatology practices, there clearly is potential in certain situations and utilizing certain models of care to diagnose and treat more patients more efficiently utilizing teledermatology applications than in an in-person office visit. A review of 658 teledermatology consultations in the US military from January 2011 to December 2012 revealed that the leading diagnoses were eczematous dermatitis (14%), contact dermatitis (9%), nonmelanoma skin cancer (5%), psoriasis (4%), and urticaria (4%).4 Increased use of teledermatology evaluation of these conditions in routine US-based military practice could help expedite care, decrease patient travel time, and utilize in-clinic dermatologist time more efficiently. Teledermatology visits for postoperative concerns also have demonstrated utility and convenience for triage and management of patients in the civilian setting and may be an additional novel use of teledermatology in the military setting.18 With the use of an integrated S&F teledermatology platform within an existing EHR system that is paired with a secure patient mobile application that allows easy upload of photos, medical history, and messaging, it can be argued that quality of life could greatly be enhanced for both military patients and providers.

Limitations of Teledermatology

Certainly, there are and will always be limitations to teledermatology. Even as digital photography improves, the quality and context of clinical images are user dependent, and key associated skin findings in other locations of the body can be missed. The ability to palpate the skin also is lacking in virtual encounters. Therefore, teledermatology might be considered most appropriate for specific diseases and conditions (eg, acne, psoriasis, eczema). Embracing teledermatology does not mean replacing in-person care; rather, it should be seen as an adjunct used to manage the high demand for dermatology expertise in military and civilian practice. For the US military, the promise and potential to embrace innovation in providing dermatologic care is there, as long as there are leaders to continue to champion it. In the current state of health care, many of the perceived barriers of teledermatology applications have already been overcome, including lack of training, lack of reimbursement, and perceived medicolegal risks.19

The US Federal Government is a large entity, and it will undoubtedly take time and effort to implement new and innovative programs such as the ones described here in the military. The first step in implementation is awareness that the possibilities exist; then, with the cooperation of dermatologists and support from the chain of command, it will be possible to incorporate advances in teledermatology and cultivate new ones.

Final Thoughts

The S&F teledermatology method used in the military setting has become commonplace in both military and civilian settings alike. Newer innovations in telemedicine, particularly in teledermatology, will continue to shape the future of military and civilian medicine for years to come.

- Vidmar DA. The history of teledermatology in the Department of Defense. Dermatol Clin. 1999;17:113-124.

- McManus J, Salinas J, Morton M, et al. Teleconsultation program for deployed soldiers and healthcare professionals in remote and austere environments. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:210-216.

- Tensen E, Van Der Heijden JP, Jaspers MW, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353.

- McGraw TA, Norton SA. Military aeromedical evacuations from central and southwest Asia for ill-defined dermatologic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:165-170.

- Shissel DJ, Wilde J. Operational dermatology. Mil Med. 2004;169:444-447.

- Henning JS, Wohltmann W, Hivnor C. Teledermatology from a combat zone. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:676-677.

- Whited JD, Hall RP, Simel DL, et al. Reliability and accuracy of dermatologists’ clinic-based and digital image consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:693-702.

- Pak H, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, et al. Store-and-forward teledermatology results in similar clinical outcomes to conventional clinic-based care. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13:26-30.

- Finnane A, Dallest K, Janda M, et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327.

- Poushter J. Smartphone ownership and internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. www.pewglobal.org/2016/02/22/smartphone-ownership-and-internet-usage-continues-to-climbin-emerging-economies/. Published February 22, 2016. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Peart JM, Kovarik C. Direct-to-patient teledermatology practices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:907-909.

- Huff C. Medical diagnosis by webcam? Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons. www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-2015/telemedicine-health-symptoms-diagnosis.html. Published December 2015. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Mehrotra A. The convenience revolution for the treatment of low-acuity conditions. JAMA. 2013;310:35-36.

- Resneck JS Jr, Abrouk M, Steuer M, et al. Choice, transparency, coordination, and quality among direct-to-consumer telemedicine websites and apps treating skin disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:768-775.

- Teledermatology toolkit. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/practicecenter/managing-a-practice/teledermatology. Accessed April 24, 2018.

- Carter ZA, Goldman S, Anderson K, et al. Creation of an internalteledermatology store-and-forward system in an existing electronic health record: a pilot study in a safety-net public health and hospital system. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:644-650.

- Jeyamohan SR, Moye MS, Srivastava D, et al. Patient-acquired photographs for the management of postoperative concerns. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:226-227.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:650-651.

- Vidmar DA. The history of teledermatology in the Department of Defense. Dermatol Clin. 1999;17:113-124.

- McManus J, Salinas J, Morton M, et al. Teleconsultation program for deployed soldiers and healthcare professionals in remote and austere environments. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:210-216.

- Tensen E, Van Der Heijden JP, Jaspers MW, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353.

- McGraw TA, Norton SA. Military aeromedical evacuations from central and southwest Asia for ill-defined dermatologic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:165-170.

- Shissel DJ, Wilde J. Operational dermatology. Mil Med. 2004;169:444-447.

- Henning JS, Wohltmann W, Hivnor C. Teledermatology from a combat zone. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:676-677.

- Whited JD, Hall RP, Simel DL, et al. Reliability and accuracy of dermatologists’ clinic-based and digital image consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:693-702.

- Pak H, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, et al. Store-and-forward teledermatology results in similar clinical outcomes to conventional clinic-based care. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13:26-30.

- Finnane A, Dallest K, Janda M, et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327.

- Poushter J. Smartphone ownership and internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. www.pewglobal.org/2016/02/22/smartphone-ownership-and-internet-usage-continues-to-climbin-emerging-economies/. Published February 22, 2016. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Peart JM, Kovarik C. Direct-to-patient teledermatology practices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:907-909.

- Huff C. Medical diagnosis by webcam? Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons. www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-2015/telemedicine-health-symptoms-diagnosis.html. Published December 2015. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Mehrotra A. The convenience revolution for the treatment of low-acuity conditions. JAMA. 2013;310:35-36.

- Resneck JS Jr, Abrouk M, Steuer M, et al. Choice, transparency, coordination, and quality among direct-to-consumer telemedicine websites and apps treating skin disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:768-775.

- Teledermatology toolkit. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/practicecenter/managing-a-practice/teledermatology. Accessed April 24, 2018.

- Carter ZA, Goldman S, Anderson K, et al. Creation of an internalteledermatology store-and-forward system in an existing electronic health record: a pilot study in a safety-net public health and hospital system. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:644-650.

- Jeyamohan SR, Moye MS, Srivastava D, et al. Patient-acquired photographs for the management of postoperative concerns. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:226-227.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:650-651.

Practice Points

- Teledermatology is increasing in its use and applications in both military and civilian medicine.

- The increased availability of high-quality digital photography as a result of smartphone technology lends itself well to store-and-forward (S&F) teledermatology applications.

- In the civilian community, new methods and platforms for teledermatology have been created based largely on those used by the military to maximize access to and efficiency of health care, including secure direct-to-consumer (DTC) mobile applications, live interactive methods, and integrated S&F platforms within electronic health record (EHR) systems.

Non-healing, non-tender ulcer on shin

A 63-year-old morbidly obese man presented to our clinic with a non-healing, slowly growing, painless ulcer on his right shin that he’d had for one year. It was not actively bleeding or draining, but the scab had come off one month earlier and the wound did not close. The patient denied any trauma to the area or foreign travel. Bacitracin and triamcinolone creams hadn’t helped.

Our patient’s medical history included diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and worsening venous insufficiency. He was not currently using compression stockings, but they had helped him in the past.

On examination, we noted a 3 x 3.5 cm well-demarcated, somewhat geometric, clean-based ulceration on the patient’s right medial shin (FIGURE 1A). There was no significant erythema, purulence, tenderness, warmth, or drainage of the ulcer. The base had seemingly normal granulation tissue. Woody induration, verrucous plaques, and confluent erythematous, violaceous, indurated patches were adjacent to the ulcer (FIGURE 1B). The patient also had severe pitting edema on his lower legs.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infiltrative basal cell carcinoma

In addition to our patient’s history of venous insufficiency, he’d also had a melanoma removed from his right shoulder 6 years earlier, and a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) removed from his upper back 2 years earlier. The chronic, non-healing nature of the ulcer prompted us to perform a punch biopsy, which revealed infiltrative BCC. We also did a wound culture, which showed a secondary infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The verrucous plaques next to the ulcer were the result of chronic venous stasis and lymphedema.

BCC is the most common type of cancer, estimated to comprise 80% of all skin cancers.1 It typically presents on the head and neck, but can occur in other locations. Eight percent of BCCs occur on the legs.2,3 Lower extremity BCC is more common in women, likely due to increased ultraviolet radiation exposure.2,4

BCC presents as erythematous and pearly macules, papules, nodules, ulcers, or scars, and can be pigmented. It may appear as a crusted ulcer (known as a “rodent ulcer”) with a rolled, translucent border and telangiectases.5 There are 5 major histologic subtypes of BCC: nodular, micronodular, superficial, morpheaform, and infiltrative.1,5 Infiltrative BCCs are an invasive subtype1,5 and may be more commonly associated with severe venous stasis,3 as was the case with our patient.

Although considered uncommon, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and BCC have been discovered in chronic leg ulcers.4,6 In fact, one report suggests that as many as 10% of chronic leg ulcers are malignant (31% BCC, 56% SCC).7 Thus, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in chronic leg ulcers.

Ulcerating BCC can mimic other types of leg ulcers

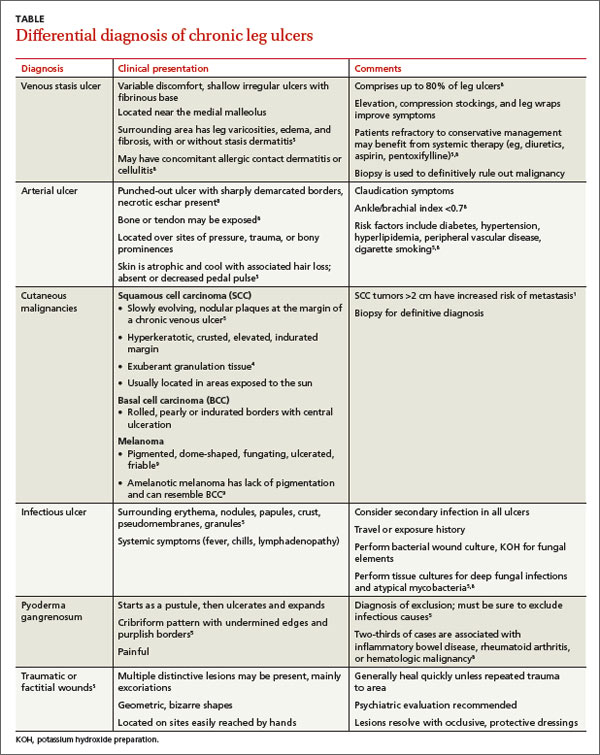

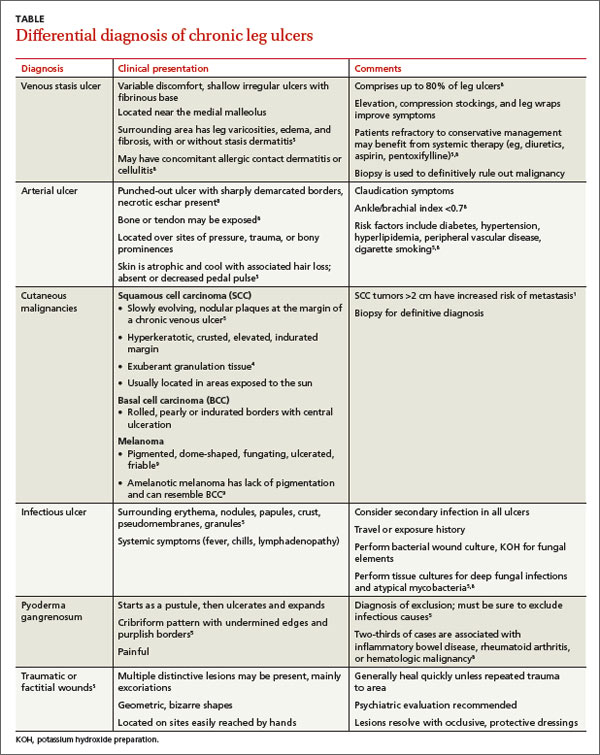

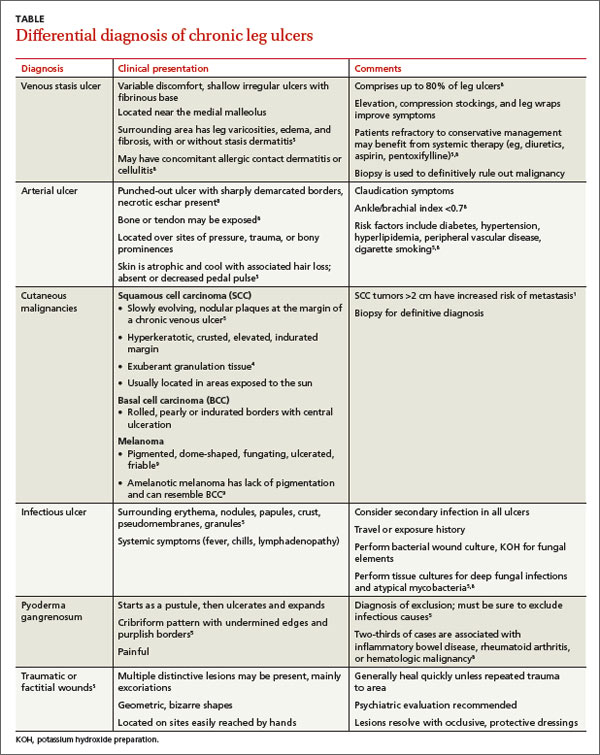

The differential diagnosis of a chronic leg ulcer includes venous or arterial ulcers, malignancies (SCC, BCC, lymphoma, melanoma), infectious ulcers (bacterial, deep fungal), pyoderma gangrenosum, and traumatic or factitial wounds (TABLE).1,4,5,8,9

Consider biopsy for ulcers that don't respond to treatment

The diagnosis of BCC in a leg ulcer is confirmed histologically. A punch or incisional biopsy should be taken at the edge of the ulcer, including the base.5,6 (For a Watch & Learn video that demonstrates how to perform a punch biopsy, go to http://bit.ly/punch_biopsy.) Providers may be concerned that biopsies could worsen a chronic wound; however, biopsy sites usually heal with no substantial complications.2,6,7 There are no guidelines on when to biopsy an ulcer, but it is reasonable to biopsy a leg ulcer that has not responded to 3 months of conservative treatment.2,7

Factors associated with malignancy in chronic leg ulcers include older age, abnormal excessive granulation tissue at wound edges, high clinical suspicion of cancer, and number of previous biopsies.7 The size and duration of the ulcer do not directly correlate with malignancy.7 The threshold for performing a diagnostic biopsy in a chronic leg ulcer should be lower for a patient who has any of the risk factors noted above. Be aware that ulcerating skin cancers may lack the classic appearance of typical skin cancers.6

For most BCCs, surgical excision will be required

Each BCC must be thoroughly evaluated for size, location, and histologic subtype. Surgical excision is the preferred treatment in most cases.5 Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery include skin cancers with aggressive histologic subtypes, such as infiltrative BCC, and tumors larger than 2 cm that are located on the extremities.1,5 Due to the limited amount of excess skin on the lower leg, skin flaps or grafts may be required.

Electrodessication and curettage, topical therapy with 5% imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, and cryotherapy are reserved for certain low-risk superficial and nodular BCCs.1,5 Radiation therapy is an option for tumors that are not amenable to surgery. Treatment is tailored to the patient’s needs based on age, medical history, and the characteristics of the skin cancer.

Inadequate treatment of BCCs can result in recurrences, which may appear 4 to 12 months after treatment.5 Close followup with regular full body skin exams is indicated.

Our patient was treated with Bactrim DS (800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) one tablet PO BID for 10 days and acetic acid soaks for the MRSA. While it was clear that the patient needed Mohs surgery, it was important to first address his lower extremity edema. He was evaluated by a vascular surgeon and resumed using compression stockings regularly.

The patient then underwent Mohs surgery.

After 2 stages of the surgery, the patient’s ulcer healed partially by secondary intention. After 5 months, the ulcer was covered with a split-thickness skin graft. Nine months after diagnosis, the patient had no clinical recurrence.

Physicians subsequently identified 2 BCCs on his face and scalp that were also treated with Mohs surgery. Our patient continues to have regular skin examinations.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jane Hwang, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Kunsan Air Base, PSC 2 Box 205, APO, AP 96264; jane.hwang.1@us.af.mil

1. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

2. Phillips TJ, Salman SM, Rogers GS. Nonhealing leg ulcers: a manifestation of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25;47-49.

3. Lutz ME, Davis MD, Otley CC. Infiltrating basal cell carcinoma in the setting of a venous ulcer. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:519-520.

4. Jankovic A, Binic I, Ljubenovic M. Basal cell carcinoma is not granulation tissue in the venous leg ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:182-184.

5. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 29. Epidermal nevi, neoplasms, and cysts. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

6. Yang D, Morrison BD, Vandongen YK, et al. Malignancy in chronic leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 1996;164:718-720.

7. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al; Angio-Dermatology Group Of The French Society Of Dermatology. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: the value of systematic wound biopsies: a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

8. Valencia IC, Falabella A, Kirsner RS, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:401-421.

9. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 30. Melanocytic nevi and neoplasms. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

A 63-year-old morbidly obese man presented to our clinic with a non-healing, slowly growing, painless ulcer on his right shin that he’d had for one year. It was not actively bleeding or draining, but the scab had come off one month earlier and the wound did not close. The patient denied any trauma to the area or foreign travel. Bacitracin and triamcinolone creams hadn’t helped.

Our patient’s medical history included diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and worsening venous insufficiency. He was not currently using compression stockings, but they had helped him in the past.

On examination, we noted a 3 x 3.5 cm well-demarcated, somewhat geometric, clean-based ulceration on the patient’s right medial shin (FIGURE 1A). There was no significant erythema, purulence, tenderness, warmth, or drainage of the ulcer. The base had seemingly normal granulation tissue. Woody induration, verrucous plaques, and confluent erythematous, violaceous, indurated patches were adjacent to the ulcer (FIGURE 1B). The patient also had severe pitting edema on his lower legs.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infiltrative basal cell carcinoma

In addition to our patient’s history of venous insufficiency, he’d also had a melanoma removed from his right shoulder 6 years earlier, and a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) removed from his upper back 2 years earlier. The chronic, non-healing nature of the ulcer prompted us to perform a punch biopsy, which revealed infiltrative BCC. We also did a wound culture, which showed a secondary infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The verrucous plaques next to the ulcer were the result of chronic venous stasis and lymphedema.

BCC is the most common type of cancer, estimated to comprise 80% of all skin cancers.1 It typically presents on the head and neck, but can occur in other locations. Eight percent of BCCs occur on the legs.2,3 Lower extremity BCC is more common in women, likely due to increased ultraviolet radiation exposure.2,4

BCC presents as erythematous and pearly macules, papules, nodules, ulcers, or scars, and can be pigmented. It may appear as a crusted ulcer (known as a “rodent ulcer”) with a rolled, translucent border and telangiectases.5 There are 5 major histologic subtypes of BCC: nodular, micronodular, superficial, morpheaform, and infiltrative.1,5 Infiltrative BCCs are an invasive subtype1,5 and may be more commonly associated with severe venous stasis,3 as was the case with our patient.

Although considered uncommon, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and BCC have been discovered in chronic leg ulcers.4,6 In fact, one report suggests that as many as 10% of chronic leg ulcers are malignant (31% BCC, 56% SCC).7 Thus, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in chronic leg ulcers.

Ulcerating BCC can mimic other types of leg ulcers

The differential diagnosis of a chronic leg ulcer includes venous or arterial ulcers, malignancies (SCC, BCC, lymphoma, melanoma), infectious ulcers (bacterial, deep fungal), pyoderma gangrenosum, and traumatic or factitial wounds (TABLE).1,4,5,8,9

Consider biopsy for ulcers that don't respond to treatment

The diagnosis of BCC in a leg ulcer is confirmed histologically. A punch or incisional biopsy should be taken at the edge of the ulcer, including the base.5,6 (For a Watch & Learn video that demonstrates how to perform a punch biopsy, go to http://bit.ly/punch_biopsy.) Providers may be concerned that biopsies could worsen a chronic wound; however, biopsy sites usually heal with no substantial complications.2,6,7 There are no guidelines on when to biopsy an ulcer, but it is reasonable to biopsy a leg ulcer that has not responded to 3 months of conservative treatment.2,7

Factors associated with malignancy in chronic leg ulcers include older age, abnormal excessive granulation tissue at wound edges, high clinical suspicion of cancer, and number of previous biopsies.7 The size and duration of the ulcer do not directly correlate with malignancy.7 The threshold for performing a diagnostic biopsy in a chronic leg ulcer should be lower for a patient who has any of the risk factors noted above. Be aware that ulcerating skin cancers may lack the classic appearance of typical skin cancers.6

For most BCCs, surgical excision will be required

Each BCC must be thoroughly evaluated for size, location, and histologic subtype. Surgical excision is the preferred treatment in most cases.5 Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery include skin cancers with aggressive histologic subtypes, such as infiltrative BCC, and tumors larger than 2 cm that are located on the extremities.1,5 Due to the limited amount of excess skin on the lower leg, skin flaps or grafts may be required.

Electrodessication and curettage, topical therapy with 5% imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, and cryotherapy are reserved for certain low-risk superficial and nodular BCCs.1,5 Radiation therapy is an option for tumors that are not amenable to surgery. Treatment is tailored to the patient’s needs based on age, medical history, and the characteristics of the skin cancer.

Inadequate treatment of BCCs can result in recurrences, which may appear 4 to 12 months after treatment.5 Close followup with regular full body skin exams is indicated.

Our patient was treated with Bactrim DS (800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) one tablet PO BID for 10 days and acetic acid soaks for the MRSA. While it was clear that the patient needed Mohs surgery, it was important to first address his lower extremity edema. He was evaluated by a vascular surgeon and resumed using compression stockings regularly.

The patient then underwent Mohs surgery.

After 2 stages of the surgery, the patient’s ulcer healed partially by secondary intention. After 5 months, the ulcer was covered with a split-thickness skin graft. Nine months after diagnosis, the patient had no clinical recurrence.

Physicians subsequently identified 2 BCCs on his face and scalp that were also treated with Mohs surgery. Our patient continues to have regular skin examinations.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jane Hwang, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Kunsan Air Base, PSC 2 Box 205, APO, AP 96264; jane.hwang.1@us.af.mil

A 63-year-old morbidly obese man presented to our clinic with a non-healing, slowly growing, painless ulcer on his right shin that he’d had for one year. It was not actively bleeding or draining, but the scab had come off one month earlier and the wound did not close. The patient denied any trauma to the area or foreign travel. Bacitracin and triamcinolone creams hadn’t helped.

Our patient’s medical history included diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and worsening venous insufficiency. He was not currently using compression stockings, but they had helped him in the past.

On examination, we noted a 3 x 3.5 cm well-demarcated, somewhat geometric, clean-based ulceration on the patient’s right medial shin (FIGURE 1A). There was no significant erythema, purulence, tenderness, warmth, or drainage of the ulcer. The base had seemingly normal granulation tissue. Woody induration, verrucous plaques, and confluent erythematous, violaceous, indurated patches were adjacent to the ulcer (FIGURE 1B). The patient also had severe pitting edema on his lower legs.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infiltrative basal cell carcinoma

In addition to our patient’s history of venous insufficiency, he’d also had a melanoma removed from his right shoulder 6 years earlier, and a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) removed from his upper back 2 years earlier. The chronic, non-healing nature of the ulcer prompted us to perform a punch biopsy, which revealed infiltrative BCC. We also did a wound culture, which showed a secondary infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The verrucous plaques next to the ulcer were the result of chronic venous stasis and lymphedema.

BCC is the most common type of cancer, estimated to comprise 80% of all skin cancers.1 It typically presents on the head and neck, but can occur in other locations. Eight percent of BCCs occur on the legs.2,3 Lower extremity BCC is more common in women, likely due to increased ultraviolet radiation exposure.2,4

BCC presents as erythematous and pearly macules, papules, nodules, ulcers, or scars, and can be pigmented. It may appear as a crusted ulcer (known as a “rodent ulcer”) with a rolled, translucent border and telangiectases.5 There are 5 major histologic subtypes of BCC: nodular, micronodular, superficial, morpheaform, and infiltrative.1,5 Infiltrative BCCs are an invasive subtype1,5 and may be more commonly associated with severe venous stasis,3 as was the case with our patient.

Although considered uncommon, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and BCC have been discovered in chronic leg ulcers.4,6 In fact, one report suggests that as many as 10% of chronic leg ulcers are malignant (31% BCC, 56% SCC).7 Thus, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in chronic leg ulcers.

Ulcerating BCC can mimic other types of leg ulcers

The differential diagnosis of a chronic leg ulcer includes venous or arterial ulcers, malignancies (SCC, BCC, lymphoma, melanoma), infectious ulcers (bacterial, deep fungal), pyoderma gangrenosum, and traumatic or factitial wounds (TABLE).1,4,5,8,9

Consider biopsy for ulcers that don't respond to treatment

The diagnosis of BCC in a leg ulcer is confirmed histologically. A punch or incisional biopsy should be taken at the edge of the ulcer, including the base.5,6 (For a Watch & Learn video that demonstrates how to perform a punch biopsy, go to http://bit.ly/punch_biopsy.) Providers may be concerned that biopsies could worsen a chronic wound; however, biopsy sites usually heal with no substantial complications.2,6,7 There are no guidelines on when to biopsy an ulcer, but it is reasonable to biopsy a leg ulcer that has not responded to 3 months of conservative treatment.2,7

Factors associated with malignancy in chronic leg ulcers include older age, abnormal excessive granulation tissue at wound edges, high clinical suspicion of cancer, and number of previous biopsies.7 The size and duration of the ulcer do not directly correlate with malignancy.7 The threshold for performing a diagnostic biopsy in a chronic leg ulcer should be lower for a patient who has any of the risk factors noted above. Be aware that ulcerating skin cancers may lack the classic appearance of typical skin cancers.6

For most BCCs, surgical excision will be required

Each BCC must be thoroughly evaluated for size, location, and histologic subtype. Surgical excision is the preferred treatment in most cases.5 Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery include skin cancers with aggressive histologic subtypes, such as infiltrative BCC, and tumors larger than 2 cm that are located on the extremities.1,5 Due to the limited amount of excess skin on the lower leg, skin flaps or grafts may be required.

Electrodessication and curettage, topical therapy with 5% imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, and cryotherapy are reserved for certain low-risk superficial and nodular BCCs.1,5 Radiation therapy is an option for tumors that are not amenable to surgery. Treatment is tailored to the patient’s needs based on age, medical history, and the characteristics of the skin cancer.

Inadequate treatment of BCCs can result in recurrences, which may appear 4 to 12 months after treatment.5 Close followup with regular full body skin exams is indicated.

Our patient was treated with Bactrim DS (800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) one tablet PO BID for 10 days and acetic acid soaks for the MRSA. While it was clear that the patient needed Mohs surgery, it was important to first address his lower extremity edema. He was evaluated by a vascular surgeon and resumed using compression stockings regularly.

The patient then underwent Mohs surgery.

After 2 stages of the surgery, the patient’s ulcer healed partially by secondary intention. After 5 months, the ulcer was covered with a split-thickness skin graft. Nine months after diagnosis, the patient had no clinical recurrence.

Physicians subsequently identified 2 BCCs on his face and scalp that were also treated with Mohs surgery. Our patient continues to have regular skin examinations.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jane Hwang, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Kunsan Air Base, PSC 2 Box 205, APO, AP 96264; jane.hwang.1@us.af.mil

1. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

2. Phillips TJ, Salman SM, Rogers GS. Nonhealing leg ulcers: a manifestation of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25;47-49.

3. Lutz ME, Davis MD, Otley CC. Infiltrating basal cell carcinoma in the setting of a venous ulcer. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:519-520.

4. Jankovic A, Binic I, Ljubenovic M. Basal cell carcinoma is not granulation tissue in the venous leg ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:182-184.

5. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 29. Epidermal nevi, neoplasms, and cysts. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

6. Yang D, Morrison BD, Vandongen YK, et al. Malignancy in chronic leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 1996;164:718-720.

7. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al; Angio-Dermatology Group Of The French Society Of Dermatology. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: the value of systematic wound biopsies: a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

8. Valencia IC, Falabella A, Kirsner RS, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:401-421.

9. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 30. Melanocytic nevi and neoplasms. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

1. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

2. Phillips TJ, Salman SM, Rogers GS. Nonhealing leg ulcers: a manifestation of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25;47-49.

3. Lutz ME, Davis MD, Otley CC. Infiltrating basal cell carcinoma in the setting of a venous ulcer. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:519-520.

4. Jankovic A, Binic I, Ljubenovic M. Basal cell carcinoma is not granulation tissue in the venous leg ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:182-184.

5. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 29. Epidermal nevi, neoplasms, and cysts. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

6. Yang D, Morrison BD, Vandongen YK, et al. Malignancy in chronic leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 1996;164:718-720.

7. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al; Angio-Dermatology Group Of The French Society Of Dermatology. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: the value of systematic wound biopsies: a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

8. Valencia IC, Falabella A, Kirsner RS, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:401-421.

9. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 30. Melanocytic nevi and neoplasms. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.