User login

75-year-old man • recent history of hand-foot-mouth disease • discolored fingernails and toenails lifting from the proximal end • Dx?

THE CASE

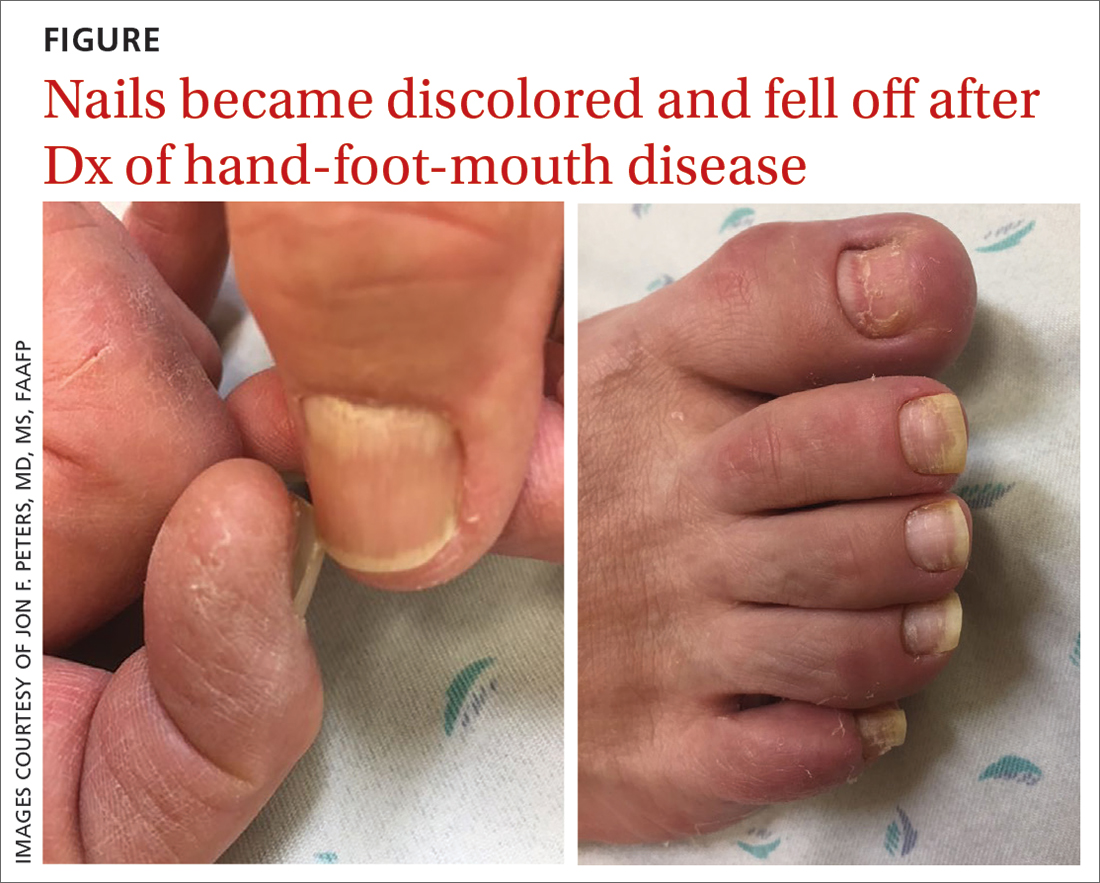

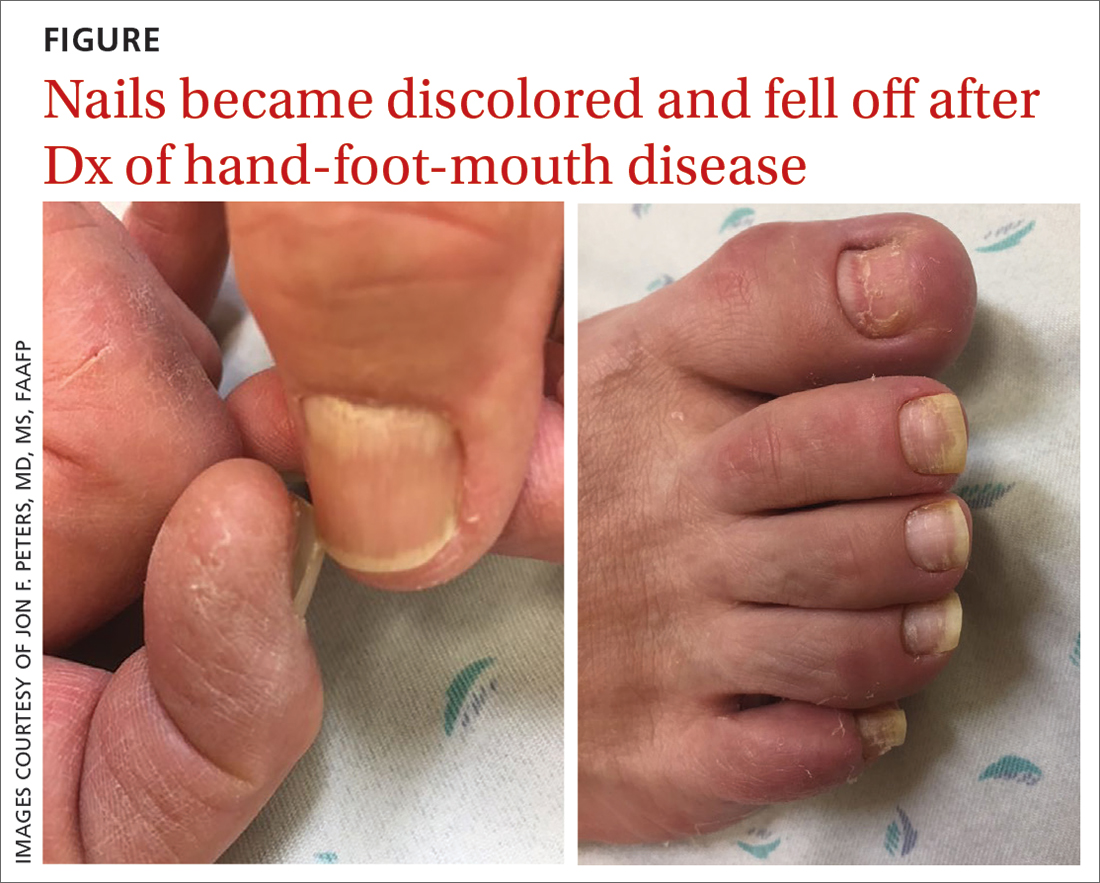

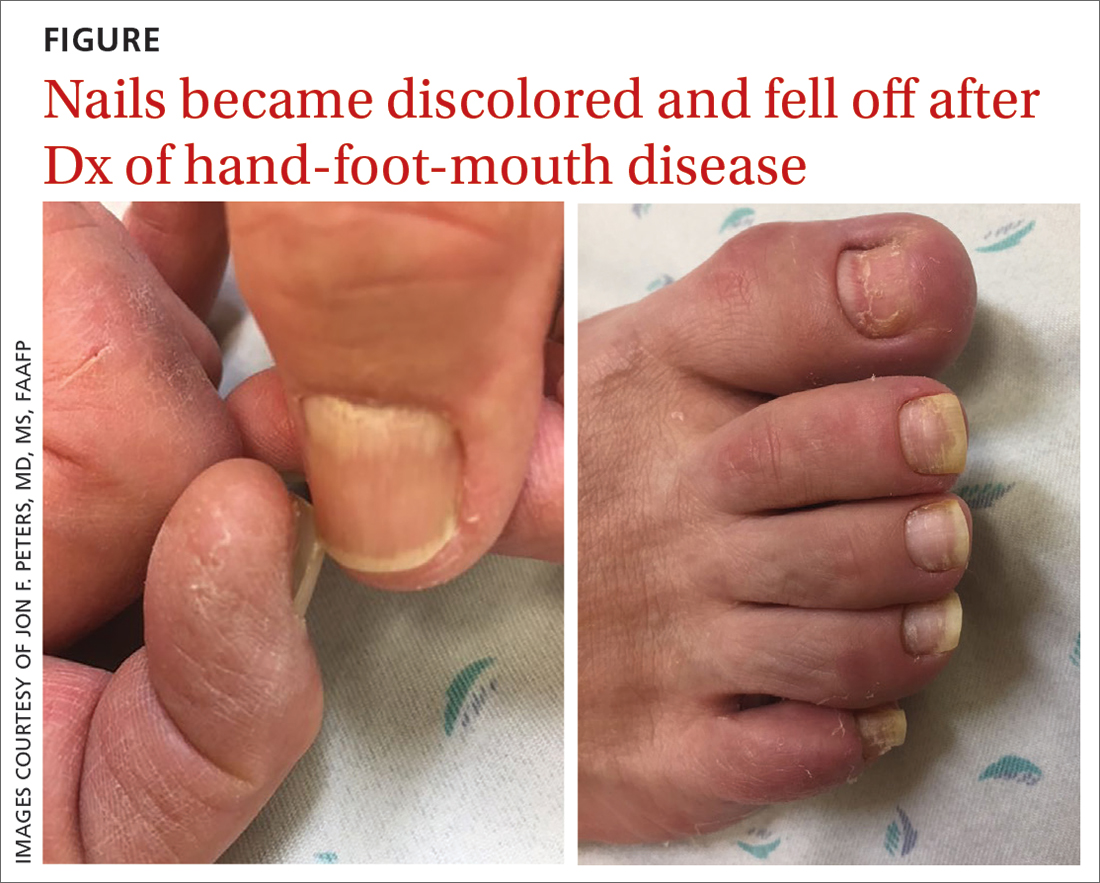

A 75-year-old man sought care from his primary care physician because his “fingernails and toenails [were] all falling off.” He did not feel ill and had no other complaints. His vital signs were unremarkable. He had no history of malignancies, chronic skin conditions, or systemic diseases. His fingernails and toenails were discolored and lifting from the proximal end of his nail beds (FIGURE). One of his great toenails had already fallen off, 1 thumb nail was minimally attached with the cuticle, and the rest of his nails were loose and in the process of separating from their nail beds. There was no nail pitting, rash, or joint swelling and tenderness.

The patient reported that while on vacation in Hawaii 3 weeks earlier, he had sought care at an urgent care clinic for a painless rash on his hands and the soles of his feet. At that time, he did not feel ill or have mouth ulcers, penile discharge, or arthralgia. There had been no recent changes to his prescription medications, which included finasteride, terazosin, omeprazole, and an albuterol inhaler. He denied taking over-the-counter medications or supplements.

The physical exam at the urgent care had revealed multiple blotchy, dark, 0.5- to 1-cm nonpruritic lesions that were desquamating. No oral lesions were seen. He had been given a diagnosis of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) and reassured that it would resolve on its own in about 10 days.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Several possible diagnoses for nail disorders came to mind with this patient, including onychomycosis, onychoschizia, onycholysis, and onychomadesis.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nail that affects toenails more often than fingernails.1 The most common form is distal subungual onychomycosis, which begins distally and slowly migrates proximally through the nail matrix.1 Often onychomycosis affects only a few nails unless the patient is elderly or has comorbid conditions, and the nails rarely separate from the nail bed.

Onychoschizia involves lamellar splitting and peeling of the dorsal surface of the nail plate.2 Usually white discolorations appear on the distal edges of the nail.3 It is more common in women than in men and is often caused by nail dehydration from repeated excessive immersion in water with detergents or recurrent application of nail polish.2 However, the nails do not separate from the nail bed, and usually only the fingernails are involved.

Onycholysis is a nail attachment disorder in which the nail plate distally separates from the nail bed. Areas of separation will appear white or yellow. There are many etiologies for onycholysis, including trauma, psoriasis, fungal infection, and contact irritant reactions.3 It also can be caused by medications and thyroid disease.3,4

Continue to: Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis, sometimes considered a severe form of Beau’s line,5,6 is defined by the spontaneous separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. Although the nail will initially remain attached, proximal shedding will eventually occur.7 When several nails are involved, a systemic source—such as an acute infection, autoimmune disease, medication, malignancy (eg, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), Kawasaki disease, skin disorders (eg, pemphigus vulgaris or keratosis punctata et planters), or chemotherapy—may be the cause.6-8 If only a few nails are involved, it may be associated with trauma, and in rare cases, onychomadesis can be idiopathic.5,7

In this case, all signs pointed to onychomadesis. All of the patient’s nails were affected (discolored and lifting), his nail loss involved spontaneous proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix, and he had a recent previous infection: HFMD.

DISCUSSION

Onychomadesis is a rare nail-shedding disorder thought to be caused by the temporary arrest of the nail matrix.8 It is a potential late complication of infection, such as HFMD,9 and was first reported in children in Chicago in 2000.10 Since then, onychomadesis has been noted in children in many countries.8 Reports of onychomadesis following HFMD in adults are rare, but it may be underreported because HFMD is more common in children and symptoms are usually minor in adults.11

Molecular studies have associated onychomadesis with coxsackievirus (CV)A6 and CVA10.4 Other serotypes associated with onychomadesis include CVB1, CVB2, CVA5, CVA16, and enteroviruses 71 and 9.4 Most known outbreaks seem to be caused by CVA6.4

No treatment is needed for onychomadesis; physicians can reassure patients that normal nail growth will begin within 1 to 4 months. Because onychomadesis is rare, it does not have its own billing code, so one can use code L60.8 for “Other nail disorders.”12

Our patient was seen in the primary care clinic 3 months after his initial visit. At that time, his nails were no longer discolored and no other abnormalities were present. All of the nails on his fingers and toes were firmly attached and growing normally.

THE TAKEAWAY

The sudden asymptomatic loss of multiple fingernails and toenails—especially with proximal nail shedding—is a rare disorder known as onychomadesis. It can be caused by various etiologies and can be a late complication of HFMD or other viral infections. Onychomadesis should be considered when evaluating older patients, particularly when all of their nails are involved after a viral infection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jon F. Peters, MD, MS, FAAFP, 14486 SE Lyon Court, Happy Valley, OR 97086; peters-nw@comcast.net

1. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677-678.

2. Sparavigna A, Tenconi B, La Penna L. Efficacy and tolerability of a biomineral formulation for treatment of onychoschizia: a randomized trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019:12:355-362. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187305

3. Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.153002

4. Cleveland Clinic. Onycholysis. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22903-onycholysis

5. Chiu H-H, Liu M-T, Chung W-H, et al. The mechanism of onychomadesis (nail shedding) and Beau’s lines following hand-foot-mouth disease. Viruses. 2019;11:522. doi: 10.3390/v11060522

6. Suchonwanit P, Nitayavardhana S. Idiopathic sporadic onychomadesis of toenails. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:6451327. doi: 10.1155/2016/6451327

7. Hardin J, Haber RM. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:592-596. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13339

8. Li D, Yang W, Xing X, et al. Onychomadesis and potential association with HFMD outbreak in a kindergarten in Hubei providence, China, 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019:19:995. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4560-8

9. Chiu HH, Wu CS, Lan CE. Onychomadesis: a late complication of hand, foot, and mouth disease. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:243-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.034

10. Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01702.x

11. Scarfi F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Derm. 2014;53:1392-1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05774.x

12. ICD10Data.com. 2023 ICD-10-CM codes. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/codes

THE CASE

A 75-year-old man sought care from his primary care physician because his “fingernails and toenails [were] all falling off.” He did not feel ill and had no other complaints. His vital signs were unremarkable. He had no history of malignancies, chronic skin conditions, or systemic diseases. His fingernails and toenails were discolored and lifting from the proximal end of his nail beds (FIGURE). One of his great toenails had already fallen off, 1 thumb nail was minimally attached with the cuticle, and the rest of his nails were loose and in the process of separating from their nail beds. There was no nail pitting, rash, or joint swelling and tenderness.

The patient reported that while on vacation in Hawaii 3 weeks earlier, he had sought care at an urgent care clinic for a painless rash on his hands and the soles of his feet. At that time, he did not feel ill or have mouth ulcers, penile discharge, or arthralgia. There had been no recent changes to his prescription medications, which included finasteride, terazosin, omeprazole, and an albuterol inhaler. He denied taking over-the-counter medications or supplements.

The physical exam at the urgent care had revealed multiple blotchy, dark, 0.5- to 1-cm nonpruritic lesions that were desquamating. No oral lesions were seen. He had been given a diagnosis of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) and reassured that it would resolve on its own in about 10 days.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Several possible diagnoses for nail disorders came to mind with this patient, including onychomycosis, onychoschizia, onycholysis, and onychomadesis.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nail that affects toenails more often than fingernails.1 The most common form is distal subungual onychomycosis, which begins distally and slowly migrates proximally through the nail matrix.1 Often onychomycosis affects only a few nails unless the patient is elderly or has comorbid conditions, and the nails rarely separate from the nail bed.

Onychoschizia involves lamellar splitting and peeling of the dorsal surface of the nail plate.2 Usually white discolorations appear on the distal edges of the nail.3 It is more common in women than in men and is often caused by nail dehydration from repeated excessive immersion in water with detergents or recurrent application of nail polish.2 However, the nails do not separate from the nail bed, and usually only the fingernails are involved.

Onycholysis is a nail attachment disorder in which the nail plate distally separates from the nail bed. Areas of separation will appear white or yellow. There are many etiologies for onycholysis, including trauma, psoriasis, fungal infection, and contact irritant reactions.3 It also can be caused by medications and thyroid disease.3,4

Continue to: Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis, sometimes considered a severe form of Beau’s line,5,6 is defined by the spontaneous separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. Although the nail will initially remain attached, proximal shedding will eventually occur.7 When several nails are involved, a systemic source—such as an acute infection, autoimmune disease, medication, malignancy (eg, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), Kawasaki disease, skin disorders (eg, pemphigus vulgaris or keratosis punctata et planters), or chemotherapy—may be the cause.6-8 If only a few nails are involved, it may be associated with trauma, and in rare cases, onychomadesis can be idiopathic.5,7

In this case, all signs pointed to onychomadesis. All of the patient’s nails were affected (discolored and lifting), his nail loss involved spontaneous proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix, and he had a recent previous infection: HFMD.

DISCUSSION

Onychomadesis is a rare nail-shedding disorder thought to be caused by the temporary arrest of the nail matrix.8 It is a potential late complication of infection, such as HFMD,9 and was first reported in children in Chicago in 2000.10 Since then, onychomadesis has been noted in children in many countries.8 Reports of onychomadesis following HFMD in adults are rare, but it may be underreported because HFMD is more common in children and symptoms are usually minor in adults.11

Molecular studies have associated onychomadesis with coxsackievirus (CV)A6 and CVA10.4 Other serotypes associated with onychomadesis include CVB1, CVB2, CVA5, CVA16, and enteroviruses 71 and 9.4 Most known outbreaks seem to be caused by CVA6.4

No treatment is needed for onychomadesis; physicians can reassure patients that normal nail growth will begin within 1 to 4 months. Because onychomadesis is rare, it does not have its own billing code, so one can use code L60.8 for “Other nail disorders.”12

Our patient was seen in the primary care clinic 3 months after his initial visit. At that time, his nails were no longer discolored and no other abnormalities were present. All of the nails on his fingers and toes were firmly attached and growing normally.

THE TAKEAWAY

The sudden asymptomatic loss of multiple fingernails and toenails—especially with proximal nail shedding—is a rare disorder known as onychomadesis. It can be caused by various etiologies and can be a late complication of HFMD or other viral infections. Onychomadesis should be considered when evaluating older patients, particularly when all of their nails are involved after a viral infection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jon F. Peters, MD, MS, FAAFP, 14486 SE Lyon Court, Happy Valley, OR 97086; peters-nw@comcast.net

THE CASE

A 75-year-old man sought care from his primary care physician because his “fingernails and toenails [were] all falling off.” He did not feel ill and had no other complaints. His vital signs were unremarkable. He had no history of malignancies, chronic skin conditions, or systemic diseases. His fingernails and toenails were discolored and lifting from the proximal end of his nail beds (FIGURE). One of his great toenails had already fallen off, 1 thumb nail was minimally attached with the cuticle, and the rest of his nails were loose and in the process of separating from their nail beds. There was no nail pitting, rash, or joint swelling and tenderness.

The patient reported that while on vacation in Hawaii 3 weeks earlier, he had sought care at an urgent care clinic for a painless rash on his hands and the soles of his feet. At that time, he did not feel ill or have mouth ulcers, penile discharge, or arthralgia. There had been no recent changes to his prescription medications, which included finasteride, terazosin, omeprazole, and an albuterol inhaler. He denied taking over-the-counter medications or supplements.

The physical exam at the urgent care had revealed multiple blotchy, dark, 0.5- to 1-cm nonpruritic lesions that were desquamating. No oral lesions were seen. He had been given a diagnosis of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) and reassured that it would resolve on its own in about 10 days.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Several possible diagnoses for nail disorders came to mind with this patient, including onychomycosis, onychoschizia, onycholysis, and onychomadesis.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nail that affects toenails more often than fingernails.1 The most common form is distal subungual onychomycosis, which begins distally and slowly migrates proximally through the nail matrix.1 Often onychomycosis affects only a few nails unless the patient is elderly or has comorbid conditions, and the nails rarely separate from the nail bed.

Onychoschizia involves lamellar splitting and peeling of the dorsal surface of the nail plate.2 Usually white discolorations appear on the distal edges of the nail.3 It is more common in women than in men and is often caused by nail dehydration from repeated excessive immersion in water with detergents or recurrent application of nail polish.2 However, the nails do not separate from the nail bed, and usually only the fingernails are involved.

Onycholysis is a nail attachment disorder in which the nail plate distally separates from the nail bed. Areas of separation will appear white or yellow. There are many etiologies for onycholysis, including trauma, psoriasis, fungal infection, and contact irritant reactions.3 It also can be caused by medications and thyroid disease.3,4

Continue to: Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis, sometimes considered a severe form of Beau’s line,5,6 is defined by the spontaneous separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. Although the nail will initially remain attached, proximal shedding will eventually occur.7 When several nails are involved, a systemic source—such as an acute infection, autoimmune disease, medication, malignancy (eg, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), Kawasaki disease, skin disorders (eg, pemphigus vulgaris or keratosis punctata et planters), or chemotherapy—may be the cause.6-8 If only a few nails are involved, it may be associated with trauma, and in rare cases, onychomadesis can be idiopathic.5,7

In this case, all signs pointed to onychomadesis. All of the patient’s nails were affected (discolored and lifting), his nail loss involved spontaneous proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix, and he had a recent previous infection: HFMD.

DISCUSSION

Onychomadesis is a rare nail-shedding disorder thought to be caused by the temporary arrest of the nail matrix.8 It is a potential late complication of infection, such as HFMD,9 and was first reported in children in Chicago in 2000.10 Since then, onychomadesis has been noted in children in many countries.8 Reports of onychomadesis following HFMD in adults are rare, but it may be underreported because HFMD is more common in children and symptoms are usually minor in adults.11

Molecular studies have associated onychomadesis with coxsackievirus (CV)A6 and CVA10.4 Other serotypes associated with onychomadesis include CVB1, CVB2, CVA5, CVA16, and enteroviruses 71 and 9.4 Most known outbreaks seem to be caused by CVA6.4

No treatment is needed for onychomadesis; physicians can reassure patients that normal nail growth will begin within 1 to 4 months. Because onychomadesis is rare, it does not have its own billing code, so one can use code L60.8 for “Other nail disorders.”12

Our patient was seen in the primary care clinic 3 months after his initial visit. At that time, his nails were no longer discolored and no other abnormalities were present. All of the nails on his fingers and toes were firmly attached and growing normally.

THE TAKEAWAY

The sudden asymptomatic loss of multiple fingernails and toenails—especially with proximal nail shedding—is a rare disorder known as onychomadesis. It can be caused by various etiologies and can be a late complication of HFMD or other viral infections. Onychomadesis should be considered when evaluating older patients, particularly when all of their nails are involved after a viral infection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jon F. Peters, MD, MS, FAAFP, 14486 SE Lyon Court, Happy Valley, OR 97086; peters-nw@comcast.net

1. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677-678.

2. Sparavigna A, Tenconi B, La Penna L. Efficacy and tolerability of a biomineral formulation for treatment of onychoschizia: a randomized trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019:12:355-362. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187305

3. Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.153002

4. Cleveland Clinic. Onycholysis. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22903-onycholysis

5. Chiu H-H, Liu M-T, Chung W-H, et al. The mechanism of onychomadesis (nail shedding) and Beau’s lines following hand-foot-mouth disease. Viruses. 2019;11:522. doi: 10.3390/v11060522

6. Suchonwanit P, Nitayavardhana S. Idiopathic sporadic onychomadesis of toenails. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:6451327. doi: 10.1155/2016/6451327

7. Hardin J, Haber RM. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:592-596. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13339

8. Li D, Yang W, Xing X, et al. Onychomadesis and potential association with HFMD outbreak in a kindergarten in Hubei providence, China, 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019:19:995. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4560-8

9. Chiu HH, Wu CS, Lan CE. Onychomadesis: a late complication of hand, foot, and mouth disease. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:243-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.034

10. Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01702.x

11. Scarfi F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Derm. 2014;53:1392-1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05774.x

12. ICD10Data.com. 2023 ICD-10-CM codes. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/codes

1. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677-678.

2. Sparavigna A, Tenconi B, La Penna L. Efficacy and tolerability of a biomineral formulation for treatment of onychoschizia: a randomized trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019:12:355-362. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187305

3. Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.153002

4. Cleveland Clinic. Onycholysis. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22903-onycholysis

5. Chiu H-H, Liu M-T, Chung W-H, et al. The mechanism of onychomadesis (nail shedding) and Beau’s lines following hand-foot-mouth disease. Viruses. 2019;11:522. doi: 10.3390/v11060522

6. Suchonwanit P, Nitayavardhana S. Idiopathic sporadic onychomadesis of toenails. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:6451327. doi: 10.1155/2016/6451327

7. Hardin J, Haber RM. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:592-596. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13339

8. Li D, Yang W, Xing X, et al. Onychomadesis and potential association with HFMD outbreak in a kindergarten in Hubei providence, China, 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019:19:995. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4560-8

9. Chiu HH, Wu CS, Lan CE. Onychomadesis: a late complication of hand, foot, and mouth disease. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:243-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.034

10. Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01702.x

11. Scarfi F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Derm. 2014;53:1392-1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05774.x

12. ICD10Data.com. 2023 ICD-10-CM codes. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/codes

► Recent history of hand-foot-mouth disease

► Discolored fingernails and toenails lifting from the proximal end