User login

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Practice Gap

Tattoos have become increasingly prevalent in Western culture, with approximately 1 in 4 Americans having at least 1 tattoo. Individuals invest money, time, and even pain in getting tattoos, many of which hold special personal, family, or religious significance.1 Various cutaneous pathologies may arise in areas of the skin with tattoos, including malignancies and inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigment, and in these cases, surgical management may be indicated.2,3

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) such as superficial basal cell carcinomas on broadly sun-damaged areas (eg, trunk, torso), squamous cell carcinomas, reactive keratoacanthomas, and reactive pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to occur in or near areas of the skin with tattoos.2 Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is the standard of care for removing NMSCs, particularly when they manifest in cosmetically sensitive areas.4 This treatment option allows for careful guided resection of tumors to minimize the risk for recurrence; it also preserves healthy tissue, which typically results in a smaller radial defect after the procedure is complete.

Chronic reactions to tattoo pigment may include granulomatous tattoo reactions and pseudolymphomas.3 Treatment options may include immunosuppressives such as intralesional triamcinolone as well as pigment destruction via lasers5; however, not all tattoos are responsive to these treatments. Surgical excision is an effective and definitive treatment in this context, as tattoo pigment resides in or above the mid dermis to a depth of approximately 400 μm. Intradermal excision effectively removes the antigenic pigment.5

In these clinical scenarios, patients may be hesitant to pursue surgical treatment due to concerns that it may alter tattoo appearance. Many clinicians and surgeons may consider definitive treatment and tattoo preservation to be mutually exclusive, but this is not always the case. We propose a technique that utilizes conservative thickness layers (CTL) to minimize disruption to the appearance of tattoos in MMS for treatment of cutaneous malignancies as well as intradermal excision of tattoo pigment in the setting of chronic inflammatory tattoo reactions.

The Technique

In the appropriate clinical context, CTL can effectively result in defects that heal well by secondary intention and minimize collateral tissue distortion.4 Lesions manifesting in or near tattooed skin often are responsive to treatment with CTL; furthermore, CTL may preserve some deeper tattoo pigment, resulting in only partial loss of the tattooed skin.

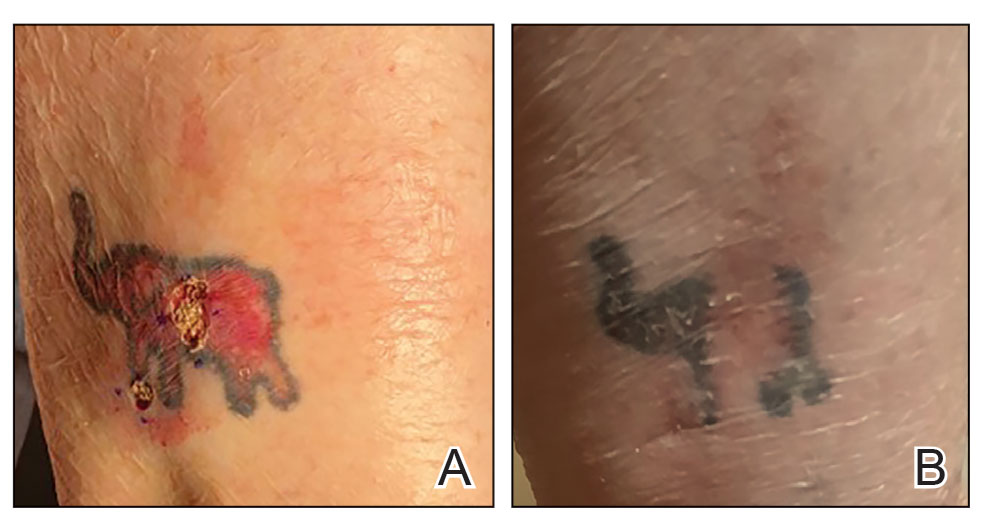

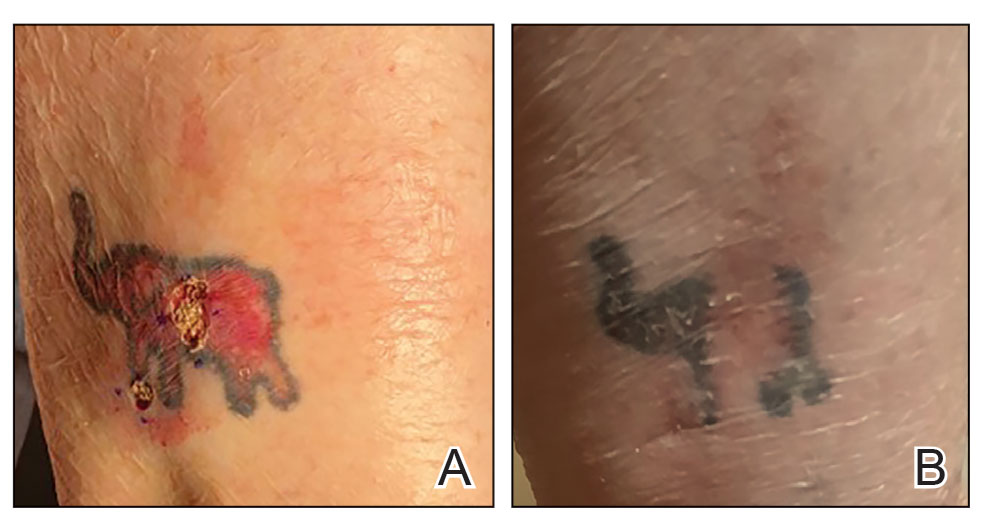

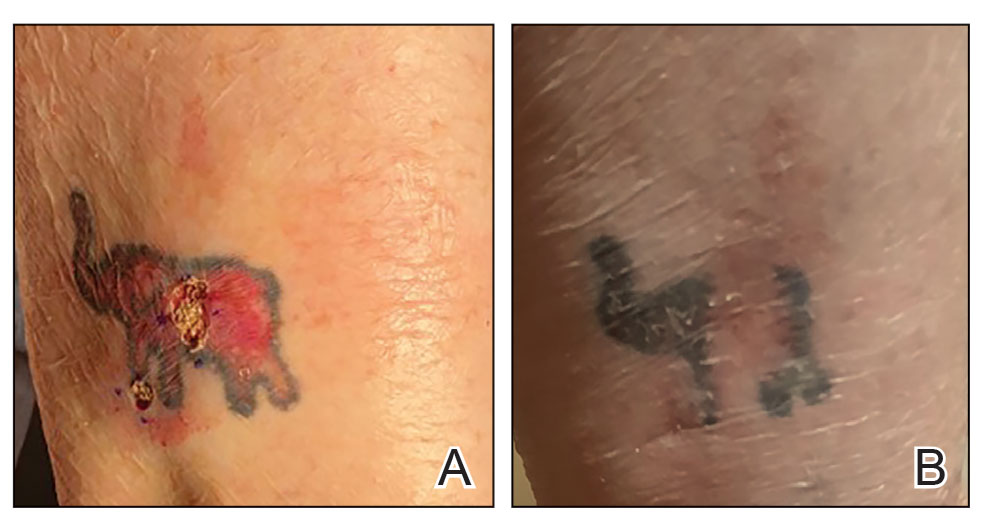

Conservative thickness layers are performed intradermally, similar to removing traditional layers in MMS. For treatment of NMSCs, a margin is scored around the lesion, and then the blade is passed carefully under the lesion nearly parallel to the skin through an intradermal plane. It is important to avoid entering the subcuticular fat (Figure 1). The tissue then is processed normally in the Mohs laboratory for complete circumferential margin evaluation. If necessary and possible, subsequent layers also can be performed in the intradermal plane. Once total circumferential margin control is obtained, the wound is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. As these processes occur, we have found that wound contraction is less likely with the dermis intact, resulting in less impact on the overall appearance of the tattoo (Figures 1 and 2). For very thin lesions, resultant defects may retain some residual tattoo pigment. The residual scars also may be responsive to tattoo revision, although a period of monitoring for recurrence should be considered if there is concern that revising the tattoo could obscure early recurrent tumors. From our experience, utilizing CTL for NMSCs that arise within or near tattoos results in favorable preservation of the tattoo appearance and high patient satisfaction.

The procedure is performed similarly for removal of allergenic tattoo pigment, with careful excision to the mid dermis. Since the areas affected by the cutaneous reaction may be relatively large, surgical precision is required to maintain a uniform depth to remove the tattoo pigment and preserve the deep dermis (Figure 2). Once removed, the defect can be left to granulate and heal by secondary intention. If the patient wants to have the tattoo revised in the future, it would be prudent to utilize pigment that the patient has responded favorably to. In our experience, this approach is effective and yields high patient satisfaction and minimizes morbidity.

Practice Implications

Tattoos often hold special meaning for patients; therefore, treatment of pathologies arising in or near tattooed skin should emphasize maintaining the appearance of the tattoo while still being effective. Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions for allergic reactions to tattoo pigment are an effective treatment strategy that clinicians may consider.

One shortcoming of using CTL for MMS is the need for subsequent layers to clear the tumor; however, data suggest that first-stage cure rates are extremely high even with CTL for appropriately selected patients, with clearance of nearly 80% of tumors on the first stage. Tumors that may be most responsive to CTL include exophytic NMSCs and those arising in areas with a thicker dermis, including the back, legs, and scalp, although other locations including the face, hands, shins, ankles, and feet also may be well suited for CTL.4 Another shortcoming of CTL is that skin cancers arising in tattoos may not be considered appropriate for MMS based on the 2012

Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions of tattoo pigment are both effective techniques of minimizing disruption of tattoos while effectively treating patients.

- Roggenkamp H, Nicholls A, Pierre JM. Tattoos as a window to the psyche: how talking about skin art can inform psychiatric practice. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7:148-158. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i3.148

- Rubatto M, Gelato F, Mastorino L, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer arising on tattoos. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E155-E156. doi:10.1111/ijd.16381

- Atwater AR, Bembry R, Reeder M. Tattoo hypersensitivity reactions: inky business. Cutis. 2020;106:64-67. doi:10.12788/cutis.0028

- Tolkachjov SN, Cappel JA, Bryant EA, et al. Conservative thickness layers in Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1128-1134. doi:10.1111/ijd.14043

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.155068

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009.

- Amthor Croley JA. Current controversies in mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2019;104:E29-E31.

Practice Gap

Tattoos have become increasingly prevalent in Western culture, with approximately 1 in 4 Americans having at least 1 tattoo. Individuals invest money, time, and even pain in getting tattoos, many of which hold special personal, family, or religious significance.1 Various cutaneous pathologies may arise in areas of the skin with tattoos, including malignancies and inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigment, and in these cases, surgical management may be indicated.2,3

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) such as superficial basal cell carcinomas on broadly sun-damaged areas (eg, trunk, torso), squamous cell carcinomas, reactive keratoacanthomas, and reactive pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to occur in or near areas of the skin with tattoos.2 Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is the standard of care for removing NMSCs, particularly when they manifest in cosmetically sensitive areas.4 This treatment option allows for careful guided resection of tumors to minimize the risk for recurrence; it also preserves healthy tissue, which typically results in a smaller radial defect after the procedure is complete.

Chronic reactions to tattoo pigment may include granulomatous tattoo reactions and pseudolymphomas.3 Treatment options may include immunosuppressives such as intralesional triamcinolone as well as pigment destruction via lasers5; however, not all tattoos are responsive to these treatments. Surgical excision is an effective and definitive treatment in this context, as tattoo pigment resides in or above the mid dermis to a depth of approximately 400 μm. Intradermal excision effectively removes the antigenic pigment.5

In these clinical scenarios, patients may be hesitant to pursue surgical treatment due to concerns that it may alter tattoo appearance. Many clinicians and surgeons may consider definitive treatment and tattoo preservation to be mutually exclusive, but this is not always the case. We propose a technique that utilizes conservative thickness layers (CTL) to minimize disruption to the appearance of tattoos in MMS for treatment of cutaneous malignancies as well as intradermal excision of tattoo pigment in the setting of chronic inflammatory tattoo reactions.

The Technique

In the appropriate clinical context, CTL can effectively result in defects that heal well by secondary intention and minimize collateral tissue distortion.4 Lesions manifesting in or near tattooed skin often are responsive to treatment with CTL; furthermore, CTL may preserve some deeper tattoo pigment, resulting in only partial loss of the tattooed skin.

Conservative thickness layers are performed intradermally, similar to removing traditional layers in MMS. For treatment of NMSCs, a margin is scored around the lesion, and then the blade is passed carefully under the lesion nearly parallel to the skin through an intradermal plane. It is important to avoid entering the subcuticular fat (Figure 1). The tissue then is processed normally in the Mohs laboratory for complete circumferential margin evaluation. If necessary and possible, subsequent layers also can be performed in the intradermal plane. Once total circumferential margin control is obtained, the wound is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. As these processes occur, we have found that wound contraction is less likely with the dermis intact, resulting in less impact on the overall appearance of the tattoo (Figures 1 and 2). For very thin lesions, resultant defects may retain some residual tattoo pigment. The residual scars also may be responsive to tattoo revision, although a period of monitoring for recurrence should be considered if there is concern that revising the tattoo could obscure early recurrent tumors. From our experience, utilizing CTL for NMSCs that arise within or near tattoos results in favorable preservation of the tattoo appearance and high patient satisfaction.

The procedure is performed similarly for removal of allergenic tattoo pigment, with careful excision to the mid dermis. Since the areas affected by the cutaneous reaction may be relatively large, surgical precision is required to maintain a uniform depth to remove the tattoo pigment and preserve the deep dermis (Figure 2). Once removed, the defect can be left to granulate and heal by secondary intention. If the patient wants to have the tattoo revised in the future, it would be prudent to utilize pigment that the patient has responded favorably to. In our experience, this approach is effective and yields high patient satisfaction and minimizes morbidity.

Practice Implications

Tattoos often hold special meaning for patients; therefore, treatment of pathologies arising in or near tattooed skin should emphasize maintaining the appearance of the tattoo while still being effective. Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions for allergic reactions to tattoo pigment are an effective treatment strategy that clinicians may consider.

One shortcoming of using CTL for MMS is the need for subsequent layers to clear the tumor; however, data suggest that first-stage cure rates are extremely high even with CTL for appropriately selected patients, with clearance of nearly 80% of tumors on the first stage. Tumors that may be most responsive to CTL include exophytic NMSCs and those arising in areas with a thicker dermis, including the back, legs, and scalp, although other locations including the face, hands, shins, ankles, and feet also may be well suited for CTL.4 Another shortcoming of CTL is that skin cancers arising in tattoos may not be considered appropriate for MMS based on the 2012

Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions of tattoo pigment are both effective techniques of minimizing disruption of tattoos while effectively treating patients.

Practice Gap

Tattoos have become increasingly prevalent in Western culture, with approximately 1 in 4 Americans having at least 1 tattoo. Individuals invest money, time, and even pain in getting tattoos, many of which hold special personal, family, or religious significance.1 Various cutaneous pathologies may arise in areas of the skin with tattoos, including malignancies and inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigment, and in these cases, surgical management may be indicated.2,3

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) such as superficial basal cell carcinomas on broadly sun-damaged areas (eg, trunk, torso), squamous cell carcinomas, reactive keratoacanthomas, and reactive pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to occur in or near areas of the skin with tattoos.2 Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is the standard of care for removing NMSCs, particularly when they manifest in cosmetically sensitive areas.4 This treatment option allows for careful guided resection of tumors to minimize the risk for recurrence; it also preserves healthy tissue, which typically results in a smaller radial defect after the procedure is complete.

Chronic reactions to tattoo pigment may include granulomatous tattoo reactions and pseudolymphomas.3 Treatment options may include immunosuppressives such as intralesional triamcinolone as well as pigment destruction via lasers5; however, not all tattoos are responsive to these treatments. Surgical excision is an effective and definitive treatment in this context, as tattoo pigment resides in or above the mid dermis to a depth of approximately 400 μm. Intradermal excision effectively removes the antigenic pigment.5

In these clinical scenarios, patients may be hesitant to pursue surgical treatment due to concerns that it may alter tattoo appearance. Many clinicians and surgeons may consider definitive treatment and tattoo preservation to be mutually exclusive, but this is not always the case. We propose a technique that utilizes conservative thickness layers (CTL) to minimize disruption to the appearance of tattoos in MMS for treatment of cutaneous malignancies as well as intradermal excision of tattoo pigment in the setting of chronic inflammatory tattoo reactions.

The Technique

In the appropriate clinical context, CTL can effectively result in defects that heal well by secondary intention and minimize collateral tissue distortion.4 Lesions manifesting in or near tattooed skin often are responsive to treatment with CTL; furthermore, CTL may preserve some deeper tattoo pigment, resulting in only partial loss of the tattooed skin.

Conservative thickness layers are performed intradermally, similar to removing traditional layers in MMS. For treatment of NMSCs, a margin is scored around the lesion, and then the blade is passed carefully under the lesion nearly parallel to the skin through an intradermal plane. It is important to avoid entering the subcuticular fat (Figure 1). The tissue then is processed normally in the Mohs laboratory for complete circumferential margin evaluation. If necessary and possible, subsequent layers also can be performed in the intradermal plane. Once total circumferential margin control is obtained, the wound is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. As these processes occur, we have found that wound contraction is less likely with the dermis intact, resulting in less impact on the overall appearance of the tattoo (Figures 1 and 2). For very thin lesions, resultant defects may retain some residual tattoo pigment. The residual scars also may be responsive to tattoo revision, although a period of monitoring for recurrence should be considered if there is concern that revising the tattoo could obscure early recurrent tumors. From our experience, utilizing CTL for NMSCs that arise within or near tattoos results in favorable preservation of the tattoo appearance and high patient satisfaction.

The procedure is performed similarly for removal of allergenic tattoo pigment, with careful excision to the mid dermis. Since the areas affected by the cutaneous reaction may be relatively large, surgical precision is required to maintain a uniform depth to remove the tattoo pigment and preserve the deep dermis (Figure 2). Once removed, the defect can be left to granulate and heal by secondary intention. If the patient wants to have the tattoo revised in the future, it would be prudent to utilize pigment that the patient has responded favorably to. In our experience, this approach is effective and yields high patient satisfaction and minimizes morbidity.

Practice Implications

Tattoos often hold special meaning for patients; therefore, treatment of pathologies arising in or near tattooed skin should emphasize maintaining the appearance of the tattoo while still being effective. Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions for allergic reactions to tattoo pigment are an effective treatment strategy that clinicians may consider.

One shortcoming of using CTL for MMS is the need for subsequent layers to clear the tumor; however, data suggest that first-stage cure rates are extremely high even with CTL for appropriately selected patients, with clearance of nearly 80% of tumors on the first stage. Tumors that may be most responsive to CTL include exophytic NMSCs and those arising in areas with a thicker dermis, including the back, legs, and scalp, although other locations including the face, hands, shins, ankles, and feet also may be well suited for CTL.4 Another shortcoming of CTL is that skin cancers arising in tattoos may not be considered appropriate for MMS based on the 2012

Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions of tattoo pigment are both effective techniques of minimizing disruption of tattoos while effectively treating patients.

- Roggenkamp H, Nicholls A, Pierre JM. Tattoos as a window to the psyche: how talking about skin art can inform psychiatric practice. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7:148-158. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i3.148

- Rubatto M, Gelato F, Mastorino L, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer arising on tattoos. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E155-E156. doi:10.1111/ijd.16381

- Atwater AR, Bembry R, Reeder M. Tattoo hypersensitivity reactions: inky business. Cutis. 2020;106:64-67. doi:10.12788/cutis.0028

- Tolkachjov SN, Cappel JA, Bryant EA, et al. Conservative thickness layers in Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1128-1134. doi:10.1111/ijd.14043

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.155068

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009.

- Amthor Croley JA. Current controversies in mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2019;104:E29-E31.

- Roggenkamp H, Nicholls A, Pierre JM. Tattoos as a window to the psyche: how talking about skin art can inform psychiatric practice. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7:148-158. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i3.148

- Rubatto M, Gelato F, Mastorino L, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer arising on tattoos. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E155-E156. doi:10.1111/ijd.16381

- Atwater AR, Bembry R, Reeder M. Tattoo hypersensitivity reactions: inky business. Cutis. 2020;106:64-67. doi:10.12788/cutis.0028

- Tolkachjov SN, Cappel JA, Bryant EA, et al. Conservative thickness layers in Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1128-1134. doi:10.1111/ijd.14043

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.155068

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009.

- Amthor Croley JA. Current controversies in mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2019;104:E29-E31.

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Continuous Testing Method for Contact Allergy to Topical Therapies in the Management of Chronic and Postoperative Wounds

Patients who undergo cutaneous surgery and chronic wound care often are exposed to various topical

Practice Gap

Contact allergies are common in patients with postoperative or chronic wounds. When patch tested, approximately 80% of patients with chronic venous ulcers demonstrated at least 1 positive allergic reaction based on a Canadian study.3 Similarly, postoperative ACD in dermatologic surgery occurs in more than 1.6% of cases in North America and Europe, a rate that is similar to or higher than the rate of postoperative infection, approximately 1% to 2%.4 Postoperative patients and those with chronic wounds have multiple risk factors for ACD. Firstly, applying topical therapies to inflamed or compromised skin increases the risk for contact sensitization.5 Additionally, multiple topical therapies containing known allergenic components may be recommended for wound care, including impregnated or organic dressings, antibiotic ointments, adhesives, antiseptic washes, and topical therapies containing inactive ingredients such as lanolin derivatives.6 Contact with numerous compounds at the same time increases the risk for a contact allergy as well as co-sensitization.7 Similarly, the longer topical agents are applied, the greater the risk for a contact allergy, with sensitization liable to occur at any point during treatment.

Preventive topical antibiotics have garnered a negative reputation among dermatologists, often due to varying data on their efficacy and the overuse of highly allergenic over-the-counter topical antibiotics such as neomycin.8 However, data also have suggested that topical antibiotics can reduce postoperative infections in higher risk surgical cases, specifically certain head and neck surgeries.9 Likewise, topical antibiotics are useful for wound colonization with Pseudomonas, which can remain superficial and slow down healing without progressing to a systemic infection.10 Such cases can be successfully treated or prevented with topical therapies, thereby bypassing the more concerning adverse effects of systemic antibiotics. In particular, systemic fluoroquinolones often are used to treat Pseudomonas and can have many serious adverse effects, including tendon rupture, drug interactions, and arrhythmias.11 Therefore, it is worth implementing topical treatments for wounds colonized with Pseudomonas to spare patients these potential complications.

When a postoperative patient develops a rash at the surgical site, it is critical to differentiate between wound infection and contact allergy, as the treatments for these two conditions may be mutually exclusive and treating the wrong condition may exacerbate the other, such as mistakenly using topical corticosteroids for a wound infection.7 Prompt treatment is necessary for wound infections, as time is limited for patch testing when a rash is already present and the diagnosis is questionable. Allergic contact dermatitis typically erupts 48 to 96 hours following exposure to a contact allergen, often manifesting as intensely pruritic erythematous patches or vesicles.6 Wound infections are characterized by pain and warmth, with erythema and edema present in both conditions. Postoperative infections manifest usually 4 to 7 days following surgery.12 Despite these differences, pruritus and pain are common in the wound healing process; thus, differentiating an infection from ACD on a clinical basis alone is not always possible. Furthermore, presentation of a contact allergy may be delayed beyond the typical 96-hour timeframe if a patient is newly sensitized to an allergen, causing the timeline of rash development to appear similar to that of a wound infection. In such cases, systemic antibiotics often are prescribed empirically; hence, clearer and timelier differentiation between contact allergy and wound infection reduces unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, thereby avoiding systemic adverse effects and promoting responsible antibiotic stewardship.12

The Technique

Since potentially allergenic topical therapies often are indicated in wound management, we propose that patients serve as internal controls to test continuously for contact allergy sensitization. We recommend that patients apply a small amount of the topical agent, product, or dressing to the inner forearm each time they apply it to the wound. If the patient is sensitized to the product initially or becomes sensitized during treatment, evidence of ACD will be visible not only at the site of the wound but also in the area of secondary application. The inner forearm is recommended for convenience and reproducibility, but a patient may choose a different site as long as it remains consistent. Although certain contact allergens rarely may react solely at a site of inflamed skin, our team has quickly identified ACD and avoided misdiagnosis of chronic or postsurgical wound infection using this approach.13 Subsequent patch testing is indicated when a contact allergy is detected.

Practice Implications

Topical therapies including ointments, washes, and dressing components have the potential to cause sensitization and contact allergy. Despite the concern for development of ACD, topical antibiotics play a useful role in cutaneous surgery.7 Synchronous testing for contact allergy when managing wounds with topical therapies could improve diagnostic accuracy when an allergic reaction occurs. This technique provides a means of harnessing the benefits of topical agents while monitoring the risk for ACD in postoperative and chronic wound care settings.

Butler L, Mowad C. Allergic contact dermatitis in dermatologic surgery: review of common allergens. Dermatitis. 2013;24:215-221. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e3182a0d3a9

So SP, Yoon JY, Kim JW. Postoperative contact dermatitis caused by skin adhesives used in orthopedic surgery: incidence, characteristics, and difference from surgical site infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26053. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000026053

Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Ladizinski B, et al. Wound-related allergic/irritant contact dermatitis. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2016;29:278-286. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000482834.94375.1e

Sheth VM, Weitzul S. Postoperative topical antimicrobial use. Dermatitis. 2008;19:181-189.

Kohli N, Nedorost S. Inflamed skin predisposes to sensitization to less potent allergens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:312-317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.010

Cook KA, Kelso JM. Surgery-related contact dermatitis: a review of potential irritants and allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1234-1240. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.001

Kreft B, Wohlrab J. Contact allergies to topical antibiotic applications. Allergol Select. 2022;6:18-26. doi:10.5414/alx02253e

Scherrer MAR, Abreu ÉP, Rocha VB. Neomycin: sources of contact and sensitization evaluation in 1162 patients treated at a tertiary service. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:487-492. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2022.07.008

Ashraf DC, Idowu OO, Wang Q, et al. The role of topical antibiotic prophylaxis in oculofacial plastic surgery: a randomized controlled study. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:1747-1754. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.07.032

Zielin´ska M, Pawłowska A, Orzeł A, et al. Wound microbiota and its impact on wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:17318. doi:10.3390/ijms242417318

Baggio D, Ananda-Rajah MR. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics and adverse events. Aust Prescr. 2021;44:161-164. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2021.035

Ken KM, Johnson MM, Leitenberger JJ, et al. Postoperative infections in dermatologic surgery: the role of wound cultures. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:1294-1299. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000002317

Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

Patients who undergo cutaneous surgery and chronic wound care often are exposed to various topical

Practice Gap

Contact allergies are common in patients with postoperative or chronic wounds. When patch tested, approximately 80% of patients with chronic venous ulcers demonstrated at least 1 positive allergic reaction based on a Canadian study.3 Similarly, postoperative ACD in dermatologic surgery occurs in more than 1.6% of cases in North America and Europe, a rate that is similar to or higher than the rate of postoperative infection, approximately 1% to 2%.4 Postoperative patients and those with chronic wounds have multiple risk factors for ACD. Firstly, applying topical therapies to inflamed or compromised skin increases the risk for contact sensitization.5 Additionally, multiple topical therapies containing known allergenic components may be recommended for wound care, including impregnated or organic dressings, antibiotic ointments, adhesives, antiseptic washes, and topical therapies containing inactive ingredients such as lanolin derivatives.6 Contact with numerous compounds at the same time increases the risk for a contact allergy as well as co-sensitization.7 Similarly, the longer topical agents are applied, the greater the risk for a contact allergy, with sensitization liable to occur at any point during treatment.

Preventive topical antibiotics have garnered a negative reputation among dermatologists, often due to varying data on their efficacy and the overuse of highly allergenic over-the-counter topical antibiotics such as neomycin.8 However, data also have suggested that topical antibiotics can reduce postoperative infections in higher risk surgical cases, specifically certain head and neck surgeries.9 Likewise, topical antibiotics are useful for wound colonization with Pseudomonas, which can remain superficial and slow down healing without progressing to a systemic infection.10 Such cases can be successfully treated or prevented with topical therapies, thereby bypassing the more concerning adverse effects of systemic antibiotics. In particular, systemic fluoroquinolones often are used to treat Pseudomonas and can have many serious adverse effects, including tendon rupture, drug interactions, and arrhythmias.11 Therefore, it is worth implementing topical treatments for wounds colonized with Pseudomonas to spare patients these potential complications.

When a postoperative patient develops a rash at the surgical site, it is critical to differentiate between wound infection and contact allergy, as the treatments for these two conditions may be mutually exclusive and treating the wrong condition may exacerbate the other, such as mistakenly using topical corticosteroids for a wound infection.7 Prompt treatment is necessary for wound infections, as time is limited for patch testing when a rash is already present and the diagnosis is questionable. Allergic contact dermatitis typically erupts 48 to 96 hours following exposure to a contact allergen, often manifesting as intensely pruritic erythematous patches or vesicles.6 Wound infections are characterized by pain and warmth, with erythema and edema present in both conditions. Postoperative infections manifest usually 4 to 7 days following surgery.12 Despite these differences, pruritus and pain are common in the wound healing process; thus, differentiating an infection from ACD on a clinical basis alone is not always possible. Furthermore, presentation of a contact allergy may be delayed beyond the typical 96-hour timeframe if a patient is newly sensitized to an allergen, causing the timeline of rash development to appear similar to that of a wound infection. In such cases, systemic antibiotics often are prescribed empirically; hence, clearer and timelier differentiation between contact allergy and wound infection reduces unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, thereby avoiding systemic adverse effects and promoting responsible antibiotic stewardship.12

The Technique

Since potentially allergenic topical therapies often are indicated in wound management, we propose that patients serve as internal controls to test continuously for contact allergy sensitization. We recommend that patients apply a small amount of the topical agent, product, or dressing to the inner forearm each time they apply it to the wound. If the patient is sensitized to the product initially or becomes sensitized during treatment, evidence of ACD will be visible not only at the site of the wound but also in the area of secondary application. The inner forearm is recommended for convenience and reproducibility, but a patient may choose a different site as long as it remains consistent. Although certain contact allergens rarely may react solely at a site of inflamed skin, our team has quickly identified ACD and avoided misdiagnosis of chronic or postsurgical wound infection using this approach.13 Subsequent patch testing is indicated when a contact allergy is detected.

Practice Implications

Topical therapies including ointments, washes, and dressing components have the potential to cause sensitization and contact allergy. Despite the concern for development of ACD, topical antibiotics play a useful role in cutaneous surgery.7 Synchronous testing for contact allergy when managing wounds with topical therapies could improve diagnostic accuracy when an allergic reaction occurs. This technique provides a means of harnessing the benefits of topical agents while monitoring the risk for ACD in postoperative and chronic wound care settings.

Patients who undergo cutaneous surgery and chronic wound care often are exposed to various topical

Practice Gap

Contact allergies are common in patients with postoperative or chronic wounds. When patch tested, approximately 80% of patients with chronic venous ulcers demonstrated at least 1 positive allergic reaction based on a Canadian study.3 Similarly, postoperative ACD in dermatologic surgery occurs in more than 1.6% of cases in North America and Europe, a rate that is similar to or higher than the rate of postoperative infection, approximately 1% to 2%.4 Postoperative patients and those with chronic wounds have multiple risk factors for ACD. Firstly, applying topical therapies to inflamed or compromised skin increases the risk for contact sensitization.5 Additionally, multiple topical therapies containing known allergenic components may be recommended for wound care, including impregnated or organic dressings, antibiotic ointments, adhesives, antiseptic washes, and topical therapies containing inactive ingredients such as lanolin derivatives.6 Contact with numerous compounds at the same time increases the risk for a contact allergy as well as co-sensitization.7 Similarly, the longer topical agents are applied, the greater the risk for a contact allergy, with sensitization liable to occur at any point during treatment.

Preventive topical antibiotics have garnered a negative reputation among dermatologists, often due to varying data on their efficacy and the overuse of highly allergenic over-the-counter topical antibiotics such as neomycin.8 However, data also have suggested that topical antibiotics can reduce postoperative infections in higher risk surgical cases, specifically certain head and neck surgeries.9 Likewise, topical antibiotics are useful for wound colonization with Pseudomonas, which can remain superficial and slow down healing without progressing to a systemic infection.10 Such cases can be successfully treated or prevented with topical therapies, thereby bypassing the more concerning adverse effects of systemic antibiotics. In particular, systemic fluoroquinolones often are used to treat Pseudomonas and can have many serious adverse effects, including tendon rupture, drug interactions, and arrhythmias.11 Therefore, it is worth implementing topical treatments for wounds colonized with Pseudomonas to spare patients these potential complications.

When a postoperative patient develops a rash at the surgical site, it is critical to differentiate between wound infection and contact allergy, as the treatments for these two conditions may be mutually exclusive and treating the wrong condition may exacerbate the other, such as mistakenly using topical corticosteroids for a wound infection.7 Prompt treatment is necessary for wound infections, as time is limited for patch testing when a rash is already present and the diagnosis is questionable. Allergic contact dermatitis typically erupts 48 to 96 hours following exposure to a contact allergen, often manifesting as intensely pruritic erythematous patches or vesicles.6 Wound infections are characterized by pain and warmth, with erythema and edema present in both conditions. Postoperative infections manifest usually 4 to 7 days following surgery.12 Despite these differences, pruritus and pain are common in the wound healing process; thus, differentiating an infection from ACD on a clinical basis alone is not always possible. Furthermore, presentation of a contact allergy may be delayed beyond the typical 96-hour timeframe if a patient is newly sensitized to an allergen, causing the timeline of rash development to appear similar to that of a wound infection. In such cases, systemic antibiotics often are prescribed empirically; hence, clearer and timelier differentiation between contact allergy and wound infection reduces unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, thereby avoiding systemic adverse effects and promoting responsible antibiotic stewardship.12

The Technique

Since potentially allergenic topical therapies often are indicated in wound management, we propose that patients serve as internal controls to test continuously for contact allergy sensitization. We recommend that patients apply a small amount of the topical agent, product, or dressing to the inner forearm each time they apply it to the wound. If the patient is sensitized to the product initially or becomes sensitized during treatment, evidence of ACD will be visible not only at the site of the wound but also in the area of secondary application. The inner forearm is recommended for convenience and reproducibility, but a patient may choose a different site as long as it remains consistent. Although certain contact allergens rarely may react solely at a site of inflamed skin, our team has quickly identified ACD and avoided misdiagnosis of chronic or postsurgical wound infection using this approach.13 Subsequent patch testing is indicated when a contact allergy is detected.

Practice Implications

Topical therapies including ointments, washes, and dressing components have the potential to cause sensitization and contact allergy. Despite the concern for development of ACD, topical antibiotics play a useful role in cutaneous surgery.7 Synchronous testing for contact allergy when managing wounds with topical therapies could improve diagnostic accuracy when an allergic reaction occurs. This technique provides a means of harnessing the benefits of topical agents while monitoring the risk for ACD in postoperative and chronic wound care settings.

Butler L, Mowad C. Allergic contact dermatitis in dermatologic surgery: review of common allergens. Dermatitis. 2013;24:215-221. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e3182a0d3a9

So SP, Yoon JY, Kim JW. Postoperative contact dermatitis caused by skin adhesives used in orthopedic surgery: incidence, characteristics, and difference from surgical site infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26053. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000026053

Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Ladizinski B, et al. Wound-related allergic/irritant contact dermatitis. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2016;29:278-286. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000482834.94375.1e

Sheth VM, Weitzul S. Postoperative topical antimicrobial use. Dermatitis. 2008;19:181-189.

Kohli N, Nedorost S. Inflamed skin predisposes to sensitization to less potent allergens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:312-317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.010

Cook KA, Kelso JM. Surgery-related contact dermatitis: a review of potential irritants and allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1234-1240. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.001

Kreft B, Wohlrab J. Contact allergies to topical antibiotic applications. Allergol Select. 2022;6:18-26. doi:10.5414/alx02253e

Scherrer MAR, Abreu ÉP, Rocha VB. Neomycin: sources of contact and sensitization evaluation in 1162 patients treated at a tertiary service. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:487-492. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2022.07.008

Ashraf DC, Idowu OO, Wang Q, et al. The role of topical antibiotic prophylaxis in oculofacial plastic surgery: a randomized controlled study. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:1747-1754. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.07.032

Zielin´ska M, Pawłowska A, Orzeł A, et al. Wound microbiota and its impact on wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:17318. doi:10.3390/ijms242417318

Baggio D, Ananda-Rajah MR. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics and adverse events. Aust Prescr. 2021;44:161-164. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2021.035

Ken KM, Johnson MM, Leitenberger JJ, et al. Postoperative infections in dermatologic surgery: the role of wound cultures. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:1294-1299. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000002317

Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

Butler L, Mowad C. Allergic contact dermatitis in dermatologic surgery: review of common allergens. Dermatitis. 2013;24:215-221. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e3182a0d3a9

So SP, Yoon JY, Kim JW. Postoperative contact dermatitis caused by skin adhesives used in orthopedic surgery: incidence, characteristics, and difference from surgical site infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26053. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000026053

Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Ladizinski B, et al. Wound-related allergic/irritant contact dermatitis. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2016;29:278-286. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000482834.94375.1e

Sheth VM, Weitzul S. Postoperative topical antimicrobial use. Dermatitis. 2008;19:181-189.

Kohli N, Nedorost S. Inflamed skin predisposes to sensitization to less potent allergens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:312-317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.010

Cook KA, Kelso JM. Surgery-related contact dermatitis: a review of potential irritants and allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1234-1240. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.001

Kreft B, Wohlrab J. Contact allergies to topical antibiotic applications. Allergol Select. 2022;6:18-26. doi:10.5414/alx02253e

Scherrer MAR, Abreu ÉP, Rocha VB. Neomycin: sources of contact and sensitization evaluation in 1162 patients treated at a tertiary service. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:487-492. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2022.07.008

Ashraf DC, Idowu OO, Wang Q, et al. The role of topical antibiotic prophylaxis in oculofacial plastic surgery: a randomized controlled study. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:1747-1754. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.07.032

Zielin´ska M, Pawłowska A, Orzeł A, et al. Wound microbiota and its impact on wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:17318. doi:10.3390/ijms242417318

Baggio D, Ananda-Rajah MR. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics and adverse events. Aust Prescr. 2021;44:161-164. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2021.035

Ken KM, Johnson MM, Leitenberger JJ, et al. Postoperative infections in dermatologic surgery: the role of wound cultures. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:1294-1299. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000002317

Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365