User login

Plasmapheresis in Refractory Pemphigus Vulgaris: Revisiting an Old Treatment Modality Used in Synchrony With Pulse Cyclophosphamide

To the Editor:

Pemphigus vulgaris is an uncommon autoimmune blistering dermatosis characterized by painful mucocutaneous erosions. It can be a life-threatening condition if left untreated. The autoimmune process is mediated by autoantibodies against the keratinocyte surface antigens desmoglein 1 and 3.1 Therapy is directed at lowering autoantibody levels with systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents. Use of these agents often is limited by collateral adverse effects.2 Refractory disease may occur despite the use of high-dose corticosteroids or a combination of other immunosuppressants. The level of these pathogenic autoantibodies generally parallels the extent of disease activity, and removing them with plasmapheresis followed by immunosuppression should result in therapeutic response.3 We report a case of refractory pemphigus vulgaris that was controlled with plasmapheresis used in synchrony with pulse cyclophosphamide.

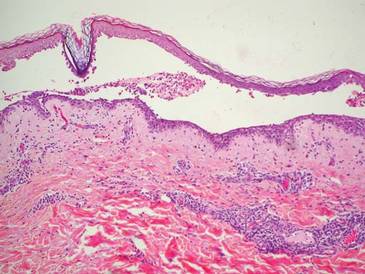

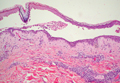

A 48-year-old Chinese man first presented with mucocutaneous erosions 2 years ago, and a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris was confirmed based on typical histologic and immunofluorescence features. Histologic features included suprabasal acantholysis with an intraepidermal blister as well as basal keratinocytes attached to the dermal papillae and present along the entire dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular deposits of IgG and complements in the lower epidermis, and indirect immunofluorescence showed the presence of the pathogenic pemphigus autoantibodies. The patient was initially treated with prednisolone (up to 1 mg/kg daily) and mycophenolate mofetil (1 g twice daily) for 6 months with moderate disease response. Two months later he experienced a disease flare that was triggered by sun exposure and concomitant herpes simplex virus infection. He achieved moderate disease control with acyclovir, 3 days of intravenous immunoglobulin, and combination prednisolone and azathioprine. There was no other relevant medical history. For the last year, the patient received continuous prednisolone (varying doses 0.5–1 mg/kg daily), concomitant azathioprine (up to 3 mg/kg daily), and long-term prophylactic acyclovir, but he continued to have residual crusted erosions over the scalp and face (best score of 25 points based on the autoimmune bullous skin disorder intensity score [ABSIS] ranging from 0–150 points4). He was admitted at the current presentation with another, more severe disease flare with extensive painful erosions over the trunk, arms, legs, face, and scalp (80% body surface area involvement and ABSIS score of 120 points)(Figure 2)4 that occurred after azathioprine was temporarily ceased for 1 week due to transaminitis, and despite a temporary increment in prednisolone dose. There was, however, no significant oral mucosal involvement. The desmoglein 1 and 3 antibody levels were elevated at more than 300 U/mL and 186 U/mL, respectively (>20 U/mL indicates positivity). A 3-day course of pulse intravenous methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg) failed to achieve clinical improvement or reduction of antibody titers. The use of various immunosuppressive agents was limited by persistent transaminitis and transient leukopenia.

|

Because of remarkable morbidity, the patient underwent interim plasmapheresis for rapid disease control. Plasmapheresis was carried out through a pheresible central venous catheter. One plasma volume exchange was done each session, which was 5 L for the patient’s body weight and hematocrit. Equal volume of colloid comprising 2.5 L of fresh frozen plasma and 2.5 L of 5% albumin was used for replacement. Plasma exchange was performed with a cell separator by discontinuous flow centrifugation with 4% acid citrate dextrose as an anticoagulant. For each session of plasmapheresis, 16 cycles of exchange (each processing approximately 300 mL of blood) was carried out, the entire process lasting for 4 hours. The coagulation and biochemical profile was checked after each session of plasmapheresis and corrected when necessary. The patient underwent 9 sessions of plasmapheresis over a 3-week period, synchronized with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide (15 mg/kg) immediately after completion of the plasmapheresis sessions, resulting in a remarkable decrease in pathogenic antibody titers to near undetectable levels and clinical improvement (Figure 3). The extensive erosions gradually healed with good reepithelialization, and there was a notable reduction in the ABSIS score to 12 points. He received 3 more monthly treatments with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide (15 mg/kg) and is currently maintained on oral cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg daily) and low-dose prednisolone (0.3 mg/kg daily). There was no subsequent disease relapse at 6-month follow-up, with the ABSIS score maintained at 5 points, and no increase in pathogenic autoantibody titers. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Patients with severe disease or refractory cases of pemphigus vulgaris that have been maintained on unacceptably high doses of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants that cannot be tapered without a disease flare may develop remarkable adverse effects, both from medications and from long-term immunosuppression.2 Our case illustrates the short-term benefit of plasmapheresis combined with immunosuppressants resulting in rapid disease control.

Plasmapheresis involves the selective removal of pathogenic materials from the circulation to achieve therapeutic effect, followed by appropriate replacement fluids. Treating pemphigus vulgaris with plasmapheresis was introduced in 1978 based on the rationale of removing pathogenic autoantibodies from the circulation.3,5 Using desmoglein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, it has been shown that one centrifugal plasmapheresis procedure eliminates approximately 15% of the IgG autoantibodies from the whole body.6 An average of 5 plasmapheresis sessions on alternate days usually is required to deplete the levels of pathogenic autoantibodies to near undetectable levels.7 Our case required 9 plasmapheresis sessions over 3 weeks to achieve good therapeutic response.

It seems that using plasmapheresis to treat pemphigus vulgaris has fallen out of favor due to its inability to prevent the antibody rebound occurring during weeks 1 and 2 posttreatment. Because of a feedback mechanism, a massive antibody depletion by plasmapheresis triggers a rebound synthesis of more autoantibodies by pathogenic B cells to titers comparable to or higher than those before plasmapheresis.8 The use of plasmapheresis should be supported by immunosuppressive therapy to prevent antibody feedback rebound. Due to the advent of available immunosuppressive agents in recent years, there is a resurgence in the successful use of this old treatment modality combined with immunosuppressive therapy in managing refractory pemphigus vulgaris.7,8 At present there is no clear data to support the use of one immunosuppressant versus another, but our case supports the use of pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide, as documented in other reports.7,9 The success of immunosuppressive agents at reducing antibody levels depends on the timing (immediately after plasmapheresis) as well as individual responsiveness to the immunosuppressant.7

Our armamentarium of therapies for refractory pemphigus vulgaris continues to evolve. A more selective method of removing antibodies by extracorporeal immunoadsorption has the benefit of higher removal rates and reduced inadvertent loss of other plasma components.10 The combination of protein A immunoadsorption with rituximab, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that induces B-cell depletion, also has been shown to induce rapid and durable remission in refractory cases.11

Our case shows that plasmapheresis can be a useful alternative or adjunctive intervention in pemphigus vulgaris that is not responding to conventional therapy or in cases when steroids or immunosuppressants are contraindicated. There is a definite role for such therapeutic plasma exchanges in the rapid control of potentially life-threatening disease. Its benefits are optimized when used in synchrony with immunosuppressants immediately following plasmapheresis to prevent rebound effect of antibody depletion.

1. Udey MC, Stanley JR. Pemphigus–disease of antidesmosomal autoimmunity. JAMA. 1999;282:572-576.

2. Huilgol SC, Black MM. Management of the immunobullous disorders. II. pemphigus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:283-293.

3. Cotterill JA, Barker DJ, Millard LG. Plasma exchange in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:243.

4. Pfutze M, Niedermeier A, Hertl M, et al. Introducing a novel Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score (ABSIS) in pemphigus [published online ahead of print February 27, 2007]. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:4-11.

5. Ruocco V, Rossi A, Argenziano G, et al. Pathogenicity of the intercellular antibodies of pemphigus their periodic removal from the circulation by plasmapheresis. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:237-241.

6. Nagasaka T, Fujii Y, Ishida A, et al. Evaluating efficacy of plasmapheresis for patients with pemphigus using desmoglein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [published online ahead of print January 30, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:685-690.

7. Turner MS, Sutton D, Sauder DN. The use of plasmapheresis and immunosuppression in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:1058-1064.

8. Roujeau JC, Andre C, Joneau Fabre M, et al. Plasma exchange in pemphigus. uncontrolled study of ten patients. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:215-221.

9. Euler HH, Löffler H, Christophers E. Synchronization of plasmapheresis and pulse cyclophosphamide therapy in pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1205-1210.

10. Lüftl M, Stauber A, Mainka A, et al. Successful removal of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus by immunoadsorption with a tryptophan-linked polyvinylalcohol adsorber. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:598-605.

11. Shimanovich I, Nitschke M, Rose C, et al. Treatment of severe pemphigus with protein A immunoadsorption, rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulins. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:382-388.

To the Editor:

Pemphigus vulgaris is an uncommon autoimmune blistering dermatosis characterized by painful mucocutaneous erosions. It can be a life-threatening condition if left untreated. The autoimmune process is mediated by autoantibodies against the keratinocyte surface antigens desmoglein 1 and 3.1 Therapy is directed at lowering autoantibody levels with systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents. Use of these agents often is limited by collateral adverse effects.2 Refractory disease may occur despite the use of high-dose corticosteroids or a combination of other immunosuppressants. The level of these pathogenic autoantibodies generally parallels the extent of disease activity, and removing them with plasmapheresis followed by immunosuppression should result in therapeutic response.3 We report a case of refractory pemphigus vulgaris that was controlled with plasmapheresis used in synchrony with pulse cyclophosphamide.

A 48-year-old Chinese man first presented with mucocutaneous erosions 2 years ago, and a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris was confirmed based on typical histologic and immunofluorescence features. Histologic features included suprabasal acantholysis with an intraepidermal blister as well as basal keratinocytes attached to the dermal papillae and present along the entire dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular deposits of IgG and complements in the lower epidermis, and indirect immunofluorescence showed the presence of the pathogenic pemphigus autoantibodies. The patient was initially treated with prednisolone (up to 1 mg/kg daily) and mycophenolate mofetil (1 g twice daily) for 6 months with moderate disease response. Two months later he experienced a disease flare that was triggered by sun exposure and concomitant herpes simplex virus infection. He achieved moderate disease control with acyclovir, 3 days of intravenous immunoglobulin, and combination prednisolone and azathioprine. There was no other relevant medical history. For the last year, the patient received continuous prednisolone (varying doses 0.5–1 mg/kg daily), concomitant azathioprine (up to 3 mg/kg daily), and long-term prophylactic acyclovir, but he continued to have residual crusted erosions over the scalp and face (best score of 25 points based on the autoimmune bullous skin disorder intensity score [ABSIS] ranging from 0–150 points4). He was admitted at the current presentation with another, more severe disease flare with extensive painful erosions over the trunk, arms, legs, face, and scalp (80% body surface area involvement and ABSIS score of 120 points)(Figure 2)4 that occurred after azathioprine was temporarily ceased for 1 week due to transaminitis, and despite a temporary increment in prednisolone dose. There was, however, no significant oral mucosal involvement. The desmoglein 1 and 3 antibody levels were elevated at more than 300 U/mL and 186 U/mL, respectively (>20 U/mL indicates positivity). A 3-day course of pulse intravenous methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg) failed to achieve clinical improvement or reduction of antibody titers. The use of various immunosuppressive agents was limited by persistent transaminitis and transient leukopenia.

|

Because of remarkable morbidity, the patient underwent interim plasmapheresis for rapid disease control. Plasmapheresis was carried out through a pheresible central venous catheter. One plasma volume exchange was done each session, which was 5 L for the patient’s body weight and hematocrit. Equal volume of colloid comprising 2.5 L of fresh frozen plasma and 2.5 L of 5% albumin was used for replacement. Plasma exchange was performed with a cell separator by discontinuous flow centrifugation with 4% acid citrate dextrose as an anticoagulant. For each session of plasmapheresis, 16 cycles of exchange (each processing approximately 300 mL of blood) was carried out, the entire process lasting for 4 hours. The coagulation and biochemical profile was checked after each session of plasmapheresis and corrected when necessary. The patient underwent 9 sessions of plasmapheresis over a 3-week period, synchronized with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide (15 mg/kg) immediately after completion of the plasmapheresis sessions, resulting in a remarkable decrease in pathogenic antibody titers to near undetectable levels and clinical improvement (Figure 3). The extensive erosions gradually healed with good reepithelialization, and there was a notable reduction in the ABSIS score to 12 points. He received 3 more monthly treatments with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide (15 mg/kg) and is currently maintained on oral cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg daily) and low-dose prednisolone (0.3 mg/kg daily). There was no subsequent disease relapse at 6-month follow-up, with the ABSIS score maintained at 5 points, and no increase in pathogenic autoantibody titers. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Patients with severe disease or refractory cases of pemphigus vulgaris that have been maintained on unacceptably high doses of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants that cannot be tapered without a disease flare may develop remarkable adverse effects, both from medications and from long-term immunosuppression.2 Our case illustrates the short-term benefit of plasmapheresis combined with immunosuppressants resulting in rapid disease control.

Plasmapheresis involves the selective removal of pathogenic materials from the circulation to achieve therapeutic effect, followed by appropriate replacement fluids. Treating pemphigus vulgaris with plasmapheresis was introduced in 1978 based on the rationale of removing pathogenic autoantibodies from the circulation.3,5 Using desmoglein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, it has been shown that one centrifugal plasmapheresis procedure eliminates approximately 15% of the IgG autoantibodies from the whole body.6 An average of 5 plasmapheresis sessions on alternate days usually is required to deplete the levels of pathogenic autoantibodies to near undetectable levels.7 Our case required 9 plasmapheresis sessions over 3 weeks to achieve good therapeutic response.

It seems that using plasmapheresis to treat pemphigus vulgaris has fallen out of favor due to its inability to prevent the antibody rebound occurring during weeks 1 and 2 posttreatment. Because of a feedback mechanism, a massive antibody depletion by plasmapheresis triggers a rebound synthesis of more autoantibodies by pathogenic B cells to titers comparable to or higher than those before plasmapheresis.8 The use of plasmapheresis should be supported by immunosuppressive therapy to prevent antibody feedback rebound. Due to the advent of available immunosuppressive agents in recent years, there is a resurgence in the successful use of this old treatment modality combined with immunosuppressive therapy in managing refractory pemphigus vulgaris.7,8 At present there is no clear data to support the use of one immunosuppressant versus another, but our case supports the use of pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide, as documented in other reports.7,9 The success of immunosuppressive agents at reducing antibody levels depends on the timing (immediately after plasmapheresis) as well as individual responsiveness to the immunosuppressant.7

Our armamentarium of therapies for refractory pemphigus vulgaris continues to evolve. A more selective method of removing antibodies by extracorporeal immunoadsorption has the benefit of higher removal rates and reduced inadvertent loss of other plasma components.10 The combination of protein A immunoadsorption with rituximab, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that induces B-cell depletion, also has been shown to induce rapid and durable remission in refractory cases.11

Our case shows that plasmapheresis can be a useful alternative or adjunctive intervention in pemphigus vulgaris that is not responding to conventional therapy or in cases when steroids or immunosuppressants are contraindicated. There is a definite role for such therapeutic plasma exchanges in the rapid control of potentially life-threatening disease. Its benefits are optimized when used in synchrony with immunosuppressants immediately following plasmapheresis to prevent rebound effect of antibody depletion.

To the Editor:

Pemphigus vulgaris is an uncommon autoimmune blistering dermatosis characterized by painful mucocutaneous erosions. It can be a life-threatening condition if left untreated. The autoimmune process is mediated by autoantibodies against the keratinocyte surface antigens desmoglein 1 and 3.1 Therapy is directed at lowering autoantibody levels with systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents. Use of these agents often is limited by collateral adverse effects.2 Refractory disease may occur despite the use of high-dose corticosteroids or a combination of other immunosuppressants. The level of these pathogenic autoantibodies generally parallels the extent of disease activity, and removing them with plasmapheresis followed by immunosuppression should result in therapeutic response.3 We report a case of refractory pemphigus vulgaris that was controlled with plasmapheresis used in synchrony with pulse cyclophosphamide.

A 48-year-old Chinese man first presented with mucocutaneous erosions 2 years ago, and a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris was confirmed based on typical histologic and immunofluorescence features. Histologic features included suprabasal acantholysis with an intraepidermal blister as well as basal keratinocytes attached to the dermal papillae and present along the entire dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular deposits of IgG and complements in the lower epidermis, and indirect immunofluorescence showed the presence of the pathogenic pemphigus autoantibodies. The patient was initially treated with prednisolone (up to 1 mg/kg daily) and mycophenolate mofetil (1 g twice daily) for 6 months with moderate disease response. Two months later he experienced a disease flare that was triggered by sun exposure and concomitant herpes simplex virus infection. He achieved moderate disease control with acyclovir, 3 days of intravenous immunoglobulin, and combination prednisolone and azathioprine. There was no other relevant medical history. For the last year, the patient received continuous prednisolone (varying doses 0.5–1 mg/kg daily), concomitant azathioprine (up to 3 mg/kg daily), and long-term prophylactic acyclovir, but he continued to have residual crusted erosions over the scalp and face (best score of 25 points based on the autoimmune bullous skin disorder intensity score [ABSIS] ranging from 0–150 points4). He was admitted at the current presentation with another, more severe disease flare with extensive painful erosions over the trunk, arms, legs, face, and scalp (80% body surface area involvement and ABSIS score of 120 points)(Figure 2)4 that occurred after azathioprine was temporarily ceased for 1 week due to transaminitis, and despite a temporary increment in prednisolone dose. There was, however, no significant oral mucosal involvement. The desmoglein 1 and 3 antibody levels were elevated at more than 300 U/mL and 186 U/mL, respectively (>20 U/mL indicates positivity). A 3-day course of pulse intravenous methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg) failed to achieve clinical improvement or reduction of antibody titers. The use of various immunosuppressive agents was limited by persistent transaminitis and transient leukopenia.

|

Because of remarkable morbidity, the patient underwent interim plasmapheresis for rapid disease control. Plasmapheresis was carried out through a pheresible central venous catheter. One plasma volume exchange was done each session, which was 5 L for the patient’s body weight and hematocrit. Equal volume of colloid comprising 2.5 L of fresh frozen plasma and 2.5 L of 5% albumin was used for replacement. Plasma exchange was performed with a cell separator by discontinuous flow centrifugation with 4% acid citrate dextrose as an anticoagulant. For each session of plasmapheresis, 16 cycles of exchange (each processing approximately 300 mL of blood) was carried out, the entire process lasting for 4 hours. The coagulation and biochemical profile was checked after each session of plasmapheresis and corrected when necessary. The patient underwent 9 sessions of plasmapheresis over a 3-week period, synchronized with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide (15 mg/kg) immediately after completion of the plasmapheresis sessions, resulting in a remarkable decrease in pathogenic antibody titers to near undetectable levels and clinical improvement (Figure 3). The extensive erosions gradually healed with good reepithelialization, and there was a notable reduction in the ABSIS score to 12 points. He received 3 more monthly treatments with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide (15 mg/kg) and is currently maintained on oral cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg daily) and low-dose prednisolone (0.3 mg/kg daily). There was no subsequent disease relapse at 6-month follow-up, with the ABSIS score maintained at 5 points, and no increase in pathogenic autoantibody titers. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Patients with severe disease or refractory cases of pemphigus vulgaris that have been maintained on unacceptably high doses of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants that cannot be tapered without a disease flare may develop remarkable adverse effects, both from medications and from long-term immunosuppression.2 Our case illustrates the short-term benefit of plasmapheresis combined with immunosuppressants resulting in rapid disease control.

Plasmapheresis involves the selective removal of pathogenic materials from the circulation to achieve therapeutic effect, followed by appropriate replacement fluids. Treating pemphigus vulgaris with plasmapheresis was introduced in 1978 based on the rationale of removing pathogenic autoantibodies from the circulation.3,5 Using desmoglein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, it has been shown that one centrifugal plasmapheresis procedure eliminates approximately 15% of the IgG autoantibodies from the whole body.6 An average of 5 plasmapheresis sessions on alternate days usually is required to deplete the levels of pathogenic autoantibodies to near undetectable levels.7 Our case required 9 plasmapheresis sessions over 3 weeks to achieve good therapeutic response.

It seems that using plasmapheresis to treat pemphigus vulgaris has fallen out of favor due to its inability to prevent the antibody rebound occurring during weeks 1 and 2 posttreatment. Because of a feedback mechanism, a massive antibody depletion by plasmapheresis triggers a rebound synthesis of more autoantibodies by pathogenic B cells to titers comparable to or higher than those before plasmapheresis.8 The use of plasmapheresis should be supported by immunosuppressive therapy to prevent antibody feedback rebound. Due to the advent of available immunosuppressive agents in recent years, there is a resurgence in the successful use of this old treatment modality combined with immunosuppressive therapy in managing refractory pemphigus vulgaris.7,8 At present there is no clear data to support the use of one immunosuppressant versus another, but our case supports the use of pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide, as documented in other reports.7,9 The success of immunosuppressive agents at reducing antibody levels depends on the timing (immediately after plasmapheresis) as well as individual responsiveness to the immunosuppressant.7

Our armamentarium of therapies for refractory pemphigus vulgaris continues to evolve. A more selective method of removing antibodies by extracorporeal immunoadsorption has the benefit of higher removal rates and reduced inadvertent loss of other plasma components.10 The combination of protein A immunoadsorption with rituximab, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that induces B-cell depletion, also has been shown to induce rapid and durable remission in refractory cases.11

Our case shows that plasmapheresis can be a useful alternative or adjunctive intervention in pemphigus vulgaris that is not responding to conventional therapy or in cases when steroids or immunosuppressants are contraindicated. There is a definite role for such therapeutic plasma exchanges in the rapid control of potentially life-threatening disease. Its benefits are optimized when used in synchrony with immunosuppressants immediately following plasmapheresis to prevent rebound effect of antibody depletion.

1. Udey MC, Stanley JR. Pemphigus–disease of antidesmosomal autoimmunity. JAMA. 1999;282:572-576.

2. Huilgol SC, Black MM. Management of the immunobullous disorders. II. pemphigus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:283-293.

3. Cotterill JA, Barker DJ, Millard LG. Plasma exchange in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:243.

4. Pfutze M, Niedermeier A, Hertl M, et al. Introducing a novel Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score (ABSIS) in pemphigus [published online ahead of print February 27, 2007]. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:4-11.

5. Ruocco V, Rossi A, Argenziano G, et al. Pathogenicity of the intercellular antibodies of pemphigus their periodic removal from the circulation by plasmapheresis. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:237-241.

6. Nagasaka T, Fujii Y, Ishida A, et al. Evaluating efficacy of plasmapheresis for patients with pemphigus using desmoglein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [published online ahead of print January 30, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:685-690.

7. Turner MS, Sutton D, Sauder DN. The use of plasmapheresis and immunosuppression in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:1058-1064.

8. Roujeau JC, Andre C, Joneau Fabre M, et al. Plasma exchange in pemphigus. uncontrolled study of ten patients. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:215-221.

9. Euler HH, Löffler H, Christophers E. Synchronization of plasmapheresis and pulse cyclophosphamide therapy in pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1205-1210.

10. Lüftl M, Stauber A, Mainka A, et al. Successful removal of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus by immunoadsorption with a tryptophan-linked polyvinylalcohol adsorber. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:598-605.

11. Shimanovich I, Nitschke M, Rose C, et al. Treatment of severe pemphigus with protein A immunoadsorption, rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulins. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:382-388.

1. Udey MC, Stanley JR. Pemphigus–disease of antidesmosomal autoimmunity. JAMA. 1999;282:572-576.

2. Huilgol SC, Black MM. Management of the immunobullous disorders. II. pemphigus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:283-293.

3. Cotterill JA, Barker DJ, Millard LG. Plasma exchange in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:243.

4. Pfutze M, Niedermeier A, Hertl M, et al. Introducing a novel Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score (ABSIS) in pemphigus [published online ahead of print February 27, 2007]. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:4-11.

5. Ruocco V, Rossi A, Argenziano G, et al. Pathogenicity of the intercellular antibodies of pemphigus their periodic removal from the circulation by plasmapheresis. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:237-241.

6. Nagasaka T, Fujii Y, Ishida A, et al. Evaluating efficacy of plasmapheresis for patients with pemphigus using desmoglein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [published online ahead of print January 30, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:685-690.

7. Turner MS, Sutton D, Sauder DN. The use of plasmapheresis and immunosuppression in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:1058-1064.

8. Roujeau JC, Andre C, Joneau Fabre M, et al. Plasma exchange in pemphigus. uncontrolled study of ten patients. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:215-221.

9. Euler HH, Löffler H, Christophers E. Synchronization of plasmapheresis and pulse cyclophosphamide therapy in pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1205-1210.

10. Lüftl M, Stauber A, Mainka A, et al. Successful removal of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus by immunoadsorption with a tryptophan-linked polyvinylalcohol adsorber. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:598-605.

11. Shimanovich I, Nitschke M, Rose C, et al. Treatment of severe pemphigus with protein A immunoadsorption, rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulins. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:382-388.

Late-Onset Acrokeratosis Paraneoplastica of Bazex Associated With Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Colon

To the Editor:

Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (AP) of Bazex is a rare but distinctive acral psoriasiform dermatosis associated with internal malignancy, usually squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), of the upper aerodigestive tract.1,2 Recognizing this paraneoplastic condition is paramount because cutaneous findings often precede the onset of symptoms associated with an occult malignancy.3

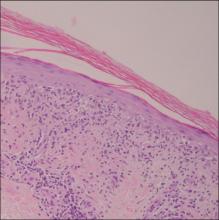

A 76-year-old woman with adenocarcinoma of the transverse colon of 3 years’ duration was referred to the dermatology department. She had a hemicolectomy and was doing well until tumor recurrence with peritoneal metastasis was detected following an exploratory laparotomy 1 year prior to presentation to us. She underwent a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Palliative chemotherapy was initiated, and she completed 5 cycles of capecitabine and oxaliplatin. Long-term medications for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia included glibenclamide, nifedipine, hydrochlorothiazide, and losartan. The patient had a progressive pruritic rash of 6 months’ duration that started on the hands and forearms and spread to involve the feet and lower limbs as well as the ears and face. She also experienced progressive thickening of the palms and soles. She had been treated with topical steroids and emollients with no improvement. Clinical examination revealed erythematous scaly patches on all of her limbs, especially on the elbows and knees, and on the ear helices and nose. There also was notable palmoplantar keratoderma with central sparing (Figure 1), onycholysis, and subungual hyperkeratosis. A skin biopsy of the forearm was performed, and histology revealed orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis and basal vacuolar alteration, and superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with melanophages (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence studies and fungal cultures were negative. The cutaneous features of a treatment-resistant acral dermatosis supported the clinical diagnosis of AP, especially in the setting of an internal malignancy. The patient was started on palliative radiotherapy with no notable resolution of the cutaneous lesions. She was lost to follow-up.

First described by Bazex et al1 in 1965, AP is an uncommon but well-recognized paraneoplastic dermatosis associated with an underlying neoplasm. Fewer than 160 cases have been reported, and the majority of cases have been men older than 40 years. The most commonly associated malignancy was SCC (at least 50% of reported cases) involving mainly the oropharynx and larynx, with lung and esophageal SCC also described.2-4 Only a few cases of adenocarcinoma-associated AP have been described, such as adenocarcinoma of the lung, prostate, and stomach.3-5 In a reported case of AP associated with early colon adenocarcinoma, the patient had remarkable cutaneous resolution following successful tumor resection.6 Other reported rare hematologic associations included Hodgkin disease, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.3-5 Karabulut et al4 described a case associated with cholangiocarcinoma and studied the primary sites of malignancies in another 133 patients with AP (118 patients with documented cell type): oropharynx and larynx in 55 (41%); lung in 23 (17%); unknown location in 20 (15%); esophagus in 14 (11%); prostate in 3 (2%); stomach in 3 (2%); and isolated cases involving the liver, thymus, uterus, vulva, breast, urinary bladder, lymph nodes, and bone marrow.

A review of 113 cases of AP showed that only 15% developed cutaneous lesions after the malignancy had been discovered; in the majority of cases (67%), cutaneous lesions were present for an average of 1 year preceding the diagnosis of malignancy.3 In our patient, the late-onset cutaneous involvement corresponded to the progression of the underlying colon adenocarcinoma. In the absence of initial cutaneous involvement or when successful treatment of a tumor results in cutaneous resolution, subsequent emergence of cutaneous lesions of AP signifies tumor progression. The evolution of cutaneous features in AP was well described by Bazex et al.1 Stage 1 of the disease shows initial erythema and psoriasiform scaling of the fingers and toes, spreading to the nose and ear helices (hence acrokeratosis); the tumor frequently remains asymptomatic or undetected. Stage 2 shows palmoplantar keratoderma with central sparing and more extensive facial lesions; progression to stage 3 occurs if the tumor remains undetected or untreated, with further spread of psoriasiform lesions to the elbows, knees, trunk, and scalp.1 Nail involvement occurs in nearly 75% of cases5; typical changes include subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, longitudinal streaks, yellow pigmentation, and rarely onychomadesis. A high index of suspicion of AP is paramount when evaluating any recalcitrant acral dermatosis that fails to respond to appropriate therapy, especially in the presence of constitutional symptoms, typical bulbous enlargement of distal phalanges, or isolated involvement of helices. These findings should prompt physicians to perform an extensive search for an underlying malignancy with complete physical examination, particularly of the head and neck region, with appropriate endoscopic assessment and imaging studies.

A myriad of nonspecific histologic features of AP commonly reported include hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.7 Less common features include dyskeratotic keratinocytes, vacuolar degeneration, bandlike infiltrate, and melanin incontinence.7 The pathogenesis of AP remains elusive. A postulated immunologic mechanism is based on reports of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) and complement (C3) deposition along the basement membrane zone.8 Association with autoimmune disorders such as alopecia areata and vitiligo also has been reported.9 Another possible mechanism is cross-reactivity between antigens found in the tumor and skin, resulting in a T-cell–mediated immune response to tumorlike antigens in the epidermis, or secretion of tumor-originating growth factors responsible for the hyperkeratotic skin changes, such as epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor a, or insulinlike growth factor 1.3,7,10,11

Spontaneous remission of cutaneous lesions in untreated underlying malignancy is rare. Isolated reports of treatment using topical and systemic steroids, salicylic acid, topical vitamin D analogues, etretinate, and psoralen plus UVA showed minimal improvement.5,7 The mainstay in attaining cutaneous resolution is to detect and eradicate the underlying neoplasm with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, or combination therapy.

Our case is noteworthy because of the patient’s gender (female), underlying malignancy (adenocarcinoma of the colon), and late onset of cutaneous involvement, which are all uncommon associations related to paraneoplastic syndrome. The clinical features of AP should be recognized early to facilitate an extensive search for an occult malignancy, and late-onset cutaneous involvement also should be recognized as a marker of tumor relapse or progression.

1. Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Late symptomatic hepatic porphyria developing to the picture of lipoidoproteinsosis [in French]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

2. Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex’s syndrome. paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

3. Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

4. Karabulut AA, Sahin S, Sahin M, et al. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis of Bazex (Bazex’s syndrome): report of a female case associated with cholangiocarcinoma and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2006;33:850-854.

5. Valdivielso M, Longo I, Suárez R. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica: Bazex syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:340-344.

6. Hsu YS, Lien GS, Lai HH, et al. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) with adenocarcinoma of the colon: report of a case and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:460-464.

7. Bolognia JL, Brewer YP, Cooper DL. Bazex syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica). an analytic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:269-280.

8. Mutasim DF, Meiri G. Bazex syndrome mimicking a primary autoimmune bullous disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5, pt 2):822-825.

9. Hara M, Hunayama M, Aiba S, et al. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) associated with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the lower leg, vitiligo and alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:121-124.

10. Stone SP, Buescher LS. Life-threatening paraneoplastic cutaneous syndromes. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:301-306.

11. Politi Y, Ophir J, Brenner S. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:161-170.

To the Editor:

Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (AP) of Bazex is a rare but distinctive acral psoriasiform dermatosis associated with internal malignancy, usually squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), of the upper aerodigestive tract.1,2 Recognizing this paraneoplastic condition is paramount because cutaneous findings often precede the onset of symptoms associated with an occult malignancy.3

A 76-year-old woman with adenocarcinoma of the transverse colon of 3 years’ duration was referred to the dermatology department. She had a hemicolectomy and was doing well until tumor recurrence with peritoneal metastasis was detected following an exploratory laparotomy 1 year prior to presentation to us. She underwent a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Palliative chemotherapy was initiated, and she completed 5 cycles of capecitabine and oxaliplatin. Long-term medications for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia included glibenclamide, nifedipine, hydrochlorothiazide, and losartan. The patient had a progressive pruritic rash of 6 months’ duration that started on the hands and forearms and spread to involve the feet and lower limbs as well as the ears and face. She also experienced progressive thickening of the palms and soles. She had been treated with topical steroids and emollients with no improvement. Clinical examination revealed erythematous scaly patches on all of her limbs, especially on the elbows and knees, and on the ear helices and nose. There also was notable palmoplantar keratoderma with central sparing (Figure 1), onycholysis, and subungual hyperkeratosis. A skin biopsy of the forearm was performed, and histology revealed orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis and basal vacuolar alteration, and superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with melanophages (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence studies and fungal cultures were negative. The cutaneous features of a treatment-resistant acral dermatosis supported the clinical diagnosis of AP, especially in the setting of an internal malignancy. The patient was started on palliative radiotherapy with no notable resolution of the cutaneous lesions. She was lost to follow-up.

First described by Bazex et al1 in 1965, AP is an uncommon but well-recognized paraneoplastic dermatosis associated with an underlying neoplasm. Fewer than 160 cases have been reported, and the majority of cases have been men older than 40 years. The most commonly associated malignancy was SCC (at least 50% of reported cases) involving mainly the oropharynx and larynx, with lung and esophageal SCC also described.2-4 Only a few cases of adenocarcinoma-associated AP have been described, such as adenocarcinoma of the lung, prostate, and stomach.3-5 In a reported case of AP associated with early colon adenocarcinoma, the patient had remarkable cutaneous resolution following successful tumor resection.6 Other reported rare hematologic associations included Hodgkin disease, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.3-5 Karabulut et al4 described a case associated with cholangiocarcinoma and studied the primary sites of malignancies in another 133 patients with AP (118 patients with documented cell type): oropharynx and larynx in 55 (41%); lung in 23 (17%); unknown location in 20 (15%); esophagus in 14 (11%); prostate in 3 (2%); stomach in 3 (2%); and isolated cases involving the liver, thymus, uterus, vulva, breast, urinary bladder, lymph nodes, and bone marrow.

A review of 113 cases of AP showed that only 15% developed cutaneous lesions after the malignancy had been discovered; in the majority of cases (67%), cutaneous lesions were present for an average of 1 year preceding the diagnosis of malignancy.3 In our patient, the late-onset cutaneous involvement corresponded to the progression of the underlying colon adenocarcinoma. In the absence of initial cutaneous involvement or when successful treatment of a tumor results in cutaneous resolution, subsequent emergence of cutaneous lesions of AP signifies tumor progression. The evolution of cutaneous features in AP was well described by Bazex et al.1 Stage 1 of the disease shows initial erythema and psoriasiform scaling of the fingers and toes, spreading to the nose and ear helices (hence acrokeratosis); the tumor frequently remains asymptomatic or undetected. Stage 2 shows palmoplantar keratoderma with central sparing and more extensive facial lesions; progression to stage 3 occurs if the tumor remains undetected or untreated, with further spread of psoriasiform lesions to the elbows, knees, trunk, and scalp.1 Nail involvement occurs in nearly 75% of cases5; typical changes include subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, longitudinal streaks, yellow pigmentation, and rarely onychomadesis. A high index of suspicion of AP is paramount when evaluating any recalcitrant acral dermatosis that fails to respond to appropriate therapy, especially in the presence of constitutional symptoms, typical bulbous enlargement of distal phalanges, or isolated involvement of helices. These findings should prompt physicians to perform an extensive search for an underlying malignancy with complete physical examination, particularly of the head and neck region, with appropriate endoscopic assessment and imaging studies.

A myriad of nonspecific histologic features of AP commonly reported include hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.7 Less common features include dyskeratotic keratinocytes, vacuolar degeneration, bandlike infiltrate, and melanin incontinence.7 The pathogenesis of AP remains elusive. A postulated immunologic mechanism is based on reports of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) and complement (C3) deposition along the basement membrane zone.8 Association with autoimmune disorders such as alopecia areata and vitiligo also has been reported.9 Another possible mechanism is cross-reactivity between antigens found in the tumor and skin, resulting in a T-cell–mediated immune response to tumorlike antigens in the epidermis, or secretion of tumor-originating growth factors responsible for the hyperkeratotic skin changes, such as epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor a, or insulinlike growth factor 1.3,7,10,11

Spontaneous remission of cutaneous lesions in untreated underlying malignancy is rare. Isolated reports of treatment using topical and systemic steroids, salicylic acid, topical vitamin D analogues, etretinate, and psoralen plus UVA showed minimal improvement.5,7 The mainstay in attaining cutaneous resolution is to detect and eradicate the underlying neoplasm with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, or combination therapy.

Our case is noteworthy because of the patient’s gender (female), underlying malignancy (adenocarcinoma of the colon), and late onset of cutaneous involvement, which are all uncommon associations related to paraneoplastic syndrome. The clinical features of AP should be recognized early to facilitate an extensive search for an occult malignancy, and late-onset cutaneous involvement also should be recognized as a marker of tumor relapse or progression.

To the Editor:

Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (AP) of Bazex is a rare but distinctive acral psoriasiform dermatosis associated with internal malignancy, usually squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), of the upper aerodigestive tract.1,2 Recognizing this paraneoplastic condition is paramount because cutaneous findings often precede the onset of symptoms associated with an occult malignancy.3

A 76-year-old woman with adenocarcinoma of the transverse colon of 3 years’ duration was referred to the dermatology department. She had a hemicolectomy and was doing well until tumor recurrence with peritoneal metastasis was detected following an exploratory laparotomy 1 year prior to presentation to us. She underwent a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Palliative chemotherapy was initiated, and she completed 5 cycles of capecitabine and oxaliplatin. Long-term medications for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia included glibenclamide, nifedipine, hydrochlorothiazide, and losartan. The patient had a progressive pruritic rash of 6 months’ duration that started on the hands and forearms and spread to involve the feet and lower limbs as well as the ears and face. She also experienced progressive thickening of the palms and soles. She had been treated with topical steroids and emollients with no improvement. Clinical examination revealed erythematous scaly patches on all of her limbs, especially on the elbows and knees, and on the ear helices and nose. There also was notable palmoplantar keratoderma with central sparing (Figure 1), onycholysis, and subungual hyperkeratosis. A skin biopsy of the forearm was performed, and histology revealed orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis and basal vacuolar alteration, and superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with melanophages (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence studies and fungal cultures were negative. The cutaneous features of a treatment-resistant acral dermatosis supported the clinical diagnosis of AP, especially in the setting of an internal malignancy. The patient was started on palliative radiotherapy with no notable resolution of the cutaneous lesions. She was lost to follow-up.

First described by Bazex et al1 in 1965, AP is an uncommon but well-recognized paraneoplastic dermatosis associated with an underlying neoplasm. Fewer than 160 cases have been reported, and the majority of cases have been men older than 40 years. The most commonly associated malignancy was SCC (at least 50% of reported cases) involving mainly the oropharynx and larynx, with lung and esophageal SCC also described.2-4 Only a few cases of adenocarcinoma-associated AP have been described, such as adenocarcinoma of the lung, prostate, and stomach.3-5 In a reported case of AP associated with early colon adenocarcinoma, the patient had remarkable cutaneous resolution following successful tumor resection.6 Other reported rare hematologic associations included Hodgkin disease, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.3-5 Karabulut et al4 described a case associated with cholangiocarcinoma and studied the primary sites of malignancies in another 133 patients with AP (118 patients with documented cell type): oropharynx and larynx in 55 (41%); lung in 23 (17%); unknown location in 20 (15%); esophagus in 14 (11%); prostate in 3 (2%); stomach in 3 (2%); and isolated cases involving the liver, thymus, uterus, vulva, breast, urinary bladder, lymph nodes, and bone marrow.

A review of 113 cases of AP showed that only 15% developed cutaneous lesions after the malignancy had been discovered; in the majority of cases (67%), cutaneous lesions were present for an average of 1 year preceding the diagnosis of malignancy.3 In our patient, the late-onset cutaneous involvement corresponded to the progression of the underlying colon adenocarcinoma. In the absence of initial cutaneous involvement or when successful treatment of a tumor results in cutaneous resolution, subsequent emergence of cutaneous lesions of AP signifies tumor progression. The evolution of cutaneous features in AP was well described by Bazex et al.1 Stage 1 of the disease shows initial erythema and psoriasiform scaling of the fingers and toes, spreading to the nose and ear helices (hence acrokeratosis); the tumor frequently remains asymptomatic or undetected. Stage 2 shows palmoplantar keratoderma with central sparing and more extensive facial lesions; progression to stage 3 occurs if the tumor remains undetected or untreated, with further spread of psoriasiform lesions to the elbows, knees, trunk, and scalp.1 Nail involvement occurs in nearly 75% of cases5; typical changes include subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, longitudinal streaks, yellow pigmentation, and rarely onychomadesis. A high index of suspicion of AP is paramount when evaluating any recalcitrant acral dermatosis that fails to respond to appropriate therapy, especially in the presence of constitutional symptoms, typical bulbous enlargement of distal phalanges, or isolated involvement of helices. These findings should prompt physicians to perform an extensive search for an underlying malignancy with complete physical examination, particularly of the head and neck region, with appropriate endoscopic assessment and imaging studies.

A myriad of nonspecific histologic features of AP commonly reported include hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.7 Less common features include dyskeratotic keratinocytes, vacuolar degeneration, bandlike infiltrate, and melanin incontinence.7 The pathogenesis of AP remains elusive. A postulated immunologic mechanism is based on reports of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) and complement (C3) deposition along the basement membrane zone.8 Association with autoimmune disorders such as alopecia areata and vitiligo also has been reported.9 Another possible mechanism is cross-reactivity between antigens found in the tumor and skin, resulting in a T-cell–mediated immune response to tumorlike antigens in the epidermis, or secretion of tumor-originating growth factors responsible for the hyperkeratotic skin changes, such as epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor a, or insulinlike growth factor 1.3,7,10,11

Spontaneous remission of cutaneous lesions in untreated underlying malignancy is rare. Isolated reports of treatment using topical and systemic steroids, salicylic acid, topical vitamin D analogues, etretinate, and psoralen plus UVA showed minimal improvement.5,7 The mainstay in attaining cutaneous resolution is to detect and eradicate the underlying neoplasm with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, or combination therapy.

Our case is noteworthy because of the patient’s gender (female), underlying malignancy (adenocarcinoma of the colon), and late onset of cutaneous involvement, which are all uncommon associations related to paraneoplastic syndrome. The clinical features of AP should be recognized early to facilitate an extensive search for an occult malignancy, and late-onset cutaneous involvement also should be recognized as a marker of tumor relapse or progression.

1. Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Late symptomatic hepatic porphyria developing to the picture of lipoidoproteinsosis [in French]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

2. Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex’s syndrome. paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

3. Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

4. Karabulut AA, Sahin S, Sahin M, et al. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis of Bazex (Bazex’s syndrome): report of a female case associated with cholangiocarcinoma and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2006;33:850-854.

5. Valdivielso M, Longo I, Suárez R. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica: Bazex syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:340-344.

6. Hsu YS, Lien GS, Lai HH, et al. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) with adenocarcinoma of the colon: report of a case and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:460-464.

7. Bolognia JL, Brewer YP, Cooper DL. Bazex syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica). an analytic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:269-280.

8. Mutasim DF, Meiri G. Bazex syndrome mimicking a primary autoimmune bullous disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5, pt 2):822-825.

9. Hara M, Hunayama M, Aiba S, et al. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) associated with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the lower leg, vitiligo and alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:121-124.

10. Stone SP, Buescher LS. Life-threatening paraneoplastic cutaneous syndromes. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:301-306.

11. Politi Y, Ophir J, Brenner S. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:161-170.

1. Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Late symptomatic hepatic porphyria developing to the picture of lipoidoproteinsosis [in French]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

2. Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex’s syndrome. paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

3. Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

4. Karabulut AA, Sahin S, Sahin M, et al. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis of Bazex (Bazex’s syndrome): report of a female case associated with cholangiocarcinoma and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2006;33:850-854.

5. Valdivielso M, Longo I, Suárez R. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica: Bazex syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:340-344.

6. Hsu YS, Lien GS, Lai HH, et al. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) with adenocarcinoma of the colon: report of a case and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:460-464.

7. Bolognia JL, Brewer YP, Cooper DL. Bazex syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica). an analytic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:269-280.

8. Mutasim DF, Meiri G. Bazex syndrome mimicking a primary autoimmune bullous disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5, pt 2):822-825.

9. Hara M, Hunayama M, Aiba S, et al. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) associated with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the lower leg, vitiligo and alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:121-124.

10. Stone SP, Buescher LS. Life-threatening paraneoplastic cutaneous syndromes. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:301-306.

11. Politi Y, Ophir J, Brenner S. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:161-170.