User login

Mastering the Physical Examination of the Athlete’s Hip

Take-Home Points

- Perform a comprehensive examination to determine intra-articular pathology as well as potential extra-articular sources of hip and pelvic pain.

- Adductor strains can be prevented with adequate rehabilitation focused on correcting predisposing factors (ie, adductor weakness or tightness, limited range of motion, and core imbalance).

- Athletic pubalgia is diagnosed when tenderness can be elicited over the pubic tubercle.

- Osteitis pubis is diagnosed with pain over the pubic symphysis.

- FAI and labral injury classically present with a C-sign but can also present with lateral hip pain, buttock pain, low back pain, anterior thigh pain, and knee pain.

Hip and groin pain is a common finding among athletes of all ages and activity levels. Such pain most often occurs among athletes in sports such as football, hockey, rugby, soccer, and ballet, which demand frequent cutting, pivoting, and acceleration.1-4 Previously, pain about the hip and groin was attributed to muscular strains and soft-tissue contusions, but improvements in physical examination skills, imaging modalities, and disease-specific treatment options have led to increased recognition of hip injuries as a significant source of disability in the athletic population.5,6 These injuries make up 6% or more of all sports injuries, and the rate is increasing.7-9

In this review, we describe precise methods for evaluating the athlete’s hip or groin with an emphasis on recognizing the most common extra-articular and intra-articular pathologies, including adductor strains, athletic pubalgia, osteitis pubis, and femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) with labral tears.

Hip Pathoanatomy

The first step in determining the etiology of pain is to establish if there is true pathology of the hip joint and surrounding structures, or if the pain is referred from another source.

Patient History

The physical examination is guided by the patient’s history. Important patient-specific factors to be ascertained include age, sport(s) played, competition level, seasonal timing, and effect of the injury on performance. Regarding presenting symptoms, attention should be given to pain location, timing (acute vs chronic), onset, nature (clicking, catching, instability), and precipitating factors. Acute-onset pain with muscle contraction or stretching, possibly accompanied by an audible pop, is likely musculotendinous in origin. Insidious-onset dull aching pain that worsens with activity more commonly involves intra-articular processes. Most classically, this pain occurs deep in the groin and is demonstrated by the C sign: The patient cups a hand with its fingers pointing toward the anterior groin at the level of the greater trochanter (Figure 1).11

A comprehensive hip evaluation can be performed with the patient in the standing, seated, supine, lateral, and prone positions, as previously described (Table 2).6,12,13

Extra-Articular Hip Pathologies

Adductor Strains

The adductor muscle group includes the adductor magnus, adductor brevis, gracilis, obturator externus, pectineus, and adductor longus, which is the most commonly strained. Adductor strains are the most common cause of groin pain in athletes, and usually occur in sports that require forceful eccentric contraction of the adductors.14 Among professional soccer players, adductor strains represent almost one fourth of all muscle injuries and result in lost playing time averaging 2 weeks and an 18% reinjury rate.15 These injuries are particularly detrimental to performance because the adductor muscles help stabilize the pelvis during closed-chain activities.3 Diagnosis and adequate rehabilitation focused on correcting predisposing factors (eg, adductor weakness or tightness, loss of hip range of motion, core imbalance) are paramount in reinjury prevention.16,17

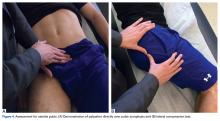

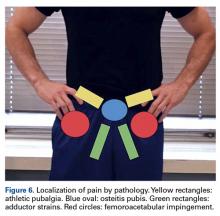

On presentation, athletes complain of aching groin or medial thigh pain. The examiner should assess for swelling or ecchymosis. There typically is tenderness to palpation at or near the origin on the pubic bones, with pain exacerbated with resisted adduction and passive stretch into abduction during examination. Palpation of adductors requires proper exposure and is most easily performed with the patient supine and the lower extremity in a figure-of-4 position (Figure 2A).

Athletic Pubalgia

Athletic pubalgia, also known as sports hernia or core muscle injury, is an injury to the soft tissues of the lower abdominal or posterior inguinal wall. Although not fully understood, the condition is considered the result of repetitive trunk hyperextension and thigh hyperabduction resulting in shearing at the pubic symphysis where there is a muscle imbalance between the strong proximal thigh muscles and weaker abdominals. This condition is more common in men and typically is insidious in onset with a prolonged course recalcitrant to nonoperative treatment.18 In studies of chronic groin pain in athletes, the rate of athletic pubalgia as the primary etiology ranges from 39% to 85%.9,19,20

Patients typically complain of increasing pain in the lower abdominal and proximal adductors during activity. Symptoms include unilateral or bilateral lower abdominal pain, which can radiate toward the perineum, rectus muscle, and proximal adductors during sport but usually abates with rest.18 Athletes endorse they are not capable of playing at their full athletic potential. Symptoms are initiated with sudden forceful movements, as in sit-ups, sprints, and valsalva maneuvers like coughs and sneezes. Valsalva maneuvers worsen pain in about 10% of patients.21-23On physical examination with the patient supine, tenderness can be elicited over the pubic tubercle, abdominal obliques, and/or rectus abdominis insertion (Figure 3A). Athletes may also have tenderness at the adductor longus tendon origin at or near the pubic symphysis, which may make the diagnosis difficult to distinguish from an adductor strain.

Osteitis Pubis

Osteitis pubis is a painful overuse injury that results in noninfectious inflammation of the pubic symphysis from increased motion at this normally stable immobile joint.3 As with athletic pubalgia, the exact mechanism is unclear, but likely it is similar to the repetitive stress placed on the pubic symphysis by unequal forces of the abdominal and adductor muscles.24 The disease can result in bony erosions and cartilage breakdown with irregularity of the pubic symphysis.

Athletes may complain of anterior and medial groin pain that can radiate to the lower abdominal muscles, perineum, inguinal region, and medial thigh. Walking, pelvic motion, adductor stretching, abdominal muscle exercises, and standing up can exacerbate pain.24 Some cases involve impaired internal or external rotation of the hip, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, or adductor and abductor muscle weakness.25The distinguishing feature of osteitis pubis is pain over the pubic symphysis with direct palpation (Figure 4A). Examination maneuvers that place stress on the pubic symphysis can aid in diagnosis.26

Intra-Articular Hip Pathology: Femoroacetabular Impingement

In athletes, FAI is a leading cause of intra-articular pathology, which can lead to labral tears.28,29 FAI lesions include cam-type impingement from an aspherical femoral head and pincer impingement from acetabular overcoverage, both of which limit internal rotation and cause acetabular rim abutment, which damages the labrum.

Athletes present with activity-related groin or hip pain that is exacerbated by hip flexion and internal rotation, with possible mechanical symptoms from labral tearing.30 However, the pain distribution varies. In a study by Clohisy and colleagues,31 of patients with symptomatic FAI that required surgical intervention, 88% had groin pain, 67% had lateral hip pain, 35% had anterior thigh pain, 29% had buttock pain, 27% had knee pain, and 23% had low back pain.

Careful attention should be given to range of motion in FAI patients, as they can usually flex their hip to 90° to 110°, and in this position there is limited internal rotation and asymmetric external rotation relative to the contralateral leg.32 The anterior impingement test is one of the most reliable tests for FAI (Figure 5A).32 With the patient supine, the hip is dynamically flexed to 90°, adducted, and internally rotated. A positive test elicits deep anterior groin pain that generally replicates the patient’s symptoms.29

Conclusion

Careful, directed history taking and physical examination are essential in narrowing the diagnostic possibilities before initiating a workup for the common intra-articular and extra-articular causes of hip and groin pain in athletes.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):10-16. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Boyd KT, Peirce NS, Batt ME. Common hip injuries in sport. Sports Med. 1997;24(4):273-288.

2. Duthon VB, Charbonnier C, Kolo FC, et al. Correlation of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings in hips of elite female ballet dancers. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):411-419.

3. Prather H, Cheng A. Diagnosis and treatment of hip girdle pain in the athlete. PM R. 2016;8(3 suppl):S45-S60.

4. Larson CM. Sports hernia/athletic pubalgia: evaluation and management. Sports Health. 2014;6(2):139-144.

5. Bizzini M, Notzli HP, Maffiuletti NA. Femoroacetabular impingement in professional ice hockey players: a case series of 5 athletes after open surgical decompression of the hip. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1955-1959.

6. Lynch TS, Terry MA, Bedi A, Kelly BT. Hip arthroscopic surgery: patient evaluation, current indications, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1174-1189.

7. Anderson K, Strickland SM, Warren R. Hip and groin injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):521-533.

8. Fon LJ, Spence RA. Sportsman’s hernia. Br J Surg. 2000;87(5):545-552.

9. Kluin J, den Hoed PT, van Linschoten R, IJzerman JC, van Steensel CJ. Endoscopic evaluation and treatment of groin pain in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):944-949.

10. Ward D, Parvizi J. Management of hip pain in young adults. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(3):485-496.

11. Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(7):433-444.

12. Martin HD, Palmer IJ. History and physical examination of the hip: the basics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(3):219-225.

13. Shindle MK, Voos JE, Nho SJ, Heyworth BE, Kelly BT. Arthroscopic management of labral tears in the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 4):2-19.

14. Morelli V, Smith V. Groin injuries in athletes. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(8):1405-1414.

15. Ekstrand J, Hagglund M, Walden M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1226-1232.

16. Ekstrand J, Gillquist J. The avoidability of soccer injuries. Int J Sports Med. 1983;4(2):124-128.

17. Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Campbell RJ, McHugh MP. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):124-128.

18. Farber AJ, Wilckens JH. Sports hernia: diagnosis and therapeutic approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(8):507-514.

19. De Paulis F, Cacchio A, Michelini O, Damiani A, Saggini R. Sports injuries in the pelvis and hip: diagnostic imaging. Eur J Radiol. 1998;27(suppl 1):S49-S59.

20. Lovell G. The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes: a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1995;27(suppl 1):76-79.

21. Strosberg DS, Ellis TJ, Renton DB. The role of femoroacetabular impingement in core muscle injury/athletic pubalgia: diagnosis and management. Front Surg. 2016;3:6.

22. Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, Lohnes JH, Mandlebaum BR. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes. PAIN (Performing Athletes with Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group). Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):2-8.

23. Ahumada LA, Ashruf S, Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, et al. Athletic pubalgia: definition and surgical treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(4):393-396.

24. Angoules AG. Osteitis pubis in elite athletes: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Orthop. 2015;6(9):672-679.

25. Hiti CJ, Stevens KJ, Jamati MK, Garza D, Matheson GO. Athletic osteitis pubis. Sports Med. 2011;41(5):361-376.

26. Mehin R, Meek R, O’Brien P, Blachut P. Surgery for osteitis pubis. Can J Surg. 2006;49(3):170-176.

27. Grace JN, Sim FH, Shives TC, Coventry MB. Wedge resection of the symphysis pubis for the treatment of osteitis pubis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(3):358-364.

28. Amanatullah DF, Antkowiak T, Pillay K, et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: current concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Orthopedics. 2015;38(3):185-199.

29. Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112-120.

30. Redmond JM, Gupta A, Hammarstedt JE, Stake CE, Dunne KF, Domb BG. Labral injury: radiographic predictors at the time of hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(1):51-56.

31. Clohisy JC, Knaus ER, Hunt DM, Lesher JM, Harris-Hayes M, Prather H. Clinical presentation of patients with symptomatic anterior hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):638-644.

32. Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(3):423-429.

33. Philippon MJ, Schenker ML. Arthroscopy for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(2):299-308.

34. McCarthy JC, Lee JA. Hip arthroscopy: indications, outcomes, and complications. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:301-308.

Take-Home Points

- Perform a comprehensive examination to determine intra-articular pathology as well as potential extra-articular sources of hip and pelvic pain.

- Adductor strains can be prevented with adequate rehabilitation focused on correcting predisposing factors (ie, adductor weakness or tightness, limited range of motion, and core imbalance).

- Athletic pubalgia is diagnosed when tenderness can be elicited over the pubic tubercle.

- Osteitis pubis is diagnosed with pain over the pubic symphysis.

- FAI and labral injury classically present with a C-sign but can also present with lateral hip pain, buttock pain, low back pain, anterior thigh pain, and knee pain.

Hip and groin pain is a common finding among athletes of all ages and activity levels. Such pain most often occurs among athletes in sports such as football, hockey, rugby, soccer, and ballet, which demand frequent cutting, pivoting, and acceleration.1-4 Previously, pain about the hip and groin was attributed to muscular strains and soft-tissue contusions, but improvements in physical examination skills, imaging modalities, and disease-specific treatment options have led to increased recognition of hip injuries as a significant source of disability in the athletic population.5,6 These injuries make up 6% or more of all sports injuries, and the rate is increasing.7-9

In this review, we describe precise methods for evaluating the athlete’s hip or groin with an emphasis on recognizing the most common extra-articular and intra-articular pathologies, including adductor strains, athletic pubalgia, osteitis pubis, and femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) with labral tears.

Hip Pathoanatomy

The first step in determining the etiology of pain is to establish if there is true pathology of the hip joint and surrounding structures, or if the pain is referred from another source.

Patient History

The physical examination is guided by the patient’s history. Important patient-specific factors to be ascertained include age, sport(s) played, competition level, seasonal timing, and effect of the injury on performance. Regarding presenting symptoms, attention should be given to pain location, timing (acute vs chronic), onset, nature (clicking, catching, instability), and precipitating factors. Acute-onset pain with muscle contraction or stretching, possibly accompanied by an audible pop, is likely musculotendinous in origin. Insidious-onset dull aching pain that worsens with activity more commonly involves intra-articular processes. Most classically, this pain occurs deep in the groin and is demonstrated by the C sign: The patient cups a hand with its fingers pointing toward the anterior groin at the level of the greater trochanter (Figure 1).11

A comprehensive hip evaluation can be performed with the patient in the standing, seated, supine, lateral, and prone positions, as previously described (Table 2).6,12,13

Extra-Articular Hip Pathologies

Adductor Strains

The adductor muscle group includes the adductor magnus, adductor brevis, gracilis, obturator externus, pectineus, and adductor longus, which is the most commonly strained. Adductor strains are the most common cause of groin pain in athletes, and usually occur in sports that require forceful eccentric contraction of the adductors.14 Among professional soccer players, adductor strains represent almost one fourth of all muscle injuries and result in lost playing time averaging 2 weeks and an 18% reinjury rate.15 These injuries are particularly detrimental to performance because the adductor muscles help stabilize the pelvis during closed-chain activities.3 Diagnosis and adequate rehabilitation focused on correcting predisposing factors (eg, adductor weakness or tightness, loss of hip range of motion, core imbalance) are paramount in reinjury prevention.16,17

On presentation, athletes complain of aching groin or medial thigh pain. The examiner should assess for swelling or ecchymosis. There typically is tenderness to palpation at or near the origin on the pubic bones, with pain exacerbated with resisted adduction and passive stretch into abduction during examination. Palpation of adductors requires proper exposure and is most easily performed with the patient supine and the lower extremity in a figure-of-4 position (Figure 2A).

Athletic Pubalgia

Athletic pubalgia, also known as sports hernia or core muscle injury, is an injury to the soft tissues of the lower abdominal or posterior inguinal wall. Although not fully understood, the condition is considered the result of repetitive trunk hyperextension and thigh hyperabduction resulting in shearing at the pubic symphysis where there is a muscle imbalance between the strong proximal thigh muscles and weaker abdominals. This condition is more common in men and typically is insidious in onset with a prolonged course recalcitrant to nonoperative treatment.18 In studies of chronic groin pain in athletes, the rate of athletic pubalgia as the primary etiology ranges from 39% to 85%.9,19,20

Patients typically complain of increasing pain in the lower abdominal and proximal adductors during activity. Symptoms include unilateral or bilateral lower abdominal pain, which can radiate toward the perineum, rectus muscle, and proximal adductors during sport but usually abates with rest.18 Athletes endorse they are not capable of playing at their full athletic potential. Symptoms are initiated with sudden forceful movements, as in sit-ups, sprints, and valsalva maneuvers like coughs and sneezes. Valsalva maneuvers worsen pain in about 10% of patients.21-23On physical examination with the patient supine, tenderness can be elicited over the pubic tubercle, abdominal obliques, and/or rectus abdominis insertion (Figure 3A). Athletes may also have tenderness at the adductor longus tendon origin at or near the pubic symphysis, which may make the diagnosis difficult to distinguish from an adductor strain.

Osteitis Pubis

Osteitis pubis is a painful overuse injury that results in noninfectious inflammation of the pubic symphysis from increased motion at this normally stable immobile joint.3 As with athletic pubalgia, the exact mechanism is unclear, but likely it is similar to the repetitive stress placed on the pubic symphysis by unequal forces of the abdominal and adductor muscles.24 The disease can result in bony erosions and cartilage breakdown with irregularity of the pubic symphysis.

Athletes may complain of anterior and medial groin pain that can radiate to the lower abdominal muscles, perineum, inguinal region, and medial thigh. Walking, pelvic motion, adductor stretching, abdominal muscle exercises, and standing up can exacerbate pain.24 Some cases involve impaired internal or external rotation of the hip, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, or adductor and abductor muscle weakness.25The distinguishing feature of osteitis pubis is pain over the pubic symphysis with direct palpation (Figure 4A). Examination maneuvers that place stress on the pubic symphysis can aid in diagnosis.26

Intra-Articular Hip Pathology: Femoroacetabular Impingement

In athletes, FAI is a leading cause of intra-articular pathology, which can lead to labral tears.28,29 FAI lesions include cam-type impingement from an aspherical femoral head and pincer impingement from acetabular overcoverage, both of which limit internal rotation and cause acetabular rim abutment, which damages the labrum.

Athletes present with activity-related groin or hip pain that is exacerbated by hip flexion and internal rotation, with possible mechanical symptoms from labral tearing.30 However, the pain distribution varies. In a study by Clohisy and colleagues,31 of patients with symptomatic FAI that required surgical intervention, 88% had groin pain, 67% had lateral hip pain, 35% had anterior thigh pain, 29% had buttock pain, 27% had knee pain, and 23% had low back pain.

Careful attention should be given to range of motion in FAI patients, as they can usually flex their hip to 90° to 110°, and in this position there is limited internal rotation and asymmetric external rotation relative to the contralateral leg.32 The anterior impingement test is one of the most reliable tests for FAI (Figure 5A).32 With the patient supine, the hip is dynamically flexed to 90°, adducted, and internally rotated. A positive test elicits deep anterior groin pain that generally replicates the patient’s symptoms.29

Conclusion

Careful, directed history taking and physical examination are essential in narrowing the diagnostic possibilities before initiating a workup for the common intra-articular and extra-articular causes of hip and groin pain in athletes.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):10-16. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Perform a comprehensive examination to determine intra-articular pathology as well as potential extra-articular sources of hip and pelvic pain.

- Adductor strains can be prevented with adequate rehabilitation focused on correcting predisposing factors (ie, adductor weakness or tightness, limited range of motion, and core imbalance).

- Athletic pubalgia is diagnosed when tenderness can be elicited over the pubic tubercle.

- Osteitis pubis is diagnosed with pain over the pubic symphysis.

- FAI and labral injury classically present with a C-sign but can also present with lateral hip pain, buttock pain, low back pain, anterior thigh pain, and knee pain.

Hip and groin pain is a common finding among athletes of all ages and activity levels. Such pain most often occurs among athletes in sports such as football, hockey, rugby, soccer, and ballet, which demand frequent cutting, pivoting, and acceleration.1-4 Previously, pain about the hip and groin was attributed to muscular strains and soft-tissue contusions, but improvements in physical examination skills, imaging modalities, and disease-specific treatment options have led to increased recognition of hip injuries as a significant source of disability in the athletic population.5,6 These injuries make up 6% or more of all sports injuries, and the rate is increasing.7-9

In this review, we describe precise methods for evaluating the athlete’s hip or groin with an emphasis on recognizing the most common extra-articular and intra-articular pathologies, including adductor strains, athletic pubalgia, osteitis pubis, and femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) with labral tears.

Hip Pathoanatomy

The first step in determining the etiology of pain is to establish if there is true pathology of the hip joint and surrounding structures, or if the pain is referred from another source.

Patient History

The physical examination is guided by the patient’s history. Important patient-specific factors to be ascertained include age, sport(s) played, competition level, seasonal timing, and effect of the injury on performance. Regarding presenting symptoms, attention should be given to pain location, timing (acute vs chronic), onset, nature (clicking, catching, instability), and precipitating factors. Acute-onset pain with muscle contraction or stretching, possibly accompanied by an audible pop, is likely musculotendinous in origin. Insidious-onset dull aching pain that worsens with activity more commonly involves intra-articular processes. Most classically, this pain occurs deep in the groin and is demonstrated by the C sign: The patient cups a hand with its fingers pointing toward the anterior groin at the level of the greater trochanter (Figure 1).11

A comprehensive hip evaluation can be performed with the patient in the standing, seated, supine, lateral, and prone positions, as previously described (Table 2).6,12,13

Extra-Articular Hip Pathologies

Adductor Strains

The adductor muscle group includes the adductor magnus, adductor brevis, gracilis, obturator externus, pectineus, and adductor longus, which is the most commonly strained. Adductor strains are the most common cause of groin pain in athletes, and usually occur in sports that require forceful eccentric contraction of the adductors.14 Among professional soccer players, adductor strains represent almost one fourth of all muscle injuries and result in lost playing time averaging 2 weeks and an 18% reinjury rate.15 These injuries are particularly detrimental to performance because the adductor muscles help stabilize the pelvis during closed-chain activities.3 Diagnosis and adequate rehabilitation focused on correcting predisposing factors (eg, adductor weakness or tightness, loss of hip range of motion, core imbalance) are paramount in reinjury prevention.16,17

On presentation, athletes complain of aching groin or medial thigh pain. The examiner should assess for swelling or ecchymosis. There typically is tenderness to palpation at or near the origin on the pubic bones, with pain exacerbated with resisted adduction and passive stretch into abduction during examination. Palpation of adductors requires proper exposure and is most easily performed with the patient supine and the lower extremity in a figure-of-4 position (Figure 2A).

Athletic Pubalgia

Athletic pubalgia, also known as sports hernia or core muscle injury, is an injury to the soft tissues of the lower abdominal or posterior inguinal wall. Although not fully understood, the condition is considered the result of repetitive trunk hyperextension and thigh hyperabduction resulting in shearing at the pubic symphysis where there is a muscle imbalance between the strong proximal thigh muscles and weaker abdominals. This condition is more common in men and typically is insidious in onset with a prolonged course recalcitrant to nonoperative treatment.18 In studies of chronic groin pain in athletes, the rate of athletic pubalgia as the primary etiology ranges from 39% to 85%.9,19,20

Patients typically complain of increasing pain in the lower abdominal and proximal adductors during activity. Symptoms include unilateral or bilateral lower abdominal pain, which can radiate toward the perineum, rectus muscle, and proximal adductors during sport but usually abates with rest.18 Athletes endorse they are not capable of playing at their full athletic potential. Symptoms are initiated with sudden forceful movements, as in sit-ups, sprints, and valsalva maneuvers like coughs and sneezes. Valsalva maneuvers worsen pain in about 10% of patients.21-23On physical examination with the patient supine, tenderness can be elicited over the pubic tubercle, abdominal obliques, and/or rectus abdominis insertion (Figure 3A). Athletes may also have tenderness at the adductor longus tendon origin at or near the pubic symphysis, which may make the diagnosis difficult to distinguish from an adductor strain.

Osteitis Pubis

Osteitis pubis is a painful overuse injury that results in noninfectious inflammation of the pubic symphysis from increased motion at this normally stable immobile joint.3 As with athletic pubalgia, the exact mechanism is unclear, but likely it is similar to the repetitive stress placed on the pubic symphysis by unequal forces of the abdominal and adductor muscles.24 The disease can result in bony erosions and cartilage breakdown with irregularity of the pubic symphysis.

Athletes may complain of anterior and medial groin pain that can radiate to the lower abdominal muscles, perineum, inguinal region, and medial thigh. Walking, pelvic motion, adductor stretching, abdominal muscle exercises, and standing up can exacerbate pain.24 Some cases involve impaired internal or external rotation of the hip, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, or adductor and abductor muscle weakness.25The distinguishing feature of osteitis pubis is pain over the pubic symphysis with direct palpation (Figure 4A). Examination maneuvers that place stress on the pubic symphysis can aid in diagnosis.26

Intra-Articular Hip Pathology: Femoroacetabular Impingement

In athletes, FAI is a leading cause of intra-articular pathology, which can lead to labral tears.28,29 FAI lesions include cam-type impingement from an aspherical femoral head and pincer impingement from acetabular overcoverage, both of which limit internal rotation and cause acetabular rim abutment, which damages the labrum.

Athletes present with activity-related groin or hip pain that is exacerbated by hip flexion and internal rotation, with possible mechanical symptoms from labral tearing.30 However, the pain distribution varies. In a study by Clohisy and colleagues,31 of patients with symptomatic FAI that required surgical intervention, 88% had groin pain, 67% had lateral hip pain, 35% had anterior thigh pain, 29% had buttock pain, 27% had knee pain, and 23% had low back pain.

Careful attention should be given to range of motion in FAI patients, as they can usually flex their hip to 90° to 110°, and in this position there is limited internal rotation and asymmetric external rotation relative to the contralateral leg.32 The anterior impingement test is one of the most reliable tests for FAI (Figure 5A).32 With the patient supine, the hip is dynamically flexed to 90°, adducted, and internally rotated. A positive test elicits deep anterior groin pain that generally replicates the patient’s symptoms.29

Conclusion

Careful, directed history taking and physical examination are essential in narrowing the diagnostic possibilities before initiating a workup for the common intra-articular and extra-articular causes of hip and groin pain in athletes.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):10-16. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Boyd KT, Peirce NS, Batt ME. Common hip injuries in sport. Sports Med. 1997;24(4):273-288.

2. Duthon VB, Charbonnier C, Kolo FC, et al. Correlation of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings in hips of elite female ballet dancers. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):411-419.

3. Prather H, Cheng A. Diagnosis and treatment of hip girdle pain in the athlete. PM R. 2016;8(3 suppl):S45-S60.

4. Larson CM. Sports hernia/athletic pubalgia: evaluation and management. Sports Health. 2014;6(2):139-144.

5. Bizzini M, Notzli HP, Maffiuletti NA. Femoroacetabular impingement in professional ice hockey players: a case series of 5 athletes after open surgical decompression of the hip. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1955-1959.

6. Lynch TS, Terry MA, Bedi A, Kelly BT. Hip arthroscopic surgery: patient evaluation, current indications, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1174-1189.

7. Anderson K, Strickland SM, Warren R. Hip and groin injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):521-533.

8. Fon LJ, Spence RA. Sportsman’s hernia. Br J Surg. 2000;87(5):545-552.

9. Kluin J, den Hoed PT, van Linschoten R, IJzerman JC, van Steensel CJ. Endoscopic evaluation and treatment of groin pain in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):944-949.

10. Ward D, Parvizi J. Management of hip pain in young adults. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(3):485-496.

11. Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(7):433-444.

12. Martin HD, Palmer IJ. History and physical examination of the hip: the basics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(3):219-225.

13. Shindle MK, Voos JE, Nho SJ, Heyworth BE, Kelly BT. Arthroscopic management of labral tears in the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 4):2-19.

14. Morelli V, Smith V. Groin injuries in athletes. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(8):1405-1414.

15. Ekstrand J, Hagglund M, Walden M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1226-1232.

16. Ekstrand J, Gillquist J. The avoidability of soccer injuries. Int J Sports Med. 1983;4(2):124-128.

17. Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Campbell RJ, McHugh MP. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):124-128.

18. Farber AJ, Wilckens JH. Sports hernia: diagnosis and therapeutic approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(8):507-514.

19. De Paulis F, Cacchio A, Michelini O, Damiani A, Saggini R. Sports injuries in the pelvis and hip: diagnostic imaging. Eur J Radiol. 1998;27(suppl 1):S49-S59.

20. Lovell G. The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes: a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1995;27(suppl 1):76-79.

21. Strosberg DS, Ellis TJ, Renton DB. The role of femoroacetabular impingement in core muscle injury/athletic pubalgia: diagnosis and management. Front Surg. 2016;3:6.

22. Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, Lohnes JH, Mandlebaum BR. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes. PAIN (Performing Athletes with Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group). Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):2-8.

23. Ahumada LA, Ashruf S, Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, et al. Athletic pubalgia: definition and surgical treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(4):393-396.

24. Angoules AG. Osteitis pubis in elite athletes: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Orthop. 2015;6(9):672-679.

25. Hiti CJ, Stevens KJ, Jamati MK, Garza D, Matheson GO. Athletic osteitis pubis. Sports Med. 2011;41(5):361-376.

26. Mehin R, Meek R, O’Brien P, Blachut P. Surgery for osteitis pubis. Can J Surg. 2006;49(3):170-176.

27. Grace JN, Sim FH, Shives TC, Coventry MB. Wedge resection of the symphysis pubis for the treatment of osteitis pubis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(3):358-364.

28. Amanatullah DF, Antkowiak T, Pillay K, et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: current concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Orthopedics. 2015;38(3):185-199.

29. Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112-120.

30. Redmond JM, Gupta A, Hammarstedt JE, Stake CE, Dunne KF, Domb BG. Labral injury: radiographic predictors at the time of hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(1):51-56.

31. Clohisy JC, Knaus ER, Hunt DM, Lesher JM, Harris-Hayes M, Prather H. Clinical presentation of patients with symptomatic anterior hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):638-644.

32. Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(3):423-429.

33. Philippon MJ, Schenker ML. Arthroscopy for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(2):299-308.

34. McCarthy JC, Lee JA. Hip arthroscopy: indications, outcomes, and complications. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:301-308.

1. Boyd KT, Peirce NS, Batt ME. Common hip injuries in sport. Sports Med. 1997;24(4):273-288.

2. Duthon VB, Charbonnier C, Kolo FC, et al. Correlation of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings in hips of elite female ballet dancers. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):411-419.

3. Prather H, Cheng A. Diagnosis and treatment of hip girdle pain in the athlete. PM R. 2016;8(3 suppl):S45-S60.

4. Larson CM. Sports hernia/athletic pubalgia: evaluation and management. Sports Health. 2014;6(2):139-144.

5. Bizzini M, Notzli HP, Maffiuletti NA. Femoroacetabular impingement in professional ice hockey players: a case series of 5 athletes after open surgical decompression of the hip. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1955-1959.

6. Lynch TS, Terry MA, Bedi A, Kelly BT. Hip arthroscopic surgery: patient evaluation, current indications, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1174-1189.

7. Anderson K, Strickland SM, Warren R. Hip and groin injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):521-533.

8. Fon LJ, Spence RA. Sportsman’s hernia. Br J Surg. 2000;87(5):545-552.

9. Kluin J, den Hoed PT, van Linschoten R, IJzerman JC, van Steensel CJ. Endoscopic evaluation and treatment of groin pain in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):944-949.

10. Ward D, Parvizi J. Management of hip pain in young adults. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(3):485-496.

11. Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(7):433-444.

12. Martin HD, Palmer IJ. History and physical examination of the hip: the basics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(3):219-225.

13. Shindle MK, Voos JE, Nho SJ, Heyworth BE, Kelly BT. Arthroscopic management of labral tears in the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 4):2-19.

14. Morelli V, Smith V. Groin injuries in athletes. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(8):1405-1414.

15. Ekstrand J, Hagglund M, Walden M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1226-1232.

16. Ekstrand J, Gillquist J. The avoidability of soccer injuries. Int J Sports Med. 1983;4(2):124-128.

17. Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Campbell RJ, McHugh MP. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):124-128.

18. Farber AJ, Wilckens JH. Sports hernia: diagnosis and therapeutic approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(8):507-514.

19. De Paulis F, Cacchio A, Michelini O, Damiani A, Saggini R. Sports injuries in the pelvis and hip: diagnostic imaging. Eur J Radiol. 1998;27(suppl 1):S49-S59.

20. Lovell G. The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes: a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1995;27(suppl 1):76-79.

21. Strosberg DS, Ellis TJ, Renton DB. The role of femoroacetabular impingement in core muscle injury/athletic pubalgia: diagnosis and management. Front Surg. 2016;3:6.

22. Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, Lohnes JH, Mandlebaum BR. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes. PAIN (Performing Athletes with Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group). Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):2-8.

23. Ahumada LA, Ashruf S, Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, et al. Athletic pubalgia: definition and surgical treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(4):393-396.

24. Angoules AG. Osteitis pubis in elite athletes: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Orthop. 2015;6(9):672-679.

25. Hiti CJ, Stevens KJ, Jamati MK, Garza D, Matheson GO. Athletic osteitis pubis. Sports Med. 2011;41(5):361-376.

26. Mehin R, Meek R, O’Brien P, Blachut P. Surgery for osteitis pubis. Can J Surg. 2006;49(3):170-176.

27. Grace JN, Sim FH, Shives TC, Coventry MB. Wedge resection of the symphysis pubis for the treatment of osteitis pubis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(3):358-364.

28. Amanatullah DF, Antkowiak T, Pillay K, et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: current concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Orthopedics. 2015;38(3):185-199.

29. Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112-120.

30. Redmond JM, Gupta A, Hammarstedt JE, Stake CE, Dunne KF, Domb BG. Labral injury: radiographic predictors at the time of hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(1):51-56.

31. Clohisy JC, Knaus ER, Hunt DM, Lesher JM, Harris-Hayes M, Prather H. Clinical presentation of patients with symptomatic anterior hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):638-644.

32. Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(3):423-429.

33. Philippon MJ, Schenker ML. Arthroscopy for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(2):299-308.

34. McCarthy JC, Lee JA. Hip arthroscopy: indications, outcomes, and complications. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:301-308.