User login

Vulvar and gluteal manifestations of Crohn disease

A 37-year-old woman presented with recurring painful swelling and erythema of the vulva over the last year. Despite a series of negative vaginal cultures, she was prescribed multiple courses of antifungal and antibacterial treatments, while her symptoms continued to worsen. She had no other relevant medical history except for occasional diarrhea and abdominal cramping, which were attributed to irritable bowel syndrome.

CROHN DISEASE OUTSIDE THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Crohn disease primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract but is associated with extraintestinal manifestations (in the oral cavity, eyes, skin, and joints) in up to 45% of patients.1

The most common mucocutaneous manifestations are granulomatous lesions that extend directly from the gastrointestinal tract, including perianal and peristomal skin tags, fistulas, and perineal ulcerations. In most cases, the onset of cutaneous manifestations follows intestinal disease, but vulvar Crohn disease may precede gastrointestinal symptoms in approximately 25% of patients, with the average age at onset in the mid-30s.1

The pathogenesis of vulvar Crohn disease remains unclear. One theory involves production of immune complexes from the gastrointestinal tract and a possible T-lymphocyte-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction.2

The diagnosis of vulvar Crohn disease should be considered in a patient who has vulvar pain, edema, and ulcerations not otherwise explained, whether or not gastrointestinal Crohn disease is present. The diagnosis is established with clinical history and characteristic histopathology on biopsy. Multiple biopsies may be needed, and early endoscopy is recommended to establish the diagnosis. The histologic features include noncaseating and nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis or vulvitis with occasional reports of eosinophilic infiltrates and necrobiosis.5,6 An imaging study such as ultrasonography is sometimes used to differentiate between a specific cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease and its complications such as perianal fistula or abscess.

Clinical vulvar lesions are nonspecific, and those of Crohn disease are frequently mistaken for infectious, inflammatory, or traumatic vulvitis. Diagnostic biopsy for histologic analysis is warranted.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, Gravante G, Giordano P. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg 2010; 8(1):2–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.012

- Siroy A, Wasman J. Metastatic Crohn disease: a rare cutaneous entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136(3):329–332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Selim MA. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2011; 33(6):588–593. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31820a2635

- Amankwah Y, Haefner H. Vulvar edema. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28(4):765–777. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.001

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35(5):457–461. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00849.x

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 1996; 132(8):928–932.

A 37-year-old woman presented with recurring painful swelling and erythema of the vulva over the last year. Despite a series of negative vaginal cultures, she was prescribed multiple courses of antifungal and antibacterial treatments, while her symptoms continued to worsen. She had no other relevant medical history except for occasional diarrhea and abdominal cramping, which were attributed to irritable bowel syndrome.

CROHN DISEASE OUTSIDE THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Crohn disease primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract but is associated with extraintestinal manifestations (in the oral cavity, eyes, skin, and joints) in up to 45% of patients.1

The most common mucocutaneous manifestations are granulomatous lesions that extend directly from the gastrointestinal tract, including perianal and peristomal skin tags, fistulas, and perineal ulcerations. In most cases, the onset of cutaneous manifestations follows intestinal disease, but vulvar Crohn disease may precede gastrointestinal symptoms in approximately 25% of patients, with the average age at onset in the mid-30s.1

The pathogenesis of vulvar Crohn disease remains unclear. One theory involves production of immune complexes from the gastrointestinal tract and a possible T-lymphocyte-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction.2

The diagnosis of vulvar Crohn disease should be considered in a patient who has vulvar pain, edema, and ulcerations not otherwise explained, whether or not gastrointestinal Crohn disease is present. The diagnosis is established with clinical history and characteristic histopathology on biopsy. Multiple biopsies may be needed, and early endoscopy is recommended to establish the diagnosis. The histologic features include noncaseating and nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis or vulvitis with occasional reports of eosinophilic infiltrates and necrobiosis.5,6 An imaging study such as ultrasonography is sometimes used to differentiate between a specific cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease and its complications such as perianal fistula or abscess.

Clinical vulvar lesions are nonspecific, and those of Crohn disease are frequently mistaken for infectious, inflammatory, or traumatic vulvitis. Diagnostic biopsy for histologic analysis is warranted.

A 37-year-old woman presented with recurring painful swelling and erythema of the vulva over the last year. Despite a series of negative vaginal cultures, she was prescribed multiple courses of antifungal and antibacterial treatments, while her symptoms continued to worsen. She had no other relevant medical history except for occasional diarrhea and abdominal cramping, which were attributed to irritable bowel syndrome.

CROHN DISEASE OUTSIDE THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Crohn disease primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract but is associated with extraintestinal manifestations (in the oral cavity, eyes, skin, and joints) in up to 45% of patients.1

The most common mucocutaneous manifestations are granulomatous lesions that extend directly from the gastrointestinal tract, including perianal and peristomal skin tags, fistulas, and perineal ulcerations. In most cases, the onset of cutaneous manifestations follows intestinal disease, but vulvar Crohn disease may precede gastrointestinal symptoms in approximately 25% of patients, with the average age at onset in the mid-30s.1

The pathogenesis of vulvar Crohn disease remains unclear. One theory involves production of immune complexes from the gastrointestinal tract and a possible T-lymphocyte-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction.2

The diagnosis of vulvar Crohn disease should be considered in a patient who has vulvar pain, edema, and ulcerations not otherwise explained, whether or not gastrointestinal Crohn disease is present. The diagnosis is established with clinical history and characteristic histopathology on biopsy. Multiple biopsies may be needed, and early endoscopy is recommended to establish the diagnosis. The histologic features include noncaseating and nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis or vulvitis with occasional reports of eosinophilic infiltrates and necrobiosis.5,6 An imaging study such as ultrasonography is sometimes used to differentiate between a specific cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease and its complications such as perianal fistula or abscess.

Clinical vulvar lesions are nonspecific, and those of Crohn disease are frequently mistaken for infectious, inflammatory, or traumatic vulvitis. Diagnostic biopsy for histologic analysis is warranted.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, Gravante G, Giordano P. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg 2010; 8(1):2–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.012

- Siroy A, Wasman J. Metastatic Crohn disease: a rare cutaneous entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136(3):329–332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Selim MA. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2011; 33(6):588–593. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31820a2635

- Amankwah Y, Haefner H. Vulvar edema. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28(4):765–777. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.001

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35(5):457–461. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00849.x

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 1996; 132(8):928–932.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, Gravante G, Giordano P. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg 2010; 8(1):2–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.012

- Siroy A, Wasman J. Metastatic Crohn disease: a rare cutaneous entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136(3):329–332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Selim MA. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2011; 33(6):588–593. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31820a2635

- Amankwah Y, Haefner H. Vulvar edema. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28(4):765–777. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.001

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35(5):457–461. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00849.x

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 1996; 132(8):928–932.

Vulvovaginitis: Find the cause to treat it

Although vulvovaginitis has several possible causes, the typical presenting symptoms are similar regardless of the cause: itching, burning, and vaginal discharge. Physical examination often reveals atrophy, redness, excoriations, and fissures in the vulvovaginal and perianal areas. Determining the cause is key to successful treatment.

This article reviews the diagnosis and treatment of many common and less common infectious and noninfectious causes of vulvovaginitis, the use of special tests, and the management of persistent cases.

DIAGNOSIS CAN BE CHALLENGING

Vulvar and vaginal symptoms are most commonly caused by local infections, but other causes must be also be considered, including several noninfectious ones (Table 1). Challenges in diagnosing vulvovaginitis are many and include distinguishing contact from allergic dermatitis, recognizing vaginal atrophy, and recognizing a parasitic infection. Determining whether a patient has an infectious process is important so that antibiotics can be used only when truly needed.

Foreign bodies in the vagina should also be considered, especially in children,1 as should sexual abuse. A 15-year retrospective review of prepubertal girls presenting with recurrent vaginal discharge found that sexual abuse might have been involved in about 5% of cases.2

Systemic diseases, such as eczema and psoriasis, may also present with gynecologic symptoms.

Heavy vaginal discharge may also be normal. This situation is a diagnosis of exclusion but is important to recognize in order to allay the patient’s anxiety and avoid unnecessary treatment.

SIMPLE OFFICE-BASED ASSESSMENT

A thorough history and physical examination are always warranted.

Simple tests of vaginal secretions can often determine the diagnosis (Table 2). Vaginal secretions should be analyzed in the following order:

Testing the pH. The pH can help determine likely diagnoses and streamline further testing (Figure 1).

Saline microscopy. Some of the vaginal discharge sample should be diluted with 1 or 2 drops of normal saline and examined under a microscope, first at × 10 magnification, then at × 40. The sample should be searched for epithelial cells, blood cells, “clue” cells (ie, epithelial cells with borders studded or obscured by bacteria), and motile trichomonads.

10% KOH whiff test and microscopy. To a second vaginal sample, a small amount of 10% potassium hydroxide should be added, and the examiner should sniff it. An amine or fishy odor is a sign of bacterial vaginosis.

If pH paper, KOH, and a microscope are unavailable, other point-of-care tests can be used for specific conditions as discussed below.

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Infectious causes of vulvovaginitis include bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, trichomoniasis, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common vaginal disorder worldwide. It has been linked to preterm delivery, intra-amniotic infection, endometritis, postabortion infection, and vaginal cuff cellulitis after hysterectomy.3 It may also be a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.4

The condition reflects a microbial imbalance in the vaginal ecosystem, characterized by depletion of the dominant hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli and overgrowth of anaerobic and facultative aerobic organisms such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Atopobium vaginae, and Prevotella and Mobiluncus species.

Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis

The Amsel criteria consist of the following:

- pH greater than 4.5

- Positive whiff test

- Homogeneous discharge

- Clue cells.

Three of the four criteria must be present for a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. This method is inexpensive and provides immediate results in the clinic.

The Nugent score, based on seeing certain bacteria from a vaginal swab on Gram stain microscopy, is the diagnostic standard for research.5

DNA tests. Affirm VPIII (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) is a nonamplified nucleic acid probe hybridization test that detects Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida albicans, and G vaginalis. Although it is more expensive than testing for the Amsel criteria, it is commonly used in private offices because it is simple to use, gives rapid results, and does not require a microscope.6 Insurance pays for it when the test is indicated, but we know of a patient who received a bill for approximately $500 when the insurance company thought the test was not indicated.

In a study of 109 patients with symptoms of vulvovaginitis, the Affirm VPIII was found comparable to saline microscopy when tested on residual vaginal samples. Compared with Gram stain using Nugent scoring, the test has a sensitivity of 87.7% to 95.2% and a specificity of 81% to 99.1% for bacterial vaginosis.7

In 323 symptomatic women, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for bacterial vaginosis was 96.9% sensitive and 92.6% specific for bacterial vaginosis, and Affirm VPIII was 90.1% sensitive and 67.6% specific, compared with a reference standard incorporating Nugent Gram-stain scores and Amsel criteria.8 The test is commercially available.

Management of bacterial vaginosis

Initial treatment. Bacterial vaginosis can be treated with oral or topical metronidazole, oral tinidazole, or oral or topical clindamycin.9 All options offer equivalent efficacy as initial treatments, so the choice may be based on cost and preferred route of administration.

Treatment for recurrent disease. Women who have 3 or more episodes in 12 months should receive initial treatment each time as described above and should then be offered additional suppressive therapy with 0.75% metronidazole intravaginal gel 2 times a week for 4 months. A side effect of therapy is vulvovaginal candidiasis, which should be treated as needed.

In a multicenter study, Sobel et al10 randomized patients who had recurrent bacterial vaginosis to twice-weekly metronidazole gel or placebo for 16 weeks after their initial treatment. During the 28 weeks of follow-up, recurrences occurred in 51% of treated women vs 75% of those on placebo.

Another option for chronic therapy is oral metronidazole and boric acid vaginal suppositories.

Reichman et al11 treated women with oral metronidazole or tinidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days, followed by vaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 21 days. This was followed by twice-weekly vaginal metronidazole gel for 16 weeks. At follow-up, the cure rate was 92% at 7 weeks, dropping to 88% at 12 weeks and 50% at 36 weeks.

Patients with recurrent bacterial vaginosis despite therapy should be referred to a vulvovaginal or infectious disease specialist.

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is the second most common cause of vaginitis.

Diagnosis can be clinical

Vulvovaginal candidiasis can be clinically diagnosed on the basis of cottage cheese-like clumpy discharge; external dysuria (a burning sensation when urine comes in contact with the vulva); and vulvar itching, pain, swelling, and redness. Edema, fissures, and excoriations may be seen on examination of the vulva. (Figure 3).

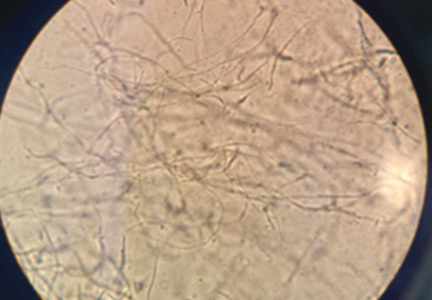

Saline microscopy (Figure 2) with the addition of 10% KOH may reveal the characteristic fungal elements, but its sensitivity is only 50%.

Fungal culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis and is needed to determine the sensitivity of specific strains of Candida to therapy.12

DNA tests can also be helpful. In a study of patients with symptomatic vaginitis, Affirm VPIII detected Candida in 11% of samples, whereas microscopy detected it in only 7%.13 Another study7 found that Affirm VPIII produced comparable results whether the sample was collected from residual vaginal discharge found on the speculum or was collected in the traditional way (by swabbing).

Cartwright et al8 compared the performance of a multiplexed, real-time PCR assay and Affirm VPIII in 102 patients. PCR was much more sensitive (97.7% vs 58.1%) but less specific (93.2% vs 100%), with culture serving as the gold standard.

Management of candidiasis

Uncomplicated cases can be managed with prescription or over-the-counter topical or oral antifungal medications for 1 to 7 days, depending on the medication.9 However, most of the common antifungals may not be effective against non-albicans Candida.

In immunosuppressed patients and diabetic patients, if symptoms do not improve with regular treatment, a vaginal sample should be cultured for C albicans. If the culture is positive, the patient should be treated with fluconazole 150 mg orally every 3 days for 3 doses.14

Patients with recurrent episodes (3 or more in 12 months) should follow initial treatment with maintenance therapy of weekly fluconazole 150 mg orally for 6 months.15

Non-albicans Candida may be azole-resistant, and fungal culture and sensitivity should be obtained. Sobel et al13 documented successful treatment of non-albicans Candida using boric acid and flucytosine. Phillips16 documented successful use of compounded amphotericin B in a 50-mg vaginal suppository for 14 days. Therefore, in patients who have Candida species other than C albicans, treatment should be one of the following:

- Vaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 14 to 21 days

- Flucytosine in 15.5% vaginal cream, intravaginally administered as 5 g for 14 days

- Amphotericin B 50 mg vaginal suppositories for 14 days.

Boric acid is readily available, but flucytosine vaginal cream and amphotericin B vaginal suppositories must usually be compounded by a pharmacist.

Of note: All that itches is not yeast. Patients with persistent itching despite treatment should be referred to a specialist to search for another cause.

TRICHOMONIASIS

The incidence of T vaginalis infection is higher than that of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis combined, with an estimated 7.4 million new cases occurring in the year 2000 in the United States.17 Infection increases the sexual transmission of HIV.18–20 It is often asymptomatic and so is likely underdiagnosed.

Diagnosis of trichomoniasis

Vaginal pH may be normal or elevated (> 4.5).

Direct microscopy. Observation by saline microscopy of motile trichomonads with their characteristic jerky movements is 100% specific but only 50% sensitive. Sensitivity is reduced by delaying microscopy on the sample by as little as 10 minutes.21

The incidental finding of T vaginalis on a conventional Papanicolaou (Pap) smear has poor sensitivity and specificity, and patients diagnosed with T vaginalis by conventional Pap smear should have a second test performed. The liquid-based Pap test is more accurate for microscopic diagnosis, and its results can be used to determine if treatment is needed (sensitivity 60%–90%; specificity 98%–100%).22,23

Culture. Amplification of T vaginalis in liquid culture usually provides results within 3 days.24 It is more sensitive than microscopy but less sensitive than a nucleic acid amplification test: compared with a nucleic acid amplification test, culture is 44% to 75% sensitive for detecting T vaginalis and 100% specific.19 Culture is the preferred test for resistant strains.

Non–culture-based or nucleic acid tests do not require viable organisms, so they allow for a wider range of specimen storage temperatures and time intervals between collection and processing. This quality limits them for testing treatment success; if performed too early, they may detect nonviable organisms. A 2-week interval is recommended between the end of treatment and retesting.25

Nonamplified tests such as Affirm VPIII and the Osom Trichomonas Test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, MA) are 40% to 95% sensitive, depending on the test and reference standard used, and 92% to 100% specific.26,27

Nucleic acid amplification tests are usually not performed as point-of-care tests. They are more expensive and require special equipment with trained personnel. Sensitivities range from 76% to 100%, making these tests more suitable for screening and testing of asymptomatic women, in whom the concentration of organisms may be lower.

Treatment of trichomoniasis

Treatment is a single 2-g oral dose of metronidazole or tinidazole.9

If initial treatment is ineffective, an additional regimen can be either of the following:

- Oral metronidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days

- Oral metronidazole or tinidazole, 2 g daily for 5 days.

Patients allergic to nitroimidazoles should be referred for desensitization.

If these treatments are unsuccessful, the patient should be referred to an infectious disease specialist or gynecologist who specializes in vulvovaginal disorders. Treatment failure is uncommon and is usually related to noncompliance, reinfection, or metronidazole resistance.28 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers testing for resistance by request.

Reportedly successful regimens for refractory trichomoniasis include 14 days of either:

- Oral tinidazole 500 mg 4 times daily plus vaginal tinidazole 500 mg twice daily29

- Oral tinidazole 1 g 3 times daily plus compounded 5% intravaginal paromomycin 5 g nightly.30

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS INFECTION

HSV (HSV-1 and HSV-2) causes lifelong infection. About 50 million people in the United States are infected with HSV-2, the most common cause of recurrent infections.31 Owing to changes in sexual practices, an increasing number of young people are acquiring anogenital HSV-1 infection.32,33

Diagnosis of herpes

Diagnosis may be difficult because the painful vesicular or ulcerative lesions (Figure 4) may not be visible at the time of presentation. Diagnosis is based on specific virologic and serologic tests. Nonspecific tests (eg, Tzanck smear, direct immunofluorescence) are neither sensitive nor specific and should not be relied on for diagnosis.34 HSV culture or HSV-PCR testing of a lesion is preferred. The sensitivity of viral culture can be low and is dependent on the stage of healing of a lesion and obtaining an adequate sample.

Accurate type-specific HSV serologic assays are based on HSV-specific glycoprotein G1 (HSV-1) and glycoprotein G2 (HSV-2). Unless a patient’s serologic status has already been determined, serologic testing should be done concurrently with HSV culture or PCR testing. Serologic testing enables classification of an infection as primary, nonprimary, or recurrent. For example, a patient with a positive HSV culture and negative serology most likely has primary HSV infection, and serologic study should be repeated after 6 to 8 weeks to assess for seroconversion.

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) testing for HSV-1 or HSV-2 is not diagnostic or type-specific and may be positive during recurrent genital or oral episodes of herpes.35

Treatment of herpes

In general, antiviral medications (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) are effective for managing HSV.12 Episodic or continuous suppression therapy may be needed for patients experiencing more than four outbreaks in 12 months. Patients who do not respond to treatment should be referred to an infectious disease specialist and undergo a viral culture with sensitivities.

NONINFECTIOUS CAUSES

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is a chronic vaginal disorder of unknown cause. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, and some patients may have a superimposed bacterial infection. It occurs mostly in perimenopausal woman and is often associated with low estrogen levels.

Diagnosis. Patients may report copious green-yellow mucoid discharge, vulvar or vaginal pain, and dyspareunia. On examination, the vulva may be erythematous, friable, and tender to the touch. The vagina may have ecchymoses, be diffusely erythematous, and have linear lesions. Mucoid or purulent discharge may be seen.

The vaginal pH is greater than 4.5.

Saline microscopy shows increased parabasal cells and leukorrhea (Figure 5).

Diagnosis is based on all of the following:

- At least 1 symptom (ie, vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, pruritus, pain, irritation, or burning)

- Vaginal inflammation on examination

- pH higher than 4.5

- Presence of parabasal cells and leukorrhea on microscopy (a ratio of leukocytes to vaginal epithelial cells > 1:1).36

Treatment involves use of 2% intravaginal clindamycin or 10% intravaginal compounded hydrocortisone cream for 4 to 6 weeks. Patients who are not cured with single-agent therapy may benefit from compounded clindamycin and hydrocortisone, with estrogen added to the formulation for hypoestrogenic patients.

Atrophic vaginitis

Atrophic vaginitis is often seen in menopausal or hypoestrogenic women. Presenting symptoms include vulvar or vaginal pain and dyspareunia.

Diagnosis. On physical examination, the vulva appears pale and atrophic, with narrowing of the introitus. Vaginal examination may reveal a pale mucosa that lacks elasticity and rugation. The examination should be performed with caution, as the vagina may bleed easily.

The vaginal pH is usually elevated.

Saline microscopy may show parabasal cells and a paucity of epithelial cells. (Figure 6).

The Vaginal Maturation Index is an indicator of the maturity of the epithelial cell types being exfoliated; these normally include parabasal (immature) cells, intermediate, and superficial (mature) cells. A predominance of immature cells indicates a hypoestrogenic state.

Infection should be considered and treated as needed.

Treatment. Patients with no contraindication may benefit from systemic hormone therapy or topical estrogen, or both.

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is classified into two types:

Irritant dermatitis, caused by the destructive action of contactants, eg, urine, feces, topical agents, feminine wipes

Allergic dermatitis, also contactant-induced, but immunologically mediated.

If a diagnosis cannot be made from the patient history and physical examination, biopsy should be performed.

Treatment of contact dermatitis involves removing the irritant, hydrating the skin with sitz baths, and using an emollient (eg, petroleum jelly) and midpotent topical steroids until resolution. Some patients benefit from topical immunosuppressive agents (eg, tacrolimus). Patients with severe symptoms may be treated with a tapering course of oral steroids for 5 to 7 days. Recalcitrant cases should be referred to a specialist.

Lichen planus

Lichen sclerosus is a benign, chronic, progressive dermatologic condition characterized by marked inflammation, epithelial thinning, and distinctive dermal changes accompanied by pruritus and pain (Figures 7 and 8).

Treatment. High-potency topical steroids are the mainstay of therapy for lichen disease. Although these are not infectious processes, superimposed infections (mostly bacterial and fungal) may also be present and should be treated.

- Van Eyk N, Allen L, Giesbrecht E, et al. Pediatric vulvovaginal disorders: a diagnostic approach and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009; 31:850–862.

- McGreal S, Wood P. Recurrent vaginal discharge in children. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013; 26:205–208.

- Livengood CH. Bacterial vaginosis: an overview for 2009. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009; 2:28–37.

- Atashili J, Poole C, Ndumbe PM, Adimora AA, Smith JS. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV acquisition: a meta-analysis of published studies. AIDS 2008; 22:1493–1501.

- Money D. The laboratory diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2005; 16:77–79.

- Lowe NK, Neal JL, Ryan-Wenger NA, et al. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis compared with a DNA probe laboratory standard. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113:89–95.

- Mulhem E, Boyanton BL Jr, Robinson-Dunn B, Ebert C, Dzebo R. Performance of the Affirm VP-III using residual vaginal discharge collected from the speculum to characterize vaginitis in symptomatic women. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2014; 18:344–346.

- Cartwright CP, Lembke BD, Ramachandran K, et al. Comparison of nucleic acid amplification assays with BD Affirm VPIII for diagnosis of vaginitis in symptomatic women. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:3694–3699.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64:1–137.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:1283–1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2009; 36:732–734.

- Carr PL, Felsenstein D, Friedman RH. Evaluation and management of vaginitis. J Gen Intern Med 1998; 13:335–346.

- Sobel JD, Chaim W, Nagappan V, Leaman D. Treatment of vaginitis caused by Candida glabrata: use of topical boric acid and flucytosine. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189:1297–1300.

- Sobel JD, Kapernick PS, Zervos M, et al. Treatment of complicated Candida vaginitis: comparison of single and sequential doses of fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 185:363–369.

- Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:876–883.

- Phillips AJ. Treatment of non-albicans Candida vaginitis with amphotericin B vaginal suppositories. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192:2009–2013.

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2004; 36:6–10.

- Gatski M, Martin DH, Clark RA, Harville E, Schmidt N, Kissinger P. Co-occurrence of Trichomonas vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis among HIV-positive women. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:163–166.

- Hobbs MM, Seña AC. Modern diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89:434–438.

- McClelland RS, Sangare L, Hassan WM, et al. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:698–702.

- Kingston MA, Bansal D, Carlin EM. ‘Shelf life’ of Trichomonas vaginalis. Int J STD AIDS 2003; 14:28–29.

- Aslan DL, Gulbahce HE, Stelow EB, et al. The diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis in liquid-based Pap tests: correlation with PCR. Diagn Cytopathol 2005; 32:341–344.

- Lara-Torre E, Pinkerton JS. Accuracy of detection of Trichomonas vaginalis organisms on a liquid-based papanicolaou smear. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 188:354–356.

- Hobbs MM, Lapple DM, Lawing LF, et al. Methods for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in the male partners of infected women: implications for control of trichomoniasis. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:3994–3999.

- Van Der Pol B, Williams JA, Orr DP, Batteiger BE, Fortenberry JD. Prevalence, incidence, natural history, and response to treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among adolescent women. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:2039–2044.

- Campbell L, Woods V, Lloyd T, Elsayed S, Church DL. Evaluation of the OSOM Trichomonas rapid test versus wet preparation examination for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis vaginitis in specimens from women with a low prevalence of infection. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:3467–3469.

- Chapin K, Andrea S. APTIMA Trichomonas vaginalis, a transcription-mediated amplification assay for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in urogenital specimens. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2011; 11:679–688.

- Krashin JW, Koumans EH, Bradshaw-Sydnor AC, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis prevalence, incidence, risk factors and antibiotic-resistance in an adolescent population. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37:440–444.

- Sobel JD, Nyirjesy P, Brown W. Tinidazole therapy for metronidazole-resistant vaginal trichomoniasis. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:1341–1346.

- Nyirjesy P, Gilbert J, Mulcahy LJ. Resistant trichomoniasis: successful treatment with combination therapy. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:962–963.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, McQuillan GM. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2—United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:325–333.

- Roberts CM, Pfister JR, Spear SJ. Increasing proportion of herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes infection in college students. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30:797–800.

- Ryder N, Jin F, McNulty AM, Grulich AE, Donovan B. Increasing role of herpes simplex virus type 1 in first-episode anogenital herpes in heterosexual women and younger men who have sex with men, 1992-2006. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:416–419.

- Caviness AC, Oelze LL, Saz UE, Greer JM, Demmler-Harrison GJ. Direct immunofluorescence assay compared to cell culture for the diagnosis of mucocutaneous herpes simplex virus infections in children. J Clin Virol 2010; 49:58–60.

- Morrow R, Friedrich D. Performance of a novel test for IgM and IgG antibodies in subjects with culture-documented genital herpes simplex virus-1 or -2 infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006; 12:463–469.

- Bradford J, Fischer G. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: differential diagnosis and alternate diagnostic criteria. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2010; 14:306–310.

Although vulvovaginitis has several possible causes, the typical presenting symptoms are similar regardless of the cause: itching, burning, and vaginal discharge. Physical examination often reveals atrophy, redness, excoriations, and fissures in the vulvovaginal and perianal areas. Determining the cause is key to successful treatment.

This article reviews the diagnosis and treatment of many common and less common infectious and noninfectious causes of vulvovaginitis, the use of special tests, and the management of persistent cases.

DIAGNOSIS CAN BE CHALLENGING

Vulvar and vaginal symptoms are most commonly caused by local infections, but other causes must be also be considered, including several noninfectious ones (Table 1). Challenges in diagnosing vulvovaginitis are many and include distinguishing contact from allergic dermatitis, recognizing vaginal atrophy, and recognizing a parasitic infection. Determining whether a patient has an infectious process is important so that antibiotics can be used only when truly needed.

Foreign bodies in the vagina should also be considered, especially in children,1 as should sexual abuse. A 15-year retrospective review of prepubertal girls presenting with recurrent vaginal discharge found that sexual abuse might have been involved in about 5% of cases.2

Systemic diseases, such as eczema and psoriasis, may also present with gynecologic symptoms.

Heavy vaginal discharge may also be normal. This situation is a diagnosis of exclusion but is important to recognize in order to allay the patient’s anxiety and avoid unnecessary treatment.

SIMPLE OFFICE-BASED ASSESSMENT

A thorough history and physical examination are always warranted.

Simple tests of vaginal secretions can often determine the diagnosis (Table 2). Vaginal secretions should be analyzed in the following order:

Testing the pH. The pH can help determine likely diagnoses and streamline further testing (Figure 1).

Saline microscopy. Some of the vaginal discharge sample should be diluted with 1 or 2 drops of normal saline and examined under a microscope, first at × 10 magnification, then at × 40. The sample should be searched for epithelial cells, blood cells, “clue” cells (ie, epithelial cells with borders studded or obscured by bacteria), and motile trichomonads.

10% KOH whiff test and microscopy. To a second vaginal sample, a small amount of 10% potassium hydroxide should be added, and the examiner should sniff it. An amine or fishy odor is a sign of bacterial vaginosis.

If pH paper, KOH, and a microscope are unavailable, other point-of-care tests can be used for specific conditions as discussed below.

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Infectious causes of vulvovaginitis include bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, trichomoniasis, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common vaginal disorder worldwide. It has been linked to preterm delivery, intra-amniotic infection, endometritis, postabortion infection, and vaginal cuff cellulitis after hysterectomy.3 It may also be a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.4

The condition reflects a microbial imbalance in the vaginal ecosystem, characterized by depletion of the dominant hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli and overgrowth of anaerobic and facultative aerobic organisms such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Atopobium vaginae, and Prevotella and Mobiluncus species.

Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis

The Amsel criteria consist of the following:

- pH greater than 4.5

- Positive whiff test

- Homogeneous discharge

- Clue cells.

Three of the four criteria must be present for a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. This method is inexpensive and provides immediate results in the clinic.

The Nugent score, based on seeing certain bacteria from a vaginal swab on Gram stain microscopy, is the diagnostic standard for research.5

DNA tests. Affirm VPIII (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) is a nonamplified nucleic acid probe hybridization test that detects Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida albicans, and G vaginalis. Although it is more expensive than testing for the Amsel criteria, it is commonly used in private offices because it is simple to use, gives rapid results, and does not require a microscope.6 Insurance pays for it when the test is indicated, but we know of a patient who received a bill for approximately $500 when the insurance company thought the test was not indicated.

In a study of 109 patients with symptoms of vulvovaginitis, the Affirm VPIII was found comparable to saline microscopy when tested on residual vaginal samples. Compared with Gram stain using Nugent scoring, the test has a sensitivity of 87.7% to 95.2% and a specificity of 81% to 99.1% for bacterial vaginosis.7

In 323 symptomatic women, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for bacterial vaginosis was 96.9% sensitive and 92.6% specific for bacterial vaginosis, and Affirm VPIII was 90.1% sensitive and 67.6% specific, compared with a reference standard incorporating Nugent Gram-stain scores and Amsel criteria.8 The test is commercially available.

Management of bacterial vaginosis

Initial treatment. Bacterial vaginosis can be treated with oral or topical metronidazole, oral tinidazole, or oral or topical clindamycin.9 All options offer equivalent efficacy as initial treatments, so the choice may be based on cost and preferred route of administration.

Treatment for recurrent disease. Women who have 3 or more episodes in 12 months should receive initial treatment each time as described above and should then be offered additional suppressive therapy with 0.75% metronidazole intravaginal gel 2 times a week for 4 months. A side effect of therapy is vulvovaginal candidiasis, which should be treated as needed.

In a multicenter study, Sobel et al10 randomized patients who had recurrent bacterial vaginosis to twice-weekly metronidazole gel or placebo for 16 weeks after their initial treatment. During the 28 weeks of follow-up, recurrences occurred in 51% of treated women vs 75% of those on placebo.

Another option for chronic therapy is oral metronidazole and boric acid vaginal suppositories.

Reichman et al11 treated women with oral metronidazole or tinidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days, followed by vaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 21 days. This was followed by twice-weekly vaginal metronidazole gel for 16 weeks. At follow-up, the cure rate was 92% at 7 weeks, dropping to 88% at 12 weeks and 50% at 36 weeks.

Patients with recurrent bacterial vaginosis despite therapy should be referred to a vulvovaginal or infectious disease specialist.

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is the second most common cause of vaginitis.

Diagnosis can be clinical

Vulvovaginal candidiasis can be clinically diagnosed on the basis of cottage cheese-like clumpy discharge; external dysuria (a burning sensation when urine comes in contact with the vulva); and vulvar itching, pain, swelling, and redness. Edema, fissures, and excoriations may be seen on examination of the vulva. (Figure 3).

Saline microscopy (Figure 2) with the addition of 10% KOH may reveal the characteristic fungal elements, but its sensitivity is only 50%.

Fungal culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis and is needed to determine the sensitivity of specific strains of Candida to therapy.12

DNA tests can also be helpful. In a study of patients with symptomatic vaginitis, Affirm VPIII detected Candida in 11% of samples, whereas microscopy detected it in only 7%.13 Another study7 found that Affirm VPIII produced comparable results whether the sample was collected from residual vaginal discharge found on the speculum or was collected in the traditional way (by swabbing).

Cartwright et al8 compared the performance of a multiplexed, real-time PCR assay and Affirm VPIII in 102 patients. PCR was much more sensitive (97.7% vs 58.1%) but less specific (93.2% vs 100%), with culture serving as the gold standard.

Management of candidiasis

Uncomplicated cases can be managed with prescription or over-the-counter topical or oral antifungal medications for 1 to 7 days, depending on the medication.9 However, most of the common antifungals may not be effective against non-albicans Candida.

In immunosuppressed patients and diabetic patients, if symptoms do not improve with regular treatment, a vaginal sample should be cultured for C albicans. If the culture is positive, the patient should be treated with fluconazole 150 mg orally every 3 days for 3 doses.14

Patients with recurrent episodes (3 or more in 12 months) should follow initial treatment with maintenance therapy of weekly fluconazole 150 mg orally for 6 months.15

Non-albicans Candida may be azole-resistant, and fungal culture and sensitivity should be obtained. Sobel et al13 documented successful treatment of non-albicans Candida using boric acid and flucytosine. Phillips16 documented successful use of compounded amphotericin B in a 50-mg vaginal suppository for 14 days. Therefore, in patients who have Candida species other than C albicans, treatment should be one of the following:

- Vaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 14 to 21 days

- Flucytosine in 15.5% vaginal cream, intravaginally administered as 5 g for 14 days

- Amphotericin B 50 mg vaginal suppositories for 14 days.

Boric acid is readily available, but flucytosine vaginal cream and amphotericin B vaginal suppositories must usually be compounded by a pharmacist.

Of note: All that itches is not yeast. Patients with persistent itching despite treatment should be referred to a specialist to search for another cause.

TRICHOMONIASIS

The incidence of T vaginalis infection is higher than that of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis combined, with an estimated 7.4 million new cases occurring in the year 2000 in the United States.17 Infection increases the sexual transmission of HIV.18–20 It is often asymptomatic and so is likely underdiagnosed.

Diagnosis of trichomoniasis

Vaginal pH may be normal or elevated (> 4.5).

Direct microscopy. Observation by saline microscopy of motile trichomonads with their characteristic jerky movements is 100% specific but only 50% sensitive. Sensitivity is reduced by delaying microscopy on the sample by as little as 10 minutes.21

The incidental finding of T vaginalis on a conventional Papanicolaou (Pap) smear has poor sensitivity and specificity, and patients diagnosed with T vaginalis by conventional Pap smear should have a second test performed. The liquid-based Pap test is more accurate for microscopic diagnosis, and its results can be used to determine if treatment is needed (sensitivity 60%–90%; specificity 98%–100%).22,23

Culture. Amplification of T vaginalis in liquid culture usually provides results within 3 days.24 It is more sensitive than microscopy but less sensitive than a nucleic acid amplification test: compared with a nucleic acid amplification test, culture is 44% to 75% sensitive for detecting T vaginalis and 100% specific.19 Culture is the preferred test for resistant strains.

Non–culture-based or nucleic acid tests do not require viable organisms, so they allow for a wider range of specimen storage temperatures and time intervals between collection and processing. This quality limits them for testing treatment success; if performed too early, they may detect nonviable organisms. A 2-week interval is recommended between the end of treatment and retesting.25

Nonamplified tests such as Affirm VPIII and the Osom Trichomonas Test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, MA) are 40% to 95% sensitive, depending on the test and reference standard used, and 92% to 100% specific.26,27

Nucleic acid amplification tests are usually not performed as point-of-care tests. They are more expensive and require special equipment with trained personnel. Sensitivities range from 76% to 100%, making these tests more suitable for screening and testing of asymptomatic women, in whom the concentration of organisms may be lower.

Treatment of trichomoniasis

Treatment is a single 2-g oral dose of metronidazole or tinidazole.9

If initial treatment is ineffective, an additional regimen can be either of the following:

- Oral metronidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days

- Oral metronidazole or tinidazole, 2 g daily for 5 days.

Patients allergic to nitroimidazoles should be referred for desensitization.

If these treatments are unsuccessful, the patient should be referred to an infectious disease specialist or gynecologist who specializes in vulvovaginal disorders. Treatment failure is uncommon and is usually related to noncompliance, reinfection, or metronidazole resistance.28 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers testing for resistance by request.

Reportedly successful regimens for refractory trichomoniasis include 14 days of either:

- Oral tinidazole 500 mg 4 times daily plus vaginal tinidazole 500 mg twice daily29

- Oral tinidazole 1 g 3 times daily plus compounded 5% intravaginal paromomycin 5 g nightly.30

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS INFECTION

HSV (HSV-1 and HSV-2) causes lifelong infection. About 50 million people in the United States are infected with HSV-2, the most common cause of recurrent infections.31 Owing to changes in sexual practices, an increasing number of young people are acquiring anogenital HSV-1 infection.32,33

Diagnosis of herpes

Diagnosis may be difficult because the painful vesicular or ulcerative lesions (Figure 4) may not be visible at the time of presentation. Diagnosis is based on specific virologic and serologic tests. Nonspecific tests (eg, Tzanck smear, direct immunofluorescence) are neither sensitive nor specific and should not be relied on for diagnosis.34 HSV culture or HSV-PCR testing of a lesion is preferred. The sensitivity of viral culture can be low and is dependent on the stage of healing of a lesion and obtaining an adequate sample.

Accurate type-specific HSV serologic assays are based on HSV-specific glycoprotein G1 (HSV-1) and glycoprotein G2 (HSV-2). Unless a patient’s serologic status has already been determined, serologic testing should be done concurrently with HSV culture or PCR testing. Serologic testing enables classification of an infection as primary, nonprimary, or recurrent. For example, a patient with a positive HSV culture and negative serology most likely has primary HSV infection, and serologic study should be repeated after 6 to 8 weeks to assess for seroconversion.

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) testing for HSV-1 or HSV-2 is not diagnostic or type-specific and may be positive during recurrent genital or oral episodes of herpes.35

Treatment of herpes

In general, antiviral medications (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) are effective for managing HSV.12 Episodic or continuous suppression therapy may be needed for patients experiencing more than four outbreaks in 12 months. Patients who do not respond to treatment should be referred to an infectious disease specialist and undergo a viral culture with sensitivities.

NONINFECTIOUS CAUSES

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is a chronic vaginal disorder of unknown cause. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, and some patients may have a superimposed bacterial infection. It occurs mostly in perimenopausal woman and is often associated with low estrogen levels.

Diagnosis. Patients may report copious green-yellow mucoid discharge, vulvar or vaginal pain, and dyspareunia. On examination, the vulva may be erythematous, friable, and tender to the touch. The vagina may have ecchymoses, be diffusely erythematous, and have linear lesions. Mucoid or purulent discharge may be seen.

The vaginal pH is greater than 4.5.

Saline microscopy shows increased parabasal cells and leukorrhea (Figure 5).

Diagnosis is based on all of the following:

- At least 1 symptom (ie, vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, pruritus, pain, irritation, or burning)

- Vaginal inflammation on examination

- pH higher than 4.5

- Presence of parabasal cells and leukorrhea on microscopy (a ratio of leukocytes to vaginal epithelial cells > 1:1).36

Treatment involves use of 2% intravaginal clindamycin or 10% intravaginal compounded hydrocortisone cream for 4 to 6 weeks. Patients who are not cured with single-agent therapy may benefit from compounded clindamycin and hydrocortisone, with estrogen added to the formulation for hypoestrogenic patients.

Atrophic vaginitis

Atrophic vaginitis is often seen in menopausal or hypoestrogenic women. Presenting symptoms include vulvar or vaginal pain and dyspareunia.

Diagnosis. On physical examination, the vulva appears pale and atrophic, with narrowing of the introitus. Vaginal examination may reveal a pale mucosa that lacks elasticity and rugation. The examination should be performed with caution, as the vagina may bleed easily.

The vaginal pH is usually elevated.

Saline microscopy may show parabasal cells and a paucity of epithelial cells. (Figure 6).

The Vaginal Maturation Index is an indicator of the maturity of the epithelial cell types being exfoliated; these normally include parabasal (immature) cells, intermediate, and superficial (mature) cells. A predominance of immature cells indicates a hypoestrogenic state.

Infection should be considered and treated as needed.

Treatment. Patients with no contraindication may benefit from systemic hormone therapy or topical estrogen, or both.

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is classified into two types:

Irritant dermatitis, caused by the destructive action of contactants, eg, urine, feces, topical agents, feminine wipes

Allergic dermatitis, also contactant-induced, but immunologically mediated.

If a diagnosis cannot be made from the patient history and physical examination, biopsy should be performed.

Treatment of contact dermatitis involves removing the irritant, hydrating the skin with sitz baths, and using an emollient (eg, petroleum jelly) and midpotent topical steroids until resolution. Some patients benefit from topical immunosuppressive agents (eg, tacrolimus). Patients with severe symptoms may be treated with a tapering course of oral steroids for 5 to 7 days. Recalcitrant cases should be referred to a specialist.

Lichen planus

Lichen sclerosus is a benign, chronic, progressive dermatologic condition characterized by marked inflammation, epithelial thinning, and distinctive dermal changes accompanied by pruritus and pain (Figures 7 and 8).

Treatment. High-potency topical steroids are the mainstay of therapy for lichen disease. Although these are not infectious processes, superimposed infections (mostly bacterial and fungal) may also be present and should be treated.

Although vulvovaginitis has several possible causes, the typical presenting symptoms are similar regardless of the cause: itching, burning, and vaginal discharge. Physical examination often reveals atrophy, redness, excoriations, and fissures in the vulvovaginal and perianal areas. Determining the cause is key to successful treatment.

This article reviews the diagnosis and treatment of many common and less common infectious and noninfectious causes of vulvovaginitis, the use of special tests, and the management of persistent cases.

DIAGNOSIS CAN BE CHALLENGING

Vulvar and vaginal symptoms are most commonly caused by local infections, but other causes must be also be considered, including several noninfectious ones (Table 1). Challenges in diagnosing vulvovaginitis are many and include distinguishing contact from allergic dermatitis, recognizing vaginal atrophy, and recognizing a parasitic infection. Determining whether a patient has an infectious process is important so that antibiotics can be used only when truly needed.

Foreign bodies in the vagina should also be considered, especially in children,1 as should sexual abuse. A 15-year retrospective review of prepubertal girls presenting with recurrent vaginal discharge found that sexual abuse might have been involved in about 5% of cases.2

Systemic diseases, such as eczema and psoriasis, may also present with gynecologic symptoms.

Heavy vaginal discharge may also be normal. This situation is a diagnosis of exclusion but is important to recognize in order to allay the patient’s anxiety and avoid unnecessary treatment.

SIMPLE OFFICE-BASED ASSESSMENT

A thorough history and physical examination are always warranted.

Simple tests of vaginal secretions can often determine the diagnosis (Table 2). Vaginal secretions should be analyzed in the following order:

Testing the pH. The pH can help determine likely diagnoses and streamline further testing (Figure 1).

Saline microscopy. Some of the vaginal discharge sample should be diluted with 1 or 2 drops of normal saline and examined under a microscope, first at × 10 magnification, then at × 40. The sample should be searched for epithelial cells, blood cells, “clue” cells (ie, epithelial cells with borders studded or obscured by bacteria), and motile trichomonads.

10% KOH whiff test and microscopy. To a second vaginal sample, a small amount of 10% potassium hydroxide should be added, and the examiner should sniff it. An amine or fishy odor is a sign of bacterial vaginosis.

If pH paper, KOH, and a microscope are unavailable, other point-of-care tests can be used for specific conditions as discussed below.

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Infectious causes of vulvovaginitis include bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, trichomoniasis, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common vaginal disorder worldwide. It has been linked to preterm delivery, intra-amniotic infection, endometritis, postabortion infection, and vaginal cuff cellulitis after hysterectomy.3 It may also be a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.4

The condition reflects a microbial imbalance in the vaginal ecosystem, characterized by depletion of the dominant hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli and overgrowth of anaerobic and facultative aerobic organisms such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Atopobium vaginae, and Prevotella and Mobiluncus species.

Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis

The Amsel criteria consist of the following:

- pH greater than 4.5

- Positive whiff test

- Homogeneous discharge

- Clue cells.

Three of the four criteria must be present for a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. This method is inexpensive and provides immediate results in the clinic.

The Nugent score, based on seeing certain bacteria from a vaginal swab on Gram stain microscopy, is the diagnostic standard for research.5

DNA tests. Affirm VPIII (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) is a nonamplified nucleic acid probe hybridization test that detects Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida albicans, and G vaginalis. Although it is more expensive than testing for the Amsel criteria, it is commonly used in private offices because it is simple to use, gives rapid results, and does not require a microscope.6 Insurance pays for it when the test is indicated, but we know of a patient who received a bill for approximately $500 when the insurance company thought the test was not indicated.

In a study of 109 patients with symptoms of vulvovaginitis, the Affirm VPIII was found comparable to saline microscopy when tested on residual vaginal samples. Compared with Gram stain using Nugent scoring, the test has a sensitivity of 87.7% to 95.2% and a specificity of 81% to 99.1% for bacterial vaginosis.7

In 323 symptomatic women, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for bacterial vaginosis was 96.9% sensitive and 92.6% specific for bacterial vaginosis, and Affirm VPIII was 90.1% sensitive and 67.6% specific, compared with a reference standard incorporating Nugent Gram-stain scores and Amsel criteria.8 The test is commercially available.

Management of bacterial vaginosis

Initial treatment. Bacterial vaginosis can be treated with oral or topical metronidazole, oral tinidazole, or oral or topical clindamycin.9 All options offer equivalent efficacy as initial treatments, so the choice may be based on cost and preferred route of administration.

Treatment for recurrent disease. Women who have 3 or more episodes in 12 months should receive initial treatment each time as described above and should then be offered additional suppressive therapy with 0.75% metronidazole intravaginal gel 2 times a week for 4 months. A side effect of therapy is vulvovaginal candidiasis, which should be treated as needed.

In a multicenter study, Sobel et al10 randomized patients who had recurrent bacterial vaginosis to twice-weekly metronidazole gel or placebo for 16 weeks after their initial treatment. During the 28 weeks of follow-up, recurrences occurred in 51% of treated women vs 75% of those on placebo.

Another option for chronic therapy is oral metronidazole and boric acid vaginal suppositories.

Reichman et al11 treated women with oral metronidazole or tinidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days, followed by vaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 21 days. This was followed by twice-weekly vaginal metronidazole gel for 16 weeks. At follow-up, the cure rate was 92% at 7 weeks, dropping to 88% at 12 weeks and 50% at 36 weeks.

Patients with recurrent bacterial vaginosis despite therapy should be referred to a vulvovaginal or infectious disease specialist.

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is the second most common cause of vaginitis.

Diagnosis can be clinical

Vulvovaginal candidiasis can be clinically diagnosed on the basis of cottage cheese-like clumpy discharge; external dysuria (a burning sensation when urine comes in contact with the vulva); and vulvar itching, pain, swelling, and redness. Edema, fissures, and excoriations may be seen on examination of the vulva. (Figure 3).

Saline microscopy (Figure 2) with the addition of 10% KOH may reveal the characteristic fungal elements, but its sensitivity is only 50%.

Fungal culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis and is needed to determine the sensitivity of specific strains of Candida to therapy.12

DNA tests can also be helpful. In a study of patients with symptomatic vaginitis, Affirm VPIII detected Candida in 11% of samples, whereas microscopy detected it in only 7%.13 Another study7 found that Affirm VPIII produced comparable results whether the sample was collected from residual vaginal discharge found on the speculum or was collected in the traditional way (by swabbing).

Cartwright et al8 compared the performance of a multiplexed, real-time PCR assay and Affirm VPIII in 102 patients. PCR was much more sensitive (97.7% vs 58.1%) but less specific (93.2% vs 100%), with culture serving as the gold standard.

Management of candidiasis

Uncomplicated cases can be managed with prescription or over-the-counter topical or oral antifungal medications for 1 to 7 days, depending on the medication.9 However, most of the common antifungals may not be effective against non-albicans Candida.

In immunosuppressed patients and diabetic patients, if symptoms do not improve with regular treatment, a vaginal sample should be cultured for C albicans. If the culture is positive, the patient should be treated with fluconazole 150 mg orally every 3 days for 3 doses.14

Patients with recurrent episodes (3 or more in 12 months) should follow initial treatment with maintenance therapy of weekly fluconazole 150 mg orally for 6 months.15

Non-albicans Candida may be azole-resistant, and fungal culture and sensitivity should be obtained. Sobel et al13 documented successful treatment of non-albicans Candida using boric acid and flucytosine. Phillips16 documented successful use of compounded amphotericin B in a 50-mg vaginal suppository for 14 days. Therefore, in patients who have Candida species other than C albicans, treatment should be one of the following:

- Vaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 14 to 21 days

- Flucytosine in 15.5% vaginal cream, intravaginally administered as 5 g for 14 days

- Amphotericin B 50 mg vaginal suppositories for 14 days.

Boric acid is readily available, but flucytosine vaginal cream and amphotericin B vaginal suppositories must usually be compounded by a pharmacist.

Of note: All that itches is not yeast. Patients with persistent itching despite treatment should be referred to a specialist to search for another cause.

TRICHOMONIASIS

The incidence of T vaginalis infection is higher than that of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis combined, with an estimated 7.4 million new cases occurring in the year 2000 in the United States.17 Infection increases the sexual transmission of HIV.18–20 It is often asymptomatic and so is likely underdiagnosed.

Diagnosis of trichomoniasis

Vaginal pH may be normal or elevated (> 4.5).

Direct microscopy. Observation by saline microscopy of motile trichomonads with their characteristic jerky movements is 100% specific but only 50% sensitive. Sensitivity is reduced by delaying microscopy on the sample by as little as 10 minutes.21

The incidental finding of T vaginalis on a conventional Papanicolaou (Pap) smear has poor sensitivity and specificity, and patients diagnosed with T vaginalis by conventional Pap smear should have a second test performed. The liquid-based Pap test is more accurate for microscopic diagnosis, and its results can be used to determine if treatment is needed (sensitivity 60%–90%; specificity 98%–100%).22,23

Culture. Amplification of T vaginalis in liquid culture usually provides results within 3 days.24 It is more sensitive than microscopy but less sensitive than a nucleic acid amplification test: compared with a nucleic acid amplification test, culture is 44% to 75% sensitive for detecting T vaginalis and 100% specific.19 Culture is the preferred test for resistant strains.

Non–culture-based or nucleic acid tests do not require viable organisms, so they allow for a wider range of specimen storage temperatures and time intervals between collection and processing. This quality limits them for testing treatment success; if performed too early, they may detect nonviable organisms. A 2-week interval is recommended between the end of treatment and retesting.25

Nonamplified tests such as Affirm VPIII and the Osom Trichomonas Test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, MA) are 40% to 95% sensitive, depending on the test and reference standard used, and 92% to 100% specific.26,27

Nucleic acid amplification tests are usually not performed as point-of-care tests. They are more expensive and require special equipment with trained personnel. Sensitivities range from 76% to 100%, making these tests more suitable for screening and testing of asymptomatic women, in whom the concentration of organisms may be lower.

Treatment of trichomoniasis

Treatment is a single 2-g oral dose of metronidazole or tinidazole.9

If initial treatment is ineffective, an additional regimen can be either of the following:

- Oral metronidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days

- Oral metronidazole or tinidazole, 2 g daily for 5 days.

Patients allergic to nitroimidazoles should be referred for desensitization.

If these treatments are unsuccessful, the patient should be referred to an infectious disease specialist or gynecologist who specializes in vulvovaginal disorders. Treatment failure is uncommon and is usually related to noncompliance, reinfection, or metronidazole resistance.28 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers testing for resistance by request.

Reportedly successful regimens for refractory trichomoniasis include 14 days of either:

- Oral tinidazole 500 mg 4 times daily plus vaginal tinidazole 500 mg twice daily29

- Oral tinidazole 1 g 3 times daily plus compounded 5% intravaginal paromomycin 5 g nightly.30

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS INFECTION

HSV (HSV-1 and HSV-2) causes lifelong infection. About 50 million people in the United States are infected with HSV-2, the most common cause of recurrent infections.31 Owing to changes in sexual practices, an increasing number of young people are acquiring anogenital HSV-1 infection.32,33

Diagnosis of herpes

Diagnosis may be difficult because the painful vesicular or ulcerative lesions (Figure 4) may not be visible at the time of presentation. Diagnosis is based on specific virologic and serologic tests. Nonspecific tests (eg, Tzanck smear, direct immunofluorescence) are neither sensitive nor specific and should not be relied on for diagnosis.34 HSV culture or HSV-PCR testing of a lesion is preferred. The sensitivity of viral culture can be low and is dependent on the stage of healing of a lesion and obtaining an adequate sample.

Accurate type-specific HSV serologic assays are based on HSV-specific glycoprotein G1 (HSV-1) and glycoprotein G2 (HSV-2). Unless a patient’s serologic status has already been determined, serologic testing should be done concurrently with HSV culture or PCR testing. Serologic testing enables classification of an infection as primary, nonprimary, or recurrent. For example, a patient with a positive HSV culture and negative serology most likely has primary HSV infection, and serologic study should be repeated after 6 to 8 weeks to assess for seroconversion.

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) testing for HSV-1 or HSV-2 is not diagnostic or type-specific and may be positive during recurrent genital or oral episodes of herpes.35

Treatment of herpes

In general, antiviral medications (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) are effective for managing HSV.12 Episodic or continuous suppression therapy may be needed for patients experiencing more than four outbreaks in 12 months. Patients who do not respond to treatment should be referred to an infectious disease specialist and undergo a viral culture with sensitivities.

NONINFECTIOUS CAUSES

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is a chronic vaginal disorder of unknown cause. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, and some patients may have a superimposed bacterial infection. It occurs mostly in perimenopausal woman and is often associated with low estrogen levels.

Diagnosis. Patients may report copious green-yellow mucoid discharge, vulvar or vaginal pain, and dyspareunia. On examination, the vulva may be erythematous, friable, and tender to the touch. The vagina may have ecchymoses, be diffusely erythematous, and have linear lesions. Mucoid or purulent discharge may be seen.

The vaginal pH is greater than 4.5.

Saline microscopy shows increased parabasal cells and leukorrhea (Figure 5).

Diagnosis is based on all of the following:

- At least 1 symptom (ie, vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, pruritus, pain, irritation, or burning)

- Vaginal inflammation on examination

- pH higher than 4.5

- Presence of parabasal cells and leukorrhea on microscopy (a ratio of leukocytes to vaginal epithelial cells > 1:1).36

Treatment involves use of 2% intravaginal clindamycin or 10% intravaginal compounded hydrocortisone cream for 4 to 6 weeks. Patients who are not cured with single-agent therapy may benefit from compounded clindamycin and hydrocortisone, with estrogen added to the formulation for hypoestrogenic patients.

Atrophic vaginitis

Atrophic vaginitis is often seen in menopausal or hypoestrogenic women. Presenting symptoms include vulvar or vaginal pain and dyspareunia.

Diagnosis. On physical examination, the vulva appears pale and atrophic, with narrowing of the introitus. Vaginal examination may reveal a pale mucosa that lacks elasticity and rugation. The examination should be performed with caution, as the vagina may bleed easily.

The vaginal pH is usually elevated.

Saline microscopy may show parabasal cells and a paucity of epithelial cells. (Figure 6).

The Vaginal Maturation Index is an indicator of the maturity of the epithelial cell types being exfoliated; these normally include parabasal (immature) cells, intermediate, and superficial (mature) cells. A predominance of immature cells indicates a hypoestrogenic state.

Infection should be considered and treated as needed.

Treatment. Patients with no contraindication may benefit from systemic hormone therapy or topical estrogen, or both.

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is classified into two types:

Irritant dermatitis, caused by the destructive action of contactants, eg, urine, feces, topical agents, feminine wipes

Allergic dermatitis, also contactant-induced, but immunologically mediated.

If a diagnosis cannot be made from the patient history and physical examination, biopsy should be performed.

Treatment of contact dermatitis involves removing the irritant, hydrating the skin with sitz baths, and using an emollient (eg, petroleum jelly) and midpotent topical steroids until resolution. Some patients benefit from topical immunosuppressive agents (eg, tacrolimus). Patients with severe symptoms may be treated with a tapering course of oral steroids for 5 to 7 days. Recalcitrant cases should be referred to a specialist.

Lichen planus

Lichen sclerosus is a benign, chronic, progressive dermatologic condition characterized by marked inflammation, epithelial thinning, and distinctive dermal changes accompanied by pruritus and pain (Figures 7 and 8).

Treatment. High-potency topical steroids are the mainstay of therapy for lichen disease. Although these are not infectious processes, superimposed infections (mostly bacterial and fungal) may also be present and should be treated.

- Van Eyk N, Allen L, Giesbrecht E, et al. Pediatric vulvovaginal disorders: a diagnostic approach and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009; 31:850–862.

- McGreal S, Wood P. Recurrent vaginal discharge in children. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013; 26:205–208.

- Livengood CH. Bacterial vaginosis: an overview for 2009. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009; 2:28–37.

- Atashili J, Poole C, Ndumbe PM, Adimora AA, Smith JS. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV acquisition: a meta-analysis of published studies. AIDS 2008; 22:1493–1501.

- Money D. The laboratory diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2005; 16:77–79.

- Lowe NK, Neal JL, Ryan-Wenger NA, et al. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis compared with a DNA probe laboratory standard. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113:89–95.

- Mulhem E, Boyanton BL Jr, Robinson-Dunn B, Ebert C, Dzebo R. Performance of the Affirm VP-III using residual vaginal discharge collected from the speculum to characterize vaginitis in symptomatic women. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2014; 18:344–346.

- Cartwright CP, Lembke BD, Ramachandran K, et al. Comparison of nucleic acid amplification assays with BD Affirm VPIII for diagnosis of vaginitis in symptomatic women. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:3694–3699.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64:1–137.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:1283–1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2009; 36:732–734.

- Carr PL, Felsenstein D, Friedman RH. Evaluation and management of vaginitis. J Gen Intern Med 1998; 13:335–346.

- Sobel JD, Chaim W, Nagappan V, Leaman D. Treatment of vaginitis caused by Candida glabrata: use of topical boric acid and flucytosine. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189:1297–1300.

- Sobel JD, Kapernick PS, Zervos M, et al. Treatment of complicated Candida vaginitis: comparison of single and sequential doses of fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 185:363–369.

- Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:876–883.

- Phillips AJ. Treatment of non-albicans Candida vaginitis with amphotericin B vaginal suppositories. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192:2009–2013.

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2004; 36:6–10.

- Gatski M, Martin DH, Clark RA, Harville E, Schmidt N, Kissinger P. Co-occurrence of Trichomonas vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis among HIV-positive women. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:163–166.

- Hobbs MM, Seña AC. Modern diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89:434–438.

- McClelland RS, Sangare L, Hassan WM, et al. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:698–702.

- Kingston MA, Bansal D, Carlin EM. ‘Shelf life’ of Trichomonas vaginalis. Int J STD AIDS 2003; 14:28–29.

- Aslan DL, Gulbahce HE, Stelow EB, et al. The diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis in liquid-based Pap tests: correlation with PCR. Diagn Cytopathol 2005; 32:341–344.

- Lara-Torre E, Pinkerton JS. Accuracy of detection of Trichomonas vaginalis organisms on a liquid-based papanicolaou smear. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 188:354–356.

- Hobbs MM, Lapple DM, Lawing LF, et al. Methods for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in the male partners of infected women: implications for control of trichomoniasis. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:3994–3999.

- Van Der Pol B, Williams JA, Orr DP, Batteiger BE, Fortenberry JD. Prevalence, incidence, natural history, and response to treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among adolescent women. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:2039–2044.

- Campbell L, Woods V, Lloyd T, Elsayed S, Church DL. Evaluation of the OSOM Trichomonas rapid test versus wet preparation examination for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis vaginitis in specimens from women with a low prevalence of infection. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:3467–3469.

- Chapin K, Andrea S. APTIMA Trichomonas vaginalis, a transcription-mediated amplification assay for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in urogenital specimens. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2011; 11:679–688.

- Krashin JW, Koumans EH, Bradshaw-Sydnor AC, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis prevalence, incidence, risk factors and antibiotic-resistance in an adolescent population. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37:440–444.

- Sobel JD, Nyirjesy P, Brown W. Tinidazole therapy for metronidazole-resistant vaginal trichomoniasis. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:1341–1346.

- Nyirjesy P, Gilbert J, Mulcahy LJ. Resistant trichomoniasis: successful treatment with combination therapy. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:962–963.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, McQuillan GM. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2—United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:325–333.

- Roberts CM, Pfister JR, Spear SJ. Increasing proportion of herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes infection in college students. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30:797–800.

- Ryder N, Jin F, McNulty AM, Grulich AE, Donovan B. Increasing role of herpes simplex virus type 1 in first-episode anogenital herpes in heterosexual women and younger men who have sex with men, 1992-2006. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:416–419.