User login

Assessing the Reading Level of Online Sarcoma Patient Education Materials

The diagnosis of cancer is a life-changing event for the patient as well as the patient’s family, friends, and relatives. Once diagnosed, most cancer patients want more information about their prognosis, future procedures, and/or treatment options.1 Receiving such information has been shown to reduce patient anxiety, increase patient satisfaction with care, and improve self-care.2-6 With the evolution of the Internet, patients in general7-9 and, specifically, cancer patients10-17 have turned to websites and online patient education materials (PEMs) to gather more health information.

For online PEMs to convey health information, their reading level must match the health literacy of the individuals who access them. Health literacy is the ability of an individual to gather and comprehend information about their condition to make the best decisions for their health.18 According to a report by the Institute of Medicine, 90 million American adults cannot properly use the US health care system because they do not possess adequate health literacy.18 Additionally, 36% of adults in the United States have basic or less-than-basic health literacy.19 This is starkly contrasted with the 12% of US adults who have proficient health literacy. A 2012 survey showed that about 31% of individuals who look for health information on the Internet have a high school education or less.8 In order to address the low health literacy of adults, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has recommended that online PEMs be written at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level.20

Unfortunately, many online PEMs related to certain cancer21-25 and orthopedic conditions26-31 do not meet NIH recommendations. Only 1 study has specifically looked at PEMs related to an orthopedic cancer condition.32 Lam and colleagues32 evaluated the readability of osteosarcoma PEMs from 56 websites using only 2 readability instruments and identified 86% of the websites as having a greater than eighth-grade reading level. No study has thoroughly assessed the readability of PEMs about bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions nor has any used 10 different readability instruments. Since each readability instrument has different variables (eg, sentence length, number of paragraphs, or number of complex words), averaging the scores of 10 of these instruments may result in less bias.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the readability of online PEMs concerning bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions. The online PEMs came from websites that sarcoma patients may visit to obtain information about their condition. Our hypothesis was that the majority of these online PEMs will have a higher reading level than the NIH recommendations.

Materials and Methods

In May 2013, we identified online PEMs that included background, diagnosis, tests, or treatments for bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and conditions that mimic bone sarcoma. We included articles from the Tumors section of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) website.33 A second source of online PEMs came from a list of academic training centers created through the American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Electronic Internet Database (FREIDA) with search criteria narrowed to orthopedic surgery. If we did not find PEMs of bone and soft-tissue cancers in the orthopedic department of a given academic training center’s website, we searched its cancer center website. We chose 4 programs with PEMs relevant to bone and soft-tissue sarcomas from each region in FREIDA for a balanced representation, except for the Territory region because it had only 1 academic training center and no relevant PEMs. Specialized websites, including Bonetumor.org, Sarcoma Alliance (Sarcomaalliance.org), and Sarcoma Foundation of America (Curesarcoma.org), were also evaluated. Within the Sarcoma Specialists section of the Sarcoma Alliance website,34 sarcoma specialists who were not identified from the FREIDA search for academic training centers were selected for review.

Because 8 of 10 individuals looking for health information on the Internet start their investigation at search engines, we also looked for PEMs through a Google search (Google.com) of bone cancer, and evaluated the first 10 hits for PEMs.8 Of these 10 hits, 8 had relevant PEMs, which we searched for additional PEMs about bone and soft-tissue cancers and related conditions. We also conducted a Google search of the most common bone sarcoma and soft-tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma, respectively, and found 2 additional websites with relevant PEMs. LaCoursiere and colleagues35 surveyed cancer patients who used the Internet and found that they preferred WebMD (Webmd.com) and Medscape (Medscape.com) as sources for content about their medical condition.35 WebMD had been identified in the Google search, and we gathered the PEMs from Medscape also. It is worth noting that some of these websites are written for patients as well as clinicians.

Text from these PEMs were copied and pasted into separate Microsoft Word documents (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Advertisements, pictures, picture text, hyperlinks, copyright notices, page navigation links, paragraphs with no text, and any text that was not related to the given condition were deleted from the document to format the text for the readability software. Then, each Microsoft Word document was uploaded into the software package Readability Studio Professional (RSP) Edition Version 2012.1 for Windows (Oleander Software, Vandalia, Ohio). The 10 distinct readability instruments that were used to gauge the readability of each document were the Flesch Reading Ease score (FRE), the New Fog Count, the New Automated Readability Index, the Coleman-Liau Index (CLI), the Fry readability graph, the New Dale-Chall formula (NDC), the Gunning Frequency of Gobbledygook (Gunning FOG), the Powers-Sumner-Kearl formula, the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), and the Raygor Estimate Graph.

The FRE’s formula takes the average number of words per sentence and average number of syllables per word to compute a score ranging from 0 to 100 with 0 being the hardest to read.36 The New Fog Count tallies the number of sentences, easy words, and hard words (polysyllables) to calculate the grade level of the document.37 The New Automated Readability Index takes the average characters per word and average words per sentence to calculate a grade level for the document.37 The CLI randomly samples a few hundred words from the document, averages the number of letters and sentences per sample, and calculates an estimated grade level.38 The Fry readability graph selects samples of 100 words from the document, averages the number of syllables and sentences per 100 words, plots these data points on a graph, with the intersection determining the reading level.39 The NDC uses a list of 3000 familiar words that most fourth-grade students know.40 The percentage of difficult words, which are not on the list of familiar words, and the average sentence length in words are used to calculate the reading grade level of the document. The Gunning FOG uses the average sentence length in words and the percentage of hard words from a sample of at least 100 words to determine the reading grade level of the document.41 The Powers-Sumner-Kearl formula uses the average sentence length and percentage of monosyllables from a 100-word sample passage to calculate the reading grade level.42 The SMOG formula counts the number of polysyllabic words from 30 sentences and calculates the reading grade level of the document.43 In contrast to other formulas that test for 50% to 75% comprehension, the SMOG formula tests for 100% comprehension. As a result, the SMOG formula generally assigns a reading level 2 grades higher than the Dale-Chall level. The Raygor Estimate Graph selects a 100-word passage, counts the number of sentences and number of words with 6 or more letters, and plots the 2 variables on a graph to determine the reading grade level.44 The software package calculated the results from each reading instrument and reported the mean grade level score

for each document.

Results

We identified a total of 72 websites with relevant PEMs and included them in this study. Of these 72 websites, 36 websites were academic training centers, 10 were Google search hits, and 21 were from the Sarcoma Alliance list of sarcoma specialists. The remaining 5 websites were AAOS, Bonetumor.org, Sarcoma Alliance, Sarcoma Foundation of America, and Medscape. A list of conditions and treatments that were considered relevant PEMs is found in Appendix 1. A total of 774 articles were obtained from the 72 websites.

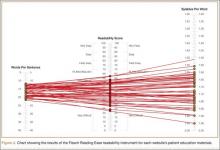

None of the websites had a mean readability score of 7 (seventh grade) or lower (Figures 1A, 1B). Mid-America Sarcoma Institute’s PEMs had the lowest mean readability score, 8.9. The lowest readability score was 5.3, which the New Fog Count readability instrument calculated for Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s (VUMC’s) PEMs (Appendix 2). The mean readability score of all websites was 11.4 (range, 8.9-15.5) (Appendix 2).

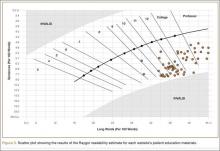

Seventy of 72 websites (97%) had PEMs that were fairly difficult or difficult, according to the FRE analysis (Figure 2). The American Cancer Society and Mid-America Sarcoma Institute had PEMs that were written in plain English. Sixty-nine of 72 websites (96%) had PEMs with a readability score of 10 or higher, according to the Raygor readability estimate (Figure 3). Using this instrument, the scores of the American Cancer Society and the University of Pennsylvania–Joan Karnell Cancer Center were 9; Mid-America Sarcoma Institute’s score was 8.

Discussion

Many cancer patients have turned to websites and online PEMs to gather health information about their condition.10-17 Basch and colleagues10 reported almost a decade ago that 44% of cancer patients, as well as 60% of their companions, used the Internet to find cancer-related information.10 When LaCoursiere and colleagues35 surveyed cancer patients, they found that patients handled their condition better and had less anxiety and uncertainty after using the Internet to find health information and support.35 In addition, many orthopedic patients, specifically 46% of orthopedic community outpatients,45 consult the Internet for information about their condition and future surgical procedures.46,47

This study comprehensively evaluated the readability of online PEMs of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions by using 10 different readability instruments. After identifying 72 websites and 774 articles, we found that all 72 websites’ PEMs had a mean readability score that did not meet the NIH recommendation of writing PEMs at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level. These results are consistent with studies evaluating the readability of online PEMs related to other cancer conditions21-25 and other orthopedic conditions.26-31

The combination of low health literacy of many US adults and high reading grade levels of the majority of online PEMs is not conducive to patients’ better understanding their condition(s). Even individuals with high reading skills prefer information that is simpler to read.48 In many areas of medicine, there is evidence that patients’ understanding of their condition has a positive impact on health outcomes, well-being, and the patient–physician relationship.49-61 Regarding cancer patients, Davis and colleagues54 and Peterson and colleagues57 showed that lower health literacy contributes to less knowledge and lower rates of breast54 and colorectal cancer57 screening tests. Even low health literacy of family caregivers of cancer patients can result in increased stress and lack of communication of important medical information between caregiver and physician.52 Among cancer patients, poor health literacy has been associated with mental distress60 as well as decreased compliance with treatment and lower involvement in clinical trials.55

The disparity between patients’ health literacy and the readability of online PEMs needs to be addressed by finding methods to improve patients’ understanding of their condition and to lower the readability scores of online PEMs. Better communication between patient and physician may improve patients’ comprehension of their condition and different aspects of their care.59,62-66 Doak and colleagues63 recommend giving cancer patients the most important information first; presenting information to patients in smaller doses; intermittently asking patients questions; and incorporating graphs, tables, and drawings into communication with patients.63 Additionally, allowing patients to repeat information they have just received/heard to the physician is another useful tool to improve patient education.62,64-66

Another way to address the disparity between patients’ health literacy and the readability of online PEMs is to reduce the reading grade level of existing PEMs. According to results from this study and others, the majority of online PEMs are above the reading grade level of a significant number of US adults. Many available and inexpensive readability instruments allow authors to assess their articles’ readability. Many writing guidelines also exist to help authors improve the readability of their PEMs.20,64,67-71 Living Word Vocabulary70 and Plain Language71 help authors replace complex words or medical terms with simpler words.29 Visual aids, audio, and video help patients with low health literacy remember the information.64

Efforts to improve PEM readability are effective. Of all the websites reviewed, VUMC was identified as having PEMs with the lowest readability score (5.3). This score was reported by the New Fog Count readability instrument, which accounts for the number of sentences, easy words, and hard words. In 2011, VUMC formed the Department of Patient Education to review and update its online and printed PEMs to make sure patients could read them.72 Additionally, the mean readability scores of the websites of the National Cancer Institute and MedlinePlus are in the top 50% of the websites included in this study. The NIH sponsors both sites, which follow the NIH guidelines for writing online PEMs at a reading level suitable for individuals with lower health literacy.20 These materials serve as potential models to improve the readability of PEMs, and, thus, help patients to better understand their condition, medical procedures, and/or treatment options.

To illustrate ways to improve the reading grade level of PEMs, we used the article “Ewing’s Sarcoma” from the AAOS website73 and followed the NIH guidelines to improve the reading grade level of the article.20 We identified complex words and defined them at an eighth-grade reading level. If that word was mentioned later in the article, simpler terminology was used instead of the initial complex word. For example, Ewing’s sarcoma was defined early and then referred to as bone tumor later in the article. We also identified every word that was 3 syllables or longer and used Microsoft Word’s thesaurus to replace those words with ones that were less than 3 syllables. Lastly, all sentences longer than 15 words were rewritten to be less than 15 words. After making these 3 changes to the article, the mean reading grade level dropped from 11.2 to 7.3.

This study has limitations. First, some readability instruments evaluate the number of syllables per word or polysyllabic words as part of their formula and, thus, can underestimate or overestimate the reading grade level of a document. Some readability formulas consider medical terms such as ulna, femur, or carpal as “easy” words because they have 2 syllables, but many laypersons may not comprehend these words. On the other hand, some readability formulas consider medical terms such as medications, diagnosis, or radiation as “hard” words because they contain 3 or more syllables, but the majority of laypersons likely comprehend these words. Second, the reading level of the patient population accessing those online sites was not assessed. Third, the readability instruments in this study did not evaluate the accuracy of the content, pictures, or tables of the PEMs. However, using 10 readability instruments allowed evaluation of many different readability aspects of the text. Fourth, because some websites identified in this study, such as Bonetumor.org, were written for patients as well as clinicians, the reading grade level of these sites may be higher than that of those sites written just for patients.

Conclusion

Because many orthopedic cancer patients rely on the Internet as a source of information, the need for online PEMs to match the reading skills of the patient population who accesses them is vital. However, this study shows that many organizations, academic training centers, and other entities need to update their online PEMs because all PEMs in this study had a mean readability grade level higher than the NIH recommendation. Further research needs to evaluate the effectiveness of other media, such as video, illustrations, and audio, to provide health information to patients. With many guidelines available that provide plans and advice to improve the readability of PEMs, research also must assess the most effective plans and advice in order to allow authors to focus their attention on 1 set of guidelines to improve the readability of their PEMs.

1. Piredda M, Rocci L, Gualandi R, Petitti T, Vincenzi B, De Marinis MG. Survey on learning needs and preferred sources of information to meet these needs in Italian oncology patients receiving chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(2):120-126.

2. Fernsler JI, Cannon CA. The whys of patient education. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1991;7(2):79-86.

3. Glimelius B, Birgegård G, Hoffman K, Kvale G, Sjödén PO. Information to and communication with cancer patients: improvements and psychosocial correlates in a comprehensive care program for patients and their relatives. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;25(2):171-182.

4. Harris KA. The informational needs of patients with cancer and their families. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(1):39-46.

5. Jensen AB, Madsen B, Andersen P, Rose C. Information for cancer patients entering a clinical trial--an evaluation of an information strategy. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(16):2235-2238.

6. Wells ME, McQuellon RP, Hinkle JS, Cruz JM. Reducing anxiety in newly diagnosed cancer patients: a pilot program. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(2):100-104.

7. Diaz JA, Griffith RA, Ng JJ, Reinert SE, Friedmann PD, Moulton AW. Patients’ use of the Internet for medical information. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):180-185.

8. Fox S, Duggan M. Health Online 2013. Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf. Published January 15, 2013. Accessed November 18. 2014.

9. Schwartz KL, Roe T, Northrup J, Meza J, Seifeldin R, Neale AV. Family medicine patients’ use of the Internet for health information: a MetroNet study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(1):39-45.

10. Basch EM, Thaler HT, Shi W, Yakren S, Schrag D. Use of information resources by patients with cancer and their companions. Cancer. 2004;100(11):2476-2483.

11. Huang GJ, Penson DF. Internet health resources and the cancer patient. Cancer Invest. 2008;26(2):202-207.

12. Metz JM, Devine P, Denittis A, et al. A multi-institutional study of Internet utilization by radiation oncology patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(4):1201-1205.

13. Peterson MW, Fretz PC. Patient use of the internet for information in a lung cancer clinic. Chest. 2003;123(2):452-457.

14. Satterlund MJ, McCaul KD, Sandgren AK. Information gathering over time by breast cancer patients. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5(3):e15.

15. Tustin N. The role of patient satisfaction in online health information seeking. J Health Commun. 2010;15(1):3-17.

16. Van de Poll-Franse LV, Van Eenbergen MC. Internet use by cancer survivors: current use and future wishes. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(10):1189-1195.

17. Ziebland S, Chapple A, Dumelow C, Evans J, Prinjha S, Rozmovits L. How the internet affects patients’ experience of cancer: a qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7439):564.

18. Committee on Health Literacy, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Institute of Medicine. Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. Available at: www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10883. Accessed November 18, 2014.

19. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Ying J, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2006-483. US Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. Available at: www.nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2014.

20. How to write easy-to-read health materials. MedlinePlus website. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html. Updated February 13, 2013. Accessed November 18, 2014.

21. Ellimoottil C, Polcari A, Kadlec A, Gupta G. Readability of websites containing information about prostate cancer treatment options. J Urol. 2012;188(6):2171-2175.

22. Friedman DB, Hoffman-Goetz L, Arocha JF. Health literacy and the World Wide Web: comparing the readability of leading incident cancers on the Internet. Med Inform Internet Med. 2006;31(1):67-87.

23. Hoppe IC. Readability of patient information regarding breast cancer prevention from the Web site of the National Cancer Institute. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(4):490-492.

24. Misra P, Kasabwala K, Agarwal N, Eloy JA, Liu JK. Readability analysis of internet-based patient information regarding skull base tumors. J Neurooncol. 2012;109(3):573-580.

25. Stinson JN, White M, Breakey V, et al. Perspectives on quality and content of information on the internet for adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(1):97-104.

26. Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):199-204.

27. Bluman EM, Foley RP, Chiodo CP. Readability of the Patient Education Section of the AOFAS Website. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(4):287-291.

28. Polishchuk DL, Hashem J, Sabharwal S. Readability of online patient education materials on adult reconstruction Web sites. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):716-719.

29. Sabharwal S, Badarudeen S, Unes Kunju S. Readability of online patient education materials from the AAOS web site. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(5):1245-1250.

30. Vives M, Young L, Sabharwal S. Readability of spine-related patient education materials from subspecialty organization and spine practitioner websites. Spine. 2009;34(25):2826-2831.

31. Wang SW, Capo JT, Orillaza N. Readability and comprehensibility of patient education material in hand-related web sites. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(7):1308-1315.

32. Lam CG, Roter DL, Cohen KJ. Survey of quality, readability, and social reach of websites on osteosarcoma in adolescents. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(1):82-87.

33. Tumors. Quinn RH, ed. OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/menus/tumors.cfm. Accessed November 18, 2014.

34. Sarcoma specialists. Sarcoma Alliance website. sarcomaalliance.org/sarcoma-centers. Accessed November 18, 2014.

35. LaCoursiere SP, Knobf MT, McCorkle R. Cancer patients’ self-reported attitudes about the Internet. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(3):e22.

36. Test your document’s readability. Microsoft Office website. office.microsoft.com/en-us/word-help/test-your-document-s-readability-HP010148506.aspx. Accessed November 18, 2014.

37. Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Naval Technical Training Command. Research Branch Report 8-75. www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a006655.pdf. Published February 1975. Accessed November 18, 2014.

38. Coleman M, Liau TL. A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. J Appl Psychol. 1975;60(2):283-284.

39. Fry E. Fry’s readability graph: clarifications, validity, and extension to Level 17. J Reading. 1977;21(3):242-252.

40. Chall JS, Dale E. Manual for the New Dale-Chall Readability Formula. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books; 1995.

41. Gunning R. The Technique of Clear Writing. Rev. ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1968.

42. Powers RD, Sumner WA, Kearl BE. A recalculation of four adult readability formulas. J Educ Psychol. 1958;49(2):99-105.

43. McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading—a new readability formula. J Reading. 1969;22,639-646.

44. Raygor L. The Raygor readability estimate: a quick and easy way to determine difficulty. In: Pearson PD, Hansen J, eds. Reading Theory, Research and Practice. Twenty-Sixth Yearbook of the National Reading Conference. Clemson, SC: National Reading Conference Inc; 1977:259-263.

45. Krempec J, Hall J, Biermann JS. Internet use by patients in orthopaedic surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 2003;23:80-82.

46. Beall MS, Golladay GJ, Greenfield ML, Hensinger RN, Biermann JS. Use of the Internet by pediatric orthopaedic outpatients. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(2):261-264.

47. Beall MS, Beall MS, Greenfield ML, Biermann JS. Patient Internet use in a community outpatient orthopaedic practice. Iowa Orthop J. 2002;22:103-107.

48. Davis TC, Bocchini JA, Fredrickson D, et al. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97(6 Pt 1):804-810.

49. Apter AJ, Wan F, Reisine S, et al. The association of health literacy with adherence and outcomes in moderate-severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):321-327.

50. Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(12):791-798.

51. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107.

52. Bevan JL, Pecchioni LL. Understanding the impact of family caregiver cancer literacy on patient health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(3):356-364.

53. Corey MR, St Julien J, Miller C, et al. Patient education level affects functionality and long term mortality after major lower extremity amputation. Am J Surg. 2012;204(5):626-630.

54. Davis TC, Arnold C, Berkel HJ, Nandy I, Jackson RH, Glass J. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer. 1996;78(9):1912-1920.

55. Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, Parker RM, Glass J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(3):134-149.

56. Freedman RB, Jones SK, Lin A, Robin AL, Muir KW. Influence of parental health literacy and dosing responsibility on pediatric glaucoma medication adherence. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(3):306-311.

57. Peterson NB, Dwyer KA, Mulvaney SA, Dietrich MS, Rothman RL. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1105-1112.

58. Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1695-1701.

59. Rosas-salazar C, Apter AJ, Canino G, Celedón JC. Health literacy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):935-942.

60. Song L, Mishel M, Bensen JT, et al. How does health literacy affect quality of life among men with newly diagnosed clinically localized prostate cancer? Findings from the North Carolina-Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project (PCaP). Cancer. 2012;118(15):3842-3851.

61. Williams MV, Davis T, Parker RM, Weiss BD. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):383-389.

62. Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Assessing readability of patient education materials: current role in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(10):2572-2580.

63. Doak CC, Doak LG, Friedell GH, Meade CD. Improving comprehension for cancer patients with low literacy skills: strategies for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48(3):151-162.

64. Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients With Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Company; 1996.

65. Kemp EC, Floyd MR, McCord-Duncan E, Lang F. Patients prefer the method of “tell back-collaborative inquiry” to assess understanding of medical information. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(1):24-30.

66. Kripalani S, Bengtzen R, Henderson LE, Jacobson TA. Clinical research in low-literacy populations: using teach-back to assess comprehension of informed consent and privacy information. IRB. 2008;30(2):13-19.

67. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simply Put: A Guide For Creating Easy-to-Understand Materials. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA: Strategic and Proactive Communication Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2009.

68. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Clear & Simple: Developing Effective Print Materials for Low-Literate Readers. Devcompage website. http://devcompage.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/Clear_n_Simple.pdf Published March 2, 1998. Accessed December 1, 2014.

69. Weiss BD. Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and AMA Foundation; 2007:35-41.

70. Dale E, O’Rourke J. The Living Word Vocabulary. Newington, CT: World Book-Childcraft International, 1981.

71. Word suggestions. Plain Language website. www.plainlanguage.gov/howto/wordsuggestions/index.cfm. Accessed November 18, 2014.

72. Rivers K. Initiative aims to enhance patient communication materials. Reporter: Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Weekly Newspaper. April 28, 2011. http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/reporter/index.html?ID=10649. Accessed November 18, 2014.

73. Ewing’s sarcoma. OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00082. Last reviewed September 2011. Accessed November 18, 2014.

The diagnosis of cancer is a life-changing event for the patient as well as the patient’s family, friends, and relatives. Once diagnosed, most cancer patients want more information about their prognosis, future procedures, and/or treatment options.1 Receiving such information has been shown to reduce patient anxiety, increase patient satisfaction with care, and improve self-care.2-6 With the evolution of the Internet, patients in general7-9 and, specifically, cancer patients10-17 have turned to websites and online patient education materials (PEMs) to gather more health information.

For online PEMs to convey health information, their reading level must match the health literacy of the individuals who access them. Health literacy is the ability of an individual to gather and comprehend information about their condition to make the best decisions for their health.18 According to a report by the Institute of Medicine, 90 million American adults cannot properly use the US health care system because they do not possess adequate health literacy.18 Additionally, 36% of adults in the United States have basic or less-than-basic health literacy.19 This is starkly contrasted with the 12% of US adults who have proficient health literacy. A 2012 survey showed that about 31% of individuals who look for health information on the Internet have a high school education or less.8 In order to address the low health literacy of adults, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has recommended that online PEMs be written at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level.20

Unfortunately, many online PEMs related to certain cancer21-25 and orthopedic conditions26-31 do not meet NIH recommendations. Only 1 study has specifically looked at PEMs related to an orthopedic cancer condition.32 Lam and colleagues32 evaluated the readability of osteosarcoma PEMs from 56 websites using only 2 readability instruments and identified 86% of the websites as having a greater than eighth-grade reading level. No study has thoroughly assessed the readability of PEMs about bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions nor has any used 10 different readability instruments. Since each readability instrument has different variables (eg, sentence length, number of paragraphs, or number of complex words), averaging the scores of 10 of these instruments may result in less bias.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the readability of online PEMs concerning bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions. The online PEMs came from websites that sarcoma patients may visit to obtain information about their condition. Our hypothesis was that the majority of these online PEMs will have a higher reading level than the NIH recommendations.

Materials and Methods

In May 2013, we identified online PEMs that included background, diagnosis, tests, or treatments for bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and conditions that mimic bone sarcoma. We included articles from the Tumors section of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) website.33 A second source of online PEMs came from a list of academic training centers created through the American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Electronic Internet Database (FREIDA) with search criteria narrowed to orthopedic surgery. If we did not find PEMs of bone and soft-tissue cancers in the orthopedic department of a given academic training center’s website, we searched its cancer center website. We chose 4 programs with PEMs relevant to bone and soft-tissue sarcomas from each region in FREIDA for a balanced representation, except for the Territory region because it had only 1 academic training center and no relevant PEMs. Specialized websites, including Bonetumor.org, Sarcoma Alliance (Sarcomaalliance.org), and Sarcoma Foundation of America (Curesarcoma.org), were also evaluated. Within the Sarcoma Specialists section of the Sarcoma Alliance website,34 sarcoma specialists who were not identified from the FREIDA search for academic training centers were selected for review.

Because 8 of 10 individuals looking for health information on the Internet start their investigation at search engines, we also looked for PEMs through a Google search (Google.com) of bone cancer, and evaluated the first 10 hits for PEMs.8 Of these 10 hits, 8 had relevant PEMs, which we searched for additional PEMs about bone and soft-tissue cancers and related conditions. We also conducted a Google search of the most common bone sarcoma and soft-tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma, respectively, and found 2 additional websites with relevant PEMs. LaCoursiere and colleagues35 surveyed cancer patients who used the Internet and found that they preferred WebMD (Webmd.com) and Medscape (Medscape.com) as sources for content about their medical condition.35 WebMD had been identified in the Google search, and we gathered the PEMs from Medscape also. It is worth noting that some of these websites are written for patients as well as clinicians.

Text from these PEMs were copied and pasted into separate Microsoft Word documents (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Advertisements, pictures, picture text, hyperlinks, copyright notices, page navigation links, paragraphs with no text, and any text that was not related to the given condition were deleted from the document to format the text for the readability software. Then, each Microsoft Word document was uploaded into the software package Readability Studio Professional (RSP) Edition Version 2012.1 for Windows (Oleander Software, Vandalia, Ohio). The 10 distinct readability instruments that were used to gauge the readability of each document were the Flesch Reading Ease score (FRE), the New Fog Count, the New Automated Readability Index, the Coleman-Liau Index (CLI), the Fry readability graph, the New Dale-Chall formula (NDC), the Gunning Frequency of Gobbledygook (Gunning FOG), the Powers-Sumner-Kearl formula, the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), and the Raygor Estimate Graph.

The FRE’s formula takes the average number of words per sentence and average number of syllables per word to compute a score ranging from 0 to 100 with 0 being the hardest to read.36 The New Fog Count tallies the number of sentences, easy words, and hard words (polysyllables) to calculate the grade level of the document.37 The New Automated Readability Index takes the average characters per word and average words per sentence to calculate a grade level for the document.37 The CLI randomly samples a few hundred words from the document, averages the number of letters and sentences per sample, and calculates an estimated grade level.38 The Fry readability graph selects samples of 100 words from the document, averages the number of syllables and sentences per 100 words, plots these data points on a graph, with the intersection determining the reading level.39 The NDC uses a list of 3000 familiar words that most fourth-grade students know.40 The percentage of difficult words, which are not on the list of familiar words, and the average sentence length in words are used to calculate the reading grade level of the document. The Gunning FOG uses the average sentence length in words and the percentage of hard words from a sample of at least 100 words to determine the reading grade level of the document.41 The Powers-Sumner-Kearl formula uses the average sentence length and percentage of monosyllables from a 100-word sample passage to calculate the reading grade level.42 The SMOG formula counts the number of polysyllabic words from 30 sentences and calculates the reading grade level of the document.43 In contrast to other formulas that test for 50% to 75% comprehension, the SMOG formula tests for 100% comprehension. As a result, the SMOG formula generally assigns a reading level 2 grades higher than the Dale-Chall level. The Raygor Estimate Graph selects a 100-word passage, counts the number of sentences and number of words with 6 or more letters, and plots the 2 variables on a graph to determine the reading grade level.44 The software package calculated the results from each reading instrument and reported the mean grade level score

for each document.

Results

We identified a total of 72 websites with relevant PEMs and included them in this study. Of these 72 websites, 36 websites were academic training centers, 10 were Google search hits, and 21 were from the Sarcoma Alliance list of sarcoma specialists. The remaining 5 websites were AAOS, Bonetumor.org, Sarcoma Alliance, Sarcoma Foundation of America, and Medscape. A list of conditions and treatments that were considered relevant PEMs is found in Appendix 1. A total of 774 articles were obtained from the 72 websites.

None of the websites had a mean readability score of 7 (seventh grade) or lower (Figures 1A, 1B). Mid-America Sarcoma Institute’s PEMs had the lowest mean readability score, 8.9. The lowest readability score was 5.3, which the New Fog Count readability instrument calculated for Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s (VUMC’s) PEMs (Appendix 2). The mean readability score of all websites was 11.4 (range, 8.9-15.5) (Appendix 2).

Seventy of 72 websites (97%) had PEMs that were fairly difficult or difficult, according to the FRE analysis (Figure 2). The American Cancer Society and Mid-America Sarcoma Institute had PEMs that were written in plain English. Sixty-nine of 72 websites (96%) had PEMs with a readability score of 10 or higher, according to the Raygor readability estimate (Figure 3). Using this instrument, the scores of the American Cancer Society and the University of Pennsylvania–Joan Karnell Cancer Center were 9; Mid-America Sarcoma Institute’s score was 8.

Discussion

Many cancer patients have turned to websites and online PEMs to gather health information about their condition.10-17 Basch and colleagues10 reported almost a decade ago that 44% of cancer patients, as well as 60% of their companions, used the Internet to find cancer-related information.10 When LaCoursiere and colleagues35 surveyed cancer patients, they found that patients handled their condition better and had less anxiety and uncertainty after using the Internet to find health information and support.35 In addition, many orthopedic patients, specifically 46% of orthopedic community outpatients,45 consult the Internet for information about their condition and future surgical procedures.46,47

This study comprehensively evaluated the readability of online PEMs of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions by using 10 different readability instruments. After identifying 72 websites and 774 articles, we found that all 72 websites’ PEMs had a mean readability score that did not meet the NIH recommendation of writing PEMs at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level. These results are consistent with studies evaluating the readability of online PEMs related to other cancer conditions21-25 and other orthopedic conditions.26-31

The combination of low health literacy of many US adults and high reading grade levels of the majority of online PEMs is not conducive to patients’ better understanding their condition(s). Even individuals with high reading skills prefer information that is simpler to read.48 In many areas of medicine, there is evidence that patients’ understanding of their condition has a positive impact on health outcomes, well-being, and the patient–physician relationship.49-61 Regarding cancer patients, Davis and colleagues54 and Peterson and colleagues57 showed that lower health literacy contributes to less knowledge and lower rates of breast54 and colorectal cancer57 screening tests. Even low health literacy of family caregivers of cancer patients can result in increased stress and lack of communication of important medical information between caregiver and physician.52 Among cancer patients, poor health literacy has been associated with mental distress60 as well as decreased compliance with treatment and lower involvement in clinical trials.55

The disparity between patients’ health literacy and the readability of online PEMs needs to be addressed by finding methods to improve patients’ understanding of their condition and to lower the readability scores of online PEMs. Better communication between patient and physician may improve patients’ comprehension of their condition and different aspects of their care.59,62-66 Doak and colleagues63 recommend giving cancer patients the most important information first; presenting information to patients in smaller doses; intermittently asking patients questions; and incorporating graphs, tables, and drawings into communication with patients.63 Additionally, allowing patients to repeat information they have just received/heard to the physician is another useful tool to improve patient education.62,64-66

Another way to address the disparity between patients’ health literacy and the readability of online PEMs is to reduce the reading grade level of existing PEMs. According to results from this study and others, the majority of online PEMs are above the reading grade level of a significant number of US adults. Many available and inexpensive readability instruments allow authors to assess their articles’ readability. Many writing guidelines also exist to help authors improve the readability of their PEMs.20,64,67-71 Living Word Vocabulary70 and Plain Language71 help authors replace complex words or medical terms with simpler words.29 Visual aids, audio, and video help patients with low health literacy remember the information.64

Efforts to improve PEM readability are effective. Of all the websites reviewed, VUMC was identified as having PEMs with the lowest readability score (5.3). This score was reported by the New Fog Count readability instrument, which accounts for the number of sentences, easy words, and hard words. In 2011, VUMC formed the Department of Patient Education to review and update its online and printed PEMs to make sure patients could read them.72 Additionally, the mean readability scores of the websites of the National Cancer Institute and MedlinePlus are in the top 50% of the websites included in this study. The NIH sponsors both sites, which follow the NIH guidelines for writing online PEMs at a reading level suitable for individuals with lower health literacy.20 These materials serve as potential models to improve the readability of PEMs, and, thus, help patients to better understand their condition, medical procedures, and/or treatment options.

To illustrate ways to improve the reading grade level of PEMs, we used the article “Ewing’s Sarcoma” from the AAOS website73 and followed the NIH guidelines to improve the reading grade level of the article.20 We identified complex words and defined them at an eighth-grade reading level. If that word was mentioned later in the article, simpler terminology was used instead of the initial complex word. For example, Ewing’s sarcoma was defined early and then referred to as bone tumor later in the article. We also identified every word that was 3 syllables or longer and used Microsoft Word’s thesaurus to replace those words with ones that were less than 3 syllables. Lastly, all sentences longer than 15 words were rewritten to be less than 15 words. After making these 3 changes to the article, the mean reading grade level dropped from 11.2 to 7.3.

This study has limitations. First, some readability instruments evaluate the number of syllables per word or polysyllabic words as part of their formula and, thus, can underestimate or overestimate the reading grade level of a document. Some readability formulas consider medical terms such as ulna, femur, or carpal as “easy” words because they have 2 syllables, but many laypersons may not comprehend these words. On the other hand, some readability formulas consider medical terms such as medications, diagnosis, or radiation as “hard” words because they contain 3 or more syllables, but the majority of laypersons likely comprehend these words. Second, the reading level of the patient population accessing those online sites was not assessed. Third, the readability instruments in this study did not evaluate the accuracy of the content, pictures, or tables of the PEMs. However, using 10 readability instruments allowed evaluation of many different readability aspects of the text. Fourth, because some websites identified in this study, such as Bonetumor.org, were written for patients as well as clinicians, the reading grade level of these sites may be higher than that of those sites written just for patients.

Conclusion

Because many orthopedic cancer patients rely on the Internet as a source of information, the need for online PEMs to match the reading skills of the patient population who accesses them is vital. However, this study shows that many organizations, academic training centers, and other entities need to update their online PEMs because all PEMs in this study had a mean readability grade level higher than the NIH recommendation. Further research needs to evaluate the effectiveness of other media, such as video, illustrations, and audio, to provide health information to patients. With many guidelines available that provide plans and advice to improve the readability of PEMs, research also must assess the most effective plans and advice in order to allow authors to focus their attention on 1 set of guidelines to improve the readability of their PEMs.

The diagnosis of cancer is a life-changing event for the patient as well as the patient’s family, friends, and relatives. Once diagnosed, most cancer patients want more information about their prognosis, future procedures, and/or treatment options.1 Receiving such information has been shown to reduce patient anxiety, increase patient satisfaction with care, and improve self-care.2-6 With the evolution of the Internet, patients in general7-9 and, specifically, cancer patients10-17 have turned to websites and online patient education materials (PEMs) to gather more health information.

For online PEMs to convey health information, their reading level must match the health literacy of the individuals who access them. Health literacy is the ability of an individual to gather and comprehend information about their condition to make the best decisions for their health.18 According to a report by the Institute of Medicine, 90 million American adults cannot properly use the US health care system because they do not possess adequate health literacy.18 Additionally, 36% of adults in the United States have basic or less-than-basic health literacy.19 This is starkly contrasted with the 12% of US adults who have proficient health literacy. A 2012 survey showed that about 31% of individuals who look for health information on the Internet have a high school education or less.8 In order to address the low health literacy of adults, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has recommended that online PEMs be written at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level.20

Unfortunately, many online PEMs related to certain cancer21-25 and orthopedic conditions26-31 do not meet NIH recommendations. Only 1 study has specifically looked at PEMs related to an orthopedic cancer condition.32 Lam and colleagues32 evaluated the readability of osteosarcoma PEMs from 56 websites using only 2 readability instruments and identified 86% of the websites as having a greater than eighth-grade reading level. No study has thoroughly assessed the readability of PEMs about bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions nor has any used 10 different readability instruments. Since each readability instrument has different variables (eg, sentence length, number of paragraphs, or number of complex words), averaging the scores of 10 of these instruments may result in less bias.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the readability of online PEMs concerning bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions. The online PEMs came from websites that sarcoma patients may visit to obtain information about their condition. Our hypothesis was that the majority of these online PEMs will have a higher reading level than the NIH recommendations.

Materials and Methods

In May 2013, we identified online PEMs that included background, diagnosis, tests, or treatments for bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and conditions that mimic bone sarcoma. We included articles from the Tumors section of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) website.33 A second source of online PEMs came from a list of academic training centers created through the American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Electronic Internet Database (FREIDA) with search criteria narrowed to orthopedic surgery. If we did not find PEMs of bone and soft-tissue cancers in the orthopedic department of a given academic training center’s website, we searched its cancer center website. We chose 4 programs with PEMs relevant to bone and soft-tissue sarcomas from each region in FREIDA for a balanced representation, except for the Territory region because it had only 1 academic training center and no relevant PEMs. Specialized websites, including Bonetumor.org, Sarcoma Alliance (Sarcomaalliance.org), and Sarcoma Foundation of America (Curesarcoma.org), were also evaluated. Within the Sarcoma Specialists section of the Sarcoma Alliance website,34 sarcoma specialists who were not identified from the FREIDA search for academic training centers were selected for review.

Because 8 of 10 individuals looking for health information on the Internet start their investigation at search engines, we also looked for PEMs through a Google search (Google.com) of bone cancer, and evaluated the first 10 hits for PEMs.8 Of these 10 hits, 8 had relevant PEMs, which we searched for additional PEMs about bone and soft-tissue cancers and related conditions. We also conducted a Google search of the most common bone sarcoma and soft-tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma, respectively, and found 2 additional websites with relevant PEMs. LaCoursiere and colleagues35 surveyed cancer patients who used the Internet and found that they preferred WebMD (Webmd.com) and Medscape (Medscape.com) as sources for content about their medical condition.35 WebMD had been identified in the Google search, and we gathered the PEMs from Medscape also. It is worth noting that some of these websites are written for patients as well as clinicians.

Text from these PEMs were copied and pasted into separate Microsoft Word documents (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Advertisements, pictures, picture text, hyperlinks, copyright notices, page navigation links, paragraphs with no text, and any text that was not related to the given condition were deleted from the document to format the text for the readability software. Then, each Microsoft Word document was uploaded into the software package Readability Studio Professional (RSP) Edition Version 2012.1 for Windows (Oleander Software, Vandalia, Ohio). The 10 distinct readability instruments that were used to gauge the readability of each document were the Flesch Reading Ease score (FRE), the New Fog Count, the New Automated Readability Index, the Coleman-Liau Index (CLI), the Fry readability graph, the New Dale-Chall formula (NDC), the Gunning Frequency of Gobbledygook (Gunning FOG), the Powers-Sumner-Kearl formula, the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), and the Raygor Estimate Graph.

The FRE’s formula takes the average number of words per sentence and average number of syllables per word to compute a score ranging from 0 to 100 with 0 being the hardest to read.36 The New Fog Count tallies the number of sentences, easy words, and hard words (polysyllables) to calculate the grade level of the document.37 The New Automated Readability Index takes the average characters per word and average words per sentence to calculate a grade level for the document.37 The CLI randomly samples a few hundred words from the document, averages the number of letters and sentences per sample, and calculates an estimated grade level.38 The Fry readability graph selects samples of 100 words from the document, averages the number of syllables and sentences per 100 words, plots these data points on a graph, with the intersection determining the reading level.39 The NDC uses a list of 3000 familiar words that most fourth-grade students know.40 The percentage of difficult words, which are not on the list of familiar words, and the average sentence length in words are used to calculate the reading grade level of the document. The Gunning FOG uses the average sentence length in words and the percentage of hard words from a sample of at least 100 words to determine the reading grade level of the document.41 The Powers-Sumner-Kearl formula uses the average sentence length and percentage of monosyllables from a 100-word sample passage to calculate the reading grade level.42 The SMOG formula counts the number of polysyllabic words from 30 sentences and calculates the reading grade level of the document.43 In contrast to other formulas that test for 50% to 75% comprehension, the SMOG formula tests for 100% comprehension. As a result, the SMOG formula generally assigns a reading level 2 grades higher than the Dale-Chall level. The Raygor Estimate Graph selects a 100-word passage, counts the number of sentences and number of words with 6 or more letters, and plots the 2 variables on a graph to determine the reading grade level.44 The software package calculated the results from each reading instrument and reported the mean grade level score

for each document.

Results

We identified a total of 72 websites with relevant PEMs and included them in this study. Of these 72 websites, 36 websites were academic training centers, 10 were Google search hits, and 21 were from the Sarcoma Alliance list of sarcoma specialists. The remaining 5 websites were AAOS, Bonetumor.org, Sarcoma Alliance, Sarcoma Foundation of America, and Medscape. A list of conditions and treatments that were considered relevant PEMs is found in Appendix 1. A total of 774 articles were obtained from the 72 websites.

None of the websites had a mean readability score of 7 (seventh grade) or lower (Figures 1A, 1B). Mid-America Sarcoma Institute’s PEMs had the lowest mean readability score, 8.9. The lowest readability score was 5.3, which the New Fog Count readability instrument calculated for Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s (VUMC’s) PEMs (Appendix 2). The mean readability score of all websites was 11.4 (range, 8.9-15.5) (Appendix 2).

Seventy of 72 websites (97%) had PEMs that were fairly difficult or difficult, according to the FRE analysis (Figure 2). The American Cancer Society and Mid-America Sarcoma Institute had PEMs that were written in plain English. Sixty-nine of 72 websites (96%) had PEMs with a readability score of 10 or higher, according to the Raygor readability estimate (Figure 3). Using this instrument, the scores of the American Cancer Society and the University of Pennsylvania–Joan Karnell Cancer Center were 9; Mid-America Sarcoma Institute’s score was 8.

Discussion

Many cancer patients have turned to websites and online PEMs to gather health information about their condition.10-17 Basch and colleagues10 reported almost a decade ago that 44% of cancer patients, as well as 60% of their companions, used the Internet to find cancer-related information.10 When LaCoursiere and colleagues35 surveyed cancer patients, they found that patients handled their condition better and had less anxiety and uncertainty after using the Internet to find health information and support.35 In addition, many orthopedic patients, specifically 46% of orthopedic community outpatients,45 consult the Internet for information about their condition and future surgical procedures.46,47

This study comprehensively evaluated the readability of online PEMs of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and related conditions by using 10 different readability instruments. After identifying 72 websites and 774 articles, we found that all 72 websites’ PEMs had a mean readability score that did not meet the NIH recommendation of writing PEMs at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level. These results are consistent with studies evaluating the readability of online PEMs related to other cancer conditions21-25 and other orthopedic conditions.26-31

The combination of low health literacy of many US adults and high reading grade levels of the majority of online PEMs is not conducive to patients’ better understanding their condition(s). Even individuals with high reading skills prefer information that is simpler to read.48 In many areas of medicine, there is evidence that patients’ understanding of their condition has a positive impact on health outcomes, well-being, and the patient–physician relationship.49-61 Regarding cancer patients, Davis and colleagues54 and Peterson and colleagues57 showed that lower health literacy contributes to less knowledge and lower rates of breast54 and colorectal cancer57 screening tests. Even low health literacy of family caregivers of cancer patients can result in increased stress and lack of communication of important medical information between caregiver and physician.52 Among cancer patients, poor health literacy has been associated with mental distress60 as well as decreased compliance with treatment and lower involvement in clinical trials.55

The disparity between patients’ health literacy and the readability of online PEMs needs to be addressed by finding methods to improve patients’ understanding of their condition and to lower the readability scores of online PEMs. Better communication between patient and physician may improve patients’ comprehension of their condition and different aspects of their care.59,62-66 Doak and colleagues63 recommend giving cancer patients the most important information first; presenting information to patients in smaller doses; intermittently asking patients questions; and incorporating graphs, tables, and drawings into communication with patients.63 Additionally, allowing patients to repeat information they have just received/heard to the physician is another useful tool to improve patient education.62,64-66

Another way to address the disparity between patients’ health literacy and the readability of online PEMs is to reduce the reading grade level of existing PEMs. According to results from this study and others, the majority of online PEMs are above the reading grade level of a significant number of US adults. Many available and inexpensive readability instruments allow authors to assess their articles’ readability. Many writing guidelines also exist to help authors improve the readability of their PEMs.20,64,67-71 Living Word Vocabulary70 and Plain Language71 help authors replace complex words or medical terms with simpler words.29 Visual aids, audio, and video help patients with low health literacy remember the information.64

Efforts to improve PEM readability are effective. Of all the websites reviewed, VUMC was identified as having PEMs with the lowest readability score (5.3). This score was reported by the New Fog Count readability instrument, which accounts for the number of sentences, easy words, and hard words. In 2011, VUMC formed the Department of Patient Education to review and update its online and printed PEMs to make sure patients could read them.72 Additionally, the mean readability scores of the websites of the National Cancer Institute and MedlinePlus are in the top 50% of the websites included in this study. The NIH sponsors both sites, which follow the NIH guidelines for writing online PEMs at a reading level suitable for individuals with lower health literacy.20 These materials serve as potential models to improve the readability of PEMs, and, thus, help patients to better understand their condition, medical procedures, and/or treatment options.

To illustrate ways to improve the reading grade level of PEMs, we used the article “Ewing’s Sarcoma” from the AAOS website73 and followed the NIH guidelines to improve the reading grade level of the article.20 We identified complex words and defined them at an eighth-grade reading level. If that word was mentioned later in the article, simpler terminology was used instead of the initial complex word. For example, Ewing’s sarcoma was defined early and then referred to as bone tumor later in the article. We also identified every word that was 3 syllables or longer and used Microsoft Word’s thesaurus to replace those words with ones that were less than 3 syllables. Lastly, all sentences longer than 15 words were rewritten to be less than 15 words. After making these 3 changes to the article, the mean reading grade level dropped from 11.2 to 7.3.

This study has limitations. First, some readability instruments evaluate the number of syllables per word or polysyllabic words as part of their formula and, thus, can underestimate or overestimate the reading grade level of a document. Some readability formulas consider medical terms such as ulna, femur, or carpal as “easy” words because they have 2 syllables, but many laypersons may not comprehend these words. On the other hand, some readability formulas consider medical terms such as medications, diagnosis, or radiation as “hard” words because they contain 3 or more syllables, but the majority of laypersons likely comprehend these words. Second, the reading level of the patient population accessing those online sites was not assessed. Third, the readability instruments in this study did not evaluate the accuracy of the content, pictures, or tables of the PEMs. However, using 10 readability instruments allowed evaluation of many different readability aspects of the text. Fourth, because some websites identified in this study, such as Bonetumor.org, were written for patients as well as clinicians, the reading grade level of these sites may be higher than that of those sites written just for patients.

Conclusion

Because many orthopedic cancer patients rely on the Internet as a source of information, the need for online PEMs to match the reading skills of the patient population who accesses them is vital. However, this study shows that many organizations, academic training centers, and other entities need to update their online PEMs because all PEMs in this study had a mean readability grade level higher than the NIH recommendation. Further research needs to evaluate the effectiveness of other media, such as video, illustrations, and audio, to provide health information to patients. With many guidelines available that provide plans and advice to improve the readability of PEMs, research also must assess the most effective plans and advice in order to allow authors to focus their attention on 1 set of guidelines to improve the readability of their PEMs.

1. Piredda M, Rocci L, Gualandi R, Petitti T, Vincenzi B, De Marinis MG. Survey on learning needs and preferred sources of information to meet these needs in Italian oncology patients receiving chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(2):120-126.

2. Fernsler JI, Cannon CA. The whys of patient education. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1991;7(2):79-86.

3. Glimelius B, Birgegård G, Hoffman K, Kvale G, Sjödén PO. Information to and communication with cancer patients: improvements and psychosocial correlates in a comprehensive care program for patients and their relatives. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;25(2):171-182.

4. Harris KA. The informational needs of patients with cancer and their families. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(1):39-46.

5. Jensen AB, Madsen B, Andersen P, Rose C. Information for cancer patients entering a clinical trial--an evaluation of an information strategy. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(16):2235-2238.

6. Wells ME, McQuellon RP, Hinkle JS, Cruz JM. Reducing anxiety in newly diagnosed cancer patients: a pilot program. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(2):100-104.

7. Diaz JA, Griffith RA, Ng JJ, Reinert SE, Friedmann PD, Moulton AW. Patients’ use of the Internet for medical information. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):180-185.

8. Fox S, Duggan M. Health Online 2013. Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf. Published January 15, 2013. Accessed November 18. 2014.

9. Schwartz KL, Roe T, Northrup J, Meza J, Seifeldin R, Neale AV. Family medicine patients’ use of the Internet for health information: a MetroNet study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(1):39-45.

10. Basch EM, Thaler HT, Shi W, Yakren S, Schrag D. Use of information resources by patients with cancer and their companions. Cancer. 2004;100(11):2476-2483.

11. Huang GJ, Penson DF. Internet health resources and the cancer patient. Cancer Invest. 2008;26(2):202-207.

12. Metz JM, Devine P, Denittis A, et al. A multi-institutional study of Internet utilization by radiation oncology patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(4):1201-1205.

13. Peterson MW, Fretz PC. Patient use of the internet for information in a lung cancer clinic. Chest. 2003;123(2):452-457.

14. Satterlund MJ, McCaul KD, Sandgren AK. Information gathering over time by breast cancer patients. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5(3):e15.

15. Tustin N. The role of patient satisfaction in online health information seeking. J Health Commun. 2010;15(1):3-17.

16. Van de Poll-Franse LV, Van Eenbergen MC. Internet use by cancer survivors: current use and future wishes. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(10):1189-1195.

17. Ziebland S, Chapple A, Dumelow C, Evans J, Prinjha S, Rozmovits L. How the internet affects patients’ experience of cancer: a qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7439):564.

18. Committee on Health Literacy, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Institute of Medicine. Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. Available at: www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10883. Accessed November 18, 2014.

19. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Ying J, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2006-483. US Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. Available at: www.nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2014.

20. How to write easy-to-read health materials. MedlinePlus website. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html. Updated February 13, 2013. Accessed November 18, 2014.

21. Ellimoottil C, Polcari A, Kadlec A, Gupta G. Readability of websites containing information about prostate cancer treatment options. J Urol. 2012;188(6):2171-2175.

22. Friedman DB, Hoffman-Goetz L, Arocha JF. Health literacy and the World Wide Web: comparing the readability of leading incident cancers on the Internet. Med Inform Internet Med. 2006;31(1):67-87.

23. Hoppe IC. Readability of patient information regarding breast cancer prevention from the Web site of the National Cancer Institute. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(4):490-492.

24. Misra P, Kasabwala K, Agarwal N, Eloy JA, Liu JK. Readability analysis of internet-based patient information regarding skull base tumors. J Neurooncol. 2012;109(3):573-580.

25. Stinson JN, White M, Breakey V, et al. Perspectives on quality and content of information on the internet for adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(1):97-104.

26. Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):199-204.

27. Bluman EM, Foley RP, Chiodo CP. Readability of the Patient Education Section of the AOFAS Website. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(4):287-291.

28. Polishchuk DL, Hashem J, Sabharwal S. Readability of online patient education materials on adult reconstruction Web sites. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):716-719.

29. Sabharwal S, Badarudeen S, Unes Kunju S. Readability of online patient education materials from the AAOS web site. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(5):1245-1250.

30. Vives M, Young L, Sabharwal S. Readability of spine-related patient education materials from subspecialty organization and spine practitioner websites. Spine. 2009;34(25):2826-2831.

31. Wang SW, Capo JT, Orillaza N. Readability and comprehensibility of patient education material in hand-related web sites. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(7):1308-1315.

32. Lam CG, Roter DL, Cohen KJ. Survey of quality, readability, and social reach of websites on osteosarcoma in adolescents. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(1):82-87.

33. Tumors. Quinn RH, ed. OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/menus/tumors.cfm. Accessed November 18, 2014.

34. Sarcoma specialists. Sarcoma Alliance website. sarcomaalliance.org/sarcoma-centers. Accessed November 18, 2014.

35. LaCoursiere SP, Knobf MT, McCorkle R. Cancer patients’ self-reported attitudes about the Internet. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(3):e22.

36. Test your document’s readability. Microsoft Office website. office.microsoft.com/en-us/word-help/test-your-document-s-readability-HP010148506.aspx. Accessed November 18, 2014.

37. Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Naval Technical Training Command. Research Branch Report 8-75. www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a006655.pdf. Published February 1975. Accessed November 18, 2014.

38. Coleman M, Liau TL. A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. J Appl Psychol. 1975;60(2):283-284.

39. Fry E. Fry’s readability graph: clarifications, validity, and extension to Level 17. J Reading. 1977;21(3):242-252.

40. Chall JS, Dale E. Manual for the New Dale-Chall Readability Formula. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books; 1995.

41. Gunning R. The Technique of Clear Writing. Rev. ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1968.

42. Powers RD, Sumner WA, Kearl BE. A recalculation of four adult readability formulas. J Educ Psychol. 1958;49(2):99-105.

43. McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading—a new readability formula. J Reading. 1969;22,639-646.

44. Raygor L. The Raygor readability estimate: a quick and easy way to determine difficulty. In: Pearson PD, Hansen J, eds. Reading Theory, Research and Practice. Twenty-Sixth Yearbook of the National Reading Conference. Clemson, SC: National Reading Conference Inc; 1977:259-263.

45. Krempec J, Hall J, Biermann JS. Internet use by patients in orthopaedic surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 2003;23:80-82.

46. Beall MS, Golladay GJ, Greenfield ML, Hensinger RN, Biermann JS. Use of the Internet by pediatric orthopaedic outpatients. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(2):261-264.

47. Beall MS, Beall MS, Greenfield ML, Biermann JS. Patient Internet use in a community outpatient orthopaedic practice. Iowa Orthop J. 2002;22:103-107.

48. Davis TC, Bocchini JA, Fredrickson D, et al. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97(6 Pt 1):804-810.

49. Apter AJ, Wan F, Reisine S, et al. The association of health literacy with adherence and outcomes in moderate-severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):321-327.

50. Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(12):791-798.

51. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107.

52. Bevan JL, Pecchioni LL. Understanding the impact of family caregiver cancer literacy on patient health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(3):356-364.

53. Corey MR, St Julien J, Miller C, et al. Patient education level affects functionality and long term mortality after major lower extremity amputation. Am J Surg. 2012;204(5):626-630.

54. Davis TC, Arnold C, Berkel HJ, Nandy I, Jackson RH, Glass J. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer. 1996;78(9):1912-1920.

55. Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, Parker RM, Glass J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(3):134-149.

56. Freedman RB, Jones SK, Lin A, Robin AL, Muir KW. Influence of parental health literacy and dosing responsibility on pediatric glaucoma medication adherence. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(3):306-311.

57. Peterson NB, Dwyer KA, Mulvaney SA, Dietrich MS, Rothman RL. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1105-1112.

58. Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1695-1701.

59. Rosas-salazar C, Apter AJ, Canino G, Celedón JC. Health literacy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):935-942.

60. Song L, Mishel M, Bensen JT, et al. How does health literacy affect quality of life among men with newly diagnosed clinically localized prostate cancer? Findings from the North Carolina-Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project (PCaP). Cancer. 2012;118(15):3842-3851.

61. Williams MV, Davis T, Parker RM, Weiss BD. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):383-389.

62. Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Assessing readability of patient education materials: current role in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(10):2572-2580.

63. Doak CC, Doak LG, Friedell GH, Meade CD. Improving comprehension for cancer patients with low literacy skills: strategies for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48(3):151-162.

64. Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients With Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Company; 1996.

65. Kemp EC, Floyd MR, McCord-Duncan E, Lang F. Patients prefer the method of “tell back-collaborative inquiry” to assess understanding of medical information. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(1):24-30.

66. Kripalani S, Bengtzen R, Henderson LE, Jacobson TA. Clinical research in low-literacy populations: using teach-back to assess comprehension of informed consent and privacy information. IRB. 2008;30(2):13-19.

67. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simply Put: A Guide For Creating Easy-to-Understand Materials. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA: Strategic and Proactive Communication Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2009.

68. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Clear & Simple: Developing Effective Print Materials for Low-Literate Readers. Devcompage website. http://devcompage.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/Clear_n_Simple.pdf Published March 2, 1998. Accessed December 1, 2014.

69. Weiss BD. Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and AMA Foundation; 2007:35-41.

70. Dale E, O’Rourke J. The Living Word Vocabulary. Newington, CT: World Book-Childcraft International, 1981.

71. Word suggestions. Plain Language website. www.plainlanguage.gov/howto/wordsuggestions/index.cfm. Accessed November 18, 2014.

72. Rivers K. Initiative aims to enhance patient communication materials. Reporter: Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Weekly Newspaper. April 28, 2011. http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/reporter/index.html?ID=10649. Accessed November 18, 2014.

73. Ewing’s sarcoma. OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00082. Last reviewed September 2011. Accessed November 18, 2014.

1. Piredda M, Rocci L, Gualandi R, Petitti T, Vincenzi B, De Marinis MG. Survey on learning needs and preferred sources of information to meet these needs in Italian oncology patients receiving chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(2):120-126.

2. Fernsler JI, Cannon CA. The whys of patient education. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1991;7(2):79-86.

3. Glimelius B, Birgegård G, Hoffman K, Kvale G, Sjödén PO. Information to and communication with cancer patients: improvements and psychosocial correlates in a comprehensive care program for patients and their relatives. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;25(2):171-182.

4. Harris KA. The informational needs of patients with cancer and their families. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(1):39-46.

5. Jensen AB, Madsen B, Andersen P, Rose C. Information for cancer patients entering a clinical trial--an evaluation of an information strategy. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(16):2235-2238.