User login

Development and Validation of an Administrative Algorithm to Identify Veterans With Epilepsy

Development and Validation of an Administrative Algorithm to Identify Veterans With Epilepsy

Epilepsy affects about 4.5 million people in the United States and 150,000 new individuals are diagnosed each year.1,2 In 2019, epilepsy-attributable health care spending for noninstitutionalized people was around $5.4 billion and total epilepsy-attributable and epilepsy or seizure health care-related costs totaled $54 billion.3

Accurate surveillance of epilepsy in large health care systems can potentially improve health care delivery and resource allocation. A 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report identified 13 recommendations to guide public health action on epilepsy, including validation of standard definitions for case ascertainment, identification of epilepsy through screening programs or protocols, and expansion of surveillance to better understand disease burden.4

A systematic review of validation studies concluded that it is reasonable to use administrative data to identify people with epilepsy in epidemiologic research. Combining The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for epilepsy (ICD-10, G40-41; ICD-9, 345) with antiseizure medications (ASMs) could provide high positive predictive values (PPVs) and combining symptoms codes for convulsions (ICD-10, R56; ICD-9, 780.3, 780.39) with ASMs could lead to high sensitivity.5 However, identifying individuals with epilepsy from administrative data in large managed health care organizations is challenging.6 The IOM report noted that large managed health care organizations presented varying incidence and prevalence estimates due to differing methodology, geographic area, demographics, and definitions of epilepsy.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated US health care system, providing care to > 9.1 million veterans.7 To improve the health and well-being of veterans with epilepsy (VWEs), a network of sites was established in 2008 called the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Epilepsy Centers of Excellence (ECoE). Subsequent to the creation of the ECoE, efforts were made to identify VWEs within VHA databases.8,9 Prior to fiscal year (FY) 2016, the ECoE adopted a modified version of a well-established epilepsy diagnostic algorithm developed by Holden et al for large managed care organizations.10 The original algorithm identified patients by cross-matching ASMs with ICD-9 codes for an index year. But it failed to capture a considerable number of stable patients with epilepsy in the VHA due to incomplete documentation, and had false positives due to inclusion of patients identified from diagnostic clinics. The modified algorithm the ECoE used prior to FY 2016 considered additional prior years and excluded encounters from diagnostic clinics. The result was an improvement in the sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm. Researchers evaluating 500 patients with epilepsy estimated that the modified algorithm had a PPV of 82.0% (95% CI, 78.6%-85.4%).11

After implementation of ICD-10 codes in the VHA in FY 2016, the task of reliably and efficiently identifying VWE led to a 3-tier algorithm. This article presents a validation of the different tiers of this algorithm after the implementation of ICD-10 diagnosis codes and summarizes the surveillance data collected over the years within the VHA showing the trends of epilepsy.

Methods

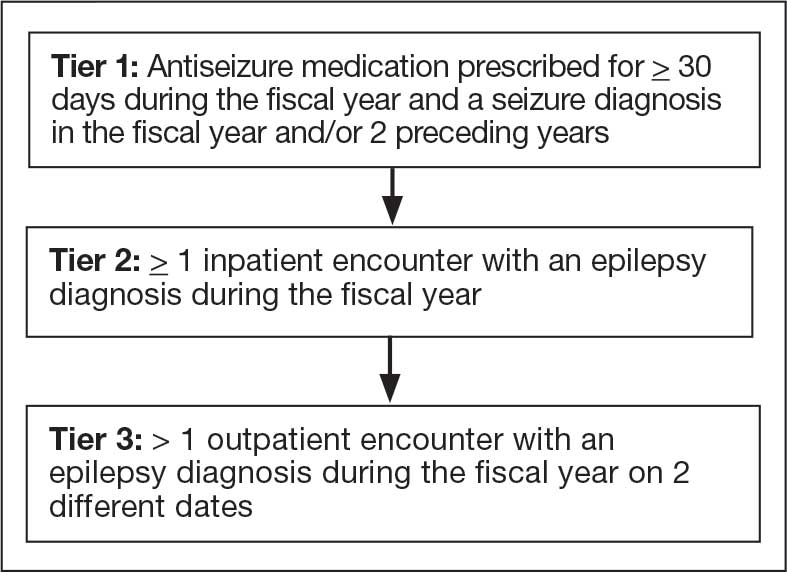

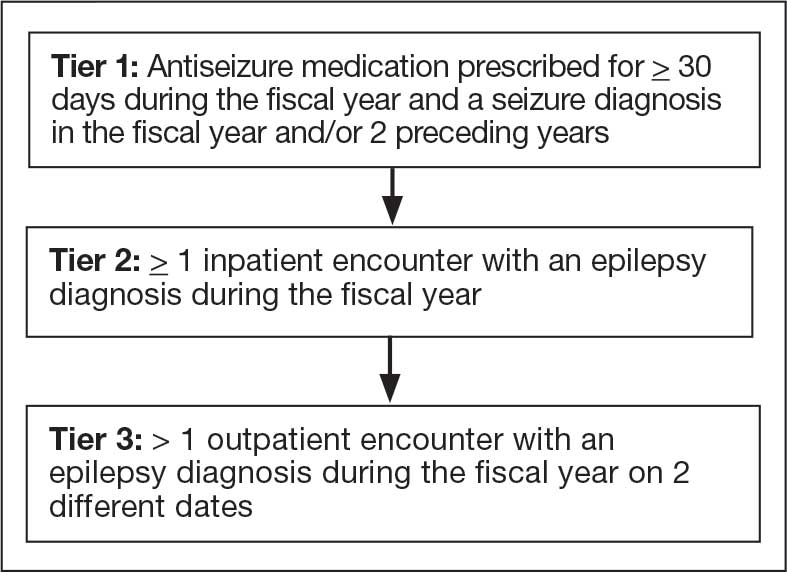

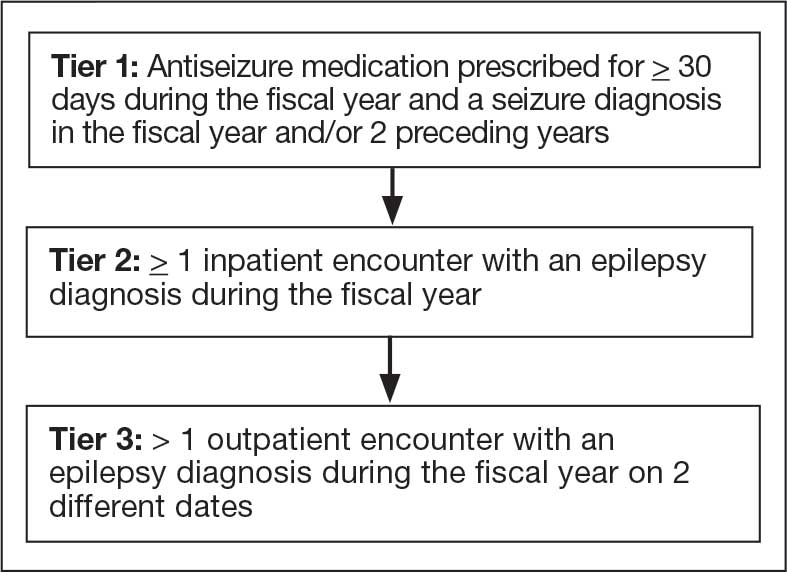

The VHA National Neurology office commissioned a Neurology Cube dashboard in FY 2021 in collaboration with VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) for reporting and surveillance of VWEs as a quality improvement initiative. The Neurology Cube uses a 3-tier system for identifying VWE in the VHA databases. VSSC programmers extract data from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and utilize Microsoft SQL Server and Microsoft Power BI for Neurology Cube reports. The 3-tier system identifies VWE and divides them into distinct groups. The first tier identifies VWE with the highest degree of confidence; Tiers 2 and 3 represent identification with successively lesser degrees of confidence (Figure 1).

Tier 1

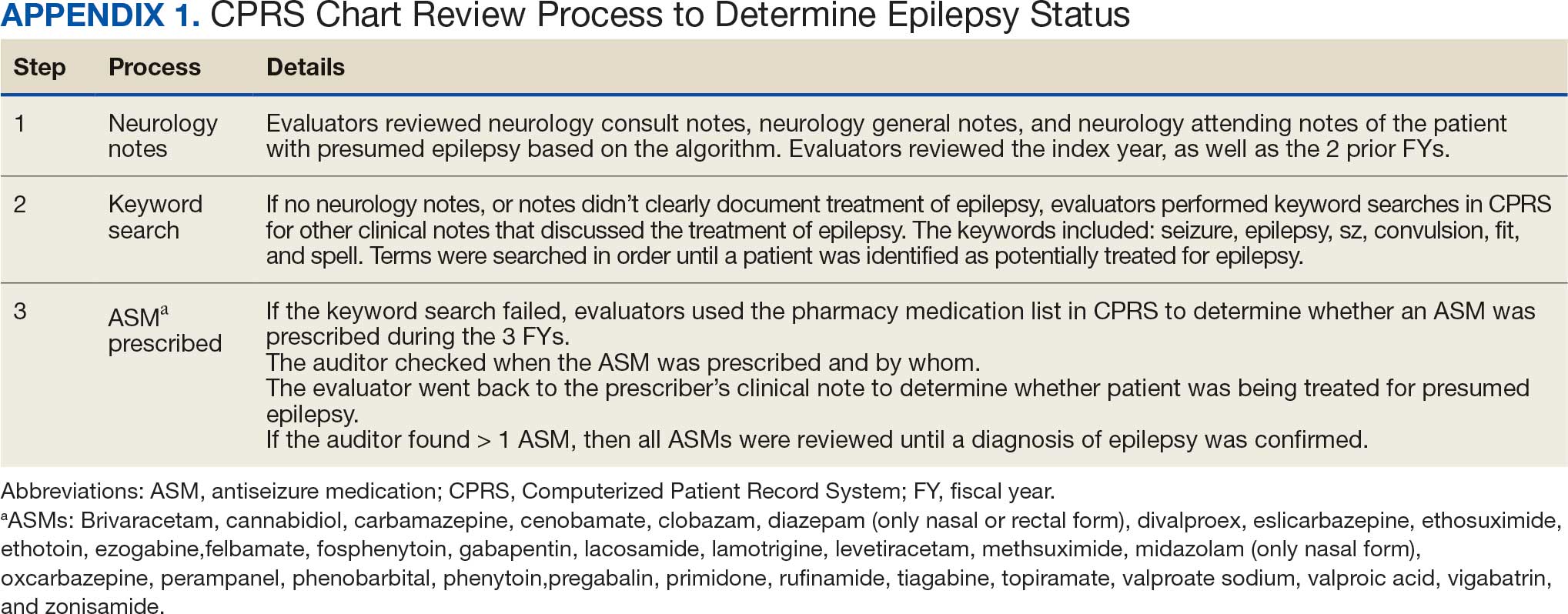

Definition. For a given index year and the preceding 2 years, any of following diagnosis codes on ≥ 1 clinical encounter are considered: 345.xx (epilepsy in ICD-9), 780.3x (other convulsions in ICD-9), G40.xxx (epilepsy in ICD-10), R40.4 (transient alteration of awareness), R56.1 (posttraumatic seizures), or R56.9 (unspecified convulsions). To reduce false positive rates, EEG clinic visits, which may include long-term monitoring, are excluded. Patients identified with ICD codes are then evaluated for an ASM prescription for ≥ 30 days during the index year. ASMs are listed in Appendix 1.

Validation. The development and validation of ICD-9 diagnosis codes crossmatched with an ASM prescription in the VHA has been published elsewhere.11 In FY 2017, after implementation of ICD-10 diagnostic codes, Tier 1 development and validation was performed in 2 phases. Even though Tier 1 study phases were conducted and completed during FY 2017, the patients for Tier 1 were identified from evaluation of FY 2016 data (October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2016). After the pilot analysis, the Tier 1 definition was implemented, and a chart review of 625 randomized patients was conducted at 5 sites for validation. Adequate preliminary data was not available to perform a sample size estimation for this study. Therefore, a practical target of 125 patients was set for Tier 1 from each site to obtain a final sample size of 625 patients. This second phase validated that the crossmatch of ICD-10 diagnosis codes with ASMs had a high PPV for identifying VWE.

Tiers 2 and 3

Definitions. For an index year, Tier 2 includes patients with ≥ 1 inpatient encounter documentation of either ICD-9 345.xx or ICD-10 G40.xxx, excluding EEG clinics. Tier 3 Includes patients who have had ≥ 2 outpatient encounters with diagnosis codes 345.xx or G40.xxx on 2 separate days, excluding EEG clinics. Tiers 2 and 3 do not require ASM prescriptions; this helps to identify VWEs who may be getting their medications outside of VHA or those who have received a new diagnosis.

Validations. Tiers 2 and 3 were included in the epilepsy identification algorithm in FY 2021 after validation was performed on a sample of 8 patients in each tier. Five patients were subsequently identified as having epilepsy in Tier 2 and 6 patients were identified in Tier 3. A more comprehensive validation of Tiers 2 and 3 was performed during FY 2022 that included patients at 5 sites seen during FY 2019 to FY 2022. Since yearly trends showed only about 8% of total patients were identified as having epilepsy through Tiers 2 and 3 we sought ≥ 20 patients per tier for the 5 sites for a total of 200 patients to ensure representation across the VHA. The final count was 126 patients for Tier 2 and 174 patients for Tier 3 (n = 300).

Gold Standard Criteria for Epilepsy Diagnosis

We used the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) definition of epilepsy for the validation of the 3 algorithm tiers. ILAE defines epilepsy as ≥ 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart or 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (≥ 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years.12

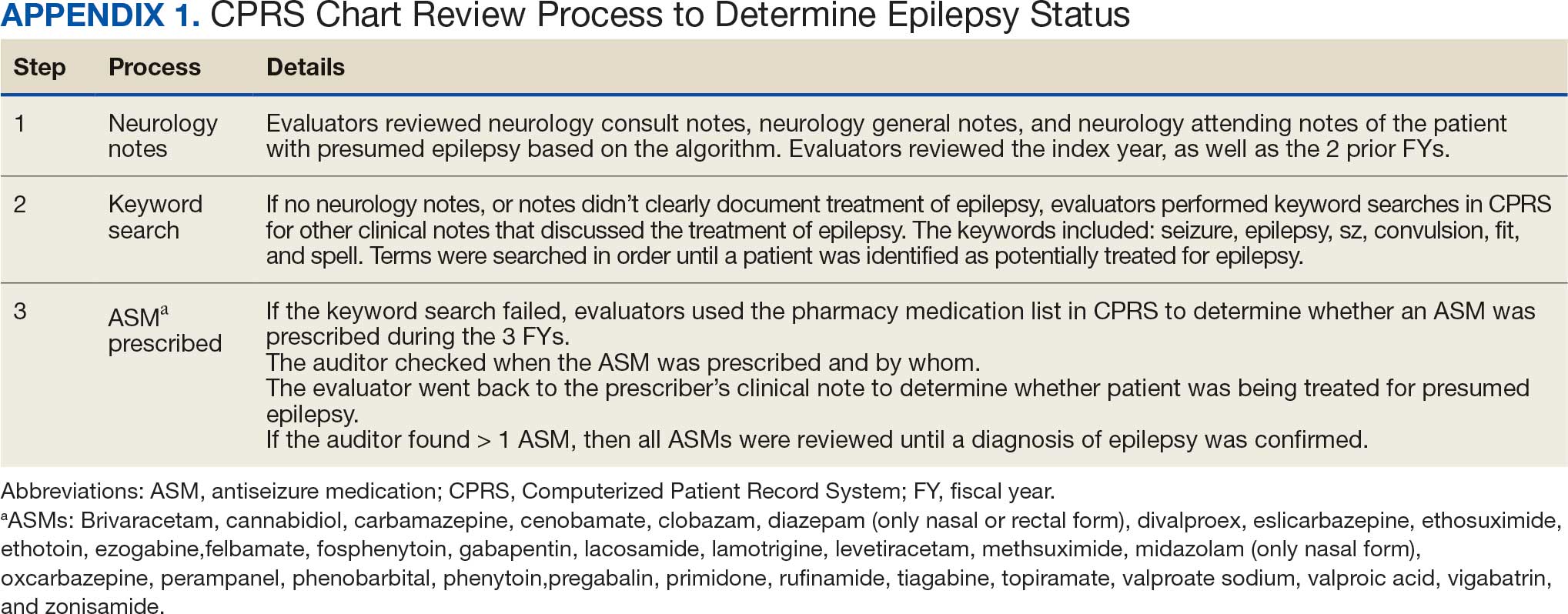

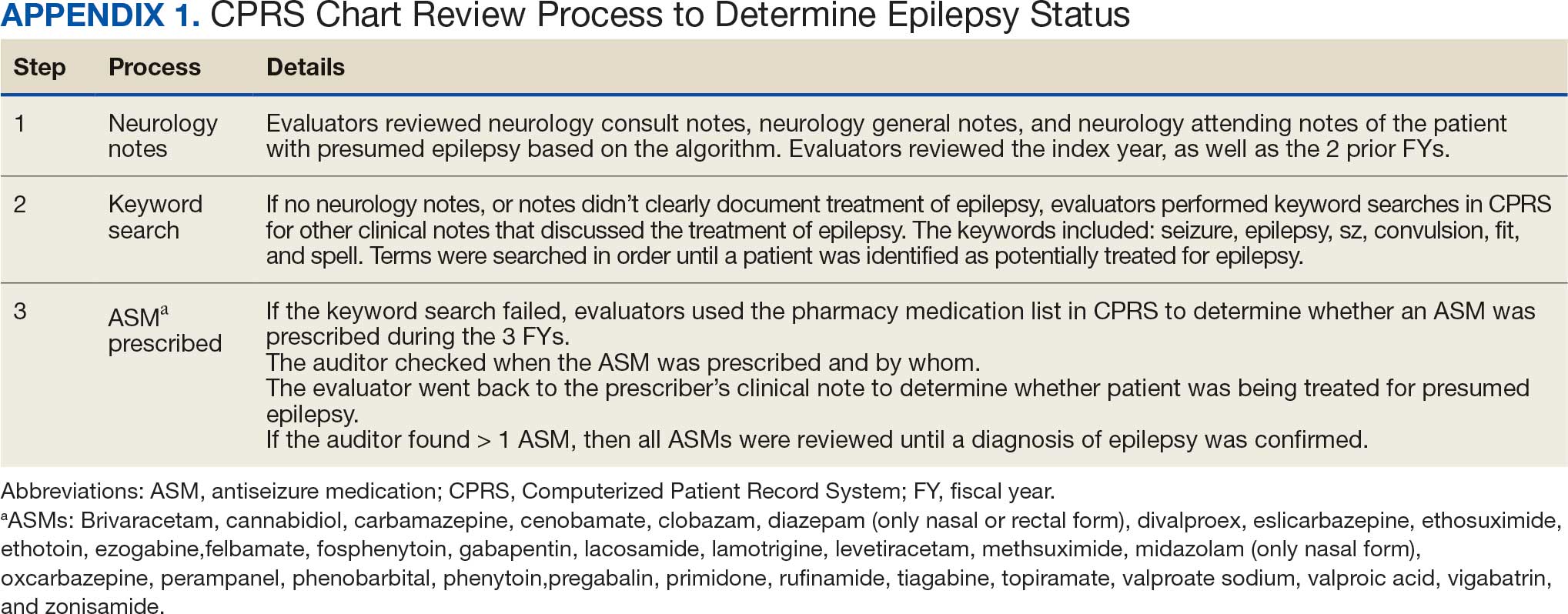

A standard protocol was provided to evaluators to identify patients using the VHA Computerized Patient Record System (Appendix 1). After review, evaluators categorized each patient in 1 of 4 ways: (1) Yes, definite: The patient’s health care practitioner (HCP) believes the patient has epilepsy and is treating with medication; (2) Yes, uncertain: The HCP has enough suspicion of epilepsy that a medication is prescribed, but uncertainty is expressed of the diagnosis; (3) No, definite: The HCP does not believe the patient has epilepsy and is therefore not treating with medication for seizure; (4) No, uncertain: The HCP is not treating with medication for epilepsy, because the diagnostic suspicion is not high enough, but there is suspicion for epilepsy.

As a quality improvement operational project, the Epilepsy National Program Office approved this validation project and determined that institutional review board approval was not required.

Statistical Analysis

Counts and percentages were computed for categories of epilepsy status. PPV of each tier was estimated with asymptotic 95% CIs.

Results

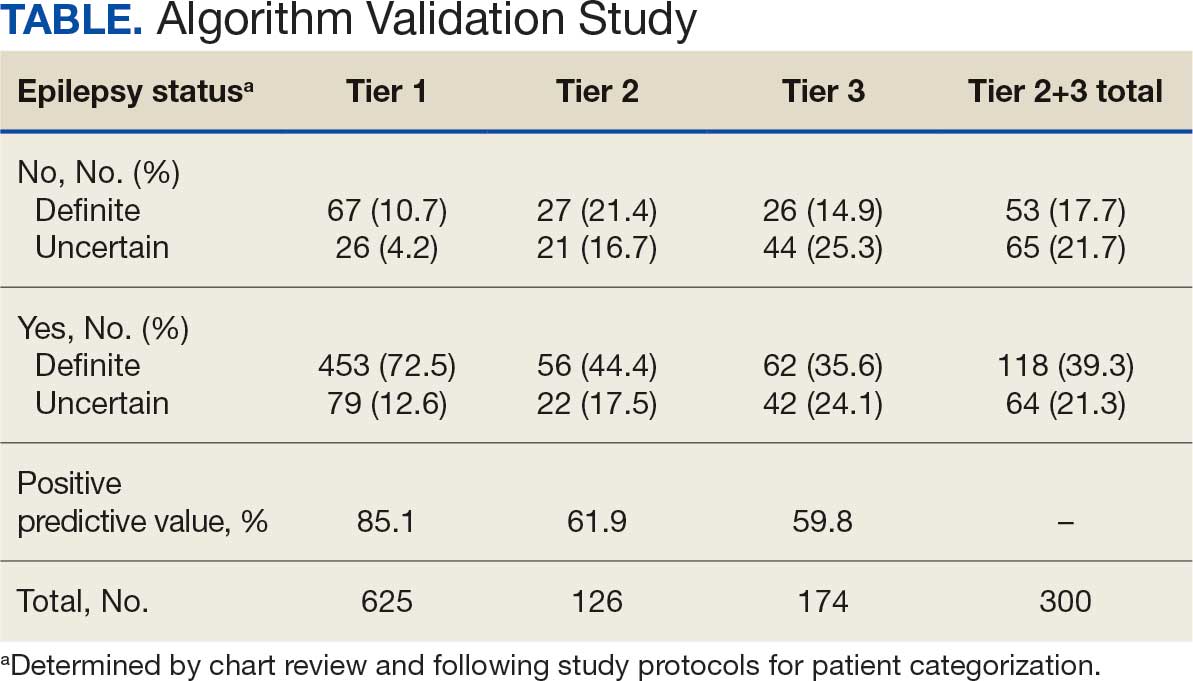

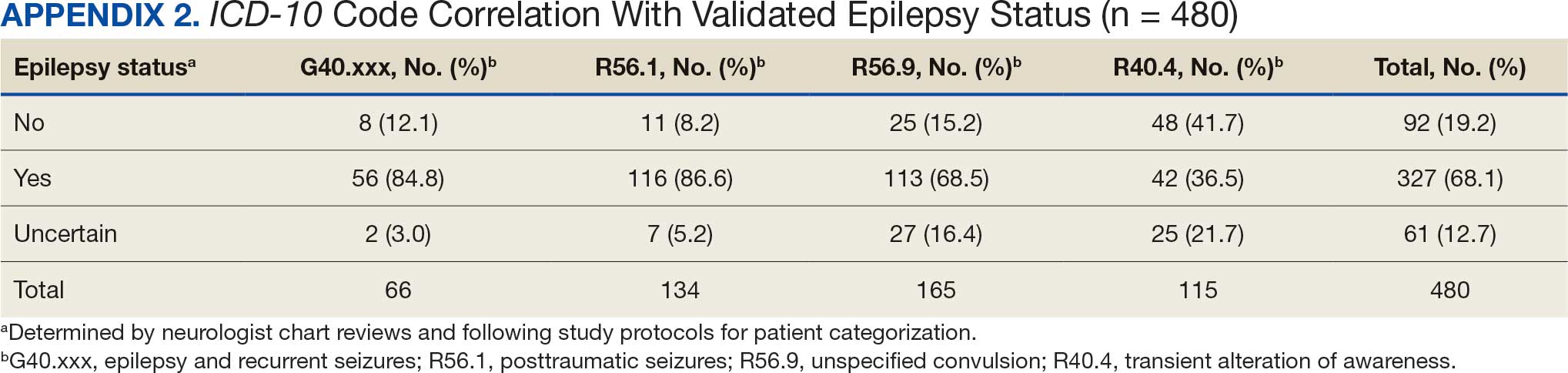

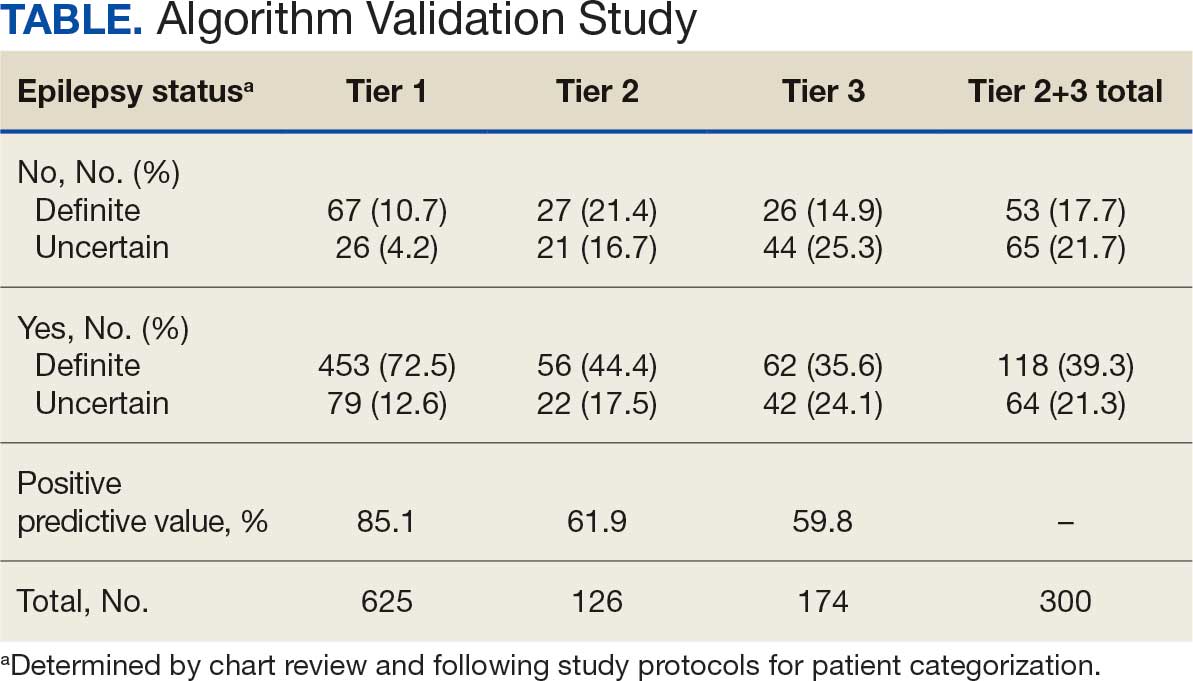

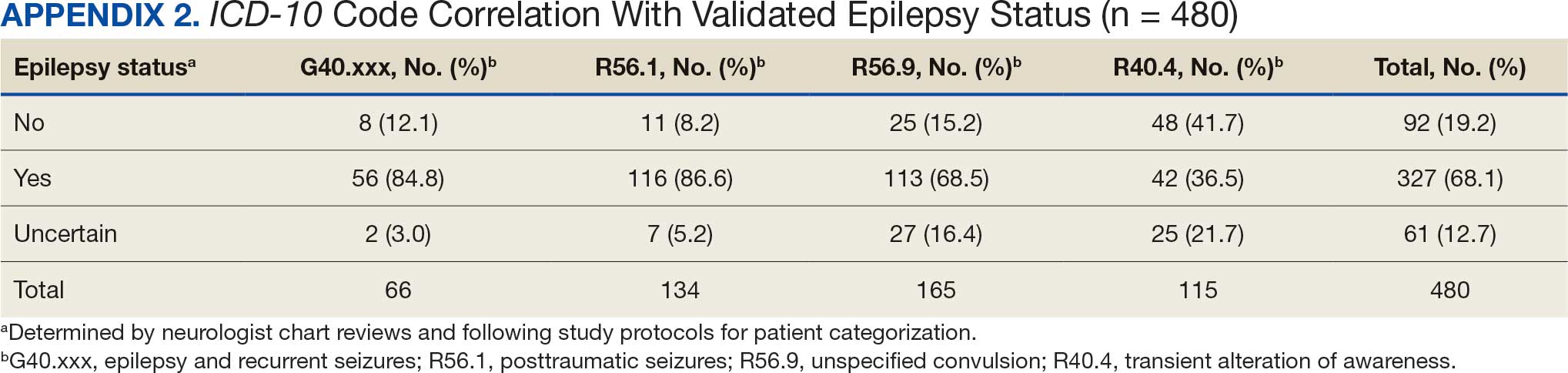

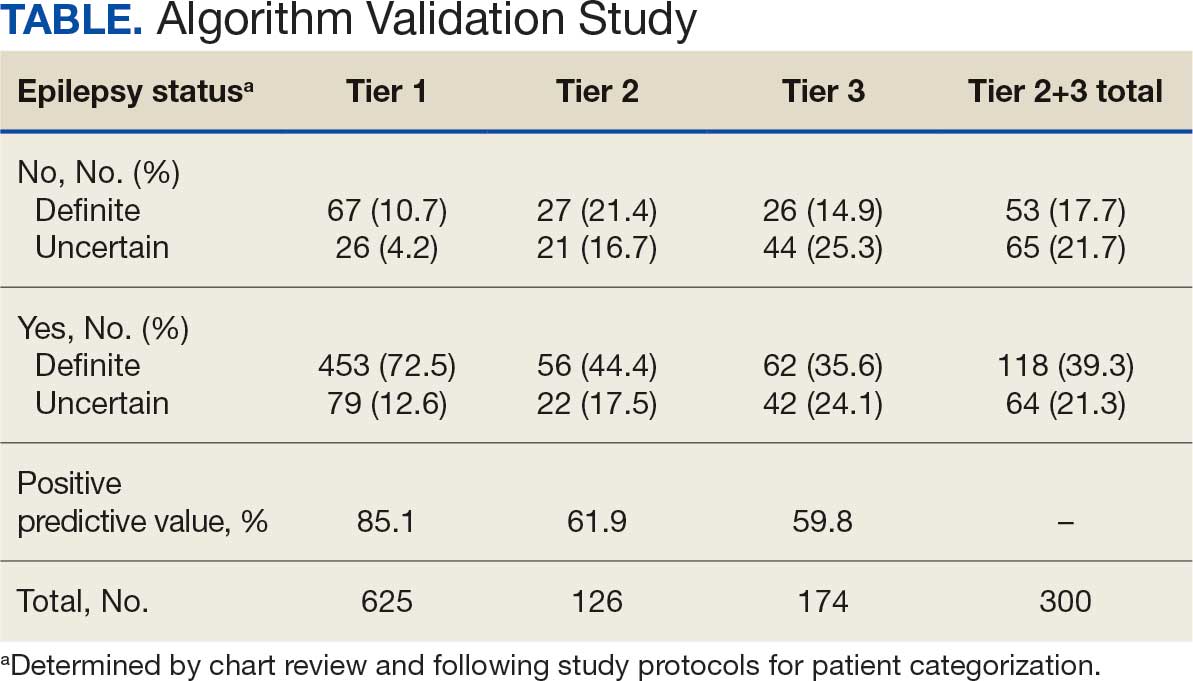

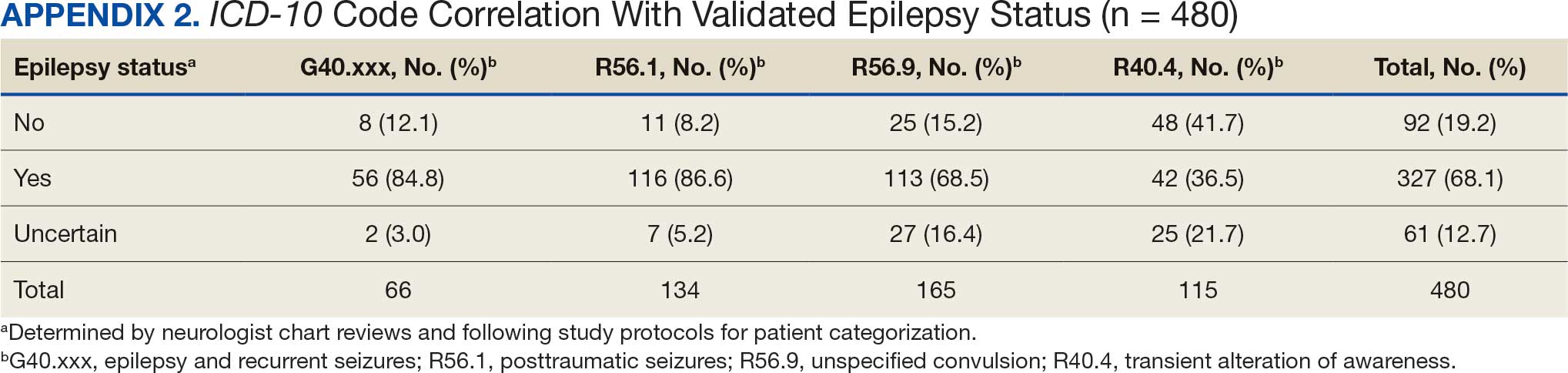

ICD-10 codes for 480 patients were evaluated in Tier 1 phase 1; 13.8% were documented with G40.xxx, 27.9% with R56.1, 34.4% with R56.9, and 24.0% with R40.4 (Appendix 2). In total, 68.1% fulfilled the criteria of epilepsy, 19.2% did not, and 12.7% were uncertain). From the validation of Tier 1 phase 2 (n = 625), the PPV of the algorithm for patients presumed to have epilepsy (definite and uncertain) was 85.1% (95% CI, 82.1%-87.8%) (Table).

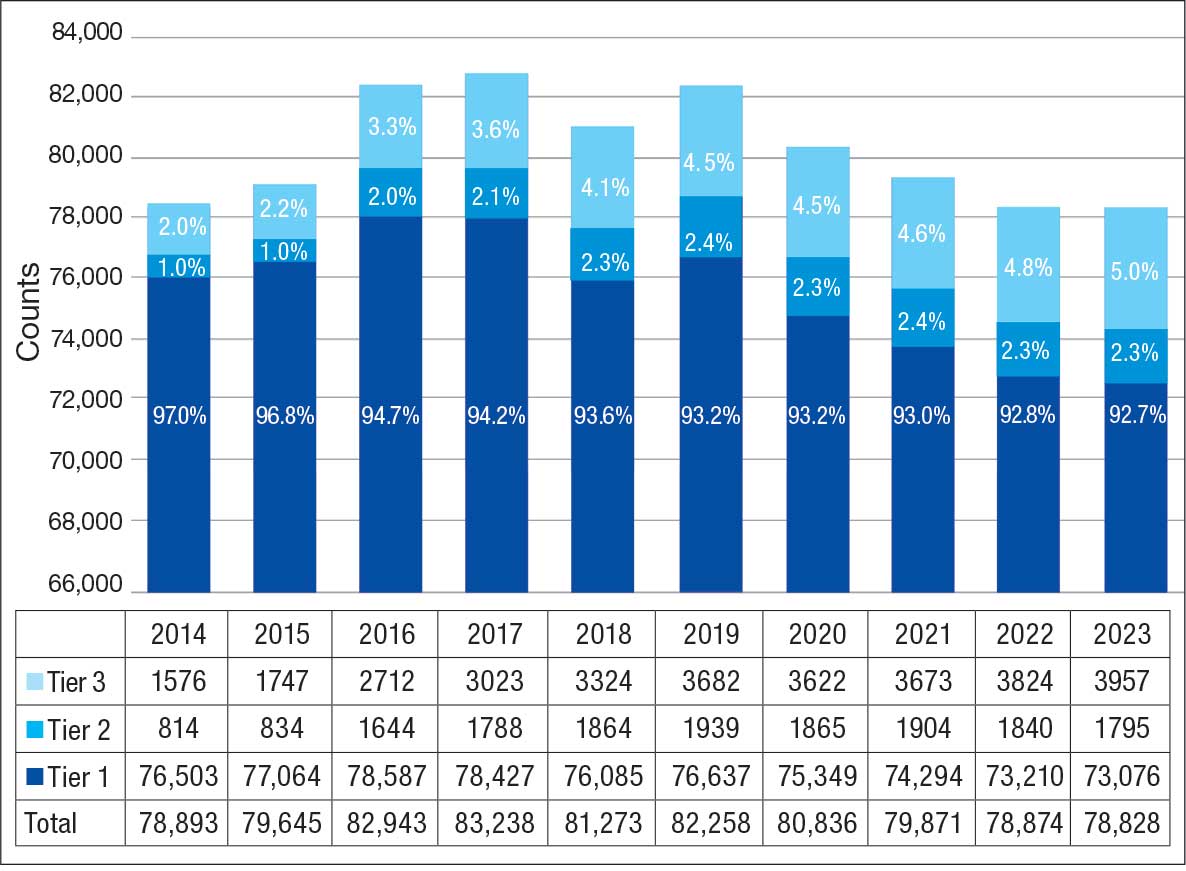

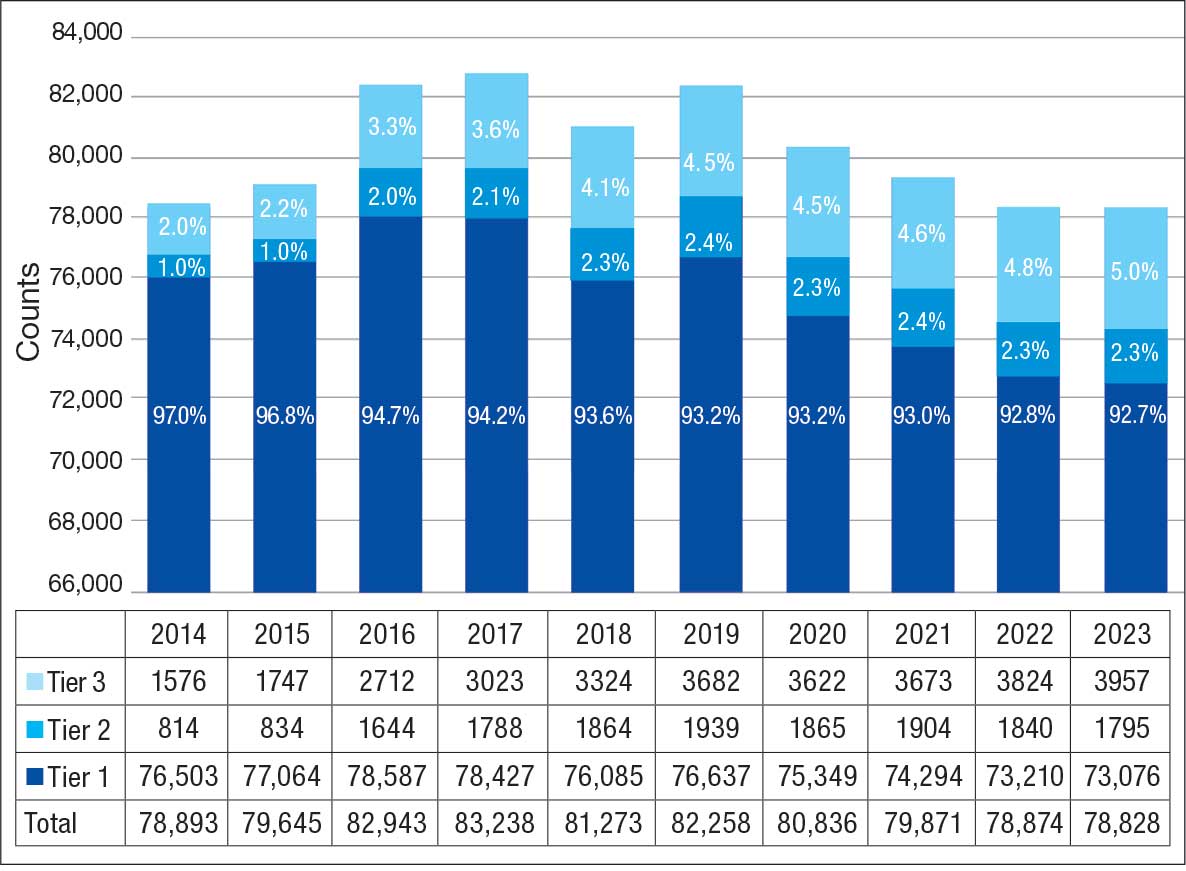

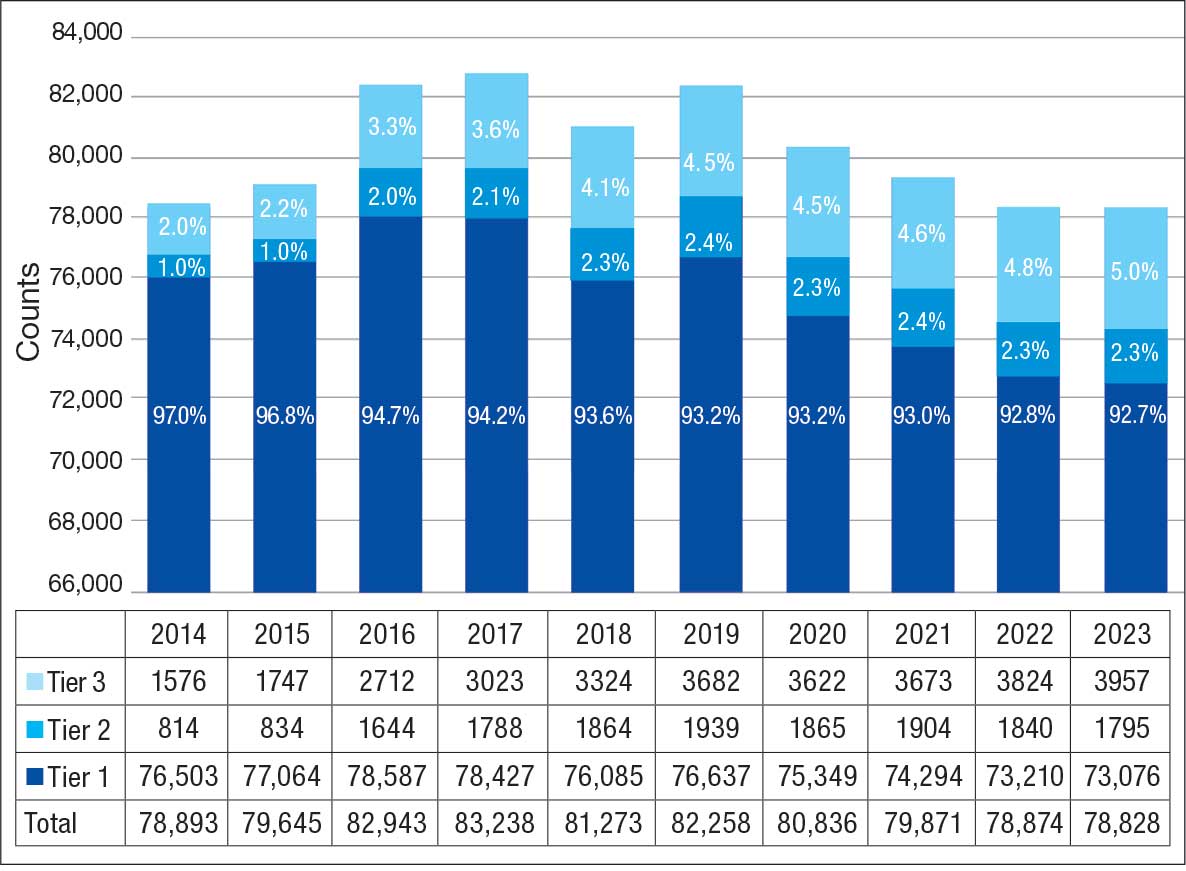

Of 300 patients evaluated, 126 (42.0%) were evaluated for Tier 2 with a PPV of 61.9% (95% CI, 53.4%-70.4%), and 174 (58.0%) patients were evaluated for Tier 3 with a PPV of 59.8% (95% CI, 52.5%-67.1%. The PPV of the algorithm for patients presumed to have epilepsy (definite and uncertain) were combined to calculate the PPV. Estimates of VHA VWE counts were computed for each tier from FY 2014 to FY 2023 using the VSSC Neurology Cube (Figure 2). For all years, > 92% patients were classified using the Tier 1 definition.

Discussion

The development and validation of the 3-tier diagnostic algorithm represents an important advancement in the surveillance and management of epilepsy among veterans within the VHA. The validation of this algorithm also demonstrates its practical utility in a large, integrated health care system.

Specific challenges were encountered when attempting to use pre-existing algorithms; these challenges included differences in the usage patterns of diagnostic codes and the patterns of ASM use within the VHA. These challenges prompted the need for a tailored approach, which led to the development of this algorithm. The inclusion of additional ICD-10 codes led to further revisions and subsequent validation. While many of the basic concepts of the algorithm, including ICD codes and ASMs, could work in other institutions, it would be wise for health care organizations to develop their own algorithms because of certain variables, including organizational size, patient demographics, common comorbidities, and the specific configurations of electronic health records and administrative data systems.

Studies have shown that ICD-10 codes for epilepsy (G40.* and/or R56.9) perform well in identifying epilepsy whether they are assigned by neurologists (sensitivity, 97.7%; specificity, 44.1%; PPV, 96.2%; negative predictive value, 57.7%), or in emergency department or hospital discharges (PPV, 75.5%).13,14 The pilot study of the algorithm’s Tier 1 development (phase 1) evaluated whether the selected ICD-10 diagnostic codes accurately included the VWE population within the VHA and revealed that while most codes (eg, epilepsy [G40.xxx]; posttraumatic seizures [R56.1]; and unspecified convulsions [R56.9]), had a low false positive rate (< 16%), the R40.4 code (transient alteration of awareness) had a higher false positivity of 42%. While this is not surprising given the broad spectrum of conditions that can manifest as transient alteration of awareness, it underscores the inherent challenges in diagnosing epilepsy using diagnosis codes.

In phase 2, the Tier 1 algorithm was validated as effective for identifying VWE in the VHA system, as its PPV was determined to be high (85%). In comparison, Tiers 2 and 3, whose criteria did not require data on VHA prescribed ASM use, had lower tiers of epilepsy predictability (PPV about 60% for both). This was thought to be acceptable because Tiers 2 and 3 represent a smaller population of the identified VWEs (about 8%). These VWEs may otherwise have been missed, partly because veterans are not required to get ASMs from the VHA.

Upon VHA implementation in FY 2021, this diagnostic algorithm exhibited significant clinical utility when integrated within the VSSC Neurology Cube. It facilitated an efficient approach to identifying VWEs using readily available databases. This led to better tracking of real-time epilepsy cases, which facilitated improving current resource allocation and targeted intervention strategies such as identification of drug-resistant epilepsy patients, optimizing strategies for telehealth and patient outreach for awareness of epilepsy care resources within VHA. Meanwhile, data acquired by the algorithm over the decade since its development (FY 2014 to FY 2023) contributed to more accurate epidemiologic information and identification of historic trends. Development of the algorithm represents one of the ways ECoEs have led to improved care for VWEs. ECoEs have been shown to improve health care for veterans in several metrics.15

A strength of this study is the rigorous multitiered validation process to confirm the diagnostic accuracy of ICD-10 codes against the gold standard ILAE definition of epilepsy to identify “definite” epilepsy cases within the VHA. The use of specific ICD codes further enhances the precision of epilepsy diagnoses. The inclusion of ASMs, which are sometimes prescribed for conditions other than epilepsy, could potentially inflate false positive rates.16

This study focused exclusively on the identification and validation of definite epilepsy cases within the VHA VSSC database, employing more stringent diagnostic criteria to ensure the highest level of certainty in ascertaining epilepsy. It is important to note there is a separate category of probable epilepsy, which involves a broader set of diagnostic criteria. While not covered in this study, probable epilepsy would be subject to future research and validation, which could provide insights into a wider spectrum of epilepsy diagnoses. Such future research could help refine the algorithm’s applicability and accuracy and potentially lead to more comprehensive surveillance and management strategies in clinical practice.

This study highlights the inherent challenges in leveraging administrative data for disease identification, particularly for conditions such as epilepsy, where diagnostic clarity can be complex. However, other conditions such as multiple sclerosis have noted similar success with the use of VHA administrative data for categorizing disease.17

Limitations

The algorithm discussed in this article is, in and of itself, generalizable. However, the validation process was unique to the VHA patient population, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Documentation practices and HCP attitudes within the VHA may differ from those in other health care settings. Identifying people with epilepsy can be challenging because of changing definitions of epilepsy over time. In addition to clinical evaluation, EEG and magnetic resonance imaging results, response to ASM treatment, and video-EEG monitoring of habitual events all can help establish the diagnosis. Therefore, studies may vary in how inclusive or exclusive the criteria are. ASMs such as gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate, and valproate are used to treat other conditions, including headaches, generalized pain, and mood disorders. Consequently, including these ASMs in the Tier 1 definition may have increased the false positive rate. Additional research is needed to evaluate whether excluding these ASMs from the algorithm based on specific criteria (eg, dose of ASM used) can further refine the algorithm to identify patients with epilepsy.

Further refinement of this algorithm may also occur as technology changes. Future electronic health records may allow better tracking of different epilepsy factors, the integration of additional diagnostic criteria, and the use of natural language processing or other forms of artificial intelligence.

Conclusions

This study presents a significant step forward in epilepsy surveillance within the VHA. The algorithm offers a robust tool for identifying VWEs with good PPVs, facilitating better resource allocation and targeted care. Despite its limitations, this research lays a foundation for future advancements in the management and understanding of epilepsy within large health care systems. Since this VHA algorithm is based on ASMs and ICD diagnosis codes from patient records, other large managed health care systems also may be able to adapt this algorithm to their data specifications.

- Kobau R, Luncheon C, Greenlund K. Active epilepsy prevalence among U.S. adults is 1.1% and differs by educational level-National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2021. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;142:109180. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109180

- GBD 2017 US Neurological Disorders Collaborators, Feigin VL, Vos T, et al. Burden of neurological disorders across the US from 1990-2017: a global burden of disease study. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:165-176. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4152

- Moura LMVR, Karakis I, Zack MM, et al. Drivers of US health care spending for persons with seizures and/or epilepsies, 2010-2018. Epilepsia. 2022;63:2144-2154. doi:10.1111/epi.17305

- Institute of Medicine. Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding. The National Academies Press; 2012. Accessed November 11, 2025. www.nap.edu/catalog/13379

- Mbizvo GK, Bennett KH, Schnier C, Simpson CR, Duncan SE, Chin RFM. The accuracy of using administrative healthcare data to identify epilepsy cases: A systematic review of validation studies. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1319-1335. doi:10.1111/epi.16547

- Montouris GD. How will primary care physicians, specialists, and managed care treat epilepsy in the new millennium? Neurology. 2000;55:S42-S44.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration: About VHA. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvements Act of 2008, S 2162, 110th Cong (2008). Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-bill/2162

- Rehman R, Kelly PR, Husain AM, Tran TT. Characteristics of Veterans diagnosed with seizures within Veterans Health Administration. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(7):751-762. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.10.0241

- Holden EW, Grossman E, Nguyen HT, et al. Developing a computer algorithm to identify epilepsy cases in managed care organizations. Dis Manag. 2005;8:1-14. doi:10.1089/dis.2005.8.1

- Rehman R, Everhart A, Frontera AT, et al. Implementation of an established algorithm and modifications for the identification of epilepsy patients in the Veterans Health Administration. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:284-290. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.09.012

- Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:475-482. doi:10.1111/epi.12550

- Smith JR, Jones FJS, Fureman BE, et al. Accuracy of ICD-10-CM claims-based definitions for epilepsy and seizure type. Epilepsy Res. 2020;166:106414. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106414

- Jetté N, Reid AY, Quan H, et al. How accurate is ICD coding for epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2010;51:62-69. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02201.x

- Kelly P, Chinta R, Privitera G. Do centers of excellence reduce health care costs? Evidence from the US Veterans Health Administration Centers for Epilepsy. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2015;34:18-29.

- Haneef Z, Rehman R, Husain AM. Association between standardized mortality ratio and utilization of care in US veterans with drug-resistant epilepsy compared with all US veterans and the US general population. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:879-887. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2290

- Culpepper WJ, Marrie RA, Langer-Gould A, et al. Validation of an algorithm for identifying MS cases in administrative health claims datasets. Neurology. 2019;92:e1016-e1028 doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007043

Epilepsy affects about 4.5 million people in the United States and 150,000 new individuals are diagnosed each year.1,2 In 2019, epilepsy-attributable health care spending for noninstitutionalized people was around $5.4 billion and total epilepsy-attributable and epilepsy or seizure health care-related costs totaled $54 billion.3

Accurate surveillance of epilepsy in large health care systems can potentially improve health care delivery and resource allocation. A 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report identified 13 recommendations to guide public health action on epilepsy, including validation of standard definitions for case ascertainment, identification of epilepsy through screening programs or protocols, and expansion of surveillance to better understand disease burden.4

A systematic review of validation studies concluded that it is reasonable to use administrative data to identify people with epilepsy in epidemiologic research. Combining The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for epilepsy (ICD-10, G40-41; ICD-9, 345) with antiseizure medications (ASMs) could provide high positive predictive values (PPVs) and combining symptoms codes for convulsions (ICD-10, R56; ICD-9, 780.3, 780.39) with ASMs could lead to high sensitivity.5 However, identifying individuals with epilepsy from administrative data in large managed health care organizations is challenging.6 The IOM report noted that large managed health care organizations presented varying incidence and prevalence estimates due to differing methodology, geographic area, demographics, and definitions of epilepsy.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated US health care system, providing care to > 9.1 million veterans.7 To improve the health and well-being of veterans with epilepsy (VWEs), a network of sites was established in 2008 called the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Epilepsy Centers of Excellence (ECoE). Subsequent to the creation of the ECoE, efforts were made to identify VWEs within VHA databases.8,9 Prior to fiscal year (FY) 2016, the ECoE adopted a modified version of a well-established epilepsy diagnostic algorithm developed by Holden et al for large managed care organizations.10 The original algorithm identified patients by cross-matching ASMs with ICD-9 codes for an index year. But it failed to capture a considerable number of stable patients with epilepsy in the VHA due to incomplete documentation, and had false positives due to inclusion of patients identified from diagnostic clinics. The modified algorithm the ECoE used prior to FY 2016 considered additional prior years and excluded encounters from diagnostic clinics. The result was an improvement in the sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm. Researchers evaluating 500 patients with epilepsy estimated that the modified algorithm had a PPV of 82.0% (95% CI, 78.6%-85.4%).11

After implementation of ICD-10 codes in the VHA in FY 2016, the task of reliably and efficiently identifying VWE led to a 3-tier algorithm. This article presents a validation of the different tiers of this algorithm after the implementation of ICD-10 diagnosis codes and summarizes the surveillance data collected over the years within the VHA showing the trends of epilepsy.

Methods

The VHA National Neurology office commissioned a Neurology Cube dashboard in FY 2021 in collaboration with VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) for reporting and surveillance of VWEs as a quality improvement initiative. The Neurology Cube uses a 3-tier system for identifying VWE in the VHA databases. VSSC programmers extract data from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and utilize Microsoft SQL Server and Microsoft Power BI for Neurology Cube reports. The 3-tier system identifies VWE and divides them into distinct groups. The first tier identifies VWE with the highest degree of confidence; Tiers 2 and 3 represent identification with successively lesser degrees of confidence (Figure 1).

Tier 1

Definition. For a given index year and the preceding 2 years, any of following diagnosis codes on ≥ 1 clinical encounter are considered: 345.xx (epilepsy in ICD-9), 780.3x (other convulsions in ICD-9), G40.xxx (epilepsy in ICD-10), R40.4 (transient alteration of awareness), R56.1 (posttraumatic seizures), or R56.9 (unspecified convulsions). To reduce false positive rates, EEG clinic visits, which may include long-term monitoring, are excluded. Patients identified with ICD codes are then evaluated for an ASM prescription for ≥ 30 days during the index year. ASMs are listed in Appendix 1.

Validation. The development and validation of ICD-9 diagnosis codes crossmatched with an ASM prescription in the VHA has been published elsewhere.11 In FY 2017, after implementation of ICD-10 diagnostic codes, Tier 1 development and validation was performed in 2 phases. Even though Tier 1 study phases were conducted and completed during FY 2017, the patients for Tier 1 were identified from evaluation of FY 2016 data (October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2016). After the pilot analysis, the Tier 1 definition was implemented, and a chart review of 625 randomized patients was conducted at 5 sites for validation. Adequate preliminary data was not available to perform a sample size estimation for this study. Therefore, a practical target of 125 patients was set for Tier 1 from each site to obtain a final sample size of 625 patients. This second phase validated that the crossmatch of ICD-10 diagnosis codes with ASMs had a high PPV for identifying VWE.

Tiers 2 and 3

Definitions. For an index year, Tier 2 includes patients with ≥ 1 inpatient encounter documentation of either ICD-9 345.xx or ICD-10 G40.xxx, excluding EEG clinics. Tier 3 Includes patients who have had ≥ 2 outpatient encounters with diagnosis codes 345.xx or G40.xxx on 2 separate days, excluding EEG clinics. Tiers 2 and 3 do not require ASM prescriptions; this helps to identify VWEs who may be getting their medications outside of VHA or those who have received a new diagnosis.

Validations. Tiers 2 and 3 were included in the epilepsy identification algorithm in FY 2021 after validation was performed on a sample of 8 patients in each tier. Five patients were subsequently identified as having epilepsy in Tier 2 and 6 patients were identified in Tier 3. A more comprehensive validation of Tiers 2 and 3 was performed during FY 2022 that included patients at 5 sites seen during FY 2019 to FY 2022. Since yearly trends showed only about 8% of total patients were identified as having epilepsy through Tiers 2 and 3 we sought ≥ 20 patients per tier for the 5 sites for a total of 200 patients to ensure representation across the VHA. The final count was 126 patients for Tier 2 and 174 patients for Tier 3 (n = 300).

Gold Standard Criteria for Epilepsy Diagnosis

We used the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) definition of epilepsy for the validation of the 3 algorithm tiers. ILAE defines epilepsy as ≥ 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart or 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (≥ 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years.12

A standard protocol was provided to evaluators to identify patients using the VHA Computerized Patient Record System (Appendix 1). After review, evaluators categorized each patient in 1 of 4 ways: (1) Yes, definite: The patient’s health care practitioner (HCP) believes the patient has epilepsy and is treating with medication; (2) Yes, uncertain: The HCP has enough suspicion of epilepsy that a medication is prescribed, but uncertainty is expressed of the diagnosis; (3) No, definite: The HCP does not believe the patient has epilepsy and is therefore not treating with medication for seizure; (4) No, uncertain: The HCP is not treating with medication for epilepsy, because the diagnostic suspicion is not high enough, but there is suspicion for epilepsy.

As a quality improvement operational project, the Epilepsy National Program Office approved this validation project and determined that institutional review board approval was not required.

Statistical Analysis

Counts and percentages were computed for categories of epilepsy status. PPV of each tier was estimated with asymptotic 95% CIs.

Results

ICD-10 codes for 480 patients were evaluated in Tier 1 phase 1; 13.8% were documented with G40.xxx, 27.9% with R56.1, 34.4% with R56.9, and 24.0% with R40.4 (Appendix 2). In total, 68.1% fulfilled the criteria of epilepsy, 19.2% did not, and 12.7% were uncertain). From the validation of Tier 1 phase 2 (n = 625), the PPV of the algorithm for patients presumed to have epilepsy (definite and uncertain) was 85.1% (95% CI, 82.1%-87.8%) (Table).

Of 300 patients evaluated, 126 (42.0%) were evaluated for Tier 2 with a PPV of 61.9% (95% CI, 53.4%-70.4%), and 174 (58.0%) patients were evaluated for Tier 3 with a PPV of 59.8% (95% CI, 52.5%-67.1%. The PPV of the algorithm for patients presumed to have epilepsy (definite and uncertain) were combined to calculate the PPV. Estimates of VHA VWE counts were computed for each tier from FY 2014 to FY 2023 using the VSSC Neurology Cube (Figure 2). For all years, > 92% patients were classified using the Tier 1 definition.

Discussion

The development and validation of the 3-tier diagnostic algorithm represents an important advancement in the surveillance and management of epilepsy among veterans within the VHA. The validation of this algorithm also demonstrates its practical utility in a large, integrated health care system.

Specific challenges were encountered when attempting to use pre-existing algorithms; these challenges included differences in the usage patterns of diagnostic codes and the patterns of ASM use within the VHA. These challenges prompted the need for a tailored approach, which led to the development of this algorithm. The inclusion of additional ICD-10 codes led to further revisions and subsequent validation. While many of the basic concepts of the algorithm, including ICD codes and ASMs, could work in other institutions, it would be wise for health care organizations to develop their own algorithms because of certain variables, including organizational size, patient demographics, common comorbidities, and the specific configurations of electronic health records and administrative data systems.

Studies have shown that ICD-10 codes for epilepsy (G40.* and/or R56.9) perform well in identifying epilepsy whether they are assigned by neurologists (sensitivity, 97.7%; specificity, 44.1%; PPV, 96.2%; negative predictive value, 57.7%), or in emergency department or hospital discharges (PPV, 75.5%).13,14 The pilot study of the algorithm’s Tier 1 development (phase 1) evaluated whether the selected ICD-10 diagnostic codes accurately included the VWE population within the VHA and revealed that while most codes (eg, epilepsy [G40.xxx]; posttraumatic seizures [R56.1]; and unspecified convulsions [R56.9]), had a low false positive rate (< 16%), the R40.4 code (transient alteration of awareness) had a higher false positivity of 42%. While this is not surprising given the broad spectrum of conditions that can manifest as transient alteration of awareness, it underscores the inherent challenges in diagnosing epilepsy using diagnosis codes.

In phase 2, the Tier 1 algorithm was validated as effective for identifying VWE in the VHA system, as its PPV was determined to be high (85%). In comparison, Tiers 2 and 3, whose criteria did not require data on VHA prescribed ASM use, had lower tiers of epilepsy predictability (PPV about 60% for both). This was thought to be acceptable because Tiers 2 and 3 represent a smaller population of the identified VWEs (about 8%). These VWEs may otherwise have been missed, partly because veterans are not required to get ASMs from the VHA.

Upon VHA implementation in FY 2021, this diagnostic algorithm exhibited significant clinical utility when integrated within the VSSC Neurology Cube. It facilitated an efficient approach to identifying VWEs using readily available databases. This led to better tracking of real-time epilepsy cases, which facilitated improving current resource allocation and targeted intervention strategies such as identification of drug-resistant epilepsy patients, optimizing strategies for telehealth and patient outreach for awareness of epilepsy care resources within VHA. Meanwhile, data acquired by the algorithm over the decade since its development (FY 2014 to FY 2023) contributed to more accurate epidemiologic information and identification of historic trends. Development of the algorithm represents one of the ways ECoEs have led to improved care for VWEs. ECoEs have been shown to improve health care for veterans in several metrics.15

A strength of this study is the rigorous multitiered validation process to confirm the diagnostic accuracy of ICD-10 codes against the gold standard ILAE definition of epilepsy to identify “definite” epilepsy cases within the VHA. The use of specific ICD codes further enhances the precision of epilepsy diagnoses. The inclusion of ASMs, which are sometimes prescribed for conditions other than epilepsy, could potentially inflate false positive rates.16

This study focused exclusively on the identification and validation of definite epilepsy cases within the VHA VSSC database, employing more stringent diagnostic criteria to ensure the highest level of certainty in ascertaining epilepsy. It is important to note there is a separate category of probable epilepsy, which involves a broader set of diagnostic criteria. While not covered in this study, probable epilepsy would be subject to future research and validation, which could provide insights into a wider spectrum of epilepsy diagnoses. Such future research could help refine the algorithm’s applicability and accuracy and potentially lead to more comprehensive surveillance and management strategies in clinical practice.

This study highlights the inherent challenges in leveraging administrative data for disease identification, particularly for conditions such as epilepsy, where diagnostic clarity can be complex. However, other conditions such as multiple sclerosis have noted similar success with the use of VHA administrative data for categorizing disease.17

Limitations

The algorithm discussed in this article is, in and of itself, generalizable. However, the validation process was unique to the VHA patient population, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Documentation practices and HCP attitudes within the VHA may differ from those in other health care settings. Identifying people with epilepsy can be challenging because of changing definitions of epilepsy over time. In addition to clinical evaluation, EEG and magnetic resonance imaging results, response to ASM treatment, and video-EEG monitoring of habitual events all can help establish the diagnosis. Therefore, studies may vary in how inclusive or exclusive the criteria are. ASMs such as gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate, and valproate are used to treat other conditions, including headaches, generalized pain, and mood disorders. Consequently, including these ASMs in the Tier 1 definition may have increased the false positive rate. Additional research is needed to evaluate whether excluding these ASMs from the algorithm based on specific criteria (eg, dose of ASM used) can further refine the algorithm to identify patients with epilepsy.

Further refinement of this algorithm may also occur as technology changes. Future electronic health records may allow better tracking of different epilepsy factors, the integration of additional diagnostic criteria, and the use of natural language processing or other forms of artificial intelligence.

Conclusions

This study presents a significant step forward in epilepsy surveillance within the VHA. The algorithm offers a robust tool for identifying VWEs with good PPVs, facilitating better resource allocation and targeted care. Despite its limitations, this research lays a foundation for future advancements in the management and understanding of epilepsy within large health care systems. Since this VHA algorithm is based on ASMs and ICD diagnosis codes from patient records, other large managed health care systems also may be able to adapt this algorithm to their data specifications.

Epilepsy affects about 4.5 million people in the United States and 150,000 new individuals are diagnosed each year.1,2 In 2019, epilepsy-attributable health care spending for noninstitutionalized people was around $5.4 billion and total epilepsy-attributable and epilepsy or seizure health care-related costs totaled $54 billion.3

Accurate surveillance of epilepsy in large health care systems can potentially improve health care delivery and resource allocation. A 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report identified 13 recommendations to guide public health action on epilepsy, including validation of standard definitions for case ascertainment, identification of epilepsy through screening programs or protocols, and expansion of surveillance to better understand disease burden.4

A systematic review of validation studies concluded that it is reasonable to use administrative data to identify people with epilepsy in epidemiologic research. Combining The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for epilepsy (ICD-10, G40-41; ICD-9, 345) with antiseizure medications (ASMs) could provide high positive predictive values (PPVs) and combining symptoms codes for convulsions (ICD-10, R56; ICD-9, 780.3, 780.39) with ASMs could lead to high sensitivity.5 However, identifying individuals with epilepsy from administrative data in large managed health care organizations is challenging.6 The IOM report noted that large managed health care organizations presented varying incidence and prevalence estimates due to differing methodology, geographic area, demographics, and definitions of epilepsy.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated US health care system, providing care to > 9.1 million veterans.7 To improve the health and well-being of veterans with epilepsy (VWEs), a network of sites was established in 2008 called the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Epilepsy Centers of Excellence (ECoE). Subsequent to the creation of the ECoE, efforts were made to identify VWEs within VHA databases.8,9 Prior to fiscal year (FY) 2016, the ECoE adopted a modified version of a well-established epilepsy diagnostic algorithm developed by Holden et al for large managed care organizations.10 The original algorithm identified patients by cross-matching ASMs with ICD-9 codes for an index year. But it failed to capture a considerable number of stable patients with epilepsy in the VHA due to incomplete documentation, and had false positives due to inclusion of patients identified from diagnostic clinics. The modified algorithm the ECoE used prior to FY 2016 considered additional prior years and excluded encounters from diagnostic clinics. The result was an improvement in the sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm. Researchers evaluating 500 patients with epilepsy estimated that the modified algorithm had a PPV of 82.0% (95% CI, 78.6%-85.4%).11

After implementation of ICD-10 codes in the VHA in FY 2016, the task of reliably and efficiently identifying VWE led to a 3-tier algorithm. This article presents a validation of the different tiers of this algorithm after the implementation of ICD-10 diagnosis codes and summarizes the surveillance data collected over the years within the VHA showing the trends of epilepsy.

Methods

The VHA National Neurology office commissioned a Neurology Cube dashboard in FY 2021 in collaboration with VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) for reporting and surveillance of VWEs as a quality improvement initiative. The Neurology Cube uses a 3-tier system for identifying VWE in the VHA databases. VSSC programmers extract data from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and utilize Microsoft SQL Server and Microsoft Power BI for Neurology Cube reports. The 3-tier system identifies VWE and divides them into distinct groups. The first tier identifies VWE with the highest degree of confidence; Tiers 2 and 3 represent identification with successively lesser degrees of confidence (Figure 1).

Tier 1

Definition. For a given index year and the preceding 2 years, any of following diagnosis codes on ≥ 1 clinical encounter are considered: 345.xx (epilepsy in ICD-9), 780.3x (other convulsions in ICD-9), G40.xxx (epilepsy in ICD-10), R40.4 (transient alteration of awareness), R56.1 (posttraumatic seizures), or R56.9 (unspecified convulsions). To reduce false positive rates, EEG clinic visits, which may include long-term monitoring, are excluded. Patients identified with ICD codes are then evaluated for an ASM prescription for ≥ 30 days during the index year. ASMs are listed in Appendix 1.

Validation. The development and validation of ICD-9 diagnosis codes crossmatched with an ASM prescription in the VHA has been published elsewhere.11 In FY 2017, after implementation of ICD-10 diagnostic codes, Tier 1 development and validation was performed in 2 phases. Even though Tier 1 study phases were conducted and completed during FY 2017, the patients for Tier 1 were identified from evaluation of FY 2016 data (October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2016). After the pilot analysis, the Tier 1 definition was implemented, and a chart review of 625 randomized patients was conducted at 5 sites for validation. Adequate preliminary data was not available to perform a sample size estimation for this study. Therefore, a practical target of 125 patients was set for Tier 1 from each site to obtain a final sample size of 625 patients. This second phase validated that the crossmatch of ICD-10 diagnosis codes with ASMs had a high PPV for identifying VWE.

Tiers 2 and 3

Definitions. For an index year, Tier 2 includes patients with ≥ 1 inpatient encounter documentation of either ICD-9 345.xx or ICD-10 G40.xxx, excluding EEG clinics. Tier 3 Includes patients who have had ≥ 2 outpatient encounters with diagnosis codes 345.xx or G40.xxx on 2 separate days, excluding EEG clinics. Tiers 2 and 3 do not require ASM prescriptions; this helps to identify VWEs who may be getting their medications outside of VHA or those who have received a new diagnosis.

Validations. Tiers 2 and 3 were included in the epilepsy identification algorithm in FY 2021 after validation was performed on a sample of 8 patients in each tier. Five patients were subsequently identified as having epilepsy in Tier 2 and 6 patients were identified in Tier 3. A more comprehensive validation of Tiers 2 and 3 was performed during FY 2022 that included patients at 5 sites seen during FY 2019 to FY 2022. Since yearly trends showed only about 8% of total patients were identified as having epilepsy through Tiers 2 and 3 we sought ≥ 20 patients per tier for the 5 sites for a total of 200 patients to ensure representation across the VHA. The final count was 126 patients for Tier 2 and 174 patients for Tier 3 (n = 300).

Gold Standard Criteria for Epilepsy Diagnosis

We used the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) definition of epilepsy for the validation of the 3 algorithm tiers. ILAE defines epilepsy as ≥ 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart or 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (≥ 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years.12

A standard protocol was provided to evaluators to identify patients using the VHA Computerized Patient Record System (Appendix 1). After review, evaluators categorized each patient in 1 of 4 ways: (1) Yes, definite: The patient’s health care practitioner (HCP) believes the patient has epilepsy and is treating with medication; (2) Yes, uncertain: The HCP has enough suspicion of epilepsy that a medication is prescribed, but uncertainty is expressed of the diagnosis; (3) No, definite: The HCP does not believe the patient has epilepsy and is therefore not treating with medication for seizure; (4) No, uncertain: The HCP is not treating with medication for epilepsy, because the diagnostic suspicion is not high enough, but there is suspicion for epilepsy.

As a quality improvement operational project, the Epilepsy National Program Office approved this validation project and determined that institutional review board approval was not required.

Statistical Analysis

Counts and percentages were computed for categories of epilepsy status. PPV of each tier was estimated with asymptotic 95% CIs.

Results

ICD-10 codes for 480 patients were evaluated in Tier 1 phase 1; 13.8% were documented with G40.xxx, 27.9% with R56.1, 34.4% with R56.9, and 24.0% with R40.4 (Appendix 2). In total, 68.1% fulfilled the criteria of epilepsy, 19.2% did not, and 12.7% were uncertain). From the validation of Tier 1 phase 2 (n = 625), the PPV of the algorithm for patients presumed to have epilepsy (definite and uncertain) was 85.1% (95% CI, 82.1%-87.8%) (Table).

Of 300 patients evaluated, 126 (42.0%) were evaluated for Tier 2 with a PPV of 61.9% (95% CI, 53.4%-70.4%), and 174 (58.0%) patients were evaluated for Tier 3 with a PPV of 59.8% (95% CI, 52.5%-67.1%. The PPV of the algorithm for patients presumed to have epilepsy (definite and uncertain) were combined to calculate the PPV. Estimates of VHA VWE counts were computed for each tier from FY 2014 to FY 2023 using the VSSC Neurology Cube (Figure 2). For all years, > 92% patients were classified using the Tier 1 definition.

Discussion

The development and validation of the 3-tier diagnostic algorithm represents an important advancement in the surveillance and management of epilepsy among veterans within the VHA. The validation of this algorithm also demonstrates its practical utility in a large, integrated health care system.

Specific challenges were encountered when attempting to use pre-existing algorithms; these challenges included differences in the usage patterns of diagnostic codes and the patterns of ASM use within the VHA. These challenges prompted the need for a tailored approach, which led to the development of this algorithm. The inclusion of additional ICD-10 codes led to further revisions and subsequent validation. While many of the basic concepts of the algorithm, including ICD codes and ASMs, could work in other institutions, it would be wise for health care organizations to develop their own algorithms because of certain variables, including organizational size, patient demographics, common comorbidities, and the specific configurations of electronic health records and administrative data systems.

Studies have shown that ICD-10 codes for epilepsy (G40.* and/or R56.9) perform well in identifying epilepsy whether they are assigned by neurologists (sensitivity, 97.7%; specificity, 44.1%; PPV, 96.2%; negative predictive value, 57.7%), or in emergency department or hospital discharges (PPV, 75.5%).13,14 The pilot study of the algorithm’s Tier 1 development (phase 1) evaluated whether the selected ICD-10 diagnostic codes accurately included the VWE population within the VHA and revealed that while most codes (eg, epilepsy [G40.xxx]; posttraumatic seizures [R56.1]; and unspecified convulsions [R56.9]), had a low false positive rate (< 16%), the R40.4 code (transient alteration of awareness) had a higher false positivity of 42%. While this is not surprising given the broad spectrum of conditions that can manifest as transient alteration of awareness, it underscores the inherent challenges in diagnosing epilepsy using diagnosis codes.

In phase 2, the Tier 1 algorithm was validated as effective for identifying VWE in the VHA system, as its PPV was determined to be high (85%). In comparison, Tiers 2 and 3, whose criteria did not require data on VHA prescribed ASM use, had lower tiers of epilepsy predictability (PPV about 60% for both). This was thought to be acceptable because Tiers 2 and 3 represent a smaller population of the identified VWEs (about 8%). These VWEs may otherwise have been missed, partly because veterans are not required to get ASMs from the VHA.

Upon VHA implementation in FY 2021, this diagnostic algorithm exhibited significant clinical utility when integrated within the VSSC Neurology Cube. It facilitated an efficient approach to identifying VWEs using readily available databases. This led to better tracking of real-time epilepsy cases, which facilitated improving current resource allocation and targeted intervention strategies such as identification of drug-resistant epilepsy patients, optimizing strategies for telehealth and patient outreach for awareness of epilepsy care resources within VHA. Meanwhile, data acquired by the algorithm over the decade since its development (FY 2014 to FY 2023) contributed to more accurate epidemiologic information and identification of historic trends. Development of the algorithm represents one of the ways ECoEs have led to improved care for VWEs. ECoEs have been shown to improve health care for veterans in several metrics.15

A strength of this study is the rigorous multitiered validation process to confirm the diagnostic accuracy of ICD-10 codes against the gold standard ILAE definition of epilepsy to identify “definite” epilepsy cases within the VHA. The use of specific ICD codes further enhances the precision of epilepsy diagnoses. The inclusion of ASMs, which are sometimes prescribed for conditions other than epilepsy, could potentially inflate false positive rates.16

This study focused exclusively on the identification and validation of definite epilepsy cases within the VHA VSSC database, employing more stringent diagnostic criteria to ensure the highest level of certainty in ascertaining epilepsy. It is important to note there is a separate category of probable epilepsy, which involves a broader set of diagnostic criteria. While not covered in this study, probable epilepsy would be subject to future research and validation, which could provide insights into a wider spectrum of epilepsy diagnoses. Such future research could help refine the algorithm’s applicability and accuracy and potentially lead to more comprehensive surveillance and management strategies in clinical practice.

This study highlights the inherent challenges in leveraging administrative data for disease identification, particularly for conditions such as epilepsy, where diagnostic clarity can be complex. However, other conditions such as multiple sclerosis have noted similar success with the use of VHA administrative data for categorizing disease.17

Limitations

The algorithm discussed in this article is, in and of itself, generalizable. However, the validation process was unique to the VHA patient population, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Documentation practices and HCP attitudes within the VHA may differ from those in other health care settings. Identifying people with epilepsy can be challenging because of changing definitions of epilepsy over time. In addition to clinical evaluation, EEG and magnetic resonance imaging results, response to ASM treatment, and video-EEG monitoring of habitual events all can help establish the diagnosis. Therefore, studies may vary in how inclusive or exclusive the criteria are. ASMs such as gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate, and valproate are used to treat other conditions, including headaches, generalized pain, and mood disorders. Consequently, including these ASMs in the Tier 1 definition may have increased the false positive rate. Additional research is needed to evaluate whether excluding these ASMs from the algorithm based on specific criteria (eg, dose of ASM used) can further refine the algorithm to identify patients with epilepsy.

Further refinement of this algorithm may also occur as technology changes. Future electronic health records may allow better tracking of different epilepsy factors, the integration of additional diagnostic criteria, and the use of natural language processing or other forms of artificial intelligence.

Conclusions

This study presents a significant step forward in epilepsy surveillance within the VHA. The algorithm offers a robust tool for identifying VWEs with good PPVs, facilitating better resource allocation and targeted care. Despite its limitations, this research lays a foundation for future advancements in the management and understanding of epilepsy within large health care systems. Since this VHA algorithm is based on ASMs and ICD diagnosis codes from patient records, other large managed health care systems also may be able to adapt this algorithm to their data specifications.

- Kobau R, Luncheon C, Greenlund K. Active epilepsy prevalence among U.S. adults is 1.1% and differs by educational level-National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2021. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;142:109180. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109180

- GBD 2017 US Neurological Disorders Collaborators, Feigin VL, Vos T, et al. Burden of neurological disorders across the US from 1990-2017: a global burden of disease study. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:165-176. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4152

- Moura LMVR, Karakis I, Zack MM, et al. Drivers of US health care spending for persons with seizures and/or epilepsies, 2010-2018. Epilepsia. 2022;63:2144-2154. doi:10.1111/epi.17305

- Institute of Medicine. Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding. The National Academies Press; 2012. Accessed November 11, 2025. www.nap.edu/catalog/13379

- Mbizvo GK, Bennett KH, Schnier C, Simpson CR, Duncan SE, Chin RFM. The accuracy of using administrative healthcare data to identify epilepsy cases: A systematic review of validation studies. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1319-1335. doi:10.1111/epi.16547

- Montouris GD. How will primary care physicians, specialists, and managed care treat epilepsy in the new millennium? Neurology. 2000;55:S42-S44.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration: About VHA. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvements Act of 2008, S 2162, 110th Cong (2008). Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-bill/2162

- Rehman R, Kelly PR, Husain AM, Tran TT. Characteristics of Veterans diagnosed with seizures within Veterans Health Administration. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(7):751-762. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.10.0241

- Holden EW, Grossman E, Nguyen HT, et al. Developing a computer algorithm to identify epilepsy cases in managed care organizations. Dis Manag. 2005;8:1-14. doi:10.1089/dis.2005.8.1

- Rehman R, Everhart A, Frontera AT, et al. Implementation of an established algorithm and modifications for the identification of epilepsy patients in the Veterans Health Administration. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:284-290. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.09.012

- Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:475-482. doi:10.1111/epi.12550

- Smith JR, Jones FJS, Fureman BE, et al. Accuracy of ICD-10-CM claims-based definitions for epilepsy and seizure type. Epilepsy Res. 2020;166:106414. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106414

- Jetté N, Reid AY, Quan H, et al. How accurate is ICD coding for epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2010;51:62-69. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02201.x

- Kelly P, Chinta R, Privitera G. Do centers of excellence reduce health care costs? Evidence from the US Veterans Health Administration Centers for Epilepsy. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2015;34:18-29.

- Haneef Z, Rehman R, Husain AM. Association between standardized mortality ratio and utilization of care in US veterans with drug-resistant epilepsy compared with all US veterans and the US general population. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:879-887. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2290

- Culpepper WJ, Marrie RA, Langer-Gould A, et al. Validation of an algorithm for identifying MS cases in administrative health claims datasets. Neurology. 2019;92:e1016-e1028 doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007043

- Kobau R, Luncheon C, Greenlund K. Active epilepsy prevalence among U.S. adults is 1.1% and differs by educational level-National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2021. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;142:109180. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109180

- GBD 2017 US Neurological Disorders Collaborators, Feigin VL, Vos T, et al. Burden of neurological disorders across the US from 1990-2017: a global burden of disease study. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:165-176. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4152

- Moura LMVR, Karakis I, Zack MM, et al. Drivers of US health care spending for persons with seizures and/or epilepsies, 2010-2018. Epilepsia. 2022;63:2144-2154. doi:10.1111/epi.17305

- Institute of Medicine. Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding. The National Academies Press; 2012. Accessed November 11, 2025. www.nap.edu/catalog/13379

- Mbizvo GK, Bennett KH, Schnier C, Simpson CR, Duncan SE, Chin RFM. The accuracy of using administrative healthcare data to identify epilepsy cases: A systematic review of validation studies. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1319-1335. doi:10.1111/epi.16547

- Montouris GD. How will primary care physicians, specialists, and managed care treat epilepsy in the new millennium? Neurology. 2000;55:S42-S44.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration: About VHA. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvements Act of 2008, S 2162, 110th Cong (2008). Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-bill/2162

- Rehman R, Kelly PR, Husain AM, Tran TT. Characteristics of Veterans diagnosed with seizures within Veterans Health Administration. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(7):751-762. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.10.0241

- Holden EW, Grossman E, Nguyen HT, et al. Developing a computer algorithm to identify epilepsy cases in managed care organizations. Dis Manag. 2005;8:1-14. doi:10.1089/dis.2005.8.1

- Rehman R, Everhart A, Frontera AT, et al. Implementation of an established algorithm and modifications for the identification of epilepsy patients in the Veterans Health Administration. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:284-290. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.09.012

- Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:475-482. doi:10.1111/epi.12550

- Smith JR, Jones FJS, Fureman BE, et al. Accuracy of ICD-10-CM claims-based definitions for epilepsy and seizure type. Epilepsy Res. 2020;166:106414. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106414

- Jetté N, Reid AY, Quan H, et al. How accurate is ICD coding for epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2010;51:62-69. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02201.x

- Kelly P, Chinta R, Privitera G. Do centers of excellence reduce health care costs? Evidence from the US Veterans Health Administration Centers for Epilepsy. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2015;34:18-29.

- Haneef Z, Rehman R, Husain AM. Association between standardized mortality ratio and utilization of care in US veterans with drug-resistant epilepsy compared with all US veterans and the US general population. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:879-887. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2290

- Culpepper WJ, Marrie RA, Langer-Gould A, et al. Validation of an algorithm for identifying MS cases in administrative health claims datasets. Neurology. 2019;92:e1016-e1028 doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007043

Development and Validation of an Administrative Algorithm to Identify Veterans With Epilepsy

Development and Validation of an Administrative Algorithm to Identify Veterans With Epilepsy

Impact and Recovery of VHA Epilepsy Care Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic affected diverse workplaces globally, leading to temporary and permanent changes across the health care landscape. Included among the impacted areas of care were epilepsy and electroencephalogram (EEG) clinicians and services. Surveys among epilepsy specialists and neurophysiologists conducted at the onset of the pandemic to evaluate working conditions include analyses from the American Epilepsy Society (AES), the National Association of Epilepsy Centers (NAEC), the International League Against Epilepsy, and an Italian national survey.1-4 These investigations revealed reductions in epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) admissions (23% decline), epilepsy surgery (6% decline), inpatient EEG (22% of respondents reported decline), and patients having difficulty accessing epilepsy professionals (28% of respondents reported decline) or obtaining medications (20% of respondents reported decline).1-3

While such research provided evidence for changes to epilepsy care in 2020, there are limited data on subsequent adaptations during the pandemic. These studies did not incorporate data on the spread of COVID-19 or administrative workload numbers to analyze service delivery beyond self reports. This study aimed to address this gap in the literature by highlighting results from longitudinal national surveys conducted at the Epilepsy Centers of Excellence (ECoE), a specialty care service within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which annually serves > 9 million veterans.5 The ECoE represents epileptologists and neurophysiologists across the United States at the 17 primary facilities that were established at the time of this survey (2 ECoEs have been added since survey completion) in 4 geographical regions and for which other regional facilities refer patients for diagnostic services or specialty care.6

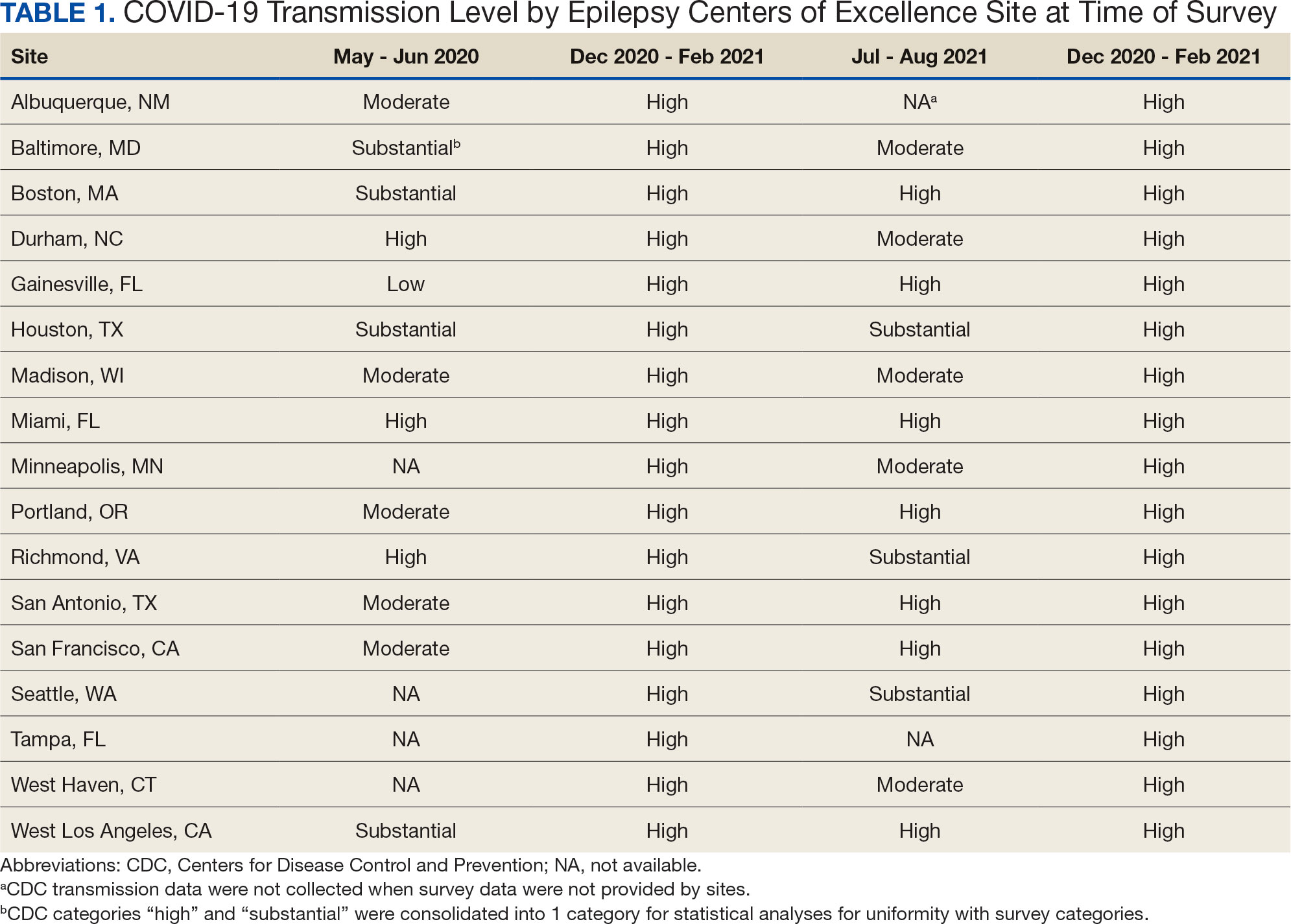

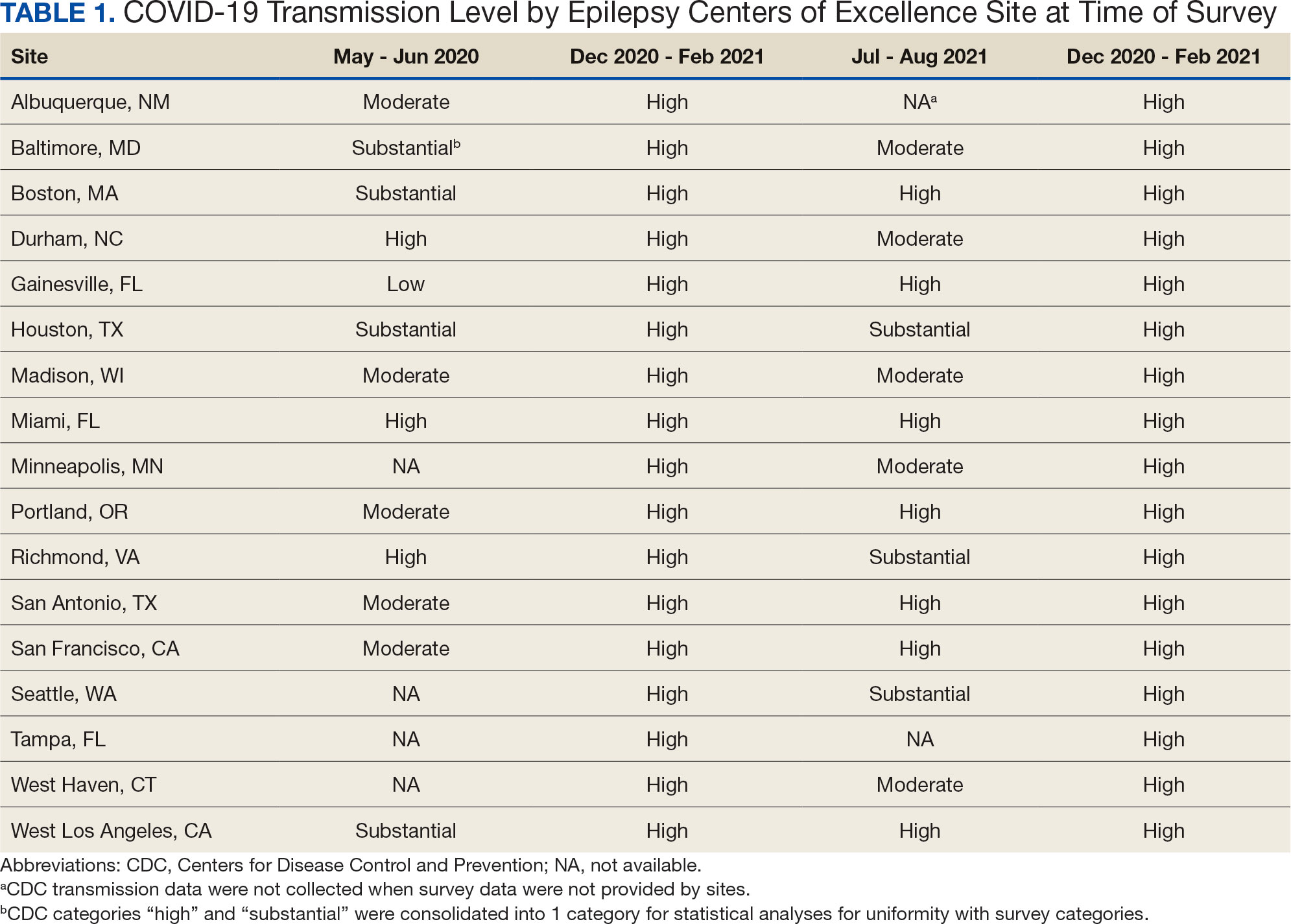

National surveys were conducted among the ECoE directors regarding adaptations made from May 2020 to June 2022 to provide a comprehensive account of limitations they experienced and how adjustments have been made to improve patient care. Survey responses were compared to administrative workload numbers and COVID-19 spread data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to provide a comprehensive analysis of performance during the pandemic.

METHODS

Data were collected as part of a quality improvement initiative by the VHA ECoE; institutional review board approval was not required. An 18-item survey covering 5 broad domains was sent to ECoE directors 4 separate times to accumulate data from 4 time periods: May to June 2020 (T1); December 2020 to February 2021 (T2); July to August 2021 (T3); and June to July 2022 (T4). These periods correspond to the following phases of the pandemic: T1, onset of pandemic; T2, vaccine availability; T3, Delta variant predominant; T4, Omicron variant predominant.

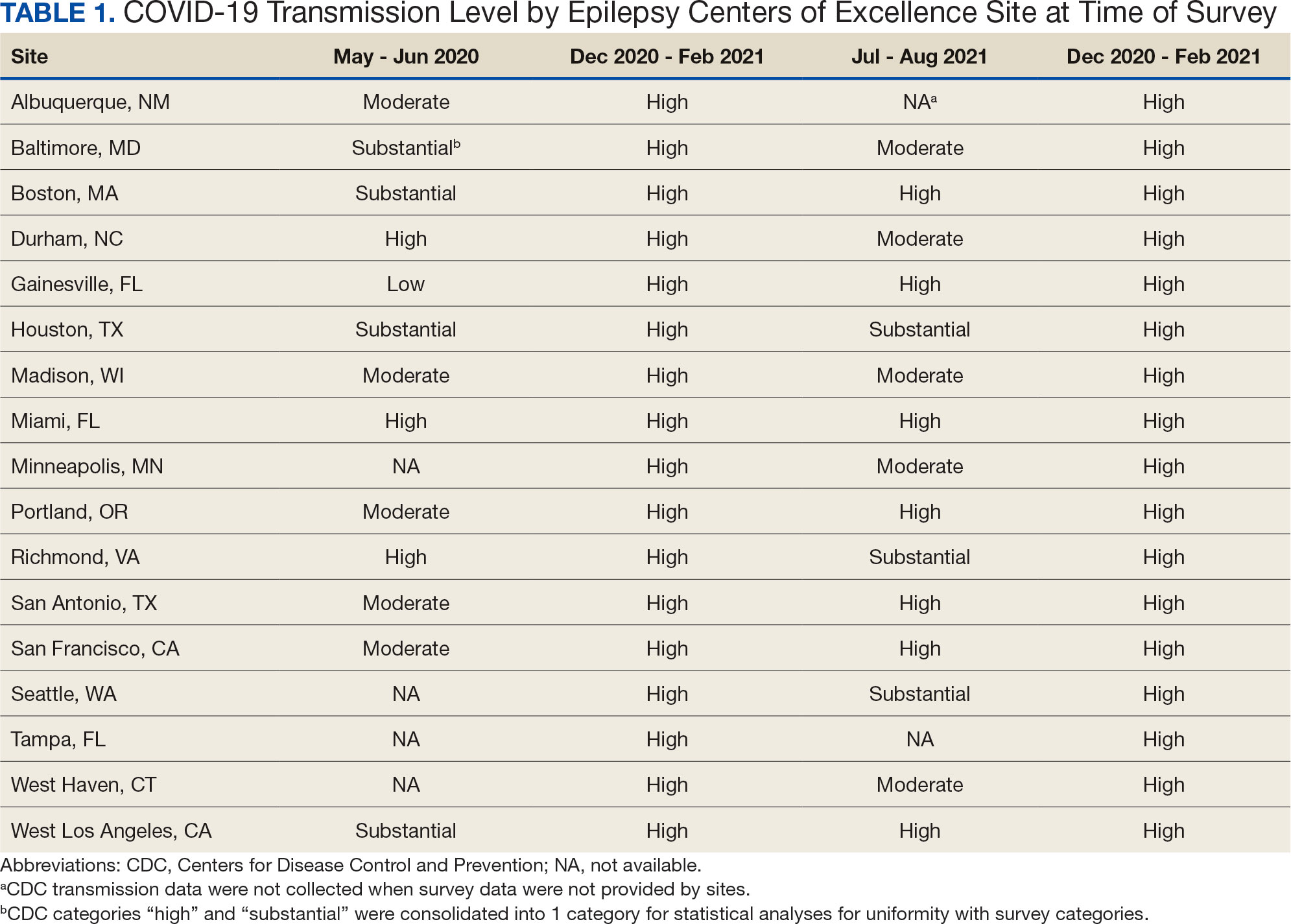

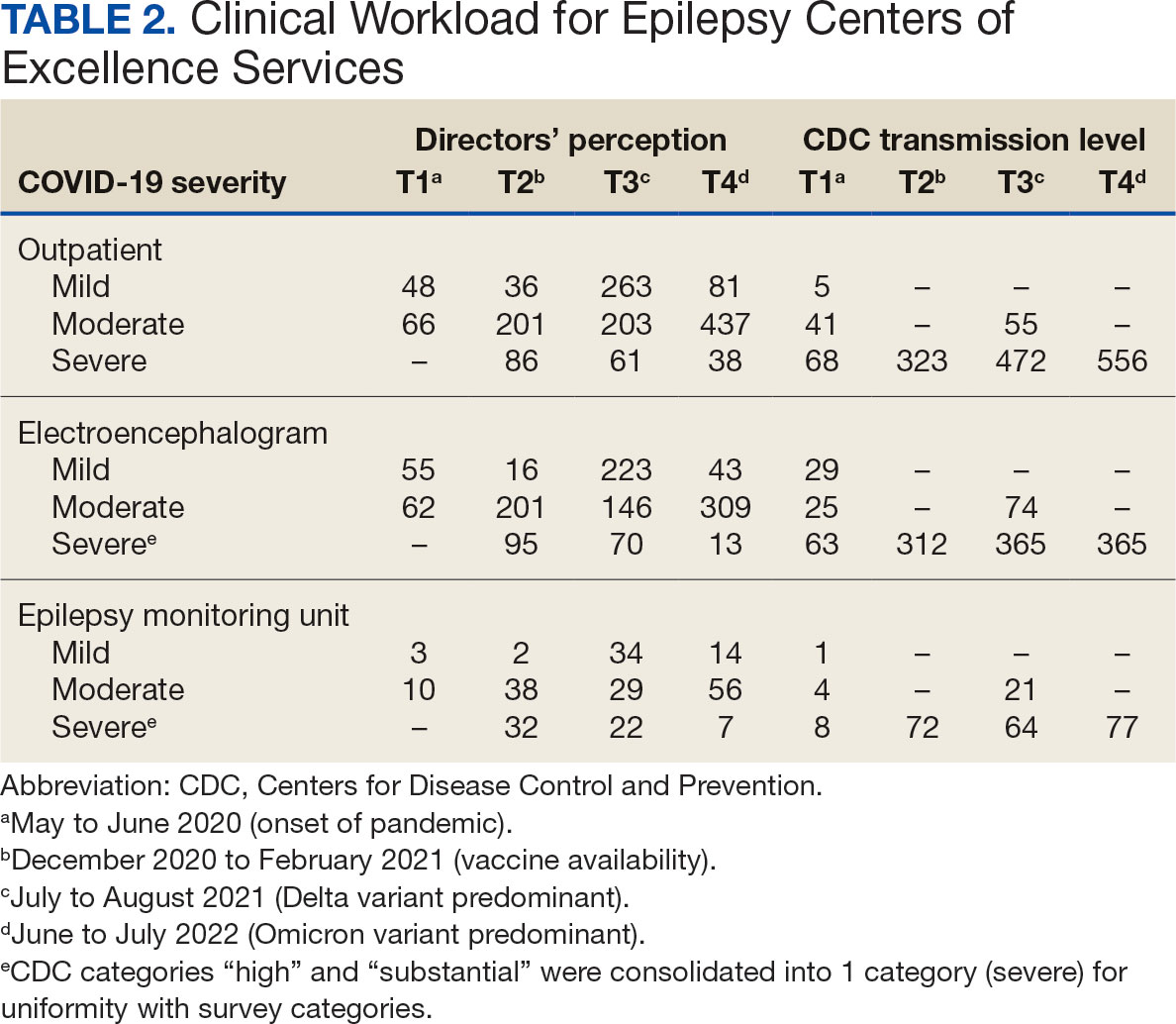

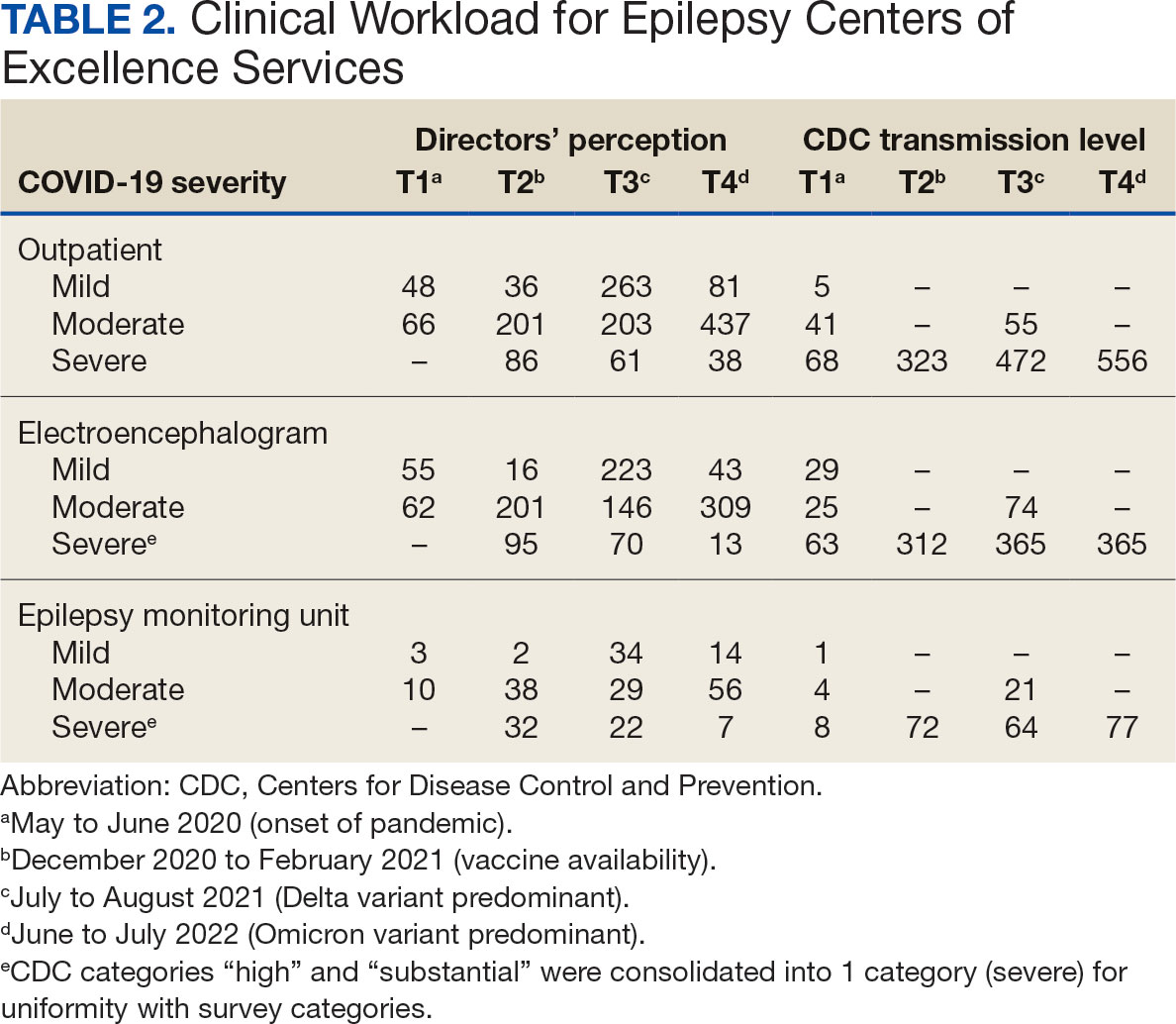

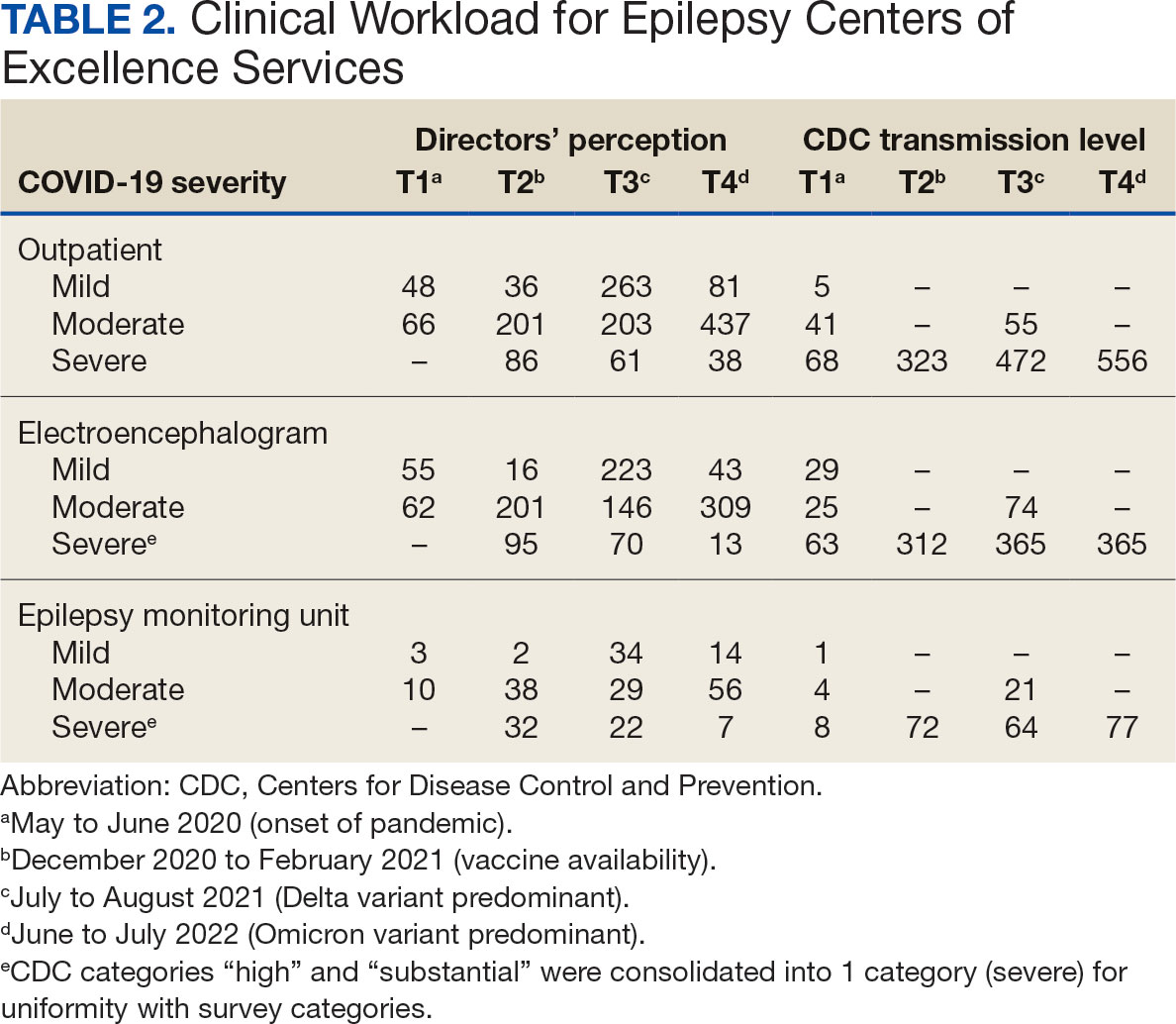

Data on the spread of COVID-19 were collected from the CDC archived dataset, US COVID-19 County Level of Community Transmission Historical Changes (Table 1).7 Administrative workload (patient counts) for EEG, EMU, and outpatient clinics were extracted from VHA administrative databases for the participating sites for the months prior to each survey: T1, April 2020; T2, November 2020; T3, June 2021; and T4, May 2022 (Table 2).

Survey Structure and Content

The survey was developed by the ECoE and was not validated prior to its use due to the time-sensitive nature of gathering information during the pandemic. The first survey (T1) was an emailed spreadsheet with open-ended questions to gauge availability of services (ie, outpatient clinic, EEG, EMU), assess whether safety precautions were being introduced, and understand whether national or local guidelines were thought to be helpful. Responses from this and subsequent surveys were standardized into yes/no and multiple choice formats. Subsequent surveys were administered online using a Research Electronic Data Capture tool.8,9

Availability of outpatient epilepsy services across the 4 time periods were categorized as unlimited (in-person with no restrictions), limited (in-person with restrictions), planned (not currently performed but scheduled for the near future), and unavailable (no in-person services offered) (eAppendices 1-6, available in article PDF).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed to compare survey responses to workload and CDC data on COVID-19 community spread. The following associations were examined: (1) CDC COVID-19 spread vs respondents’ perception of spread; (2) respondents’ perception of spread vs availability of services; (3) CDC COVID-19 spread vs availability of services; (4) respondents’ perception of spread vs workload; and (5) CDC COVID-19 spread vs workload. Availability of services was dichotomized for analyses, with limited or fully available services classified as available. As services were mostly open at T3 regardless of the spread of the virus, and the CDC COVID-19 spread classification for all sites was severe or high at T2 and T4, corresponding associations were not tested at these time points. For associations 1 through 3, Fisher exact tests were used; for associations 4 and 5, Mann-Whitney U tests (where the COVID-19 spread fell into 2 categories) and Kruskal-Wallis tests (for 3 categories of COVID-19 spread) were performed. All tests were 2-tailed and performed at 0.05 error rate. Bonferroni corrections were applied to adjust P values for multiple hypotheses tests.

RESULTS

From the 17 sites invited, responses at each time point were obtained from 13 (T1),17 (T2), 15 (T3), and 16 (T4) centers. There was no significant association between self-reported COVID-19 spread and CDC classification of COVID spread. There were no associations between COVID-19 community spread (respondent reported or CDC severity level) and outpatient clinic availability (self-reported or workload captured). At T3, a positive association was found between the CDC spread level and workload (P = .008), but this was not significant after Bonferroni correction (P = .06).

EEG availability surpassed EMU availability at all time points, although EMU services made some recovery at T3 and T4. No associations were found between COVID-19 community spread (self-reported or CDC severity level) and outpatient EEG or EMU availability (self-reported or workload captured). At T3, there was a positive association between EEG workload and CDC COVID-19 severity level (P = .04), but this was not significant after Bonferroni correction (P = .30).

For outpatient EEG, staff and patient mask use were universally implemented by T2, while the use of full personal protective equipment (PPE) occurred at a subset of sites (T2, 6/17 [35%]; T3, 3/15 [20%]; T4: 4/16 [25%]). COVID-19 testing was rarely implemented prior to outpatient EEG (T1, 0 sites; T2, 1 site; T3, 1 site; T4, 0 sites). Within the EMU, safety precautions including COVID-19 testing, patient mask usage, staff mask usage, and aerosolization demonstrated a sustained majority usage across the 4 surveys.

National and Local Guidelines

The open-ended survey at T1 asked site directors, “Should there be national recommendations on how EEGs and related procedures should be done during the pandemic or should this be left to local conditions?” Responses were mixed, with 5 respondents desiring a national standard, 4 respondents favoring a local response, and 4 respondents believing a national standard should be in place but with modifications based on local outbreak levels and needs.

Surveys performed at T2 through T4 asked, “Which of the following do you feel was/will be helpful in adapting to COVID-19–related changes?” Overall, there was substantial agreement that guidelines were helpful. Most sites anticipated permanent changes in enhanced safety precautions and telehealth.

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal study across 4 time points describes how epilepsy services within the VHA and ECoE adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. The first survey, conducted 2 months after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, allowed a comparison with other concurrent US national surveys.1,2,10 The subsequent surveys describe longitudinal adaptations to balance patient and staff safety with service availability and is a unique feature of the current report. Results demonstrate flexibility and adaptability by the ECoEs surveyed, which surprisingly did not show significant associations between CDC COVID-19 spread data and administrative workload data.

Trends in Availability of Services

The most significant impact of COVID-19 restrictions was during T1. There were no significant relationships between service availability/workload and objective CDC COVID-19 spread levels or subjective self-reported COVID-19 spread. Respondents’ perceptions of local COVID-19 spread showed no association with CDC COVID-19 spread data. It appears that subjective perception of spread may be unreliable and factors other than actual or perceived COVID-19 spread were likely driving patterns for service availability.

In-person outpatient visits were most impacted at T1, similar to other civilian surveys, with only 1 site reporting in-person outpatient visits without limitations.1,2 These numbers significantly changed by T2, with all sites offering either limited or unlimited in-person visits. While the surveys did not evaluate factors leading to this rapid recovery, it may be related to the availability of COVID-19 vaccinations within the VHA during this time.11 The US Department of Veterans Affairs was the first federal agency to mandate employee vaccination.12 By the most recent time point (T4), all responding sites offered outpatient visits. Outpatient EEGs followed a similar trend, with T1 being the most restrictive and full, unrestricted outpatient EEGs available by T3.

Fiscal year (FY) trends from ECoE annual reports suggest that encounters slowly recovered over the course of the pandemic. In FY 2019 there were 13,143 outpatient encounters and 6394 EEGs, which dropped to 8097 outpatient encounters and 4432 EEGs in FY 2020 before rising to 8489 outpatient encounters and 5604 EEGs in FY 2021 and 9772 outpatient encounters and 5062 EEGs in FY 2022. Thus, while clinicians described availability of services, patients may have remained hesitant or were otherwise unable to fulfill in-person appointments. The increased availability of home EEG (145 encounter days in 2021 and 436 encounter days in 2022) may be filling this gap.

In contrast to outpatient clinics and EEG, EMU availability showed relatively slower reimplementation. In the last survey, about 30% of sites were still not offering EMU or had limited services. Early trends regarding reduced staffing and patient reluctance for elective admission cited in other surveys may have also affected EMU availability within the VHA.2,13 Consistent with trends in availability, ECoE annual report data suggest EMU patient participation was about one-half of prepandemic rates: 3069 encounters in FY 2019 dropped to 1614 encounters in 2020. By 2021, rates were about two-thirds of prepandemic rates with 2058 encounters in 2021 and 2101 encounters in 2022.

Early survey results (T1) from this study echo trends from other surveys. In the AES survey (April to June 2020), about a quarter of respondents (22%) reported doing fewer EEG studies than usual. The Italian national survey (April 2020) revealed reduced presurgical evaluations (81%), ambulatory EEG (78%), standard EEG (5%) and long-term EEG (32%).4 In the NAEC survey (end of 2020)—which roughly corresponded to T2—outpatient EEGs were still < 75% of pre-COVID levels in one-half of the centers.

National and Local Guidelines

Both national and local guidelines were perceived as useful by most respondents, with national guidelines being more beneficial. This aligns with the NAEC survey, where there was a perceived need for detailed recommendations for PPE and COVID-19 testing of patients, visitors, and staff. Based on national and local guidelines, ECoE implemented safety procedures, as reflected in responses. Staff masking procedures appeared to be the most widely adopted for all services, while the use of full PPE waned as the pandemic progressed. COVID-19 testing was rarely used for routine outpatient visits but common in EMU admissions. This is similar to a survey conducted by the American Academy of Neurology which found full PPE implementation intermittently in outpatient settings and more frequently in inpatient settings.14

Telehealth Attitudes

While most sites anticipated permanent implementation of safety precautions and telehealth, the latter was consistently reported as more likely to be sustained. The VHA had a large and well-developed system of telehealth services that considerably predated the pandemic.15,16 Through this established infrastructure, remote services were quickly increased across the VHA.17-19 This telehealth structure was supplemented by the ability of VHA clinicians to practice across state lines, following a 2018 federal rule.20 The AES survey noted the VHA ECoE's longstanding experience with telehealth as a model for telemedicine use in providing direct patient care, remote EEG analysis, and clinician-to-clinician consultation.1

Trends in the number of telehealth patients seen, observed through patterns in ECoE annual reports are consistent with positive views toward this method of service provision. Specifically, these annual reports capture trends in Video Telehealth Clinic (local station), Video Telehealth Clinic (different station), Home Video Telehealth, Telephone Clinic, and eConsults. Though video telehealth at in-person stations had a precipitous drop in 2020 that continued to wane in subsequent years (898 encounters in 2019; 455 encounters in 2020; 90 encounters in 2021; 88 encounters in 2022), use of home video telehealth rose over time (143 encounters in 2019; 1003 encounters in 2020; 3206 encounters in 2021; 3315 encounters in 2022). Use of telephone services rose drastically in 2020 but has since become a less frequently used service method (2636 in 2019; 5923 in 2020; 5319 in 2021; 3704 in 2022).

Limitations

While the survey encouraged a high response rate, this limited its scope and interpretability. While the availability of services was evaluated, the underlying reasons were not queried. Follow-up questions about barriers to reopening may have allowed for a better understanding of why some services, such as EMU, continued to operate suboptimally later in the pandemic. Similarly, asking about unique strategies or barriers for telehealth would have allowed for a better understanding of its current and future use. We hypothesize that staffing changes during the pandemic may have influenced the availability of services, but changes to staffing were not assessed via the survey and were not readily available via other sources (eg, ECoE annual reports) at the time of publication. An additional limitation is the lack of comparable surveys in the literature for time points T2 to T4, as most analogous surveys were performed early in 2020.

Conclusions

This longitudinal study performed at 4 time points during the COVID-19 pandemic is the first to offer a comprehensive picture of changes to epilepsy and EEG services over time, given that other similar surveys lacked follow-up. Results reveal a significant limitation of services at VHA ECoE shortly after the onset of the pandemic, with return to near-complete operational status 2 years later. While safety precautions and telehealth are predicted to continue, telehealth is perceived as a more permanent change in services.

Albert DVF, Das RR, Acharya JN, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on epilepsy care: a survey of the American Epilepsy Society membership. Epilepsy Curr. 2020;20(5):316-324. doi:10.1177/1535759720956994

Ahrens SM, Ostendorf AP, Lado FA, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on epilepsy center practice in the United States. Neurology. 2022;98(19):e1893-e1901. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200285

Cross JH, Kwon CS, Asadi-Pooya AA, et al. Epilepsy care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsia. 2021;62(10):2322-2332. doi:10.1111/epi.17045

Assenza G, Lanzone J, Ricci L, et al. Electroencephalography at the time of Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(8):1999-2004. doi:10.1007/s10072-020-04546-8

US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. Updated September 7, 2022. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Epilepsy Centers of Excellence (ECoE). Annual report fiscal year 2019. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.epilepsy.va.gov/docs/FY19AnnualReport-VHAEpilepsyCentersofExcellence.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States COVID-19 county level of community transmission historical changes – ARCHIVED. Updated February 20, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://data.cdc.gov/Public-Health-Surveillance/United-States-COVID-19-County-Level-of-Community-T/nra9-vzzn

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

World Health Organization. Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Updated July 31, 2020. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA announces initial plans for COVID-19 vaccine distribution. News release. December 10, 2020. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5580

Steinhauer J. V.A. Issues Vaccine Mandate for Health Care Workers, a First for a Federal Agency. The New York Times. August 16, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/26/us/politics/veterans-affairs-coronavirus-covid-19.html

Zafar SF, Khozein RJ, LaRoche SM, Westover MB, Gilmore EJ. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on continuous EEG utilization. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2022;39(7):567-574. doi:10.1097/WNP.0000000000000802

Qureshi AI, Rheaume C, Huang W, et al. COVID-19 exposure during neurology practice. Neurologist. 2021;26(6):225-230. doi:10.1097/NRL.0000000000000346

Darkins A, Cruise C, Armstrong M, Peters J, Finn M. Enhancing access of combat-wounded veterans to specialist rehabilitation services: the VA Polytrauma Telehealth Network. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):182-187. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.027