User login

SAN DIEGO – Out of a cohort of nearly 2,900 rheumatic patients, none developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine, in a single-center retrospective study.

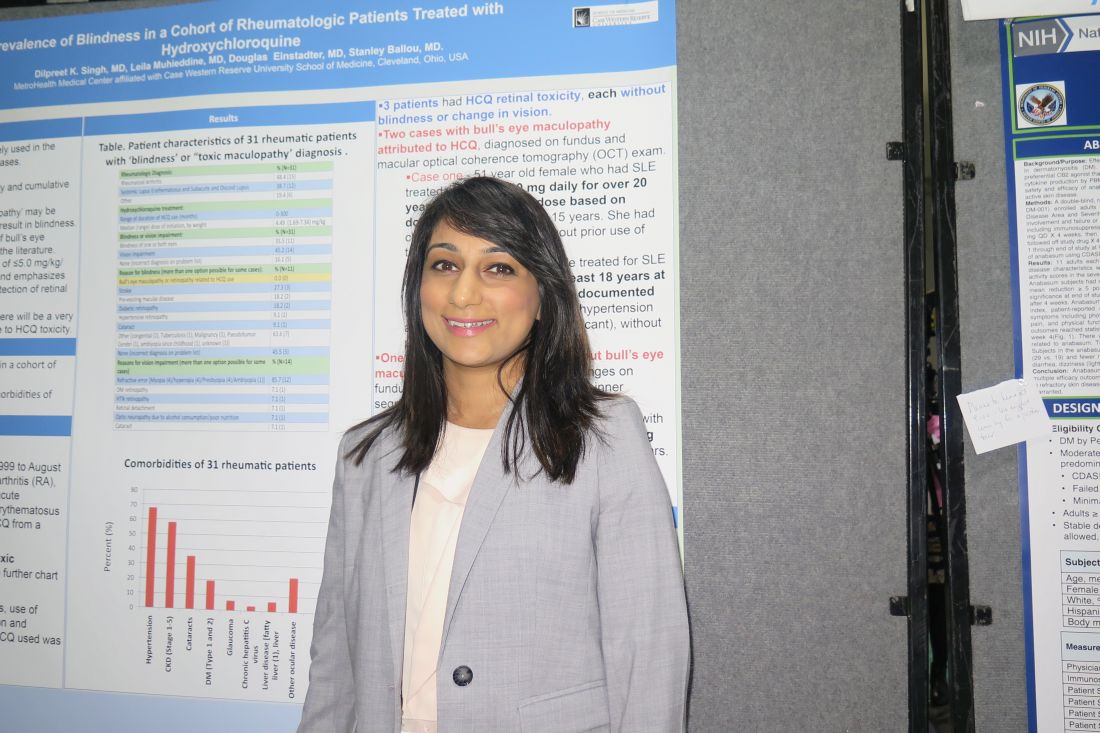

“That’s very reassuring,” lead study author Dilpreet K. Singh, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “It’s still important to be vigilant with our screening and also to take note of the hydroxychloroquine dose that they’re on, because a lot of our patients have been on hydroxychloroquine for 10 or 15 years and there may not have been a dose adjustment. It’s also important to focus on the patients’ comorbidities and get them under better control.”

In an effort to assess the prevalence of blindness in a cohort of rheumatic patients and to identify the characteristics and comorbidities of those with HCQ retinal toxicity, Dr. Singh and her associates retrospectively evaluated 2,898 patients at MetroHealth Medical Center between January 1999 and August of 2017 with diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and discoid lupus erythematosus who had a prescription written for HCQ.

In all, 31 had a diagnosis of “blindness” or “toxic maculopathy,” and these cases were further assessed for patient demographics, comorbidities, use of tamoxifen, weight and dose at initiation and discontinuation of HCQ, and duration of HCQ. Nearly 70% of these patients had hypertension, about 60% had chronic kidney disease, and 35% had cataracts. The researchers confirmed that in each of the cases the blindness was not caused by HCQ ocular toxicity, but instead by stroke, preexisting macular disease, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, or cataracts.

Only 3 of the 31 patients were found to have HCQ retinal toxicity, each without blindness or change in vision. Two patients had bull’s-eye maculopathy and one had HCQ toxic maculopathy. Each of the three patients had received HCQ for more than 18 years at doses that ranged from 6.3 to 8.2 mg/kg based on documented weight, and none had functional vision loss at diagnosis.

“It’s reassuring to know that there’s a very small percentage of patients that will have HCQ-related toxicity,” Dr. Singh concluded. “We should also be focusing on the comorbidities [such as] diabetes, hypertension, and stroke-related vision loss that are common in our population of rheumatic patients, because these are contributing to visual impairment and blindness.”

She reported having no disclosures.

dbrunk@frontlinemedcom.com

SAN DIEGO – Out of a cohort of nearly 2,900 rheumatic patients, none developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine, in a single-center retrospective study.

“That’s very reassuring,” lead study author Dilpreet K. Singh, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “It’s still important to be vigilant with our screening and also to take note of the hydroxychloroquine dose that they’re on, because a lot of our patients have been on hydroxychloroquine for 10 or 15 years and there may not have been a dose adjustment. It’s also important to focus on the patients’ comorbidities and get them under better control.”

In an effort to assess the prevalence of blindness in a cohort of rheumatic patients and to identify the characteristics and comorbidities of those with HCQ retinal toxicity, Dr. Singh and her associates retrospectively evaluated 2,898 patients at MetroHealth Medical Center between January 1999 and August of 2017 with diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and discoid lupus erythematosus who had a prescription written for HCQ.

In all, 31 had a diagnosis of “blindness” or “toxic maculopathy,” and these cases were further assessed for patient demographics, comorbidities, use of tamoxifen, weight and dose at initiation and discontinuation of HCQ, and duration of HCQ. Nearly 70% of these patients had hypertension, about 60% had chronic kidney disease, and 35% had cataracts. The researchers confirmed that in each of the cases the blindness was not caused by HCQ ocular toxicity, but instead by stroke, preexisting macular disease, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, or cataracts.

Only 3 of the 31 patients were found to have HCQ retinal toxicity, each without blindness or change in vision. Two patients had bull’s-eye maculopathy and one had HCQ toxic maculopathy. Each of the three patients had received HCQ for more than 18 years at doses that ranged from 6.3 to 8.2 mg/kg based on documented weight, and none had functional vision loss at diagnosis.

“It’s reassuring to know that there’s a very small percentage of patients that will have HCQ-related toxicity,” Dr. Singh concluded. “We should also be focusing on the comorbidities [such as] diabetes, hypertension, and stroke-related vision loss that are common in our population of rheumatic patients, because these are contributing to visual impairment and blindness.”

She reported having no disclosures.

dbrunk@frontlinemedcom.com

SAN DIEGO – Out of a cohort of nearly 2,900 rheumatic patients, none developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine, in a single-center retrospective study.

“That’s very reassuring,” lead study author Dilpreet K. Singh, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “It’s still important to be vigilant with our screening and also to take note of the hydroxychloroquine dose that they’re on, because a lot of our patients have been on hydroxychloroquine for 10 or 15 years and there may not have been a dose adjustment. It’s also important to focus on the patients’ comorbidities and get them under better control.”

In an effort to assess the prevalence of blindness in a cohort of rheumatic patients and to identify the characteristics and comorbidities of those with HCQ retinal toxicity, Dr. Singh and her associates retrospectively evaluated 2,898 patients at MetroHealth Medical Center between January 1999 and August of 2017 with diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and discoid lupus erythematosus who had a prescription written for HCQ.

In all, 31 had a diagnosis of “blindness” or “toxic maculopathy,” and these cases were further assessed for patient demographics, comorbidities, use of tamoxifen, weight and dose at initiation and discontinuation of HCQ, and duration of HCQ. Nearly 70% of these patients had hypertension, about 60% had chronic kidney disease, and 35% had cataracts. The researchers confirmed that in each of the cases the blindness was not caused by HCQ ocular toxicity, but instead by stroke, preexisting macular disease, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, or cataracts.

Only 3 of the 31 patients were found to have HCQ retinal toxicity, each without blindness or change in vision. Two patients had bull’s-eye maculopathy and one had HCQ toxic maculopathy. Each of the three patients had received HCQ for more than 18 years at doses that ranged from 6.3 to 8.2 mg/kg based on documented weight, and none had functional vision loss at diagnosis.

“It’s reassuring to know that there’s a very small percentage of patients that will have HCQ-related toxicity,” Dr. Singh concluded. “We should also be focusing on the comorbidities [such as] diabetes, hypertension, and stroke-related vision loss that are common in our population of rheumatic patients, because these are contributing to visual impairment and blindness.”

She reported having no disclosures.

dbrunk@frontlinemedcom.com

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point: The incidence of blindness due to hydroxychloroquine toxicity is very low.

Major finding: No patients developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine.

Study details: A single-center retrospective study of 2,898 rheumatic patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Singh reported having no disclosures.