User login

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE Life on the line

A 32-year-old woman in the 24th week of her fourth pregnancy arrives at the emergency department complaining of cough and congestion, shortness of breath, and swelling in her face, hands, and feet. The swelling has become worse over the past 2 weeks, and she had several episodes of bloody vomiting the day before her visit. The patient says she has not experienced any leakage of fluid, vaginal bleeding, or contractions. She reports good fetal movement.

The patient’s medical history is unremarkable, but a review of systems reveals a 15-lb weight loss over the past 2 weeks, racing heart, worsening edema and shortness of breath, and diarrhea.

Physical findings include exophthalmia and an enlarged thyroid with a nodule on the right side, as well as bilateral rales, tachycardia, tremor, and increased deep tendon reflexes. There is no evidence of fetal cardiac failure or goiter.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the mother shows bilateral pleural effusions indicative of high-output cardiac failure. Thyroid ultrasonography (US) reveals a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with a right-sided mass.

The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level is undetectable. Fetal heart rate is in the 160s, with normal variability and occasional variable deceleration. Fetal US is consistent with the estimated gestational age and shows adequate amniotic fluid and no gross fetal anomalies.

What is the likely diagnosis?

This is a classic example of undiagnosed hyperthyroidism in pregnancy manifesting as thyroid storm.

As the case illustrates, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism in pregnancy poses a significant challenge for the obstetrician. The condition can cause miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, and—at its most dangerous—thyroid storm.1 Thyroid storm is a life-threatening emergency, and treatment must be initiated even before hyperthyroidism is confirmed by thyroid function testing.2 The good news is that these complications can be successfully avoided with adequate control of thyroid function.

Overt hyperthyroidism, seen in 0.2% of pregnancies, requires active intervention to avert adverse pregnancy outcome and neurologic damage to the fetus. Subclinical disease, seen in 1.7% of pregnancies, can also create serious obstetrical problems.1

The effects of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy vary in severity, ranging from the fairly innocuous, transient, and self-limited state called gestational transient thyrotoxicosis to the life-threatening emergency of thyroid storm. This review will update you on how to manage this disorder for optimal pregnancy outcome.

To screen or not to screen

Routine screening for thyroid dysfunction has been recommended for women who have infertility, menstrual disorders, or type 1 diabetes mellitus, and for pregnant women who have signs and symptoms of the disorder. Some authors recommend screening all pregnant women, but routine screening is not endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.2,3

Thyroid testing in pregnancy is recommended in women who:

- have a family history of autoimmune thyroid disease

- are on thyroid therapy

- have a goiter or

- have insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Pregnant women who have a history of high-dose neck radiation, thyroid therapy, postpartum thyroiditis, or an infant born with thyroid disease should also be tested at the first prenatal visit.4

Telltale signs and laboratory tests

The signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism can include nervousness, heat intolerance, tachycardia, palpitations, goiter, weight loss, thyromegaly, exophthalmia, increased appetite, nausea and vomiting, sweating, and tremor.1 The difficulty here? Many of these symptoms are also seen in pregnant women who have normal thyroid function, so that symptoms alone are not a reliable guide.

Instead, the diagnosis of overt hyperthyroidism is made on the basis of laboratory tests indicating suppressed TSH and elevated levels of free thyroxine (FT4) and free triiodothyronine (FT3). Subclinical hyperthyroidism is defined as a suppressed TSH level with normal FT4 and FT3 levels.2

The effects of hyperthyroidism on laboratory values are shown in TABLE 1. A form of hyperthyroidism called the T3– toxicosis syndrome is diagnosed by suppressed TSH, normal FT4, and elevated FT3 levels.4

TABLE 1

Is your pregnant patient hyperthyroid? Five-test lab panel offers a guide

| TEST AND RESULT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THYROID-STIMULATING HORMONE | FREE TRI-IODOTHYRONINE | FREE THYROXINE | TOTAL TRI-IODOTHYRONINE | TOTAL THYROXINE | THEN THE MOTHER’S CONDITION IS … |

| No change | No change | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Pregnancy |

| ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Hyperthyroidism |

| ↓ | No change | No change | No change | No change | Subclinical hyperthyroidism |

What are the causes?

The most common cause of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy—accounting for some 95% of cases—is Graves’ disease.2 This autoimmune disorder is characterized by autoantibodies that activate the TSH receptor. These autoantibodies cross the placenta and can cause fetal and neonatal thyroid dysfunction even when the mother herself is in a euthyroid condition.4

Far less often, hyperthyroidism in pregnancy has a cause other than Graves’ disease; TABLE 2 summarizes the possibilities.1 Other causes of hyperthyroidism in early pregnancy include choriocarcinoma and gestational trophoblastic disease (partial and complete moles) (TABLE 3).

TABLE 2

Causes of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

| Graves’ disease |

| Adenoma |

| Toxic nodular goiter |

| Thyroiditis |

| Excessive thyroid hormone intake |

| Choriocarcinoma |

| Molar pregnancy |

TABLE 3

What causes severe hyperthyroidism before 20 weeks’ gestation?

| Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis |

| Choriocarcinoma |

Gestational trophoblastic disease

|

Signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease

Women who have Graves’ disease usually have thyroid nodules and may have exophthalmia, pretibial myxedema, and tachycardia. They also display other classic signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as muscle weakness, tremor, and warm and moist skin.

During pregnancy, Graves’ disease usually becomes worse during the first trimester and postpartum period; symptoms resolve during the second and third trimesters.1

Thyrotoxin receptor and antithyroid antibodies

Antithyroid antibodies are common in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, as a response to thyroid antigens. The two most common antithyroid antibodies are thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO). Anti-TPO antibodies are associated with postpartum thyroiditis and fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism. TSH-receptor antibodies include thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) and TSH-receptor antibody. TSI is associated with Graves’ disease. TSH-receptor antibody is associated with fetal goiter, congenital hypothyroidism, and chronic thyroiditis without goiter.4

Who do you test for antibodies? Test for maternal thyroid antibodies in patients who:

- had Graves’ disease with fetal or neonatal hyperthyroidism in a previous pregnancy

- have active Graves’ disease being treated with antithyroid drugs

- are euthyroid or have undergone ablative therapy and have fetal tachycardia or intrauterine growth restriction

- have chronic thyroiditis without goiter

- have fetal goiter on ultrasound.

Newborns who have congenital hypothyroidism should also be screened for thyroid antibodies.4

What are the consequences?

Hyperthyroidism can have multiple effects on the pregnant patient and her fetus, ranging in severity from the minimal to the catastrophic.

Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis

This condition is presumably related to high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, a substance known to stimulate TSH receptors. Unhappily for your patient, the condition is usually heralded by severe bouts of nausea and vomiting starting at 4 to 8 weeks’ gestation. Laboratory tests show significantly elevated levels of FT4 and FT3 and suppressed TSH. Despite this significant derangement, patients generally have no evidence of a hypermetabolic state.

This condition resolves by 14 to 20 weeks of gestation, is not associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, and does not require treatment with antithyroid medication.1

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

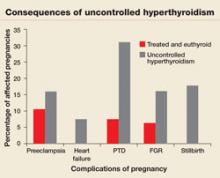

Pregnant women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism are at increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage, congestive heart failure, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia.1 Studies that evaluated pregnancy outcomes in 239 women with overt hyperthyroidism showed increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, compared with treated, euthyroid women (FIGURE 1).5-7

FIGURE 1 Consequences of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism

Several studies have found a much higher risk of pregnancy complications in women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, compared with their treated and euthyroid peers.5-7

PTD=preterm delivery; FGR=fetal growth restrictions.

Fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism in the fetus or newborn is caused by placental transfer of maternal immunoglobulin antibodies (TSI) to the fetus and is associated with maternal Graves’ disease. The incidence of neonatal hyperthyroidism is less than 1%. It can be predicted by rising levels of maternal TSI antibodies, to the point where levels in the third trimester are three to five times higher than they were at the beginning of pregnancy.4

Fetal hyperthyroidism develops at about 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation in mothers with a history of Graves’ disease who have been treated surgically or with ablative therapy prior to pregnancy. Even when these therapies achieve a euthyroid state in the mother, TSI levels may remain elevated and lead to fetal hyperthyroidism.

Characteristics of hyperthyroidism in the fetus include tachycardia, intrauterine growth restriction, congestive heart failure, oligohydramnios, and goiter. Treating the mother with antithyroid medications will ameliorate symptoms in the fetus.4

Thyroid storm

This is the worst-case scenario—a rare but potentially lethal complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism. Thyroid storm is a hypermetabolic state characterized by fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, altered mental status, restlessness, nervousness, seizures, coma, and cardiac arrhythmias. It occurs in 1% to 2% of patients receiving thioamide therapy.8

In most instances, thyroid storm is a complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, but it can also be precipitated by infection, surgery, thromboembolism, preeclampsia, labor, and delivery.

Thyroid storm is a medical emergency

This manifestation of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism is so urgent that treatment should be initiated before the results of TSH, FT4, and FT3 tests are available.2,8 Delivery should be avoided, if possible, until the mother’s condition can be stabilized but, if the status of the fetus is compromised, delivery is indicated.

Treatment of thyroid storm begins with stabilization of the patient, followed by initiation of a stepwise management approach (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2 Management of thyroid storm

Aggressive management of thyroid storm is indicated, following a stepwise approach. Each medication used to treat thyroid storm plays a specific role in suppressing thyroid function. Propylthiouracil (PTU) blocks additional synthesis of thyroid hormone and inhibits the conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3). Methimazole blocks additional synthesis of thyroid hormones. Saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI), Lugol’s solution, and sodium iodide block the release of thyroid hormone from the gland. Dexamethasone is used to decrease thyroid hormone release and peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. Propranolol is used to treat maternal tachycardia by inhibiting the adrenergic effects of excessive thyroid hormones. Finally, phenobarbital is used to treat maternal agitation and restlessness caused by the increased catabolism of thyroid hormones.

SOURCE: Adapted from ACOG.2

Treatment of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

Two medications are available to treat hyperthyroidism in pregnancy: propylthiouracil (PTU) and methimazole. These medications are known as thioamides.1,2

PTU blocks the oxidation of iodine in the thyroid gland, thereby preventing the synthesis of T4 and T3. The initial dosage for hyperthyroid women who are not pregnant is usually 300 to 450 mg/day in three divided doses every 8 hours, and this dosing strategy can also be applied to the pregnant patient. Maintenance therapy is usually achieved with 100 to 150 mg/day in divided doses every 8 to 12 hours.9

Methimazole works by blocking the organification of iodide, which decreases thyroid hormone production. The usual dosing, given in three divided doses every 8 hours, is 15 mg/day for mild hyperthyroidism, 30 to 40 mg/day for moderately severe hyperthyroidism, and 60 mg/day for severe hyperthyroidism. Maintenance therapy with methimazole is usually given at a dosage of 5 to 15 mg/day.9

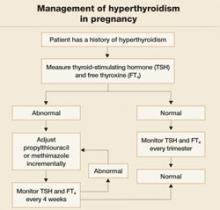

In the past, PTU was considered the drug of choice for treatment of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy because clinicians believed it crossed the placenta to a lesser degree than did methimazole, and because methimazole was associated with fetal esophageal and choanal atresia and fetal cutis aplasia (congenital skin defect of the scalp).1,2 Available evidence does not, however, support these conclusions.8,10 Whatever medication regimen you choose, thyroid function should be monitored 1) every 4 weeks until TSH and FT4 levels are within normal limits and 2) every trimester thereafter. FIGURE 3 presents an algorithm for managing hyperthyroidism in pregnancy.

FIGURE 3 Management of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

CASE Resolved

The patient in thyroid storm described at the beginning of this article requires aggressive management, as outlined in the algorithm in FIGURE 2. As her symptoms diminish, fetal tachycardia resolves. The patient’s FT4 level begins to decline, consistent with appropriate treatment, and she is discharged home and instructed to continue PTU and labetalol and to follow up at the endocrinology and high-risk obstetrics clinics as soon as possible.

The patient does not follow this advice. Consequently, she presents at 33 5/7 weeks in a hypertensive crisis, with symptoms similar to those she first exhibited plus acute pulmonary edema. Fetal heart rate is initially in the 130s, with good variability and occasional decelerations (FIGURE 4A), but decelerations then become worse (FIGURE 4B) and emergency cesarean section is performed.

A male infant is delivered, weighing 2,390 g. Apgar scores are 0 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. A 25% placental abruption is noted at the time of delivery.

Mother and fetus are stabilized and discharged.

FIGURE 4 Weakening fetal status in a mother who is in thyroid storm

Fetal heart rate is initially in the 130s with good variability and occasional decelerations (A), but then deteriorates, with increasing decelerations (B), an indication for immediate delivery.

1. Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1283-1292.

2. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 37, August 2002. (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 32, November 2001). Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:387-396.

3. Mitchell ML, Klein RZ. The sequelae of untreated maternal hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151 Suppl 3:U45-48.

4. Mestman JH. Endocrine diseases in pregnancy. In: Gabbe S, Niebyl JR, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:1117-1168.

5. Davis LE, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. Hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:108-112.

6. Davis LE, Lucas MJ, Hankins GD, Roark ML, Cunningham FG. Thyrotoxicosis complicating pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:63-70.

7. Kriplani A, Buckshee K, Bhargava VL, Takkar D, Ammini AC. Maternal and perinatal outcome in thyrotoxicosis complicating pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;54:159-163.

8. Belford MA. Navigating a thyroid storm. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2006; October:38–46.

9. Lazarus JH, Othman S. Thyroid disease in relation to pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1991;34:91-98.

10. Kent GN, Stuckey BG, Allen JR, Lambert T, Gee V. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction: clinical assessment and relationship to psychiatric affective morbidity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;51:429-438.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE Life on the line

A 32-year-old woman in the 24th week of her fourth pregnancy arrives at the emergency department complaining of cough and congestion, shortness of breath, and swelling in her face, hands, and feet. The swelling has become worse over the past 2 weeks, and she had several episodes of bloody vomiting the day before her visit. The patient says she has not experienced any leakage of fluid, vaginal bleeding, or contractions. She reports good fetal movement.

The patient’s medical history is unremarkable, but a review of systems reveals a 15-lb weight loss over the past 2 weeks, racing heart, worsening edema and shortness of breath, and diarrhea.

Physical findings include exophthalmia and an enlarged thyroid with a nodule on the right side, as well as bilateral rales, tachycardia, tremor, and increased deep tendon reflexes. There is no evidence of fetal cardiac failure or goiter.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the mother shows bilateral pleural effusions indicative of high-output cardiac failure. Thyroid ultrasonography (US) reveals a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with a right-sided mass.

The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level is undetectable. Fetal heart rate is in the 160s, with normal variability and occasional variable deceleration. Fetal US is consistent with the estimated gestational age and shows adequate amniotic fluid and no gross fetal anomalies.

What is the likely diagnosis?

This is a classic example of undiagnosed hyperthyroidism in pregnancy manifesting as thyroid storm.

As the case illustrates, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism in pregnancy poses a significant challenge for the obstetrician. The condition can cause miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, and—at its most dangerous—thyroid storm.1 Thyroid storm is a life-threatening emergency, and treatment must be initiated even before hyperthyroidism is confirmed by thyroid function testing.2 The good news is that these complications can be successfully avoided with adequate control of thyroid function.

Overt hyperthyroidism, seen in 0.2% of pregnancies, requires active intervention to avert adverse pregnancy outcome and neurologic damage to the fetus. Subclinical disease, seen in 1.7% of pregnancies, can also create serious obstetrical problems.1

The effects of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy vary in severity, ranging from the fairly innocuous, transient, and self-limited state called gestational transient thyrotoxicosis to the life-threatening emergency of thyroid storm. This review will update you on how to manage this disorder for optimal pregnancy outcome.

To screen or not to screen

Routine screening for thyroid dysfunction has been recommended for women who have infertility, menstrual disorders, or type 1 diabetes mellitus, and for pregnant women who have signs and symptoms of the disorder. Some authors recommend screening all pregnant women, but routine screening is not endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.2,3

Thyroid testing in pregnancy is recommended in women who:

- have a family history of autoimmune thyroid disease

- are on thyroid therapy

- have a goiter or

- have insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Pregnant women who have a history of high-dose neck radiation, thyroid therapy, postpartum thyroiditis, or an infant born with thyroid disease should also be tested at the first prenatal visit.4

Telltale signs and laboratory tests

The signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism can include nervousness, heat intolerance, tachycardia, palpitations, goiter, weight loss, thyromegaly, exophthalmia, increased appetite, nausea and vomiting, sweating, and tremor.1 The difficulty here? Many of these symptoms are also seen in pregnant women who have normal thyroid function, so that symptoms alone are not a reliable guide.

Instead, the diagnosis of overt hyperthyroidism is made on the basis of laboratory tests indicating suppressed TSH and elevated levels of free thyroxine (FT4) and free triiodothyronine (FT3). Subclinical hyperthyroidism is defined as a suppressed TSH level with normal FT4 and FT3 levels.2

The effects of hyperthyroidism on laboratory values are shown in TABLE 1. A form of hyperthyroidism called the T3– toxicosis syndrome is diagnosed by suppressed TSH, normal FT4, and elevated FT3 levels.4

TABLE 1

Is your pregnant patient hyperthyroid? Five-test lab panel offers a guide

| TEST AND RESULT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THYROID-STIMULATING HORMONE | FREE TRI-IODOTHYRONINE | FREE THYROXINE | TOTAL TRI-IODOTHYRONINE | TOTAL THYROXINE | THEN THE MOTHER’S CONDITION IS … |

| No change | No change | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Pregnancy |

| ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Hyperthyroidism |

| ↓ | No change | No change | No change | No change | Subclinical hyperthyroidism |

What are the causes?

The most common cause of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy—accounting for some 95% of cases—is Graves’ disease.2 This autoimmune disorder is characterized by autoantibodies that activate the TSH receptor. These autoantibodies cross the placenta and can cause fetal and neonatal thyroid dysfunction even when the mother herself is in a euthyroid condition.4

Far less often, hyperthyroidism in pregnancy has a cause other than Graves’ disease; TABLE 2 summarizes the possibilities.1 Other causes of hyperthyroidism in early pregnancy include choriocarcinoma and gestational trophoblastic disease (partial and complete moles) (TABLE 3).

TABLE 2

Causes of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

| Graves’ disease |

| Adenoma |

| Toxic nodular goiter |

| Thyroiditis |

| Excessive thyroid hormone intake |

| Choriocarcinoma |

| Molar pregnancy |

TABLE 3

What causes severe hyperthyroidism before 20 weeks’ gestation?

| Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis |

| Choriocarcinoma |

Gestational trophoblastic disease

|

Signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease

Women who have Graves’ disease usually have thyroid nodules and may have exophthalmia, pretibial myxedema, and tachycardia. They also display other classic signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as muscle weakness, tremor, and warm and moist skin.

During pregnancy, Graves’ disease usually becomes worse during the first trimester and postpartum period; symptoms resolve during the second and third trimesters.1

Thyrotoxin receptor and antithyroid antibodies

Antithyroid antibodies are common in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, as a response to thyroid antigens. The two most common antithyroid antibodies are thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO). Anti-TPO antibodies are associated with postpartum thyroiditis and fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism. TSH-receptor antibodies include thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) and TSH-receptor antibody. TSI is associated with Graves’ disease. TSH-receptor antibody is associated with fetal goiter, congenital hypothyroidism, and chronic thyroiditis without goiter.4

Who do you test for antibodies? Test for maternal thyroid antibodies in patients who:

- had Graves’ disease with fetal or neonatal hyperthyroidism in a previous pregnancy

- have active Graves’ disease being treated with antithyroid drugs

- are euthyroid or have undergone ablative therapy and have fetal tachycardia or intrauterine growth restriction

- have chronic thyroiditis without goiter

- have fetal goiter on ultrasound.

Newborns who have congenital hypothyroidism should also be screened for thyroid antibodies.4

What are the consequences?

Hyperthyroidism can have multiple effects on the pregnant patient and her fetus, ranging in severity from the minimal to the catastrophic.

Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis

This condition is presumably related to high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, a substance known to stimulate TSH receptors. Unhappily for your patient, the condition is usually heralded by severe bouts of nausea and vomiting starting at 4 to 8 weeks’ gestation. Laboratory tests show significantly elevated levels of FT4 and FT3 and suppressed TSH. Despite this significant derangement, patients generally have no evidence of a hypermetabolic state.

This condition resolves by 14 to 20 weeks of gestation, is not associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, and does not require treatment with antithyroid medication.1

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Pregnant women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism are at increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage, congestive heart failure, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia.1 Studies that evaluated pregnancy outcomes in 239 women with overt hyperthyroidism showed increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, compared with treated, euthyroid women (FIGURE 1).5-7

FIGURE 1 Consequences of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism

Several studies have found a much higher risk of pregnancy complications in women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, compared with their treated and euthyroid peers.5-7

PTD=preterm delivery; FGR=fetal growth restrictions.

Fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism in the fetus or newborn is caused by placental transfer of maternal immunoglobulin antibodies (TSI) to the fetus and is associated with maternal Graves’ disease. The incidence of neonatal hyperthyroidism is less than 1%. It can be predicted by rising levels of maternal TSI antibodies, to the point where levels in the third trimester are three to five times higher than they were at the beginning of pregnancy.4

Fetal hyperthyroidism develops at about 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation in mothers with a history of Graves’ disease who have been treated surgically or with ablative therapy prior to pregnancy. Even when these therapies achieve a euthyroid state in the mother, TSI levels may remain elevated and lead to fetal hyperthyroidism.

Characteristics of hyperthyroidism in the fetus include tachycardia, intrauterine growth restriction, congestive heart failure, oligohydramnios, and goiter. Treating the mother with antithyroid medications will ameliorate symptoms in the fetus.4

Thyroid storm

This is the worst-case scenario—a rare but potentially lethal complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism. Thyroid storm is a hypermetabolic state characterized by fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, altered mental status, restlessness, nervousness, seizures, coma, and cardiac arrhythmias. It occurs in 1% to 2% of patients receiving thioamide therapy.8

In most instances, thyroid storm is a complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, but it can also be precipitated by infection, surgery, thromboembolism, preeclampsia, labor, and delivery.

Thyroid storm is a medical emergency

This manifestation of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism is so urgent that treatment should be initiated before the results of TSH, FT4, and FT3 tests are available.2,8 Delivery should be avoided, if possible, until the mother’s condition can be stabilized but, if the status of the fetus is compromised, delivery is indicated.

Treatment of thyroid storm begins with stabilization of the patient, followed by initiation of a stepwise management approach (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2 Management of thyroid storm

Aggressive management of thyroid storm is indicated, following a stepwise approach. Each medication used to treat thyroid storm plays a specific role in suppressing thyroid function. Propylthiouracil (PTU) blocks additional synthesis of thyroid hormone and inhibits the conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3). Methimazole blocks additional synthesis of thyroid hormones. Saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI), Lugol’s solution, and sodium iodide block the release of thyroid hormone from the gland. Dexamethasone is used to decrease thyroid hormone release and peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. Propranolol is used to treat maternal tachycardia by inhibiting the adrenergic effects of excessive thyroid hormones. Finally, phenobarbital is used to treat maternal agitation and restlessness caused by the increased catabolism of thyroid hormones.

SOURCE: Adapted from ACOG.2

Treatment of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

Two medications are available to treat hyperthyroidism in pregnancy: propylthiouracil (PTU) and methimazole. These medications are known as thioamides.1,2

PTU blocks the oxidation of iodine in the thyroid gland, thereby preventing the synthesis of T4 and T3. The initial dosage for hyperthyroid women who are not pregnant is usually 300 to 450 mg/day in three divided doses every 8 hours, and this dosing strategy can also be applied to the pregnant patient. Maintenance therapy is usually achieved with 100 to 150 mg/day in divided doses every 8 to 12 hours.9

Methimazole works by blocking the organification of iodide, which decreases thyroid hormone production. The usual dosing, given in three divided doses every 8 hours, is 15 mg/day for mild hyperthyroidism, 30 to 40 mg/day for moderately severe hyperthyroidism, and 60 mg/day for severe hyperthyroidism. Maintenance therapy with methimazole is usually given at a dosage of 5 to 15 mg/day.9

In the past, PTU was considered the drug of choice for treatment of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy because clinicians believed it crossed the placenta to a lesser degree than did methimazole, and because methimazole was associated with fetal esophageal and choanal atresia and fetal cutis aplasia (congenital skin defect of the scalp).1,2 Available evidence does not, however, support these conclusions.8,10 Whatever medication regimen you choose, thyroid function should be monitored 1) every 4 weeks until TSH and FT4 levels are within normal limits and 2) every trimester thereafter. FIGURE 3 presents an algorithm for managing hyperthyroidism in pregnancy.

FIGURE 3 Management of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

CASE Resolved

The patient in thyroid storm described at the beginning of this article requires aggressive management, as outlined in the algorithm in FIGURE 2. As her symptoms diminish, fetal tachycardia resolves. The patient’s FT4 level begins to decline, consistent with appropriate treatment, and she is discharged home and instructed to continue PTU and labetalol and to follow up at the endocrinology and high-risk obstetrics clinics as soon as possible.

The patient does not follow this advice. Consequently, she presents at 33 5/7 weeks in a hypertensive crisis, with symptoms similar to those she first exhibited plus acute pulmonary edema. Fetal heart rate is initially in the 130s, with good variability and occasional decelerations (FIGURE 4A), but decelerations then become worse (FIGURE 4B) and emergency cesarean section is performed.

A male infant is delivered, weighing 2,390 g. Apgar scores are 0 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. A 25% placental abruption is noted at the time of delivery.

Mother and fetus are stabilized and discharged.

FIGURE 4 Weakening fetal status in a mother who is in thyroid storm

Fetal heart rate is initially in the 130s with good variability and occasional decelerations (A), but then deteriorates, with increasing decelerations (B), an indication for immediate delivery.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE Life on the line

A 32-year-old woman in the 24th week of her fourth pregnancy arrives at the emergency department complaining of cough and congestion, shortness of breath, and swelling in her face, hands, and feet. The swelling has become worse over the past 2 weeks, and she had several episodes of bloody vomiting the day before her visit. The patient says she has not experienced any leakage of fluid, vaginal bleeding, or contractions. She reports good fetal movement.

The patient’s medical history is unremarkable, but a review of systems reveals a 15-lb weight loss over the past 2 weeks, racing heart, worsening edema and shortness of breath, and diarrhea.

Physical findings include exophthalmia and an enlarged thyroid with a nodule on the right side, as well as bilateral rales, tachycardia, tremor, and increased deep tendon reflexes. There is no evidence of fetal cardiac failure or goiter.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the mother shows bilateral pleural effusions indicative of high-output cardiac failure. Thyroid ultrasonography (US) reveals a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with a right-sided mass.

The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level is undetectable. Fetal heart rate is in the 160s, with normal variability and occasional variable deceleration. Fetal US is consistent with the estimated gestational age and shows adequate amniotic fluid and no gross fetal anomalies.

What is the likely diagnosis?

This is a classic example of undiagnosed hyperthyroidism in pregnancy manifesting as thyroid storm.

As the case illustrates, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism in pregnancy poses a significant challenge for the obstetrician. The condition can cause miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, and—at its most dangerous—thyroid storm.1 Thyroid storm is a life-threatening emergency, and treatment must be initiated even before hyperthyroidism is confirmed by thyroid function testing.2 The good news is that these complications can be successfully avoided with adequate control of thyroid function.

Overt hyperthyroidism, seen in 0.2% of pregnancies, requires active intervention to avert adverse pregnancy outcome and neurologic damage to the fetus. Subclinical disease, seen in 1.7% of pregnancies, can also create serious obstetrical problems.1

The effects of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy vary in severity, ranging from the fairly innocuous, transient, and self-limited state called gestational transient thyrotoxicosis to the life-threatening emergency of thyroid storm. This review will update you on how to manage this disorder for optimal pregnancy outcome.

To screen or not to screen

Routine screening for thyroid dysfunction has been recommended for women who have infertility, menstrual disorders, or type 1 diabetes mellitus, and for pregnant women who have signs and symptoms of the disorder. Some authors recommend screening all pregnant women, but routine screening is not endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.2,3

Thyroid testing in pregnancy is recommended in women who:

- have a family history of autoimmune thyroid disease

- are on thyroid therapy

- have a goiter or

- have insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Pregnant women who have a history of high-dose neck radiation, thyroid therapy, postpartum thyroiditis, or an infant born with thyroid disease should also be tested at the first prenatal visit.4

Telltale signs and laboratory tests

The signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism can include nervousness, heat intolerance, tachycardia, palpitations, goiter, weight loss, thyromegaly, exophthalmia, increased appetite, nausea and vomiting, sweating, and tremor.1 The difficulty here? Many of these symptoms are also seen in pregnant women who have normal thyroid function, so that symptoms alone are not a reliable guide.

Instead, the diagnosis of overt hyperthyroidism is made on the basis of laboratory tests indicating suppressed TSH and elevated levels of free thyroxine (FT4) and free triiodothyronine (FT3). Subclinical hyperthyroidism is defined as a suppressed TSH level with normal FT4 and FT3 levels.2

The effects of hyperthyroidism on laboratory values are shown in TABLE 1. A form of hyperthyroidism called the T3– toxicosis syndrome is diagnosed by suppressed TSH, normal FT4, and elevated FT3 levels.4

TABLE 1

Is your pregnant patient hyperthyroid? Five-test lab panel offers a guide

| TEST AND RESULT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THYROID-STIMULATING HORMONE | FREE TRI-IODOTHYRONINE | FREE THYROXINE | TOTAL TRI-IODOTHYRONINE | TOTAL THYROXINE | THEN THE MOTHER’S CONDITION IS … |

| No change | No change | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Pregnancy |

| ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Hyperthyroidism |

| ↓ | No change | No change | No change | No change | Subclinical hyperthyroidism |

What are the causes?

The most common cause of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy—accounting for some 95% of cases—is Graves’ disease.2 This autoimmune disorder is characterized by autoantibodies that activate the TSH receptor. These autoantibodies cross the placenta and can cause fetal and neonatal thyroid dysfunction even when the mother herself is in a euthyroid condition.4

Far less often, hyperthyroidism in pregnancy has a cause other than Graves’ disease; TABLE 2 summarizes the possibilities.1 Other causes of hyperthyroidism in early pregnancy include choriocarcinoma and gestational trophoblastic disease (partial and complete moles) (TABLE 3).

TABLE 2

Causes of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

| Graves’ disease |

| Adenoma |

| Toxic nodular goiter |

| Thyroiditis |

| Excessive thyroid hormone intake |

| Choriocarcinoma |

| Molar pregnancy |

TABLE 3

What causes severe hyperthyroidism before 20 weeks’ gestation?

| Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis |

| Choriocarcinoma |

Gestational trophoblastic disease

|

Signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease

Women who have Graves’ disease usually have thyroid nodules and may have exophthalmia, pretibial myxedema, and tachycardia. They also display other classic signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as muscle weakness, tremor, and warm and moist skin.

During pregnancy, Graves’ disease usually becomes worse during the first trimester and postpartum period; symptoms resolve during the second and third trimesters.1

Thyrotoxin receptor and antithyroid antibodies

Antithyroid antibodies are common in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, as a response to thyroid antigens. The two most common antithyroid antibodies are thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO). Anti-TPO antibodies are associated with postpartum thyroiditis and fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism. TSH-receptor antibodies include thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) and TSH-receptor antibody. TSI is associated with Graves’ disease. TSH-receptor antibody is associated with fetal goiter, congenital hypothyroidism, and chronic thyroiditis without goiter.4

Who do you test for antibodies? Test for maternal thyroid antibodies in patients who:

- had Graves’ disease with fetal or neonatal hyperthyroidism in a previous pregnancy

- have active Graves’ disease being treated with antithyroid drugs

- are euthyroid or have undergone ablative therapy and have fetal tachycardia or intrauterine growth restriction

- have chronic thyroiditis without goiter

- have fetal goiter on ultrasound.

Newborns who have congenital hypothyroidism should also be screened for thyroid antibodies.4

What are the consequences?

Hyperthyroidism can have multiple effects on the pregnant patient and her fetus, ranging in severity from the minimal to the catastrophic.

Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis

This condition is presumably related to high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, a substance known to stimulate TSH receptors. Unhappily for your patient, the condition is usually heralded by severe bouts of nausea and vomiting starting at 4 to 8 weeks’ gestation. Laboratory tests show significantly elevated levels of FT4 and FT3 and suppressed TSH. Despite this significant derangement, patients generally have no evidence of a hypermetabolic state.

This condition resolves by 14 to 20 weeks of gestation, is not associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, and does not require treatment with antithyroid medication.1

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Pregnant women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism are at increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage, congestive heart failure, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia.1 Studies that evaluated pregnancy outcomes in 239 women with overt hyperthyroidism showed increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, compared with treated, euthyroid women (FIGURE 1).5-7

FIGURE 1 Consequences of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism

Several studies have found a much higher risk of pregnancy complications in women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, compared with their treated and euthyroid peers.5-7

PTD=preterm delivery; FGR=fetal growth restrictions.

Fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism in the fetus or newborn is caused by placental transfer of maternal immunoglobulin antibodies (TSI) to the fetus and is associated with maternal Graves’ disease. The incidence of neonatal hyperthyroidism is less than 1%. It can be predicted by rising levels of maternal TSI antibodies, to the point where levels in the third trimester are three to five times higher than they were at the beginning of pregnancy.4

Fetal hyperthyroidism develops at about 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation in mothers with a history of Graves’ disease who have been treated surgically or with ablative therapy prior to pregnancy. Even when these therapies achieve a euthyroid state in the mother, TSI levels may remain elevated and lead to fetal hyperthyroidism.

Characteristics of hyperthyroidism in the fetus include tachycardia, intrauterine growth restriction, congestive heart failure, oligohydramnios, and goiter. Treating the mother with antithyroid medications will ameliorate symptoms in the fetus.4

Thyroid storm

This is the worst-case scenario—a rare but potentially lethal complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism. Thyroid storm is a hypermetabolic state characterized by fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, altered mental status, restlessness, nervousness, seizures, coma, and cardiac arrhythmias. It occurs in 1% to 2% of patients receiving thioamide therapy.8

In most instances, thyroid storm is a complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, but it can also be precipitated by infection, surgery, thromboembolism, preeclampsia, labor, and delivery.

Thyroid storm is a medical emergency

This manifestation of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism is so urgent that treatment should be initiated before the results of TSH, FT4, and FT3 tests are available.2,8 Delivery should be avoided, if possible, until the mother’s condition can be stabilized but, if the status of the fetus is compromised, delivery is indicated.

Treatment of thyroid storm begins with stabilization of the patient, followed by initiation of a stepwise management approach (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2 Management of thyroid storm

Aggressive management of thyroid storm is indicated, following a stepwise approach. Each medication used to treat thyroid storm plays a specific role in suppressing thyroid function. Propylthiouracil (PTU) blocks additional synthesis of thyroid hormone and inhibits the conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3). Methimazole blocks additional synthesis of thyroid hormones. Saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI), Lugol’s solution, and sodium iodide block the release of thyroid hormone from the gland. Dexamethasone is used to decrease thyroid hormone release and peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. Propranolol is used to treat maternal tachycardia by inhibiting the adrenergic effects of excessive thyroid hormones. Finally, phenobarbital is used to treat maternal agitation and restlessness caused by the increased catabolism of thyroid hormones.

SOURCE: Adapted from ACOG.2

Treatment of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

Two medications are available to treat hyperthyroidism in pregnancy: propylthiouracil (PTU) and methimazole. These medications are known as thioamides.1,2

PTU blocks the oxidation of iodine in the thyroid gland, thereby preventing the synthesis of T4 and T3. The initial dosage for hyperthyroid women who are not pregnant is usually 300 to 450 mg/day in three divided doses every 8 hours, and this dosing strategy can also be applied to the pregnant patient. Maintenance therapy is usually achieved with 100 to 150 mg/day in divided doses every 8 to 12 hours.9

Methimazole works by blocking the organification of iodide, which decreases thyroid hormone production. The usual dosing, given in three divided doses every 8 hours, is 15 mg/day for mild hyperthyroidism, 30 to 40 mg/day for moderately severe hyperthyroidism, and 60 mg/day for severe hyperthyroidism. Maintenance therapy with methimazole is usually given at a dosage of 5 to 15 mg/day.9

In the past, PTU was considered the drug of choice for treatment of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy because clinicians believed it crossed the placenta to a lesser degree than did methimazole, and because methimazole was associated with fetal esophageal and choanal atresia and fetal cutis aplasia (congenital skin defect of the scalp).1,2 Available evidence does not, however, support these conclusions.8,10 Whatever medication regimen you choose, thyroid function should be monitored 1) every 4 weeks until TSH and FT4 levels are within normal limits and 2) every trimester thereafter. FIGURE 3 presents an algorithm for managing hyperthyroidism in pregnancy.

FIGURE 3 Management of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

CASE Resolved

The patient in thyroid storm described at the beginning of this article requires aggressive management, as outlined in the algorithm in FIGURE 2. As her symptoms diminish, fetal tachycardia resolves. The patient’s FT4 level begins to decline, consistent with appropriate treatment, and she is discharged home and instructed to continue PTU and labetalol and to follow up at the endocrinology and high-risk obstetrics clinics as soon as possible.

The patient does not follow this advice. Consequently, she presents at 33 5/7 weeks in a hypertensive crisis, with symptoms similar to those she first exhibited plus acute pulmonary edema. Fetal heart rate is initially in the 130s, with good variability and occasional decelerations (FIGURE 4A), but decelerations then become worse (FIGURE 4B) and emergency cesarean section is performed.

A male infant is delivered, weighing 2,390 g. Apgar scores are 0 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. A 25% placental abruption is noted at the time of delivery.

Mother and fetus are stabilized and discharged.

FIGURE 4 Weakening fetal status in a mother who is in thyroid storm

Fetal heart rate is initially in the 130s with good variability and occasional decelerations (A), but then deteriorates, with increasing decelerations (B), an indication for immediate delivery.

1. Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1283-1292.

2. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 37, August 2002. (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 32, November 2001). Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:387-396.

3. Mitchell ML, Klein RZ. The sequelae of untreated maternal hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151 Suppl 3:U45-48.

4. Mestman JH. Endocrine diseases in pregnancy. In: Gabbe S, Niebyl JR, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:1117-1168.

5. Davis LE, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. Hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:108-112.

6. Davis LE, Lucas MJ, Hankins GD, Roark ML, Cunningham FG. Thyrotoxicosis complicating pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:63-70.

7. Kriplani A, Buckshee K, Bhargava VL, Takkar D, Ammini AC. Maternal and perinatal outcome in thyrotoxicosis complicating pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;54:159-163.

8. Belford MA. Navigating a thyroid storm. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2006; October:38–46.

9. Lazarus JH, Othman S. Thyroid disease in relation to pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1991;34:91-98.

10. Kent GN, Stuckey BG, Allen JR, Lambert T, Gee V. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction: clinical assessment and relationship to psychiatric affective morbidity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;51:429-438.

1. Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1283-1292.

2. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 37, August 2002. (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 32, November 2001). Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:387-396.

3. Mitchell ML, Klein RZ. The sequelae of untreated maternal hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151 Suppl 3:U45-48.

4. Mestman JH. Endocrine diseases in pregnancy. In: Gabbe S, Niebyl JR, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:1117-1168.

5. Davis LE, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. Hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:108-112.

6. Davis LE, Lucas MJ, Hankins GD, Roark ML, Cunningham FG. Thyrotoxicosis complicating pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:63-70.

7. Kriplani A, Buckshee K, Bhargava VL, Takkar D, Ammini AC. Maternal and perinatal outcome in thyrotoxicosis complicating pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;54:159-163.

8. Belford MA. Navigating a thyroid storm. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2006; October:38–46.

9. Lazarus JH, Othman S. Thyroid disease in relation to pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1991;34:91-98.

10. Kent GN, Stuckey BG, Allen JR, Lambert T, Gee V. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction: clinical assessment and relationship to psychiatric affective morbidity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;51:429-438.