User login

Despite advancements in techniques, postsurgical pain continues to be a prominent part of the patient experience. Often this experience can lead to developing chronic postsurgical pain that interferes with quality of life after the expected time to recovery.1-3 As many as 14% of patients who undergo surgery without any history of opioid use develop chronic opioid use that persists after recovery from their operation.4-8 For patients with existing chronic opioid use or a history of substance use disorder (SUD), surgeons, primary care providers, or addiction providers often do not provide sufficient presurgical planning or postsurgical coordination of care. This lack of pain care coordination can increase the risk of inadequate pain control, opioid use escalation, or SUD relapse after surgery.

Convincing arguments have been made that a perioperative surgical home can improve significantly the quality of perioperative care.9-14 This report describes our experience implementing a perioperative surgical home at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Salt Lake City VA Medical Center (SLCVAMC), focusing on pain management extending from the preoperative period until 6 months or more after surgery. This type of Transitional Pain Service (TPS) has been described previously.15-17 Our service differs from those described previously by enrolling all patients before surgery rather than select postsurgical enrollment of only patients with a history of opioid use or SUD or patients who struggle with persistent postsurgical pain.

Methods

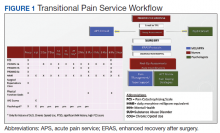

In January 2018, we developed and implemented a new TPS at the SLCVAMC. The transitional pain team consisted of an anesthesiologist with specialization in acute pain management, a nurse practitioner (NP) with experience in both acute and chronic pain management, 2 nurse care coordinators, and a psychologist (Figure 1). Before implementation, a needs assessment took place with these key stakeholders and others at SLCVAMC to identify the following specific goals of the TPS: (1) reduce pain through pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions; (2) eliminate new chronic opioid use in previously nonopioid user (NOU) patients; (3) address chronic opioid use in previous chronic opioid users (COUs) by providing support for opioid taper and alternative analgesic therapies for their chronic pain conditions; and (4) improve continuity of care by close coordination with the surgical team, primary care providers (PCPs), and mental health or chronic pain providers as needed.

Once these TPS goals were defined, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) guided the implementation. CFIR is a theory-based implementation framework consisting of 5 domains: intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals, and process. These domains were used to identify barriers and facilitators during the early implementation process and helped refine TPS as it was put into clinical practice.

Patient Selection

During the initial implementation of TPS, enrollment was limited to patients scheduled for elective primary or revision knee, hip, or shoulder replacement as well as rotator cuff repair surgery. But as the TPS workflow became established after iterative refinement, we expanded the program to enroll patients with established risk factors for OUD having other types of surgery (Table 1). The diagnosis of risk factors, such as history of SUD, chronic opioid use, or significant mental health disorders (ie, history of suicidal ideation or attempt, posttraumatic stress disorder, and inpatient psychiatric care) were confirmed through both in-person interviews and electronic health record (EHR) documentation. The overall goal was to identify all at-risk patients as soon as they were indicated for surgery, to allow time for evaluation, education, developing an individualized pain plan, and opioid taper prior to surgery if indicated.

Preoperative Procedures

Once identified, patients were contacted by a TPS team member and invited to attend a onetime 90-minute presurgical expectations class held at SLCVAMC. The education curriculum was developed by the whole team, and classes were taught primarily by the TPS psychologist. The class included education about expectations for postoperative pain, available analgesic therapies, opioid education, appropriate use of opioids, and the effect of psychological factors on pain. Pain coping strategies were introduced using a mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) and the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) matrix. Classes were offered multiple times a week to help maximize convenience for patients and were separate from the anesthesia preoperative evaluation. Patients attended class only once. High-risk patients (patients with chronic opioid therapy, recent history of or current SUDs, significant comorbid mental health issues) were encouraged to attend this class one-on-one with the TPS psychologist rather than in the group setting, so individual attention to mental health and SUD issues could be addressed directly.

Baseline history, morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and patient-reported outcomes using measures from the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS) for pain intensity (PROMIS 3a), pain interference (PROMIS 6b), and physical function (PROMIS 8b), and a pain-catastrophizing scale (PCS) score were obtained on all patients.18 PROMIS measures are validated questionnaires developed with the National Institutes of Health to standardize and quantify patient-reported outcomes in many domains.19 Patients with a history of SUD or COU met with the anesthesiologist and/or NP, and a personalized pain plan was developed that included preoperative opioid taper, buprenorphine use strategy, or opioid-free strategies.

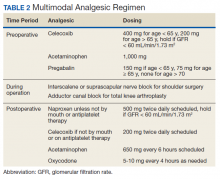

Hospital Procedures

On the day of surgery, the TPS team met with the patient preoperatively and implemented an individualized pain plan that included multimodal analgesic techniques with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, and regional anesthesia, where appropriate (Table 2). Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols were developed in conjunction with the surgeons to include local infiltration analgesia by the surgeon, postoperative multimodal analgesic strategies, and intensive physical therapy starting the day of surgery for inpatient procedures.

After surgery, the TPS team followed up with patients daily and provided recommendations for analgesic therapies. Patients were offered daily sessions with the psychologist to reinforce and practice nonpharmacologic pain-coping strategies, such as meditation and relaxation. Prior to patient discharge, the TPS team provided recommendations for discharge medications and an opioid taper plan. For some patients taking buprenorphine before surgery who had stopped this therapy prior to or during their hospital stay, TPS providers transitioned them back to buprenorphine before discharge.

Postoperative Procedures

Patients were called by the nurse care coordinators at postdischarge days 2, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, and then monthly for ≥ 6 months. For patients who had not stopped opioid use or returned to their preoperative baseline opioid dose, weekly calls were made until opioid taper goals were achieved. At each call, nurses collected PROMIS scores for the previous 24 hours, the most recent 24-hour MEDD, the date of last opioid use, and the number of remaining opioid tablets after opioid cessation. In addition, nurses provided active listening and supportive care and encouragement as well as care coordination for issues related to rehabilitation facilities, physical therapy, transportation, medication questions, and wound questions. Nurses notified the anesthesiologist or NP when patients were unable to taper opioid use or had poor pain control as indicated by their PROMIS scores, opioid use, or directly expressed by the patient.

The TPS team prescribed alternative analgesic therapies, opioid taper plans, and communicated with surgeons and primary care providers if limited continued opioid therapy was recommended. Individual sessions with the psychologist were available to patients after discharge with a focus on ACT-matrix therapy and consultation with long-term mental health and/or substance abuse providers as indicated. Frequent communication and care coordination were maintained with the surgical team, the PCP, and other providers on the mental health or chronic pain services. This care coordination often included postsurgical joint clinic appointments in which TPS providers and nurses would be present with the surgeon or the PCP.

For patients with inadequately treated chronic pain conditions or who required long-term opioid tapers, we developed a combined clinic with the TPS and Anesthesia Chronic Pain group. This clinic allows patients to be seen by both services in the same setting, allowing a warm handoff by TPS to the chronic pain team.

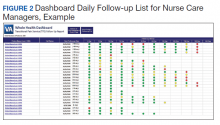

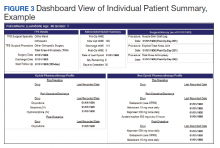

Heath and Decision Support Tools

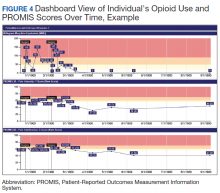

An electronic dashboard registry of surgical episodes managed by TPS was developed to achieve clinical, administrative, and quality improvement goals. The dashboard registry consists of surgical episode data, opioid doses, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical decision-making processes. Custom-built note templates capture pertinent data through embedded data labels, called health factors. Data are captured as part of routine clinical care, recorded in Computerized Patient Record System as health factors. They are available in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse as structured data. Workflows are executed daily to keep the dashboard registry current, clean, and able to process new data. Information displays direct daily clinical workflow and support point-of-care clinical decision making (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Data are aggregated across patient-care encounters and allow nurse care coordinators to concisely review pertinent patient data prior to delivering care. These data include surgical history, comorbidities, timeline of opioid use, and PROMIS scores during their course of recovery. This system allows TPS to optimize care delivery by providing longitudinal data across the surgical episode, thereby reducing the time needed to review records. Secondary purposes of captured data include measuring clinic performance and quality improvement to improve care delivery.

Results

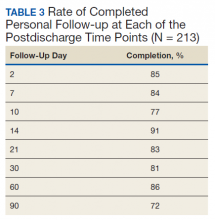

The TPS intervention was implemented January 1, 2018. Two-hundred thirteen patients were enrolled between January and December 2018, which included 60 (28%) patients with a history of chronic opioid use and 153 (72%) patients who were considered opioid naïve. A total of 99% of patients had ≥ 1 successful follow-up within 14 days after discharge, 96% had ≥ 1 follow-up between 14 and 30 days after surgery, and 72% had completed personal follow-up 90 days after discharge (Table 3). For patients who TPS was unable to contact in person or by phone, 90-day MEDD was obtained using prescription and Controlled Substance Database reviews. The protocol for this retrospective analysis was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and the VA Research Review Committee.

By 90 days after surgery, 26 (43.3%) COUs were off opioids completely, 17 (28.3%) had decreased their opioid dose from their preoperative baseline MEDD (120 [SD, 108] vs 55 [SD, 45]), 14 (23.3%) returned to their baseline dose, and 3 (5%) increased from their baseline dose. Of the 153 patients who were NOUs before surgery, only 1 (0.7%) was taking opioids after 90 days. TPS continued to work closely with the patient and their PCP and that patient was finally able to stop opioid use 262 days after discharge. Ten patients had an additional surgery within 90 days of the initial surgery. Of these, 6 were COU, of whom 3 stopped all opioids by 90 days from their original surgery, 2 had no change in MEDD at 90 days, and 1 had a lower MEDD at 90 days. Of the 4 NOU who had additional surgery, all were off opioids by 90 days from the original surgery.

Although difficult to quantify, a meaningful outcome of TPS has been to improve satisfaction substantially among health care providers caring for complex patients at risk for chronic opioid abuse. This group includes the many members of the surgical team, PCPs, and addiction specialists who appreciate the close care coordination and assistance in caring for patients with difficult issues, especially with opioid tapers or SUDs. We also have noticed changes in prescribing practices among surgeons and PCPs for their patients who are not part of TPS.

Discussion

With any new clinical service, there are obstacles and challenges. TPS requires a considerable investment in personnel, and currently no mechanism is in place for obtaining payment for many of the provided services. We were fortunate the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Office of Rural Health, and the VA Centers of Innovation provided support for the development, implementation, and pilot evaluation of TPS. After we presented our initial results to hospital leadership, we also received hospital support to expand TPS service to include a total of 4 nurse care coordinators and 2 psychologists. We are currently performing a cost analysis of the service but recognize that this model may be difficult to reproduce at other institutions without a change in reimbursement standards.

Developing a working relationship with the surgical and primary care services required a concerted effort from the TPS team and a number of months to become effective. As most veterans receive primary care, mental health care, and surgical care within the VA system, this model lends itself to close care coordination. Initially there was skepticism about TPS recommendations to reduce opioid use, especially from PCPs who had cared for complex patients over many years. But this uncertainty went away as we showed evidence of close patient follow-up and detailed communication. TPS soon became the designated service for both primary care and surgical providers who were otherwise uncomfortable with how to approach opioid tapers and nonopioid pain strategies. In fact, a substantial portion of our referrals now come directly from the PCP who is referring a high-risk patient for evaluation for surgery rather than from the surgeons, and joint visits with TPS and primary care have become commonplace.

Challenges abound when working with patients with substance abuse history, opioid use history, high anxiety, significant pain catastrophizing, and those who have had previous negative experiences with surgery. We have found that the most important facet of our service comes from the amount of time and effort team members, especially the nurses, spend helping patients. Much of the nurses' work focuses on nonpain-related issues, such as assisting patients with finding transportation, housing issues, questions about medications, help scheduling appointments, etc. Through this concerted effort, patients gain trust in TPS providers and are willing to listen to and experiment with our recommendations. Many patients who were initially extremely unreceptive to the presurgery education asked for our support weeks after surgery to help with postsurgery pain.

Another challenge we continue to experience comes from the success of the program.

Conclusions

The multidisciplinary TPS supports greater preoperative to postoperative longitudinal care for surgical patients. This endeavor has resulted in better patient preparation before surgery and improved care coordination after surgery, with specific improvements in appropriate use of opioid medications and smooth transitions of care for patients with ongoing and complex needs. Development of sophisticated note templates and customized health information technology allows for accurate follow-through and data gathering for quality improvement, facilitating data-driven improvements and proving value to the facility.

Given that TPS is a multidisciplinary program with multiple interventions, it is difficult to pinpoint which specific aspects of TPS are most effective in achieving success. For example, although we have little doubt that the work our psychologists do with our patients is beneficial and even essential for the success we have had with some of our most difficult patients, it is less clear whether it matters if they use mindfulness, ACT matrix, or cognitive behavioral therapy. We think that an important part of TPS is the frequent human interaction with a caring individual. Therefore, as TPS continues to grow, maintaining the ability to provide frequent personal interaction is a priority.

The role of opioids in acute pain deserves further scrutiny. In 2018, with TPS use of opioids after orthopedic surgery decreased by > 40% from the previous year. Despite this more restricted use of opioids, pain interference and physical function scores indicated that surgical patients do not seem to experience increased pain or reduced physical function. In addition, stopping opioid use for COUs did not seem to affect the quality of recovery, pain, or physical function. Future prospective controlled studies of TPS are needed to confirm these findings and identify which aspects of TPS are most effective in improving functional recovery of patients. Also, more evidence is needed to determine the appropriateness or need for opioids in acute postsurgical pain.

TPS has expanded to include all surgical specialties. Given the high burden and limited resources, we have chosen to focus on patients at higher risk for chronic postsurgical pain by type of surgery (eg, thoracotomy, open abdominal, limb amputation, major joint surgery) and/or history of substance abuse or chronic opioid use. To better direct scarce resources where it would be of most benefit, we are now enrolling only NOUs without other risk factors postoperatively if they request a refill of opioids or are otherwise struggling with pain control after surgery. Whether this approach affects the success we had in the first year in preventing new COUs after surgery remains to be seen.

It is unlikely that any single model of a perioperative surgical home will fit the needs of the many different types of medical systems that exist. The TPS model fits well in large hospital systems, like the VA, where patients receive most of their care within the same system. However, it seems to us that the optimal TPS program in any health system will provide education, support, and care coordination beginning preoperatively to prepare the patient for surgery and then to facilitate care coordination to transition patients back to their PCPs or on to specialized chronic care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Candice Harmon, RN; David Merrill, RN; Amy Beckstead, RN, who have provided invaluable assistance with establishing the TPS program at the VA Salt Lake City and helping with the evaluation process.

Funding for the implementation and evaluation of the TPS was received from the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Center of Innovation, the VA Office of Rural Health, and National Institutes of Health Grant UL1TR002538.

1. Ilfeld BM, Madison SJ, Suresh PJ. Persistent postmastectomy pain and pain-related physical and emotional functioning with and without a continuous paravertebral nerve block: a prospective 1-year follow-up assessment of a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):2017-2025. doi:10.1245/s10434-014-4248-7

2. Richebé P, Capdevila X, Rivat C. Persistent postsurgical pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(3):590-607. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000002238

3. Glare P, Aubrey KR, Myles PS. Transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1537-1546. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30352-6

4. Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surgery. 2017;152(6):e170504-e170504. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504

5. Swenson CW, Kamdar NS, Seiler K, Morgan DM, Lin P, As-Sanie S. Definition development and prevalence of new persistent opioid use following hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(5):486.e1-486.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.010

6. Bartels K, Fernandez-Bustamante A, McWilliams SK, Hopfer CJ, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK. Long-term opioid use after inpatient surgery - a retrospective cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:61-65. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.013

7. Bedard N, DeMik D, Dowdle S, Callaghan J. Trends and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(1)(suppl A):62-67. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.100b1.bjj-2017-0547.r1

8. Politzer CS, Kildow BJ, Goltz DE, Green CL, Bolognesi MP, Seyler T. Trends in opioid utilization before and after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7S):S147-S153.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.060

9. Mariano ER, Walters TL, Kim ET, Kain ZN. Why the perioperative surgical home makes sense for Veterans Affairs health care. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(5):1163-1166. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000000712

10. Walters TL, Howard SK, Kou A, et al. Design and implementation of a perioperative surgical home at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;20(2):133-140. doi:10.1177/1089253215607066

11. Walters TL, Mariano ER, Clark DJ. Perioperative surgical home and the integral role of pain medicine. Pain Med. 2015;16(9):1666-1672. doi:10.1111/pme.12796

12. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of the perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000002280

13. Shafer SL. Anesthesia & Analgesia’s 2015 collection on the perioperative surgical home. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(5):966-967. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000000696

14. Wenzel JT, Schwenk ES, Baratta JL, Viscusi ER. Managing opioid-tolerant patients in the perioperative surgical home. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):287-301. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.005

15. Katz J, Weinrib A, Fashler SR, et al. The Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent chronic postsurgical pain. J Pain Res. 2015;8:695-702. doi:10.2147/jpr.s91924

16. Tiippana E, Hamunen K, Heiskanen T, Nieminen T, Kalso E, Kontinen VK. New approach for treatment of prolonged postoperative pain: APS Out-Patient Clinic. Scand J Pain. 2016;12(1):19-24. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.02.008

17. Katz J, Weinrib AZ, Clarke H. Chronic postsurgical pain: from risk factor identification to multidisciplinary management at the Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service. Can J Pain. 2019;3(2):49-58. doi:10.1080/24740527.2019.1574537

18. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524-532. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524

19. HealthMeasures. Intro to PROMIS. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis. Accessed September 28, 2020.

Despite advancements in techniques, postsurgical pain continues to be a prominent part of the patient experience. Often this experience can lead to developing chronic postsurgical pain that interferes with quality of life after the expected time to recovery.1-3 As many as 14% of patients who undergo surgery without any history of opioid use develop chronic opioid use that persists after recovery from their operation.4-8 For patients with existing chronic opioid use or a history of substance use disorder (SUD), surgeons, primary care providers, or addiction providers often do not provide sufficient presurgical planning or postsurgical coordination of care. This lack of pain care coordination can increase the risk of inadequate pain control, opioid use escalation, or SUD relapse after surgery.

Convincing arguments have been made that a perioperative surgical home can improve significantly the quality of perioperative care.9-14 This report describes our experience implementing a perioperative surgical home at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Salt Lake City VA Medical Center (SLCVAMC), focusing on pain management extending from the preoperative period until 6 months or more after surgery. This type of Transitional Pain Service (TPS) has been described previously.15-17 Our service differs from those described previously by enrolling all patients before surgery rather than select postsurgical enrollment of only patients with a history of opioid use or SUD or patients who struggle with persistent postsurgical pain.

Methods

In January 2018, we developed and implemented a new TPS at the SLCVAMC. The transitional pain team consisted of an anesthesiologist with specialization in acute pain management, a nurse practitioner (NP) with experience in both acute and chronic pain management, 2 nurse care coordinators, and a psychologist (Figure 1). Before implementation, a needs assessment took place with these key stakeholders and others at SLCVAMC to identify the following specific goals of the TPS: (1) reduce pain through pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions; (2) eliminate new chronic opioid use in previously nonopioid user (NOU) patients; (3) address chronic opioid use in previous chronic opioid users (COUs) by providing support for opioid taper and alternative analgesic therapies for their chronic pain conditions; and (4) improve continuity of care by close coordination with the surgical team, primary care providers (PCPs), and mental health or chronic pain providers as needed.

Once these TPS goals were defined, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) guided the implementation. CFIR is a theory-based implementation framework consisting of 5 domains: intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals, and process. These domains were used to identify barriers and facilitators during the early implementation process and helped refine TPS as it was put into clinical practice.

Patient Selection

During the initial implementation of TPS, enrollment was limited to patients scheduled for elective primary or revision knee, hip, or shoulder replacement as well as rotator cuff repair surgery. But as the TPS workflow became established after iterative refinement, we expanded the program to enroll patients with established risk factors for OUD having other types of surgery (Table 1). The diagnosis of risk factors, such as history of SUD, chronic opioid use, or significant mental health disorders (ie, history of suicidal ideation or attempt, posttraumatic stress disorder, and inpatient psychiatric care) were confirmed through both in-person interviews and electronic health record (EHR) documentation. The overall goal was to identify all at-risk patients as soon as they were indicated for surgery, to allow time for evaluation, education, developing an individualized pain plan, and opioid taper prior to surgery if indicated.

Preoperative Procedures

Once identified, patients were contacted by a TPS team member and invited to attend a onetime 90-minute presurgical expectations class held at SLCVAMC. The education curriculum was developed by the whole team, and classes were taught primarily by the TPS psychologist. The class included education about expectations for postoperative pain, available analgesic therapies, opioid education, appropriate use of opioids, and the effect of psychological factors on pain. Pain coping strategies were introduced using a mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) and the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) matrix. Classes were offered multiple times a week to help maximize convenience for patients and were separate from the anesthesia preoperative evaluation. Patients attended class only once. High-risk patients (patients with chronic opioid therapy, recent history of or current SUDs, significant comorbid mental health issues) were encouraged to attend this class one-on-one with the TPS psychologist rather than in the group setting, so individual attention to mental health and SUD issues could be addressed directly.

Baseline history, morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and patient-reported outcomes using measures from the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS) for pain intensity (PROMIS 3a), pain interference (PROMIS 6b), and physical function (PROMIS 8b), and a pain-catastrophizing scale (PCS) score were obtained on all patients.18 PROMIS measures are validated questionnaires developed with the National Institutes of Health to standardize and quantify patient-reported outcomes in many domains.19 Patients with a history of SUD or COU met with the anesthesiologist and/or NP, and a personalized pain plan was developed that included preoperative opioid taper, buprenorphine use strategy, or opioid-free strategies.

Hospital Procedures

On the day of surgery, the TPS team met with the patient preoperatively and implemented an individualized pain plan that included multimodal analgesic techniques with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, and regional anesthesia, where appropriate (Table 2). Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols were developed in conjunction with the surgeons to include local infiltration analgesia by the surgeon, postoperative multimodal analgesic strategies, and intensive physical therapy starting the day of surgery for inpatient procedures.

After surgery, the TPS team followed up with patients daily and provided recommendations for analgesic therapies. Patients were offered daily sessions with the psychologist to reinforce and practice nonpharmacologic pain-coping strategies, such as meditation and relaxation. Prior to patient discharge, the TPS team provided recommendations for discharge medications and an opioid taper plan. For some patients taking buprenorphine before surgery who had stopped this therapy prior to or during their hospital stay, TPS providers transitioned them back to buprenorphine before discharge.

Postoperative Procedures

Patients were called by the nurse care coordinators at postdischarge days 2, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, and then monthly for ≥ 6 months. For patients who had not stopped opioid use or returned to their preoperative baseline opioid dose, weekly calls were made until opioid taper goals were achieved. At each call, nurses collected PROMIS scores for the previous 24 hours, the most recent 24-hour MEDD, the date of last opioid use, and the number of remaining opioid tablets after opioid cessation. In addition, nurses provided active listening and supportive care and encouragement as well as care coordination for issues related to rehabilitation facilities, physical therapy, transportation, medication questions, and wound questions. Nurses notified the anesthesiologist or NP when patients were unable to taper opioid use or had poor pain control as indicated by their PROMIS scores, opioid use, or directly expressed by the patient.

The TPS team prescribed alternative analgesic therapies, opioid taper plans, and communicated with surgeons and primary care providers if limited continued opioid therapy was recommended. Individual sessions with the psychologist were available to patients after discharge with a focus on ACT-matrix therapy and consultation with long-term mental health and/or substance abuse providers as indicated. Frequent communication and care coordination were maintained with the surgical team, the PCP, and other providers on the mental health or chronic pain services. This care coordination often included postsurgical joint clinic appointments in which TPS providers and nurses would be present with the surgeon or the PCP.

For patients with inadequately treated chronic pain conditions or who required long-term opioid tapers, we developed a combined clinic with the TPS and Anesthesia Chronic Pain group. This clinic allows patients to be seen by both services in the same setting, allowing a warm handoff by TPS to the chronic pain team.

Heath and Decision Support Tools

An electronic dashboard registry of surgical episodes managed by TPS was developed to achieve clinical, administrative, and quality improvement goals. The dashboard registry consists of surgical episode data, opioid doses, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical decision-making processes. Custom-built note templates capture pertinent data through embedded data labels, called health factors. Data are captured as part of routine clinical care, recorded in Computerized Patient Record System as health factors. They are available in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse as structured data. Workflows are executed daily to keep the dashboard registry current, clean, and able to process new data. Information displays direct daily clinical workflow and support point-of-care clinical decision making (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Data are aggregated across patient-care encounters and allow nurse care coordinators to concisely review pertinent patient data prior to delivering care. These data include surgical history, comorbidities, timeline of opioid use, and PROMIS scores during their course of recovery. This system allows TPS to optimize care delivery by providing longitudinal data across the surgical episode, thereby reducing the time needed to review records. Secondary purposes of captured data include measuring clinic performance and quality improvement to improve care delivery.

Results

The TPS intervention was implemented January 1, 2018. Two-hundred thirteen patients were enrolled between January and December 2018, which included 60 (28%) patients with a history of chronic opioid use and 153 (72%) patients who were considered opioid naïve. A total of 99% of patients had ≥ 1 successful follow-up within 14 days after discharge, 96% had ≥ 1 follow-up between 14 and 30 days after surgery, and 72% had completed personal follow-up 90 days after discharge (Table 3). For patients who TPS was unable to contact in person or by phone, 90-day MEDD was obtained using prescription and Controlled Substance Database reviews. The protocol for this retrospective analysis was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and the VA Research Review Committee.

By 90 days after surgery, 26 (43.3%) COUs were off opioids completely, 17 (28.3%) had decreased their opioid dose from their preoperative baseline MEDD (120 [SD, 108] vs 55 [SD, 45]), 14 (23.3%) returned to their baseline dose, and 3 (5%) increased from their baseline dose. Of the 153 patients who were NOUs before surgery, only 1 (0.7%) was taking opioids after 90 days. TPS continued to work closely with the patient and their PCP and that patient was finally able to stop opioid use 262 days after discharge. Ten patients had an additional surgery within 90 days of the initial surgery. Of these, 6 were COU, of whom 3 stopped all opioids by 90 days from their original surgery, 2 had no change in MEDD at 90 days, and 1 had a lower MEDD at 90 days. Of the 4 NOU who had additional surgery, all were off opioids by 90 days from the original surgery.

Although difficult to quantify, a meaningful outcome of TPS has been to improve satisfaction substantially among health care providers caring for complex patients at risk for chronic opioid abuse. This group includes the many members of the surgical team, PCPs, and addiction specialists who appreciate the close care coordination and assistance in caring for patients with difficult issues, especially with opioid tapers or SUDs. We also have noticed changes in prescribing practices among surgeons and PCPs for their patients who are not part of TPS.

Discussion

With any new clinical service, there are obstacles and challenges. TPS requires a considerable investment in personnel, and currently no mechanism is in place for obtaining payment for many of the provided services. We were fortunate the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Office of Rural Health, and the VA Centers of Innovation provided support for the development, implementation, and pilot evaluation of TPS. After we presented our initial results to hospital leadership, we also received hospital support to expand TPS service to include a total of 4 nurse care coordinators and 2 psychologists. We are currently performing a cost analysis of the service but recognize that this model may be difficult to reproduce at other institutions without a change in reimbursement standards.

Developing a working relationship with the surgical and primary care services required a concerted effort from the TPS team and a number of months to become effective. As most veterans receive primary care, mental health care, and surgical care within the VA system, this model lends itself to close care coordination. Initially there was skepticism about TPS recommendations to reduce opioid use, especially from PCPs who had cared for complex patients over many years. But this uncertainty went away as we showed evidence of close patient follow-up and detailed communication. TPS soon became the designated service for both primary care and surgical providers who were otherwise uncomfortable with how to approach opioid tapers and nonopioid pain strategies. In fact, a substantial portion of our referrals now come directly from the PCP who is referring a high-risk patient for evaluation for surgery rather than from the surgeons, and joint visits with TPS and primary care have become commonplace.

Challenges abound when working with patients with substance abuse history, opioid use history, high anxiety, significant pain catastrophizing, and those who have had previous negative experiences with surgery. We have found that the most important facet of our service comes from the amount of time and effort team members, especially the nurses, spend helping patients. Much of the nurses' work focuses on nonpain-related issues, such as assisting patients with finding transportation, housing issues, questions about medications, help scheduling appointments, etc. Through this concerted effort, patients gain trust in TPS providers and are willing to listen to and experiment with our recommendations. Many patients who were initially extremely unreceptive to the presurgery education asked for our support weeks after surgery to help with postsurgery pain.

Another challenge we continue to experience comes from the success of the program.

Conclusions

The multidisciplinary TPS supports greater preoperative to postoperative longitudinal care for surgical patients. This endeavor has resulted in better patient preparation before surgery and improved care coordination after surgery, with specific improvements in appropriate use of opioid medications and smooth transitions of care for patients with ongoing and complex needs. Development of sophisticated note templates and customized health information technology allows for accurate follow-through and data gathering for quality improvement, facilitating data-driven improvements and proving value to the facility.

Given that TPS is a multidisciplinary program with multiple interventions, it is difficult to pinpoint which specific aspects of TPS are most effective in achieving success. For example, although we have little doubt that the work our psychologists do with our patients is beneficial and even essential for the success we have had with some of our most difficult patients, it is less clear whether it matters if they use mindfulness, ACT matrix, or cognitive behavioral therapy. We think that an important part of TPS is the frequent human interaction with a caring individual. Therefore, as TPS continues to grow, maintaining the ability to provide frequent personal interaction is a priority.

The role of opioids in acute pain deserves further scrutiny. In 2018, with TPS use of opioids after orthopedic surgery decreased by > 40% from the previous year. Despite this more restricted use of opioids, pain interference and physical function scores indicated that surgical patients do not seem to experience increased pain or reduced physical function. In addition, stopping opioid use for COUs did not seem to affect the quality of recovery, pain, or physical function. Future prospective controlled studies of TPS are needed to confirm these findings and identify which aspects of TPS are most effective in improving functional recovery of patients. Also, more evidence is needed to determine the appropriateness or need for opioids in acute postsurgical pain.

TPS has expanded to include all surgical specialties. Given the high burden and limited resources, we have chosen to focus on patients at higher risk for chronic postsurgical pain by type of surgery (eg, thoracotomy, open abdominal, limb amputation, major joint surgery) and/or history of substance abuse or chronic opioid use. To better direct scarce resources where it would be of most benefit, we are now enrolling only NOUs without other risk factors postoperatively if they request a refill of opioids or are otherwise struggling with pain control after surgery. Whether this approach affects the success we had in the first year in preventing new COUs after surgery remains to be seen.

It is unlikely that any single model of a perioperative surgical home will fit the needs of the many different types of medical systems that exist. The TPS model fits well in large hospital systems, like the VA, where patients receive most of their care within the same system. However, it seems to us that the optimal TPS program in any health system will provide education, support, and care coordination beginning preoperatively to prepare the patient for surgery and then to facilitate care coordination to transition patients back to their PCPs or on to specialized chronic care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Candice Harmon, RN; David Merrill, RN; Amy Beckstead, RN, who have provided invaluable assistance with establishing the TPS program at the VA Salt Lake City and helping with the evaluation process.

Funding for the implementation and evaluation of the TPS was received from the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Center of Innovation, the VA Office of Rural Health, and National Institutes of Health Grant UL1TR002538.

Despite advancements in techniques, postsurgical pain continues to be a prominent part of the patient experience. Often this experience can lead to developing chronic postsurgical pain that interferes with quality of life after the expected time to recovery.1-3 As many as 14% of patients who undergo surgery without any history of opioid use develop chronic opioid use that persists after recovery from their operation.4-8 For patients with existing chronic opioid use or a history of substance use disorder (SUD), surgeons, primary care providers, or addiction providers often do not provide sufficient presurgical planning or postsurgical coordination of care. This lack of pain care coordination can increase the risk of inadequate pain control, opioid use escalation, or SUD relapse after surgery.

Convincing arguments have been made that a perioperative surgical home can improve significantly the quality of perioperative care.9-14 This report describes our experience implementing a perioperative surgical home at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Salt Lake City VA Medical Center (SLCVAMC), focusing on pain management extending from the preoperative period until 6 months or more after surgery. This type of Transitional Pain Service (TPS) has been described previously.15-17 Our service differs from those described previously by enrolling all patients before surgery rather than select postsurgical enrollment of only patients with a history of opioid use or SUD or patients who struggle with persistent postsurgical pain.

Methods

In January 2018, we developed and implemented a new TPS at the SLCVAMC. The transitional pain team consisted of an anesthesiologist with specialization in acute pain management, a nurse practitioner (NP) with experience in both acute and chronic pain management, 2 nurse care coordinators, and a psychologist (Figure 1). Before implementation, a needs assessment took place with these key stakeholders and others at SLCVAMC to identify the following specific goals of the TPS: (1) reduce pain through pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions; (2) eliminate new chronic opioid use in previously nonopioid user (NOU) patients; (3) address chronic opioid use in previous chronic opioid users (COUs) by providing support for opioid taper and alternative analgesic therapies for their chronic pain conditions; and (4) improve continuity of care by close coordination with the surgical team, primary care providers (PCPs), and mental health or chronic pain providers as needed.

Once these TPS goals were defined, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) guided the implementation. CFIR is a theory-based implementation framework consisting of 5 domains: intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals, and process. These domains were used to identify barriers and facilitators during the early implementation process and helped refine TPS as it was put into clinical practice.

Patient Selection

During the initial implementation of TPS, enrollment was limited to patients scheduled for elective primary or revision knee, hip, or shoulder replacement as well as rotator cuff repair surgery. But as the TPS workflow became established after iterative refinement, we expanded the program to enroll patients with established risk factors for OUD having other types of surgery (Table 1). The diagnosis of risk factors, such as history of SUD, chronic opioid use, or significant mental health disorders (ie, history of suicidal ideation or attempt, posttraumatic stress disorder, and inpatient psychiatric care) were confirmed through both in-person interviews and electronic health record (EHR) documentation. The overall goal was to identify all at-risk patients as soon as they were indicated for surgery, to allow time for evaluation, education, developing an individualized pain plan, and opioid taper prior to surgery if indicated.

Preoperative Procedures

Once identified, patients were contacted by a TPS team member and invited to attend a onetime 90-minute presurgical expectations class held at SLCVAMC. The education curriculum was developed by the whole team, and classes were taught primarily by the TPS psychologist. The class included education about expectations for postoperative pain, available analgesic therapies, opioid education, appropriate use of opioids, and the effect of psychological factors on pain. Pain coping strategies were introduced using a mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) and the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) matrix. Classes were offered multiple times a week to help maximize convenience for patients and were separate from the anesthesia preoperative evaluation. Patients attended class only once. High-risk patients (patients with chronic opioid therapy, recent history of or current SUDs, significant comorbid mental health issues) were encouraged to attend this class one-on-one with the TPS psychologist rather than in the group setting, so individual attention to mental health and SUD issues could be addressed directly.

Baseline history, morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and patient-reported outcomes using measures from the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS) for pain intensity (PROMIS 3a), pain interference (PROMIS 6b), and physical function (PROMIS 8b), and a pain-catastrophizing scale (PCS) score were obtained on all patients.18 PROMIS measures are validated questionnaires developed with the National Institutes of Health to standardize and quantify patient-reported outcomes in many domains.19 Patients with a history of SUD or COU met with the anesthesiologist and/or NP, and a personalized pain plan was developed that included preoperative opioid taper, buprenorphine use strategy, or opioid-free strategies.

Hospital Procedures

On the day of surgery, the TPS team met with the patient preoperatively and implemented an individualized pain plan that included multimodal analgesic techniques with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, and regional anesthesia, where appropriate (Table 2). Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols were developed in conjunction with the surgeons to include local infiltration analgesia by the surgeon, postoperative multimodal analgesic strategies, and intensive physical therapy starting the day of surgery for inpatient procedures.

After surgery, the TPS team followed up with patients daily and provided recommendations for analgesic therapies. Patients were offered daily sessions with the psychologist to reinforce and practice nonpharmacologic pain-coping strategies, such as meditation and relaxation. Prior to patient discharge, the TPS team provided recommendations for discharge medications and an opioid taper plan. For some patients taking buprenorphine before surgery who had stopped this therapy prior to or during their hospital stay, TPS providers transitioned them back to buprenorphine before discharge.

Postoperative Procedures

Patients were called by the nurse care coordinators at postdischarge days 2, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, and then monthly for ≥ 6 months. For patients who had not stopped opioid use or returned to their preoperative baseline opioid dose, weekly calls were made until opioid taper goals were achieved. At each call, nurses collected PROMIS scores for the previous 24 hours, the most recent 24-hour MEDD, the date of last opioid use, and the number of remaining opioid tablets after opioid cessation. In addition, nurses provided active listening and supportive care and encouragement as well as care coordination for issues related to rehabilitation facilities, physical therapy, transportation, medication questions, and wound questions. Nurses notified the anesthesiologist or NP when patients were unable to taper opioid use or had poor pain control as indicated by their PROMIS scores, opioid use, or directly expressed by the patient.

The TPS team prescribed alternative analgesic therapies, opioid taper plans, and communicated with surgeons and primary care providers if limited continued opioid therapy was recommended. Individual sessions with the psychologist were available to patients after discharge with a focus on ACT-matrix therapy and consultation with long-term mental health and/or substance abuse providers as indicated. Frequent communication and care coordination were maintained with the surgical team, the PCP, and other providers on the mental health or chronic pain services. This care coordination often included postsurgical joint clinic appointments in which TPS providers and nurses would be present with the surgeon or the PCP.

For patients with inadequately treated chronic pain conditions or who required long-term opioid tapers, we developed a combined clinic with the TPS and Anesthesia Chronic Pain group. This clinic allows patients to be seen by both services in the same setting, allowing a warm handoff by TPS to the chronic pain team.

Heath and Decision Support Tools

An electronic dashboard registry of surgical episodes managed by TPS was developed to achieve clinical, administrative, and quality improvement goals. The dashboard registry consists of surgical episode data, opioid doses, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical decision-making processes. Custom-built note templates capture pertinent data through embedded data labels, called health factors. Data are captured as part of routine clinical care, recorded in Computerized Patient Record System as health factors. They are available in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse as structured data. Workflows are executed daily to keep the dashboard registry current, clean, and able to process new data. Information displays direct daily clinical workflow and support point-of-care clinical decision making (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Data are aggregated across patient-care encounters and allow nurse care coordinators to concisely review pertinent patient data prior to delivering care. These data include surgical history, comorbidities, timeline of opioid use, and PROMIS scores during their course of recovery. This system allows TPS to optimize care delivery by providing longitudinal data across the surgical episode, thereby reducing the time needed to review records. Secondary purposes of captured data include measuring clinic performance and quality improvement to improve care delivery.

Results

The TPS intervention was implemented January 1, 2018. Two-hundred thirteen patients were enrolled between January and December 2018, which included 60 (28%) patients with a history of chronic opioid use and 153 (72%) patients who were considered opioid naïve. A total of 99% of patients had ≥ 1 successful follow-up within 14 days after discharge, 96% had ≥ 1 follow-up between 14 and 30 days after surgery, and 72% had completed personal follow-up 90 days after discharge (Table 3). For patients who TPS was unable to contact in person or by phone, 90-day MEDD was obtained using prescription and Controlled Substance Database reviews. The protocol for this retrospective analysis was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and the VA Research Review Committee.

By 90 days after surgery, 26 (43.3%) COUs were off opioids completely, 17 (28.3%) had decreased their opioid dose from their preoperative baseline MEDD (120 [SD, 108] vs 55 [SD, 45]), 14 (23.3%) returned to their baseline dose, and 3 (5%) increased from their baseline dose. Of the 153 patients who were NOUs before surgery, only 1 (0.7%) was taking opioids after 90 days. TPS continued to work closely with the patient and their PCP and that patient was finally able to stop opioid use 262 days after discharge. Ten patients had an additional surgery within 90 days of the initial surgery. Of these, 6 were COU, of whom 3 stopped all opioids by 90 days from their original surgery, 2 had no change in MEDD at 90 days, and 1 had a lower MEDD at 90 days. Of the 4 NOU who had additional surgery, all were off opioids by 90 days from the original surgery.

Although difficult to quantify, a meaningful outcome of TPS has been to improve satisfaction substantially among health care providers caring for complex patients at risk for chronic opioid abuse. This group includes the many members of the surgical team, PCPs, and addiction specialists who appreciate the close care coordination and assistance in caring for patients with difficult issues, especially with opioid tapers or SUDs. We also have noticed changes in prescribing practices among surgeons and PCPs for their patients who are not part of TPS.

Discussion

With any new clinical service, there are obstacles and challenges. TPS requires a considerable investment in personnel, and currently no mechanism is in place for obtaining payment for many of the provided services. We were fortunate the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Office of Rural Health, and the VA Centers of Innovation provided support for the development, implementation, and pilot evaluation of TPS. After we presented our initial results to hospital leadership, we also received hospital support to expand TPS service to include a total of 4 nurse care coordinators and 2 psychologists. We are currently performing a cost analysis of the service but recognize that this model may be difficult to reproduce at other institutions without a change in reimbursement standards.

Developing a working relationship with the surgical and primary care services required a concerted effort from the TPS team and a number of months to become effective. As most veterans receive primary care, mental health care, and surgical care within the VA system, this model lends itself to close care coordination. Initially there was skepticism about TPS recommendations to reduce opioid use, especially from PCPs who had cared for complex patients over many years. But this uncertainty went away as we showed evidence of close patient follow-up and detailed communication. TPS soon became the designated service for both primary care and surgical providers who were otherwise uncomfortable with how to approach opioid tapers and nonopioid pain strategies. In fact, a substantial portion of our referrals now come directly from the PCP who is referring a high-risk patient for evaluation for surgery rather than from the surgeons, and joint visits with TPS and primary care have become commonplace.

Challenges abound when working with patients with substance abuse history, opioid use history, high anxiety, significant pain catastrophizing, and those who have had previous negative experiences with surgery. We have found that the most important facet of our service comes from the amount of time and effort team members, especially the nurses, spend helping patients. Much of the nurses' work focuses on nonpain-related issues, such as assisting patients with finding transportation, housing issues, questions about medications, help scheduling appointments, etc. Through this concerted effort, patients gain trust in TPS providers and are willing to listen to and experiment with our recommendations. Many patients who were initially extremely unreceptive to the presurgery education asked for our support weeks after surgery to help with postsurgery pain.

Another challenge we continue to experience comes from the success of the program.

Conclusions

The multidisciplinary TPS supports greater preoperative to postoperative longitudinal care for surgical patients. This endeavor has resulted in better patient preparation before surgery and improved care coordination after surgery, with specific improvements in appropriate use of opioid medications and smooth transitions of care for patients with ongoing and complex needs. Development of sophisticated note templates and customized health information technology allows for accurate follow-through and data gathering for quality improvement, facilitating data-driven improvements and proving value to the facility.

Given that TPS is a multidisciplinary program with multiple interventions, it is difficult to pinpoint which specific aspects of TPS are most effective in achieving success. For example, although we have little doubt that the work our psychologists do with our patients is beneficial and even essential for the success we have had with some of our most difficult patients, it is less clear whether it matters if they use mindfulness, ACT matrix, or cognitive behavioral therapy. We think that an important part of TPS is the frequent human interaction with a caring individual. Therefore, as TPS continues to grow, maintaining the ability to provide frequent personal interaction is a priority.

The role of opioids in acute pain deserves further scrutiny. In 2018, with TPS use of opioids after orthopedic surgery decreased by > 40% from the previous year. Despite this more restricted use of opioids, pain interference and physical function scores indicated that surgical patients do not seem to experience increased pain or reduced physical function. In addition, stopping opioid use for COUs did not seem to affect the quality of recovery, pain, or physical function. Future prospective controlled studies of TPS are needed to confirm these findings and identify which aspects of TPS are most effective in improving functional recovery of patients. Also, more evidence is needed to determine the appropriateness or need for opioids in acute postsurgical pain.

TPS has expanded to include all surgical specialties. Given the high burden and limited resources, we have chosen to focus on patients at higher risk for chronic postsurgical pain by type of surgery (eg, thoracotomy, open abdominal, limb amputation, major joint surgery) and/or history of substance abuse or chronic opioid use. To better direct scarce resources where it would be of most benefit, we are now enrolling only NOUs without other risk factors postoperatively if they request a refill of opioids or are otherwise struggling with pain control after surgery. Whether this approach affects the success we had in the first year in preventing new COUs after surgery remains to be seen.

It is unlikely that any single model of a perioperative surgical home will fit the needs of the many different types of medical systems that exist. The TPS model fits well in large hospital systems, like the VA, where patients receive most of their care within the same system. However, it seems to us that the optimal TPS program in any health system will provide education, support, and care coordination beginning preoperatively to prepare the patient for surgery and then to facilitate care coordination to transition patients back to their PCPs or on to specialized chronic care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Candice Harmon, RN; David Merrill, RN; Amy Beckstead, RN, who have provided invaluable assistance with establishing the TPS program at the VA Salt Lake City and helping with the evaluation process.

Funding for the implementation and evaluation of the TPS was received from the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Center of Innovation, the VA Office of Rural Health, and National Institutes of Health Grant UL1TR002538.

1. Ilfeld BM, Madison SJ, Suresh PJ. Persistent postmastectomy pain and pain-related physical and emotional functioning with and without a continuous paravertebral nerve block: a prospective 1-year follow-up assessment of a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):2017-2025. doi:10.1245/s10434-014-4248-7

2. Richebé P, Capdevila X, Rivat C. Persistent postsurgical pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(3):590-607. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000002238

3. Glare P, Aubrey KR, Myles PS. Transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1537-1546. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30352-6

4. Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surgery. 2017;152(6):e170504-e170504. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504

5. Swenson CW, Kamdar NS, Seiler K, Morgan DM, Lin P, As-Sanie S. Definition development and prevalence of new persistent opioid use following hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(5):486.e1-486.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.010

6. Bartels K, Fernandez-Bustamante A, McWilliams SK, Hopfer CJ, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK. Long-term opioid use after inpatient surgery - a retrospective cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:61-65. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.013

7. Bedard N, DeMik D, Dowdle S, Callaghan J. Trends and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(1)(suppl A):62-67. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.100b1.bjj-2017-0547.r1

8. Politzer CS, Kildow BJ, Goltz DE, Green CL, Bolognesi MP, Seyler T. Trends in opioid utilization before and after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7S):S147-S153.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.060

9. Mariano ER, Walters TL, Kim ET, Kain ZN. Why the perioperative surgical home makes sense for Veterans Affairs health care. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(5):1163-1166. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000000712

10. Walters TL, Howard SK, Kou A, et al. Design and implementation of a perioperative surgical home at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;20(2):133-140. doi:10.1177/1089253215607066

11. Walters TL, Mariano ER, Clark DJ. Perioperative surgical home and the integral role of pain medicine. Pain Med. 2015;16(9):1666-1672. doi:10.1111/pme.12796

12. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of the perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000002280

13. Shafer SL. Anesthesia & Analgesia’s 2015 collection on the perioperative surgical home. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(5):966-967. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000000696

14. Wenzel JT, Schwenk ES, Baratta JL, Viscusi ER. Managing opioid-tolerant patients in the perioperative surgical home. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):287-301. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.005

15. Katz J, Weinrib A, Fashler SR, et al. The Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent chronic postsurgical pain. J Pain Res. 2015;8:695-702. doi:10.2147/jpr.s91924

16. Tiippana E, Hamunen K, Heiskanen T, Nieminen T, Kalso E, Kontinen VK. New approach for treatment of prolonged postoperative pain: APS Out-Patient Clinic. Scand J Pain. 2016;12(1):19-24. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.02.008

17. Katz J, Weinrib AZ, Clarke H. Chronic postsurgical pain: from risk factor identification to multidisciplinary management at the Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service. Can J Pain. 2019;3(2):49-58. doi:10.1080/24740527.2019.1574537

18. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524-532. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524

19. HealthMeasures. Intro to PROMIS. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis. Accessed September 28, 2020.

1. Ilfeld BM, Madison SJ, Suresh PJ. Persistent postmastectomy pain and pain-related physical and emotional functioning with and without a continuous paravertebral nerve block: a prospective 1-year follow-up assessment of a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):2017-2025. doi:10.1245/s10434-014-4248-7

2. Richebé P, Capdevila X, Rivat C. Persistent postsurgical pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(3):590-607. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000002238

3. Glare P, Aubrey KR, Myles PS. Transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1537-1546. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30352-6

4. Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surgery. 2017;152(6):e170504-e170504. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504

5. Swenson CW, Kamdar NS, Seiler K, Morgan DM, Lin P, As-Sanie S. Definition development and prevalence of new persistent opioid use following hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(5):486.e1-486.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.010

6. Bartels K, Fernandez-Bustamante A, McWilliams SK, Hopfer CJ, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK. Long-term opioid use after inpatient surgery - a retrospective cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:61-65. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.013

7. Bedard N, DeMik D, Dowdle S, Callaghan J. Trends and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(1)(suppl A):62-67. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.100b1.bjj-2017-0547.r1

8. Politzer CS, Kildow BJ, Goltz DE, Green CL, Bolognesi MP, Seyler T. Trends in opioid utilization before and after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7S):S147-S153.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.060

9. Mariano ER, Walters TL, Kim ET, Kain ZN. Why the perioperative surgical home makes sense for Veterans Affairs health care. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(5):1163-1166. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000000712

10. Walters TL, Howard SK, Kou A, et al. Design and implementation of a perioperative surgical home at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;20(2):133-140. doi:10.1177/1089253215607066

11. Walters TL, Mariano ER, Clark DJ. Perioperative surgical home and the integral role of pain medicine. Pain Med. 2015;16(9):1666-1672. doi:10.1111/pme.12796

12. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of the perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000002280

13. Shafer SL. Anesthesia & Analgesia’s 2015 collection on the perioperative surgical home. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(5):966-967. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000000696

14. Wenzel JT, Schwenk ES, Baratta JL, Viscusi ER. Managing opioid-tolerant patients in the perioperative surgical home. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):287-301. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.005

15. Katz J, Weinrib A, Fashler SR, et al. The Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent chronic postsurgical pain. J Pain Res. 2015;8:695-702. doi:10.2147/jpr.s91924

16. Tiippana E, Hamunen K, Heiskanen T, Nieminen T, Kalso E, Kontinen VK. New approach for treatment of prolonged postoperative pain: APS Out-Patient Clinic. Scand J Pain. 2016;12(1):19-24. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.02.008

17. Katz J, Weinrib AZ, Clarke H. Chronic postsurgical pain: from risk factor identification to multidisciplinary management at the Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service. Can J Pain. 2019;3(2):49-58. doi:10.1080/24740527.2019.1574537

18. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524-532. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524

19. HealthMeasures. Intro to PROMIS. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis. Accessed September 28, 2020.