User login

It is unfortunate that, in some clinical areas, medical conditions are still treated by name and not based on the underlying pathological process. It would be odd in 2022 to treat “dropsy” instead of heart or kidney disease (2 very different causes of edema). Similarly, if the FDA had been approving drugs 150 years ago, we would have medications on label for “dementia praecox,” not schizophrenia or Alzheimer disease. With the help of DSM-5, psychiatry still resides in the descriptive symptomatic world of disorders.

In the United States, thanks to Freud, psychiatric symptoms became separated from medical symptoms, which made it more difficult to associate psychiatric manifestations with the underlying pathophysiology. Though the physical manifestations that parallel emotional symptoms—such as the dry mouth of anxiety, the tremor and leg weakness of fear, the constipation and blurry vision of depression, the breathing difficulty of anger, the abdominal pain of stress, the blushing of shyness, the palpitations of flashbacks, and endless others—are well known, the present classification of psychiatric disorders is blind to it. Neurochemical causes of gastrointestinal spasm or muscle tension are better researched than underlying central neurochemistry, though the same neurotransmitters drive them.

Can the biochemistry of psychiatric symptoms be judged on the basis of peripheral symptoms? Can the mental manifestations be connected to biological causation, and vice versa? Would psychiatrists be better off selecting treatments by recognizing involved neurotransmitters instead of addressing descriptive “depression, anxiety, and psychosis”? Each of these clinical syndromes may be caused by entirely different underlying neuronal mechanisms. Such mechanisms could be suggested if medical symptoms (which are measurable and objective) would become part of the psychiatric diagnosis. Is treating the “cough” sufficient, or would recognition that tuberculosis caused the cough guide better treatment? Is it time to abandon descriptive conditions and replace them with a specific “mechanism-based” viewpoint?

Ample research has shown that serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, endorphins, glutamate, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) are the neurotransmitters most responsible in the process of both psychiatric disorders and chronic pain. These neurotransmitters are involved in much more than emotions (including the feeling of pain). An abundance of medical symptom clusters point toward which neurotransmitter dysfunction may be leading in specific cases of distinct types of depression, psychosis, anxiety, or “chronic pain.” Even presently, there are medications available (both for FDA-approved indications and off-label) that can be used to regulate these neurotransmitters, allowing practitioners to target the possible biological underlining of psychiatric or pain pathology. Hopefully, in the not-so-distant future, there will be specific medications for serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenergic depression as well as for GABAergic anxiety, endorphin psychosis, noradrenergic insomnia, and similar conditions.

Numerous neurotransmitters may be connected to both depression and pain in all their forms. These include (but are not limited to) prostaglandins, bradykinins, substance P, potassium, magnesium, calcium, histamine, adenosine triphosphate, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), nitric oxide (NO), cholecystokinin 7 (CCK7), neurotrophic growth factor (NGF), neurotensin, acetylcholine (Ach), oxytocin, cannabinoids, and others. These have not been researched sufficiently to identify their clinical presentation of excessive or insufficient availability at the sites of neurotransmission. It is difficult to draw conclusions about what kind of clinical symptoms they may cause (outside of pain), and therefore, they are not addressed in this article.

Both high and low levels of certain neurotransmitters may be associated with psychiatric conditions and chronic pain. Too much is as bad as too little.1 This applies to both quantity of neurotransmitters as well as quality of the corresponding receptor activity. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation. Reading indirect signs of bodily functions is a basic clinical skill that should not be forgotten, even in the time of advanced technology.

A different way of viewing psychiatric disorders

In this article, we present 4 hypothetical clinical cases to emphasize a possible way of analyzing symptoms to identify underlying pathology and guide more effective treatment. In no way do these descriptions reflect the entire set of symptoms caused by neurotransmitters; we created them based on what is presently known or suspected, and extensive research is required to confirm or disprove what we describe here.

Continue to: There are no well-recognized...

There are no well-recognized, well-established, reliable, or validated syndromes described in our work. Our goal is to suggest an alternative way of looking at psychiatric disorders by viewing syndromal presentation through the lens of specific neurotransmitters. The collection of symptoms associated with various neurotransmitters as presented in this hypothesis is not complete. We have assembled what is described in the literature as a suggestion for specific future research. We simplified these clinical presentations by omitting scenarios in which a specific neurotransmitter increases in one area but not another. For example, all the symptoms of dopamine excess we describe would not have to occur concurrently in the same patient, but they may develop in certain patients depending on which dopaminergic pathway is exhibiting excess activity. Such distinctions may be established only by exhaustive research not yet conducted.

Our proposal may seem radical, but it truly is not. For example, if we know that dopamine excess may cause seizures, psychosis, and blood pressure elevation, why not consider dopamine excess as an underlying cause in a patient with depression who exhibits these symptoms simultaneously? And why not call it “dopamine excess syndrome”? We already have “serotonin syndrome” for a patient experiencing a serotonin storm. However, using the same logic, it should be called “serotonin excess syndrome.” And if we know of “serotonin excess syndrome,” why not consider “serotonin deficiency syndrome”?

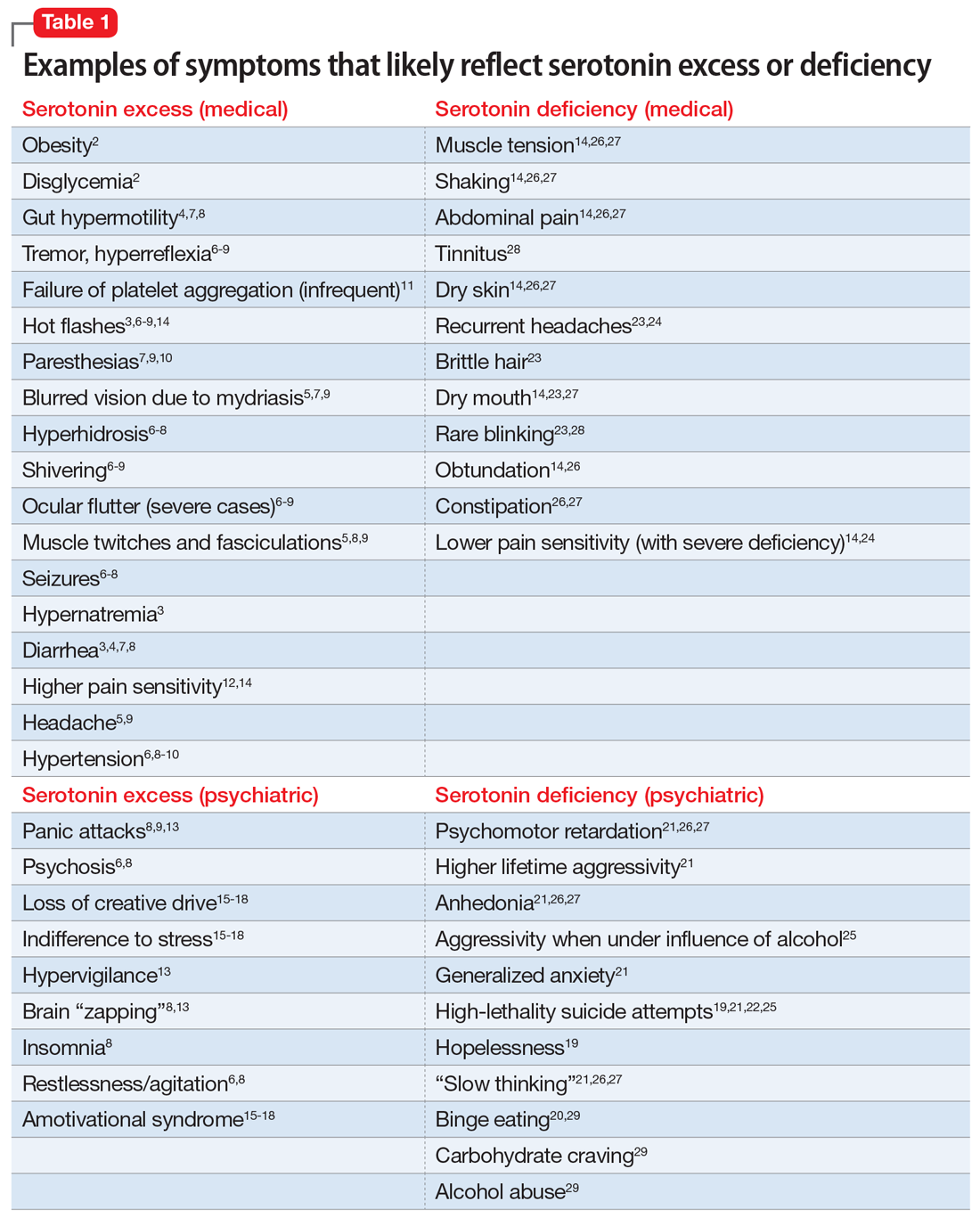

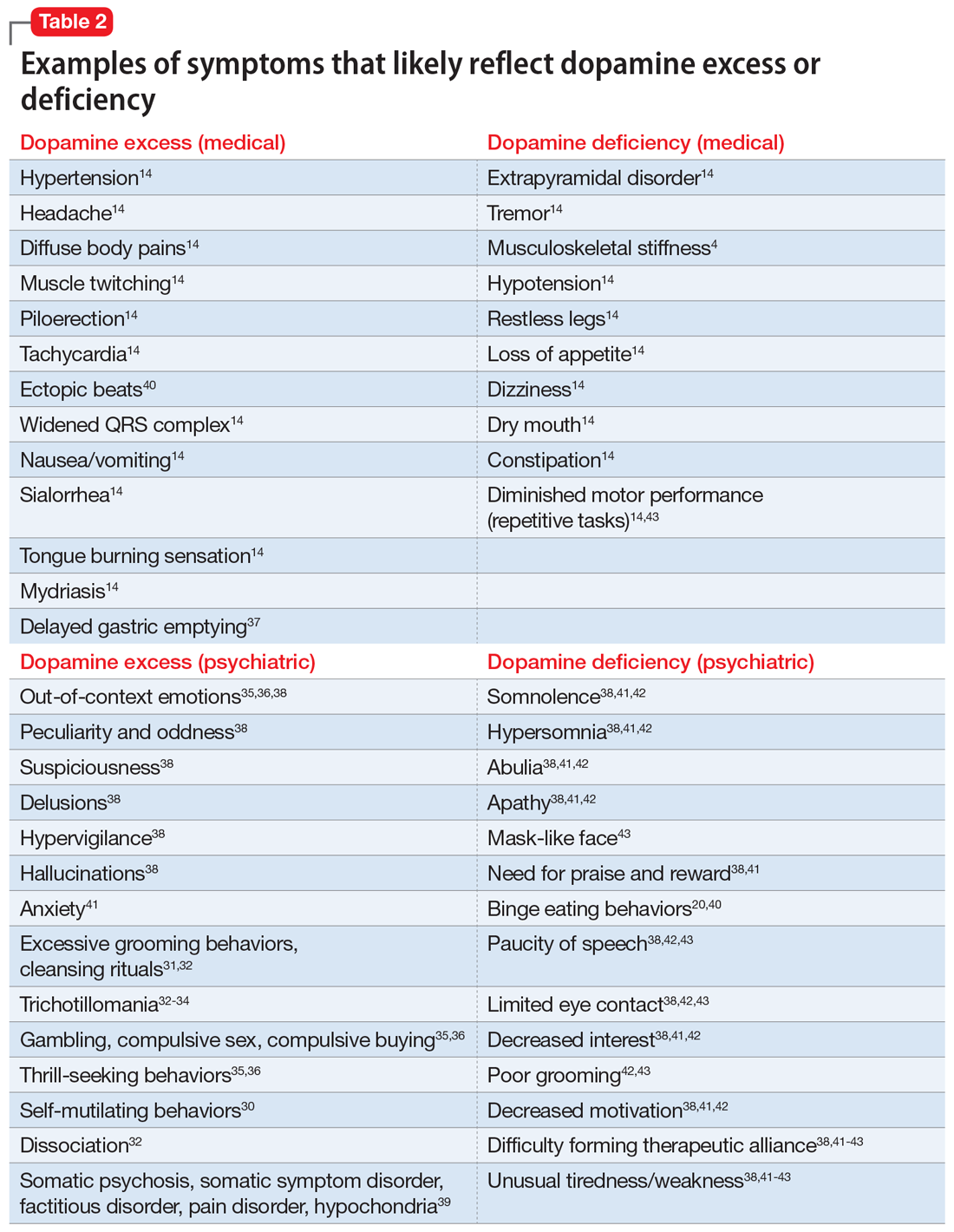

In Part 1 of this article, we discuss serotonin and dopamine. Table 1 outlines medical and psychiatric symptoms that likely reflect serotonin excess2-18 and deficiency,14,19-29 and Table 2 lists symptoms that likely reflect dopamine excess14,30-41 and deficiency.4,14,20,38,40-43 In Part 2 we will touch on endorphins and norepinephrine, and in Part 3 we will conclude by looking at GABA and glutamate.

Serotonin excess (Table 12-18)

On a recent office visit, Ms. H reports that most of the time she does not feel much of anything, but she still experiences panic attacks8,9,13,15 and is easily agitated.6,8 Her mother died recently, and Ms. H is concerned that she did not grieve.15-18 She failed her last semester in college and was indifferent to her failure.18 She sleeps poorly,8 is failing her creative classes, and wonders why she has lost her artistic inclination.16-18 Ms. H has difficulty with amotivation, planning, social interactions, and speech.16,17 All of those symptoms worsened after she was prescribed fluoxetine approximately 1 year ago for her “blues.” Ms. H is obese and continues to gain weight,2 though she frequently has diarrhea,3,4,7,8 loud peristalsis, and abdominal cramps.4,7,8 She sweats easily6-8 and her heart frequently races.8,9 Additionally, Ms. H’s primary care physician told her that she has “borderline diabetes.”2 She is prone to frequent bruising11 and is easy to shake, even when she is experiencing minimal anxiety.6-9 Ms. H had consulted with a neurologist because of unusual electrical “zapping” in her brain and muscle twitches.5,8,9,13 She had experienced a seizure as a child, but this was possibly related to hypernatremia,2 and she has not taken any anticonvulsant medication for several years.8 She exhibits hyperactive deep tendon reflexes and tremors5,7,9 and blinks frequently.6,9 She experiences hot flashes,3,6-8,14 does not tolerate heat, and prefers cooler weather.8,9 Her pains and aches,12,14 to which she has been prone all of her life, have recently become much worse, and she was diagnosed with fibromyalgia in part because she frequently feels stiff all over.10 She complains of strange tingling and prickling sensations in her hands and feet, especially when anxious.7,9,10 Her headaches also worsened and may be precipitated by bright light, as her pupils are usually dilated.5,7,9 Her hypertension is fairly controlled with medication.6,8-10 Ms. H says she experienced a psychotic episode when she was in her mid-teens,6,8 but reassures you that “she is not that bad now,” although she remains hypervigilant.13 Also while in her teens, Ms. H was treated with paroxetine and experienced restlessness, agitation, delirium, tachycardia, fluctuating blood pressure, diaphoresis, diarrhea, and neuromuscular excitation, which prompted discontinuation of the antidepressant.5-7,9,10

Impression. Ms. H exhibits symptoms associated with serotonin hyperactivity. Discontinuing and avoiding selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) would be prudent; prescribing an anticonvulsant would be reasonable. Using a GABAergic medication to suppress serotonin (eg, baclofen) is likely to help. Avoiding dopaminergic medications is a must. Antidepressive antipsychotics would be logical to use. The use of serotonin-suppressing medications may be considered. One may argue for the use of beta-blockers in such a patient.

Continue to: Serotonin deficiency

Serotonin deficiency (Table 114,19-29)

Mr. A is chronically depressed, hopeless,19 and easily angered.21 He does not believe anyone can help him.19 You are concerned for his safety because he had attempted to end his life by shooting himself in the chest.19,21,22,25 Even when he’s not particularly depressed, Mr. A does not enjoy much of anything.21,26,27 He becomes particularly agitated when he drinks alcohol,25 which unfortunately is common for him.29 He engages in binge eating to feel better; he knows this is not healthy but he cannot control his behavior.20,29 Mr. A is poorly compliant with his medications, even with a blood thinner, which he was prescribed due to an episode of deep vein thrombosis. He complains of chronic daily headaches and episodic migraines.23,24 He rarely blinks,23,28 his skin is dry and cool, his hair is brittle,23 his mouth is dry,14,23,27 and he constantly licks his chapped lips.14,26,27 Mr. A frequently has general body pain26,31 but is dismissive of his body aches and completely stops reporting pain when his depression gets particularly severe. When depressed, he is slow in movement and thinking.14,21,26,27 He is more concerned with anxiety than depression.21 Mr. A is plagued by constipation, abdominal pain, muscle tension, and episodes of shaking.14,26,27 He also frequently complains about chronic tinnitus.28

Impression. Mr. A shows symptoms associated with serotonin hypoactivity. SSRIs and any other antidepressants with serotonin activity would be an obvious choice for treatment. A mood-stabilizing antipsychotic with serotonin activity would be welcome in treatment. Thyroid hormone supplementation may be of value, especially if thyroid stimulating hormone level is high. Light therapy, a diet with food that contains tryptophan, psychotherapy, and exercise are desirable. Avoiding benzodiazepines would be a good idea.

Dopamine excess (Table 214,30-41)

Ms. L presents with complaints of “fibromyalgia” and “daily headaches,”14 and also dissociation (finding herself in places when she does not know how she got there) and “out-of-body experiences.”32 She is odd, and states that people do not understand her and that she is “different.”38 Her friend, who is present at the appointment, elaborates on Ms. L’s bizarreness and oddness in behavior, out-of-context emotions, suspiciousness, paranoia, and possible hallucinations.35,36,38 Ms. L discloses frequent diffuse body pains, headaches, nausea, excessive salivation, and tongue burning, as well as muscle twitching.14 Sex worsens her headaches and body pain. She reports seizures that are not registered on EEG. In the office, she is suspicious, exhibits odd posturing, tends to misinterpret your words, and makes you feel uncomfortable. Anxiety38 and multiple obsessive-compulsive symptoms, especially excessive cleaning and grooming, complicate Ms. L’s life.31,32,34 On examination, she is hypertensive, and she has scars caused by self-cutting and skin picking on her arms.30-32 An electrocardiogram shows an elevated heart rate, widened QRS complex, and ectopic heartbeats.14 Ms. L has experienced trichotillomania since adolescence32-34 and her fingernails are bitten to the skin.34 She has difficulty with impulse control, and thrill-seeking is a prominent part of her life, mainly via gambling, compulsive sex, and compulsive buying.35,36 She also says she experiences indigestion and delayed gastric emptying.37

Impression. Ms. L exhibits multiple symptoms associated with dopamine excess. Dopamine antagonists should be considered and may help not only with her psychiatric symptoms but also with her pain symptoms. Bupropion (as a dopamine agonist), caffeine, and stimulants should be avoided.

Excessive dopamine is, in extreme cases, associated with somatic psychosis, somatic symptom disorder, factitious disorder, pain disorder, and hypochondria.39 It may come with odd and bizarre/peculiar symptoms out of proportion with objectively identified pathology. These symptoms are common in chronic pain and headache patients, and need to be addressed by appropriate use of dopamine antagonizing medications.39

Continue to: Dopamine deficiency

Dopamine deficiency (Table 24,14,20,38,40-43)

Mr. W experiences widespread pain, including chronic back pain, headaches, and abdominal pain. He also has substantial anhedonia, lack of interest, procrastination, and hypersomnia.41,42 He is apathetic and has difficulty getting up in the morning.41,42 Unusual tiredness and weakness drive him to overuse caffeine; he states that 5 Mountain Dews and 4 cups of regular coffee a day make his headaches bearable.38,41-43 Sex also improves his headaches. Since childhood, he has taken stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. He reports that occasional use of cocaine helps ease his pain and depression. Mr. W’s wife is concerned with her husband’s low sexual drive and alcohol consumption, and discloses that he has periodic trouble with gambling. Mr. W was forced into psychotherapy but never was able to work productively with his therapist.38,41-43 He loves eating and cannot control his weight.40 This contrasts with episodic anorexia he experienced when he was younger.20 His face is usually emotionless.43 Mr. W is prone to constipation.14 His restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are so bad that his wife refuses to share a bed with him.14 He is clumsy and has a problem with repetitive motor tasks.43 A paucity of speech, limited eye contact, poor grooming, and difficulty forming therapeutic alliances have long been part of Mr. W’s history.38,42,43 On physical examination, he has a dry mouth; he is stiff, tremulous, and hypotensive.14

Impression. Mr. W shows multiple symptoms associated with dopamine deficiency. Bupropion may be reasonable to consider. Dopamine augmentation via the use of stimulants is warranted in such patients, especially if stimulants had not been tried before (lisdexamfetamine would be a good choice to minimize addictive potential). For a patient with dopamine deficiency, levodopa may improve more than just restless legs. Amantadine may improve dopaminergic signaling through the accelerated dopamine release and decrease in presynaptic uptake, so this medication may be carefully tried.44 Pain treatment would not be successful for Mr. W without simultaneous treatment for his substance use.

Bottom Line

Both high and low levels of serotonin and dopamine may be associated with certain psychiatric and medical symptoms and disorders. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation, and tailor treatment accordingly.

Related Resources

- Abell SR, El-Mallakh RS. Serotonin-mediated anxiety: How to recognize and treat it. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):37-40. doi:10.12788/cp.0168

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Stahl SM. Dazzled by the dominions of dopamine: clinical roles of D3, D2, and D1 receptors. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(4):305-311.

2. Young RL, Lumsden AL, Martin AM, et al. Augmented capacity for peripheral serotonin release in human obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(11):1880-1889.

3. Ahlman H. Serotonin and carcinoid tumors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7(Suppl 7):S79-S85.

4. Terry N, Margolis KG. Serotonergic mechanisms regulating the GI tract: experimental evidence and therapeutic relevance. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;239:319-342.

5. Prakash S, Belani P, Trivedi A. Headache as a presenting feature in patients with serotonin syndrome: a case series. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(2):148-153.

6. van Ewijk CE, Jacobs GE, Girbes ARJ. Unsuspected serotonin toxicity in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):85.

7. Pedavally S, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Serotonin syndrome in the intensive care unit: clinical presentations and precipitating medications. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(1):108-113.

8. Nguyen H, Pan A, Smollin C, et al. An 11-year retrospective review of cyproheptadine use in serotonin syndrome cases reported to the California Poison Control System. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(2):327-334.

9. Ansari H, Kouti L. Drug interaction and serotonin toxicity with opioid use: another reason to avoid opioids in headache and migraine treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(8):50.

10. Ott M, Mannchen JK, Jamshidi F, et al. Management of severe arterial hypertension associated with serotonin syndrome: a case report analysis based on systematic review techniques. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2019;9:2045125318818814. doi:10.1177/2045125318818814

11. Cerrito F, Lazzaro MP, Gaudio E, et al. 5HT2-receptors and serotonin release: their role in human platelet aggregation. Life Sci. 1993;53(3):209-215.

12. Ohayon MM. Pain sensitivity, depression, and sleep deprivation: links with serotoninergic dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(16):1243-1245.

13. Maron E, Shlik J. Serotonin function in panic disorder: important, but why? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(1):1-11.

14. Hall JE, Guyton AC. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 12th ed. Spanish version. Elsevier; 2011:120,199,201-204,730-740.

15. Garland EJ, Baerg EA. Amotivational syndrome associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(2):181-186.

16. George MS, Trimble MR. A fluvoxamine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in a patient with comorbid Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(10):379-380.

17. Hoehn-Saric R, Harris GJ, Pearlson GD, et al. A fluoxetine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in an obsessive compulsive patient. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(3):131-133.

18. Hoehn-Saric R, Lipsey JR, McLeod DR. Apathy and indifference in patients on fluvoxamine and fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(5):343-345.

19. Samuelsson M, Jokinen J, Nordström AL, et al. CSF 5-HIAA, suicide intent and hopelessness in the prediction of early suicide in male high-risk suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):44-47.

20. Brewerton TD. Clinical Handbook of Eating Disorders: An Integrated Approach. CRC Press; 2004:257-281.

21. Mann JJ, Oquendo M, Underwood MD, et al. The neurobiology of suicide risk: a review for the clinician. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 2:7-116.

22. Mann JJ, Malone KM. Cerebrospinal fluid amines and higher-lethality suicide attempts in depressed inpatients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(2):162-171.

23. Joseph R, Welch KM, D’Andrea G. Serotonergic hypofunction in migraine: a synthesis of evidence based on platelet dense body dysfunction. Cephalalgia. 1989;9(4):293-299.

24. Pakalnis A, Splaingard M, Splaingard D, et al. Serotonin effects on sleep and emotional disorders in adolescent migraine. Headache. 2009;49(10):1486-1492.

25. Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Nielsen DA, et al. Low brain serotonin turnover rate (low CSF 5-HIAA) and impulsive violence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1995;20(4):271-275.

26. Liu Y, Zhao J, Fan X, et al. Dysfunction in serotonergic and noradrenergic systems and somatic symptoms in psychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:286.

27. Ginsburg GS, Riddle MA, Davies M. Somatic symptoms in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(10):1179-1187.

28. O’Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, et al. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(12):980-990.

29. Fortuna JL. Sweet preference, sugar addiction and the familial history of alcohol dependence: shared neural pathways and genes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(2):147-151.

30. Stanley B, Sher L, Wilson S, et al. Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, endogenous opioids and monoamine neurotransmitters. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(1-2):134-140.

31. Graybiel AM, Saka E. A genetic basis for obsessive grooming. Neuron. 2002;33(1):1-2.

32. Tse W, Hälbig TD. Skin picking in Parkinson’s disease: a behavioral side-effect of dopaminergic treatment? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(2):214.

33. Ayaydın H. Probable emergence of symptoms of trichotillomania by atomoxetine: a case report. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2019;29(2)220-222.

34. Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:9782702. doi:10.1155/2016/9782702

35. Clark CA, Dagher A. The role of dopamine in risk taking: a specific look at Parkinson’s disease and gambling. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:196.

36. Norbury A, Husain M. Sensation-seeking: dopaminergic modulation and risk for psychopathology. Behav Brain Res. 2015;288:79-93.

37. Chen TS, Chang FY. Elevated serum dopamine increases while coffee consumption decreases the occurrence of reddish streaks in the intact stomach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(12):1810-1814.

38. Wong-Riley MT. Neuroscience Secrets. 1st edition. Spanish version. Hanley & Belfus; 1999:420-429.

39. Arbuck DM. Antipsychotics, dopamine, and pain. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):25-29,31.

40. Bello NT, Hajnal A. Dopamine and binge eating behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97(1):25-33.

41. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70 Suppl 4:1-46.

42. Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, et al. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):495-506.

43. Gepshtein S, Li X, Snider J, et al. Dopamine function and the efficiency of human movement. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(3):645-657.

44. Scarff JR. The ABCDs of treating tardive dyskinesia. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):21,55.

It is unfortunate that, in some clinical areas, medical conditions are still treated by name and not based on the underlying pathological process. It would be odd in 2022 to treat “dropsy” instead of heart or kidney disease (2 very different causes of edema). Similarly, if the FDA had been approving drugs 150 years ago, we would have medications on label for “dementia praecox,” not schizophrenia or Alzheimer disease. With the help of DSM-5, psychiatry still resides in the descriptive symptomatic world of disorders.

In the United States, thanks to Freud, psychiatric symptoms became separated from medical symptoms, which made it more difficult to associate psychiatric manifestations with the underlying pathophysiology. Though the physical manifestations that parallel emotional symptoms—such as the dry mouth of anxiety, the tremor and leg weakness of fear, the constipation and blurry vision of depression, the breathing difficulty of anger, the abdominal pain of stress, the blushing of shyness, the palpitations of flashbacks, and endless others—are well known, the present classification of psychiatric disorders is blind to it. Neurochemical causes of gastrointestinal spasm or muscle tension are better researched than underlying central neurochemistry, though the same neurotransmitters drive them.

Can the biochemistry of psychiatric symptoms be judged on the basis of peripheral symptoms? Can the mental manifestations be connected to biological causation, and vice versa? Would psychiatrists be better off selecting treatments by recognizing involved neurotransmitters instead of addressing descriptive “depression, anxiety, and psychosis”? Each of these clinical syndromes may be caused by entirely different underlying neuronal mechanisms. Such mechanisms could be suggested if medical symptoms (which are measurable and objective) would become part of the psychiatric diagnosis. Is treating the “cough” sufficient, or would recognition that tuberculosis caused the cough guide better treatment? Is it time to abandon descriptive conditions and replace them with a specific “mechanism-based” viewpoint?

Ample research has shown that serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, endorphins, glutamate, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) are the neurotransmitters most responsible in the process of both psychiatric disorders and chronic pain. These neurotransmitters are involved in much more than emotions (including the feeling of pain). An abundance of medical symptom clusters point toward which neurotransmitter dysfunction may be leading in specific cases of distinct types of depression, psychosis, anxiety, or “chronic pain.” Even presently, there are medications available (both for FDA-approved indications and off-label) that can be used to regulate these neurotransmitters, allowing practitioners to target the possible biological underlining of psychiatric or pain pathology. Hopefully, in the not-so-distant future, there will be specific medications for serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenergic depression as well as for GABAergic anxiety, endorphin psychosis, noradrenergic insomnia, and similar conditions.

Numerous neurotransmitters may be connected to both depression and pain in all their forms. These include (but are not limited to) prostaglandins, bradykinins, substance P, potassium, magnesium, calcium, histamine, adenosine triphosphate, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), nitric oxide (NO), cholecystokinin 7 (CCK7), neurotrophic growth factor (NGF), neurotensin, acetylcholine (Ach), oxytocin, cannabinoids, and others. These have not been researched sufficiently to identify their clinical presentation of excessive or insufficient availability at the sites of neurotransmission. It is difficult to draw conclusions about what kind of clinical symptoms they may cause (outside of pain), and therefore, they are not addressed in this article.

Both high and low levels of certain neurotransmitters may be associated with psychiatric conditions and chronic pain. Too much is as bad as too little.1 This applies to both quantity of neurotransmitters as well as quality of the corresponding receptor activity. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation. Reading indirect signs of bodily functions is a basic clinical skill that should not be forgotten, even in the time of advanced technology.

A different way of viewing psychiatric disorders

In this article, we present 4 hypothetical clinical cases to emphasize a possible way of analyzing symptoms to identify underlying pathology and guide more effective treatment. In no way do these descriptions reflect the entire set of symptoms caused by neurotransmitters; we created them based on what is presently known or suspected, and extensive research is required to confirm or disprove what we describe here.

Continue to: There are no well-recognized...

There are no well-recognized, well-established, reliable, or validated syndromes described in our work. Our goal is to suggest an alternative way of looking at psychiatric disorders by viewing syndromal presentation through the lens of specific neurotransmitters. The collection of symptoms associated with various neurotransmitters as presented in this hypothesis is not complete. We have assembled what is described in the literature as a suggestion for specific future research. We simplified these clinical presentations by omitting scenarios in which a specific neurotransmitter increases in one area but not another. For example, all the symptoms of dopamine excess we describe would not have to occur concurrently in the same patient, but they may develop in certain patients depending on which dopaminergic pathway is exhibiting excess activity. Such distinctions may be established only by exhaustive research not yet conducted.

Our proposal may seem radical, but it truly is not. For example, if we know that dopamine excess may cause seizures, psychosis, and blood pressure elevation, why not consider dopamine excess as an underlying cause in a patient with depression who exhibits these symptoms simultaneously? And why not call it “dopamine excess syndrome”? We already have “serotonin syndrome” for a patient experiencing a serotonin storm. However, using the same logic, it should be called “serotonin excess syndrome.” And if we know of “serotonin excess syndrome,” why not consider “serotonin deficiency syndrome”?

In Part 1 of this article, we discuss serotonin and dopamine. Table 1 outlines medical and psychiatric symptoms that likely reflect serotonin excess2-18 and deficiency,14,19-29 and Table 2 lists symptoms that likely reflect dopamine excess14,30-41 and deficiency.4,14,20,38,40-43 In Part 2 we will touch on endorphins and norepinephrine, and in Part 3 we will conclude by looking at GABA and glutamate.

Serotonin excess (Table 12-18)

On a recent office visit, Ms. H reports that most of the time she does not feel much of anything, but she still experiences panic attacks8,9,13,15 and is easily agitated.6,8 Her mother died recently, and Ms. H is concerned that she did not grieve.15-18 She failed her last semester in college and was indifferent to her failure.18 She sleeps poorly,8 is failing her creative classes, and wonders why she has lost her artistic inclination.16-18 Ms. H has difficulty with amotivation, planning, social interactions, and speech.16,17 All of those symptoms worsened after she was prescribed fluoxetine approximately 1 year ago for her “blues.” Ms. H is obese and continues to gain weight,2 though she frequently has diarrhea,3,4,7,8 loud peristalsis, and abdominal cramps.4,7,8 She sweats easily6-8 and her heart frequently races.8,9 Additionally, Ms. H’s primary care physician told her that she has “borderline diabetes.”2 She is prone to frequent bruising11 and is easy to shake, even when she is experiencing minimal anxiety.6-9 Ms. H had consulted with a neurologist because of unusual electrical “zapping” in her brain and muscle twitches.5,8,9,13 She had experienced a seizure as a child, but this was possibly related to hypernatremia,2 and she has not taken any anticonvulsant medication for several years.8 She exhibits hyperactive deep tendon reflexes and tremors5,7,9 and blinks frequently.6,9 She experiences hot flashes,3,6-8,14 does not tolerate heat, and prefers cooler weather.8,9 Her pains and aches,12,14 to which she has been prone all of her life, have recently become much worse, and she was diagnosed with fibromyalgia in part because she frequently feels stiff all over.10 She complains of strange tingling and prickling sensations in her hands and feet, especially when anxious.7,9,10 Her headaches also worsened and may be precipitated by bright light, as her pupils are usually dilated.5,7,9 Her hypertension is fairly controlled with medication.6,8-10 Ms. H says she experienced a psychotic episode when she was in her mid-teens,6,8 but reassures you that “she is not that bad now,” although she remains hypervigilant.13 Also while in her teens, Ms. H was treated with paroxetine and experienced restlessness, agitation, delirium, tachycardia, fluctuating blood pressure, diaphoresis, diarrhea, and neuromuscular excitation, which prompted discontinuation of the antidepressant.5-7,9,10

Impression. Ms. H exhibits symptoms associated with serotonin hyperactivity. Discontinuing and avoiding selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) would be prudent; prescribing an anticonvulsant would be reasonable. Using a GABAergic medication to suppress serotonin (eg, baclofen) is likely to help. Avoiding dopaminergic medications is a must. Antidepressive antipsychotics would be logical to use. The use of serotonin-suppressing medications may be considered. One may argue for the use of beta-blockers in such a patient.

Continue to: Serotonin deficiency

Serotonin deficiency (Table 114,19-29)

Mr. A is chronically depressed, hopeless,19 and easily angered.21 He does not believe anyone can help him.19 You are concerned for his safety because he had attempted to end his life by shooting himself in the chest.19,21,22,25 Even when he’s not particularly depressed, Mr. A does not enjoy much of anything.21,26,27 He becomes particularly agitated when he drinks alcohol,25 which unfortunately is common for him.29 He engages in binge eating to feel better; he knows this is not healthy but he cannot control his behavior.20,29 Mr. A is poorly compliant with his medications, even with a blood thinner, which he was prescribed due to an episode of deep vein thrombosis. He complains of chronic daily headaches and episodic migraines.23,24 He rarely blinks,23,28 his skin is dry and cool, his hair is brittle,23 his mouth is dry,14,23,27 and he constantly licks his chapped lips.14,26,27 Mr. A frequently has general body pain26,31 but is dismissive of his body aches and completely stops reporting pain when his depression gets particularly severe. When depressed, he is slow in movement and thinking.14,21,26,27 He is more concerned with anxiety than depression.21 Mr. A is plagued by constipation, abdominal pain, muscle tension, and episodes of shaking.14,26,27 He also frequently complains about chronic tinnitus.28

Impression. Mr. A shows symptoms associated with serotonin hypoactivity. SSRIs and any other antidepressants with serotonin activity would be an obvious choice for treatment. A mood-stabilizing antipsychotic with serotonin activity would be welcome in treatment. Thyroid hormone supplementation may be of value, especially if thyroid stimulating hormone level is high. Light therapy, a diet with food that contains tryptophan, psychotherapy, and exercise are desirable. Avoiding benzodiazepines would be a good idea.

Dopamine excess (Table 214,30-41)

Ms. L presents with complaints of “fibromyalgia” and “daily headaches,”14 and also dissociation (finding herself in places when she does not know how she got there) and “out-of-body experiences.”32 She is odd, and states that people do not understand her and that she is “different.”38 Her friend, who is present at the appointment, elaborates on Ms. L’s bizarreness and oddness in behavior, out-of-context emotions, suspiciousness, paranoia, and possible hallucinations.35,36,38 Ms. L discloses frequent diffuse body pains, headaches, nausea, excessive salivation, and tongue burning, as well as muscle twitching.14 Sex worsens her headaches and body pain. She reports seizures that are not registered on EEG. In the office, she is suspicious, exhibits odd posturing, tends to misinterpret your words, and makes you feel uncomfortable. Anxiety38 and multiple obsessive-compulsive symptoms, especially excessive cleaning and grooming, complicate Ms. L’s life.31,32,34 On examination, she is hypertensive, and she has scars caused by self-cutting and skin picking on her arms.30-32 An electrocardiogram shows an elevated heart rate, widened QRS complex, and ectopic heartbeats.14 Ms. L has experienced trichotillomania since adolescence32-34 and her fingernails are bitten to the skin.34 She has difficulty with impulse control, and thrill-seeking is a prominent part of her life, mainly via gambling, compulsive sex, and compulsive buying.35,36 She also says she experiences indigestion and delayed gastric emptying.37

Impression. Ms. L exhibits multiple symptoms associated with dopamine excess. Dopamine antagonists should be considered and may help not only with her psychiatric symptoms but also with her pain symptoms. Bupropion (as a dopamine agonist), caffeine, and stimulants should be avoided.

Excessive dopamine is, in extreme cases, associated with somatic psychosis, somatic symptom disorder, factitious disorder, pain disorder, and hypochondria.39 It may come with odd and bizarre/peculiar symptoms out of proportion with objectively identified pathology. These symptoms are common in chronic pain and headache patients, and need to be addressed by appropriate use of dopamine antagonizing medications.39

Continue to: Dopamine deficiency

Dopamine deficiency (Table 24,14,20,38,40-43)

Mr. W experiences widespread pain, including chronic back pain, headaches, and abdominal pain. He also has substantial anhedonia, lack of interest, procrastination, and hypersomnia.41,42 He is apathetic and has difficulty getting up in the morning.41,42 Unusual tiredness and weakness drive him to overuse caffeine; he states that 5 Mountain Dews and 4 cups of regular coffee a day make his headaches bearable.38,41-43 Sex also improves his headaches. Since childhood, he has taken stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. He reports that occasional use of cocaine helps ease his pain and depression. Mr. W’s wife is concerned with her husband’s low sexual drive and alcohol consumption, and discloses that he has periodic trouble with gambling. Mr. W was forced into psychotherapy but never was able to work productively with his therapist.38,41-43 He loves eating and cannot control his weight.40 This contrasts with episodic anorexia he experienced when he was younger.20 His face is usually emotionless.43 Mr. W is prone to constipation.14 His restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are so bad that his wife refuses to share a bed with him.14 He is clumsy and has a problem with repetitive motor tasks.43 A paucity of speech, limited eye contact, poor grooming, and difficulty forming therapeutic alliances have long been part of Mr. W’s history.38,42,43 On physical examination, he has a dry mouth; he is stiff, tremulous, and hypotensive.14

Impression. Mr. W shows multiple symptoms associated with dopamine deficiency. Bupropion may be reasonable to consider. Dopamine augmentation via the use of stimulants is warranted in such patients, especially if stimulants had not been tried before (lisdexamfetamine would be a good choice to minimize addictive potential). For a patient with dopamine deficiency, levodopa may improve more than just restless legs. Amantadine may improve dopaminergic signaling through the accelerated dopamine release and decrease in presynaptic uptake, so this medication may be carefully tried.44 Pain treatment would not be successful for Mr. W without simultaneous treatment for his substance use.

Bottom Line

Both high and low levels of serotonin and dopamine may be associated with certain psychiatric and medical symptoms and disorders. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation, and tailor treatment accordingly.

Related Resources

- Abell SR, El-Mallakh RS. Serotonin-mediated anxiety: How to recognize and treat it. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):37-40. doi:10.12788/cp.0168

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Paroxetine • Paxil

It is unfortunate that, in some clinical areas, medical conditions are still treated by name and not based on the underlying pathological process. It would be odd in 2022 to treat “dropsy” instead of heart or kidney disease (2 very different causes of edema). Similarly, if the FDA had been approving drugs 150 years ago, we would have medications on label for “dementia praecox,” not schizophrenia or Alzheimer disease. With the help of DSM-5, psychiatry still resides in the descriptive symptomatic world of disorders.

In the United States, thanks to Freud, psychiatric symptoms became separated from medical symptoms, which made it more difficult to associate psychiatric manifestations with the underlying pathophysiology. Though the physical manifestations that parallel emotional symptoms—such as the dry mouth of anxiety, the tremor and leg weakness of fear, the constipation and blurry vision of depression, the breathing difficulty of anger, the abdominal pain of stress, the blushing of shyness, the palpitations of flashbacks, and endless others—are well known, the present classification of psychiatric disorders is blind to it. Neurochemical causes of gastrointestinal spasm or muscle tension are better researched than underlying central neurochemistry, though the same neurotransmitters drive them.

Can the biochemistry of psychiatric symptoms be judged on the basis of peripheral symptoms? Can the mental manifestations be connected to biological causation, and vice versa? Would psychiatrists be better off selecting treatments by recognizing involved neurotransmitters instead of addressing descriptive “depression, anxiety, and psychosis”? Each of these clinical syndromes may be caused by entirely different underlying neuronal mechanisms. Such mechanisms could be suggested if medical symptoms (which are measurable and objective) would become part of the psychiatric diagnosis. Is treating the “cough” sufficient, or would recognition that tuberculosis caused the cough guide better treatment? Is it time to abandon descriptive conditions and replace them with a specific “mechanism-based” viewpoint?

Ample research has shown that serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, endorphins, glutamate, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) are the neurotransmitters most responsible in the process of both psychiatric disorders and chronic pain. These neurotransmitters are involved in much more than emotions (including the feeling of pain). An abundance of medical symptom clusters point toward which neurotransmitter dysfunction may be leading in specific cases of distinct types of depression, psychosis, anxiety, or “chronic pain.” Even presently, there are medications available (both for FDA-approved indications and off-label) that can be used to regulate these neurotransmitters, allowing practitioners to target the possible biological underlining of psychiatric or pain pathology. Hopefully, in the not-so-distant future, there will be specific medications for serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenergic depression as well as for GABAergic anxiety, endorphin psychosis, noradrenergic insomnia, and similar conditions.

Numerous neurotransmitters may be connected to both depression and pain in all their forms. These include (but are not limited to) prostaglandins, bradykinins, substance P, potassium, magnesium, calcium, histamine, adenosine triphosphate, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), nitric oxide (NO), cholecystokinin 7 (CCK7), neurotrophic growth factor (NGF), neurotensin, acetylcholine (Ach), oxytocin, cannabinoids, and others. These have not been researched sufficiently to identify their clinical presentation of excessive or insufficient availability at the sites of neurotransmission. It is difficult to draw conclusions about what kind of clinical symptoms they may cause (outside of pain), and therefore, they are not addressed in this article.

Both high and low levels of certain neurotransmitters may be associated with psychiatric conditions and chronic pain. Too much is as bad as too little.1 This applies to both quantity of neurotransmitters as well as quality of the corresponding receptor activity. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation. Reading indirect signs of bodily functions is a basic clinical skill that should not be forgotten, even in the time of advanced technology.

A different way of viewing psychiatric disorders

In this article, we present 4 hypothetical clinical cases to emphasize a possible way of analyzing symptoms to identify underlying pathology and guide more effective treatment. In no way do these descriptions reflect the entire set of symptoms caused by neurotransmitters; we created them based on what is presently known or suspected, and extensive research is required to confirm or disprove what we describe here.

Continue to: There are no well-recognized...

There are no well-recognized, well-established, reliable, or validated syndromes described in our work. Our goal is to suggest an alternative way of looking at psychiatric disorders by viewing syndromal presentation through the lens of specific neurotransmitters. The collection of symptoms associated with various neurotransmitters as presented in this hypothesis is not complete. We have assembled what is described in the literature as a suggestion for specific future research. We simplified these clinical presentations by omitting scenarios in which a specific neurotransmitter increases in one area but not another. For example, all the symptoms of dopamine excess we describe would not have to occur concurrently in the same patient, but they may develop in certain patients depending on which dopaminergic pathway is exhibiting excess activity. Such distinctions may be established only by exhaustive research not yet conducted.

Our proposal may seem radical, but it truly is not. For example, if we know that dopamine excess may cause seizures, psychosis, and blood pressure elevation, why not consider dopamine excess as an underlying cause in a patient with depression who exhibits these symptoms simultaneously? And why not call it “dopamine excess syndrome”? We already have “serotonin syndrome” for a patient experiencing a serotonin storm. However, using the same logic, it should be called “serotonin excess syndrome.” And if we know of “serotonin excess syndrome,” why not consider “serotonin deficiency syndrome”?

In Part 1 of this article, we discuss serotonin and dopamine. Table 1 outlines medical and psychiatric symptoms that likely reflect serotonin excess2-18 and deficiency,14,19-29 and Table 2 lists symptoms that likely reflect dopamine excess14,30-41 and deficiency.4,14,20,38,40-43 In Part 2 we will touch on endorphins and norepinephrine, and in Part 3 we will conclude by looking at GABA and glutamate.

Serotonin excess (Table 12-18)

On a recent office visit, Ms. H reports that most of the time she does not feel much of anything, but she still experiences panic attacks8,9,13,15 and is easily agitated.6,8 Her mother died recently, and Ms. H is concerned that she did not grieve.15-18 She failed her last semester in college and was indifferent to her failure.18 She sleeps poorly,8 is failing her creative classes, and wonders why she has lost her artistic inclination.16-18 Ms. H has difficulty with amotivation, planning, social interactions, and speech.16,17 All of those symptoms worsened after she was prescribed fluoxetine approximately 1 year ago for her “blues.” Ms. H is obese and continues to gain weight,2 though she frequently has diarrhea,3,4,7,8 loud peristalsis, and abdominal cramps.4,7,8 She sweats easily6-8 and her heart frequently races.8,9 Additionally, Ms. H’s primary care physician told her that she has “borderline diabetes.”2 She is prone to frequent bruising11 and is easy to shake, even when she is experiencing minimal anxiety.6-9 Ms. H had consulted with a neurologist because of unusual electrical “zapping” in her brain and muscle twitches.5,8,9,13 She had experienced a seizure as a child, but this was possibly related to hypernatremia,2 and she has not taken any anticonvulsant medication for several years.8 She exhibits hyperactive deep tendon reflexes and tremors5,7,9 and blinks frequently.6,9 She experiences hot flashes,3,6-8,14 does not tolerate heat, and prefers cooler weather.8,9 Her pains and aches,12,14 to which she has been prone all of her life, have recently become much worse, and she was diagnosed with fibromyalgia in part because she frequently feels stiff all over.10 She complains of strange tingling and prickling sensations in her hands and feet, especially when anxious.7,9,10 Her headaches also worsened and may be precipitated by bright light, as her pupils are usually dilated.5,7,9 Her hypertension is fairly controlled with medication.6,8-10 Ms. H says she experienced a psychotic episode when she was in her mid-teens,6,8 but reassures you that “she is not that bad now,” although she remains hypervigilant.13 Also while in her teens, Ms. H was treated with paroxetine and experienced restlessness, agitation, delirium, tachycardia, fluctuating blood pressure, diaphoresis, diarrhea, and neuromuscular excitation, which prompted discontinuation of the antidepressant.5-7,9,10

Impression. Ms. H exhibits symptoms associated with serotonin hyperactivity. Discontinuing and avoiding selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) would be prudent; prescribing an anticonvulsant would be reasonable. Using a GABAergic medication to suppress serotonin (eg, baclofen) is likely to help. Avoiding dopaminergic medications is a must. Antidepressive antipsychotics would be logical to use. The use of serotonin-suppressing medications may be considered. One may argue for the use of beta-blockers in such a patient.

Continue to: Serotonin deficiency

Serotonin deficiency (Table 114,19-29)

Mr. A is chronically depressed, hopeless,19 and easily angered.21 He does not believe anyone can help him.19 You are concerned for his safety because he had attempted to end his life by shooting himself in the chest.19,21,22,25 Even when he’s not particularly depressed, Mr. A does not enjoy much of anything.21,26,27 He becomes particularly agitated when he drinks alcohol,25 which unfortunately is common for him.29 He engages in binge eating to feel better; he knows this is not healthy but he cannot control his behavior.20,29 Mr. A is poorly compliant with his medications, even with a blood thinner, which he was prescribed due to an episode of deep vein thrombosis. He complains of chronic daily headaches and episodic migraines.23,24 He rarely blinks,23,28 his skin is dry and cool, his hair is brittle,23 his mouth is dry,14,23,27 and he constantly licks his chapped lips.14,26,27 Mr. A frequently has general body pain26,31 but is dismissive of his body aches and completely stops reporting pain when his depression gets particularly severe. When depressed, he is slow in movement and thinking.14,21,26,27 He is more concerned with anxiety than depression.21 Mr. A is plagued by constipation, abdominal pain, muscle tension, and episodes of shaking.14,26,27 He also frequently complains about chronic tinnitus.28

Impression. Mr. A shows symptoms associated with serotonin hypoactivity. SSRIs and any other antidepressants with serotonin activity would be an obvious choice for treatment. A mood-stabilizing antipsychotic with serotonin activity would be welcome in treatment. Thyroid hormone supplementation may be of value, especially if thyroid stimulating hormone level is high. Light therapy, a diet with food that contains tryptophan, psychotherapy, and exercise are desirable. Avoiding benzodiazepines would be a good idea.

Dopamine excess (Table 214,30-41)

Ms. L presents with complaints of “fibromyalgia” and “daily headaches,”14 and also dissociation (finding herself in places when she does not know how she got there) and “out-of-body experiences.”32 She is odd, and states that people do not understand her and that she is “different.”38 Her friend, who is present at the appointment, elaborates on Ms. L’s bizarreness and oddness in behavior, out-of-context emotions, suspiciousness, paranoia, and possible hallucinations.35,36,38 Ms. L discloses frequent diffuse body pains, headaches, nausea, excessive salivation, and tongue burning, as well as muscle twitching.14 Sex worsens her headaches and body pain. She reports seizures that are not registered on EEG. In the office, she is suspicious, exhibits odd posturing, tends to misinterpret your words, and makes you feel uncomfortable. Anxiety38 and multiple obsessive-compulsive symptoms, especially excessive cleaning and grooming, complicate Ms. L’s life.31,32,34 On examination, she is hypertensive, and she has scars caused by self-cutting and skin picking on her arms.30-32 An electrocardiogram shows an elevated heart rate, widened QRS complex, and ectopic heartbeats.14 Ms. L has experienced trichotillomania since adolescence32-34 and her fingernails are bitten to the skin.34 She has difficulty with impulse control, and thrill-seeking is a prominent part of her life, mainly via gambling, compulsive sex, and compulsive buying.35,36 She also says she experiences indigestion and delayed gastric emptying.37

Impression. Ms. L exhibits multiple symptoms associated with dopamine excess. Dopamine antagonists should be considered and may help not only with her psychiatric symptoms but also with her pain symptoms. Bupropion (as a dopamine agonist), caffeine, and stimulants should be avoided.

Excessive dopamine is, in extreme cases, associated with somatic psychosis, somatic symptom disorder, factitious disorder, pain disorder, and hypochondria.39 It may come with odd and bizarre/peculiar symptoms out of proportion with objectively identified pathology. These symptoms are common in chronic pain and headache patients, and need to be addressed by appropriate use of dopamine antagonizing medications.39

Continue to: Dopamine deficiency

Dopamine deficiency (Table 24,14,20,38,40-43)

Mr. W experiences widespread pain, including chronic back pain, headaches, and abdominal pain. He also has substantial anhedonia, lack of interest, procrastination, and hypersomnia.41,42 He is apathetic and has difficulty getting up in the morning.41,42 Unusual tiredness and weakness drive him to overuse caffeine; he states that 5 Mountain Dews and 4 cups of regular coffee a day make his headaches bearable.38,41-43 Sex also improves his headaches. Since childhood, he has taken stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. He reports that occasional use of cocaine helps ease his pain and depression. Mr. W’s wife is concerned with her husband’s low sexual drive and alcohol consumption, and discloses that he has periodic trouble with gambling. Mr. W was forced into psychotherapy but never was able to work productively with his therapist.38,41-43 He loves eating and cannot control his weight.40 This contrasts with episodic anorexia he experienced when he was younger.20 His face is usually emotionless.43 Mr. W is prone to constipation.14 His restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are so bad that his wife refuses to share a bed with him.14 He is clumsy and has a problem with repetitive motor tasks.43 A paucity of speech, limited eye contact, poor grooming, and difficulty forming therapeutic alliances have long been part of Mr. W’s history.38,42,43 On physical examination, he has a dry mouth; he is stiff, tremulous, and hypotensive.14

Impression. Mr. W shows multiple symptoms associated with dopamine deficiency. Bupropion may be reasonable to consider. Dopamine augmentation via the use of stimulants is warranted in such patients, especially if stimulants had not been tried before (lisdexamfetamine would be a good choice to minimize addictive potential). For a patient with dopamine deficiency, levodopa may improve more than just restless legs. Amantadine may improve dopaminergic signaling through the accelerated dopamine release and decrease in presynaptic uptake, so this medication may be carefully tried.44 Pain treatment would not be successful for Mr. W without simultaneous treatment for his substance use.

Bottom Line

Both high and low levels of serotonin and dopamine may be associated with certain psychiatric and medical symptoms and disorders. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation, and tailor treatment accordingly.

Related Resources

- Abell SR, El-Mallakh RS. Serotonin-mediated anxiety: How to recognize and treat it. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):37-40. doi:10.12788/cp.0168

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Stahl SM. Dazzled by the dominions of dopamine: clinical roles of D3, D2, and D1 receptors. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(4):305-311.

2. Young RL, Lumsden AL, Martin AM, et al. Augmented capacity for peripheral serotonin release in human obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(11):1880-1889.

3. Ahlman H. Serotonin and carcinoid tumors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7(Suppl 7):S79-S85.

4. Terry N, Margolis KG. Serotonergic mechanisms regulating the GI tract: experimental evidence and therapeutic relevance. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;239:319-342.

5. Prakash S, Belani P, Trivedi A. Headache as a presenting feature in patients with serotonin syndrome: a case series. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(2):148-153.

6. van Ewijk CE, Jacobs GE, Girbes ARJ. Unsuspected serotonin toxicity in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):85.

7. Pedavally S, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Serotonin syndrome in the intensive care unit: clinical presentations and precipitating medications. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(1):108-113.

8. Nguyen H, Pan A, Smollin C, et al. An 11-year retrospective review of cyproheptadine use in serotonin syndrome cases reported to the California Poison Control System. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(2):327-334.

9. Ansari H, Kouti L. Drug interaction and serotonin toxicity with opioid use: another reason to avoid opioids in headache and migraine treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(8):50.

10. Ott M, Mannchen JK, Jamshidi F, et al. Management of severe arterial hypertension associated with serotonin syndrome: a case report analysis based on systematic review techniques. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2019;9:2045125318818814. doi:10.1177/2045125318818814

11. Cerrito F, Lazzaro MP, Gaudio E, et al. 5HT2-receptors and serotonin release: their role in human platelet aggregation. Life Sci. 1993;53(3):209-215.

12. Ohayon MM. Pain sensitivity, depression, and sleep deprivation: links with serotoninergic dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(16):1243-1245.

13. Maron E, Shlik J. Serotonin function in panic disorder: important, but why? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(1):1-11.

14. Hall JE, Guyton AC. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 12th ed. Spanish version. Elsevier; 2011:120,199,201-204,730-740.

15. Garland EJ, Baerg EA. Amotivational syndrome associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(2):181-186.

16. George MS, Trimble MR. A fluvoxamine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in a patient with comorbid Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(10):379-380.

17. Hoehn-Saric R, Harris GJ, Pearlson GD, et al. A fluoxetine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in an obsessive compulsive patient. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(3):131-133.

18. Hoehn-Saric R, Lipsey JR, McLeod DR. Apathy and indifference in patients on fluvoxamine and fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(5):343-345.

19. Samuelsson M, Jokinen J, Nordström AL, et al. CSF 5-HIAA, suicide intent and hopelessness in the prediction of early suicide in male high-risk suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):44-47.

20. Brewerton TD. Clinical Handbook of Eating Disorders: An Integrated Approach. CRC Press; 2004:257-281.

21. Mann JJ, Oquendo M, Underwood MD, et al. The neurobiology of suicide risk: a review for the clinician. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 2:7-116.

22. Mann JJ, Malone KM. Cerebrospinal fluid amines and higher-lethality suicide attempts in depressed inpatients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(2):162-171.

23. Joseph R, Welch KM, D’Andrea G. Serotonergic hypofunction in migraine: a synthesis of evidence based on platelet dense body dysfunction. Cephalalgia. 1989;9(4):293-299.

24. Pakalnis A, Splaingard M, Splaingard D, et al. Serotonin effects on sleep and emotional disorders in adolescent migraine. Headache. 2009;49(10):1486-1492.

25. Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Nielsen DA, et al. Low brain serotonin turnover rate (low CSF 5-HIAA) and impulsive violence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1995;20(4):271-275.

26. Liu Y, Zhao J, Fan X, et al. Dysfunction in serotonergic and noradrenergic systems and somatic symptoms in psychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:286.

27. Ginsburg GS, Riddle MA, Davies M. Somatic symptoms in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(10):1179-1187.

28. O’Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, et al. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(12):980-990.

29. Fortuna JL. Sweet preference, sugar addiction and the familial history of alcohol dependence: shared neural pathways and genes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(2):147-151.

30. Stanley B, Sher L, Wilson S, et al. Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, endogenous opioids and monoamine neurotransmitters. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(1-2):134-140.

31. Graybiel AM, Saka E. A genetic basis for obsessive grooming. Neuron. 2002;33(1):1-2.

32. Tse W, Hälbig TD. Skin picking in Parkinson’s disease: a behavioral side-effect of dopaminergic treatment? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(2):214.

33. Ayaydın H. Probable emergence of symptoms of trichotillomania by atomoxetine: a case report. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2019;29(2)220-222.

34. Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:9782702. doi:10.1155/2016/9782702

35. Clark CA, Dagher A. The role of dopamine in risk taking: a specific look at Parkinson’s disease and gambling. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:196.

36. Norbury A, Husain M. Sensation-seeking: dopaminergic modulation and risk for psychopathology. Behav Brain Res. 2015;288:79-93.

37. Chen TS, Chang FY. Elevated serum dopamine increases while coffee consumption decreases the occurrence of reddish streaks in the intact stomach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(12):1810-1814.

38. Wong-Riley MT. Neuroscience Secrets. 1st edition. Spanish version. Hanley & Belfus; 1999:420-429.

39. Arbuck DM. Antipsychotics, dopamine, and pain. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):25-29,31.

40. Bello NT, Hajnal A. Dopamine and binge eating behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97(1):25-33.

41. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70 Suppl 4:1-46.

42. Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, et al. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):495-506.

43. Gepshtein S, Li X, Snider J, et al. Dopamine function and the efficiency of human movement. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(3):645-657.

44. Scarff JR. The ABCDs of treating tardive dyskinesia. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):21,55.

1. Stahl SM. Dazzled by the dominions of dopamine: clinical roles of D3, D2, and D1 receptors. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(4):305-311.

2. Young RL, Lumsden AL, Martin AM, et al. Augmented capacity for peripheral serotonin release in human obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(11):1880-1889.

3. Ahlman H. Serotonin and carcinoid tumors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7(Suppl 7):S79-S85.

4. Terry N, Margolis KG. Serotonergic mechanisms regulating the GI tract: experimental evidence and therapeutic relevance. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;239:319-342.

5. Prakash S, Belani P, Trivedi A. Headache as a presenting feature in patients with serotonin syndrome: a case series. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(2):148-153.

6. van Ewijk CE, Jacobs GE, Girbes ARJ. Unsuspected serotonin toxicity in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):85.

7. Pedavally S, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Serotonin syndrome in the intensive care unit: clinical presentations and precipitating medications. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(1):108-113.

8. Nguyen H, Pan A, Smollin C, et al. An 11-year retrospective review of cyproheptadine use in serotonin syndrome cases reported to the California Poison Control System. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(2):327-334.

9. Ansari H, Kouti L. Drug interaction and serotonin toxicity with opioid use: another reason to avoid opioids in headache and migraine treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(8):50.

10. Ott M, Mannchen JK, Jamshidi F, et al. Management of severe arterial hypertension associated with serotonin syndrome: a case report analysis based on systematic review techniques. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2019;9:2045125318818814. doi:10.1177/2045125318818814

11. Cerrito F, Lazzaro MP, Gaudio E, et al. 5HT2-receptors and serotonin release: their role in human platelet aggregation. Life Sci. 1993;53(3):209-215.

12. Ohayon MM. Pain sensitivity, depression, and sleep deprivation: links with serotoninergic dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(16):1243-1245.

13. Maron E, Shlik J. Serotonin function in panic disorder: important, but why? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(1):1-11.

14. Hall JE, Guyton AC. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 12th ed. Spanish version. Elsevier; 2011:120,199,201-204,730-740.

15. Garland EJ, Baerg EA. Amotivational syndrome associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(2):181-186.

16. George MS, Trimble MR. A fluvoxamine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in a patient with comorbid Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(10):379-380.

17. Hoehn-Saric R, Harris GJ, Pearlson GD, et al. A fluoxetine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in an obsessive compulsive patient. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(3):131-133.

18. Hoehn-Saric R, Lipsey JR, McLeod DR. Apathy and indifference in patients on fluvoxamine and fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(5):343-345.

19. Samuelsson M, Jokinen J, Nordström AL, et al. CSF 5-HIAA, suicide intent and hopelessness in the prediction of early suicide in male high-risk suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):44-47.

20. Brewerton TD. Clinical Handbook of Eating Disorders: An Integrated Approach. CRC Press; 2004:257-281.

21. Mann JJ, Oquendo M, Underwood MD, et al. The neurobiology of suicide risk: a review for the clinician. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 2:7-116.

22. Mann JJ, Malone KM. Cerebrospinal fluid amines and higher-lethality suicide attempts in depressed inpatients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(2):162-171.

23. Joseph R, Welch KM, D’Andrea G. Serotonergic hypofunction in migraine: a synthesis of evidence based on platelet dense body dysfunction. Cephalalgia. 1989;9(4):293-299.

24. Pakalnis A, Splaingard M, Splaingard D, et al. Serotonin effects on sleep and emotional disorders in adolescent migraine. Headache. 2009;49(10):1486-1492.

25. Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Nielsen DA, et al. Low brain serotonin turnover rate (low CSF 5-HIAA) and impulsive violence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1995;20(4):271-275.

26. Liu Y, Zhao J, Fan X, et al. Dysfunction in serotonergic and noradrenergic systems and somatic symptoms in psychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:286.

27. Ginsburg GS, Riddle MA, Davies M. Somatic symptoms in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(10):1179-1187.

28. O’Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, et al. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(12):980-990.

29. Fortuna JL. Sweet preference, sugar addiction and the familial history of alcohol dependence: shared neural pathways and genes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(2):147-151.

30. Stanley B, Sher L, Wilson S, et al. Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, endogenous opioids and monoamine neurotransmitters. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(1-2):134-140.

31. Graybiel AM, Saka E. A genetic basis for obsessive grooming. Neuron. 2002;33(1):1-2.

32. Tse W, Hälbig TD. Skin picking in Parkinson’s disease: a behavioral side-effect of dopaminergic treatment? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(2):214.

33. Ayaydın H. Probable emergence of symptoms of trichotillomania by atomoxetine: a case report. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2019;29(2)220-222.

34. Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:9782702. doi:10.1155/2016/9782702

35. Clark CA, Dagher A. The role of dopamine in risk taking: a specific look at Parkinson’s disease and gambling. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:196.

36. Norbury A, Husain M. Sensation-seeking: dopaminergic modulation and risk for psychopathology. Behav Brain Res. 2015;288:79-93.

37. Chen TS, Chang FY. Elevated serum dopamine increases while coffee consumption decreases the occurrence of reddish streaks in the intact stomach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(12):1810-1814.

38. Wong-Riley MT. Neuroscience Secrets. 1st edition. Spanish version. Hanley & Belfus; 1999:420-429.

39. Arbuck DM. Antipsychotics, dopamine, and pain. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):25-29,31.

40. Bello NT, Hajnal A. Dopamine and binge eating behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97(1):25-33.

41. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70 Suppl 4:1-46.

42. Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, et al. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):495-506.

43. Gepshtein S, Li X, Snider J, et al. Dopamine function and the efficiency of human movement. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(3):645-657.

44. Scarff JR. The ABCDs of treating tardive dyskinesia. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):21,55.