User login

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

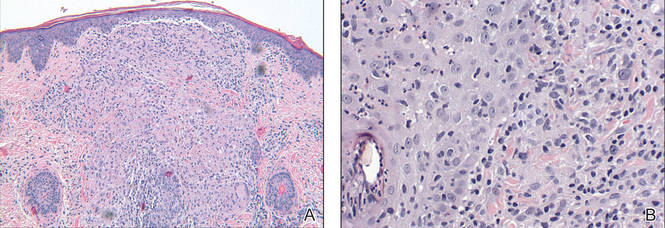

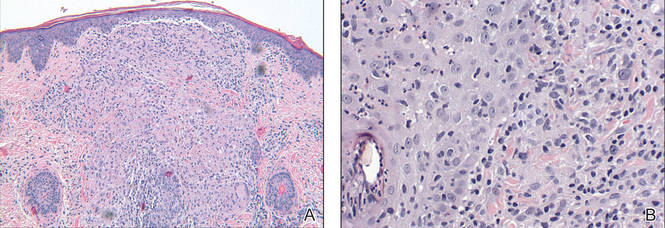

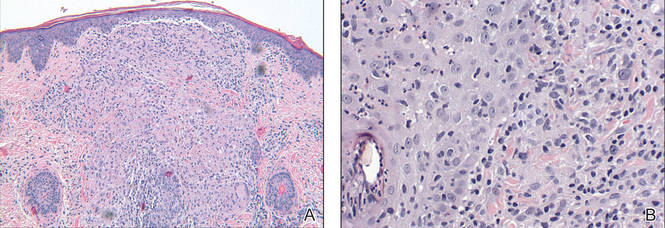

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.

- Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.

- Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.

- Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

A 7-year-old boy was referred to the dermatology department with a red, bumpy, nonpruritic facial rash of 6 months’ duration. There was no identifiable trigger. The lesions were grouped around the nose and mouth with some extension onto the neck. He was treated with pimecrolimus cream 1% for presumed atopic dermatitis with good response, but the rash recurred soon thereafter. A biopsy performed at an outside institution shortly after rash onset showed dermal granulomas, leading to a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (lupus pernio). Prior to presenting to our clinic, treatment with topical and oral corticosteroids failed. He had a normal chest radiograph, ophthalmologic examination, and angiotensin-converting enzyme level to exclude extracutaneous sarcoidosis. On physical examination the patient had innumerable, monomorphic, flesh-colored to erythematous papules confluent over the medial eyelids and canthi, perinasal skin, cutaneous lips, and preauricular skin extending onto the lateral aspect of the neck. There was superimposed scale around the mouth.