User login

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

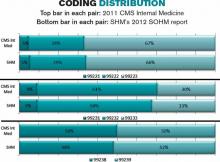

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.