User login

The treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection represents a clinical challenge.1,2 Up to 3% of patients with HIV infection are estimated to have psoriasis. Although this prevalence is similar to the general population, psoriatic disease in patients with HIV tends to be more severe, refractory, and more difficult to treat.3-5 Additionally, up to half of patients with comorbid HIV and psoriasis also have substantial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).1,6

Drug treatments for psoriasis and PsA often are immunosuppressive; as such, the treatment of psoriasis in this patient population requires careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits of treatment as well as fastidious monitoring for the emergence of potentially adverse treatment effects.1 A careful diagnostic process to determine the severity of HIV-associated psoriasis and to select the appropriate treatment relative to the patient’s immunologic status is of critical importance.3

Presentation of Psoriasis in Patients With HIV Infection

The presentation and severity of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection is highly variable and is often related to the degree of immune suppression experienced by the patient.3,7 In some individuals, psoriasis may be the first outward manifestation of HIV, whereas in others, it only manifests after HIV has progressed to AIDS.7

Recognition of the atypical presentations of psoriasis that are frequently seen in patients with HIV infection can help to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment to improve patient outcomes.3,8 Psoriasis vulgaris, for example, typically presents as erythematous plaques with silvery-white scales on extensor surfaces of the body such as the knees and elbows. However, in patients with HIV, psoriasis vulgaris may present with scales that appear thick and oyster shell–like instead of silvery-white; these lesions also may occur on flexural areas rather than extensor surfaces.8 Similarly, the sudden onset of widespread psoriasis in otherwise healthy persons should trigger suspicion for HIV infection and recommendations for appropriate testing, even when no risk factors are present.8

Guttate, inverse, and erythrodermic psoriasis are the most common subtypes in patients with HIV infection, though all clinical subtypes may occur. Overlapping of psoriasis subtypes often occurs in individuals with HIV infection and should serve as a red flag to recommend screening for HIV.5,8 Acral involvement, frequently with pustules and occasionally with severe destructive nail changes, is commonly seen in patients with HIV-associated psoriasis.7,9 In cases involving severe psoriatic exacerbations among individuals with AIDS, there is a heightened risk of developing systemic infections, including superinfection of Staphylococcus aureus, which is a rare occurrence in immunocompetent patients with psoriasis.7,10,11

Therapeutic Options

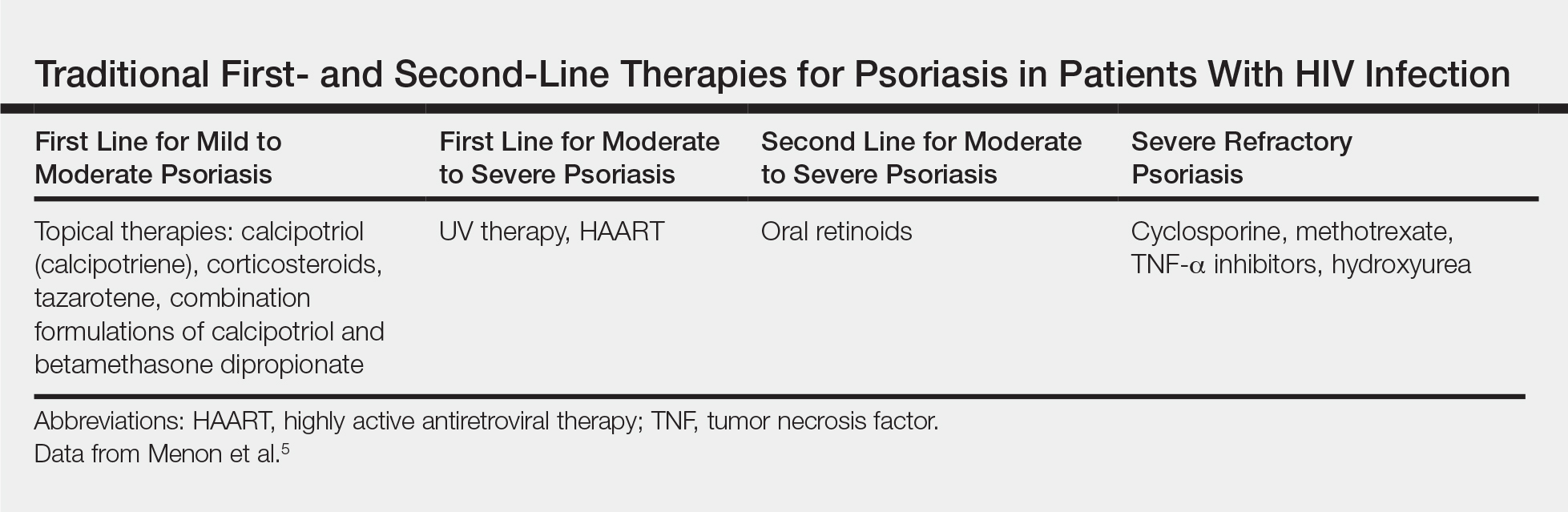

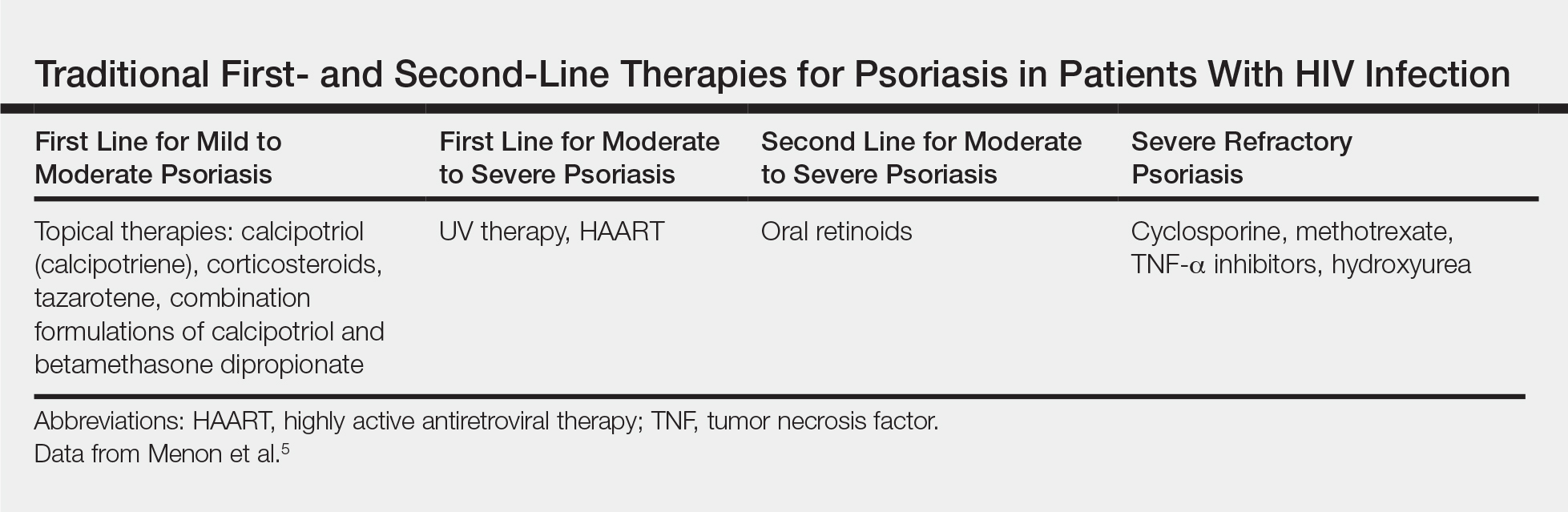

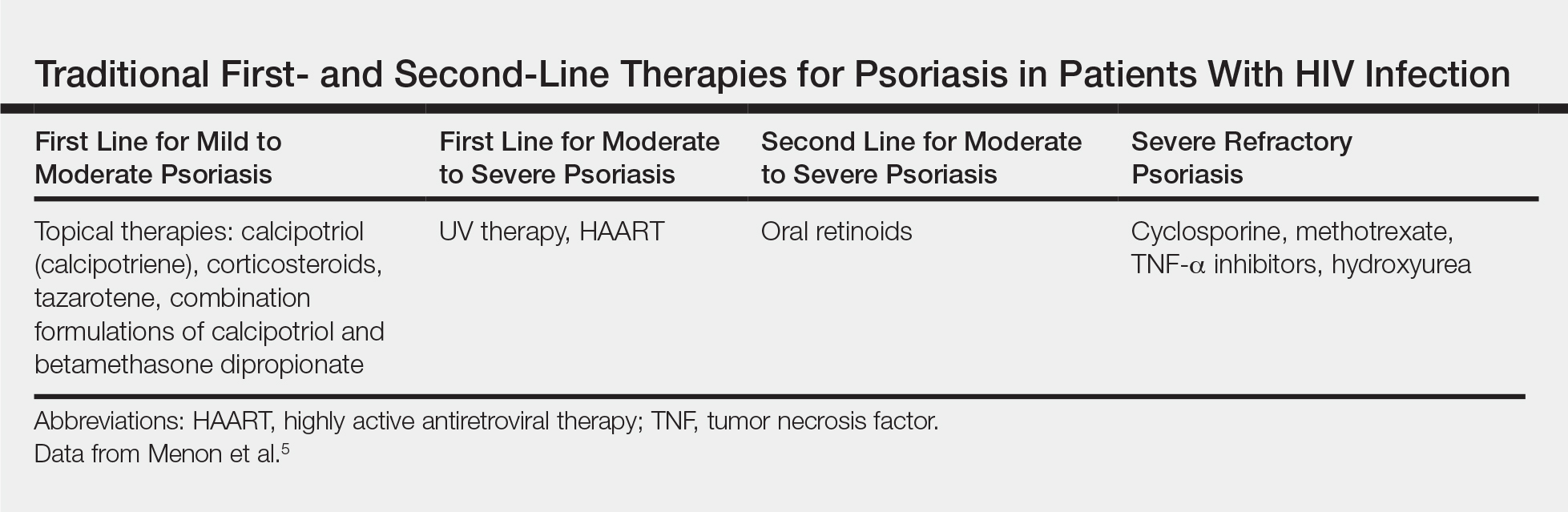

Because the clinical course of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection is frequently progressive and refractory to treatment, traditional first- and second-line therapies (Table) including topical agents, phototherapy, and oral retinoids may be unable to achieve lasting control of both skin and joint manifestations.1

Topical Therapy

As in the general population, targeted therapies such as topical agents are recommended as first-line treatment of mild HIV-associated psoriasis.12 Topical corticosteroids, calcipotriol, tazarotene, and formulations combining 2 of these medications form the cornerstone of topical therapies for mild psoriasis in patients with HIV infection. These agents have the advantage of possessing limited and localized effects, making it unlikely for them to increase immunosuppression in patients with HIV infection. They generally can be safely used in patients with HIV infection, and their side-effect profile in patients with HIV infection is similar to the general population.12 However, calcipotriol is the least desirable for use in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be a side effect of antiretroviral drugs.4

UV Phototherapy

Topical therapy is limited by its lack of potency; limited field coverage; and the inconvenience of application, particularly in patients with more widespread disease.12 Therefore, UV phototherapy is preferred as first-line treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. UV phototherapy has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and inflammation and result in clinical improvement of HIV-associated psoriasis; moreover, most of the reports in the literature support it as an option that will not increase immunocompromise in patients with HIV infection.12

Caution is warranted, however, regarding the immunomodulatory effects of UV therapies, which may result in an increased risk for skin cancer and diminished resistance to infection, which can be of particular concern in immunocompromised patients who are already at risk.7,13,14 In patients who are candidates for phototherapy, HIV serology and close monitoring of viral load and CD4 lymphocyte count before treatment, at monthly interludes throughout treatment, and 3 months following the cessation of treatment have been recommended.7,15 Careful consideration of the risk-benefit ratio of phototherapy for individual patients, including the patient’s stage of HIV disease, the degree of discomfort, disfigurement, and disability caused by the psoriasis (or other dermatologic condition), as well as the availability of alternative treatment options is essential.7,16

Systemic Agents

In patients who are intolerant of or unresponsive to antiretroviral therapy, topical therapies, and phototherapy, traditional systemic agents may be considered,12 including acitretin, methotrexate, and cyclosporine. However, updated guidelines indicate that methotrexate and cyclosporine should be avoided in this population given the risk for increased immunosuppression with these agents.4,17

Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, continue to be important options for second-line psoriasis treatment in patients with comorbid HIV infection, either as monotherapy or in association with phototherapy.3 Acitretin has the notable benefit of not causing or worsening immune compromise; however, its use is less than desirable in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be a side effect of antiretroviral drugs.4,12 Providers also must be aware of the possible association between acitretin (and other antiretrovirals) and pancreatitis, remaining vigilant in monitoring patients for this adverse effect.3

Biologics

The relatively recent addition of cytokine-suppressive biologic agents to the treatment armamentarium has transformed the management of psoriasis in otherwise healthy individuals. These agents have been shown to possess an excellent safety and efficacy profile.12 However, their use in patients with HIV infection has been mired in concerns regarding a potential increase in the risk for opportunistic infections, sepsis, and HIV disease progression in this patient population.7,12

Case reports have detailed the safe treatment of recalcitrant HIV-associated psoriasis with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, such as etanercept.7,12 In most of these case reports, no harm to CD4 lymphocyte counts, serum viral loads, overall immune status, and susceptibility to infection have been noted; on the contrary, CD4 count increased in most patients following treatment with biologic agents.12 Because patients with HIV infection tend to be excluded from clinical trials, anecdotal evidence derived from case reports and case series often provides clinically relevant information and often forms the basis for treatment recommendations in this patient population.12 Indeed, in the wake of positive case reports, TNF-α inhibitors are now recommended for highly selected patients with refractory chronic psoriatic disease, including those with incapacitating joint pain.7,18

When TNF-α inhibitors are used in patients with HIV infection and psoriasis, optimal antiretroviral therapy and exceedingly close monitoring of clinical and laboratory parameters are of the utmost importance; Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis also is recommended in patients with low CD4 counts.7,18

In 2014, the oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor apremilast was approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and PsA. Recent case reports have described its successful use in patients with HIV infection and psoriasis, including the case reported herein, with no reports of opportunistic infections.4,19 Furthermore, HIV infection is not listed as a contraindication on its label.20

Apremilast is thought to increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate, thereby helping to attain improved homeostasis between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators.4,19 Several of the proinflammatory mediators that are indirectly targeted by apremilast, including TNF-α and IL-23, are explicitly inhibited by other biologics. It is this equilibrium between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators that most markedly differentiates apremilast from most other available biologic therapies for psoriasis, which typically have a specific proinflammatory target.4,21 As with other systemic therapies, close monitoring of CD4 levels and viral loads, as well as use of relevant prophylactic agents, is essential when apremilast is used in the setting of HIV infection, making coordination with infectious disease specialists essential.19

Bottom Line

Management of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection represents a clinical challenge. Case reports suggest a role for apremilast as an adjuvant to first-line therapy such as UV phototherapy in the setting of HIV infection in a patient with moderate to severe psoriasis, but close monitoring of CD4 count and viral load in these patients is needed in collaboration with infectious disease specialists. Updated guidelines on the use of systemic agents for psoriasis treatment in the HIV population are needed.

- Nakamura M, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, et al. Psoriasis treatment in HIV-positive patients: a systematic review of systemic immunosuppressive therapies. Cutis. 2018;101:38, 42, 56.

- Patel RV, Weinberg JM. Psoriasis in the patient with human immunodeficiency virus, part 2: review of treatment. Cutis. 2008;82:202-210.

- Ceccarelli M, Venanzi Rullo E, Vaccaro M, et al. HIV‐associated psoriasis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management [published online January 6, 2019]. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12806. doi:10.1111/dth.12806.

- Zarbafian M, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193.

- Menon K, Van Vorhees AS, Bebo, BF, et al. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299.

- Mallon E, Bunker CB. HIV-associated psoriasis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:239-246.

- Patel VA, Weinberg JM. Psoriasis in the patient with human immunodeficiency virus, part 1: review of pathogenesis. Cutis. 2008;82:117-122.

- Castillo RL, Racaza GZ, Dela Cruz Roa F. Ostraceous and inverse psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis as the presenting features of advanced HIV infection. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:e60-e63.

- Duvic M, Crane MM, Conant M, et al. Zidovudine improves psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus- positive males. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:447.

- Jaffee D, May LP, Sanchez M, et al. Staphylococcal sepsis in HIV antibody seropositive psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:970-972.

- King LE, Dufresne RG, Lovette GL, et al. Erythroderma: review of 82 cases. South Med J. 1986;79:1210-1215.

- Kaminetsky J, Aziz M, Kaushik S. A review of biologics and other treatment modalities in HIV-associated psoriasis. Skin. 2018;2:389-401.

- Wolff K. Side effects of psoralen photochemotherapy (PUVA). Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:117-125.

- Stern RS, Mills DK, Krell K, et al. HIV-positive patients differ from HIV-negative patients in indications for and type of UV therapy used. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:48-55.

- Oracion RM, Skiest DJ, Keiser PH, et al. HIV-related skin diseases. Prog Dermatol. 1999;33:1-6.

- Finkelstein M, Berman B. HIV and AIDS in inpatient dermatology: approach to the consultation. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:509-520.

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53.

- Sellam J, Bouvard B, Masson C, et al. Use of infliximab to treat psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:197-200.

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E1-E7.

- Otezla (apremilast). Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2017.

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590.

The treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection represents a clinical challenge.1,2 Up to 3% of patients with HIV infection are estimated to have psoriasis. Although this prevalence is similar to the general population, psoriatic disease in patients with HIV tends to be more severe, refractory, and more difficult to treat.3-5 Additionally, up to half of patients with comorbid HIV and psoriasis also have substantial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).1,6

Drug treatments for psoriasis and PsA often are immunosuppressive; as such, the treatment of psoriasis in this patient population requires careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits of treatment as well as fastidious monitoring for the emergence of potentially adverse treatment effects.1 A careful diagnostic process to determine the severity of HIV-associated psoriasis and to select the appropriate treatment relative to the patient’s immunologic status is of critical importance.3

Presentation of Psoriasis in Patients With HIV Infection

The presentation and severity of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection is highly variable and is often related to the degree of immune suppression experienced by the patient.3,7 In some individuals, psoriasis may be the first outward manifestation of HIV, whereas in others, it only manifests after HIV has progressed to AIDS.7

Recognition of the atypical presentations of psoriasis that are frequently seen in patients with HIV infection can help to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment to improve patient outcomes.3,8 Psoriasis vulgaris, for example, typically presents as erythematous plaques with silvery-white scales on extensor surfaces of the body such as the knees and elbows. However, in patients with HIV, psoriasis vulgaris may present with scales that appear thick and oyster shell–like instead of silvery-white; these lesions also may occur on flexural areas rather than extensor surfaces.8 Similarly, the sudden onset of widespread psoriasis in otherwise healthy persons should trigger suspicion for HIV infection and recommendations for appropriate testing, even when no risk factors are present.8

Guttate, inverse, and erythrodermic psoriasis are the most common subtypes in patients with HIV infection, though all clinical subtypes may occur. Overlapping of psoriasis subtypes often occurs in individuals with HIV infection and should serve as a red flag to recommend screening for HIV.5,8 Acral involvement, frequently with pustules and occasionally with severe destructive nail changes, is commonly seen in patients with HIV-associated psoriasis.7,9 In cases involving severe psoriatic exacerbations among individuals with AIDS, there is a heightened risk of developing systemic infections, including superinfection of Staphylococcus aureus, which is a rare occurrence in immunocompetent patients with psoriasis.7,10,11

Therapeutic Options

Because the clinical course of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection is frequently progressive and refractory to treatment, traditional first- and second-line therapies (Table) including topical agents, phototherapy, and oral retinoids may be unable to achieve lasting control of both skin and joint manifestations.1

Topical Therapy

As in the general population, targeted therapies such as topical agents are recommended as first-line treatment of mild HIV-associated psoriasis.12 Topical corticosteroids, calcipotriol, tazarotene, and formulations combining 2 of these medications form the cornerstone of topical therapies for mild psoriasis in patients with HIV infection. These agents have the advantage of possessing limited and localized effects, making it unlikely for them to increase immunosuppression in patients with HIV infection. They generally can be safely used in patients with HIV infection, and their side-effect profile in patients with HIV infection is similar to the general population.12 However, calcipotriol is the least desirable for use in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be a side effect of antiretroviral drugs.4

UV Phototherapy

Topical therapy is limited by its lack of potency; limited field coverage; and the inconvenience of application, particularly in patients with more widespread disease.12 Therefore, UV phototherapy is preferred as first-line treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. UV phototherapy has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and inflammation and result in clinical improvement of HIV-associated psoriasis; moreover, most of the reports in the literature support it as an option that will not increase immunocompromise in patients with HIV infection.12

Caution is warranted, however, regarding the immunomodulatory effects of UV therapies, which may result in an increased risk for skin cancer and diminished resistance to infection, which can be of particular concern in immunocompromised patients who are already at risk.7,13,14 In patients who are candidates for phototherapy, HIV serology and close monitoring of viral load and CD4 lymphocyte count before treatment, at monthly interludes throughout treatment, and 3 months following the cessation of treatment have been recommended.7,15 Careful consideration of the risk-benefit ratio of phototherapy for individual patients, including the patient’s stage of HIV disease, the degree of discomfort, disfigurement, and disability caused by the psoriasis (or other dermatologic condition), as well as the availability of alternative treatment options is essential.7,16

Systemic Agents

In patients who are intolerant of or unresponsive to antiretroviral therapy, topical therapies, and phototherapy, traditional systemic agents may be considered,12 including acitretin, methotrexate, and cyclosporine. However, updated guidelines indicate that methotrexate and cyclosporine should be avoided in this population given the risk for increased immunosuppression with these agents.4,17

Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, continue to be important options for second-line psoriasis treatment in patients with comorbid HIV infection, either as monotherapy or in association with phototherapy.3 Acitretin has the notable benefit of not causing or worsening immune compromise; however, its use is less than desirable in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be a side effect of antiretroviral drugs.4,12 Providers also must be aware of the possible association between acitretin (and other antiretrovirals) and pancreatitis, remaining vigilant in monitoring patients for this adverse effect.3

Biologics

The relatively recent addition of cytokine-suppressive biologic agents to the treatment armamentarium has transformed the management of psoriasis in otherwise healthy individuals. These agents have been shown to possess an excellent safety and efficacy profile.12 However, their use in patients with HIV infection has been mired in concerns regarding a potential increase in the risk for opportunistic infections, sepsis, and HIV disease progression in this patient population.7,12

Case reports have detailed the safe treatment of recalcitrant HIV-associated psoriasis with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, such as etanercept.7,12 In most of these case reports, no harm to CD4 lymphocyte counts, serum viral loads, overall immune status, and susceptibility to infection have been noted; on the contrary, CD4 count increased in most patients following treatment with biologic agents.12 Because patients with HIV infection tend to be excluded from clinical trials, anecdotal evidence derived from case reports and case series often provides clinically relevant information and often forms the basis for treatment recommendations in this patient population.12 Indeed, in the wake of positive case reports, TNF-α inhibitors are now recommended for highly selected patients with refractory chronic psoriatic disease, including those with incapacitating joint pain.7,18

When TNF-α inhibitors are used in patients with HIV infection and psoriasis, optimal antiretroviral therapy and exceedingly close monitoring of clinical and laboratory parameters are of the utmost importance; Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis also is recommended in patients with low CD4 counts.7,18

In 2014, the oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor apremilast was approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and PsA. Recent case reports have described its successful use in patients with HIV infection and psoriasis, including the case reported herein, with no reports of opportunistic infections.4,19 Furthermore, HIV infection is not listed as a contraindication on its label.20

Apremilast is thought to increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate, thereby helping to attain improved homeostasis between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators.4,19 Several of the proinflammatory mediators that are indirectly targeted by apremilast, including TNF-α and IL-23, are explicitly inhibited by other biologics. It is this equilibrium between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators that most markedly differentiates apremilast from most other available biologic therapies for psoriasis, which typically have a specific proinflammatory target.4,21 As with other systemic therapies, close monitoring of CD4 levels and viral loads, as well as use of relevant prophylactic agents, is essential when apremilast is used in the setting of HIV infection, making coordination with infectious disease specialists essential.19

Bottom Line

Management of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection represents a clinical challenge. Case reports suggest a role for apremilast as an adjuvant to first-line therapy such as UV phototherapy in the setting of HIV infection in a patient with moderate to severe psoriasis, but close monitoring of CD4 count and viral load in these patients is needed in collaboration with infectious disease specialists. Updated guidelines on the use of systemic agents for psoriasis treatment in the HIV population are needed.

The treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection represents a clinical challenge.1,2 Up to 3% of patients with HIV infection are estimated to have psoriasis. Although this prevalence is similar to the general population, psoriatic disease in patients with HIV tends to be more severe, refractory, and more difficult to treat.3-5 Additionally, up to half of patients with comorbid HIV and psoriasis also have substantial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).1,6

Drug treatments for psoriasis and PsA often are immunosuppressive; as such, the treatment of psoriasis in this patient population requires careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits of treatment as well as fastidious monitoring for the emergence of potentially adverse treatment effects.1 A careful diagnostic process to determine the severity of HIV-associated psoriasis and to select the appropriate treatment relative to the patient’s immunologic status is of critical importance.3

Presentation of Psoriasis in Patients With HIV Infection

The presentation and severity of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection is highly variable and is often related to the degree of immune suppression experienced by the patient.3,7 In some individuals, psoriasis may be the first outward manifestation of HIV, whereas in others, it only manifests after HIV has progressed to AIDS.7

Recognition of the atypical presentations of psoriasis that are frequently seen in patients with HIV infection can help to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment to improve patient outcomes.3,8 Psoriasis vulgaris, for example, typically presents as erythematous plaques with silvery-white scales on extensor surfaces of the body such as the knees and elbows. However, in patients with HIV, psoriasis vulgaris may present with scales that appear thick and oyster shell–like instead of silvery-white; these lesions also may occur on flexural areas rather than extensor surfaces.8 Similarly, the sudden onset of widespread psoriasis in otherwise healthy persons should trigger suspicion for HIV infection and recommendations for appropriate testing, even when no risk factors are present.8

Guttate, inverse, and erythrodermic psoriasis are the most common subtypes in patients with HIV infection, though all clinical subtypes may occur. Overlapping of psoriasis subtypes often occurs in individuals with HIV infection and should serve as a red flag to recommend screening for HIV.5,8 Acral involvement, frequently with pustules and occasionally with severe destructive nail changes, is commonly seen in patients with HIV-associated psoriasis.7,9 In cases involving severe psoriatic exacerbations among individuals with AIDS, there is a heightened risk of developing systemic infections, including superinfection of Staphylococcus aureus, which is a rare occurrence in immunocompetent patients with psoriasis.7,10,11

Therapeutic Options

Because the clinical course of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection is frequently progressive and refractory to treatment, traditional first- and second-line therapies (Table) including topical agents, phototherapy, and oral retinoids may be unable to achieve lasting control of both skin and joint manifestations.1

Topical Therapy

As in the general population, targeted therapies such as topical agents are recommended as first-line treatment of mild HIV-associated psoriasis.12 Topical corticosteroids, calcipotriol, tazarotene, and formulations combining 2 of these medications form the cornerstone of topical therapies for mild psoriasis in patients with HIV infection. These agents have the advantage of possessing limited and localized effects, making it unlikely for them to increase immunosuppression in patients with HIV infection. They generally can be safely used in patients with HIV infection, and their side-effect profile in patients with HIV infection is similar to the general population.12 However, calcipotriol is the least desirable for use in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be a side effect of antiretroviral drugs.4

UV Phototherapy

Topical therapy is limited by its lack of potency; limited field coverage; and the inconvenience of application, particularly in patients with more widespread disease.12 Therefore, UV phototherapy is preferred as first-line treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. UV phototherapy has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and inflammation and result in clinical improvement of HIV-associated psoriasis; moreover, most of the reports in the literature support it as an option that will not increase immunocompromise in patients with HIV infection.12

Caution is warranted, however, regarding the immunomodulatory effects of UV therapies, which may result in an increased risk for skin cancer and diminished resistance to infection, which can be of particular concern in immunocompromised patients who are already at risk.7,13,14 In patients who are candidates for phototherapy, HIV serology and close monitoring of viral load and CD4 lymphocyte count before treatment, at monthly interludes throughout treatment, and 3 months following the cessation of treatment have been recommended.7,15 Careful consideration of the risk-benefit ratio of phototherapy for individual patients, including the patient’s stage of HIV disease, the degree of discomfort, disfigurement, and disability caused by the psoriasis (or other dermatologic condition), as well as the availability of alternative treatment options is essential.7,16

Systemic Agents

In patients who are intolerant of or unresponsive to antiretroviral therapy, topical therapies, and phototherapy, traditional systemic agents may be considered,12 including acitretin, methotrexate, and cyclosporine. However, updated guidelines indicate that methotrexate and cyclosporine should be avoided in this population given the risk for increased immunosuppression with these agents.4,17

Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, continue to be important options for second-line psoriasis treatment in patients with comorbid HIV infection, either as monotherapy or in association with phototherapy.3 Acitretin has the notable benefit of not causing or worsening immune compromise; however, its use is less than desirable in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be a side effect of antiretroviral drugs.4,12 Providers also must be aware of the possible association between acitretin (and other antiretrovirals) and pancreatitis, remaining vigilant in monitoring patients for this adverse effect.3

Biologics

The relatively recent addition of cytokine-suppressive biologic agents to the treatment armamentarium has transformed the management of psoriasis in otherwise healthy individuals. These agents have been shown to possess an excellent safety and efficacy profile.12 However, their use in patients with HIV infection has been mired in concerns regarding a potential increase in the risk for opportunistic infections, sepsis, and HIV disease progression in this patient population.7,12

Case reports have detailed the safe treatment of recalcitrant HIV-associated psoriasis with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, such as etanercept.7,12 In most of these case reports, no harm to CD4 lymphocyte counts, serum viral loads, overall immune status, and susceptibility to infection have been noted; on the contrary, CD4 count increased in most patients following treatment with biologic agents.12 Because patients with HIV infection tend to be excluded from clinical trials, anecdotal evidence derived from case reports and case series often provides clinically relevant information and often forms the basis for treatment recommendations in this patient population.12 Indeed, in the wake of positive case reports, TNF-α inhibitors are now recommended for highly selected patients with refractory chronic psoriatic disease, including those with incapacitating joint pain.7,18

When TNF-α inhibitors are used in patients with HIV infection and psoriasis, optimal antiretroviral therapy and exceedingly close monitoring of clinical and laboratory parameters are of the utmost importance; Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis also is recommended in patients with low CD4 counts.7,18

In 2014, the oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor apremilast was approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and PsA. Recent case reports have described its successful use in patients with HIV infection and psoriasis, including the case reported herein, with no reports of opportunistic infections.4,19 Furthermore, HIV infection is not listed as a contraindication on its label.20

Apremilast is thought to increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate, thereby helping to attain improved homeostasis between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators.4,19 Several of the proinflammatory mediators that are indirectly targeted by apremilast, including TNF-α and IL-23, are explicitly inhibited by other biologics. It is this equilibrium between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators that most markedly differentiates apremilast from most other available biologic therapies for psoriasis, which typically have a specific proinflammatory target.4,21 As with other systemic therapies, close monitoring of CD4 levels and viral loads, as well as use of relevant prophylactic agents, is essential when apremilast is used in the setting of HIV infection, making coordination with infectious disease specialists essential.19

Bottom Line

Management of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection represents a clinical challenge. Case reports suggest a role for apremilast as an adjuvant to first-line therapy such as UV phototherapy in the setting of HIV infection in a patient with moderate to severe psoriasis, but close monitoring of CD4 count and viral load in these patients is needed in collaboration with infectious disease specialists. Updated guidelines on the use of systemic agents for psoriasis treatment in the HIV population are needed.

- Nakamura M, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, et al. Psoriasis treatment in HIV-positive patients: a systematic review of systemic immunosuppressive therapies. Cutis. 2018;101:38, 42, 56.

- Patel RV, Weinberg JM. Psoriasis in the patient with human immunodeficiency virus, part 2: review of treatment. Cutis. 2008;82:202-210.

- Ceccarelli M, Venanzi Rullo E, Vaccaro M, et al. HIV‐associated psoriasis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management [published online January 6, 2019]. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12806. doi:10.1111/dth.12806.

- Zarbafian M, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193.

- Menon K, Van Vorhees AS, Bebo, BF, et al. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299.

- Mallon E, Bunker CB. HIV-associated psoriasis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:239-246.

- Patel VA, Weinberg JM. Psoriasis in the patient with human immunodeficiency virus, part 1: review of pathogenesis. Cutis. 2008;82:117-122.

- Castillo RL, Racaza GZ, Dela Cruz Roa F. Ostraceous and inverse psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis as the presenting features of advanced HIV infection. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:e60-e63.

- Duvic M, Crane MM, Conant M, et al. Zidovudine improves psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus- positive males. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:447.

- Jaffee D, May LP, Sanchez M, et al. Staphylococcal sepsis in HIV antibody seropositive psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:970-972.

- King LE, Dufresne RG, Lovette GL, et al. Erythroderma: review of 82 cases. South Med J. 1986;79:1210-1215.

- Kaminetsky J, Aziz M, Kaushik S. A review of biologics and other treatment modalities in HIV-associated psoriasis. Skin. 2018;2:389-401.

- Wolff K. Side effects of psoralen photochemotherapy (PUVA). Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:117-125.

- Stern RS, Mills DK, Krell K, et al. HIV-positive patients differ from HIV-negative patients in indications for and type of UV therapy used. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:48-55.

- Oracion RM, Skiest DJ, Keiser PH, et al. HIV-related skin diseases. Prog Dermatol. 1999;33:1-6.

- Finkelstein M, Berman B. HIV and AIDS in inpatient dermatology: approach to the consultation. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:509-520.

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53.

- Sellam J, Bouvard B, Masson C, et al. Use of infliximab to treat psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:197-200.

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E1-E7.

- Otezla (apremilast). Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2017.

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590.

- Nakamura M, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, et al. Psoriasis treatment in HIV-positive patients: a systematic review of systemic immunosuppressive therapies. Cutis. 2018;101:38, 42, 56.

- Patel RV, Weinberg JM. Psoriasis in the patient with human immunodeficiency virus, part 2: review of treatment. Cutis. 2008;82:202-210.

- Ceccarelli M, Venanzi Rullo E, Vaccaro M, et al. HIV‐associated psoriasis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management [published online January 6, 2019]. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12806. doi:10.1111/dth.12806.

- Zarbafian M, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193.

- Menon K, Van Vorhees AS, Bebo, BF, et al. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299.

- Mallon E, Bunker CB. HIV-associated psoriasis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:239-246.

- Patel VA, Weinberg JM. Psoriasis in the patient with human immunodeficiency virus, part 1: review of pathogenesis. Cutis. 2008;82:117-122.

- Castillo RL, Racaza GZ, Dela Cruz Roa F. Ostraceous and inverse psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis as the presenting features of advanced HIV infection. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:e60-e63.

- Duvic M, Crane MM, Conant M, et al. Zidovudine improves psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus- positive males. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:447.

- Jaffee D, May LP, Sanchez M, et al. Staphylococcal sepsis in HIV antibody seropositive psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:970-972.

- King LE, Dufresne RG, Lovette GL, et al. Erythroderma: review of 82 cases. South Med J. 1986;79:1210-1215.

- Kaminetsky J, Aziz M, Kaushik S. A review of biologics and other treatment modalities in HIV-associated psoriasis. Skin. 2018;2:389-401.

- Wolff K. Side effects of psoralen photochemotherapy (PUVA). Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:117-125.

- Stern RS, Mills DK, Krell K, et al. HIV-positive patients differ from HIV-negative patients in indications for and type of UV therapy used. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:48-55.

- Oracion RM, Skiest DJ, Keiser PH, et al. HIV-related skin diseases. Prog Dermatol. 1999;33:1-6.

- Finkelstein M, Berman B. HIV and AIDS in inpatient dermatology: approach to the consultation. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:509-520.

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53.

- Sellam J, Bouvard B, Masson C, et al. Use of infliximab to treat psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:197-200.

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E1-E7.

- Otezla (apremilast). Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2017.

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590.

A 50-year-old man with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented with persistent psoriatic lesions on the trunk, arms, legs, and buttocks. The patient’s medical history was positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), fatty liver disease, and moderate psoriasis (10% body surface area [BSA] affected), for which clobetasol spray and calcitriol ointment had been prescribed. The patient’s CD4 count was 460 at presentation, and his HIV RNA count was 48 copies/mL on polymerase chain reaction 2 months prior to presentation. For the last 5 months, the patient had been undergoing phototherapy 3 times weekly for treatment of psoriasis.

An apremilast starter pack was initiated with the dosage titrated from 10 mg to 30 mg over the course of 1 week. The patient was maintained on a dose of 30 mg twice daily after 1 week, while continuing clobetasol spray, calcitriol ointment, and phototherapy 3 times weekly with the intent to reduce the frequency after adequate control of psoriasis was achieved. After 3 months of treatment, the patient’s affected BSA was 0%. Apremilast was continued, and phototherapy was reduced to once weekly. After 7 months of concomitant treatment with apremilast, phototherapy was discontinued after clearance was maintained. Phototherapy was reinitiated twice weekly after a mild flare (3% BSA affected).

The patient continued apremilast for a total of 20 months until it became cost prohibitive. After discontinuing apremilast for 4 months, he presented with a severe psoriasis flare (40% BSA affected). He was switched to acitretin with intention to apply for an apremilast financial assistance program.