User login

Not too long ago at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston, a woman with widely metastatic melanoma, who had been planning her own funeral, was surprised when she had a phenomenal response to immunotherapy.

She was shocked to learn that her cancer was almost completely gone after 12 weeks, but she was stunned when she developed a rash that made her oncologist think she needed to stop treatment.

With traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies, there were a few well-defined skin side effects that oncologists were comfortable managing on their own with steroids or by reducing or stopping treatment for a bit.

But over the last decade, new cancer options have become available, most notably immunotherapies and targeted biologics, which are keeping some people alive longer but also causing cutaneous side effects that have never been seen before in oncology and are being reported frequently.

An urgent need

Currently in the United States, there’s only a handful of dedicated supportive oncodermatology services, which can be found at major academic cancer centers such as Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s, but the residents and fellows being trained at these centers are starting to fan out across the country and set up new services.

One day, it’s likely that every major cancer institution will have “a toxicities team with expert dermatologists,” said Dr. LeBoeuf, who launched the supportive oncodermatology program at Dana-Farber in 2014 and who now runs it with a team of dermatologists and clinics every week. Dr. LeBoeuf is a leader in the field, like the other dermatologists interviewed for this story.

With all the new treatments and with even more on the way, “there’s an urgent need for dermatologists to be involved in care of cancer patients,” Dr. LeBoeuf said.

The problem

Immunotherapies like the PD-1 blocking agents pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) – both used for an ever-expanding list of tumors – amp up the immune system to fight cancer, but they also tend to cause adverse events that mimic autoimmune diseases such as lupus, psoriasis, lichen planus, and vitiligo. Dermatologists are familiar with those problems and how to manage them, but oncologists generally are not.

Meanwhile, the many targeted therapies approved over the past decade interfere with specific molecules needed for tumor growth, but they also are associated with a wide range of skin, hair, and nail side effects that include skin growths, itching, paronychia, and more.

Agents that target vascular endothelial growth factors, such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and bevacizumab (Avastin), can trigger a painful hand-foot skin reaction that’s different from the hand-foot syndrome reported with older cytotoxic agents.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, such as erlotinib (Tarceva) or gefitinib (Iressa), often cause miserable acne-like eruptions, but that can mean the drug is working.

It’s hard for oncologists to know what’s life-threatening and what isn’t; that’s where dermatologists come in.

A solution

When problems come up, oncologists and patients need answers right away, she said. There’s no time to wait a month or two for a dermatology appointment to find out whether, for instance, a new mouth ulcer is a minor inconvenience or the first sign of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and the last thing an exhausted cancer patient needs is to be told to go to yet another clinic for a dermatology consult.

For supportive oncodermatology, that means being where the patients are: in the cancer centers. “Our clinic is situated on the same cancer floor as all the other oncology clinics,” which means easy access for both patients and oncologists, Dr. Choi said. “They just come down the hall.”

Build it, and they will come

The Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Center is a good example of what happens once a supportive oncodermatology service is up and running.

The program there was the brainchild of dermatologist Bernice Kwong, MD, who helped launch it in 2012 with 2 half-day outpatient clinics per week.

“Once people knew we were there seeing patients, we needed to expand it to 3 half days, and within 6 months, we knew we had to be” in the cancer center daily, she said. “The oncologists felt we were helping them keep their patients on treatment longer; they didn’t have to stop therapy to sort out a rash.”

Currently, the clinic sees about 15 to 20 patients a day, but “we have more need than that,” said Dr. Kwong, who is trying to recruit more dermatologists to help.

“The need is huge. There’s so much room for growth,” she noted, but first, “you need the oncologists to be on board.”

Dermatologist Adam Friedman, MD, director of supportive oncodermatology at the George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington, says his program is on the other end of the growth curve since it was only launched in the spring of 2017. Only about 80 patients have been treated so far, and there’s one dedicated clinic day a month, although he is on call for urgent cases, as is the case for many of the other dermatologists interviewed for this story.

Dr. Friedman expects business will pick up soon once word gets out, just like at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s, Stanford, and elsewhere. “The places with the greatest need are going to have these services first, and then you’ll see them pop up elsewhere. I think we are going to see more,” he said.

The birth of supportive oncodermatology

Dermatologist Mario Lacouture, MD, director of the oncodermatology program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, is considered by many oncodermatologists to be the father of the field.

He started the very first program in 2005 at Northwestern University, Chicago, followed by the program at Sloan Kettering a few years later. He has helped train many of the leaders in the field and coined the phrase “supportive oncodermatology” as the senior author in the field’s seminal paper, published in 2011 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Sep;65[3]:624-35). That article, in turn, inspired at least a few young dermatologists to make supportive oncodermatology their career choice. Dr. Lacouture speaks regularly at oncology and dermatology meetings to raise awareness about how dermatologists can improve cancer care.

Cancer survivors were also a concern. “Cancer treatment has improved so much that people are living longer, but the majority of survivors have either temporary or permanent cutaneous problems that would benefit from dermatologic care. However, the oncology community and patients are usually not aware that there are things we can do to help,” Dr. Lacouture said.

The message seems to have gotten out, however, among the hundreds of oncologists affiliated with Sloan Kettering. Dr. Lacouture needs a team of supportive oncodermatologists to meet the demand, with walk-in clinics every day and round-the-clock call.

He anticipates a day when visiting a supportive oncodermatologist will be routine, even before the start of cancer treatment, just as people visit a dentist before bone marrow transplants or radiation treatment to the head and neck. The idea would be to prevent cutaneous toxicity, something Dr. Lacouture and his team are already doing at Sloan Kettering. In time, supportive oncodermatology “is something that is going to be instituted early on” in treatment, he said.

“It’s important for dermatologists to reach out to their local oncologists; they will see there are many, many cancer patients and survivors who would benefit immensely from their care,” he said.

Dr. Lacouture is a consultant for Galderma, Janssen, and Johnson & Johnson. The other dermatologists interviewed for this story had no relevant industry disclosures. La Roche-Posay, a subsidiary of L’Oreal, is helping fund the supportive oncodermatology program at George Washington University. The company is interested in using cosmetics to camouflage cancer treatment skin lesions, Dr. Friedman said. Dr. Friedman is a member of the Dermatology News advisory board.

aotto@frontlinemedcom.com

Not too long ago at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston, a woman with widely metastatic melanoma, who had been planning her own funeral, was surprised when she had a phenomenal response to immunotherapy.

She was shocked to learn that her cancer was almost completely gone after 12 weeks, but she was stunned when she developed a rash that made her oncologist think she needed to stop treatment.

With traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies, there were a few well-defined skin side effects that oncologists were comfortable managing on their own with steroids or by reducing or stopping treatment for a bit.

But over the last decade, new cancer options have become available, most notably immunotherapies and targeted biologics, which are keeping some people alive longer but also causing cutaneous side effects that have never been seen before in oncology and are being reported frequently.

An urgent need

Currently in the United States, there’s only a handful of dedicated supportive oncodermatology services, which can be found at major academic cancer centers such as Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s, but the residents and fellows being trained at these centers are starting to fan out across the country and set up new services.

One day, it’s likely that every major cancer institution will have “a toxicities team with expert dermatologists,” said Dr. LeBoeuf, who launched the supportive oncodermatology program at Dana-Farber in 2014 and who now runs it with a team of dermatologists and clinics every week. Dr. LeBoeuf is a leader in the field, like the other dermatologists interviewed for this story.

With all the new treatments and with even more on the way, “there’s an urgent need for dermatologists to be involved in care of cancer patients,” Dr. LeBoeuf said.

The problem

Immunotherapies like the PD-1 blocking agents pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) – both used for an ever-expanding list of tumors – amp up the immune system to fight cancer, but they also tend to cause adverse events that mimic autoimmune diseases such as lupus, psoriasis, lichen planus, and vitiligo. Dermatologists are familiar with those problems and how to manage them, but oncologists generally are not.

Meanwhile, the many targeted therapies approved over the past decade interfere with specific molecules needed for tumor growth, but they also are associated with a wide range of skin, hair, and nail side effects that include skin growths, itching, paronychia, and more.

Agents that target vascular endothelial growth factors, such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and bevacizumab (Avastin), can trigger a painful hand-foot skin reaction that’s different from the hand-foot syndrome reported with older cytotoxic agents.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, such as erlotinib (Tarceva) or gefitinib (Iressa), often cause miserable acne-like eruptions, but that can mean the drug is working.

It’s hard for oncologists to know what’s life-threatening and what isn’t; that’s where dermatologists come in.

A solution

When problems come up, oncologists and patients need answers right away, she said. There’s no time to wait a month or two for a dermatology appointment to find out whether, for instance, a new mouth ulcer is a minor inconvenience or the first sign of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and the last thing an exhausted cancer patient needs is to be told to go to yet another clinic for a dermatology consult.

For supportive oncodermatology, that means being where the patients are: in the cancer centers. “Our clinic is situated on the same cancer floor as all the other oncology clinics,” which means easy access for both patients and oncologists, Dr. Choi said. “They just come down the hall.”

Build it, and they will come

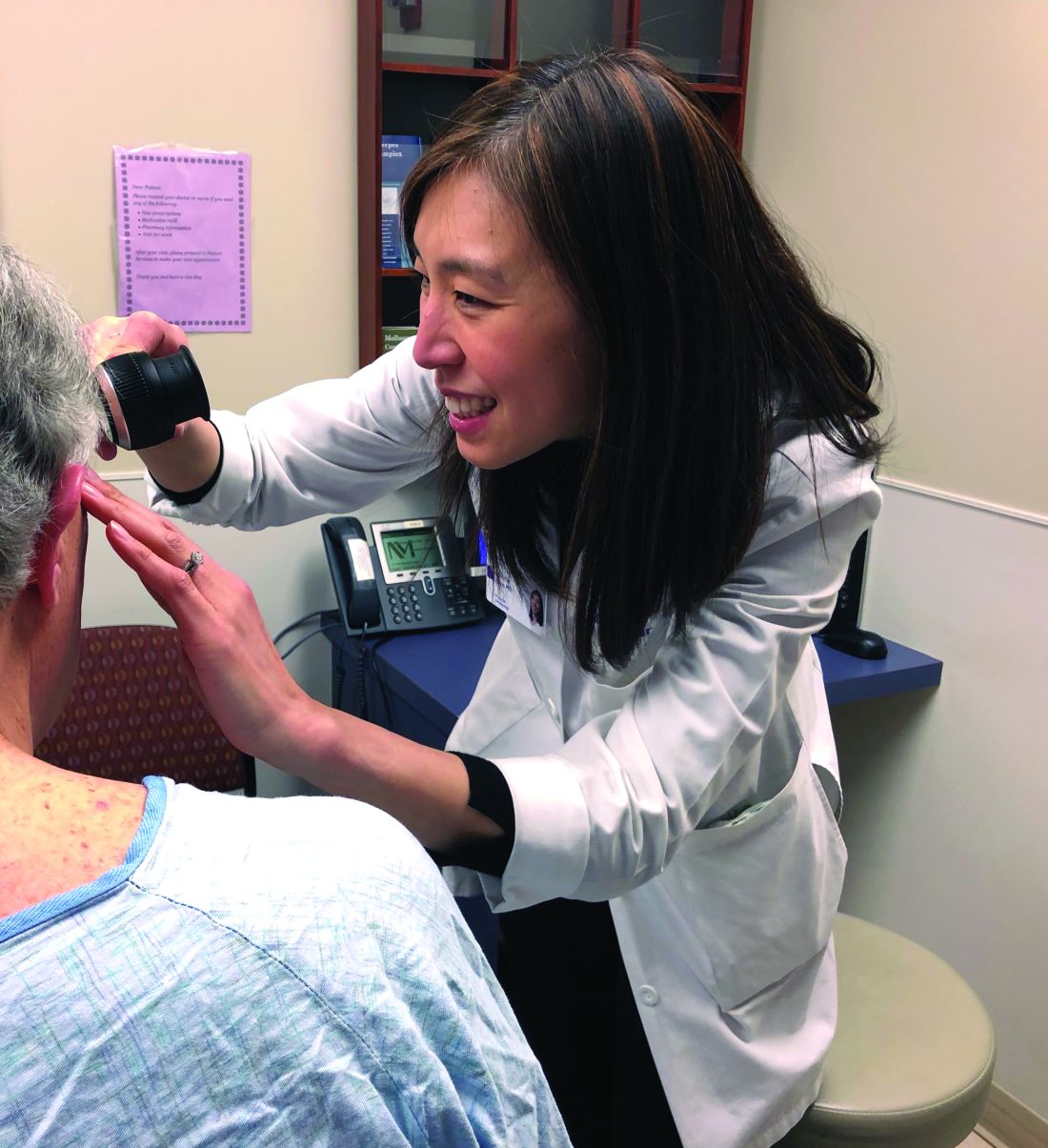

The Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Center is a good example of what happens once a supportive oncodermatology service is up and running.

The program there was the brainchild of dermatologist Bernice Kwong, MD, who helped launch it in 2012 with 2 half-day outpatient clinics per week.

“Once people knew we were there seeing patients, we needed to expand it to 3 half days, and within 6 months, we knew we had to be” in the cancer center daily, she said. “The oncologists felt we were helping them keep their patients on treatment longer; they didn’t have to stop therapy to sort out a rash.”

Currently, the clinic sees about 15 to 20 patients a day, but “we have more need than that,” said Dr. Kwong, who is trying to recruit more dermatologists to help.

“The need is huge. There’s so much room for growth,” she noted, but first, “you need the oncologists to be on board.”

Dermatologist Adam Friedman, MD, director of supportive oncodermatology at the George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington, says his program is on the other end of the growth curve since it was only launched in the spring of 2017. Only about 80 patients have been treated so far, and there’s one dedicated clinic day a month, although he is on call for urgent cases, as is the case for many of the other dermatologists interviewed for this story.

Dr. Friedman expects business will pick up soon once word gets out, just like at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s, Stanford, and elsewhere. “The places with the greatest need are going to have these services first, and then you’ll see them pop up elsewhere. I think we are going to see more,” he said.

The birth of supportive oncodermatology

Dermatologist Mario Lacouture, MD, director of the oncodermatology program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, is considered by many oncodermatologists to be the father of the field.

He started the very first program in 2005 at Northwestern University, Chicago, followed by the program at Sloan Kettering a few years later. He has helped train many of the leaders in the field and coined the phrase “supportive oncodermatology” as the senior author in the field’s seminal paper, published in 2011 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Sep;65[3]:624-35). That article, in turn, inspired at least a few young dermatologists to make supportive oncodermatology their career choice. Dr. Lacouture speaks regularly at oncology and dermatology meetings to raise awareness about how dermatologists can improve cancer care.

Cancer survivors were also a concern. “Cancer treatment has improved so much that people are living longer, but the majority of survivors have either temporary or permanent cutaneous problems that would benefit from dermatologic care. However, the oncology community and patients are usually not aware that there are things we can do to help,” Dr. Lacouture said.

The message seems to have gotten out, however, among the hundreds of oncologists affiliated with Sloan Kettering. Dr. Lacouture needs a team of supportive oncodermatologists to meet the demand, with walk-in clinics every day and round-the-clock call.

He anticipates a day when visiting a supportive oncodermatologist will be routine, even before the start of cancer treatment, just as people visit a dentist before bone marrow transplants or radiation treatment to the head and neck. The idea would be to prevent cutaneous toxicity, something Dr. Lacouture and his team are already doing at Sloan Kettering. In time, supportive oncodermatology “is something that is going to be instituted early on” in treatment, he said.

“It’s important for dermatologists to reach out to their local oncologists; they will see there are many, many cancer patients and survivors who would benefit immensely from their care,” he said.

Dr. Lacouture is a consultant for Galderma, Janssen, and Johnson & Johnson. The other dermatologists interviewed for this story had no relevant industry disclosures. La Roche-Posay, a subsidiary of L’Oreal, is helping fund the supportive oncodermatology program at George Washington University. The company is interested in using cosmetics to camouflage cancer treatment skin lesions, Dr. Friedman said. Dr. Friedman is a member of the Dermatology News advisory board.

aotto@frontlinemedcom.com

Not too long ago at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston, a woman with widely metastatic melanoma, who had been planning her own funeral, was surprised when she had a phenomenal response to immunotherapy.

She was shocked to learn that her cancer was almost completely gone after 12 weeks, but she was stunned when she developed a rash that made her oncologist think she needed to stop treatment.

With traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies, there were a few well-defined skin side effects that oncologists were comfortable managing on their own with steroids or by reducing or stopping treatment for a bit.

But over the last decade, new cancer options have become available, most notably immunotherapies and targeted biologics, which are keeping some people alive longer but also causing cutaneous side effects that have never been seen before in oncology and are being reported frequently.

An urgent need

Currently in the United States, there’s only a handful of dedicated supportive oncodermatology services, which can be found at major academic cancer centers such as Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s, but the residents and fellows being trained at these centers are starting to fan out across the country and set up new services.

One day, it’s likely that every major cancer institution will have “a toxicities team with expert dermatologists,” said Dr. LeBoeuf, who launched the supportive oncodermatology program at Dana-Farber in 2014 and who now runs it with a team of dermatologists and clinics every week. Dr. LeBoeuf is a leader in the field, like the other dermatologists interviewed for this story.

With all the new treatments and with even more on the way, “there’s an urgent need for dermatologists to be involved in care of cancer patients,” Dr. LeBoeuf said.

The problem

Immunotherapies like the PD-1 blocking agents pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) – both used for an ever-expanding list of tumors – amp up the immune system to fight cancer, but they also tend to cause adverse events that mimic autoimmune diseases such as lupus, psoriasis, lichen planus, and vitiligo. Dermatologists are familiar with those problems and how to manage them, but oncologists generally are not.

Meanwhile, the many targeted therapies approved over the past decade interfere with specific molecules needed for tumor growth, but they also are associated with a wide range of skin, hair, and nail side effects that include skin growths, itching, paronychia, and more.

Agents that target vascular endothelial growth factors, such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and bevacizumab (Avastin), can trigger a painful hand-foot skin reaction that’s different from the hand-foot syndrome reported with older cytotoxic agents.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, such as erlotinib (Tarceva) or gefitinib (Iressa), often cause miserable acne-like eruptions, but that can mean the drug is working.

It’s hard for oncologists to know what’s life-threatening and what isn’t; that’s where dermatologists come in.

A solution

When problems come up, oncologists and patients need answers right away, she said. There’s no time to wait a month or two for a dermatology appointment to find out whether, for instance, a new mouth ulcer is a minor inconvenience or the first sign of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and the last thing an exhausted cancer patient needs is to be told to go to yet another clinic for a dermatology consult.

For supportive oncodermatology, that means being where the patients are: in the cancer centers. “Our clinic is situated on the same cancer floor as all the other oncology clinics,” which means easy access for both patients and oncologists, Dr. Choi said. “They just come down the hall.”

Build it, and they will come

The Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Center is a good example of what happens once a supportive oncodermatology service is up and running.

The program there was the brainchild of dermatologist Bernice Kwong, MD, who helped launch it in 2012 with 2 half-day outpatient clinics per week.

“Once people knew we were there seeing patients, we needed to expand it to 3 half days, and within 6 months, we knew we had to be” in the cancer center daily, she said. “The oncologists felt we were helping them keep their patients on treatment longer; they didn’t have to stop therapy to sort out a rash.”

Currently, the clinic sees about 15 to 20 patients a day, but “we have more need than that,” said Dr. Kwong, who is trying to recruit more dermatologists to help.

“The need is huge. There’s so much room for growth,” she noted, but first, “you need the oncologists to be on board.”

Dermatologist Adam Friedman, MD, director of supportive oncodermatology at the George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington, says his program is on the other end of the growth curve since it was only launched in the spring of 2017. Only about 80 patients have been treated so far, and there’s one dedicated clinic day a month, although he is on call for urgent cases, as is the case for many of the other dermatologists interviewed for this story.

Dr. Friedman expects business will pick up soon once word gets out, just like at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s, Stanford, and elsewhere. “The places with the greatest need are going to have these services first, and then you’ll see them pop up elsewhere. I think we are going to see more,” he said.

The birth of supportive oncodermatology

Dermatologist Mario Lacouture, MD, director of the oncodermatology program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, is considered by many oncodermatologists to be the father of the field.

He started the very first program in 2005 at Northwestern University, Chicago, followed by the program at Sloan Kettering a few years later. He has helped train many of the leaders in the field and coined the phrase “supportive oncodermatology” as the senior author in the field’s seminal paper, published in 2011 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Sep;65[3]:624-35). That article, in turn, inspired at least a few young dermatologists to make supportive oncodermatology their career choice. Dr. Lacouture speaks regularly at oncology and dermatology meetings to raise awareness about how dermatologists can improve cancer care.

Cancer survivors were also a concern. “Cancer treatment has improved so much that people are living longer, but the majority of survivors have either temporary or permanent cutaneous problems that would benefit from dermatologic care. However, the oncology community and patients are usually not aware that there are things we can do to help,” Dr. Lacouture said.

The message seems to have gotten out, however, among the hundreds of oncologists affiliated with Sloan Kettering. Dr. Lacouture needs a team of supportive oncodermatologists to meet the demand, with walk-in clinics every day and round-the-clock call.

He anticipates a day when visiting a supportive oncodermatologist will be routine, even before the start of cancer treatment, just as people visit a dentist before bone marrow transplants or radiation treatment to the head and neck. The idea would be to prevent cutaneous toxicity, something Dr. Lacouture and his team are already doing at Sloan Kettering. In time, supportive oncodermatology “is something that is going to be instituted early on” in treatment, he said.

“It’s important for dermatologists to reach out to their local oncologists; they will see there are many, many cancer patients and survivors who would benefit immensely from their care,” he said.

Dr. Lacouture is a consultant for Galderma, Janssen, and Johnson & Johnson. The other dermatologists interviewed for this story had no relevant industry disclosures. La Roche-Posay, a subsidiary of L’Oreal, is helping fund the supportive oncodermatology program at George Washington University. The company is interested in using cosmetics to camouflage cancer treatment skin lesions, Dr. Friedman said. Dr. Friedman is a member of the Dermatology News advisory board.

aotto@frontlinemedcom.com