User login

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

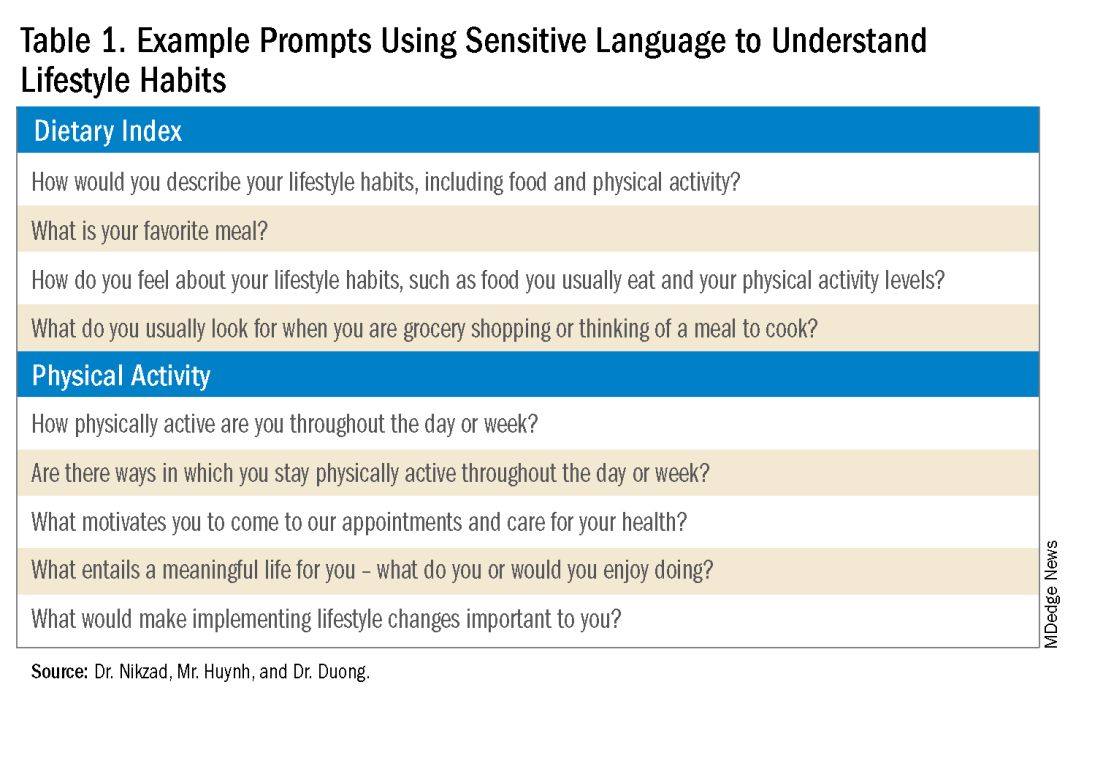

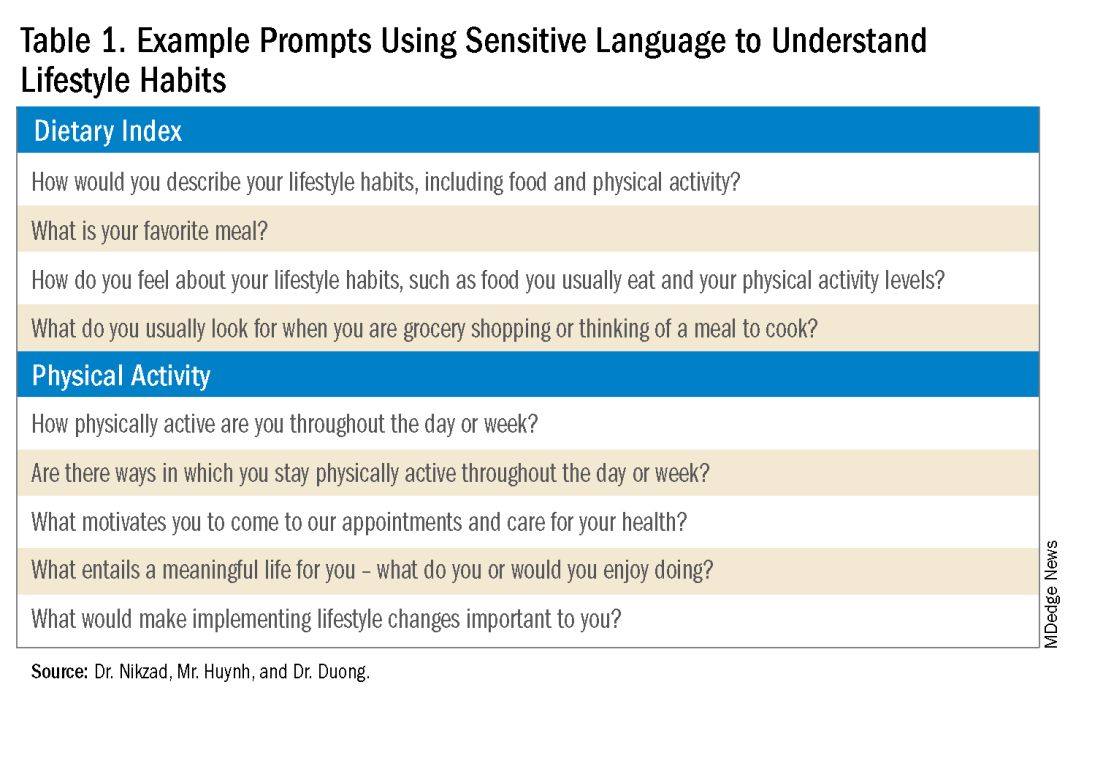

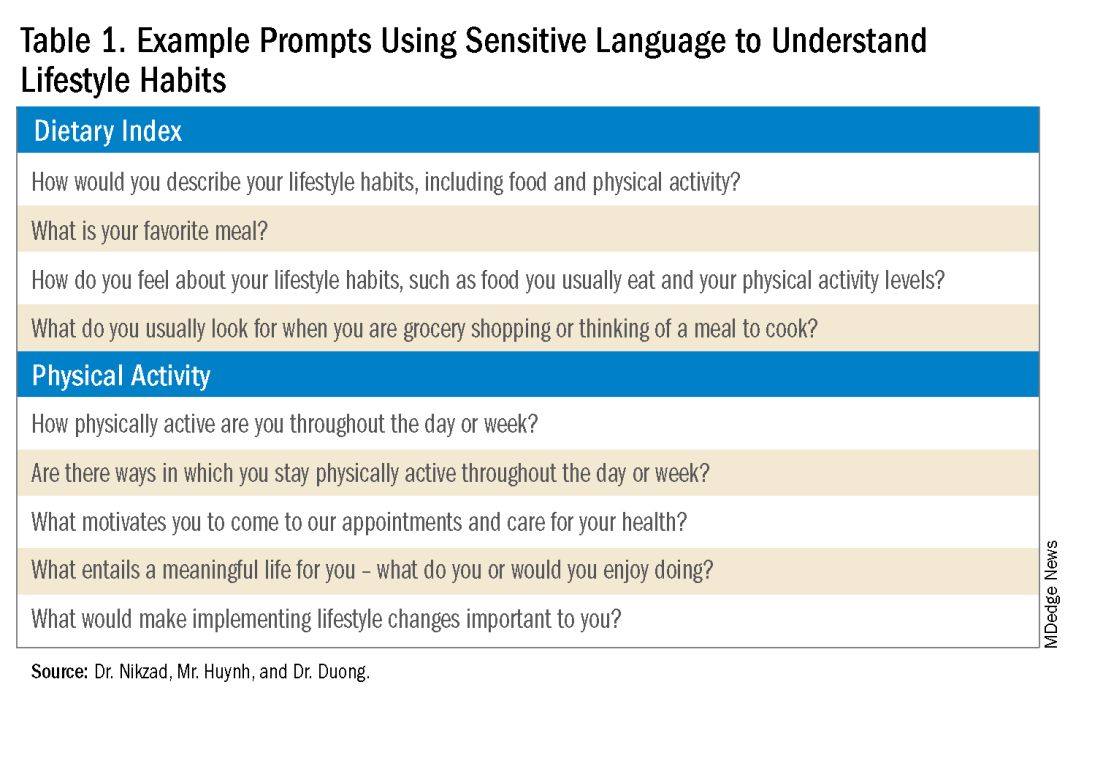

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

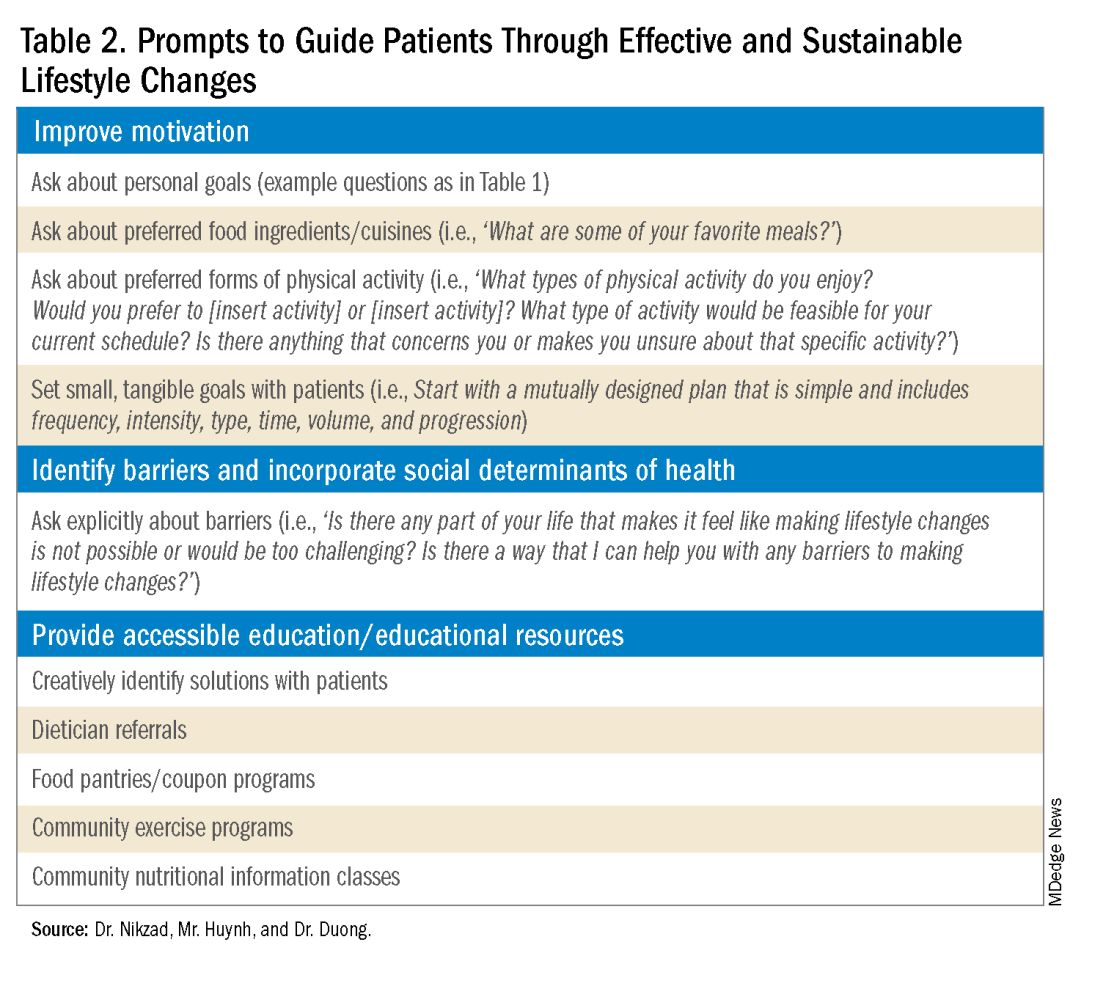

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

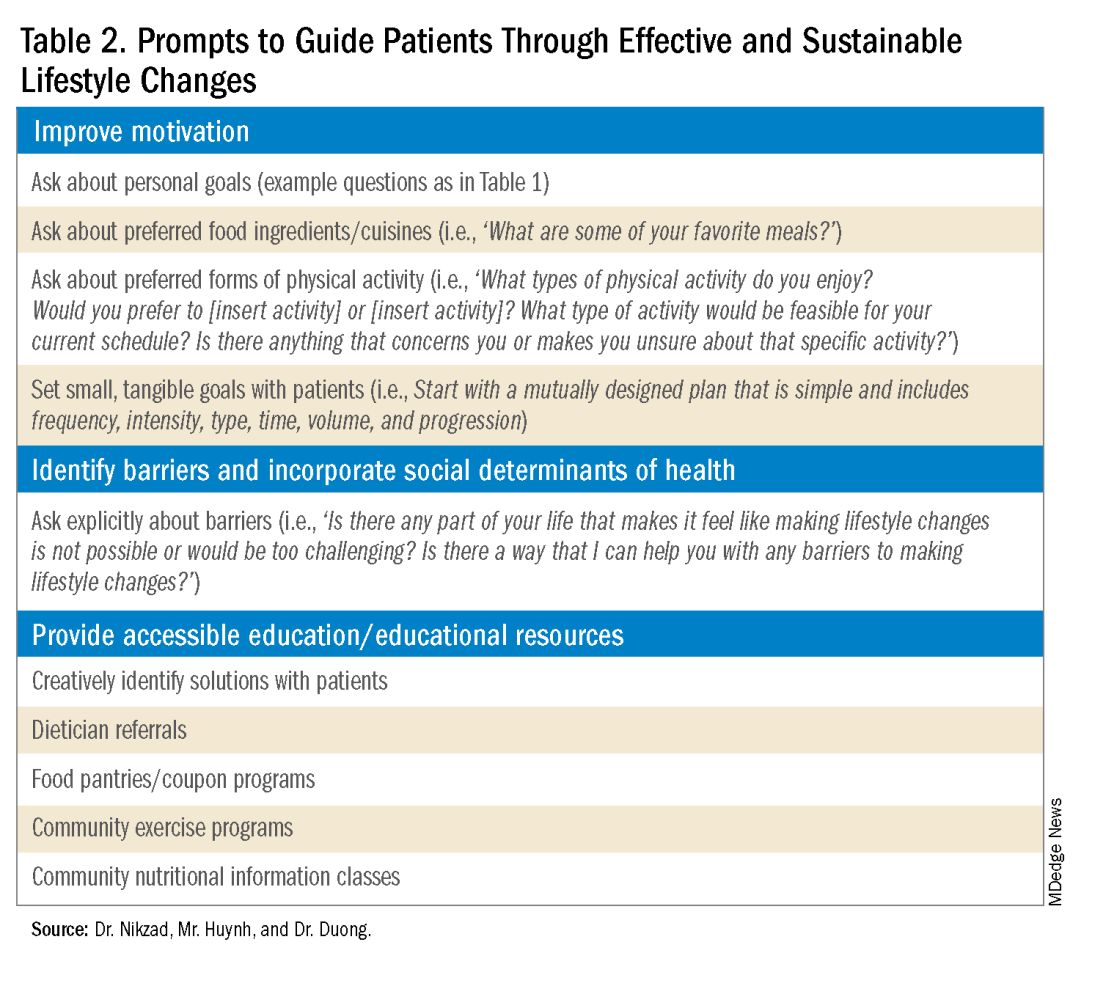

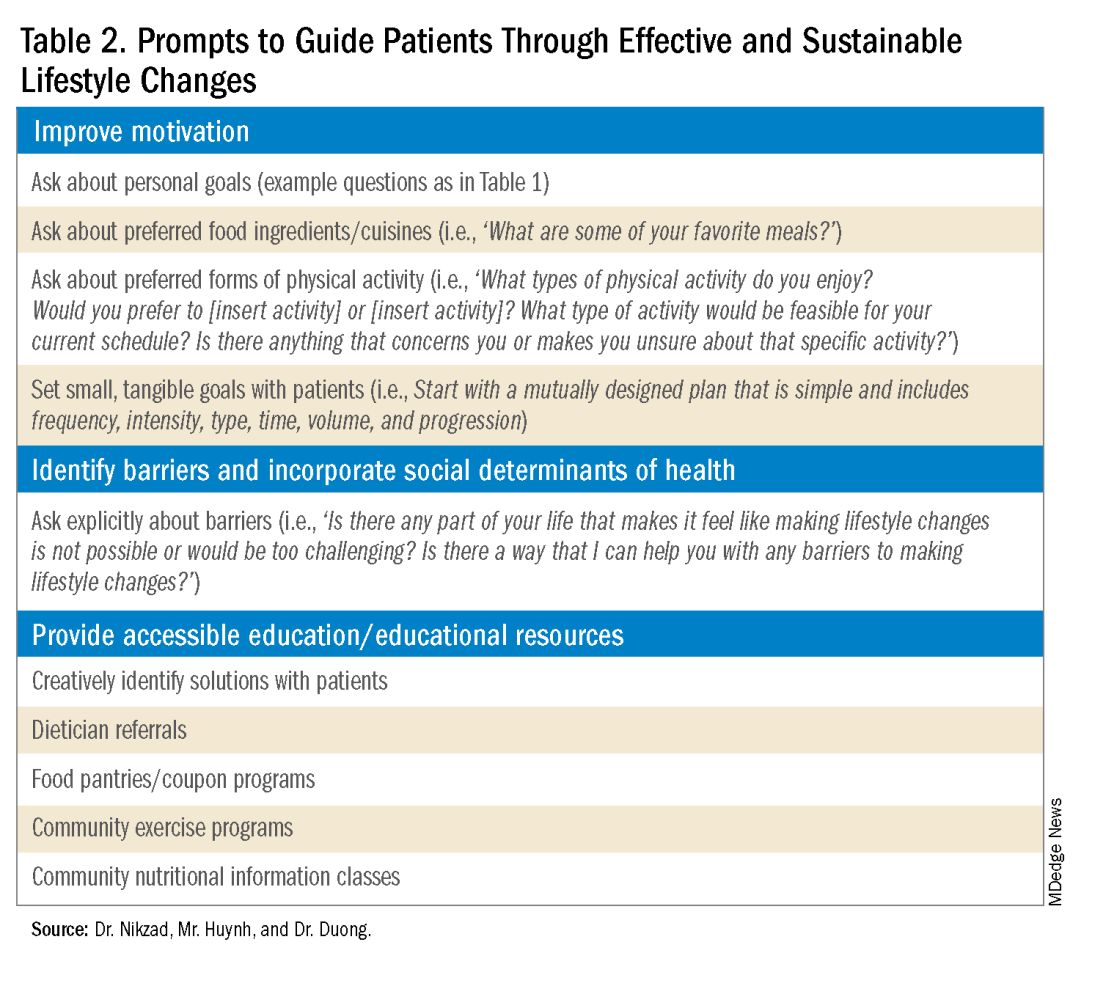

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.