User login

How to Discuss Lifestyle Modifications in MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

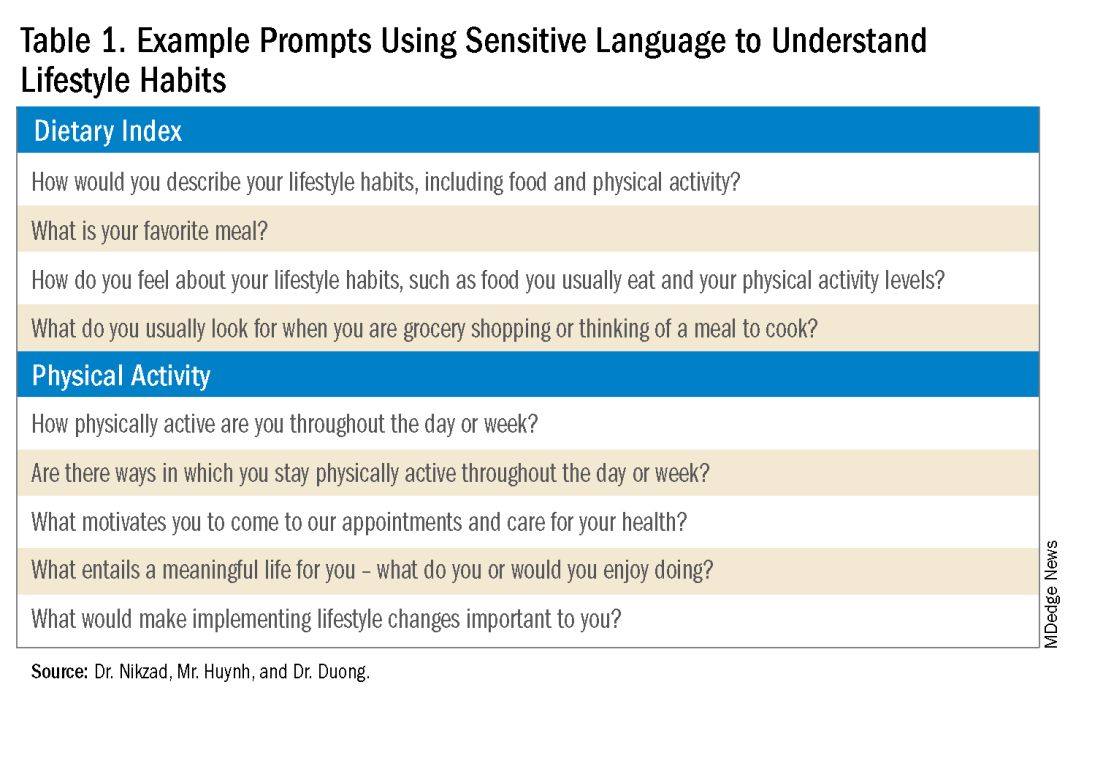

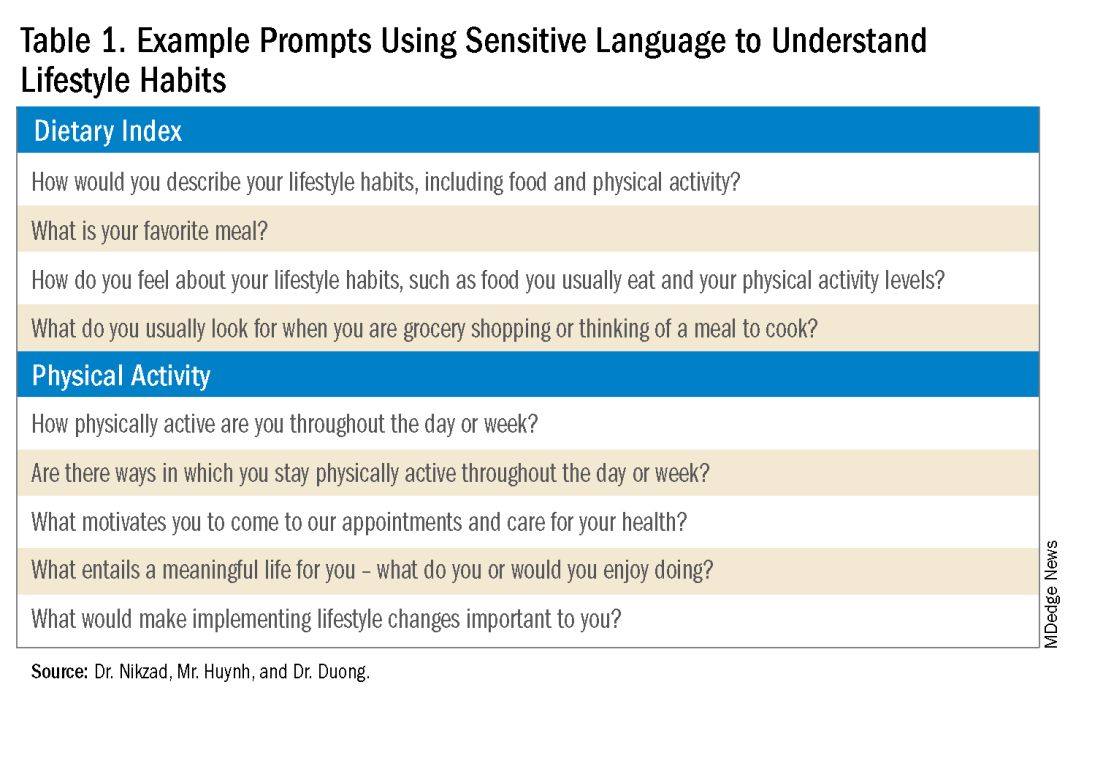

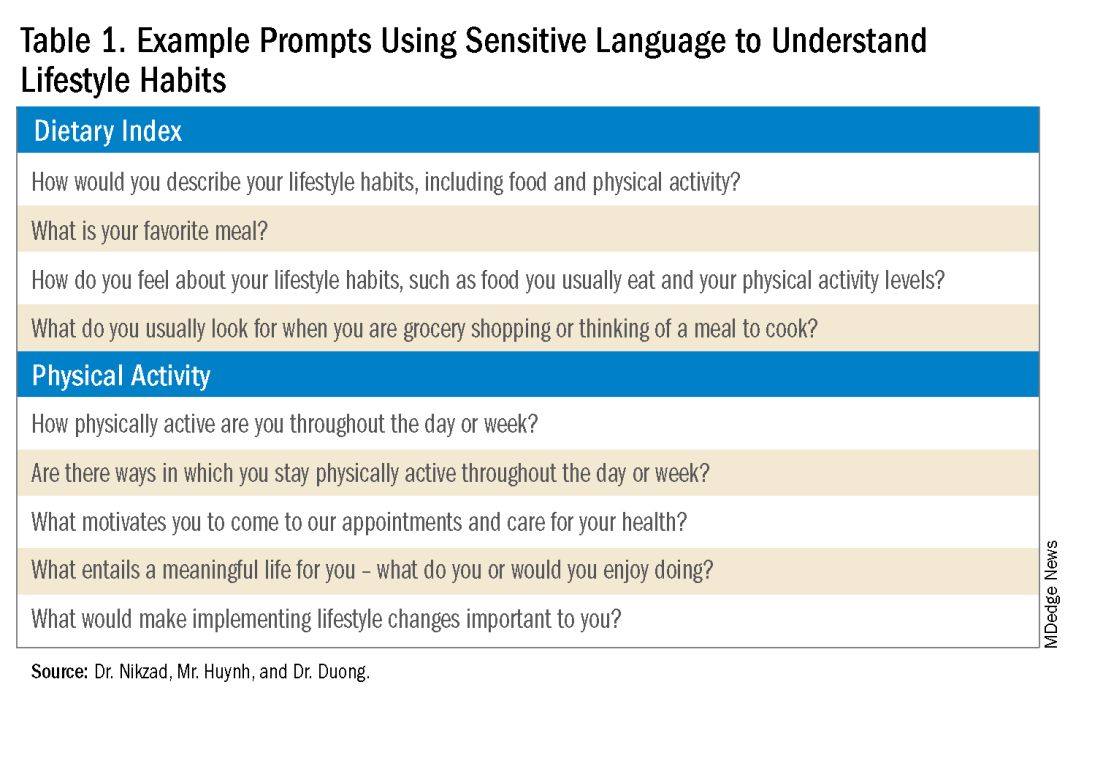

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

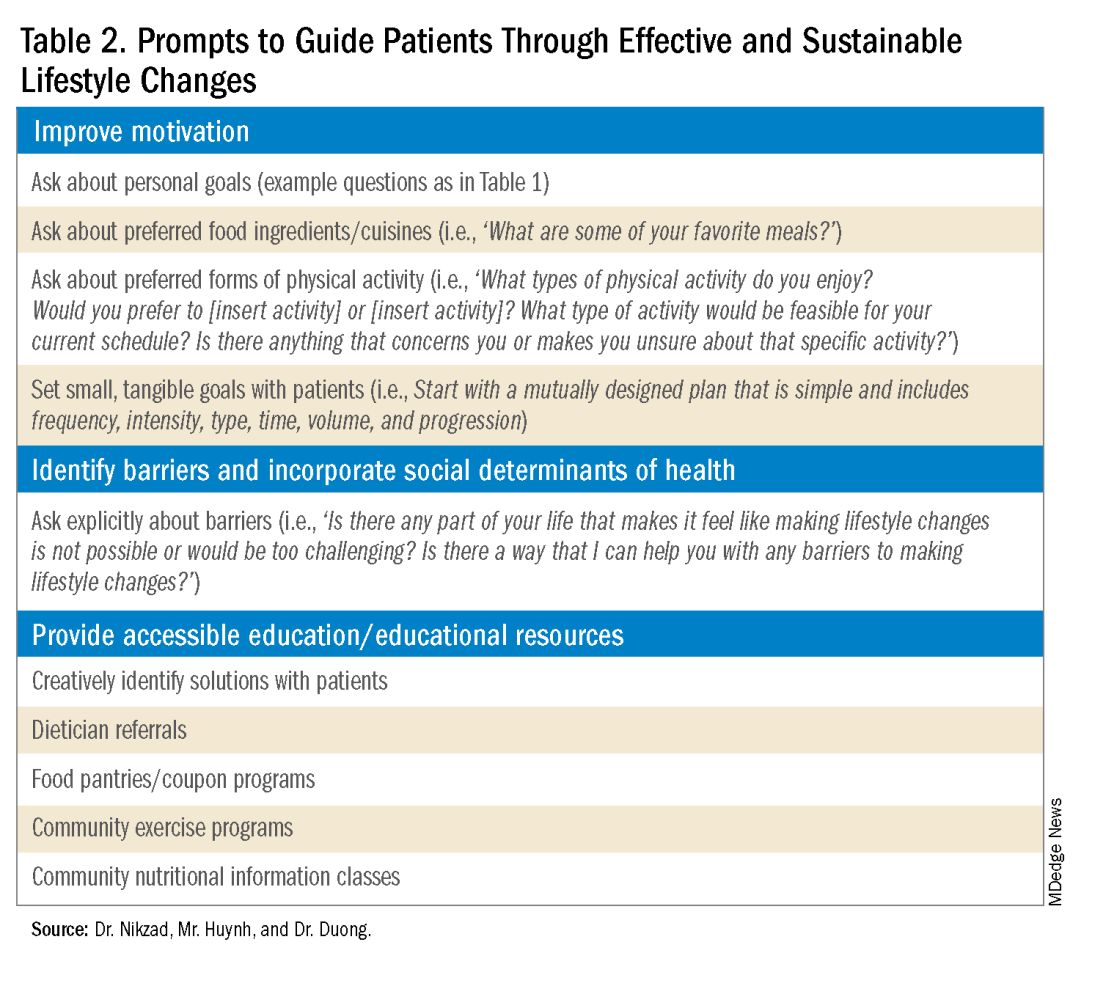

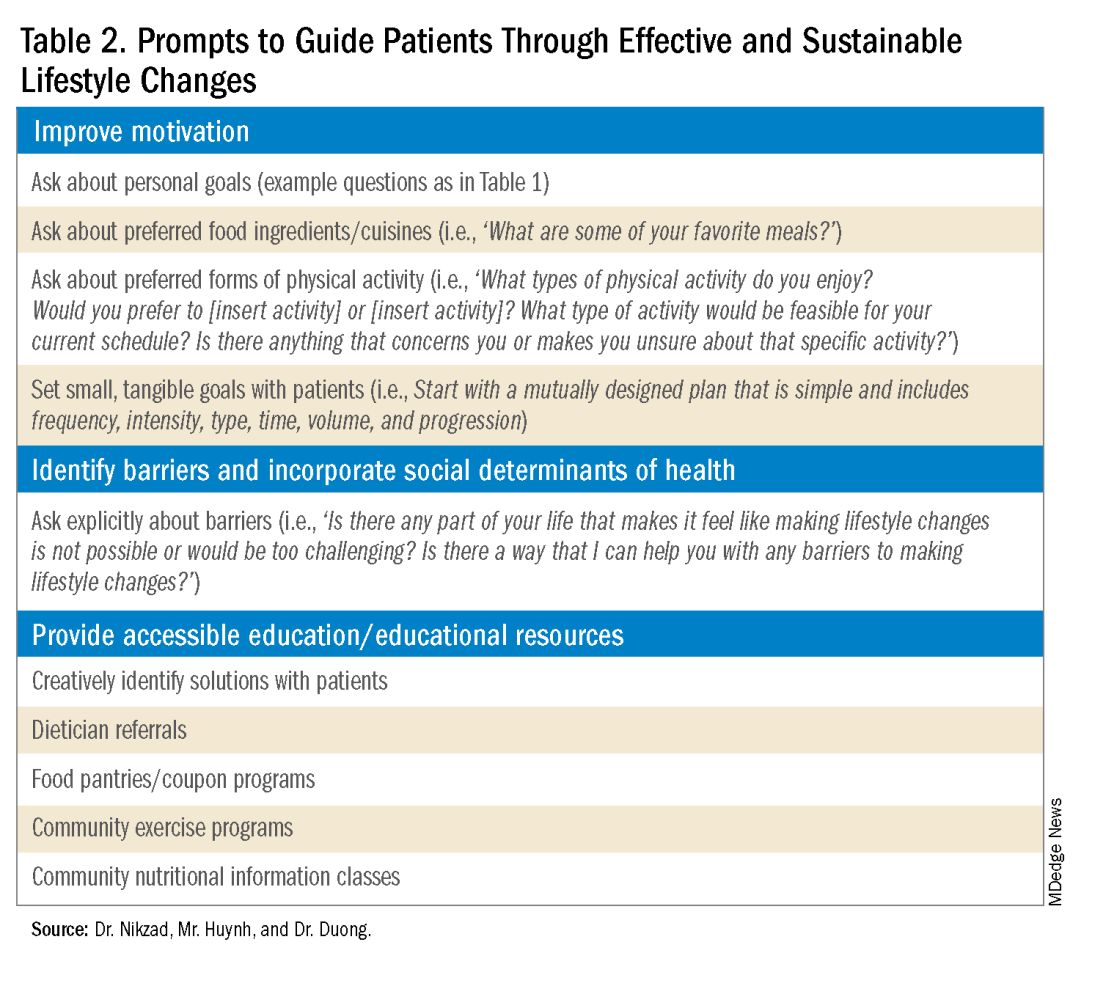

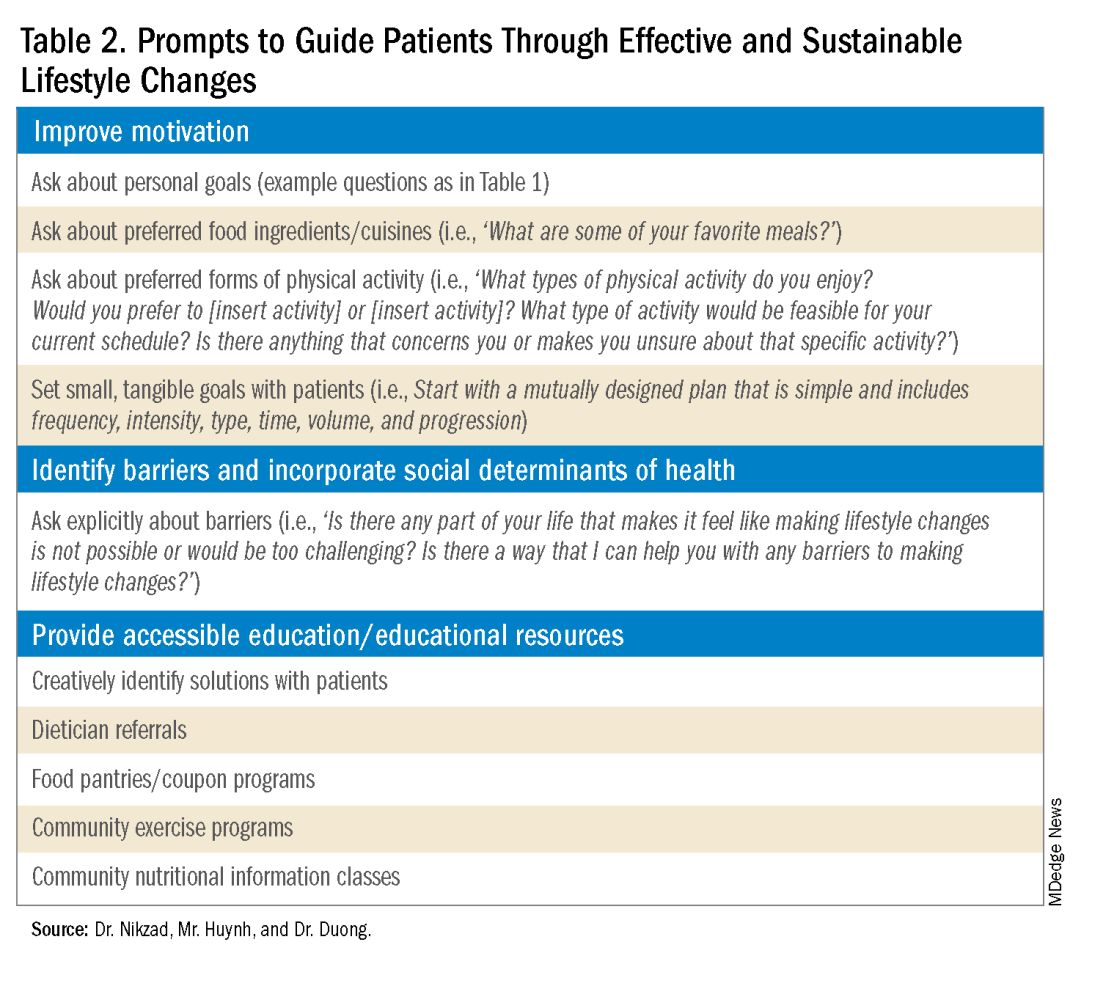

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Naltrexone: a Novel Approach to Pruritus in Polycythemia Vera

P ruritus is a characteristic and often debilitating clinical manifestation reported by about 50% of patients with polycythemia vera (PV). The exact pathophysiology of PV-associated pruritus is poorly understood. The itch sensation may arise from a central phenomenon without skin itch receptor involvement, as is seen in opioid-induced pruritus, or peripherally via unmyelinated C fibers. Various interventions have been used with mixed results for symptom management in this patient population.1

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, have historically demonstrated some efficacy in treating PV-associated pruritus.2 Alongside SSRIs, phlebotomy, antihistamines, phototherapy, interferon a, and myelosuppressive medications also comprise the various current treatment options. In addition to lacking efficacy, antihistamines can cause somnolence, constipation, and xerostomia.3,4 Phlebotomy and cytoreductive therapy are often effective in controlling erythrocytosis but fail to alleviate the disabling pruritus.1,5,6 More recently, suboptimal symptom alleviation has prompted the discovery of agents that target the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) pathways.1

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist shown to suppress pruritus in various dermatologic pathologies involving histamine-independent pathways.3,7,8 A systematic search strategy identified 34 studies on PV-associated pruritus, its pathophysiology and interventions, and naltrexone as a therapeutic agent. Only 1 study in the literature has described the use of naltrexone for uremic and cholestatic pruritus.9 We describe the successful use of naltrexone monotherapy for the treatment of pruritus in a patient with PV.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old man with Jak2-positive PV treated with ruxolitinib presented to the outpatient Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center Supportive Care Clinic in Houston, Texas, for severe refractory pruritus. Wheals manifested in pruritic regions of the patient’s skin without gross excoriations or erythema. Pruritus reportedly began diffusely across the posterior torso. Through the rapid progression of an episode lasting 30 to 45 minutes, the lesions and pruritus would spread to the anterior torso, extend to the upper extremities bilaterally, and finally descend to the lower extremities bilaterally. A persistent sensation of heat or warmth on the patient’s skin was present, and periodically, this would culminate in a burning sensation comparable to “lying flat on one’s back directly on a hornet’s nest…[followed by] a million stings” that was inconsistent with erythromelalgia given the absence of erythema. The intensity of the pruritic episodes was subjectively also described as “enough to make [him] want to jump off the roof of a building…[causing] moments of deep, deep frustration…[and] the worst of all the symptoms one may encounter because of [PV].”

Pruritus was exacerbated by sweating, heat, contact with any liquids on the skin, and sunburns, which doubled the intensity. The patient reported minimal, temporary relief with cannabidiol and cold fabric or air on his skin. His current regimen and nonpharmacologic efforts provided no relief and included oatmeal baths, cornstarch after showers, and patting instead of rubbing the skin with topical products. Trials with nonprescription diphenhydramine, loratadine, and calamine and zinc were not successful. He had not pursued phototherapy due to time limitations and travel constraints. He had a history of phlebotomies and hydroxyurea use, which he preferred to avoid and discontinued 1 year before presentation.

Despite improving hematocrit (< 45% goal) and platelet counts with ruxolitinib, the patient reported worsening pruritus that significantly impaired quality of life. His sleep and social and physical activities were hindered, preventing him from working. The patient’s active medications also included low-dose aspirin, sertraline, hydroxyzine, triamcinolone acetonide, and pregabalin for sciatica. Given persistent symptoms despite multimodal therapy and lifestyle modifications, the patient was started on naltrexone 25 mg daily, which provided immediate relief of symptoms. He continues to have adequate symptom control 2 years after naltrexone initiation.

Literature Review

A systematic search strategy was developed with the assistance of a medical librarian in Medline Ovid, using both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and synonymous keywords. The strategy was then translated to Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane to extract publications investigating PV, pruritus, and/or naltrexone therapy. All searches were conducted on July 18, 2022, and the results of the literature review were as follows: 2 results from Medline Ovid; 34 results from Embase (2 were duplicates of Medline Ovid results); 3 results from Web of Science (all of which were duplicates of Medline Ovid or Embase results); and 0 results from Cochrane (Figure).

Discussion

Although pruritus is a common and often excruciating manifestation of PV, its pathophysiology remains unclear. Some patients with decreasing or newly normal hematocrit and hemoglobin levels have paradoxically experienced an intensification of their pruritus, which introduces erythropoietin signaling pathways as a potential mechanism of the symptom.8 However, iron replacement therapy for patients with exacerbated pruritus after phlebotomies has not demonstrated consistent relief of pruritus.8 Normalization of platelet levels also has not been historically associated with improvement of pruritus.8,9 It has been hypothesized that cells harboring Jak2 mutations at any stage of the hematopoietic pathway mature and accumulate to cause pruritus in PV.9 This theory has been foundational in the development of drugs with activity against cells expressing Jak2 mutations and interventions targeting histamine-releasing mast cells.9-11

The effective use of naltrexone in our patient suggests that histamine may not be the most effective or sole therapeutic target against pruritus in PV. Naltrexone targets opioid receptors in all layers of the epidermis, affecting cell adhesion and keratinocyte production, and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through interactions with nonopioid receptors, including Toll-like receptor 4.12 The efficacy of oral naltrexone has been documented in patients with pruritus associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, psoriasis, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, cholestasis, uremia, and multiple rheumatologic diseases.3,4,7-9,12-14 Opioid pathways also may be involved in peripheral and/or central processing of pruritus associated with PV.

Importantly, patients who are potential candidates for naltrexone therapy should be notified and advised of the risk of drug interactions with opioids, which could lead to symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Other common adverse effects of naltrexone include hepatotoxicity (especially in patients with a history of significant alcohol consumption), abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgias, myalgias, insomnia, headaches, fatigue, and anxiety.12 Therefore, it is integral to screen patients for opioid dependence and determine their baseline liver function. Patients should be monitored following naltrexone initiation to determine whether the drug is an appropriate and effective intervention against PV-associated pruritus.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study demonstrates that naltrexone may be a safe, effective, nonsedating, and cost-efficient oral alternative for refractory PV-associated pruritus. Future directions involve consideration of case series or randomized clinical trials investigating the efficacy of naltrexone in treating PV-associated pruritus. Further research is also warranted to better understand the pathophysiology of this symptom of PV to enhance and potentially expand medical management for patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Sisson (The Texas Medical Center Library) for her guidance and support in the literature review methodology.

1. Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(9):828-834. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x

2. Tefferi A, Fonseca R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are effective in the treatment of polycythemia vera-associated pruritus. Blood. 2002;99(7):2627. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.7.2627

3. Lee J, Shin JU, Noh S, Park CO, Lee KH. Clinical efficacy and safety of naltrexone combination therapy in older patients with severe pruritus. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):159-163. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.159

4. Phan NQ, Bernhard JD, Luger TA, Stander S. Antipruritic treatment with systemic mu-opioid receptor antagonists: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):680-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.052

5. Metze D, Reimann S, Beissert S, Luger T. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):533-539.

6. Malekzad F, Arbabi M, Mohtasham N, et al. Efficacy of oral naltrexone on pruritus in atopic eczema: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):948-950. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03129.x

7. Terg R, Coronel E, Sorda J, Munoz AE, Findor J. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00318-5

8. Lelonek E, Matusiak L, Wrobel T, Szepietowski JC. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: clinical characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(5):496-500. doi:10.2340/00015555-2906

9. Siegel FP, Tauscher J, Petrides PE. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: characteristics and influence on quality of life in 441 patients. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(8):665-669. doi:10.1002/ajh.23474

10. Al-Mashdali AF, Kashgary WR, Yassin MA. Ruxolitinib (a JAK2 inhibitor) as an emerging therapy for refractory pruritis in a patient with low-risk polycythemia vera: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(44):e27722. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000027722

11. Benevolo G, Vassallo F, Urbino I, Giai V. Polycythemia vera (PV): update on emerging treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:209-221. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S213020

12. Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1746-1752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.031

13. de Carvalho JF, Skare T. Low-dose naltrexone in rheumatological diseases. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2023;34(1):1-6. doi:10.31138/mjr.34.1.1

14. Singh R, Patel P, Thakker M, Sharma P, Barnes M, Montana S. Naloxone and maintenance naltrexone as novel and effective therapies for immunotherapy-induced pruritus: a case report and brief literature review. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(6):347-348. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00797

P ruritus is a characteristic and often debilitating clinical manifestation reported by about 50% of patients with polycythemia vera (PV). The exact pathophysiology of PV-associated pruritus is poorly understood. The itch sensation may arise from a central phenomenon without skin itch receptor involvement, as is seen in opioid-induced pruritus, or peripherally via unmyelinated C fibers. Various interventions have been used with mixed results for symptom management in this patient population.1

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, have historically demonstrated some efficacy in treating PV-associated pruritus.2 Alongside SSRIs, phlebotomy, antihistamines, phototherapy, interferon a, and myelosuppressive medications also comprise the various current treatment options. In addition to lacking efficacy, antihistamines can cause somnolence, constipation, and xerostomia.3,4 Phlebotomy and cytoreductive therapy are often effective in controlling erythrocytosis but fail to alleviate the disabling pruritus.1,5,6 More recently, suboptimal symptom alleviation has prompted the discovery of agents that target the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) pathways.1

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist shown to suppress pruritus in various dermatologic pathologies involving histamine-independent pathways.3,7,8 A systematic search strategy identified 34 studies on PV-associated pruritus, its pathophysiology and interventions, and naltrexone as a therapeutic agent. Only 1 study in the literature has described the use of naltrexone for uremic and cholestatic pruritus.9 We describe the successful use of naltrexone monotherapy for the treatment of pruritus in a patient with PV.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old man with Jak2-positive PV treated with ruxolitinib presented to the outpatient Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center Supportive Care Clinic in Houston, Texas, for severe refractory pruritus. Wheals manifested in pruritic regions of the patient’s skin without gross excoriations or erythema. Pruritus reportedly began diffusely across the posterior torso. Through the rapid progression of an episode lasting 30 to 45 minutes, the lesions and pruritus would spread to the anterior torso, extend to the upper extremities bilaterally, and finally descend to the lower extremities bilaterally. A persistent sensation of heat or warmth on the patient’s skin was present, and periodically, this would culminate in a burning sensation comparable to “lying flat on one’s back directly on a hornet’s nest…[followed by] a million stings” that was inconsistent with erythromelalgia given the absence of erythema. The intensity of the pruritic episodes was subjectively also described as “enough to make [him] want to jump off the roof of a building…[causing] moments of deep, deep frustration…[and] the worst of all the symptoms one may encounter because of [PV].”

Pruritus was exacerbated by sweating, heat, contact with any liquids on the skin, and sunburns, which doubled the intensity. The patient reported minimal, temporary relief with cannabidiol and cold fabric or air on his skin. His current regimen and nonpharmacologic efforts provided no relief and included oatmeal baths, cornstarch after showers, and patting instead of rubbing the skin with topical products. Trials with nonprescription diphenhydramine, loratadine, and calamine and zinc were not successful. He had not pursued phototherapy due to time limitations and travel constraints. He had a history of phlebotomies and hydroxyurea use, which he preferred to avoid and discontinued 1 year before presentation.

Despite improving hematocrit (< 45% goal) and platelet counts with ruxolitinib, the patient reported worsening pruritus that significantly impaired quality of life. His sleep and social and physical activities were hindered, preventing him from working. The patient’s active medications also included low-dose aspirin, sertraline, hydroxyzine, triamcinolone acetonide, and pregabalin for sciatica. Given persistent symptoms despite multimodal therapy and lifestyle modifications, the patient was started on naltrexone 25 mg daily, which provided immediate relief of symptoms. He continues to have adequate symptom control 2 years after naltrexone initiation.

Literature Review

A systematic search strategy was developed with the assistance of a medical librarian in Medline Ovid, using both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and synonymous keywords. The strategy was then translated to Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane to extract publications investigating PV, pruritus, and/or naltrexone therapy. All searches were conducted on July 18, 2022, and the results of the literature review were as follows: 2 results from Medline Ovid; 34 results from Embase (2 were duplicates of Medline Ovid results); 3 results from Web of Science (all of which were duplicates of Medline Ovid or Embase results); and 0 results from Cochrane (Figure).

Discussion

Although pruritus is a common and often excruciating manifestation of PV, its pathophysiology remains unclear. Some patients with decreasing or newly normal hematocrit and hemoglobin levels have paradoxically experienced an intensification of their pruritus, which introduces erythropoietin signaling pathways as a potential mechanism of the symptom.8 However, iron replacement therapy for patients with exacerbated pruritus after phlebotomies has not demonstrated consistent relief of pruritus.8 Normalization of platelet levels also has not been historically associated with improvement of pruritus.8,9 It has been hypothesized that cells harboring Jak2 mutations at any stage of the hematopoietic pathway mature and accumulate to cause pruritus in PV.9 This theory has been foundational in the development of drugs with activity against cells expressing Jak2 mutations and interventions targeting histamine-releasing mast cells.9-11

The effective use of naltrexone in our patient suggests that histamine may not be the most effective or sole therapeutic target against pruritus in PV. Naltrexone targets opioid receptors in all layers of the epidermis, affecting cell adhesion and keratinocyte production, and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through interactions with nonopioid receptors, including Toll-like receptor 4.12 The efficacy of oral naltrexone has been documented in patients with pruritus associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, psoriasis, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, cholestasis, uremia, and multiple rheumatologic diseases.3,4,7-9,12-14 Opioid pathways also may be involved in peripheral and/or central processing of pruritus associated with PV.

Importantly, patients who are potential candidates for naltrexone therapy should be notified and advised of the risk of drug interactions with opioids, which could lead to symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Other common adverse effects of naltrexone include hepatotoxicity (especially in patients with a history of significant alcohol consumption), abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgias, myalgias, insomnia, headaches, fatigue, and anxiety.12 Therefore, it is integral to screen patients for opioid dependence and determine their baseline liver function. Patients should be monitored following naltrexone initiation to determine whether the drug is an appropriate and effective intervention against PV-associated pruritus.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study demonstrates that naltrexone may be a safe, effective, nonsedating, and cost-efficient oral alternative for refractory PV-associated pruritus. Future directions involve consideration of case series or randomized clinical trials investigating the efficacy of naltrexone in treating PV-associated pruritus. Further research is also warranted to better understand the pathophysiology of this symptom of PV to enhance and potentially expand medical management for patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Sisson (The Texas Medical Center Library) for her guidance and support in the literature review methodology.

P ruritus is a characteristic and often debilitating clinical manifestation reported by about 50% of patients with polycythemia vera (PV). The exact pathophysiology of PV-associated pruritus is poorly understood. The itch sensation may arise from a central phenomenon without skin itch receptor involvement, as is seen in opioid-induced pruritus, or peripherally via unmyelinated C fibers. Various interventions have been used with mixed results for symptom management in this patient population.1

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, have historically demonstrated some efficacy in treating PV-associated pruritus.2 Alongside SSRIs, phlebotomy, antihistamines, phototherapy, interferon a, and myelosuppressive medications also comprise the various current treatment options. In addition to lacking efficacy, antihistamines can cause somnolence, constipation, and xerostomia.3,4 Phlebotomy and cytoreductive therapy are often effective in controlling erythrocytosis but fail to alleviate the disabling pruritus.1,5,6 More recently, suboptimal symptom alleviation has prompted the discovery of agents that target the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) pathways.1

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist shown to suppress pruritus in various dermatologic pathologies involving histamine-independent pathways.3,7,8 A systematic search strategy identified 34 studies on PV-associated pruritus, its pathophysiology and interventions, and naltrexone as a therapeutic agent. Only 1 study in the literature has described the use of naltrexone for uremic and cholestatic pruritus.9 We describe the successful use of naltrexone monotherapy for the treatment of pruritus in a patient with PV.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old man with Jak2-positive PV treated with ruxolitinib presented to the outpatient Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center Supportive Care Clinic in Houston, Texas, for severe refractory pruritus. Wheals manifested in pruritic regions of the patient’s skin without gross excoriations or erythema. Pruritus reportedly began diffusely across the posterior torso. Through the rapid progression of an episode lasting 30 to 45 minutes, the lesions and pruritus would spread to the anterior torso, extend to the upper extremities bilaterally, and finally descend to the lower extremities bilaterally. A persistent sensation of heat or warmth on the patient’s skin was present, and periodically, this would culminate in a burning sensation comparable to “lying flat on one’s back directly on a hornet’s nest…[followed by] a million stings” that was inconsistent with erythromelalgia given the absence of erythema. The intensity of the pruritic episodes was subjectively also described as “enough to make [him] want to jump off the roof of a building…[causing] moments of deep, deep frustration…[and] the worst of all the symptoms one may encounter because of [PV].”

Pruritus was exacerbated by sweating, heat, contact with any liquids on the skin, and sunburns, which doubled the intensity. The patient reported minimal, temporary relief with cannabidiol and cold fabric or air on his skin. His current regimen and nonpharmacologic efforts provided no relief and included oatmeal baths, cornstarch after showers, and patting instead of rubbing the skin with topical products. Trials with nonprescription diphenhydramine, loratadine, and calamine and zinc were not successful. He had not pursued phototherapy due to time limitations and travel constraints. He had a history of phlebotomies and hydroxyurea use, which he preferred to avoid and discontinued 1 year before presentation.

Despite improving hematocrit (< 45% goal) and platelet counts with ruxolitinib, the patient reported worsening pruritus that significantly impaired quality of life. His sleep and social and physical activities were hindered, preventing him from working. The patient’s active medications also included low-dose aspirin, sertraline, hydroxyzine, triamcinolone acetonide, and pregabalin for sciatica. Given persistent symptoms despite multimodal therapy and lifestyle modifications, the patient was started on naltrexone 25 mg daily, which provided immediate relief of symptoms. He continues to have adequate symptom control 2 years after naltrexone initiation.

Literature Review

A systematic search strategy was developed with the assistance of a medical librarian in Medline Ovid, using both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and synonymous keywords. The strategy was then translated to Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane to extract publications investigating PV, pruritus, and/or naltrexone therapy. All searches were conducted on July 18, 2022, and the results of the literature review were as follows: 2 results from Medline Ovid; 34 results from Embase (2 were duplicates of Medline Ovid results); 3 results from Web of Science (all of which were duplicates of Medline Ovid or Embase results); and 0 results from Cochrane (Figure).

Discussion

Although pruritus is a common and often excruciating manifestation of PV, its pathophysiology remains unclear. Some patients with decreasing or newly normal hematocrit and hemoglobin levels have paradoxically experienced an intensification of their pruritus, which introduces erythropoietin signaling pathways as a potential mechanism of the symptom.8 However, iron replacement therapy for patients with exacerbated pruritus after phlebotomies has not demonstrated consistent relief of pruritus.8 Normalization of platelet levels also has not been historically associated with improvement of pruritus.8,9 It has been hypothesized that cells harboring Jak2 mutations at any stage of the hematopoietic pathway mature and accumulate to cause pruritus in PV.9 This theory has been foundational in the development of drugs with activity against cells expressing Jak2 mutations and interventions targeting histamine-releasing mast cells.9-11

The effective use of naltrexone in our patient suggests that histamine may not be the most effective or sole therapeutic target against pruritus in PV. Naltrexone targets opioid receptors in all layers of the epidermis, affecting cell adhesion and keratinocyte production, and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through interactions with nonopioid receptors, including Toll-like receptor 4.12 The efficacy of oral naltrexone has been documented in patients with pruritus associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, psoriasis, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, cholestasis, uremia, and multiple rheumatologic diseases.3,4,7-9,12-14 Opioid pathways also may be involved in peripheral and/or central processing of pruritus associated with PV.

Importantly, patients who are potential candidates for naltrexone therapy should be notified and advised of the risk of drug interactions with opioids, which could lead to symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Other common adverse effects of naltrexone include hepatotoxicity (especially in patients with a history of significant alcohol consumption), abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgias, myalgias, insomnia, headaches, fatigue, and anxiety.12 Therefore, it is integral to screen patients for opioid dependence and determine their baseline liver function. Patients should be monitored following naltrexone initiation to determine whether the drug is an appropriate and effective intervention against PV-associated pruritus.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study demonstrates that naltrexone may be a safe, effective, nonsedating, and cost-efficient oral alternative for refractory PV-associated pruritus. Future directions involve consideration of case series or randomized clinical trials investigating the efficacy of naltrexone in treating PV-associated pruritus. Further research is also warranted to better understand the pathophysiology of this symptom of PV to enhance and potentially expand medical management for patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Sisson (The Texas Medical Center Library) for her guidance and support in the literature review methodology.

1. Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(9):828-834. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x

2. Tefferi A, Fonseca R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are effective in the treatment of polycythemia vera-associated pruritus. Blood. 2002;99(7):2627. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.7.2627

3. Lee J, Shin JU, Noh S, Park CO, Lee KH. Clinical efficacy and safety of naltrexone combination therapy in older patients with severe pruritus. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):159-163. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.159

4. Phan NQ, Bernhard JD, Luger TA, Stander S. Antipruritic treatment with systemic mu-opioid receptor antagonists: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):680-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.052

5. Metze D, Reimann S, Beissert S, Luger T. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):533-539.

6. Malekzad F, Arbabi M, Mohtasham N, et al. Efficacy of oral naltrexone on pruritus in atopic eczema: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):948-950. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03129.x

7. Terg R, Coronel E, Sorda J, Munoz AE, Findor J. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00318-5

8. Lelonek E, Matusiak L, Wrobel T, Szepietowski JC. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: clinical characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(5):496-500. doi:10.2340/00015555-2906

9. Siegel FP, Tauscher J, Petrides PE. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: characteristics and influence on quality of life in 441 patients. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(8):665-669. doi:10.1002/ajh.23474

10. Al-Mashdali AF, Kashgary WR, Yassin MA. Ruxolitinib (a JAK2 inhibitor) as an emerging therapy for refractory pruritis in a patient with low-risk polycythemia vera: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(44):e27722. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000027722

11. Benevolo G, Vassallo F, Urbino I, Giai V. Polycythemia vera (PV): update on emerging treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:209-221. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S213020

12. Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1746-1752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.031

13. de Carvalho JF, Skare T. Low-dose naltrexone in rheumatological diseases. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2023;34(1):1-6. doi:10.31138/mjr.34.1.1

14. Singh R, Patel P, Thakker M, Sharma P, Barnes M, Montana S. Naloxone and maintenance naltrexone as novel and effective therapies for immunotherapy-induced pruritus: a case report and brief literature review. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(6):347-348. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00797

1. Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(9):828-834. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x

2. Tefferi A, Fonseca R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are effective in the treatment of polycythemia vera-associated pruritus. Blood. 2002;99(7):2627. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.7.2627

3. Lee J, Shin JU, Noh S, Park CO, Lee KH. Clinical efficacy and safety of naltrexone combination therapy in older patients with severe pruritus. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):159-163. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.159

4. Phan NQ, Bernhard JD, Luger TA, Stander S. Antipruritic treatment with systemic mu-opioid receptor antagonists: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):680-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.052

5. Metze D, Reimann S, Beissert S, Luger T. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):533-539.

6. Malekzad F, Arbabi M, Mohtasham N, et al. Efficacy of oral naltrexone on pruritus in atopic eczema: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):948-950. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03129.x

7. Terg R, Coronel E, Sorda J, Munoz AE, Findor J. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00318-5

8. Lelonek E, Matusiak L, Wrobel T, Szepietowski JC. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: clinical characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(5):496-500. doi:10.2340/00015555-2906

9. Siegel FP, Tauscher J, Petrides PE. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: characteristics and influence on quality of life in 441 patients. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(8):665-669. doi:10.1002/ajh.23474

10. Al-Mashdali AF, Kashgary WR, Yassin MA. Ruxolitinib (a JAK2 inhibitor) as an emerging therapy for refractory pruritis in a patient with low-risk polycythemia vera: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(44):e27722. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000027722

11. Benevolo G, Vassallo F, Urbino I, Giai V. Polycythemia vera (PV): update on emerging treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:209-221. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S213020

12. Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1746-1752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.031

13. de Carvalho JF, Skare T. Low-dose naltrexone in rheumatological diseases. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2023;34(1):1-6. doi:10.31138/mjr.34.1.1

14. Singh R, Patel P, Thakker M, Sharma P, Barnes M, Montana S. Naloxone and maintenance naltrexone as novel and effective therapies for immunotherapy-induced pruritus: a case report and brief literature review. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(6):347-348. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00797