User login

Evaluation of Pharmacist-Driven Inhaled Corticosteroid De-escalation in Veterans

Evaluation of Pharmacist-Driven Inhaled Corticosteroid De-escalation in Veterans

Systemic glucocorticoids play an important role in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations. They are recommended to shorten recovery time and increase forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) during exacerbations.1 However, the role of the chronic use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in the treatment of COPD is less clear.

When added to inhaled β-2 agonists and muscarinic antagonists, ICSs can decrease the risk of exacerbations.1 However, not all patients with COPD benefit from ICS therapy. The degree of benefit an ICS can provide has been shown to correlate with eosinophil count—a marker of inflammation. The expected benefit of using an ICS increases as the eosinophil count increases.1 Maximum benefit can be observed with eosinophil counts ≥ 300 cells/µL, and minimal benefit is observed with eosinophil counts < 100 cells/µL. Adverse effects (AEs) of ICSs include a hoarse voice, oral candidiasis, and an increased risk of pneumonia.1 Given the risk of AEs, it is important to limit ICS use in patients who are unlikely to reap any benefits.

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines suggest the use of ICSs in patients who experience exacerbations while using long-acting β agonist (LABA) plus long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) therapy and have an eosinophil count ≥ 100 cells/µL. Switching from LABA or LAMA monotherapy to triple therapy with LAMA/LABA/ICS may be considered if patients have continued exacerbations and an eosinophil count ≥ 300 cells/µL. De-escalation of ICS therapy should be considered if patients do not meet these criteria or if patients experience ICS AEs, such as pneumonia. The patients most likely to have increased exacerbations or decreased FEV1 with ICS withdrawal are those with eosinophil counts ≥ 300 cells/µL.1,2

Several studies have explored the effects of ICS de-escalation in real-world clinical settings. A systematic review of 11 studies indicated that de-escalation of ICS in COPD does not result in increased exacerbations.3 A prospective study by Rossi et al found that in a 6-month period, 141 of 482 patients on ICS therapy (29%) had an exacerbation. In the opposing arm of the study, 88 of 334 patients (26%) with deprescribed ICS experienced an exacerbation. The difference between these 2 groups was not statistically significant.4 The researchers concluded that in real-world practice, ICS withdrawal can be safe in patients at low risk of exacerbation.

About 25% of veterans (1.25 million) have been diagnosed with COPD.5 To address this, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and US Department of Defense published updated COPD guidelines in 2021 that specify criteria for de-escalation of ICS.6 Guidelines, however, may not be reflected in common clinical practice for several years following publication. The VA Academic Detailing Service (ADS) provides tools to help clinicians identify patients who may benefit from changes in treatment plans. A recent ADS focus was the implementation of a COPD dashboard, which identifies patients with COPD who are candidates for ICS de-escalation based on comorbid diagnoses, exacerbation history, and eosinophil count. VA pharmacists have an expanded role in the management of primary care disease states and are therefore well-positioned to increase adherence to guideline-directed therapy. The objective of this quality improvement project was to determine the impact of pharmacist-driven de-escalation on ICS usage in veterans with COPD.

Methods

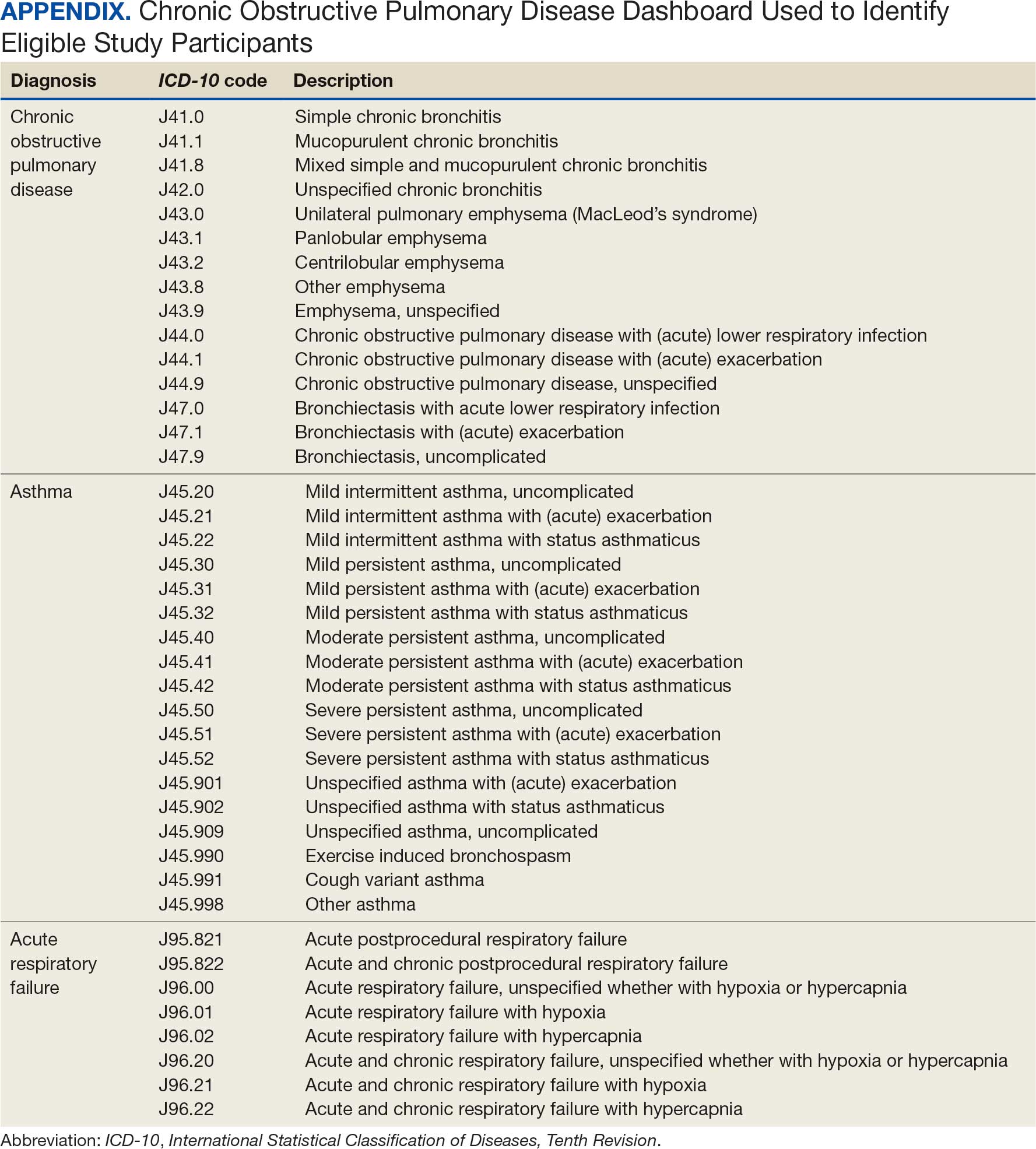

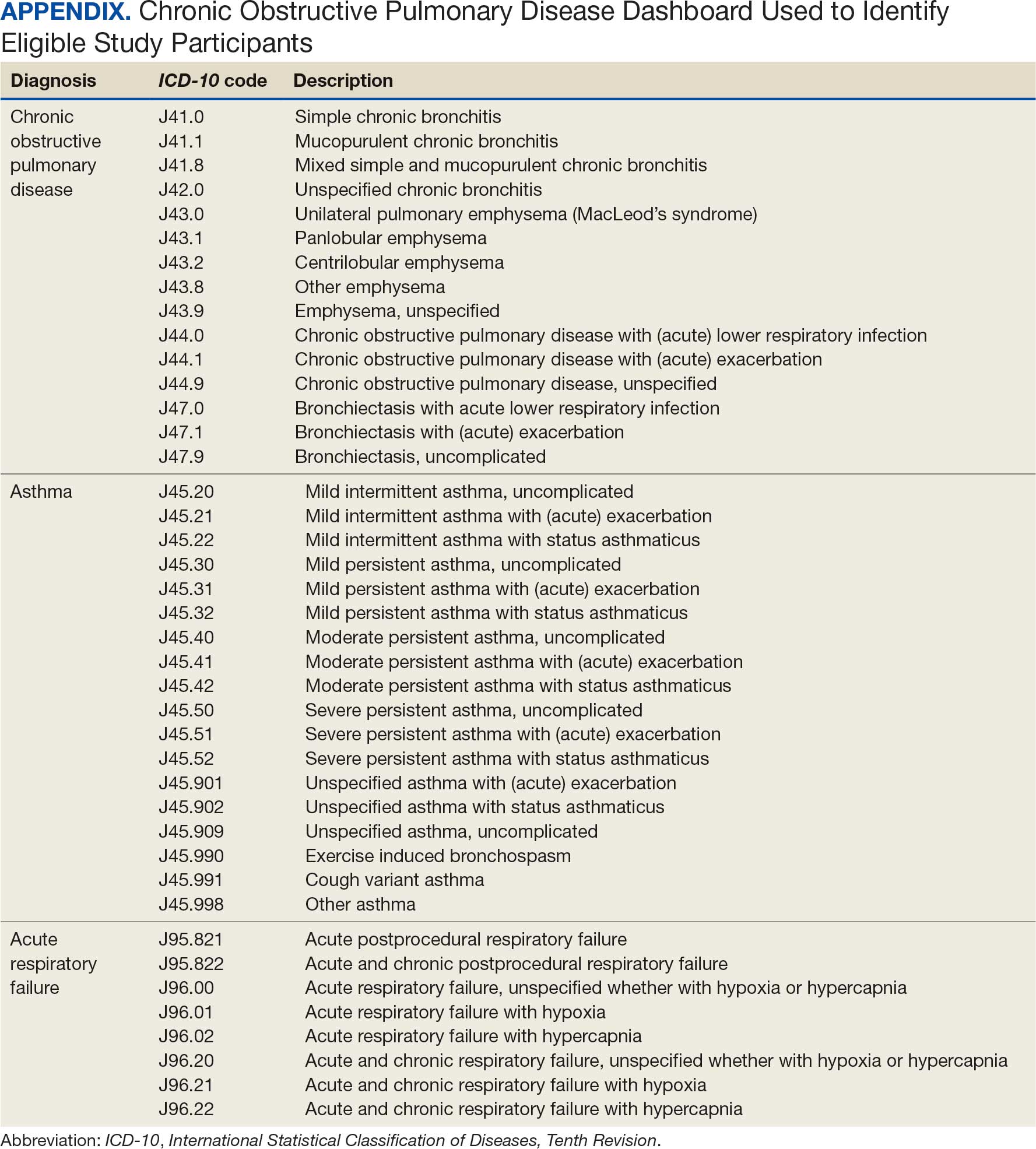

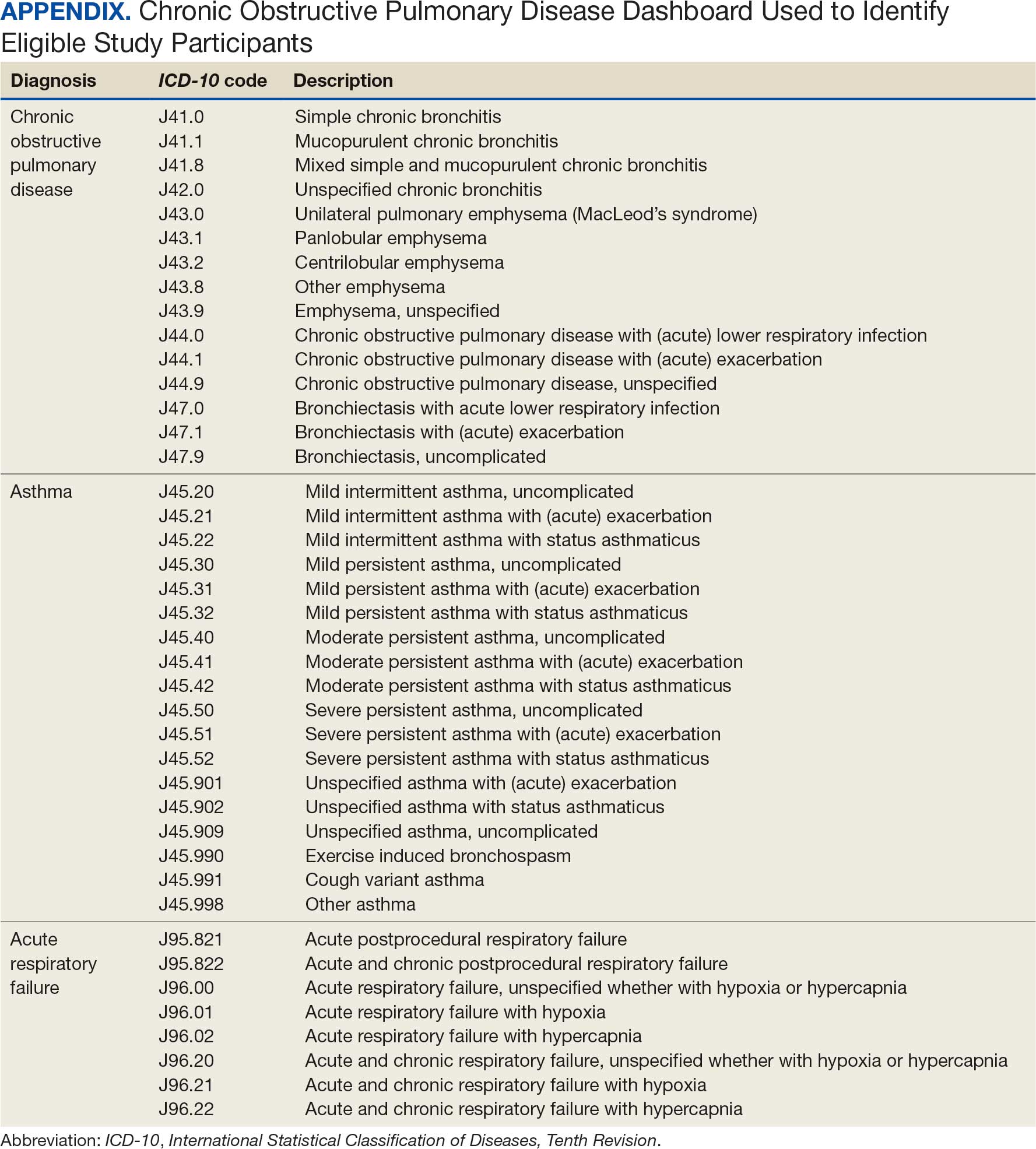

This project was conducted in an outpatient clinic at the Robley Rex VA Medical Center beginning September 21, 2023, with a progress note in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Eligible patients were selected using the COPD Dashboard provided by ADS. The COPD Dashboard defined patients with COPD as those with ≥ 2 outpatient COPD diagnoses in the past 2 years, 1 inpatient discharge COPD diagnosis in the past year, or COPD listed as an active problem. COPD diagnoses were identified using International Statistical Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes

Candidates identified for ICS de-escalation by the dashboard were excluded if they had a history of COPD exacerbation in the previous 2 years. The dashboard identified COPD exacerbations via ICD-10 codes for COPD or acute respiratory failure for inpatient discharges, emergency department (ED) visits, urgent care visits, and community care consults with 1 of the following terms: emergency, inpatient, hospital, urgent, ED (self). The COPD dashboard excluded patients with a diagnosis of asthma.

After patients were selected, they were screened for additional exclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if a pulmonary care practitioner managed their COPD; if identified via an active pulmonary consult in CPRS; if a non-VA clinician prescribed their ICS; or if they were being treated with roflumilast, theophylline, or chronic azithromycin. Individuals taking these 3 drugs were excluded due to potential severe and/or refractory COPD. Patients also were excluded if they: (1) had prior ICS de-escalation failure (defined as a COPD exacerbation following ICS de-escalation that resulted in ICS resumption); (2) had a COPD exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids or antibiotics in the previous year; (3) had active lung cancer; (4) did not have any eosinophil levels in CPRS within the previous 2 years; or (5) had any eosinophil levels ≥ 300 cells/µL in the previous year.

Each patient who met the inclusion criteria and was not excluded received a focused medication review by a pharmacist who created a templated progress note, with patient-specific recommendations, that was entered in the CPRS (eAppendix). The recommendations were also attached as an addendum to the patient’s last primary care visit note, and the primary care practitioner (PCP) was alerted via CPRS to consider ICS de-escalation and non-ICS alternatives. Tapering of ICS therapy was offered as an option to de-escalate if abrupt discontinuation was deemed inappropriate. PCPs were also prompted to consider referral to a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist for management and follow-up of ICS de-escalation.

The primary outcome was the number of patients with de-escalated ICS at 3 and 6 months following the recommendation. Secondary outcomes included the number of: patients who were no longer prescribed an ICS or who had a non-ICS alternative initiated at a pharmacist’s recommendation; patients who were referred to a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist for ICS de-escalation; COPD exacerbations requiring systemic steroids or antibiotics, or requiring an ED visit, inpatient admission, or urgent-care clinic visit; and cases of pneumonia or oral candidiasis. Primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated via chart review in CPRS. For secondary outcomes of pneumonia and COPD exacerbation, identification was made by documented diagnosis in CPRS. For continuous data such as age, the mean was calculated.

Results

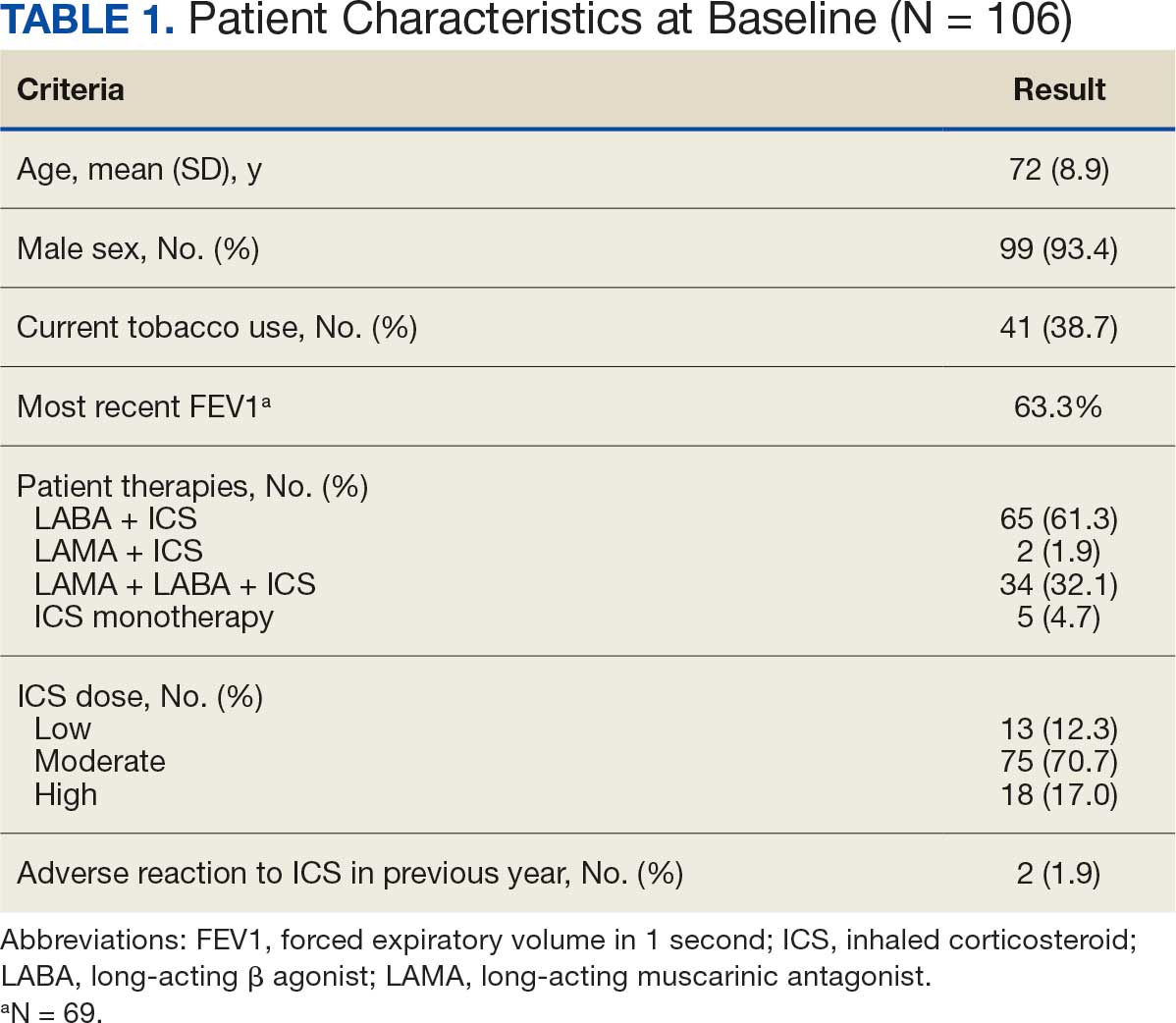

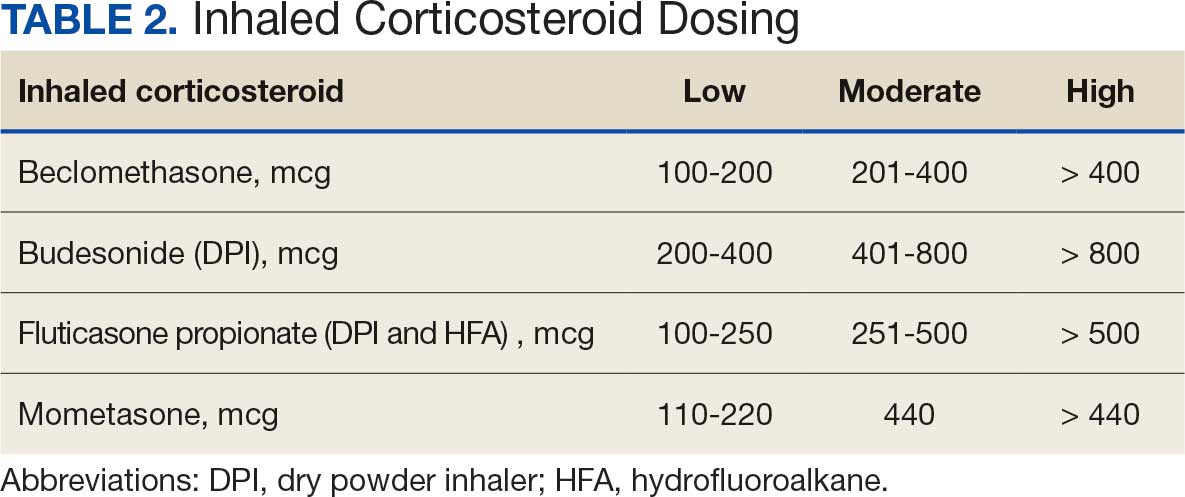

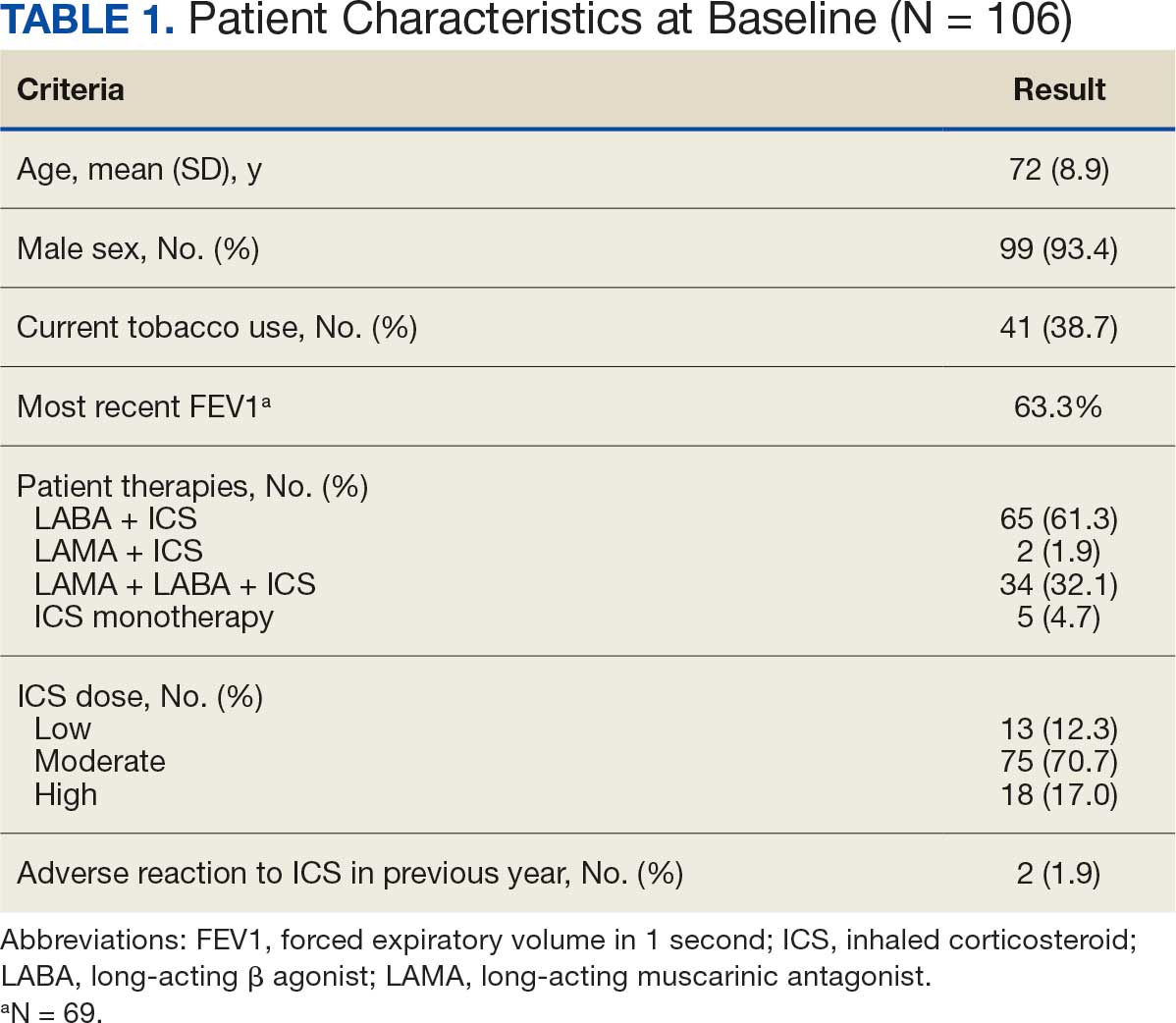

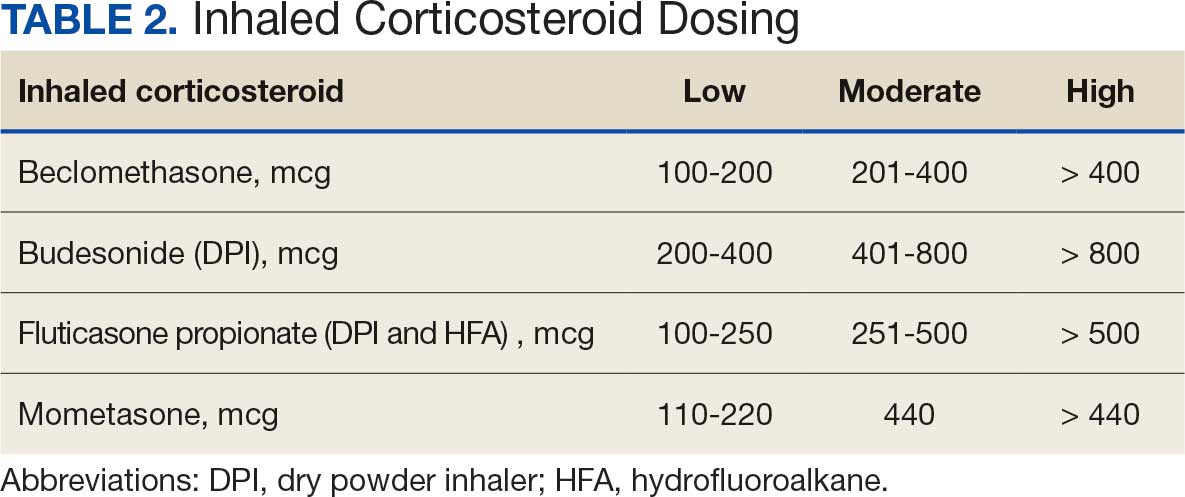

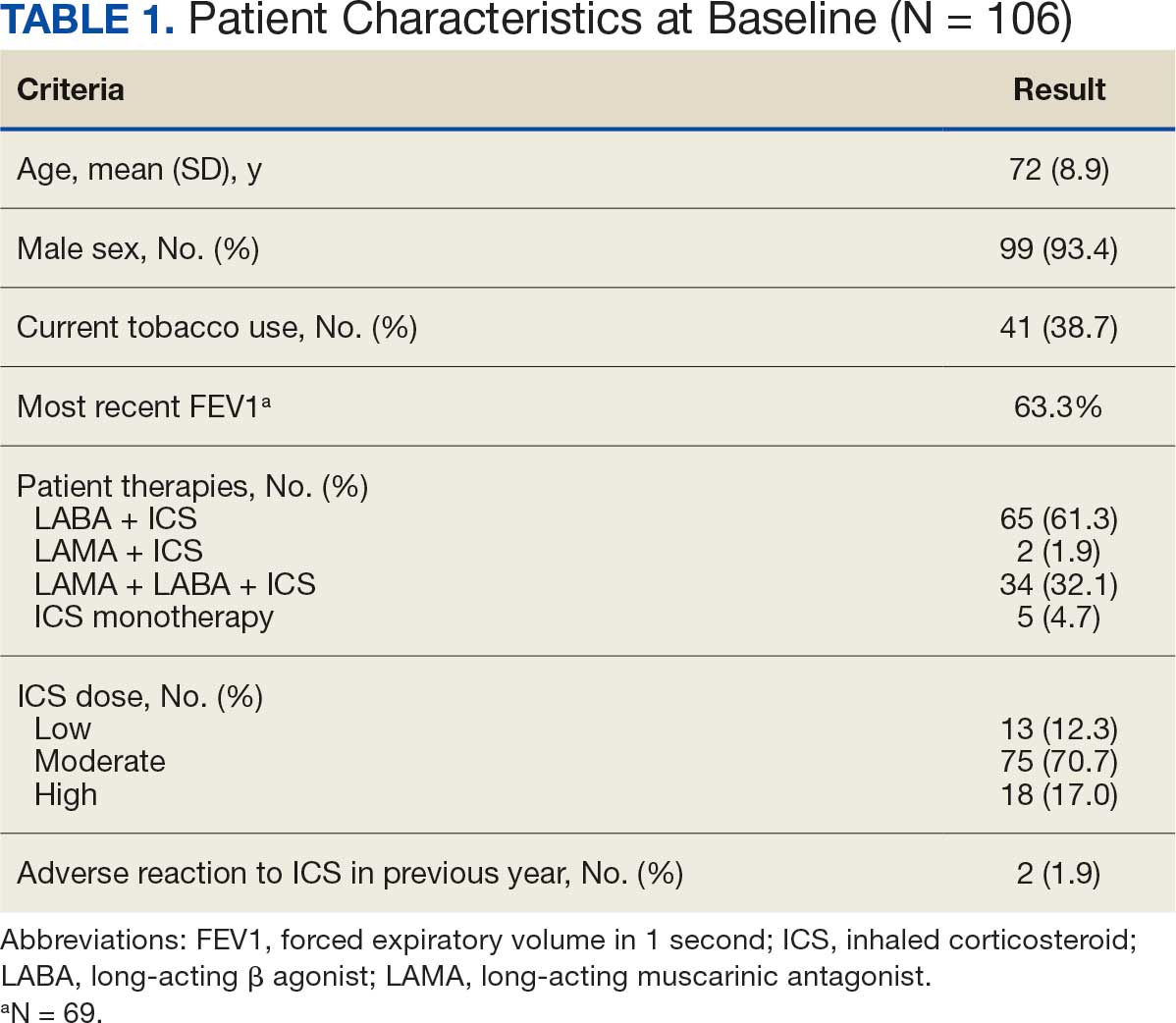

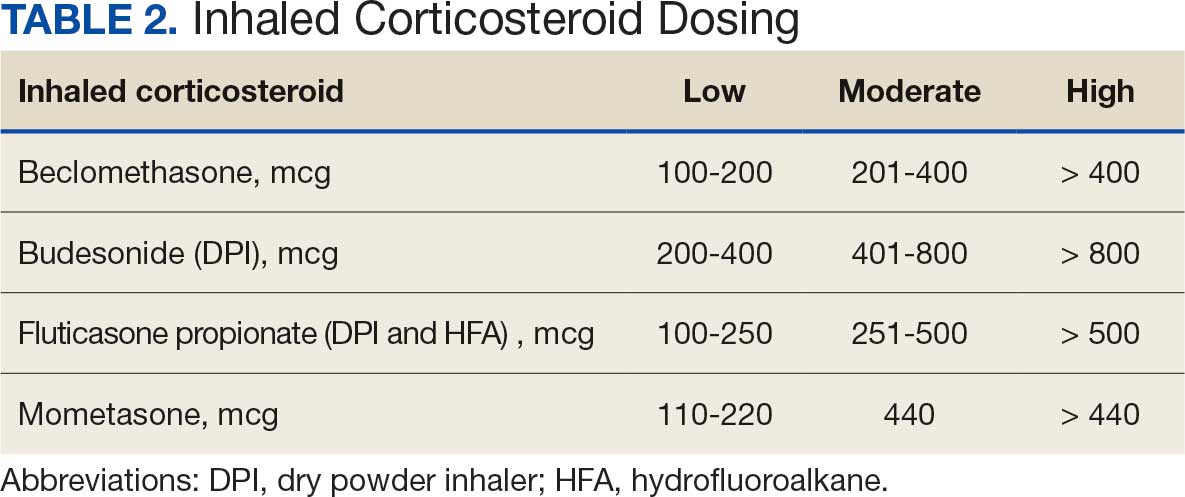

Pharmacist ICS de-escalation recommendations were made between September 21, 2023, and November 19, 2023, for 106 patients. The mean age was 72 years and 99 (93%) patients were male (Table 1). Forty-one (39%) of the patients used tobacco at the time of the study. FEV1 was available for 69 patients with a mean of 63% (GOLD grade 2).1 Based on FEV1 values, 16 patients had mild COPD (GOLD grade 1), 37 patients had moderate COPD (GOLD grade 2), 14 patients had severe COPD (GOLD grade 3), and 2 patients had very severe COPD (GOLD grade 4).1 Thirty-four patients received LABA + LAMA + ICS, 65 received LABA + ICS, 2 received LAMA + ICS, and 5 received ICS monotherapy. The most common dose of ICS was a moderate dose (Table 2). Only 2 patients had an ICS AE in the previous year.

ICS de-escalation recommendations resulted in ICS de-escalation in 50 (47.2%) and 62 (58.5%) patients at 3 and 6 months, respectively. The 6-month ICS de-escalation rate by ICS dose at baseline was 72.2% (high dose), 60.0% (moderate), and 30.8% (low). De-escalation at 6 months by GOLD grade at baseline was 56.3% (9 of 16 patients, GOLD 1), 64.9% (24 of 37 patients, GOLD 2), 50% (7 of 14 patients, GOLD 3), and 50% (1 of 2 patients, GOLD 4). Six months after the ICS de-escalation recommendation appeared in the CPRS, the percentage of patients on LABA + ICS therapy dropped from 65 patients (61.3%) at baseline to 25 patients (23.6%).

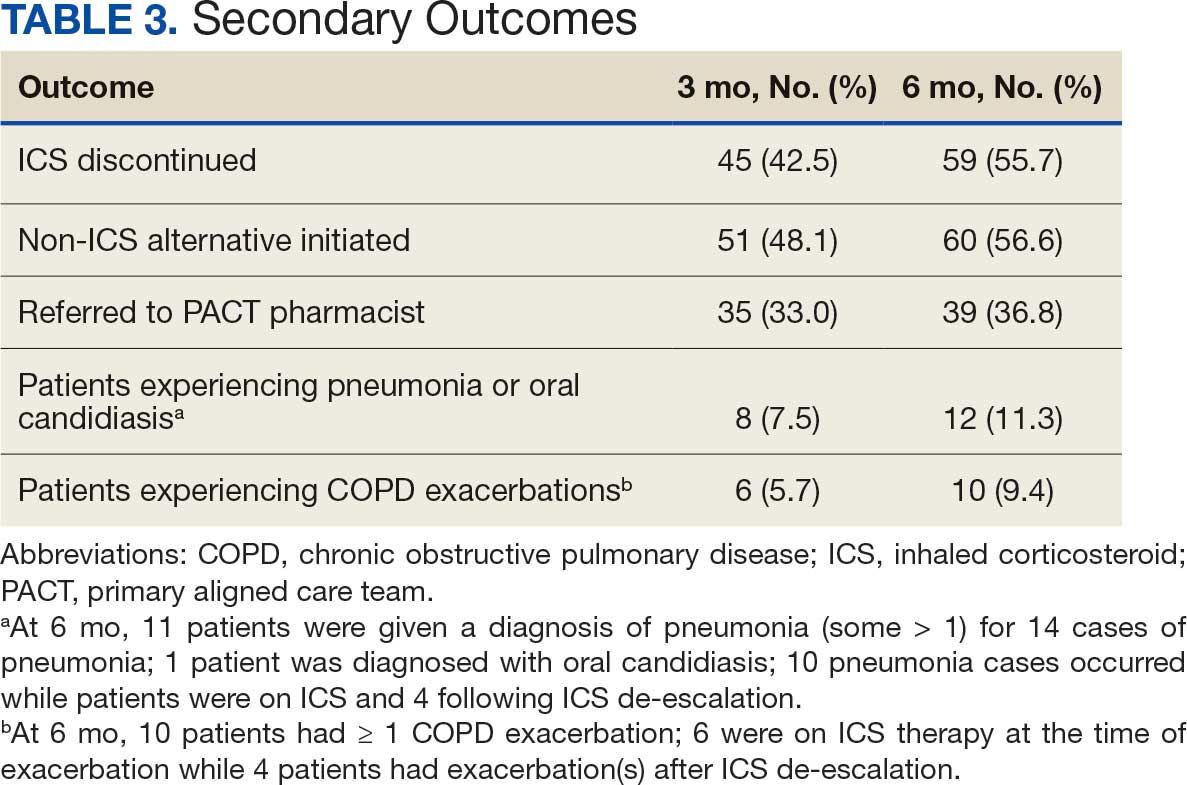

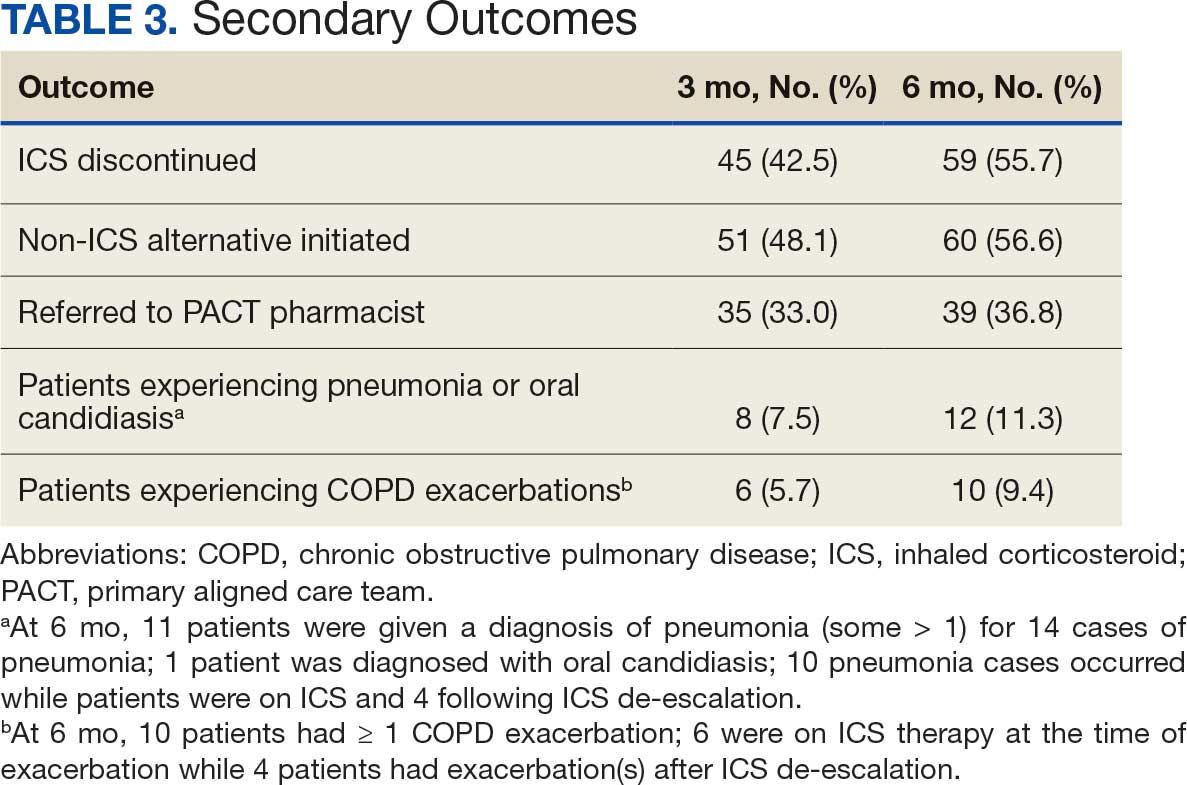

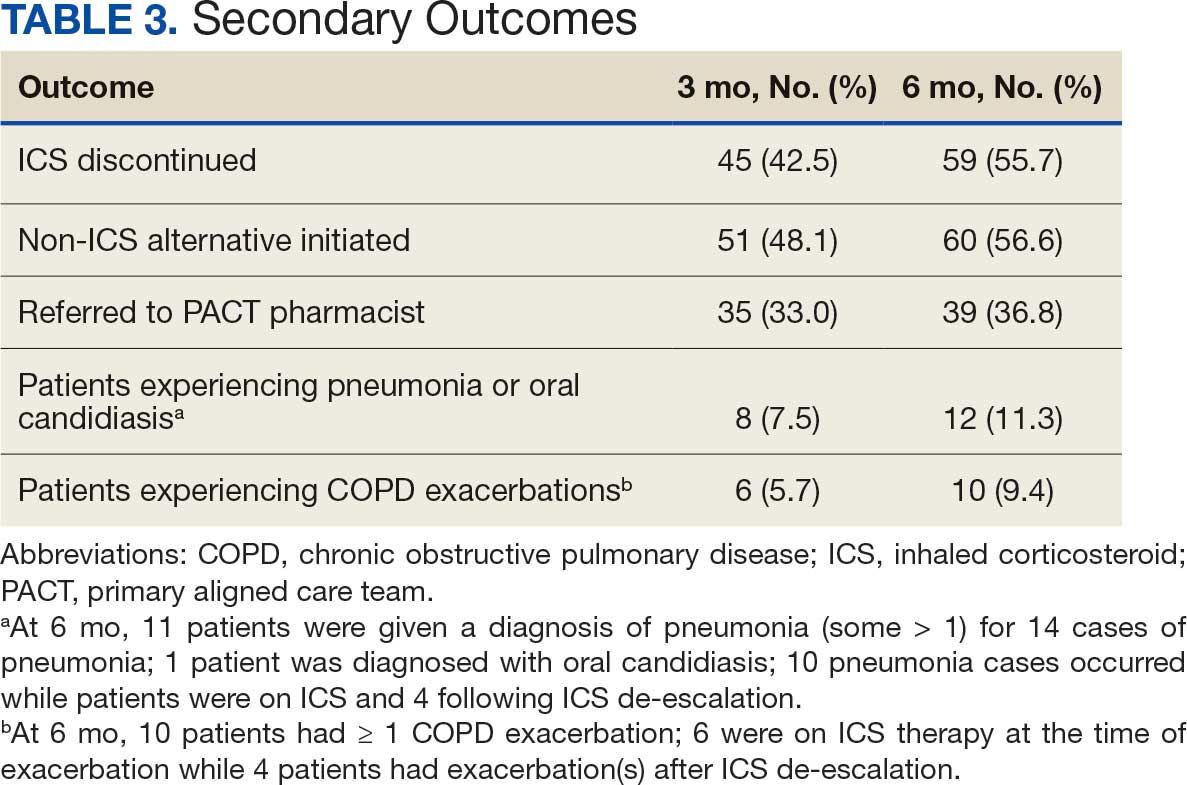

Secondary outcomes were assessed at 3 and 6 months following the recommendation. Most patients with de-escalated ICS had their ICS discontinued and a non-ICS alternative initiated per pharmacist recommendations. At 6 months, 39 patients (36.8%) patients were referred to a patient aligned care team (PACT) pharmacist for de-escalation. Of the 39 patients referred to pharmacists, 69.2% (27 patients) were de-escalated; this compared to 52.2% (35 patients) who were not referred to pharmacists (Table 3).

ICS use increases the risk of pneumonia.1 At 6 months, 11 patients were diagnosed with pneumonia; 3 patients were diagnosed with pneumonia twice, resulting in a total of 14 cases. Ten cases occurred while patients were on ICS and 4 cases occurred following ICS de-escalation. One patient had a documented case of oral candidiasis that occurred while on ICS therapy; no patients with discontinued ICS were diagnosed with oral candidiasis. In addition, 10 patients had COPD exacerbations; however no patients had exacerbations both before and after de-escalation. Six patients were on ICS therapy when they experienced an exacerbation, and 4 patients had an exacerbation after ICS de-escalation.

Discussion

More than half of patients receiving the pharmacist intervention achieved the primary outcome of ICS de-escalation at 6 months. Furthermore, a larger percentage of patients referred to pharmacists for the management of ICS de-escalation successfully achieved de-escalation compared to those who were not referred. These outcomes reflect the important role pharmacists can play in identifying appropriate candidates for ICS de-escalation and assisting in the management of ICS de-escalation. Patients referred to pharmacists also received other services such as smoking cessation pharmacotherapy and counseling on inhaler technique and adherence. These interventions can support improved COPD clinical outcomes.

The purpose of de-escalating ICS therapy is to reduce the risk of AEs such as pneumonia and oral candidiasis.1 The secondary outcomes of this study support previous evidence that patients who have de-escalated ICS therapy may have reduced risk of AEs compared to those who remain on ICS therapy.3 Specifically, of the 14 cases of pneumonia that occurred during the study, 10 cases occurred while patients were on ICS and 4 cases occurred following ICS de-escalation.

ICS de-escalation may increase risk of increased COPD exacerbations.1 However, the secondary outcomes of this study do not indicate that those with de-escalated ICS had more COPD exacerbations compared to those who continued on ICS. Pharmacists’ recommendations were more effective for patients with less severe COPD based on baseline FEV1.

The previous GOLD Guidelines for COPD suggested LABA + ICS therapy as an option for patients with a high symptom and exacerbation burden (previously known as GOLD Group D). Guidelines no longer recommend LABA + ICS therapy due to the superiority of triple inhaled therapy for exacerbations and the superiority of LAMA + LABA therapy for dyspnea.7 A majority of identified patients in this project were on LABA + ICS therapy alone at baseline. The ICS de-escalation recommendation resulted in a 61.5% reduction in patients on LABA + ICS therapy at 6 months. By decreasing the number of patients on LABA + ICS without LAMA, recommendations increased the number of patients on guideline-directed therapy.

Limitations

This study lacked a control group, and the rate of ICS de-escalation in patients who did not receive a pharmacist recommendation was not assessed. Therefore, it could not be determined whether the pharmacist recommendation is more effective than no recommendation. Another limitation was our inability to access records from non-VA health care facilities. This may have resulted in missed COPD exacerbations, pneumonia, and oral candidiasis prior to or following the pharmacist recommendation.

In addition, the method used to notify PCPs of the pharmacist recommendation was a CPRS alert. Clinicians often receive multiple daily alerts and may not always pay close attention to them due to alert fatigue. Early in the study, some PCPs were unknowingly omitted from the alert of the pharmacist recommendation for 10 patients due to human error. For 8 of these 10 patients, the PCP was notified of the recommendations during the 3-month follow-up period. However, 2 patients had COPD exacerbations during the 3-month follow-up period. In these cases, the PCP was not alerted to de-escalate ICS. The data for these patients were collected at 3 and 6 months in the same manner as all other patients. Also, 7 of 35 patients who were referred to a pharmacist for ICS de-escalation did not have a scheduled appointment. These patients were considered to be lost to follow-up and this may have resulted in an underestimation of the ability of pharmacists to successfully de-escalate ICS in patients with COPD.

Other studies have evaluated the efficacy of a pharmacy-driven ICS de-escalation.8,9 Hegland et al reported ICS de-escalation for 22% of 141 eligible ambulatory patients with COPD on triple inhaled therapy following pharmacist appointments.8 A study by Hahn et al resulted in 63.8% of 58 patients with COPD being maintained off ICS following a pharmacist de-escalation initiative.9 However, these studies relied upon more time-consuming de-escalation interventions, including at least 1 phone, video, or in-person patient visit.8,9

This project used a single chart review and templated progress note to recommend ICS de-escalation and achieved similar or improved de-escalation rates compared to previous studies.8,9 Previous studies were conducted prior to the updated 2023 GOLD guidelines for COPD which no longer recommend LABA + ICS therapy. This project addressed ICS de-escalation in patients on LABA + ICS therapy in addition to those on triple inhaled therapy. Additionally, previous studies did not address rates of moderate to severe COPD exacerbation and adverse events to ICS following the pharmacist intervention.8,9

This study included COPD exacerbations and cases of pneumonia or oral candidiasis as secondary outcomes to assess the safety and efficacy of the ICS de-escalation. It appeared there were similar or lower rates of COPD exacerbations, pneumonia, and oral candidiasis in those with de-escalated ICS therapy in this study. However, these secondary outcomes are exploratory and would need to be confirmed by larger studies powered to address these outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Pharmacist-driven ICS de-escalation may be an effective method for reducing ICS usage in veterans as seen in this study. Additional controlled studies are required to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pharmacist-driven ICS de-escalation.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2024 Report). Accessed October 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2025 Report). Accessed November 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/

- Rogliani P, Ritondo BL, Gabriele M, et al. Optimizing de-escalation of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a systematic review of real-world findings. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(9):977-990. doi:10.1080/17512433.2020.1817739

- Rossi A, Guerriero M, Corrado A; OPTIMO/AIPO Study Group. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res. 2014;15(1):77. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-15-77

- Anderson E, Wiener RS, Resnick K, et al. Care coordination for veterans with COPD: a positive deviance study. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):63-68. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42394

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2021. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/copd/

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Accessed October 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf

- Hegland AJ, Bolduc J, Jones L, Kunisaki KM, Melzer AC. Pharmacist-driven deprescribing of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(4):730-733. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-871RL

- Hahn NM, Nagy MW. Implementation of a targeted inhaled corticosteroid de-escalation process in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the primary care setting. Innov Pharm. 2022;13(1):10.24926/iip.v13i1.4349. doi:10.24926/iip.v13i1.4349

Systemic glucocorticoids play an important role in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations. They are recommended to shorten recovery time and increase forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) during exacerbations.1 However, the role of the chronic use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in the treatment of COPD is less clear.

When added to inhaled β-2 agonists and muscarinic antagonists, ICSs can decrease the risk of exacerbations.1 However, not all patients with COPD benefit from ICS therapy. The degree of benefit an ICS can provide has been shown to correlate with eosinophil count—a marker of inflammation. The expected benefit of using an ICS increases as the eosinophil count increases.1 Maximum benefit can be observed with eosinophil counts ≥ 300 cells/µL, and minimal benefit is observed with eosinophil counts < 100 cells/µL. Adverse effects (AEs) of ICSs include a hoarse voice, oral candidiasis, and an increased risk of pneumonia.1 Given the risk of AEs, it is important to limit ICS use in patients who are unlikely to reap any benefits.

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines suggest the use of ICSs in patients who experience exacerbations while using long-acting β agonist (LABA) plus long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) therapy and have an eosinophil count ≥ 100 cells/µL. Switching from LABA or LAMA monotherapy to triple therapy with LAMA/LABA/ICS may be considered if patients have continued exacerbations and an eosinophil count ≥ 300 cells/µL. De-escalation of ICS therapy should be considered if patients do not meet these criteria or if patients experience ICS AEs, such as pneumonia. The patients most likely to have increased exacerbations or decreased FEV1 with ICS withdrawal are those with eosinophil counts ≥ 300 cells/µL.1,2

Several studies have explored the effects of ICS de-escalation in real-world clinical settings. A systematic review of 11 studies indicated that de-escalation of ICS in COPD does not result in increased exacerbations.3 A prospective study by Rossi et al found that in a 6-month period, 141 of 482 patients on ICS therapy (29%) had an exacerbation. In the opposing arm of the study, 88 of 334 patients (26%) with deprescribed ICS experienced an exacerbation. The difference between these 2 groups was not statistically significant.4 The researchers concluded that in real-world practice, ICS withdrawal can be safe in patients at low risk of exacerbation.

About 25% of veterans (1.25 million) have been diagnosed with COPD.5 To address this, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and US Department of Defense published updated COPD guidelines in 2021 that specify criteria for de-escalation of ICS.6 Guidelines, however, may not be reflected in common clinical practice for several years following publication. The VA Academic Detailing Service (ADS) provides tools to help clinicians identify patients who may benefit from changes in treatment plans. A recent ADS focus was the implementation of a COPD dashboard, which identifies patients with COPD who are candidates for ICS de-escalation based on comorbid diagnoses, exacerbation history, and eosinophil count. VA pharmacists have an expanded role in the management of primary care disease states and are therefore well-positioned to increase adherence to guideline-directed therapy. The objective of this quality improvement project was to determine the impact of pharmacist-driven de-escalation on ICS usage in veterans with COPD.

Methods

This project was conducted in an outpatient clinic at the Robley Rex VA Medical Center beginning September 21, 2023, with a progress note in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Eligible patients were selected using the COPD Dashboard provided by ADS. The COPD Dashboard defined patients with COPD as those with ≥ 2 outpatient COPD diagnoses in the past 2 years, 1 inpatient discharge COPD diagnosis in the past year, or COPD listed as an active problem. COPD diagnoses were identified using International Statistical Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes

Candidates identified for ICS de-escalation by the dashboard were excluded if they had a history of COPD exacerbation in the previous 2 years. The dashboard identified COPD exacerbations via ICD-10 codes for COPD or acute respiratory failure for inpatient discharges, emergency department (ED) visits, urgent care visits, and community care consults with 1 of the following terms: emergency, inpatient, hospital, urgent, ED (self). The COPD dashboard excluded patients with a diagnosis of asthma.

After patients were selected, they were screened for additional exclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if a pulmonary care practitioner managed their COPD; if identified via an active pulmonary consult in CPRS; if a non-VA clinician prescribed their ICS; or if they were being treated with roflumilast, theophylline, or chronic azithromycin. Individuals taking these 3 drugs were excluded due to potential severe and/or refractory COPD. Patients also were excluded if they: (1) had prior ICS de-escalation failure (defined as a COPD exacerbation following ICS de-escalation that resulted in ICS resumption); (2) had a COPD exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids or antibiotics in the previous year; (3) had active lung cancer; (4) did not have any eosinophil levels in CPRS within the previous 2 years; or (5) had any eosinophil levels ≥ 300 cells/µL in the previous year.

Each patient who met the inclusion criteria and was not excluded received a focused medication review by a pharmacist who created a templated progress note, with patient-specific recommendations, that was entered in the CPRS (eAppendix). The recommendations were also attached as an addendum to the patient’s last primary care visit note, and the primary care practitioner (PCP) was alerted via CPRS to consider ICS de-escalation and non-ICS alternatives. Tapering of ICS therapy was offered as an option to de-escalate if abrupt discontinuation was deemed inappropriate. PCPs were also prompted to consider referral to a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist for management and follow-up of ICS de-escalation.

The primary outcome was the number of patients with de-escalated ICS at 3 and 6 months following the recommendation. Secondary outcomes included the number of: patients who were no longer prescribed an ICS or who had a non-ICS alternative initiated at a pharmacist’s recommendation; patients who were referred to a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist for ICS de-escalation; COPD exacerbations requiring systemic steroids or antibiotics, or requiring an ED visit, inpatient admission, or urgent-care clinic visit; and cases of pneumonia or oral candidiasis. Primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated via chart review in CPRS. For secondary outcomes of pneumonia and COPD exacerbation, identification was made by documented diagnosis in CPRS. For continuous data such as age, the mean was calculated.

Results

Pharmacist ICS de-escalation recommendations were made between September 21, 2023, and November 19, 2023, for 106 patients. The mean age was 72 years and 99 (93%) patients were male (Table 1). Forty-one (39%) of the patients used tobacco at the time of the study. FEV1 was available for 69 patients with a mean of 63% (GOLD grade 2).1 Based on FEV1 values, 16 patients had mild COPD (GOLD grade 1), 37 patients had moderate COPD (GOLD grade 2), 14 patients had severe COPD (GOLD grade 3), and 2 patients had very severe COPD (GOLD grade 4).1 Thirty-four patients received LABA + LAMA + ICS, 65 received LABA + ICS, 2 received LAMA + ICS, and 5 received ICS monotherapy. The most common dose of ICS was a moderate dose (Table 2). Only 2 patients had an ICS AE in the previous year.

ICS de-escalation recommendations resulted in ICS de-escalation in 50 (47.2%) and 62 (58.5%) patients at 3 and 6 months, respectively. The 6-month ICS de-escalation rate by ICS dose at baseline was 72.2% (high dose), 60.0% (moderate), and 30.8% (low). De-escalation at 6 months by GOLD grade at baseline was 56.3% (9 of 16 patients, GOLD 1), 64.9% (24 of 37 patients, GOLD 2), 50% (7 of 14 patients, GOLD 3), and 50% (1 of 2 patients, GOLD 4). Six months after the ICS de-escalation recommendation appeared in the CPRS, the percentage of patients on LABA + ICS therapy dropped from 65 patients (61.3%) at baseline to 25 patients (23.6%).

Secondary outcomes were assessed at 3 and 6 months following the recommendation. Most patients with de-escalated ICS had their ICS discontinued and a non-ICS alternative initiated per pharmacist recommendations. At 6 months, 39 patients (36.8%) patients were referred to a patient aligned care team (PACT) pharmacist for de-escalation. Of the 39 patients referred to pharmacists, 69.2% (27 patients) were de-escalated; this compared to 52.2% (35 patients) who were not referred to pharmacists (Table 3).

ICS use increases the risk of pneumonia.1 At 6 months, 11 patients were diagnosed with pneumonia; 3 patients were diagnosed with pneumonia twice, resulting in a total of 14 cases. Ten cases occurred while patients were on ICS and 4 cases occurred following ICS de-escalation. One patient had a documented case of oral candidiasis that occurred while on ICS therapy; no patients with discontinued ICS were diagnosed with oral candidiasis. In addition, 10 patients had COPD exacerbations; however no patients had exacerbations both before and after de-escalation. Six patients were on ICS therapy when they experienced an exacerbation, and 4 patients had an exacerbation after ICS de-escalation.

Discussion

More than half of patients receiving the pharmacist intervention achieved the primary outcome of ICS de-escalation at 6 months. Furthermore, a larger percentage of patients referred to pharmacists for the management of ICS de-escalation successfully achieved de-escalation compared to those who were not referred. These outcomes reflect the important role pharmacists can play in identifying appropriate candidates for ICS de-escalation and assisting in the management of ICS de-escalation. Patients referred to pharmacists also received other services such as smoking cessation pharmacotherapy and counseling on inhaler technique and adherence. These interventions can support improved COPD clinical outcomes.

The purpose of de-escalating ICS therapy is to reduce the risk of AEs such as pneumonia and oral candidiasis.1 The secondary outcomes of this study support previous evidence that patients who have de-escalated ICS therapy may have reduced risk of AEs compared to those who remain on ICS therapy.3 Specifically, of the 14 cases of pneumonia that occurred during the study, 10 cases occurred while patients were on ICS and 4 cases occurred following ICS de-escalation.

ICS de-escalation may increase risk of increased COPD exacerbations.1 However, the secondary outcomes of this study do not indicate that those with de-escalated ICS had more COPD exacerbations compared to those who continued on ICS. Pharmacists’ recommendations were more effective for patients with less severe COPD based on baseline FEV1.

The previous GOLD Guidelines for COPD suggested LABA + ICS therapy as an option for patients with a high symptom and exacerbation burden (previously known as GOLD Group D). Guidelines no longer recommend LABA + ICS therapy due to the superiority of triple inhaled therapy for exacerbations and the superiority of LAMA + LABA therapy for dyspnea.7 A majority of identified patients in this project were on LABA + ICS therapy alone at baseline. The ICS de-escalation recommendation resulted in a 61.5% reduction in patients on LABA + ICS therapy at 6 months. By decreasing the number of patients on LABA + ICS without LAMA, recommendations increased the number of patients on guideline-directed therapy.

Limitations

This study lacked a control group, and the rate of ICS de-escalation in patients who did not receive a pharmacist recommendation was not assessed. Therefore, it could not be determined whether the pharmacist recommendation is more effective than no recommendation. Another limitation was our inability to access records from non-VA health care facilities. This may have resulted in missed COPD exacerbations, pneumonia, and oral candidiasis prior to or following the pharmacist recommendation.

In addition, the method used to notify PCPs of the pharmacist recommendation was a CPRS alert. Clinicians often receive multiple daily alerts and may not always pay close attention to them due to alert fatigue. Early in the study, some PCPs were unknowingly omitted from the alert of the pharmacist recommendation for 10 patients due to human error. For 8 of these 10 patients, the PCP was notified of the recommendations during the 3-month follow-up period. However, 2 patients had COPD exacerbations during the 3-month follow-up period. In these cases, the PCP was not alerted to de-escalate ICS. The data for these patients were collected at 3 and 6 months in the same manner as all other patients. Also, 7 of 35 patients who were referred to a pharmacist for ICS de-escalation did not have a scheduled appointment. These patients were considered to be lost to follow-up and this may have resulted in an underestimation of the ability of pharmacists to successfully de-escalate ICS in patients with COPD.

Other studies have evaluated the efficacy of a pharmacy-driven ICS de-escalation.8,9 Hegland et al reported ICS de-escalation for 22% of 141 eligible ambulatory patients with COPD on triple inhaled therapy following pharmacist appointments.8 A study by Hahn et al resulted in 63.8% of 58 patients with COPD being maintained off ICS following a pharmacist de-escalation initiative.9 However, these studies relied upon more time-consuming de-escalation interventions, including at least 1 phone, video, or in-person patient visit.8,9

This project used a single chart review and templated progress note to recommend ICS de-escalation and achieved similar or improved de-escalation rates compared to previous studies.8,9 Previous studies were conducted prior to the updated 2023 GOLD guidelines for COPD which no longer recommend LABA + ICS therapy. This project addressed ICS de-escalation in patients on LABA + ICS therapy in addition to those on triple inhaled therapy. Additionally, previous studies did not address rates of moderate to severe COPD exacerbation and adverse events to ICS following the pharmacist intervention.8,9

This study included COPD exacerbations and cases of pneumonia or oral candidiasis as secondary outcomes to assess the safety and efficacy of the ICS de-escalation. It appeared there were similar or lower rates of COPD exacerbations, pneumonia, and oral candidiasis in those with de-escalated ICS therapy in this study. However, these secondary outcomes are exploratory and would need to be confirmed by larger studies powered to address these outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Pharmacist-driven ICS de-escalation may be an effective method for reducing ICS usage in veterans as seen in this study. Additional controlled studies are required to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pharmacist-driven ICS de-escalation.

Systemic glucocorticoids play an important role in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations. They are recommended to shorten recovery time and increase forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) during exacerbations.1 However, the role of the chronic use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in the treatment of COPD is less clear.

When added to inhaled β-2 agonists and muscarinic antagonists, ICSs can decrease the risk of exacerbations.1 However, not all patients with COPD benefit from ICS therapy. The degree of benefit an ICS can provide has been shown to correlate with eosinophil count—a marker of inflammation. The expected benefit of using an ICS increases as the eosinophil count increases.1 Maximum benefit can be observed with eosinophil counts ≥ 300 cells/µL, and minimal benefit is observed with eosinophil counts < 100 cells/µL. Adverse effects (AEs) of ICSs include a hoarse voice, oral candidiasis, and an increased risk of pneumonia.1 Given the risk of AEs, it is important to limit ICS use in patients who are unlikely to reap any benefits.

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines suggest the use of ICSs in patients who experience exacerbations while using long-acting β agonist (LABA) plus long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) therapy and have an eosinophil count ≥ 100 cells/µL. Switching from LABA or LAMA monotherapy to triple therapy with LAMA/LABA/ICS may be considered if patients have continued exacerbations and an eosinophil count ≥ 300 cells/µL. De-escalation of ICS therapy should be considered if patients do not meet these criteria or if patients experience ICS AEs, such as pneumonia. The patients most likely to have increased exacerbations or decreased FEV1 with ICS withdrawal are those with eosinophil counts ≥ 300 cells/µL.1,2

Several studies have explored the effects of ICS de-escalation in real-world clinical settings. A systematic review of 11 studies indicated that de-escalation of ICS in COPD does not result in increased exacerbations.3 A prospective study by Rossi et al found that in a 6-month period, 141 of 482 patients on ICS therapy (29%) had an exacerbation. In the opposing arm of the study, 88 of 334 patients (26%) with deprescribed ICS experienced an exacerbation. The difference between these 2 groups was not statistically significant.4 The researchers concluded that in real-world practice, ICS withdrawal can be safe in patients at low risk of exacerbation.

About 25% of veterans (1.25 million) have been diagnosed with COPD.5 To address this, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and US Department of Defense published updated COPD guidelines in 2021 that specify criteria for de-escalation of ICS.6 Guidelines, however, may not be reflected in common clinical practice for several years following publication. The VA Academic Detailing Service (ADS) provides tools to help clinicians identify patients who may benefit from changes in treatment plans. A recent ADS focus was the implementation of a COPD dashboard, which identifies patients with COPD who are candidates for ICS de-escalation based on comorbid diagnoses, exacerbation history, and eosinophil count. VA pharmacists have an expanded role in the management of primary care disease states and are therefore well-positioned to increase adherence to guideline-directed therapy. The objective of this quality improvement project was to determine the impact of pharmacist-driven de-escalation on ICS usage in veterans with COPD.

Methods

This project was conducted in an outpatient clinic at the Robley Rex VA Medical Center beginning September 21, 2023, with a progress note in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Eligible patients were selected using the COPD Dashboard provided by ADS. The COPD Dashboard defined patients with COPD as those with ≥ 2 outpatient COPD diagnoses in the past 2 years, 1 inpatient discharge COPD diagnosis in the past year, or COPD listed as an active problem. COPD diagnoses were identified using International Statistical Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes

Candidates identified for ICS de-escalation by the dashboard were excluded if they had a history of COPD exacerbation in the previous 2 years. The dashboard identified COPD exacerbations via ICD-10 codes for COPD or acute respiratory failure for inpatient discharges, emergency department (ED) visits, urgent care visits, and community care consults with 1 of the following terms: emergency, inpatient, hospital, urgent, ED (self). The COPD dashboard excluded patients with a diagnosis of asthma.

After patients were selected, they were screened for additional exclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if a pulmonary care practitioner managed their COPD; if identified via an active pulmonary consult in CPRS; if a non-VA clinician prescribed their ICS; or if they were being treated with roflumilast, theophylline, or chronic azithromycin. Individuals taking these 3 drugs were excluded due to potential severe and/or refractory COPD. Patients also were excluded if they: (1) had prior ICS de-escalation failure (defined as a COPD exacerbation following ICS de-escalation that resulted in ICS resumption); (2) had a COPD exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids or antibiotics in the previous year; (3) had active lung cancer; (4) did not have any eosinophil levels in CPRS within the previous 2 years; or (5) had any eosinophil levels ≥ 300 cells/µL in the previous year.

Each patient who met the inclusion criteria and was not excluded received a focused medication review by a pharmacist who created a templated progress note, with patient-specific recommendations, that was entered in the CPRS (eAppendix). The recommendations were also attached as an addendum to the patient’s last primary care visit note, and the primary care practitioner (PCP) was alerted via CPRS to consider ICS de-escalation and non-ICS alternatives. Tapering of ICS therapy was offered as an option to de-escalate if abrupt discontinuation was deemed inappropriate. PCPs were also prompted to consider referral to a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist for management and follow-up of ICS de-escalation.

The primary outcome was the number of patients with de-escalated ICS at 3 and 6 months following the recommendation. Secondary outcomes included the number of: patients who were no longer prescribed an ICS or who had a non-ICS alternative initiated at a pharmacist’s recommendation; patients who were referred to a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist for ICS de-escalation; COPD exacerbations requiring systemic steroids or antibiotics, or requiring an ED visit, inpatient admission, or urgent-care clinic visit; and cases of pneumonia or oral candidiasis. Primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated via chart review in CPRS. For secondary outcomes of pneumonia and COPD exacerbation, identification was made by documented diagnosis in CPRS. For continuous data such as age, the mean was calculated.

Results

Pharmacist ICS de-escalation recommendations were made between September 21, 2023, and November 19, 2023, for 106 patients. The mean age was 72 years and 99 (93%) patients were male (Table 1). Forty-one (39%) of the patients used tobacco at the time of the study. FEV1 was available for 69 patients with a mean of 63% (GOLD grade 2).1 Based on FEV1 values, 16 patients had mild COPD (GOLD grade 1), 37 patients had moderate COPD (GOLD grade 2), 14 patients had severe COPD (GOLD grade 3), and 2 patients had very severe COPD (GOLD grade 4).1 Thirty-four patients received LABA + LAMA + ICS, 65 received LABA + ICS, 2 received LAMA + ICS, and 5 received ICS monotherapy. The most common dose of ICS was a moderate dose (Table 2). Only 2 patients had an ICS AE in the previous year.

ICS de-escalation recommendations resulted in ICS de-escalation in 50 (47.2%) and 62 (58.5%) patients at 3 and 6 months, respectively. The 6-month ICS de-escalation rate by ICS dose at baseline was 72.2% (high dose), 60.0% (moderate), and 30.8% (low). De-escalation at 6 months by GOLD grade at baseline was 56.3% (9 of 16 patients, GOLD 1), 64.9% (24 of 37 patients, GOLD 2), 50% (7 of 14 patients, GOLD 3), and 50% (1 of 2 patients, GOLD 4). Six months after the ICS de-escalation recommendation appeared in the CPRS, the percentage of patients on LABA + ICS therapy dropped from 65 patients (61.3%) at baseline to 25 patients (23.6%).

Secondary outcomes were assessed at 3 and 6 months following the recommendation. Most patients with de-escalated ICS had their ICS discontinued and a non-ICS alternative initiated per pharmacist recommendations. At 6 months, 39 patients (36.8%) patients were referred to a patient aligned care team (PACT) pharmacist for de-escalation. Of the 39 patients referred to pharmacists, 69.2% (27 patients) were de-escalated; this compared to 52.2% (35 patients) who were not referred to pharmacists (Table 3).

ICS use increases the risk of pneumonia.1 At 6 months, 11 patients were diagnosed with pneumonia; 3 patients were diagnosed with pneumonia twice, resulting in a total of 14 cases. Ten cases occurred while patients were on ICS and 4 cases occurred following ICS de-escalation. One patient had a documented case of oral candidiasis that occurred while on ICS therapy; no patients with discontinued ICS were diagnosed with oral candidiasis. In addition, 10 patients had COPD exacerbations; however no patients had exacerbations both before and after de-escalation. Six patients were on ICS therapy when they experienced an exacerbation, and 4 patients had an exacerbation after ICS de-escalation.

Discussion

More than half of patients receiving the pharmacist intervention achieved the primary outcome of ICS de-escalation at 6 months. Furthermore, a larger percentage of patients referred to pharmacists for the management of ICS de-escalation successfully achieved de-escalation compared to those who were not referred. These outcomes reflect the important role pharmacists can play in identifying appropriate candidates for ICS de-escalation and assisting in the management of ICS de-escalation. Patients referred to pharmacists also received other services such as smoking cessation pharmacotherapy and counseling on inhaler technique and adherence. These interventions can support improved COPD clinical outcomes.

The purpose of de-escalating ICS therapy is to reduce the risk of AEs such as pneumonia and oral candidiasis.1 The secondary outcomes of this study support previous evidence that patients who have de-escalated ICS therapy may have reduced risk of AEs compared to those who remain on ICS therapy.3 Specifically, of the 14 cases of pneumonia that occurred during the study, 10 cases occurred while patients were on ICS and 4 cases occurred following ICS de-escalation.

ICS de-escalation may increase risk of increased COPD exacerbations.1 However, the secondary outcomes of this study do not indicate that those with de-escalated ICS had more COPD exacerbations compared to those who continued on ICS. Pharmacists’ recommendations were more effective for patients with less severe COPD based on baseline FEV1.

The previous GOLD Guidelines for COPD suggested LABA + ICS therapy as an option for patients with a high symptom and exacerbation burden (previously known as GOLD Group D). Guidelines no longer recommend LABA + ICS therapy due to the superiority of triple inhaled therapy for exacerbations and the superiority of LAMA + LABA therapy for dyspnea.7 A majority of identified patients in this project were on LABA + ICS therapy alone at baseline. The ICS de-escalation recommendation resulted in a 61.5% reduction in patients on LABA + ICS therapy at 6 months. By decreasing the number of patients on LABA + ICS without LAMA, recommendations increased the number of patients on guideline-directed therapy.

Limitations

This study lacked a control group, and the rate of ICS de-escalation in patients who did not receive a pharmacist recommendation was not assessed. Therefore, it could not be determined whether the pharmacist recommendation is more effective than no recommendation. Another limitation was our inability to access records from non-VA health care facilities. This may have resulted in missed COPD exacerbations, pneumonia, and oral candidiasis prior to or following the pharmacist recommendation.

In addition, the method used to notify PCPs of the pharmacist recommendation was a CPRS alert. Clinicians often receive multiple daily alerts and may not always pay close attention to them due to alert fatigue. Early in the study, some PCPs were unknowingly omitted from the alert of the pharmacist recommendation for 10 patients due to human error. For 8 of these 10 patients, the PCP was notified of the recommendations during the 3-month follow-up period. However, 2 patients had COPD exacerbations during the 3-month follow-up period. In these cases, the PCP was not alerted to de-escalate ICS. The data for these patients were collected at 3 and 6 months in the same manner as all other patients. Also, 7 of 35 patients who were referred to a pharmacist for ICS de-escalation did not have a scheduled appointment. These patients were considered to be lost to follow-up and this may have resulted in an underestimation of the ability of pharmacists to successfully de-escalate ICS in patients with COPD.

Other studies have evaluated the efficacy of a pharmacy-driven ICS de-escalation.8,9 Hegland et al reported ICS de-escalation for 22% of 141 eligible ambulatory patients with COPD on triple inhaled therapy following pharmacist appointments.8 A study by Hahn et al resulted in 63.8% of 58 patients with COPD being maintained off ICS following a pharmacist de-escalation initiative.9 However, these studies relied upon more time-consuming de-escalation interventions, including at least 1 phone, video, or in-person patient visit.8,9

This project used a single chart review and templated progress note to recommend ICS de-escalation and achieved similar or improved de-escalation rates compared to previous studies.8,9 Previous studies were conducted prior to the updated 2023 GOLD guidelines for COPD which no longer recommend LABA + ICS therapy. This project addressed ICS de-escalation in patients on LABA + ICS therapy in addition to those on triple inhaled therapy. Additionally, previous studies did not address rates of moderate to severe COPD exacerbation and adverse events to ICS following the pharmacist intervention.8,9

This study included COPD exacerbations and cases of pneumonia or oral candidiasis as secondary outcomes to assess the safety and efficacy of the ICS de-escalation. It appeared there were similar or lower rates of COPD exacerbations, pneumonia, and oral candidiasis in those with de-escalated ICS therapy in this study. However, these secondary outcomes are exploratory and would need to be confirmed by larger studies powered to address these outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Pharmacist-driven ICS de-escalation may be an effective method for reducing ICS usage in veterans as seen in this study. Additional controlled studies are required to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pharmacist-driven ICS de-escalation.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2024 Report). Accessed October 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2025 Report). Accessed November 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/

- Rogliani P, Ritondo BL, Gabriele M, et al. Optimizing de-escalation of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a systematic review of real-world findings. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(9):977-990. doi:10.1080/17512433.2020.1817739

- Rossi A, Guerriero M, Corrado A; OPTIMO/AIPO Study Group. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res. 2014;15(1):77. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-15-77

- Anderson E, Wiener RS, Resnick K, et al. Care coordination for veterans with COPD: a positive deviance study. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):63-68. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42394

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2021. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/copd/

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Accessed October 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf

- Hegland AJ, Bolduc J, Jones L, Kunisaki KM, Melzer AC. Pharmacist-driven deprescribing of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(4):730-733. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-871RL

- Hahn NM, Nagy MW. Implementation of a targeted inhaled corticosteroid de-escalation process in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the primary care setting. Innov Pharm. 2022;13(1):10.24926/iip.v13i1.4349. doi:10.24926/iip.v13i1.4349

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2024 Report). Accessed October 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2025 Report). Accessed November 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/

- Rogliani P, Ritondo BL, Gabriele M, et al. Optimizing de-escalation of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a systematic review of real-world findings. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(9):977-990. doi:10.1080/17512433.2020.1817739

- Rossi A, Guerriero M, Corrado A; OPTIMO/AIPO Study Group. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res. 2014;15(1):77. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-15-77

- Anderson E, Wiener RS, Resnick K, et al. Care coordination for veterans with COPD: a positive deviance study. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):63-68. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42394

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2021. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/copd/

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Accessed October 14, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf

- Hegland AJ, Bolduc J, Jones L, Kunisaki KM, Melzer AC. Pharmacist-driven deprescribing of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(4):730-733. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-871RL

- Hahn NM, Nagy MW. Implementation of a targeted inhaled corticosteroid de-escalation process in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the primary care setting. Innov Pharm. 2022;13(1):10.24926/iip.v13i1.4349. doi:10.24926/iip.v13i1.4349

Evaluation of Pharmacist-Driven Inhaled Corticosteroid De-escalation in Veterans

Evaluation of Pharmacist-Driven Inhaled Corticosteroid De-escalation in Veterans