User login

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

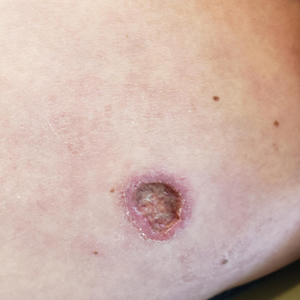

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

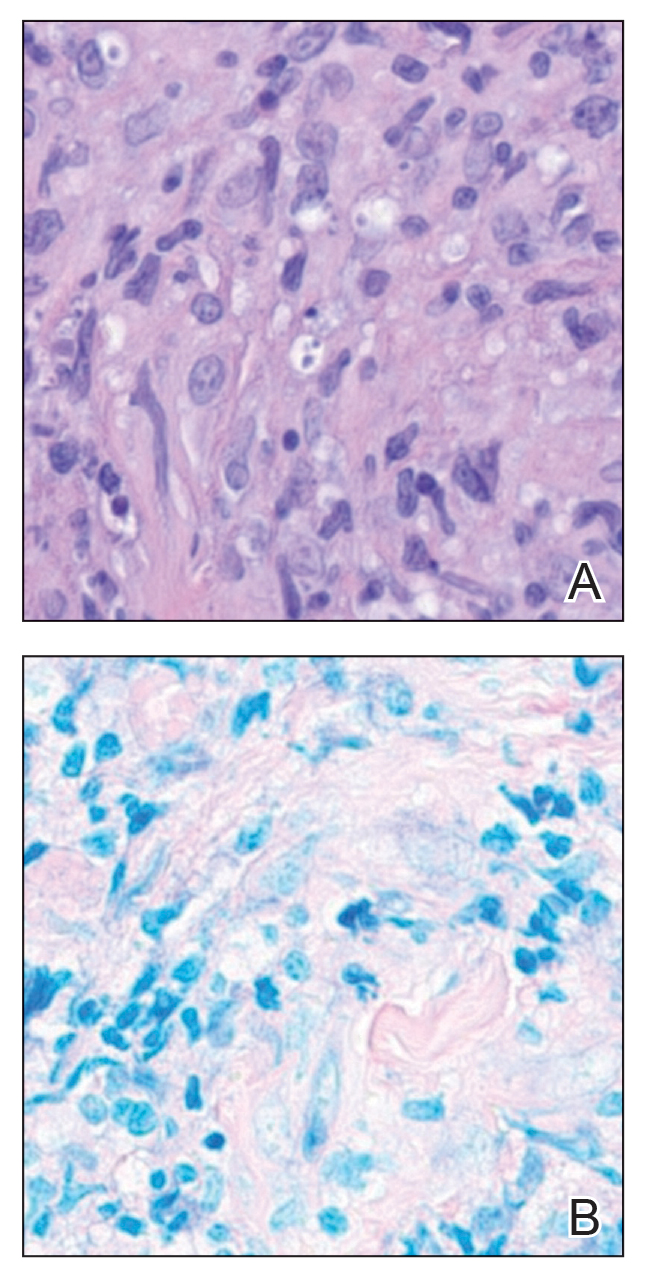

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

A 43-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with widespread scaly plaques and ulcerations of 2 months’ duration. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. The patient reported that the eruption began after returning from a vacation to Costa Rica, during which she spent time on the beach and white-water rafting. She noted that she had been exposed to numerous insects during her trip, and that her roommate, who had accompanied her, had similar exposure history and lesions. The plaques were refractory to multiple oral antibiotics previously prescribed by primary care. Physical examination revealed submental lymphadenopathy and painless ulcerations with indurated borders without purulent drainage alongside scattered scaly papules and plaques on the face, neck, arms, and legs. A biopsy was taken from an ulceration edge on the left thigh.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Lepromatous Leprosy

The Diagnosis: Lepromatous Leprosy

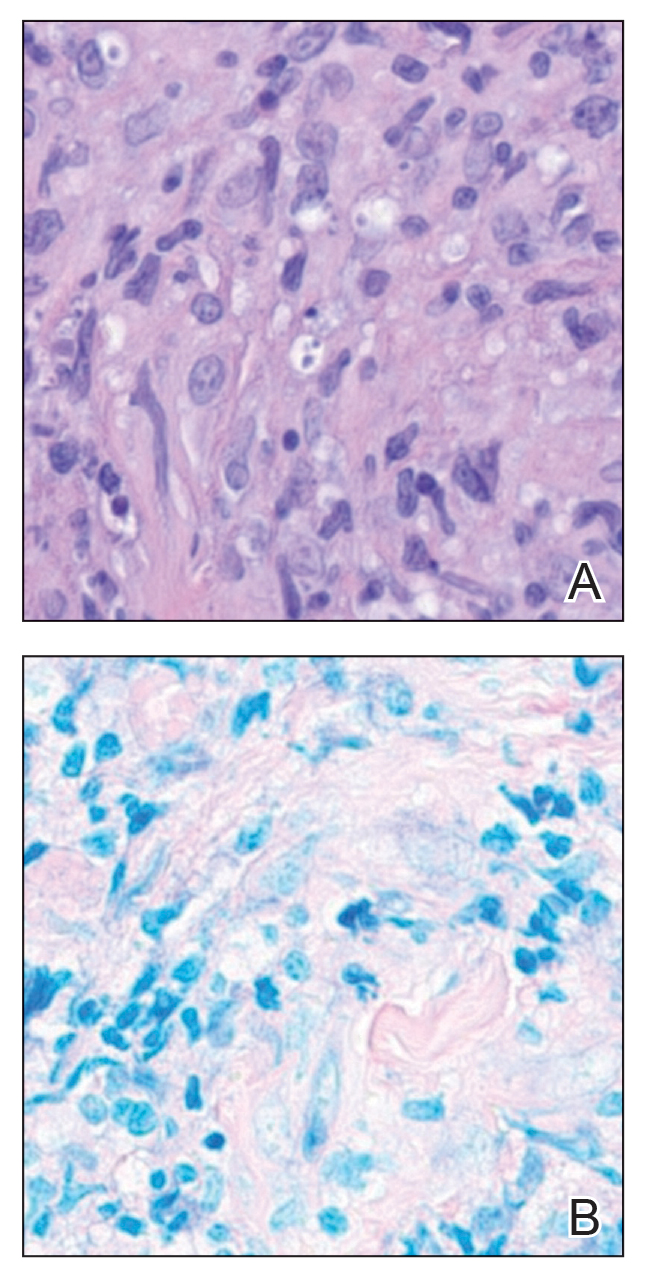

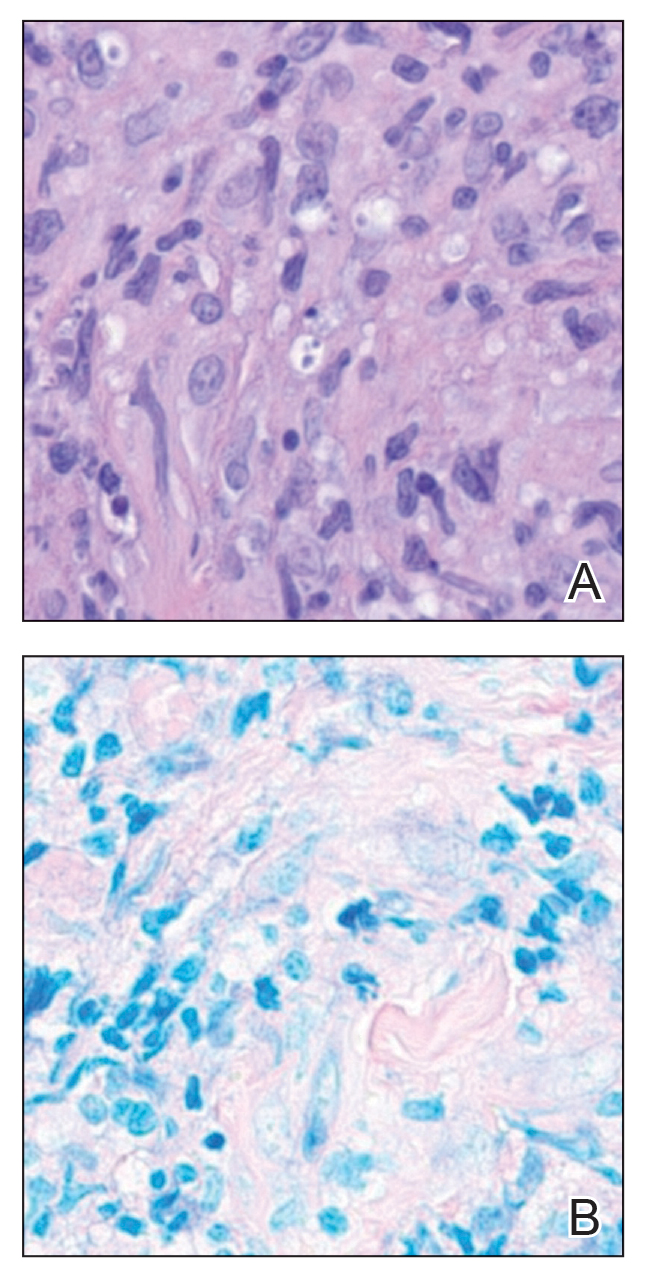

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen (Figures 1 and 2) disclosed a grenz zone and a diffuse infiltrative process beneath a normal-appearing epidermis. Higher-power examination revealed areas containing macrophages (Virchow cells) with cloudy regions devoid of nuclei (globi). Fite stain demonstrated numerous intracytoplasmic acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Laboratory test results for rapid plasma reagin and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, and a complete blood cell count was normal.

On further questioning the patient revealed he was an immigrant from Micronesia, and he described decreased sensation and numbness in the lesions that had been present from onset. Physical examination was consistent with this history and revealed hypoesthesia of the lesions, particularly over the central aspect of the depigmented macules. Based on the clinical examination and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made.

Therapy with rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone was initiated. Unfortunately, compliance was poor, and at clinic follow-up 10 months later the patient demonstrated formation of new indurated lesions as well as mild eyelid swelling and edema of the hands thought to be consistent with erythema nodosum leprosum. Prednisone was then initiated and the dose of clofazimine was increased from 50 mg daily to 100 mg daily with excellent clinical response.

Mycobacterium leprae is a small, slightly curved rod that is an acid-fast, obligate, intracellular organism. It remains endemic in Brazil and Southeast Asia but may present outside of these areas secondary to immigration.1

Hallmarks of the disease are anesthetic skin or mucous membrane lesions with thickened peripheral nerves.2 It grows best at 27°C to 33°C, thereby affecting cooler areas of the human body such as earlobes, knees, and distal extremities.3 It is most likely spread by aerosolized respiratory droplets and less commonly by direct contact. There have been reports suggesting transmission via armadillos.4

Genetic susceptibility influences the development of leprosy, while HLA type influences the immune response and hence the type of leprosy.5 Ridley and Jopling6 devised a classification system based on the immunologic response to M leprae. Highly reactive hosts with a vigorous cell-mediated response to M leprae develop tuberculoid leprosy and exhibit few skin lesions containing rare organisms. In contrast, anergic hosts develop lepromatous leprosy, characterized by multiple skin lesions, abundant organisms, and diffuse disease. Borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous make up the middle of the spectrum.6-9 Skin lesions can present with poorly defined, hypopigmented macules of indeterminate leprosy on one end and diffuse skin involvement of lepromatous leprosy on the opposite end. Diffuse involvement includes facial skin thickening, classic leonine facies, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, anesthetic lesions, and anhidrosis.

Erythema nodosum leprosum occurs with chronic infection from M leprae, most commonly lepromatous leprosy. Immune complex deposition results in vasculitis and inflammatory foci. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to high antigen load released by dying mycobacteria, causing secretion of tumor necrosis factor a from macrophages.1 Erythema nodosum leprosum demonstrates rapid onset of tender erythematous plaques or nodules, most commonly on the face and extensor surfaces of the extremities, with fever, malaise, iritis, arthralgia, and orchitis. Clofazimine therapy probably decreases the occurence.1 Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and/or thalidomide.

- Moschella S, Ooi W. Update on leprosy in immigrants in the United States: status in the year 2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:930-937.

- Abraham S, Job C, Joseph G, et al. Epidemiological significance of first skin lesion in leprosy. Int J Lep Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:131-139.

- Shepard C. The experimental disease that follows the injection of human bacilli into footpads of mice. J Exp Med. 1960;112:445-454.

- Leprosy: global target attained. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2001;20:155-156.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation, 2005. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:289-295.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. A classification of leprosy for research purposes. Lepr Rev. 1962;33:119-128.

- Lane J. Borderline tuberculoid leprosy in a woman from the state of Georgia with armadillo exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:714-716.

- Fitness J, Tosh K, Hill AV. Genetics of susceptibility to leprosy. Genes Immun. 2002;3:441-453.

- Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:417-426.

The Diagnosis: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen (Figures 1 and 2) disclosed a grenz zone and a diffuse infiltrative process beneath a normal-appearing epidermis. Higher-power examination revealed areas containing macrophages (Virchow cells) with cloudy regions devoid of nuclei (globi). Fite stain demonstrated numerous intracytoplasmic acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Laboratory test results for rapid plasma reagin and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, and a complete blood cell count was normal.

On further questioning the patient revealed he was an immigrant from Micronesia, and he described decreased sensation and numbness in the lesions that had been present from onset. Physical examination was consistent with this history and revealed hypoesthesia of the lesions, particularly over the central aspect of the depigmented macules. Based on the clinical examination and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made.

Therapy with rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone was initiated. Unfortunately, compliance was poor, and at clinic follow-up 10 months later the patient demonstrated formation of new indurated lesions as well as mild eyelid swelling and edema of the hands thought to be consistent with erythema nodosum leprosum. Prednisone was then initiated and the dose of clofazimine was increased from 50 mg daily to 100 mg daily with excellent clinical response.

Mycobacterium leprae is a small, slightly curved rod that is an acid-fast, obligate, intracellular organism. It remains endemic in Brazil and Southeast Asia but may present outside of these areas secondary to immigration.1

Hallmarks of the disease are anesthetic skin or mucous membrane lesions with thickened peripheral nerves.2 It grows best at 27°C to 33°C, thereby affecting cooler areas of the human body such as earlobes, knees, and distal extremities.3 It is most likely spread by aerosolized respiratory droplets and less commonly by direct contact. There have been reports suggesting transmission via armadillos.4

Genetic susceptibility influences the development of leprosy, while HLA type influences the immune response and hence the type of leprosy.5 Ridley and Jopling6 devised a classification system based on the immunologic response to M leprae. Highly reactive hosts with a vigorous cell-mediated response to M leprae develop tuberculoid leprosy and exhibit few skin lesions containing rare organisms. In contrast, anergic hosts develop lepromatous leprosy, characterized by multiple skin lesions, abundant organisms, and diffuse disease. Borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous make up the middle of the spectrum.6-9 Skin lesions can present with poorly defined, hypopigmented macules of indeterminate leprosy on one end and diffuse skin involvement of lepromatous leprosy on the opposite end. Diffuse involvement includes facial skin thickening, classic leonine facies, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, anesthetic lesions, and anhidrosis.

Erythema nodosum leprosum occurs with chronic infection from M leprae, most commonly lepromatous leprosy. Immune complex deposition results in vasculitis and inflammatory foci. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to high antigen load released by dying mycobacteria, causing secretion of tumor necrosis factor a from macrophages.1 Erythema nodosum leprosum demonstrates rapid onset of tender erythematous plaques or nodules, most commonly on the face and extensor surfaces of the extremities, with fever, malaise, iritis, arthralgia, and orchitis. Clofazimine therapy probably decreases the occurence.1 Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and/or thalidomide.

The Diagnosis: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen (Figures 1 and 2) disclosed a grenz zone and a diffuse infiltrative process beneath a normal-appearing epidermis. Higher-power examination revealed areas containing macrophages (Virchow cells) with cloudy regions devoid of nuclei (globi). Fite stain demonstrated numerous intracytoplasmic acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Laboratory test results for rapid plasma reagin and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, and a complete blood cell count was normal.

On further questioning the patient revealed he was an immigrant from Micronesia, and he described decreased sensation and numbness in the lesions that had been present from onset. Physical examination was consistent with this history and revealed hypoesthesia of the lesions, particularly over the central aspect of the depigmented macules. Based on the clinical examination and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made.

Therapy with rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone was initiated. Unfortunately, compliance was poor, and at clinic follow-up 10 months later the patient demonstrated formation of new indurated lesions as well as mild eyelid swelling and edema of the hands thought to be consistent with erythema nodosum leprosum. Prednisone was then initiated and the dose of clofazimine was increased from 50 mg daily to 100 mg daily with excellent clinical response.

Mycobacterium leprae is a small, slightly curved rod that is an acid-fast, obligate, intracellular organism. It remains endemic in Brazil and Southeast Asia but may present outside of these areas secondary to immigration.1

Hallmarks of the disease are anesthetic skin or mucous membrane lesions with thickened peripheral nerves.2 It grows best at 27°C to 33°C, thereby affecting cooler areas of the human body such as earlobes, knees, and distal extremities.3 It is most likely spread by aerosolized respiratory droplets and less commonly by direct contact. There have been reports suggesting transmission via armadillos.4

Genetic susceptibility influences the development of leprosy, while HLA type influences the immune response and hence the type of leprosy.5 Ridley and Jopling6 devised a classification system based on the immunologic response to M leprae. Highly reactive hosts with a vigorous cell-mediated response to M leprae develop tuberculoid leprosy and exhibit few skin lesions containing rare organisms. In contrast, anergic hosts develop lepromatous leprosy, characterized by multiple skin lesions, abundant organisms, and diffuse disease. Borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous make up the middle of the spectrum.6-9 Skin lesions can present with poorly defined, hypopigmented macules of indeterminate leprosy on one end and diffuse skin involvement of lepromatous leprosy on the opposite end. Diffuse involvement includes facial skin thickening, classic leonine facies, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, anesthetic lesions, and anhidrosis.

Erythema nodosum leprosum occurs with chronic infection from M leprae, most commonly lepromatous leprosy. Immune complex deposition results in vasculitis and inflammatory foci. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to high antigen load released by dying mycobacteria, causing secretion of tumor necrosis factor a from macrophages.1 Erythema nodosum leprosum demonstrates rapid onset of tender erythematous plaques or nodules, most commonly on the face and extensor surfaces of the extremities, with fever, malaise, iritis, arthralgia, and orchitis. Clofazimine therapy probably decreases the occurence.1 Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and/or thalidomide.

- Moschella S, Ooi W. Update on leprosy in immigrants in the United States: status in the year 2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:930-937.

- Abraham S, Job C, Joseph G, et al. Epidemiological significance of first skin lesion in leprosy. Int J Lep Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:131-139.

- Shepard C. The experimental disease that follows the injection of human bacilli into footpads of mice. J Exp Med. 1960;112:445-454.

- Leprosy: global target attained. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2001;20:155-156.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation, 2005. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:289-295.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. A classification of leprosy for research purposes. Lepr Rev. 1962;33:119-128.

- Lane J. Borderline tuberculoid leprosy in a woman from the state of Georgia with armadillo exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:714-716.

- Fitness J, Tosh K, Hill AV. Genetics of susceptibility to leprosy. Genes Immun. 2002;3:441-453.

- Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:417-426.

- Moschella S, Ooi W. Update on leprosy in immigrants in the United States: status in the year 2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:930-937.

- Abraham S, Job C, Joseph G, et al. Epidemiological significance of first skin lesion in leprosy. Int J Lep Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:131-139.

- Shepard C. The experimental disease that follows the injection of human bacilli into footpads of mice. J Exp Med. 1960;112:445-454.

- Leprosy: global target attained. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2001;20:155-156.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation, 2005. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:289-295.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. A classification of leprosy for research purposes. Lepr Rev. 1962;33:119-128.

- Lane J. Borderline tuberculoid leprosy in a woman from the state of Georgia with armadillo exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:714-716.

- Fitness J, Tosh K, Hill AV. Genetics of susceptibility to leprosy. Genes Immun. 2002;3:441-453.

- Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:417-426.

A 37-year-old man presented with pruritic lesions over the arms, legs, face, and back of 4 months’ duration that had been refractory to topical steroid treatment. He reported a 15-lb weight loss that he attributed to recent intranasal cocaine use. His medical history revealed obesity. There was no known history of sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus infection, tuberculosis, diabetes mellitus, or intravenous drug use. Physical examination revealed small nodules over the pinnae, plaques on the forehead, and large plaques with depigmented macules of variable sizes over the extremities and back. Some lesions on the extremities were violaceous in appearance, while others on the upper extremities had raised borders.