User login

Leadership & Professional Development: Engaging Patients as Stakeholders

“Nothing about us without us” (Latin: ”Nihil de nobis, sine nobis”)

Hospitalists are at the forefront of decisions, innovations, and system-improvement projects that impact hospitalized patients. However, many of our decisions—while centered on patient care—fail to include their perspectives or views.

In his book Total Leadership, Stewart Friedman describes the importance of identifying and engaging key stakeholders.1 Friedman exhorts leaders to engage stakeholders in conversations to “confirm or correct your current understanding of stakeholder expectations.” In other words, instead of assuming what stakeholders want, ask and verify before proceeding.

Although hospitalists frequently include stakeholders such as nurses, pharmacists, and therapists in system-improvement initiatives, engaging patients is less common.

Why do we omit patients as stakeholders? There are considerable barriers to seeking patient input. The busy hospital environment or the acuity of a patient’s illness may, for instance, limit engagement between hospital caregivers and patients. Further, the power imbalance between physicians and patients may make it uncomfortable for the patient to offer direct feedback.

However, the importance of patient input is increasingly recognized by researchers. For example, community-based participatory research “involves community members or recipients of interventions in all phases of the research process.”2 Similarly, we believe hospitalists should engage patients when designing new clinical initiatives.

Examples from some institutions provide further support of this concept. The Dana Farber Cancer Institute created a patient and family advisory council in response to the loss of trust over errors and in the face of community outrage over an impending joint venture. While the scope was initially limited to the collection of feedback regarding patient satisfaction and preferences, the council evolved to become an integral part of organizational decision making. Patient contributions were subsequently assimilated into policies, continuous improvement teams, and even search committees. Additional benefits included patient-generated initiatives such as “patient rounds.”3 Specifically soliciting input from hospitalized patients to inform hospital-based interventions may be uncommon, but this practice holds the potential to yield vital insights.4

We have experienced this benefit at our institution. For example, before implementing an inpatient addiction medicine consult service, we asked hospitalized patients struggling with addiction about their needs. The patient voice highlighted a lack of trust for hospital providers and led directly to the inclusion of peer-recovery mentors as part of the consulting team.5

Many organizations, including our own, have instituted a patient/family advisory committee comprising former patients and family members who participate voluntarily in projects and provide input. This resource can serve as an excellent platform for patient involvement. At the University of Michigan, the patient and family advisory council provides input on every major institutional decision, from the construction of a new building to the introduction of a new clinical service. This “hardwired” practice ensures that patients’ voices and views are incorporated into major health system decisions.

In order to engage patients as stakeholders, we recommend: (1) Be sensitive to the power imbalance between clinicians and patients and recognize that hospitalized patients may not feel comfortable providing direct feedback. (2) Familiarize yourself with your institution’s patient/family advisory committee. If one does not exist, consider soliciting responses from patients via interviews and/or postdischarge surveys. (3) Deliberately seek the opinions, experience, and values of patients or their representatives. (4) For projects aimed at improving patient experience, include patients among your key stakeholders.

Involving patients as stakeholders requires effort; however, it has potential to reap valuable rewards, making healthcare improvements more effective, inclusive, and healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeffrey S. Stewart for his contributions and feedback on this topic and manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Friedman S. Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life (With New Preface). Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

2. Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti034

3. Ponte PR, Conlin G, Conway JB, et al. Making patient-centered care come alive: achieving full integration of the patient’s perspective. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(2):82-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200302000-00004

4. O’Leary KJ, Chapman MM, Foster S, O’Hara L, Henschen BL, Cameron KA. Frequently hospitalized patients’ perceptions of factors contributing to high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(9):521-526. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3175

5. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4

“Nothing about us without us” (Latin: ”Nihil de nobis, sine nobis”)

Hospitalists are at the forefront of decisions, innovations, and system-improvement projects that impact hospitalized patients. However, many of our decisions—while centered on patient care—fail to include their perspectives or views.

In his book Total Leadership, Stewart Friedman describes the importance of identifying and engaging key stakeholders.1 Friedman exhorts leaders to engage stakeholders in conversations to “confirm or correct your current understanding of stakeholder expectations.” In other words, instead of assuming what stakeholders want, ask and verify before proceeding.

Although hospitalists frequently include stakeholders such as nurses, pharmacists, and therapists in system-improvement initiatives, engaging patients is less common.

Why do we omit patients as stakeholders? There are considerable barriers to seeking patient input. The busy hospital environment or the acuity of a patient’s illness may, for instance, limit engagement between hospital caregivers and patients. Further, the power imbalance between physicians and patients may make it uncomfortable for the patient to offer direct feedback.

However, the importance of patient input is increasingly recognized by researchers. For example, community-based participatory research “involves community members or recipients of interventions in all phases of the research process.”2 Similarly, we believe hospitalists should engage patients when designing new clinical initiatives.

Examples from some institutions provide further support of this concept. The Dana Farber Cancer Institute created a patient and family advisory council in response to the loss of trust over errors and in the face of community outrage over an impending joint venture. While the scope was initially limited to the collection of feedback regarding patient satisfaction and preferences, the council evolved to become an integral part of organizational decision making. Patient contributions were subsequently assimilated into policies, continuous improvement teams, and even search committees. Additional benefits included patient-generated initiatives such as “patient rounds.”3 Specifically soliciting input from hospitalized patients to inform hospital-based interventions may be uncommon, but this practice holds the potential to yield vital insights.4

We have experienced this benefit at our institution. For example, before implementing an inpatient addiction medicine consult service, we asked hospitalized patients struggling with addiction about their needs. The patient voice highlighted a lack of trust for hospital providers and led directly to the inclusion of peer-recovery mentors as part of the consulting team.5

Many organizations, including our own, have instituted a patient/family advisory committee comprising former patients and family members who participate voluntarily in projects and provide input. This resource can serve as an excellent platform for patient involvement. At the University of Michigan, the patient and family advisory council provides input on every major institutional decision, from the construction of a new building to the introduction of a new clinical service. This “hardwired” practice ensures that patients’ voices and views are incorporated into major health system decisions.

In order to engage patients as stakeholders, we recommend: (1) Be sensitive to the power imbalance between clinicians and patients and recognize that hospitalized patients may not feel comfortable providing direct feedback. (2) Familiarize yourself with your institution’s patient/family advisory committee. If one does not exist, consider soliciting responses from patients via interviews and/or postdischarge surveys. (3) Deliberately seek the opinions, experience, and values of patients or their representatives. (4) For projects aimed at improving patient experience, include patients among your key stakeholders.

Involving patients as stakeholders requires effort; however, it has potential to reap valuable rewards, making healthcare improvements more effective, inclusive, and healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeffrey S. Stewart for his contributions and feedback on this topic and manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

“Nothing about us without us” (Latin: ”Nihil de nobis, sine nobis”)

Hospitalists are at the forefront of decisions, innovations, and system-improvement projects that impact hospitalized patients. However, many of our decisions—while centered on patient care—fail to include their perspectives or views.

In his book Total Leadership, Stewart Friedman describes the importance of identifying and engaging key stakeholders.1 Friedman exhorts leaders to engage stakeholders in conversations to “confirm or correct your current understanding of stakeholder expectations.” In other words, instead of assuming what stakeholders want, ask and verify before proceeding.

Although hospitalists frequently include stakeholders such as nurses, pharmacists, and therapists in system-improvement initiatives, engaging patients is less common.

Why do we omit patients as stakeholders? There are considerable barriers to seeking patient input. The busy hospital environment or the acuity of a patient’s illness may, for instance, limit engagement between hospital caregivers and patients. Further, the power imbalance between physicians and patients may make it uncomfortable for the patient to offer direct feedback.

However, the importance of patient input is increasingly recognized by researchers. For example, community-based participatory research “involves community members or recipients of interventions in all phases of the research process.”2 Similarly, we believe hospitalists should engage patients when designing new clinical initiatives.

Examples from some institutions provide further support of this concept. The Dana Farber Cancer Institute created a patient and family advisory council in response to the loss of trust over errors and in the face of community outrage over an impending joint venture. While the scope was initially limited to the collection of feedback regarding patient satisfaction and preferences, the council evolved to become an integral part of organizational decision making. Patient contributions were subsequently assimilated into policies, continuous improvement teams, and even search committees. Additional benefits included patient-generated initiatives such as “patient rounds.”3 Specifically soliciting input from hospitalized patients to inform hospital-based interventions may be uncommon, but this practice holds the potential to yield vital insights.4

We have experienced this benefit at our institution. For example, before implementing an inpatient addiction medicine consult service, we asked hospitalized patients struggling with addiction about their needs. The patient voice highlighted a lack of trust for hospital providers and led directly to the inclusion of peer-recovery mentors as part of the consulting team.5

Many organizations, including our own, have instituted a patient/family advisory committee comprising former patients and family members who participate voluntarily in projects and provide input. This resource can serve as an excellent platform for patient involvement. At the University of Michigan, the patient and family advisory council provides input on every major institutional decision, from the construction of a new building to the introduction of a new clinical service. This “hardwired” practice ensures that patients’ voices and views are incorporated into major health system decisions.

In order to engage patients as stakeholders, we recommend: (1) Be sensitive to the power imbalance between clinicians and patients and recognize that hospitalized patients may not feel comfortable providing direct feedback. (2) Familiarize yourself with your institution’s patient/family advisory committee. If one does not exist, consider soliciting responses from patients via interviews and/or postdischarge surveys. (3) Deliberately seek the opinions, experience, and values of patients or their representatives. (4) For projects aimed at improving patient experience, include patients among your key stakeholders.

Involving patients as stakeholders requires effort; however, it has potential to reap valuable rewards, making healthcare improvements more effective, inclusive, and healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeffrey S. Stewart for his contributions and feedback on this topic and manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Friedman S. Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life (With New Preface). Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

2. Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti034

3. Ponte PR, Conlin G, Conway JB, et al. Making patient-centered care come alive: achieving full integration of the patient’s perspective. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(2):82-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200302000-00004

4. O’Leary KJ, Chapman MM, Foster S, O’Hara L, Henschen BL, Cameron KA. Frequently hospitalized patients’ perceptions of factors contributing to high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(9):521-526. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3175

5. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4

1. Friedman S. Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life (With New Preface). Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

2. Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti034

3. Ponte PR, Conlin G, Conway JB, et al. Making patient-centered care come alive: achieving full integration of the patient’s perspective. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(2):82-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200302000-00004

4. O’Leary KJ, Chapman MM, Foster S, O’Hara L, Henschen BL, Cameron KA. Frequently hospitalized patients’ perceptions of factors contributing to high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(9):521-526. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3175

5. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Psychiatric manifestations of sport-related concussion

Ms. J, age 19, is a Division I collegiate volleyball player who recently sustained her third sport-related concussion (SRC). She has no psychiatric history but does have a history of migraine, and her headaches have worsened since the most recent SRC. She has a family history of depression (mother and her sole sibling). Ms. J recently experienced the loss of her coach, someone she greatly admired, in a motor vehicle accident. She is referred to outpatient psychiatry for assessment of mood symptoms that are persisting 1 month after the SRC. Upon assessment, she is found to meet 8 of the 9 criteria for a major depressive episode, including suicidality with vague plans but no intent to end her life.

Although Ms. J does not have a history of psychiatric illness, her psychiatrist recognizes that she has factors that increase her risk of developing depression post-SRC, and of poor recovery from SRC. These include pre-existing symptoms, such as her history of migraine, which is common in patients after SRC. Additionally, a family history of psychiatric disorders and high life stressors (eg, recent loss of her coach) are risk factors for a poor SRC recovery.1 Due to these risk factors and the severity of Ms. J’s symptoms—which include suicidal ideation—the psychiatrist believes that her depressive symptoms might be unlikely to improve in the coming weeks, so he establishes a diagnosis of “depressive disorder due to another medical condition (concussion)” because the development of her depressive symptoms coincided with the SRC. If Ms. J had a pre-existing mood disorder, or if her depression had not developed until later in the post-injury period, it would have been more difficult to establish confidently that the depressive episode was a direct physiologic consequence of the SRC; if that had been the case, the diagnosis probably would have been unspecified or other specified depressive disorder.2

SRC is a traumatic brain injury (TBI) induced by biomechanical forces, typically resulting in short-lived impairment of neurologic function, although signs and symptoms may evolve over minutes to hours.3 It largely reflects functional, rather than structural, brain disturbances.3 SRC has been deemed a “neuropsychiatric syndrome” because psychiatric manifestations are common.4 There may be a myriad of biopsychosocial factors involved in the etiology of psychiatric symptoms in an individual who sustains an SRC. For example, SRC may have a direct physiologic cause of psychiatric symptoms based on the location and degree of injury to the brain. Additionally, pre-existing psychiatric symptoms might increase the likelihood of sustaining an SRC. Finally, as with any major injury, illness, or event, stressors associated with SRC may cause psychiatric symptoms.

Regardless of causal factors, psychiatrists should be comfortable with managing psychiatric symptoms that commonly accompany this condition. This article highlights possible psychiatric manifestations of SRC and delineates high-yield management considerations. Although it focuses on concussions that occur in the context of sport, much of the information applies to patients who experience concussions from other causes.

SRC and depression

Changes in mood, emotion, and behavior are common following SRC. On the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5),5 which is a standardized tool used to evaluate athletes suspected of having sustained a concussion, most symptoms overlap with those attributable to anxiety and depression.4,6 These include5:

- feeling slowed down

- “not feeling right”

- difficulty concentrating

- fatigue or loss of energy

- feeling more emotional

- irritability

- sadness

- feeling nervous or anxious

- difficulty falling asleep.

A recent systematic review of mental health outcomes of SRC in athletes found that the most commonly described and studied psychiatric symptoms following SRC were depression, anxiety, and impulsivity.7 The most rigorous study included in this review found depressive symptoms in 20% of collegiate athletes following SRC (all tested within 41 days of the SRC) vs 5% in the control group.8 These researchers delineated factors that predicted depressive symptoms after SRC (Box 18). Data were insufficient to draw conclusions about the association between SRC and other psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety.8

Box 1

- Baseline depressive symptoms

- Baseline “post-concussion” symptoms

- Lower estimated premorbid intelligence

- Nonwhite ethnicity

- Increased number of games missed following injury

- Age of first participation in organized sport (more depression in athletes with fewer years of experience)

Source: Reference 8

Psychiatric manifestations of concussion in retired athletes may shed light on the long-term impact of SRC on psychiatric disorders, particularly depression. Hutchison et al9 conducted a systematic review of mental health outcomes of SRC in retired athletes.Two of the included studies that measured clinically diagnosed disorders found positive associations between self-reported concussion and clinically diagnosed depression.10,11 Hutchison et al9 found insufficient data to draw conclusions about depression and a lifetime history of subconcussive impacts—a topic that is receiving growing attention.

Continue to: Regarding a dose-response relationship...

Regarding a dose-response relationship in retired athletes, Guskiewicz et al11 reported a 3-fold increased risk of depression among retired professional football players who had experienced ≥3 SRCs. Five years later, the same research group reported a 5.8-fold increased risk of depression in retired professional football players after 5 to 9 concussions.10 In sum, there is evidence to suggest that the more SRCs an athlete sustains, the more likely they are to develop depression. Moreover, depression may persist or develop long after an SRC occurs.

Suicide risk

While suicide among athletes, especially football players, who have experienced concussion has received relatively widespread media attention, the risk of suicide in former professional football players appears to be significantly lower than in the general population.12 A recent large systematic review and meta-analysis reported on 713,706 individuals diagnosed with concussion and/or mild TBI and 6,236,010 individuals with no such diagnoses.13 It found a 2-fold higher risk of suicide in individuals who experienced concussion and/or mild TBI, but because participants were not necessarily athletes, it is difficult to extrapolate these findings to the athlete population.

Other psychiatric symptoms associated with SRC

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some athletes experience PTSD symptoms shortly after SRC, and these can be missed if clinicians do not specifically ask about them.14 For example, substantial proportions of athletes who have had an SRC report making efforts to avoid sport situations that are similar to how and where their SRC occurred (19%), having trouble keeping thoughts about sustaining the SRC out of their heads (18%), experiencing flashbacks of sustaining the SRC (13%), and having nightmares about sustaining the SRC (8%).14 Posttraumatic stress disorder may have a negative impact on an athlete’s performance because a fear of re-injury might lead them to avoid rehabilitation exercises and inhibit their effort.15-18

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is commonly comorbid with SRC.19,20 It is not known if pre-existing ADHD makes sustaining a concussion more likely (eg, because the athlete is distractible and thus does not notice when an opponent is about to hit them hard) and/or if a history of concussion makes ADHD more likely to develop (eg, because something about the concussed brain is changed in a way that leads to ADHD). Additionally, in some cases, ADHD has been associated with prolonged recovery from SRC.3,21

Immediate medical evaluation and cognitive assessment

Any patient in whom an SRC is suspected should undergo a medical evaluation immediately, whether in a physician’s office, emergency department, or on the sideline of a sports event. This medical evaluation should incorporate a clinical neurologic assessment, including evaluation of mental status/cognition, oculomotor function, gross sensorimotor, coordination, gait, vestibular function, and balance.3

Continue to: There is no single guideline...

There is no single guideline on how and when a neuropsychology referral is warranted.22 Insurance coverage for neurocognitive testing varies. Regardless of formal referral to neuropsychology, assessment of cognitive function is an important aspect of SRC management and is a factor in return-to-school and return-to-play decisions.3,22 Screening tools, such as the SCAT5, are useful in acute and subacute settings (ie, up to 3 to 5 days after injury); clinicians often use serial monitoring to track the resolution of symptoms.3 If pre-season baseline cognitive test results are available, clinicians may compare them to post-SRC results, but this should not be the sole basis of management decisions.3,22

Diagnosing psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC

Diagnosis of psychiatric symptoms and disorders associated with SRC can be challenging.7 There are no concussion-specific rating scales or diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders unique to patients who have sustained SRC. As a result, clinicians are left to use standard DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC. Importantly, psychiatric symptoms must be distinguished from disorders. For example, Kontos et al23 reported significantly worse depressive symptoms following SRC, but not at the level to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder. This is an important distinction, because a psychiatrist might be less likely to initiate pharmacotherapy for a patient with SRC who has only a few depressive symptoms and is only 1 week post-SRC, vs for one who has had most symptoms of a major depressive episode for several weeks.

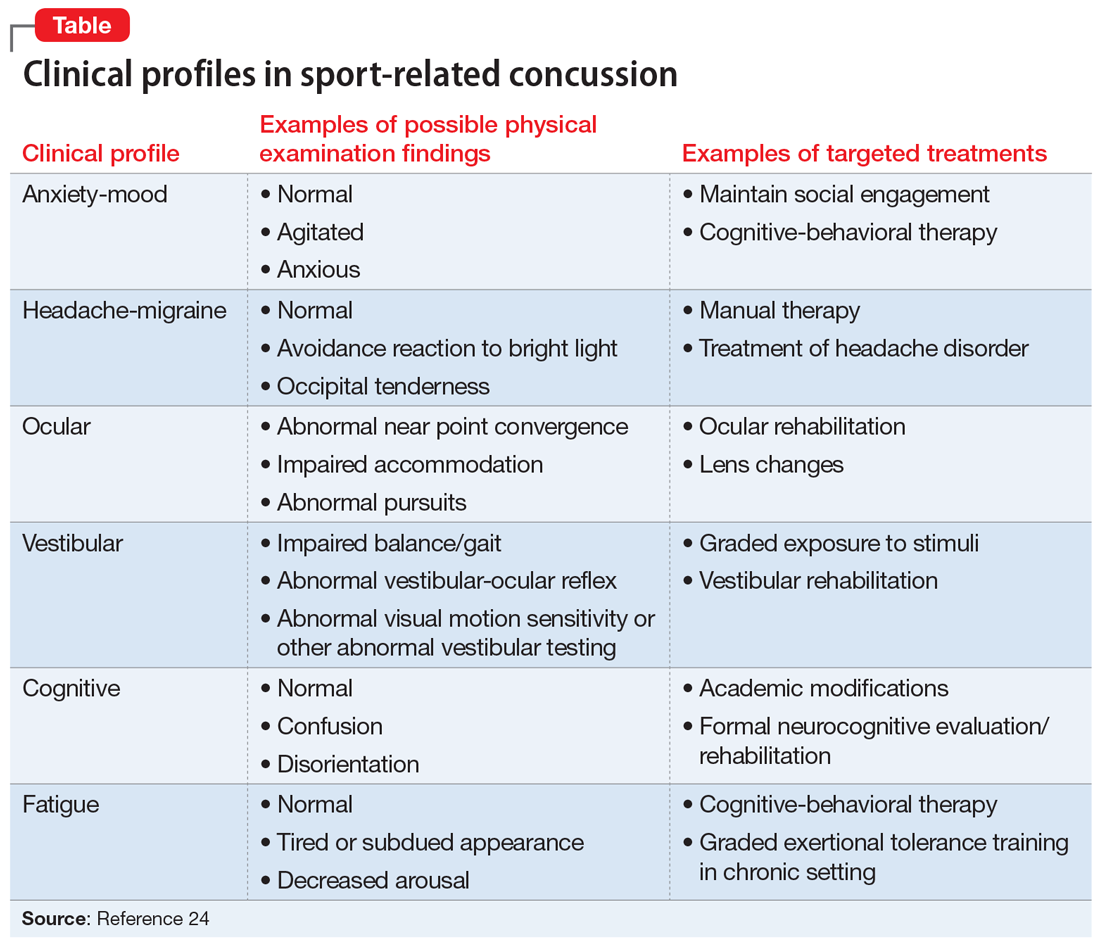

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine has proposed 6 overlapping clinical profiles in patients with SRC (see the Table).24 Most patients with SRC have features of multiple clinical profiles.24 Anxiety/mood is one of these profiles. The impetus for developing these profiles was the recognition of heterogeneity among concussion presentations. Identification of the clinical profile(s) into which a patient’s symptoms fall might allow for more specific prognostication and targeted treatment.24 For example, referral to a psychiatrist obviously would be appropriate for a patient for whom anxiety/mood symptoms are prominent.

Treatment options for psychiatric sequelae of SRC

Both psychosocial and medical principles of management of psychiatric manifestations of SRC are important. Psychosocially, clinicians should address factors that may contribute to delayed SRC recovery (Box 225-30).

Box 2

- Recommend a progressive increase in exercise after a brief period of rest (often ameliorates psychiatric symptoms, as opposed to the historical approach of “cocoon therapy” in which the patient was to rest for prolonged periods of time in a darkened room so as to minimize brain stimulation)25

- Allow social activities, including team meetings (restriction of such activities has been associated with increased post-SRC depression)26

- Encourage members of the athlete’s “entourage” (team physicians, athletic trainers, coaches, teammates, and parents) to provide support27

- Educate coaches and teammates about how to make supportive statements because they often have trouble knowing how to do so27

- Recommend psychotherapy for mental and other physical symptoms of SRC that are moderate to severe or that persist longer than 4 weeks after the SRC28

- Recommend minimization of use of alcohol and other substances29,30

SRC: sport-related concussion

No medications are FDA-approved for SRC or associated psychiatric symptoms, and there is minimal evidence to support the use of specific medications.31 Most athletes with SRC recover quickly—typically within 2 weeks—and do not need medication.4,32 When medications are needed, start with low dosing and titrate slowly.33,34

Continue to: For patients with SRC who experience insomnia...

For patients with SRC who experience insomnia, clinicians should focus on sleep hygiene and, if needed, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).31 If medication is needed, melatonin may be a first-line agent.31,35,36 Trazodone may be a second option.32 Benzodiazepines typically are avoided because of their negative impact on cognition.31

For patients with SRC who have depression, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may simultaneously improve depressed mood31 and cognition.37 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are sometimes used to treat headaches, depression, anxiety, and/or insomnia after SRC,32 but adverse effects such as sedation and weight gain may limit their use in athletes. Theoretically, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors might have some of the same benefits as TCAs with fewer adverse effects, but they have not been well studied in patients with SRC.

For patients with SRC who have cognitive dysfunction (eg, deficits in attention and processing speed), there is some evidence for treatment with stimulants.31,37 However, these medications are prohibited by many athletic governing organizations, including professional sports leagues, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), and the World Anti-Doping Agency.4 If an athlete was receiving stimulants for ADHD before sustaining an SRC, there is no evidence that these medications should be stopped.

Consider interdisciplinary collaboration

Throughout the course of management, psychiatrists should consider if and when it is necessary to consult with other specialties such as primary care, sports medicine, neurology, and neuropsychology. As with many psychiatric symptoms and disorders, collaboration with an interdisciplinary team is recommended. Primary care, sports medicine, or neurology should be involved in the management of patients with SRC. Choice of which of those 3 specialties in particular will depend on comfort level and experience with managing SRC of the individual providers in question as well as availability of each provider type in a given community.

Additionally, psychiatrists may wonder if and when they should refer patients with SRC for neuroimaging. Because SRC is a functional, rather than structural, brain disturbance, neuroimaging is not typically pursued because results would be expected to be normal.3 However, when in doubt, consultation with the interdisciplinary team can guide this decision. Factors that may lead to a decision to obtain neuroimaging include:

- an abnormal neurologic examination

- prolonged loss of consciousness

- unexpected persistence of symptoms (eg, 6 to 12 weeks)

- worsening symptoms.22

Continue to: If imaging is deemed necessary...

If imaging is deemed necessary for a patient with an acute SRC, brain CT is typically the imaging modality of choice; however, if imaging is deemed necessary due to the persistence of symptoms, then MRI is often the preferred test because it provides more detailed information and does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation.22 While results are often normal, the ordering clinician should be prepared for the possibility of incidental findings, such as cysts or aneurysms, and the need for further consultation with other clinicians to weigh in on such findings.22

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. J is prescribed extended-release venlafaxine, 37.5 mg every morning for 5 days, and then is switched to 75 mg every morning. The psychiatrist hopes that venlafaxine might simultaneously offer benefit for Ms. J’s depression and migraine headaches. Venlafaxine is not FDA-approved for migraine, and there is more evidence supporting TCAs for preventing migraine. However, Ms. J is adamant that she does not want to take a medication, such as a TCA, that could cause weight gain or sedation, which could be problematic in her sport. The psychiatrist also tells Ms. J to avoid substances of abuse, and emphasizes the importance of good sleep hygiene. Finally, the psychiatrist communicates with the interdisciplinary medical team, which is helping Ms. J with gradual return-to-school and return-to-sport strategies and ensuring continued social involvement with the team even as she is held out from sport.

Ultimately, Ms. J’s extended-release venlafaxine is titrated to 150 mg every morning. After 2 months on this dose, her depressive symptoms remit. After her other symptoms remit, Ms. J has difficulty returning to certain practice drills that remind her of what she was doing when she sustained the SRC. She says that while participating in these drills, she has intrusive thoughts and images of the experience of her most recent concussion. She works with her psychiatrist on a gradual program of exposure therapy so she can return to all types of practice. Ms. J says she wishes to continue playing volleyball; however, together with her parents and treatment team, she decides that any additional SRCs might lead her to retire from the sport.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric symptoms are common after sport-related concussion (SRC). The nature of the relationship between concussion and mental health is not firmly established. Post-SRC psychiatric symptoms need to be carefully managed to avoid unnecessary treatment or restrictions.

Related Resources

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. Concussion. www.ncaa.org/sport-science-institute/concussion.

- American Academy of Neurology. Sports concussion resources. www.aan.com/tools-and-resources/practicing-neurologists-administrators/patient-resources/sports-concussion-resources. Published 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Trazodone • Desyrel

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Morgan CD, Zuckerman SL, Lee YM, et al. Predictors of postconcussion syndrome after sports-related concussion in young athletes: a matched case-control study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15(6):589-598.

2. Jorge RE, Arciniegas DB. Mood disorders after TBI. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(1):13-29.

3. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvor˘ák J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th International Conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):838-847.

4. Reardon CL, Hainline B, Aron CM, et al. Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(11):667-699.

5. Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The sport concussion assessment tool 5th edition (SCAT5): background and rationale. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:848-850.

6. Thompson E. Hamilton rating scale for anxiety (HAM-A). Occup Med. 2015;65(7):601.

7. Rice SM, Parker AG, Rosenbaum S, et al. Sport-related concussion outcomes in elite athletes: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2018;48(2):447-465.

8. Vargas G, Rabinowitz A, Meyer J, et al. Predictors and prevalence of postconcussion depression symptoms in collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2015;50(3):250-255.

9. Hutchison MG, Di Battista AP, McCoskey J, et al. Systematic review of mental health measures associated with concussive and subconcussive head trauma in former athletes. Int J Psychophysiol. 2018;132(Pt A):55-61.

10. Kerr GA, Stirling AE. Parents’ reflections on their child’s experiences of emotionally abusive coaching practices. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2012;24(2):191-206.

11. Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Bailes J, et al. Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(6):903-909.

12. Lehman EJ, Hein MJ, Gersic CM. Suicide mortality among retired National Football League players who played 5 or more seasons. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(10):2486-2491.

13. Fralick M, Sy E, Hassan A, et al. Association of concussion with the risk of suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2018;76(2):144-151.

14. Brassil HE, Salvatore AP. The frequency of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in athletes with and without sports related concussion. Clin Transl Med. 2018;7:25.

15. Bateman A, Morgan KAD. The postinjury psychological sequelae of high-level Jamaican athletes: exploration of a posttraumatic stress disorder-self-efficacy conceptualization. J Sport Rehabil. 2019;28(2):144-152.

16. Brewer BW, Van Raalte JL, Cornelius AE, et al. Psychological factors, rehabilitation adherence, and rehabilitation outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Rehabil Psychol. 2000;45(1):20-37.

17. Putukian M, Echemendia RJ. Psychological aspects of serious head injury in the competitive athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22(33):617-630.

18. James LM, Strom TQ, Leskela J. Risk-taking behaviors and impulsivity among Veterans with and without PTSD and mild TBI. Mil Med. 2014;179(4):357-363.

19. Harmon KG, Drezner J, Gammons M, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;47(1):15-26.

20. Nelson LD, Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, et al. Multiple self-reported concussions are more prevalent in athletes with ADHD and learning disability. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26(2):120-127.

21. Esfandiari A, Broshek DK, Freeman JR. Psychiatric and neuropsychological issues in sports medicine. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(3):611-627.

22. Mahooti N. Sport-related concussion: acute management and chronic postconcussive issues. Chld Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2018;27(1):93-108.

23. Kontos AP, Covassin T, Elbin RJ, et al. Depression and neurocognitive performance after concussion among male and female high school and collegiate athletes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(10):1751-1756.

24. Harmon KG, Clugston JR, Dec K, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement on concussion in sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2019;29(2):87-100.

25. Leddy JJ, Willer B. Use of graded exercise testing in concussion and return-to-activity management. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2013;12(6):370-376.

26. Schneider KJ, Iverson GL, Emery CA, et al. The effects of rest and treatment following sport-related concussion: a systematic review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(5):304-307.

27. Wayment HA, Huffman AH. Psychosocial experiences of concussed collegiate athletes: the role of emotional support in the recovery process. J Am Coll Health. 2020;68(4):438-443.

28. Todd R, Bhalerao S, Vu MT, et al. Understanding the psychiatric effects of concussion on constructed identity in hockey players: implications for health professionals. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0192125.

29. Iverson GL, Silverberg ND, Mannix R, et al. Factors associated with concussion-like symptom reporting in high school athletes. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(12):1132-1140.

30. Gaetz M. The multi-factorial origins of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) symptomatology in post-career athletes: the athlete post-career adjustment (AP-CA) model. Med Hypotheses. 2017;102:130-143.

31. Meehan WP. Medical therapies for concussion. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):115-124.

32. Broglio SP, Collins MW, Williams RM, et al. Current and emerging rehabilitation for concussion: a review of the evidence. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34(2):213-231.

33. Arciniegas DB, Silver JM, McAllister TW. Stimulants and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Psychopharm Review. 2008;43(12):91-97.

34. Warden DL, Gordon B, McAllister TW, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(10):1468-1501.

35. Maldonado MD, Murillo-Cabezas F, Terron MP, et al. The potential of melatonin in reducing morbidity/mortality after craniocerebral trauma. J Pineal Res. 2007;42(1):1-11.

36. Samantaray S, Das A, Thakore NP, et al. Therapeutic potential of melatonin in traumatic central nervous system injury. J Pineal Res. 2009;47(2):134-142.

37. Chew E, Zafonte RD. Pharmacological management of neurobehavioral disorders following traumatic brain injury—a state-of-the-art review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6):851-879.

Ms. J, age 19, is a Division I collegiate volleyball player who recently sustained her third sport-related concussion (SRC). She has no psychiatric history but does have a history of migraine, and her headaches have worsened since the most recent SRC. She has a family history of depression (mother and her sole sibling). Ms. J recently experienced the loss of her coach, someone she greatly admired, in a motor vehicle accident. She is referred to outpatient psychiatry for assessment of mood symptoms that are persisting 1 month after the SRC. Upon assessment, she is found to meet 8 of the 9 criteria for a major depressive episode, including suicidality with vague plans but no intent to end her life.

Although Ms. J does not have a history of psychiatric illness, her psychiatrist recognizes that she has factors that increase her risk of developing depression post-SRC, and of poor recovery from SRC. These include pre-existing symptoms, such as her history of migraine, which is common in patients after SRC. Additionally, a family history of psychiatric disorders and high life stressors (eg, recent loss of her coach) are risk factors for a poor SRC recovery.1 Due to these risk factors and the severity of Ms. J’s symptoms—which include suicidal ideation—the psychiatrist believes that her depressive symptoms might be unlikely to improve in the coming weeks, so he establishes a diagnosis of “depressive disorder due to another medical condition (concussion)” because the development of her depressive symptoms coincided with the SRC. If Ms. J had a pre-existing mood disorder, or if her depression had not developed until later in the post-injury period, it would have been more difficult to establish confidently that the depressive episode was a direct physiologic consequence of the SRC; if that had been the case, the diagnosis probably would have been unspecified or other specified depressive disorder.2

SRC is a traumatic brain injury (TBI) induced by biomechanical forces, typically resulting in short-lived impairment of neurologic function, although signs and symptoms may evolve over minutes to hours.3 It largely reflects functional, rather than structural, brain disturbances.3 SRC has been deemed a “neuropsychiatric syndrome” because psychiatric manifestations are common.4 There may be a myriad of biopsychosocial factors involved in the etiology of psychiatric symptoms in an individual who sustains an SRC. For example, SRC may have a direct physiologic cause of psychiatric symptoms based on the location and degree of injury to the brain. Additionally, pre-existing psychiatric symptoms might increase the likelihood of sustaining an SRC. Finally, as with any major injury, illness, or event, stressors associated with SRC may cause psychiatric symptoms.

Regardless of causal factors, psychiatrists should be comfortable with managing psychiatric symptoms that commonly accompany this condition. This article highlights possible psychiatric manifestations of SRC and delineates high-yield management considerations. Although it focuses on concussions that occur in the context of sport, much of the information applies to patients who experience concussions from other causes.

SRC and depression

Changes in mood, emotion, and behavior are common following SRC. On the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5),5 which is a standardized tool used to evaluate athletes suspected of having sustained a concussion, most symptoms overlap with those attributable to anxiety and depression.4,6 These include5:

- feeling slowed down

- “not feeling right”

- difficulty concentrating

- fatigue or loss of energy

- feeling more emotional

- irritability

- sadness

- feeling nervous or anxious

- difficulty falling asleep.

A recent systematic review of mental health outcomes of SRC in athletes found that the most commonly described and studied psychiatric symptoms following SRC were depression, anxiety, and impulsivity.7 The most rigorous study included in this review found depressive symptoms in 20% of collegiate athletes following SRC (all tested within 41 days of the SRC) vs 5% in the control group.8 These researchers delineated factors that predicted depressive symptoms after SRC (Box 18). Data were insufficient to draw conclusions about the association between SRC and other psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety.8

Box 1

- Baseline depressive symptoms

- Baseline “post-concussion” symptoms

- Lower estimated premorbid intelligence

- Nonwhite ethnicity

- Increased number of games missed following injury

- Age of first participation in organized sport (more depression in athletes with fewer years of experience)

Source: Reference 8

Psychiatric manifestations of concussion in retired athletes may shed light on the long-term impact of SRC on psychiatric disorders, particularly depression. Hutchison et al9 conducted a systematic review of mental health outcomes of SRC in retired athletes.Two of the included studies that measured clinically diagnosed disorders found positive associations between self-reported concussion and clinically diagnosed depression.10,11 Hutchison et al9 found insufficient data to draw conclusions about depression and a lifetime history of subconcussive impacts—a topic that is receiving growing attention.

Continue to: Regarding a dose-response relationship...

Regarding a dose-response relationship in retired athletes, Guskiewicz et al11 reported a 3-fold increased risk of depression among retired professional football players who had experienced ≥3 SRCs. Five years later, the same research group reported a 5.8-fold increased risk of depression in retired professional football players after 5 to 9 concussions.10 In sum, there is evidence to suggest that the more SRCs an athlete sustains, the more likely they are to develop depression. Moreover, depression may persist or develop long after an SRC occurs.

Suicide risk

While suicide among athletes, especially football players, who have experienced concussion has received relatively widespread media attention, the risk of suicide in former professional football players appears to be significantly lower than in the general population.12 A recent large systematic review and meta-analysis reported on 713,706 individuals diagnosed with concussion and/or mild TBI and 6,236,010 individuals with no such diagnoses.13 It found a 2-fold higher risk of suicide in individuals who experienced concussion and/or mild TBI, but because participants were not necessarily athletes, it is difficult to extrapolate these findings to the athlete population.

Other psychiatric symptoms associated with SRC

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some athletes experience PTSD symptoms shortly after SRC, and these can be missed if clinicians do not specifically ask about them.14 For example, substantial proportions of athletes who have had an SRC report making efforts to avoid sport situations that are similar to how and where their SRC occurred (19%), having trouble keeping thoughts about sustaining the SRC out of their heads (18%), experiencing flashbacks of sustaining the SRC (13%), and having nightmares about sustaining the SRC (8%).14 Posttraumatic stress disorder may have a negative impact on an athlete’s performance because a fear of re-injury might lead them to avoid rehabilitation exercises and inhibit their effort.15-18

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is commonly comorbid with SRC.19,20 It is not known if pre-existing ADHD makes sustaining a concussion more likely (eg, because the athlete is distractible and thus does not notice when an opponent is about to hit them hard) and/or if a history of concussion makes ADHD more likely to develop (eg, because something about the concussed brain is changed in a way that leads to ADHD). Additionally, in some cases, ADHD has been associated with prolonged recovery from SRC.3,21

Immediate medical evaluation and cognitive assessment

Any patient in whom an SRC is suspected should undergo a medical evaluation immediately, whether in a physician’s office, emergency department, or on the sideline of a sports event. This medical evaluation should incorporate a clinical neurologic assessment, including evaluation of mental status/cognition, oculomotor function, gross sensorimotor, coordination, gait, vestibular function, and balance.3

Continue to: There is no single guideline...

There is no single guideline on how and when a neuropsychology referral is warranted.22 Insurance coverage for neurocognitive testing varies. Regardless of formal referral to neuropsychology, assessment of cognitive function is an important aspect of SRC management and is a factor in return-to-school and return-to-play decisions.3,22 Screening tools, such as the SCAT5, are useful in acute and subacute settings (ie, up to 3 to 5 days after injury); clinicians often use serial monitoring to track the resolution of symptoms.3 If pre-season baseline cognitive test results are available, clinicians may compare them to post-SRC results, but this should not be the sole basis of management decisions.3,22

Diagnosing psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC

Diagnosis of psychiatric symptoms and disorders associated with SRC can be challenging.7 There are no concussion-specific rating scales or diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders unique to patients who have sustained SRC. As a result, clinicians are left to use standard DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC. Importantly, psychiatric symptoms must be distinguished from disorders. For example, Kontos et al23 reported significantly worse depressive symptoms following SRC, but not at the level to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder. This is an important distinction, because a psychiatrist might be less likely to initiate pharmacotherapy for a patient with SRC who has only a few depressive symptoms and is only 1 week post-SRC, vs for one who has had most symptoms of a major depressive episode for several weeks.

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine has proposed 6 overlapping clinical profiles in patients with SRC (see the Table).24 Most patients with SRC have features of multiple clinical profiles.24 Anxiety/mood is one of these profiles. The impetus for developing these profiles was the recognition of heterogeneity among concussion presentations. Identification of the clinical profile(s) into which a patient’s symptoms fall might allow for more specific prognostication and targeted treatment.24 For example, referral to a psychiatrist obviously would be appropriate for a patient for whom anxiety/mood symptoms are prominent.

Treatment options for psychiatric sequelae of SRC

Both psychosocial and medical principles of management of psychiatric manifestations of SRC are important. Psychosocially, clinicians should address factors that may contribute to delayed SRC recovery (Box 225-30).

Box 2

- Recommend a progressive increase in exercise after a brief period of rest (often ameliorates psychiatric symptoms, as opposed to the historical approach of “cocoon therapy” in which the patient was to rest for prolonged periods of time in a darkened room so as to minimize brain stimulation)25

- Allow social activities, including team meetings (restriction of such activities has been associated with increased post-SRC depression)26

- Encourage members of the athlete’s “entourage” (team physicians, athletic trainers, coaches, teammates, and parents) to provide support27

- Educate coaches and teammates about how to make supportive statements because they often have trouble knowing how to do so27

- Recommend psychotherapy for mental and other physical symptoms of SRC that are moderate to severe or that persist longer than 4 weeks after the SRC28

- Recommend minimization of use of alcohol and other substances29,30

SRC: sport-related concussion

No medications are FDA-approved for SRC or associated psychiatric symptoms, and there is minimal evidence to support the use of specific medications.31 Most athletes with SRC recover quickly—typically within 2 weeks—and do not need medication.4,32 When medications are needed, start with low dosing and titrate slowly.33,34

Continue to: For patients with SRC who experience insomnia...

For patients with SRC who experience insomnia, clinicians should focus on sleep hygiene and, if needed, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).31 If medication is needed, melatonin may be a first-line agent.31,35,36 Trazodone may be a second option.32 Benzodiazepines typically are avoided because of their negative impact on cognition.31

For patients with SRC who have depression, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may simultaneously improve depressed mood31 and cognition.37 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are sometimes used to treat headaches, depression, anxiety, and/or insomnia after SRC,32 but adverse effects such as sedation and weight gain may limit their use in athletes. Theoretically, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors might have some of the same benefits as TCAs with fewer adverse effects, but they have not been well studied in patients with SRC.

For patients with SRC who have cognitive dysfunction (eg, deficits in attention and processing speed), there is some evidence for treatment with stimulants.31,37 However, these medications are prohibited by many athletic governing organizations, including professional sports leagues, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), and the World Anti-Doping Agency.4 If an athlete was receiving stimulants for ADHD before sustaining an SRC, there is no evidence that these medications should be stopped.

Consider interdisciplinary collaboration

Throughout the course of management, psychiatrists should consider if and when it is necessary to consult with other specialties such as primary care, sports medicine, neurology, and neuropsychology. As with many psychiatric symptoms and disorders, collaboration with an interdisciplinary team is recommended. Primary care, sports medicine, or neurology should be involved in the management of patients with SRC. Choice of which of those 3 specialties in particular will depend on comfort level and experience with managing SRC of the individual providers in question as well as availability of each provider type in a given community.

Additionally, psychiatrists may wonder if and when they should refer patients with SRC for neuroimaging. Because SRC is a functional, rather than structural, brain disturbance, neuroimaging is not typically pursued because results would be expected to be normal.3 However, when in doubt, consultation with the interdisciplinary team can guide this decision. Factors that may lead to a decision to obtain neuroimaging include:

- an abnormal neurologic examination

- prolonged loss of consciousness

- unexpected persistence of symptoms (eg, 6 to 12 weeks)

- worsening symptoms.22

Continue to: If imaging is deemed necessary...

If imaging is deemed necessary for a patient with an acute SRC, brain CT is typically the imaging modality of choice; however, if imaging is deemed necessary due to the persistence of symptoms, then MRI is often the preferred test because it provides more detailed information and does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation.22 While results are often normal, the ordering clinician should be prepared for the possibility of incidental findings, such as cysts or aneurysms, and the need for further consultation with other clinicians to weigh in on such findings.22

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. J is prescribed extended-release venlafaxine, 37.5 mg every morning for 5 days, and then is switched to 75 mg every morning. The psychiatrist hopes that venlafaxine might simultaneously offer benefit for Ms. J’s depression and migraine headaches. Venlafaxine is not FDA-approved for migraine, and there is more evidence supporting TCAs for preventing migraine. However, Ms. J is adamant that she does not want to take a medication, such as a TCA, that could cause weight gain or sedation, which could be problematic in her sport. The psychiatrist also tells Ms. J to avoid substances of abuse, and emphasizes the importance of good sleep hygiene. Finally, the psychiatrist communicates with the interdisciplinary medical team, which is helping Ms. J with gradual return-to-school and return-to-sport strategies and ensuring continued social involvement with the team even as she is held out from sport.

Ultimately, Ms. J’s extended-release venlafaxine is titrated to 150 mg every morning. After 2 months on this dose, her depressive symptoms remit. After her other symptoms remit, Ms. J has difficulty returning to certain practice drills that remind her of what she was doing when she sustained the SRC. She says that while participating in these drills, she has intrusive thoughts and images of the experience of her most recent concussion. She works with her psychiatrist on a gradual program of exposure therapy so she can return to all types of practice. Ms. J says she wishes to continue playing volleyball; however, together with her parents and treatment team, she decides that any additional SRCs might lead her to retire from the sport.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric symptoms are common after sport-related concussion (SRC). The nature of the relationship between concussion and mental health is not firmly established. Post-SRC psychiatric symptoms need to be carefully managed to avoid unnecessary treatment or restrictions.

Related Resources

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. Concussion. www.ncaa.org/sport-science-institute/concussion.

- American Academy of Neurology. Sports concussion resources. www.aan.com/tools-and-resources/practicing-neurologists-administrators/patient-resources/sports-concussion-resources. Published 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Trazodone • Desyrel

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ms. J, age 19, is a Division I collegiate volleyball player who recently sustained her third sport-related concussion (SRC). She has no psychiatric history but does have a history of migraine, and her headaches have worsened since the most recent SRC. She has a family history of depression (mother and her sole sibling). Ms. J recently experienced the loss of her coach, someone she greatly admired, in a motor vehicle accident. She is referred to outpatient psychiatry for assessment of mood symptoms that are persisting 1 month after the SRC. Upon assessment, she is found to meet 8 of the 9 criteria for a major depressive episode, including suicidality with vague plans but no intent to end her life.

Although Ms. J does not have a history of psychiatric illness, her psychiatrist recognizes that she has factors that increase her risk of developing depression post-SRC, and of poor recovery from SRC. These include pre-existing symptoms, such as her history of migraine, which is common in patients after SRC. Additionally, a family history of psychiatric disorders and high life stressors (eg, recent loss of her coach) are risk factors for a poor SRC recovery.1 Due to these risk factors and the severity of Ms. J’s symptoms—which include suicidal ideation—the psychiatrist believes that her depressive symptoms might be unlikely to improve in the coming weeks, so he establishes a diagnosis of “depressive disorder due to another medical condition (concussion)” because the development of her depressive symptoms coincided with the SRC. If Ms. J had a pre-existing mood disorder, or if her depression had not developed until later in the post-injury period, it would have been more difficult to establish confidently that the depressive episode was a direct physiologic consequence of the SRC; if that had been the case, the diagnosis probably would have been unspecified or other specified depressive disorder.2

SRC is a traumatic brain injury (TBI) induced by biomechanical forces, typically resulting in short-lived impairment of neurologic function, although signs and symptoms may evolve over minutes to hours.3 It largely reflects functional, rather than structural, brain disturbances.3 SRC has been deemed a “neuropsychiatric syndrome” because psychiatric manifestations are common.4 There may be a myriad of biopsychosocial factors involved in the etiology of psychiatric symptoms in an individual who sustains an SRC. For example, SRC may have a direct physiologic cause of psychiatric symptoms based on the location and degree of injury to the brain. Additionally, pre-existing psychiatric symptoms might increase the likelihood of sustaining an SRC. Finally, as with any major injury, illness, or event, stressors associated with SRC may cause psychiatric symptoms.

Regardless of causal factors, psychiatrists should be comfortable with managing psychiatric symptoms that commonly accompany this condition. This article highlights possible psychiatric manifestations of SRC and delineates high-yield management considerations. Although it focuses on concussions that occur in the context of sport, much of the information applies to patients who experience concussions from other causes.

SRC and depression

Changes in mood, emotion, and behavior are common following SRC. On the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5),5 which is a standardized tool used to evaluate athletes suspected of having sustained a concussion, most symptoms overlap with those attributable to anxiety and depression.4,6 These include5:

- feeling slowed down

- “not feeling right”

- difficulty concentrating

- fatigue or loss of energy

- feeling more emotional

- irritability

- sadness

- feeling nervous or anxious

- difficulty falling asleep.

A recent systematic review of mental health outcomes of SRC in athletes found that the most commonly described and studied psychiatric symptoms following SRC were depression, anxiety, and impulsivity.7 The most rigorous study included in this review found depressive symptoms in 20% of collegiate athletes following SRC (all tested within 41 days of the SRC) vs 5% in the control group.8 These researchers delineated factors that predicted depressive symptoms after SRC (Box 18). Data were insufficient to draw conclusions about the association between SRC and other psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety.8

Box 1

- Baseline depressive symptoms

- Baseline “post-concussion” symptoms

- Lower estimated premorbid intelligence

- Nonwhite ethnicity

- Increased number of games missed following injury

- Age of first participation in organized sport (more depression in athletes with fewer years of experience)

Source: Reference 8

Psychiatric manifestations of concussion in retired athletes may shed light on the long-term impact of SRC on psychiatric disorders, particularly depression. Hutchison et al9 conducted a systematic review of mental health outcomes of SRC in retired athletes.Two of the included studies that measured clinically diagnosed disorders found positive associations between self-reported concussion and clinically diagnosed depression.10,11 Hutchison et al9 found insufficient data to draw conclusions about depression and a lifetime history of subconcussive impacts—a topic that is receiving growing attention.

Continue to: Regarding a dose-response relationship...

Regarding a dose-response relationship in retired athletes, Guskiewicz et al11 reported a 3-fold increased risk of depression among retired professional football players who had experienced ≥3 SRCs. Five years later, the same research group reported a 5.8-fold increased risk of depression in retired professional football players after 5 to 9 concussions.10 In sum, there is evidence to suggest that the more SRCs an athlete sustains, the more likely they are to develop depression. Moreover, depression may persist or develop long after an SRC occurs.

Suicide risk

While suicide among athletes, especially football players, who have experienced concussion has received relatively widespread media attention, the risk of suicide in former professional football players appears to be significantly lower than in the general population.12 A recent large systematic review and meta-analysis reported on 713,706 individuals diagnosed with concussion and/or mild TBI and 6,236,010 individuals with no such diagnoses.13 It found a 2-fold higher risk of suicide in individuals who experienced concussion and/or mild TBI, but because participants were not necessarily athletes, it is difficult to extrapolate these findings to the athlete population.

Other psychiatric symptoms associated with SRC

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some athletes experience PTSD symptoms shortly after SRC, and these can be missed if clinicians do not specifically ask about them.14 For example, substantial proportions of athletes who have had an SRC report making efforts to avoid sport situations that are similar to how and where their SRC occurred (19%), having trouble keeping thoughts about sustaining the SRC out of their heads (18%), experiencing flashbacks of sustaining the SRC (13%), and having nightmares about sustaining the SRC (8%).14 Posttraumatic stress disorder may have a negative impact on an athlete’s performance because a fear of re-injury might lead them to avoid rehabilitation exercises and inhibit their effort.15-18

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is commonly comorbid with SRC.19,20 It is not known if pre-existing ADHD makes sustaining a concussion more likely (eg, because the athlete is distractible and thus does not notice when an opponent is about to hit them hard) and/or if a history of concussion makes ADHD more likely to develop (eg, because something about the concussed brain is changed in a way that leads to ADHD). Additionally, in some cases, ADHD has been associated with prolonged recovery from SRC.3,21

Immediate medical evaluation and cognitive assessment

Any patient in whom an SRC is suspected should undergo a medical evaluation immediately, whether in a physician’s office, emergency department, or on the sideline of a sports event. This medical evaluation should incorporate a clinical neurologic assessment, including evaluation of mental status/cognition, oculomotor function, gross sensorimotor, coordination, gait, vestibular function, and balance.3

Continue to: There is no single guideline...

There is no single guideline on how and when a neuropsychology referral is warranted.22 Insurance coverage for neurocognitive testing varies. Regardless of formal referral to neuropsychology, assessment of cognitive function is an important aspect of SRC management and is a factor in return-to-school and return-to-play decisions.3,22 Screening tools, such as the SCAT5, are useful in acute and subacute settings (ie, up to 3 to 5 days after injury); clinicians often use serial monitoring to track the resolution of symptoms.3 If pre-season baseline cognitive test results are available, clinicians may compare them to post-SRC results, but this should not be the sole basis of management decisions.3,22

Diagnosing psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC

Diagnosis of psychiatric symptoms and disorders associated with SRC can be challenging.7 There are no concussion-specific rating scales or diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders unique to patients who have sustained SRC. As a result, clinicians are left to use standard DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC. Importantly, psychiatric symptoms must be distinguished from disorders. For example, Kontos et al23 reported significantly worse depressive symptoms following SRC, but not at the level to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder. This is an important distinction, because a psychiatrist might be less likely to initiate pharmacotherapy for a patient with SRC who has only a few depressive symptoms and is only 1 week post-SRC, vs for one who has had most symptoms of a major depressive episode for several weeks.

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine has proposed 6 overlapping clinical profiles in patients with SRC (see the Table).24 Most patients with SRC have features of multiple clinical profiles.24 Anxiety/mood is one of these profiles. The impetus for developing these profiles was the recognition of heterogeneity among concussion presentations. Identification of the clinical profile(s) into which a patient’s symptoms fall might allow for more specific prognostication and targeted treatment.24 For example, referral to a psychiatrist obviously would be appropriate for a patient for whom anxiety/mood symptoms are prominent.

Treatment options for psychiatric sequelae of SRC

Both psychosocial and medical principles of management of psychiatric manifestations of SRC are important. Psychosocially, clinicians should address factors that may contribute to delayed SRC recovery (Box 225-30).

Box 2

- Recommend a progressive increase in exercise after a brief period of rest (often ameliorates psychiatric symptoms, as opposed to the historical approach of “cocoon therapy” in which the patient was to rest for prolonged periods of time in a darkened room so as to minimize brain stimulation)25

- Allow social activities, including team meetings (restriction of such activities has been associated with increased post-SRC depression)26

- Encourage members of the athlete’s “entourage” (team physicians, athletic trainers, coaches, teammates, and parents) to provide support27

- Educate coaches and teammates about how to make supportive statements because they often have trouble knowing how to do so27

- Recommend psychotherapy for mental and other physical symptoms of SRC that are moderate to severe or that persist longer than 4 weeks after the SRC28

- Recommend minimization of use of alcohol and other substances29,30

SRC: sport-related concussion

No medications are FDA-approved for SRC or associated psychiatric symptoms, and there is minimal evidence to support the use of specific medications.31 Most athletes with SRC recover quickly—typically within 2 weeks—and do not need medication.4,32 When medications are needed, start with low dosing and titrate slowly.33,34

Continue to: For patients with SRC who experience insomnia...

For patients with SRC who experience insomnia, clinicians should focus on sleep hygiene and, if needed, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).31 If medication is needed, melatonin may be a first-line agent.31,35,36 Trazodone may be a second option.32 Benzodiazepines typically are avoided because of their negative impact on cognition.31

For patients with SRC who have depression, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may simultaneously improve depressed mood31 and cognition.37 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are sometimes used to treat headaches, depression, anxiety, and/or insomnia after SRC,32 but adverse effects such as sedation and weight gain may limit their use in athletes. Theoretically, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors might have some of the same benefits as TCAs with fewer adverse effects, but they have not been well studied in patients with SRC.

For patients with SRC who have cognitive dysfunction (eg, deficits in attention and processing speed), there is some evidence for treatment with stimulants.31,37 However, these medications are prohibited by many athletic governing organizations, including professional sports leagues, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), and the World Anti-Doping Agency.4 If an athlete was receiving stimulants for ADHD before sustaining an SRC, there is no evidence that these medications should be stopped.

Consider interdisciplinary collaboration

Throughout the course of management, psychiatrists should consider if and when it is necessary to consult with other specialties such as primary care, sports medicine, neurology, and neuropsychology. As with many psychiatric symptoms and disorders, collaboration with an interdisciplinary team is recommended. Primary care, sports medicine, or neurology should be involved in the management of patients with SRC. Choice of which of those 3 specialties in particular will depend on comfort level and experience with managing SRC of the individual providers in question as well as availability of each provider type in a given community.

Additionally, psychiatrists may wonder if and when they should refer patients with SRC for neuroimaging. Because SRC is a functional, rather than structural, brain disturbance, neuroimaging is not typically pursued because results would be expected to be normal.3 However, when in doubt, consultation with the interdisciplinary team can guide this decision. Factors that may lead to a decision to obtain neuroimaging include:

- an abnormal neurologic examination

- prolonged loss of consciousness

- unexpected persistence of symptoms (eg, 6 to 12 weeks)

- worsening symptoms.22

Continue to: If imaging is deemed necessary...

If imaging is deemed necessary for a patient with an acute SRC, brain CT is typically the imaging modality of choice; however, if imaging is deemed necessary due to the persistence of symptoms, then MRI is often the preferred test because it provides more detailed information and does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation.22 While results are often normal, the ordering clinician should be prepared for the possibility of incidental findings, such as cysts or aneurysms, and the need for further consultation with other clinicians to weigh in on such findings.22

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. J is prescribed extended-release venlafaxine, 37.5 mg every morning for 5 days, and then is switched to 75 mg every morning. The psychiatrist hopes that venlafaxine might simultaneously offer benefit for Ms. J’s depression and migraine headaches. Venlafaxine is not FDA-approved for migraine, and there is more evidence supporting TCAs for preventing migraine. However, Ms. J is adamant that she does not want to take a medication, such as a TCA, that could cause weight gain or sedation, which could be problematic in her sport. The psychiatrist also tells Ms. J to avoid substances of abuse, and emphasizes the importance of good sleep hygiene. Finally, the psychiatrist communicates with the interdisciplinary medical team, which is helping Ms. J with gradual return-to-school and return-to-sport strategies and ensuring continued social involvement with the team even as she is held out from sport.

Ultimately, Ms. J’s extended-release venlafaxine is titrated to 150 mg every morning. After 2 months on this dose, her depressive symptoms remit. After her other symptoms remit, Ms. J has difficulty returning to certain practice drills that remind her of what she was doing when she sustained the SRC. She says that while participating in these drills, she has intrusive thoughts and images of the experience of her most recent concussion. She works with her psychiatrist on a gradual program of exposure therapy so she can return to all types of practice. Ms. J says she wishes to continue playing volleyball; however, together with her parents and treatment team, she decides that any additional SRCs might lead her to retire from the sport.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric symptoms are common after sport-related concussion (SRC). The nature of the relationship between concussion and mental health is not firmly established. Post-SRC psychiatric symptoms need to be carefully managed to avoid unnecessary treatment or restrictions.

Related Resources

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. Concussion. www.ncaa.org/sport-science-institute/concussion.

- American Academy of Neurology. Sports concussion resources. www.aan.com/tools-and-resources/practicing-neurologists-administrators/patient-resources/sports-concussion-resources. Published 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Trazodone • Desyrel

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Morgan CD, Zuckerman SL, Lee YM, et al. Predictors of postconcussion syndrome after sports-related concussion in young athletes: a matched case-control study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15(6):589-598.

2. Jorge RE, Arciniegas DB. Mood disorders after TBI. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(1):13-29.

3. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvor˘ák J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th International Conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):838-847.

4. Reardon CL, Hainline B, Aron CM, et al. Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(11):667-699.

5. Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The sport concussion assessment tool 5th edition (SCAT5): background and rationale. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:848-850.

6. Thompson E. Hamilton rating scale for anxiety (HAM-A). Occup Med. 2015;65(7):601.

7. Rice SM, Parker AG, Rosenbaum S, et al. Sport-related concussion outcomes in elite athletes: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2018;48(2):447-465.

8. Vargas G, Rabinowitz A, Meyer J, et al. Predictors and prevalence of postconcussion depression symptoms in collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2015;50(3):250-255.

9. Hutchison MG, Di Battista AP, McCoskey J, et al. Systematic review of mental health measures associated with concussive and subconcussive head trauma in former athletes. Int J Psychophysiol. 2018;132(Pt A):55-61.

10. Kerr GA, Stirling AE. Parents’ reflections on their child’s experiences of emotionally abusive coaching practices. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2012;24(2):191-206.

11. Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Bailes J, et al. Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(6):903-909.