User login

From paranoid fear to completed homicide

A crescendo of paranoid fear sharply increases the likelihood that a person will kill his (her) misperceived persecutor. Persecutory delusions are more likely to lead to homicide than any other psychiatric symptom.1 If people define a delusional situation as real, the situation is real in its consequences.

Based on my experience performing more than 100 insanity evaluations of paranoid persons charged with murder, I have identified 4 paranoid motives for homicide.

Self-defense. The most common paranoid motive for murder is the misperceived need to defend one’s self.

A steel worker believed that there was a conspiracy to kill him. His wife insisted that he go to a hospital emergency room for an evaluation. He then concluded that his wife was in on the conspiracy and stabbed her to death.

Defense of one’s manhood. Homosexual panic occurs in men who think of themselves as heterosexual.

A man with paranoid schizophrenia developed a delusion that his former high school football coach was having the entire team rape him at night. He shot the coach 6 times in front of 22 witnesses.

Defense of one’s children. A parent may kill to save her (his) children’s souls.

A deeply religious woman developed persecutory delusions that her 9-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter were going to be kidnapped and forced to make child pornography. To save her children’s souls, she stabbed her children more than 100 times.

Defense of the world. Homicide may be seen as a way to protect all humankind.

A woman developed a delusion that her father was Satan and would kill her. She believed that if she could kill her father (Satan) and his family she would save herself and bring about world peace. After killing her father, she thrust the sharp end of a tire iron into her grandmother’s umbilicus and vagina because those body parts were involved in “birthing Satan.”

Questioning to determine risk

I have found that, when evaluating a paranoid, delusional person for potential violence, it is better to present that person with a hypothetical question about encountering his perceived persecutor than with a generic question about homicidality.2 For example, a delusional person who reports that he was afraid of being killed by the Mafia could be asked, “If you were walking down an alley and encountered a man dressed like a Mafia hit man with a bulge in his jacket, what would you do?” One interviewee might reply, “The Mafia has so much power there is nothing I could do.” Another might answer, “As soon as I got close enough I would blow his head off with my .357 Magnum.” Although both people would be reporting honestly that they have no homicidal ideas, the latter has a much lower threshold for killing in misperceived self-defense.

Summing up

Persecutory delusions are more likely than any other psychiatric symptom to lead a psychotic person to commit homicide. The killing might be motivated by misperceived self-defense, defense of one’s manhood, defense of one’s children, or defense of the world.

A crescendo of paranoid fear sharply increases the likelihood that a person will kill his (her) misperceived persecutor. Persecutory delusions are more likely to lead to homicide than any other psychiatric symptom.1 If people define a delusional situation as real, the situation is real in its consequences.

Based on my experience performing more than 100 insanity evaluations of paranoid persons charged with murder, I have identified 4 paranoid motives for homicide.

Self-defense. The most common paranoid motive for murder is the misperceived need to defend one’s self.

A steel worker believed that there was a conspiracy to kill him. His wife insisted that he go to a hospital emergency room for an evaluation. He then concluded that his wife was in on the conspiracy and stabbed her to death.

Defense of one’s manhood. Homosexual panic occurs in men who think of themselves as heterosexual.

A man with paranoid schizophrenia developed a delusion that his former high school football coach was having the entire team rape him at night. He shot the coach 6 times in front of 22 witnesses.

Defense of one’s children. A parent may kill to save her (his) children’s souls.

A deeply religious woman developed persecutory delusions that her 9-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter were going to be kidnapped and forced to make child pornography. To save her children’s souls, she stabbed her children more than 100 times.

Defense of the world. Homicide may be seen as a way to protect all humankind.

A woman developed a delusion that her father was Satan and would kill her. She believed that if she could kill her father (Satan) and his family she would save herself and bring about world peace. After killing her father, she thrust the sharp end of a tire iron into her grandmother’s umbilicus and vagina because those body parts were involved in “birthing Satan.”

Questioning to determine risk

I have found that, when evaluating a paranoid, delusional person for potential violence, it is better to present that person with a hypothetical question about encountering his perceived persecutor than with a generic question about homicidality.2 For example, a delusional person who reports that he was afraid of being killed by the Mafia could be asked, “If you were walking down an alley and encountered a man dressed like a Mafia hit man with a bulge in his jacket, what would you do?” One interviewee might reply, “The Mafia has so much power there is nothing I could do.” Another might answer, “As soon as I got close enough I would blow his head off with my .357 Magnum.” Although both people would be reporting honestly that they have no homicidal ideas, the latter has a much lower threshold for killing in misperceived self-defense.

Summing up

Persecutory delusions are more likely than any other psychiatric symptom to lead a psychotic person to commit homicide. The killing might be motivated by misperceived self-defense, defense of one’s manhood, defense of one’s children, or defense of the world.

A crescendo of paranoid fear sharply increases the likelihood that a person will kill his (her) misperceived persecutor. Persecutory delusions are more likely to lead to homicide than any other psychiatric symptom.1 If people define a delusional situation as real, the situation is real in its consequences.

Based on my experience performing more than 100 insanity evaluations of paranoid persons charged with murder, I have identified 4 paranoid motives for homicide.

Self-defense. The most common paranoid motive for murder is the misperceived need to defend one’s self.

A steel worker believed that there was a conspiracy to kill him. His wife insisted that he go to a hospital emergency room for an evaluation. He then concluded that his wife was in on the conspiracy and stabbed her to death.

Defense of one’s manhood. Homosexual panic occurs in men who think of themselves as heterosexual.

A man with paranoid schizophrenia developed a delusion that his former high school football coach was having the entire team rape him at night. He shot the coach 6 times in front of 22 witnesses.

Defense of one’s children. A parent may kill to save her (his) children’s souls.

A deeply religious woman developed persecutory delusions that her 9-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter were going to be kidnapped and forced to make child pornography. To save her children’s souls, she stabbed her children more than 100 times.

Defense of the world. Homicide may be seen as a way to protect all humankind.

A woman developed a delusion that her father was Satan and would kill her. She believed that if she could kill her father (Satan) and his family she would save herself and bring about world peace. After killing her father, she thrust the sharp end of a tire iron into her grandmother’s umbilicus and vagina because those body parts were involved in “birthing Satan.”

Questioning to determine risk

I have found that, when evaluating a paranoid, delusional person for potential violence, it is better to present that person with a hypothetical question about encountering his perceived persecutor than with a generic question about homicidality.2 For example, a delusional person who reports that he was afraid of being killed by the Mafia could be asked, “If you were walking down an alley and encountered a man dressed like a Mafia hit man with a bulge in his jacket, what would you do?” One interviewee might reply, “The Mafia has so much power there is nothing I could do.” Another might answer, “As soon as I got close enough I would blow his head off with my .357 Magnum.” Although both people would be reporting honestly that they have no homicidal ideas, the latter has a much lower threshold for killing in misperceived self-defense.

Summing up

Persecutory delusions are more likely than any other psychiatric symptom to lead a psychotic person to commit homicide. The killing might be motivated by misperceived self-defense, defense of one’s manhood, defense of one’s children, or defense of the world.

Delusions, hypersexuality, and a steep cognitive decline

CASE Inconsistent stories

Ms. P, age 56, is an Asian American woman who was brought in by police after being found standing by her car in the middle of a busy road displaying bizarre behavior. She provides an inconsistent story about why she was brought to the hospital, saying that the police did so because she wasn’t driving fast enough and because her English is weak. At another point, she says that she had stopped her car to pick up a penny from the road and the police brought her to the hospital “to experience life, to rest, to meet people.”

Upon further questioning, Ms. P reveals that she is experiencing racing thoughts, feels full of energy, has pressured speech, and does not need much sleep. She also is sexually preoccupied, talks about having extra-marital affairs, and expresses her infatuation with TV news anchors. She says she is sexually active but is unable to offer any further details, and—while giggling—asks the treatment team not to reveal this information to her husband. Ms. P also reports hearing angels singing from the sky.

Chart review reveals that Ms. P had been admitted to same hospital 5 years earlier, at which time she was given diagnoses of late-onset schizophrenia (LOS) and mild cognitive impairment. Ms. P also had 3 psychiatric inpatient admissions in the past 2 years at a different hospital, but her records are inaccessible because she refuses to allow her chart to be released.

Ms. P has not taken the psychiatric medications prescribed for her for several months; she says, “I don’t need medication. I am self-healing.” She denies using illicit substances, including marijuana, smoking, and current alcohol use, but reports occasional social drinking in the past. Her urine drug screen is negative.

The most striking revelation in Ms. P’s social history is her high premorbid functional status. She has 2 master’s degrees and had been working as a senior accountant at a major hospital system until 7 years ago. In contrast, when interviewed at the hospital, Ms. P reports that she is working at a child care center.

On mental status exam, Ms. P is half-draped in a hospital gown, casual, overly friendly, smiling, and twirling her hair. Her mood is elevated with inappropriate affect. Her thought process is bizarre and illogical. She is alert, fully oriented, and her sensorium is clear. She has persistent ambivalence and contradictory thoughts regarding suicidal ideation. Recent and remote memory are largely intact. She does not express homicidal ideation.

What could be causing Ms. P’s psychosis and functional decline?

a) major neurocognitive disorder

b) schizophrenia

c) schizoaffective disorder

d) bipolar disorder, current manic episode

HISTORY Fired from her job

According to Ms. P’s chart from her admission 5 years earlier, police brought her to the hospital because she was causing a disturbance at a restaurant. When interviewed, Ms. P reported a false story that she fought with her husband, kicked him, and spat on his face. She said that her husband then punched her in the face, she ran out of the house, and a bystander called the police. At the time, her husband was contacted and denied the incident. He said that Ms. P had gone to the store and not returned, and he did not know what happened to her.

Her husband reported a steady and progressive decline in function and behavior dating back to 8 years ago with no known prior behavioral disturbances. In the chart from 5 years ago, her husband reported that Ms. P had been a high-functioning senior executive accountant at a major hospital system 7 years before the current admission, at which time she was fired from her job. He said that, just before being fired, Ms. P had been reading the mystery novel The Da Vinci Code and believed that events in the book specifically applied to her. Ms. P would stay up all night making clothes; when she would go to work, she was caught sleeping on the job and performing poorly, including submitting reports with incorrect information. She yelled at co-workers and was unable to take direction from her supervisors.

Ms. P’s husband also reported that she believed people were trying to “look like her,” by having plastic surgery. He reported unusual behavior at home, including eating food off the countertop that had been out for hours and was not fit for consumption.

Ms. P’s husband could not be contacted during this admission because he was out of country and they were separated. Collateral information is obtained from Ms. P’s mother, who lives apart from her but in the same city and speaks no English. She confirms Ms. P’s high premorbid functioning, and reports that her daughter’s change in behavior went back as far as 10 years. She reports that Ms. P had problems controlling anger and had frequent altercations with her husband and mother, including threatening her with a knife. Self-care and hygiene then declined strikingly. She began to have odd religious beliefs (eg, she was the daughter of Jesus Christ) and insisted on dressing in peculiar ways.

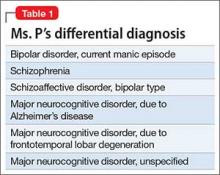

No family history of psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or dementia, was reported (Table 1).

The authors’ observations

The existence of LOS as a distinct subtype of schizophrenia has been the subject of discussion and controversy as far back as Manfred Bleuler in 1943 who coined the term “late-onset schizophrenia.”1 In 2000, a consensus statement by the International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group standardized the nomenclature, defining LOS as onset between age 40 and 60, and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOS) as onset after age 60.2 Although there is no diagnostic subcategory for LOS in DSM, DSM-5 notes that (1) women are overrepresented in late-onset cases and (2) the course generally is characterized by a predominance of psychotic symptoms with preservation of affect and social functioning.3 DSM authors comment that it is not yet clear whether LOS is the same condition as schizophrenia diagnosed earlier in life. Approximately 23% of schizophrenia cases have onset after age 40.4

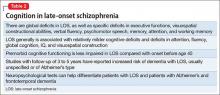

Cognitive symptoms in LOS

The presence of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia is common and well-recognized. The intellectual impairment is generalized and global, and there also is specific impairment in a range of cognitive functions, such as executive functions, memory, psychomotor speed, attention, and social cognition.5 Typically these cognitive impairments are present before onset of psychotic symptoms. Although cognitive symptoms are not part of the formal diagnostic criteria, DSM-5 acknowledges their presence.3 In a systematic review on nature and course of cognitive function in LOS, Rajji and Mulsant6 report that global deficits and specific deficits in executive functions, visuospatial constructional abilities, verbal fluency, and psychomotor speech have been found consistently in studies of LOS, although the presence of deficits in memory, attention, and working memory has been less consistent.

The presence of cognitive symptoms in LOS is less well-studied and understood (Table 2). The International Consensus Statement reported that no difference in type of cognitive deficit has been found in early–onset cases (onset before age 40) compared with late-onset cases, although LOS is associated with relatively milder cognitive deficits. Additionally, premorbid educational, occupational, and psychosocial functioning are less impaired in LOS than they are in early-onset schizophrenia.2

Rajji et al7 performed a meta-analysis comparison of patients with youth-onset schizophrenia, adults with first-episode schizophrenia, and those with LOS on their cognitive profiles. They reported that patients with youth-onset schizophrenia have globally severe cognitive deficits, whereas those with LOS demonstrate minimal deficits on arithmetic, digit symbol coding, and vocabulary but larger deficits on attention, fluency, global cognition, IQ, and visuospatial construction.7

There are conflicting views in the literature with regards to the course of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. One group of researchers believes that there is progressive deterioration in cognitive functioning over time, while another maintains that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is largely “a static encephalopathy” with no significant progression of symptoms.8 A number of studies referenced by Rajji and Mulsant6 in their systematic review report that cognitive deficits seen in patients with LOS largely are stable on follow-up with an average duration of up to 3 years. However, 2 studies with longer follow-up report evidence of cognitive decline.9,10

Relevant findings from the literature. Brodaty et al9 followed 27 patients with LOS without dementia and 34 otherwise healthy participants at baseline, 1 year, and 5 years. They reported that 9 patients with LOS and none of the control group were found to have dementia (5 Alzheimer type, 1 vascular, and 3 dementia of unknown type) at 5-year follow-up. Some patients had no clinical signs of dementia at baseline or at 1-year follow-up, but were found to have dementia at 5-year follow-up. The authors speculated that LOS might be a prodrome of Alzheimer-type dementia.

Kørner et al10 studied 12,600 patients with LOS and 7,700 with VLOS, selected from the Danish nationwide registry; follow-up was 3 to 4.58 years. They concluded that patients with LOS and VLOS were at 2 to 3 times greater risk of developing dementia than patients with osteoarthritis or the general population. The most common diagnosis among patients with schizophrenia was unspecified dementia, with Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) being the most common diagnosis in control groups. The findings suggest that dementia in LOS and VLOS has a different basis than AD.

Zakzanis et al11 investigated which neuropsychological tests best differentiate patients with LOS and those with AD or frontotemporal dementia. They reported that Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) Similarities subtest and the California Verbal Learning Test (both short- and long-delay free recall) can differentiate LOS from AD, and a test battery comprising the WAIS-R Vocabulary, Information, Digit Span, and Comprehension subtests, and the Hooper Visual Organization test can differentiate LOS and frontotemporal dementia.12

EVALUATION Significant impairment

CT head and MRI brain scans without contrast suggest mild generalized atrophy that is more prominent in frontal and parietal areas, but the scans are otherwise unremarkable overall. A PET scan is significant for hypoactivity in the temporal and parietal lobes but, again, the images are interpreted as unremarkable overall.

Ms. P scores 21 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicative of significant cognitive impairment (normal score, ≥26). This is a 3-point decline on a MoCA performed during her admission 5 years earlier.

Ms. P scores 8 on the Middlesex Elderly Assessment of Mental State, the lowest score in the borderline range of cognitive function for geriatric patients. She scores 13 on the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills, indicating that she needs maximal supervision, structure, and support to live in the community. Particularly notable is that Ms. P failed 5 out of 6 subtests in money management—a marked decline for someone who had worked as a senior accountant.

Given Ms. P’s significant cognitive decline from premorbid functioning, verified by collateral information, and current cognitive deficits established on standardized tests, we determine that, in addition to a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, she might meet DSM-5 criteria for unspecified major neurocognitive disorder if her functioning does not improve with treatment.

The authors’ observations

There is scant literature on late-onset schizoaffective disorder. Webster and Grossberg13 conducted a retrospective chart review of 1,730 patients age >65 who were admitted to a geriatric psychiatry unit from 1988 to 1995. Of these patients, 166 (approximately 10%) were found to have late life-onset psychosis. The psychosis was attributed to various causes, such as dementia, depression, bipolar disorder, medical causes, delirium, medication toxicity. Two patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 2 were diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (the authors did not provide additional information about the patients with schizoaffective disorder). Brenner et al14 reports a case of late-onset schizoaffective disorder in a 70-year-old female patient. Evans et al15 compared outpatients age 45 to 77 with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (n = 29), schizophrenia (n = 154), or nonpsychotic mood disorder (n = 27) and concluded that late-onset schizoaffective disorder might represent a variant of LOS in clinical symptom profiles and cognitive impairment but with additional mood symptoms.16

How would you begin treating Ms. P?

a) start a mood stabilizer

b) start an atypical antipsychotic

c) obtain more history and collateral information

d) recommend outpatient treatment

The authors’ observations

Given Ms. P’s manic symptoms, thought disorder, and history of psychotic symptoms with diagnosis of LOS, we assigned her a presumptive diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. From the patient report, collateral information from her mother, earlier documented collateral from her husband, and chart review, it was apparent to us that Ms. P’s psychiatric history went back only 10 years—therefore meeting temporal criteria for LOS.

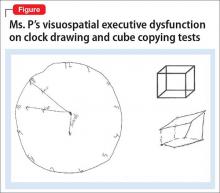

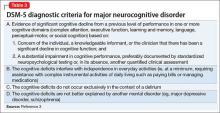

Clinical assessment (Figure) and standardized tests revealed the presence of neurocognitive deficits sufficient to meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder (Table 33). The pattern of neurocognitive deficits is consistent with an AD-like amnestic picture, although no clear-cut diagnosis was present, and the neurocognitive disorder was better classified as unspecified rather than of a particular type. It remains uncertain whether cognitive deficits of severity that meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder are sufficiently accounted for by the diagnosis of LOS alone. Unless diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia are expanded to include cognitive deficits, a separate diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder is warranted at present.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy

On the unit, Ms. P is observed by nursing staff wandering, with some pressured speech but no behavioral agitation. Her clothing had been bizarre, with multiple layers, and, at one point, she walks with her gown open and without undergarments. She also reports to the nurses that she has a lot of sexual thoughts. When the interview team enters her room, they find her masturbating.

Ms. P is started on aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, titrated to 20 mg/d, and divalproex sodium, 500 mg/d. The decision to initiate a cognitive enhancer, such as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, is deferred to outpatient care to allow for the possibility that her cognitive features will improve after the psychosis is treated.

By the end of first week, Ms. P’s manic features are no longer prominent but her thought process continues to be bizarre, with poor insight and judgment. She demonstrates severe ambivalence in all matters, consistently gives inconsistent accounts of the past, and makes dramatic false statements.

For example, when asked about her children, Ms. P tells us that she has 6 children—the youngest 3 months old, at home by himself and “probably dead by now.” In reality, she has only a 20-year-old son who is studying abroad. Talking about her marriage, Ms. P says she and her husband are not divorced on paper but that, because they haven’t had sex for 8 years, the law has provided them with an automatic divorce.

OUTCOME Significant improvement

Ms. P shows significant response to aripiprazole and divalproex, which are well tolerated without significant adverse effects. Her limitations in executive functioning and rational thought process lead the treatment team to consider nursing home placement under guardianship. Days before discharge, however, reexamination of her neuropsychiatric state suggests significant improvement in thought process, with improvement in cognitive features. Ms. P also becomes cooperative with treatment planning.

The treatment team has meetings with Ms. P’s mother to discuss monitoring and plans for discharge. Ms. P is discharged with follow-up arranged at community mental health services.

Bottom Line

Global as well as specific cognitive deficits are associated with late-onset schizophrenia. Studies have reported increased risk of dementia in these patients over the course of 3 to 5 years, usually unspecified or Alzheimer’s type. It is imperative to assess patients with schizophrenia, especially those age ≥40, for presence of neurocognitive disorder by means of neurocognitive testing.

Related Resources

- Goff DC, Hill M, Barch D. The treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):245-253.

- Radhakrishnan R, Butler R, Head L. Dementia in schizophrenia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2012;18(2):144-153.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Mematine • Namenda

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturer of competing products.

1. Bleuler M. Die spätschizophrenen Krankheitsbilder. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 1943;15:259-290.

2. Howard R, Rabins PV, Seeman MV, et al. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. The International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group. Am J Psychiatry. 2000; 157(2):172-178.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Harris MJ, Jeste DV. Late-onset schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14(1):39-55.

5. Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, “just the facts”: what we know in 2008 part 1: overview. Schizophr Res. 2008;100(1):4-19.

6. Rajji TK, Mulsant BH. Nature and course of cognitive function in late-life schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1-3):122-140.

7. Rajji TK, Ismail Z, Mulsant BH. Age at onset and cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(4):286-293.

8. Goldberg TE, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, et al. Course of schizophrenia: neuropsychological evidence for a static encephalopathy. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(4):797-804.

9. Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Koschera A, et al. Long-term outcome of late-onset schizophrenia: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183(3):213-219.

10. Kørner A, Lopez AG, Lauritzen L, et al. Late and very-late first‐contact schizophrenia and the risk of dementia—a nationwide register based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(1):61-67.

11. Zakzanis KK, Andrikopoulos J, Young DA, et al. Neuropsychological differentiation of late-onset schizophrenia and dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Appl Neuropsychol. 2003;10(2):105-114.

12. Zakzanis KK, Kielar A, Young DA, et al. Neuropsychological differentiation of late onset schizophrenia and frontotemporal dementia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2001;6(1):63-77.

13. Webster J, Grossberg GT. Late-life onset of psychotic symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6(3):196-202.

14. Brenner R, Campbell K, Konakondla K, et al. Late onset schizoaffective disorder. Consultant. 2014;53(6):487-488.

15. Evans JD, Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, et al. Schizoaffective disorder: a form of schizophrenia or affective disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(12):874-882.

16. Jeste DV, Blazer DG, First M. Aging-related diagnostic variations: need for diagnostic criteria appropriate for elderly psychiatric patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(4):265-271.

CASE Inconsistent stories

Ms. P, age 56, is an Asian American woman who was brought in by police after being found standing by her car in the middle of a busy road displaying bizarre behavior. She provides an inconsistent story about why she was brought to the hospital, saying that the police did so because she wasn’t driving fast enough and because her English is weak. At another point, she says that she had stopped her car to pick up a penny from the road and the police brought her to the hospital “to experience life, to rest, to meet people.”

Upon further questioning, Ms. P reveals that she is experiencing racing thoughts, feels full of energy, has pressured speech, and does not need much sleep. She also is sexually preoccupied, talks about having extra-marital affairs, and expresses her infatuation with TV news anchors. She says she is sexually active but is unable to offer any further details, and—while giggling—asks the treatment team not to reveal this information to her husband. Ms. P also reports hearing angels singing from the sky.

Chart review reveals that Ms. P had been admitted to same hospital 5 years earlier, at which time she was given diagnoses of late-onset schizophrenia (LOS) and mild cognitive impairment. Ms. P also had 3 psychiatric inpatient admissions in the past 2 years at a different hospital, but her records are inaccessible because she refuses to allow her chart to be released.

Ms. P has not taken the psychiatric medications prescribed for her for several months; she says, “I don’t need medication. I am self-healing.” She denies using illicit substances, including marijuana, smoking, and current alcohol use, but reports occasional social drinking in the past. Her urine drug screen is negative.

The most striking revelation in Ms. P’s social history is her high premorbid functional status. She has 2 master’s degrees and had been working as a senior accountant at a major hospital system until 7 years ago. In contrast, when interviewed at the hospital, Ms. P reports that she is working at a child care center.

On mental status exam, Ms. P is half-draped in a hospital gown, casual, overly friendly, smiling, and twirling her hair. Her mood is elevated with inappropriate affect. Her thought process is bizarre and illogical. She is alert, fully oriented, and her sensorium is clear. She has persistent ambivalence and contradictory thoughts regarding suicidal ideation. Recent and remote memory are largely intact. She does not express homicidal ideation.

What could be causing Ms. P’s psychosis and functional decline?

a) major neurocognitive disorder

b) schizophrenia

c) schizoaffective disorder

d) bipolar disorder, current manic episode

HISTORY Fired from her job

According to Ms. P’s chart from her admission 5 years earlier, police brought her to the hospital because she was causing a disturbance at a restaurant. When interviewed, Ms. P reported a false story that she fought with her husband, kicked him, and spat on his face. She said that her husband then punched her in the face, she ran out of the house, and a bystander called the police. At the time, her husband was contacted and denied the incident. He said that Ms. P had gone to the store and not returned, and he did not know what happened to her.

Her husband reported a steady and progressive decline in function and behavior dating back to 8 years ago with no known prior behavioral disturbances. In the chart from 5 years ago, her husband reported that Ms. P had been a high-functioning senior executive accountant at a major hospital system 7 years before the current admission, at which time she was fired from her job. He said that, just before being fired, Ms. P had been reading the mystery novel The Da Vinci Code and believed that events in the book specifically applied to her. Ms. P would stay up all night making clothes; when she would go to work, she was caught sleeping on the job and performing poorly, including submitting reports with incorrect information. She yelled at co-workers and was unable to take direction from her supervisors.

Ms. P’s husband also reported that she believed people were trying to “look like her,” by having plastic surgery. He reported unusual behavior at home, including eating food off the countertop that had been out for hours and was not fit for consumption.

Ms. P’s husband could not be contacted during this admission because he was out of country and they were separated. Collateral information is obtained from Ms. P’s mother, who lives apart from her but in the same city and speaks no English. She confirms Ms. P’s high premorbid functioning, and reports that her daughter’s change in behavior went back as far as 10 years. She reports that Ms. P had problems controlling anger and had frequent altercations with her husband and mother, including threatening her with a knife. Self-care and hygiene then declined strikingly. She began to have odd religious beliefs (eg, she was the daughter of Jesus Christ) and insisted on dressing in peculiar ways.

No family history of psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or dementia, was reported (Table 1).

The authors’ observations

The existence of LOS as a distinct subtype of schizophrenia has been the subject of discussion and controversy as far back as Manfred Bleuler in 1943 who coined the term “late-onset schizophrenia.”1 In 2000, a consensus statement by the International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group standardized the nomenclature, defining LOS as onset between age 40 and 60, and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOS) as onset after age 60.2 Although there is no diagnostic subcategory for LOS in DSM, DSM-5 notes that (1) women are overrepresented in late-onset cases and (2) the course generally is characterized by a predominance of psychotic symptoms with preservation of affect and social functioning.3 DSM authors comment that it is not yet clear whether LOS is the same condition as schizophrenia diagnosed earlier in life. Approximately 23% of schizophrenia cases have onset after age 40.4

Cognitive symptoms in LOS

The presence of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia is common and well-recognized. The intellectual impairment is generalized and global, and there also is specific impairment in a range of cognitive functions, such as executive functions, memory, psychomotor speed, attention, and social cognition.5 Typically these cognitive impairments are present before onset of psychotic symptoms. Although cognitive symptoms are not part of the formal diagnostic criteria, DSM-5 acknowledges their presence.3 In a systematic review on nature and course of cognitive function in LOS, Rajji and Mulsant6 report that global deficits and specific deficits in executive functions, visuospatial constructional abilities, verbal fluency, and psychomotor speech have been found consistently in studies of LOS, although the presence of deficits in memory, attention, and working memory has been less consistent.

The presence of cognitive symptoms in LOS is less well-studied and understood (Table 2). The International Consensus Statement reported that no difference in type of cognitive deficit has been found in early–onset cases (onset before age 40) compared with late-onset cases, although LOS is associated with relatively milder cognitive deficits. Additionally, premorbid educational, occupational, and psychosocial functioning are less impaired in LOS than they are in early-onset schizophrenia.2

Rajji et al7 performed a meta-analysis comparison of patients with youth-onset schizophrenia, adults with first-episode schizophrenia, and those with LOS on their cognitive profiles. They reported that patients with youth-onset schizophrenia have globally severe cognitive deficits, whereas those with LOS demonstrate minimal deficits on arithmetic, digit symbol coding, and vocabulary but larger deficits on attention, fluency, global cognition, IQ, and visuospatial construction.7

There are conflicting views in the literature with regards to the course of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. One group of researchers believes that there is progressive deterioration in cognitive functioning over time, while another maintains that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is largely “a static encephalopathy” with no significant progression of symptoms.8 A number of studies referenced by Rajji and Mulsant6 in their systematic review report that cognitive deficits seen in patients with LOS largely are stable on follow-up with an average duration of up to 3 years. However, 2 studies with longer follow-up report evidence of cognitive decline.9,10

Relevant findings from the literature. Brodaty et al9 followed 27 patients with LOS without dementia and 34 otherwise healthy participants at baseline, 1 year, and 5 years. They reported that 9 patients with LOS and none of the control group were found to have dementia (5 Alzheimer type, 1 vascular, and 3 dementia of unknown type) at 5-year follow-up. Some patients had no clinical signs of dementia at baseline or at 1-year follow-up, but were found to have dementia at 5-year follow-up. The authors speculated that LOS might be a prodrome of Alzheimer-type dementia.

Kørner et al10 studied 12,600 patients with LOS and 7,700 with VLOS, selected from the Danish nationwide registry; follow-up was 3 to 4.58 years. They concluded that patients with LOS and VLOS were at 2 to 3 times greater risk of developing dementia than patients with osteoarthritis or the general population. The most common diagnosis among patients with schizophrenia was unspecified dementia, with Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) being the most common diagnosis in control groups. The findings suggest that dementia in LOS and VLOS has a different basis than AD.

Zakzanis et al11 investigated which neuropsychological tests best differentiate patients with LOS and those with AD or frontotemporal dementia. They reported that Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) Similarities subtest and the California Verbal Learning Test (both short- and long-delay free recall) can differentiate LOS from AD, and a test battery comprising the WAIS-R Vocabulary, Information, Digit Span, and Comprehension subtests, and the Hooper Visual Organization test can differentiate LOS and frontotemporal dementia.12

EVALUATION Significant impairment

CT head and MRI brain scans without contrast suggest mild generalized atrophy that is more prominent in frontal and parietal areas, but the scans are otherwise unremarkable overall. A PET scan is significant for hypoactivity in the temporal and parietal lobes but, again, the images are interpreted as unremarkable overall.

Ms. P scores 21 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicative of significant cognitive impairment (normal score, ≥26). This is a 3-point decline on a MoCA performed during her admission 5 years earlier.

Ms. P scores 8 on the Middlesex Elderly Assessment of Mental State, the lowest score in the borderline range of cognitive function for geriatric patients. She scores 13 on the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills, indicating that she needs maximal supervision, structure, and support to live in the community. Particularly notable is that Ms. P failed 5 out of 6 subtests in money management—a marked decline for someone who had worked as a senior accountant.

Given Ms. P’s significant cognitive decline from premorbid functioning, verified by collateral information, and current cognitive deficits established on standardized tests, we determine that, in addition to a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, she might meet DSM-5 criteria for unspecified major neurocognitive disorder if her functioning does not improve with treatment.

The authors’ observations

There is scant literature on late-onset schizoaffective disorder. Webster and Grossberg13 conducted a retrospective chart review of 1,730 patients age >65 who were admitted to a geriatric psychiatry unit from 1988 to 1995. Of these patients, 166 (approximately 10%) were found to have late life-onset psychosis. The psychosis was attributed to various causes, such as dementia, depression, bipolar disorder, medical causes, delirium, medication toxicity. Two patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 2 were diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (the authors did not provide additional information about the patients with schizoaffective disorder). Brenner et al14 reports a case of late-onset schizoaffective disorder in a 70-year-old female patient. Evans et al15 compared outpatients age 45 to 77 with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (n = 29), schizophrenia (n = 154), or nonpsychotic mood disorder (n = 27) and concluded that late-onset schizoaffective disorder might represent a variant of LOS in clinical symptom profiles and cognitive impairment but with additional mood symptoms.16

How would you begin treating Ms. P?

a) start a mood stabilizer

b) start an atypical antipsychotic

c) obtain more history and collateral information

d) recommend outpatient treatment

The authors’ observations

Given Ms. P’s manic symptoms, thought disorder, and history of psychotic symptoms with diagnosis of LOS, we assigned her a presumptive diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. From the patient report, collateral information from her mother, earlier documented collateral from her husband, and chart review, it was apparent to us that Ms. P’s psychiatric history went back only 10 years—therefore meeting temporal criteria for LOS.

Clinical assessment (Figure) and standardized tests revealed the presence of neurocognitive deficits sufficient to meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder (Table 33). The pattern of neurocognitive deficits is consistent with an AD-like amnestic picture, although no clear-cut diagnosis was present, and the neurocognitive disorder was better classified as unspecified rather than of a particular type. It remains uncertain whether cognitive deficits of severity that meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder are sufficiently accounted for by the diagnosis of LOS alone. Unless diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia are expanded to include cognitive deficits, a separate diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder is warranted at present.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy

On the unit, Ms. P is observed by nursing staff wandering, with some pressured speech but no behavioral agitation. Her clothing had been bizarre, with multiple layers, and, at one point, she walks with her gown open and without undergarments. She also reports to the nurses that she has a lot of sexual thoughts. When the interview team enters her room, they find her masturbating.

Ms. P is started on aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, titrated to 20 mg/d, and divalproex sodium, 500 mg/d. The decision to initiate a cognitive enhancer, such as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, is deferred to outpatient care to allow for the possibility that her cognitive features will improve after the psychosis is treated.

By the end of first week, Ms. P’s manic features are no longer prominent but her thought process continues to be bizarre, with poor insight and judgment. She demonstrates severe ambivalence in all matters, consistently gives inconsistent accounts of the past, and makes dramatic false statements.

For example, when asked about her children, Ms. P tells us that she has 6 children—the youngest 3 months old, at home by himself and “probably dead by now.” In reality, she has only a 20-year-old son who is studying abroad. Talking about her marriage, Ms. P says she and her husband are not divorced on paper but that, because they haven’t had sex for 8 years, the law has provided them with an automatic divorce.

OUTCOME Significant improvement

Ms. P shows significant response to aripiprazole and divalproex, which are well tolerated without significant adverse effects. Her limitations in executive functioning and rational thought process lead the treatment team to consider nursing home placement under guardianship. Days before discharge, however, reexamination of her neuropsychiatric state suggests significant improvement in thought process, with improvement in cognitive features. Ms. P also becomes cooperative with treatment planning.

The treatment team has meetings with Ms. P’s mother to discuss monitoring and plans for discharge. Ms. P is discharged with follow-up arranged at community mental health services.

Bottom Line

Global as well as specific cognitive deficits are associated with late-onset schizophrenia. Studies have reported increased risk of dementia in these patients over the course of 3 to 5 years, usually unspecified or Alzheimer’s type. It is imperative to assess patients with schizophrenia, especially those age ≥40, for presence of neurocognitive disorder by means of neurocognitive testing.

Related Resources

- Goff DC, Hill M, Barch D. The treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):245-253.

- Radhakrishnan R, Butler R, Head L. Dementia in schizophrenia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2012;18(2):144-153.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Mematine • Namenda

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturer of competing products.

CASE Inconsistent stories

Ms. P, age 56, is an Asian American woman who was brought in by police after being found standing by her car in the middle of a busy road displaying bizarre behavior. She provides an inconsistent story about why she was brought to the hospital, saying that the police did so because she wasn’t driving fast enough and because her English is weak. At another point, she says that she had stopped her car to pick up a penny from the road and the police brought her to the hospital “to experience life, to rest, to meet people.”

Upon further questioning, Ms. P reveals that she is experiencing racing thoughts, feels full of energy, has pressured speech, and does not need much sleep. She also is sexually preoccupied, talks about having extra-marital affairs, and expresses her infatuation with TV news anchors. She says she is sexually active but is unable to offer any further details, and—while giggling—asks the treatment team not to reveal this information to her husband. Ms. P also reports hearing angels singing from the sky.

Chart review reveals that Ms. P had been admitted to same hospital 5 years earlier, at which time she was given diagnoses of late-onset schizophrenia (LOS) and mild cognitive impairment. Ms. P also had 3 psychiatric inpatient admissions in the past 2 years at a different hospital, but her records are inaccessible because she refuses to allow her chart to be released.

Ms. P has not taken the psychiatric medications prescribed for her for several months; she says, “I don’t need medication. I am self-healing.” She denies using illicit substances, including marijuana, smoking, and current alcohol use, but reports occasional social drinking in the past. Her urine drug screen is negative.

The most striking revelation in Ms. P’s social history is her high premorbid functional status. She has 2 master’s degrees and had been working as a senior accountant at a major hospital system until 7 years ago. In contrast, when interviewed at the hospital, Ms. P reports that she is working at a child care center.

On mental status exam, Ms. P is half-draped in a hospital gown, casual, overly friendly, smiling, and twirling her hair. Her mood is elevated with inappropriate affect. Her thought process is bizarre and illogical. She is alert, fully oriented, and her sensorium is clear. She has persistent ambivalence and contradictory thoughts regarding suicidal ideation. Recent and remote memory are largely intact. She does not express homicidal ideation.

What could be causing Ms. P’s psychosis and functional decline?

a) major neurocognitive disorder

b) schizophrenia

c) schizoaffective disorder

d) bipolar disorder, current manic episode

HISTORY Fired from her job

According to Ms. P’s chart from her admission 5 years earlier, police brought her to the hospital because she was causing a disturbance at a restaurant. When interviewed, Ms. P reported a false story that she fought with her husband, kicked him, and spat on his face. She said that her husband then punched her in the face, she ran out of the house, and a bystander called the police. At the time, her husband was contacted and denied the incident. He said that Ms. P had gone to the store and not returned, and he did not know what happened to her.

Her husband reported a steady and progressive decline in function and behavior dating back to 8 years ago with no known prior behavioral disturbances. In the chart from 5 years ago, her husband reported that Ms. P had been a high-functioning senior executive accountant at a major hospital system 7 years before the current admission, at which time she was fired from her job. He said that, just before being fired, Ms. P had been reading the mystery novel The Da Vinci Code and believed that events in the book specifically applied to her. Ms. P would stay up all night making clothes; when she would go to work, she was caught sleeping on the job and performing poorly, including submitting reports with incorrect information. She yelled at co-workers and was unable to take direction from her supervisors.

Ms. P’s husband also reported that she believed people were trying to “look like her,” by having plastic surgery. He reported unusual behavior at home, including eating food off the countertop that had been out for hours and was not fit for consumption.

Ms. P’s husband could not be contacted during this admission because he was out of country and they were separated. Collateral information is obtained from Ms. P’s mother, who lives apart from her but in the same city and speaks no English. She confirms Ms. P’s high premorbid functioning, and reports that her daughter’s change in behavior went back as far as 10 years. She reports that Ms. P had problems controlling anger and had frequent altercations with her husband and mother, including threatening her with a knife. Self-care and hygiene then declined strikingly. She began to have odd religious beliefs (eg, she was the daughter of Jesus Christ) and insisted on dressing in peculiar ways.

No family history of psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or dementia, was reported (Table 1).

The authors’ observations

The existence of LOS as a distinct subtype of schizophrenia has been the subject of discussion and controversy as far back as Manfred Bleuler in 1943 who coined the term “late-onset schizophrenia.”1 In 2000, a consensus statement by the International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group standardized the nomenclature, defining LOS as onset between age 40 and 60, and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOS) as onset after age 60.2 Although there is no diagnostic subcategory for LOS in DSM, DSM-5 notes that (1) women are overrepresented in late-onset cases and (2) the course generally is characterized by a predominance of psychotic symptoms with preservation of affect and social functioning.3 DSM authors comment that it is not yet clear whether LOS is the same condition as schizophrenia diagnosed earlier in life. Approximately 23% of schizophrenia cases have onset after age 40.4

Cognitive symptoms in LOS

The presence of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia is common and well-recognized. The intellectual impairment is generalized and global, and there also is specific impairment in a range of cognitive functions, such as executive functions, memory, psychomotor speed, attention, and social cognition.5 Typically these cognitive impairments are present before onset of psychotic symptoms. Although cognitive symptoms are not part of the formal diagnostic criteria, DSM-5 acknowledges their presence.3 In a systematic review on nature and course of cognitive function in LOS, Rajji and Mulsant6 report that global deficits and specific deficits in executive functions, visuospatial constructional abilities, verbal fluency, and psychomotor speech have been found consistently in studies of LOS, although the presence of deficits in memory, attention, and working memory has been less consistent.

The presence of cognitive symptoms in LOS is less well-studied and understood (Table 2). The International Consensus Statement reported that no difference in type of cognitive deficit has been found in early–onset cases (onset before age 40) compared with late-onset cases, although LOS is associated with relatively milder cognitive deficits. Additionally, premorbid educational, occupational, and psychosocial functioning are less impaired in LOS than they are in early-onset schizophrenia.2

Rajji et al7 performed a meta-analysis comparison of patients with youth-onset schizophrenia, adults with first-episode schizophrenia, and those with LOS on their cognitive profiles. They reported that patients with youth-onset schizophrenia have globally severe cognitive deficits, whereas those with LOS demonstrate minimal deficits on arithmetic, digit symbol coding, and vocabulary but larger deficits on attention, fluency, global cognition, IQ, and visuospatial construction.7

There are conflicting views in the literature with regards to the course of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. One group of researchers believes that there is progressive deterioration in cognitive functioning over time, while another maintains that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is largely “a static encephalopathy” with no significant progression of symptoms.8 A number of studies referenced by Rajji and Mulsant6 in their systematic review report that cognitive deficits seen in patients with LOS largely are stable on follow-up with an average duration of up to 3 years. However, 2 studies with longer follow-up report evidence of cognitive decline.9,10

Relevant findings from the literature. Brodaty et al9 followed 27 patients with LOS without dementia and 34 otherwise healthy participants at baseline, 1 year, and 5 years. They reported that 9 patients with LOS and none of the control group were found to have dementia (5 Alzheimer type, 1 vascular, and 3 dementia of unknown type) at 5-year follow-up. Some patients had no clinical signs of dementia at baseline or at 1-year follow-up, but were found to have dementia at 5-year follow-up. The authors speculated that LOS might be a prodrome of Alzheimer-type dementia.

Kørner et al10 studied 12,600 patients with LOS and 7,700 with VLOS, selected from the Danish nationwide registry; follow-up was 3 to 4.58 years. They concluded that patients with LOS and VLOS were at 2 to 3 times greater risk of developing dementia than patients with osteoarthritis or the general population. The most common diagnosis among patients with schizophrenia was unspecified dementia, with Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) being the most common diagnosis in control groups. The findings suggest that dementia in LOS and VLOS has a different basis than AD.

Zakzanis et al11 investigated which neuropsychological tests best differentiate patients with LOS and those with AD or frontotemporal dementia. They reported that Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) Similarities subtest and the California Verbal Learning Test (both short- and long-delay free recall) can differentiate LOS from AD, and a test battery comprising the WAIS-R Vocabulary, Information, Digit Span, and Comprehension subtests, and the Hooper Visual Organization test can differentiate LOS and frontotemporal dementia.12

EVALUATION Significant impairment

CT head and MRI brain scans without contrast suggest mild generalized atrophy that is more prominent in frontal and parietal areas, but the scans are otherwise unremarkable overall. A PET scan is significant for hypoactivity in the temporal and parietal lobes but, again, the images are interpreted as unremarkable overall.

Ms. P scores 21 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicative of significant cognitive impairment (normal score, ≥26). This is a 3-point decline on a MoCA performed during her admission 5 years earlier.

Ms. P scores 8 on the Middlesex Elderly Assessment of Mental State, the lowest score in the borderline range of cognitive function for geriatric patients. She scores 13 on the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills, indicating that she needs maximal supervision, structure, and support to live in the community. Particularly notable is that Ms. P failed 5 out of 6 subtests in money management—a marked decline for someone who had worked as a senior accountant.

Given Ms. P’s significant cognitive decline from premorbid functioning, verified by collateral information, and current cognitive deficits established on standardized tests, we determine that, in addition to a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, she might meet DSM-5 criteria for unspecified major neurocognitive disorder if her functioning does not improve with treatment.

The authors’ observations

There is scant literature on late-onset schizoaffective disorder. Webster and Grossberg13 conducted a retrospective chart review of 1,730 patients age >65 who were admitted to a geriatric psychiatry unit from 1988 to 1995. Of these patients, 166 (approximately 10%) were found to have late life-onset psychosis. The psychosis was attributed to various causes, such as dementia, depression, bipolar disorder, medical causes, delirium, medication toxicity. Two patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 2 were diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (the authors did not provide additional information about the patients with schizoaffective disorder). Brenner et al14 reports a case of late-onset schizoaffective disorder in a 70-year-old female patient. Evans et al15 compared outpatients age 45 to 77 with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (n = 29), schizophrenia (n = 154), or nonpsychotic mood disorder (n = 27) and concluded that late-onset schizoaffective disorder might represent a variant of LOS in clinical symptom profiles and cognitive impairment but with additional mood symptoms.16

How would you begin treating Ms. P?

a) start a mood stabilizer

b) start an atypical antipsychotic

c) obtain more history and collateral information

d) recommend outpatient treatment

The authors’ observations

Given Ms. P’s manic symptoms, thought disorder, and history of psychotic symptoms with diagnosis of LOS, we assigned her a presumptive diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. From the patient report, collateral information from her mother, earlier documented collateral from her husband, and chart review, it was apparent to us that Ms. P’s psychiatric history went back only 10 years—therefore meeting temporal criteria for LOS.

Clinical assessment (Figure) and standardized tests revealed the presence of neurocognitive deficits sufficient to meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder (Table 33). The pattern of neurocognitive deficits is consistent with an AD-like amnestic picture, although no clear-cut diagnosis was present, and the neurocognitive disorder was better classified as unspecified rather than of a particular type. It remains uncertain whether cognitive deficits of severity that meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder are sufficiently accounted for by the diagnosis of LOS alone. Unless diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia are expanded to include cognitive deficits, a separate diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder is warranted at present.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy

On the unit, Ms. P is observed by nursing staff wandering, with some pressured speech but no behavioral agitation. Her clothing had been bizarre, with multiple layers, and, at one point, she walks with her gown open and without undergarments. She also reports to the nurses that she has a lot of sexual thoughts. When the interview team enters her room, they find her masturbating.

Ms. P is started on aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, titrated to 20 mg/d, and divalproex sodium, 500 mg/d. The decision to initiate a cognitive enhancer, such as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, is deferred to outpatient care to allow for the possibility that her cognitive features will improve after the psychosis is treated.

By the end of first week, Ms. P’s manic features are no longer prominent but her thought process continues to be bizarre, with poor insight and judgment. She demonstrates severe ambivalence in all matters, consistently gives inconsistent accounts of the past, and makes dramatic false statements.

For example, when asked about her children, Ms. P tells us that she has 6 children—the youngest 3 months old, at home by himself and “probably dead by now.” In reality, she has only a 20-year-old son who is studying abroad. Talking about her marriage, Ms. P says she and her husband are not divorced on paper but that, because they haven’t had sex for 8 years, the law has provided them with an automatic divorce.

OUTCOME Significant improvement

Ms. P shows significant response to aripiprazole and divalproex, which are well tolerated without significant adverse effects. Her limitations in executive functioning and rational thought process lead the treatment team to consider nursing home placement under guardianship. Days before discharge, however, reexamination of her neuropsychiatric state suggests significant improvement in thought process, with improvement in cognitive features. Ms. P also becomes cooperative with treatment planning.

The treatment team has meetings with Ms. P’s mother to discuss monitoring and plans for discharge. Ms. P is discharged with follow-up arranged at community mental health services.

Bottom Line

Global as well as specific cognitive deficits are associated with late-onset schizophrenia. Studies have reported increased risk of dementia in these patients over the course of 3 to 5 years, usually unspecified or Alzheimer’s type. It is imperative to assess patients with schizophrenia, especially those age ≥40, for presence of neurocognitive disorder by means of neurocognitive testing.

Related Resources

- Goff DC, Hill M, Barch D. The treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):245-253.

- Radhakrishnan R, Butler R, Head L. Dementia in schizophrenia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2012;18(2):144-153.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Mematine • Namenda

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturer of competing products.

1. Bleuler M. Die spätschizophrenen Krankheitsbilder. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 1943;15:259-290.

2. Howard R, Rabins PV, Seeman MV, et al. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. The International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group. Am J Psychiatry. 2000; 157(2):172-178.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Harris MJ, Jeste DV. Late-onset schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14(1):39-55.

5. Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, “just the facts”: what we know in 2008 part 1: overview. Schizophr Res. 2008;100(1):4-19.

6. Rajji TK, Mulsant BH. Nature and course of cognitive function in late-life schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1-3):122-140.

7. Rajji TK, Ismail Z, Mulsant BH. Age at onset and cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(4):286-293.

8. Goldberg TE, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, et al. Course of schizophrenia: neuropsychological evidence for a static encephalopathy. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(4):797-804.

9. Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Koschera A, et al. Long-term outcome of late-onset schizophrenia: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183(3):213-219.

10. Kørner A, Lopez AG, Lauritzen L, et al. Late and very-late first‐contact schizophrenia and the risk of dementia—a nationwide register based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(1):61-67.

11. Zakzanis KK, Andrikopoulos J, Young DA, et al. Neuropsychological differentiation of late-onset schizophrenia and dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Appl Neuropsychol. 2003;10(2):105-114.

12. Zakzanis KK, Kielar A, Young DA, et al. Neuropsychological differentiation of late onset schizophrenia and frontotemporal dementia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2001;6(1):63-77.

13. Webster J, Grossberg GT. Late-life onset of psychotic symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6(3):196-202.

14. Brenner R, Campbell K, Konakondla K, et al. Late onset schizoaffective disorder. Consultant. 2014;53(6):487-488.

15. Evans JD, Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, et al. Schizoaffective disorder: a form of schizophrenia or affective disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(12):874-882.

16. Jeste DV, Blazer DG, First M. Aging-related diagnostic variations: need for diagnostic criteria appropriate for elderly psychiatric patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(4):265-271.

1. Bleuler M. Die spätschizophrenen Krankheitsbilder. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 1943;15:259-290.

2. Howard R, Rabins PV, Seeman MV, et al. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. The International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group. Am J Psychiatry. 2000; 157(2):172-178.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Harris MJ, Jeste DV. Late-onset schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14(1):39-55.

5. Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, “just the facts”: what we know in 2008 part 1: overview. Schizophr Res. 2008;100(1):4-19.

6. Rajji TK, Mulsant BH. Nature and course of cognitive function in late-life schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1-3):122-140.

7. Rajji TK, Ismail Z, Mulsant BH. Age at onset and cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(4):286-293.

8. Goldberg TE, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, et al. Course of schizophrenia: neuropsychological evidence for a static encephalopathy. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(4):797-804.

9. Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Koschera A, et al. Long-term outcome of late-onset schizophrenia: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183(3):213-219.

10. Kørner A, Lopez AG, Lauritzen L, et al. Late and very-late first‐contact schizophrenia and the risk of dementia—a nationwide register based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(1):61-67.

11. Zakzanis KK, Andrikopoulos J, Young DA, et al. Neuropsychological differentiation of late-onset schizophrenia and dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Appl Neuropsychol. 2003;10(2):105-114.

12. Zakzanis KK, Kielar A, Young DA, et al. Neuropsychological differentiation of late onset schizophrenia and frontotemporal dementia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2001;6(1):63-77.

13. Webster J, Grossberg GT. Late-life onset of psychotic symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6(3):196-202.

14. Brenner R, Campbell K, Konakondla K, et al. Late onset schizoaffective disorder. Consultant. 2014;53(6):487-488.

15. Evans JD, Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, et al. Schizoaffective disorder: a form of schizophrenia or affective disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(12):874-882.

16. Jeste DV, Blazer DG, First M. Aging-related diagnostic variations: need for diagnostic criteria appropriate for elderly psychiatric patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(4):265-271.

February 2016 Quiz 2

Q2: ANSWER: D

Critique

This is a patient with severe alcoholic hepatitis complicated by sepsis with a Maddrey’s discriminant function greater than 32. Pentoxifylline 400 mg t.i.d. would be the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pentoxifylline is a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor that decreases tumor necrosis factor gene transcription. In one study of severe alcoholic hepatitis, it appeared to reduce both mortality and renal failure. It may have a beneficial effect in preventing HRS. Prednisone would not be optimal in the setting of active infection and sepsis. Anti-TNF treatment has been associated with increased risk of severe infections and this and propylthiouracil have not shown benefit in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. For this patient with severe alcoholic hepatitis, treatment will improve survival and observation would not be adequate.

References

- O’Shea R.S., Dasarathy S., McCullough A.J.. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2010;51:307-28.

- Mathurin P., Mendenhall C.L., et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatol. 2002;36:480-7.

Q2: ANSWER: D

Critique

This is a patient with severe alcoholic hepatitis complicated by sepsis with a Maddrey’s discriminant function greater than 32. Pentoxifylline 400 mg t.i.d. would be the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pentoxifylline is a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor that decreases tumor necrosis factor gene transcription. In one study of severe alcoholic hepatitis, it appeared to reduce both mortality and renal failure. It may have a beneficial effect in preventing HRS. Prednisone would not be optimal in the setting of active infection and sepsis. Anti-TNF treatment has been associated with increased risk of severe infections and this and propylthiouracil have not shown benefit in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. For this patient with severe alcoholic hepatitis, treatment will improve survival and observation would not be adequate.

References

- O’Shea R.S., Dasarathy S., McCullough A.J.. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2010;51:307-28.

- Mathurin P., Mendenhall C.L., et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatol. 2002;36:480-7.

Q2: ANSWER: D

Critique

This is a patient with severe alcoholic hepatitis complicated by sepsis with a Maddrey’s discriminant function greater than 32. Pentoxifylline 400 mg t.i.d. would be the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pentoxifylline is a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor that decreases tumor necrosis factor gene transcription. In one study of severe alcoholic hepatitis, it appeared to reduce both mortality and renal failure. It may have a beneficial effect in preventing HRS. Prednisone would not be optimal in the setting of active infection and sepsis. Anti-TNF treatment has been associated with increased risk of severe infections and this and propylthiouracil have not shown benefit in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. For this patient with severe alcoholic hepatitis, treatment will improve survival and observation would not be adequate.

References

- O’Shea R.S., Dasarathy S., McCullough A.J.. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2010;51:307-28.

- Mathurin P., Mendenhall C.L., et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatol. 2002;36:480-7.

Chronic pain and psychiatric illness: Managing comorbid conditions

Pain is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical care, with an associated estimated annual cost of $600 billion.1 Using a multimodal approach to care—thorough evaluation, cognitive-behavioral and psychophysiological therapy, physical therapy, medications, and other interventions—can help patients effectively manage their condition and achieve healthier outcomes.

Evaluating a patient with pain

When developing a safe, comprehensive, and effective treatment plan for patients with chronic pain, first perform a thorough history and physical exam using the following elements:

Pain history. The PQRST mnemonic (Table 1) can help you obtain critical information and assist in determining the appropriate diagnosis and cause of the patient’s pain complaints.

Psychiatric history. Document the mental health history of the patient and first-degree relatives.

Medical history. Knowing the medical history could reveal comorbidities contributing to a patient’s pain complaint.

Treatment history. Listing past and current treatments for pain, including effectiveness, helps the clinician understand if an existing treatment plan should be modified.

Functional status. Document current level of daily activity, how life activities are affected by pain; strategies used to help cope with pain; level of physical and emotional support provided in home, work, and school environments; and active stressors (eg, financial, interpersonal).

Psychosocial history. Document historical information related to coping skills, trauma history, family of origin, abuse, interpersonal relationships, social support, and academic and vocational functioning.

Substance use or abuse. Assess for use of controlled substances (ie, early refills; lost medications; obtaining medications from multiple prescribers, friends, families, or strangers; use of prescribed and non-prescribed medications for non-medical and medical purposes), nicotine, alcohol, illicit substances, and caffeine. A thorough inventory can help to identify substances a patient is using that could affect daily functioning and pain level.

Behavioral observations. Assessing mental status (eg, insight, pain behavior, cooperation) can be useful. Paying attention to pain behaviors, such as complaints of pain, decreased activity, increased medication intake, or altered facial expressions or body posture, can help the clinician gain insight to the extent that pain affects the patient’s quality of life.

The information gathered in the patient evaluation can be used to design a multimodal treatment plan to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Assessing psychiatric illness

Current approaches to pain evaluation and treatment recommend use of a biopsychosocial orientation because psychological, behavioral, and social factors can influence the experience and impact of pain, regardless of the primary cause.2 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan should consider the broader context in which a patient’s pain occurs.

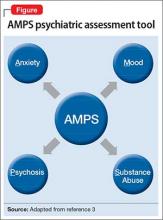

Regarding psychiatric illness, past and current symptoms, treatment history, and risk assessment should all be included. Using the “AMPS approach” (Figure)3—assessing Anxiety, Mood (depression and mania), Psychotic symptoms (paranoid ideation and hallucinations), and Substance use—helps screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions in patients with chronic pain.

Sleep assessment

Chronic pain patients often experience significant sleep disturbance that could be caused by physiological aspects of the pain condition, environmental factors (eg, uncomfortable bedding), a comorbid sleep disorder (eg, sleep apnea), a psychiatric disorder, or a combination of the above.

Obstructive and central sleep apnea are characterized by nighttime hypoxia, which leads to frequent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and often manifests as daytime fatigue, irritability, depression, drowsiness, headaches, and increased pain sensitivity. Changes in sleep arousal can lead to neuropsychological changes during the day, such as decreased attention, memory problems, impaired executive functioning, and reduced impulse control.

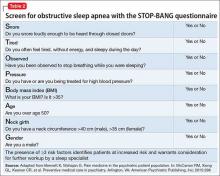

Screen patients for central and obstructive sleep apnea before prescribing opioids or benzodiazepines for pain because these medications can cause or exacerbate underlying sleep apnea. Although many screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, assess daytime somnolence,4 the STOP-BANG questionnaire is a quick, validated, and efficient screening tool that often is used to assess sleep apnea risk5,6 (Table 2). The presence of ≥3 risk factors identifies patients at increased risk and warrants consideration for further workup by a sleep specialist.7,8

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain

Non-opioid medications. Pain can be broadly categorized as neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain can be described by patients as numbness, burning, electric-like, and tingling, and is associated with nerve damage. Nociceptive pain commonly is described as similar to a toothache with descriptors such as stabbing, sharp, or a dull aching sensation; it is often, but not always, associated with acute injury or ongoing trauma to tissue. Drug treatment is most successful when the appropriate class of medication is matched to the specific type of pain.

Nociceptive pain often is successfully treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen. Non-selective COX inhibitors (eg, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac) and COX-2 selective inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) have been associated with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal disease; acetaminophen is associated with liver dysfunction.9-11 However, the absolute risk for complications in healthy patients is low.12 To minimize risk, use these agents for the shortest duration and at the lowest effective dosage possible.