User login

Clarion Call

A specialty without a disease: It was a major hangup for the field of hospital medicine in the early days. We’d hurdled many of the traditional barriers to specialty status—research fellowships, textbooks, an active society, a growing body of research, and thousands of practitioners focusing their practice on the hospital setting. However, despite several examples of site-defined specialties like emergency and critical-care medicine, cynics clung to the time-honored need for a specialty to own an organ, or at least a disease.

Early SHM efforts made a strong push to make VTE our disease—both its treatment and, more importantly, its prevention. It was a laudable effort, one that has saved many thousands of lives and limbs. It made sense for hospitalists to tackle VTE; it’s an incapacitating disease that affects many, is largely preventable, and had no strong inpatient advocate. While hematologists were the obvious “owner” of this disease, they were neither available nor able to redesign the inpatient systems of care necessary to thwart this illness. Hospitalists, invested in this issue by consequence of direct care of many at-risk patients and through commitment to improving hospital systems, came to own VTE prevention.

The Next Frontier: Stroke

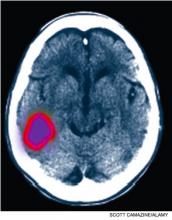

It is time hospitalists apply this experience to the management of an even more incapacitating, largely preventable disease looking for an inpatient steward: stroke. A stroke occurs in the U.S. every 40 seconds, with disabling sequelae that often are avoidable with rapid detection and treatment. This is especially true when we are given the clarion call of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). The problem is that most American hospitals are not kingpins of efficiency—the key ingredient of the processes necessary to improve stroke outcomes. Furthermore, while our neurologic colleagues are the obvious group to lead the deployment of stroke QI programs, there just aren’t enough of them to do so.

Hospitalists provide a significant amount of neurologic care. One study notes that TIA and stroke were among the most commonly cared-for diseases by hospitalists.1 This places us in a prime position to take the lead and own this disease in collaboration with our neurology colleagues. Just as with reliable VTE prevention, the key to effective stroke care requires effective systems engineering in conjunction with disease-specific expertise.

Rapid Care for Acute Medical Crisis

EDs are equipped with stroke pathways to efficiently evaluate, triage, scan, and intervene for patients who present with stroke symptoms. While most hospitals have a long way to go to perfect these systems, some hospitals—mostly in large, urban centers—have achieved the appropriate level of ED efficiency. These hospitals are recognized by The Joint Commission accreditation as stroke centers. As a result, patients who present to these hospitals with stroke symptoms often receive thrombolytics—a disease- and life-altering therapy—within the appropriate, but very limited, time window for benefit.

But what happens if that same patient develops those same signs and symptoms in the hospital? Will they get the same level of efficient evaluation, triage, scanning, and intervention that occurs in the ED? This is more than an academic question. Fifteen percent of all strokes are heralded by transient neurologic deficits, so many of the estimated 300,000 annual TIA patients are admitted to the hospital. What’s the reason for the admission? To facilitate the diagnostic workup, monitor for stroke symptoms and apply timely interventions should this occur.

But are we equipped to provide this kind of timely care in the hospital?

Case Study

Let’s take a 70-year-old diabetic male who presents with 45 minutes of aphasia and right-side arm weakness that resolve prior to presentation to the ED. If the patient is hypertensive on admission, the ABCD tool would suggest that he has a risk of stroke that approximates 20% in 90 days.2 Importantly, nearly half of that risk is in the first 48 hours. In other words, he has about a 10% risk of having a stroke in the next two days. Thus, we rightly admit him for monitoring in order to react quickly to any new signs and symptoms.

The problem is that most hospitals don’t have a system to efficiently manage patients who develop new stroke symptoms in the hospital. Does your hospital have an inpatient stroke pathway? That is, for a patient who has stroke onset while already in the hospital:

- Are the nurses aware of stroke signs and symptoms?

- Do nurses have a phone number to call to initiate an evaluation?

- Is there a team with stroke expertise immediately available to respond to those calls?

- Is there a priority path to get the patient promptly transported to the CT scanner for brain imaging with immediate radiology interpretation?

- How fast can thrombolytics be delivered, and is there an inpatient neurologist available 24/7 to assist?

The goal is 25 minutes from first recognition of symptoms to CT scan, and 60 minutes to complete evaluation and commencement of treatment. What percentage of your inpatient units could meet that goal? Could they do it any day of the week, at any time of the day or night?

ED systems had to be developed and implemented to ensure that appropriate candidates receive thrombolytic therapy in a timely manner. If those systems are not in place outside your hospital’s ED, then inpatient stroke cases are likely to miss the window of opportunity for thrombolytics. Ironically, they might have been better off going home and coming to the ED with any new symptoms. As a hospitalist, that is a sobering thought.

Hospitalist Ownership

It takes more than hospitalists being on-site to improve stroke outcomes. Processes need to be sharpened, roles defined, and outcomes monitored and acted upon to further sharpen the process. All of this plays to the strengths of hospitalists and should be undertaken with the vigor afforded to VTE prevention. This will take recognition that there’s a problem with the system, a dedication of resources, and a commitment to relentlessly work to improve and streamline the processes of stroke care.

In other words, it takes ownership. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group and hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado Denver. Ethan Cumbler, MD, contributed to this article. Dr. Cumbler is assistant professor of medicine at UC Denver and a member of the university’s Hospital Stroke Council.

This column represents the opinions of the author and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

References

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

A specialty without a disease: It was a major hangup for the field of hospital medicine in the early days. We’d hurdled many of the traditional barriers to specialty status—research fellowships, textbooks, an active society, a growing body of research, and thousands of practitioners focusing their practice on the hospital setting. However, despite several examples of site-defined specialties like emergency and critical-care medicine, cynics clung to the time-honored need for a specialty to own an organ, or at least a disease.

Early SHM efforts made a strong push to make VTE our disease—both its treatment and, more importantly, its prevention. It was a laudable effort, one that has saved many thousands of lives and limbs. It made sense for hospitalists to tackle VTE; it’s an incapacitating disease that affects many, is largely preventable, and had no strong inpatient advocate. While hematologists were the obvious “owner” of this disease, they were neither available nor able to redesign the inpatient systems of care necessary to thwart this illness. Hospitalists, invested in this issue by consequence of direct care of many at-risk patients and through commitment to improving hospital systems, came to own VTE prevention.

The Next Frontier: Stroke

It is time hospitalists apply this experience to the management of an even more incapacitating, largely preventable disease looking for an inpatient steward: stroke. A stroke occurs in the U.S. every 40 seconds, with disabling sequelae that often are avoidable with rapid detection and treatment. This is especially true when we are given the clarion call of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). The problem is that most American hospitals are not kingpins of efficiency—the key ingredient of the processes necessary to improve stroke outcomes. Furthermore, while our neurologic colleagues are the obvious group to lead the deployment of stroke QI programs, there just aren’t enough of them to do so.

Hospitalists provide a significant amount of neurologic care. One study notes that TIA and stroke were among the most commonly cared-for diseases by hospitalists.1 This places us in a prime position to take the lead and own this disease in collaboration with our neurology colleagues. Just as with reliable VTE prevention, the key to effective stroke care requires effective systems engineering in conjunction with disease-specific expertise.

Rapid Care for Acute Medical Crisis

EDs are equipped with stroke pathways to efficiently evaluate, triage, scan, and intervene for patients who present with stroke symptoms. While most hospitals have a long way to go to perfect these systems, some hospitals—mostly in large, urban centers—have achieved the appropriate level of ED efficiency. These hospitals are recognized by The Joint Commission accreditation as stroke centers. As a result, patients who present to these hospitals with stroke symptoms often receive thrombolytics—a disease- and life-altering therapy—within the appropriate, but very limited, time window for benefit.

But what happens if that same patient develops those same signs and symptoms in the hospital? Will they get the same level of efficient evaluation, triage, scanning, and intervention that occurs in the ED? This is more than an academic question. Fifteen percent of all strokes are heralded by transient neurologic deficits, so many of the estimated 300,000 annual TIA patients are admitted to the hospital. What’s the reason for the admission? To facilitate the diagnostic workup, monitor for stroke symptoms and apply timely interventions should this occur.

But are we equipped to provide this kind of timely care in the hospital?

Case Study

Let’s take a 70-year-old diabetic male who presents with 45 minutes of aphasia and right-side arm weakness that resolve prior to presentation to the ED. If the patient is hypertensive on admission, the ABCD tool would suggest that he has a risk of stroke that approximates 20% in 90 days.2 Importantly, nearly half of that risk is in the first 48 hours. In other words, he has about a 10% risk of having a stroke in the next two days. Thus, we rightly admit him for monitoring in order to react quickly to any new signs and symptoms.

The problem is that most hospitals don’t have a system to efficiently manage patients who develop new stroke symptoms in the hospital. Does your hospital have an inpatient stroke pathway? That is, for a patient who has stroke onset while already in the hospital:

- Are the nurses aware of stroke signs and symptoms?

- Do nurses have a phone number to call to initiate an evaluation?

- Is there a team with stroke expertise immediately available to respond to those calls?

- Is there a priority path to get the patient promptly transported to the CT scanner for brain imaging with immediate radiology interpretation?

- How fast can thrombolytics be delivered, and is there an inpatient neurologist available 24/7 to assist?

The goal is 25 minutes from first recognition of symptoms to CT scan, and 60 minutes to complete evaluation and commencement of treatment. What percentage of your inpatient units could meet that goal? Could they do it any day of the week, at any time of the day or night?

ED systems had to be developed and implemented to ensure that appropriate candidates receive thrombolytic therapy in a timely manner. If those systems are not in place outside your hospital’s ED, then inpatient stroke cases are likely to miss the window of opportunity for thrombolytics. Ironically, they might have been better off going home and coming to the ED with any new symptoms. As a hospitalist, that is a sobering thought.

Hospitalist Ownership

It takes more than hospitalists being on-site to improve stroke outcomes. Processes need to be sharpened, roles defined, and outcomes monitored and acted upon to further sharpen the process. All of this plays to the strengths of hospitalists and should be undertaken with the vigor afforded to VTE prevention. This will take recognition that there’s a problem with the system, a dedication of resources, and a commitment to relentlessly work to improve and streamline the processes of stroke care.

In other words, it takes ownership. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group and hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado Denver. Ethan Cumbler, MD, contributed to this article. Dr. Cumbler is assistant professor of medicine at UC Denver and a member of the university’s Hospital Stroke Council.

This column represents the opinions of the author and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

References

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

A specialty without a disease: It was a major hangup for the field of hospital medicine in the early days. We’d hurdled many of the traditional barriers to specialty status—research fellowships, textbooks, an active society, a growing body of research, and thousands of practitioners focusing their practice on the hospital setting. However, despite several examples of site-defined specialties like emergency and critical-care medicine, cynics clung to the time-honored need for a specialty to own an organ, or at least a disease.

Early SHM efforts made a strong push to make VTE our disease—both its treatment and, more importantly, its prevention. It was a laudable effort, one that has saved many thousands of lives and limbs. It made sense for hospitalists to tackle VTE; it’s an incapacitating disease that affects many, is largely preventable, and had no strong inpatient advocate. While hematologists were the obvious “owner” of this disease, they were neither available nor able to redesign the inpatient systems of care necessary to thwart this illness. Hospitalists, invested in this issue by consequence of direct care of many at-risk patients and through commitment to improving hospital systems, came to own VTE prevention.

The Next Frontier: Stroke

It is time hospitalists apply this experience to the management of an even more incapacitating, largely preventable disease looking for an inpatient steward: stroke. A stroke occurs in the U.S. every 40 seconds, with disabling sequelae that often are avoidable with rapid detection and treatment. This is especially true when we are given the clarion call of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). The problem is that most American hospitals are not kingpins of efficiency—the key ingredient of the processes necessary to improve stroke outcomes. Furthermore, while our neurologic colleagues are the obvious group to lead the deployment of stroke QI programs, there just aren’t enough of them to do so.

Hospitalists provide a significant amount of neurologic care. One study notes that TIA and stroke were among the most commonly cared-for diseases by hospitalists.1 This places us in a prime position to take the lead and own this disease in collaboration with our neurology colleagues. Just as with reliable VTE prevention, the key to effective stroke care requires effective systems engineering in conjunction with disease-specific expertise.

Rapid Care for Acute Medical Crisis

EDs are equipped with stroke pathways to efficiently evaluate, triage, scan, and intervene for patients who present with stroke symptoms. While most hospitals have a long way to go to perfect these systems, some hospitals—mostly in large, urban centers—have achieved the appropriate level of ED efficiency. These hospitals are recognized by The Joint Commission accreditation as stroke centers. As a result, patients who present to these hospitals with stroke symptoms often receive thrombolytics—a disease- and life-altering therapy—within the appropriate, but very limited, time window for benefit.

But what happens if that same patient develops those same signs and symptoms in the hospital? Will they get the same level of efficient evaluation, triage, scanning, and intervention that occurs in the ED? This is more than an academic question. Fifteen percent of all strokes are heralded by transient neurologic deficits, so many of the estimated 300,000 annual TIA patients are admitted to the hospital. What’s the reason for the admission? To facilitate the diagnostic workup, monitor for stroke symptoms and apply timely interventions should this occur.

But are we equipped to provide this kind of timely care in the hospital?

Case Study

Let’s take a 70-year-old diabetic male who presents with 45 minutes of aphasia and right-side arm weakness that resolve prior to presentation to the ED. If the patient is hypertensive on admission, the ABCD tool would suggest that he has a risk of stroke that approximates 20% in 90 days.2 Importantly, nearly half of that risk is in the first 48 hours. In other words, he has about a 10% risk of having a stroke in the next two days. Thus, we rightly admit him for monitoring in order to react quickly to any new signs and symptoms.

The problem is that most hospitals don’t have a system to efficiently manage patients who develop new stroke symptoms in the hospital. Does your hospital have an inpatient stroke pathway? That is, for a patient who has stroke onset while already in the hospital:

- Are the nurses aware of stroke signs and symptoms?

- Do nurses have a phone number to call to initiate an evaluation?

- Is there a team with stroke expertise immediately available to respond to those calls?

- Is there a priority path to get the patient promptly transported to the CT scanner for brain imaging with immediate radiology interpretation?

- How fast can thrombolytics be delivered, and is there an inpatient neurologist available 24/7 to assist?

The goal is 25 minutes from first recognition of symptoms to CT scan, and 60 minutes to complete evaluation and commencement of treatment. What percentage of your inpatient units could meet that goal? Could they do it any day of the week, at any time of the day or night?

ED systems had to be developed and implemented to ensure that appropriate candidates receive thrombolytic therapy in a timely manner. If those systems are not in place outside your hospital’s ED, then inpatient stroke cases are likely to miss the window of opportunity for thrombolytics. Ironically, they might have been better off going home and coming to the ED with any new symptoms. As a hospitalist, that is a sobering thought.

Hospitalist Ownership

It takes more than hospitalists being on-site to improve stroke outcomes. Processes need to be sharpened, roles defined, and outcomes monitored and acted upon to further sharpen the process. All of this plays to the strengths of hospitalists and should be undertaken with the vigor afforded to VTE prevention. This will take recognition that there’s a problem with the system, a dedication of resources, and a commitment to relentlessly work to improve and streamline the processes of stroke care.

In other words, it takes ownership. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group and hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado Denver. Ethan Cumbler, MD, contributed to this article. Dr. Cumbler is assistant professor of medicine at UC Denver and a member of the university’s Hospital Stroke Council.

This column represents the opinions of the author and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

References

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

Bundling Bedlam

Even if you receive your salary as an employee of your hospital or hospitalist group, you should keep a close eye on discussions taking place in Washington about reshaping the way hospital care is paid for. It seems that every 10 to 20 years, a seismic tremor starts on Capitol Hill and fundamentally shakes up the way healthcare is funded. It starts with Medicare, then quickly is adopted by private insurers; it not only changes the distribution of dollars, but the new incentives also drive the way medicine is practiced.

In the 1960s, change began with President Johnson and the development of Medicare and Medicaid. It was the first time specific populations—seniors and the poor—were “entitled” to healthcare coverage. In essence, Johnson created the largest “insurance company” in the country, and it became the tail that wagged the dog.

In the 1970s, President Nixon pushed through support for HMOs, and capitation and managed care spread well beyond the Kaisers of the world. This system incentivized controlling costs, because the total amount was capped, while maintaining an acceptable level of quality. For the first time, doing more did not generate more money.

In the 1980s, diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) changed Medicare payments to hospitals from cost-plus billings to a bundled fee for an episode of care. This motivated hospitals to work with their physicians—sometimes driven by protocols and case managers—to efficiently manage resources and length of stay (LOS). Between capitation, case rates, and DRGs, hospitals have had to refashion themselves to be leaner and more efficient.

Today, with national thought leaders like John Wennberg and Elliot Fisher at Dartmouth and Brent James at Intermountain revealing the many variations in the way healthcare is practiced—and throwing around statistics like “40% of healthcare is wasteful”—it is no wonder that as President Obama and Congress look to add 47 million uninsured persons to the system and try to reduce variation and increase accountabilities, there is every indication that radical changes will be made to the payment system.

One of these newfangled approaches is the bundling of payment for an episode of care to include both the facility charges (e.g., hospital care) and the professional charges (e.g., physician care). Bundling can be a good thing or a worrisome approach, depending on where you sit in this dialogue and how bundling is actually implemented.

Background on Bundling

The motivation of the government—and, by extension, all insurers—is that efforts to control what they pay per unit for a visit, a procedure, or even an entire hospitalization has not curbed costs or led to a satisfactory level of performance. With respect to hospitalized patients, Obama has stated that he wants to eliminate waste by reducing unnecessary readmissions to the tune of $6.8 billion annually. Furthermore, Medicare officials want to look for strategies that either keep people out of the ED post-discharge or at least eliminate Medicare’s need to pay for this care, which they feel is unnecessary and avoidable.

By bundling payment for a specific admission (e.g., decompensated heart failure or pneumonia) and including the facility and professional-care fees, both during hospitalization and for a period of time (e.g., 30 days post-discharge) and providing incentives for best performance, the insurer (i.e., Medicare) can hand off responsibility to the hospitals and the doctors to figure it all out. There is nothing like the accountability of knowing “this is all you are going to get,” or “if you want more, you have to meet these standards,” to motivate professionals to reshape their system to improve their discharge process, engage the outpatient physicians, and do the job right the first time. This can play to HM’s strengths, and SHM already has started developing and implementing change in the discharge process through Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions, www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).

Potential Problems

One key concern is not knowing who—or what—will control the dollars once Medicare sets the bundled payment. Right now, hospitals receive the DRG payment and physicians bill for their own professional services. In the future, will all the money flow to the hospital? How will these dollars be distributed? Who determines who will be awarded performance bonuses?

In California and other states with significant managed-care populations and large medical groups, there is real-life experience with setting up efficient physician-hospital organizations (PHOs) to solve these issues. Some take the form of independent physician associations (IPAs), which represent the physicians in PHOs. There is no reason PHOs cannot be developed to administrate these bundled funds, and hospitalists, who are seeing an increasing number of hospitalized patients on medicine and surgery, should be key leaders in such PHO arrangements.

But HM is not a monolith in this discussion. The diversity in how HM groups are organized, their relationship with their hospitals, and how hospitalists or their groups receive funding can, and will, influence the group’s perspective on this issue. Hospitalist groups that are independent from their hospitals, or those that rely on referrals from primary-care physicians (PCPs) or the ED, might be justifiably concerned about all of “their” money having to flow through the hospital. Hospitalists who are employed by a hospital might be concerned that they will need to develop new metrics to justify their salaries and bonuses. HM groups that contract with the hospital might be concerned that a change in the flow of funding from Medicare to the hospital might make their contractual arrangements more difficult.

For those who battle with hospital administration over hospital support of their HM group, they might find bundling alleviates the need for the current use of Part A dollars to support hospitalists, because the new bundling of Part A (current payments for hospital facility charges) and Part B (current payment for physicians’ professional services) can allow for a more professional discussion, based on the value hospitalists bring. The need for subsidies or support could diminish or vanish.

Change Is Coming

No matter your perspective or viewpoint, one reality is coming into focus: This president and this Congress will make sweeping changes, and it appears from our conversations with Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), chair of the powerful Senate Finance Committee (see “Medicine’s Change Agent,” May 2009, p. 18), that bundling and value-based purchasing will be part of healthcare reform.

With this in mind, SHM’s Public Policy Committee is actively engaged in trying to shape bundling in a way that fits emerging changes in the care of hospitalized patients. We want a system that works for the way healthcare will be practiced in the future, not a Band-Aid on the system of the past. This is very important stuff. Hospitalists will be affected by reform because so many of our patients are on Medicare and our compensation is generated by patient care in the hospital.

SHM has created an easy-to-use, Web-based system to send a message to members of Congress through a partnership with Capwiz. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/beheard to get started.

While the uncertainty of healthcare reform and, more specifically, payment reform is at times frightening, mainly because it is so sweeping and at this point so undefined, HM has been forged in the cauldron of change and ambiguity. Hospitalists are positioned as well as any health professionals to seize the opportunities that a new system will provide. And SHM will do its part to help shape the new reality and assist our members in creating successful strategies in this new environment. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

Even if you receive your salary as an employee of your hospital or hospitalist group, you should keep a close eye on discussions taking place in Washington about reshaping the way hospital care is paid for. It seems that every 10 to 20 years, a seismic tremor starts on Capitol Hill and fundamentally shakes up the way healthcare is funded. It starts with Medicare, then quickly is adopted by private insurers; it not only changes the distribution of dollars, but the new incentives also drive the way medicine is practiced.

In the 1960s, change began with President Johnson and the development of Medicare and Medicaid. It was the first time specific populations—seniors and the poor—were “entitled” to healthcare coverage. In essence, Johnson created the largest “insurance company” in the country, and it became the tail that wagged the dog.

In the 1970s, President Nixon pushed through support for HMOs, and capitation and managed care spread well beyond the Kaisers of the world. This system incentivized controlling costs, because the total amount was capped, while maintaining an acceptable level of quality. For the first time, doing more did not generate more money.

In the 1980s, diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) changed Medicare payments to hospitals from cost-plus billings to a bundled fee for an episode of care. This motivated hospitals to work with their physicians—sometimes driven by protocols and case managers—to efficiently manage resources and length of stay (LOS). Between capitation, case rates, and DRGs, hospitals have had to refashion themselves to be leaner and more efficient.

Today, with national thought leaders like John Wennberg and Elliot Fisher at Dartmouth and Brent James at Intermountain revealing the many variations in the way healthcare is practiced—and throwing around statistics like “40% of healthcare is wasteful”—it is no wonder that as President Obama and Congress look to add 47 million uninsured persons to the system and try to reduce variation and increase accountabilities, there is every indication that radical changes will be made to the payment system.

One of these newfangled approaches is the bundling of payment for an episode of care to include both the facility charges (e.g., hospital care) and the professional charges (e.g., physician care). Bundling can be a good thing or a worrisome approach, depending on where you sit in this dialogue and how bundling is actually implemented.

Background on Bundling

The motivation of the government—and, by extension, all insurers—is that efforts to control what they pay per unit for a visit, a procedure, or even an entire hospitalization has not curbed costs or led to a satisfactory level of performance. With respect to hospitalized patients, Obama has stated that he wants to eliminate waste by reducing unnecessary readmissions to the tune of $6.8 billion annually. Furthermore, Medicare officials want to look for strategies that either keep people out of the ED post-discharge or at least eliminate Medicare’s need to pay for this care, which they feel is unnecessary and avoidable.

By bundling payment for a specific admission (e.g., decompensated heart failure or pneumonia) and including the facility and professional-care fees, both during hospitalization and for a period of time (e.g., 30 days post-discharge) and providing incentives for best performance, the insurer (i.e., Medicare) can hand off responsibility to the hospitals and the doctors to figure it all out. There is nothing like the accountability of knowing “this is all you are going to get,” or “if you want more, you have to meet these standards,” to motivate professionals to reshape their system to improve their discharge process, engage the outpatient physicians, and do the job right the first time. This can play to HM’s strengths, and SHM already has started developing and implementing change in the discharge process through Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions, www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).

Potential Problems

One key concern is not knowing who—or what—will control the dollars once Medicare sets the bundled payment. Right now, hospitals receive the DRG payment and physicians bill for their own professional services. In the future, will all the money flow to the hospital? How will these dollars be distributed? Who determines who will be awarded performance bonuses?

In California and other states with significant managed-care populations and large medical groups, there is real-life experience with setting up efficient physician-hospital organizations (PHOs) to solve these issues. Some take the form of independent physician associations (IPAs), which represent the physicians in PHOs. There is no reason PHOs cannot be developed to administrate these bundled funds, and hospitalists, who are seeing an increasing number of hospitalized patients on medicine and surgery, should be key leaders in such PHO arrangements.

But HM is not a monolith in this discussion. The diversity in how HM groups are organized, their relationship with their hospitals, and how hospitalists or their groups receive funding can, and will, influence the group’s perspective on this issue. Hospitalist groups that are independent from their hospitals, or those that rely on referrals from primary-care physicians (PCPs) or the ED, might be justifiably concerned about all of “their” money having to flow through the hospital. Hospitalists who are employed by a hospital might be concerned that they will need to develop new metrics to justify their salaries and bonuses. HM groups that contract with the hospital might be concerned that a change in the flow of funding from Medicare to the hospital might make their contractual arrangements more difficult.

For those who battle with hospital administration over hospital support of their HM group, they might find bundling alleviates the need for the current use of Part A dollars to support hospitalists, because the new bundling of Part A (current payments for hospital facility charges) and Part B (current payment for physicians’ professional services) can allow for a more professional discussion, based on the value hospitalists bring. The need for subsidies or support could diminish or vanish.

Change Is Coming

No matter your perspective or viewpoint, one reality is coming into focus: This president and this Congress will make sweeping changes, and it appears from our conversations with Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), chair of the powerful Senate Finance Committee (see “Medicine’s Change Agent,” May 2009, p. 18), that bundling and value-based purchasing will be part of healthcare reform.

With this in mind, SHM’s Public Policy Committee is actively engaged in trying to shape bundling in a way that fits emerging changes in the care of hospitalized patients. We want a system that works for the way healthcare will be practiced in the future, not a Band-Aid on the system of the past. This is very important stuff. Hospitalists will be affected by reform because so many of our patients are on Medicare and our compensation is generated by patient care in the hospital.

SHM has created an easy-to-use, Web-based system to send a message to members of Congress through a partnership with Capwiz. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/beheard to get started.

While the uncertainty of healthcare reform and, more specifically, payment reform is at times frightening, mainly because it is so sweeping and at this point so undefined, HM has been forged in the cauldron of change and ambiguity. Hospitalists are positioned as well as any health professionals to seize the opportunities that a new system will provide. And SHM will do its part to help shape the new reality and assist our members in creating successful strategies in this new environment. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

Even if you receive your salary as an employee of your hospital or hospitalist group, you should keep a close eye on discussions taking place in Washington about reshaping the way hospital care is paid for. It seems that every 10 to 20 years, a seismic tremor starts on Capitol Hill and fundamentally shakes up the way healthcare is funded. It starts with Medicare, then quickly is adopted by private insurers; it not only changes the distribution of dollars, but the new incentives also drive the way medicine is practiced.

In the 1960s, change began with President Johnson and the development of Medicare and Medicaid. It was the first time specific populations—seniors and the poor—were “entitled” to healthcare coverage. In essence, Johnson created the largest “insurance company” in the country, and it became the tail that wagged the dog.

In the 1970s, President Nixon pushed through support for HMOs, and capitation and managed care spread well beyond the Kaisers of the world. This system incentivized controlling costs, because the total amount was capped, while maintaining an acceptable level of quality. For the first time, doing more did not generate more money.

In the 1980s, diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) changed Medicare payments to hospitals from cost-plus billings to a bundled fee for an episode of care. This motivated hospitals to work with their physicians—sometimes driven by protocols and case managers—to efficiently manage resources and length of stay (LOS). Between capitation, case rates, and DRGs, hospitals have had to refashion themselves to be leaner and more efficient.

Today, with national thought leaders like John Wennberg and Elliot Fisher at Dartmouth and Brent James at Intermountain revealing the many variations in the way healthcare is practiced—and throwing around statistics like “40% of healthcare is wasteful”—it is no wonder that as President Obama and Congress look to add 47 million uninsured persons to the system and try to reduce variation and increase accountabilities, there is every indication that radical changes will be made to the payment system.

One of these newfangled approaches is the bundling of payment for an episode of care to include both the facility charges (e.g., hospital care) and the professional charges (e.g., physician care). Bundling can be a good thing or a worrisome approach, depending on where you sit in this dialogue and how bundling is actually implemented.

Background on Bundling

The motivation of the government—and, by extension, all insurers—is that efforts to control what they pay per unit for a visit, a procedure, or even an entire hospitalization has not curbed costs or led to a satisfactory level of performance. With respect to hospitalized patients, Obama has stated that he wants to eliminate waste by reducing unnecessary readmissions to the tune of $6.8 billion annually. Furthermore, Medicare officials want to look for strategies that either keep people out of the ED post-discharge or at least eliminate Medicare’s need to pay for this care, which they feel is unnecessary and avoidable.

By bundling payment for a specific admission (e.g., decompensated heart failure or pneumonia) and including the facility and professional-care fees, both during hospitalization and for a period of time (e.g., 30 days post-discharge) and providing incentives for best performance, the insurer (i.e., Medicare) can hand off responsibility to the hospitals and the doctors to figure it all out. There is nothing like the accountability of knowing “this is all you are going to get,” or “if you want more, you have to meet these standards,” to motivate professionals to reshape their system to improve their discharge process, engage the outpatient physicians, and do the job right the first time. This can play to HM’s strengths, and SHM already has started developing and implementing change in the discharge process through Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions, www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).

Potential Problems

One key concern is not knowing who—or what—will control the dollars once Medicare sets the bundled payment. Right now, hospitals receive the DRG payment and physicians bill for their own professional services. In the future, will all the money flow to the hospital? How will these dollars be distributed? Who determines who will be awarded performance bonuses?

In California and other states with significant managed-care populations and large medical groups, there is real-life experience with setting up efficient physician-hospital organizations (PHOs) to solve these issues. Some take the form of independent physician associations (IPAs), which represent the physicians in PHOs. There is no reason PHOs cannot be developed to administrate these bundled funds, and hospitalists, who are seeing an increasing number of hospitalized patients on medicine and surgery, should be key leaders in such PHO arrangements.

But HM is not a monolith in this discussion. The diversity in how HM groups are organized, their relationship with their hospitals, and how hospitalists or their groups receive funding can, and will, influence the group’s perspective on this issue. Hospitalist groups that are independent from their hospitals, or those that rely on referrals from primary-care physicians (PCPs) or the ED, might be justifiably concerned about all of “their” money having to flow through the hospital. Hospitalists who are employed by a hospital might be concerned that they will need to develop new metrics to justify their salaries and bonuses. HM groups that contract with the hospital might be concerned that a change in the flow of funding from Medicare to the hospital might make their contractual arrangements more difficult.

For those who battle with hospital administration over hospital support of their HM group, they might find bundling alleviates the need for the current use of Part A dollars to support hospitalists, because the new bundling of Part A (current payments for hospital facility charges) and Part B (current payment for physicians’ professional services) can allow for a more professional discussion, based on the value hospitalists bring. The need for subsidies or support could diminish or vanish.

Change Is Coming

No matter your perspective or viewpoint, one reality is coming into focus: This president and this Congress will make sweeping changes, and it appears from our conversations with Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), chair of the powerful Senate Finance Committee (see “Medicine’s Change Agent,” May 2009, p. 18), that bundling and value-based purchasing will be part of healthcare reform.

With this in mind, SHM’s Public Policy Committee is actively engaged in trying to shape bundling in a way that fits emerging changes in the care of hospitalized patients. We want a system that works for the way healthcare will be practiced in the future, not a Band-Aid on the system of the past. This is very important stuff. Hospitalists will be affected by reform because so many of our patients are on Medicare and our compensation is generated by patient care in the hospital.

SHM has created an easy-to-use, Web-based system to send a message to members of Congress through a partnership with Capwiz. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/beheard to get started.

While the uncertainty of healthcare reform and, more specifically, payment reform is at times frightening, mainly because it is so sweeping and at this point so undefined, HM has been forged in the cauldron of change and ambiguity. Hospitalists are positioned as well as any health professionals to seize the opportunities that a new system will provide. And SHM will do its part to help shape the new reality and assist our members in creating successful strategies in this new environment. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

Grassroots Mentorship

Indu Michael remembers the one-page medical field survey she filled out around this time last year. A pre-med student at the University of California at Los Angeles, she provided the correct job descriptions for surgeons, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, psychiatrists, and internal medicine physicians. Only one medical specialty stumped her.

“I had no idea what a hospitalist did,” says Michael, 21, a senior.

The anonymous survey was part of the application and interview process for the Undergraduate Preceptorship in Internal Medicine (UPIM), a program that was launched last summer at UCLA Medical Center. By the time Michael finished the three-week program in early September, she had a complete understanding of what hospitalists do. She also says she’s leaning toward an internal medicine (IM) career—and might become a hospitalist.

“I’m seriously thinking [Hem-Onc] may not be the direction I want to take,” Michael says. “I realized oncologists are mainly consultative doctors and it’s really the general medicine team that does the medicine.”

Those kind of comments are music to Nasim Afsar-manesh’s ear. Dr. Afsar-manesh, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at UCLA, developed the UPIM program from scratch as a way to expose pre-med undergrads to internal medicine. The ultimate goal, of course, is steering them toward an internist career. She is well aware of medical students’ declining interest in IM, and she believes outreach to undergrads and first-year medical students will help reverse the trend.

“Undergraduates are like sponges,” Dr. Afsar-manesh says. “They are so genuinely excited about the possibilities of getting to do this stuff. … You can appeal to their idealism.” She created the program because “the general field of medicine has become so complex that students who are thinking about making it a career don’t have a good chance to see what the day-to-day practicing of medicine is like.”

HM Test Drive

Michael was one of seven students in the inaugural UPIM session. The program is open to UCLA undergrads who volunteer at least 80 hours at the medical center and pre-med students at the California Institute of Technology, where Dr. Afsar-manesh received her undergraduate degree. Seventeen students applied for the first session; the seven who were selected were chosen based on their motivation, maturity, and enthusiasm for medicine. The plan is simple: UPIM aims to offer an early spark of excitement that will stay with students and serve as positive reinforcement as they proceed through medical school and confront the challenges of an IM career.

UPIM participants were integrated into teams of attendings, residents, and medical school students, and they spent time on hospital units and subspecialty consult services. The undergrads observed residents in their patient evaluations, daily rounds, and discussions with patient families. They witnessed a number of procedures, including central-line placement and bone-marrow biopsies. Although the attendings and residents weren’t required to teach the undergrads, many volunteered a significant amount of their time, Dr. Afsar-manesh says. Some of the students spent night shifts at the hospital.

“The students felt they had participated in something special. They felt the experience had overshadowed anything they had previously done,” says Dr. Afsar-manesh, a member of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee. “I think it’s a program that can really quickly grow.”

Every Friday, undergrads participated in a teaching session, during which they had to present a medically, socially, or ethically challenging case from the previous week. They received lectures on common HM topics, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The sessions featured guest speakers who touched on career options in IM and HM, research careers, tips for getting into medical school, and international health issues.

“I loved the patient interaction, as well as discussing a case with fellow students. I didn’t even mind the long hours,” says Stacey Yudin, 23, a senior pre-med student at UCLA. “While on rounds, medical students and doctors took the time to explain concepts while we were scurrying from patient to patient. The program gave me the opportunity to test-drive my dream. We always test-drive a car before we hand over thousands of dollars for it. Shouldn’t future medical students be able to at least safely experience the practice of medicine?”

Round Two: Upgrade

This summer, Dr. Afsar-manesh is improving the student presentation and guest speaker component of the Friday sessions. She will add QI and patient-safety sessions. But the biggest change to the program is expansion, as she and fellow UCLA hospitalist Ed Ha, MD, will offer a summer session for medical students between their first and second years.

Dr. Afsar-manesh also is busy reaching out to other academic IM and HM programs interested in establishing a preceptorship program. So far, she’s made headway with 10 institutions, including Northwestern University, Stanford University, the University of Michigan Health System, and a handful of the campuses within the University of California system. She’s invited the institutions to participate in a research collaborative to combine their data on program results. “We ultimately need to see how many participants will go into IM and compare that to the national numbers. That will take years,” she says.

Uphill Battle

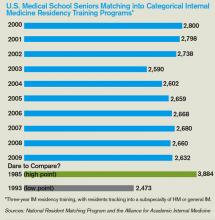

Mark Schwartz, MD, an associate professor in the division of general IM at New York University’s School of Medicine, believes UPIM and programs like it will help—even if only marginally—address the declining interest in IM careers among medical students.

“It will take more than tinkering around in the educational environment,” says Dr. Schwartz, who believes workforce planning, changes in reimbursement, and redesigning medical practices are essential to recruiting medical students to internal medicine (see “A Good Start, But Not Enough”).

Nevertheless, SHM is ready to support a combined IM/HM preceptorship program that targets medical school students in their first and second years, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM. The society already has assigned staff to manage the project and named Dr. Afsar-manesh as the lead physician. The plan is to track preceptorship participants as they make their way through medical school and residency, and see if the program changes their attitudes toward IM careers.

Even though the number of medical students who aspire to hospitalist careers continues to increase every year, SHM believes it must move to counteract the lackluster IM numbers, because that is where most medical students are introduced to HM, Dr. Wellikson says. “The problem of people not picking internal medicine could affect hospital medicine down the road,” he says. “We can’t sit passively by and see who picks to be a hospitalist. We believe we need to be active.”

One of the last things Dr. Afsar-manesh did at the conclusion of the inaugural UPIM program was collect the students’ e-mail addresses and phone numbers so she can stay in touch and track their career paths. The UPIM survey results give her hope: After UPIM, 100% of the students were “extremely confident” in their decision to pursue medicine; 57% indicated they were “very likely” to consider IM as a specialty; and 47% were “very likely” to think about HM.

“This program is a great way to encourage students to enter into internal medicine,” Yudin says. “I am sure that all my subsequent experiences working in a hospital will be measured against my first experience rounding with the IM department.” It seems as though the student took the words right out of the doctor’s mouth. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Reference

- Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154-1164.

Indu Michael remembers the one-page medical field survey she filled out around this time last year. A pre-med student at the University of California at Los Angeles, she provided the correct job descriptions for surgeons, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, psychiatrists, and internal medicine physicians. Only one medical specialty stumped her.

“I had no idea what a hospitalist did,” says Michael, 21, a senior.

The anonymous survey was part of the application and interview process for the Undergraduate Preceptorship in Internal Medicine (UPIM), a program that was launched last summer at UCLA Medical Center. By the time Michael finished the three-week program in early September, she had a complete understanding of what hospitalists do. She also says she’s leaning toward an internal medicine (IM) career—and might become a hospitalist.

“I’m seriously thinking [Hem-Onc] may not be the direction I want to take,” Michael says. “I realized oncologists are mainly consultative doctors and it’s really the general medicine team that does the medicine.”

Those kind of comments are music to Nasim Afsar-manesh’s ear. Dr. Afsar-manesh, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at UCLA, developed the UPIM program from scratch as a way to expose pre-med undergrads to internal medicine. The ultimate goal, of course, is steering them toward an internist career. She is well aware of medical students’ declining interest in IM, and she believes outreach to undergrads and first-year medical students will help reverse the trend.

“Undergraduates are like sponges,” Dr. Afsar-manesh says. “They are so genuinely excited about the possibilities of getting to do this stuff. … You can appeal to their idealism.” She created the program because “the general field of medicine has become so complex that students who are thinking about making it a career don’t have a good chance to see what the day-to-day practicing of medicine is like.”

HM Test Drive

Michael was one of seven students in the inaugural UPIM session. The program is open to UCLA undergrads who volunteer at least 80 hours at the medical center and pre-med students at the California Institute of Technology, where Dr. Afsar-manesh received her undergraduate degree. Seventeen students applied for the first session; the seven who were selected were chosen based on their motivation, maturity, and enthusiasm for medicine. The plan is simple: UPIM aims to offer an early spark of excitement that will stay with students and serve as positive reinforcement as they proceed through medical school and confront the challenges of an IM career.

UPIM participants were integrated into teams of attendings, residents, and medical school students, and they spent time on hospital units and subspecialty consult services. The undergrads observed residents in their patient evaluations, daily rounds, and discussions with patient families. They witnessed a number of procedures, including central-line placement and bone-marrow biopsies. Although the attendings and residents weren’t required to teach the undergrads, many volunteered a significant amount of their time, Dr. Afsar-manesh says. Some of the students spent night shifts at the hospital.

“The students felt they had participated in something special. They felt the experience had overshadowed anything they had previously done,” says Dr. Afsar-manesh, a member of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee. “I think it’s a program that can really quickly grow.”

Every Friday, undergrads participated in a teaching session, during which they had to present a medically, socially, or ethically challenging case from the previous week. They received lectures on common HM topics, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The sessions featured guest speakers who touched on career options in IM and HM, research careers, tips for getting into medical school, and international health issues.

“I loved the patient interaction, as well as discussing a case with fellow students. I didn’t even mind the long hours,” says Stacey Yudin, 23, a senior pre-med student at UCLA. “While on rounds, medical students and doctors took the time to explain concepts while we were scurrying from patient to patient. The program gave me the opportunity to test-drive my dream. We always test-drive a car before we hand over thousands of dollars for it. Shouldn’t future medical students be able to at least safely experience the practice of medicine?”

Round Two: Upgrade

This summer, Dr. Afsar-manesh is improving the student presentation and guest speaker component of the Friday sessions. She will add QI and patient-safety sessions. But the biggest change to the program is expansion, as she and fellow UCLA hospitalist Ed Ha, MD, will offer a summer session for medical students between their first and second years.

Dr. Afsar-manesh also is busy reaching out to other academic IM and HM programs interested in establishing a preceptorship program. So far, she’s made headway with 10 institutions, including Northwestern University, Stanford University, the University of Michigan Health System, and a handful of the campuses within the University of California system. She’s invited the institutions to participate in a research collaborative to combine their data on program results. “We ultimately need to see how many participants will go into IM and compare that to the national numbers. That will take years,” she says.

Uphill Battle

Mark Schwartz, MD, an associate professor in the division of general IM at New York University’s School of Medicine, believes UPIM and programs like it will help—even if only marginally—address the declining interest in IM careers among medical students.

“It will take more than tinkering around in the educational environment,” says Dr. Schwartz, who believes workforce planning, changes in reimbursement, and redesigning medical practices are essential to recruiting medical students to internal medicine (see “A Good Start, But Not Enough”).

Nevertheless, SHM is ready to support a combined IM/HM preceptorship program that targets medical school students in their first and second years, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM. The society already has assigned staff to manage the project and named Dr. Afsar-manesh as the lead physician. The plan is to track preceptorship participants as they make their way through medical school and residency, and see if the program changes their attitudes toward IM careers.

Even though the number of medical students who aspire to hospitalist careers continues to increase every year, SHM believes it must move to counteract the lackluster IM numbers, because that is where most medical students are introduced to HM, Dr. Wellikson says. “The problem of people not picking internal medicine could affect hospital medicine down the road,” he says. “We can’t sit passively by and see who picks to be a hospitalist. We believe we need to be active.”

One of the last things Dr. Afsar-manesh did at the conclusion of the inaugural UPIM program was collect the students’ e-mail addresses and phone numbers so she can stay in touch and track their career paths. The UPIM survey results give her hope: After UPIM, 100% of the students were “extremely confident” in their decision to pursue medicine; 57% indicated they were “very likely” to consider IM as a specialty; and 47% were “very likely” to think about HM.

“This program is a great way to encourage students to enter into internal medicine,” Yudin says. “I am sure that all my subsequent experiences working in a hospital will be measured against my first experience rounding with the IM department.” It seems as though the student took the words right out of the doctor’s mouth. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Reference

- Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154-1164.

Indu Michael remembers the one-page medical field survey she filled out around this time last year. A pre-med student at the University of California at Los Angeles, she provided the correct job descriptions for surgeons, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, psychiatrists, and internal medicine physicians. Only one medical specialty stumped her.

“I had no idea what a hospitalist did,” says Michael, 21, a senior.

The anonymous survey was part of the application and interview process for the Undergraduate Preceptorship in Internal Medicine (UPIM), a program that was launched last summer at UCLA Medical Center. By the time Michael finished the three-week program in early September, she had a complete understanding of what hospitalists do. She also says she’s leaning toward an internal medicine (IM) career—and might become a hospitalist.

“I’m seriously thinking [Hem-Onc] may not be the direction I want to take,” Michael says. “I realized oncologists are mainly consultative doctors and it’s really the general medicine team that does the medicine.”

Those kind of comments are music to Nasim Afsar-manesh’s ear. Dr. Afsar-manesh, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at UCLA, developed the UPIM program from scratch as a way to expose pre-med undergrads to internal medicine. The ultimate goal, of course, is steering them toward an internist career. She is well aware of medical students’ declining interest in IM, and she believes outreach to undergrads and first-year medical students will help reverse the trend.

“Undergraduates are like sponges,” Dr. Afsar-manesh says. “They are so genuinely excited about the possibilities of getting to do this stuff. … You can appeal to their idealism.” She created the program because “the general field of medicine has become so complex that students who are thinking about making it a career don’t have a good chance to see what the day-to-day practicing of medicine is like.”

HM Test Drive

Michael was one of seven students in the inaugural UPIM session. The program is open to UCLA undergrads who volunteer at least 80 hours at the medical center and pre-med students at the California Institute of Technology, where Dr. Afsar-manesh received her undergraduate degree. Seventeen students applied for the first session; the seven who were selected were chosen based on their motivation, maturity, and enthusiasm for medicine. The plan is simple: UPIM aims to offer an early spark of excitement that will stay with students and serve as positive reinforcement as they proceed through medical school and confront the challenges of an IM career.

UPIM participants were integrated into teams of attendings, residents, and medical school students, and they spent time on hospital units and subspecialty consult services. The undergrads observed residents in their patient evaluations, daily rounds, and discussions with patient families. They witnessed a number of procedures, including central-line placement and bone-marrow biopsies. Although the attendings and residents weren’t required to teach the undergrads, many volunteered a significant amount of their time, Dr. Afsar-manesh says. Some of the students spent night shifts at the hospital.

“The students felt they had participated in something special. They felt the experience had overshadowed anything they had previously done,” says Dr. Afsar-manesh, a member of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee. “I think it’s a program that can really quickly grow.”

Every Friday, undergrads participated in a teaching session, during which they had to present a medically, socially, or ethically challenging case from the previous week. They received lectures on common HM topics, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The sessions featured guest speakers who touched on career options in IM and HM, research careers, tips for getting into medical school, and international health issues.

“I loved the patient interaction, as well as discussing a case with fellow students. I didn’t even mind the long hours,” says Stacey Yudin, 23, a senior pre-med student at UCLA. “While on rounds, medical students and doctors took the time to explain concepts while we were scurrying from patient to patient. The program gave me the opportunity to test-drive my dream. We always test-drive a car before we hand over thousands of dollars for it. Shouldn’t future medical students be able to at least safely experience the practice of medicine?”

Round Two: Upgrade

This summer, Dr. Afsar-manesh is improving the student presentation and guest speaker component of the Friday sessions. She will add QI and patient-safety sessions. But the biggest change to the program is expansion, as she and fellow UCLA hospitalist Ed Ha, MD, will offer a summer session for medical students between their first and second years.

Dr. Afsar-manesh also is busy reaching out to other academic IM and HM programs interested in establishing a preceptorship program. So far, she’s made headway with 10 institutions, including Northwestern University, Stanford University, the University of Michigan Health System, and a handful of the campuses within the University of California system. She’s invited the institutions to participate in a research collaborative to combine their data on program results. “We ultimately need to see how many participants will go into IM and compare that to the national numbers. That will take years,” she says.

Uphill Battle

Mark Schwartz, MD, an associate professor in the division of general IM at New York University’s School of Medicine, believes UPIM and programs like it will help—even if only marginally—address the declining interest in IM careers among medical students.

“It will take more than tinkering around in the educational environment,” says Dr. Schwartz, who believes workforce planning, changes in reimbursement, and redesigning medical practices are essential to recruiting medical students to internal medicine (see “A Good Start, But Not Enough”).

Nevertheless, SHM is ready to support a combined IM/HM preceptorship program that targets medical school students in their first and second years, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM. The society already has assigned staff to manage the project and named Dr. Afsar-manesh as the lead physician. The plan is to track preceptorship participants as they make their way through medical school and residency, and see if the program changes their attitudes toward IM careers.

Even though the number of medical students who aspire to hospitalist careers continues to increase every year, SHM believes it must move to counteract the lackluster IM numbers, because that is where most medical students are introduced to HM, Dr. Wellikson says. “The problem of people not picking internal medicine could affect hospital medicine down the road,” he says. “We can’t sit passively by and see who picks to be a hospitalist. We believe we need to be active.”

One of the last things Dr. Afsar-manesh did at the conclusion of the inaugural UPIM program was collect the students’ e-mail addresses and phone numbers so she can stay in touch and track their career paths. The UPIM survey results give her hope: After UPIM, 100% of the students were “extremely confident” in their decision to pursue medicine; 57% indicated they were “very likely” to consider IM as a specialty; and 47% were “very likely” to think about HM.

“This program is a great way to encourage students to enter into internal medicine,” Yudin says. “I am sure that all my subsequent experiences working in a hospital will be measured against my first experience rounding with the IM department.” It seems as though the student took the words right out of the doctor’s mouth. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Reference

- Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154-1164.

Code Correctly

A hospitalist who scrutinizes claims might notice a payment denial related to “unbundling” issues. Line-item rejections might state the service is “mutually exclusive,” “incidental to another procedure,” or “payment was received as part of another service/procedure.” Unbundling refers to the practice of reporting each component of a service or procedure instead of reporting the single, comprehensive code. Two types of practices lead to unbundling: unintentional reporting resulting from a basic misunderstanding of correct coding, and intentional reporting to improperly maximize payment of otherwise bundled Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes.1

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) for implementation and application to physician claims (e.g., Medicare Part B) with dates of service on or after Jan. 1, 1996. The rationale for these edits is a culmination of:

- Coding standards identified in the American Medical Association’s (AMA) CPT manual;

- National and local coverage determinations developed by CMS and local Medicare contractors;

- Coding standards set forth by national medical organizations and specialty societies;

- Appropriate standards of medical and surgical care; and

- Current coding practices identified through claim analysis, pre- and post-payment documentation reviews, and other forms of payor-initiated audit.

The initial NCCI goal was to promote correct coding methodologies and to control improper coding, which led to inappropriate payment in Part B claims.2 It later expanded to include corresponding NCCI edits in the outpatient code editor (OCE) for both outpatient hospital providers and therapy providers. Therapy providers encompass skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facilities (CORFs), outpatient physical therapy (OPTs) and speech-language pathology providers, and home health agencies (HHAs).

Fact-Check

The NCCI recognizes two edit types: Column One/Column Two Correct Coding edits and Mutually Exclusive edits. Each of these edit categories lists code pairs that should not be reported together on the same date by either a single physician or physicians of the same specialty within a provider group.

When applying Column One/Column Two editing logic to physician claims, the Column One code represents the more comprehensive code of the pair being reported. The Column Two code (the component service that is bundled into the comprehensive service) will be denied. This is not to say a code that appears in Column Two of the NCCI cannot be paid when reported by itself on any given date. The denial occurs only when the component service is reported on the same date as the more comprehensive service.

For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) is considered comprehensive to codes 36000 (introduction of needle or intracatheter, vein) and 36410 (venipuncture, age 3 years or older, necessitating physician’s skill [separate procedure], for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). These code combinations should not be reported together on the same date when performed as part of the same procedure by the same physician or physicians of the same practice group. If this occurs, the payor will reimburse the initial service and deny the subsequent service. As a result, the first code received by the payor, on the same or separate claims, is reimbursed, even if that code represents the lesser of the two services.

Mutually Exclusive edits occur with less frequency than Column One/Column Two edits. Mutually Exclusive edits prevent reporting of two services or procedures that are highly unlikely to be performed together on the same patient, at the same session or encounter, by the same physician or physicians of the same specialty in a provider group. For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) would not be reported on the same day as 36555 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, younger than 5 years of age).

CMS publishes the National Correct Coding Initiative Coding Policy Manual for Medicare Services (www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd) and encourages local Medicare contractors and fiscal intermediaries to use it as a reference for claims-processing edits. The manual is updated annually, and the NCCI edits are updated quarterly. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- National correct coding initiative edits. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Medicare claims processing manual. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- Beebe M, Dalton J, Espronceda M, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press, 2008;477-481.

- Modifier 59 article. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/Downloads/modifier59.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- French K. Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, IL: American College of Chest Physicians. 2008;283-287.

A hospitalist who scrutinizes claims might notice a payment denial related to “unbundling” issues. Line-item rejections might state the service is “mutually exclusive,” “incidental to another procedure,” or “payment was received as part of another service/procedure.” Unbundling refers to the practice of reporting each component of a service or procedure instead of reporting the single, comprehensive code. Two types of practices lead to unbundling: unintentional reporting resulting from a basic misunderstanding of correct coding, and intentional reporting to improperly maximize payment of otherwise bundled Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes.1

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) for implementation and application to physician claims (e.g., Medicare Part B) with dates of service on or after Jan. 1, 1996. The rationale for these edits is a culmination of:

- Coding standards identified in the American Medical Association’s (AMA) CPT manual;

- National and local coverage determinations developed by CMS and local Medicare contractors;

- Coding standards set forth by national medical organizations and specialty societies;

- Appropriate standards of medical and surgical care; and

- Current coding practices identified through claim analysis, pre- and post-payment documentation reviews, and other forms of payor-initiated audit.

The initial NCCI goal was to promote correct coding methodologies and to control improper coding, which led to inappropriate payment in Part B claims.2 It later expanded to include corresponding NCCI edits in the outpatient code editor (OCE) for both outpatient hospital providers and therapy providers. Therapy providers encompass skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facilities (CORFs), outpatient physical therapy (OPTs) and speech-language pathology providers, and home health agencies (HHAs).

Fact-Check

The NCCI recognizes two edit types: Column One/Column Two Correct Coding edits and Mutually Exclusive edits. Each of these edit categories lists code pairs that should not be reported together on the same date by either a single physician or physicians of the same specialty within a provider group.

When applying Column One/Column Two editing logic to physician claims, the Column One code represents the more comprehensive code of the pair being reported. The Column Two code (the component service that is bundled into the comprehensive service) will be denied. This is not to say a code that appears in Column Two of the NCCI cannot be paid when reported by itself on any given date. The denial occurs only when the component service is reported on the same date as the more comprehensive service.

For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) is considered comprehensive to codes 36000 (introduction of needle or intracatheter, vein) and 36410 (venipuncture, age 3 years or older, necessitating physician’s skill [separate procedure], for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). These code combinations should not be reported together on the same date when performed as part of the same procedure by the same physician or physicians of the same practice group. If this occurs, the payor will reimburse the initial service and deny the subsequent service. As a result, the first code received by the payor, on the same or separate claims, is reimbursed, even if that code represents the lesser of the two services.

Mutually Exclusive edits occur with less frequency than Column One/Column Two edits. Mutually Exclusive edits prevent reporting of two services or procedures that are highly unlikely to be performed together on the same patient, at the same session or encounter, by the same physician or physicians of the same specialty in a provider group. For example, CPT code 36556 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, age 5 years or older) would not be reported on the same day as 36555 (insertion of nontunneled centrally inserted central venous catheter, younger than 5 years of age).