User login

Tension Pneumocephalus as Complication of Hematoma Evacuation

A 78‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital where he presented with declining mental status and a history of falls. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a chronic subdural hematoma with superimposed acute hemorrhage. The subdural hematoma was attributed to a fall at home approximately 5 weeks prior to admission. He was taken to the operating room for urgent craniotomy and hemorrhage evacuation and postoperatively comanaged by neurosurgery, hospitalists, and medicine residents. He tolerated the procedure and was noted to have marked improvement in mental status after the procedure. He was monitored overnight in our intensive care unit without intracranial pressure monitoring.

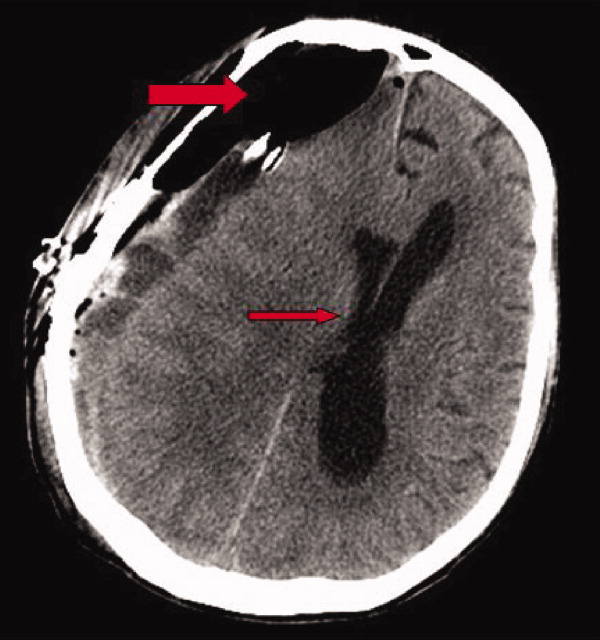

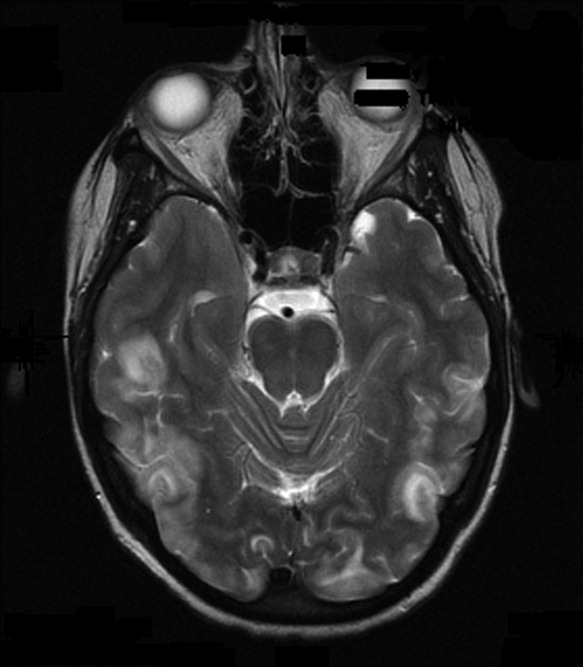

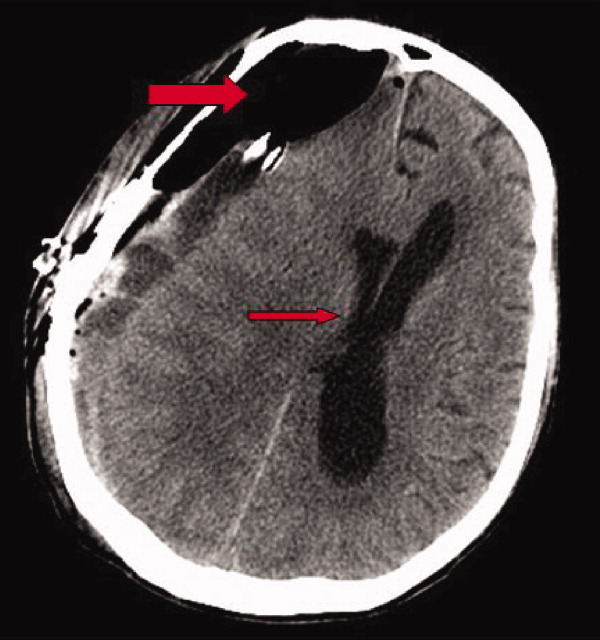

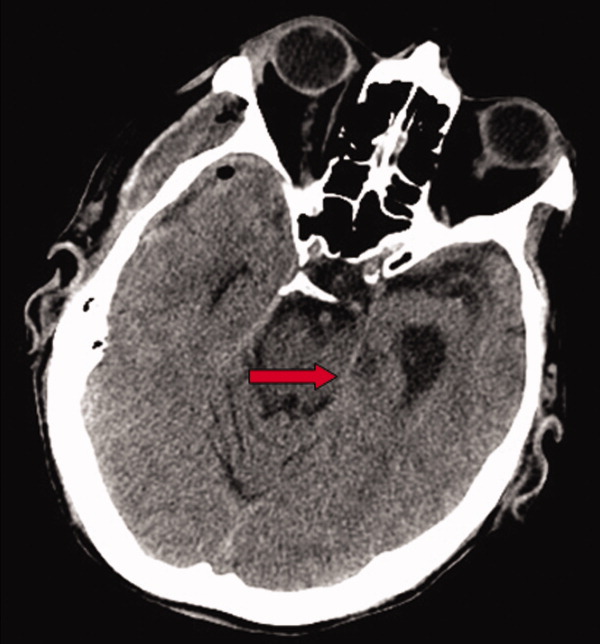

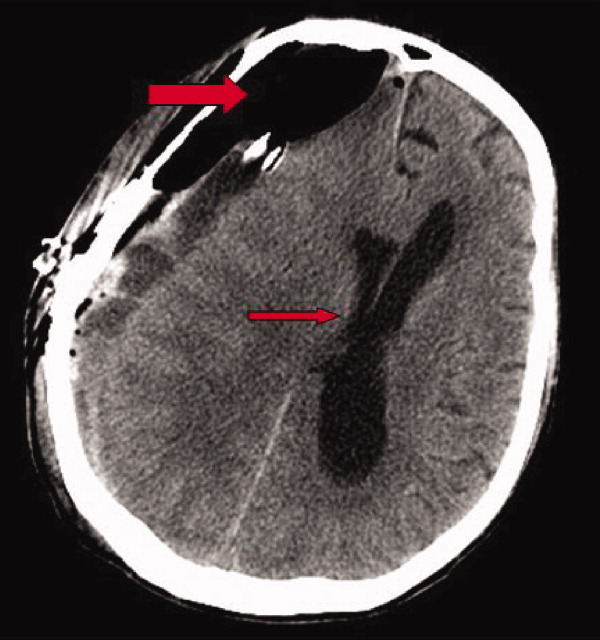

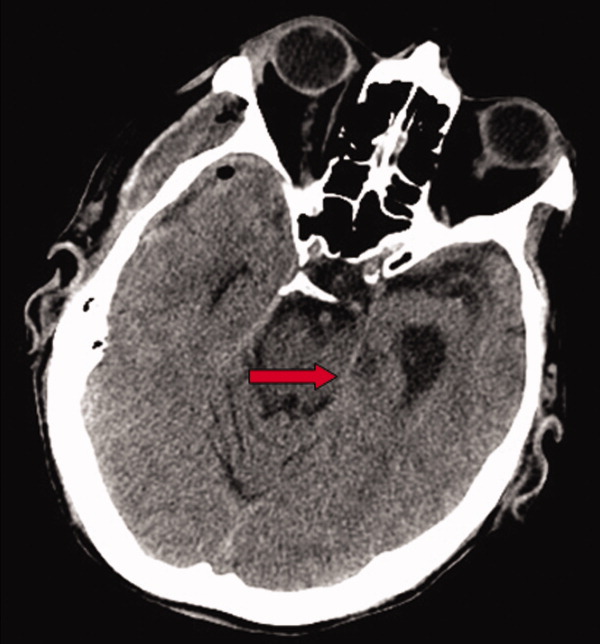

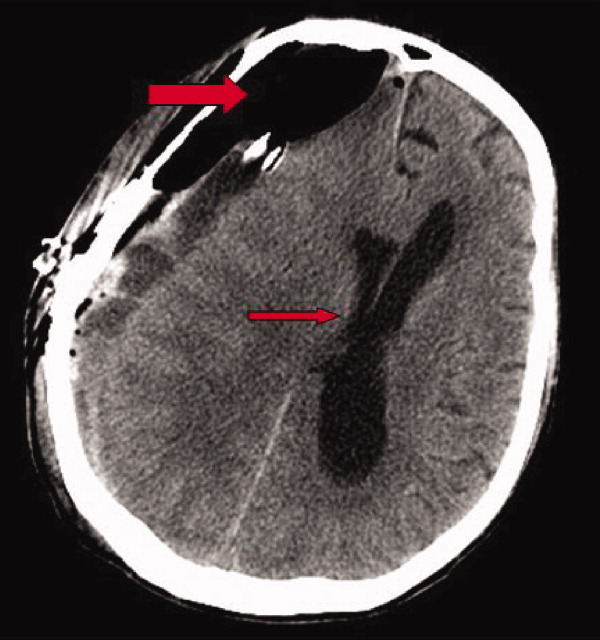

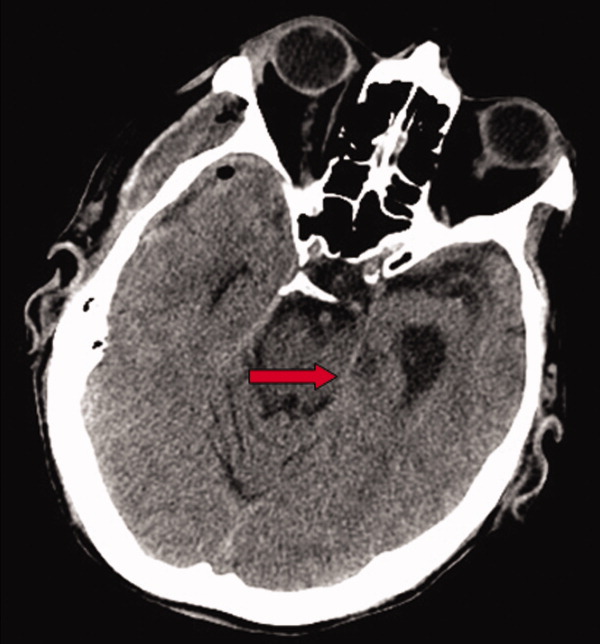

Early on postoperative day 1, he was awake, alert, following commands, and felt to be stable enough to be transferred to our transitional intensive care unit. However, later in the day he became progressively more confused. A follow‐up CT scan of the brain was ordered (Fig. 1) by the medicine team which revealed a large collection of air (wide arrow) and marked midline shift (thin arrow) consistent with tension pneumocephaly and subfalcine herniation (Fig. 2; arrow). Examination revealed that he was grossly obtunded with marked anisocoria, decerebrate posturing, and rigid tone. Neurosurgery was immediately contacted and recommended accessing 2 indwelling catheters left in the cerebrum as part of the normal postoperative course. Approximately 100 mL of serosanguinous fluid and air was aspirated with immediate improvement in his mental status and exam findings. Over the next few days, he remained clinically stable, and repeat CT scan showed slow resolution of the pneumocephalus and a decrease of his mass effect and midline shift. He was ultimately transferred to our skilled nursing facility for physical therapy and has done relatively well.

Pneumocephalus is a relatively common finding in many neurosurgical, intracranial procedures. However, tension pneumocephalus is a rare, life‐threatening form of pneumocephalus in which intracranial air causes mass effect and midline shift. In a review of 295 cases of pneumocephalus, 75% were caused by surgery, mostly intracranial and transsphenoidal, and head trauma. About 9% of cases resulted from infection with gas‐forming bacteria and rare causes include invasion of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma, frequent Valsalva maneuver, and air travel.1 Tension pneumocephalus occurs most commonly after the neurosurgical evacuation of a subdural hematoma. The prevalence of tension pneumocephalus following the evacuation of chronic subdural hematomas has been reported from 2.5% to 16%.2

There are 2 proposed mechanisms for the development of pneumocephalus; 1 proposes that air passes through a dural tear by a ball valve effect in which air can be forced into the intracranial cavity by a rapid increase in intrasinus pressure that occurs during sneezing, coughing, or straining. The air is then trapped intracranially. The second theory proposes that cerebrospinal fluid leakage permits air to enter the intracranial cavity because negative pressure is created as cerebrospinal fluid leaves the space.3 The conversion to tension physiology in either of these theories is less well understood.

- ,,,,.Pneumocephalus secondary to septic thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus: report of a case.J Formos Med Assoc.2001;100(2):142‐144.

- ,,, et al.Subdural tension pneumocephalus following surgery for chronic subdural hematoma.J Neurosurg.1988;68:58‐61.

- ,,,.Nontraumatic tension pneumocephalus—a differential diagnosis of headache in the ED.Am J Emerg Med.2005, Vol.23, pp235‐236.

A 78‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital where he presented with declining mental status and a history of falls. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a chronic subdural hematoma with superimposed acute hemorrhage. The subdural hematoma was attributed to a fall at home approximately 5 weeks prior to admission. He was taken to the operating room for urgent craniotomy and hemorrhage evacuation and postoperatively comanaged by neurosurgery, hospitalists, and medicine residents. He tolerated the procedure and was noted to have marked improvement in mental status after the procedure. He was monitored overnight in our intensive care unit without intracranial pressure monitoring.

Early on postoperative day 1, he was awake, alert, following commands, and felt to be stable enough to be transferred to our transitional intensive care unit. However, later in the day he became progressively more confused. A follow‐up CT scan of the brain was ordered (Fig. 1) by the medicine team which revealed a large collection of air (wide arrow) and marked midline shift (thin arrow) consistent with tension pneumocephaly and subfalcine herniation (Fig. 2; arrow). Examination revealed that he was grossly obtunded with marked anisocoria, decerebrate posturing, and rigid tone. Neurosurgery was immediately contacted and recommended accessing 2 indwelling catheters left in the cerebrum as part of the normal postoperative course. Approximately 100 mL of serosanguinous fluid and air was aspirated with immediate improvement in his mental status and exam findings. Over the next few days, he remained clinically stable, and repeat CT scan showed slow resolution of the pneumocephalus and a decrease of his mass effect and midline shift. He was ultimately transferred to our skilled nursing facility for physical therapy and has done relatively well.

Pneumocephalus is a relatively common finding in many neurosurgical, intracranial procedures. However, tension pneumocephalus is a rare, life‐threatening form of pneumocephalus in which intracranial air causes mass effect and midline shift. In a review of 295 cases of pneumocephalus, 75% were caused by surgery, mostly intracranial and transsphenoidal, and head trauma. About 9% of cases resulted from infection with gas‐forming bacteria and rare causes include invasion of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma, frequent Valsalva maneuver, and air travel.1 Tension pneumocephalus occurs most commonly after the neurosurgical evacuation of a subdural hematoma. The prevalence of tension pneumocephalus following the evacuation of chronic subdural hematomas has been reported from 2.5% to 16%.2

There are 2 proposed mechanisms for the development of pneumocephalus; 1 proposes that air passes through a dural tear by a ball valve effect in which air can be forced into the intracranial cavity by a rapid increase in intrasinus pressure that occurs during sneezing, coughing, or straining. The air is then trapped intracranially. The second theory proposes that cerebrospinal fluid leakage permits air to enter the intracranial cavity because negative pressure is created as cerebrospinal fluid leaves the space.3 The conversion to tension physiology in either of these theories is less well understood.

A 78‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital where he presented with declining mental status and a history of falls. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a chronic subdural hematoma with superimposed acute hemorrhage. The subdural hematoma was attributed to a fall at home approximately 5 weeks prior to admission. He was taken to the operating room for urgent craniotomy and hemorrhage evacuation and postoperatively comanaged by neurosurgery, hospitalists, and medicine residents. He tolerated the procedure and was noted to have marked improvement in mental status after the procedure. He was monitored overnight in our intensive care unit without intracranial pressure monitoring.

Early on postoperative day 1, he was awake, alert, following commands, and felt to be stable enough to be transferred to our transitional intensive care unit. However, later in the day he became progressively more confused. A follow‐up CT scan of the brain was ordered (Fig. 1) by the medicine team which revealed a large collection of air (wide arrow) and marked midline shift (thin arrow) consistent with tension pneumocephaly and subfalcine herniation (Fig. 2; arrow). Examination revealed that he was grossly obtunded with marked anisocoria, decerebrate posturing, and rigid tone. Neurosurgery was immediately contacted and recommended accessing 2 indwelling catheters left in the cerebrum as part of the normal postoperative course. Approximately 100 mL of serosanguinous fluid and air was aspirated with immediate improvement in his mental status and exam findings. Over the next few days, he remained clinically stable, and repeat CT scan showed slow resolution of the pneumocephalus and a decrease of his mass effect and midline shift. He was ultimately transferred to our skilled nursing facility for physical therapy and has done relatively well.

Pneumocephalus is a relatively common finding in many neurosurgical, intracranial procedures. However, tension pneumocephalus is a rare, life‐threatening form of pneumocephalus in which intracranial air causes mass effect and midline shift. In a review of 295 cases of pneumocephalus, 75% were caused by surgery, mostly intracranial and transsphenoidal, and head trauma. About 9% of cases resulted from infection with gas‐forming bacteria and rare causes include invasion of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma, frequent Valsalva maneuver, and air travel.1 Tension pneumocephalus occurs most commonly after the neurosurgical evacuation of a subdural hematoma. The prevalence of tension pneumocephalus following the evacuation of chronic subdural hematomas has been reported from 2.5% to 16%.2

There are 2 proposed mechanisms for the development of pneumocephalus; 1 proposes that air passes through a dural tear by a ball valve effect in which air can be forced into the intracranial cavity by a rapid increase in intrasinus pressure that occurs during sneezing, coughing, or straining. The air is then trapped intracranially. The second theory proposes that cerebrospinal fluid leakage permits air to enter the intracranial cavity because negative pressure is created as cerebrospinal fluid leaves the space.3 The conversion to tension physiology in either of these theories is less well understood.

- ,,,,.Pneumocephalus secondary to septic thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus: report of a case.J Formos Med Assoc.2001;100(2):142‐144.

- ,,, et al.Subdural tension pneumocephalus following surgery for chronic subdural hematoma.J Neurosurg.1988;68:58‐61.

- ,,,.Nontraumatic tension pneumocephalus—a differential diagnosis of headache in the ED.Am J Emerg Med.2005, Vol.23, pp235‐236.

- ,,,,.Pneumocephalus secondary to septic thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus: report of a case.J Formos Med Assoc.2001;100(2):142‐144.

- ,,, et al.Subdural tension pneumocephalus following surgery for chronic subdural hematoma.J Neurosurg.1988;68:58‐61.

- ,,,.Nontraumatic tension pneumocephalus—a differential diagnosis of headache in the ED.Am J Emerg Med.2005, Vol.23, pp235‐236.

Quantification of Bedside Teaching

Bedside teaching, defined as teaching in the presence of a patient, has been an integral, respected part of medical education throughout the history of modern medicine. There is widespread concern among medical educators that bedside teaching is declining, and in particular, physical examination teaching.1‐5 Learning at the bedside accounted for 75% of clinical teaching in the 1960s and only 16% by 1978.2 Current estimates range from 8% to 19%.1

The bedside is the ideal venue for demonstrating, observing, and evaluating medical interviewing skills, physical examination techniques, and interpersonal and communication skills. Role modeling is the primary method by which clinical teachers demonstrate and teach professionalism and humanistic behavior.6 The bedside is also a place to develop clinical reasoning skills, stimulate problem‐based learning,7 and demonstrate teamwork.4 Thus, the decline in bedside teaching is of major concern for more than just the dying of a time‐honored tradition, but for the threat to the development of skills and attitudes essential for the practice of medicine.

With the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists and their presence at most major U.S. teaching hospitals, internal medicine residents and medical students in their medicine clerkships receive much of their inpatient training from attending physicians who are hospitalists.8 Little is known about the teaching practices of hospitalist attending physicians. We investigated the fraction of time hospitalist attending physicians spend at the bedside during attending teaching rounds and the frequency of the demonstration of physical examination skills at 1 academic teaching hospital.

Patients and Methods

The Brigham & Women's Hospitalist Service, a 28‐member academic hospitalist group who serve as both the teaching attendings and patient care attendings on 4 general medicine teams, was studied in a prospective, observational fashion. Internal medicine residents at Brigham & Women's Hospital rotating on the hospitalist service were identified by examining the schedule of inpatient rotations during the 2007‐2008 academic year and were asked to participate in the study via an e‐mail invitation. The Institutional Review Board of Brigham & Women's Hospital approved the study.

Teams were made up of 1 senior resident and 2 interns. Call frequency was every fourth day. Over a period of 23 sequential weekdays, medical residents and interns from each of the 4 hospitalist teams observed and reported the behavior of their attendings on rounds. Their reports captured the fraction of time spent at the bedside during rounds and the frequency of physical examination teaching. Residents and interns were asked to respond to 3 questions in a daily e‐mail. Respondents reported (1) total time spent with their hospitalist attending during attending rounds, (2) time spent inside patient rooms during attending rounds, and (3) whether or not a physical examination finding or skill was demonstrated by their hospitalist attending. When more than 1 team member responded, time reported among team members was averaged and if there was a discrepancy between whether or not a physical examination finding or skill was demonstrated, it was defaulted to the positive response. Hospitalist attendings remained unaware of the daily observations.

Hospitalist attendings were independently invited to complete a baseline needs assessment survey on bedside teaching. Surveys addressed attitudes toward bedside teaching, confidence in ability to lead bedside teaching rounds and teach the physical examination, and adequacy of their own training in these skills. Respondents were asked to comment on obstacles to bedside teaching. Residents were surveyed at the completion of a rotation with a hospitalist attending regarding the value of the time spent at the bedside and their self‐perceived improvement in physical examination skills and bedside teaching skills. The survey solicited the residents' opinion of the most valuable aspect of bedside teaching. The survey questions used a 4‐point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

The fraction of time spent at the bedside during attending hospitalist rounds was calculated from the average time spent in patient rooms and the average time of attending rounds. The frequency of physical examination teaching was expressed as a percent of all teaching encounters. Interrater reliability was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient with the Spearman‐Brown adjustment. Differences between groups were calculated using the Fisher's exact test for counts and the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test for continuous data. Significance was accepted for P < 0.05.

Results

Thirty‐five residents provided observations on 61 of 92 potentially observed attending rounds (66% response rate) over 23 weekdays, including observations of the rounding behavior of 12 different hospitalists. The interrater reliability was 0.91. The average patient census on each team during this time period was 12 (range 6‐19).

Residents reported that their attendings went to the bedside at least once during 37 of these 61 rounds (61%), and provided physical examination teaching during 23 of these 61 (38%) encounters. Hospitalists spent an average of 101 minutes on rounds and an average of 17 minutes (17%) of their time inside patient rooms.

Rounds that included time spent at the bedside were significantly longer on average than rounds that did not include time spent at the bedside (122 vs. 69 minutes, P < 0.001). During rounds that included bedside teaching, teams spent an average of 29 minutes (24% of the total time) in patient rooms, and rounds were significantly more likely to include teaching on physical diagnosis (23/37 rounds vs. 0/24 rounds, P < 0.001). Physical examination teaching did not significantly prolong those rounds that included bedside teaching (124 vs. 119 minutes, P = 0.56), but did significantly increase the amount of time spent at the bedside (32 vs. 22 minutes, P = 0.046).

Eighteen hospitalists (64% response) with a mean of 5.9 years of experience as attending physicians completed a needs‐assessment survey (Table 1). Fourteen of the 18 hospitalists (78%) reported that they prioritize bedside teaching and 16 (89%) requested more emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum. Twelve hospitalists (67%) indicated that they were confident in their ability to lead bedside teaching rounds; 9 (50%) were confident in their ability to teach physical examination. Eleven (61%) of the respondents felt poorly prepared to do bedside teaching after completing their residency, and 12 (67%) felt that they had received inadequate training in how to teach the physical examination. Of the obstacles to bedside teaching, time and inadequate training and skills were the most frequently noted, present in 11 and 6 of the reports, respectively. Lack of confidence and lack of role models were also cited in 4 and 2 of the reports, respectively.

| Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| I make bedside teaching a priority | 0 | 22 | 56 | 22 |

| More emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum is needed | 0 | 11 | 39 | 50 |

| I feel confident in my ability to lead bedside teaching rounds | 11 | 22 | 50 | 17 |

| I was well‐prepared to do bedside teaching after residency training | 22 | 39 | 28 | 11 |

| I feel confident in my ability to teach the physical exam | 11 | 39 | 33 | 17 |

| I have received adequate training in how to teach the physical exam | 17 | 50 | 22 | 11 |

Seventeen medical residents (49% response) completed a survey regarding their general medical service rotation with a hospitalist upon its completion (Table 2). Sixteen of the respondents (94%) agreed that time spent at the bedside during hospitalist attending teaching rounds that specific rotation was valuable, and 15 (82%) of the residents sought more emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum. Four of the respondents (24%) reported that their physical examination skills improved over the rotation, 5 (29%) felt better prepared to teach the physical examination, and 9 (53%) felt better prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds. Only 3 (18%) of the respondents reported that they had received helpful feedback on their physical examination skills from their attending. Responding residents noted physical examination teaching, communication and interpersonal skills, focus on patient‐centered care, and integrating the clinical examination with diagnostic and management decisions as the most valuable aspects of bedside teaching.

| Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Time spent at the bedside during teaching rounds was valuable | 0 | 6 | 65 | 29 |

| More emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum is needed | 0 | 18 | 53 | 29 |

| I feel better prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds | 6 | 41 | 53 | 0 |

| My physical exam skills improved over the rotation | 6 | 71 | 24 | 0 |

| I feel better prepared to teach the physical exam | 6 | 65 | 29 | 0 |

| I received helpful feedback on my physical exam skills | 18 | 65 | 18 | 0 |

Discussion

Bedside teaching is highly valued by clinicians and trainees, though there is little evidence supporting its efficacy. Patients also enjoy and are accepting of bedside presentations7, 9, 10 if certain rules are adhered to (eg, avoid medical jargon) and benefit by having a better understanding of their illness.9 This study supports previous views of medical residents, students,1, 5, 7 and faculty11 of the value and need for greater emphasis on bedside teaching in medical education.

This study of rounding behavior found that hospitalists in this academic center go to the bedside most days, but 39% of attending teaching rounds did not include a bedside encounter. Physical examination teaching is infrequent. Though time spent at the bedside was only a small fraction of total teaching time (17%) in this practice, this fraction is at the high end of previous reports. Teaching rounds that did not include bedside teaching most likely occurred in the confines of a conference room.

Many factors appear to contribute to the paucity of time spent at the bedside: time constraints, shorter hospital stays, greater work demands,11 residency duty‐hour regulations,12 declining bedside teaching skills, unrealistic expectations of the encounter, and erosion of the teaching ethic.3 A decline in clinical examination skills among trainees and attending physicians leads to a growing reliance on data and technology, thereby perpetuating the cycle of declining bedside skills.4

The hospitalists in this study identify time as the most dominant obstacle to bedside teaching. On days when hospitalist attending physicians went to the bedside, rounds were on average 53 minutes longer than on those days when they did not go to the bedside. This time increase varied little whether or not physical examination teaching occurred. The difference in rounding time may be partially explained by the admitting cycle and patient census. Teaching attendings are likely to go to the bedside to see new patients on postcall days when the patient census is also the highest.

Many members of this hospitalist group indicated that they felt inadequately prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds. Of those who responded to the survey, 67% did not feel that they received adequate training in how to teach the physical examination. Consequently, only one‐half of responding hospitalists expressed confidence in their ability to teach the physical examination. Not surprisingly, physical examination skills were a component of a minority of teaching sessions and only one‐quarter of the medical residents perceived that their physical examination skills improved during the rotation with a hospitalist attending. The paucity of feedback to the house‐staff likely contributed to this stagnancy. Residents who become hospitalists ill‐prepared to lead bedside teaching and teach the physical examination will perpetuate the decline in bedside teaching.

Though a substantial portion of the hospitalists in this study lacked confidence, an overwhelming majority of medical residents found their time spent at the bedside with a hospitalist to be valuable. More than one‐half of residents reported that they were better prepared to lead bedside teaching after the rotation. Residents recognize that bedside teaching can include communication and clinical reasoning skills. Hospitalists should be made aware that a broad range of skills and content can be taught at the bedside.

Hospitalists have an increasing influence on the education of medical residents and students and are appropriate targets for faculty development programs aimed at improving bedside teaching. As a newer, growing specialty, hospitalists tend to be younger physicians, and are therefore more reliant on the education attained during residency to support their bedside activities. Many residencies have developed resident as educator programs in an attempt to create a future generation of attendings better able to teach.13

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. The study was limited to a hospitalist group at a single academic medical center and relied on resident recall. Though the response rate to the daily e‐mails was relatively low, the interrater reliability was high, and a broad range of residents and attendings were represented. Residents with greater patient censuses may have been too busy to respond, but it is unclear in which direction this would bias the results.

Conclusions

This study provides additional evidence that bedside and physical examination teaching are in decline. Time is an increasingly precious commodity for hospitalists; though many commentators echo the sentiments of the respondents in this study that more time at the bedside is needed, the amount of time that should be optimally spent at the bedside remains unclear. Research to improve the quality of bedside learning and its influence on patient care outcomes is needed.

- ,,,.Improving bedside teaching: findings from a focus group study of learners.Acad Med.2008;83(3):257–264.

- .On bedside teaching.Ann Intern Med.1997;126(3):217–220.

- ,,,.Whither bedside teaching? A focus‐group study of clinical teachers.Acad Med.2003;78(4):384–390.

- .Bedside rounds revisited.N Engl J Med.1997;336(16):1174–1175.

- ,,,.Effect of a physical examination teaching program on the behavior of medical residents.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20(8):710–714.

- ,,,,.Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts.Acad Med.2006;81(7):661–667.

- ,,.Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching.Med Educ.1997;31(5):341–346.

- .Hospitalists in the United States—mission accomplished or work in progress?N Engl J Med.2004;350(19):1935–1936.

- ,,,,.The effect of bedside case presentations on patients' perceptions of their medical care.N Engl J Med.1997;336(16):1150–1155.

- ,,,.A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference‐room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit.Pediatrics.2007;120(2):275–280.

- ,,.Impediments to bed‐side teaching.Med Educ.1998;32(2):159–162.

- ,,, et al.Internal medicine and general surgery residents' attitudes about the ACGME duty hours regulations: a multicenter study.Acad Med.2006;81(12):1052–1058.

- ,,.Resident as teacher: educating the educators.Mt Sinai J Med.2006;73(8):1165–1169.

Bedside teaching, defined as teaching in the presence of a patient, has been an integral, respected part of medical education throughout the history of modern medicine. There is widespread concern among medical educators that bedside teaching is declining, and in particular, physical examination teaching.1‐5 Learning at the bedside accounted for 75% of clinical teaching in the 1960s and only 16% by 1978.2 Current estimates range from 8% to 19%.1

The bedside is the ideal venue for demonstrating, observing, and evaluating medical interviewing skills, physical examination techniques, and interpersonal and communication skills. Role modeling is the primary method by which clinical teachers demonstrate and teach professionalism and humanistic behavior.6 The bedside is also a place to develop clinical reasoning skills, stimulate problem‐based learning,7 and demonstrate teamwork.4 Thus, the decline in bedside teaching is of major concern for more than just the dying of a time‐honored tradition, but for the threat to the development of skills and attitudes essential for the practice of medicine.

With the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists and their presence at most major U.S. teaching hospitals, internal medicine residents and medical students in their medicine clerkships receive much of their inpatient training from attending physicians who are hospitalists.8 Little is known about the teaching practices of hospitalist attending physicians. We investigated the fraction of time hospitalist attending physicians spend at the bedside during attending teaching rounds and the frequency of the demonstration of physical examination skills at 1 academic teaching hospital.

Patients and Methods

The Brigham & Women's Hospitalist Service, a 28‐member academic hospitalist group who serve as both the teaching attendings and patient care attendings on 4 general medicine teams, was studied in a prospective, observational fashion. Internal medicine residents at Brigham & Women's Hospital rotating on the hospitalist service were identified by examining the schedule of inpatient rotations during the 2007‐2008 academic year and were asked to participate in the study via an e‐mail invitation. The Institutional Review Board of Brigham & Women's Hospital approved the study.

Teams were made up of 1 senior resident and 2 interns. Call frequency was every fourth day. Over a period of 23 sequential weekdays, medical residents and interns from each of the 4 hospitalist teams observed and reported the behavior of their attendings on rounds. Their reports captured the fraction of time spent at the bedside during rounds and the frequency of physical examination teaching. Residents and interns were asked to respond to 3 questions in a daily e‐mail. Respondents reported (1) total time spent with their hospitalist attending during attending rounds, (2) time spent inside patient rooms during attending rounds, and (3) whether or not a physical examination finding or skill was demonstrated by their hospitalist attending. When more than 1 team member responded, time reported among team members was averaged and if there was a discrepancy between whether or not a physical examination finding or skill was demonstrated, it was defaulted to the positive response. Hospitalist attendings remained unaware of the daily observations.

Hospitalist attendings were independently invited to complete a baseline needs assessment survey on bedside teaching. Surveys addressed attitudes toward bedside teaching, confidence in ability to lead bedside teaching rounds and teach the physical examination, and adequacy of their own training in these skills. Respondents were asked to comment on obstacles to bedside teaching. Residents were surveyed at the completion of a rotation with a hospitalist attending regarding the value of the time spent at the bedside and their self‐perceived improvement in physical examination skills and bedside teaching skills. The survey solicited the residents' opinion of the most valuable aspect of bedside teaching. The survey questions used a 4‐point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

The fraction of time spent at the bedside during attending hospitalist rounds was calculated from the average time spent in patient rooms and the average time of attending rounds. The frequency of physical examination teaching was expressed as a percent of all teaching encounters. Interrater reliability was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient with the Spearman‐Brown adjustment. Differences between groups were calculated using the Fisher's exact test for counts and the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test for continuous data. Significance was accepted for P < 0.05.

Results

Thirty‐five residents provided observations on 61 of 92 potentially observed attending rounds (66% response rate) over 23 weekdays, including observations of the rounding behavior of 12 different hospitalists. The interrater reliability was 0.91. The average patient census on each team during this time period was 12 (range 6‐19).

Residents reported that their attendings went to the bedside at least once during 37 of these 61 rounds (61%), and provided physical examination teaching during 23 of these 61 (38%) encounters. Hospitalists spent an average of 101 minutes on rounds and an average of 17 minutes (17%) of their time inside patient rooms.

Rounds that included time spent at the bedside were significantly longer on average than rounds that did not include time spent at the bedside (122 vs. 69 minutes, P < 0.001). During rounds that included bedside teaching, teams spent an average of 29 minutes (24% of the total time) in patient rooms, and rounds were significantly more likely to include teaching on physical diagnosis (23/37 rounds vs. 0/24 rounds, P < 0.001). Physical examination teaching did not significantly prolong those rounds that included bedside teaching (124 vs. 119 minutes, P = 0.56), but did significantly increase the amount of time spent at the bedside (32 vs. 22 minutes, P = 0.046).

Eighteen hospitalists (64% response) with a mean of 5.9 years of experience as attending physicians completed a needs‐assessment survey (Table 1). Fourteen of the 18 hospitalists (78%) reported that they prioritize bedside teaching and 16 (89%) requested more emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum. Twelve hospitalists (67%) indicated that they were confident in their ability to lead bedside teaching rounds; 9 (50%) were confident in their ability to teach physical examination. Eleven (61%) of the respondents felt poorly prepared to do bedside teaching after completing their residency, and 12 (67%) felt that they had received inadequate training in how to teach the physical examination. Of the obstacles to bedside teaching, time and inadequate training and skills were the most frequently noted, present in 11 and 6 of the reports, respectively. Lack of confidence and lack of role models were also cited in 4 and 2 of the reports, respectively.

| Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| I make bedside teaching a priority | 0 | 22 | 56 | 22 |

| More emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum is needed | 0 | 11 | 39 | 50 |

| I feel confident in my ability to lead bedside teaching rounds | 11 | 22 | 50 | 17 |

| I was well‐prepared to do bedside teaching after residency training | 22 | 39 | 28 | 11 |

| I feel confident in my ability to teach the physical exam | 11 | 39 | 33 | 17 |

| I have received adequate training in how to teach the physical exam | 17 | 50 | 22 | 11 |

Seventeen medical residents (49% response) completed a survey regarding their general medical service rotation with a hospitalist upon its completion (Table 2). Sixteen of the respondents (94%) agreed that time spent at the bedside during hospitalist attending teaching rounds that specific rotation was valuable, and 15 (82%) of the residents sought more emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum. Four of the respondents (24%) reported that their physical examination skills improved over the rotation, 5 (29%) felt better prepared to teach the physical examination, and 9 (53%) felt better prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds. Only 3 (18%) of the respondents reported that they had received helpful feedback on their physical examination skills from their attending. Responding residents noted physical examination teaching, communication and interpersonal skills, focus on patient‐centered care, and integrating the clinical examination with diagnostic and management decisions as the most valuable aspects of bedside teaching.

| Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Time spent at the bedside during teaching rounds was valuable | 0 | 6 | 65 | 29 |

| More emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum is needed | 0 | 18 | 53 | 29 |

| I feel better prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds | 6 | 41 | 53 | 0 |

| My physical exam skills improved over the rotation | 6 | 71 | 24 | 0 |

| I feel better prepared to teach the physical exam | 6 | 65 | 29 | 0 |

| I received helpful feedback on my physical exam skills | 18 | 65 | 18 | 0 |

Discussion

Bedside teaching is highly valued by clinicians and trainees, though there is little evidence supporting its efficacy. Patients also enjoy and are accepting of bedside presentations7, 9, 10 if certain rules are adhered to (eg, avoid medical jargon) and benefit by having a better understanding of their illness.9 This study supports previous views of medical residents, students,1, 5, 7 and faculty11 of the value and need for greater emphasis on bedside teaching in medical education.

This study of rounding behavior found that hospitalists in this academic center go to the bedside most days, but 39% of attending teaching rounds did not include a bedside encounter. Physical examination teaching is infrequent. Though time spent at the bedside was only a small fraction of total teaching time (17%) in this practice, this fraction is at the high end of previous reports. Teaching rounds that did not include bedside teaching most likely occurred in the confines of a conference room.

Many factors appear to contribute to the paucity of time spent at the bedside: time constraints, shorter hospital stays, greater work demands,11 residency duty‐hour regulations,12 declining bedside teaching skills, unrealistic expectations of the encounter, and erosion of the teaching ethic.3 A decline in clinical examination skills among trainees and attending physicians leads to a growing reliance on data and technology, thereby perpetuating the cycle of declining bedside skills.4

The hospitalists in this study identify time as the most dominant obstacle to bedside teaching. On days when hospitalist attending physicians went to the bedside, rounds were on average 53 minutes longer than on those days when they did not go to the bedside. This time increase varied little whether or not physical examination teaching occurred. The difference in rounding time may be partially explained by the admitting cycle and patient census. Teaching attendings are likely to go to the bedside to see new patients on postcall days when the patient census is also the highest.

Many members of this hospitalist group indicated that they felt inadequately prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds. Of those who responded to the survey, 67% did not feel that they received adequate training in how to teach the physical examination. Consequently, only one‐half of responding hospitalists expressed confidence in their ability to teach the physical examination. Not surprisingly, physical examination skills were a component of a minority of teaching sessions and only one‐quarter of the medical residents perceived that their physical examination skills improved during the rotation with a hospitalist attending. The paucity of feedback to the house‐staff likely contributed to this stagnancy. Residents who become hospitalists ill‐prepared to lead bedside teaching and teach the physical examination will perpetuate the decline in bedside teaching.

Though a substantial portion of the hospitalists in this study lacked confidence, an overwhelming majority of medical residents found their time spent at the bedside with a hospitalist to be valuable. More than one‐half of residents reported that they were better prepared to lead bedside teaching after the rotation. Residents recognize that bedside teaching can include communication and clinical reasoning skills. Hospitalists should be made aware that a broad range of skills and content can be taught at the bedside.

Hospitalists have an increasing influence on the education of medical residents and students and are appropriate targets for faculty development programs aimed at improving bedside teaching. As a newer, growing specialty, hospitalists tend to be younger physicians, and are therefore more reliant on the education attained during residency to support their bedside activities. Many residencies have developed resident as educator programs in an attempt to create a future generation of attendings better able to teach.13

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. The study was limited to a hospitalist group at a single academic medical center and relied on resident recall. Though the response rate to the daily e‐mails was relatively low, the interrater reliability was high, and a broad range of residents and attendings were represented. Residents with greater patient censuses may have been too busy to respond, but it is unclear in which direction this would bias the results.

Conclusions

This study provides additional evidence that bedside and physical examination teaching are in decline. Time is an increasingly precious commodity for hospitalists; though many commentators echo the sentiments of the respondents in this study that more time at the bedside is needed, the amount of time that should be optimally spent at the bedside remains unclear. Research to improve the quality of bedside learning and its influence on patient care outcomes is needed.

Bedside teaching, defined as teaching in the presence of a patient, has been an integral, respected part of medical education throughout the history of modern medicine. There is widespread concern among medical educators that bedside teaching is declining, and in particular, physical examination teaching.1‐5 Learning at the bedside accounted for 75% of clinical teaching in the 1960s and only 16% by 1978.2 Current estimates range from 8% to 19%.1

The bedside is the ideal venue for demonstrating, observing, and evaluating medical interviewing skills, physical examination techniques, and interpersonal and communication skills. Role modeling is the primary method by which clinical teachers demonstrate and teach professionalism and humanistic behavior.6 The bedside is also a place to develop clinical reasoning skills, stimulate problem‐based learning,7 and demonstrate teamwork.4 Thus, the decline in bedside teaching is of major concern for more than just the dying of a time‐honored tradition, but for the threat to the development of skills and attitudes essential for the practice of medicine.

With the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists and their presence at most major U.S. teaching hospitals, internal medicine residents and medical students in their medicine clerkships receive much of their inpatient training from attending physicians who are hospitalists.8 Little is known about the teaching practices of hospitalist attending physicians. We investigated the fraction of time hospitalist attending physicians spend at the bedside during attending teaching rounds and the frequency of the demonstration of physical examination skills at 1 academic teaching hospital.

Patients and Methods

The Brigham & Women's Hospitalist Service, a 28‐member academic hospitalist group who serve as both the teaching attendings and patient care attendings on 4 general medicine teams, was studied in a prospective, observational fashion. Internal medicine residents at Brigham & Women's Hospital rotating on the hospitalist service were identified by examining the schedule of inpatient rotations during the 2007‐2008 academic year and were asked to participate in the study via an e‐mail invitation. The Institutional Review Board of Brigham & Women's Hospital approved the study.

Teams were made up of 1 senior resident and 2 interns. Call frequency was every fourth day. Over a period of 23 sequential weekdays, medical residents and interns from each of the 4 hospitalist teams observed and reported the behavior of their attendings on rounds. Their reports captured the fraction of time spent at the bedside during rounds and the frequency of physical examination teaching. Residents and interns were asked to respond to 3 questions in a daily e‐mail. Respondents reported (1) total time spent with their hospitalist attending during attending rounds, (2) time spent inside patient rooms during attending rounds, and (3) whether or not a physical examination finding or skill was demonstrated by their hospitalist attending. When more than 1 team member responded, time reported among team members was averaged and if there was a discrepancy between whether or not a physical examination finding or skill was demonstrated, it was defaulted to the positive response. Hospitalist attendings remained unaware of the daily observations.

Hospitalist attendings were independently invited to complete a baseline needs assessment survey on bedside teaching. Surveys addressed attitudes toward bedside teaching, confidence in ability to lead bedside teaching rounds and teach the physical examination, and adequacy of their own training in these skills. Respondents were asked to comment on obstacles to bedside teaching. Residents were surveyed at the completion of a rotation with a hospitalist attending regarding the value of the time spent at the bedside and their self‐perceived improvement in physical examination skills and bedside teaching skills. The survey solicited the residents' opinion of the most valuable aspect of bedside teaching. The survey questions used a 4‐point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

The fraction of time spent at the bedside during attending hospitalist rounds was calculated from the average time spent in patient rooms and the average time of attending rounds. The frequency of physical examination teaching was expressed as a percent of all teaching encounters. Interrater reliability was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient with the Spearman‐Brown adjustment. Differences between groups were calculated using the Fisher's exact test for counts and the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test for continuous data. Significance was accepted for P < 0.05.

Results

Thirty‐five residents provided observations on 61 of 92 potentially observed attending rounds (66% response rate) over 23 weekdays, including observations of the rounding behavior of 12 different hospitalists. The interrater reliability was 0.91. The average patient census on each team during this time period was 12 (range 6‐19).

Residents reported that their attendings went to the bedside at least once during 37 of these 61 rounds (61%), and provided physical examination teaching during 23 of these 61 (38%) encounters. Hospitalists spent an average of 101 minutes on rounds and an average of 17 minutes (17%) of their time inside patient rooms.

Rounds that included time spent at the bedside were significantly longer on average than rounds that did not include time spent at the bedside (122 vs. 69 minutes, P < 0.001). During rounds that included bedside teaching, teams spent an average of 29 minutes (24% of the total time) in patient rooms, and rounds were significantly more likely to include teaching on physical diagnosis (23/37 rounds vs. 0/24 rounds, P < 0.001). Physical examination teaching did not significantly prolong those rounds that included bedside teaching (124 vs. 119 minutes, P = 0.56), but did significantly increase the amount of time spent at the bedside (32 vs. 22 minutes, P = 0.046).

Eighteen hospitalists (64% response) with a mean of 5.9 years of experience as attending physicians completed a needs‐assessment survey (Table 1). Fourteen of the 18 hospitalists (78%) reported that they prioritize bedside teaching and 16 (89%) requested more emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum. Twelve hospitalists (67%) indicated that they were confident in their ability to lead bedside teaching rounds; 9 (50%) were confident in their ability to teach physical examination. Eleven (61%) of the respondents felt poorly prepared to do bedside teaching after completing their residency, and 12 (67%) felt that they had received inadequate training in how to teach the physical examination. Of the obstacles to bedside teaching, time and inadequate training and skills were the most frequently noted, present in 11 and 6 of the reports, respectively. Lack of confidence and lack of role models were also cited in 4 and 2 of the reports, respectively.

| Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| I make bedside teaching a priority | 0 | 22 | 56 | 22 |

| More emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum is needed | 0 | 11 | 39 | 50 |

| I feel confident in my ability to lead bedside teaching rounds | 11 | 22 | 50 | 17 |

| I was well‐prepared to do bedside teaching after residency training | 22 | 39 | 28 | 11 |

| I feel confident in my ability to teach the physical exam | 11 | 39 | 33 | 17 |

| I have received adequate training in how to teach the physical exam | 17 | 50 | 22 | 11 |

Seventeen medical residents (49% response) completed a survey regarding their general medical service rotation with a hospitalist upon its completion (Table 2). Sixteen of the respondents (94%) agreed that time spent at the bedside during hospitalist attending teaching rounds that specific rotation was valuable, and 15 (82%) of the residents sought more emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum. Four of the respondents (24%) reported that their physical examination skills improved over the rotation, 5 (29%) felt better prepared to teach the physical examination, and 9 (53%) felt better prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds. Only 3 (18%) of the respondents reported that they had received helpful feedback on their physical examination skills from their attending. Responding residents noted physical examination teaching, communication and interpersonal skills, focus on patient‐centered care, and integrating the clinical examination with diagnostic and management decisions as the most valuable aspects of bedside teaching.

| Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Time spent at the bedside during teaching rounds was valuable | 0 | 6 | 65 | 29 |

| More emphasis on bedside teaching in the residency curriculum is needed | 0 | 18 | 53 | 29 |

| I feel better prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds | 6 | 41 | 53 | 0 |

| My physical exam skills improved over the rotation | 6 | 71 | 24 | 0 |

| I feel better prepared to teach the physical exam | 6 | 65 | 29 | 0 |

| I received helpful feedback on my physical exam skills | 18 | 65 | 18 | 0 |

Discussion

Bedside teaching is highly valued by clinicians and trainees, though there is little evidence supporting its efficacy. Patients also enjoy and are accepting of bedside presentations7, 9, 10 if certain rules are adhered to (eg, avoid medical jargon) and benefit by having a better understanding of their illness.9 This study supports previous views of medical residents, students,1, 5, 7 and faculty11 of the value and need for greater emphasis on bedside teaching in medical education.

This study of rounding behavior found that hospitalists in this academic center go to the bedside most days, but 39% of attending teaching rounds did not include a bedside encounter. Physical examination teaching is infrequent. Though time spent at the bedside was only a small fraction of total teaching time (17%) in this practice, this fraction is at the high end of previous reports. Teaching rounds that did not include bedside teaching most likely occurred in the confines of a conference room.

Many factors appear to contribute to the paucity of time spent at the bedside: time constraints, shorter hospital stays, greater work demands,11 residency duty‐hour regulations,12 declining bedside teaching skills, unrealistic expectations of the encounter, and erosion of the teaching ethic.3 A decline in clinical examination skills among trainees and attending physicians leads to a growing reliance on data and technology, thereby perpetuating the cycle of declining bedside skills.4

The hospitalists in this study identify time as the most dominant obstacle to bedside teaching. On days when hospitalist attending physicians went to the bedside, rounds were on average 53 minutes longer than on those days when they did not go to the bedside. This time increase varied little whether or not physical examination teaching occurred. The difference in rounding time may be partially explained by the admitting cycle and patient census. Teaching attendings are likely to go to the bedside to see new patients on postcall days when the patient census is also the highest.

Many members of this hospitalist group indicated that they felt inadequately prepared to lead bedside teaching rounds. Of those who responded to the survey, 67% did not feel that they received adequate training in how to teach the physical examination. Consequently, only one‐half of responding hospitalists expressed confidence in their ability to teach the physical examination. Not surprisingly, physical examination skills were a component of a minority of teaching sessions and only one‐quarter of the medical residents perceived that their physical examination skills improved during the rotation with a hospitalist attending. The paucity of feedback to the house‐staff likely contributed to this stagnancy. Residents who become hospitalists ill‐prepared to lead bedside teaching and teach the physical examination will perpetuate the decline in bedside teaching.

Though a substantial portion of the hospitalists in this study lacked confidence, an overwhelming majority of medical residents found their time spent at the bedside with a hospitalist to be valuable. More than one‐half of residents reported that they were better prepared to lead bedside teaching after the rotation. Residents recognize that bedside teaching can include communication and clinical reasoning skills. Hospitalists should be made aware that a broad range of skills and content can be taught at the bedside.

Hospitalists have an increasing influence on the education of medical residents and students and are appropriate targets for faculty development programs aimed at improving bedside teaching. As a newer, growing specialty, hospitalists tend to be younger physicians, and are therefore more reliant on the education attained during residency to support their bedside activities. Many residencies have developed resident as educator programs in an attempt to create a future generation of attendings better able to teach.13

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. The study was limited to a hospitalist group at a single academic medical center and relied on resident recall. Though the response rate to the daily e‐mails was relatively low, the interrater reliability was high, and a broad range of residents and attendings were represented. Residents with greater patient censuses may have been too busy to respond, but it is unclear in which direction this would bias the results.

Conclusions

This study provides additional evidence that bedside and physical examination teaching are in decline. Time is an increasingly precious commodity for hospitalists; though many commentators echo the sentiments of the respondents in this study that more time at the bedside is needed, the amount of time that should be optimally spent at the bedside remains unclear. Research to improve the quality of bedside learning and its influence on patient care outcomes is needed.

- ,,,.Improving bedside teaching: findings from a focus group study of learners.Acad Med.2008;83(3):257–264.

- .On bedside teaching.Ann Intern Med.1997;126(3):217–220.

- ,,,.Whither bedside teaching? A focus‐group study of clinical teachers.Acad Med.2003;78(4):384–390.

- .Bedside rounds revisited.N Engl J Med.1997;336(16):1174–1175.

- ,,,.Effect of a physical examination teaching program on the behavior of medical residents.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20(8):710–714.

- ,,,,.Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts.Acad Med.2006;81(7):661–667.

- ,,.Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching.Med Educ.1997;31(5):341–346.

- .Hospitalists in the United States—mission accomplished or work in progress?N Engl J Med.2004;350(19):1935–1936.

- ,,,,.The effect of bedside case presentations on patients' perceptions of their medical care.N Engl J Med.1997;336(16):1150–1155.

- ,,,.A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference‐room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit.Pediatrics.2007;120(2):275–280.

- ,,.Impediments to bed‐side teaching.Med Educ.1998;32(2):159–162.

- ,,, et al.Internal medicine and general surgery residents' attitudes about the ACGME duty hours regulations: a multicenter study.Acad Med.2006;81(12):1052–1058.

- ,,.Resident as teacher: educating the educators.Mt Sinai J Med.2006;73(8):1165–1169.

- ,,,.Improving bedside teaching: findings from a focus group study of learners.Acad Med.2008;83(3):257–264.

- .On bedside teaching.Ann Intern Med.1997;126(3):217–220.

- ,,,.Whither bedside teaching? A focus‐group study of clinical teachers.Acad Med.2003;78(4):384–390.

- .Bedside rounds revisited.N Engl J Med.1997;336(16):1174–1175.

- ,,,.Effect of a physical examination teaching program on the behavior of medical residents.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20(8):710–714.

- ,,,,.Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts.Acad Med.2006;81(7):661–667.

- ,,.Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching.Med Educ.1997;31(5):341–346.

- .Hospitalists in the United States—mission accomplished or work in progress?N Engl J Med.2004;350(19):1935–1936.

- ,,,,.The effect of bedside case presentations on patients' perceptions of their medical care.N Engl J Med.1997;336(16):1150–1155.

- ,,,.A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference‐room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit.Pediatrics.2007;120(2):275–280.

- ,,.Impediments to bed‐side teaching.Med Educ.1998;32(2):159–162.

- ,,, et al.Internal medicine and general surgery residents' attitudes about the ACGME duty hours regulations: a multicenter study.Acad Med.2006;81(12):1052–1058.

- ,,.Resident as teacher: educating the educators.Mt Sinai J Med.2006;73(8):1165–1169.

Copyright © 2009 Society of Hospital Medicine

A numbered day in the life

It seemed like years had passed since he was told he had cancer. While he basked in the cool white ambiance of the examination room, Jim mentally traced his many steps up and down the nearby hospital hallways. From this room to that, he had shuffled through most of the rooms on this hospital ward. Jim had read every outdated Time and National Geographic magazine, and all of the kids' books. From sitting in waiting rooms, he had even developed a deep appreciation for Thomas the Tank Engine. As he sat there, he realized that he had only spent 8 days in this hospital ward. But in here, 8 days might as well be 11 years. Time doesn't so much pass in hospital wards as it stands perfectly still on your chest. The total isolation for those who must stay is startling. Jim had begun judging time by the movements of those lucky enough to go home. Instead of Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, he was also measuring time by food. Days of the week had become known as Styrofoam meatloaf, highly suspect lasagna, and inedible beef Wellington; all had become units of time measurement.

When he was told about his cancerthe doctor told him it was a type of hematological neo‐something‐or‐otherJim felt strangely aroused by the news. He felt energy racing through his body as he geared for battle. His immediate response was to think about how he would volunteer for the harshest, meanest, nastiest treatment he could get the doctor to agree with. Poke him full of holes, pour poison straight in his veins, run him on treadmills while doing all of thatit didn't matter. There was nothing he would not do to beat this thing. The doctor had finished telling Jim about all those options at the very minute Jim was ready to hear them. Whatever, whatever, Doc, let's get going with this, was his response.

Then, he had gradually noticed that the pace of medicine was something a little less urgent than he had thought. On TV the doctors run everywhere, but here they walked with a brisk but awkward gait, as if afraid of falling on the floor by going too fast. While waiting for his appointments, Jim noticed that everything was about waitingwaiting for everything. Nothing happens in the hospital. There are people walking everywhere with some projected sense of purpose but it all seems so meaningless when there's a hundred people in hospital uniforms walking past a whole room of patients.

Finally, the door to the examination room burst open and in walked Dr. Day. Standing slightly less than 6 feet tall, Docas Jim called himwas one of those well‐preserved 50‐year‐olds who could be found wind‐surfing his way back to his convertible sports car during his off‐hours. Jim imagined that Doc had been the star student, the handsome rover, the jock. Age had started to claw at his youthful looks, but vanity had led the charge against age for Doc. His behavior and choices worked against his clock, and he was not going quietly into that dark night. Doc's athletic stride made it seem like his feet never touched the floor, and he wafted deep into the room before the doors had even fully opened. Doc never looked forward, but always studied the charts in front of him. He was intense; it was as if he had to truly concentrate sometimes to keep pace with his own mind. Doc was talking, but it was unclear to whom. Finally, he looked up with an expectant pause, and Jim, battered with indifference, nodded in affirmationto what, he didn't care. Doc then gave Jim the thumbs‐up, turned on his heel and headed toward the door; he spun around on the spot and looked back, Yeah, you'll need to change into a robe with nothing on underneath it. He gestured to the one wall where a shelf held neatly folded paper‐thin gowns. Jim put one on and could barely believe how sheer it was. It had the density of a paper napkin, he thought. Then again, this was hardly a cause for modesty. The cancer, he had learned, was actually lymphoma, and it had settled in his groin. At first, Jim was ashamed to have doctors and nurses poke and prod his nether regions, but after a while he became quite causal about it with the usual array of doctors and nurses who populated his monotonous life in this shiny new white palace. After the requisite 15 minutes of unexplained absence, Dr. Day returned through the doors. There was something different about him now, and in a world so dominated by sameness, predictability, and routine, change was a dark storm cloud and sudden wind in Jim's mind.

Lie down on that table please, Doc said in his usual my hand may be making a tactile map of your groin, but my mind is in Bermuda manner. As Jim hopped up on the table and shifted his diseased area closer to the end, the Doc seemed to brighten up, Stay right there, he said as he moved quickly from the room once again. Jim pondered the instruction. As opposed to going where? Jim groaned. He would go somewhere, but his treatment, eventually, would happen here. If he left, he didn't know if would ever come back.

In through the door, one more time, came Dr. Day, but this time he seemed to be leading some kind of tour. Trailing behind him in different states of interest and alertness was a team of young people, all in the little training smocks they give them that look just like the big‐boy coat that Dr. Day wore. Their smocks were more wrinkled and more ivory colored, but they still looked official. Dr. Day hardly looked toward the patient as he smoothly rolled into the side of the table nearest Jim's now‐exposed groin.

Jim looked up between his upstretched knees to see them, all of them, standing around trying to decide if they should be looking at the Doc or looking at the affected area. Jim was embarrassed. Jim was mad. Jim was embarrassed again. He tried to make eye contact with every single visitor in the room, and all he could see were eyes looking straight down under the flap of his hospital gown. Doc had broken into his whole song and dance when he stopped short and looked to Jim, almost apologetically, You're alright with this, right? These are first‐year residents and I wanted them to see this kind of tumor up close. Doc hardly took a full breath and he had turned and was back into his blather about mito, crypto, this, that, and some other bullshit. Jim felt like if he rested his head back maybe no one would ever know that he was the real fleshy cadaver that they stared at that day. He might never see any of these students again, and even if he did, none of them could bring themselves to look him anywhere near the eye anyway. Not much danger that any of them could pick him out of a police lineup, even if he did it without any pants on.

It's important to palpate the region, each of you need to feel what this is like, starting with you. Jim heard this particular instruction and snapped his head up to see exactly where the students were now headed to see and feel the thing they just had to touch. Imagine his dismay when he saw that all of them were still there, still transfixed on whatever they had found to look at studiously during this whole period of time. Doc had motioned to the smallest, frailest, most out‐of‐her‐element young woman he had ever seen. She visibly swallowed hard at the news that she would be first. Her eyes, previously fixed without distraction on some point on Jim's leg, now began to frantically search the eyes of others, possibly looking for some permission to run away. Her eyes met Jim's quite by accident, and she shared with him a look of total and complete shame. He took out his annoyance on her by fixing her with a murderous stare, while he watched as her hand inched ever closer to his leg. In a continuous, but painfully slow motion, she reached under the robe and Jim felt the slightest touch of what he assumed was her finger come to rest on the lowest part of his abdomen. She held her finger there, motionless, and then drew it away quickly while nodding to the Doc. No, no, no, you have to really feel it! Doc chided. He reached down and poked the area firmly, but with a certainty and comfort that comes only from unspoken familiarity. Doc then grabbed the poor girl's hand and guided it and proceeded, with his hand holding her wrist, to make the poking motion with her hand. She was clearly horrified and would have rather been poking through the exposed abdomen of a cadaver at that point. Jim's mood became even more annoyed at her response. It was okay to be embarrassed, but she was now acting like his groin was Elephant‐Man‐esque in its hideousness. He wondered if Doc would set up a barker stand and call to the passers‐by to see the bulbous freak, 50 cents for a viewing! Don't forget about our snack tents! Nobody should go home without candy, everybody loves candy!

After the young resident had endured all that the Doc thought she should, he motioned to the next one and repeated the same process; one after another, after another. The students instinctively formed a line that snaked around the table and spilled out through the room. Jim became callous at this point and began chatting up the students while they stood, quietly waiting their turn for the guided poking, to make them feel even more uncomfortable and intimidated. Jim spied one extremely uncomfortable‐looking male student. You know, if you like this, it doesn't make you gay, Jim shared in an almost caring tone. As the target of his comments shuffled forward, eyes never leaving the floor, Jim targeted another victim with his comments, and then another, and then another. Jim became a sniper of sarcasm, picking off helpless young residents as they stood helplessly in his aim. Doc finally reacted to Jim and shot him a scolding look. Doc leaned into Jim's ear, Fun is fun, but let's just take it easy now, ok? Jim grunted in disagreement, but complied. There was no anger left to vent, and really no need to vent it. Residents weren't the problem, but it was easy to treat them that way. Besides, Jim figured there was many more days for him to make it up to them by being a nicer patient. Today was today, but there were probably 20 more tomorrows for him here.

Finally, the last student had his moment. Jim noticed that the region was now sore from the guiding probing, and Doc had his back to him while addressing the students about what they had seen there today. Jim hopped off the table and proceeded to change back into his clothes while Doc carried on talking. Then, Doc was gone; he sped from the room with his entourage in close pursuit. Jim finished dressing and shuffled down the hallway to his room. Jim sighed under the weight of monotony. Every day was the same, and only the torturous delight he enjoyed at the expense of those residents made the day unique. It was, for the most part, emotion that broke the routine. Emotion was the only thing that Jim controlled at this point, and occasionally, selfishly, he would let it loose on the unsuspecting, simply to bookmark his day. Cancer was not killing Jim, but boredom quite possibly could. As Jim passed the drink machine around the corner from his ward, he saw nurse Janet coming in to work with her neon pink lunch kit slung over her shoulder. She smiled at Jim and asked him how he was feeling. Jim smiled, told her all was getting better, and then made his way back to his room. Janet's arrival meant it was almost supper time, and today was lasagna.

It seemed like years had passed since he was told he had cancer. While he basked in the cool white ambiance of the examination room, Jim mentally traced his many steps up and down the nearby hospital hallways. From this room to that, he had shuffled through most of the rooms on this hospital ward. Jim had read every outdated Time and National Geographic magazine, and all of the kids' books. From sitting in waiting rooms, he had even developed a deep appreciation for Thomas the Tank Engine. As he sat there, he realized that he had only spent 8 days in this hospital ward. But in here, 8 days might as well be 11 years. Time doesn't so much pass in hospital wards as it stands perfectly still on your chest. The total isolation for those who must stay is startling. Jim had begun judging time by the movements of those lucky enough to go home. Instead of Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, he was also measuring time by food. Days of the week had become known as Styrofoam meatloaf, highly suspect lasagna, and inedible beef Wellington; all had become units of time measurement.

When he was told about his cancerthe doctor told him it was a type of hematological neo‐something‐or‐otherJim felt strangely aroused by the news. He felt energy racing through his body as he geared for battle. His immediate response was to think about how he would volunteer for the harshest, meanest, nastiest treatment he could get the doctor to agree with. Poke him full of holes, pour poison straight in his veins, run him on treadmills while doing all of thatit didn't matter. There was nothing he would not do to beat this thing. The doctor had finished telling Jim about all those options at the very minute Jim was ready to hear them. Whatever, whatever, Doc, let's get going with this, was his response.

Then, he had gradually noticed that the pace of medicine was something a little less urgent than he had thought. On TV the doctors run everywhere, but here they walked with a brisk but awkward gait, as if afraid of falling on the floor by going too fast. While waiting for his appointments, Jim noticed that everything was about waitingwaiting for everything. Nothing happens in the hospital. There are people walking everywhere with some projected sense of purpose but it all seems so meaningless when there's a hundred people in hospital uniforms walking past a whole room of patients.

Finally, the door to the examination room burst open and in walked Dr. Day. Standing slightly less than 6 feet tall, Docas Jim called himwas one of those well‐preserved 50‐year‐olds who could be found wind‐surfing his way back to his convertible sports car during his off‐hours. Jim imagined that Doc had been the star student, the handsome rover, the jock. Age had started to claw at his youthful looks, but vanity had led the charge against age for Doc. His behavior and choices worked against his clock, and he was not going quietly into that dark night. Doc's athletic stride made it seem like his feet never touched the floor, and he wafted deep into the room before the doors had even fully opened. Doc never looked forward, but always studied the charts in front of him. He was intense; it was as if he had to truly concentrate sometimes to keep pace with his own mind. Doc was talking, but it was unclear to whom. Finally, he looked up with an expectant pause, and Jim, battered with indifference, nodded in affirmationto what, he didn't care. Doc then gave Jim the thumbs‐up, turned on his heel and headed toward the door; he spun around on the spot and looked back, Yeah, you'll need to change into a robe with nothing on underneath it. He gestured to the one wall where a shelf held neatly folded paper‐thin gowns. Jim put one on and could barely believe how sheer it was. It had the density of a paper napkin, he thought. Then again, this was hardly a cause for modesty. The cancer, he had learned, was actually lymphoma, and it had settled in his groin. At first, Jim was ashamed to have doctors and nurses poke and prod his nether regions, but after a while he became quite causal about it with the usual array of doctors and nurses who populated his monotonous life in this shiny new white palace. After the requisite 15 minutes of unexplained absence, Dr. Day returned through the doors. There was something different about him now, and in a world so dominated by sameness, predictability, and routine, change was a dark storm cloud and sudden wind in Jim's mind.

Lie down on that table please, Doc said in his usual my hand may be making a tactile map of your groin, but my mind is in Bermuda manner. As Jim hopped up on the table and shifted his diseased area closer to the end, the Doc seemed to brighten up, Stay right there, he said as he moved quickly from the room once again. Jim pondered the instruction. As opposed to going where? Jim groaned. He would go somewhere, but his treatment, eventually, would happen here. If he left, he didn't know if would ever come back.

In through the door, one more time, came Dr. Day, but this time he seemed to be leading some kind of tour. Trailing behind him in different states of interest and alertness was a team of young people, all in the little training smocks they give them that look just like the big‐boy coat that Dr. Day wore. Their smocks were more wrinkled and more ivory colored, but they still looked official. Dr. Day hardly looked toward the patient as he smoothly rolled into the side of the table nearest Jim's now‐exposed groin.

Jim looked up between his upstretched knees to see them, all of them, standing around trying to decide if they should be looking at the Doc or looking at the affected area. Jim was embarrassed. Jim was mad. Jim was embarrassed again. He tried to make eye contact with every single visitor in the room, and all he could see were eyes looking straight down under the flap of his hospital gown. Doc had broken into his whole song and dance when he stopped short and looked to Jim, almost apologetically, You're alright with this, right? These are first‐year residents and I wanted them to see this kind of tumor up close. Doc hardly took a full breath and he had turned and was back into his blather about mito, crypto, this, that, and some other bullshit. Jim felt like if he rested his head back maybe no one would ever know that he was the real fleshy cadaver that they stared at that day. He might never see any of these students again, and even if he did, none of them could bring themselves to look him anywhere near the eye anyway. Not much danger that any of them could pick him out of a police lineup, even if he did it without any pants on.

It's important to palpate the region, each of you need to feel what this is like, starting with you. Jim heard this particular instruction and snapped his head up to see exactly where the students were now headed to see and feel the thing they just had to touch. Imagine his dismay when he saw that all of them were still there, still transfixed on whatever they had found to look at studiously during this whole period of time. Doc had motioned to the smallest, frailest, most out‐of‐her‐element young woman he had ever seen. She visibly swallowed hard at the news that she would be first. Her eyes, previously fixed without distraction on some point on Jim's leg, now began to frantically search the eyes of others, possibly looking for some permission to run away. Her eyes met Jim's quite by accident, and she shared with him a look of total and complete shame. He took out his annoyance on her by fixing her with a murderous stare, while he watched as her hand inched ever closer to his leg. In a continuous, but painfully slow motion, she reached under the robe and Jim felt the slightest touch of what he assumed was her finger come to rest on the lowest part of his abdomen. She held her finger there, motionless, and then drew it away quickly while nodding to the Doc. No, no, no, you have to really feel it! Doc chided. He reached down and poked the area firmly, but with a certainty and comfort that comes only from unspoken familiarity. Doc then grabbed the poor girl's hand and guided it and proceeded, with his hand holding her wrist, to make the poking motion with her hand. She was clearly horrified and would have rather been poking through the exposed abdomen of a cadaver at that point. Jim's mood became even more annoyed at her response. It was okay to be embarrassed, but she was now acting like his groin was Elephant‐Man‐esque in its hideousness. He wondered if Doc would set up a barker stand and call to the passers‐by to see the bulbous freak, 50 cents for a viewing! Don't forget about our snack tents! Nobody should go home without candy, everybody loves candy!