User login

Why off-label isn’t off base

Dear Dr. Mossman:

When I was a resident, attending physicians occasionally cited journal articles in their consultation notes to substantiate their treatment choices. Since then, I’ve done this at times when I’ve prescribed a drug off-label.

Recently, I mentioned this practice to a physician who is trained as a lawyer. He thought citing articles in a patient’s chart was a bad idea, because by doing so I was automatically making the referred-to article the “expert witness.” If a lawsuit occurred, I might be called upon to justify the article’s validity, statistical details, methodology, etc. My intent is to show that I have a detailed, well-thought-out justification for my treatment choice.

Am I placing myself at greater risk of incurring liability should a lawsuit occur?—Submitted by “Dr. W”

Dr. W wants to know how he can minimize malpractice risk when prescribing a medication off label and wonders if citing an article in a patient’s chart is a good or bad idea. In law school, attorneys-in-training learn to answer very general legal questions with, “It depends.” There’s little certainty about how to avoid successful malpractice litigation, because few if any strategies have been tested systematically. However, this article will explain—and hopefully help you avoid—the medicolegal pitfalls of off-label prescribing.

Off-label: ‘Accepted and necessary’

Off-label prescribing occurs when a physician prescribes a medication or uses a medical device outside the scope of FDA-approved labeling. Most commonly, off-label use involves prescribing a medication for something other than its FDA-approved indication—such as sildenafil for women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.1

Other examples are prescribing a drug:

- at an unapproved dose

- in an unapproved format, such as mixing capsule contents with applesauce

- outside the approved age group

- for longer than the approved interval

- at a different dose schedule, such as qhs instead of bid or tid.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at douglas.mossman@dowdenhealth.com.

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online marketplace of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Typically, it takes years for a new drug to gain FDA approval and additional time for an already-approved drug to gain approval for a new indication. In the mean-time, clinicians treat their patients with available drugs prescribed off-label.

Off-label prescribing is legal. FDA approval means drugs may be sold and marketed in specific ways, but the FDA does not tell physicians how they can use approved drugs. As each edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference explains, “Once a product has been approved for marketing, a physician may prescribe it for uses or in treatment regimens or patient populations that are not included in approved labeling.”2 Federal statutes state that FDA approval does not “limit or interfere with the authority of a health care practitioner to prescribe” approved drugs or devices “for any condition or disease.”3

Courts endorse off-label prescribing. As 1 appellate decision states, “Because the pace of medical discovery runs ahead of the FDA’s regulatory machinery, the off-label use of some drugs is frequently considered to be ‘state-of-the-art’ treatment.”4 The U.S. Supreme Court has concluded that off-label prescribing “is an accepted and necessary corollary of the FDA’s mission to regulate.”5

Limited testing for safety and effectiveness. Experiences such as “Fen-phen” for weight loss11 and estrogens for preventing vascular disease in postmenopausal women12 remind physicians that some untested treatments may do more harm than good.

Commercial influence. Pharmaceutical companies have used advisory boards, consultant meetings, and continuing medical education events to promote unproven off-label indications for drugs.13,14 Many studies ostensibly designed and proposed by researchers show evidence of “ghost authorship” by commercial concerns.15

Study bias. Even published, peer-reviewed, double-blind studies might not sufficiently support off-label prescribing practices, because sponsors of such studies can structure them or use statistical analyses to make results look favorable. Former editors of the British Medical Journal and the Lancet have acknowledged that their publications unwittingly served as “an extension of the marketing arm” or “laundering operations” for drug manufacturers.16,17 Even for FDA-approved indications, a selective, positive-result publication bias and non-reporting of negative results may make drugs seem more effective than the full range of studies would justify.18

Legal use of labeling. Though off-label prescribing is accepted medical practice, doctors “may be found negligent if their decision to use a drug off-label is sufficiently careless, imprudent, or unprofessional.”4 During a malpractice lawsuit, plaintiff’s counsel could try to use FDA-approved labeling or prescribing information to establish a presumptive standard of care. Such evidence usually is admissible if it is supported by expert testimony. It places the burden of proof on the defendant physician to show how an off-label use met the standard of care.19

Is off-label use malpractice?

Off-label use is not only legal, it’s often wise medical practice. Many drug uses that now have FDA approval were off-label just a few years ago. Examples include using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder and valproate for bipolar mania. Though fluoxetine is the only FDA-approved drug for treating depression in adolescents, other SSRIs may have a favorable risk-benefit profile.6

Numerous studies have shown that off-label prescribing is common in psychiatry7 and other specialties.8,9 Because the practice is so common, the mere fact that a drug is not FDA-approved for a particular use does not imply that the drug was prescribed negligently.

Are patients human guinea pigs?

Some commentators have suggested that off-label prescribing amounts to human experimentation.10 Without FDA approval, they say physicians lack “hard evidence” that a product is safe and effective, so off-label prescribing is a small-scale clinical trial based on the doctor’s educated guesses. If this reasoning is correct, off-label prescribing would require the same human subject protections used in research, including institution review board approval and special consent forms.

Although this argument sounds plausible, off-label prescribing is not experimentation or research (Box).4,11-19 Researchers investigate hypotheses to obtain generalizable knowledge, whereas medical therapy aims to benefit individual patients. This experimentation/therapy distinction is not perfect because successful off-label treatment of 1 patient might imply beneficial effects for others.10 When courts have looked at this matter, though, they have found that “off-label use…by a physician seeking an optimal treatment for his or her patient is not necessarily…research or an investigational or experimental treatment when the use is customarily followed by physicians.”4

Courts also have said that off-label use does not require special informed consent. Just because a drug is prescribed off-label doesn’t mean it’s risky. FDA approval “is not a material risk inherently involved in a proposed therapy which a physician should have disclosed to a patient prior to the therapy.”20 In other words, a physician is not required to discuss FDA regulatory status—such as off-label uses of a medication—to comply with standards of informed consent. FDA regulatory status has nothing to do with the risks or benefits of a medication and it does not provide information about treatment alternatives.21

What should you do?

Keep abreast of news and scientific evidence concerning drug uses, effects, interactions, and adverse effects, especially when prescribing for uses that are different from the manufacturer’s intended purposes (such as hormone therapy for sex offenders).22

Collect articles on off-label uses, but keep them separate from your patients’ files. Good attorneys are highly skilled at using documents to score legal points, and opposing counsel will prepare questions to focus on the articles’ faults or limitations in isolation.

Know why an article applies to your patient. If you are sued for malpractice, you can use an article to support your treatment choice by explaining how this information contributed to your decision-making.

Tell your patient that the proposed treatment is an off-label use when you obtain consent, even though case law says you don’t have to do this. Telling your patient helps him understand your reasoning and prevents surprises that may give offense. For example, if you prescribe a second-generation antipsychotic for a nonpsychotic patient, you wouldn’t want your patient to think you believe he has schizophrenia when he reads the information his pharmacy attaches to his prescription.

Engage in ongoing informed consent. Uncertainty is part of medical practice and is heightened when doctors prescribe off-label. Ongoing discussions help patients understand, accept, and share that uncertainty.

Document informed consent. This will show—if it becomes necessary—that you and your patient made collaborative, conscientious decisions about treatment.23

Related resources

- Zito JM, Derivan AT, Kratochvil CJ, et al. Off-label psychopharmacologic prescribing for children: history supports close clinical monitoring. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:24. www.capmh.com/content/pdf/1753-2000-2-24.pdf.

- Spiesel S. Prozac on the playground. October 15, 2008. Slate. www.slate.com/id/2202338.

Drug brand names

- Fenfluramine and phentermine • Fen-phen

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Valproate • Depakote

1. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

2. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62nd edition. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, Inc.; 2007.

3. Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21USC §396.

4. Richardson v Miller, 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

5. Buckman Co. v Plaintiffs’ Legal Comm., 531 US 341 (2001).

6. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

7. Baldwin DS, Kosky N. Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:414-422.

8. Conroy S, Choonare I, Impicciatore P, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. Br Med J. 2000;320:79-82.

9. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021-1026.

10. Mehlman MJ. Off-label prescribing. Available at: http://www.thedoctorwillseeyounow.com/articles/bioethics/offlabel_11. Accessed October 21, 2008.

11. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

12. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

13. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.

14. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, et al. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

15. Gøtzsche PC, Hrobjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.

16. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.

17. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

18. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

19. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

20. Klein v Biscup, 673 NE2d 225 (Ohio App 1996).

21. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent: debunking myths and misconceptions. Food Drug Law J. 1998;53:71-104.

22. Shajnfeld A, Krueger RB. Reforming (purportedly) non-punitive responses to sexual offending. Developments in Mental Health Law. 2006;25:81-99.

23. Royal College of Psychiatrists CR142. Use of unlicensed medicine for unlicensed applications in psychiatric practice. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/collegereports/cr/cr142.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2008.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

When I was a resident, attending physicians occasionally cited journal articles in their consultation notes to substantiate their treatment choices. Since then, I’ve done this at times when I’ve prescribed a drug off-label.

Recently, I mentioned this practice to a physician who is trained as a lawyer. He thought citing articles in a patient’s chart was a bad idea, because by doing so I was automatically making the referred-to article the “expert witness.” If a lawsuit occurred, I might be called upon to justify the article’s validity, statistical details, methodology, etc. My intent is to show that I have a detailed, well-thought-out justification for my treatment choice.

Am I placing myself at greater risk of incurring liability should a lawsuit occur?—Submitted by “Dr. W”

Dr. W wants to know how he can minimize malpractice risk when prescribing a medication off label and wonders if citing an article in a patient’s chart is a good or bad idea. In law school, attorneys-in-training learn to answer very general legal questions with, “It depends.” There’s little certainty about how to avoid successful malpractice litigation, because few if any strategies have been tested systematically. However, this article will explain—and hopefully help you avoid—the medicolegal pitfalls of off-label prescribing.

Off-label: ‘Accepted and necessary’

Off-label prescribing occurs when a physician prescribes a medication or uses a medical device outside the scope of FDA-approved labeling. Most commonly, off-label use involves prescribing a medication for something other than its FDA-approved indication—such as sildenafil for women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.1

Other examples are prescribing a drug:

- at an unapproved dose

- in an unapproved format, such as mixing capsule contents with applesauce

- outside the approved age group

- for longer than the approved interval

- at a different dose schedule, such as qhs instead of bid or tid.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at douglas.mossman@dowdenhealth.com.

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online marketplace of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Typically, it takes years for a new drug to gain FDA approval and additional time for an already-approved drug to gain approval for a new indication. In the mean-time, clinicians treat their patients with available drugs prescribed off-label.

Off-label prescribing is legal. FDA approval means drugs may be sold and marketed in specific ways, but the FDA does not tell physicians how they can use approved drugs. As each edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference explains, “Once a product has been approved for marketing, a physician may prescribe it for uses or in treatment regimens or patient populations that are not included in approved labeling.”2 Federal statutes state that FDA approval does not “limit or interfere with the authority of a health care practitioner to prescribe” approved drugs or devices “for any condition or disease.”3

Courts endorse off-label prescribing. As 1 appellate decision states, “Because the pace of medical discovery runs ahead of the FDA’s regulatory machinery, the off-label use of some drugs is frequently considered to be ‘state-of-the-art’ treatment.”4 The U.S. Supreme Court has concluded that off-label prescribing “is an accepted and necessary corollary of the FDA’s mission to regulate.”5

Limited testing for safety and effectiveness. Experiences such as “Fen-phen” for weight loss11 and estrogens for preventing vascular disease in postmenopausal women12 remind physicians that some untested treatments may do more harm than good.

Commercial influence. Pharmaceutical companies have used advisory boards, consultant meetings, and continuing medical education events to promote unproven off-label indications for drugs.13,14 Many studies ostensibly designed and proposed by researchers show evidence of “ghost authorship” by commercial concerns.15

Study bias. Even published, peer-reviewed, double-blind studies might not sufficiently support off-label prescribing practices, because sponsors of such studies can structure them or use statistical analyses to make results look favorable. Former editors of the British Medical Journal and the Lancet have acknowledged that their publications unwittingly served as “an extension of the marketing arm” or “laundering operations” for drug manufacturers.16,17 Even for FDA-approved indications, a selective, positive-result publication bias and non-reporting of negative results may make drugs seem more effective than the full range of studies would justify.18

Legal use of labeling. Though off-label prescribing is accepted medical practice, doctors “may be found negligent if their decision to use a drug off-label is sufficiently careless, imprudent, or unprofessional.”4 During a malpractice lawsuit, plaintiff’s counsel could try to use FDA-approved labeling or prescribing information to establish a presumptive standard of care. Such evidence usually is admissible if it is supported by expert testimony. It places the burden of proof on the defendant physician to show how an off-label use met the standard of care.19

Is off-label use malpractice?

Off-label use is not only legal, it’s often wise medical practice. Many drug uses that now have FDA approval were off-label just a few years ago. Examples include using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder and valproate for bipolar mania. Though fluoxetine is the only FDA-approved drug for treating depression in adolescents, other SSRIs may have a favorable risk-benefit profile.6

Numerous studies have shown that off-label prescribing is common in psychiatry7 and other specialties.8,9 Because the practice is so common, the mere fact that a drug is not FDA-approved for a particular use does not imply that the drug was prescribed negligently.

Are patients human guinea pigs?

Some commentators have suggested that off-label prescribing amounts to human experimentation.10 Without FDA approval, they say physicians lack “hard evidence” that a product is safe and effective, so off-label prescribing is a small-scale clinical trial based on the doctor’s educated guesses. If this reasoning is correct, off-label prescribing would require the same human subject protections used in research, including institution review board approval and special consent forms.

Although this argument sounds plausible, off-label prescribing is not experimentation or research (Box).4,11-19 Researchers investigate hypotheses to obtain generalizable knowledge, whereas medical therapy aims to benefit individual patients. This experimentation/therapy distinction is not perfect because successful off-label treatment of 1 patient might imply beneficial effects for others.10 When courts have looked at this matter, though, they have found that “off-label use…by a physician seeking an optimal treatment for his or her patient is not necessarily…research or an investigational or experimental treatment when the use is customarily followed by physicians.”4

Courts also have said that off-label use does not require special informed consent. Just because a drug is prescribed off-label doesn’t mean it’s risky. FDA approval “is not a material risk inherently involved in a proposed therapy which a physician should have disclosed to a patient prior to the therapy.”20 In other words, a physician is not required to discuss FDA regulatory status—such as off-label uses of a medication—to comply with standards of informed consent. FDA regulatory status has nothing to do with the risks or benefits of a medication and it does not provide information about treatment alternatives.21

What should you do?

Keep abreast of news and scientific evidence concerning drug uses, effects, interactions, and adverse effects, especially when prescribing for uses that are different from the manufacturer’s intended purposes (such as hormone therapy for sex offenders).22

Collect articles on off-label uses, but keep them separate from your patients’ files. Good attorneys are highly skilled at using documents to score legal points, and opposing counsel will prepare questions to focus on the articles’ faults or limitations in isolation.

Know why an article applies to your patient. If you are sued for malpractice, you can use an article to support your treatment choice by explaining how this information contributed to your decision-making.

Tell your patient that the proposed treatment is an off-label use when you obtain consent, even though case law says you don’t have to do this. Telling your patient helps him understand your reasoning and prevents surprises that may give offense. For example, if you prescribe a second-generation antipsychotic for a nonpsychotic patient, you wouldn’t want your patient to think you believe he has schizophrenia when he reads the information his pharmacy attaches to his prescription.

Engage in ongoing informed consent. Uncertainty is part of medical practice and is heightened when doctors prescribe off-label. Ongoing discussions help patients understand, accept, and share that uncertainty.

Document informed consent. This will show—if it becomes necessary—that you and your patient made collaborative, conscientious decisions about treatment.23

Related resources

- Zito JM, Derivan AT, Kratochvil CJ, et al. Off-label psychopharmacologic prescribing for children: history supports close clinical monitoring. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:24. www.capmh.com/content/pdf/1753-2000-2-24.pdf.

- Spiesel S. Prozac on the playground. October 15, 2008. Slate. www.slate.com/id/2202338.

Drug brand names

- Fenfluramine and phentermine • Fen-phen

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Valproate • Depakote

Dear Dr. Mossman:

When I was a resident, attending physicians occasionally cited journal articles in their consultation notes to substantiate their treatment choices. Since then, I’ve done this at times when I’ve prescribed a drug off-label.

Recently, I mentioned this practice to a physician who is trained as a lawyer. He thought citing articles in a patient’s chart was a bad idea, because by doing so I was automatically making the referred-to article the “expert witness.” If a lawsuit occurred, I might be called upon to justify the article’s validity, statistical details, methodology, etc. My intent is to show that I have a detailed, well-thought-out justification for my treatment choice.

Am I placing myself at greater risk of incurring liability should a lawsuit occur?—Submitted by “Dr. W”

Dr. W wants to know how he can minimize malpractice risk when prescribing a medication off label and wonders if citing an article in a patient’s chart is a good or bad idea. In law school, attorneys-in-training learn to answer very general legal questions with, “It depends.” There’s little certainty about how to avoid successful malpractice litigation, because few if any strategies have been tested systematically. However, this article will explain—and hopefully help you avoid—the medicolegal pitfalls of off-label prescribing.

Off-label: ‘Accepted and necessary’

Off-label prescribing occurs when a physician prescribes a medication or uses a medical device outside the scope of FDA-approved labeling. Most commonly, off-label use involves prescribing a medication for something other than its FDA-approved indication—such as sildenafil for women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.1

Other examples are prescribing a drug:

- at an unapproved dose

- in an unapproved format, such as mixing capsule contents with applesauce

- outside the approved age group

- for longer than the approved interval

- at a different dose schedule, such as qhs instead of bid or tid.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at douglas.mossman@dowdenhealth.com.

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online marketplace of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Typically, it takes years for a new drug to gain FDA approval and additional time for an already-approved drug to gain approval for a new indication. In the mean-time, clinicians treat their patients with available drugs prescribed off-label.

Off-label prescribing is legal. FDA approval means drugs may be sold and marketed in specific ways, but the FDA does not tell physicians how they can use approved drugs. As each edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference explains, “Once a product has been approved for marketing, a physician may prescribe it for uses or in treatment regimens or patient populations that are not included in approved labeling.”2 Federal statutes state that FDA approval does not “limit or interfere with the authority of a health care practitioner to prescribe” approved drugs or devices “for any condition or disease.”3

Courts endorse off-label prescribing. As 1 appellate decision states, “Because the pace of medical discovery runs ahead of the FDA’s regulatory machinery, the off-label use of some drugs is frequently considered to be ‘state-of-the-art’ treatment.”4 The U.S. Supreme Court has concluded that off-label prescribing “is an accepted and necessary corollary of the FDA’s mission to regulate.”5

Limited testing for safety and effectiveness. Experiences such as “Fen-phen” for weight loss11 and estrogens for preventing vascular disease in postmenopausal women12 remind physicians that some untested treatments may do more harm than good.

Commercial influence. Pharmaceutical companies have used advisory boards, consultant meetings, and continuing medical education events to promote unproven off-label indications for drugs.13,14 Many studies ostensibly designed and proposed by researchers show evidence of “ghost authorship” by commercial concerns.15

Study bias. Even published, peer-reviewed, double-blind studies might not sufficiently support off-label prescribing practices, because sponsors of such studies can structure them or use statistical analyses to make results look favorable. Former editors of the British Medical Journal and the Lancet have acknowledged that their publications unwittingly served as “an extension of the marketing arm” or “laundering operations” for drug manufacturers.16,17 Even for FDA-approved indications, a selective, positive-result publication bias and non-reporting of negative results may make drugs seem more effective than the full range of studies would justify.18

Legal use of labeling. Though off-label prescribing is accepted medical practice, doctors “may be found negligent if their decision to use a drug off-label is sufficiently careless, imprudent, or unprofessional.”4 During a malpractice lawsuit, plaintiff’s counsel could try to use FDA-approved labeling or prescribing information to establish a presumptive standard of care. Such evidence usually is admissible if it is supported by expert testimony. It places the burden of proof on the defendant physician to show how an off-label use met the standard of care.19

Is off-label use malpractice?

Off-label use is not only legal, it’s often wise medical practice. Many drug uses that now have FDA approval were off-label just a few years ago. Examples include using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder and valproate for bipolar mania. Though fluoxetine is the only FDA-approved drug for treating depression in adolescents, other SSRIs may have a favorable risk-benefit profile.6

Numerous studies have shown that off-label prescribing is common in psychiatry7 and other specialties.8,9 Because the practice is so common, the mere fact that a drug is not FDA-approved for a particular use does not imply that the drug was prescribed negligently.

Are patients human guinea pigs?

Some commentators have suggested that off-label prescribing amounts to human experimentation.10 Without FDA approval, they say physicians lack “hard evidence” that a product is safe and effective, so off-label prescribing is a small-scale clinical trial based on the doctor’s educated guesses. If this reasoning is correct, off-label prescribing would require the same human subject protections used in research, including institution review board approval and special consent forms.

Although this argument sounds plausible, off-label prescribing is not experimentation or research (Box).4,11-19 Researchers investigate hypotheses to obtain generalizable knowledge, whereas medical therapy aims to benefit individual patients. This experimentation/therapy distinction is not perfect because successful off-label treatment of 1 patient might imply beneficial effects for others.10 When courts have looked at this matter, though, they have found that “off-label use…by a physician seeking an optimal treatment for his or her patient is not necessarily…research or an investigational or experimental treatment when the use is customarily followed by physicians.”4

Courts also have said that off-label use does not require special informed consent. Just because a drug is prescribed off-label doesn’t mean it’s risky. FDA approval “is not a material risk inherently involved in a proposed therapy which a physician should have disclosed to a patient prior to the therapy.”20 In other words, a physician is not required to discuss FDA regulatory status—such as off-label uses of a medication—to comply with standards of informed consent. FDA regulatory status has nothing to do with the risks or benefits of a medication and it does not provide information about treatment alternatives.21

What should you do?

Keep abreast of news and scientific evidence concerning drug uses, effects, interactions, and adverse effects, especially when prescribing for uses that are different from the manufacturer’s intended purposes (such as hormone therapy for sex offenders).22

Collect articles on off-label uses, but keep them separate from your patients’ files. Good attorneys are highly skilled at using documents to score legal points, and opposing counsel will prepare questions to focus on the articles’ faults or limitations in isolation.

Know why an article applies to your patient. If you are sued for malpractice, you can use an article to support your treatment choice by explaining how this information contributed to your decision-making.

Tell your patient that the proposed treatment is an off-label use when you obtain consent, even though case law says you don’t have to do this. Telling your patient helps him understand your reasoning and prevents surprises that may give offense. For example, if you prescribe a second-generation antipsychotic for a nonpsychotic patient, you wouldn’t want your patient to think you believe he has schizophrenia when he reads the information his pharmacy attaches to his prescription.

Engage in ongoing informed consent. Uncertainty is part of medical practice and is heightened when doctors prescribe off-label. Ongoing discussions help patients understand, accept, and share that uncertainty.

Document informed consent. This will show—if it becomes necessary—that you and your patient made collaborative, conscientious decisions about treatment.23

Related resources

- Zito JM, Derivan AT, Kratochvil CJ, et al. Off-label psychopharmacologic prescribing for children: history supports close clinical monitoring. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:24. www.capmh.com/content/pdf/1753-2000-2-24.pdf.

- Spiesel S. Prozac on the playground. October 15, 2008. Slate. www.slate.com/id/2202338.

Drug brand names

- Fenfluramine and phentermine • Fen-phen

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Valproate • Depakote

1. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

2. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62nd edition. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, Inc.; 2007.

3. Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21USC §396.

4. Richardson v Miller, 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

5. Buckman Co. v Plaintiffs’ Legal Comm., 531 US 341 (2001).

6. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

7. Baldwin DS, Kosky N. Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:414-422.

8. Conroy S, Choonare I, Impicciatore P, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. Br Med J. 2000;320:79-82.

9. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021-1026.

10. Mehlman MJ. Off-label prescribing. Available at: http://www.thedoctorwillseeyounow.com/articles/bioethics/offlabel_11. Accessed October 21, 2008.

11. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

12. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

13. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.

14. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, et al. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

15. Gøtzsche PC, Hrobjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.

16. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.

17. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

18. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

19. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

20. Klein v Biscup, 673 NE2d 225 (Ohio App 1996).

21. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent: debunking myths and misconceptions. Food Drug Law J. 1998;53:71-104.

22. Shajnfeld A, Krueger RB. Reforming (purportedly) non-punitive responses to sexual offending. Developments in Mental Health Law. 2006;25:81-99.

23. Royal College of Psychiatrists CR142. Use of unlicensed medicine for unlicensed applications in psychiatric practice. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/collegereports/cr/cr142.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2008.

1. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

2. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62nd edition. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, Inc.; 2007.

3. Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21USC §396.

4. Richardson v Miller, 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

5. Buckman Co. v Plaintiffs’ Legal Comm., 531 US 341 (2001).

6. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

7. Baldwin DS, Kosky N. Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:414-422.

8. Conroy S, Choonare I, Impicciatore P, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. Br Med J. 2000;320:79-82.

9. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021-1026.

10. Mehlman MJ. Off-label prescribing. Available at: http://www.thedoctorwillseeyounow.com/articles/bioethics/offlabel_11. Accessed October 21, 2008.

11. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

12. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

13. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.

14. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, et al. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

15. Gøtzsche PC, Hrobjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.

16. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.

17. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

18. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

19. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

20. Klein v Biscup, 673 NE2d 225 (Ohio App 1996).

21. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent: debunking myths and misconceptions. Food Drug Law J. 1998;53:71-104.

22. Shajnfeld A, Krueger RB. Reforming (purportedly) non-punitive responses to sexual offending. Developments in Mental Health Law. 2006;25:81-99.

23. Royal College of Psychiatrists CR142. Use of unlicensed medicine for unlicensed applications in psychiatric practice. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/collegereports/cr/cr142.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2008.

Doctor, my breathing is better when I lie down

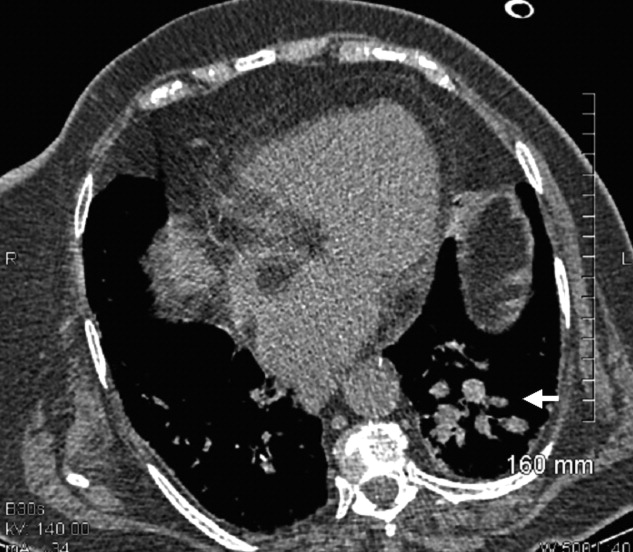

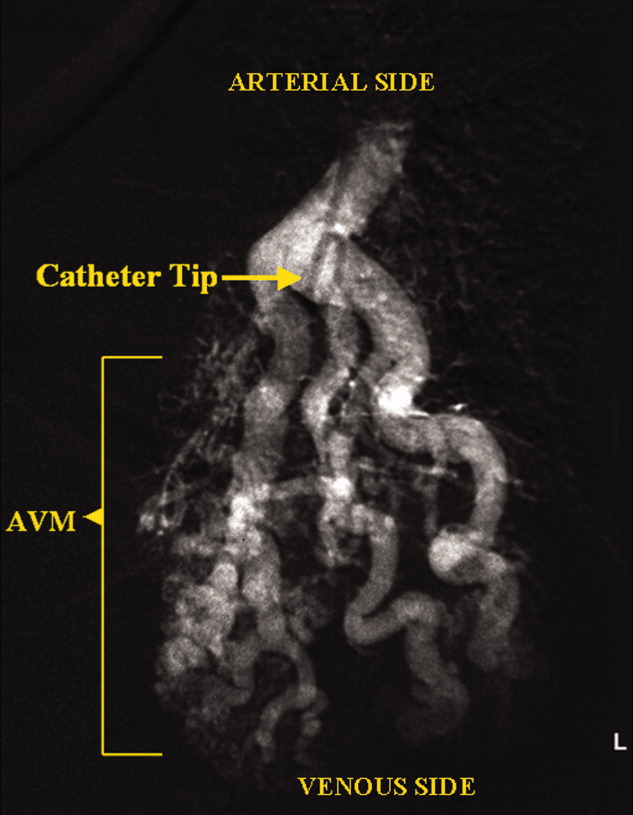

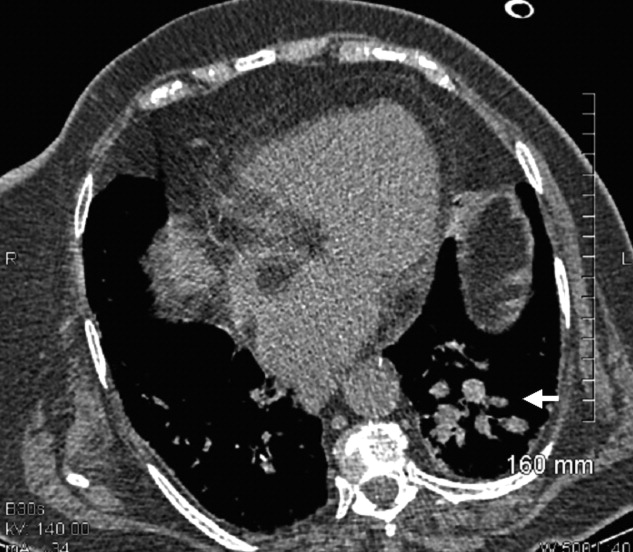

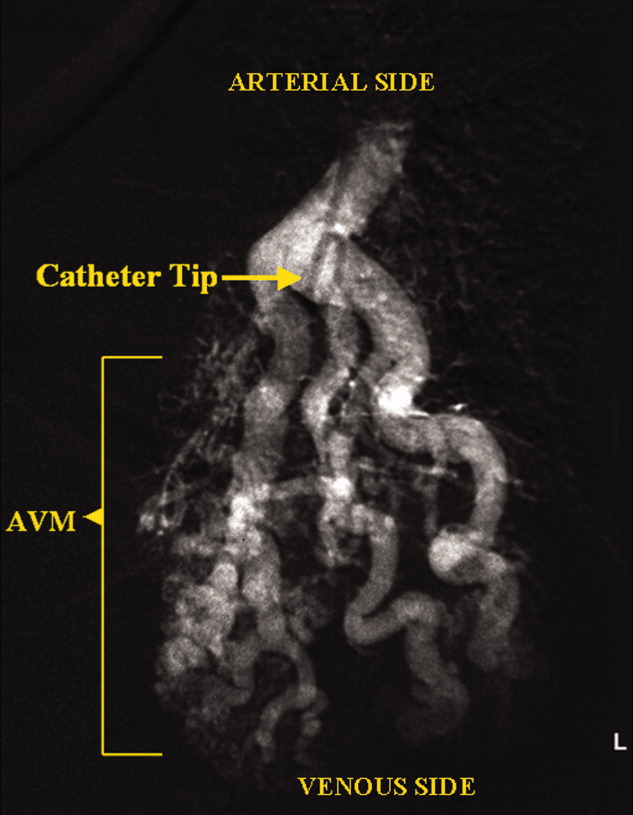

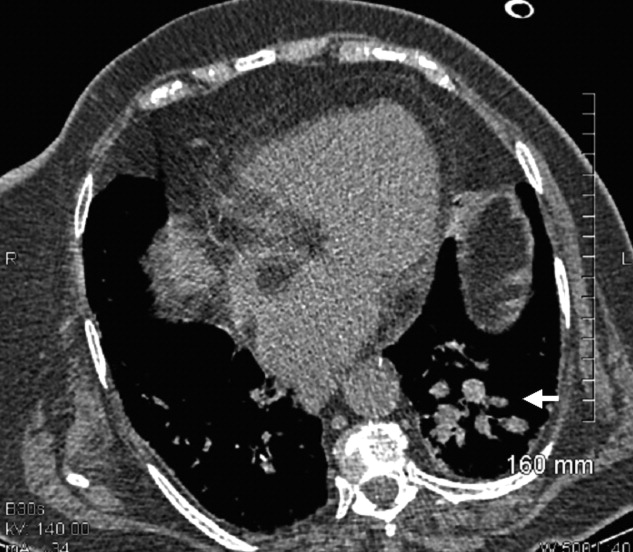

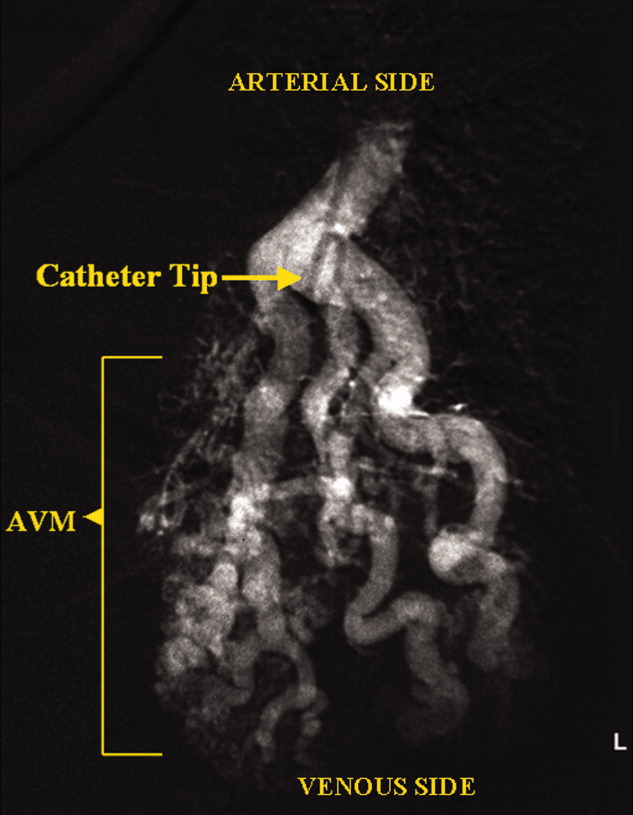

A 73‐year‐old female presented with progressive shortness of breath that was worse in the upright position and was relieved when she was lying flat (platypnea). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a partial pressure of oxygen of 56 mm Hg in the supine position and 42 mm Hg when the patient was seated upright. Chest radiography revealed an ill‐defined density in the left lung base, and a high‐resolution computed tomography scan of the chest revealed dilated arteries and veins in the left lower lobe (Figure 1). Pulmonary angiography showed a huge pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) with a nidus of 7 cm 8 cm involving the left lower lobe (Figure 2; the arrow points to the catheter tip). Embolization therapy was not an option because of the large size of the PAVM, which would have necessitated several coils with an increased risk of systemic embolization. Left lower lobectomy was performed with marked relief of the patient's dyspnea and hypoxemia.

PAVMs are extracardiac shunts caused by abnormal communication between pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia accounts for nearly 84% of PAVMs. PAVMs as complications of the surgical treatment of complex cyanotic congenital heart disease, trauma, and liver disease and sporadic PAVMs, as in our case, are less common. There were no associated signs of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or liver disease in our patient, and gradual enlargement over time likely resulted in the late presentation. Common clinical manifestations of PAVMs include dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. A PAVM may also cause platypnea because of a decrease in blood flow through the PAVM in the dependent portions of the lungs when the patient changes from an upright position to a supine position. This decrease in blood flow though the PAVM causes an improvement in the shortness of breath and hypoxemia as there is decreased right‐to‐left shunting of blood. Treatment is initiated for all symptomatic patients and PAVMs more than 2 cm in diameter. Embolization therapy is preferable because it avoids the risks of major surgery. Surgery is performed for patients with an untreatable allergy to the contrast material and with large PAVMs not technically amenable to embolization therapy, as in our patient.

A 73‐year‐old female presented with progressive shortness of breath that was worse in the upright position and was relieved when she was lying flat (platypnea). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a partial pressure of oxygen of 56 mm Hg in the supine position and 42 mm Hg when the patient was seated upright. Chest radiography revealed an ill‐defined density in the left lung base, and a high‐resolution computed tomography scan of the chest revealed dilated arteries and veins in the left lower lobe (Figure 1). Pulmonary angiography showed a huge pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) with a nidus of 7 cm 8 cm involving the left lower lobe (Figure 2; the arrow points to the catheter tip). Embolization therapy was not an option because of the large size of the PAVM, which would have necessitated several coils with an increased risk of systemic embolization. Left lower lobectomy was performed with marked relief of the patient's dyspnea and hypoxemia.

PAVMs are extracardiac shunts caused by abnormal communication between pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia accounts for nearly 84% of PAVMs. PAVMs as complications of the surgical treatment of complex cyanotic congenital heart disease, trauma, and liver disease and sporadic PAVMs, as in our case, are less common. There were no associated signs of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or liver disease in our patient, and gradual enlargement over time likely resulted in the late presentation. Common clinical manifestations of PAVMs include dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. A PAVM may also cause platypnea because of a decrease in blood flow through the PAVM in the dependent portions of the lungs when the patient changes from an upright position to a supine position. This decrease in blood flow though the PAVM causes an improvement in the shortness of breath and hypoxemia as there is decreased right‐to‐left shunting of blood. Treatment is initiated for all symptomatic patients and PAVMs more than 2 cm in diameter. Embolization therapy is preferable because it avoids the risks of major surgery. Surgery is performed for patients with an untreatable allergy to the contrast material and with large PAVMs not technically amenable to embolization therapy, as in our patient.

A 73‐year‐old female presented with progressive shortness of breath that was worse in the upright position and was relieved when she was lying flat (platypnea). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a partial pressure of oxygen of 56 mm Hg in the supine position and 42 mm Hg when the patient was seated upright. Chest radiography revealed an ill‐defined density in the left lung base, and a high‐resolution computed tomography scan of the chest revealed dilated arteries and veins in the left lower lobe (Figure 1). Pulmonary angiography showed a huge pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) with a nidus of 7 cm 8 cm involving the left lower lobe (Figure 2; the arrow points to the catheter tip). Embolization therapy was not an option because of the large size of the PAVM, which would have necessitated several coils with an increased risk of systemic embolization. Left lower lobectomy was performed with marked relief of the patient's dyspnea and hypoxemia.

PAVMs are extracardiac shunts caused by abnormal communication between pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia accounts for nearly 84% of PAVMs. PAVMs as complications of the surgical treatment of complex cyanotic congenital heart disease, trauma, and liver disease and sporadic PAVMs, as in our case, are less common. There were no associated signs of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or liver disease in our patient, and gradual enlargement over time likely resulted in the late presentation. Common clinical manifestations of PAVMs include dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. A PAVM may also cause platypnea because of a decrease in blood flow through the PAVM in the dependent portions of the lungs when the patient changes from an upright position to a supine position. This decrease in blood flow though the PAVM causes an improvement in the shortness of breath and hypoxemia as there is decreased right‐to‐left shunting of blood. Treatment is initiated for all symptomatic patients and PAVMs more than 2 cm in diameter. Embolization therapy is preferable because it avoids the risks of major surgery. Surgery is performed for patients with an untreatable allergy to the contrast material and with large PAVMs not technically amenable to embolization therapy, as in our patient.

Plane Crash Highlights Hospitalists' Role in MCIs

Mass casualty incidents (MCIs), such as the landing of a US Airways jetliner in New York City's frigid Hudson River, showcase the role hospitalists can play in an ED scrambling to handle a triage scenario.

When the Airbus A320 and its 155 passengers crashed Jan. 15, New York and New Jersey hospitals braced for incoming patients. However, reports showed only a few dozen passengers were treated—the most serious for a fractured leg. Still, at Jersey City (N.J.) Medical Center (JCMC), eight victims brought to the ED meant half a dozen patients had to be discharged to make room.

"The hospitalists were involved only on the periphery this time, as we initially needed their approval to move patients out in anticipation of mass casualties," Douglas Ratner, MD, chairman and program director of JCMC's Department of Medicine, wrote in an e-mail. "They will be integral in future endeavors like this."

To that end, some hospitalists used the "Miracle on the Hudson" as a rallying cry for more training.

"How many of us have gone through rigorous teamwork training to learn to better communicate with our 'cabinmates' during times of stress? Remarkably few," Robert Wachter, MD, a hospitalist as well as a professor and associate chairman of the University of California at San Francisco’s department of medicine, wrote on his blog (the-hospitalist.org/blogs). "How often do we need to demonstrate our continued competency in our specialty? For most board-certified physicians, about every 10 years (up from 'never' 20 years ago). And how well do we learn from our errors? Well, never mind."

Mass casualty incidents (MCIs), such as the landing of a US Airways jetliner in New York City's frigid Hudson River, showcase the role hospitalists can play in an ED scrambling to handle a triage scenario.

When the Airbus A320 and its 155 passengers crashed Jan. 15, New York and New Jersey hospitals braced for incoming patients. However, reports showed only a few dozen passengers were treated—the most serious for a fractured leg. Still, at Jersey City (N.J.) Medical Center (JCMC), eight victims brought to the ED meant half a dozen patients had to be discharged to make room.

"The hospitalists were involved only on the periphery this time, as we initially needed their approval to move patients out in anticipation of mass casualties," Douglas Ratner, MD, chairman and program director of JCMC's Department of Medicine, wrote in an e-mail. "They will be integral in future endeavors like this."

To that end, some hospitalists used the "Miracle on the Hudson" as a rallying cry for more training.

"How many of us have gone through rigorous teamwork training to learn to better communicate with our 'cabinmates' during times of stress? Remarkably few," Robert Wachter, MD, a hospitalist as well as a professor and associate chairman of the University of California at San Francisco’s department of medicine, wrote on his blog (the-hospitalist.org/blogs). "How often do we need to demonstrate our continued competency in our specialty? For most board-certified physicians, about every 10 years (up from 'never' 20 years ago). And how well do we learn from our errors? Well, never mind."

Mass casualty incidents (MCIs), such as the landing of a US Airways jetliner in New York City's frigid Hudson River, showcase the role hospitalists can play in an ED scrambling to handle a triage scenario.

When the Airbus A320 and its 155 passengers crashed Jan. 15, New York and New Jersey hospitals braced for incoming patients. However, reports showed only a few dozen passengers were treated—the most serious for a fractured leg. Still, at Jersey City (N.J.) Medical Center (JCMC), eight victims brought to the ED meant half a dozen patients had to be discharged to make room.

"The hospitalists were involved only on the periphery this time, as we initially needed their approval to move patients out in anticipation of mass casualties," Douglas Ratner, MD, chairman and program director of JCMC's Department of Medicine, wrote in an e-mail. "They will be integral in future endeavors like this."

To that end, some hospitalists used the "Miracle on the Hudson" as a rallying cry for more training.

"How many of us have gone through rigorous teamwork training to learn to better communicate with our 'cabinmates' during times of stress? Remarkably few," Robert Wachter, MD, a hospitalist as well as a professor and associate chairman of the University of California at San Francisco’s department of medicine, wrote on his blog (the-hospitalist.org/blogs). "How often do we need to demonstrate our continued competency in our specialty? For most board-certified physicians, about every 10 years (up from 'never' 20 years ago). And how well do we learn from our errors? Well, never mind."

The Blog Rounds

Too busy rounding on patients to keep up with the blogosphere? We're doing the surfing for you in this first monthly roundup of what your colleagues are buzzing about in cyberspace.

First up: The Happy Hospitalist, who was not happy about Medco CEO Dave Snow's support of treatment protocols, had the following to say last week: "This guy doesn't get it. Cookbook medicine is but a tiny fraction of care. Perhaps 5% or less. I can admit a hemorrhagic stroke, follow standardized protocols, and the next 10 patients will have 10 different permutations of care. I can follow the guidelines to a T and every single patient's comorbid conditions will add layers upon layers of complication to the management."

On SHM's Hospitalist Leader blog, former SHM CEO Rusty Holman touched upon another frustration in the workplace: New hires who complain that "this isn't what I signed up for." Dr. Holman’s advice? When hiring explain that "the job you take today is likely— no, is certain— to be different a year from now." Dr. Holman assures practice managers that "as a leader, you will never be faulted for telling the truth."

Speaking of leaders, Health Beat's Maggie Mahar offered her thoughts on President Obama's inauguration speech: "When President Obama said, 'The time has come to put away childish things,' I couldn't help but recall healthcare reformer Don Berwick, sounding discouraged last winter, as he said, 'Maybe this country just isn't mature enough for healthcare reform.' Berwick, who is the president of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, was referring to the fact that at times, it seems that everyone wants healthcare for all— but no one wants to pay for it."

Too busy rounding on patients to keep up with the blogosphere? We're doing the surfing for you in this first monthly roundup of what your colleagues are buzzing about in cyberspace.

First up: The Happy Hospitalist, who was not happy about Medco CEO Dave Snow's support of treatment protocols, had the following to say last week: "This guy doesn't get it. Cookbook medicine is but a tiny fraction of care. Perhaps 5% or less. I can admit a hemorrhagic stroke, follow standardized protocols, and the next 10 patients will have 10 different permutations of care. I can follow the guidelines to a T and every single patient's comorbid conditions will add layers upon layers of complication to the management."

On SHM's Hospitalist Leader blog, former SHM CEO Rusty Holman touched upon another frustration in the workplace: New hires who complain that "this isn't what I signed up for." Dr. Holman’s advice? When hiring explain that "the job you take today is likely— no, is certain— to be different a year from now." Dr. Holman assures practice managers that "as a leader, you will never be faulted for telling the truth."

Speaking of leaders, Health Beat's Maggie Mahar offered her thoughts on President Obama's inauguration speech: "When President Obama said, 'The time has come to put away childish things,' I couldn't help but recall healthcare reformer Don Berwick, sounding discouraged last winter, as he said, 'Maybe this country just isn't mature enough for healthcare reform.' Berwick, who is the president of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, was referring to the fact that at times, it seems that everyone wants healthcare for all— but no one wants to pay for it."

Too busy rounding on patients to keep up with the blogosphere? We're doing the surfing for you in this first monthly roundup of what your colleagues are buzzing about in cyberspace.

First up: The Happy Hospitalist, who was not happy about Medco CEO Dave Snow's support of treatment protocols, had the following to say last week: "This guy doesn't get it. Cookbook medicine is but a tiny fraction of care. Perhaps 5% or less. I can admit a hemorrhagic stroke, follow standardized protocols, and the next 10 patients will have 10 different permutations of care. I can follow the guidelines to a T and every single patient's comorbid conditions will add layers upon layers of complication to the management."

On SHM's Hospitalist Leader blog, former SHM CEO Rusty Holman touched upon another frustration in the workplace: New hires who complain that "this isn't what I signed up for." Dr. Holman’s advice? When hiring explain that "the job you take today is likely— no, is certain— to be different a year from now." Dr. Holman assures practice managers that "as a leader, you will never be faulted for telling the truth."

Speaking of leaders, Health Beat's Maggie Mahar offered her thoughts on President Obama's inauguration speech: "When President Obama said, 'The time has come to put away childish things,' I couldn't help but recall healthcare reformer Don Berwick, sounding discouraged last winter, as he said, 'Maybe this country just isn't mature enough for healthcare reform.' Berwick, who is the president of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, was referring to the fact that at times, it seems that everyone wants healthcare for all— but no one wants to pay for it."

Onward and Upward

New data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) showing hospitalists number 23,000 and now practice in 4 out of 5 large hospitals drew the same response from doctors and administrators alike: We know.

"I don’t think a hospitalist program is optional," says Mark Larey, MD, vice president of medical affairs at St. Joseph's Mercy Health Center in Hot Springs, Ark. "In today’s environment, due to the regulatory issues, trying to improve patient satisfaction, trying to manage the increased unassigned population, it would be increasingly difficult to keep everything balanced … without a hospitalist service."

Dr. Larey's 309-bed hospital has a team of five internists and one nurse practitioner, and is adding a sixth full-time position this fall to absorb increased stress on the emergency department. The situation is typical of the exponential growth of the industry since it started in 1996 with as few as 500 hospitalists, says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of SHM.

In many hospitals, hospital medicine has become a quality-care necessity—one that increases satisfaction scores, trims length of stay, and increases emergency-room throughputs, Dr. Wellikson says. AHA figures culled from the 2007 survey of nearly 5,000 community hospitals show that at hospitals with 200 or more beds, 83% have hospital medicine programs. SHM estimates the current hospitalist workforce at 29,000.

"It took emergency medicine 25, 30 years to get to the point hospital medicine got to in 10 years," Dr. Wellikson says. "It’s the growth of a specialty on steroids."

For more information, visit http://www.aha.org/aha/research-and-trends/health-and-hospital-trends/2008.html.

New data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) showing hospitalists number 23,000 and now practice in 4 out of 5 large hospitals drew the same response from doctors and administrators alike: We know.

"I don’t think a hospitalist program is optional," says Mark Larey, MD, vice president of medical affairs at St. Joseph's Mercy Health Center in Hot Springs, Ark. "In today’s environment, due to the regulatory issues, trying to improve patient satisfaction, trying to manage the increased unassigned population, it would be increasingly difficult to keep everything balanced … without a hospitalist service."

Dr. Larey's 309-bed hospital has a team of five internists and one nurse practitioner, and is adding a sixth full-time position this fall to absorb increased stress on the emergency department. The situation is typical of the exponential growth of the industry since it started in 1996 with as few as 500 hospitalists, says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of SHM.

In many hospitals, hospital medicine has become a quality-care necessity—one that increases satisfaction scores, trims length of stay, and increases emergency-room throughputs, Dr. Wellikson says. AHA figures culled from the 2007 survey of nearly 5,000 community hospitals show that at hospitals with 200 or more beds, 83% have hospital medicine programs. SHM estimates the current hospitalist workforce at 29,000.

"It took emergency medicine 25, 30 years to get to the point hospital medicine got to in 10 years," Dr. Wellikson says. "It’s the growth of a specialty on steroids."

For more information, visit http://www.aha.org/aha/research-and-trends/health-and-hospital-trends/2008.html.

New data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) showing hospitalists number 23,000 and now practice in 4 out of 5 large hospitals drew the same response from doctors and administrators alike: We know.

"I don’t think a hospitalist program is optional," says Mark Larey, MD, vice president of medical affairs at St. Joseph's Mercy Health Center in Hot Springs, Ark. "In today’s environment, due to the regulatory issues, trying to improve patient satisfaction, trying to manage the increased unassigned population, it would be increasingly difficult to keep everything balanced … without a hospitalist service."

Dr. Larey's 309-bed hospital has a team of five internists and one nurse practitioner, and is adding a sixth full-time position this fall to absorb increased stress on the emergency department. The situation is typical of the exponential growth of the industry since it started in 1996 with as few as 500 hospitalists, says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of SHM.

In many hospitals, hospital medicine has become a quality-care necessity—one that increases satisfaction scores, trims length of stay, and increases emergency-room throughputs, Dr. Wellikson says. AHA figures culled from the 2007 survey of nearly 5,000 community hospitals show that at hospitals with 200 or more beds, 83% have hospital medicine programs. SHM estimates the current hospitalist workforce at 29,000.

"It took emergency medicine 25, 30 years to get to the point hospital medicine got to in 10 years," Dr. Wellikson says. "It’s the growth of a specialty on steroids."

For more information, visit http://www.aha.org/aha/research-and-trends/health-and-hospital-trends/2008.html.

Research Roundup

Question: Can a D-dimer level assess the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) after a course of anticoagulation therapy has been completed?

Background: The duration of anticoagulation therapy for first unprovoked VTE is uncertain. Identifying risk of recurrent VTE will help clinicians make decisions on optimal duration of anticoagulation.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Patients who have completed therapy for an episode of VTE without known risks.

Synopsis: Seven high-quality studies totaling 1,888 patients with first unprovoked VTE were analyzed. All patients received standardized therapy for at least three months with warfarin (Coumadin). A D-dimer had been checked in all patients between three and six weeks after stopping anticoagulation. The annual rate of VTE recurrence among patients with a positive D-dimer result was 8.9% (confidence interval (CI), 5.8% to 11.9%) compared with 3.5% (CI, 2.7 to 4.3%) for those with a negative result.

False-positive or false-negative D-dimer results could have occurred due to the heterogeneity in duration of anticoagulation and timing of D-dimer testing among the various studies. Since none of the studies were blinded to a history of VTE, there is potential for outcome ascertainment bias due to studying a sample deemed susceptible to disease recurrence.

Bottom line: D-dimer testing holds promise in identifying risk of VTE recurrence and could aid therapeutic decision-making regarding duration of anticoagulation.

Citation: Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:481-490

–Reviewed for the eWire by Rebecca Allyn, MD, Smitha Chadaga, MD, Mary Dedecker, MD, Vignesh Narayanan, MD, Eugene S. Chu, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Denver Health and Hospital Authority

Question: Can a D-dimer level assess the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) after a course of anticoagulation therapy has been completed?

Background: The duration of anticoagulation therapy for first unprovoked VTE is uncertain. Identifying risk of recurrent VTE will help clinicians make decisions on optimal duration of anticoagulation.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Patients who have completed therapy for an episode of VTE without known risks.

Synopsis: Seven high-quality studies totaling 1,888 patients with first unprovoked VTE were analyzed. All patients received standardized therapy for at least three months with warfarin (Coumadin). A D-dimer had been checked in all patients between three and six weeks after stopping anticoagulation. The annual rate of VTE recurrence among patients with a positive D-dimer result was 8.9% (confidence interval (CI), 5.8% to 11.9%) compared with 3.5% (CI, 2.7 to 4.3%) for those with a negative result.

False-positive or false-negative D-dimer results could have occurred due to the heterogeneity in duration of anticoagulation and timing of D-dimer testing among the various studies. Since none of the studies were blinded to a history of VTE, there is potential for outcome ascertainment bias due to studying a sample deemed susceptible to disease recurrence.

Bottom line: D-dimer testing holds promise in identifying risk of VTE recurrence and could aid therapeutic decision-making regarding duration of anticoagulation.

Citation: Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:481-490

–Reviewed for the eWire by Rebecca Allyn, MD, Smitha Chadaga, MD, Mary Dedecker, MD, Vignesh Narayanan, MD, Eugene S. Chu, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Denver Health and Hospital Authority

Question: Can a D-dimer level assess the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) after a course of anticoagulation therapy has been completed?

Background: The duration of anticoagulation therapy for first unprovoked VTE is uncertain. Identifying risk of recurrent VTE will help clinicians make decisions on optimal duration of anticoagulation.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Patients who have completed therapy for an episode of VTE without known risks.

Synopsis: Seven high-quality studies totaling 1,888 patients with first unprovoked VTE were analyzed. All patients received standardized therapy for at least three months with warfarin (Coumadin). A D-dimer had been checked in all patients between three and six weeks after stopping anticoagulation. The annual rate of VTE recurrence among patients with a positive D-dimer result was 8.9% (confidence interval (CI), 5.8% to 11.9%) compared with 3.5% (CI, 2.7 to 4.3%) for those with a negative result.

False-positive or false-negative D-dimer results could have occurred due to the heterogeneity in duration of anticoagulation and timing of D-dimer testing among the various studies. Since none of the studies were blinded to a history of VTE, there is potential for outcome ascertainment bias due to studying a sample deemed susceptible to disease recurrence.

Bottom line: D-dimer testing holds promise in identifying risk of VTE recurrence and could aid therapeutic decision-making regarding duration of anticoagulation.

Citation: Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:481-490

–Reviewed for the eWire by Rebecca Allyn, MD, Smitha Chadaga, MD, Mary Dedecker, MD, Vignesh Narayanan, MD, Eugene S. Chu, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Denver Health and Hospital Authority

CPR for EHRs

The truth about EHR systems is that their implementation is never easy. It's a lot of work. It takes time and money, and despite the best laid plans there will be trauma and frustration. So expecting problems to arise is key to keeping perspective.

When our office implemented an electronic health records system in 2000, our system crashed 25–75 times a day for 5 months, and we lost patient data each time. I repeat: We lost patient data each time. Extensive troubleshooting ensued. Ceiling tiles were ripped out to see if the fluorescent lights were interfering with the network cables, a consultant was brought in, and our server and network were reinstalled. Finally, the cause of the crashes was determined to be a bug in our Microsoft program. As nightmarish as this situation was, I would say that such technology challenges were nothing compared to challenges in managing processes and people.

From a process perspective, a common mistake involves attempting to make the EHR system conform to what is done with paper. The whole point is to imagine a process that can help your office save time and money instead of mirroring what you did for years with a paper-based system.

Staff challenges are by far the toughest ones to manage because they require changing the minds and habits of individuals who don't feel comfortable giving up paper-based processes. Persistent naysayers can sabotage EHR implementation by convincing others that the changes cannot be made. Over the years, four of five staff members have left. When new staff members were hired, we emphasized the fact that our office was computerized and those individuals have successfully adapted to a paperless system. Among the lessons we've learned over the years are these:

▸ Don't skimp on training. When you're spending thousands of dollars on an EHR system it's tempting to shave costs and training may appear to be part of the discretionary spending budget. But giving training short shrift can cost you a lot more than you saved in the long run.

Even if you're the most technologically savvy physician, avoid the “I can do it all” mentality. Your time is best spent seeing patients and making money. Make sure that others are well trained so you feel comfortable delegating EHR responsibilities.

▸ Train the Luddites last. Once you've worked out all the kinks in the training process with those who are most comfortable using computers, it'll go a lot more smoothly for those who are less tech-savvy. Don't let anyone opt out of training. That can cost tens of thousands of dollars in the long run.

▸ Include everyone in brainstorming sessions. While no one likes meetings, get everyone involved in implementation meetings, not just the doctors and the office manager, because you will get good ideas from everyone. In addition, if they are involved in the brainstorming sessions, they are far more likely to adopt new behaviors.

▸ It doesn't have to be perfect. During the transition phase to an EHR system, there's a temptation to try to make everything perfect. Soon after we went live with our system, I spent a lot of time checking electronic charts to make sure the staff had included consultation notes. It was really a wasted step, because 99% of the time they had done it. In the rare event that the notes don't get into the chart, it doesn't affect patient care. The key is knowing when to accept a process as good enough and move on.

▸ Get a leader. You need a leader with a vision to organize the troubleshooting, both to build support and to keep everyone on track. The most common cause of EHR failure is lack of a leader.

The truth about EHR systems is that their implementation is never easy. It's a lot of work. It takes time and money, and despite the best laid plans there will be trauma and frustration. So expecting problems to arise is key to keeping perspective.

When our office implemented an electronic health records system in 2000, our system crashed 25–75 times a day for 5 months, and we lost patient data each time. I repeat: We lost patient data each time. Extensive troubleshooting ensued. Ceiling tiles were ripped out to see if the fluorescent lights were interfering with the network cables, a consultant was brought in, and our server and network were reinstalled. Finally, the cause of the crashes was determined to be a bug in our Microsoft program. As nightmarish as this situation was, I would say that such technology challenges were nothing compared to challenges in managing processes and people.

From a process perspective, a common mistake involves attempting to make the EHR system conform to what is done with paper. The whole point is to imagine a process that can help your office save time and money instead of mirroring what you did for years with a paper-based system.

Staff challenges are by far the toughest ones to manage because they require changing the minds and habits of individuals who don't feel comfortable giving up paper-based processes. Persistent naysayers can sabotage EHR implementation by convincing others that the changes cannot be made. Over the years, four of five staff members have left. When new staff members were hired, we emphasized the fact that our office was computerized and those individuals have successfully adapted to a paperless system. Among the lessons we've learned over the years are these:

▸ Don't skimp on training. When you're spending thousands of dollars on an EHR system it's tempting to shave costs and training may appear to be part of the discretionary spending budget. But giving training short shrift can cost you a lot more than you saved in the long run.

Even if you're the most technologically savvy physician, avoid the “I can do it all” mentality. Your time is best spent seeing patients and making money. Make sure that others are well trained so you feel comfortable delegating EHR responsibilities.

▸ Train the Luddites last. Once you've worked out all the kinks in the training process with those who are most comfortable using computers, it'll go a lot more smoothly for those who are less tech-savvy. Don't let anyone opt out of training. That can cost tens of thousands of dollars in the long run.

▸ Include everyone in brainstorming sessions. While no one likes meetings, get everyone involved in implementation meetings, not just the doctors and the office manager, because you will get good ideas from everyone. In addition, if they are involved in the brainstorming sessions, they are far more likely to adopt new behaviors.

▸ It doesn't have to be perfect. During the transition phase to an EHR system, there's a temptation to try to make everything perfect. Soon after we went live with our system, I spent a lot of time checking electronic charts to make sure the staff had included consultation notes. It was really a wasted step, because 99% of the time they had done it. In the rare event that the notes don't get into the chart, it doesn't affect patient care. The key is knowing when to accept a process as good enough and move on.

▸ Get a leader. You need a leader with a vision to organize the troubleshooting, both to build support and to keep everyone on track. The most common cause of EHR failure is lack of a leader.

The truth about EHR systems is that their implementation is never easy. It's a lot of work. It takes time and money, and despite the best laid plans there will be trauma and frustration. So expecting problems to arise is key to keeping perspective.

When our office implemented an electronic health records system in 2000, our system crashed 25–75 times a day for 5 months, and we lost patient data each time. I repeat: We lost patient data each time. Extensive troubleshooting ensued. Ceiling tiles were ripped out to see if the fluorescent lights were interfering with the network cables, a consultant was brought in, and our server and network were reinstalled. Finally, the cause of the crashes was determined to be a bug in our Microsoft program. As nightmarish as this situation was, I would say that such technology challenges were nothing compared to challenges in managing processes and people.

From a process perspective, a common mistake involves attempting to make the EHR system conform to what is done with paper. The whole point is to imagine a process that can help your office save time and money instead of mirroring what you did for years with a paper-based system.

Staff challenges are by far the toughest ones to manage because they require changing the minds and habits of individuals who don't feel comfortable giving up paper-based processes. Persistent naysayers can sabotage EHR implementation by convincing others that the changes cannot be made. Over the years, four of five staff members have left. When new staff members were hired, we emphasized the fact that our office was computerized and those individuals have successfully adapted to a paperless system. Among the lessons we've learned over the years are these:

▸ Don't skimp on training. When you're spending thousands of dollars on an EHR system it's tempting to shave costs and training may appear to be part of the discretionary spending budget. But giving training short shrift can cost you a lot more than you saved in the long run.

Even if you're the most technologically savvy physician, avoid the “I can do it all” mentality. Your time is best spent seeing patients and making money. Make sure that others are well trained so you feel comfortable delegating EHR responsibilities.

▸ Train the Luddites last. Once you've worked out all the kinks in the training process with those who are most comfortable using computers, it'll go a lot more smoothly for those who are less tech-savvy. Don't let anyone opt out of training. That can cost tens of thousands of dollars in the long run.

▸ Include everyone in brainstorming sessions. While no one likes meetings, get everyone involved in implementation meetings, not just the doctors and the office manager, because you will get good ideas from everyone. In addition, if they are involved in the brainstorming sessions, they are far more likely to adopt new behaviors.

▸ It doesn't have to be perfect. During the transition phase to an EHR system, there's a temptation to try to make everything perfect. Soon after we went live with our system, I spent a lot of time checking electronic charts to make sure the staff had included consultation notes. It was really a wasted step, because 99% of the time they had done it. In the rare event that the notes don't get into the chart, it doesn't affect patient care. The key is knowing when to accept a process as good enough and move on.

▸ Get a leader. You need a leader with a vision to organize the troubleshooting, both to build support and to keep everyone on track. The most common cause of EHR failure is lack of a leader.

A New Revenue Source?

A recently expanded palliative care program at University Hospital in Salt Lake City is the latest window into ancillary revenue streams hospitalists can tap during the continuing economic crisis.

Stephen Bekanich, MD, a hospitalist and medical director of the Utah center's palliative-care team, says his program saves money for the hospital and increases the value of its hospitalists. In October, Dr. Bekanich's team expanded into outpatient clinic treatment one half-day a week. While he plans to study the revenue generated through that month before expanding further, Dr. Bekanich thinks palliative-care teams are a strong revenue source for hospitalists.