User login

Conflicting Measures of Hospital Quality / Halasyamani and Davis

National concerns about the quality of health care in the United States have prompted calls for transparent efforts to measure and report hospital performance to the public. Consumer groups, payers, and credentialing organizations now rate the quality of hospitals and health care through a variety of mechanisms, yielding a kaleidoscope of quality measurement scorecards. However, health care consumers have minimal information about how hospital quality rating systems compare with each other or which rating system might best address their information needs.

The Hospital Compare Web site was launched in April 2005 by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA), a public‐private collaboration among organizations, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The CMS describes Hospital Compare as information [that] measures how well hospitals care for their patients.1 A limited set of Hospital Compare data from 2004 were posted online in 2005 for more than 4200 hospitals, permitting community‐specific comparisons of hospitals' self‐reported standardized core measures that reflect quality of care for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure (CHF), and community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) in adult patients.

Other current hospital quality evaluation tools target payers and purchasers of health care. However, many of these evaluations require that institutions pay a fee for submitting their data to be benchmarked against other participating institutions or require that the requesting individual or organization pay a fee to examine a hospital's performance on a specific condition or procedure.

We examined Hospital Compare data alongside that of another hospital rating system that has existed for a longer period of time and is likely better known to the lay publicthe Best Hospitals lists published annually by U.S. News and World Report.2, 3 Together, Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals are hospital quality scorecards that offer consumers assessments of hospital performance on a national scale. However, their measures of hospital quality differ, and we investigated whether they would provide consumers with concordant assessments of hospital quality.

METHODS

Data Sources

Hospital Compare

Core measure performance data were obtained by the investigators from the Hospital Compare Web site.3 Information in the database was provided by hospitals for the period January‐June 2004. Hospitals self‐reported their performance on the core measures using standardized medical record abstraction programs. The measures reported are cumulative averages based on monthly performance summaries.

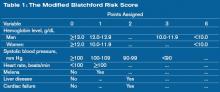

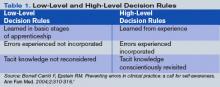

Fourteen core measures were used in the study to form 3 core measure sets (Table 1): the AMI set comprised 6 measures, the CHF set comprised 4 measures, and the CAP site comprised 4 measures. Of the 17 core measures available on the Hospital Compare Web site, core measures of timing of thrombolytic agents or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for patients with AMI were excluded from the analysis because fewer than 10% of institutions reported such measures. Data on the core measure about oxygenation measurement for CAP were also excluded because of minimal variation between hospitals (national mean = 98%; the national mean for all other measures was less than 92%).3

| Condition | Core Measures |

|---|---|

| |

| Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) |

|

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) |

|

| Community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) |

|

Core measures that CMS defined as having too few cases (< 25) to reliably ascertain an estimate of hospital performance, or for which hospitals were not reporting data, were not eligible for analysis. To generate a composite score for each of the disease‐specific core measure sets, scores for all eligible core measures within each set were summed and then divided by the number of eligible measures available. This permitted standardization of the scores in the majority of instances when institutions did not report all eligible measures within a given set.

Best Hospitals

Ratings of hospitals were drawn from the 2004 and 2005 editions of the Best Hospitals listings of the U.S. News and World Report, the editions that most closely reflect performance data and physician survey data concurrent with Hospital Compare data analyzed for this study.4 In each year, ratings were developed for more than 2000 hospitals that met specific criteria related to teaching hospital status, medical school affiliation, or availability of specific technology‐related services.5 The Best Hospitals rating system is based on 3 central elements of evaluation: (a) reputation, judged by responses to a national mail survey of physicians asked to list the 5 hospitals best in their specialty for difficult cases, without economic or geographic considerations; (b) in‐hospital mortality rates for Medicare patients, adjusted for severity of illness; and (c) a combination of other factors, such as the nurse‐to‐patient ratio and the number of a set of predetermined key technologies available, as determined from institutions' responses to the American Hospital Association's annual survey.5

The 50 Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery, 50 Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders, and all Honor Roll hospitals (as determined by breadth of institutional excellence, with top performance in 6 or more of 17 specialties) named in 2004 and 2005 were included in this study, except that National Jewish Medical and Research Center was listed as a Best Hospital for respiratory disorders in both years but did not report sufficient numbers of cases to have eligible core measures in Hospital Compare. Of note, there were 11 institutions newly listed as Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery and 10 institutions newly listed as Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders in 2005 versus 2004; 14 hospitals made the Best Hospitals Honor Roll in 2004, and 2 others were added for 2005.

Data Analysis

To examine the internal validity of the Hospital Compare measures, we calculated pairwise correlation coefficients among the 14 core‐measure components, using all eligible data points. We then calculated Cronbach's , a measure of the internal consistency of scales of measures, to characterize each of the sets of Hospital Compare core measures separately (AMI, CHF, CAP). We also generated Cronbach's for a measure we called the combined core‐measures score, which we intended to be analogous to the Best Hospitals Honor Roll, defined as the AMI, CHF, and CAP measure sets scored together.

To compare Hospital Compare data with the Best Hospitals rankings (for heart and heart surgery, respiratory disorders, and the Honor Roll), we first established national quartile score cut points for each of the 3 Hospital Compare core measure sets and for the combined core measures, using all U.S. hospitals eligible for our analysis. We used quartiles to avoid the misclassification that would be more likely to occur with deciles (based on confidence intervals for the core measures provided by CMS).6

We calculated Hospital Compare scores for each institution listed as a Best Hospital in 2004 and 2005 and classified the Best Hospitals into scoring quartiles based on national score cut points (eg, if the national cutoff for AMI core measures for the top quartile was 95.2%, then a Best Hospital with an AMI score for the core‐measures set 95.2% was classified in the first [top] quartile). AMI and CHF core measure sets were used for comparison with the Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery, the CAP core‐measure set was used for comparison with the Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders, and the combined core‐measure set was used for comparison with the Honor Roll hospitals.

Sensitivity Analyses

To investigate the effect of missing Hospital Compare data on our study findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses. We used only those institutions with complete data for the AMI, CHF, and CAP core measure sets to establish new quartile cut points and then reexamined the quartile distribution for institutions in the corresponding Best Hospitals lists. We also compared the Best Hospitals' Hospital Compare data completeness with that of all Hospital Compare institutions.

RESULTS

Core Performance Measures in Hospital Compare

Of 4203 hospitals that submitted core measures as part of Hospital Compare, 4126 had at least 1 core measure eligible for analysis (> 25 observations). Of these 4126 hospitals, 2165 (52.5%) had at least 1 eligible AMI core measure, and 398 (9.7%) had all 6 measures eligible for analysis; 3130 had at least 1 eligible CHF core measure (75.9%), and 289 (7.0%) had all 4 measures eligible for analysis; and 3462 (83.9%) had at least one eligible CAP core measure and 302 (7.3%) had all 4 measures eligible for analysis. For the combined core‐measure score, 2119 (51.4%) had at least 4 eligible measures, and 120 (2.9%) had all 14 measures eligible for analysis.

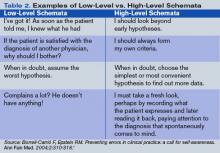

Pairwise correlation coefficients within each of the disease‐specific core measure sets was highest for the AMI measures, and was generally higher for measures that reflected similar clinical activities (eg, aspirin and ‐blocker at discharge for AMI care; tobacco cessation counseling for AMI, CHF, and CAP; Table 2). In general, the AMI and CHF performance measures correlated more strongly with each other than did the AMI or CHF measures with the CAP measures.

Internal consistency within each of the disease‐specific measures was moderate to strong, with Cronbach's = .83 for AMI, Cronbach's = .58 for CHF, and Cronbach's = .49 for CAP. For the combined performance measure set (all 14 core measures together), Cronbach's = .74.

Hospital Compare Scores for Institutions Listed as Best Hospitals

Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery and for respiratory disorders in U.S. News and World Report in 2004 and 2005 exhibited a broad distribution of Hospital Compare core measure scores (Table 3). For none of the core measure sets did a majority of Best Hospitals score in the top quartile in either year.

| Hospital Compare Scores | Best Hospitals for Heart Disease: AMI Core Measures (n = 50 hospitals)* | Best Hospitals for Heart Disease: CHF Core Measures (n = 50 hospitals)* | Best Hospitals for Respiratory Disorders: CAP Core Measures (n = 49 hospitals)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 2004 | 2005 | 2004 | 2005 | 2004 | 2005 | |

| First quartile | 20 (40%) | 15 (30%) | 19 (38%) | 19 (38%) | 5 (10%) | 7 (14%) |

| Second quartile | 16 (32%) | 21 (42%) | 14 (28%) | 15 (30%) | 8 (16%) | 6 (12%) |

| Third quartile | 11 (22%) | 10 (20%) | 11 (22%) | 12 (24%) | 13 (27%) | 15 (31%) |

| Fourth quartile | 3 (6%) | 4 (8%) | 6 (12%) | 4 (8%) | 23 (47%) | 21 (43%) |

Among the 50 hospitals identified as best for cardiac care, only 20 (40%) in the 2004 list and 15 (30%) in the 2005 list had AMI core‐measure scores in the top quartile nationally, and 14 (28%) scored below the national median in both years. Among those same 50 hospitals, only 19 (38%) had CHF core‐measure scores in the top quartile nationally in both years, whereas 17 (34%) scored below the national median in 2004 and 16 in 2005. On the CAP core measures, Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders generally scored poorly, with only 5 (10%) from the 2004 list and 7 (14%) from the 2005 list in the top quartile nationally and nearly half the institutions scoring in the bottom national quartile (Table 3).

For the 14 hospitals named to the 2004 Honor Roll of Best Hospitals, the comparison with the combined core‐measure score (AMI, CHF, and CAP together) revealed a similarly broad distribution of core measure performance. Only five hospitals scored in the top quartile, 2 in the second quartile, 5 in the third quartile, and 2 in the bottom quartile. The distribution for hospitals in the 2005 Honor Roll was similar (5‐3‐6‐2 by quartile).

Sensitivity Analyses

National quartile Hospital Compare core‐measure cut points were slightly lower (1%‐2% in absolute terms) for those institutions with complete data than for institutions overall; in other words, institutions reporting on all 17 measures were generally more likely to have somewhat lower scores. These differences were substantive enough to shift the distribution of Best Hospitals in 2004 and 2005 up to higher quartiles for the AMI and CHF Hospital Compare measures but not for the CAP measures. For example, using the complete data AMI cut points, 23 of the 50 Best Hospitals for cardiac care in 2005 scored in the top quartile, 16 in the second quartile, 6 in the third quartile, and 5 in the bottom quartile (compared with 15‐21‐10‐4; Table 3). With complete data CHF cut points, the distribution was 26, 11, 9, and 4 for the 2005 Best Hospitals for cardiac care from the top through bottom quartiles, respectively (compared with 19‐15‐12‐4; Table 3). Results for 2004 sensitivity analyses were similar.

Institutions named as Best Hospitals appeared more likely than institutions overall to have complete Hospital Compare data. Whereas fewer than 10% of institutions in Hospital Compare had complete data for the AMI, CHF, and CAP core measures, 60% of Best Hospitals for cardiac care in 2005 had complete data for AMI measures and 44% for CHF measures, whereas 32% of Best Hospitals for respiratory care had complete CAP data.

DISCUSSION

With the public release of Hospital Compare data for more than 4200 hospitals in April 2005, national efforts to report hospital quality to the public passed a major milestone. Our findings indicate that the separate Hospital Compare measures for AMI, CHF, and CAP care have moderate to strong internal consistency, which suggests they are capturing similar hospital‐level care behaviors across institutions for these 3 common conditions.

However, Hospital Compare scores are largely discordant with the Best Hospital rank lists for cardiac and respiratory disorders care. Several institutions listed as Best Hospitals nationally scored below the national median on disease‐specific Hospital Compare core measures, perhaps leaving data‐conscious consumers to wonder how to synthesize rating systems that employ different indicators and measure different aspects of health care delivery.

Lack of Agreement in Hospital Quality Measurement

Discordance between the Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals rating systems is not all that surprising, given that their methods of institutional assessment differ markedly. Although both approaches share the goal of allowing consumers a comparative look at institutional performance nationally, they clearly measure different aspects of hospital care.

Hospital Compare measures focus on the delivery of disease‐specific, evidence‐based practices for 3 acute medical conditions from the emergency department to discharge. In comparison, the Best Hospitals rankings emphasize the reputation and mortality data of hospitals and health systems across a variety of general and subspecialty care settings (including several in which core quality measures have not yet been developed), combined with factors related to nursing and technology availability that may also influence consumers' choices. Of note, the Best Hospitals rating approach has been criticized in the past for its strong reliance on physicians' ratings of institutional reputation, which may have little to do with functional measures of quality.7

In essence, the Hospital Compare measures indicate how hospitals perform for an average case, while Best Hospitals relies on reputation and focus on mortality to indicate how institutions perform on the toughest cases. The question at hand is: are these institutional quality measures complementary or contradictory? Our findings suggest that Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals measures offer consumers a mix of complementary and contradictory information, depending on the institution.

The ratings systems differ in other respects as well. In Hospital Compare, performance data are available for more than 4000 hospitals, which permits consumers to examine their local institutions, whereas the Best Hospitals lists offer information only on the top performers. On the other hand, the more established Best Hospitals listings have been published annually for the last 15 years,5 permitting some longitudinal evaluation of hospitals' quality consistency. Importantly, neither rating system includes measures of patient satisfaction with hospital care.

One dimension that both rating systems share is the migration of quality measurement from the local and institutional level to the national stage. Historically, health care quality measurement has been a local phenomenon, as institutions work to gain larger shares of their local markets. A few hospitals have marketed their care and services regionally or even nationally and internationally, but these institutionswhich previously primarily used their reputation rather than specific outcome metrics to reach beyond their local communitiesare a minority of U.S. hospitals.

Although Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals are both national in scope, only Hospital Compare allows consumers to understand the quality of care in most of their community hospitals and health systems. Other investigators analyzing the same data set have highlighted significant differences in hospital performance according to for‐profit status, academic status, and size (number of beds).8

However, it is not yet clear if and how hospital ratings influence consumers' health care decisions. In fact, some studies suggest that only a minority of patients are inclined to use performance reports in their decisions about health care.9, 10 Moreover, if illness is acute, the factors driving choice of hospital may be geographic proximity, bed availability, and payer contracts rather than performance measures.

These constraints on the utility of hospital quality metrics from the consumer perspective are reminders that such metrics may have other benefits. Specifically, ratings such as Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals, as well as others such as those of the Leapfrog Group11 and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations,12 offer differing arrays of performance measures that may induce hospitals to improve their quality of care.1, 13 Institutions that score well or improve their scores over time can use such scores not only to benchmark their processes and outcomes but also to signal the comparative value of their care to the public. In the past, hospitals named to the Best Hospitals Honor Roll have trumpeted their achievements through plaques on their walls and in advertisements for their services. Whether institutions will do the same regarding their Hospital Compare scores remains to be seen.

Study Limitations

The chief limitation of this analysis is that not all hospitals reported data for the Hospital Compare core measures. We standardized the core‐measure sets for AMI, CHF, and CAP care for the number of measures reported in each set in order to include as many hospitals as possible in our analyses. Participation in Hospital Compare is voluntary (although strongly encouraged because of better Medicare reimbursement for institutions that participate), so it is possible that there was a systematic scoring bias in hospitals' incomplete reporting across all measures, that is, hospitals might not report specific core measure scores if they were particularly poor.13 That scale score medians were slightly lower for hospitals with complete data than for hospitals overall may indicate some reporting bias in the Hospital Compare data. Nevertheless, in the sensitivity analyses we performed using only those hospitals with complete data on the Hospital Compare core measures, comparisons with the Best Hospitals lists still predominantly indicated discordance between the rating systems.

Another limitation of this work is that we examined only 2 of several currently available hospital‐rating schemes. We chose to examine Hospital Compare because it is the first governmental effort to report specific hospital quality measures to the public, and we elected to look at Hospital Compare alongside the Best Hospitals lists because the latter are arguably the hospital ratings best known to the lay public.

A third potential limitation is that the Best Hospitals lists for 2004 were based in part on mortality figures and hospital survey data from 2002, which were the most recent data available at the time of the rankings; for the 2005 Best Hospitals lists, the most recent mortality and hospital survey data were collected in 2003.4 Hospital Compare scores were calculated on the basis of patients discharged in 2004, and therefore the ratings systems reflect somewhat different time frames. Nonetheless, we do not believe that this mismatch explains the extent of discordance between the 2 rating scales, particularly because there was such stability in the Best Hospital lists over the 2 years.

CONCLUSIONS

The Best Hospitals lists and Hospital Compare core measure scores agree only a minority of the time on the best institutions for the care of cardiac and respiratory conditions in the United States. Prominent, publicly reported hospital quality scorecards that paint discordant pictures of institutional performance potentially present a conundrum for physicians, patients, and payers with growing incentives to compare institutional quality.

If the movement to improve health care quality is to succeed, the challenge will be to harness the growing professional and lay interest in quality measurement to create rating scales that reflect the best aspects of Hospital Compare and the Best Hospitals lists, with the broadest inclusion of institutions and scope of conditions. For example, it would be more helpful to the public if the Best Hospitals lists included available Hospital Compare measures. It would also benefit consumers if Hospital Compare included more metrics about preventive and elective procedures, domains in which consumers can maximally exercise their choice of health care institutions. Moreover, voluntary reporting may constrain the quality effort. Only with mandatory reporting on quality measures will consistent and sufficient institutional accountability be achieved.

- .Public performance reports and the will for change.JAMA.2002;288:1523–1524.

- .Improving the quality of care—can we practice what we preach?N Engl J Med.2003;348:2681–2683.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Accessed May 12,2005.

- U.S. News and World Report. Best hospitals 2005. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/usnews/health/best‐hospitals/tophosp.htm. Accessed July 10,2005.

- . Best hospitals 2005: methodology behind the rankings. U.S. News and World Report. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/usnews/health/best‐hospitals/methodology.htm. Accessed July 10,2005.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare: information for professionals. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/Hospital/Static/Data‐Professionals.asp?dest=NAV|Home|DataDetails|ProfessionalInfo#TabTop. Accessed May 12,2005.

- ,,,.In search of America's best hospitals: the promise and reality of quality assessment.JAMA.1997;277:1152–1155.

- ,,,.Care in US hospitals—the Hospital Quality Alliance program.N Engl Jour Med.2005;353:265–274.

- ,.Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery.JAMA.1998;279:1638–1642.

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.National Survey on Consumers' Experiences with Patient Safety and Quality Information.Washington, DC:Kaiser Family Foundation;2004.

- Leapfrog Group for Patient Safety. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org. Accessed May 12,2005.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Quality check. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/quality+check/index.htm. Accessed May 12,2005.

- ,.The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information.JAMA.2005;293:1239–1244.

National concerns about the quality of health care in the United States have prompted calls for transparent efforts to measure and report hospital performance to the public. Consumer groups, payers, and credentialing organizations now rate the quality of hospitals and health care through a variety of mechanisms, yielding a kaleidoscope of quality measurement scorecards. However, health care consumers have minimal information about how hospital quality rating systems compare with each other or which rating system might best address their information needs.

The Hospital Compare Web site was launched in April 2005 by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA), a public‐private collaboration among organizations, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The CMS describes Hospital Compare as information [that] measures how well hospitals care for their patients.1 A limited set of Hospital Compare data from 2004 were posted online in 2005 for more than 4200 hospitals, permitting community‐specific comparisons of hospitals' self‐reported standardized core measures that reflect quality of care for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure (CHF), and community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) in adult patients.

Other current hospital quality evaluation tools target payers and purchasers of health care. However, many of these evaluations require that institutions pay a fee for submitting their data to be benchmarked against other participating institutions or require that the requesting individual or organization pay a fee to examine a hospital's performance on a specific condition or procedure.

We examined Hospital Compare data alongside that of another hospital rating system that has existed for a longer period of time and is likely better known to the lay publicthe Best Hospitals lists published annually by U.S. News and World Report.2, 3 Together, Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals are hospital quality scorecards that offer consumers assessments of hospital performance on a national scale. However, their measures of hospital quality differ, and we investigated whether they would provide consumers with concordant assessments of hospital quality.

METHODS

Data Sources

Hospital Compare

Core measure performance data were obtained by the investigators from the Hospital Compare Web site.3 Information in the database was provided by hospitals for the period January‐June 2004. Hospitals self‐reported their performance on the core measures using standardized medical record abstraction programs. The measures reported are cumulative averages based on monthly performance summaries.

Fourteen core measures were used in the study to form 3 core measure sets (Table 1): the AMI set comprised 6 measures, the CHF set comprised 4 measures, and the CAP site comprised 4 measures. Of the 17 core measures available on the Hospital Compare Web site, core measures of timing of thrombolytic agents or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for patients with AMI were excluded from the analysis because fewer than 10% of institutions reported such measures. Data on the core measure about oxygenation measurement for CAP were also excluded because of minimal variation between hospitals (national mean = 98%; the national mean for all other measures was less than 92%).3

| Condition | Core Measures |

|---|---|

| |

| Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) |

|

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) |

|

| Community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) |

|

Core measures that CMS defined as having too few cases (< 25) to reliably ascertain an estimate of hospital performance, or for which hospitals were not reporting data, were not eligible for analysis. To generate a composite score for each of the disease‐specific core measure sets, scores for all eligible core measures within each set were summed and then divided by the number of eligible measures available. This permitted standardization of the scores in the majority of instances when institutions did not report all eligible measures within a given set.

Best Hospitals

Ratings of hospitals were drawn from the 2004 and 2005 editions of the Best Hospitals listings of the U.S. News and World Report, the editions that most closely reflect performance data and physician survey data concurrent with Hospital Compare data analyzed for this study.4 In each year, ratings were developed for more than 2000 hospitals that met specific criteria related to teaching hospital status, medical school affiliation, or availability of specific technology‐related services.5 The Best Hospitals rating system is based on 3 central elements of evaluation: (a) reputation, judged by responses to a national mail survey of physicians asked to list the 5 hospitals best in their specialty for difficult cases, without economic or geographic considerations; (b) in‐hospital mortality rates for Medicare patients, adjusted for severity of illness; and (c) a combination of other factors, such as the nurse‐to‐patient ratio and the number of a set of predetermined key technologies available, as determined from institutions' responses to the American Hospital Association's annual survey.5

The 50 Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery, 50 Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders, and all Honor Roll hospitals (as determined by breadth of institutional excellence, with top performance in 6 or more of 17 specialties) named in 2004 and 2005 were included in this study, except that National Jewish Medical and Research Center was listed as a Best Hospital for respiratory disorders in both years but did not report sufficient numbers of cases to have eligible core measures in Hospital Compare. Of note, there were 11 institutions newly listed as Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery and 10 institutions newly listed as Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders in 2005 versus 2004; 14 hospitals made the Best Hospitals Honor Roll in 2004, and 2 others were added for 2005.

Data Analysis

To examine the internal validity of the Hospital Compare measures, we calculated pairwise correlation coefficients among the 14 core‐measure components, using all eligible data points. We then calculated Cronbach's , a measure of the internal consistency of scales of measures, to characterize each of the sets of Hospital Compare core measures separately (AMI, CHF, CAP). We also generated Cronbach's for a measure we called the combined core‐measures score, which we intended to be analogous to the Best Hospitals Honor Roll, defined as the AMI, CHF, and CAP measure sets scored together.

To compare Hospital Compare data with the Best Hospitals rankings (for heart and heart surgery, respiratory disorders, and the Honor Roll), we first established national quartile score cut points for each of the 3 Hospital Compare core measure sets and for the combined core measures, using all U.S. hospitals eligible for our analysis. We used quartiles to avoid the misclassification that would be more likely to occur with deciles (based on confidence intervals for the core measures provided by CMS).6

We calculated Hospital Compare scores for each institution listed as a Best Hospital in 2004 and 2005 and classified the Best Hospitals into scoring quartiles based on national score cut points (eg, if the national cutoff for AMI core measures for the top quartile was 95.2%, then a Best Hospital with an AMI score for the core‐measures set 95.2% was classified in the first [top] quartile). AMI and CHF core measure sets were used for comparison with the Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery, the CAP core‐measure set was used for comparison with the Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders, and the combined core‐measure set was used for comparison with the Honor Roll hospitals.

Sensitivity Analyses

To investigate the effect of missing Hospital Compare data on our study findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses. We used only those institutions with complete data for the AMI, CHF, and CAP core measure sets to establish new quartile cut points and then reexamined the quartile distribution for institutions in the corresponding Best Hospitals lists. We also compared the Best Hospitals' Hospital Compare data completeness with that of all Hospital Compare institutions.

RESULTS

Core Performance Measures in Hospital Compare

Of 4203 hospitals that submitted core measures as part of Hospital Compare, 4126 had at least 1 core measure eligible for analysis (> 25 observations). Of these 4126 hospitals, 2165 (52.5%) had at least 1 eligible AMI core measure, and 398 (9.7%) had all 6 measures eligible for analysis; 3130 had at least 1 eligible CHF core measure (75.9%), and 289 (7.0%) had all 4 measures eligible for analysis; and 3462 (83.9%) had at least one eligible CAP core measure and 302 (7.3%) had all 4 measures eligible for analysis. For the combined core‐measure score, 2119 (51.4%) had at least 4 eligible measures, and 120 (2.9%) had all 14 measures eligible for analysis.

Pairwise correlation coefficients within each of the disease‐specific core measure sets was highest for the AMI measures, and was generally higher for measures that reflected similar clinical activities (eg, aspirin and ‐blocker at discharge for AMI care; tobacco cessation counseling for AMI, CHF, and CAP; Table 2). In general, the AMI and CHF performance measures correlated more strongly with each other than did the AMI or CHF measures with the CAP measures.

Internal consistency within each of the disease‐specific measures was moderate to strong, with Cronbach's = .83 for AMI, Cronbach's = .58 for CHF, and Cronbach's = .49 for CAP. For the combined performance measure set (all 14 core measures together), Cronbach's = .74.

Hospital Compare Scores for Institutions Listed as Best Hospitals

Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery and for respiratory disorders in U.S. News and World Report in 2004 and 2005 exhibited a broad distribution of Hospital Compare core measure scores (Table 3). For none of the core measure sets did a majority of Best Hospitals score in the top quartile in either year.

| Hospital Compare Scores | Best Hospitals for Heart Disease: AMI Core Measures (n = 50 hospitals)* | Best Hospitals for Heart Disease: CHF Core Measures (n = 50 hospitals)* | Best Hospitals for Respiratory Disorders: CAP Core Measures (n = 49 hospitals)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 2004 | 2005 | 2004 | 2005 | 2004 | 2005 | |

| First quartile | 20 (40%) | 15 (30%) | 19 (38%) | 19 (38%) | 5 (10%) | 7 (14%) |

| Second quartile | 16 (32%) | 21 (42%) | 14 (28%) | 15 (30%) | 8 (16%) | 6 (12%) |

| Third quartile | 11 (22%) | 10 (20%) | 11 (22%) | 12 (24%) | 13 (27%) | 15 (31%) |

| Fourth quartile | 3 (6%) | 4 (8%) | 6 (12%) | 4 (8%) | 23 (47%) | 21 (43%) |

Among the 50 hospitals identified as best for cardiac care, only 20 (40%) in the 2004 list and 15 (30%) in the 2005 list had AMI core‐measure scores in the top quartile nationally, and 14 (28%) scored below the national median in both years. Among those same 50 hospitals, only 19 (38%) had CHF core‐measure scores in the top quartile nationally in both years, whereas 17 (34%) scored below the national median in 2004 and 16 in 2005. On the CAP core measures, Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders generally scored poorly, with only 5 (10%) from the 2004 list and 7 (14%) from the 2005 list in the top quartile nationally and nearly half the institutions scoring in the bottom national quartile (Table 3).

For the 14 hospitals named to the 2004 Honor Roll of Best Hospitals, the comparison with the combined core‐measure score (AMI, CHF, and CAP together) revealed a similarly broad distribution of core measure performance. Only five hospitals scored in the top quartile, 2 in the second quartile, 5 in the third quartile, and 2 in the bottom quartile. The distribution for hospitals in the 2005 Honor Roll was similar (5‐3‐6‐2 by quartile).

Sensitivity Analyses

National quartile Hospital Compare core‐measure cut points were slightly lower (1%‐2% in absolute terms) for those institutions with complete data than for institutions overall; in other words, institutions reporting on all 17 measures were generally more likely to have somewhat lower scores. These differences were substantive enough to shift the distribution of Best Hospitals in 2004 and 2005 up to higher quartiles for the AMI and CHF Hospital Compare measures but not for the CAP measures. For example, using the complete data AMI cut points, 23 of the 50 Best Hospitals for cardiac care in 2005 scored in the top quartile, 16 in the second quartile, 6 in the third quartile, and 5 in the bottom quartile (compared with 15‐21‐10‐4; Table 3). With complete data CHF cut points, the distribution was 26, 11, 9, and 4 for the 2005 Best Hospitals for cardiac care from the top through bottom quartiles, respectively (compared with 19‐15‐12‐4; Table 3). Results for 2004 sensitivity analyses were similar.

Institutions named as Best Hospitals appeared more likely than institutions overall to have complete Hospital Compare data. Whereas fewer than 10% of institutions in Hospital Compare had complete data for the AMI, CHF, and CAP core measures, 60% of Best Hospitals for cardiac care in 2005 had complete data for AMI measures and 44% for CHF measures, whereas 32% of Best Hospitals for respiratory care had complete CAP data.

DISCUSSION

With the public release of Hospital Compare data for more than 4200 hospitals in April 2005, national efforts to report hospital quality to the public passed a major milestone. Our findings indicate that the separate Hospital Compare measures for AMI, CHF, and CAP care have moderate to strong internal consistency, which suggests they are capturing similar hospital‐level care behaviors across institutions for these 3 common conditions.

However, Hospital Compare scores are largely discordant with the Best Hospital rank lists for cardiac and respiratory disorders care. Several institutions listed as Best Hospitals nationally scored below the national median on disease‐specific Hospital Compare core measures, perhaps leaving data‐conscious consumers to wonder how to synthesize rating systems that employ different indicators and measure different aspects of health care delivery.

Lack of Agreement in Hospital Quality Measurement

Discordance between the Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals rating systems is not all that surprising, given that their methods of institutional assessment differ markedly. Although both approaches share the goal of allowing consumers a comparative look at institutional performance nationally, they clearly measure different aspects of hospital care.

Hospital Compare measures focus on the delivery of disease‐specific, evidence‐based practices for 3 acute medical conditions from the emergency department to discharge. In comparison, the Best Hospitals rankings emphasize the reputation and mortality data of hospitals and health systems across a variety of general and subspecialty care settings (including several in which core quality measures have not yet been developed), combined with factors related to nursing and technology availability that may also influence consumers' choices. Of note, the Best Hospitals rating approach has been criticized in the past for its strong reliance on physicians' ratings of institutional reputation, which may have little to do with functional measures of quality.7

In essence, the Hospital Compare measures indicate how hospitals perform for an average case, while Best Hospitals relies on reputation and focus on mortality to indicate how institutions perform on the toughest cases. The question at hand is: are these institutional quality measures complementary or contradictory? Our findings suggest that Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals measures offer consumers a mix of complementary and contradictory information, depending on the institution.

The ratings systems differ in other respects as well. In Hospital Compare, performance data are available for more than 4000 hospitals, which permits consumers to examine their local institutions, whereas the Best Hospitals lists offer information only on the top performers. On the other hand, the more established Best Hospitals listings have been published annually for the last 15 years,5 permitting some longitudinal evaluation of hospitals' quality consistency. Importantly, neither rating system includes measures of patient satisfaction with hospital care.

One dimension that both rating systems share is the migration of quality measurement from the local and institutional level to the national stage. Historically, health care quality measurement has been a local phenomenon, as institutions work to gain larger shares of their local markets. A few hospitals have marketed their care and services regionally or even nationally and internationally, but these institutionswhich previously primarily used their reputation rather than specific outcome metrics to reach beyond their local communitiesare a minority of U.S. hospitals.

Although Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals are both national in scope, only Hospital Compare allows consumers to understand the quality of care in most of their community hospitals and health systems. Other investigators analyzing the same data set have highlighted significant differences in hospital performance according to for‐profit status, academic status, and size (number of beds).8

However, it is not yet clear if and how hospital ratings influence consumers' health care decisions. In fact, some studies suggest that only a minority of patients are inclined to use performance reports in their decisions about health care.9, 10 Moreover, if illness is acute, the factors driving choice of hospital may be geographic proximity, bed availability, and payer contracts rather than performance measures.

These constraints on the utility of hospital quality metrics from the consumer perspective are reminders that such metrics may have other benefits. Specifically, ratings such as Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals, as well as others such as those of the Leapfrog Group11 and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations,12 offer differing arrays of performance measures that may induce hospitals to improve their quality of care.1, 13 Institutions that score well or improve their scores over time can use such scores not only to benchmark their processes and outcomes but also to signal the comparative value of their care to the public. In the past, hospitals named to the Best Hospitals Honor Roll have trumpeted their achievements through plaques on their walls and in advertisements for their services. Whether institutions will do the same regarding their Hospital Compare scores remains to be seen.

Study Limitations

The chief limitation of this analysis is that not all hospitals reported data for the Hospital Compare core measures. We standardized the core‐measure sets for AMI, CHF, and CAP care for the number of measures reported in each set in order to include as many hospitals as possible in our analyses. Participation in Hospital Compare is voluntary (although strongly encouraged because of better Medicare reimbursement for institutions that participate), so it is possible that there was a systematic scoring bias in hospitals' incomplete reporting across all measures, that is, hospitals might not report specific core measure scores if they were particularly poor.13 That scale score medians were slightly lower for hospitals with complete data than for hospitals overall may indicate some reporting bias in the Hospital Compare data. Nevertheless, in the sensitivity analyses we performed using only those hospitals with complete data on the Hospital Compare core measures, comparisons with the Best Hospitals lists still predominantly indicated discordance between the rating systems.

Another limitation of this work is that we examined only 2 of several currently available hospital‐rating schemes. We chose to examine Hospital Compare because it is the first governmental effort to report specific hospital quality measures to the public, and we elected to look at Hospital Compare alongside the Best Hospitals lists because the latter are arguably the hospital ratings best known to the lay public.

A third potential limitation is that the Best Hospitals lists for 2004 were based in part on mortality figures and hospital survey data from 2002, which were the most recent data available at the time of the rankings; for the 2005 Best Hospitals lists, the most recent mortality and hospital survey data were collected in 2003.4 Hospital Compare scores were calculated on the basis of patients discharged in 2004, and therefore the ratings systems reflect somewhat different time frames. Nonetheless, we do not believe that this mismatch explains the extent of discordance between the 2 rating scales, particularly because there was such stability in the Best Hospital lists over the 2 years.

CONCLUSIONS

The Best Hospitals lists and Hospital Compare core measure scores agree only a minority of the time on the best institutions for the care of cardiac and respiratory conditions in the United States. Prominent, publicly reported hospital quality scorecards that paint discordant pictures of institutional performance potentially present a conundrum for physicians, patients, and payers with growing incentives to compare institutional quality.

If the movement to improve health care quality is to succeed, the challenge will be to harness the growing professional and lay interest in quality measurement to create rating scales that reflect the best aspects of Hospital Compare and the Best Hospitals lists, with the broadest inclusion of institutions and scope of conditions. For example, it would be more helpful to the public if the Best Hospitals lists included available Hospital Compare measures. It would also benefit consumers if Hospital Compare included more metrics about preventive and elective procedures, domains in which consumers can maximally exercise their choice of health care institutions. Moreover, voluntary reporting may constrain the quality effort. Only with mandatory reporting on quality measures will consistent and sufficient institutional accountability be achieved.

National concerns about the quality of health care in the United States have prompted calls for transparent efforts to measure and report hospital performance to the public. Consumer groups, payers, and credentialing organizations now rate the quality of hospitals and health care through a variety of mechanisms, yielding a kaleidoscope of quality measurement scorecards. However, health care consumers have minimal information about how hospital quality rating systems compare with each other or which rating system might best address their information needs.

The Hospital Compare Web site was launched in April 2005 by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA), a public‐private collaboration among organizations, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The CMS describes Hospital Compare as information [that] measures how well hospitals care for their patients.1 A limited set of Hospital Compare data from 2004 were posted online in 2005 for more than 4200 hospitals, permitting community‐specific comparisons of hospitals' self‐reported standardized core measures that reflect quality of care for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure (CHF), and community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) in adult patients.

Other current hospital quality evaluation tools target payers and purchasers of health care. However, many of these evaluations require that institutions pay a fee for submitting their data to be benchmarked against other participating institutions or require that the requesting individual or organization pay a fee to examine a hospital's performance on a specific condition or procedure.

We examined Hospital Compare data alongside that of another hospital rating system that has existed for a longer period of time and is likely better known to the lay publicthe Best Hospitals lists published annually by U.S. News and World Report.2, 3 Together, Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals are hospital quality scorecards that offer consumers assessments of hospital performance on a national scale. However, their measures of hospital quality differ, and we investigated whether they would provide consumers with concordant assessments of hospital quality.

METHODS

Data Sources

Hospital Compare

Core measure performance data were obtained by the investigators from the Hospital Compare Web site.3 Information in the database was provided by hospitals for the period January‐June 2004. Hospitals self‐reported their performance on the core measures using standardized medical record abstraction programs. The measures reported are cumulative averages based on monthly performance summaries.

Fourteen core measures were used in the study to form 3 core measure sets (Table 1): the AMI set comprised 6 measures, the CHF set comprised 4 measures, and the CAP site comprised 4 measures. Of the 17 core measures available on the Hospital Compare Web site, core measures of timing of thrombolytic agents or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for patients with AMI were excluded from the analysis because fewer than 10% of institutions reported such measures. Data on the core measure about oxygenation measurement for CAP were also excluded because of minimal variation between hospitals (national mean = 98%; the national mean for all other measures was less than 92%).3

| Condition | Core Measures |

|---|---|

| |

| Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) |

|

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) |

|

| Community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) |

|

Core measures that CMS defined as having too few cases (< 25) to reliably ascertain an estimate of hospital performance, or for which hospitals were not reporting data, were not eligible for analysis. To generate a composite score for each of the disease‐specific core measure sets, scores for all eligible core measures within each set were summed and then divided by the number of eligible measures available. This permitted standardization of the scores in the majority of instances when institutions did not report all eligible measures within a given set.

Best Hospitals

Ratings of hospitals were drawn from the 2004 and 2005 editions of the Best Hospitals listings of the U.S. News and World Report, the editions that most closely reflect performance data and physician survey data concurrent with Hospital Compare data analyzed for this study.4 In each year, ratings were developed for more than 2000 hospitals that met specific criteria related to teaching hospital status, medical school affiliation, or availability of specific technology‐related services.5 The Best Hospitals rating system is based on 3 central elements of evaluation: (a) reputation, judged by responses to a national mail survey of physicians asked to list the 5 hospitals best in their specialty for difficult cases, without economic or geographic considerations; (b) in‐hospital mortality rates for Medicare patients, adjusted for severity of illness; and (c) a combination of other factors, such as the nurse‐to‐patient ratio and the number of a set of predetermined key technologies available, as determined from institutions' responses to the American Hospital Association's annual survey.5

The 50 Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery, 50 Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders, and all Honor Roll hospitals (as determined by breadth of institutional excellence, with top performance in 6 or more of 17 specialties) named in 2004 and 2005 were included in this study, except that National Jewish Medical and Research Center was listed as a Best Hospital for respiratory disorders in both years but did not report sufficient numbers of cases to have eligible core measures in Hospital Compare. Of note, there were 11 institutions newly listed as Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery and 10 institutions newly listed as Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders in 2005 versus 2004; 14 hospitals made the Best Hospitals Honor Roll in 2004, and 2 others were added for 2005.

Data Analysis

To examine the internal validity of the Hospital Compare measures, we calculated pairwise correlation coefficients among the 14 core‐measure components, using all eligible data points. We then calculated Cronbach's , a measure of the internal consistency of scales of measures, to characterize each of the sets of Hospital Compare core measures separately (AMI, CHF, CAP). We also generated Cronbach's for a measure we called the combined core‐measures score, which we intended to be analogous to the Best Hospitals Honor Roll, defined as the AMI, CHF, and CAP measure sets scored together.

To compare Hospital Compare data with the Best Hospitals rankings (for heart and heart surgery, respiratory disorders, and the Honor Roll), we first established national quartile score cut points for each of the 3 Hospital Compare core measure sets and for the combined core measures, using all U.S. hospitals eligible for our analysis. We used quartiles to avoid the misclassification that would be more likely to occur with deciles (based on confidence intervals for the core measures provided by CMS).6

We calculated Hospital Compare scores for each institution listed as a Best Hospital in 2004 and 2005 and classified the Best Hospitals into scoring quartiles based on national score cut points (eg, if the national cutoff for AMI core measures for the top quartile was 95.2%, then a Best Hospital with an AMI score for the core‐measures set 95.2% was classified in the first [top] quartile). AMI and CHF core measure sets were used for comparison with the Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery, the CAP core‐measure set was used for comparison with the Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders, and the combined core‐measure set was used for comparison with the Honor Roll hospitals.

Sensitivity Analyses

To investigate the effect of missing Hospital Compare data on our study findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses. We used only those institutions with complete data for the AMI, CHF, and CAP core measure sets to establish new quartile cut points and then reexamined the quartile distribution for institutions in the corresponding Best Hospitals lists. We also compared the Best Hospitals' Hospital Compare data completeness with that of all Hospital Compare institutions.

RESULTS

Core Performance Measures in Hospital Compare

Of 4203 hospitals that submitted core measures as part of Hospital Compare, 4126 had at least 1 core measure eligible for analysis (> 25 observations). Of these 4126 hospitals, 2165 (52.5%) had at least 1 eligible AMI core measure, and 398 (9.7%) had all 6 measures eligible for analysis; 3130 had at least 1 eligible CHF core measure (75.9%), and 289 (7.0%) had all 4 measures eligible for analysis; and 3462 (83.9%) had at least one eligible CAP core measure and 302 (7.3%) had all 4 measures eligible for analysis. For the combined core‐measure score, 2119 (51.4%) had at least 4 eligible measures, and 120 (2.9%) had all 14 measures eligible for analysis.

Pairwise correlation coefficients within each of the disease‐specific core measure sets was highest for the AMI measures, and was generally higher for measures that reflected similar clinical activities (eg, aspirin and ‐blocker at discharge for AMI care; tobacco cessation counseling for AMI, CHF, and CAP; Table 2). In general, the AMI and CHF performance measures correlated more strongly with each other than did the AMI or CHF measures with the CAP measures.

Internal consistency within each of the disease‐specific measures was moderate to strong, with Cronbach's = .83 for AMI, Cronbach's = .58 for CHF, and Cronbach's = .49 for CAP. For the combined performance measure set (all 14 core measures together), Cronbach's = .74.

Hospital Compare Scores for Institutions Listed as Best Hospitals

Best Hospitals for heart and heart surgery and for respiratory disorders in U.S. News and World Report in 2004 and 2005 exhibited a broad distribution of Hospital Compare core measure scores (Table 3). For none of the core measure sets did a majority of Best Hospitals score in the top quartile in either year.

| Hospital Compare Scores | Best Hospitals for Heart Disease: AMI Core Measures (n = 50 hospitals)* | Best Hospitals for Heart Disease: CHF Core Measures (n = 50 hospitals)* | Best Hospitals for Respiratory Disorders: CAP Core Measures (n = 49 hospitals)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 2004 | 2005 | 2004 | 2005 | 2004 | 2005 | |

| First quartile | 20 (40%) | 15 (30%) | 19 (38%) | 19 (38%) | 5 (10%) | 7 (14%) |

| Second quartile | 16 (32%) | 21 (42%) | 14 (28%) | 15 (30%) | 8 (16%) | 6 (12%) |

| Third quartile | 11 (22%) | 10 (20%) | 11 (22%) | 12 (24%) | 13 (27%) | 15 (31%) |

| Fourth quartile | 3 (6%) | 4 (8%) | 6 (12%) | 4 (8%) | 23 (47%) | 21 (43%) |

Among the 50 hospitals identified as best for cardiac care, only 20 (40%) in the 2004 list and 15 (30%) in the 2005 list had AMI core‐measure scores in the top quartile nationally, and 14 (28%) scored below the national median in both years. Among those same 50 hospitals, only 19 (38%) had CHF core‐measure scores in the top quartile nationally in both years, whereas 17 (34%) scored below the national median in 2004 and 16 in 2005. On the CAP core measures, Best Hospitals for respiratory disorders generally scored poorly, with only 5 (10%) from the 2004 list and 7 (14%) from the 2005 list in the top quartile nationally and nearly half the institutions scoring in the bottom national quartile (Table 3).

For the 14 hospitals named to the 2004 Honor Roll of Best Hospitals, the comparison with the combined core‐measure score (AMI, CHF, and CAP together) revealed a similarly broad distribution of core measure performance. Only five hospitals scored in the top quartile, 2 in the second quartile, 5 in the third quartile, and 2 in the bottom quartile. The distribution for hospitals in the 2005 Honor Roll was similar (5‐3‐6‐2 by quartile).

Sensitivity Analyses

National quartile Hospital Compare core‐measure cut points were slightly lower (1%‐2% in absolute terms) for those institutions with complete data than for institutions overall; in other words, institutions reporting on all 17 measures were generally more likely to have somewhat lower scores. These differences were substantive enough to shift the distribution of Best Hospitals in 2004 and 2005 up to higher quartiles for the AMI and CHF Hospital Compare measures but not for the CAP measures. For example, using the complete data AMI cut points, 23 of the 50 Best Hospitals for cardiac care in 2005 scored in the top quartile, 16 in the second quartile, 6 in the third quartile, and 5 in the bottom quartile (compared with 15‐21‐10‐4; Table 3). With complete data CHF cut points, the distribution was 26, 11, 9, and 4 for the 2005 Best Hospitals for cardiac care from the top through bottom quartiles, respectively (compared with 19‐15‐12‐4; Table 3). Results for 2004 sensitivity analyses were similar.

Institutions named as Best Hospitals appeared more likely than institutions overall to have complete Hospital Compare data. Whereas fewer than 10% of institutions in Hospital Compare had complete data for the AMI, CHF, and CAP core measures, 60% of Best Hospitals for cardiac care in 2005 had complete data for AMI measures and 44% for CHF measures, whereas 32% of Best Hospitals for respiratory care had complete CAP data.

DISCUSSION

With the public release of Hospital Compare data for more than 4200 hospitals in April 2005, national efforts to report hospital quality to the public passed a major milestone. Our findings indicate that the separate Hospital Compare measures for AMI, CHF, and CAP care have moderate to strong internal consistency, which suggests they are capturing similar hospital‐level care behaviors across institutions for these 3 common conditions.

However, Hospital Compare scores are largely discordant with the Best Hospital rank lists for cardiac and respiratory disorders care. Several institutions listed as Best Hospitals nationally scored below the national median on disease‐specific Hospital Compare core measures, perhaps leaving data‐conscious consumers to wonder how to synthesize rating systems that employ different indicators and measure different aspects of health care delivery.

Lack of Agreement in Hospital Quality Measurement

Discordance between the Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals rating systems is not all that surprising, given that their methods of institutional assessment differ markedly. Although both approaches share the goal of allowing consumers a comparative look at institutional performance nationally, they clearly measure different aspects of hospital care.

Hospital Compare measures focus on the delivery of disease‐specific, evidence‐based practices for 3 acute medical conditions from the emergency department to discharge. In comparison, the Best Hospitals rankings emphasize the reputation and mortality data of hospitals and health systems across a variety of general and subspecialty care settings (including several in which core quality measures have not yet been developed), combined with factors related to nursing and technology availability that may also influence consumers' choices. Of note, the Best Hospitals rating approach has been criticized in the past for its strong reliance on physicians' ratings of institutional reputation, which may have little to do with functional measures of quality.7

In essence, the Hospital Compare measures indicate how hospitals perform for an average case, while Best Hospitals relies on reputation and focus on mortality to indicate how institutions perform on the toughest cases. The question at hand is: are these institutional quality measures complementary or contradictory? Our findings suggest that Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals measures offer consumers a mix of complementary and contradictory information, depending on the institution.

The ratings systems differ in other respects as well. In Hospital Compare, performance data are available for more than 4000 hospitals, which permits consumers to examine their local institutions, whereas the Best Hospitals lists offer information only on the top performers. On the other hand, the more established Best Hospitals listings have been published annually for the last 15 years,5 permitting some longitudinal evaluation of hospitals' quality consistency. Importantly, neither rating system includes measures of patient satisfaction with hospital care.

One dimension that both rating systems share is the migration of quality measurement from the local and institutional level to the national stage. Historically, health care quality measurement has been a local phenomenon, as institutions work to gain larger shares of their local markets. A few hospitals have marketed their care and services regionally or even nationally and internationally, but these institutionswhich previously primarily used their reputation rather than specific outcome metrics to reach beyond their local communitiesare a minority of U.S. hospitals.

Although Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals are both national in scope, only Hospital Compare allows consumers to understand the quality of care in most of their community hospitals and health systems. Other investigators analyzing the same data set have highlighted significant differences in hospital performance according to for‐profit status, academic status, and size (number of beds).8

However, it is not yet clear if and how hospital ratings influence consumers' health care decisions. In fact, some studies suggest that only a minority of patients are inclined to use performance reports in their decisions about health care.9, 10 Moreover, if illness is acute, the factors driving choice of hospital may be geographic proximity, bed availability, and payer contracts rather than performance measures.

These constraints on the utility of hospital quality metrics from the consumer perspective are reminders that such metrics may have other benefits. Specifically, ratings such as Hospital Compare and Best Hospitals, as well as others such as those of the Leapfrog Group11 and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations,12 offer differing arrays of performance measures that may induce hospitals to improve their quality of care.1, 13 Institutions that score well or improve their scores over time can use such scores not only to benchmark their processes and outcomes but also to signal the comparative value of their care to the public. In the past, hospitals named to the Best Hospitals Honor Roll have trumpeted their achievements through plaques on their walls and in advertisements for their services. Whether institutions will do the same regarding their Hospital Compare scores remains to be seen.

Study Limitations

The chief limitation of this analysis is that not all hospitals reported data for the Hospital Compare core measures. We standardized the core‐measure sets for AMI, CHF, and CAP care for the number of measures reported in each set in order to include as many hospitals as possible in our analyses. Participation in Hospital Compare is voluntary (although strongly encouraged because of better Medicare reimbursement for institutions that participate), so it is possible that there was a systematic scoring bias in hospitals' incomplete reporting across all measures, that is, hospitals might not report specific core measure scores if they were particularly poor.13 That scale score medians were slightly lower for hospitals with complete data than for hospitals overall may indicate some reporting bias in the Hospital Compare data. Nevertheless, in the sensitivity analyses we performed using only those hospitals with complete data on the Hospital Compare core measures, comparisons with the Best Hospitals lists still predominantly indicated discordance between the rating systems.

Another limitation of this work is that we examined only 2 of several currently available hospital‐rating schemes. We chose to examine Hospital Compare because it is the first governmental effort to report specific hospital quality measures to the public, and we elected to look at Hospital Compare alongside the Best Hospitals lists because the latter are arguably the hospital ratings best known to the lay public.

A third potential limitation is that the Best Hospitals lists for 2004 were based in part on mortality figures and hospital survey data from 2002, which were the most recent data available at the time of the rankings; for the 2005 Best Hospitals lists, the most recent mortality and hospital survey data were collected in 2003.4 Hospital Compare scores were calculated on the basis of patients discharged in 2004, and therefore the ratings systems reflect somewhat different time frames. Nonetheless, we do not believe that this mismatch explains the extent of discordance between the 2 rating scales, particularly because there was such stability in the Best Hospital lists over the 2 years.

CONCLUSIONS

The Best Hospitals lists and Hospital Compare core measure scores agree only a minority of the time on the best institutions for the care of cardiac and respiratory conditions in the United States. Prominent, publicly reported hospital quality scorecards that paint discordant pictures of institutional performance potentially present a conundrum for physicians, patients, and payers with growing incentives to compare institutional quality.

If the movement to improve health care quality is to succeed, the challenge will be to harness the growing professional and lay interest in quality measurement to create rating scales that reflect the best aspects of Hospital Compare and the Best Hospitals lists, with the broadest inclusion of institutions and scope of conditions. For example, it would be more helpful to the public if the Best Hospitals lists included available Hospital Compare measures. It would also benefit consumers if Hospital Compare included more metrics about preventive and elective procedures, domains in which consumers can maximally exercise their choice of health care institutions. Moreover, voluntary reporting may constrain the quality effort. Only with mandatory reporting on quality measures will consistent and sufficient institutional accountability be achieved.

- .Public performance reports and the will for change.JAMA.2002;288:1523–1524.

- .Improving the quality of care—can we practice what we preach?N Engl J Med.2003;348:2681–2683.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Accessed May 12,2005.

- U.S. News and World Report. Best hospitals 2005. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/usnews/health/best‐hospitals/tophosp.htm. Accessed July 10,2005.

- . Best hospitals 2005: methodology behind the rankings. U.S. News and World Report. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/usnews/health/best‐hospitals/methodology.htm. Accessed July 10,2005.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare: information for professionals. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/Hospital/Static/Data‐Professionals.asp?dest=NAV|Home|DataDetails|ProfessionalInfo#TabTop. Accessed May 12,2005.

- ,,,.In search of America's best hospitals: the promise and reality of quality assessment.JAMA.1997;277:1152–1155.

- ,,,.Care in US hospitals—the Hospital Quality Alliance program.N Engl Jour Med.2005;353:265–274.

- ,.Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery.JAMA.1998;279:1638–1642.

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.National Survey on Consumers' Experiences with Patient Safety and Quality Information.Washington, DC:Kaiser Family Foundation;2004.

- Leapfrog Group for Patient Safety. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org. Accessed May 12,2005.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Quality check. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/quality+check/index.htm. Accessed May 12,2005.

- ,.The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information.JAMA.2005;293:1239–1244.

- .Public performance reports and the will for change.JAMA.2002;288:1523–1524.

- .Improving the quality of care—can we practice what we preach?N Engl J Med.2003;348:2681–2683.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Accessed May 12,2005.

- U.S. News and World Report. Best hospitals 2005. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/usnews/health/best‐hospitals/tophosp.htm. Accessed July 10,2005.

- . Best hospitals 2005: methodology behind the rankings. U.S. News and World Report. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/usnews/health/best‐hospitals/methodology.htm. Accessed July 10,2005.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare: information for professionals. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/Hospital/Static/Data‐Professionals.asp?dest=NAV|Home|DataDetails|ProfessionalInfo#TabTop. Accessed May 12,2005.

- ,,,.In search of America's best hospitals: the promise and reality of quality assessment.JAMA.1997;277:1152–1155.

- ,,,.Care in US hospitals—the Hospital Quality Alliance program.N Engl Jour Med.2005;353:265–274.

- ,.Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery.JAMA.1998;279:1638–1642.

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.National Survey on Consumers' Experiences with Patient Safety and Quality Information.Washington, DC:Kaiser Family Foundation;2004.

- Leapfrog Group for Patient Safety. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org. Accessed May 12,2005.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Quality check. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/quality+check/index.htm. Accessed May 12,2005.

- ,.The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information.JAMA.2005;293:1239–1244.

Copyright © 2007 Society of Hospital Medicine

Impact of a Bedside Procedure Service

Inpatient bedside procedures are a major source of preventable adverse events in hospitals.1, 2 Unfortunately, many future inpatient physicians may lack the training3 and confidence4 to correct this problem. One proposed model for improving the teaching, performance, and evaluation of bedside procedures is a procedure service that is staffed by faculty who are experts at inpatient procedures.5 In a recent survey of internal medicine residents from our hospital, 86% (30 of 35) believed that expert supervision would improve central venous catheterization technique (Trick WE, personal communication).

Primary considerations in the development of a procedure service are the baseline demand for bedside procedures and whether a procedure service may affect this demand. Though variations in population‐based rates of some hospital procedures have been described,6, 7 there is little written on the demand for procedures performed at the bedsides of inpatients. Concomitant increases in demand and availability of other technologies810 suggest that improving the availability of bedside procedures may lead to an increase in their demand, regardless of whether such an increase benefits patients.11

Therefore, we sought to determine the impact of a bedside procedure service on the baseline number of paracenteses, thoracenteses, lumbar punctures (LPs), and central venous catheterizations (CVCs) performed on general medicine inpatients at our teaching hospital. In addition, we examined whether this service leads to more successful and safe procedure attempts.

METHODS

Design and Setting

In this prospective cohort study, the cohort was all patients admitted to the general medicine service at Cook County Hospital, a 500‐bed public teaching hospital in Chicago, Illinois, in January and February of 2006. The general medicine inpatient service is divided into 3 firms (A, B, and C), each with 4 separate teams of physicians and students. Admissions from the emergency department or other services in the hospital, such as intensive care units (which are closed and therefore staffed by separate teams of physicians), are distributed in sequence to on‐call teams from each firm. During the study period, the availability of a bedside procedure service varied by firm. Throughout the first 4 weeks, the service was available to only 1 of 3 firms (firm A). Then, during weeks 5 through 8, the service crossed over to the other 2 firms (firms B and C) and was unavailable to the original firm. Firm assignments for residents assigned to the inpatient service for all 8 weeks did not change. Of the 16 residents assigned to firm A during the first 4 weeks, when the procedure service was available, 3 remained on the wards during the second 4 weeks, when the procedure service was not available.

We chose to collect data on 4 bedside procedures: paracentesis, thoracentesis, LP, and CVC. Similar to those at other teaching hospitals, our residents informally acquire the skills to perform these procedures while assisting and being assisted by more experienced senior residents in a see one, do one, teach one apprenticeship model of learning.4 To improve the training and performance of these bedside procedures, the Department of Medicine piloted a bedside procedure service to teach procedural skills and assist residents during these procedures. Use of the service, though voluntary, was actively encouraged at residents' monthly orientation meetings and regular conferences.

One attending inpatient physician (J.A.) staffed the bedside procedure service, which was available during normal work hours on weekdays. Requests for procedures were made by general medicine residents through an online database and, after approval by the procedure service attending physician, were performed under his direct supervision. A hand‐carried ultrasound (MicroMaxx, Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA) that generates a 2‐dimensional gray‐scale image was used to both confirm the presence and location of fluid prior to paracentesis and thoracentesis and provide real‐time guidance during central venous catheterization. When the bedside procedure service was unavailable, residents performed bedside procedures in the usual fashion, typically without direct attending physician supervision. But if requested, an on‐call chief medical resident with access to a hand‐carried ultrasound device used by the intensive care unit was available for assistance at any time.

Subjects

The study subjects were all patients admitted to the general medical service during the 8‐week pilot period. Patients were excluded if they had been discharged before arrival on the medical wards or if they were under the care of the general medicine service for less than 6 hours before discharge or transfer to another service. We chose 6 hours because we reasoned that such brief admissions were not potential candidates for invasive bedside procedures.

Data Collection