User login

A Tough Egg to Crack

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with altered mental status. On the morning prior to admission, she was fully alert and oriented. Over the course of the day, she became more confused and somnolent, and by the evening, she was unarousable to voice. She had not fallen and had no head trauma.

Altered mental status may arise from metabolic (eg, hyponatremia), infectious (eg, urinary tract infection), structural (eg, subdural hematoma), or toxin-related (eg, adverse medication effect) processes. Any of these categories of encephalopathy can develop gradually over the course of a day.

One year prior, the patient was admitted for a similar episode of altered mental status. Asterixis and elevated transaminases prompted an abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a nodular liver and ascites. Paracentesis revealed a high serum-ascites albumin gradient. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made based on these findings. Testing for viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson’s disease were negative. Although steatosis was not detected on ultrasound, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was suspected based on the patient’s risk factors of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had four additional presentations of altered mental status with asterixis; each episode resolved with lactulose.

Other medical history included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. Her medications were labetalol, amlodipine, insulin, propranolol, lactulose, and rifaximin. She was originally from China and moved to the United States 10 years earlier. Given concerns about her ability to consistently take medications, she had moved to a long-term facility. She did not use alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substances.

The normalization of the patient’s mental status after lactulose treatment, especially in the context of recurrent episodes, is characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy, in which ammonia and other substances bypass hepatic metabolism and impair cerebral function. Hepatic encephalopathy is the most common cause of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy, and may recur in the setting of infection or nonadherence with lactulose and rifaximin. Other causes of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy include hyperammonemia caused by urease-producing bacterial infection (eg, Proteus), valproic acid toxicity, and urea cycle abnormalities.

Other causes of confusion with a self-limited course should be considered for the current episode. A postictal state is possible, but convulsions were not reported. The patient is at risk of hypoglycemia from insulin use and impaired gluconeogenesis due to cirrhosis and ESRD, but low blood sugar would have likely been detected at the time of hospitalization. Finally, she might have experienced episodic encephalopathy from ingestion of unreported medications or toxins, whose effects may have resolved with abstinence during hospitalization.

The patient’s temperature was 37.8°C, pulse 73 beats/minute, blood pressure 133/69 mmHg, respiratory rate 12 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on ambient air. Her body mass index (BMI) was 19 kg/m2. She was somnolent but was moving all four extremities spontaneously. Her pupils were symmetric and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. Biceps and patellar reflexes were 2+ bilaterally. Babinski sign was absent bilaterally. The patient could not cooperate with the assessment for asterixis. Her sclerae were anicteric. The jugular venous pressure was estimated at 13 cm of water. Her heart was regular with no murmurs. Her lungs were clear. She had a distended, nontender abdomen with caput medusae. She had symmetric pitting edema in her lower extremities up to the shins.

The elevated jugular venous pressure, lower extremity edema, and distended abdomen suggest volume overload. Jugular venous distention with clear lungs is characteristic of right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular myocardial infarction, tricuspid regurgitation, or constrictive pericarditis. However, chronic biventricular heart failure often presents in this manner and is more common than the aforementioned conditions. ESRD and cirrhosis may be contributing to the hypervolemia.

Although Asian patients may exhibit metabolic syndrome and NAFLD at a lower BMI than non-Asians, her BMI is uncharacteristically low for NAFLD, especially given the increased weight expected from volume overload. There are no signs of infection to account for worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory tests demonstrated a white blood cell count of 4400/µL with a normal differential, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count of 108,000 per cubic millimeter. Mean corpuscular volume was 103 fL. Basic metabolic panel was normal with the exception of blood urea nitrogen of 46 mg/dL and a creatinine of 6.4 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase was 34 units/L, alanine aminotransferase 34 units/L, alkaline phosphatase 289 units/L (normal, 31-95), gamma-glutamyl transferase 104 units (GGT, normal, 12-43), total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, and albumin 2.5 g/dL (normal, 3.5-4.5). Pro-brain natriuretic peptide was 1429 pg/mL (normal, <100). The international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.0. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria. The chest x-ray was normal. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head demonstrated no intracranial pathology. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal-sized nodular liver, a nonocclusive portal vein thrombus (PVT), splenomegaly (15 cm in length), and trace ascites. There was no biliary dilation, hepatic steatosis, or hepatic mass.

The evolving data set presents a mixed picture about the state of the liver. The distended abdominal wall veins, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly are commonly observed in advanced cirrhosis, but these findings reflect the associated portal hypertension and not the liver disease itself. The normal bilirubin and INR suggest preserved liver function and decrease the likelihood of cirrhosis being responsible for the portal hypertension. However, the elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels suggest an infiltrative liver disease, such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis.

Furthermore, while a nodular liver on imaging is consistent with cirrhosis, no steatosis was noted to support the presumed diagnosis of NAFLD. One explanation for this discrepancy is that fatty infiltration may be absent when NAFLD-associated cirrhosis develops. In summary, there is evidence of liver disease, and there is evidence of portal hypertension, but there is no evidence of liver parenchymal failure. The key features of the latter – spider angiomata, palmar erythema, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy – are absent.

Noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is an alternative explanation for the patient’s findings. NCPH is an elevation in the portal venous system pressure that arises from intrahepatic (but noncirrhotic) disease or from extrahepatic disease. Hepatic schistosomiasis is an example of intrahepatic but noncirrhotic portal hypertension. PVT that arises on account of a hypercoagulable condition (eg, abdominal malignancy, pancreatitis, or myeloproliferative disorders) is a prototype of extrahepatic NCPH. At this point, it is impossible to know if the PVT is a complication of NCPH or a cause of NCPH. PVT as a complication of cirrhosis is less likely.

An abdominal CT scan would better assess the hepatic parenchyma and exclude abdominal malignancies such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma. An echocardiogram is indicated to evaluate the cause of the elevated jugular venous pressure. A liver biopsy and measurement of portal venous pressure would help distinguish between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

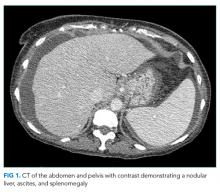

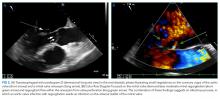

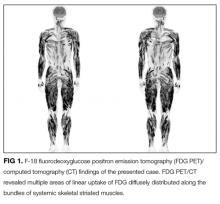

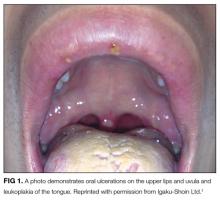

Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative as were antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies. Ferritin and ceruloplasmin levels were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated a nodular liver contour, splenomegaly, and a nonocclusive PVT (Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal biventricular systolic function and size, normal diastolic function, a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 57 mmHg (normal, < 25), moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and no pericardial effusion or thickening. The patient’s confusion and somnolence resolved after two days of lactulose therapy. She denied the use of other medications, supplements, or herbs.

Pulmonary hypertension is usually a consequence of cardiopulmonary disease, but there is no exam or imaging evidence for left ventricular failure, mitral stenosis, obstructive lung disease, or interstitial lung disease. Portopulmonary hypertension (a form of pulmonary hypertension) can develop as a consequence of end-stage liver disease. The most common cause of hepatic encephalopathy due to portosystemic shunting is cirrhosis, but such shunting also arises in NCPH.

Schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide. Parasite eggs trapped within the terminal portal venules cause inflammation, leading to fibrosis and intrahepatic portal hypertension. The liver becomes nodular on account of these changes, but the overall hepatic function is typically preserved. Portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, and pulmonary hypertension are common complications. The latter can arise from portosystemic shunting, which leads to embolization of schistosome eggs into the pulmonary circulation, where a granulomatous reaction ensues.

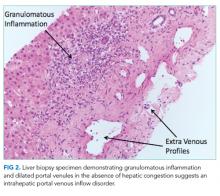

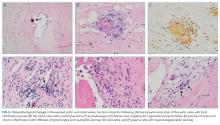

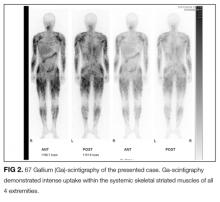

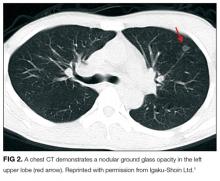

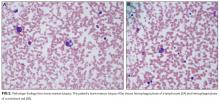

A percutaneous liver biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and dilated portal venules consistent with increased resistance to venous inflow (Figure 2). There was no sinusoidal congestion to indicate impaired hepatic venous outflow. Mild sinusoidal and portal fibrosis and increased iron in Kupffer cells were noted. There was no evidence of cirrhosis or steatohepatitis. Stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. 16S rDNA (a test assessing for bacterial DNA) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reactions were negative. The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Hepatic granulomas can arise from infectious, immunologic, toxic, and malignant diseases. In the United States, immunologic disorders, such as sarcoidosis and primary biliary cholangitis, are the most common causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The patient lacks extrahepatic features of the former. The absence of bile duct injury and negative antimitochondrial antibody exclude the latter. None of the listed medications are commonly associated with hepatic granulomas. The ultrasound, CT scan, and biopsy did not reveal a granulomatous malignancy such as lymphoma.

Infections, such as brucellosis, Q fever, and tuberculosis, are common causes of granulomatous hepatitis in the developing world. Tuberculosis is prevalent in China, but the test results do not support tuberculosis as a unifying diagnosis.

Schistosomiasis accounts for the major clinical features (portal and pulmonary hypertension and preserved liver function) and hepatic pathology (ie, portal venous fibrosis with granulomatous inflammation) in this case and is prevalent in China, where the patient emigrated from. The biopsy specimen should be re-examined for schistosome eggs and serologic tests for schistosomiasis pursued.

Antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus, Brucella, Bartonella quintana, Bartonella henselae, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, and Histoplasma were negative. Cryptococcal antigen and rapid plasma reagin were negative. IgG antibodies to Schistosoma were 0.21 units (normal, < 0.19 units). Based on the patient’s epidemiology, biopsy findings, and serology results, hepatic schistosomiasis was diagnosed. Praziquantel was prescribed. She continues to receive daily lactulose and rifaximin and has not had any episodes of encephalopathy in the year after discharge.

COMMENTARY

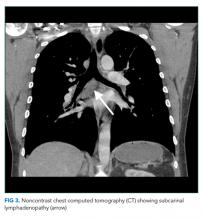

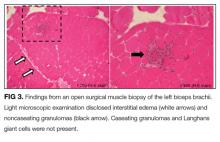

Portal hypertension arises when there is resistance to flow in the portal venous system. It is defined as a pressure gradient greater than 5 mmHg between the portal vein and the intra-abdominal portion of the inferior vena cava.1 Clinicians are familiar with the manifestations of portal hypertension – portosystemic shunting leading to encephalopathy and variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and splenomegaly with thrombocytopenia – because of their close association with cirrhosis. In developed countries, cirrhosis accounts for over 90% of cases of portal hypertension.1 In the remaining 10%, conditions such as portal vein thrombosis primarily affect the portal vasculature and increase resistance to portal blood flow while leaving hepatic synthetic function relatively spared (Figure 3). Therefore, cirrhosis cannot be inferred with certainty from signs of portal hypertension alone.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of cirrhosis, but this method is increasingly being replaced by noninvasive assessments of liver fibrosis, including imaging and scoring systems.2 Clinicians often infer cirrhosis from the combination of a known cause of liver injury, abnormal liver biochemical tests, evidence of liver dysfunction, and signs of portal hypertension.3 However, when signs of portal hypertension are present, but liver dysfunction cannot be established on physical exam (eg, palmar erythema, spider nevi, gynecomastia, and testicular atrophy) or laboratory testing (eg, low albumin, elevated INR, and elevated bilirubin), noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension should be considered. In this case, the biopsy showed vascular changes that suggested impaired venous inflow without bridging fibrosis, which pointed to NCPH.

NCPH is categorized based on the location of resistance to blood flow: prehepatic (eg, portal vein thrombosis), intrahepatic (eg, schistosomiasis), and posthepatic (eg, right-sided heart failure).1 In our patient, the dilated portal venules (inflow) in the presence of normal hepatic vein outflow suggested an increased intrahepatic resistance to blood flow. This finding excluded a causal role of the portal vein thrombosis and prompted testing for schistosomiasis.

Schistosomiasis affects more than 200 million people worldwide and is prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, Egypt, China, and Southeast Asia.4,5 Transmission occurs in fresh water, where the infectious form of the parasite is released from snails.4,6 Schistosome worms are not found in the United States, but as a result of immigration and travel, more than 400,000 people in the United States are estimated to be infected.5

Chronic schistosomiasis develops from the host’s granulomatous reaction to schistosome eggs whose location (depending on the species) leads to genitourinary, intestinal, hepatic, or rarely, neurologic disease.6 Hepatic schistosomiasis arises when eggs released in the portal venous system lodge in small portal venules and cause granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and microvascular obstruction.6 The resultant portal hypertension develops insidiously, but the architecture and synthetic function of the liver is maintained until the very late stages of disease.6,7 Pulmonary hypertension can arise from the embolization of eggs to the pulmonary arterioles via portosystemic collaterals.

The demonstration of eggs in stool is the gold standard for the diagnosis of hepatic schistosomiasis, which is most commonly caused by Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum.7 Serologic assays provide evidence of infection or exposure but may cross-react with other helminths. Liver biopsy may reveal characteristic histopathologic findings, including granulomatous inflammation, distorted vasculature, and the deposition of collagen deposits in the periportal space, leading to “pipestem fibrosis.”8,9 If eggs cannot be detected on stool or histology, then serology, secondary histologic changes, and sometimes PCR are used to diagnose hepatic schistosomiasis. In our patient, the epidemiology, Schistosoma antibody titer, pulmonary hypertension, and liver biopsy with granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and intrahepatic portal venule dilation were diagnostic of hepatic schistosomiasis.

The recurrent episodes of confusion which resolved with lactulose therapy were suggestive of hepatic encephalopathy, which results from shunting and accumulation of neurotoxic substances that would otherwise undergo hepatic metabolism.10 Clinicians are most familiar with hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis, where multiple liver functions – synthesis, excretion, metabolism, and circulation – simultaneously fail. NCPH represents a scenario where only the circulation is impaired, but this is sufficient to cause the portosystemic shunting that leads to encephalopathy. Our patient’s recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, despite adherence to lactulose and rifaximin and its resolution after praziquantel treatment, underscores the importance of addressing the underlying cause of portosystemic shunting.Associating portal hypertension with cirrhosis is efficient and accurate in many cases. However, when specific manifestations of cirrhosis are lacking, clinicians must decouple this association and pursue an alternative explanation for portal hypertension. The presence of some intrahepatic pathology (from schistosomiasis) but no cirrhosis made this case a particularly tough egg to crack.

Teaching Points

- In the developed world, 90% of portal hypertension is due to cirrhosis. Hepatic schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide.

- Chronic schistosomiasis affects the gastrointestinal, hepatic, and genitourinary systems and causes significant global morbidity and mortality.

- Visualization of schistosome eggs is the diagnostic gold standard. Indirect testing such as schistosoma antibodies and secondary histologic changes may be required for the diagnosis in patients with a low burden of eggs.

Disclosures

Dr. Geha has no disclosures. Dr. Dhaliwal reports receiving honoraria from ISMIE Mutual Insurance Company and Physicians’ Reciprocal Insurers. Dr. Peters’ spouse is employed by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Manesh is supported by the Jeremiah A. Barondess Fellowship in the Clinical Transaction of the New York Academy of Medicine, in collaboration with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

1. Sarin SK, Khanna R. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18(2):451-76. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2014.01.009. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):756-768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1610570. PubMed

3. Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.186. PubMed

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites–Schistosomiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/. Accessed December 2, 2017.

5. Bica I, Hamer DH, Stadecker MJ. Hepatic schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2000;14(3):583-604. PubMed

6. Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, et al. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1212-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. PubMed

7. Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, McManus DP. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 2011;342: 2561-2561. doi: doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2651. PubMed

8. Manzella A, Ohtomo K, Monzawa S, Lim JH. Schistosomiasis of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):144-50. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9329-7. PubMed

9. Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1106-18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PubMed

10. Blei AT, Córdoba J. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):1968. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. PubMed

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with altered mental status. On the morning prior to admission, she was fully alert and oriented. Over the course of the day, she became more confused and somnolent, and by the evening, she was unarousable to voice. She had not fallen and had no head trauma.

Altered mental status may arise from metabolic (eg, hyponatremia), infectious (eg, urinary tract infection), structural (eg, subdural hematoma), or toxin-related (eg, adverse medication effect) processes. Any of these categories of encephalopathy can develop gradually over the course of a day.

One year prior, the patient was admitted for a similar episode of altered mental status. Asterixis and elevated transaminases prompted an abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a nodular liver and ascites. Paracentesis revealed a high serum-ascites albumin gradient. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made based on these findings. Testing for viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson’s disease were negative. Although steatosis was not detected on ultrasound, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was suspected based on the patient’s risk factors of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had four additional presentations of altered mental status with asterixis; each episode resolved with lactulose.

Other medical history included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. Her medications were labetalol, amlodipine, insulin, propranolol, lactulose, and rifaximin. She was originally from China and moved to the United States 10 years earlier. Given concerns about her ability to consistently take medications, she had moved to a long-term facility. She did not use alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substances.

The normalization of the patient’s mental status after lactulose treatment, especially in the context of recurrent episodes, is characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy, in which ammonia and other substances bypass hepatic metabolism and impair cerebral function. Hepatic encephalopathy is the most common cause of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy, and may recur in the setting of infection or nonadherence with lactulose and rifaximin. Other causes of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy include hyperammonemia caused by urease-producing bacterial infection (eg, Proteus), valproic acid toxicity, and urea cycle abnormalities.

Other causes of confusion with a self-limited course should be considered for the current episode. A postictal state is possible, but convulsions were not reported. The patient is at risk of hypoglycemia from insulin use and impaired gluconeogenesis due to cirrhosis and ESRD, but low blood sugar would have likely been detected at the time of hospitalization. Finally, she might have experienced episodic encephalopathy from ingestion of unreported medications or toxins, whose effects may have resolved with abstinence during hospitalization.

The patient’s temperature was 37.8°C, pulse 73 beats/minute, blood pressure 133/69 mmHg, respiratory rate 12 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on ambient air. Her body mass index (BMI) was 19 kg/m2. She was somnolent but was moving all four extremities spontaneously. Her pupils were symmetric and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. Biceps and patellar reflexes were 2+ bilaterally. Babinski sign was absent bilaterally. The patient could not cooperate with the assessment for asterixis. Her sclerae were anicteric. The jugular venous pressure was estimated at 13 cm of water. Her heart was regular with no murmurs. Her lungs were clear. She had a distended, nontender abdomen with caput medusae. She had symmetric pitting edema in her lower extremities up to the shins.

The elevated jugular venous pressure, lower extremity edema, and distended abdomen suggest volume overload. Jugular venous distention with clear lungs is characteristic of right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular myocardial infarction, tricuspid regurgitation, or constrictive pericarditis. However, chronic biventricular heart failure often presents in this manner and is more common than the aforementioned conditions. ESRD and cirrhosis may be contributing to the hypervolemia.

Although Asian patients may exhibit metabolic syndrome and NAFLD at a lower BMI than non-Asians, her BMI is uncharacteristically low for NAFLD, especially given the increased weight expected from volume overload. There are no signs of infection to account for worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory tests demonstrated a white blood cell count of 4400/µL with a normal differential, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count of 108,000 per cubic millimeter. Mean corpuscular volume was 103 fL. Basic metabolic panel was normal with the exception of blood urea nitrogen of 46 mg/dL and a creatinine of 6.4 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase was 34 units/L, alanine aminotransferase 34 units/L, alkaline phosphatase 289 units/L (normal, 31-95), gamma-glutamyl transferase 104 units (GGT, normal, 12-43), total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, and albumin 2.5 g/dL (normal, 3.5-4.5). Pro-brain natriuretic peptide was 1429 pg/mL (normal, <100). The international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.0. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria. The chest x-ray was normal. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head demonstrated no intracranial pathology. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal-sized nodular liver, a nonocclusive portal vein thrombus (PVT), splenomegaly (15 cm in length), and trace ascites. There was no biliary dilation, hepatic steatosis, or hepatic mass.

The evolving data set presents a mixed picture about the state of the liver. The distended abdominal wall veins, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly are commonly observed in advanced cirrhosis, but these findings reflect the associated portal hypertension and not the liver disease itself. The normal bilirubin and INR suggest preserved liver function and decrease the likelihood of cirrhosis being responsible for the portal hypertension. However, the elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels suggest an infiltrative liver disease, such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis.

Furthermore, while a nodular liver on imaging is consistent with cirrhosis, no steatosis was noted to support the presumed diagnosis of NAFLD. One explanation for this discrepancy is that fatty infiltration may be absent when NAFLD-associated cirrhosis develops. In summary, there is evidence of liver disease, and there is evidence of portal hypertension, but there is no evidence of liver parenchymal failure. The key features of the latter – spider angiomata, palmar erythema, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy – are absent.

Noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is an alternative explanation for the patient’s findings. NCPH is an elevation in the portal venous system pressure that arises from intrahepatic (but noncirrhotic) disease or from extrahepatic disease. Hepatic schistosomiasis is an example of intrahepatic but noncirrhotic portal hypertension. PVT that arises on account of a hypercoagulable condition (eg, abdominal malignancy, pancreatitis, or myeloproliferative disorders) is a prototype of extrahepatic NCPH. At this point, it is impossible to know if the PVT is a complication of NCPH or a cause of NCPH. PVT as a complication of cirrhosis is less likely.

An abdominal CT scan would better assess the hepatic parenchyma and exclude abdominal malignancies such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma. An echocardiogram is indicated to evaluate the cause of the elevated jugular venous pressure. A liver biopsy and measurement of portal venous pressure would help distinguish between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative as were antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies. Ferritin and ceruloplasmin levels were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated a nodular liver contour, splenomegaly, and a nonocclusive PVT (Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal biventricular systolic function and size, normal diastolic function, a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 57 mmHg (normal, < 25), moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and no pericardial effusion or thickening. The patient’s confusion and somnolence resolved after two days of lactulose therapy. She denied the use of other medications, supplements, or herbs.

Pulmonary hypertension is usually a consequence of cardiopulmonary disease, but there is no exam or imaging evidence for left ventricular failure, mitral stenosis, obstructive lung disease, or interstitial lung disease. Portopulmonary hypertension (a form of pulmonary hypertension) can develop as a consequence of end-stage liver disease. The most common cause of hepatic encephalopathy due to portosystemic shunting is cirrhosis, but such shunting also arises in NCPH.

Schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide. Parasite eggs trapped within the terminal portal venules cause inflammation, leading to fibrosis and intrahepatic portal hypertension. The liver becomes nodular on account of these changes, but the overall hepatic function is typically preserved. Portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, and pulmonary hypertension are common complications. The latter can arise from portosystemic shunting, which leads to embolization of schistosome eggs into the pulmonary circulation, where a granulomatous reaction ensues.

A percutaneous liver biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and dilated portal venules consistent with increased resistance to venous inflow (Figure 2). There was no sinusoidal congestion to indicate impaired hepatic venous outflow. Mild sinusoidal and portal fibrosis and increased iron in Kupffer cells were noted. There was no evidence of cirrhosis or steatohepatitis. Stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. 16S rDNA (a test assessing for bacterial DNA) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reactions were negative. The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Hepatic granulomas can arise from infectious, immunologic, toxic, and malignant diseases. In the United States, immunologic disorders, such as sarcoidosis and primary biliary cholangitis, are the most common causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The patient lacks extrahepatic features of the former. The absence of bile duct injury and negative antimitochondrial antibody exclude the latter. None of the listed medications are commonly associated with hepatic granulomas. The ultrasound, CT scan, and biopsy did not reveal a granulomatous malignancy such as lymphoma.

Infections, such as brucellosis, Q fever, and tuberculosis, are common causes of granulomatous hepatitis in the developing world. Tuberculosis is prevalent in China, but the test results do not support tuberculosis as a unifying diagnosis.

Schistosomiasis accounts for the major clinical features (portal and pulmonary hypertension and preserved liver function) and hepatic pathology (ie, portal venous fibrosis with granulomatous inflammation) in this case and is prevalent in China, where the patient emigrated from. The biopsy specimen should be re-examined for schistosome eggs and serologic tests for schistosomiasis pursued.

Antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus, Brucella, Bartonella quintana, Bartonella henselae, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, and Histoplasma were negative. Cryptococcal antigen and rapid plasma reagin were negative. IgG antibodies to Schistosoma were 0.21 units (normal, < 0.19 units). Based on the patient’s epidemiology, biopsy findings, and serology results, hepatic schistosomiasis was diagnosed. Praziquantel was prescribed. She continues to receive daily lactulose and rifaximin and has not had any episodes of encephalopathy in the year after discharge.

COMMENTARY

Portal hypertension arises when there is resistance to flow in the portal venous system. It is defined as a pressure gradient greater than 5 mmHg between the portal vein and the intra-abdominal portion of the inferior vena cava.1 Clinicians are familiar with the manifestations of portal hypertension – portosystemic shunting leading to encephalopathy and variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and splenomegaly with thrombocytopenia – because of their close association with cirrhosis. In developed countries, cirrhosis accounts for over 90% of cases of portal hypertension.1 In the remaining 10%, conditions such as portal vein thrombosis primarily affect the portal vasculature and increase resistance to portal blood flow while leaving hepatic synthetic function relatively spared (Figure 3). Therefore, cirrhosis cannot be inferred with certainty from signs of portal hypertension alone.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of cirrhosis, but this method is increasingly being replaced by noninvasive assessments of liver fibrosis, including imaging and scoring systems.2 Clinicians often infer cirrhosis from the combination of a known cause of liver injury, abnormal liver biochemical tests, evidence of liver dysfunction, and signs of portal hypertension.3 However, when signs of portal hypertension are present, but liver dysfunction cannot be established on physical exam (eg, palmar erythema, spider nevi, gynecomastia, and testicular atrophy) or laboratory testing (eg, low albumin, elevated INR, and elevated bilirubin), noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension should be considered. In this case, the biopsy showed vascular changes that suggested impaired venous inflow without bridging fibrosis, which pointed to NCPH.

NCPH is categorized based on the location of resistance to blood flow: prehepatic (eg, portal vein thrombosis), intrahepatic (eg, schistosomiasis), and posthepatic (eg, right-sided heart failure).1 In our patient, the dilated portal venules (inflow) in the presence of normal hepatic vein outflow suggested an increased intrahepatic resistance to blood flow. This finding excluded a causal role of the portal vein thrombosis and prompted testing for schistosomiasis.

Schistosomiasis affects more than 200 million people worldwide and is prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, Egypt, China, and Southeast Asia.4,5 Transmission occurs in fresh water, where the infectious form of the parasite is released from snails.4,6 Schistosome worms are not found in the United States, but as a result of immigration and travel, more than 400,000 people in the United States are estimated to be infected.5

Chronic schistosomiasis develops from the host’s granulomatous reaction to schistosome eggs whose location (depending on the species) leads to genitourinary, intestinal, hepatic, or rarely, neurologic disease.6 Hepatic schistosomiasis arises when eggs released in the portal venous system lodge in small portal venules and cause granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and microvascular obstruction.6 The resultant portal hypertension develops insidiously, but the architecture and synthetic function of the liver is maintained until the very late stages of disease.6,7 Pulmonary hypertension can arise from the embolization of eggs to the pulmonary arterioles via portosystemic collaterals.

The demonstration of eggs in stool is the gold standard for the diagnosis of hepatic schistosomiasis, which is most commonly caused by Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum.7 Serologic assays provide evidence of infection or exposure but may cross-react with other helminths. Liver biopsy may reveal characteristic histopathologic findings, including granulomatous inflammation, distorted vasculature, and the deposition of collagen deposits in the periportal space, leading to “pipestem fibrosis.”8,9 If eggs cannot be detected on stool or histology, then serology, secondary histologic changes, and sometimes PCR are used to diagnose hepatic schistosomiasis. In our patient, the epidemiology, Schistosoma antibody titer, pulmonary hypertension, and liver biopsy with granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and intrahepatic portal venule dilation were diagnostic of hepatic schistosomiasis.

The recurrent episodes of confusion which resolved with lactulose therapy were suggestive of hepatic encephalopathy, which results from shunting and accumulation of neurotoxic substances that would otherwise undergo hepatic metabolism.10 Clinicians are most familiar with hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis, where multiple liver functions – synthesis, excretion, metabolism, and circulation – simultaneously fail. NCPH represents a scenario where only the circulation is impaired, but this is sufficient to cause the portosystemic shunting that leads to encephalopathy. Our patient’s recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, despite adherence to lactulose and rifaximin and its resolution after praziquantel treatment, underscores the importance of addressing the underlying cause of portosystemic shunting.Associating portal hypertension with cirrhosis is efficient and accurate in many cases. However, when specific manifestations of cirrhosis are lacking, clinicians must decouple this association and pursue an alternative explanation for portal hypertension. The presence of some intrahepatic pathology (from schistosomiasis) but no cirrhosis made this case a particularly tough egg to crack.

Teaching Points

- In the developed world, 90% of portal hypertension is due to cirrhosis. Hepatic schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide.

- Chronic schistosomiasis affects the gastrointestinal, hepatic, and genitourinary systems and causes significant global morbidity and mortality.

- Visualization of schistosome eggs is the diagnostic gold standard. Indirect testing such as schistosoma antibodies and secondary histologic changes may be required for the diagnosis in patients with a low burden of eggs.

Disclosures

Dr. Geha has no disclosures. Dr. Dhaliwal reports receiving honoraria from ISMIE Mutual Insurance Company and Physicians’ Reciprocal Insurers. Dr. Peters’ spouse is employed by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Manesh is supported by the Jeremiah A. Barondess Fellowship in the Clinical Transaction of the New York Academy of Medicine, in collaboration with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with altered mental status. On the morning prior to admission, she was fully alert and oriented. Over the course of the day, she became more confused and somnolent, and by the evening, she was unarousable to voice. She had not fallen and had no head trauma.

Altered mental status may arise from metabolic (eg, hyponatremia), infectious (eg, urinary tract infection), structural (eg, subdural hematoma), or toxin-related (eg, adverse medication effect) processes. Any of these categories of encephalopathy can develop gradually over the course of a day.

One year prior, the patient was admitted for a similar episode of altered mental status. Asterixis and elevated transaminases prompted an abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a nodular liver and ascites. Paracentesis revealed a high serum-ascites albumin gradient. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made based on these findings. Testing for viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson’s disease were negative. Although steatosis was not detected on ultrasound, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was suspected based on the patient’s risk factors of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had four additional presentations of altered mental status with asterixis; each episode resolved with lactulose.

Other medical history included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. Her medications were labetalol, amlodipine, insulin, propranolol, lactulose, and rifaximin. She was originally from China and moved to the United States 10 years earlier. Given concerns about her ability to consistently take medications, she had moved to a long-term facility. She did not use alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substances.

The normalization of the patient’s mental status after lactulose treatment, especially in the context of recurrent episodes, is characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy, in which ammonia and other substances bypass hepatic metabolism and impair cerebral function. Hepatic encephalopathy is the most common cause of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy, and may recur in the setting of infection or nonadherence with lactulose and rifaximin. Other causes of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy include hyperammonemia caused by urease-producing bacterial infection (eg, Proteus), valproic acid toxicity, and urea cycle abnormalities.

Other causes of confusion with a self-limited course should be considered for the current episode. A postictal state is possible, but convulsions were not reported. The patient is at risk of hypoglycemia from insulin use and impaired gluconeogenesis due to cirrhosis and ESRD, but low blood sugar would have likely been detected at the time of hospitalization. Finally, she might have experienced episodic encephalopathy from ingestion of unreported medications or toxins, whose effects may have resolved with abstinence during hospitalization.

The patient’s temperature was 37.8°C, pulse 73 beats/minute, blood pressure 133/69 mmHg, respiratory rate 12 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on ambient air. Her body mass index (BMI) was 19 kg/m2. She was somnolent but was moving all four extremities spontaneously. Her pupils were symmetric and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. Biceps and patellar reflexes were 2+ bilaterally. Babinski sign was absent bilaterally. The patient could not cooperate with the assessment for asterixis. Her sclerae were anicteric. The jugular venous pressure was estimated at 13 cm of water. Her heart was regular with no murmurs. Her lungs were clear. She had a distended, nontender abdomen with caput medusae. She had symmetric pitting edema in her lower extremities up to the shins.

The elevated jugular venous pressure, lower extremity edema, and distended abdomen suggest volume overload. Jugular venous distention with clear lungs is characteristic of right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular myocardial infarction, tricuspid regurgitation, or constrictive pericarditis. However, chronic biventricular heart failure often presents in this manner and is more common than the aforementioned conditions. ESRD and cirrhosis may be contributing to the hypervolemia.

Although Asian patients may exhibit metabolic syndrome and NAFLD at a lower BMI than non-Asians, her BMI is uncharacteristically low for NAFLD, especially given the increased weight expected from volume overload. There are no signs of infection to account for worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory tests demonstrated a white blood cell count of 4400/µL with a normal differential, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count of 108,000 per cubic millimeter. Mean corpuscular volume was 103 fL. Basic metabolic panel was normal with the exception of blood urea nitrogen of 46 mg/dL and a creatinine of 6.4 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase was 34 units/L, alanine aminotransferase 34 units/L, alkaline phosphatase 289 units/L (normal, 31-95), gamma-glutamyl transferase 104 units (GGT, normal, 12-43), total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, and albumin 2.5 g/dL (normal, 3.5-4.5). Pro-brain natriuretic peptide was 1429 pg/mL (normal, <100). The international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.0. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria. The chest x-ray was normal. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head demonstrated no intracranial pathology. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal-sized nodular liver, a nonocclusive portal vein thrombus (PVT), splenomegaly (15 cm in length), and trace ascites. There was no biliary dilation, hepatic steatosis, or hepatic mass.

The evolving data set presents a mixed picture about the state of the liver. The distended abdominal wall veins, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly are commonly observed in advanced cirrhosis, but these findings reflect the associated portal hypertension and not the liver disease itself. The normal bilirubin and INR suggest preserved liver function and decrease the likelihood of cirrhosis being responsible for the portal hypertension. However, the elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels suggest an infiltrative liver disease, such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis.

Furthermore, while a nodular liver on imaging is consistent with cirrhosis, no steatosis was noted to support the presumed diagnosis of NAFLD. One explanation for this discrepancy is that fatty infiltration may be absent when NAFLD-associated cirrhosis develops. In summary, there is evidence of liver disease, and there is evidence of portal hypertension, but there is no evidence of liver parenchymal failure. The key features of the latter – spider angiomata, palmar erythema, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy – are absent.

Noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is an alternative explanation for the patient’s findings. NCPH is an elevation in the portal venous system pressure that arises from intrahepatic (but noncirrhotic) disease or from extrahepatic disease. Hepatic schistosomiasis is an example of intrahepatic but noncirrhotic portal hypertension. PVT that arises on account of a hypercoagulable condition (eg, abdominal malignancy, pancreatitis, or myeloproliferative disorders) is a prototype of extrahepatic NCPH. At this point, it is impossible to know if the PVT is a complication of NCPH or a cause of NCPH. PVT as a complication of cirrhosis is less likely.

An abdominal CT scan would better assess the hepatic parenchyma and exclude abdominal malignancies such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma. An echocardiogram is indicated to evaluate the cause of the elevated jugular venous pressure. A liver biopsy and measurement of portal venous pressure would help distinguish between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative as were antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies. Ferritin and ceruloplasmin levels were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated a nodular liver contour, splenomegaly, and a nonocclusive PVT (Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal biventricular systolic function and size, normal diastolic function, a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 57 mmHg (normal, < 25), moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and no pericardial effusion or thickening. The patient’s confusion and somnolence resolved after two days of lactulose therapy. She denied the use of other medications, supplements, or herbs.

Pulmonary hypertension is usually a consequence of cardiopulmonary disease, but there is no exam or imaging evidence for left ventricular failure, mitral stenosis, obstructive lung disease, or interstitial lung disease. Portopulmonary hypertension (a form of pulmonary hypertension) can develop as a consequence of end-stage liver disease. The most common cause of hepatic encephalopathy due to portosystemic shunting is cirrhosis, but such shunting also arises in NCPH.

Schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide. Parasite eggs trapped within the terminal portal venules cause inflammation, leading to fibrosis and intrahepatic portal hypertension. The liver becomes nodular on account of these changes, but the overall hepatic function is typically preserved. Portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, and pulmonary hypertension are common complications. The latter can arise from portosystemic shunting, which leads to embolization of schistosome eggs into the pulmonary circulation, where a granulomatous reaction ensues.

A percutaneous liver biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and dilated portal venules consistent with increased resistance to venous inflow (Figure 2). There was no sinusoidal congestion to indicate impaired hepatic venous outflow. Mild sinusoidal and portal fibrosis and increased iron in Kupffer cells were noted. There was no evidence of cirrhosis or steatohepatitis. Stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. 16S rDNA (a test assessing for bacterial DNA) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reactions were negative. The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Hepatic granulomas can arise from infectious, immunologic, toxic, and malignant diseases. In the United States, immunologic disorders, such as sarcoidosis and primary biliary cholangitis, are the most common causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The patient lacks extrahepatic features of the former. The absence of bile duct injury and negative antimitochondrial antibody exclude the latter. None of the listed medications are commonly associated with hepatic granulomas. The ultrasound, CT scan, and biopsy did not reveal a granulomatous malignancy such as lymphoma.

Infections, such as brucellosis, Q fever, and tuberculosis, are common causes of granulomatous hepatitis in the developing world. Tuberculosis is prevalent in China, but the test results do not support tuberculosis as a unifying diagnosis.

Schistosomiasis accounts for the major clinical features (portal and pulmonary hypertension and preserved liver function) and hepatic pathology (ie, portal venous fibrosis with granulomatous inflammation) in this case and is prevalent in China, where the patient emigrated from. The biopsy specimen should be re-examined for schistosome eggs and serologic tests for schistosomiasis pursued.

Antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus, Brucella, Bartonella quintana, Bartonella henselae, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, and Histoplasma were negative. Cryptococcal antigen and rapid plasma reagin were negative. IgG antibodies to Schistosoma were 0.21 units (normal, < 0.19 units). Based on the patient’s epidemiology, biopsy findings, and serology results, hepatic schistosomiasis was diagnosed. Praziquantel was prescribed. She continues to receive daily lactulose and rifaximin and has not had any episodes of encephalopathy in the year after discharge.

COMMENTARY

Portal hypertension arises when there is resistance to flow in the portal venous system. It is defined as a pressure gradient greater than 5 mmHg between the portal vein and the intra-abdominal portion of the inferior vena cava.1 Clinicians are familiar with the manifestations of portal hypertension – portosystemic shunting leading to encephalopathy and variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and splenomegaly with thrombocytopenia – because of their close association with cirrhosis. In developed countries, cirrhosis accounts for over 90% of cases of portal hypertension.1 In the remaining 10%, conditions such as portal vein thrombosis primarily affect the portal vasculature and increase resistance to portal blood flow while leaving hepatic synthetic function relatively spared (Figure 3). Therefore, cirrhosis cannot be inferred with certainty from signs of portal hypertension alone.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of cirrhosis, but this method is increasingly being replaced by noninvasive assessments of liver fibrosis, including imaging and scoring systems.2 Clinicians often infer cirrhosis from the combination of a known cause of liver injury, abnormal liver biochemical tests, evidence of liver dysfunction, and signs of portal hypertension.3 However, when signs of portal hypertension are present, but liver dysfunction cannot be established on physical exam (eg, palmar erythema, spider nevi, gynecomastia, and testicular atrophy) or laboratory testing (eg, low albumin, elevated INR, and elevated bilirubin), noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension should be considered. In this case, the biopsy showed vascular changes that suggested impaired venous inflow without bridging fibrosis, which pointed to NCPH.

NCPH is categorized based on the location of resistance to blood flow: prehepatic (eg, portal vein thrombosis), intrahepatic (eg, schistosomiasis), and posthepatic (eg, right-sided heart failure).1 In our patient, the dilated portal venules (inflow) in the presence of normal hepatic vein outflow suggested an increased intrahepatic resistance to blood flow. This finding excluded a causal role of the portal vein thrombosis and prompted testing for schistosomiasis.

Schistosomiasis affects more than 200 million people worldwide and is prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, Egypt, China, and Southeast Asia.4,5 Transmission occurs in fresh water, where the infectious form of the parasite is released from snails.4,6 Schistosome worms are not found in the United States, but as a result of immigration and travel, more than 400,000 people in the United States are estimated to be infected.5

Chronic schistosomiasis develops from the host’s granulomatous reaction to schistosome eggs whose location (depending on the species) leads to genitourinary, intestinal, hepatic, or rarely, neurologic disease.6 Hepatic schistosomiasis arises when eggs released in the portal venous system lodge in small portal venules and cause granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and microvascular obstruction.6 The resultant portal hypertension develops insidiously, but the architecture and synthetic function of the liver is maintained until the very late stages of disease.6,7 Pulmonary hypertension can arise from the embolization of eggs to the pulmonary arterioles via portosystemic collaterals.

The demonstration of eggs in stool is the gold standard for the diagnosis of hepatic schistosomiasis, which is most commonly caused by Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum.7 Serologic assays provide evidence of infection or exposure but may cross-react with other helminths. Liver biopsy may reveal characteristic histopathologic findings, including granulomatous inflammation, distorted vasculature, and the deposition of collagen deposits in the periportal space, leading to “pipestem fibrosis.”8,9 If eggs cannot be detected on stool or histology, then serology, secondary histologic changes, and sometimes PCR are used to diagnose hepatic schistosomiasis. In our patient, the epidemiology, Schistosoma antibody titer, pulmonary hypertension, and liver biopsy with granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and intrahepatic portal venule dilation were diagnostic of hepatic schistosomiasis.

The recurrent episodes of confusion which resolved with lactulose therapy were suggestive of hepatic encephalopathy, which results from shunting and accumulation of neurotoxic substances that would otherwise undergo hepatic metabolism.10 Clinicians are most familiar with hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis, where multiple liver functions – synthesis, excretion, metabolism, and circulation – simultaneously fail. NCPH represents a scenario where only the circulation is impaired, but this is sufficient to cause the portosystemic shunting that leads to encephalopathy. Our patient’s recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, despite adherence to lactulose and rifaximin and its resolution after praziquantel treatment, underscores the importance of addressing the underlying cause of portosystemic shunting.Associating portal hypertension with cirrhosis is efficient and accurate in many cases. However, when specific manifestations of cirrhosis are lacking, clinicians must decouple this association and pursue an alternative explanation for portal hypertension. The presence of some intrahepatic pathology (from schistosomiasis) but no cirrhosis made this case a particularly tough egg to crack.

Teaching Points

- In the developed world, 90% of portal hypertension is due to cirrhosis. Hepatic schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide.

- Chronic schistosomiasis affects the gastrointestinal, hepatic, and genitourinary systems and causes significant global morbidity and mortality.

- Visualization of schistosome eggs is the diagnostic gold standard. Indirect testing such as schistosoma antibodies and secondary histologic changes may be required for the diagnosis in patients with a low burden of eggs.

Disclosures

Dr. Geha has no disclosures. Dr. Dhaliwal reports receiving honoraria from ISMIE Mutual Insurance Company and Physicians’ Reciprocal Insurers. Dr. Peters’ spouse is employed by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Manesh is supported by the Jeremiah A. Barondess Fellowship in the Clinical Transaction of the New York Academy of Medicine, in collaboration with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

1. Sarin SK, Khanna R. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18(2):451-76. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2014.01.009. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):756-768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1610570. PubMed

3. Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.186. PubMed

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites–Schistosomiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/. Accessed December 2, 2017.

5. Bica I, Hamer DH, Stadecker MJ. Hepatic schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2000;14(3):583-604. PubMed

6. Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, et al. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1212-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. PubMed

7. Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, McManus DP. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 2011;342: 2561-2561. doi: doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2651. PubMed

8. Manzella A, Ohtomo K, Monzawa S, Lim JH. Schistosomiasis of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):144-50. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9329-7. PubMed

9. Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1106-18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PubMed

10. Blei AT, Córdoba J. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):1968. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. PubMed

1. Sarin SK, Khanna R. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18(2):451-76. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2014.01.009. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):756-768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1610570. PubMed

3. Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.186. PubMed

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites–Schistosomiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/. Accessed December 2, 2017.

5. Bica I, Hamer DH, Stadecker MJ. Hepatic schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2000;14(3):583-604. PubMed

6. Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, et al. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1212-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. PubMed

7. Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, McManus DP. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 2011;342: 2561-2561. doi: doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2651. PubMed

8. Manzella A, Ohtomo K, Monzawa S, Lim JH. Schistosomiasis of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):144-50. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9329-7. PubMed

9. Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1106-18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PubMed

10. Blei AT, Córdoba J. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):1968. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Diagnosing the Treatment

A 70-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 5 days of decreased appetite, frequent urination, tremors, and memory difficulties. He also reported 9 months of malaise, generalized weakness, and weight loss. There was no history of fever, chills, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, pain, or focal neurologic complaints.

This patient exemplifies a common clinical challenge: an older adult with several possibly unrelated concerns. In many patients, a new presentation is usually either a different manifestation of a known condition (eg, a complication of an established malignancy) or the emergence of something they are at risk for based on health behavior or other characteristics (eg, lung cancer in a smoker). The diagnostic process in older adults can be complicated because many have, or are at risk for, multiple chronic conditions.

After reviewing the timeline of symptoms, the presence of 9 months of symptoms suggests a chronic and progressive underlying process, perhaps with subsequent superimposition of an acute problem. Although it is not certain whether chronic and acute symptoms are caused by the same process, this assumption is reasonable. The superimposition of acute symptoms on a chronic process may represent progression of the underlying condition or an acute complication of the underlying disease. However, the patient’s chronic symptoms of malaise, weakness, and weight loss are nonspecific.

Although malignancy is a consideration given the age of the patient and time course of symptoms, attributing the symptoms to a specific pattern of disease or building a cogent differential diagnosis is difficult until additional information is obtained. One strategy is to try to localize the findings to 1 or more organ systems; for example, given that tremors and memory difficulties localize to the central nervous system, neurodegenerative disorders, such as “Parkinson plus” syndromes, and cerebellar disease are possible. However, this tactic still leaves a relatively broad set of symptoms without an immediate and clear unifying cause.

The patient’s medical history included hyperlipidemia, peripheral neuropathy, prostate cancer, and papillary bladder cancer. The patient was admitted to the hospital 4 months earlier for severe sepsis presumed secondary to a urinary tract infection, although bacterial cultures were sterile. His social history was notable for a 50 pack-year smoking history. Outpatient medications included alfuzosin, gabapentin, simvastatin, hydrocodone, and cholecalciferol. He used a Bright Light Therapy lamp for 1 hour per week and occasionally used calcium carbonate for indigestion. The patient’s sister had a history of throat cancer.

On examination, the patient was detected with blood pressure of 104/56 mm Hg, pulse of 85 beats per minute, temperature of 98.2 °F, oxygen saturation of 97% on ambient air, and body mass index of 18 kg/m2. The patient appeared frail with mildly decreased strength in the upper and lower extremities bilaterally. The remainder of the physical examination was normal. Reflexes were symmetric, no tremors or rigidity was noted, sensation was intact to light touch, and the response to the Romberg maneuver was normal.

Past medical history is the cornerstone of the diagnostic process. The history of 2 different malignancies is the most striking element in this case. Papillary bladder cancer is usually a local process, but additional information is needed regarding its stage and previous treatment, including whether or not the patient received Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccine, which can rarely be associated with infectious and inflammatory complications. Metastatic prostate cancer could certainly account for his symptomatology, and bladder outlet obstruction could explain the history of urinary frequency and probable urosepsis. His medication list suggested no obvious causes to explain his presentation, except that cholecalciferol and calcium carbonate, which when taken in excess, can cause hypercalcemia. This finding is of particular importance given that many of the patient’s symptoms, including polyuria, malaise, weakness, tremor, memory difficulties, anorexia, acute kidney injury and (indirectly) hypotension and weight loss, are also seen in patients with hypercalcemia. The relatively normal result of the neurologic examination decreases the probability of a primary neurologic disorder and increases the likelihood that his neurologic symptoms are due to a global systemic process. The relative hypotension and weight loss similarly support the possibility that the patient is experiencing a chronic and progressive process.

The differential diagnosis remains broad. An underlying malignancy would explain the chronic progressive course, and superimposed hypercalcemia would explain the acute symptoms of polyuria, tremor, and memory changes. Endocrinopathies including hyperthyroidism or adrenal insufficiency are other possibilities. A chronic progressive infection, such as tuberculosis, is possible, although no epidemiologic factors that increase his risk for this disease are present.

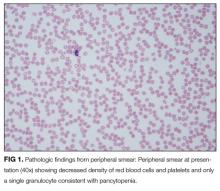

The patient had serum calcium of 14.5 mg/dL, ionized calcium of 3.46 mEq/L, albumin of 3.6 g/dL, BUN of 62 mg/dL, and creatinine of 3.9 mg/dL (all values were normal 3 months prior). His electrolytes and liver function were otherwise normal. Moreover, he had hemoglobin level of 10.5 mg/dL, white blood cell count of 4.8 × 109cells/L, and platelet count of 203 × 109 cells/L.

Until this point, only nonspecific findings were identified, leading to a broad differential diagnosis with little specificity. However, laboratory examinations confirm the suspected diagnosis of hypercalcemia, provide an opportunity to explain the patient’s symptoms, and offer a “lens” to narrow the differential diagnosis and guide the diagnostic evaluation. Hypercalcemia is most commonly secondary to primary hyperparathyroidism or malignancy. Primary hyperparathyroidism is unlikely in this patient given the relatively acute onset of symptoms. The degree of hypercalcemia is also atypical for primary hyperparathyroidism because it rarely exceeds 13 mg/dL, although the use of concurrent vitamin D and calcium supplementation could explain the high calcium level. Malignancy seems more likely given the degree of hypercalcemia in the setting of weight loss, tobacco use, and history of malignancy. Malignancy may cause hypercalcemia through multiple disparate mechanisms, including development of osteolytic bone metastases, elaboration of parathyroid hormone-related Peptide (PTHrP), increased production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, or, very rarely, ectopic production of parathyroid hormone (PTH). However, none of these mechanisms are particularly common in bladder or prostate cancer, which are the known malignancies in the patient. Other less likely and less common causes of hypercalcemia are also possible given the clinical clues, including vitamin D toxicity and milk alkali syndrome (vitamin D and calcium carbonate supplementation), multiple endocrine neoplasia (a sister with “throat cancer”), and granulomatous disease (weight loss). At this point, further laboratory evaluations would be helpful, specifically determination of PTH and PTHrP levels and serum and urine protein electrophoresis.

With respect to the patient’s past medical history, his Gleason 3 + 3 prostate cancer was diagnosed 12 years prior to admission and treated with external beam radiation therapy and brachytherapy. His bladder cancer was diagnosed 3 years before admission and treated with tumor resection followed by 2 rounds of intravesical BCG (iBCG), 1 round of mitomycin C, and 2 additional rounds of iBCG over the course of treatment spanning 2 years and 6 months. The treatment was complicated by urethral strictures requiring dilation, ureteral outlet obstruction requiring left ureteral stent placement, and multiple urinary tract infections.

The patient’s last round of iBCG was delivered 6 months prior to his current presentation. The patient’s hospital admission 4 months earlier for severe sepsis was presumed secondary to a urologic source considering that significant pyuria was noted on urinalysis and he was treated with meropenem, although bacterial cultures of blood and urine were sterile. From the time of discharge until his current presentation, he experienced progressive weakness and an approximately 50 lb weight loss.

The prior cancers and associated treatments of the patient may be involved in his current presentation. The simplest explanation would be metastatic disease with resultant hypercalcemia, which is atypical of either prostate or bladder cancer. The history of genitourinary surgery could predispose the patient to a chronic infection of the urinary tract with indolent organisms, such as a fungus, especially given the prior sepsis without clear etiology. However, the history would not explain the presence of hypercalcemia. Tuberculosis must thus be considered given the weight loss, hypercalcemia, and “sterile pyuria” of the patient. A more intriguing possibility is whether or not the patient’s constellation of signs and symptoms might be a late effect of iBCG. Intravesical BCG for treatment of localized bladder cancer is occasionally associated with complications. BCG is a modified live form of Mycobacterium bovis which invokes an intense inflammatory reaction when instilled into the bladder. These complications include disseminated infection and local complications, such as genitourinary infections. BCG infection might also explain the severe sepsis of unclear etiology that the patient had experienced 4 months earlier. Most interestingly, hypercalcemia has been described in the setting of BCG infection.

In the hospital, the patient received intravenous normal saline, furosemide, and pamidronate. Evaluation for hypercalcemia revealed appropriately suppressed PTH (8 mg/dL), and normal levels of PTHrP (<.74 pmol/L), prostate specific antigen (<.01 ng/mL), and morning cortisol (16.7 mcg/dL). Serum and urine electrophoresis did not show evidence for monoclonal gammopathy, and the 25-hydroxy vitamin D level (39.5 ng/mL) was within the normal limits

The suppressed PTH level makes primary hyperparathyroidism unlikely, the low PTHrP level decreases the probability of a paraneoplastic process, and the normal protein electrophoresis makes multiple myeloma unlikely. The presence of a significantly elevated 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D level with a normal 25-hydroxy vitamin D level indicates extrarenal conversion of 25-hydroxy vitamin D by 1-hydroxylase as the etiology of hypercalcemia.

Lymphoma would appear to be the most likely diagnosis as it accounts for most of the clinical findings observed in the patient and is a fairly common disorder. Sarcoidosis is also reasonably common and would explain the laboratory abnormalities but is not usually associated with weight loss and frailty. Disseminated infections, such as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis, are all possible, but the patient lacks key risk factors for these infections. A complication of iBCG is the most intriguing possibility and could account for many of the patient’s clinical findings, including the septic episode,

The bone survey was normal, the renal ultrasound examination showed nodular wall thickening of the bladder with areas of calcification, and the CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed an area of calcification in the superior portion of the bladder but no evidence of lymphadenopathy or masses to suggest lymphoma. Aerobic and anaerobic blood and urine cultures were sterile. The patient was discharged 12 days after admission with plans for further outpatient diagnostic evaluation. At this time, his serum calcium had stabilized at 10.5 mg/dL

DISCUSSION

Hypercalcemia is a common finding in both hospital and ambulatory settings. The classic symptoms associated with hypercalcemia are aptly summarized with the mnemonic “bones, stones, abdominal groans, and psychiatric overtones” (to represent the associated skeletal involvement, renal disease, gastrointestinal symptoms, and effects on the nervous system). However, the severity and type of symptoms vary depending on the degree of hypercalcemia, acuity of onset, and underlying etiology. The vast majority (90%) of hypercalcemia cases are due to primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy.3 Measuring the PTH level is a key step in the diagnostic evaluation process. An isolated elevation of PTH confirms the presence of primary or possibly tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Low PTH concentrations (<20 pg/mL) occur in the settings of PTHrP or vitamin-D-mediated hypercalcemia such as hypervitaminosis D, malignancy, or granulomatous disease.

Elevated PTHrP occurs most commonly in squamous cell, renal, bladder, and ovarian carcinomas.3,4 Elevated levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D can occur with excessive consumption of vitamin D-containing products and some herbal supplements. In this case, neither PTHrP nor 25-hydroxy vitamin D level was elevated, leading to an exhaustive search for other causes. Although iBCG treatment is a rare cause of hypercalcemia, 2 previous reports indicated the presence of hypercalcemia secondary to granuloma formation in treated patients.5,6

The finding of an elevated 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D level was unexpected. As the discussant mentioned, this finding is associated with lymphoma and with granulomatous disorders that were not initially strong diagnostic considerations in the patient. A variety of granulomatous diseases can cause hypercalcemia. Sarcoidosis and tuberculosis are the most common, but berylliosis, fungal infections, Crohn’s disease, silicone exposure, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis may also be associated with hypercalcemia.7 The mechanism for hypercalcemia in these situations is increased intestinal calcium absorption mediated by inappropriately increased, PTH-independent, extrarenal calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D) production. Activated monocytes upregulate 25(OH)D-alpha-hydroxylase, converting 25-hydroxy vitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D. Concurrently, the elevated levels of gamma-interferon render macrophages resistant to the normal regulatory feedback mechanisms, thereby promoting the production and inhibiting the degradation of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D.8

The tuberculosis vaccine BCG is an attenuated form of M. bovis and was originally developed by Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin at the Pasteur Institute in Paris in the early 20th century. In addition to its use as a vaccine against tuberculosis, BCG can protect against other mycobacterial infections, help treat atopic conditions via stimulation of the Th1 cellular immune response, and has been used as an antineoplastic agent. To date, BCG remains the most effective agent available for intravesical treatment of superficial bladder cancer.9,10 Although iBCG therapy is considered relatively safe and well-tolerated, rare complications do occur. Localized symptoms (bladder irritation, hematuria) and/or flu-like symptoms are common immediately after instillation and thought to be related to the cellular immune response and inflammatory cascade triggered by mycobacterial antigens.11 Other adverse effects, such as infectious and noninfectious complications, may occur months to years after treatment with BCG, and the associated symptoms can be quite nonspecific. Infectious complications include mycobacterial prostatitis, orchiepididymitis, balantitis, pneumonia, hepatitis, nephritis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, infected orthopedic and vascular prostheses, endocarditis, and bacteremia. Traumatic catheterization is the most common risk factor for infection with BCG.11-13 Noninfectious complications include reactive arthritis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), and sterile granulomatous infiltration of solid organs.

The protean and nonspecific nature of the adverse effects of iBCG treatment and the fact that complications can present weeks to years after instillation can make diagnosis quite challenging.14 Even if clinical suspicion is high, it may be difficult to definitively identify BCG as the underlying etiology because acid fast staining, culture, and even PCR can lead to falsely negative results.14,15 For this reason, biopsy and tissue culture are recommended to demonstrate granuloma formation and identify the presence of M. bovis.

Although no prospective studies have been conducted to assess the optimal therapy for BCG infection, opinion-based recommendations include cessation of BCG treatment, initiation of at least 3 tuberculostatic agents, and treatment for 3-12 months depending on the severity of the complications.11,14 M. bovis is susceptible to isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol as well as to fluoroquinolones, clarithromycin, aminoglycosides, and doxycycline; however, this organism is highly resistant to pyrazinamide due to single-point mutation.11,16

Although treatment with steroids is a standard approach for management of hypercalcemia in other granulomatous disorders and leads to rapid reduction in circulating levels of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D and serum calcium., specific evidence has not been established to support its efficacy and effectiveness in treating hypercalcemia and other complications due to M. bovis.17 Nevertheless, some experts recommend the use of steroids in conjunction with a multidrug tuberculostatic regimen in cases of septicemia and multiorgan failure due to M. bovis.12,14,18-20

In summary, this case illustrates the importance of making room in differential diagnosis to include iatrogenic complications. That is,

Teaching Points

- Complications of intravesical BCG treatment include manifestations of granulomatous diseases, such as hypercalcemia.

- When generating a differential diagnosis, medical providers should not only consider the possibility of a new disease process or the progression of a known comorbidity but also the potential of an adverse effect related to prior treatments.

- Medical providers should be wary of accepting previously made diagnoses, particularly when key pieces of objective data are lacking.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest that might bias this work.

1. Geisel RE, Sakamoto K, Russell DG, Rhoades ER. In vivo activity of released cell wall lipids of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin is due principally to trehalose mycolates. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):5007-5015. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5007. PubMed

2. Ryll R, Kumazawa Y, Yano I. Immunological properties of trehalose dimycolate (cord factor) and other mycolic acid-containing glycolipids--a review. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45(12):801-811. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb01319.x. PubMed

3. Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-1966. PubMed

4. Goldner W. Cancer-related hypercalcemia. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):426-432. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2016.011155. PubMed

5. Nayar N, Briscoe K. Systemic Bacillus Calmette-Guerin sepsis manifesting as hypercalcaemia and thrombocytopenia as a complication of intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy. Intern Med J. 2015;45(10):1091-1092. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12876. PubMed

6. Schattner A, Gilad A, Cohen J. Systemic granulomatosis and hypercalcaemia following intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guerin immunotherapy. J Intern Med. 2002;251(3):272-277. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00957.x. PubMed

7. Tebben PJ, Singh RJ, Kumar R. Vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia: mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Endocr Rev. 2016;37(5):521-547. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2016-1070. PubMed