User login

A shocking diagnosis

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 75-year-old man was brought by ambulance to the emergency department (ED) after the acute onset of palpitations, lightheadedness, and confusion. His medical history, provided by his wife, included osteoarthritis and remote cholecystectomy. He was not a smoker but drank 2 to 4 cans of beer daily. His medications were aspirin 162 mg daily and naproxen as needed. There was no history of bruising, diarrhea, melena, or bleeding.

Palpitations may represent an arrhythmia arising from an ischemic or alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Mental status changes usually have metabolic, infectious, structural (eg, hemorrhage, tumor), or toxic causes. Lightheadedness and confusion could occur with arrhythmia-associated cerebral hypoperfusion or a seizure. Daily alcohol use could cause confusion through acute intoxication, thiamine or B12 deficiency, repeated head trauma, or liver failure.

The patient’s systolic blood pressure (BP) was 60 mm Hg, heart rate (HR) was 120 beats per minute (bpm), and oral temperature was 98.4°F. Rousing him was difficult. There were no localizing neurologic abnormalities, and the rest of the physical examination findings were normal. Point-of-care blood glucose level was 155 mg/dL. Blood cultures were obtained and broad-spectrum antibiotics initiated. After fluid resuscitation, BP improved to 116/87 mm Hg, HR fell to 105 bpm, and the patient became alert and oriented. He denied chest pain, fever, or diaphoresis.

The patient’s improvement with intravenous (IV) fluids makes cardiogenic shock unlikely but does not exclude an underlying compensated cardiomyopathy that may be predisposing to arrhythmia. Hypotension, tachycardia, and somnolence may represent sepsis, but the near normalization of vital signs and mental status shortly after administration of IV fluids, the normal temperature, and the absence of localizing signs of infection favor withholding additional antibiotics. Other causes of hypotension are hypovolemia, medication effects, adrenal insufficiency, anaphylaxis, and autonomic insufficiency. There was no reported nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bleeding, polyuria, or impaired oral intake to support hypovolemia, though the response to IV fluids suggests hypovolemia may still be playing a role.

White blood cell (WBC) count was 15,450/µL with a normal differential; hemoglobin level was 15.8 g/dL; and platelet count was 176,000/µL. Electrolytes, liver function tests, cardiac enzymes, and urinalysis were normal. Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with premature atrial complexes and no ST-segment abnormalities. Radiograph of the chest and computed tomography scan of the head were normal. Echocardiogram showed moderate left ventricular hypertrophy with a normal ejection fraction and no valvular abnormalities. Exercise nuclear cardiac stress test was negative for ischemia. Blood cultures were sterile. The patient quickly became asymptomatic and remained so during his 3-day hospitalization. There were no arrhythmias on telemetry. The patient was discharged with follow-up scheduled with his primary care physician.

The nonlocalizing history and physical examination findings, normal chest radiograph and urinalysis, absence of fevers, negative blood cultures, and quick recovery make infection unlikely, despite the moderate leukocytosis. Conditions that present with acute and transient hypotension and altered mental status include arrhythmias, seizures, and reactions to drugs or toxins. Given the cardiac test results, a chronic cardiomyopathy seems unlikely, but arrhythmia is still possible. Continuous outpatient monitoring is required to assess the palpitations and the frequency of the premature atrial complexes.

Two days after discharge, the patient suddenly became diaphoretic and lost consciousness while walking to the bathroom. He was taken to the ED, where his BP was 90/60 mm Hg and HR was 108 bpm. Family members reported that he had appeared flushed during the syncopal episode, showed no seizure activity, and been unconscious for 15 to 20 minutes. The patient denied chest pain, dyspnea, fever, bowel or bladder incontinence, focal weakness, slurred speech, visual changes, nausea or vomiting either before or after the episode. Physical examination revealed a tongue laceration and facial erythema; all other findings were normal. In the ED, there was an asymptomatic 7-beat run of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, and the hypotension resolved after fluid resuscitation. The patient now reported 2 similar syncopal episodes in the past. The first occurred in a restaurant 6 years earlier, and the second occurred 3 years later, at which time he was hospitalized and no etiology was found.

The loss of consciousness is attributable to cerebral hypoperfusion. Hypotension has 3 principal categories: hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and distributive. With syncopal episodes recurring over several years, hypovolemia seems unlikely. Given the palpitations and ventricular tachycardia, it is reasonable to suspect a cardiogenic cause. Although his heart appears to be structurally normal on echocardiogram, genetic, electrophysiologic, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) testing will occasionally reveal an unsuspected substrate for arrhythmia.

The recurring yet self-limited nature, diaphoresis, flushing, and facial erythema suggest a non-sepsis distributive cause of hypotension. It is possible the patient is recurrently exposed to a toxin (eg, alcohol) that causes both flushing and dehydration. Flushing disorders include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and mastocytosis. Carcinoid syndrome is characterized by bronchospasm and diarrhea and, in some cases, right-sided valvulopathy, all of which are absent in this patient. Pheochromocytoma is associated with orthostasis, but patients typically are hypertensive at baseline. DRESS, which may arise from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or aspirin use, can cause facial erythema and swelling but is also characterized by liver, renal, and hematologic abnormalities, none of which was demonstrated. Furthermore, DRESS typically does not cause hypotension. Mastocytosis can manifest as isolated or recurrent anaphylaxis.

It is important to investigate antecedents of these syncopal episodes. If the earlier episodes were food-related—one occurred at a restaurant—then deglutition syncope (syncope precipitated by swallowing) should be considered. If an NSAID or aspirin was ingested before each episode, then medication hypersensitivity or mast cell degranulation (which can be triggered by these medications) should be further examined. Loss of consciousness lasting 20 minutes without causing any neurologic sequelae is unusual for most causes of recurrent syncope. This feature raises the possibility that a toxin or mediator might still be present in the patient’s system.

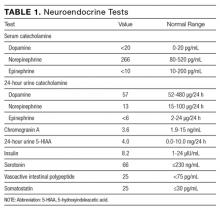

Serial cardiac enzymes and electrocardiogram were normal. A tilt-table study was negative. The cortisol response to ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation was normal. The level of serum tryptase, drawn 2 days after syncope, was 18.4 ng/dL (normal, <11.5 ng/dL). Computed tomography scan of chest and abdomen was negative for pulmonary embolism but showed a 1.4×1.3-cm hypervascular lesion in the tail of pancreas. The following neuroendocrine tests were within normal limits: serum and urine catecholamines; urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA); and serum chromogranin A, insulin, serotonin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), and somatostatin (Table 1). The patient remained asymptomatic during his hospital stay and was discharged home with appointments for cardiology follow-up and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of the pancreatic mass.

Pheochromocytoma is unlikely with normal serum and urine catecholamine levels and normal adrenal images. The differential diagnosis for a pancreatic mass includes pancreatic carcinoma, lymphoma, cystic neoplasm, and neuroendocrine tumor. All markers of neuroendocrine excess are normal, though elevations can be episodic. The normal 5-HIAA level makes carcinoid syndrome unlikely. VIPomas are associated with flushing, but the absence of profound and protracted diarrhea makes a VIPoma unlikely.

As hypoglycemia from a pancreatic insulinoma is plausible as a cause of episodic loss of consciousness lasting 15 minutes or more, it is important to inquire if giving food or drink helped resolve previous episodes. The normal insulin level reported here is of limited value, because it is the combination of insulin and C-peptide levels at time of hypoglycemia that is diagnostic. The normal glucose level recorded during one of the earlier episodes and the hypotension argue against hypoglycemia.

The elevated tryptase level is an indicator of mast cell degranulation. Tryptase levels are transiently elevated during the initial 2 to 4 hours after an anaphylactic episode and then normalize. An elevated level many hours or days later is considered a sign of mast cell excess. Although there is no evidence of the multi-organ disease (eg, cytopenia, bone disease, hepatosplenomegaly) seen in patients with a high systemic burden of mast cells, mast cell disorders exist on a spectrum. There may be a focal excess of mast cells confined to one organ or an isolated mass.

The same day as discharge, the patient’s wife drove them to the grocery store. He remained in the car while she shopped. When she returned, she found him confused and minimally responsive with subsequent brief loss of consciousness. He was taken to an ED, where he was flushed and hypotensive (systolic BP, 60 mm Hg) and tachycardic. Other examination findings were normal. After fluid resuscitation he became alert and oriented. WBC count was 20,850/μL with 89% neutrophils, hemoglobin level was 14.6 g/dL, and platelet count was 168,000/μL. Serum lactate level was 3.7 mmol/L (normal, <2.3 mmol/L). Chest radiograph was normal. He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and admitted to the hospital. Blood and urine cultures were sterile. Fine-needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass demonstrated nonspecific inflammation. Four days after admission (3 days after pancreatic mass biopsy) the patient developed palpitations, felt unwell, and had marked flushing of the face and trunk, with concomitant BP of 90/50 mm Hg and HR of 140 bpm.

The salient features of this case are recurrent hypotension, tachycardia, and flushing. Autonomic insufficiency, to which elderly patients are prone, causes hemodynamic perturbations but rarely flushing. The patient does not have diabetes mellitus, Parkinson disease, or another condition that puts him at risk for dysautonomia. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors secrete mediators that lead to vasodilation and hypotension but are unlikely given the clinical and biochemical data.

The patient’s symptoms are consistent with anaphylaxis, though prototypical immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated anaphylaxis is usually accompanied by urticaria, angioedema, and wheezing, which have been absent during his presentations. There are no clear food, pharmacologic, or environmental precipitants.

Recurrent anaphylaxis can be a manifestation of mast cell excess (eg, cutaneous or systemic mastocytosis). A markedly elevated tryptase level during an anaphylactic episode is consistent with mastocytosis or IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. An elevated baseline tryptase level days after an anaphylactic episode signals increased mast cell burden. There may be a reservoir of mast cells in the bone marrow. Alternatively, the hypervascular pancreatic mass may be a mastocytoma or a mast cell sarcoma (missed because of inadequate sampling or staining).

The lactic acidosis likely reflects global tissue hypoperfusion from vasodilatory hypotension. The leukocytosis may reflect WBC mobilization secondary to endogenous corticosteroids and catecholamines in response to hypotension or may be a direct response to the release of mast cell–derived mediators of inflammation.

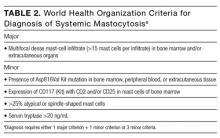

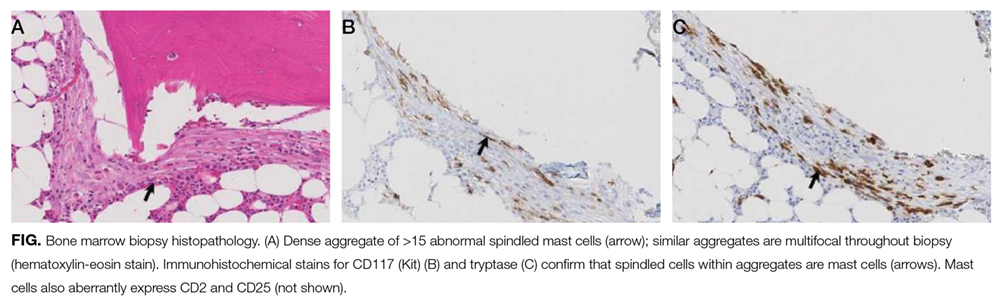

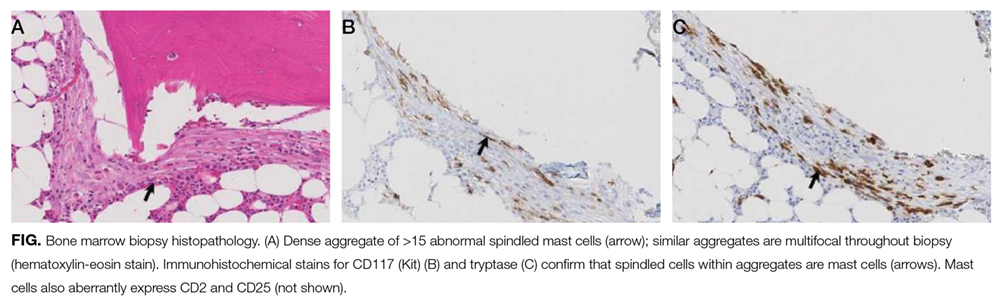

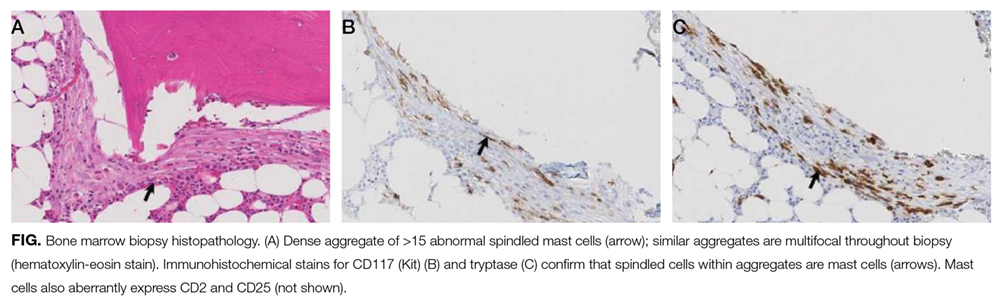

The patient was treated with diphenhydramine and ranitidine. Serum tryptase level was 46.8 ng/mL (normal, <11.5 ng/mL), and 24-hour urine histamine level was 95 µ g/dL (normal, <60 µ g/dL). Bone marrow biopsy results showed multifocal dense infiltrative aggregates of mast cells (>15 cells/aggregate), which were confirmed by CD117 (Kit) and tryptase positivity (Figure). Mutation analysis for Kit Asp816Val, which is present in 80% to 90% of patients with mastocytosis, was positive. He fulfilled the 2008 World Health Organization criteria for systemic mastocytosis (Table 2). Prednisone, histamine inhibitors, and montelukast were prescribed. Six months later, magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showed no change in the pancreatic mass, which was now characterized as a possible splenule. The patient had no additional episodes of flushing or syncope over 2 years.

DISCUSSION

Cardiovascular collapse (hypotension, tachycardia, syncope) in an elderly patient prompts clinicians to focus on life-threatening conditions, such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolus, arrhythmia, and sepsis. Each of these diagnoses was considered early in the course of this patient’s presentations, but each was deemed unlikely as it became apparent that the episodes were self-limited and recurrent over years. Incorporating flushing into the diagnostic problem representation allowed the clinicians to focus on a subset of causes of hypotension.

Flushing disorders may be classified by whether they are mediated by the autonomic nervous system (wet flushes, because they are usually accompanied by diaphoresis) or by exogenous or endogenous vasoactive substances (dry flushes).1 Autonomic nervous system flushing is triggered by emotions, fever, exercise, perimenopause (hot flashes), and neurologic conditions (eg, Parkinson disease, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis). Vasoactive flushing precipitants include drugs (eg, niacin); alcohol (secondary to cutaneous vasodilation, or acetaldehyde particularly in people with insufficient acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity)2; foods that contain capsaicin, tyramine, sulfites, or histamine (eg, eating improperly handled fish can cause scombroid poisoning); and anaphylaxis. Rare causes of vasoactive flushing include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, VIPoma, and mastocytosis.2

Mastocytosis is a rare clonal disorder characterized by the accumulation of abnormal mast cells in the skin (cutaneous mastocytosis), in multiple organs (systemic mastocytosis), or in a solid tumor (mastocytoma). Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis; it is seen more often in children than in adults and typically is associated with a maculopapular rash and dermatographism. Systemic mastocytosis is the most common form of the disorder in adults.3 Symptoms are related to mast cell infiltration or mast cell mediator–related effects, which range from itching, flushing, and diarrhea to hypotension and anaphylaxis. Other manifestations are fatigue, urticaria pigmentosa, osteoporosis, hepatosplenomegaly, bone pain, cytopenias, and lymphadenopathy.4

Systemic mastocytosis can occur at any age and should be considered in patients with recurrent unexplained flushing, syncope, or hypotension. Eighty percent to 90% of patients with systemic mastocytosis have a mutation in Kit,5 a transmembrane tyrosine kinase that is the receptor for stem cell factor. The Asp816Val mutation leads to increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis of mast cells.3,6,7 Proposed diagnostic algorithms8-11 involve measurement of serum tryptase levels and examination of bone marrow. Bone marrow biopsy and testing for the Asp816Val

The primary goals of treatment are managing mast cell–mediated symptoms and, in advanced cases, achieving cytoreduction. Alcohol can trigger mast cell degranulation in indolent systemic mastocytosis and should be avoided. Mast cell–mediated symptoms are managed with histamine blockers, leukotriene antagonists, and mast cell stabilizers.12 Targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, imatinib) in patients with transmembrane Kit mutation (eg, Phe522Cys, Lys509Ile) associated with systemic mastocytosis has had promising results.13,14 However, this patient’s Asp816Val mutation is in the Kit catalytic domain, not the transmembrane region, and therefore would not be expected to respond to imatinib. A recent open-label trial of the multikinase inhibitor midostaurin demonstrated resolution of organ damage, reduced bone marrow burden, and lowered serum tryptase levels in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis.15 Interferon, cladribine, and high-dose corticosteroids are prescribed in patients for whom other therapies have been ineffective.8

The differential diagnosis is broad for both hypotension and for flushing, but the differential diagnosis for recurrent hypotension and flushing is limited. Recognizing that flushing was an essential feature of this patient’s hypotensive condition, and not an epiphenomenon of syncope, allowed the clinicians to focus on the overlap and make a shocking diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank David Bosler, MD (Cleveland Clinic) for interpreting the pathology image.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Wilkin JK. The red face: flushing disorders. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11(2):211-223. PubMed

2. Izikson L, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. The flushing patient: differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2):193-208. PubMed

3. Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(6):435-453. PubMed

4. Hermans MA, Rietveld MJ, van Laar JA, et al. Systemic mastocytosis: a cohort study on clinical characteristics of 136 patients in a large tertiary centre. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;30:25-30. PubMed

5. Kristensen T, Vestergaard H, Bindslev-Jensen C, Møller MB, Broesby-Olsen S; Mastocytosis Centre, Odense University Hospital (MastOUH). Sensitive KIT D816V mutation analysis of blood as a diagnostic test in mastocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(5):493-498. PubMed

6. Verstovsek S. Advanced systemic mastocytosis: the impact of KIT mutations in diagnosis, treatment, and progression. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(2):89-98. PubMed

7. Garcia-Montero AC, Jara-Acevedo M, Teodosio C, et al. KIT mutation in mast cells and other bone marrow hematopoietic cell lineages in systemic mast cell disorders: a prospective study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) in a series of 113 patients. Blood. 2006;108(7):2366-2372. PubMed

8. Pardanani A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):250-262. PubMed

9. Valent P, Aberer E, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Guidelines and diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected systemic mastocytosis: a proposal of the Austrian Competence Network (AUCNM). Am J Blood Res. 2013;3(2):174-180. PubMed

10. Valent P, Escribano L, Broesby-Olsen S, et al; European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Proposed diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected mastocytosis: a proposal of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Allergy. 2014;69(10):1267-1274. PubMed

11. Akin C, Soto D, Brittain E, et al. Tryptase haplotype in mastocytosis: relationship to disease variant and diagnostic utility of total tryptase levels. Clin Immunol. 2007;123(3):268-271. PubMed

12. Theoharides TC, Valent P, Akin C. Mast cells, mastocytosis, and related disorders. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1885-1886. PubMed

13. Akin C, Fumo G, Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Neckers L, Metcalfe DD. A novel form of mastocytosis associated with a transmembrane c-kit mutation and response to imatinib. Blood. 2004;103(8):3222-3225. PubMed

14. Zhang LY, Smith ML, Schultheis B, et al. A novel K509I mutation of KIT identified in familial mastocytosis—in vitro and in vivo responsiveness to imatinib therapy. Leuk Res. 2006;30(4):373-378. PubMed

15. Gotlib J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, et al. Efficacy and safety of midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2530-2541. PubMed

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 75-year-old man was brought by ambulance to the emergency department (ED) after the acute onset of palpitations, lightheadedness, and confusion. His medical history, provided by his wife, included osteoarthritis and remote cholecystectomy. He was not a smoker but drank 2 to 4 cans of beer daily. His medications were aspirin 162 mg daily and naproxen as needed. There was no history of bruising, diarrhea, melena, or bleeding.

Palpitations may represent an arrhythmia arising from an ischemic or alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Mental status changes usually have metabolic, infectious, structural (eg, hemorrhage, tumor), or toxic causes. Lightheadedness and confusion could occur with arrhythmia-associated cerebral hypoperfusion or a seizure. Daily alcohol use could cause confusion through acute intoxication, thiamine or B12 deficiency, repeated head trauma, or liver failure.

The patient’s systolic blood pressure (BP) was 60 mm Hg, heart rate (HR) was 120 beats per minute (bpm), and oral temperature was 98.4°F. Rousing him was difficult. There were no localizing neurologic abnormalities, and the rest of the physical examination findings were normal. Point-of-care blood glucose level was 155 mg/dL. Blood cultures were obtained and broad-spectrum antibiotics initiated. After fluid resuscitation, BP improved to 116/87 mm Hg, HR fell to 105 bpm, and the patient became alert and oriented. He denied chest pain, fever, or diaphoresis.

The patient’s improvement with intravenous (IV) fluids makes cardiogenic shock unlikely but does not exclude an underlying compensated cardiomyopathy that may be predisposing to arrhythmia. Hypotension, tachycardia, and somnolence may represent sepsis, but the near normalization of vital signs and mental status shortly after administration of IV fluids, the normal temperature, and the absence of localizing signs of infection favor withholding additional antibiotics. Other causes of hypotension are hypovolemia, medication effects, adrenal insufficiency, anaphylaxis, and autonomic insufficiency. There was no reported nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bleeding, polyuria, or impaired oral intake to support hypovolemia, though the response to IV fluids suggests hypovolemia may still be playing a role.

White blood cell (WBC) count was 15,450/µL with a normal differential; hemoglobin level was 15.8 g/dL; and platelet count was 176,000/µL. Electrolytes, liver function tests, cardiac enzymes, and urinalysis were normal. Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with premature atrial complexes and no ST-segment abnormalities. Radiograph of the chest and computed tomography scan of the head were normal. Echocardiogram showed moderate left ventricular hypertrophy with a normal ejection fraction and no valvular abnormalities. Exercise nuclear cardiac stress test was negative for ischemia. Blood cultures were sterile. The patient quickly became asymptomatic and remained so during his 3-day hospitalization. There were no arrhythmias on telemetry. The patient was discharged with follow-up scheduled with his primary care physician.

The nonlocalizing history and physical examination findings, normal chest radiograph and urinalysis, absence of fevers, negative blood cultures, and quick recovery make infection unlikely, despite the moderate leukocytosis. Conditions that present with acute and transient hypotension and altered mental status include arrhythmias, seizures, and reactions to drugs or toxins. Given the cardiac test results, a chronic cardiomyopathy seems unlikely, but arrhythmia is still possible. Continuous outpatient monitoring is required to assess the palpitations and the frequency of the premature atrial complexes.

Two days after discharge, the patient suddenly became diaphoretic and lost consciousness while walking to the bathroom. He was taken to the ED, where his BP was 90/60 mm Hg and HR was 108 bpm. Family members reported that he had appeared flushed during the syncopal episode, showed no seizure activity, and been unconscious for 15 to 20 minutes. The patient denied chest pain, dyspnea, fever, bowel or bladder incontinence, focal weakness, slurred speech, visual changes, nausea or vomiting either before or after the episode. Physical examination revealed a tongue laceration and facial erythema; all other findings were normal. In the ED, there was an asymptomatic 7-beat run of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, and the hypotension resolved after fluid resuscitation. The patient now reported 2 similar syncopal episodes in the past. The first occurred in a restaurant 6 years earlier, and the second occurred 3 years later, at which time he was hospitalized and no etiology was found.

The loss of consciousness is attributable to cerebral hypoperfusion. Hypotension has 3 principal categories: hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and distributive. With syncopal episodes recurring over several years, hypovolemia seems unlikely. Given the palpitations and ventricular tachycardia, it is reasonable to suspect a cardiogenic cause. Although his heart appears to be structurally normal on echocardiogram, genetic, electrophysiologic, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) testing will occasionally reveal an unsuspected substrate for arrhythmia.

The recurring yet self-limited nature, diaphoresis, flushing, and facial erythema suggest a non-sepsis distributive cause of hypotension. It is possible the patient is recurrently exposed to a toxin (eg, alcohol) that causes both flushing and dehydration. Flushing disorders include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and mastocytosis. Carcinoid syndrome is characterized by bronchospasm and diarrhea and, in some cases, right-sided valvulopathy, all of which are absent in this patient. Pheochromocytoma is associated with orthostasis, but patients typically are hypertensive at baseline. DRESS, which may arise from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or aspirin use, can cause facial erythema and swelling but is also characterized by liver, renal, and hematologic abnormalities, none of which was demonstrated. Furthermore, DRESS typically does not cause hypotension. Mastocytosis can manifest as isolated or recurrent anaphylaxis.

It is important to investigate antecedents of these syncopal episodes. If the earlier episodes were food-related—one occurred at a restaurant—then deglutition syncope (syncope precipitated by swallowing) should be considered. If an NSAID or aspirin was ingested before each episode, then medication hypersensitivity or mast cell degranulation (which can be triggered by these medications) should be further examined. Loss of consciousness lasting 20 minutes without causing any neurologic sequelae is unusual for most causes of recurrent syncope. This feature raises the possibility that a toxin or mediator might still be present in the patient’s system.

Serial cardiac enzymes and electrocardiogram were normal. A tilt-table study was negative. The cortisol response to ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation was normal. The level of serum tryptase, drawn 2 days after syncope, was 18.4 ng/dL (normal, <11.5 ng/dL). Computed tomography scan of chest and abdomen was negative for pulmonary embolism but showed a 1.4×1.3-cm hypervascular lesion in the tail of pancreas. The following neuroendocrine tests were within normal limits: serum and urine catecholamines; urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA); and serum chromogranin A, insulin, serotonin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), and somatostatin (Table 1). The patient remained asymptomatic during his hospital stay and was discharged home with appointments for cardiology follow-up and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of the pancreatic mass.

Pheochromocytoma is unlikely with normal serum and urine catecholamine levels and normal adrenal images. The differential diagnosis for a pancreatic mass includes pancreatic carcinoma, lymphoma, cystic neoplasm, and neuroendocrine tumor. All markers of neuroendocrine excess are normal, though elevations can be episodic. The normal 5-HIAA level makes carcinoid syndrome unlikely. VIPomas are associated with flushing, but the absence of profound and protracted diarrhea makes a VIPoma unlikely.

As hypoglycemia from a pancreatic insulinoma is plausible as a cause of episodic loss of consciousness lasting 15 minutes or more, it is important to inquire if giving food or drink helped resolve previous episodes. The normal insulin level reported here is of limited value, because it is the combination of insulin and C-peptide levels at time of hypoglycemia that is diagnostic. The normal glucose level recorded during one of the earlier episodes and the hypotension argue against hypoglycemia.

The elevated tryptase level is an indicator of mast cell degranulation. Tryptase levels are transiently elevated during the initial 2 to 4 hours after an anaphylactic episode and then normalize. An elevated level many hours or days later is considered a sign of mast cell excess. Although there is no evidence of the multi-organ disease (eg, cytopenia, bone disease, hepatosplenomegaly) seen in patients with a high systemic burden of mast cells, mast cell disorders exist on a spectrum. There may be a focal excess of mast cells confined to one organ or an isolated mass.

The same day as discharge, the patient’s wife drove them to the grocery store. He remained in the car while she shopped. When she returned, she found him confused and minimally responsive with subsequent brief loss of consciousness. He was taken to an ED, where he was flushed and hypotensive (systolic BP, 60 mm Hg) and tachycardic. Other examination findings were normal. After fluid resuscitation he became alert and oriented. WBC count was 20,850/μL with 89% neutrophils, hemoglobin level was 14.6 g/dL, and platelet count was 168,000/μL. Serum lactate level was 3.7 mmol/L (normal, <2.3 mmol/L). Chest radiograph was normal. He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and admitted to the hospital. Blood and urine cultures were sterile. Fine-needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass demonstrated nonspecific inflammation. Four days after admission (3 days after pancreatic mass biopsy) the patient developed palpitations, felt unwell, and had marked flushing of the face and trunk, with concomitant BP of 90/50 mm Hg and HR of 140 bpm.

The salient features of this case are recurrent hypotension, tachycardia, and flushing. Autonomic insufficiency, to which elderly patients are prone, causes hemodynamic perturbations but rarely flushing. The patient does not have diabetes mellitus, Parkinson disease, or another condition that puts him at risk for dysautonomia. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors secrete mediators that lead to vasodilation and hypotension but are unlikely given the clinical and biochemical data.

The patient’s symptoms are consistent with anaphylaxis, though prototypical immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated anaphylaxis is usually accompanied by urticaria, angioedema, and wheezing, which have been absent during his presentations. There are no clear food, pharmacologic, or environmental precipitants.

Recurrent anaphylaxis can be a manifestation of mast cell excess (eg, cutaneous or systemic mastocytosis). A markedly elevated tryptase level during an anaphylactic episode is consistent with mastocytosis or IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. An elevated baseline tryptase level days after an anaphylactic episode signals increased mast cell burden. There may be a reservoir of mast cells in the bone marrow. Alternatively, the hypervascular pancreatic mass may be a mastocytoma or a mast cell sarcoma (missed because of inadequate sampling or staining).

The lactic acidosis likely reflects global tissue hypoperfusion from vasodilatory hypotension. The leukocytosis may reflect WBC mobilization secondary to endogenous corticosteroids and catecholamines in response to hypotension or may be a direct response to the release of mast cell–derived mediators of inflammation.

The patient was treated with diphenhydramine and ranitidine. Serum tryptase level was 46.8 ng/mL (normal, <11.5 ng/mL), and 24-hour urine histamine level was 95 µ g/dL (normal, <60 µ g/dL). Bone marrow biopsy results showed multifocal dense infiltrative aggregates of mast cells (>15 cells/aggregate), which were confirmed by CD117 (Kit) and tryptase positivity (Figure). Mutation analysis for Kit Asp816Val, which is present in 80% to 90% of patients with mastocytosis, was positive. He fulfilled the 2008 World Health Organization criteria for systemic mastocytosis (Table 2). Prednisone, histamine inhibitors, and montelukast were prescribed. Six months later, magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showed no change in the pancreatic mass, which was now characterized as a possible splenule. The patient had no additional episodes of flushing or syncope over 2 years.

DISCUSSION

Cardiovascular collapse (hypotension, tachycardia, syncope) in an elderly patient prompts clinicians to focus on life-threatening conditions, such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolus, arrhythmia, and sepsis. Each of these diagnoses was considered early in the course of this patient’s presentations, but each was deemed unlikely as it became apparent that the episodes were self-limited and recurrent over years. Incorporating flushing into the diagnostic problem representation allowed the clinicians to focus on a subset of causes of hypotension.

Flushing disorders may be classified by whether they are mediated by the autonomic nervous system (wet flushes, because they are usually accompanied by diaphoresis) or by exogenous or endogenous vasoactive substances (dry flushes).1 Autonomic nervous system flushing is triggered by emotions, fever, exercise, perimenopause (hot flashes), and neurologic conditions (eg, Parkinson disease, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis). Vasoactive flushing precipitants include drugs (eg, niacin); alcohol (secondary to cutaneous vasodilation, or acetaldehyde particularly in people with insufficient acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity)2; foods that contain capsaicin, tyramine, sulfites, or histamine (eg, eating improperly handled fish can cause scombroid poisoning); and anaphylaxis. Rare causes of vasoactive flushing include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, VIPoma, and mastocytosis.2

Mastocytosis is a rare clonal disorder characterized by the accumulation of abnormal mast cells in the skin (cutaneous mastocytosis), in multiple organs (systemic mastocytosis), or in a solid tumor (mastocytoma). Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis; it is seen more often in children than in adults and typically is associated with a maculopapular rash and dermatographism. Systemic mastocytosis is the most common form of the disorder in adults.3 Symptoms are related to mast cell infiltration or mast cell mediator–related effects, which range from itching, flushing, and diarrhea to hypotension and anaphylaxis. Other manifestations are fatigue, urticaria pigmentosa, osteoporosis, hepatosplenomegaly, bone pain, cytopenias, and lymphadenopathy.4

Systemic mastocytosis can occur at any age and should be considered in patients with recurrent unexplained flushing, syncope, or hypotension. Eighty percent to 90% of patients with systemic mastocytosis have a mutation in Kit,5 a transmembrane tyrosine kinase that is the receptor for stem cell factor. The Asp816Val mutation leads to increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis of mast cells.3,6,7 Proposed diagnostic algorithms8-11 involve measurement of serum tryptase levels and examination of bone marrow. Bone marrow biopsy and testing for the Asp816Val

The primary goals of treatment are managing mast cell–mediated symptoms and, in advanced cases, achieving cytoreduction. Alcohol can trigger mast cell degranulation in indolent systemic mastocytosis and should be avoided. Mast cell–mediated symptoms are managed with histamine blockers, leukotriene antagonists, and mast cell stabilizers.12 Targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, imatinib) in patients with transmembrane Kit mutation (eg, Phe522Cys, Lys509Ile) associated with systemic mastocytosis has had promising results.13,14 However, this patient’s Asp816Val mutation is in the Kit catalytic domain, not the transmembrane region, and therefore would not be expected to respond to imatinib. A recent open-label trial of the multikinase inhibitor midostaurin demonstrated resolution of organ damage, reduced bone marrow burden, and lowered serum tryptase levels in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis.15 Interferon, cladribine, and high-dose corticosteroids are prescribed in patients for whom other therapies have been ineffective.8

The differential diagnosis is broad for both hypotension and for flushing, but the differential diagnosis for recurrent hypotension and flushing is limited. Recognizing that flushing was an essential feature of this patient’s hypotensive condition, and not an epiphenomenon of syncope, allowed the clinicians to focus on the overlap and make a shocking diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank David Bosler, MD (Cleveland Clinic) for interpreting the pathology image.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 75-year-old man was brought by ambulance to the emergency department (ED) after the acute onset of palpitations, lightheadedness, and confusion. His medical history, provided by his wife, included osteoarthritis and remote cholecystectomy. He was not a smoker but drank 2 to 4 cans of beer daily. His medications were aspirin 162 mg daily and naproxen as needed. There was no history of bruising, diarrhea, melena, or bleeding.

Palpitations may represent an arrhythmia arising from an ischemic or alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Mental status changes usually have metabolic, infectious, structural (eg, hemorrhage, tumor), or toxic causes. Lightheadedness and confusion could occur with arrhythmia-associated cerebral hypoperfusion or a seizure. Daily alcohol use could cause confusion through acute intoxication, thiamine or B12 deficiency, repeated head trauma, or liver failure.

The patient’s systolic blood pressure (BP) was 60 mm Hg, heart rate (HR) was 120 beats per minute (bpm), and oral temperature was 98.4°F. Rousing him was difficult. There were no localizing neurologic abnormalities, and the rest of the physical examination findings were normal. Point-of-care blood glucose level was 155 mg/dL. Blood cultures were obtained and broad-spectrum antibiotics initiated. After fluid resuscitation, BP improved to 116/87 mm Hg, HR fell to 105 bpm, and the patient became alert and oriented. He denied chest pain, fever, or diaphoresis.

The patient’s improvement with intravenous (IV) fluids makes cardiogenic shock unlikely but does not exclude an underlying compensated cardiomyopathy that may be predisposing to arrhythmia. Hypotension, tachycardia, and somnolence may represent sepsis, but the near normalization of vital signs and mental status shortly after administration of IV fluids, the normal temperature, and the absence of localizing signs of infection favor withholding additional antibiotics. Other causes of hypotension are hypovolemia, medication effects, adrenal insufficiency, anaphylaxis, and autonomic insufficiency. There was no reported nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bleeding, polyuria, or impaired oral intake to support hypovolemia, though the response to IV fluids suggests hypovolemia may still be playing a role.

White blood cell (WBC) count was 15,450/µL with a normal differential; hemoglobin level was 15.8 g/dL; and platelet count was 176,000/µL. Electrolytes, liver function tests, cardiac enzymes, and urinalysis were normal. Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with premature atrial complexes and no ST-segment abnormalities. Radiograph of the chest and computed tomography scan of the head were normal. Echocardiogram showed moderate left ventricular hypertrophy with a normal ejection fraction and no valvular abnormalities. Exercise nuclear cardiac stress test was negative for ischemia. Blood cultures were sterile. The patient quickly became asymptomatic and remained so during his 3-day hospitalization. There were no arrhythmias on telemetry. The patient was discharged with follow-up scheduled with his primary care physician.

The nonlocalizing history and physical examination findings, normal chest radiograph and urinalysis, absence of fevers, negative blood cultures, and quick recovery make infection unlikely, despite the moderate leukocytosis. Conditions that present with acute and transient hypotension and altered mental status include arrhythmias, seizures, and reactions to drugs or toxins. Given the cardiac test results, a chronic cardiomyopathy seems unlikely, but arrhythmia is still possible. Continuous outpatient monitoring is required to assess the palpitations and the frequency of the premature atrial complexes.

Two days after discharge, the patient suddenly became diaphoretic and lost consciousness while walking to the bathroom. He was taken to the ED, where his BP was 90/60 mm Hg and HR was 108 bpm. Family members reported that he had appeared flushed during the syncopal episode, showed no seizure activity, and been unconscious for 15 to 20 minutes. The patient denied chest pain, dyspnea, fever, bowel or bladder incontinence, focal weakness, slurred speech, visual changes, nausea or vomiting either before or after the episode. Physical examination revealed a tongue laceration and facial erythema; all other findings were normal. In the ED, there was an asymptomatic 7-beat run of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, and the hypotension resolved after fluid resuscitation. The patient now reported 2 similar syncopal episodes in the past. The first occurred in a restaurant 6 years earlier, and the second occurred 3 years later, at which time he was hospitalized and no etiology was found.

The loss of consciousness is attributable to cerebral hypoperfusion. Hypotension has 3 principal categories: hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and distributive. With syncopal episodes recurring over several years, hypovolemia seems unlikely. Given the palpitations and ventricular tachycardia, it is reasonable to suspect a cardiogenic cause. Although his heart appears to be structurally normal on echocardiogram, genetic, electrophysiologic, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) testing will occasionally reveal an unsuspected substrate for arrhythmia.

The recurring yet self-limited nature, diaphoresis, flushing, and facial erythema suggest a non-sepsis distributive cause of hypotension. It is possible the patient is recurrently exposed to a toxin (eg, alcohol) that causes both flushing and dehydration. Flushing disorders include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and mastocytosis. Carcinoid syndrome is characterized by bronchospasm and diarrhea and, in some cases, right-sided valvulopathy, all of which are absent in this patient. Pheochromocytoma is associated with orthostasis, but patients typically are hypertensive at baseline. DRESS, which may arise from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or aspirin use, can cause facial erythema and swelling but is also characterized by liver, renal, and hematologic abnormalities, none of which was demonstrated. Furthermore, DRESS typically does not cause hypotension. Mastocytosis can manifest as isolated or recurrent anaphylaxis.

It is important to investigate antecedents of these syncopal episodes. If the earlier episodes were food-related—one occurred at a restaurant—then deglutition syncope (syncope precipitated by swallowing) should be considered. If an NSAID or aspirin was ingested before each episode, then medication hypersensitivity or mast cell degranulation (which can be triggered by these medications) should be further examined. Loss of consciousness lasting 20 minutes without causing any neurologic sequelae is unusual for most causes of recurrent syncope. This feature raises the possibility that a toxin or mediator might still be present in the patient’s system.

Serial cardiac enzymes and electrocardiogram were normal. A tilt-table study was negative. The cortisol response to ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation was normal. The level of serum tryptase, drawn 2 days after syncope, was 18.4 ng/dL (normal, <11.5 ng/dL). Computed tomography scan of chest and abdomen was negative for pulmonary embolism but showed a 1.4×1.3-cm hypervascular lesion in the tail of pancreas. The following neuroendocrine tests were within normal limits: serum and urine catecholamines; urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA); and serum chromogranin A, insulin, serotonin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), and somatostatin (Table 1). The patient remained asymptomatic during his hospital stay and was discharged home with appointments for cardiology follow-up and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of the pancreatic mass.

Pheochromocytoma is unlikely with normal serum and urine catecholamine levels and normal adrenal images. The differential diagnosis for a pancreatic mass includes pancreatic carcinoma, lymphoma, cystic neoplasm, and neuroendocrine tumor. All markers of neuroendocrine excess are normal, though elevations can be episodic. The normal 5-HIAA level makes carcinoid syndrome unlikely. VIPomas are associated with flushing, but the absence of profound and protracted diarrhea makes a VIPoma unlikely.

As hypoglycemia from a pancreatic insulinoma is plausible as a cause of episodic loss of consciousness lasting 15 minutes or more, it is important to inquire if giving food or drink helped resolve previous episodes. The normal insulin level reported here is of limited value, because it is the combination of insulin and C-peptide levels at time of hypoglycemia that is diagnostic. The normal glucose level recorded during one of the earlier episodes and the hypotension argue against hypoglycemia.

The elevated tryptase level is an indicator of mast cell degranulation. Tryptase levels are transiently elevated during the initial 2 to 4 hours after an anaphylactic episode and then normalize. An elevated level many hours or days later is considered a sign of mast cell excess. Although there is no evidence of the multi-organ disease (eg, cytopenia, bone disease, hepatosplenomegaly) seen in patients with a high systemic burden of mast cells, mast cell disorders exist on a spectrum. There may be a focal excess of mast cells confined to one organ or an isolated mass.

The same day as discharge, the patient’s wife drove them to the grocery store. He remained in the car while she shopped. When she returned, she found him confused and minimally responsive with subsequent brief loss of consciousness. He was taken to an ED, where he was flushed and hypotensive (systolic BP, 60 mm Hg) and tachycardic. Other examination findings were normal. After fluid resuscitation he became alert and oriented. WBC count was 20,850/μL with 89% neutrophils, hemoglobin level was 14.6 g/dL, and platelet count was 168,000/μL. Serum lactate level was 3.7 mmol/L (normal, <2.3 mmol/L). Chest radiograph was normal. He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and admitted to the hospital. Blood and urine cultures were sterile. Fine-needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass demonstrated nonspecific inflammation. Four days after admission (3 days after pancreatic mass biopsy) the patient developed palpitations, felt unwell, and had marked flushing of the face and trunk, with concomitant BP of 90/50 mm Hg and HR of 140 bpm.

The salient features of this case are recurrent hypotension, tachycardia, and flushing. Autonomic insufficiency, to which elderly patients are prone, causes hemodynamic perturbations but rarely flushing. The patient does not have diabetes mellitus, Parkinson disease, or another condition that puts him at risk for dysautonomia. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors secrete mediators that lead to vasodilation and hypotension but are unlikely given the clinical and biochemical data.

The patient’s symptoms are consistent with anaphylaxis, though prototypical immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated anaphylaxis is usually accompanied by urticaria, angioedema, and wheezing, which have been absent during his presentations. There are no clear food, pharmacologic, or environmental precipitants.

Recurrent anaphylaxis can be a manifestation of mast cell excess (eg, cutaneous or systemic mastocytosis). A markedly elevated tryptase level during an anaphylactic episode is consistent with mastocytosis or IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. An elevated baseline tryptase level days after an anaphylactic episode signals increased mast cell burden. There may be a reservoir of mast cells in the bone marrow. Alternatively, the hypervascular pancreatic mass may be a mastocytoma or a mast cell sarcoma (missed because of inadequate sampling or staining).

The lactic acidosis likely reflects global tissue hypoperfusion from vasodilatory hypotension. The leukocytosis may reflect WBC mobilization secondary to endogenous corticosteroids and catecholamines in response to hypotension or may be a direct response to the release of mast cell–derived mediators of inflammation.

The patient was treated with diphenhydramine and ranitidine. Serum tryptase level was 46.8 ng/mL (normal, <11.5 ng/mL), and 24-hour urine histamine level was 95 µ g/dL (normal, <60 µ g/dL). Bone marrow biopsy results showed multifocal dense infiltrative aggregates of mast cells (>15 cells/aggregate), which were confirmed by CD117 (Kit) and tryptase positivity (Figure). Mutation analysis for Kit Asp816Val, which is present in 80% to 90% of patients with mastocytosis, was positive. He fulfilled the 2008 World Health Organization criteria for systemic mastocytosis (Table 2). Prednisone, histamine inhibitors, and montelukast were prescribed. Six months later, magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showed no change in the pancreatic mass, which was now characterized as a possible splenule. The patient had no additional episodes of flushing or syncope over 2 years.

DISCUSSION

Cardiovascular collapse (hypotension, tachycardia, syncope) in an elderly patient prompts clinicians to focus on life-threatening conditions, such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolus, arrhythmia, and sepsis. Each of these diagnoses was considered early in the course of this patient’s presentations, but each was deemed unlikely as it became apparent that the episodes were self-limited and recurrent over years. Incorporating flushing into the diagnostic problem representation allowed the clinicians to focus on a subset of causes of hypotension.

Flushing disorders may be classified by whether they are mediated by the autonomic nervous system (wet flushes, because they are usually accompanied by diaphoresis) or by exogenous or endogenous vasoactive substances (dry flushes).1 Autonomic nervous system flushing is triggered by emotions, fever, exercise, perimenopause (hot flashes), and neurologic conditions (eg, Parkinson disease, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis). Vasoactive flushing precipitants include drugs (eg, niacin); alcohol (secondary to cutaneous vasodilation, or acetaldehyde particularly in people with insufficient acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity)2; foods that contain capsaicin, tyramine, sulfites, or histamine (eg, eating improperly handled fish can cause scombroid poisoning); and anaphylaxis. Rare causes of vasoactive flushing include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, VIPoma, and mastocytosis.2

Mastocytosis is a rare clonal disorder characterized by the accumulation of abnormal mast cells in the skin (cutaneous mastocytosis), in multiple organs (systemic mastocytosis), or in a solid tumor (mastocytoma). Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis; it is seen more often in children than in adults and typically is associated with a maculopapular rash and dermatographism. Systemic mastocytosis is the most common form of the disorder in adults.3 Symptoms are related to mast cell infiltration or mast cell mediator–related effects, which range from itching, flushing, and diarrhea to hypotension and anaphylaxis. Other manifestations are fatigue, urticaria pigmentosa, osteoporosis, hepatosplenomegaly, bone pain, cytopenias, and lymphadenopathy.4

Systemic mastocytosis can occur at any age and should be considered in patients with recurrent unexplained flushing, syncope, or hypotension. Eighty percent to 90% of patients with systemic mastocytosis have a mutation in Kit,5 a transmembrane tyrosine kinase that is the receptor for stem cell factor. The Asp816Val mutation leads to increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis of mast cells.3,6,7 Proposed diagnostic algorithms8-11 involve measurement of serum tryptase levels and examination of bone marrow. Bone marrow biopsy and testing for the Asp816Val

The primary goals of treatment are managing mast cell–mediated symptoms and, in advanced cases, achieving cytoreduction. Alcohol can trigger mast cell degranulation in indolent systemic mastocytosis and should be avoided. Mast cell–mediated symptoms are managed with histamine blockers, leukotriene antagonists, and mast cell stabilizers.12 Targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, imatinib) in patients with transmembrane Kit mutation (eg, Phe522Cys, Lys509Ile) associated with systemic mastocytosis has had promising results.13,14 However, this patient’s Asp816Val mutation is in the Kit catalytic domain, not the transmembrane region, and therefore would not be expected to respond to imatinib. A recent open-label trial of the multikinase inhibitor midostaurin demonstrated resolution of organ damage, reduced bone marrow burden, and lowered serum tryptase levels in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis.15 Interferon, cladribine, and high-dose corticosteroids are prescribed in patients for whom other therapies have been ineffective.8

The differential diagnosis is broad for both hypotension and for flushing, but the differential diagnosis for recurrent hypotension and flushing is limited. Recognizing that flushing was an essential feature of this patient’s hypotensive condition, and not an epiphenomenon of syncope, allowed the clinicians to focus on the overlap and make a shocking diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank David Bosler, MD (Cleveland Clinic) for interpreting the pathology image.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Wilkin JK. The red face: flushing disorders. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11(2):211-223. PubMed

2. Izikson L, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. The flushing patient: differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2):193-208. PubMed

3. Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(6):435-453. PubMed

4. Hermans MA, Rietveld MJ, van Laar JA, et al. Systemic mastocytosis: a cohort study on clinical characteristics of 136 patients in a large tertiary centre. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;30:25-30. PubMed

5. Kristensen T, Vestergaard H, Bindslev-Jensen C, Møller MB, Broesby-Olsen S; Mastocytosis Centre, Odense University Hospital (MastOUH). Sensitive KIT D816V mutation analysis of blood as a diagnostic test in mastocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(5):493-498. PubMed

6. Verstovsek S. Advanced systemic mastocytosis: the impact of KIT mutations in diagnosis, treatment, and progression. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(2):89-98. PubMed

7. Garcia-Montero AC, Jara-Acevedo M, Teodosio C, et al. KIT mutation in mast cells and other bone marrow hematopoietic cell lineages in systemic mast cell disorders: a prospective study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) in a series of 113 patients. Blood. 2006;108(7):2366-2372. PubMed

8. Pardanani A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):250-262. PubMed

9. Valent P, Aberer E, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Guidelines and diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected systemic mastocytosis: a proposal of the Austrian Competence Network (AUCNM). Am J Blood Res. 2013;3(2):174-180. PubMed

10. Valent P, Escribano L, Broesby-Olsen S, et al; European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Proposed diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected mastocytosis: a proposal of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Allergy. 2014;69(10):1267-1274. PubMed

11. Akin C, Soto D, Brittain E, et al. Tryptase haplotype in mastocytosis: relationship to disease variant and diagnostic utility of total tryptase levels. Clin Immunol. 2007;123(3):268-271. PubMed

12. Theoharides TC, Valent P, Akin C. Mast cells, mastocytosis, and related disorders. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1885-1886. PubMed

13. Akin C, Fumo G, Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Neckers L, Metcalfe DD. A novel form of mastocytosis associated with a transmembrane c-kit mutation and response to imatinib. Blood. 2004;103(8):3222-3225. PubMed

14. Zhang LY, Smith ML, Schultheis B, et al. A novel K509I mutation of KIT identified in familial mastocytosis—in vitro and in vivo responsiveness to imatinib therapy. Leuk Res. 2006;30(4):373-378. PubMed

15. Gotlib J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, et al. Efficacy and safety of midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2530-2541. PubMed

1. Wilkin JK. The red face: flushing disorders. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11(2):211-223. PubMed

2. Izikson L, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. The flushing patient: differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2):193-208. PubMed

3. Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(6):435-453. PubMed

4. Hermans MA, Rietveld MJ, van Laar JA, et al. Systemic mastocytosis: a cohort study on clinical characteristics of 136 patients in a large tertiary centre. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;30:25-30. PubMed

5. Kristensen T, Vestergaard H, Bindslev-Jensen C, Møller MB, Broesby-Olsen S; Mastocytosis Centre, Odense University Hospital (MastOUH). Sensitive KIT D816V mutation analysis of blood as a diagnostic test in mastocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(5):493-498. PubMed

6. Verstovsek S. Advanced systemic mastocytosis: the impact of KIT mutations in diagnosis, treatment, and progression. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(2):89-98. PubMed

7. Garcia-Montero AC, Jara-Acevedo M, Teodosio C, et al. KIT mutation in mast cells and other bone marrow hematopoietic cell lineages in systemic mast cell disorders: a prospective study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) in a series of 113 patients. Blood. 2006;108(7):2366-2372. PubMed

8. Pardanani A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):250-262. PubMed

9. Valent P, Aberer E, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Guidelines and diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected systemic mastocytosis: a proposal of the Austrian Competence Network (AUCNM). Am J Blood Res. 2013;3(2):174-180. PubMed

10. Valent P, Escribano L, Broesby-Olsen S, et al; European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Proposed diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected mastocytosis: a proposal of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Allergy. 2014;69(10):1267-1274. PubMed

11. Akin C, Soto D, Brittain E, et al. Tryptase haplotype in mastocytosis: relationship to disease variant and diagnostic utility of total tryptase levels. Clin Immunol. 2007;123(3):268-271. PubMed

12. Theoharides TC, Valent P, Akin C. Mast cells, mastocytosis, and related disorders. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1885-1886. PubMed

13. Akin C, Fumo G, Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Neckers L, Metcalfe DD. A novel form of mastocytosis associated with a transmembrane c-kit mutation and response to imatinib. Blood. 2004;103(8):3222-3225. PubMed

14. Zhang LY, Smith ML, Schultheis B, et al. A novel K509I mutation of KIT identified in familial mastocytosis—in vitro and in vivo responsiveness to imatinib therapy. Leuk Res. 2006;30(4):373-378. PubMed

15. Gotlib J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, et al. Efficacy and safety of midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2530-2541. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Getting Warmer

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 3-month-old otherwise healthy, immunized female presented to clinic with 2 days of intermittent low-grade fevers (maximum, 100º F), decreased oral intake, and sleepiness. Her pediatrician noted a faint, maculopapular rash on her trunk and extremities with mild conjunctival injection bilaterally that appeared that day, according to her mother. The infant otherwise appeared alert, well-hydrated, and without respiratory distress. She had no history of sick contacts or recent travel. She was prescribed amoxicillin for empiric treatment of a possible bacterial sinusitis or pharyngitis, despite a negative rapid strep antigen test.

At this age, multiple conditions can cause rashes. Given that this is early in the course of illness, without focal symptoms but with low-grade fevers, the initial differential diagnosis is broad and would include infectious, rheumatologic, and hematologic-oncologic etiologies, although the latter would be less likely. While the patient’s mother reports decreased oral intake, the fact that the patient is alert and appears hydrated is encouraging, suggesting time to observe and see if other symptoms present that may assist in elucidating the cause. The history of increased sleepiness warrants further investigation of meningeal signs, which would point to a central nervous system infection.

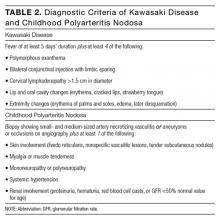

While streptococcal infection is possible, it would be uncommon at this age. The patient would have a higher fever and focal infection, and the rash does not appear consistent unless it was described as “sandpaper” in feel and appearance. A negative rapid strep test, while not sensitive, further supports this impression. A low-grade fever and rash would be consistent with a viral syndrome and, given the conjunctival injection, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, rhinovirus, and Epstein Barr virus (EBV) are possibilities. Without ocular discharge, bacterial conjunctivitis would be unlikely. Another consideration would be Kawasaki disease, though it would be too early to diagnose this condition since at least 5 days of fever are required. Next steps include a detailed physical examination, looking for other focal signs such as swelling or desquamation of hands and feet, lymphadenopathy, strawberry tongue, and mucositis. Rather than empirically starting antibiotics, it would be more reasonable to observe her with close outpatient follow-up. The patient’s family should be instructed to monitor for additional and/or worsening symptoms, further decreased oral intake, signs of dehydration, or changes in alertness.

At home, the patient completed 5 doses of amoxicillin but continued to be febrile (maximum, 102.6º F). She was taken to a local emergency department on day 6 of her illness. She had worsening conjunctival injection and progression of the rash, involving the palms and soles. She was noted to have edema of hands and feet without desquamation (Figure 1). She had no oral mucous membrane changes and no cervical lymphadenopathy. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was unremarkable, and empiric treatment with intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone was initiated. Complete blood count was notable for a white blood cell (WBC) count of 18.9 k/μL (normal range, 6.0-17.0); hemoglobin, 7.6 g/dL (normal range, 10-13); mean corpuscular volume, 84 (normal range, 74-108); and platelet count, 105 k/μL (normal range, 150-400). A peripheral blood smear revealed no abnormal cells. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 6.5 mg/dL (normal range, 0.0-0.6). She was admitted for further management.

Infection remains on the differential diagnosis given the elevated WBC count. Since the patient has completed a reasonable course of antibiotics, a bacterial infection would be less likely but not fully excluded. The cultures obtained would be helpful if they become positive, but given that the patient has been on antibiotics, a negative culture may represent partial sterilization and would not rule out infection. A viral infection continues to be high on the differential, but one would expect that symptoms and fever would have begun to abate. The normal peripheral blood smear makes a hematologic disorder less likely.

Kawasaki disease has risen on the differential with 5 days of fever surpassing 102º F. She has 3 of 5 primary clinical criteria, including conjunctival injection, rash, and edema of the hands and feet. Desquamation of the peripheral extremities would not be expected until the convalescent phase. A diagnosis of typical Kawasaki disease would require a fourth criterion, either oral mucous membrane changes or cervical lymphadenopathy. She meets the criteria for atypical or incomplete Kawasaki disease, which requires only fever for at least 5 days, elevated CRP, and 2 or 3 additional clinical criteria. She also meets supplemental laboratory criteria with an elevated WBC count greater than 15,000/μL, normocytic and normochromic anemia for age, and elevated CRP. Urinalysis positive for pyuria or serum albumin less than 3 g/dL would lend further support but is not necessary. Fever of 7 or more days in a child less than 6 months old without other explanation would also increase the likelihood of incomplete Kawasaki disease. Admission to the hospital, treatment with IV immunoglobulin (IVIg), and echocardiography to evaluate for typical cardiac involvement (eg, aneurysms, coronary arteritis, and pericardial effusion) are the appropriate next steps.

The patient was diagnosed with atypical Kawasaki disease. A transthoracic echocardiogram was normal on admission. On day 7 of her illness, she was treated with 1 dose of IVIg at 2 g/kg and high-dose aspirin at 100 mg/kg per day in divided doses. Despite this treatment, she continued to be febrile and was given a second dose of IVIg on day 9. Her fevers persisted.

In Kawasaki disease, persistent fever is concerning for long-term sequelae, including coronary artery aneurysms. Continued treatment is reasonable. After 2 doses of IVIg with a cumulative dose of 4 g/kg, it is prudent to switch therapy to IV methylprednisolone 30mg/kg with repeated doses as needed for up to 3 days should her fevers persist.

Her blood culture was negative. EBV serology, enterovirus polymerase chain reaction, and viral cultures were negative. Chest radiography on day 9 was normal. Abdominal ultrasonography on day 10 showed hydrops of the gallbladder.

The patient was started on IV corticosteroids on day 11 with resolution of her fevers and improvement in her rash. A repeat echocardiogram revealed new findings of dilated left main, left anterior descending, and right coronary arteries. On day 13, a steroid wean was attempted because she had remained afebrile for more than 48 hours, but the wean was halted due to recurrence of fevers and rash. Her high-dose aspirin was reduced to 81 mg PO daily on day 14, and she was started on enoxaparin injections.

It is unusual for Kawasaki disease not to respond to 2 doses of IVIg, followed by corticosteroids. As such, the differential diagnosis must be revisited. The findings of coronary artery dilation, prolonged fever, and rash corroborate the diagnosis of Kawasaki disease, although this could be an atypical presentation of another vasculitis. Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis usually affects children at 2 to 5 years old and is, therefore, less likely. Henoch-Schönlein purpura manifests with a rash but is often associated with diarrhea. There does not appear to be objective evidence of polyarteritis nodosa, although biopsy or angiography would be required to make this diagnosis. Hydrops of the gallbladder is an over-distention of the organ filled with watery or mucoid content. While hydrops can be noninflammatory and seen in gallstone disease, it can also occur in vasculitides. Despite the reassuring serologies, false negative results are possible. Thus, these viral infections are not eliminated, but they are less likely. Given the echocardiogram findings and continued concern for atypical Kawasaki disease, high-dose aspirin should be continued. It is reasonable to consider rheumatology consultation for assessment and recommendations as to length of steroid treatment and/or alternative interventions.

Pediatric cardiology was consulted. Repeat echocardiogram on day 16 showed an increase in the size of her coronary artery aneurysms, and her fevers persisted. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast, obtained to further evaluate for a source of infection, was unremarkable.

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care institution on day 19, at which time she remained on aspirin, enoxaparin, and oral corticosteroids. On arrival, her temperature was 101.3º F, heart rate 225 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 57 breaths per minute. She was fussy with bilateral conjunctivitis and a maculopapular rash involving palms, soles, and right infraorbital region. Laboratory studies were significant for a WBC count of 30.3 k/μL; hemoglobin, 10.9 g/dL; platelets, 106 k/μL; and CRP, 8.3 mg/dL.

Pediatric rheumatology was consulted on day 20. The patient was treated with 3 days IV pulse-dose methylprednisolone at 30 mg/kg daily. Her fevers resolved, although her CRP level remained elevated. She was treated with 1 dose of infliximab 10 mg/kg IV on day 24, followed by 1 dose of anakinra 15 mg subcutaneously on day 27 due to persistently elevated CRP.

The symptoms and diagnostic evaluation remain most consistent with atypical Kawasaki disease. Her tachycardia and tachypnea are likely driven by her fever and fussiness, and should be followed closely. The elevated WBC is likely a consequence of the steroids and demargination of neutrophils. The elevated and increasing CRP is a marker of acute inflammation. The adage “treat the patient, not the numbers” comes to mind, because it is reassuring that the patient’s overall clinical picture seems to be improving with resolution of her fevers. However, further discussion with the pediatric rheumatology consultant is prudent, specifically regarding the significance of the persistently elevated CRP, refinement of the differential diagnosis including the potential for other vasculitides and appropriate evaluation of such, as well as recommendations for further treatment.

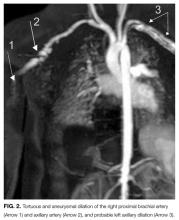

The patient was noted to have ongoing fevers. Based on reports of success with cyclophosphamide in refractory Kawasaki disease, she was treated with 2 doses at 60 mg IV per dose starting on day 28. Her CRP level decreased. Cardiology and rheumatology consultants recommended magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with and without contrast. These studies revealed dilation of the axillary and brachial arteries (Figure 2).

The response to cyclophosphamide confirms an autoimmune/inflammatory process. The imaging results and pattern are most consistent with either Kawasaki disease or polyarteritis nodosa. Therefore, rheumatology’s input will be invaluable with regard to which diagnosis is most likely, additional diagnostic testing, and appropriate medical regimen and follow-up plans.

Systemic extracoronary vascular inflammation on imaging and the refractory nature of the patient’s disease process, despite appropriate treatment for Kawasaki disease, led to the diagnosis of childhood polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). The patient was discharged home and closely followed in rheumatology clinic. Her most recent outpatient visit 1 year after the initial onset of her illness showed no further fevers or rashes, normal inflammatory markers, and stabilization of her coronary aneurysms on daily maintenance azathioprine.

DISCUSSION

Fever with an accompanying rash is a common issue in children. The extensive differential diagnosis includes infectious diseases, rheumatologic disorders, and medication reactions (Table 1). A thorough history and physical examination are essential in guiding the physician toward the proper diagnosis and management. Important information includes patient age, season, associated symptoms, exposure to sick contacts, travel history, host immune status, and immunization history. Fever duration and pattern must be elicited, as should features of the rash, including temporal relationship to the fever, distribution, progression, and morphology.1

When unexplained fever persists for 5 days or more in the pediatric patient, the diagnosis of KD must be suspected. KD is an acute, febrile, primary systemic vasculitis affecting small- and medium-sized vessels, with a predilection for coronary arteries.2 KD affects younger children, with approximately 85% of cases occurring in children under 5 years old. KD has a higher incidence in Asian populations, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition.3 The etiology of KD is not well understood, but infection and immune dysregulation have been proposed as contributing factors. KD is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in developed countries.2

The diagnosis of KD is made clinically (Table 2). Atypical KD is considered in patients with at least 5 days of fever but only 2 or 3 clinical criteria. Supportive laboratory findings include elevated inflammatory markers, anemia, neutrophilia, abnormal plasma lipids, low albumin, sterile pyuria, CSF pleocytosis, and elevated serum transaminases. Two-dimensional echocardiography should be performed in all children with definite or suspected KD at the time of diagnosis, 1 to 2 weeks later, and 6 weeks following discharge for evaluation of the coronary arteries, left ventricular function, and valve function. The American Heart Association recommends follow-up echocardiography at 1 year in children without coronary vessel involvement.4

Treatment is aimed at minimizing inflammation and coronary artery involvement, and should be initiated promptly.5 Therapy includes a single infusion of high-dose IVIg and aspirin;6,7 the latter is initially provided at high anti-inflammatory doses, followed by lower antithrombotic doses once fever and laboratory markers have resolved.2 Aspirin can be discontinued if there is no evidence of coronary involvement at the 6-week follow-up echocardiogram.5 A second dose of IVIg is given within 48 hours for refractory cases, defined as persistent fever following the first dose of IVIg.4 Fifteen percent of children have refractory illness, and refractory KD is associated with a higher risk of coronary artery lesions.5 Additional agents that suppress immune activation and cytokine secretion contributing to KD pathogenesis have been studied. Corticosteroids inhibit phospholipase A, an enzyme required for production of inflammatory markers.8 Infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor, has been shown to reduce duration of fever and length of hospital stay.8,9 Anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, has been shown to decrease fever duration and prevent progression of vascular injury in cases of refractory KD.10 There is, however, a lack of sufficient evidence and consensus on best practice.8-10

If inflammation, evidenced by fever, elevated inflammatory markers (such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP), or vessel involvement on imaging, persists or worsens despite standard therapy, physicians should seek alternative diagnoses. This patient’s extracoronary vascular inflammation and favorable response only to cyclophosphamide led to the diagnosis of systemic PAN. Like KD, PAN is a multi-system vasculitis affecting small- and medium-sized vessels. Unlike KD, PAN is rarely seen in children.11 Historically, PAN was thought to represent an extreme fatal end of the KD spectrum. Today, PAN is accepted as a separate entity. Clinical features and histological findings often overlap with KD, creating a diagnostic dilemma for providers.12