User login

Buspirone: A forgotten friend

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

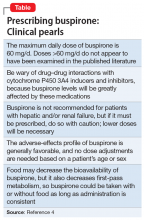

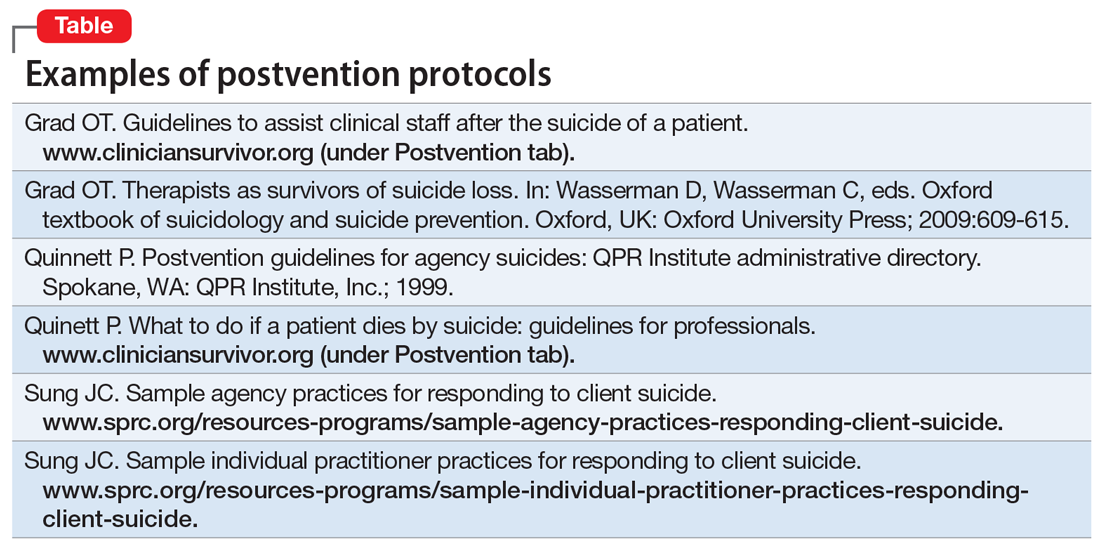

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

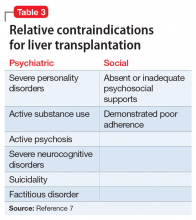

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.

Top research findings of 2018-2019 for clinical practice

Medical knowledge is growing faster than ever, as is the challenge of keeping up with this ever-growing body of information. Clinicians need a system or method to help them sort and evaluate the quality of new information before they can apply it to clinical care. Without such a system, when facing an overload of information, most of us tend to take the first or the most easily accessed information, without considering the quality of such information. As a result, the use of poor-quality information affects the quality and outcome of care we provide, and costs billions of dollars annually in problems associated with underuse, overuse, and misuse of treatments.

In an effort to sort and evaluate recently published research that is ready for clinical use, the first author (SAS) used the following 3-step methodology:

1. Searched literature for research findings suggesting readiness for clinical utilization published between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019.

2. Surveyed members of the American Association of Chairs of Departments of Psychiatry, the American Association of Community Psychiatrists, the American Association of Psychiatric Administrators, the North Carolina Psychiatric Association, the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, and many other colleagues by asking them: “Among the articles published from July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019, which ones in your opinion have (or are likely to have or should have) affected/changed the clinical practice of psychiatry?”

3. Looked for appraisals in post-publication reviews such as NEJM Journal Watch, F1000 Prime, Evidence-Based Mental Health, commentaries in peer-reviewed journals, and other sources (see Related Resources).

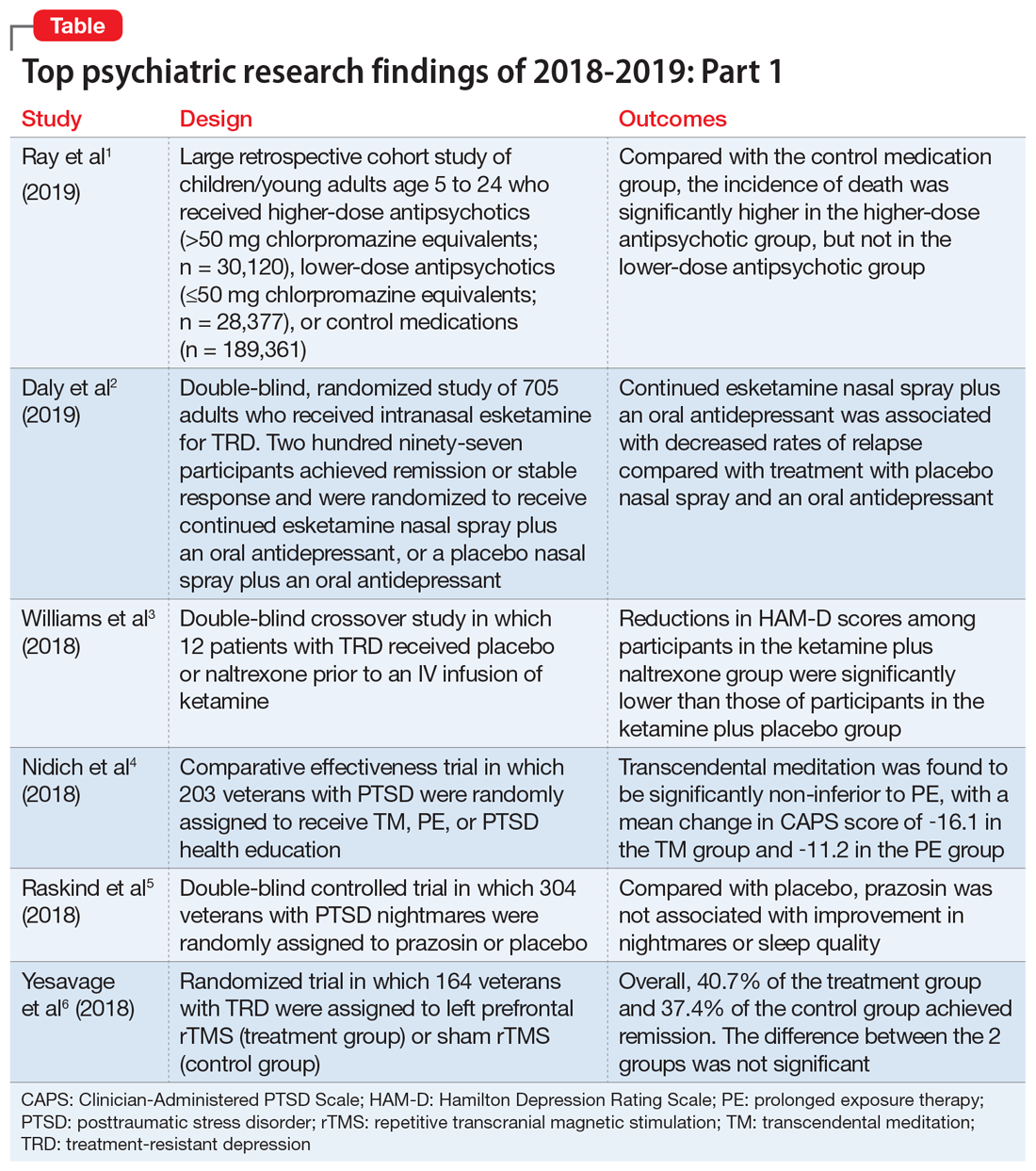

We chose 12 articles based on their clinical relevance/applicability. Here in Part 1 we present brief descriptions of the 6 of top 12 papers chosen by this methodology; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-6 The order in which they appear in this article is arbitrary. The remaining 6 studies will be reviewed in Part 2 in the February 2020 issue of

1. Ray WA, Stein CM, Murray KT, et al. Association of antipsychotic treatment with risk of unexpected death among children and youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):162-171.

Children and young adults are increasingly being prescribed antipsychotic medications. Studies have suggested that when these medications are used in adults and older patients, they are associated with an increased risk of death.7-9 Whether or not these medications are associated with an increased risk of death in children and youth has been unknown. Ray et al1 compared the risk of unexpected death among children and youths who were beginning treatment with an antipsychotic or control medications.

Study design

- This retrospective cohort study evaluated children and young adults age 5 to 24 who were enrolled in Medicaid in Tennessee between 1999 and 2014.

- New antipsychotic use at both a higher dose (>50 mg chlorpromazine equivalents) and a lower dose (≤50 mg chlorpromazine equivalents) was compared with new use of a control medication, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers.

- There were 189,361 participants in the control group, 28,377 participants in the lower-dose antipsychotic group, and 30,120 participants in the higher-dose antipsychotic group.

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was death due to injury or suicide or unexpected death occurring during study follow-up.

- The incidence of death in the higher-dose antipsychotic group (146.2 per 100,000 person-years) was significantly higher (P < .001) than the incidence of death in the control medications group (54.5 per 100,000 person years).

- There was no similar significant difference between the lower-dose antipsychotic group and the control medications group.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Higher-dose antipsychotic use is associated with increased rates of unexpected deaths in children and young adults.

- As with all association studies, no direct line connected cause and effect. However, these results reinforce recommendations for careful prescribing and monitoring of antipsychotic regimens for children and youths, and the need for larger antipsychotic safety studies in this population.

- Examining risks associated with specific antipsychotics will require larger datasets, but will be critical for our understanding of the risks and benefits.

2. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Janik A, et al. Efficacy of esketamine nasal spray plus oral antidepressant treatment for relapse prevention in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):893-903.

Controlled studies have shown esketamine has efficacy for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), but these studies have been only short-term, and the long-term effects of esketamine for TRD have not been established. To fill that gap, Daly et al2 assessed the efficacy of esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant vs a placebo nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant in delaying relapse of depressive symptoms in patients with TRD. All patients were in stable remission after an optimization course of esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

Study design

- Between October 2015 and February 2018, researchers conducted a phase III, multicenter, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study to evaluate the effect of continuation of esketamine on rates of relapse in patients with TRD who had responded to initial treatment with esketamine.

- Initially, 705 adults were enrolled. Of these participants, 455 proceeded to the optimization phase, in which they were treated with esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

- After 16 weeks of optimization treatment, 297 participants achieved remission or stable response and were randomized to a treatment group, which received continued esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant, or to a control group, which received a placebo nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

Outcomes

- Treatment with esketamine nasal spray and an oral antidepressant was associated with decreased rates of relapse compared with treatment with placebo nasal spray and an oral antidepressant. This was the case among patients who had achieved remission as well as those who had achieved stable response.

- Continued treatment with esketamine decreased the risk of relapse by 51%, with 40 participants in the treatment group experiencing relapse compared with 73 participants in the placebo group.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- In patients with TRD who responded to initial treatment with esketamine, continuing esketamine plus an oral antidepressant resulted in clinically meaningful superiority in preventing relapse compared with a placebo nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

3. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

Many studies have documented the efficacy of ketamine as a rapid-onset antidepressant. Studies investigating the mechanism of this effect have focused on antagonism of N-methyl-

Study design

- This double-blind crossover study evaluated if opioid receptor activation is necessary for ketamine to have an antidepressant effect in patients with TRD.

- Twelve participants completed both sides of the study in a randomized order. Participants received placebo or naltrexone prior to an IV infusion of ketamine.

- Researchers measured patients’ scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) at baseline and 1 day after infusion. Response was defined as a ≥50% reduction in HAM-D score.

Outcomes

- Reductions in HAM-D scores among participants in the ketamine plus naltrexone group were significantly lower than those of participants in the ketamine plus placebo group.

- Dissociation related to ketamine use did not differ significantly between the naltrexone group and the placebo group.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- This small study found a significant decrease in the antidepressant effect of ketamine infusion in patients with TRD when opioid receptors are blocked with naltrexone prior to infusion, which suggests opioid receptor activation is necessary for ketamine to be effective as an antidepressant.

- This appears to be consistent with observations of buprenorphine’s antidepressant effects. Caution is indicated until additional studies can further elucidate the mechanism of action of ketamine’s antidepressant effects (see "Ketamine/esketamine: Putative mechanism of action," page 32).

4. Nidich S, Mills PJ, Rainforth M, et al. Non-trauma-focused meditation versus exposure therapy in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):975-986.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common and important public health problem. Evidence-based treatments for PTSD include trauma-focused therapies such as prolonged exposure therapy (PE). However, some patients may not respond to PE, drop out, or elect not to pursue it. Researchers continue to explore treatments that are non-trauma-focused, such as mindfulness meditation and interpersonal psychotherapy. In a 3-group comparative effectiveness trial, Nidich et al4 examined the efficacy of a non-trauma-focused intervention, transcendental meditation (TM), in reducing PTSD symptom severity and depression in veterans.

Study design

- Researchers recruited 203 veterans with PTSD from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Healthcare System between June 2013 and October 2016.

- Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: 68 to TM, 68 to PE, and 67 to PTSD health education (HE).

- Each group received 12 sessions over 12 weeks. In addition to group and individual sessions, all participants received daily practice or assignments.

- The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) was used to assess symptoms before and after treatment.

Outcomes

- The primary outcome assessed was change in PTSD symptom severity at the end of the study compared with baseline as measured by change in CAPS score.

- Transcendental meditation was found to be significantly non-inferior to PE, with a mean change in CAPS score of −16.1 in the TM group and −11.2 in the PE group.

- Both the TM and PE groups also had significant reductions in CAPS scores compared with the HE group, which had a mean change in CAPS score of −2.5.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Transcendental meditation is significantly not inferior to PE in the treatment of veterans with PTSD.

- The findings from this first comparative effectiveness trial comparing TM with an established psychotherapy for PTSD suggests the feasibility and efficacy of TM as an alternative therapy for veterans with PTSD.

- Because TM is self-administered after an initial expert training, it may offer an easy-to-implement approach that may be more accessible to veterans than other treatments.

5. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517.

Several smaller randomized trials of prazosin involving a total of 283 active-duty service members, veterans, and civilian participants have shown efficacy of prazosin for PTSD-related nightmares, sleep disturbance, and overall clinical functioning. However, in a recent trial, Raskind et al5 failed to demonstrate such efficacy.

Study design

- Veterans with chronic PTSD nightmares were recruited from 13 VA medical centers to participate in a 26-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial.

- A total of 304 participants were randomized to a prazosin treatment group (n = 152) or a placebo control group (n = 152).

- During the first 10 weeks, prazosin or placebo were administered in an escalating fashion up to a maximum dose.

- The CAPS, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Clinical Global Impressions of Change (CGIC) scores were measured at baseline, after 10 weeks, and after 26 weeks.

Outcomes

- Three primary outcomes measures were assessed: change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on CAPS item B2, the PSQI, and the CGIC.

- A secondary measure was change in score from baseline of the same measures at 26 weeks.

- There was no significant difference between the prazosin group and the placebo group in any of the primary or secondary measures.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with placebo, prazosin was not associated with improvement in nightmares or sleep quality for veterans with chronic PTSD nightmares.

- Because psychosocial instability was an exclusion criterion, it is possible that a selection bias resulting from recruitment of patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition accounted for these negative results, since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment.

Treatment-resistant depression in veterans is a major clinical challenge because of these patients’ increased risk of suicide. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has shown promising results for TRD. In a randomized trial, Yesavage et al6 compared rTMS vs sham rTMS in veterans with TRD.

Study design

- Veterans with TRD were recruited from 9 VA medical centers throughout the United States between September 2012 and May 2016.

- Researchers randomized 164 participants into 1 of 2 groups in a double-blind fashion. The treatment group (n = 81) received left prefrontal rTMS, and the control group (n = 83) received sham rTMS.

Outcomes

- In an intention-to-treat analysis, remission rate (defined as a HAM-D score of ≤10) was assessed as the primary outcome measure.

- Remission was seen in both groups, with 40.7% of the treatment group achieving remission and 37.4% of the control group achieving remission. However, the difference between the 2 groups was not significant (P = .67), with an odds ratio of 1.16.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- In this study, treatment with rTMS did not show a statistically significant difference in rates of remission from TRD in veterans compared with sham rTMS. This differs from previous rTMS trials in non-veteran patients.

- The findings of this study also differed from those of other rTMS research in terms of the high remission rates that were seen in both the active and sham groups.

Bottom Line

The risk of death might be increased in children and young adults who receive highdose antipsychotics. Continued treatment with intranasal esketamine may help prevent relapse in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) who initially respond to esketamine. The antidepressant effects of ketamine might be associated with opioid receptor activation. Transcendental meditation may be helpful for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while prazosin might not improve nightmares or sleep quality in patients with PTSD. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) might not be any more effective than sham rTMS for veterans with TRD.

Related Resources

- NEJM Journal Watch. www.jwatch.org.

- F1000 Prime. https://f1000.com/prime/home.

- BMJ Journals Evidence-Based Mental Health. https://ebmh.bmj.com.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Subutex

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Esketamine nasal spray • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Naltrexone • Narcan

Prazosin • Minipress

1. Ray WA, Stein CM, Murray KT, et al. Association of antipsychotic treatment with risk of unexpected death among children and youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):162-171.

2. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Janik A, et al. Efficacy of esketamine nasal spray plus oral antidepressant treatment for relapse prevention in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):893-903.

3. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

4. Nidich S, Mills PJ, Rainforth M, et al. Non-trauma-focused meditation versus exposure therapy in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):975-986.

5. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517.

6. Yesavage JA, Fairchild JK, Mi Z, et al. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on treatment-resistant major depression in US veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):884-893.

7. Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(12):1161-1167.

8. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):225-235.

9. Jeste DV, Blazer D, Casey D, et al. ACNP White Paper: update on use of antipsychotic drugs in elderly persons with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(5):957-970.

Medical knowledge is growing faster than ever, as is the challenge of keeping up with this ever-growing body of information. Clinicians need a system or method to help them sort and evaluate the quality of new information before they can apply it to clinical care. Without such a system, when facing an overload of information, most of us tend to take the first or the most easily accessed information, without considering the quality of such information. As a result, the use of poor-quality information affects the quality and outcome of care we provide, and costs billions of dollars annually in problems associated with underuse, overuse, and misuse of treatments.

In an effort to sort and evaluate recently published research that is ready for clinical use, the first author (SAS) used the following 3-step methodology:

1. Searched literature for research findings suggesting readiness for clinical utilization published between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019.

2. Surveyed members of the American Association of Chairs of Departments of Psychiatry, the American Association of Community Psychiatrists, the American Association of Psychiatric Administrators, the North Carolina Psychiatric Association, the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, and many other colleagues by asking them: “Among the articles published from July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019, which ones in your opinion have (or are likely to have or should have) affected/changed the clinical practice of psychiatry?”

3. Looked for appraisals in post-publication reviews such as NEJM Journal Watch, F1000 Prime, Evidence-Based Mental Health, commentaries in peer-reviewed journals, and other sources (see Related Resources).

We chose 12 articles based on their clinical relevance/applicability. Here in Part 1 we present brief descriptions of the 6 of top 12 papers chosen by this methodology; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-6 The order in which they appear in this article is arbitrary. The remaining 6 studies will be reviewed in Part 2 in the February 2020 issue of

1. Ray WA, Stein CM, Murray KT, et al. Association of antipsychotic treatment with risk of unexpected death among children and youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):162-171.

Children and young adults are increasingly being prescribed antipsychotic medications. Studies have suggested that when these medications are used in adults and older patients, they are associated with an increased risk of death.7-9 Whether or not these medications are associated with an increased risk of death in children and youth has been unknown. Ray et al1 compared the risk of unexpected death among children and youths who were beginning treatment with an antipsychotic or control medications.

Study design

- This retrospective cohort study evaluated children and young adults age 5 to 24 who were enrolled in Medicaid in Tennessee between 1999 and 2014.

- New antipsychotic use at both a higher dose (>50 mg chlorpromazine equivalents) and a lower dose (≤50 mg chlorpromazine equivalents) was compared with new use of a control medication, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers.

- There were 189,361 participants in the control group, 28,377 participants in the lower-dose antipsychotic group, and 30,120 participants in the higher-dose antipsychotic group.

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was death due to injury or suicide or unexpected death occurring during study follow-up.

- The incidence of death in the higher-dose antipsychotic group (146.2 per 100,000 person-years) was significantly higher (P < .001) than the incidence of death in the control medications group (54.5 per 100,000 person years).

- There was no similar significant difference between the lower-dose antipsychotic group and the control medications group.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Higher-dose antipsychotic use is associated with increased rates of unexpected deaths in children and young adults.

- As with all association studies, no direct line connected cause and effect. However, these results reinforce recommendations for careful prescribing and monitoring of antipsychotic regimens for children and youths, and the need for larger antipsychotic safety studies in this population.

- Examining risks associated with specific antipsychotics will require larger datasets, but will be critical for our understanding of the risks and benefits.

2. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Janik A, et al. Efficacy of esketamine nasal spray plus oral antidepressant treatment for relapse prevention in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):893-903.

Controlled studies have shown esketamine has efficacy for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), but these studies have been only short-term, and the long-term effects of esketamine for TRD have not been established. To fill that gap, Daly et al2 assessed the efficacy of esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant vs a placebo nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant in delaying relapse of depressive symptoms in patients with TRD. All patients were in stable remission after an optimization course of esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

Study design

- Between October 2015 and February 2018, researchers conducted a phase III, multicenter, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study to evaluate the effect of continuation of esketamine on rates of relapse in patients with TRD who had responded to initial treatment with esketamine.

- Initially, 705 adults were enrolled. Of these participants, 455 proceeded to the optimization phase, in which they were treated with esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

- After 16 weeks of optimization treatment, 297 participants achieved remission or stable response and were randomized to a treatment group, which received continued esketamine nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant, or to a control group, which received a placebo nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

Outcomes

- Treatment with esketamine nasal spray and an oral antidepressant was associated with decreased rates of relapse compared with treatment with placebo nasal spray and an oral antidepressant. This was the case among patients who had achieved remission as well as those who had achieved stable response.

- Continued treatment with esketamine decreased the risk of relapse by 51%, with 40 participants in the treatment group experiencing relapse compared with 73 participants in the placebo group.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- In patients with TRD who responded to initial treatment with esketamine, continuing esketamine plus an oral antidepressant resulted in clinically meaningful superiority in preventing relapse compared with a placebo nasal spray plus an oral antidepressant.

3. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

Many studies have documented the efficacy of ketamine as a rapid-onset antidepressant. Studies investigating the mechanism of this effect have focused on antagonism of N-methyl-

Study design

- This double-blind crossover study evaluated if opioid receptor activation is necessary for ketamine to have an antidepressant effect in patients with TRD.

- Twelve participants completed both sides of the study in a randomized order. Participants received placebo or naltrexone prior to an IV infusion of ketamine.

- Researchers measured patients’ scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) at baseline and 1 day after infusion. Response was defined as a ≥50% reduction in HAM-D score.

Outcomes

- Reductions in HAM-D scores among participants in the ketamine plus naltrexone group were significantly lower than those of participants in the ketamine plus placebo group.

- Dissociation related to ketamine use did not differ significantly between the naltrexone group and the placebo group.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- This small study found a significant decrease in the antidepressant effect of ketamine infusion in patients with TRD when opioid receptors are blocked with naltrexone prior to infusion, which suggests opioid receptor activation is necessary for ketamine to be effective as an antidepressant.

- This appears to be consistent with observations of buprenorphine’s antidepressant effects. Caution is indicated until additional studies can further elucidate the mechanism of action of ketamine’s antidepressant effects (see "Ketamine/esketamine: Putative mechanism of action," page 32).

4. Nidich S, Mills PJ, Rainforth M, et al. Non-trauma-focused meditation versus exposure therapy in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):975-986.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common and important public health problem. Evidence-based treatments for PTSD include trauma-focused therapies such as prolonged exposure therapy (PE). However, some patients may not respond to PE, drop out, or elect not to pursue it. Researchers continue to explore treatments that are non-trauma-focused, such as mindfulness meditation and interpersonal psychotherapy. In a 3-group comparative effectiveness trial, Nidich et al4 examined the efficacy of a non-trauma-focused intervention, transcendental meditation (TM), in reducing PTSD symptom severity and depression in veterans.

Study design

- Researchers recruited 203 veterans with PTSD from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Healthcare System between June 2013 and October 2016.

- Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: 68 to TM, 68 to PE, and 67 to PTSD health education (HE).

- Each group received 12 sessions over 12 weeks. In addition to group and individual sessions, all participants received daily practice or assignments.

- The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) was used to assess symptoms before and after treatment.

Outcomes

- The primary outcome assessed was change in PTSD symptom severity at the end of the study compared with baseline as measured by change in CAPS score.

- Transcendental meditation was found to be significantly non-inferior to PE, with a mean change in CAPS score of −16.1 in the TM group and −11.2 in the PE group.

- Both the TM and PE groups also had significant reductions in CAPS scores compared with the HE group, which had a mean change in CAPS score of −2.5.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Transcendental meditation is significantly not inferior to PE in the treatment of veterans with PTSD.

- The findings from this first comparative effectiveness trial comparing TM with an established psychotherapy for PTSD suggests the feasibility and efficacy of TM as an alternative therapy for veterans with PTSD.

- Because TM is self-administered after an initial expert training, it may offer an easy-to-implement approach that may be more accessible to veterans than other treatments.

5. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517.

Several smaller randomized trials of prazosin involving a total of 283 active-duty service members, veterans, and civilian participants have shown efficacy of prazosin for PTSD-related nightmares, sleep disturbance, and overall clinical functioning. However, in a recent trial, Raskind et al5 failed to demonstrate such efficacy.

Study design

- Veterans with chronic PTSD nightmares were recruited from 13 VA medical centers to participate in a 26-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial.

- A total of 304 participants were randomized to a prazosin treatment group (n = 152) or a placebo control group (n = 152).

- During the first 10 weeks, prazosin or placebo were administered in an escalating fashion up to a maximum dose.

- The CAPS, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Clinical Global Impressions of Change (CGIC) scores were measured at baseline, after 10 weeks, and after 26 weeks.

Outcomes

- Three primary outcomes measures were assessed: change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on CAPS item B2, the PSQI, and the CGIC.

- A secondary measure was change in score from baseline of the same measures at 26 weeks.

- There was no significant difference between the prazosin group and the placebo group in any of the primary or secondary measures.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with placebo, prazosin was not associated with improvement in nightmares or sleep quality for veterans with chronic PTSD nightmares.

- Because psychosocial instability was an exclusion criterion, it is possible that a selection bias resulting from recruitment of patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition accounted for these negative results, since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment.

Treatment-resistant depression in veterans is a major clinical challenge because of these patients’ increased risk of suicide. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has shown promising results for TRD. In a randomized trial, Yesavage et al6 compared rTMS vs sham rTMS in veterans with TRD.

Study design

- Veterans with TRD were recruited from 9 VA medical centers throughout the United States between September 2012 and May 2016.

- Researchers randomized 164 participants into 1 of 2 groups in a double-blind fashion. The treatment group (n = 81) received left prefrontal rTMS, and the control group (n = 83) received sham rTMS.

Outcomes

- In an intention-to-treat analysis, remission rate (defined as a HAM-D score of ≤10) was assessed as the primary outcome measure.

- Remission was seen in both groups, with 40.7% of the treatment group achieving remission and 37.4% of the control group achieving remission. However, the difference between the 2 groups was not significant (P = .67), with an odds ratio of 1.16.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- In this study, treatment with rTMS did not show a statistically significant difference in rates of remission from TRD in veterans compared with sham rTMS. This differs from previous rTMS trials in non-veteran patients.

- The findings of this study also differed from those of other rTMS research in terms of the high remission rates that were seen in both the active and sham groups.

Bottom Line

The risk of death might be increased in children and young adults who receive highdose antipsychotics. Continued treatment with intranasal esketamine may help prevent relapse in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) who initially respond to esketamine. The antidepressant effects of ketamine might be associated with opioid receptor activation. Transcendental meditation may be helpful for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while prazosin might not improve nightmares or sleep quality in patients with PTSD. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) might not be any more effective than sham rTMS for veterans with TRD.

Related Resources

- NEJM Journal Watch. www.jwatch.org.

- F1000 Prime. https://f1000.com/prime/home.

- BMJ Journals Evidence-Based Mental Health. https://ebmh.bmj.com.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Subutex

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Esketamine nasal spray • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Naltrexone • Narcan

Prazosin • Minipress

Medical knowledge is growing faster than ever, as is the challenge of keeping up with this ever-growing body of information. Clinicians need a system or method to help them sort and evaluate the quality of new information before they can apply it to clinical care. Without such a system, when facing an overload of information, most of us tend to take the first or the most easily accessed information, without considering the quality of such information. As a result, the use of poor-quality information affects the quality and outcome of care we provide, and costs billions of dollars annually in problems associated with underuse, overuse, and misuse of treatments.

In an effort to sort and evaluate recently published research that is ready for clinical use, the first author (SAS) used the following 3-step methodology:

1. Searched literature for research findings suggesting readiness for clinical utilization published between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019.

2. Surveyed members of the American Association of Chairs of Departments of Psychiatry, the American Association of Community Psychiatrists, the American Association of Psychiatric Administrators, the North Carolina Psychiatric Association, the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, and many other colleagues by asking them: “Among the articles published from July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019, which ones in your opinion have (or are likely to have or should have) affected/changed the clinical practice of psychiatry?”

3. Looked for appraisals in post-publication reviews such as NEJM Journal Watch, F1000 Prime, Evidence-Based Mental Health, commentaries in peer-reviewed journals, and other sources (see Related Resources).

We chose 12 articles based on their clinical relevance/applicability. Here in Part 1 we present brief descriptions of the 6 of top 12 papers chosen by this methodology; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-6 The order in which they appear in this article is arbitrary. The remaining 6 studies will be reviewed in Part 2 in the February 2020 issue of

1. Ray WA, Stein CM, Murray KT, et al. Association of antipsychotic treatment with risk of unexpected death among children and youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):162-171.