User login

Confidentiality and privilege: What you don’t know can hurt you

Mrs. W, age 35, presents to your clinic seeking treatment for anxiety and depression. She has no psychiatric history but reports feeling sad, overwhelmed, and stressed. Mrs. W has been married for 10 years, has 2 young children, and is currently pregnant. She recently discovered that her husband has been having an affair. Mrs. W tells you that she feels her marriage is unsalvageable and would like to ask her husband for a divorce, but worries that he will “put up a fight” and demand full custody of their children. When you ask why, she states that her husband is “pretty narcissistic” and tends to become combative when criticized or threatened, such as a recent discussion they had about his affair that ended with him concluding that if she were “sexier and more confident” he would not have cheated on her.

As Mrs. W is talking, you recall a conversation you recently overheard at a continuing medical education event. Two clinicians were discussing how their records had been subpoenaed in a child custody case, even though the patient’s mental health was not contested. You realize that Mrs. W’s situation may also fit under this exception to confidentiality or privilege. You wonder if you should have disclosed this possibility to her at the outset of your session and wonder what you should say now, because she is clearly in distress and in need of psychiatric treatment. On the other hand, you want her to be fully informed of the potential repercussions if she continues with treatment.

Confidentiality and privilege allow our patients to disclose sensitive details in a safe space. The psychiatrist’s duty is to keep the patient’s information confidential, except in limited circumstances. The patient’s privilege is their right to prevent someone in a special confidential relationship from testifying against them or releasing their private records. In certain instances, a patient may waive or be forced to waive privilege, and a psychiatrist may be compelled to testify or release treatment records to a court. This article reviews exceptions to confidentiality and privilege, focusing specifically on a little-known exception to privilege that arises in divorce and child custody cases. We discuss relevant legislation and provide recommendations for psychiatrists to better understand how to discuss these legal realities with patients who are or may go through a divorce or child custody case.

Understanding confidentiality and privilege

Confidentiality and privilege are related but distinct concepts. Confidentiality relates to the overall trusting relationship created between 2 parties, such as a physician and their patient, and the duty on the part of the trusted individual to keep information private. Privilege refers to a person’s specific legal right to prevent someone in that confidential, trusting relationship from testifying against them in court or releasing confidential records. Privilege is owned by the patient and must be asserted or waived by the patient in legal proceedings. The concepts of confidentiality and privilege are crucial in creating an open, candid therapeutic environment. Many courts, including the US Supreme Court,1 have recognized the importance of confidentiality and privilege in establishing a positive therapeutic relationship between a psychotherapist and a patient. Without confidentiality and privilege, patients would be less likely to share sensitive yet clinically important information.

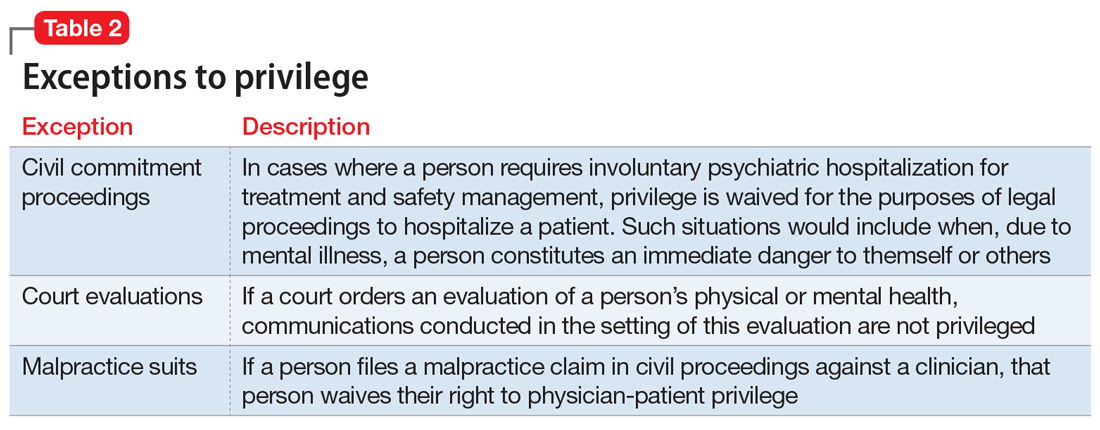

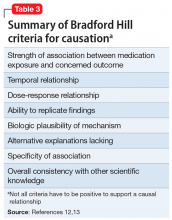

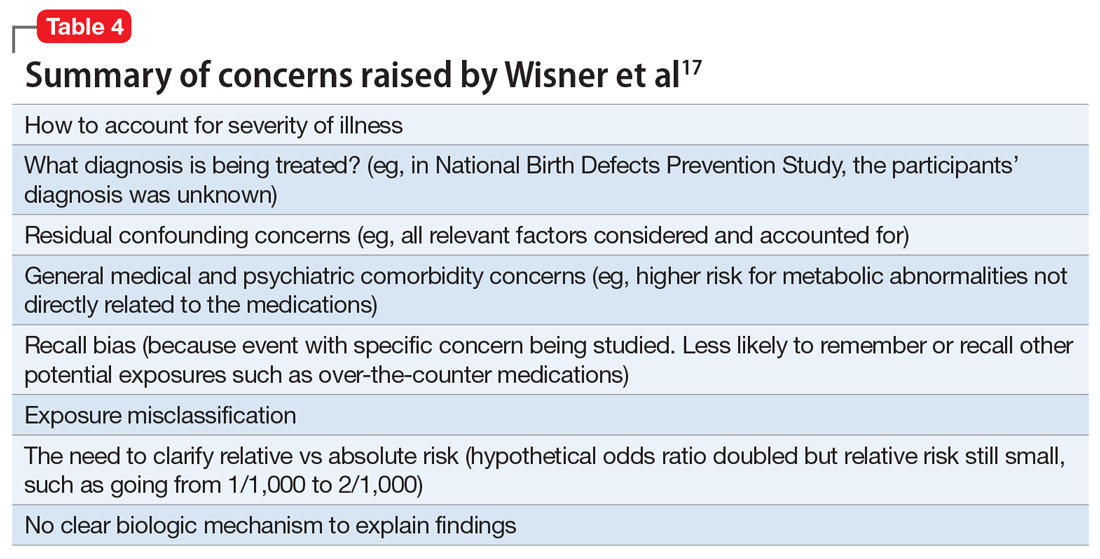

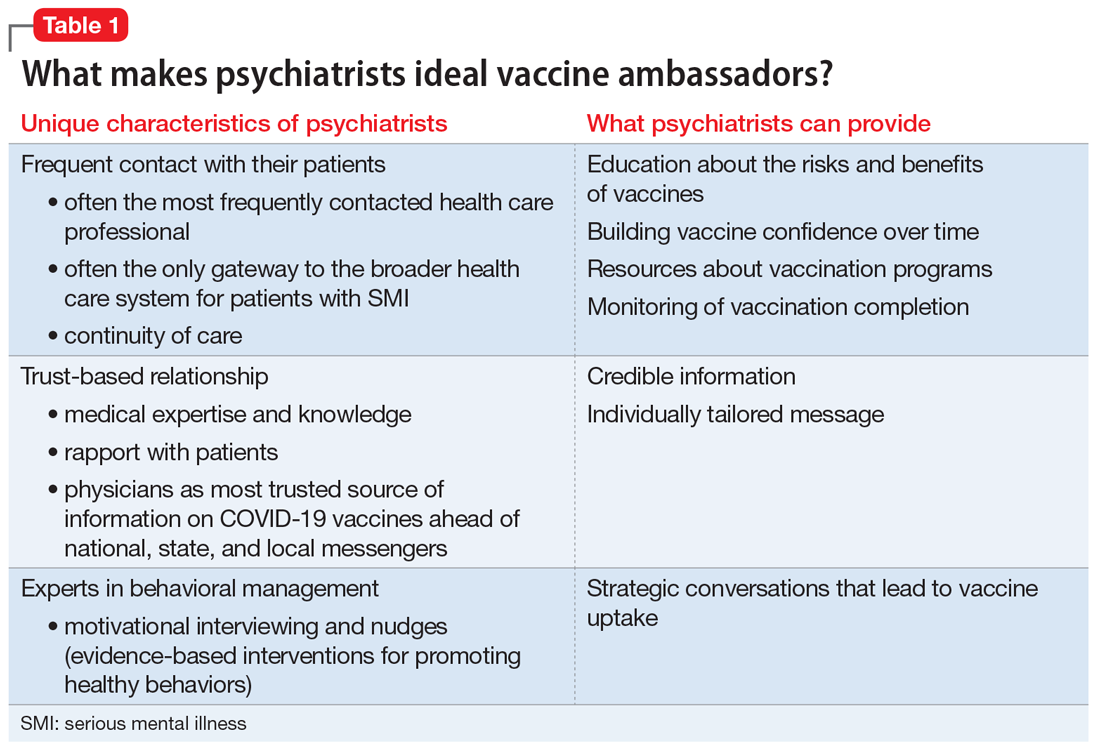

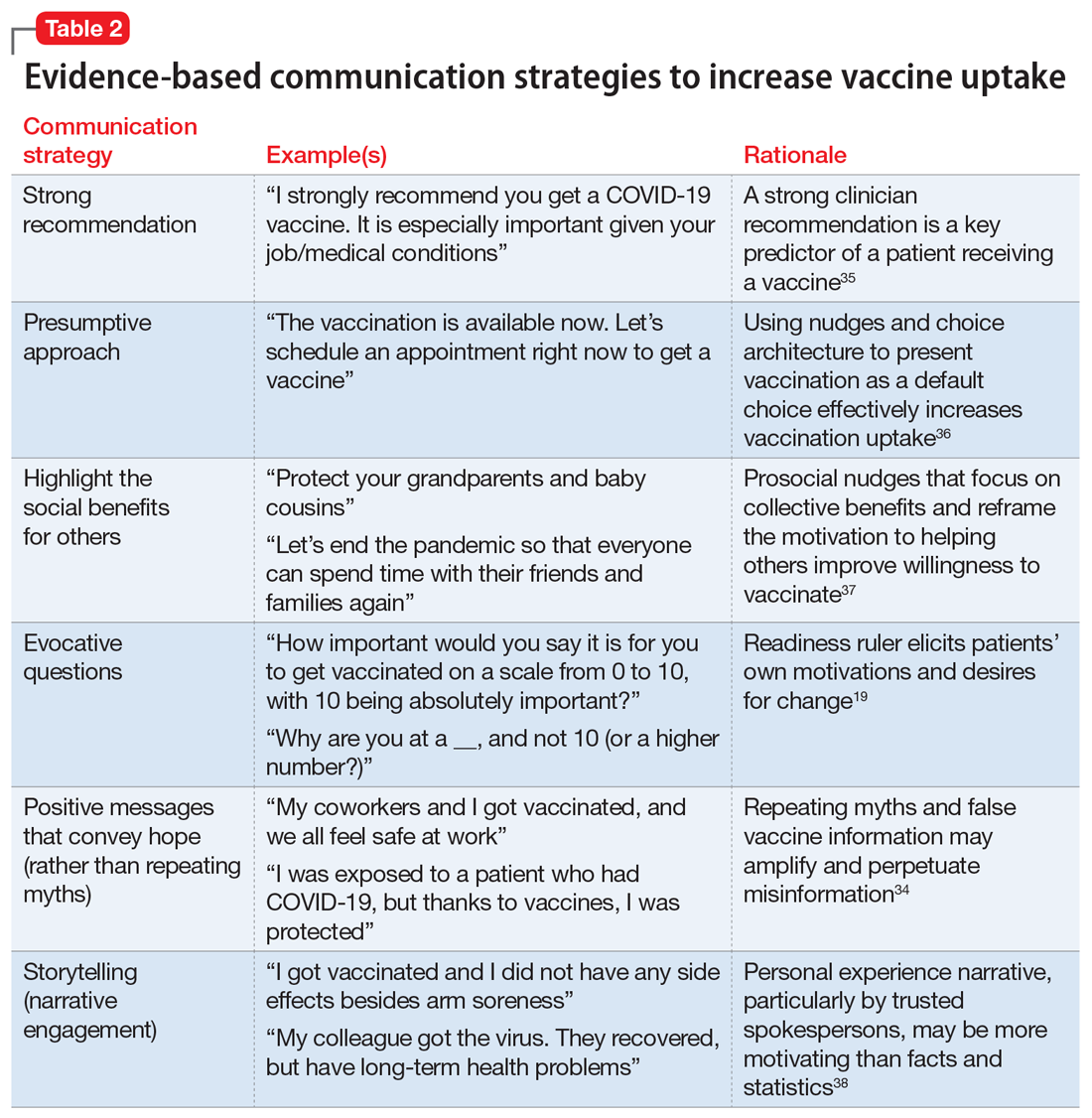

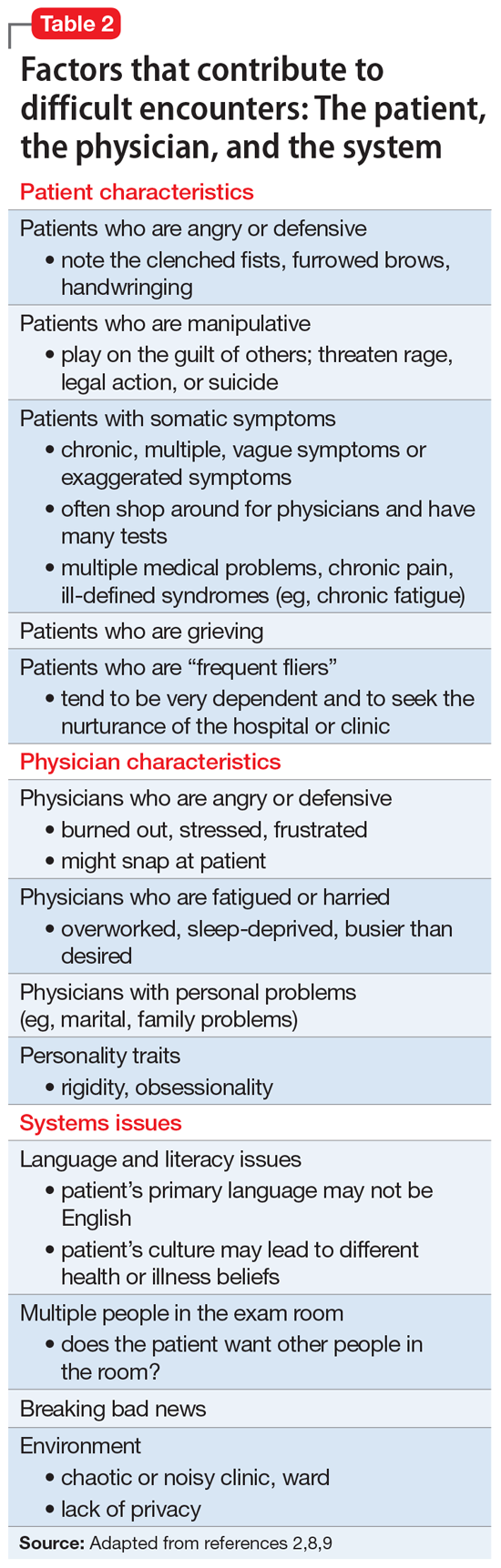

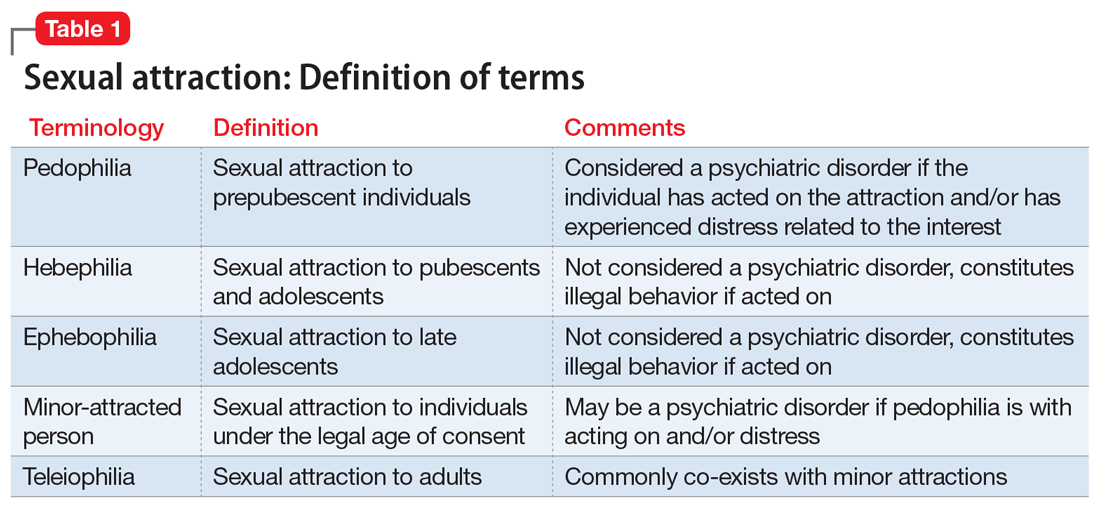

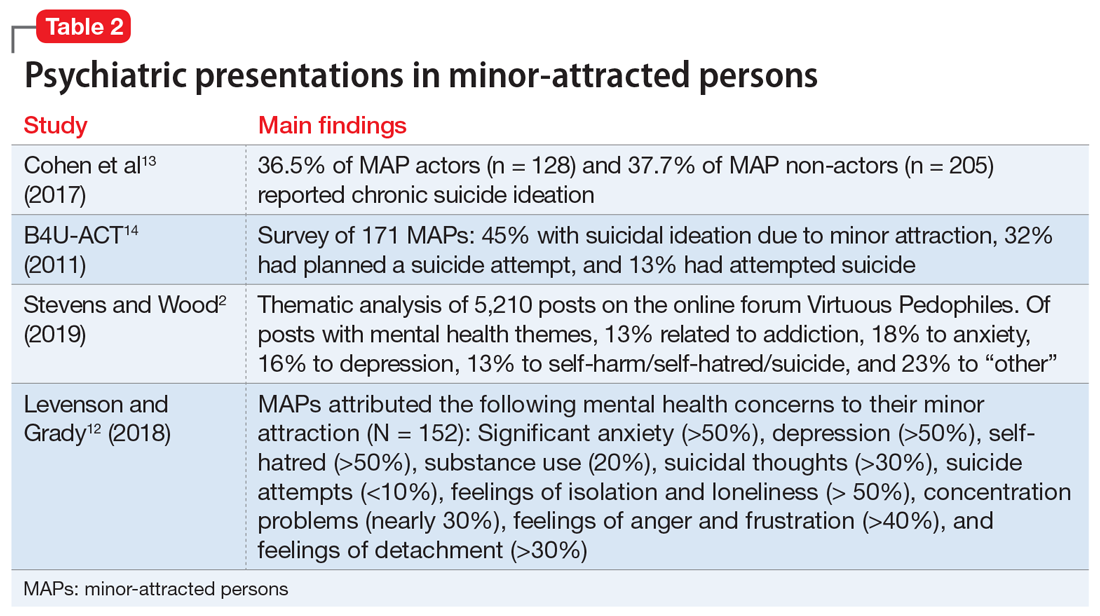

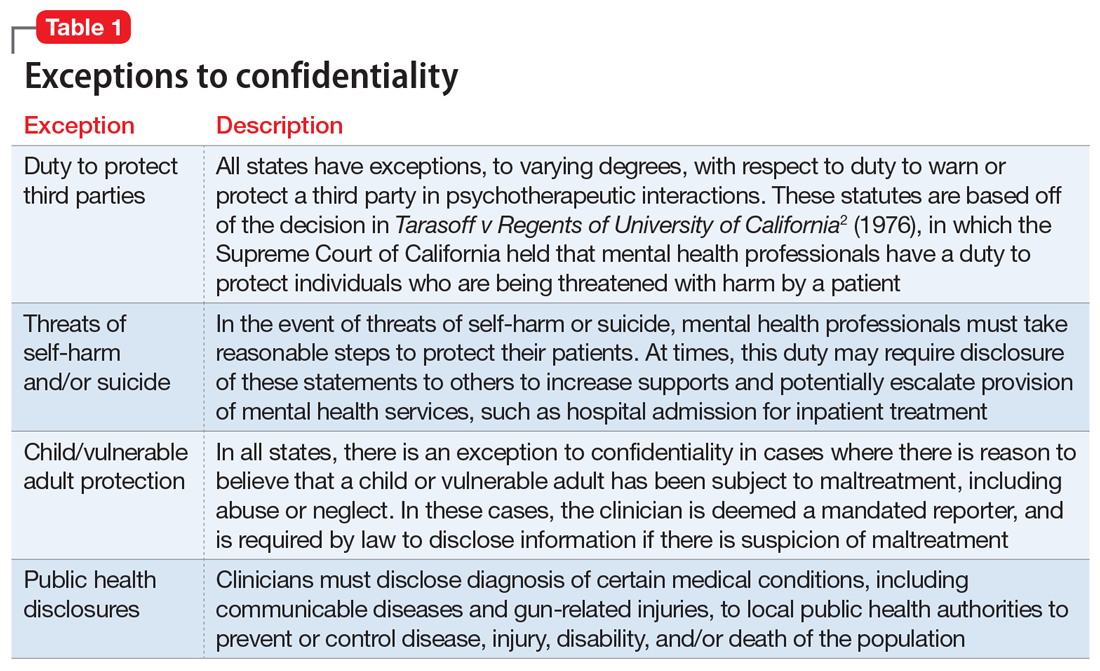

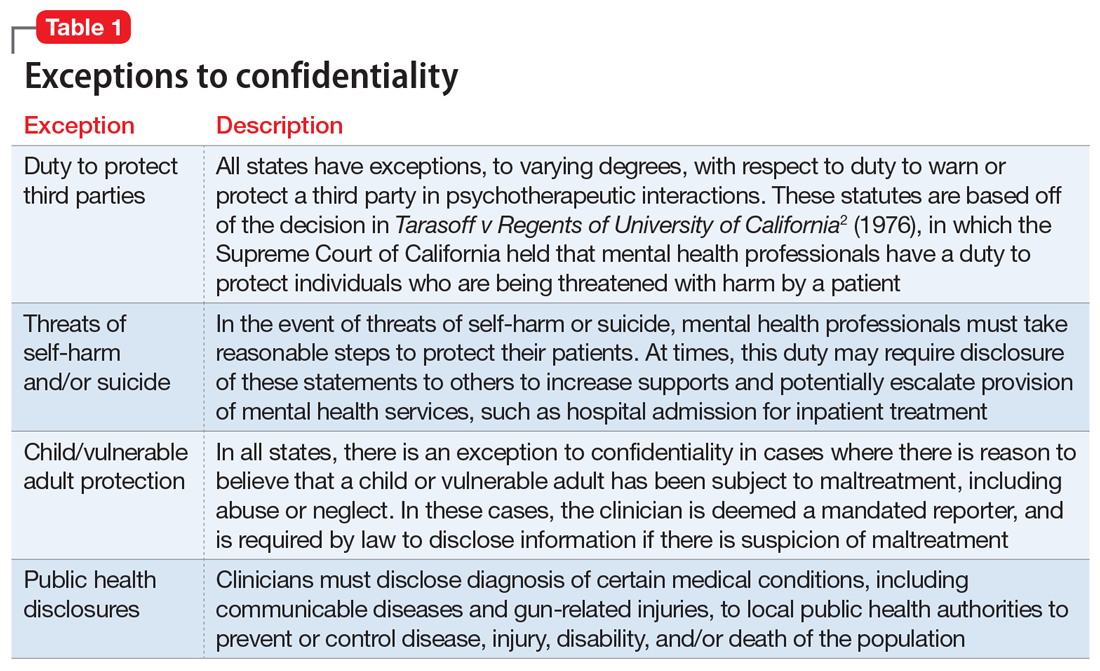

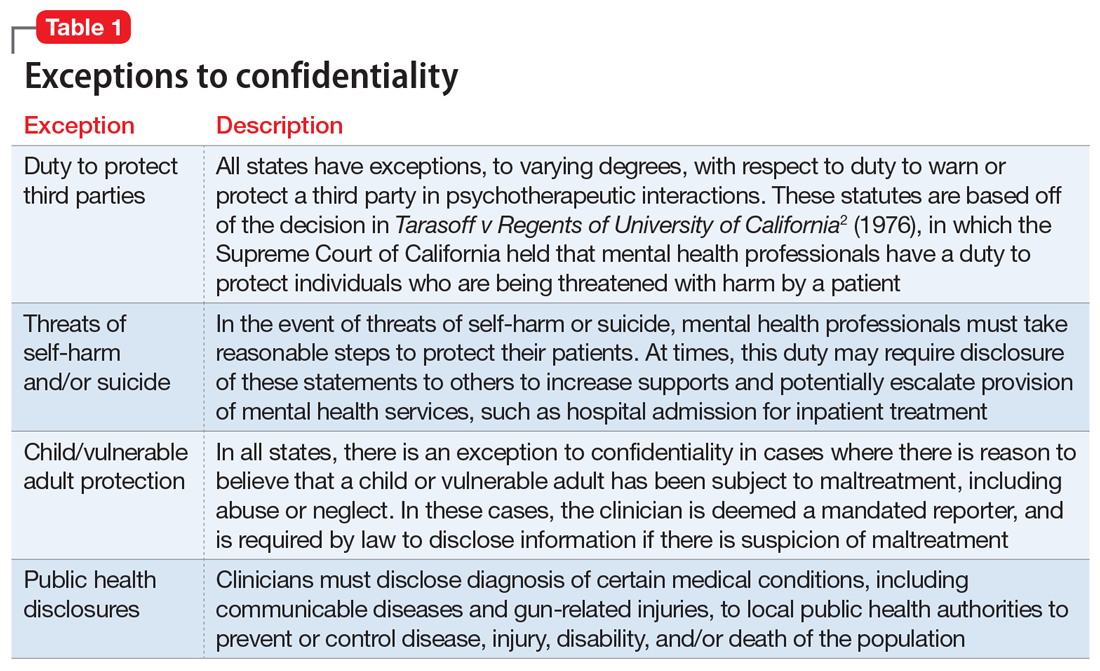

Commonly encountered exceptions to confidentiality (Table 12) and privilege (Table 2) exist in medical practice. Psychiatrists should discuss these exceptions with patients at the outset of clinical treatment. A little-known exception to privilege that may compel a psychiatrist to disclose confidential records can occur in child custody proceedings. In certain states, the mere filing of a child custody claim constitutes an exception to physician-patient privilege. In these states, the parent filing for divorce and custody may automatically waive privilege and thus compel disclosure of psychiatric records, even if their mental health is not in question. The following recent Ohio Supreme Court case illustrates this exception.

Friedenberg v Friedenberg (2020)

Friedenberg v Friedenberg3 addressed the issue of privilege and release of mental health treatment records in custody disputes. Belinda Torres Friedenberg and Keith Friedenberg were married with 4 minor children. Mrs. Friedenberg filed for divorce in 2016, requesting custody of the children and spousal support. In response, Mr. Friedenberg also filed a complaint seeking custody. Mr. Friedenberg subpoenaed mental health treatment records for Mrs. Friedenberg, who responded by filing a request to prevent the release of these records given physician-patient privilege. Mr. Friedenberg argued that Mrs. Friedenberg had placed her physical and mental health at issue when she filed for divorce and custody. At no point did Mr. Friedenberg allege that Mrs. Friedenberg’s mental health made her an unfit parent. The court agreed with Mr. Friedenberg and compelled disclosure of Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records, stating it is “hard to imagine a scenario where the mental health records of a parent would not be relevant to issues around custody and the best interests of the children.” The judge reviewed Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records privately and released records deemed relevant to the custody proceedings. On appeal, the Ohio Supreme Court agreed with this approach, holding that a parent’s mental fitness is always an issue in child custody cases, even if not asserted by either party. The court further held that unnecessary disclosure of sensitive information was prevented by the judge’s private review of records before deciding which records to release to the opposing spouse.

Waiver of physician-patient privilege

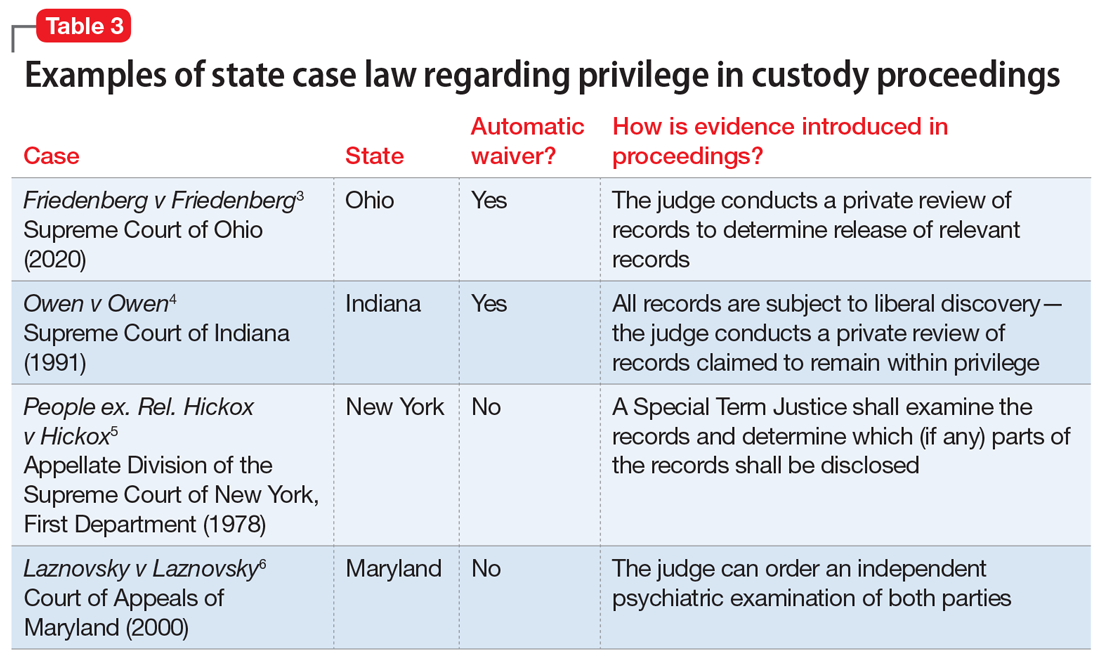

Waiver of physician-patient privilege in custody and divorce proceedings varies by state (Table 33-6). The Friedenberg decision highlights the most restrictive approach, where the mere filing of a divorce and child custody request automatically waives privilege. Some states, such as Indiana,4 follow a similar scheme to Ohio. Other states are silent on this issue or explicitly prohibit a waiver of privilege, asserting that custody disputes alone do not trigger disclosure without additional justifications, such as aberrant parental behaviors or other historical information concerning for abuse, neglect, or lack of parental fitness, or if a parent places their mental health at issue.7

Continue to: Once privilege is waived...

Once privilege is waived, the next step is to determine who should examine psychiatric records, deem relevance, and disclose sensitive information to the court and the opposing party. A judge may make this determination, as in the Friedenberg case. Alternatively, an independent psychiatric examiner may be appointed by the court to examine one or both parties; to obtain collateral information, including psychiatric records; and to submit a report to the court with medicolegal opinions regarding parental fitness. For example, in Maryland,6 the mere filing of a custody suit does not waive privilege. If a parent’s mental health is questioned, the judge may order an independent psychiatric examination to determine the parent’s fitness, thus balancing the best interests of the child with the parent’s right to physician-patient privilege.

The problem with automatic waivers

The foundation of the physician-patient relationship is trust and confidentiality. While this holds true for every specialty, perhaps it is even more important in psychiatry, where our patients routinely disclose sensitive, personal information in hopes of healing. Patients may not be aware of exceptions to confidentiality, or only be aware of the most well-known exceptions, such as the clinician’s duty to report abuse, or to warn a third party about risk of harm by a patient. Furthermore, clinicians and patients alike may not be aware of less-common exceptions to privilege, such as those that may occur in custody proceedings. This is critically important in light of the high number of patients who are or may be seeking divorce and custody of their children.

As psychiatric clinicians, it is highly likely that we will see patients going through divorce and custody proceedings. In 2018, there were 2.24 marriages for every divorce,8 and in 2014, 27% of all American children were living with a custodial parent, with the other parent living elsewhere.9 Divorce can be a profoundly stressful time; thus, it would be expected that many individuals going through divorce would seek psychiatric treatment and support.

Our concern is that the Friedenberg approach, which results in automatic disclosure of sensitive mental health information when a party files for divorce and custody, could deter patients from seeking psychiatric treatment, especially those anticipating divorce. Importantly, because women are nearly twice as likely as men to experience depression and anxiety10 and are more likely to seek treatment, this approach could disproportionately impact them.11 In general, an automatic waiver policy may create an additional obstacle for individuals who are already reticent to seek treatment.

How to handle these situations

As a psychiatrist, you should be familiar with your state’s laws regarding exceptions to patient-physician privilege, and should discuss exceptions at the outset of treatment. However, you will need to weigh the potential negative impacts of this information on the therapeutic relationship, including possible early termination. Furthermore, this information may impact a patient’s willingness to disclose all relevant information to mental health treatment if there is concern for later court disclosure. How should you balance these concerns? First, encourage patients to ask questions and raise concerns about confidentiality and privilege.12 In addition, you may direct the patient to other resources, such as a family law attorney, if they have questions about how certain information may be used in a legal proceeding.

Continue to: Second, you should be...

Second, you should be transparent regarding documentation of psychiatric visits. While documentation must meet ethical, legal, and billing requirements, you should take care to include only relevant information needed to make a diagnosis and provide indicated treatment while maintaining a neutral tone and avoiding medical jargon.13 For instance, we frequently use the term “denied” in medical documentation, as in “Mr. X denied cough, sore throat, fever or chills.” However, in psychiatric notes, if a patient “denied alcohol use,” the colloquial interpretation of this word could imply a tone of distrust toward the patient. A more sensitive way to document this might be: “When screened, reported no alcohol use.” If a patient divulges information and then asks you to omit this from their chart, but you do not feel comfortable doing so, explain what and why you must include the information in the chart.14

Third, if you receive a subpoena or other document requesting privileged information, first contact the patient and inform them of the request, and then seek legal consultation through your employer or malpractice insurer.15 Not all subpoenas are valid and enforceable, so it is important for an attorney to examine the subpoena; in addition, the patient’s attorney may choose to challenge the subpoena and limit the disclosure of privileged information.

Finally, inform legislatures and courts about the potential harm of automatic waivers in custody proceedings. A judge’s examination of the psychiatric records, as in Friedenberg, is not an adequate safeguard. A judge is not a trained mental health professional and may deem “relevant” information to be nearly everything: a history of abuse, remote drug or alcohol use, disclosure of a past crime, or financial troubles. We advocate for courts to follow the Maryland model, where a spouse does not automatically waive privilege if filing for divorce or custody. If mental health becomes an issue in a case, then the court may seek an independent psychiatric examination. The independent examiner will have access to patient records but will be in a better position to determine which details are relevant in determining diagnosis and parental fitness, and to render an opinion to the court.

CASE CONTINUED

You inform Mrs. W about a possible exception to privilege in divorce and custody cases. She decides to first talk with a family law attorney before proceeding with treatment. You defer your diagnosis and wait to see if she wants to proceed with treatment. Unfortunately, she does not return to your office.

Bottom Line

Some states limit the confidentiality and privilege of parents who are in psychiatric treatment and also involved in divorce and child custody cases. Psychiatrists should be mindful of these exceptions, and discuss them with patients at the onset of treatment.

Related Resources

- Legal Information Institute. Child custody: an overview. www.law.cornell.edu/wex/child_custody

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Child custody in divorce. In: Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. Guilford Press; 2018:530-533.

1. Jaffee v Redmond, 518 US 1 (1996).

2. Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 118 Cal Rptr 129 (Cal 1974); modified by Tarasoff v Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 551 P.2d 334 (Cal 1976).

3. Friedenberg v Friedenberg, No. 2019-0416 (Ohio 2020).

4. Owen v Owen, 563 NE 2d 605 (Ind 1991).

5. People ex. Rel. Hickox v Hickox, 410 NY S 2d 81 (NY App Div 1978).

6. Laznovsky v Laznovsky, 745 A 2d 1054 (Md 2000).

7. Eykel I, Miskel E. The mental health privilege in divorce and custody cases. Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers. 2012;25(2):453-476.

8. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats: Family life. Marriage and divorce. Published May 2020. Accessed July 29, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm

9. The United States Census Bureau. Current population reports: custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2013. Published January 2016. Accessed July 29, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/P60-255.pdf

10. World Health Organization. Gender and mental health. Published June 2002. Accessed August 2, 2021. https://www.who.int/gender/other_health/genderMH.pdf

11. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

12. Younggren J, Harris E. Can you keep a secret? Confidentiality in psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):589-600.

13. The Committee on Psychiatry and Law. Confidentiality and privilege communication in the practice of psychiatry. Report no. 45. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry; 1960.

14. Wiger D. Ethical considerations in documentation. In: Wiger D. The psychotherapy documentation primer. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2013:35-45.

15. Stansbury CD. Accessibility to a parent’s psychotherapy records in custody disputes: how can the competing interests be balanced? Behav Sci Law. 2010;28(4):522-541.

Mrs. W, age 35, presents to your clinic seeking treatment for anxiety and depression. She has no psychiatric history but reports feeling sad, overwhelmed, and stressed. Mrs. W has been married for 10 years, has 2 young children, and is currently pregnant. She recently discovered that her husband has been having an affair. Mrs. W tells you that she feels her marriage is unsalvageable and would like to ask her husband for a divorce, but worries that he will “put up a fight” and demand full custody of their children. When you ask why, she states that her husband is “pretty narcissistic” and tends to become combative when criticized or threatened, such as a recent discussion they had about his affair that ended with him concluding that if she were “sexier and more confident” he would not have cheated on her.

As Mrs. W is talking, you recall a conversation you recently overheard at a continuing medical education event. Two clinicians were discussing how their records had been subpoenaed in a child custody case, even though the patient’s mental health was not contested. You realize that Mrs. W’s situation may also fit under this exception to confidentiality or privilege. You wonder if you should have disclosed this possibility to her at the outset of your session and wonder what you should say now, because she is clearly in distress and in need of psychiatric treatment. On the other hand, you want her to be fully informed of the potential repercussions if she continues with treatment.

Confidentiality and privilege allow our patients to disclose sensitive details in a safe space. The psychiatrist’s duty is to keep the patient’s information confidential, except in limited circumstances. The patient’s privilege is their right to prevent someone in a special confidential relationship from testifying against them or releasing their private records. In certain instances, a patient may waive or be forced to waive privilege, and a psychiatrist may be compelled to testify or release treatment records to a court. This article reviews exceptions to confidentiality and privilege, focusing specifically on a little-known exception to privilege that arises in divorce and child custody cases. We discuss relevant legislation and provide recommendations for psychiatrists to better understand how to discuss these legal realities with patients who are or may go through a divorce or child custody case.

Understanding confidentiality and privilege

Confidentiality and privilege are related but distinct concepts. Confidentiality relates to the overall trusting relationship created between 2 parties, such as a physician and their patient, and the duty on the part of the trusted individual to keep information private. Privilege refers to a person’s specific legal right to prevent someone in that confidential, trusting relationship from testifying against them in court or releasing confidential records. Privilege is owned by the patient and must be asserted or waived by the patient in legal proceedings. The concepts of confidentiality and privilege are crucial in creating an open, candid therapeutic environment. Many courts, including the US Supreme Court,1 have recognized the importance of confidentiality and privilege in establishing a positive therapeutic relationship between a psychotherapist and a patient. Without confidentiality and privilege, patients would be less likely to share sensitive yet clinically important information.

Commonly encountered exceptions to confidentiality (Table 12) and privilege (Table 2) exist in medical practice. Psychiatrists should discuss these exceptions with patients at the outset of clinical treatment. A little-known exception to privilege that may compel a psychiatrist to disclose confidential records can occur in child custody proceedings. In certain states, the mere filing of a child custody claim constitutes an exception to physician-patient privilege. In these states, the parent filing for divorce and custody may automatically waive privilege and thus compel disclosure of psychiatric records, even if their mental health is not in question. The following recent Ohio Supreme Court case illustrates this exception.

Friedenberg v Friedenberg (2020)

Friedenberg v Friedenberg3 addressed the issue of privilege and release of mental health treatment records in custody disputes. Belinda Torres Friedenberg and Keith Friedenberg were married with 4 minor children. Mrs. Friedenberg filed for divorce in 2016, requesting custody of the children and spousal support. In response, Mr. Friedenberg also filed a complaint seeking custody. Mr. Friedenberg subpoenaed mental health treatment records for Mrs. Friedenberg, who responded by filing a request to prevent the release of these records given physician-patient privilege. Mr. Friedenberg argued that Mrs. Friedenberg had placed her physical and mental health at issue when she filed for divorce and custody. At no point did Mr. Friedenberg allege that Mrs. Friedenberg’s mental health made her an unfit parent. The court agreed with Mr. Friedenberg and compelled disclosure of Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records, stating it is “hard to imagine a scenario where the mental health records of a parent would not be relevant to issues around custody and the best interests of the children.” The judge reviewed Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records privately and released records deemed relevant to the custody proceedings. On appeal, the Ohio Supreme Court agreed with this approach, holding that a parent’s mental fitness is always an issue in child custody cases, even if not asserted by either party. The court further held that unnecessary disclosure of sensitive information was prevented by the judge’s private review of records before deciding which records to release to the opposing spouse.

Waiver of physician-patient privilege

Waiver of physician-patient privilege in custody and divorce proceedings varies by state (Table 33-6). The Friedenberg decision highlights the most restrictive approach, where the mere filing of a divorce and child custody request automatically waives privilege. Some states, such as Indiana,4 follow a similar scheme to Ohio. Other states are silent on this issue or explicitly prohibit a waiver of privilege, asserting that custody disputes alone do not trigger disclosure without additional justifications, such as aberrant parental behaviors or other historical information concerning for abuse, neglect, or lack of parental fitness, or if a parent places their mental health at issue.7

Continue to: Once privilege is waived...

Once privilege is waived, the next step is to determine who should examine psychiatric records, deem relevance, and disclose sensitive information to the court and the opposing party. A judge may make this determination, as in the Friedenberg case. Alternatively, an independent psychiatric examiner may be appointed by the court to examine one or both parties; to obtain collateral information, including psychiatric records; and to submit a report to the court with medicolegal opinions regarding parental fitness. For example, in Maryland,6 the mere filing of a custody suit does not waive privilege. If a parent’s mental health is questioned, the judge may order an independent psychiatric examination to determine the parent’s fitness, thus balancing the best interests of the child with the parent’s right to physician-patient privilege.

The problem with automatic waivers

The foundation of the physician-patient relationship is trust and confidentiality. While this holds true for every specialty, perhaps it is even more important in psychiatry, where our patients routinely disclose sensitive, personal information in hopes of healing. Patients may not be aware of exceptions to confidentiality, or only be aware of the most well-known exceptions, such as the clinician’s duty to report abuse, or to warn a third party about risk of harm by a patient. Furthermore, clinicians and patients alike may not be aware of less-common exceptions to privilege, such as those that may occur in custody proceedings. This is critically important in light of the high number of patients who are or may be seeking divorce and custody of their children.

As psychiatric clinicians, it is highly likely that we will see patients going through divorce and custody proceedings. In 2018, there were 2.24 marriages for every divorce,8 and in 2014, 27% of all American children were living with a custodial parent, with the other parent living elsewhere.9 Divorce can be a profoundly stressful time; thus, it would be expected that many individuals going through divorce would seek psychiatric treatment and support.

Our concern is that the Friedenberg approach, which results in automatic disclosure of sensitive mental health information when a party files for divorce and custody, could deter patients from seeking psychiatric treatment, especially those anticipating divorce. Importantly, because women are nearly twice as likely as men to experience depression and anxiety10 and are more likely to seek treatment, this approach could disproportionately impact them.11 In general, an automatic waiver policy may create an additional obstacle for individuals who are already reticent to seek treatment.

How to handle these situations

As a psychiatrist, you should be familiar with your state’s laws regarding exceptions to patient-physician privilege, and should discuss exceptions at the outset of treatment. However, you will need to weigh the potential negative impacts of this information on the therapeutic relationship, including possible early termination. Furthermore, this information may impact a patient’s willingness to disclose all relevant information to mental health treatment if there is concern for later court disclosure. How should you balance these concerns? First, encourage patients to ask questions and raise concerns about confidentiality and privilege.12 In addition, you may direct the patient to other resources, such as a family law attorney, if they have questions about how certain information may be used in a legal proceeding.

Continue to: Second, you should be...

Second, you should be transparent regarding documentation of psychiatric visits. While documentation must meet ethical, legal, and billing requirements, you should take care to include only relevant information needed to make a diagnosis and provide indicated treatment while maintaining a neutral tone and avoiding medical jargon.13 For instance, we frequently use the term “denied” in medical documentation, as in “Mr. X denied cough, sore throat, fever or chills.” However, in psychiatric notes, if a patient “denied alcohol use,” the colloquial interpretation of this word could imply a tone of distrust toward the patient. A more sensitive way to document this might be: “When screened, reported no alcohol use.” If a patient divulges information and then asks you to omit this from their chart, but you do not feel comfortable doing so, explain what and why you must include the information in the chart.14

Third, if you receive a subpoena or other document requesting privileged information, first contact the patient and inform them of the request, and then seek legal consultation through your employer or malpractice insurer.15 Not all subpoenas are valid and enforceable, so it is important for an attorney to examine the subpoena; in addition, the patient’s attorney may choose to challenge the subpoena and limit the disclosure of privileged information.

Finally, inform legislatures and courts about the potential harm of automatic waivers in custody proceedings. A judge’s examination of the psychiatric records, as in Friedenberg, is not an adequate safeguard. A judge is not a trained mental health professional and may deem “relevant” information to be nearly everything: a history of abuse, remote drug or alcohol use, disclosure of a past crime, or financial troubles. We advocate for courts to follow the Maryland model, where a spouse does not automatically waive privilege if filing for divorce or custody. If mental health becomes an issue in a case, then the court may seek an independent psychiatric examination. The independent examiner will have access to patient records but will be in a better position to determine which details are relevant in determining diagnosis and parental fitness, and to render an opinion to the court.

CASE CONTINUED

You inform Mrs. W about a possible exception to privilege in divorce and custody cases. She decides to first talk with a family law attorney before proceeding with treatment. You defer your diagnosis and wait to see if she wants to proceed with treatment. Unfortunately, she does not return to your office.

Bottom Line

Some states limit the confidentiality and privilege of parents who are in psychiatric treatment and also involved in divorce and child custody cases. Psychiatrists should be mindful of these exceptions, and discuss them with patients at the onset of treatment.

Related Resources

- Legal Information Institute. Child custody: an overview. www.law.cornell.edu/wex/child_custody

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Child custody in divorce. In: Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. Guilford Press; 2018:530-533.

Mrs. W, age 35, presents to your clinic seeking treatment for anxiety and depression. She has no psychiatric history but reports feeling sad, overwhelmed, and stressed. Mrs. W has been married for 10 years, has 2 young children, and is currently pregnant. She recently discovered that her husband has been having an affair. Mrs. W tells you that she feels her marriage is unsalvageable and would like to ask her husband for a divorce, but worries that he will “put up a fight” and demand full custody of their children. When you ask why, she states that her husband is “pretty narcissistic” and tends to become combative when criticized or threatened, such as a recent discussion they had about his affair that ended with him concluding that if she were “sexier and more confident” he would not have cheated on her.

As Mrs. W is talking, you recall a conversation you recently overheard at a continuing medical education event. Two clinicians were discussing how their records had been subpoenaed in a child custody case, even though the patient’s mental health was not contested. You realize that Mrs. W’s situation may also fit under this exception to confidentiality or privilege. You wonder if you should have disclosed this possibility to her at the outset of your session and wonder what you should say now, because she is clearly in distress and in need of psychiatric treatment. On the other hand, you want her to be fully informed of the potential repercussions if she continues with treatment.

Confidentiality and privilege allow our patients to disclose sensitive details in a safe space. The psychiatrist’s duty is to keep the patient’s information confidential, except in limited circumstances. The patient’s privilege is their right to prevent someone in a special confidential relationship from testifying against them or releasing their private records. In certain instances, a patient may waive or be forced to waive privilege, and a psychiatrist may be compelled to testify or release treatment records to a court. This article reviews exceptions to confidentiality and privilege, focusing specifically on a little-known exception to privilege that arises in divorce and child custody cases. We discuss relevant legislation and provide recommendations for psychiatrists to better understand how to discuss these legal realities with patients who are or may go through a divorce or child custody case.

Understanding confidentiality and privilege

Confidentiality and privilege are related but distinct concepts. Confidentiality relates to the overall trusting relationship created between 2 parties, such as a physician and their patient, and the duty on the part of the trusted individual to keep information private. Privilege refers to a person’s specific legal right to prevent someone in that confidential, trusting relationship from testifying against them in court or releasing confidential records. Privilege is owned by the patient and must be asserted or waived by the patient in legal proceedings. The concepts of confidentiality and privilege are crucial in creating an open, candid therapeutic environment. Many courts, including the US Supreme Court,1 have recognized the importance of confidentiality and privilege in establishing a positive therapeutic relationship between a psychotherapist and a patient. Without confidentiality and privilege, patients would be less likely to share sensitive yet clinically important information.

Commonly encountered exceptions to confidentiality (Table 12) and privilege (Table 2) exist in medical practice. Psychiatrists should discuss these exceptions with patients at the outset of clinical treatment. A little-known exception to privilege that may compel a psychiatrist to disclose confidential records can occur in child custody proceedings. In certain states, the mere filing of a child custody claim constitutes an exception to physician-patient privilege. In these states, the parent filing for divorce and custody may automatically waive privilege and thus compel disclosure of psychiatric records, even if their mental health is not in question. The following recent Ohio Supreme Court case illustrates this exception.

Friedenberg v Friedenberg (2020)

Friedenberg v Friedenberg3 addressed the issue of privilege and release of mental health treatment records in custody disputes. Belinda Torres Friedenberg and Keith Friedenberg were married with 4 minor children. Mrs. Friedenberg filed for divorce in 2016, requesting custody of the children and spousal support. In response, Mr. Friedenberg also filed a complaint seeking custody. Mr. Friedenberg subpoenaed mental health treatment records for Mrs. Friedenberg, who responded by filing a request to prevent the release of these records given physician-patient privilege. Mr. Friedenberg argued that Mrs. Friedenberg had placed her physical and mental health at issue when she filed for divorce and custody. At no point did Mr. Friedenberg allege that Mrs. Friedenberg’s mental health made her an unfit parent. The court agreed with Mr. Friedenberg and compelled disclosure of Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records, stating it is “hard to imagine a scenario where the mental health records of a parent would not be relevant to issues around custody and the best interests of the children.” The judge reviewed Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records privately and released records deemed relevant to the custody proceedings. On appeal, the Ohio Supreme Court agreed with this approach, holding that a parent’s mental fitness is always an issue in child custody cases, even if not asserted by either party. The court further held that unnecessary disclosure of sensitive information was prevented by the judge’s private review of records before deciding which records to release to the opposing spouse.

Waiver of physician-patient privilege

Waiver of physician-patient privilege in custody and divorce proceedings varies by state (Table 33-6). The Friedenberg decision highlights the most restrictive approach, where the mere filing of a divorce and child custody request automatically waives privilege. Some states, such as Indiana,4 follow a similar scheme to Ohio. Other states are silent on this issue or explicitly prohibit a waiver of privilege, asserting that custody disputes alone do not trigger disclosure without additional justifications, such as aberrant parental behaviors or other historical information concerning for abuse, neglect, or lack of parental fitness, or if a parent places their mental health at issue.7

Continue to: Once privilege is waived...

Once privilege is waived, the next step is to determine who should examine psychiatric records, deem relevance, and disclose sensitive information to the court and the opposing party. A judge may make this determination, as in the Friedenberg case. Alternatively, an independent psychiatric examiner may be appointed by the court to examine one or both parties; to obtain collateral information, including psychiatric records; and to submit a report to the court with medicolegal opinions regarding parental fitness. For example, in Maryland,6 the mere filing of a custody suit does not waive privilege. If a parent’s mental health is questioned, the judge may order an independent psychiatric examination to determine the parent’s fitness, thus balancing the best interests of the child with the parent’s right to physician-patient privilege.

The problem with automatic waivers

The foundation of the physician-patient relationship is trust and confidentiality. While this holds true for every specialty, perhaps it is even more important in psychiatry, where our patients routinely disclose sensitive, personal information in hopes of healing. Patients may not be aware of exceptions to confidentiality, or only be aware of the most well-known exceptions, such as the clinician’s duty to report abuse, or to warn a third party about risk of harm by a patient. Furthermore, clinicians and patients alike may not be aware of less-common exceptions to privilege, such as those that may occur in custody proceedings. This is critically important in light of the high number of patients who are or may be seeking divorce and custody of their children.

As psychiatric clinicians, it is highly likely that we will see patients going through divorce and custody proceedings. In 2018, there were 2.24 marriages for every divorce,8 and in 2014, 27% of all American children were living with a custodial parent, with the other parent living elsewhere.9 Divorce can be a profoundly stressful time; thus, it would be expected that many individuals going through divorce would seek psychiatric treatment and support.

Our concern is that the Friedenberg approach, which results in automatic disclosure of sensitive mental health information when a party files for divorce and custody, could deter patients from seeking psychiatric treatment, especially those anticipating divorce. Importantly, because women are nearly twice as likely as men to experience depression and anxiety10 and are more likely to seek treatment, this approach could disproportionately impact them.11 In general, an automatic waiver policy may create an additional obstacle for individuals who are already reticent to seek treatment.

How to handle these situations

As a psychiatrist, you should be familiar with your state’s laws regarding exceptions to patient-physician privilege, and should discuss exceptions at the outset of treatment. However, you will need to weigh the potential negative impacts of this information on the therapeutic relationship, including possible early termination. Furthermore, this information may impact a patient’s willingness to disclose all relevant information to mental health treatment if there is concern for later court disclosure. How should you balance these concerns? First, encourage patients to ask questions and raise concerns about confidentiality and privilege.12 In addition, you may direct the patient to other resources, such as a family law attorney, if they have questions about how certain information may be used in a legal proceeding.

Continue to: Second, you should be...

Second, you should be transparent regarding documentation of psychiatric visits. While documentation must meet ethical, legal, and billing requirements, you should take care to include only relevant information needed to make a diagnosis and provide indicated treatment while maintaining a neutral tone and avoiding medical jargon.13 For instance, we frequently use the term “denied” in medical documentation, as in “Mr. X denied cough, sore throat, fever or chills.” However, in psychiatric notes, if a patient “denied alcohol use,” the colloquial interpretation of this word could imply a tone of distrust toward the patient. A more sensitive way to document this might be: “When screened, reported no alcohol use.” If a patient divulges information and then asks you to omit this from their chart, but you do not feel comfortable doing so, explain what and why you must include the information in the chart.14

Third, if you receive a subpoena or other document requesting privileged information, first contact the patient and inform them of the request, and then seek legal consultation through your employer or malpractice insurer.15 Not all subpoenas are valid and enforceable, so it is important for an attorney to examine the subpoena; in addition, the patient’s attorney may choose to challenge the subpoena and limit the disclosure of privileged information.

Finally, inform legislatures and courts about the potential harm of automatic waivers in custody proceedings. A judge’s examination of the psychiatric records, as in Friedenberg, is not an adequate safeguard. A judge is not a trained mental health professional and may deem “relevant” information to be nearly everything: a history of abuse, remote drug or alcohol use, disclosure of a past crime, or financial troubles. We advocate for courts to follow the Maryland model, where a spouse does not automatically waive privilege if filing for divorce or custody. If mental health becomes an issue in a case, then the court may seek an independent psychiatric examination. The independent examiner will have access to patient records but will be in a better position to determine which details are relevant in determining diagnosis and parental fitness, and to render an opinion to the court.

CASE CONTINUED

You inform Mrs. W about a possible exception to privilege in divorce and custody cases. She decides to first talk with a family law attorney before proceeding with treatment. You defer your diagnosis and wait to see if she wants to proceed with treatment. Unfortunately, she does not return to your office.

Bottom Line

Some states limit the confidentiality and privilege of parents who are in psychiatric treatment and also involved in divorce and child custody cases. Psychiatrists should be mindful of these exceptions, and discuss them with patients at the onset of treatment.

Related Resources

- Legal Information Institute. Child custody: an overview. www.law.cornell.edu/wex/child_custody

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Child custody in divorce. In: Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. Guilford Press; 2018:530-533.

1. Jaffee v Redmond, 518 US 1 (1996).

2. Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 118 Cal Rptr 129 (Cal 1974); modified by Tarasoff v Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 551 P.2d 334 (Cal 1976).

3. Friedenberg v Friedenberg, No. 2019-0416 (Ohio 2020).

4. Owen v Owen, 563 NE 2d 605 (Ind 1991).

5. People ex. Rel. Hickox v Hickox, 410 NY S 2d 81 (NY App Div 1978).

6. Laznovsky v Laznovsky, 745 A 2d 1054 (Md 2000).

7. Eykel I, Miskel E. The mental health privilege in divorce and custody cases. Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers. 2012;25(2):453-476.

8. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats: Family life. Marriage and divorce. Published May 2020. Accessed July 29, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm

9. The United States Census Bureau. Current population reports: custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2013. Published January 2016. Accessed July 29, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/P60-255.pdf

10. World Health Organization. Gender and mental health. Published June 2002. Accessed August 2, 2021. https://www.who.int/gender/other_health/genderMH.pdf

11. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

12. Younggren J, Harris E. Can you keep a secret? Confidentiality in psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):589-600.

13. The Committee on Psychiatry and Law. Confidentiality and privilege communication in the practice of psychiatry. Report no. 45. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry; 1960.

14. Wiger D. Ethical considerations in documentation. In: Wiger D. The psychotherapy documentation primer. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2013:35-45.

15. Stansbury CD. Accessibility to a parent’s psychotherapy records in custody disputes: how can the competing interests be balanced? Behav Sci Law. 2010;28(4):522-541.

1. Jaffee v Redmond, 518 US 1 (1996).

2. Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 118 Cal Rptr 129 (Cal 1974); modified by Tarasoff v Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 551 P.2d 334 (Cal 1976).

3. Friedenberg v Friedenberg, No. 2019-0416 (Ohio 2020).

4. Owen v Owen, 563 NE 2d 605 (Ind 1991).

5. People ex. Rel. Hickox v Hickox, 410 NY S 2d 81 (NY App Div 1978).

6. Laznovsky v Laznovsky, 745 A 2d 1054 (Md 2000).

7. Eykel I, Miskel E. The mental health privilege in divorce and custody cases. Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers. 2012;25(2):453-476.

8. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats: Family life. Marriage and divorce. Published May 2020. Accessed July 29, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm

9. The United States Census Bureau. Current population reports: custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2013. Published January 2016. Accessed July 29, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/P60-255.pdf

10. World Health Organization. Gender and mental health. Published June 2002. Accessed August 2, 2021. https://www.who.int/gender/other_health/genderMH.pdf

11. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

12. Younggren J, Harris E. Can you keep a secret? Confidentiality in psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):589-600.

13. The Committee on Psychiatry and Law. Confidentiality and privilege communication in the practice of psychiatry. Report no. 45. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry; 1960.

14. Wiger D. Ethical considerations in documentation. In: Wiger D. The psychotherapy documentation primer. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2013:35-45.

15. Stansbury CD. Accessibility to a parent’s psychotherapy records in custody disputes: how can the competing interests be balanced? Behav Sci Law. 2010;28(4):522-541.

Psychological/neuropsychological testing: When to refer for reexamination

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

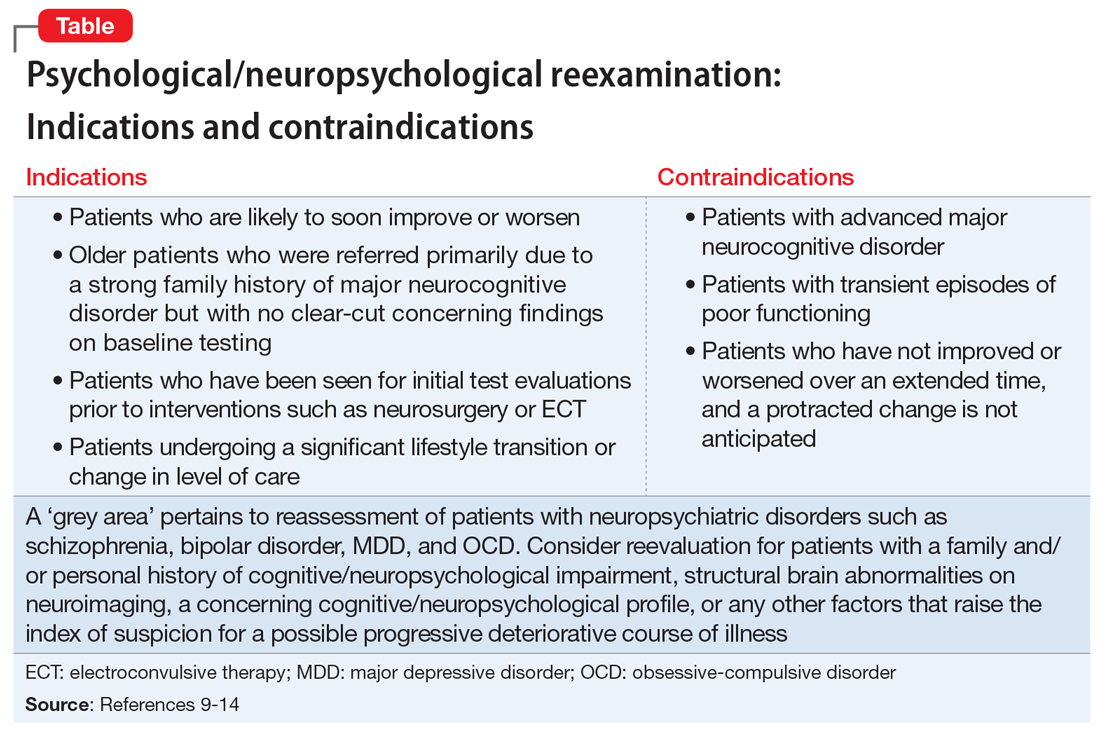

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

1. Schroeder RW, Martin PK, Walling A. Neuropsychological evaluations in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-198.

2. Bucher MA, Suzuki T, Samuel DB. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:51-63.

3. Pollak J. Feedback to the psychodiagnostician: a challenge for assessment psychologists in independent practice. Independent Practitioner: The community of psychologists in independent practice. 2020;40,6-9.

4. Pollak J. To test or not to test: considerations before going forward with psychometric testing. The Clinical Practitioner. 2011;6:5-10.

5. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

6. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(3):227-237.

7. Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

8. Pollak J. Psychodiagnostic testing services: the elusive quest for clinicians. Clinical Psychiatry News. Published October 18, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/210439/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/psychodiagnostic-testing-services

9. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, et al. Neurocognition in first episode schizophrenia: a meta- analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315-336.

10. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649-654.

11. Szmulewicz AG, Samamé C, Martino DJ, et al. An updated review on the neuropsychological profile of subjects with bipolar disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(5):139-146.

12. Shin NY, Lee TY, Kim, E, et al. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44(6):1121-1130.

13. Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, et al. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):811-819.

14. Mitleman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345-357.

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.