User login

How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The opioid crisis: Treating pregnant women with addiction

Maternal immunization: What does the future hold?

Immunization resources

Current recommended adult (anyone over 18 years old) immunization schedule

ACOG Immunization Champions (ACOG members who have demonstrated exceptional progress in increasing immunization rates among adults and pregnant women in their communities through leadership, innovation, collaboration, and educational activities aimed at following ACOG and CDC guidance.)

Summary of Maternal Immunization Recommendations is a provider resource from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maternal Immunization Toolkit contains materials, including the Vaccines During Pregnancy Poster, to support ObGyns on recommending the influenza vaccine and the Tdap vaccine to all pregnant patients.

Immunization resources

Current recommended adult (anyone over 18 years old) immunization schedule

ACOG Immunization Champions (ACOG members who have demonstrated exceptional progress in increasing immunization rates among adults and pregnant women in their communities through leadership, innovation, collaboration, and educational activities aimed at following ACOG and CDC guidance.)

Summary of Maternal Immunization Recommendations is a provider resource from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maternal Immunization Toolkit contains materials, including the Vaccines During Pregnancy Poster, to support ObGyns on recommending the influenza vaccine and the Tdap vaccine to all pregnant patients.

Immunization resources

Current recommended adult (anyone over 18 years old) immunization schedule

ACOG Immunization Champions (ACOG members who have demonstrated exceptional progress in increasing immunization rates among adults and pregnant women in their communities through leadership, innovation, collaboration, and educational activities aimed at following ACOG and CDC guidance.)

Summary of Maternal Immunization Recommendations is a provider resource from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maternal Immunization Toolkit contains materials, including the Vaccines During Pregnancy Poster, to support ObGyns on recommending the influenza vaccine and the Tdap vaccine to all pregnant patients.

ARRIVE: What are the perinatal and maternal consequences of labor induction at 39 weeks compared with expectant management?

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

- Induction of labor at 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparas, irrespective of Bishop score, seems to be a reasonable option to be included in route of delivery discussions with patients as part of the principle of shared decision-making.

- The data in this trial would suggest that such an approach not only reduces adverse perinatal outcomes but also may reduce the need for subsequent cesarean delivery.

An oath to save lives against a backdrop of growing disparities

Practicing in the field of obstetrics and gynecology affords us a special privilege: we are part of the most important and unforgettable events in our patients’ lives, both in sickness and in health. Along with the great joys we share comes profound responsibility and the recognition that we are only as effective as the team with whom we work. Although we live in a country that is home to some of the best health care systems in the world, the maternal mortality rates and disease burden among women in underserved communities belie this fact. A University of Washington study demonstrated a more than 20-year gap in life expectancy between wealthy and poor communities in the United States from 1980 to 2014.1 Not surprisingly, access to medical care was a contributing factor.

Poverty only partly explains this disparity. Racial differences are at play as well. In 1992, a seminal study by Schoendorf and colleagues2 demonstrated that the death rates of babies born to educated African American parents were higher due to lower birth weights. Concern recently has been amplified, and many lay publications have publicly raised the alarm.3 Several states have started investigating the causes, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, as well as other organizations, are studying possible solutions.

With nearly 50% of US births financed by Medicaid,5 there was great hope that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and expansion of Medicaid would result in improved access and quality of health care for underserved patients; however, it has become apparent that coverage did not confer improved access to quality care, especially for medical specialties.

Urban and rural poor populations generally seek medical services from safety net clinics staffed by midlevel and physician primary care providers whose tight schedules, documentation demands, and low reimbursement rates are coupled with complex medical and socioeconomic patient populations. While these providers may be skilled in basic primary care, their patients often present with conditions outside their scope of practice. Our country’s growing physician shortage, along with patient location and personal logistics, adds to the challenges for patients and providers alike. And who among us is not asked several times a week, even by our well-insured patients, for a primary care or specialist physician recommendation? The barriers for seeking medical care in rural populations are even greater, as local hospitals and clinics are closing at an alarming rate.

Alumni at work

Communities of physicians across the country recognize both the access problem and the potential to create solutions. Organizations such as Project ECHO, launched in 2003 through the University of New Mexico, connect rural providers with university physicians to aid in treatment of hepatitis C and other illnesses.

As the date for implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act approached, a group of medical school alumni leaders recognized that we could come together and offer our services to address growing health care disparities. Galvanized by the challenge, the Medical Alumni Volunteer Expert Network, or MAVEN Project, was, in our parlance, “born.”

While the concept of the MAVEN Project was germinating, we interviewed numerous colleagues for advice and input and were struck by their desire—especially among the newly retired—to continue to give back. Medicine is a calling, not just a job, and for many of us the joy of helping—the exhilaration of that first birth that sold us on our specialty—gives us meaning and purpose. Many physicians who had left full-time clinical medicine missed the collegiality of the “doctors’ lounge.” Throughout our careers, we are part of a cohort: our medical school class, our residency partners, our hospital staff—we all crave community. With 36% of US physicians older than age 55 and 240,000 retired doctors in the country, we realized a motivated, previously untapped workforce could be marshaled to form a community to serve the most vulnerable among us.5

At the same time, telemedicine had come into its own. Simple technology could enable us to see each other on smartphones and computers and even perform portions of a physical examination from afar.

We realized we could marry opportunity (the workforce), need (underserved populations across the country), and technology. The Harvard Medical School Center Primary Care supported a feasibility study, and the MAVEN Project began “seeing” patients in 2016.

What happens when a safety net clinic receives a donation of life-altering oral diabetes medications but their providers lack the expertise to use them appropriately? A closet full of drugs. That is what the MAVEN Project discovered at one of our partner clinics. Enter our volunteer endocrinologist. She consulted with the medical team, reviewed how each medication should be prescribed and monitored, and gave instructions on which patients with diabetes would benefit the most from them.

The closet is emptying, the clinic providers are confidently prescribing the newest therapies, and patients are enjoying improved blood sugars and quality of life!

A model of hope

The MAVEN Project matches physician volunteers with safety net clinics serving patients in need and provides malpractice insurance and a Health Information Portability and Accountability Act–compliant technology platform to facilitate remote communication. Our volunteers mentor and educate primary care providers in the field and offer both immediate and asynchronous advisory consults. Clinic providers can group cases for discussion, ask urgent questions, or receive advice and support for the day-to-day challenges facing clinicians today. Clinics choose educational topics, focusing on tools needed for patient care rather than esoteric mechanisms of disease. Patients receive best-in-class care conveniently and locally, and by making volunteering easy, we build partnerships that augment patient and provider satisfaction, support long-term capacity building, and improve service delivery.

Our volunteer physicians now represent more than 30 medical specialties and 25 medical schools, and we have completed more than 2,000 consultations to date. Our clinics are located in 6 states (California, Florida, Massachusetts, New York, South Dakota, and Washington), and thanks to our model, physician state of licensure is not an impediment to volunteering. Several colleagues in our specialty are providing advice in women’s health.

Driving innovative solutions

Elizabeth Kopin, MD, an ObGyn who practiced for 28 years in Worcester, Massachusetts, and volunteers for the MAVEN Project, eloquently described in correspondence with Project coordinators the spirit that embodies the pursuit of medicine and the organization’s mission. As Dr. Kopin stated, “The driving force behind my entering medicine was to help people in an essential and meaningful way. I was especially driven to participate in the care of women. I wanted to gain knowledge and skills to help women with health care throughout their lives.”

Dr. Kopin’s capacity to care for patients in the clinic and hospital was progressively reduced as her multiple sclerosis advanced. As a result, she retired from clinical practice, but her desire to participate and contribute to medicine with the passion with which she entered it remained.

Her father was an internist who started a charitable clinic in Georgia. Like her father, Dr. Kopin began her medical career in academic medicine. Her father felt that his last 15 years in medicine were the most meaningful of his career because of his work with underserved populations. Dr. Kopin is following in his footsteps. For her, “Looking for a telehealth vehicle helping communities in need gives me the opportunity to use my abilities in the best way possible.” Dr. Kopin also stated, “Helping the underserved was something I wanted to devote my time to and The MAVEN Project has given me that possibility.”

We like to think of ourselves as Match. com meets the Peace Corps, with the goal to reach underserved patients in all 50 states in both rural and urban communities. We ask for as little as 4 hours of your time per month, and all you need is a computer or smartphone and a medical license. We welcome volunteers in active or part-time practice, academics, and industry: your years of wisdom are invaluable.

The vast complexities of the US health care system are by no measure easy to address, but standing by and allowing a fractured system to rupture is not an option. Each of us has an expertise and an opportunity to make incremental steps to ensure that those who need health care do not slip through the cracks. Dr. Kopin and I are fortunate to have a skill to help others and, in the MAVEN Project, a robust, dedicated network of individuals who share our vision.

There are many who have and continue to inspire a guiding conscience to serve beyond oneself. George H.W. Bush said it best when explaining why he founded the Points of Light organization nearly 3 decades ago6:

I have pursued life itself over many years now and with varying degrees of happiness. Some of my happiness still comes from trying to be in my own small way a true “point of light.” I believe I was right when I said, as President, there can be no definition of a successful life that does not include service to others. So I do that now, and I gain happiness. I do not seek a Pulitzer Prize. I do not want press attention…. I have found happiness. I no longer pursue it, for it is mine.

Please join us on our mission!

How to join

We are actively seeking specialty and primary care physicians to provide advisory consultations, mentorship, and education via telehealth technology. We welcome physician volunteers who:

- are newly retired, semi-retired, in industry, or in clinical practice

- have a minimum of 2 years of clinical practice experience

- have been active in the medical community in the past 3 years

- have an active or volunteer US medical license (any state)

- are able to provide 3 professional references

- are willing to commit a minimum of 4 hours per month for 6 months.

Visit us online to complete our physician volunteer inquiry form (https://www.mavenproject.org/work-with-us/#wwu-volunteer-as-a-physician-lightblue).

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, et al. Inequalities in life expectancy among US counties, 1980 to 2014: temporal trends and key drivers. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1003-1011.

- Schoendorf KC, Hogue CJ, Kleinman JC, et al. Mortality among infants of black as compared with white college-educated parents. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1522-1526.

- Villarosa L. Why America's black mothers and babies are in a life-or-death crisis. New York Times. April 11, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Smith VK, Gifford K, Ellis E, et al; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; The National Association of Medical Directors. Implementing coverage and payment initiatives: results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2016 and 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Implementing-Coverage-and-Payment-Initiatives. Published October 2006. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. 2016 Physician Specialty Data Report: Executive Summary. https://www.aamc.org/download/471786/data/2016physicianspecialtydatareportexecutivesummary.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Miller RW. Jenna Bush Hager shares George H.W. Bush 'point of light' letter after Trump jab. USA TODAY. July 7, 2018. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2018/07/07/jenna-bush-hager-shares-george-h-w-bush-point-light-letter-donald-trump/765248002/. Accessed August 14, 2018.

Practicing in the field of obstetrics and gynecology affords us a special privilege: we are part of the most important and unforgettable events in our patients’ lives, both in sickness and in health. Along with the great joys we share comes profound responsibility and the recognition that we are only as effective as the team with whom we work. Although we live in a country that is home to some of the best health care systems in the world, the maternal mortality rates and disease burden among women in underserved communities belie this fact. A University of Washington study demonstrated a more than 20-year gap in life expectancy between wealthy and poor communities in the United States from 1980 to 2014.1 Not surprisingly, access to medical care was a contributing factor.

Poverty only partly explains this disparity. Racial differences are at play as well. In 1992, a seminal study by Schoendorf and colleagues2 demonstrated that the death rates of babies born to educated African American parents were higher due to lower birth weights. Concern recently has been amplified, and many lay publications have publicly raised the alarm.3 Several states have started investigating the causes, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, as well as other organizations, are studying possible solutions.

With nearly 50% of US births financed by Medicaid,5 there was great hope that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and expansion of Medicaid would result in improved access and quality of health care for underserved patients; however, it has become apparent that coverage did not confer improved access to quality care, especially for medical specialties.

Urban and rural poor populations generally seek medical services from safety net clinics staffed by midlevel and physician primary care providers whose tight schedules, documentation demands, and low reimbursement rates are coupled with complex medical and socioeconomic patient populations. While these providers may be skilled in basic primary care, their patients often present with conditions outside their scope of practice. Our country’s growing physician shortage, along with patient location and personal logistics, adds to the challenges for patients and providers alike. And who among us is not asked several times a week, even by our well-insured patients, for a primary care or specialist physician recommendation? The barriers for seeking medical care in rural populations are even greater, as local hospitals and clinics are closing at an alarming rate.

Alumni at work

Communities of physicians across the country recognize both the access problem and the potential to create solutions. Organizations such as Project ECHO, launched in 2003 through the University of New Mexico, connect rural providers with university physicians to aid in treatment of hepatitis C and other illnesses.

As the date for implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act approached, a group of medical school alumni leaders recognized that we could come together and offer our services to address growing health care disparities. Galvanized by the challenge, the Medical Alumni Volunteer Expert Network, or MAVEN Project, was, in our parlance, “born.”

While the concept of the MAVEN Project was germinating, we interviewed numerous colleagues for advice and input and were struck by their desire—especially among the newly retired—to continue to give back. Medicine is a calling, not just a job, and for many of us the joy of helping—the exhilaration of that first birth that sold us on our specialty—gives us meaning and purpose. Many physicians who had left full-time clinical medicine missed the collegiality of the “doctors’ lounge.” Throughout our careers, we are part of a cohort: our medical school class, our residency partners, our hospital staff—we all crave community. With 36% of US physicians older than age 55 and 240,000 retired doctors in the country, we realized a motivated, previously untapped workforce could be marshaled to form a community to serve the most vulnerable among us.5

At the same time, telemedicine had come into its own. Simple technology could enable us to see each other on smartphones and computers and even perform portions of a physical examination from afar.

We realized we could marry opportunity (the workforce), need (underserved populations across the country), and technology. The Harvard Medical School Center Primary Care supported a feasibility study, and the MAVEN Project began “seeing” patients in 2016.

What happens when a safety net clinic receives a donation of life-altering oral diabetes medications but their providers lack the expertise to use them appropriately? A closet full of drugs. That is what the MAVEN Project discovered at one of our partner clinics. Enter our volunteer endocrinologist. She consulted with the medical team, reviewed how each medication should be prescribed and monitored, and gave instructions on which patients with diabetes would benefit the most from them.

The closet is emptying, the clinic providers are confidently prescribing the newest therapies, and patients are enjoying improved blood sugars and quality of life!

A model of hope

The MAVEN Project matches physician volunteers with safety net clinics serving patients in need and provides malpractice insurance and a Health Information Portability and Accountability Act–compliant technology platform to facilitate remote communication. Our volunteers mentor and educate primary care providers in the field and offer both immediate and asynchronous advisory consults. Clinic providers can group cases for discussion, ask urgent questions, or receive advice and support for the day-to-day challenges facing clinicians today. Clinics choose educational topics, focusing on tools needed for patient care rather than esoteric mechanisms of disease. Patients receive best-in-class care conveniently and locally, and by making volunteering easy, we build partnerships that augment patient and provider satisfaction, support long-term capacity building, and improve service delivery.

Our volunteer physicians now represent more than 30 medical specialties and 25 medical schools, and we have completed more than 2,000 consultations to date. Our clinics are located in 6 states (California, Florida, Massachusetts, New York, South Dakota, and Washington), and thanks to our model, physician state of licensure is not an impediment to volunteering. Several colleagues in our specialty are providing advice in women’s health.

Driving innovative solutions

Elizabeth Kopin, MD, an ObGyn who practiced for 28 years in Worcester, Massachusetts, and volunteers for the MAVEN Project, eloquently described in correspondence with Project coordinators the spirit that embodies the pursuit of medicine and the organization’s mission. As Dr. Kopin stated, “The driving force behind my entering medicine was to help people in an essential and meaningful way. I was especially driven to participate in the care of women. I wanted to gain knowledge and skills to help women with health care throughout their lives.”

Dr. Kopin’s capacity to care for patients in the clinic and hospital was progressively reduced as her multiple sclerosis advanced. As a result, she retired from clinical practice, but her desire to participate and contribute to medicine with the passion with which she entered it remained.

Her father was an internist who started a charitable clinic in Georgia. Like her father, Dr. Kopin began her medical career in academic medicine. Her father felt that his last 15 years in medicine were the most meaningful of his career because of his work with underserved populations. Dr. Kopin is following in his footsteps. For her, “Looking for a telehealth vehicle helping communities in need gives me the opportunity to use my abilities in the best way possible.” Dr. Kopin also stated, “Helping the underserved was something I wanted to devote my time to and The MAVEN Project has given me that possibility.”

We like to think of ourselves as Match. com meets the Peace Corps, with the goal to reach underserved patients in all 50 states in both rural and urban communities. We ask for as little as 4 hours of your time per month, and all you need is a computer or smartphone and a medical license. We welcome volunteers in active or part-time practice, academics, and industry: your years of wisdom are invaluable.

The vast complexities of the US health care system are by no measure easy to address, but standing by and allowing a fractured system to rupture is not an option. Each of us has an expertise and an opportunity to make incremental steps to ensure that those who need health care do not slip through the cracks. Dr. Kopin and I are fortunate to have a skill to help others and, in the MAVEN Project, a robust, dedicated network of individuals who share our vision.

There are many who have and continue to inspire a guiding conscience to serve beyond oneself. George H.W. Bush said it best when explaining why he founded the Points of Light organization nearly 3 decades ago6:

I have pursued life itself over many years now and with varying degrees of happiness. Some of my happiness still comes from trying to be in my own small way a true “point of light.” I believe I was right when I said, as President, there can be no definition of a successful life that does not include service to others. So I do that now, and I gain happiness. I do not seek a Pulitzer Prize. I do not want press attention…. I have found happiness. I no longer pursue it, for it is mine.

Please join us on our mission!

How to join

We are actively seeking specialty and primary care physicians to provide advisory consultations, mentorship, and education via telehealth technology. We welcome physician volunteers who:

- are newly retired, semi-retired, in industry, or in clinical practice

- have a minimum of 2 years of clinical practice experience

- have been active in the medical community in the past 3 years

- have an active or volunteer US medical license (any state)

- are able to provide 3 professional references

- are willing to commit a minimum of 4 hours per month for 6 months.

Visit us online to complete our physician volunteer inquiry form (https://www.mavenproject.org/work-with-us/#wwu-volunteer-as-a-physician-lightblue).

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Practicing in the field of obstetrics and gynecology affords us a special privilege: we are part of the most important and unforgettable events in our patients’ lives, both in sickness and in health. Along with the great joys we share comes profound responsibility and the recognition that we are only as effective as the team with whom we work. Although we live in a country that is home to some of the best health care systems in the world, the maternal mortality rates and disease burden among women in underserved communities belie this fact. A University of Washington study demonstrated a more than 20-year gap in life expectancy between wealthy and poor communities in the United States from 1980 to 2014.1 Not surprisingly, access to medical care was a contributing factor.

Poverty only partly explains this disparity. Racial differences are at play as well. In 1992, a seminal study by Schoendorf and colleagues2 demonstrated that the death rates of babies born to educated African American parents were higher due to lower birth weights. Concern recently has been amplified, and many lay publications have publicly raised the alarm.3 Several states have started investigating the causes, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, as well as other organizations, are studying possible solutions.

With nearly 50% of US births financed by Medicaid,5 there was great hope that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and expansion of Medicaid would result in improved access and quality of health care for underserved patients; however, it has become apparent that coverage did not confer improved access to quality care, especially for medical specialties.

Urban and rural poor populations generally seek medical services from safety net clinics staffed by midlevel and physician primary care providers whose tight schedules, documentation demands, and low reimbursement rates are coupled with complex medical and socioeconomic patient populations. While these providers may be skilled in basic primary care, their patients often present with conditions outside their scope of practice. Our country’s growing physician shortage, along with patient location and personal logistics, adds to the challenges for patients and providers alike. And who among us is not asked several times a week, even by our well-insured patients, for a primary care or specialist physician recommendation? The barriers for seeking medical care in rural populations are even greater, as local hospitals and clinics are closing at an alarming rate.

Alumni at work

Communities of physicians across the country recognize both the access problem and the potential to create solutions. Organizations such as Project ECHO, launched in 2003 through the University of New Mexico, connect rural providers with university physicians to aid in treatment of hepatitis C and other illnesses.

As the date for implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act approached, a group of medical school alumni leaders recognized that we could come together and offer our services to address growing health care disparities. Galvanized by the challenge, the Medical Alumni Volunteer Expert Network, or MAVEN Project, was, in our parlance, “born.”

While the concept of the MAVEN Project was germinating, we interviewed numerous colleagues for advice and input and were struck by their desire—especially among the newly retired—to continue to give back. Medicine is a calling, not just a job, and for many of us the joy of helping—the exhilaration of that first birth that sold us on our specialty—gives us meaning and purpose. Many physicians who had left full-time clinical medicine missed the collegiality of the “doctors’ lounge.” Throughout our careers, we are part of a cohort: our medical school class, our residency partners, our hospital staff—we all crave community. With 36% of US physicians older than age 55 and 240,000 retired doctors in the country, we realized a motivated, previously untapped workforce could be marshaled to form a community to serve the most vulnerable among us.5

At the same time, telemedicine had come into its own. Simple technology could enable us to see each other on smartphones and computers and even perform portions of a physical examination from afar.

We realized we could marry opportunity (the workforce), need (underserved populations across the country), and technology. The Harvard Medical School Center Primary Care supported a feasibility study, and the MAVEN Project began “seeing” patients in 2016.

What happens when a safety net clinic receives a donation of life-altering oral diabetes medications but their providers lack the expertise to use them appropriately? A closet full of drugs. That is what the MAVEN Project discovered at one of our partner clinics. Enter our volunteer endocrinologist. She consulted with the medical team, reviewed how each medication should be prescribed and monitored, and gave instructions on which patients with diabetes would benefit the most from them.

The closet is emptying, the clinic providers are confidently prescribing the newest therapies, and patients are enjoying improved blood sugars and quality of life!

A model of hope

The MAVEN Project matches physician volunteers with safety net clinics serving patients in need and provides malpractice insurance and a Health Information Portability and Accountability Act–compliant technology platform to facilitate remote communication. Our volunteers mentor and educate primary care providers in the field and offer both immediate and asynchronous advisory consults. Clinic providers can group cases for discussion, ask urgent questions, or receive advice and support for the day-to-day challenges facing clinicians today. Clinics choose educational topics, focusing on tools needed for patient care rather than esoteric mechanisms of disease. Patients receive best-in-class care conveniently and locally, and by making volunteering easy, we build partnerships that augment patient and provider satisfaction, support long-term capacity building, and improve service delivery.

Our volunteer physicians now represent more than 30 medical specialties and 25 medical schools, and we have completed more than 2,000 consultations to date. Our clinics are located in 6 states (California, Florida, Massachusetts, New York, South Dakota, and Washington), and thanks to our model, physician state of licensure is not an impediment to volunteering. Several colleagues in our specialty are providing advice in women’s health.

Driving innovative solutions

Elizabeth Kopin, MD, an ObGyn who practiced for 28 years in Worcester, Massachusetts, and volunteers for the MAVEN Project, eloquently described in correspondence with Project coordinators the spirit that embodies the pursuit of medicine and the organization’s mission. As Dr. Kopin stated, “The driving force behind my entering medicine was to help people in an essential and meaningful way. I was especially driven to participate in the care of women. I wanted to gain knowledge and skills to help women with health care throughout their lives.”

Dr. Kopin’s capacity to care for patients in the clinic and hospital was progressively reduced as her multiple sclerosis advanced. As a result, she retired from clinical practice, but her desire to participate and contribute to medicine with the passion with which she entered it remained.

Her father was an internist who started a charitable clinic in Georgia. Like her father, Dr. Kopin began her medical career in academic medicine. Her father felt that his last 15 years in medicine were the most meaningful of his career because of his work with underserved populations. Dr. Kopin is following in his footsteps. For her, “Looking for a telehealth vehicle helping communities in need gives me the opportunity to use my abilities in the best way possible.” Dr. Kopin also stated, “Helping the underserved was something I wanted to devote my time to and The MAVEN Project has given me that possibility.”

We like to think of ourselves as Match. com meets the Peace Corps, with the goal to reach underserved patients in all 50 states in both rural and urban communities. We ask for as little as 4 hours of your time per month, and all you need is a computer or smartphone and a medical license. We welcome volunteers in active or part-time practice, academics, and industry: your years of wisdom are invaluable.

The vast complexities of the US health care system are by no measure easy to address, but standing by and allowing a fractured system to rupture is not an option. Each of us has an expertise and an opportunity to make incremental steps to ensure that those who need health care do not slip through the cracks. Dr. Kopin and I are fortunate to have a skill to help others and, in the MAVEN Project, a robust, dedicated network of individuals who share our vision.

There are many who have and continue to inspire a guiding conscience to serve beyond oneself. George H.W. Bush said it best when explaining why he founded the Points of Light organization nearly 3 decades ago6:

I have pursued life itself over many years now and with varying degrees of happiness. Some of my happiness still comes from trying to be in my own small way a true “point of light.” I believe I was right when I said, as President, there can be no definition of a successful life that does not include service to others. So I do that now, and I gain happiness. I do not seek a Pulitzer Prize. I do not want press attention…. I have found happiness. I no longer pursue it, for it is mine.

Please join us on our mission!

How to join

We are actively seeking specialty and primary care physicians to provide advisory consultations, mentorship, and education via telehealth technology. We welcome physician volunteers who:

- are newly retired, semi-retired, in industry, or in clinical practice

- have a minimum of 2 years of clinical practice experience

- have been active in the medical community in the past 3 years

- have an active or volunteer US medical license (any state)

- are able to provide 3 professional references

- are willing to commit a minimum of 4 hours per month for 6 months.

Visit us online to complete our physician volunteer inquiry form (https://www.mavenproject.org/work-with-us/#wwu-volunteer-as-a-physician-lightblue).

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, et al. Inequalities in life expectancy among US counties, 1980 to 2014: temporal trends and key drivers. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1003-1011.

- Schoendorf KC, Hogue CJ, Kleinman JC, et al. Mortality among infants of black as compared with white college-educated parents. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1522-1526.

- Villarosa L. Why America's black mothers and babies are in a life-or-death crisis. New York Times. April 11, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Smith VK, Gifford K, Ellis E, et al; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; The National Association of Medical Directors. Implementing coverage and payment initiatives: results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2016 and 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Implementing-Coverage-and-Payment-Initiatives. Published October 2006. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. 2016 Physician Specialty Data Report: Executive Summary. https://www.aamc.org/download/471786/data/2016physicianspecialtydatareportexecutivesummary.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Miller RW. Jenna Bush Hager shares George H.W. Bush 'point of light' letter after Trump jab. USA TODAY. July 7, 2018. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2018/07/07/jenna-bush-hager-shares-george-h-w-bush-point-light-letter-donald-trump/765248002/. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, et al. Inequalities in life expectancy among US counties, 1980 to 2014: temporal trends and key drivers. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1003-1011.

- Schoendorf KC, Hogue CJ, Kleinman JC, et al. Mortality among infants of black as compared with white college-educated parents. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1522-1526.

- Villarosa L. Why America's black mothers and babies are in a life-or-death crisis. New York Times. April 11, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Smith VK, Gifford K, Ellis E, et al; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; The National Association of Medical Directors. Implementing coverage and payment initiatives: results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2016 and 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Implementing-Coverage-and-Payment-Initiatives. Published October 2006. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. 2016 Physician Specialty Data Report: Executive Summary. https://www.aamc.org/download/471786/data/2016physicianspecialtydatareportexecutivesummary.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Miller RW. Jenna Bush Hager shares George H.W. Bush 'point of light' letter after Trump jab. USA TODAY. July 7, 2018. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2018/07/07/jenna-bush-hager-shares-george-h-w-bush-point-light-letter-donald-trump/765248002/. Accessed August 14, 2018.

Does hypertensive disease of pregnancy increase future risk of CVD?

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

- Patients who develop preeclampsia or gestational hypertension in their first pregnancy should be more carefully screened for subsequent development of CVD

Is the most effective emergency contraception easily obtained at US pharmacies?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

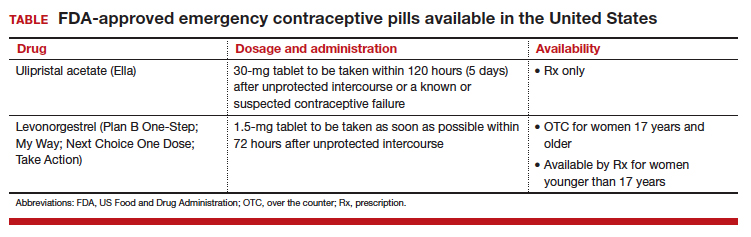

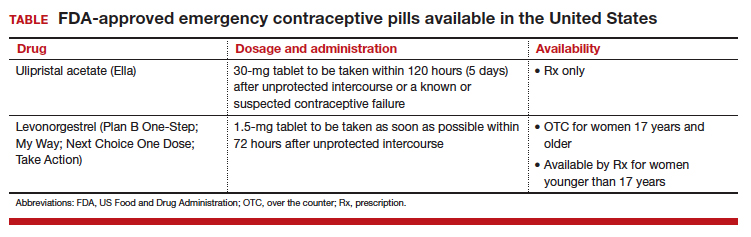

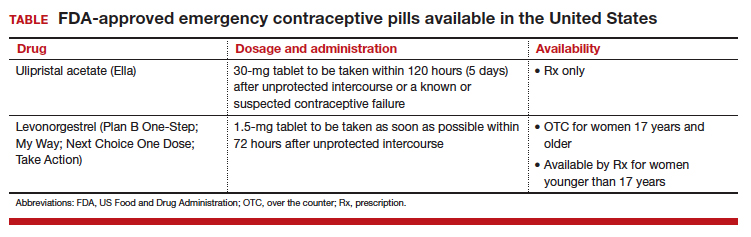

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

Contraceptive considerations for women with headache and migraine

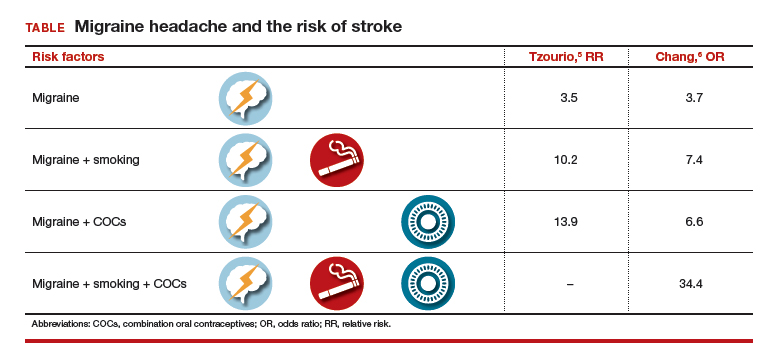

The use of hormonal contraception in women with headaches, especially migraine headaches, is an important topic. Approximately 43% of women in the United States report migraines.1 Roughly the same percentage of reproductive-aged women use hormonal contraception.2 Data suggest that all migraineurs have some increased risk of stroke. Therefore, can women with migraine headaches use combination hormonal contraception? And can women with severe headaches that are nonmigrainous use combination hormonal contraception? Let’s examine available data to help us answer these questions.

Risk factors for stroke

Migraine without aura is the most common subset, but migraine with aura is more problematic relative to the increased incidence of stroke.1

A migraine aura is visual 90% of the time.1 Symptoms can include flickering lights, spots, zigzag lines, a sense of pins and needles, or dysphasic speech. Aura precedes the headache and usually resolves within 1 hour after the aura begins.

In addition to migraine headaches, risk factors for stroke include increasing age, hypertension, the use of combination oral contraceptives (COCs), the contraceptive patch and ring, and smoking.1