User login

Optimize the medical treatment of endometriosis—Use all available medications

CASE Endometriosis pain increases despite hormonal treatment

A 25-year-old woman (G0) with severe dysmenorrhea had a laparoscopy showing endometriosis in the cul-de-sac and a peritoneal window near the left uterosacral ligament. Biopsy of a cul-de-sac lesion showed endometriosis on histopathology. The patient was treated with a continuous low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive. Initially, the treatment helped relieve her pain symptoms. Over the next year, while on that treatment, her pain gradually increased in severity until it was disabling. At an office visit, the primary clinician renewed the estrogen-progestin contraceptive for another year, even though it was not relieving the patient’s pain. The patient sought a second opinion.

We are the experts in the management of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

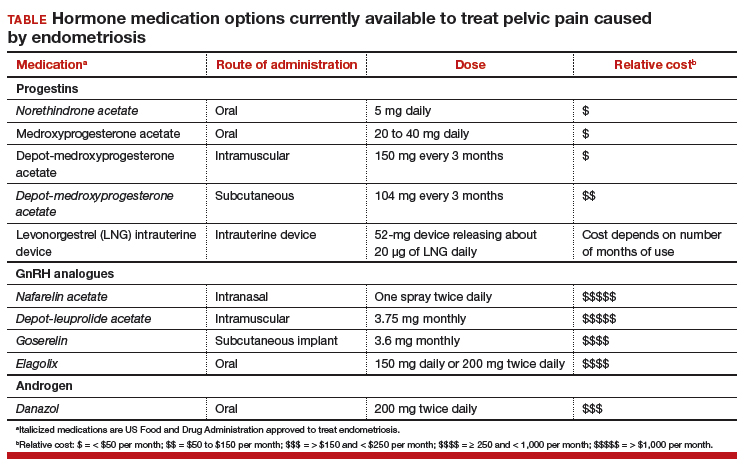

Women’s health clinicians are the specialists best trained to care for patients with severe pain caused by endometriosis. Low-dose continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed as a first-line hormonal treatment for pain caused by endometriosis. My observation is that estrogen-progestincontraceptives are often effective when initially prescribed, but with continued use over years, pain often recurs. Estrogen is known to stimulate endometriosis disease activity. Progestins at high doses suppress endometriosis disease activity. However, endometriosis implants often manifest decreased responsiveness to progestins, permitting the estrogen in the combination contraceptive to exert its disease-stimulating effect.1,2 I frequently see women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, who initially had a significant decrease in pain with continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment but who develop increasing pain with continued use of the medication. In this clinical situation, it is useful to consider stopping the estrogen-progestin therapy and to prescribe a hormone with a different mechanism of action (TABLE).

Progestin-only medications

Progestin-only medications are often effective in the treatment of pain caused by endometriosis. High-dose progestin-only medications suppress pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thereby suppressing ovarian synthesis of estrogen, resulting in low circulating levels of estrogen. This removes the estrogen stimulus that exacerbates endometriosis disease activity. High-dose progestins also directly suppress cellular activity in endometriosis implants. High-dose progestins often overcome the relative resistance of endometriosis lesions to progestin suppression of disease activity. Hence, high-dose progestin-only medications have two mechanisms of action: suppression of estrogen synthesis through pituitary suppression of LH and FSH, and direct inhibition of cellular activity in the endometriosis lesions. High-dose progestin-only treatments include:

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily

- oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 20 to 40 mg daily

- subcutaneous, or depot MPA

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD).

In my practice, I frequently use oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In one randomized trial, 90 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were randomly assigned to treatment with norethindrone acetate 2.5 mg daily or an estrogen-progestin contraceptive. After 12 months of treatment, satisfaction with treatment was reported by 73% and 62% of the women in the norethindrone acetate and estrogen-progestin groups, respectively.3 The most common adverse effects reported by women taking norethindrone acetate were weight gain (27%) and decreased libido (9%).

Oral MPA at doses of 30 mg to 100 mg daily has been reported to be effective for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. MPA treatment can induce atrophy and pseudodecidualization in endometrium and endometriosis implants. In my practice I typically prescribe doses in the range of 20 mg to 40 mg daily. With oral MPA treatment, continued uterine bleeding may occur in up to 30% of women, somewhat limiting its efficacy.4–7

Subcutaneous and depot MPA have been reported to be effective in the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.4,8 In some resource-limited countries, depot MPA may be the most available progestin for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

The LNG-IUD, inserted after surgery for endometriosis, has been reported to result in decreased pelvic pain in studies with a modest number of participants.9–11

GnRH analogue medications

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, including both GnRH agonists (nafarelin, leuprolide, and goserelin) and GnRH antagonists (elagolix) reduce pelvic pain caused by endometriosis by suppressing pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, thereby reducing ovarian synthesis of estradiol. In the absence of estradiol stimulation, cellular activity in endometriosis lesions decreases and pain symptoms improve. In my practice, I frequently use either nafarelin12 or leuprolide acetate depot plus norethindrone add-back.13 I generally avoid the use of leuprolide depot monotherapy because in many women it causes severe vasomotor symptoms.

At standard doses, nafarelin therapy generally results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, a “sweet spot” associated with modest vasomotor symptoms and reduced cellular activity in endometriosis implants.12,14 In many women who become amenorrheic on nafarelin two sprays daily, the dose can be reduced with maintenance of pain control and ovarian suppression.15 Leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 5 to 10 pg/mL, causing severe vasomotor symptoms and reduction in cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. To reduce the adverse effects of leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy, I generally initiate concomitant add-back therapy with norethindrone acetate.13 A little recognized pharmacokinetic observation is that a very small amount of norethindrone acetate, generally less than 1%, is metabolized to ethinyl estradiol.16

The oral GnRH antagonist, elagolix, 150 mg daily for up to 24 months or 200 mg twice daily for 6 months, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2018. It is now available in pharmacies. Elagolix treatment results in significant reduction in pain caused by endometriosis, but only moderately bothersome vasomotor symptoms.17,18 Elagolix likely will become a widely used medication because of the simplicity of oral administration, efficacy against endometriosis, and acceptable adverse-effect profile. A major disadvantage of the GnRH analogue-class of medications is that they are more expensive than the progestin medications mentioned above. Among the GnRH analogue class of medications, elagolix and goserelin are the least expensive.

Androgens

Estrogen stimulates cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Androgen and high-dose progestins inhibit cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Danazol, an attenuated androgen and a progestin is effectivein treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.19,20 However, many women decline to use danazol because it is often associated with weight gain. As an androgen, danazol can permanently change a woman’s voice pitch and should not be used by professional singers or speech therapists.

Aromatase Inhibitors

Estrogen is a critically important stimulus of cell activity in endometriosis lesions. Aromatase inhibitors, which block the synthesis of estrogen, have been explored in the treatment of endometriosis that has proven to be resistant to other therapies. Although the combination of an aromatase inhibitor plus a high-dose progestin or GnRH analogue may be effective, more data are needed before widely using the aromatase inhibitors in clinical practice.21

Don’t get stuck in a rut

When treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, if the patient’s hormone regimen is not working, prescribe a medication from another class of hormones. In the case presented above, a woman with pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis reported inadequate control of her pain symptoms with a continuous estrogen-progestin medication. Her physician prescribed another year of the same estrogen-progestin medication. Instead of renewing the medication, the physician could have offered the patient a hormone medication from another drug class: 1) progestin only, 2) GnRH analogue, or 3) danazol. By using every available hormonal agent, physicians will improve the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Millions of women in our country have pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. They are counting on us, women’s health specialists, to effectively treat their disease.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Patel BG, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor RN. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):623–632.

- Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):36–43.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

- Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD002122.

- Moghissi KS, Boyce CR. Management of endometriosis with oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47(3):265–267.

- Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Rönnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1(1):13–23.

- Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 pt 1):323–327.

- Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leu-prolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314–325.

- Abou-Setta AM, Houston B, Al-Inany HG, Farquhar C. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD005072.

- Tanmahasamut P, Rattanachaiyanont M, Angsuwathana S, Techatraisak K, Indhavivadhana S, Leerasiri P. Postoperative levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for pelvic endometriosis-pain: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):519–526.

- Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273–279.

- Henzl MR, Corson SL, Moghissi K, Buttram VC, Berqvist C, Jacobsen J. Administration of nasal nafarelin as compared with oral danazol for endo-metriosis. A multicenter double-blind comparative clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(8):485–489.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 91(1):16–24.

- Barbieri RL. Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(2):740–745.

- Hull ME, Barbieri RL. Nafarelin in the treatment of endometriosis. Dose management. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;37(4):263–264.

- Barbieri RL, Petro Z, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. Aromatization of norethindrone to ethinyl estradiol by human placental microsomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(2):299–303.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28–40.

- Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):147–160.

- Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000068.

- Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Danazol: endocrine pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(4):453–463.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

CASE Endometriosis pain increases despite hormonal treatment

A 25-year-old woman (G0) with severe dysmenorrhea had a laparoscopy showing endometriosis in the cul-de-sac and a peritoneal window near the left uterosacral ligament. Biopsy of a cul-de-sac lesion showed endometriosis on histopathology. The patient was treated with a continuous low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive. Initially, the treatment helped relieve her pain symptoms. Over the next year, while on that treatment, her pain gradually increased in severity until it was disabling. At an office visit, the primary clinician renewed the estrogen-progestin contraceptive for another year, even though it was not relieving the patient’s pain. The patient sought a second opinion.

We are the experts in the management of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

Women’s health clinicians are the specialists best trained to care for patients with severe pain caused by endometriosis. Low-dose continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed as a first-line hormonal treatment for pain caused by endometriosis. My observation is that estrogen-progestincontraceptives are often effective when initially prescribed, but with continued use over years, pain often recurs. Estrogen is known to stimulate endometriosis disease activity. Progestins at high doses suppress endometriosis disease activity. However, endometriosis implants often manifest decreased responsiveness to progestins, permitting the estrogen in the combination contraceptive to exert its disease-stimulating effect.1,2 I frequently see women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, who initially had a significant decrease in pain with continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment but who develop increasing pain with continued use of the medication. In this clinical situation, it is useful to consider stopping the estrogen-progestin therapy and to prescribe a hormone with a different mechanism of action (TABLE).

Progestin-only medications

Progestin-only medications are often effective in the treatment of pain caused by endometriosis. High-dose progestin-only medications suppress pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thereby suppressing ovarian synthesis of estrogen, resulting in low circulating levels of estrogen. This removes the estrogen stimulus that exacerbates endometriosis disease activity. High-dose progestins also directly suppress cellular activity in endometriosis implants. High-dose progestins often overcome the relative resistance of endometriosis lesions to progestin suppression of disease activity. Hence, high-dose progestin-only medications have two mechanisms of action: suppression of estrogen synthesis through pituitary suppression of LH and FSH, and direct inhibition of cellular activity in the endometriosis lesions. High-dose progestin-only treatments include:

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily

- oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 20 to 40 mg daily

- subcutaneous, or depot MPA

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD).

In my practice, I frequently use oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In one randomized trial, 90 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were randomly assigned to treatment with norethindrone acetate 2.5 mg daily or an estrogen-progestin contraceptive. After 12 months of treatment, satisfaction with treatment was reported by 73% and 62% of the women in the norethindrone acetate and estrogen-progestin groups, respectively.3 The most common adverse effects reported by women taking norethindrone acetate were weight gain (27%) and decreased libido (9%).

Oral MPA at doses of 30 mg to 100 mg daily has been reported to be effective for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. MPA treatment can induce atrophy and pseudodecidualization in endometrium and endometriosis implants. In my practice I typically prescribe doses in the range of 20 mg to 40 mg daily. With oral MPA treatment, continued uterine bleeding may occur in up to 30% of women, somewhat limiting its efficacy.4–7

Subcutaneous and depot MPA have been reported to be effective in the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.4,8 In some resource-limited countries, depot MPA may be the most available progestin for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

The LNG-IUD, inserted after surgery for endometriosis, has been reported to result in decreased pelvic pain in studies with a modest number of participants.9–11

GnRH analogue medications

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, including both GnRH agonists (nafarelin, leuprolide, and goserelin) and GnRH antagonists (elagolix) reduce pelvic pain caused by endometriosis by suppressing pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, thereby reducing ovarian synthesis of estradiol. In the absence of estradiol stimulation, cellular activity in endometriosis lesions decreases and pain symptoms improve. In my practice, I frequently use either nafarelin12 or leuprolide acetate depot plus norethindrone add-back.13 I generally avoid the use of leuprolide depot monotherapy because in many women it causes severe vasomotor symptoms.

At standard doses, nafarelin therapy generally results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, a “sweet spot” associated with modest vasomotor symptoms and reduced cellular activity in endometriosis implants.12,14 In many women who become amenorrheic on nafarelin two sprays daily, the dose can be reduced with maintenance of pain control and ovarian suppression.15 Leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 5 to 10 pg/mL, causing severe vasomotor symptoms and reduction in cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. To reduce the adverse effects of leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy, I generally initiate concomitant add-back therapy with norethindrone acetate.13 A little recognized pharmacokinetic observation is that a very small amount of norethindrone acetate, generally less than 1%, is metabolized to ethinyl estradiol.16

The oral GnRH antagonist, elagolix, 150 mg daily for up to 24 months or 200 mg twice daily for 6 months, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2018. It is now available in pharmacies. Elagolix treatment results in significant reduction in pain caused by endometriosis, but only moderately bothersome vasomotor symptoms.17,18 Elagolix likely will become a widely used medication because of the simplicity of oral administration, efficacy against endometriosis, and acceptable adverse-effect profile. A major disadvantage of the GnRH analogue-class of medications is that they are more expensive than the progestin medications mentioned above. Among the GnRH analogue class of medications, elagolix and goserelin are the least expensive.

Androgens

Estrogen stimulates cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Androgen and high-dose progestins inhibit cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Danazol, an attenuated androgen and a progestin is effectivein treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.19,20 However, many women decline to use danazol because it is often associated with weight gain. As an androgen, danazol can permanently change a woman’s voice pitch and should not be used by professional singers or speech therapists.

Aromatase Inhibitors

Estrogen is a critically important stimulus of cell activity in endometriosis lesions. Aromatase inhibitors, which block the synthesis of estrogen, have been explored in the treatment of endometriosis that has proven to be resistant to other therapies. Although the combination of an aromatase inhibitor plus a high-dose progestin or GnRH analogue may be effective, more data are needed before widely using the aromatase inhibitors in clinical practice.21

Don’t get stuck in a rut

When treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, if the patient’s hormone regimen is not working, prescribe a medication from another class of hormones. In the case presented above, a woman with pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis reported inadequate control of her pain symptoms with a continuous estrogen-progestin medication. Her physician prescribed another year of the same estrogen-progestin medication. Instead of renewing the medication, the physician could have offered the patient a hormone medication from another drug class: 1) progestin only, 2) GnRH analogue, or 3) danazol. By using every available hormonal agent, physicians will improve the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Millions of women in our country have pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. They are counting on us, women’s health specialists, to effectively treat their disease.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Endometriosis pain increases despite hormonal treatment

A 25-year-old woman (G0) with severe dysmenorrhea had a laparoscopy showing endometriosis in the cul-de-sac and a peritoneal window near the left uterosacral ligament. Biopsy of a cul-de-sac lesion showed endometriosis on histopathology. The patient was treated with a continuous low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive. Initially, the treatment helped relieve her pain symptoms. Over the next year, while on that treatment, her pain gradually increased in severity until it was disabling. At an office visit, the primary clinician renewed the estrogen-progestin contraceptive for another year, even though it was not relieving the patient’s pain. The patient sought a second opinion.

We are the experts in the management of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

Women’s health clinicians are the specialists best trained to care for patients with severe pain caused by endometriosis. Low-dose continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed as a first-line hormonal treatment for pain caused by endometriosis. My observation is that estrogen-progestincontraceptives are often effective when initially prescribed, but with continued use over years, pain often recurs. Estrogen is known to stimulate endometriosis disease activity. Progestins at high doses suppress endometriosis disease activity. However, endometriosis implants often manifest decreased responsiveness to progestins, permitting the estrogen in the combination contraceptive to exert its disease-stimulating effect.1,2 I frequently see women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, who initially had a significant decrease in pain with continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment but who develop increasing pain with continued use of the medication. In this clinical situation, it is useful to consider stopping the estrogen-progestin therapy and to prescribe a hormone with a different mechanism of action (TABLE).

Progestin-only medications

Progestin-only medications are often effective in the treatment of pain caused by endometriosis. High-dose progestin-only medications suppress pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thereby suppressing ovarian synthesis of estrogen, resulting in low circulating levels of estrogen. This removes the estrogen stimulus that exacerbates endometriosis disease activity. High-dose progestins also directly suppress cellular activity in endometriosis implants. High-dose progestins often overcome the relative resistance of endometriosis lesions to progestin suppression of disease activity. Hence, high-dose progestin-only medications have two mechanisms of action: suppression of estrogen synthesis through pituitary suppression of LH and FSH, and direct inhibition of cellular activity in the endometriosis lesions. High-dose progestin-only treatments include:

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily

- oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 20 to 40 mg daily

- subcutaneous, or depot MPA

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD).

In my practice, I frequently use oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In one randomized trial, 90 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were randomly assigned to treatment with norethindrone acetate 2.5 mg daily or an estrogen-progestin contraceptive. After 12 months of treatment, satisfaction with treatment was reported by 73% and 62% of the women in the norethindrone acetate and estrogen-progestin groups, respectively.3 The most common adverse effects reported by women taking norethindrone acetate were weight gain (27%) and decreased libido (9%).

Oral MPA at doses of 30 mg to 100 mg daily has been reported to be effective for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. MPA treatment can induce atrophy and pseudodecidualization in endometrium and endometriosis implants. In my practice I typically prescribe doses in the range of 20 mg to 40 mg daily. With oral MPA treatment, continued uterine bleeding may occur in up to 30% of women, somewhat limiting its efficacy.4–7

Subcutaneous and depot MPA have been reported to be effective in the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.4,8 In some resource-limited countries, depot MPA may be the most available progestin for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

The LNG-IUD, inserted after surgery for endometriosis, has been reported to result in decreased pelvic pain in studies with a modest number of participants.9–11

GnRH analogue medications

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, including both GnRH agonists (nafarelin, leuprolide, and goserelin) and GnRH antagonists (elagolix) reduce pelvic pain caused by endometriosis by suppressing pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, thereby reducing ovarian synthesis of estradiol. In the absence of estradiol stimulation, cellular activity in endometriosis lesions decreases and pain symptoms improve. In my practice, I frequently use either nafarelin12 or leuprolide acetate depot plus norethindrone add-back.13 I generally avoid the use of leuprolide depot monotherapy because in many women it causes severe vasomotor symptoms.

At standard doses, nafarelin therapy generally results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, a “sweet spot” associated with modest vasomotor symptoms and reduced cellular activity in endometriosis implants.12,14 In many women who become amenorrheic on nafarelin two sprays daily, the dose can be reduced with maintenance of pain control and ovarian suppression.15 Leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 5 to 10 pg/mL, causing severe vasomotor symptoms and reduction in cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. To reduce the adverse effects of leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy, I generally initiate concomitant add-back therapy with norethindrone acetate.13 A little recognized pharmacokinetic observation is that a very small amount of norethindrone acetate, generally less than 1%, is metabolized to ethinyl estradiol.16

The oral GnRH antagonist, elagolix, 150 mg daily for up to 24 months or 200 mg twice daily for 6 months, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2018. It is now available in pharmacies. Elagolix treatment results in significant reduction in pain caused by endometriosis, but only moderately bothersome vasomotor symptoms.17,18 Elagolix likely will become a widely used medication because of the simplicity of oral administration, efficacy against endometriosis, and acceptable adverse-effect profile. A major disadvantage of the GnRH analogue-class of medications is that they are more expensive than the progestin medications mentioned above. Among the GnRH analogue class of medications, elagolix and goserelin are the least expensive.

Androgens

Estrogen stimulates cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Androgen and high-dose progestins inhibit cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Danazol, an attenuated androgen and a progestin is effectivein treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.19,20 However, many women decline to use danazol because it is often associated with weight gain. As an androgen, danazol can permanently change a woman’s voice pitch and should not be used by professional singers or speech therapists.

Aromatase Inhibitors

Estrogen is a critically important stimulus of cell activity in endometriosis lesions. Aromatase inhibitors, which block the synthesis of estrogen, have been explored in the treatment of endometriosis that has proven to be resistant to other therapies. Although the combination of an aromatase inhibitor plus a high-dose progestin or GnRH analogue may be effective, more data are needed before widely using the aromatase inhibitors in clinical practice.21

Don’t get stuck in a rut

When treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, if the patient’s hormone regimen is not working, prescribe a medication from another class of hormones. In the case presented above, a woman with pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis reported inadequate control of her pain symptoms with a continuous estrogen-progestin medication. Her physician prescribed another year of the same estrogen-progestin medication. Instead of renewing the medication, the physician could have offered the patient a hormone medication from another drug class: 1) progestin only, 2) GnRH analogue, or 3) danazol. By using every available hormonal agent, physicians will improve the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Millions of women in our country have pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. They are counting on us, women’s health specialists, to effectively treat their disease.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Patel BG, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor RN. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):623–632.

- Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):36–43.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

- Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD002122.

- Moghissi KS, Boyce CR. Management of endometriosis with oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47(3):265–267.

- Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Rönnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1(1):13–23.

- Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 pt 1):323–327.

- Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leu-prolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314–325.

- Abou-Setta AM, Houston B, Al-Inany HG, Farquhar C. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD005072.

- Tanmahasamut P, Rattanachaiyanont M, Angsuwathana S, Techatraisak K, Indhavivadhana S, Leerasiri P. Postoperative levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for pelvic endometriosis-pain: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):519–526.

- Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273–279.

- Henzl MR, Corson SL, Moghissi K, Buttram VC, Berqvist C, Jacobsen J. Administration of nasal nafarelin as compared with oral danazol for endo-metriosis. A multicenter double-blind comparative clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(8):485–489.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 91(1):16–24.

- Barbieri RL. Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(2):740–745.

- Hull ME, Barbieri RL. Nafarelin in the treatment of endometriosis. Dose management. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;37(4):263–264.

- Barbieri RL, Petro Z, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. Aromatization of norethindrone to ethinyl estradiol by human placental microsomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(2):299–303.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28–40.

- Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):147–160.

- Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000068.

- Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Danazol: endocrine pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(4):453–463.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

- Patel BG, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor RN. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):623–632.

- Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):36–43.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

- Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD002122.

- Moghissi KS, Boyce CR. Management of endometriosis with oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47(3):265–267.

- Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Rönnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1(1):13–23.

- Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 pt 1):323–327.

- Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leu-prolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314–325.

- Abou-Setta AM, Houston B, Al-Inany HG, Farquhar C. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD005072.

- Tanmahasamut P, Rattanachaiyanont M, Angsuwathana S, Techatraisak K, Indhavivadhana S, Leerasiri P. Postoperative levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for pelvic endometriosis-pain: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):519–526.

- Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273–279.

- Henzl MR, Corson SL, Moghissi K, Buttram VC, Berqvist C, Jacobsen J. Administration of nasal nafarelin as compared with oral danazol for endo-metriosis. A multicenter double-blind comparative clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(8):485–489.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 91(1):16–24.

- Barbieri RL. Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(2):740–745.

- Hull ME, Barbieri RL. Nafarelin in the treatment of endometriosis. Dose management. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;37(4):263–264.

- Barbieri RL, Petro Z, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. Aromatization of norethindrone to ethinyl estradiol by human placental microsomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(2):299–303.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28–40.

- Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):147–160.

- Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000068.

- Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Danazol: endocrine pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(4):453–463.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

What works best for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: vaginal estrogen, vaginal laser, or combined laser and estrogen therapy?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

GSM encompasses a constellation of symptoms involving the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, and it can affect quality of life in more than half of women by 3 years past menopause.1,2 Local estrogen creams, tablets, and rings are considered the gold standard treatment for GSM.3 The rising cost of many of these pharmacologic treatments has created headlines and concerns over price gouging for drugs used to treat female sexual dysfunction.4 Recent alternatives to local estrogens include vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories, oral ospemifene, and vaginal laser therapy.

Laser treatment (with fractionated CO2, erbium, and hybrid lasers) activates heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors to stimulateneocollagenesis and neovascularization within the vaginal epithelium,but it is expensive and not covered by insurance because it is considered a cosmetic procedure.5Most evidence on laser therapy for GSM comes from prospective case series with small numbers and short-term follow-up with no comparison arms.6,7 A recent trial by Cruz and colleagues, however, is notable because it is one of the first published studies that compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen alone and with a combination laser plus estrogen arm. We need level 1 comparative data from studies such as this to help us counsel the millions of US women with GSM.

Details of the study

In this single-site randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Brazil, postmenopausal women were assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups (15 per group):

- CO2 laser (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide 2 system; DEKA Laser; Florence, Italy): 2 treatments total, 1 month apart, plus placebo cream (laser arm)

- estriol cream (1 mg estriol 3 times per week for 20 weeks) plus sham laser (estriol arm)

- CO2 laser plus estriol cream 3 times per week (laser plus estriol combination arm).

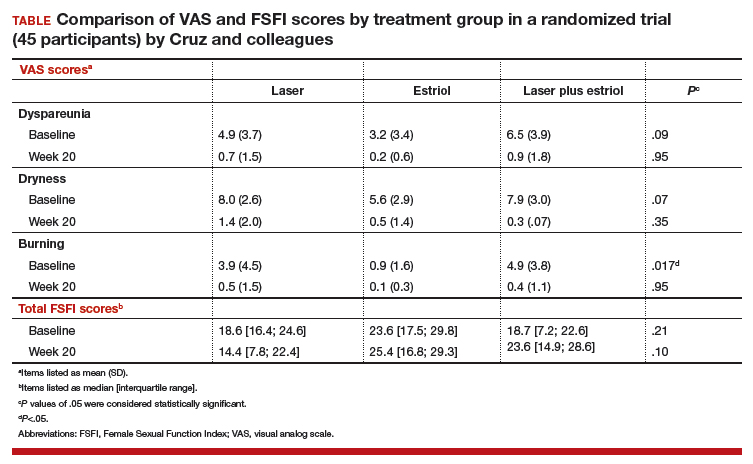

The primary outcome included a change in visual analog scale (VAS) score for symptoms related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), including dyspareunia, dryness, and burning (0–10 scale with 0 = no symptoms and 10 = most severe symptoms), and change in the objective Vaginal Health Index (VHI). Assessments were made at baseline and at 8 and 20 weeks. Participants were included if they were menopausal for at least 2 years and had at least 1 moderately bothersome VVA symptom (based on a VAS score of 4 or greater).

Secondary outcomes included the objective FSFI questionnaire evaluating desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI scores can range from 2 (severe dysfunction) to 36 (no dysfunction). A total FSFI score less than 26 was deemed equivalent to dysfunction. Cytologic smear evaluation using a vaginal maturation index was included in all 3 treatment arms. Sample size calculation of 45 patients (15 per arm) for this trial was based on a 3-point difference in the VHI.

The baseline characteristics for participants in each treatment arm were similar, except that participants in the vaginal estriol group were less symptomatic at baseline. This group had less burning at baseline based on the FSFI and less dyspareunia based on the VAS.

On July 30, 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning against the use of energy-based devices for vaginal "rejuvenation"1 and sent warning letters to 7 companies--Alma Lasers; BTL Aesthetics; BTL Industries, Inc; Cynosure, Inc; InMode MD; Sciton, Inc; and Thermigen, Inc.2 The concern relates to marketing claims made on many of these companies' websites on the use of radiofrequency and laser technology for such specific conditions as vaginal laxity, vaginal dryness, urinary incontinence, and sexual function and response. These devices are neither cleared nor approved by the FDA for these specific indications; they are rather approved for general gynecologic conditions, such as the treatment of genital warts and precancerous conditions.

The FDA sent the safety warning related to energy-based vaginal therapies to patients and providers and have encouraged them to submit any adverse events to MedWatch, the FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting system.1 The "It has come to our attention letters" issued by the FDA to the above manufacturers request additional information and FDA clearance or approval numbers for claims made on their websites--specifically, referenced benefits of energy-based devices for vaginal, vulvar, and sexual health.2 This information is requested from manufacturers in writing by August 30, 2018 (30 days).

References

- FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- Letters to industry. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm111104.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

Laser treatment improved dryness, burning, and dyspareunia but caused more pain

All 3 treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement in vaginal dryness at 20 weeks, but only the laser-alone arm and the laser plus estriol arms showed improvement in dyspareunia and burning. The total FSFI scores improved significantly only in the laser plus estriol arm (TABLE). No difference in the vaginal maturation index was noted between groups; however, improved numbers of parabasal cells were found in participants in the laser treatment arms.

While participants in the laser treatment arms (alone and in combination with estriol) showed significant improvement in the VAS domains of dyspareunia and burning compared with those treated with estriol alone, there was a contradictory finding of more pain in both laser arms at 20 weeks compared with the estriol-alone group, based on the FSFI. The FSFI is a validated, objective quality-of-life questionnaire, and the finding of more pain with laser treatment is a concern.

Exercise caution when interpreting these study findings. While this preliminary study showed that fractionated CO2 laser treatment had favorable outcomes for dyspareunia, dryness, and burning, the propensity for increased vaginal pain with this treatment is a concern. This study was not adequately powered to analyze multiple comparisons in postmenopausal women with GSM symptoms. There were significant baseline differences, with less bothersome burning and sexual complaints based on the FSFI and VAS, in the vaginal estriol arm. The finding of more pain in the laser treatment arms at 20 weeks compared with that in the vaginal estriol arm is of concern and warrants further investigation.

-- Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study is one of the first of its kind to compare laser therapy alone and in combination with local estriol to vaginal estriol alone for the treatment of GSM. The trial’s strength is in its design as a double-blind, placebo-controlled block randomized trial, which adds to the prospective cohort trials that generally show favorable outcomes for fractionated laser for the treatment of GSM.

The study’s weaknesses include its small sample size, single trial site, and short-term follow-up. Findings from this trial should be considered preliminary and not generalizable. Other weaknesses are the 3 of 45 participants lost to follow-up and the significant baseline differences among the women, with lower bothersome baseline VAS scores in the estriol arm.

Furthermore, this study was not powered for multiple comparisons, and conclusions favoring laser therapy cannot be overinflated. Lasers such as CO2 target the chromophore water, and indiscriminate use in severely dry vaginal epithelium may cause more pain or scarring. Longer-term follow-up is needed.

More research also is needed to develop guidelines related to pre-laser treatment to achieve optimal vaginal pH and ideal vaginal maturation, including, for example, vaginal priming with estrogen, DHEA, or other moisturizers.

This study also suggests the use of vaginal laser therapy as a drug delivery mechanism for combination therapy. Many vaginal estrogen treatments are expensive (despite prescription drug coverage), and laser treatments are very expensive (and not covered by insurance), so research to optimize outcomes and minimize patient expense is needed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Thomas K. Prices keep rising for drugs treating painful sex in women. New York Times. June 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/03/health/vagina-womens-health-drug-prices.html. Accessed July 15, 2018.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of meno-pause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137–159.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(5):512–518.

- Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–814.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

GSM encompasses a constellation of symptoms involving the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, and it can affect quality of life in more than half of women by 3 years past menopause.1,2 Local estrogen creams, tablets, and rings are considered the gold standard treatment for GSM.3 The rising cost of many of these pharmacologic treatments has created headlines and concerns over price gouging for drugs used to treat female sexual dysfunction.4 Recent alternatives to local estrogens include vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories, oral ospemifene, and vaginal laser therapy.

Laser treatment (with fractionated CO2, erbium, and hybrid lasers) activates heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors to stimulateneocollagenesis and neovascularization within the vaginal epithelium,but it is expensive and not covered by insurance because it is considered a cosmetic procedure.5Most evidence on laser therapy for GSM comes from prospective case series with small numbers and short-term follow-up with no comparison arms.6,7 A recent trial by Cruz and colleagues, however, is notable because it is one of the first published studies that compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen alone and with a combination laser plus estrogen arm. We need level 1 comparative data from studies such as this to help us counsel the millions of US women with GSM.

Details of the study

In this single-site randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Brazil, postmenopausal women were assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups (15 per group):

- CO2 laser (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide 2 system; DEKA Laser; Florence, Italy): 2 treatments total, 1 month apart, plus placebo cream (laser arm)

- estriol cream (1 mg estriol 3 times per week for 20 weeks) plus sham laser (estriol arm)

- CO2 laser plus estriol cream 3 times per week (laser plus estriol combination arm).

The primary outcome included a change in visual analog scale (VAS) score for symptoms related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), including dyspareunia, dryness, and burning (0–10 scale with 0 = no symptoms and 10 = most severe symptoms), and change in the objective Vaginal Health Index (VHI). Assessments were made at baseline and at 8 and 20 weeks. Participants were included if they were menopausal for at least 2 years and had at least 1 moderately bothersome VVA symptom (based on a VAS score of 4 or greater).

Secondary outcomes included the objective FSFI questionnaire evaluating desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI scores can range from 2 (severe dysfunction) to 36 (no dysfunction). A total FSFI score less than 26 was deemed equivalent to dysfunction. Cytologic smear evaluation using a vaginal maturation index was included in all 3 treatment arms. Sample size calculation of 45 patients (15 per arm) for this trial was based on a 3-point difference in the VHI.

The baseline characteristics for participants in each treatment arm were similar, except that participants in the vaginal estriol group were less symptomatic at baseline. This group had less burning at baseline based on the FSFI and less dyspareunia based on the VAS.

On July 30, 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning against the use of energy-based devices for vaginal "rejuvenation"1 and sent warning letters to 7 companies--Alma Lasers; BTL Aesthetics; BTL Industries, Inc; Cynosure, Inc; InMode MD; Sciton, Inc; and Thermigen, Inc.2 The concern relates to marketing claims made on many of these companies' websites on the use of radiofrequency and laser technology for such specific conditions as vaginal laxity, vaginal dryness, urinary incontinence, and sexual function and response. These devices are neither cleared nor approved by the FDA for these specific indications; they are rather approved for general gynecologic conditions, such as the treatment of genital warts and precancerous conditions.

The FDA sent the safety warning related to energy-based vaginal therapies to patients and providers and have encouraged them to submit any adverse events to MedWatch, the FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting system.1 The "It has come to our attention letters" issued by the FDA to the above manufacturers request additional information and FDA clearance or approval numbers for claims made on their websites--specifically, referenced benefits of energy-based devices for vaginal, vulvar, and sexual health.2 This information is requested from manufacturers in writing by August 30, 2018 (30 days).

References

- FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- Letters to industry. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm111104.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

Laser treatment improved dryness, burning, and dyspareunia but caused more pain

All 3 treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement in vaginal dryness at 20 weeks, but only the laser-alone arm and the laser plus estriol arms showed improvement in dyspareunia and burning. The total FSFI scores improved significantly only in the laser plus estriol arm (TABLE). No difference in the vaginal maturation index was noted between groups; however, improved numbers of parabasal cells were found in participants in the laser treatment arms.

While participants in the laser treatment arms (alone and in combination with estriol) showed significant improvement in the VAS domains of dyspareunia and burning compared with those treated with estriol alone, there was a contradictory finding of more pain in both laser arms at 20 weeks compared with the estriol-alone group, based on the FSFI. The FSFI is a validated, objective quality-of-life questionnaire, and the finding of more pain with laser treatment is a concern.

Exercise caution when interpreting these study findings. While this preliminary study showed that fractionated CO2 laser treatment had favorable outcomes for dyspareunia, dryness, and burning, the propensity for increased vaginal pain with this treatment is a concern. This study was not adequately powered to analyze multiple comparisons in postmenopausal women with GSM symptoms. There were significant baseline differences, with less bothersome burning and sexual complaints based on the FSFI and VAS, in the vaginal estriol arm. The finding of more pain in the laser treatment arms at 20 weeks compared with that in the vaginal estriol arm is of concern and warrants further investigation.

-- Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study is one of the first of its kind to compare laser therapy alone and in combination with local estriol to vaginal estriol alone for the treatment of GSM. The trial’s strength is in its design as a double-blind, placebo-controlled block randomized trial, which adds to the prospective cohort trials that generally show favorable outcomes for fractionated laser for the treatment of GSM.

The study’s weaknesses include its small sample size, single trial site, and short-term follow-up. Findings from this trial should be considered preliminary and not generalizable. Other weaknesses are the 3 of 45 participants lost to follow-up and the significant baseline differences among the women, with lower bothersome baseline VAS scores in the estriol arm.

Furthermore, this study was not powered for multiple comparisons, and conclusions favoring laser therapy cannot be overinflated. Lasers such as CO2 target the chromophore water, and indiscriminate use in severely dry vaginal epithelium may cause more pain or scarring. Longer-term follow-up is needed.

More research also is needed to develop guidelines related to pre-laser treatment to achieve optimal vaginal pH and ideal vaginal maturation, including, for example, vaginal priming with estrogen, DHEA, or other moisturizers.

This study also suggests the use of vaginal laser therapy as a drug delivery mechanism for combination therapy. Many vaginal estrogen treatments are expensive (despite prescription drug coverage), and laser treatments are very expensive (and not covered by insurance), so research to optimize outcomes and minimize patient expense is needed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

GSM encompasses a constellation of symptoms involving the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, and it can affect quality of life in more than half of women by 3 years past menopause.1,2 Local estrogen creams, tablets, and rings are considered the gold standard treatment for GSM.3 The rising cost of many of these pharmacologic treatments has created headlines and concerns over price gouging for drugs used to treat female sexual dysfunction.4 Recent alternatives to local estrogens include vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories, oral ospemifene, and vaginal laser therapy.

Laser treatment (with fractionated CO2, erbium, and hybrid lasers) activates heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors to stimulateneocollagenesis and neovascularization within the vaginal epithelium,but it is expensive and not covered by insurance because it is considered a cosmetic procedure.5Most evidence on laser therapy for GSM comes from prospective case series with small numbers and short-term follow-up with no comparison arms.6,7 A recent trial by Cruz and colleagues, however, is notable because it is one of the first published studies that compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen alone and with a combination laser plus estrogen arm. We need level 1 comparative data from studies such as this to help us counsel the millions of US women with GSM.

Details of the study

In this single-site randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Brazil, postmenopausal women were assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups (15 per group):

- CO2 laser (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide 2 system; DEKA Laser; Florence, Italy): 2 treatments total, 1 month apart, plus placebo cream (laser arm)

- estriol cream (1 mg estriol 3 times per week for 20 weeks) plus sham laser (estriol arm)

- CO2 laser plus estriol cream 3 times per week (laser plus estriol combination arm).

The primary outcome included a change in visual analog scale (VAS) score for symptoms related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), including dyspareunia, dryness, and burning (0–10 scale with 0 = no symptoms and 10 = most severe symptoms), and change in the objective Vaginal Health Index (VHI). Assessments were made at baseline and at 8 and 20 weeks. Participants were included if they were menopausal for at least 2 years and had at least 1 moderately bothersome VVA symptom (based on a VAS score of 4 or greater).

Secondary outcomes included the objective FSFI questionnaire evaluating desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI scores can range from 2 (severe dysfunction) to 36 (no dysfunction). A total FSFI score less than 26 was deemed equivalent to dysfunction. Cytologic smear evaluation using a vaginal maturation index was included in all 3 treatment arms. Sample size calculation of 45 patients (15 per arm) for this trial was based on a 3-point difference in the VHI.

The baseline characteristics for participants in each treatment arm were similar, except that participants in the vaginal estriol group were less symptomatic at baseline. This group had less burning at baseline based on the FSFI and less dyspareunia based on the VAS.

On July 30, 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning against the use of energy-based devices for vaginal "rejuvenation"1 and sent warning letters to 7 companies--Alma Lasers; BTL Aesthetics; BTL Industries, Inc; Cynosure, Inc; InMode MD; Sciton, Inc; and Thermigen, Inc.2 The concern relates to marketing claims made on many of these companies' websites on the use of radiofrequency and laser technology for such specific conditions as vaginal laxity, vaginal dryness, urinary incontinence, and sexual function and response. These devices are neither cleared nor approved by the FDA for these specific indications; they are rather approved for general gynecologic conditions, such as the treatment of genital warts and precancerous conditions.

The FDA sent the safety warning related to energy-based vaginal therapies to patients and providers and have encouraged them to submit any adverse events to MedWatch, the FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting system.1 The "It has come to our attention letters" issued by the FDA to the above manufacturers request additional information and FDA clearance or approval numbers for claims made on their websites--specifically, referenced benefits of energy-based devices for vaginal, vulvar, and sexual health.2 This information is requested from manufacturers in writing by August 30, 2018 (30 days).

References

- FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- Letters to industry. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm111104.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

Laser treatment improved dryness, burning, and dyspareunia but caused more pain

All 3 treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement in vaginal dryness at 20 weeks, but only the laser-alone arm and the laser plus estriol arms showed improvement in dyspareunia and burning. The total FSFI scores improved significantly only in the laser plus estriol arm (TABLE). No difference in the vaginal maturation index was noted between groups; however, improved numbers of parabasal cells were found in participants in the laser treatment arms.

While participants in the laser treatment arms (alone and in combination with estriol) showed significant improvement in the VAS domains of dyspareunia and burning compared with those treated with estriol alone, there was a contradictory finding of more pain in both laser arms at 20 weeks compared with the estriol-alone group, based on the FSFI. The FSFI is a validated, objective quality-of-life questionnaire, and the finding of more pain with laser treatment is a concern.

Exercise caution when interpreting these study findings. While this preliminary study showed that fractionated CO2 laser treatment had favorable outcomes for dyspareunia, dryness, and burning, the propensity for increased vaginal pain with this treatment is a concern. This study was not adequately powered to analyze multiple comparisons in postmenopausal women with GSM symptoms. There were significant baseline differences, with less bothersome burning and sexual complaints based on the FSFI and VAS, in the vaginal estriol arm. The finding of more pain in the laser treatment arms at 20 weeks compared with that in the vaginal estriol arm is of concern and warrants further investigation.

-- Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study is one of the first of its kind to compare laser therapy alone and in combination with local estriol to vaginal estriol alone for the treatment of GSM. The trial’s strength is in its design as a double-blind, placebo-controlled block randomized trial, which adds to the prospective cohort trials that generally show favorable outcomes for fractionated laser for the treatment of GSM.

The study’s weaknesses include its small sample size, single trial site, and short-term follow-up. Findings from this trial should be considered preliminary and not generalizable. Other weaknesses are the 3 of 45 participants lost to follow-up and the significant baseline differences among the women, with lower bothersome baseline VAS scores in the estriol arm.

Furthermore, this study was not powered for multiple comparisons, and conclusions favoring laser therapy cannot be overinflated. Lasers such as CO2 target the chromophore water, and indiscriminate use in severely dry vaginal epithelium may cause more pain or scarring. Longer-term follow-up is needed.

More research also is needed to develop guidelines related to pre-laser treatment to achieve optimal vaginal pH and ideal vaginal maturation, including, for example, vaginal priming with estrogen, DHEA, or other moisturizers.

This study also suggests the use of vaginal laser therapy as a drug delivery mechanism for combination therapy. Many vaginal estrogen treatments are expensive (despite prescription drug coverage), and laser treatments are very expensive (and not covered by insurance), so research to optimize outcomes and minimize patient expense is needed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Thomas K. Prices keep rising for drugs treating painful sex in women. New York Times. June 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/03/health/vagina-womens-health-drug-prices.html. Accessed July 15, 2018.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of meno-pause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137–159.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(5):512–518.

- Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–814.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Thomas K. Prices keep rising for drugs treating painful sex in women. New York Times. June 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/03/health/vagina-womens-health-drug-prices.html. Accessed July 15, 2018.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of meno-pause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137–159.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(5):512–518.

- Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–814.

Title X and proposed changes: Take action now

The facts

Title X, a bill originally passed in 1970 under President Nixon, is the only federal grant program dedicated to providing family planning services as well as other preventive health care to primarily low-income patients. It is estimated that 70% of patients using Title X services are below the federal poverty level and more than 60% are uninsured or underinsured.1

In 2015 alone, Title X clinics served 3.8 million women, preventing 822,300 unintended pregnancies and 277,800 abortions.2 These clinics provide comprehensive family planning services including information, counseling, and referrals for abortion services. Title X clinics do not use the funding to provide abortion care, and no federal funding from Title X has ever been used to pay for abortions.

Proposed rule changes

The Trump Administration has proposed several new rules for Title X grant recipients.

Here are the main changes3:

- There must be a “financial and physical” separation between a clinic that is a Title X grant recipient and a facility where “abortion is a method of family planning.” This would prevent health centers that receive Title X funding from providing abortions at the same facility. This rule would predominantly affect health centers like Planned Parenthood. Although these clinics already have a financial separation from abortion care, there would not be a physical one in most situations and these clinics would lose Title X funding or be forced to stop providing abortion services.

- Providers who work at a clinic that receives Title X funding but provides abortions at a completely different facility may be ineligible for ongoing Title X grant money. In the new changes, “funds may not be used…to support the separate abortion business of Title X grant subrecipient.” The changes also propose to “protect Title X providers” from choosing between the health of their patients and their consciences. It plans to do this by removing the requirement to provide abortion counseling and referral and allows “non-directive” counseling.

- There would also be a requirement to encourage more parental involvement in minors’ decision making. While clinics already discuss parental involvement, the change would seek to increase the encouragement to young patients to involve parents. Most young patients do involve a parent or guardian in their care; however, many Title X clinics serve young patients who seek care confidentially. Patients seek confidential care due to a multitude of reasons, including history of abuse, lack of trust, and intimate partner violence.

- “A Title X project may not perform, promote, refer for, or support abortion as a method of family planning.” Although the rule does not prevent providers from discussing abortions, clinicians could offer little guidance if a patient opts for an abortion. Providers can give a list of “qualified, comprehensive health service providers” but may not disclose which, if any, of the providers perform abortions.

Take action

Title X provides important health care services to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured patients. These proposals put access to comprehensive health care for vulnerable populations at risk. Medical organizations including the American Medical Association and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have made statements against the proposed changes to Title X. As ObGyns, we need to ensure our patients are fully informed and have access to all family planning and preventive health services.

Call or email your local representative and tell them you oppose the changes to Title X. Find your representatives here.

Follow ACOG’s Action Center on protecting Title X, which includes a flyer for your waiting room.

Send a message to the Health and Human Services Secretary. Submit a formal comment through July 31, 2018, on the Federal Registrar website expressing your thoughts with these proposed changes.

- Title X: Helping ensure access to high-quality care. National family planning website. https://www.nationalfamilyplanning.org/document.doc?id=514. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- Publicly Funded Contraceptive Services at U.S. Clinics, 2015. Guttmacher website. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2018/06/domestic-gag-rule-and-more-administrations-proposed-changes-title-x. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- Compliance with statutory program integrity requirements. Federal register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/06/01/2018-11673/compliance-with-statutory-program-integrity-requirements. Accessed July 25, 2018.

The facts

Title X, a bill originally passed in 1970 under President Nixon, is the only federal grant program dedicated to providing family planning services as well as other preventive health care to primarily low-income patients. It is estimated that 70% of patients using Title X services are below the federal poverty level and more than 60% are uninsured or underinsured.1

In 2015 alone, Title X clinics served 3.8 million women, preventing 822,300 unintended pregnancies and 277,800 abortions.2 These clinics provide comprehensive family planning services including information, counseling, and referrals for abortion services. Title X clinics do not use the funding to provide abortion care, and no federal funding from Title X has ever been used to pay for abortions.

Proposed rule changes

The Trump Administration has proposed several new rules for Title X grant recipients.

Here are the main changes3:

- There must be a “financial and physical” separation between a clinic that is a Title X grant recipient and a facility where “abortion is a method of family planning.” This would prevent health centers that receive Title X funding from providing abortions at the same facility. This rule would predominantly affect health centers like Planned Parenthood. Although these clinics already have a financial separation from abortion care, there would not be a physical one in most situations and these clinics would lose Title X funding or be forced to stop providing abortion services.

- Providers who work at a clinic that receives Title X funding but provides abortions at a completely different facility may be ineligible for ongoing Title X grant money. In the new changes, “funds may not be used…to support the separate abortion business of Title X grant subrecipient.” The changes also propose to “protect Title X providers” from choosing between the health of their patients and their consciences. It plans to do this by removing the requirement to provide abortion counseling and referral and allows “non-directive” counseling.

- There would also be a requirement to encourage more parental involvement in minors’ decision making. While clinics already discuss parental involvement, the change would seek to increase the encouragement to young patients to involve parents. Most young patients do involve a parent or guardian in their care; however, many Title X clinics serve young patients who seek care confidentially. Patients seek confidential care due to a multitude of reasons, including history of abuse, lack of trust, and intimate partner violence.

- “A Title X project may not perform, promote, refer for, or support abortion as a method of family planning.” Although the rule does not prevent providers from discussing abortions, clinicians could offer little guidance if a patient opts for an abortion. Providers can give a list of “qualified, comprehensive health service providers” but may not disclose which, if any, of the providers perform abortions.

Take action

Title X provides important health care services to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured patients. These proposals put access to comprehensive health care for vulnerable populations at risk. Medical organizations including the American Medical Association and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have made statements against the proposed changes to Title X. As ObGyns, we need to ensure our patients are fully informed and have access to all family planning and preventive health services.

Call or email your local representative and tell them you oppose the changes to Title X. Find your representatives here.

Follow ACOG’s Action Center on protecting Title X, which includes a flyer for your waiting room.

Send a message to the Health and Human Services Secretary. Submit a formal comment through July 31, 2018, on the Federal Registrar website expressing your thoughts with these proposed changes.

The facts

Title X, a bill originally passed in 1970 under President Nixon, is the only federal grant program dedicated to providing family planning services as well as other preventive health care to primarily low-income patients. It is estimated that 70% of patients using Title X services are below the federal poverty level and more than 60% are uninsured or underinsured.1

In 2015 alone, Title X clinics served 3.8 million women, preventing 822,300 unintended pregnancies and 277,800 abortions.2 These clinics provide comprehensive family planning services including information, counseling, and referrals for abortion services. Title X clinics do not use the funding to provide abortion care, and no federal funding from Title X has ever been used to pay for abortions.

Proposed rule changes