User login

Does elimination of the bladder flap from cesarean delivery increase the risk of complications?

10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery

Baha M. Sibai, MD (March 2012)

Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure performed during pregnancy. In the United States, the rate of cesarean delivery approaches 30%. As this rate rises, it is likely to be accompanied by an increase in the rate of surgical complications, such as pelvic hematoma, infection, and bladder injury, and in the rate of long-term complications, such as adhesion formation.

Several studies have assessed technical aspects of cesarean delivery, but debate continues over whether a bladder flap is a necessary part of the standard procedure.

The bladder flap is developed by incising the peritoneal lining and dissecting the urinary bladder away from the lower uterine segment. Suggested benefits of the bladder flap are easy access to the lower uterine segment and avoidance of bladder injury—but these claims have not been confirmed in retrospective or randomized trials.1,2 On the contrary, some studies suggest that creation of a bladder flap prolongs the duration of surgery and may increase the risk of postoperative infection and adhesion formation, as well as bladder injury at the time of repeat cesarean.3

Details of the trial

This study by Tuuli and colleagues is a single-center, unblinded, randomized, controlled trial designed to explore the risks and benefits of creating a bladder flap versus those of omitting the flap at the time of cesarean delivery. Of the 258 women enrolled in the trial, 131 were allocated to creation of a bladder flap and 127 to omission of the flap.

The primary outcome was total operative time. Secondary outcomes were:

- bladder injury

- incision-to-delivery time

- incision-to-fascial closure time

- estimated blood loss

- postoperative pain

- hospital stay

- endometritis

- urinary tract infection.

Unlike an earlier trial that included only women undergoing primary cesarean, this study included both primary and repeat cesarean deliveries. Sample size for each group was calculated assuming a 5-minute difference in total operating time.

Of the 131 women allocated to the bladder-flap creation group, only 108 (82%) actually had a bladder flap; 23 (18%) did not. Conversely, among the 127 women allocated to the no-flap group, 14 (11%) had a bladder flap created, most commonly because of the presence of scar tissue (n = 9).

Neither group had any bladder injuries nor were there statistical differences in any of the other secondary outcomes studied.

The authors concluded that omission of the bladder flap from primary and repeat cesarean delivery does not increase intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Strengths and limitations

As I mentioned, the rationale for creating a bladder flap is to reduce the rate of bladder injury. Therefore, bladder injury should have been the primary outcome of this trial. However, because the expected rate of bladder injury during cesarean delivery is so low (0.14%–0.35%), a sample size of 40,000 women would have been needed to address this outcome.

Among women who do not have a bladder flap created during cesarean delivery, bladder injury may be more likely when the second stage of labor is prolonged (i.e., when the vertex is wedged low in the pelvis) and when the woman has a history of multiple cesarean deliveries. This study did not include information about the number of women meeting these criteria.

Another limitation of this trial: Adherence to the protocol was inadequate, as 18% of the women assigned to receive a bladder flap did not have one, and 11% of those assigned to receive no flap had a flap created. This failure to adhere to the protocol may explain the lack of significant differences in total delivery time between the two groups, as well as the clinically insignificant difference in the incision-to-delivery interval between groups.

The rationale for omitting a bladder flap is to shorten total operating and incision-to-delivery time and/or to reduce the rate of future adhesions. Regrettably, this trial provided no conclusive evidence regarding any of these benefits. We still need a randomized trial of adequate sample size to address some of the questions raised by this trial.

I agree with the authors of this trial that their findings—along with those of other studies—argue against routine creation of a bladder flap at cesarean delivery.

Consider clinical findings at the time of surgery when deciding whether or not to create a bladder flap. For example, a flap may ease delivery of the fetal head when pushing has been prolonged during the second stage of labor or when operative vaginal delivery has failed. A flap also may help the surgeon avoid injury to the bladder in cases involving accidental extension of the lower-segment incision.

Among women who have a history of cesarean delivery and in whom the bladder flap is attached high above the lower segment, the bladder should be dissected carefully away from the uterus to avoid injury during delivery.

Baha M. Sibai, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Gustapane S, et al. Surgical technique to avoid bladder flap formation during cesarean section. G Chir. 2011;32(11–12):498-403.

2. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, Joura EA. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;98(6):1089-1092.

3. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Guido M, et al. Effect of avoiding bladder flap formation in cesarean section on repeat cesarean delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159(2):300-304.

10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery

Baha M. Sibai, MD (March 2012)

Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure performed during pregnancy. In the United States, the rate of cesarean delivery approaches 30%. As this rate rises, it is likely to be accompanied by an increase in the rate of surgical complications, such as pelvic hematoma, infection, and bladder injury, and in the rate of long-term complications, such as adhesion formation.

Several studies have assessed technical aspects of cesarean delivery, but debate continues over whether a bladder flap is a necessary part of the standard procedure.

The bladder flap is developed by incising the peritoneal lining and dissecting the urinary bladder away from the lower uterine segment. Suggested benefits of the bladder flap are easy access to the lower uterine segment and avoidance of bladder injury—but these claims have not been confirmed in retrospective or randomized trials.1,2 On the contrary, some studies suggest that creation of a bladder flap prolongs the duration of surgery and may increase the risk of postoperative infection and adhesion formation, as well as bladder injury at the time of repeat cesarean.3

Details of the trial

This study by Tuuli and colleagues is a single-center, unblinded, randomized, controlled trial designed to explore the risks and benefits of creating a bladder flap versus those of omitting the flap at the time of cesarean delivery. Of the 258 women enrolled in the trial, 131 were allocated to creation of a bladder flap and 127 to omission of the flap.

The primary outcome was total operative time. Secondary outcomes were:

- bladder injury

- incision-to-delivery time

- incision-to-fascial closure time

- estimated blood loss

- postoperative pain

- hospital stay

- endometritis

- urinary tract infection.

Unlike an earlier trial that included only women undergoing primary cesarean, this study included both primary and repeat cesarean deliveries. Sample size for each group was calculated assuming a 5-minute difference in total operating time.

Of the 131 women allocated to the bladder-flap creation group, only 108 (82%) actually had a bladder flap; 23 (18%) did not. Conversely, among the 127 women allocated to the no-flap group, 14 (11%) had a bladder flap created, most commonly because of the presence of scar tissue (n = 9).

Neither group had any bladder injuries nor were there statistical differences in any of the other secondary outcomes studied.

The authors concluded that omission of the bladder flap from primary and repeat cesarean delivery does not increase intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Strengths and limitations

As I mentioned, the rationale for creating a bladder flap is to reduce the rate of bladder injury. Therefore, bladder injury should have been the primary outcome of this trial. However, because the expected rate of bladder injury during cesarean delivery is so low (0.14%–0.35%), a sample size of 40,000 women would have been needed to address this outcome.

Among women who do not have a bladder flap created during cesarean delivery, bladder injury may be more likely when the second stage of labor is prolonged (i.e., when the vertex is wedged low in the pelvis) and when the woman has a history of multiple cesarean deliveries. This study did not include information about the number of women meeting these criteria.

Another limitation of this trial: Adherence to the protocol was inadequate, as 18% of the women assigned to receive a bladder flap did not have one, and 11% of those assigned to receive no flap had a flap created. This failure to adhere to the protocol may explain the lack of significant differences in total delivery time between the two groups, as well as the clinically insignificant difference in the incision-to-delivery interval between groups.

The rationale for omitting a bladder flap is to shorten total operating and incision-to-delivery time and/or to reduce the rate of future adhesions. Regrettably, this trial provided no conclusive evidence regarding any of these benefits. We still need a randomized trial of adequate sample size to address some of the questions raised by this trial.

I agree with the authors of this trial that their findings—along with those of other studies—argue against routine creation of a bladder flap at cesarean delivery.

Consider clinical findings at the time of surgery when deciding whether or not to create a bladder flap. For example, a flap may ease delivery of the fetal head when pushing has been prolonged during the second stage of labor or when operative vaginal delivery has failed. A flap also may help the surgeon avoid injury to the bladder in cases involving accidental extension of the lower-segment incision.

Among women who have a history of cesarean delivery and in whom the bladder flap is attached high above the lower segment, the bladder should be dissected carefully away from the uterus to avoid injury during delivery.

Baha M. Sibai, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery

Baha M. Sibai, MD (March 2012)

Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure performed during pregnancy. In the United States, the rate of cesarean delivery approaches 30%. As this rate rises, it is likely to be accompanied by an increase in the rate of surgical complications, such as pelvic hematoma, infection, and bladder injury, and in the rate of long-term complications, such as adhesion formation.

Several studies have assessed technical aspects of cesarean delivery, but debate continues over whether a bladder flap is a necessary part of the standard procedure.

The bladder flap is developed by incising the peritoneal lining and dissecting the urinary bladder away from the lower uterine segment. Suggested benefits of the bladder flap are easy access to the lower uterine segment and avoidance of bladder injury—but these claims have not been confirmed in retrospective or randomized trials.1,2 On the contrary, some studies suggest that creation of a bladder flap prolongs the duration of surgery and may increase the risk of postoperative infection and adhesion formation, as well as bladder injury at the time of repeat cesarean.3

Details of the trial

This study by Tuuli and colleagues is a single-center, unblinded, randomized, controlled trial designed to explore the risks and benefits of creating a bladder flap versus those of omitting the flap at the time of cesarean delivery. Of the 258 women enrolled in the trial, 131 were allocated to creation of a bladder flap and 127 to omission of the flap.

The primary outcome was total operative time. Secondary outcomes were:

- bladder injury

- incision-to-delivery time

- incision-to-fascial closure time

- estimated blood loss

- postoperative pain

- hospital stay

- endometritis

- urinary tract infection.

Unlike an earlier trial that included only women undergoing primary cesarean, this study included both primary and repeat cesarean deliveries. Sample size for each group was calculated assuming a 5-minute difference in total operating time.

Of the 131 women allocated to the bladder-flap creation group, only 108 (82%) actually had a bladder flap; 23 (18%) did not. Conversely, among the 127 women allocated to the no-flap group, 14 (11%) had a bladder flap created, most commonly because of the presence of scar tissue (n = 9).

Neither group had any bladder injuries nor were there statistical differences in any of the other secondary outcomes studied.

The authors concluded that omission of the bladder flap from primary and repeat cesarean delivery does not increase intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Strengths and limitations

As I mentioned, the rationale for creating a bladder flap is to reduce the rate of bladder injury. Therefore, bladder injury should have been the primary outcome of this trial. However, because the expected rate of bladder injury during cesarean delivery is so low (0.14%–0.35%), a sample size of 40,000 women would have been needed to address this outcome.

Among women who do not have a bladder flap created during cesarean delivery, bladder injury may be more likely when the second stage of labor is prolonged (i.e., when the vertex is wedged low in the pelvis) and when the woman has a history of multiple cesarean deliveries. This study did not include information about the number of women meeting these criteria.

Another limitation of this trial: Adherence to the protocol was inadequate, as 18% of the women assigned to receive a bladder flap did not have one, and 11% of those assigned to receive no flap had a flap created. This failure to adhere to the protocol may explain the lack of significant differences in total delivery time between the two groups, as well as the clinically insignificant difference in the incision-to-delivery interval between groups.

The rationale for omitting a bladder flap is to shorten total operating and incision-to-delivery time and/or to reduce the rate of future adhesions. Regrettably, this trial provided no conclusive evidence regarding any of these benefits. We still need a randomized trial of adequate sample size to address some of the questions raised by this trial.

I agree with the authors of this trial that their findings—along with those of other studies—argue against routine creation of a bladder flap at cesarean delivery.

Consider clinical findings at the time of surgery when deciding whether or not to create a bladder flap. For example, a flap may ease delivery of the fetal head when pushing has been prolonged during the second stage of labor or when operative vaginal delivery has failed. A flap also may help the surgeon avoid injury to the bladder in cases involving accidental extension of the lower-segment incision.

Among women who have a history of cesarean delivery and in whom the bladder flap is attached high above the lower segment, the bladder should be dissected carefully away from the uterus to avoid injury during delivery.

Baha M. Sibai, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Gustapane S, et al. Surgical technique to avoid bladder flap formation during cesarean section. G Chir. 2011;32(11–12):498-403.

2. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, Joura EA. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;98(6):1089-1092.

3. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Guido M, et al. Effect of avoiding bladder flap formation in cesarean section on repeat cesarean delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159(2):300-304.

1. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Gustapane S, et al. Surgical technique to avoid bladder flap formation during cesarean section. G Chir. 2011;32(11–12):498-403.

2. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, Joura EA. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;98(6):1089-1092.

3. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Guido M, et al. Effect of avoiding bladder flap formation in cesarean section on repeat cesarean delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159(2):300-304.

In women who have stress incontinence and intrinsic sphincter deficiency, which midurethral sling produces the best long-term results?

- Which sling for which SUI patient?

Mark D. Walters, MD, and Anne M. Weber, MD (Surgical Techniques, May 2012)

![]()

These videos were selected by Dr. Walters and presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS)

When ISD is present, the urethra cannot coaptate and loses its ability to maintain a watertight seal. Women who have this condition often are severely incontinent, leaking urine at low volumes and pressures and with minimal exertion.

In this randomized trial, Schierlitz and colleagues hypothesized that TOT would produce higher objective and subjective failure rates than the TVT. This was confirmed by 6-month data published in 2008.

Details of the trial

Women who had SUI were included in the trial if they had ISD based on urodynamic findings (i.e., maximum urethral closure pressure ≤20 cm H2O or Valsalva leak-point pressure ≤60 cm H2O, or both) and were randomly assigned to TVT or TOT. The primary endpoint was symptomatic SUI (confirmed by repeat urodynamic testing) that required a second procedure upon patient request.

Participants were followed for 3 years. If a patient reported symptoms, urodynamic testing was repeated. In addition, the patient was offered another surgery, usually involving placement of a TVT sling.

Schierlitz and colleagues concluded that, if TVT were used in all patients, repeat surgery would be avoided in one in every six patients. The risk of repeat surgery was 15 times greater for TOT, compared with the TVT sling. The median time to failure was 15.6 months for the TOT sling, compared with 43.7 months for the TVT.

Of the 16 patients who underwent repeat surgery, 56% were cured, 25% reported minimal leakage, and 19% remained unchanged.

Quality-of-life scores were similar between groups at the 6-month follow-up.

Why did the TVT outperform the TOT in this population?

Investigators theorized that there is a difference in sling axis, with the TVT placed at a more acute angle than the TOT sling. In addition, the location of the TOT sling is more distal than that of the TVT, based on ultrasonographic imaging. As a result, more effective urethral kinking and support are likely with the TVT sling, improving continence rates.

Strengths and limitations of the trial

The randomization of participants and long-term follow-up bolster the trial’s credibility.

Weaknesses include unblinded participation and postoperative surgical assessment.

Although the sample size was underpowered, there was a significant difference in the primary outcome between the two groups.

Long-term success is more likely with placement of a TVT sling in women who have SUI with ISD.

Urodynamic assessment still serves an important role in the diagnosis of ISD, and aids in preoperative planning.

LADIN A. YURTERI-KAPLAN, MD, AND AMY J. PARK, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Which sling for which SUI patient?

Mark D. Walters, MD, and Anne M. Weber, MD (Surgical Techniques, May 2012)

![]()

These videos were selected by Dr. Walters and presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS)

When ISD is present, the urethra cannot coaptate and loses its ability to maintain a watertight seal. Women who have this condition often are severely incontinent, leaking urine at low volumes and pressures and with minimal exertion.

In this randomized trial, Schierlitz and colleagues hypothesized that TOT would produce higher objective and subjective failure rates than the TVT. This was confirmed by 6-month data published in 2008.

Details of the trial

Women who had SUI were included in the trial if they had ISD based on urodynamic findings (i.e., maximum urethral closure pressure ≤20 cm H2O or Valsalva leak-point pressure ≤60 cm H2O, or both) and were randomly assigned to TVT or TOT. The primary endpoint was symptomatic SUI (confirmed by repeat urodynamic testing) that required a second procedure upon patient request.

Participants were followed for 3 years. If a patient reported symptoms, urodynamic testing was repeated. In addition, the patient was offered another surgery, usually involving placement of a TVT sling.

Schierlitz and colleagues concluded that, if TVT were used in all patients, repeat surgery would be avoided in one in every six patients. The risk of repeat surgery was 15 times greater for TOT, compared with the TVT sling. The median time to failure was 15.6 months for the TOT sling, compared with 43.7 months for the TVT.

Of the 16 patients who underwent repeat surgery, 56% were cured, 25% reported minimal leakage, and 19% remained unchanged.

Quality-of-life scores were similar between groups at the 6-month follow-up.

Why did the TVT outperform the TOT in this population?

Investigators theorized that there is a difference in sling axis, with the TVT placed at a more acute angle than the TOT sling. In addition, the location of the TOT sling is more distal than that of the TVT, based on ultrasonographic imaging. As a result, more effective urethral kinking and support are likely with the TVT sling, improving continence rates.

Strengths and limitations of the trial

The randomization of participants and long-term follow-up bolster the trial’s credibility.

Weaknesses include unblinded participation and postoperative surgical assessment.

Although the sample size was underpowered, there was a significant difference in the primary outcome between the two groups.

Long-term success is more likely with placement of a TVT sling in women who have SUI with ISD.

Urodynamic assessment still serves an important role in the diagnosis of ISD, and aids in preoperative planning.

LADIN A. YURTERI-KAPLAN, MD, AND AMY J. PARK, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Which sling for which SUI patient?

Mark D. Walters, MD, and Anne M. Weber, MD (Surgical Techniques, May 2012)

![]()

These videos were selected by Dr. Walters and presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS)

When ISD is present, the urethra cannot coaptate and loses its ability to maintain a watertight seal. Women who have this condition often are severely incontinent, leaking urine at low volumes and pressures and with minimal exertion.

In this randomized trial, Schierlitz and colleagues hypothesized that TOT would produce higher objective and subjective failure rates than the TVT. This was confirmed by 6-month data published in 2008.

Details of the trial

Women who had SUI were included in the trial if they had ISD based on urodynamic findings (i.e., maximum urethral closure pressure ≤20 cm H2O or Valsalva leak-point pressure ≤60 cm H2O, or both) and were randomly assigned to TVT or TOT. The primary endpoint was symptomatic SUI (confirmed by repeat urodynamic testing) that required a second procedure upon patient request.

Participants were followed for 3 years. If a patient reported symptoms, urodynamic testing was repeated. In addition, the patient was offered another surgery, usually involving placement of a TVT sling.

Schierlitz and colleagues concluded that, if TVT were used in all patients, repeat surgery would be avoided in one in every six patients. The risk of repeat surgery was 15 times greater for TOT, compared with the TVT sling. The median time to failure was 15.6 months for the TOT sling, compared with 43.7 months for the TVT.

Of the 16 patients who underwent repeat surgery, 56% were cured, 25% reported minimal leakage, and 19% remained unchanged.

Quality-of-life scores were similar between groups at the 6-month follow-up.

Why did the TVT outperform the TOT in this population?

Investigators theorized that there is a difference in sling axis, with the TVT placed at a more acute angle than the TOT sling. In addition, the location of the TOT sling is more distal than that of the TVT, based on ultrasonographic imaging. As a result, more effective urethral kinking and support are likely with the TVT sling, improving continence rates.

Strengths and limitations of the trial

The randomization of participants and long-term follow-up bolster the trial’s credibility.

Weaknesses include unblinded participation and postoperative surgical assessment.

Although the sample size was underpowered, there was a significant difference in the primary outcome between the two groups.

Long-term success is more likely with placement of a TVT sling in women who have SUI with ISD.

Urodynamic assessment still serves an important role in the diagnosis of ISD, and aids in preoperative planning.

LADIN A. YURTERI-KAPLAN, MD, AND AMY J. PARK, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

When macrosomia is suspected at term, does induction of labor lower the risk of cesarean delivery?

Fetal and neonatal macrosomia can lead to morbidity for both mother and infant. Larger babies put the mother at risk of cesarean delivery, severe perineal lacerations, and hemorrhage. The macrosomic fetus faces an elevated risk of birth trauma, shoulder dystocia, and metabolic disorders.

Earlier investigations have concluded that induction of labor does not improve outcomes and may increase the risk of cesarean delivery.1 The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) does not support suspected fetal macrosomia as an indication for induction of labor.2

Details of the study

The objective of this study was to determine whether women who were carrying a macrosomic fetus and who underwent induction of labor had a higher rate of cesarean delivery than those who were managed expectantly. Using data from the 2003 Vital Statistics Natality birth certificate registry, Cheng and colleagues compared women who underwent induction of labor at 39 weeks with women who were managed expectantly and who delivered at 40, 41, or 42 weeks (by induced or spontaneous labor).

Investigators attempted to adjust for normal gestational growth by assuming a fetal weight gain of 200 g for each additional week of gestation in the women managed expectantly. For instance, one group included women who delivered at 39 weeks (birth weight of 3,875–4,125 g), and they were compared with the group of women who delivered at 40 weeks (birth weight of 4,075–4,325 g), 41 weeks (4,275–4,525 g), and 42 weeks (4,475–4,725 g).

Using this scheme, cesarean delivery was lower in the group of women who underwent induction of labor. The induced groups were also found to have lower odds of composite neonatal morbidity.

Strengths and limitations

Because this was a retrospective study, investigators were able to use known birth weights, rather than estimated birth weights, to overcome misclassifications that can arise with estimates.

Cheng and colleagues refuted the findings of earlier studies that found a higher risk of cesarean delivery with induction of labor. They argued that those investigations compared women who underwent induction of labor with those who experienced spontaneous labor instead of the proper comparison—between women who underwent induction of labor and those who were managed expectantly. Although the comparisons they used in this study alleviate that problem, the retrospective nature of the study necessitated the use of multiple assumptions to allocate each group, creating selection bias.

Group allocations and medical histories cannot be confirmed, and the investigators acknowledge that their conclusions regarding neonatal morbidity lack statistical power.

This study explores an important issue—the prevention of cesarean delivery and poor neonatal outcomes associated with macrosomia. The comparisons in this investigation cast earlier conclusions in question and elucidate potential improvements in neonatal outcomes.

However, because of the numerous assumptions underlying the study groups, I would not recommend induction of labor to reduce the rate of cesarean delivery until further prospective data are available.

Jennifer T. Ahn, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Fetal and neonatal macrosomia can lead to morbidity for both mother and infant. Larger babies put the mother at risk of cesarean delivery, severe perineal lacerations, and hemorrhage. The macrosomic fetus faces an elevated risk of birth trauma, shoulder dystocia, and metabolic disorders.

Earlier investigations have concluded that induction of labor does not improve outcomes and may increase the risk of cesarean delivery.1 The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) does not support suspected fetal macrosomia as an indication for induction of labor.2

Details of the study

The objective of this study was to determine whether women who were carrying a macrosomic fetus and who underwent induction of labor had a higher rate of cesarean delivery than those who were managed expectantly. Using data from the 2003 Vital Statistics Natality birth certificate registry, Cheng and colleagues compared women who underwent induction of labor at 39 weeks with women who were managed expectantly and who delivered at 40, 41, or 42 weeks (by induced or spontaneous labor).

Investigators attempted to adjust for normal gestational growth by assuming a fetal weight gain of 200 g for each additional week of gestation in the women managed expectantly. For instance, one group included women who delivered at 39 weeks (birth weight of 3,875–4,125 g), and they were compared with the group of women who delivered at 40 weeks (birth weight of 4,075–4,325 g), 41 weeks (4,275–4,525 g), and 42 weeks (4,475–4,725 g).

Using this scheme, cesarean delivery was lower in the group of women who underwent induction of labor. The induced groups were also found to have lower odds of composite neonatal morbidity.

Strengths and limitations

Because this was a retrospective study, investigators were able to use known birth weights, rather than estimated birth weights, to overcome misclassifications that can arise with estimates.

Cheng and colleagues refuted the findings of earlier studies that found a higher risk of cesarean delivery with induction of labor. They argued that those investigations compared women who underwent induction of labor with those who experienced spontaneous labor instead of the proper comparison—between women who underwent induction of labor and those who were managed expectantly. Although the comparisons they used in this study alleviate that problem, the retrospective nature of the study necessitated the use of multiple assumptions to allocate each group, creating selection bias.

Group allocations and medical histories cannot be confirmed, and the investigators acknowledge that their conclusions regarding neonatal morbidity lack statistical power.

This study explores an important issue—the prevention of cesarean delivery and poor neonatal outcomes associated with macrosomia. The comparisons in this investigation cast earlier conclusions in question and elucidate potential improvements in neonatal outcomes.

However, because of the numerous assumptions underlying the study groups, I would not recommend induction of labor to reduce the rate of cesarean delivery until further prospective data are available.

Jennifer T. Ahn, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Fetal and neonatal macrosomia can lead to morbidity for both mother and infant. Larger babies put the mother at risk of cesarean delivery, severe perineal lacerations, and hemorrhage. The macrosomic fetus faces an elevated risk of birth trauma, shoulder dystocia, and metabolic disorders.

Earlier investigations have concluded that induction of labor does not improve outcomes and may increase the risk of cesarean delivery.1 The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) does not support suspected fetal macrosomia as an indication for induction of labor.2

Details of the study

The objective of this study was to determine whether women who were carrying a macrosomic fetus and who underwent induction of labor had a higher rate of cesarean delivery than those who were managed expectantly. Using data from the 2003 Vital Statistics Natality birth certificate registry, Cheng and colleagues compared women who underwent induction of labor at 39 weeks with women who were managed expectantly and who delivered at 40, 41, or 42 weeks (by induced or spontaneous labor).

Investigators attempted to adjust for normal gestational growth by assuming a fetal weight gain of 200 g for each additional week of gestation in the women managed expectantly. For instance, one group included women who delivered at 39 weeks (birth weight of 3,875–4,125 g), and they were compared with the group of women who delivered at 40 weeks (birth weight of 4,075–4,325 g), 41 weeks (4,275–4,525 g), and 42 weeks (4,475–4,725 g).

Using this scheme, cesarean delivery was lower in the group of women who underwent induction of labor. The induced groups were also found to have lower odds of composite neonatal morbidity.

Strengths and limitations

Because this was a retrospective study, investigators were able to use known birth weights, rather than estimated birth weights, to overcome misclassifications that can arise with estimates.

Cheng and colleagues refuted the findings of earlier studies that found a higher risk of cesarean delivery with induction of labor. They argued that those investigations compared women who underwent induction of labor with those who experienced spontaneous labor instead of the proper comparison—between women who underwent induction of labor and those who were managed expectantly. Although the comparisons they used in this study alleviate that problem, the retrospective nature of the study necessitated the use of multiple assumptions to allocate each group, creating selection bias.

Group allocations and medical histories cannot be confirmed, and the investigators acknowledge that their conclusions regarding neonatal morbidity lack statistical power.

This study explores an important issue—the prevention of cesarean delivery and poor neonatal outcomes associated with macrosomia. The comparisons in this investigation cast earlier conclusions in question and elucidate potential improvements in neonatal outcomes.

However, because of the numerous assumptions underlying the study groups, I would not recommend induction of labor to reduce the rate of cesarean delivery until further prospective data are available.

Jennifer T. Ahn, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis

Although the incidence of vulvar pain has increased over the past decade—thanks to both greater awareness and increasing numbers of affected women—the phenomenon is not a recent development. As early as 1874, T. Galliard Thomas wrote, “[T]his disorder, although fortunately not very frequent, is by no means very rare.”1 He went on to express “surprise” that it had not been “more generally and fully described.”

Despite the focus Thomas directed to the issue, vulvar pain did not get much attention until the 21st century, when a number of studies began to gauge its prevalence. For example, in a study in Boston of about 5,000 women, the lifetime prevalence of chronic vulvar pain was 16%.2 And in a study in Texas, the prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban, largely minority population was estimated to be 11%.3 The Boston study also reported that “nearly 40% of women chose not to seek treatment, and, of those who did, 60% saw three or more doctors, many of whom could not provide a diagnosis.”2

Clearly, there is a need for comprehensive information on vulvar pain and its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. To address the lack of guidance, OBG Management Contributing Editor Neal M. Lonky, MD, assembled a panel of experts on vulvar pain syndromes and invited them to share their considerable knowledge. The ensuing discussion, presented in three parts, offers a gold mine of information. In this opening article, the panel focuses on causes, symptomatology, and diagnosis of this common complaint.

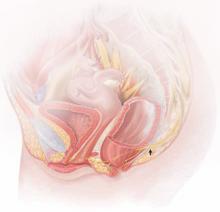

|

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain. |

![]()

Dr. Lonky: What are the most common diagnoses when vulvar pain is the complaint?

Dr. Gunter: The most common cause of chronic vulvar pain is vulvodynia, although lichen simplex chronicus, chronic yeast infections, and non-neoplastic epithelial disorders, such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, can also produce irritation and pain. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis can also cause a burning pain, although symptoms are typically more vaginal than vulvar. Yeast and lichen simplex chronicus typically produce itching, although sometimes they can present with irritation and pain, so they must be considered in the differential diagnosis. It is important to remember that many women with vulvodynia have used multiple topical agents and may have developed complex hygiene rituals in an attempt to treat their symptoms, which can result in a secondary lichen simplex chronicus.

That said, there is a high frequency of misdiagnosis with yeast. For example, in a study by Nyirjesy and colleagues, two thirds of women who were referred to a tertiary clinic for chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis were found to have a noninfectious entity instead—most commonly lichen simplex chronicus and vulvodynia.4

Dr. Edwards: The most common “diagnosis” for vulvar pain is vulvodynia. However, the definition of vulvodynia is pain—i.e., burning, rawness, irritation, soreness, aching, or stabbing or stinging sensations—in the absence of skin disease, infection, or specific neurologic disease. Therefore, even though the usual cause of vulvar pain is vulvodynia, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and skin disease, infection, and neurologic disease must be ruled out.

In regard to infection, Candida albicans and bacterial vaginosis (BV) are usually the first conditions that are considered when a patient complains of vulvar pain, but they are not common causes of vulvar pain and are never causes of chronic vulvar pain. Very rarely they may cause recurrent pain that clears, at least briefly, with treatment.

Candida albicans is usually primarily pruritic, and BV produces discharge and odor, sometimes with minor symptoms. Non-albicans Candida (e.g., Candida glabrata) is nearly always asymptomatic, but it occasionally causes irritation and burning.

Group B streptococcus is another infectious entity that very, very occasionally causes irritation and dyspareunia but is usually only a colonizer.

Herpes simplex virus is a cause of recurrent but not chronic pain.

Chronic pain is more likely to be caused by skin disease than by infection. Lichen simplex chronicus causes itching; any pain is due to erosions from scratching.

Dr. Haefner: Several other infectious conditions or their treatments can cause vulvar pain. For example, herpes (particularly primary herpes infection) is classically associated with vulvar pain. The pain is so great that, at times, the patient requires admission for pain control. Surprisingly, despite the known pain of herpes, approximately 80% of patients who have it are unaware of their diagnosis.

Although condyloma is generally a painless condition, many patients complain of pain following treatment for it, whether treatment involves topical medications or laser surgery.

Chancroid is a painful vulvar ulcer. Trichomonas can sometimes be associated with vulvar pain.

Dr. Lonky: What terminology do we use when we discuss vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: The current terminology used to describe vulvar pain was published in 2004, after years of debate over nomenclature within the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.5 The terminology lists two major categories of vulvar pain:

-

pain related to a specific disorder. This category encompasses numerous conditions that feature an abnormal appearance of the vulva (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Terminology and classification of vulvar pain from the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease

| SOURCE: Moyal-Barracco and Lynch.5 Reproduced with permission from the Journal of Reproductive Medicine. |

|

-

vulvodynia, in which the vulva appears normal, other than occasional erythema, which is most prominent at the duct openings (vestibular ducts—Bartholin’s and Skene’s).

As for vulvar pain, there are two major forms:

-

hyperalgesia (a low threshold for pain)

-

allodynia (pain in response to light touch).

Some diseases that are associated with vulvar pain do not qualify for the diagnosis of vulvodynia (Table 2) because they are associated with an abnormal appearance of the vulva.

TABLE 2

Conditions other than vulvodynia that are associated with vulvar pain

| Acute irritant contact dermatitis (e.g., erosion due to podofilox, imiquimod, cantharidin, fluorouracil, or podophyllin toxin) |

| Aphthous ulcer |

| Atrophy |

| Bartholin’s abscess |

| Candidiasis |

| Carcinoma |

| Chronic irritant contact dermatitis |

| Endometriosis |

| Herpes (simplex and zoster) |

| Immunobullous diseases (including cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, linear immunoglobulin A disease, etc.) |

| Lichen planus |

| Lichen sclerosus |

| Podophyllin overdose (see above) |

| Prolapsed urethra |

| Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Trauma |

| Trichomoniasis |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

![]()

Dr. Lonky: What skin diseases need to be ruled out before vulvodynia can be diagnosed?

Dr. Edwards: Skin diseases that affect the vulva are usually pruritic—pain is a later sign. Lichen simplex chronicus (also known as eczema) is pruritus caused by any irritant; any pain that arises is produced by visible excoriations from scratching.

Lichen sclerosus manifests as white epithelium that has a crinkling, shiny, or waxy texture. It can produce pain, especially dyspareunia. The pain is caused by erosions that arise from fragility and introital narrowing and inelasticity.

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is usually erosive and preferentially affects mucous membranes, especially the vestibule; it sometimes affects the vagina and mouth, as well.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is most likely a skin disease that affects only the vagina. It involves introital redness and a clinically and microscopically purulent vaginal discharge that also reveals parabasal cells and absent lactobacilli.

Dr. Lonky: You mentioned that neurologic diseases can sometimes cause vulvar pain. Which ones?

Dr. Edwards: Pudendal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and post-herpetic neuralgia are the most common specific neurologic causes of vulvar pain. Multiple sclerosis can also produce pain syndromes. Post-herpetic neuralgia follows herpes zoster—not herpes simplex—virus infection.

Dr. Lonky: Any other conditions that can cause vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: Aphthous ulcers are common and are often flared by stress.

Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders are also seen frequently in health-care providers’ offices; many patients who experience them report pain on the vulva.

It is always important to consider cancer when a patient has an abnormal vulvar appearance and pain that has persisted despite treatment.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: If you were to rank vulvar pain syndromes according to their prevalence, what would the most common syndromes be?

Dr. Gunter: Given the misdiagnosis of many women, who are told they have chronic yeast infection, as I mentioned, it’s hard to know which vulvar pain syndromes are most prevalent. I suspect that lichen simplex chronicus is most common, followed by vulvodynia, with chronic yeast infection a distant third.

My experience reflects what Nyirjesy and colleagues4 found: 65% to 75% of women referred to my clinic with chronic yeast actually have lichen simplex chronicus or vulvodynia. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis is also a consideration; it’s becoming more common now that the use of systemic hormone replacement therapy is decreasing.

Dr. Lonky: What about subsets of vulvodynia? Which ones are most common?

Dr. Edwards: There is good evidence of marked overlap among subsets of vulvodynia. The vast majority of women who have vulvodynia experience primarily provoked vestibular pain, regardless of age. However, I find that almost all patients also report pain that extends beyond the vestibule at times, as well as occasional unprovoked pain.

The diagnosis requires the exclusion of other causes of vulvar pain, and the subset is identified by the location of pain (that is, is it strictly localized or generalized or even migratory?) and its provoked or unprovoked nature.

Localized clitoral pain and vulvar pain localized to one side of the vulva are extremely uncommon, but they do occur. And although I rarely encounter teenagers and prepubertal children who have vulvodynia, I do have patients in both age groups who have vulvodynia.

Dr. Lonky: Are there racial differences in the prevalence of vulvodynia?

Dr. Edwards: Although several good studies show that women of African descent and white patients are equally likely to experience vulvodynia, the vast majority (99%) of my patients who have vulvodynia are white. My patients of African descent consult me primarily for itching or discharge.

My local demographics prevent me from judging the likelihood of Asians having vulvodynia, and our Hispanic population has limited access to health care.

In general, I don’t think that demographics are useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: Do your patients who have vulvodynia or another vulvar pain syndrome tend to have comorbidities? If so, is this information helpful in establishing the diagnosis and planning therapy?

Dr. Haefner: Women who have vulvodynia often have other medical problems as well. In my practice, when new patients who have vulvodynia complete their intake survey, they often report a history of headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia,6 chronic fatigue syndrome, back pain, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. These comorbidities are not particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis of vulvodynia, but they are an important consideration when choosing therapy for the patient. Often, the medications chosen to treat one condition will also benefit another condition. However, it’s important to check for potential interactions between drugs before prescribing a new treatment.

Dr. Gunter: A significant number of women who have vulvodynia also have other chronic pain syndromes. For example, the incidence of bladder pain syndrome–interstitial cystitis is 68% to 82% among women who have vulvodynia, compared with a baseline rate among all women of 6% to 11%.7-10 The rate of irritable bowel syndrome is more than doubled among women who have vulvodynia, compared with the general population (27% versus 12%).8 Another common comorbidity, hypertonic somatic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, is identified in 10% to 90% of women who have chronic vulvar pain.8,11,12 These women also have a higher incidence of nongenital pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, migraine, and TMJ dysfunction, than the general population, as Dr. Haefner noted.8,12,13

Many studies have evaluated psychological and emotional contributions to chronic vulvar pain. Pain and depression are intimately related—the incidence of depression among all people who experience chronic pain ranges from 27% to 54%, compared with 5% to 17% among the general population.14-16 The relationship is complex because chronic illness in general is associated with depression. Nevertheless, several studies have noted an increase in anxiety, stress, and depression among women who have vulvodynia.17-19

I screen every patient for depression using a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); I also screen for anxiety. I find that a significant percentage of patients in my clinic are depressed or have an anxiety disorder. Failure to address these comorbidities makes treatment very difficult. I typically prescribe citalopram (Celexa), although there is some question whether it can safely be combined with a tricyclic antidepressant. We also offer stress-reduction classes, teach every patient the value of diaphragmatic breathing, offer mind-body classes for anxiety and stress, and provide intensive programs where the patient can learn important self-care skills, such as pacing (spacing activities throughout the day in a manner that avoids aggravating the pain), and address her anxiety and stress in a more guided manner. We also have a psychologist who specializes in pain for any patient who may need one-on-one counseling.

Dr. Edwards: The presence of comorbidities is somewhat useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia. I question my diagnosis, in fact, when a patient who has vulvodynia does not have headaches, low energy, depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, sensitivity to medications, TMJ dysfunction, or urinary symptoms.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: How prevalent is a finding of pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Edwards: The prevalence and incidence of pudendal neuralgia are not known. Those who specialize in this condition think it is relatively common. I do not identify or suspect it very often. Its definitive diagnosis and management are outside the purview of the general gynecologist, but the general gynecologist should recognize the symptoms of pudendal neuralgia and refer the patient for evaluation and therapy.

Dr. Lonky: What are those symptoms?

Dr. Haefner: Pudendal neuralgia often occurs following trauma to the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve arises from sacral nerves, generally sacral nerves 2 to 4. Several tests can be utilized to diagnose this condition, including quantitative sensor tests, pudendal nerve motor latency tests, electromyography (EMG), and pudendal nerve blocks.20

Nantes Criteria allow for making a diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia (Table 3).21

TABLE 3

Nantes Criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment

| SOURCE: Labat et al.21 Reproduced with permission from Neurology and Urodynamics. |

Essential criteria

|

Complementary diagnostic criteria

|

Exclusion criteria

|

Associated signs not excluding the diagnosis

|

Initial treatments for pudendal neuralgia should be conservative. Treatments consist of lifestyle changes to prevent flare of disease. Physical therapy, medical management, nerve blocks, and alternative treatments may be beneficial.

Pudendal nerve entrapment is often exacerbated by sitting (not on a toilet seat, however) and is reduced in a standing position. It tends to increase in intensity throughout the day.22 The final treatment for pudendal nerve entrapment is surgery if the nerve is compressed. By this time, the generalist is not generally the provider who performs the surgery.

Dr. Gunter: I believe pudendal neuralgia is sometimes overdiagnosed. EMG studies of the pudendal nerve, often touted as a diagnostic tool, are unreliable (they can be abnormal after vaginal delivery or vaginal hysterectomy, for example). In my experience, bilateral pain is less likely to be pudendal neuralgia; spontaneous bilateral compression neuropathy at exactly the same level is not a common phenomenon in chronic pain.

I reserve the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia for women who have allodynia in the distribution of the pudendal nerve with severe pain on sitting, and who have exquisite tenderness when pressure is applied over the pudendal nerve (at the level of the ischial spine on vaginal examination). Typically, the vaginal sidewall on the affected side is very sensitive to light touch. I do see pudendal nerve pain after vaginal surgery when there has been some compromise of the pudendal nerve or the sacral plexus. This is typically unilateral pain.

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all. We’ll continue our discussion, with a focus on treatment.

|

MORE TO COME

|

References

1. Thomas TG. Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women. Philadelphia Pa: Henry C. Lea; 1874.

2. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82–88.

3. Lavy RJ, Hynan LS, Haley RW. Prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban minority population. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(1):59–62.

4. Nyirjesy P, Peyton C, Weitz MV, Mathew L, Culhane JF. Causes of chronic vaginitis: analysis of a prospective database of affected women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1185–1191.

5. Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(10):772–777.

6. Yunas MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):339–356.

7. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996–1002.

8. Arnold JD, Bachman GS, Rosen R, Kelly S, Rhoads GG. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(3):617–624.

9. Parsons CL, Dell J, Stanford EJ, et al. The prevalence of interstitial cystitis in gynecologic patients with pelvic pain, as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1395–1400.

10. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O’Keefe Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;174(2):576–580.

11. Engman M, Lindehammar H, Wijma B. Surface electromyography diagnostics in women with partial vaginismus with or without vulvar vestibulitis and in asymptomatic women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;25(3-4):281–294.

12. Gunter J. Vulvodynia: new thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(12):812–819.

13. Gordon AS, Panahlan-Jand M, McComb F, Melegari C, Sharp S. Characteristics of women with vulvar pain disorders: a Web-based survey. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(suppl 1):45.

14. Whitten CE, Cristobal K. Chronic pain is a chronic condition not just a symptom. Permanente J. 2005;9(3):43.

15. Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Pampati V, et al. Comparison of psychological status of chronic pain patients and the general population. Pain Physician. 2002;5(1):40–48.

16. Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining the high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):95–110.

17. Sadownik LA. Clinical correlates of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;5:40–48. Editor found in PubMed: Sadownik LA. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):679–684. Could not find the citation listed. Please confirm.

18. Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):624–632.

19. Landry T, Bergeron S. Biopsychosocial factors associated with dyspareunia in a community sample of adolescent girls. Arch Sex Behav. 2011; June 22.

20. Goldstein A, Pukall C, Goldstein I. When Sex Hurts: A Woman’s Guide to Banishing Sexual Pain. Cambridge Mass: Da Capo Lifelong Books; 2011;117–126.

21. Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, Amarenco G, Lefaucheur JP, Rigaud J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurol Urodyn. 2008;27(4):306–310.

22. Popeney C, Answell V, Renney K. Pudendal entrapment as an etiology of chronic perineal pain: Diagnosis and treatment. Neurol Urodyn. 2007;26(6):820–827.

Although the incidence of vulvar pain has increased over the past decade—thanks to both greater awareness and increasing numbers of affected women—the phenomenon is not a recent development. As early as 1874, T. Galliard Thomas wrote, “[T]his disorder, although fortunately not very frequent, is by no means very rare.”1 He went on to express “surprise” that it had not been “more generally and fully described.”

Despite the focus Thomas directed to the issue, vulvar pain did not get much attention until the 21st century, when a number of studies began to gauge its prevalence. For example, in a study in Boston of about 5,000 women, the lifetime prevalence of chronic vulvar pain was 16%.2 And in a study in Texas, the prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban, largely minority population was estimated to be 11%.3 The Boston study also reported that “nearly 40% of women chose not to seek treatment, and, of those who did, 60% saw three or more doctors, many of whom could not provide a diagnosis.”2

Clearly, there is a need for comprehensive information on vulvar pain and its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. To address the lack of guidance, OBG Management Contributing Editor Neal M. Lonky, MD, assembled a panel of experts on vulvar pain syndromes and invited them to share their considerable knowledge. The ensuing discussion, presented in three parts, offers a gold mine of information. In this opening article, the panel focuses on causes, symptomatology, and diagnosis of this common complaint.

|

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain. |

![]()

Dr. Lonky: What are the most common diagnoses when vulvar pain is the complaint?

Dr. Gunter: The most common cause of chronic vulvar pain is vulvodynia, although lichen simplex chronicus, chronic yeast infections, and non-neoplastic epithelial disorders, such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, can also produce irritation and pain. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis can also cause a burning pain, although symptoms are typically more vaginal than vulvar. Yeast and lichen simplex chronicus typically produce itching, although sometimes they can present with irritation and pain, so they must be considered in the differential diagnosis. It is important to remember that many women with vulvodynia have used multiple topical agents and may have developed complex hygiene rituals in an attempt to treat their symptoms, which can result in a secondary lichen simplex chronicus.

That said, there is a high frequency of misdiagnosis with yeast. For example, in a study by Nyirjesy and colleagues, two thirds of women who were referred to a tertiary clinic for chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis were found to have a noninfectious entity instead—most commonly lichen simplex chronicus and vulvodynia.4

Dr. Edwards: The most common “diagnosis” for vulvar pain is vulvodynia. However, the definition of vulvodynia is pain—i.e., burning, rawness, irritation, soreness, aching, or stabbing or stinging sensations—in the absence of skin disease, infection, or specific neurologic disease. Therefore, even though the usual cause of vulvar pain is vulvodynia, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and skin disease, infection, and neurologic disease must be ruled out.

In regard to infection, Candida albicans and bacterial vaginosis (BV) are usually the first conditions that are considered when a patient complains of vulvar pain, but they are not common causes of vulvar pain and are never causes of chronic vulvar pain. Very rarely they may cause recurrent pain that clears, at least briefly, with treatment.

Candida albicans is usually primarily pruritic, and BV produces discharge and odor, sometimes with minor symptoms. Non-albicans Candida (e.g., Candida glabrata) is nearly always asymptomatic, but it occasionally causes irritation and burning.

Group B streptococcus is another infectious entity that very, very occasionally causes irritation and dyspareunia but is usually only a colonizer.

Herpes simplex virus is a cause of recurrent but not chronic pain.

Chronic pain is more likely to be caused by skin disease than by infection. Lichen simplex chronicus causes itching; any pain is due to erosions from scratching.

Dr. Haefner: Several other infectious conditions or their treatments can cause vulvar pain. For example, herpes (particularly primary herpes infection) is classically associated with vulvar pain. The pain is so great that, at times, the patient requires admission for pain control. Surprisingly, despite the known pain of herpes, approximately 80% of patients who have it are unaware of their diagnosis.

Although condyloma is generally a painless condition, many patients complain of pain following treatment for it, whether treatment involves topical medications or laser surgery.

Chancroid is a painful vulvar ulcer. Trichomonas can sometimes be associated with vulvar pain.

Dr. Lonky: What terminology do we use when we discuss vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: The current terminology used to describe vulvar pain was published in 2004, after years of debate over nomenclature within the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.5 The terminology lists two major categories of vulvar pain:

-

pain related to a specific disorder. This category encompasses numerous conditions that feature an abnormal appearance of the vulva (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Terminology and classification of vulvar pain from the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease

| SOURCE: Moyal-Barracco and Lynch.5 Reproduced with permission from the Journal of Reproductive Medicine. |

|

-

vulvodynia, in which the vulva appears normal, other than occasional erythema, which is most prominent at the duct openings (vestibular ducts—Bartholin’s and Skene’s).

As for vulvar pain, there are two major forms:

-

hyperalgesia (a low threshold for pain)

-

allodynia (pain in response to light touch).

Some diseases that are associated with vulvar pain do not qualify for the diagnosis of vulvodynia (Table 2) because they are associated with an abnormal appearance of the vulva.

TABLE 2

Conditions other than vulvodynia that are associated with vulvar pain

| Acute irritant contact dermatitis (e.g., erosion due to podofilox, imiquimod, cantharidin, fluorouracil, or podophyllin toxin) |

| Aphthous ulcer |

| Atrophy |

| Bartholin’s abscess |

| Candidiasis |

| Carcinoma |

| Chronic irritant contact dermatitis |

| Endometriosis |

| Herpes (simplex and zoster) |

| Immunobullous diseases (including cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, linear immunoglobulin A disease, etc.) |

| Lichen planus |

| Lichen sclerosus |

| Podophyllin overdose (see above) |

| Prolapsed urethra |

| Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Trauma |

| Trichomoniasis |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

![]()

Dr. Lonky: What skin diseases need to be ruled out before vulvodynia can be diagnosed?

Dr. Edwards: Skin diseases that affect the vulva are usually pruritic—pain is a later sign. Lichen simplex chronicus (also known as eczema) is pruritus caused by any irritant; any pain that arises is produced by visible excoriations from scratching.

Lichen sclerosus manifests as white epithelium that has a crinkling, shiny, or waxy texture. It can produce pain, especially dyspareunia. The pain is caused by erosions that arise from fragility and introital narrowing and inelasticity.

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is usually erosive and preferentially affects mucous membranes, especially the vestibule; it sometimes affects the vagina and mouth, as well.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is most likely a skin disease that affects only the vagina. It involves introital redness and a clinically and microscopically purulent vaginal discharge that also reveals parabasal cells and absent lactobacilli.

Dr. Lonky: You mentioned that neurologic diseases can sometimes cause vulvar pain. Which ones?

Dr. Edwards: Pudendal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and post-herpetic neuralgia are the most common specific neurologic causes of vulvar pain. Multiple sclerosis can also produce pain syndromes. Post-herpetic neuralgia follows herpes zoster—not herpes simplex—virus infection.

Dr. Lonky: Any other conditions that can cause vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: Aphthous ulcers are common and are often flared by stress.

Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders are also seen frequently in health-care providers’ offices; many patients who experience them report pain on the vulva.

It is always important to consider cancer when a patient has an abnormal vulvar appearance and pain that has persisted despite treatment.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: If you were to rank vulvar pain syndromes according to their prevalence, what would the most common syndromes be?

Dr. Gunter: Given the misdiagnosis of many women, who are told they have chronic yeast infection, as I mentioned, it’s hard to know which vulvar pain syndromes are most prevalent. I suspect that lichen simplex chronicus is most common, followed by vulvodynia, with chronic yeast infection a distant third.

My experience reflects what Nyirjesy and colleagues4 found: 65% to 75% of women referred to my clinic with chronic yeast actually have lichen simplex chronicus or vulvodynia. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis is also a consideration; it’s becoming more common now that the use of systemic hormone replacement therapy is decreasing.

Dr. Lonky: What about subsets of vulvodynia? Which ones are most common?

Dr. Edwards: There is good evidence of marked overlap among subsets of vulvodynia. The vast majority of women who have vulvodynia experience primarily provoked vestibular pain, regardless of age. However, I find that almost all patients also report pain that extends beyond the vestibule at times, as well as occasional unprovoked pain.

The diagnosis requires the exclusion of other causes of vulvar pain, and the subset is identified by the location of pain (that is, is it strictly localized or generalized or even migratory?) and its provoked or unprovoked nature.

Localized clitoral pain and vulvar pain localized to one side of the vulva are extremely uncommon, but they do occur. And although I rarely encounter teenagers and prepubertal children who have vulvodynia, I do have patients in both age groups who have vulvodynia.

Dr. Lonky: Are there racial differences in the prevalence of vulvodynia?

Dr. Edwards: Although several good studies show that women of African descent and white patients are equally likely to experience vulvodynia, the vast majority (99%) of my patients who have vulvodynia are white. My patients of African descent consult me primarily for itching or discharge.

My local demographics prevent me from judging the likelihood of Asians having vulvodynia, and our Hispanic population has limited access to health care.

In general, I don’t think that demographics are useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: Do your patients who have vulvodynia or another vulvar pain syndrome tend to have comorbidities? If so, is this information helpful in establishing the diagnosis and planning therapy?

Dr. Haefner: Women who have vulvodynia often have other medical problems as well. In my practice, when new patients who have vulvodynia complete their intake survey, they often report a history of headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia,6 chronic fatigue syndrome, back pain, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. These comorbidities are not particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis of vulvodynia, but they are an important consideration when choosing therapy for the patient. Often, the medications chosen to treat one condition will also benefit another condition. However, it’s important to check for potential interactions between drugs before prescribing a new treatment.

Dr. Gunter: A significant number of women who have vulvodynia also have other chronic pain syndromes. For example, the incidence of bladder pain syndrome–interstitial cystitis is 68% to 82% among women who have vulvodynia, compared with a baseline rate among all women of 6% to 11%.7-10 The rate of irritable bowel syndrome is more than doubled among women who have vulvodynia, compared with the general population (27% versus 12%).8 Another common comorbidity, hypertonic somatic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, is identified in 10% to 90% of women who have chronic vulvar pain.8,11,12 These women also have a higher incidence of nongenital pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, migraine, and TMJ dysfunction, than the general population, as Dr. Haefner noted.8,12,13

Many studies have evaluated psychological and emotional contributions to chronic vulvar pain. Pain and depression are intimately related—the incidence of depression among all people who experience chronic pain ranges from 27% to 54%, compared with 5% to 17% among the general population.14-16 The relationship is complex because chronic illness in general is associated with depression. Nevertheless, several studies have noted an increase in anxiety, stress, and depression among women who have vulvodynia.17-19

I screen every patient for depression using a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); I also screen for anxiety. I find that a significant percentage of patients in my clinic are depressed or have an anxiety disorder. Failure to address these comorbidities makes treatment very difficult. I typically prescribe citalopram (Celexa), although there is some question whether it can safely be combined with a tricyclic antidepressant. We also offer stress-reduction classes, teach every patient the value of diaphragmatic breathing, offer mind-body classes for anxiety and stress, and provide intensive programs where the patient can learn important self-care skills, such as pacing (spacing activities throughout the day in a manner that avoids aggravating the pain), and address her anxiety and stress in a more guided manner. We also have a psychologist who specializes in pain for any patient who may need one-on-one counseling.

Dr. Edwards: The presence of comorbidities is somewhat useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia. I question my diagnosis, in fact, when a patient who has vulvodynia does not have headaches, low energy, depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, sensitivity to medications, TMJ dysfunction, or urinary symptoms.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: How prevalent is a finding of pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Edwards: The prevalence and incidence of pudendal neuralgia are not known. Those who specialize in this condition think it is relatively common. I do not identify or suspect it very often. Its definitive diagnosis and management are outside the purview of the general gynecologist, but the general gynecologist should recognize the symptoms of pudendal neuralgia and refer the patient for evaluation and therapy.

Dr. Lonky: What are those symptoms?

Dr. Haefner: Pudendal neuralgia often occurs following trauma to the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve arises from sacral nerves, generally sacral nerves 2 to 4. Several tests can be utilized to diagnose this condition, including quantitative sensor tests, pudendal nerve motor latency tests, electromyography (EMG), and pudendal nerve blocks.20

Nantes Criteria allow for making a diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia (Table 3).21

TABLE 3

Nantes Criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment

| SOURCE: Labat et al.21 Reproduced with permission from Neurology and Urodynamics. |

Essential criteria

|

Complementary diagnostic criteria

|

Exclusion criteria

|

Associated signs not excluding the diagnosis

|

Initial treatments for pudendal neuralgia should be conservative. Treatments consist of lifestyle changes to prevent flare of disease. Physical therapy, medical management, nerve blocks, and alternative treatments may be beneficial.

Pudendal nerve entrapment is often exacerbated by sitting (not on a toilet seat, however) and is reduced in a standing position. It tends to increase in intensity throughout the day.22 The final treatment for pudendal nerve entrapment is surgery if the nerve is compressed. By this time, the generalist is not generally the provider who performs the surgery.

Dr. Gunter: I believe pudendal neuralgia is sometimes overdiagnosed. EMG studies of the pudendal nerve, often touted as a diagnostic tool, are unreliable (they can be abnormal after vaginal delivery or vaginal hysterectomy, for example). In my experience, bilateral pain is less likely to be pudendal neuralgia; spontaneous bilateral compression neuropathy at exactly the same level is not a common phenomenon in chronic pain.

I reserve the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia for women who have allodynia in the distribution of the pudendal nerve with severe pain on sitting, and who have exquisite tenderness when pressure is applied over the pudendal nerve (at the level of the ischial spine on vaginal examination). Typically, the vaginal sidewall on the affected side is very sensitive to light touch. I do see pudendal nerve pain after vaginal surgery when there has been some compromise of the pudendal nerve or the sacral plexus. This is typically unilateral pain.

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all. We’ll continue our discussion, with a focus on treatment.

|

MORE TO COME

|

References

1. Thomas TG. Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women. Philadelphia Pa: Henry C. Lea; 1874.

2. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82–88.

3. Lavy RJ, Hynan LS, Haley RW. Prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban minority population. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(1):59–62.

4. Nyirjesy P, Peyton C, Weitz MV, Mathew L, Culhane JF. Causes of chronic vaginitis: analysis of a prospective database of affected women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1185–1191.

5. Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(10):772–777.

6. Yunas MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):339–356.

7. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996–1002.

8. Arnold JD, Bachman GS, Rosen R, Kelly S, Rhoads GG. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(3):617–624.

9. Parsons CL, Dell J, Stanford EJ, et al. The prevalence of interstitial cystitis in gynecologic patients with pelvic pain, as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1395–1400.

10. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O’Keefe Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;174(2):576–580.

11. Engman M, Lindehammar H, Wijma B. Surface electromyography diagnostics in women with partial vaginismus with or without vulvar vestibulitis and in asymptomatic women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;25(3-4):281–294.

12. Gunter J. Vulvodynia: new thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(12):812–819.

13. Gordon AS, Panahlan-Jand M, McComb F, Melegari C, Sharp S. Characteristics of women with vulvar pain disorders: a Web-based survey. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(suppl 1):45.

14. Whitten CE, Cristobal K. Chronic pain is a chronic condition not just a symptom. Permanente J. 2005;9(3):43.

15. Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Pampati V, et al. Comparison of psychological status of chronic pain patients and the general population. Pain Physician. 2002;5(1):40–48.

16. Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining the high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):95–110.

17. Sadownik LA. Clinical correlates of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;5:40–48. Editor found in PubMed: Sadownik LA. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):679–684. Could not find the citation listed. Please confirm.