User login

The Hospitalist only

Society of Hospital Medicine Creates Self-Assessment Tool for Hospitalist Groups

Are you looking to improve your hospital medicine group (HMG)? Would you like to measure your group against other groups?

The February 2013 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine included a seminal article for our specialty, “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists.” This paper has received a vast amount of attention around the country from hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, HMGs, and hospital executives. The report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/keychar) is a first step for physicians and executives looking to benchmark their practices, and it has stimulated discussions among many HMGs, beginning a process of self-review and considering action.

I am coming up on my 20th year as a hospitalist, and the debate over what makes a high-performing HMG has continued that entire time. In the beginning, there were questions about the mere existence of hospital medicine and HMGs. The discussion about what makes a high-performing HMG started among the physicians, medical groups, and hospitals that signed on early to the HM movement. At conferences, HMG leaders debated how to set up a program. A series of pioneer hospitalists, many with only a few years of experience, roamed the country as consultants giving advice on best practices. A professional society, the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, was born and, later, recast as the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM)—and the discussion continued.

SHM furthered the debate with such important milestones as The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development, white papers on career satisfaction and hospitalist involvement in quality/safety and transitions of care. Different types of practice arrangements developed. Some were hospital-based, some physician practice-centered. Some were local, and others were regional and national. Each of these spawned innovations in HMG processes and contributed to the growing body of best practices.

Over the past five years, a consensus regarding those best practices has seemingly developed, and the discussions are centered on fine details rather than significant differences. To that end, approximately three years ago, a small group of SHM members met and discussed how to capture this information and disseminate it better among hospitalists, HMGs, and hospitals. We had all come to a similar conclusion—high-performing HMGs share common characteristics. Furthermore, every hospital and HMG seeks excellence, striving to be the best that they can be. We settled on a plan to write this up.

After a year of debate, we sought SHM’s help in the development phase and, in early 2012, SHM’s board of directors appointed a workgroup to identify the key principles and characteristics of an effective HMG. The initial group was widened to make sure we included different backgrounds and experiences in hospital medicine. The group had a wide array of involvement in HMG models, including HMG members, HMG leaders, hospital executives, and some involved in consulting. Many of the individuals had multiple experiences. The conversation among these individuals was lively!

The workgroup developed an initial draft of characteristics, which then went through a multi-step process of review and redrafting. More than 200 individuals, representing a broad group of stakeholders in hospital medicine and in the healthcare industry in general, provided comments and feedback. In addition, the workgroup went through a two-step Delphi process to consolidate and/or eliminate characteristics that were redundant or unnecessary.

In the final framework, 47 key characteristics were defined and organized under 10 principles (see Figure 1).

The authors and SHM’s board of directors view this document as an aspirational approach to improvement. We feel it helps to “raise the bar” for the specialty of hospital medicine by laying out a roadmap of potential improvement. These principles and characteristics provide a framework for HMGs seeking to conduct self-assessments, outlining a pathway for improvement, and better defining the central role of hospitalists in coordinating team-based, patient-centered care in the acute care setting.

In enhancing quality, the approach of a gap analysis is a very effective tool. These principles provide an excellent approach to begin that review.

So how do you get started? Hopefully, your HMG has a regular meeting. Take a principle and have a conversation. For example, what do we have? What don’t we have?

Other groups may want to tackle the entire document in a daylong strategy review. Some may want an outside facilitator. Bottom line: It doesn’t matter how you do it; just start with a conversation.

Dr. Cawley is CEO of Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston. He is past president of SHM.

Reference

Are you looking to improve your hospital medicine group (HMG)? Would you like to measure your group against other groups?

The February 2013 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine included a seminal article for our specialty, “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists.” This paper has received a vast amount of attention around the country from hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, HMGs, and hospital executives. The report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/keychar) is a first step for physicians and executives looking to benchmark their practices, and it has stimulated discussions among many HMGs, beginning a process of self-review and considering action.

I am coming up on my 20th year as a hospitalist, and the debate over what makes a high-performing HMG has continued that entire time. In the beginning, there were questions about the mere existence of hospital medicine and HMGs. The discussion about what makes a high-performing HMG started among the physicians, medical groups, and hospitals that signed on early to the HM movement. At conferences, HMG leaders debated how to set up a program. A series of pioneer hospitalists, many with only a few years of experience, roamed the country as consultants giving advice on best practices. A professional society, the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, was born and, later, recast as the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM)—and the discussion continued.

SHM furthered the debate with such important milestones as The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development, white papers on career satisfaction and hospitalist involvement in quality/safety and transitions of care. Different types of practice arrangements developed. Some were hospital-based, some physician practice-centered. Some were local, and others were regional and national. Each of these spawned innovations in HMG processes and contributed to the growing body of best practices.

Over the past five years, a consensus regarding those best practices has seemingly developed, and the discussions are centered on fine details rather than significant differences. To that end, approximately three years ago, a small group of SHM members met and discussed how to capture this information and disseminate it better among hospitalists, HMGs, and hospitals. We had all come to a similar conclusion—high-performing HMGs share common characteristics. Furthermore, every hospital and HMG seeks excellence, striving to be the best that they can be. We settled on a plan to write this up.

After a year of debate, we sought SHM’s help in the development phase and, in early 2012, SHM’s board of directors appointed a workgroup to identify the key principles and characteristics of an effective HMG. The initial group was widened to make sure we included different backgrounds and experiences in hospital medicine. The group had a wide array of involvement in HMG models, including HMG members, HMG leaders, hospital executives, and some involved in consulting. Many of the individuals had multiple experiences. The conversation among these individuals was lively!

The workgroup developed an initial draft of characteristics, which then went through a multi-step process of review and redrafting. More than 200 individuals, representing a broad group of stakeholders in hospital medicine and in the healthcare industry in general, provided comments and feedback. In addition, the workgroup went through a two-step Delphi process to consolidate and/or eliminate characteristics that were redundant or unnecessary.

In the final framework, 47 key characteristics were defined and organized under 10 principles (see Figure 1).

The authors and SHM’s board of directors view this document as an aspirational approach to improvement. We feel it helps to “raise the bar” for the specialty of hospital medicine by laying out a roadmap of potential improvement. These principles and characteristics provide a framework for HMGs seeking to conduct self-assessments, outlining a pathway for improvement, and better defining the central role of hospitalists in coordinating team-based, patient-centered care in the acute care setting.

In enhancing quality, the approach of a gap analysis is a very effective tool. These principles provide an excellent approach to begin that review.

So how do you get started? Hopefully, your HMG has a regular meeting. Take a principle and have a conversation. For example, what do we have? What don’t we have?

Other groups may want to tackle the entire document in a daylong strategy review. Some may want an outside facilitator. Bottom line: It doesn’t matter how you do it; just start with a conversation.

Dr. Cawley is CEO of Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston. He is past president of SHM.

Reference

Are you looking to improve your hospital medicine group (HMG)? Would you like to measure your group against other groups?

The February 2013 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine included a seminal article for our specialty, “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists.” This paper has received a vast amount of attention around the country from hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, HMGs, and hospital executives. The report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/keychar) is a first step for physicians and executives looking to benchmark their practices, and it has stimulated discussions among many HMGs, beginning a process of self-review and considering action.

I am coming up on my 20th year as a hospitalist, and the debate over what makes a high-performing HMG has continued that entire time. In the beginning, there were questions about the mere existence of hospital medicine and HMGs. The discussion about what makes a high-performing HMG started among the physicians, medical groups, and hospitals that signed on early to the HM movement. At conferences, HMG leaders debated how to set up a program. A series of pioneer hospitalists, many with only a few years of experience, roamed the country as consultants giving advice on best practices. A professional society, the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, was born and, later, recast as the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM)—and the discussion continued.

SHM furthered the debate with such important milestones as The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development, white papers on career satisfaction and hospitalist involvement in quality/safety and transitions of care. Different types of practice arrangements developed. Some were hospital-based, some physician practice-centered. Some were local, and others were regional and national. Each of these spawned innovations in HMG processes and contributed to the growing body of best practices.

Over the past five years, a consensus regarding those best practices has seemingly developed, and the discussions are centered on fine details rather than significant differences. To that end, approximately three years ago, a small group of SHM members met and discussed how to capture this information and disseminate it better among hospitalists, HMGs, and hospitals. We had all come to a similar conclusion—high-performing HMGs share common characteristics. Furthermore, every hospital and HMG seeks excellence, striving to be the best that they can be. We settled on a plan to write this up.

After a year of debate, we sought SHM’s help in the development phase and, in early 2012, SHM’s board of directors appointed a workgroup to identify the key principles and characteristics of an effective HMG. The initial group was widened to make sure we included different backgrounds and experiences in hospital medicine. The group had a wide array of involvement in HMG models, including HMG members, HMG leaders, hospital executives, and some involved in consulting. Many of the individuals had multiple experiences. The conversation among these individuals was lively!

The workgroup developed an initial draft of characteristics, which then went through a multi-step process of review and redrafting. More than 200 individuals, representing a broad group of stakeholders in hospital medicine and in the healthcare industry in general, provided comments and feedback. In addition, the workgroup went through a two-step Delphi process to consolidate and/or eliminate characteristics that were redundant or unnecessary.

In the final framework, 47 key characteristics were defined and organized under 10 principles (see Figure 1).

The authors and SHM’s board of directors view this document as an aspirational approach to improvement. We feel it helps to “raise the bar” for the specialty of hospital medicine by laying out a roadmap of potential improvement. These principles and characteristics provide a framework for HMGs seeking to conduct self-assessments, outlining a pathway for improvement, and better defining the central role of hospitalists in coordinating team-based, patient-centered care in the acute care setting.

In enhancing quality, the approach of a gap analysis is a very effective tool. These principles provide an excellent approach to begin that review.

So how do you get started? Hopefully, your HMG has a regular meeting. Take a principle and have a conversation. For example, what do we have? What don’t we have?

Other groups may want to tackle the entire document in a daylong strategy review. Some may want an outside facilitator. Bottom line: It doesn’t matter how you do it; just start with a conversation.

Dr. Cawley is CEO of Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston. He is past president of SHM.

Reference

How Will New Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier Affect Medicare Reimbursements?

We talk a lot about value in healthcare—about how to enhance quality and reduce cost—because we all know both need an incredible amount of work. One tactic Medicare is using to improve the value equation on a large scale is aggregating and displaying physician-specific “value” metrics. These metrics, which will be used to deduct or enhance reimbursement for physicians, are known as the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier (PVBM).

This program has been enacted fairly rapidly since the passage of the Affordable Care Act; it is being rolled out first to large physician practices, then to all groups by 2017. Those with superior performance in both quality and cost will experience as much as a 2% higher reimbursement, while groups with average performance will remain financially neutral and those who show lower performance or choose not to report will be penalized up to 1% of Medicare reimbursement. This first round, for larger groups of 100-plus physicians, will affect about 30% of all U.S. physicians. The second round, for groups of 10 or more physicians, will affect about another third of physicians. The last round, for groups with fewer than 10 physicians, will be applicable to the remaining physicians practicing in the U.S.

On the face of it, the program does seem to be a potentially effective tactic for improving value on a large scale, holding individual physicians accountable for their own individual patient-care performance. A few fatal flaws in the program as it currently stands make it extraordinarily unlikely to be universally adopted by all physicians, however. Here are a few of those flaws:1,2

1 Uncertain yield: Because it is essentially a “zero-sum game” for Medicare, the incentive or penalty for a physician (or the physician’s group) depends on the performance of all the other physicians’ or groups’ performance. As a result, there is incredible uncertainty as to how strong a physician’s performance actually needs to be, year to year, to result in a bonus payment. Given that many of the metrics will require some type of investment to perform well, such as information technology infrastructure or a quality coordinator, there is an equal amount of uncertainty about how much investment will be needed to get a certain budgetary yield. For smaller physician practices, taking a 1% to 2% reduction in Medicare reimbursements may be easier to weather financially than investing in the infrastructure needed to reliably hit the quality metrics for every relevant patient.

2 Uncertain benchmarks: Unlike many hospital quality metrics, which have been publicly displayed for years, physician-level value metrics are just now being reported publicly. This leaves uncertainty about how strong a physician’s performance needs to be in order to be better than average. In the hospital value-based purchasing program, “average” performance is extremely good, in the 98% to 99% compliance range for most metrics. It is less clear what compliance range will be “average” in the physician-based program.

3 Physician variability: More than a half million physicians in the U.S. bill Medicare, and their practice types range from primary care solo practice to multi-group specialty practice. Motivating all brands to understand, measure, report, and improve quality metrics is a yeoman’s task, unlikely to be successful in the short term. Most physicians have not received any formal education or training in quality improvement, so they may not even have the skill set required to improve their metrics into a highly reliable range, worthy of bonus designation.

4 Metric identity and attribution: Because the repertoire of physician types is broad, the ability of each physician type to have a set of metrics that they understand and can identify with is extremely unlikely. In addition, attribution of patients and their associated metrics to any single physician is complicated, especially for patients who are cared for by many different physicians across a number of settings. For hospitalists, the attribution issue is a fatal flaw, as many groups routinely “hand off” patients among other hospitalists in their group, at least once if not several times during a typical hospital stay. The same is true of many other hospital-based specialty physicians.

5 Playing to the test: As with other pay-for-performance programs, there is a legitimate concern that physicians will be overwhelmingly motivated to play to the test, so that their efforts to perform exceedingly well at a few metrics will crowd out and hinder their performance on unmeasured metrics. This tendency can result in lower-value care in the sum total, even if the metrics show stellar performance.

6 Reducing the risk: As seen in other pay-for-performance programs, there is a legitimate concern that physicians will be overwhelmingly motivated to avoid caring for patients who are likely to be unpredictable, including those with multiple co-morbid conditions or with complex social situations; these patients are likely to perform less well on any metric, despite risk adjusting (which is inherently imperfect). This is a well-known and documented risk of publicly reported programs, and there is no reason to believe the PVBM program will be immune to this risk.

In Sum

Because these flaws seem so daunting at first glance, many physicians and physician groups will be tempted to reject the program outright and take the financial hit induced by nonparticipation. An alternative approach is to embrace all of the value programs outright, investing time and energy in improving the metrics that are truly valuable to both patients and providers.

Regardless of which regulatory agency is demanding performance, we need to be active participants in foraging out what metrics and attribution logic are most appropriate. For hospitalists, these could include risk-adjusted device days, appropriate prescribing and unprescribing of antibiotics, judicious utilization of diagnostic testing, and measurements of patient functional status and/or mobility.

Value metrics are here to stay, including those attributable to individual physicians; our job now is to advocate for meaningful metrics and meaningful attribution, which can and should motivate hospitalists to enhance their patients’ quality of life at a lower cost.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

References

We talk a lot about value in healthcare—about how to enhance quality and reduce cost—because we all know both need an incredible amount of work. One tactic Medicare is using to improve the value equation on a large scale is aggregating and displaying physician-specific “value” metrics. These metrics, which will be used to deduct or enhance reimbursement for physicians, are known as the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier (PVBM).

This program has been enacted fairly rapidly since the passage of the Affordable Care Act; it is being rolled out first to large physician practices, then to all groups by 2017. Those with superior performance in both quality and cost will experience as much as a 2% higher reimbursement, while groups with average performance will remain financially neutral and those who show lower performance or choose not to report will be penalized up to 1% of Medicare reimbursement. This first round, for larger groups of 100-plus physicians, will affect about 30% of all U.S. physicians. The second round, for groups of 10 or more physicians, will affect about another third of physicians. The last round, for groups with fewer than 10 physicians, will be applicable to the remaining physicians practicing in the U.S.

On the face of it, the program does seem to be a potentially effective tactic for improving value on a large scale, holding individual physicians accountable for their own individual patient-care performance. A few fatal flaws in the program as it currently stands make it extraordinarily unlikely to be universally adopted by all physicians, however. Here are a few of those flaws:1,2

1 Uncertain yield: Because it is essentially a “zero-sum game” for Medicare, the incentive or penalty for a physician (or the physician’s group) depends on the performance of all the other physicians’ or groups’ performance. As a result, there is incredible uncertainty as to how strong a physician’s performance actually needs to be, year to year, to result in a bonus payment. Given that many of the metrics will require some type of investment to perform well, such as information technology infrastructure or a quality coordinator, there is an equal amount of uncertainty about how much investment will be needed to get a certain budgetary yield. For smaller physician practices, taking a 1% to 2% reduction in Medicare reimbursements may be easier to weather financially than investing in the infrastructure needed to reliably hit the quality metrics for every relevant patient.

2 Uncertain benchmarks: Unlike many hospital quality metrics, which have been publicly displayed for years, physician-level value metrics are just now being reported publicly. This leaves uncertainty about how strong a physician’s performance needs to be in order to be better than average. In the hospital value-based purchasing program, “average” performance is extremely good, in the 98% to 99% compliance range for most metrics. It is less clear what compliance range will be “average” in the physician-based program.

3 Physician variability: More than a half million physicians in the U.S. bill Medicare, and their practice types range from primary care solo practice to multi-group specialty practice. Motivating all brands to understand, measure, report, and improve quality metrics is a yeoman’s task, unlikely to be successful in the short term. Most physicians have not received any formal education or training in quality improvement, so they may not even have the skill set required to improve their metrics into a highly reliable range, worthy of bonus designation.

4 Metric identity and attribution: Because the repertoire of physician types is broad, the ability of each physician type to have a set of metrics that they understand and can identify with is extremely unlikely. In addition, attribution of patients and their associated metrics to any single physician is complicated, especially for patients who are cared for by many different physicians across a number of settings. For hospitalists, the attribution issue is a fatal flaw, as many groups routinely “hand off” patients among other hospitalists in their group, at least once if not several times during a typical hospital stay. The same is true of many other hospital-based specialty physicians.

5 Playing to the test: As with other pay-for-performance programs, there is a legitimate concern that physicians will be overwhelmingly motivated to play to the test, so that their efforts to perform exceedingly well at a few metrics will crowd out and hinder their performance on unmeasured metrics. This tendency can result in lower-value care in the sum total, even if the metrics show stellar performance.

6 Reducing the risk: As seen in other pay-for-performance programs, there is a legitimate concern that physicians will be overwhelmingly motivated to avoid caring for patients who are likely to be unpredictable, including those with multiple co-morbid conditions or with complex social situations; these patients are likely to perform less well on any metric, despite risk adjusting (which is inherently imperfect). This is a well-known and documented risk of publicly reported programs, and there is no reason to believe the PVBM program will be immune to this risk.

In Sum

Because these flaws seem so daunting at first glance, many physicians and physician groups will be tempted to reject the program outright and take the financial hit induced by nonparticipation. An alternative approach is to embrace all of the value programs outright, investing time and energy in improving the metrics that are truly valuable to both patients and providers.

Regardless of which regulatory agency is demanding performance, we need to be active participants in foraging out what metrics and attribution logic are most appropriate. For hospitalists, these could include risk-adjusted device days, appropriate prescribing and unprescribing of antibiotics, judicious utilization of diagnostic testing, and measurements of patient functional status and/or mobility.

Value metrics are here to stay, including those attributable to individual physicians; our job now is to advocate for meaningful metrics and meaningful attribution, which can and should motivate hospitalists to enhance their patients’ quality of life at a lower cost.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

References

We talk a lot about value in healthcare—about how to enhance quality and reduce cost—because we all know both need an incredible amount of work. One tactic Medicare is using to improve the value equation on a large scale is aggregating and displaying physician-specific “value” metrics. These metrics, which will be used to deduct or enhance reimbursement for physicians, are known as the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier (PVBM).

This program has been enacted fairly rapidly since the passage of the Affordable Care Act; it is being rolled out first to large physician practices, then to all groups by 2017. Those with superior performance in both quality and cost will experience as much as a 2% higher reimbursement, while groups with average performance will remain financially neutral and those who show lower performance or choose not to report will be penalized up to 1% of Medicare reimbursement. This first round, for larger groups of 100-plus physicians, will affect about 30% of all U.S. physicians. The second round, for groups of 10 or more physicians, will affect about another third of physicians. The last round, for groups with fewer than 10 physicians, will be applicable to the remaining physicians practicing in the U.S.

On the face of it, the program does seem to be a potentially effective tactic for improving value on a large scale, holding individual physicians accountable for their own individual patient-care performance. A few fatal flaws in the program as it currently stands make it extraordinarily unlikely to be universally adopted by all physicians, however. Here are a few of those flaws:1,2

1 Uncertain yield: Because it is essentially a “zero-sum game” for Medicare, the incentive or penalty for a physician (or the physician’s group) depends on the performance of all the other physicians’ or groups’ performance. As a result, there is incredible uncertainty as to how strong a physician’s performance actually needs to be, year to year, to result in a bonus payment. Given that many of the metrics will require some type of investment to perform well, such as information technology infrastructure or a quality coordinator, there is an equal amount of uncertainty about how much investment will be needed to get a certain budgetary yield. For smaller physician practices, taking a 1% to 2% reduction in Medicare reimbursements may be easier to weather financially than investing in the infrastructure needed to reliably hit the quality metrics for every relevant patient.

2 Uncertain benchmarks: Unlike many hospital quality metrics, which have been publicly displayed for years, physician-level value metrics are just now being reported publicly. This leaves uncertainty about how strong a physician’s performance needs to be in order to be better than average. In the hospital value-based purchasing program, “average” performance is extremely good, in the 98% to 99% compliance range for most metrics. It is less clear what compliance range will be “average” in the physician-based program.

3 Physician variability: More than a half million physicians in the U.S. bill Medicare, and their practice types range from primary care solo practice to multi-group specialty practice. Motivating all brands to understand, measure, report, and improve quality metrics is a yeoman’s task, unlikely to be successful in the short term. Most physicians have not received any formal education or training in quality improvement, so they may not even have the skill set required to improve their metrics into a highly reliable range, worthy of bonus designation.

4 Metric identity and attribution: Because the repertoire of physician types is broad, the ability of each physician type to have a set of metrics that they understand and can identify with is extremely unlikely. In addition, attribution of patients and their associated metrics to any single physician is complicated, especially for patients who are cared for by many different physicians across a number of settings. For hospitalists, the attribution issue is a fatal flaw, as many groups routinely “hand off” patients among other hospitalists in their group, at least once if not several times during a typical hospital stay. The same is true of many other hospital-based specialty physicians.

5 Playing to the test: As with other pay-for-performance programs, there is a legitimate concern that physicians will be overwhelmingly motivated to play to the test, so that their efforts to perform exceedingly well at a few metrics will crowd out and hinder their performance on unmeasured metrics. This tendency can result in lower-value care in the sum total, even if the metrics show stellar performance.

6 Reducing the risk: As seen in other pay-for-performance programs, there is a legitimate concern that physicians will be overwhelmingly motivated to avoid caring for patients who are likely to be unpredictable, including those with multiple co-morbid conditions or with complex social situations; these patients are likely to perform less well on any metric, despite risk adjusting (which is inherently imperfect). This is a well-known and documented risk of publicly reported programs, and there is no reason to believe the PVBM program will be immune to this risk.

In Sum

Because these flaws seem so daunting at first glance, many physicians and physician groups will be tempted to reject the program outright and take the financial hit induced by nonparticipation. An alternative approach is to embrace all of the value programs outright, investing time and energy in improving the metrics that are truly valuable to both patients and providers.

Regardless of which regulatory agency is demanding performance, we need to be active participants in foraging out what metrics and attribution logic are most appropriate. For hospitalists, these could include risk-adjusted device days, appropriate prescribing and unprescribing of antibiotics, judicious utilization of diagnostic testing, and measurements of patient functional status and/or mobility.

Value metrics are here to stay, including those attributable to individual physicians; our job now is to advocate for meaningful metrics and meaningful attribution, which can and should motivate hospitalists to enhance their patients’ quality of life at a lower cost.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

References

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Modify Physician Quality Reporting System

Only 27% of eligible providers participated in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) in 2011—roughly 26,500 medical practices and 266,500 medical professionals, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

“A lot of physicians have walked away [from PQRS] feeling like there are not sufficient measures for them to be measured against,” says Cheryl Damberg, senior principal researcher at RAND corporation and professor at the Pardee RAND Graduate School in Santa Monica, Calif.

Encouraging more participation from hospitalists has been the goal of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) for the last several years, says Gregory Seymann, MD, SFHM, clinical professor and chief in the division of hospital medicine at University of California San Diego Health Sciences and chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee (PMRC).

“The committee has tried to champion it the best we can, making sure the measures that are there and in development meet the needs of the specialty,” Dr. Seymann says.

In just one year, the SHM committee managed to increase hospitalist reportable measures in PQRS from a paltry 11—half of which were only for stroke patients—to 21, which now includes things like diabetes exams, osteoporosis management, documentation of current medications, and community-acquired pneumonia treatment.

For Comparison’s Sake

For the first couple of phases of PQRS reporting, very few measures were relevant to hospitalists, Dr. Seymann says. The committee worked to ensure that more measures were added and billing codes modified to include those used by the specialty. Hospital medicine is relatively new, not officially recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), and hospitalists serve a unique role. Most hospitalists are in internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics, but they aren’t doing what the average primary care doctor does, like referral for breast cancer or colon cancer screening, Dr. Seymann adds. Additionally, they aren’t always the provider performing specific cardiac or neurological care.

Hospitalists’ patients usually are in the hospital because they are sick. They may have chronic disease or more complex medical needs (e.g. osteoporosis-related hip fracture) than the average population seen by a non-hospitalist PCP.

If hospitalists are compared to other PCPs, as is the plan in the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier, it “looks like our patients are dying a lot more frequently, we’re spending a lot of money, and we’re not doing primary care,” Dr. Seymann explains.

New Brand, New Push

PQRS is not new; it is the rebranding of CMS’ Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI), launched in 2006. But changes to the program are part of a national push to improve healthcare quality and patient care while reimbursing for performance on outcome- and process-based measures instead of simply for the volume of services provided. Each year, CMS updates PQRS rules.

This year is the last one in which providers will receive a bonus for reporting through PQRS. Beginning next year, practitioners that don’t meet the reporting requirements for 2013 will incur a 1.5% penalty—with additional penalties for physicians in groups of 100 or more from the value-based payment modifier. This year also serves as the performance year for 2016, when a 2% penalty for insufficient reporting will be assessed.

In early December 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published the 2014 Physician Fee Schedule and, with it, the final rules for the PQRS. Although many physicians and specialist groups believed the measures included in PQRS in previous years were too limited, CMS has added the additional reporting methodology of qualified clinical data registries (QCDR), which can include measures outside of the PQRS—a marked shift from previous policies.

The rule change, Damberg says, should take some energy out of the discussion surrounding the program and allow more physicians to participate.

“From CMS’ perspective, they want doctors delivering the recommended care and they want doctors to be able to report it out easily,” Damberg says.

Moving Forward

In 2014, providers can submit measures through the new QCDR option, or submit PQRS-identified measures through a Medicare qualified registry, through electronic health records, through the group practice reporting option (GPRO), and through claims-based reporting (though this last option is expected to be phased out over time).

Registries themselves are not new, but they can cost millions of dollars to establish and as much as a million a year to maintain. They typically contain more clinical depth and specificity than claims data, and numerous studies show the use of registries leads to improved patient outcomes.

“We don’t know how many [existing] registries are going to qualify to become these qualified clinical data registries,” says Tom Granatir, senior vice president for health policy and external relations at ABMS. “It’s going to take some time for these registries to evolve.”

Qualified clinical data registries must be in operation for at least one year to be eligible for certification by Medicare. They must include performance data from other payers beyond Medicare. Not only must QCDRs be capable of capturing and sending data, they must also provide national benchmarks to those who submit and must report back at least four times per year.

Granatir believes the QCDR rule, which allows QCDR’s to report measures beyond those included in the PQRS program, will help increase participation and will lead to more practice-based measures, but he fears it may exclude some important nuances of day-to-day patient care.

“The whole point [of quality measure reporting] is to create more public transparency…but if you have measures that are not relevant to what is actually done in practices, then it’s not a useful dataset,” he says.

Ideally, Damberg says, PQRS and other performance measures should enable physicians to do what they do better.

“I think this is really going to raise the stakes for [hospitalists] if they want to control their destiny,” Damberg says. “I think they have to get really engaged in this game and take a pro-active role in looking at where the quality gaps are and how can they better benefit patients. That’s the ultimate goal.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Wilmington, Del.

Only 27% of eligible providers participated in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) in 2011—roughly 26,500 medical practices and 266,500 medical professionals, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

“A lot of physicians have walked away [from PQRS] feeling like there are not sufficient measures for them to be measured against,” says Cheryl Damberg, senior principal researcher at RAND corporation and professor at the Pardee RAND Graduate School in Santa Monica, Calif.

Encouraging more participation from hospitalists has been the goal of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) for the last several years, says Gregory Seymann, MD, SFHM, clinical professor and chief in the division of hospital medicine at University of California San Diego Health Sciences and chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee (PMRC).

“The committee has tried to champion it the best we can, making sure the measures that are there and in development meet the needs of the specialty,” Dr. Seymann says.

In just one year, the SHM committee managed to increase hospitalist reportable measures in PQRS from a paltry 11—half of which were only for stroke patients—to 21, which now includes things like diabetes exams, osteoporosis management, documentation of current medications, and community-acquired pneumonia treatment.

For Comparison’s Sake

For the first couple of phases of PQRS reporting, very few measures were relevant to hospitalists, Dr. Seymann says. The committee worked to ensure that more measures were added and billing codes modified to include those used by the specialty. Hospital medicine is relatively new, not officially recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), and hospitalists serve a unique role. Most hospitalists are in internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics, but they aren’t doing what the average primary care doctor does, like referral for breast cancer or colon cancer screening, Dr. Seymann adds. Additionally, they aren’t always the provider performing specific cardiac or neurological care.

Hospitalists’ patients usually are in the hospital because they are sick. They may have chronic disease or more complex medical needs (e.g. osteoporosis-related hip fracture) than the average population seen by a non-hospitalist PCP.

If hospitalists are compared to other PCPs, as is the plan in the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier, it “looks like our patients are dying a lot more frequently, we’re spending a lot of money, and we’re not doing primary care,” Dr. Seymann explains.

New Brand, New Push

PQRS is not new; it is the rebranding of CMS’ Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI), launched in 2006. But changes to the program are part of a national push to improve healthcare quality and patient care while reimbursing for performance on outcome- and process-based measures instead of simply for the volume of services provided. Each year, CMS updates PQRS rules.

This year is the last one in which providers will receive a bonus for reporting through PQRS. Beginning next year, practitioners that don’t meet the reporting requirements for 2013 will incur a 1.5% penalty—with additional penalties for physicians in groups of 100 or more from the value-based payment modifier. This year also serves as the performance year for 2016, when a 2% penalty for insufficient reporting will be assessed.

In early December 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published the 2014 Physician Fee Schedule and, with it, the final rules for the PQRS. Although many physicians and specialist groups believed the measures included in PQRS in previous years were too limited, CMS has added the additional reporting methodology of qualified clinical data registries (QCDR), which can include measures outside of the PQRS—a marked shift from previous policies.

The rule change, Damberg says, should take some energy out of the discussion surrounding the program and allow more physicians to participate.

“From CMS’ perspective, they want doctors delivering the recommended care and they want doctors to be able to report it out easily,” Damberg says.

Moving Forward

In 2014, providers can submit measures through the new QCDR option, or submit PQRS-identified measures through a Medicare qualified registry, through electronic health records, through the group practice reporting option (GPRO), and through claims-based reporting (though this last option is expected to be phased out over time).

Registries themselves are not new, but they can cost millions of dollars to establish and as much as a million a year to maintain. They typically contain more clinical depth and specificity than claims data, and numerous studies show the use of registries leads to improved patient outcomes.

“We don’t know how many [existing] registries are going to qualify to become these qualified clinical data registries,” says Tom Granatir, senior vice president for health policy and external relations at ABMS. “It’s going to take some time for these registries to evolve.”

Qualified clinical data registries must be in operation for at least one year to be eligible for certification by Medicare. They must include performance data from other payers beyond Medicare. Not only must QCDRs be capable of capturing and sending data, they must also provide national benchmarks to those who submit and must report back at least four times per year.

Granatir believes the QCDR rule, which allows QCDR’s to report measures beyond those included in the PQRS program, will help increase participation and will lead to more practice-based measures, but he fears it may exclude some important nuances of day-to-day patient care.

“The whole point [of quality measure reporting] is to create more public transparency…but if you have measures that are not relevant to what is actually done in practices, then it’s not a useful dataset,” he says.

Ideally, Damberg says, PQRS and other performance measures should enable physicians to do what they do better.

“I think this is really going to raise the stakes for [hospitalists] if they want to control their destiny,” Damberg says. “I think they have to get really engaged in this game and take a pro-active role in looking at where the quality gaps are and how can they better benefit patients. That’s the ultimate goal.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Wilmington, Del.

Only 27% of eligible providers participated in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) in 2011—roughly 26,500 medical practices and 266,500 medical professionals, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

“A lot of physicians have walked away [from PQRS] feeling like there are not sufficient measures for them to be measured against,” says Cheryl Damberg, senior principal researcher at RAND corporation and professor at the Pardee RAND Graduate School in Santa Monica, Calif.

Encouraging more participation from hospitalists has been the goal of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) for the last several years, says Gregory Seymann, MD, SFHM, clinical professor and chief in the division of hospital medicine at University of California San Diego Health Sciences and chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee (PMRC).

“The committee has tried to champion it the best we can, making sure the measures that are there and in development meet the needs of the specialty,” Dr. Seymann says.

In just one year, the SHM committee managed to increase hospitalist reportable measures in PQRS from a paltry 11—half of which were only for stroke patients—to 21, which now includes things like diabetes exams, osteoporosis management, documentation of current medications, and community-acquired pneumonia treatment.

For Comparison’s Sake

For the first couple of phases of PQRS reporting, very few measures were relevant to hospitalists, Dr. Seymann says. The committee worked to ensure that more measures were added and billing codes modified to include those used by the specialty. Hospital medicine is relatively new, not officially recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), and hospitalists serve a unique role. Most hospitalists are in internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics, but they aren’t doing what the average primary care doctor does, like referral for breast cancer or colon cancer screening, Dr. Seymann adds. Additionally, they aren’t always the provider performing specific cardiac or neurological care.

Hospitalists’ patients usually are in the hospital because they are sick. They may have chronic disease or more complex medical needs (e.g. osteoporosis-related hip fracture) than the average population seen by a non-hospitalist PCP.

If hospitalists are compared to other PCPs, as is the plan in the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier, it “looks like our patients are dying a lot more frequently, we’re spending a lot of money, and we’re not doing primary care,” Dr. Seymann explains.

New Brand, New Push

PQRS is not new; it is the rebranding of CMS’ Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI), launched in 2006. But changes to the program are part of a national push to improve healthcare quality and patient care while reimbursing for performance on outcome- and process-based measures instead of simply for the volume of services provided. Each year, CMS updates PQRS rules.

This year is the last one in which providers will receive a bonus for reporting through PQRS. Beginning next year, practitioners that don’t meet the reporting requirements for 2013 will incur a 1.5% penalty—with additional penalties for physicians in groups of 100 or more from the value-based payment modifier. This year also serves as the performance year for 2016, when a 2% penalty for insufficient reporting will be assessed.

In early December 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published the 2014 Physician Fee Schedule and, with it, the final rules for the PQRS. Although many physicians and specialist groups believed the measures included in PQRS in previous years were too limited, CMS has added the additional reporting methodology of qualified clinical data registries (QCDR), which can include measures outside of the PQRS—a marked shift from previous policies.

The rule change, Damberg says, should take some energy out of the discussion surrounding the program and allow more physicians to participate.

“From CMS’ perspective, they want doctors delivering the recommended care and they want doctors to be able to report it out easily,” Damberg says.

Moving Forward

In 2014, providers can submit measures through the new QCDR option, or submit PQRS-identified measures through a Medicare qualified registry, through electronic health records, through the group practice reporting option (GPRO), and through claims-based reporting (though this last option is expected to be phased out over time).

Registries themselves are not new, but they can cost millions of dollars to establish and as much as a million a year to maintain. They typically contain more clinical depth and specificity than claims data, and numerous studies show the use of registries leads to improved patient outcomes.

“We don’t know how many [existing] registries are going to qualify to become these qualified clinical data registries,” says Tom Granatir, senior vice president for health policy and external relations at ABMS. “It’s going to take some time for these registries to evolve.”

Qualified clinical data registries must be in operation for at least one year to be eligible for certification by Medicare. They must include performance data from other payers beyond Medicare. Not only must QCDRs be capable of capturing and sending data, they must also provide national benchmarks to those who submit and must report back at least four times per year.

Granatir believes the QCDR rule, which allows QCDR’s to report measures beyond those included in the PQRS program, will help increase participation and will lead to more practice-based measures, but he fears it may exclude some important nuances of day-to-day patient care.

“The whole point [of quality measure reporting] is to create more public transparency…but if you have measures that are not relevant to what is actually done in practices, then it’s not a useful dataset,” he says.

Ideally, Damberg says, PQRS and other performance measures should enable physicians to do what they do better.

“I think this is really going to raise the stakes for [hospitalists] if they want to control their destiny,” Damberg says. “I think they have to get really engaged in this game and take a pro-active role in looking at where the quality gaps are and how can they better benefit patients. That’s the ultimate goal.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Wilmington, Del.

Hospitalist Pay Shifts from Volume to Value with Global Payment System

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

Likelihood for Readmission of Hospitalized Medicare Patients with Multiple Chronic Conditions Up 600%

600%

The increased likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission for hospitalized Medicare patients who have 10 or more chronic conditions, compared with those who have only one to four chronic conditions.4 These patients with multiple chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of Medicare beneficiaries but account for 50% of all rehospitalizations. The numbers are drawn from a 5% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries during the first nine months of 2008. Those with five to nine chronic conditions had 2.5 times the odds for being readmitted.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

- Shieh L, Pummer E, Tsui J, et al. Septris: improving sepsis recognition and management through a mobile educational game [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(Suppl 1):1053.

- Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, et al. Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):349-355.

- Daniels KR, Lee GC, Frei CR. Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections among a national cohort of hospitalized adults, 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(1):17-22.

- Berkowitz SA. Anderson GF. Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):639-641.

600%

The increased likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission for hospitalized Medicare patients who have 10 or more chronic conditions, compared with those who have only one to four chronic conditions.4 These patients with multiple chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of Medicare beneficiaries but account for 50% of all rehospitalizations. The numbers are drawn from a 5% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries during the first nine months of 2008. Those with five to nine chronic conditions had 2.5 times the odds for being readmitted.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

- Shieh L, Pummer E, Tsui J, et al. Septris: improving sepsis recognition and management through a mobile educational game [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(Suppl 1):1053.

- Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, et al. Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):349-355.

- Daniels KR, Lee GC, Frei CR. Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections among a national cohort of hospitalized adults, 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(1):17-22.

- Berkowitz SA. Anderson GF. Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):639-641.

600%

The increased likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission for hospitalized Medicare patients who have 10 or more chronic conditions, compared with those who have only one to four chronic conditions.4 These patients with multiple chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of Medicare beneficiaries but account for 50% of all rehospitalizations. The numbers are drawn from a 5% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries during the first nine months of 2008. Those with five to nine chronic conditions had 2.5 times the odds for being readmitted.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

- Shieh L, Pummer E, Tsui J, et al. Septris: improving sepsis recognition and management through a mobile educational game [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(Suppl 1):1053.

- Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, et al. Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):349-355.

- Daniels KR, Lee GC, Frei CR. Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections among a national cohort of hospitalized adults, 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(1):17-22.

- Berkowitz SA. Anderson GF. Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):639-641.

Shift from Productivity to Value-Based Compensation Gains Momentum

At the 2011 SHM annual meeting in Dallas, I served on an expert panel that reviewed the latest hospitalist survey data. Included in this review were the latest compensation and productivity figures. As the session concluded, I was satisfied that the panel had discussed important information in an accessible way; however, the keynote speaker who followed us to address an entirely different topic began his talk by pointing out that the data we had reviewed, including things like wRVUs, would very soon have little to do with compensation for any physician, regardless of specialty. He implied, quite persuasively, that we were pretty old school to be talking about wRVUs and compensation based on productivity; everyone should be prepared for and embrace compensation based on value, not production.

I hear a similar sentiment reasonably often. And I agree, but I think many make the mistake of oversimplifying the issue.

Physician Value-Based Payment

Measurement of physician performance using costs, quality, and outcomes has already begun and will influence Medicare payments to doctors beginning in 2015 for large groups (>100 providers with any mix of specialties billing under the same tax ID number) and in 2017 for smaller groups.

If Medicare is moving away from payment based on wRVUs, likely followed soon by other payors, then hospitalist compensation should do the same. But I don’t think that changes the potential role of compensation based on productivity.

Compensation Should Include Performance and Productivity Metrics

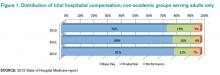

Survey data show a move from an essentially fixed annual compensation early in our field to an inclusion of components tied to performance several years before the introduction of the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier program. Data from SHM’s 2010, 2011, and 2012 State of Hospital Medicine reports (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) show that a small, but probably increasing, part of compensation has been tied to performance on things like patient satisfaction and core measures (see “Distribution of Total Hospitalist Compensation,” below). Note that the percentages in the chart refer to the fraction of total compensation dollars allocated to each domain and not the portion of hospitalists who have compensation tied to each domain.

Over the same three years, the percentage of compensation tied to productivity has been decreasing overall, while “private groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on productivity, and hospital-employed groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on performance.”

Matching Performance Compensation to Medicare’s Value-Based Modifier

It makes sense for physician compensation to generally mirror Medicare and other payor professional fee reimbursement formulas. But, in that regard, hospitalists are ahead of the market already, because the portion of dollars allocated to performance (value) in hospitalist compensation plans already exceeds the 2% or less portion of Medicare reimbursement that is influenced by performance.

Medicare will steadily increase the portion of reimbursement allocated to performance (value) and decrease the part tied solely to wRVUs. So it makes sense that hospitalist compensation plans should do the same. Who knows, within the next 5-10 years, hospitalists, and potentially doctors in all specialties, might see 20% to 50% of their compensation tied to performance. I think that might be a good thing, as long as we can come up with effective measures of performance and value—not an easy thing to do in any business or industry.

Future Role of Productivity Compensation

I don’t think all the talk about value-based reimbursement means we should abandon the idea of connecting a portion of compensation to productivity. The first two practice management columns I wrote for The Hospitalist appeared in May 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/252413/The_Sweet_Spot.html) and June 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/246297.html) and recommended tying a meaningful portion of compensation to individual hospitalist productivity, and I think it still makes sense to do so.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

In any business or industry, financial performance is connected to the amount of product produced and its value. In the future, both metrics will determine reimbursement for even the highest performing healthcare providers. The new emphasis on value won’t ever make it unnecessary to produce at a reasonable level.