User login

The Hospitalist only

Hospitalists’ Skill Sets, Work Experience Perfect for Hospitals' C-Suite Positions

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.

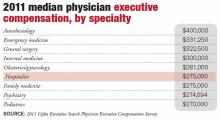

According to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search Physician Executive Compensation Survey, a survey of the American College of Physician Executives’ membership of physicians in management, the median salary of physicians in CEO positions was $393,152. That figure was $343,334 for CMO and $307,500 for chief quality and patient safety officer. The median for all physician executive positions was $305,000. Compensation was typically higher in academic medical centers and lower for hospitals and multi-specialty groups.

Hospitalists in executive positions had a 2011 median income of $275,000, according to the survey.

The survey also showed a wide range of compensation, typically dependent on the size of the institution. Some hospitalist leaders with more than 75% of their full-time-equivalent hours worked clinically “might actually take a small pay cut to make a move,” Dr. Zipper says.

Natural Progression

The hospitalist executives interviewed, for the most part, were emphatic that C-suite level leadership was not something that they imagined for themselves when they began their medical careers.

“In 2007, I could never imagine doing anything less than 100 percent clinical hospitalist work,” UCLA Hospitals’ Dr. Afsar says. “But once I started working and doing my hospitalist job day in and day out, I realized that there were many aspects of our care where I knew we could do better.”

Dr. Harte, president of South Pointe Hospital in Cleveland, says he never really thought about hospital administration as a career ambition. But, “opportunities presented themselves.”

Dr. Torcson says he was so firmly disinterested in administrative positions that when he was asked to join the Medical Executive Committee at his hospital, his first thought was “no way … I’m a doctor, not an administrator.” But after talking to some senior colleagues about it, they reminded him that he was basically obliged to say “yes.” And it ended up being a crucial component in his ascent through the ranks.

Dr. Narang imagined having a career that impacted value fairly early on, after making observations during his pediatric residency. But even he was surprised when he got the call to be CEO, after less than two years on the job.

Now, in retrospect, they all see their years working as a rank-and-file hospitalist as formative.

As a leader in a hospital, you have to be good at recruiting physicians, retaining them and developing them professionally, Dr. Harte says. That requires having clinical credibility, being a decent mentor, being a good role model, and “wearing your integrity on your sleeve.”

“I think one of the things that makes hospitalists fairly natural fits for the hospital leadership positions is that a hospital is a very complicated environment,” Dr. Harte notes. “You have pockets of enormous expertise that sometimes function like silos.

“Being a hospitalist actually trains you well for those things. By nature of what we do, we tend to be folks who do multi-disciplinary rounds. We can sit around a table or walk rounds with nurses, case managers, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and the like, and actually develop a plan of care that recognizes the expertise of the other individuals within that group. That is a very good incubator for that kind of thinking.”

Hospital leaders also have to know how everything works together within the hospital.

“Hospital medicine has this overlap with that domain as it is,” Dr. Harte continues. “We work in hospitals. It is not such a stretch then, to think that we could be running a hospital.”

Golden Opportunity

Dr. Torcson says the opportunities to lead in the hospital setting abound. A former internist, he says hospitalists are primed to “improve quality and service at the hospital level because of the system-based approach to hospital care.”

Dealing with incomplete information and uncertainty are important challenges for hospital leaders, something Dr. Afsar says are daily hurdles for hospitalists.

“By nature when you’re a hospitalist, you are a problem solver,” she says. “You don’t shy away from problems that you don’t understand.”

That problem-solver outlook is what prompted Neil Martin, MD, chief of neurosurgery at UCLA, to ask Dr. Afsar to join a quality improvement program within the department—first as a participant and then as its leader.

“She was always one of the most active and vocal and solution-oriented people on the committees that I was participating in,” Dr. Martin says. “She was not the kind of person who would describe all of the problems and leave it at that. But, rather, [she] would help identify problems and then propose solutions and then help follow through to implement solutions.”

Hospitalist C-suiters describe days dominated by meetings with executive teams, staff, and individual physicians or groups. Meetings are a necessity, as executives are tasked with crafting a vision, constantly assessing progress, and refining the approach when necessary.

Continuing at least some clinical work is important, Dr. Harte says. It depends on the organization, but he says he sees benefits that help him in his administrative duties.

“It changes the dynamic of the interaction with some of the naysayers on the medical staff,” he says. “That’s still something that I enjoy doing. I think it’s important for me, it’s important for the credibility of my job, and particularly for the organization that I work at.”

A lot of C-suiters sought out formal training in administrative areas—though not necessarily an MBA—once they realized they had an interest in administration.

Dr. Torcson says getting a master’s in medical management degree was “absolutely invaluable.”

“It was obvious to me that I had some needs to develop some additional competencies and capabilities, a different skill set than I gained in medical school and residency,” he says. “The same skill set that makes one a successful or quality physician isn’t necessarily the same skill set that you need to be an effective manager or administrator.”

Dr. Afsar completed an advanced quality improvement training program at Intermountain Healthcare, and Dr. Narang received a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard.

Dr. Harte, who does not have an advanced management degree, says that at some institutions, such as Cleveland Clinic, you can learn on the job the non-clinical areas needed to be a top leader in a hospital, including finance and strategy.

Dr. Zipper says a related degree can be a big leg up.

“If one is specifically looking to enter the C-suite, an advanced business or management degree will make that barrier a lot lower,” he says. Whether that degree is a master’s in business administration, healthcare administration, medical management, or a similar degree doesn’t seem to matter much, he adds.

When she was looking for a new CEO for Good Samaritan Medical Center, Bollinger says that she preferred to hire a physician. That candidate, she says, had to have certain leadership qualities, including the ability to create a suitable vision, curiosity, an “executive presence,” and a “tolerance of ambiguity.”

As it turns out, the value of having a physician CEO has been “probably three times what I anticipated,” she says.

If you’re a hospitalist and have an interest in rising up the leadership ladder, getting involved and getting exposure to areas of interest is where it begins.

“I would say go for it,” Dr. Afsar says. “Raising your hand and being willing to take on responsibility are kind of the first steps in getting involved. I think it’s just as much making sure that you’re the right fit for that type of work, as it is to excel and do well. Not everyone, I think, will thrive and enjoy this type of work. So I think having the opportunity to get exposed to it and see if it’s something that you enjoy is a critical piece.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.

According to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search Physician Executive Compensation Survey, a survey of the American College of Physician Executives’ membership of physicians in management, the median salary of physicians in CEO positions was $393,152. That figure was $343,334 for CMO and $307,500 for chief quality and patient safety officer. The median for all physician executive positions was $305,000. Compensation was typically higher in academic medical centers and lower for hospitals and multi-specialty groups.

Hospitalists in executive positions had a 2011 median income of $275,000, according to the survey.

The survey also showed a wide range of compensation, typically dependent on the size of the institution. Some hospitalist leaders with more than 75% of their full-time-equivalent hours worked clinically “might actually take a small pay cut to make a move,” Dr. Zipper says.

Natural Progression

The hospitalist executives interviewed, for the most part, were emphatic that C-suite level leadership was not something that they imagined for themselves when they began their medical careers.

“In 2007, I could never imagine doing anything less than 100 percent clinical hospitalist work,” UCLA Hospitals’ Dr. Afsar says. “But once I started working and doing my hospitalist job day in and day out, I realized that there were many aspects of our care where I knew we could do better.”

Dr. Harte, president of South Pointe Hospital in Cleveland, says he never really thought about hospital administration as a career ambition. But, “opportunities presented themselves.”

Dr. Torcson says he was so firmly disinterested in administrative positions that when he was asked to join the Medical Executive Committee at his hospital, his first thought was “no way … I’m a doctor, not an administrator.” But after talking to some senior colleagues about it, they reminded him that he was basically obliged to say “yes.” And it ended up being a crucial component in his ascent through the ranks.

Dr. Narang imagined having a career that impacted value fairly early on, after making observations during his pediatric residency. But even he was surprised when he got the call to be CEO, after less than two years on the job.

Now, in retrospect, they all see their years working as a rank-and-file hospitalist as formative.

As a leader in a hospital, you have to be good at recruiting physicians, retaining them and developing them professionally, Dr. Harte says. That requires having clinical credibility, being a decent mentor, being a good role model, and “wearing your integrity on your sleeve.”

“I think one of the things that makes hospitalists fairly natural fits for the hospital leadership positions is that a hospital is a very complicated environment,” Dr. Harte notes. “You have pockets of enormous expertise that sometimes function like silos.

“Being a hospitalist actually trains you well for those things. By nature of what we do, we tend to be folks who do multi-disciplinary rounds. We can sit around a table or walk rounds with nurses, case managers, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and the like, and actually develop a plan of care that recognizes the expertise of the other individuals within that group. That is a very good incubator for that kind of thinking.”

Hospital leaders also have to know how everything works together within the hospital.

“Hospital medicine has this overlap with that domain as it is,” Dr. Harte continues. “We work in hospitals. It is not such a stretch then, to think that we could be running a hospital.”

Golden Opportunity

Dr. Torcson says the opportunities to lead in the hospital setting abound. A former internist, he says hospitalists are primed to “improve quality and service at the hospital level because of the system-based approach to hospital care.”

Dealing with incomplete information and uncertainty are important challenges for hospital leaders, something Dr. Afsar says are daily hurdles for hospitalists.

“By nature when you’re a hospitalist, you are a problem solver,” she says. “You don’t shy away from problems that you don’t understand.”

That problem-solver outlook is what prompted Neil Martin, MD, chief of neurosurgery at UCLA, to ask Dr. Afsar to join a quality improvement program within the department—first as a participant and then as its leader.

“She was always one of the most active and vocal and solution-oriented people on the committees that I was participating in,” Dr. Martin says. “She was not the kind of person who would describe all of the problems and leave it at that. But, rather, [she] would help identify problems and then propose solutions and then help follow through to implement solutions.”

Hospitalist C-suiters describe days dominated by meetings with executive teams, staff, and individual physicians or groups. Meetings are a necessity, as executives are tasked with crafting a vision, constantly assessing progress, and refining the approach when necessary.

Continuing at least some clinical work is important, Dr. Harte says. It depends on the organization, but he says he sees benefits that help him in his administrative duties.

“It changes the dynamic of the interaction with some of the naysayers on the medical staff,” he says. “That’s still something that I enjoy doing. I think it’s important for me, it’s important for the credibility of my job, and particularly for the organization that I work at.”

A lot of C-suiters sought out formal training in administrative areas—though not necessarily an MBA—once they realized they had an interest in administration.

Dr. Torcson says getting a master’s in medical management degree was “absolutely invaluable.”

“It was obvious to me that I had some needs to develop some additional competencies and capabilities, a different skill set than I gained in medical school and residency,” he says. “The same skill set that makes one a successful or quality physician isn’t necessarily the same skill set that you need to be an effective manager or administrator.”

Dr. Afsar completed an advanced quality improvement training program at Intermountain Healthcare, and Dr. Narang received a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard.

Dr. Harte, who does not have an advanced management degree, says that at some institutions, such as Cleveland Clinic, you can learn on the job the non-clinical areas needed to be a top leader in a hospital, including finance and strategy.

Dr. Zipper says a related degree can be a big leg up.

“If one is specifically looking to enter the C-suite, an advanced business or management degree will make that barrier a lot lower,” he says. Whether that degree is a master’s in business administration, healthcare administration, medical management, or a similar degree doesn’t seem to matter much, he adds.

When she was looking for a new CEO for Good Samaritan Medical Center, Bollinger says that she preferred to hire a physician. That candidate, she says, had to have certain leadership qualities, including the ability to create a suitable vision, curiosity, an “executive presence,” and a “tolerance of ambiguity.”

As it turns out, the value of having a physician CEO has been “probably three times what I anticipated,” she says.

If you’re a hospitalist and have an interest in rising up the leadership ladder, getting involved and getting exposure to areas of interest is where it begins.

“I would say go for it,” Dr. Afsar says. “Raising your hand and being willing to take on responsibility are kind of the first steps in getting involved. I think it’s just as much making sure that you’re the right fit for that type of work, as it is to excel and do well. Not everyone, I think, will thrive and enjoy this type of work. So I think having the opportunity to get exposed to it and see if it’s something that you enjoy is a critical piece.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.

According to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search Physician Executive Compensation Survey, a survey of the American College of Physician Executives’ membership of physicians in management, the median salary of physicians in CEO positions was $393,152. That figure was $343,334 for CMO and $307,500 for chief quality and patient safety officer. The median for all physician executive positions was $305,000. Compensation was typically higher in academic medical centers and lower for hospitals and multi-specialty groups.

Hospitalists in executive positions had a 2011 median income of $275,000, according to the survey.

The survey also showed a wide range of compensation, typically dependent on the size of the institution. Some hospitalist leaders with more than 75% of their full-time-equivalent hours worked clinically “might actually take a small pay cut to make a move,” Dr. Zipper says.

Natural Progression

The hospitalist executives interviewed, for the most part, were emphatic that C-suite level leadership was not something that they imagined for themselves when they began their medical careers.

“In 2007, I could never imagine doing anything less than 100 percent clinical hospitalist work,” UCLA Hospitals’ Dr. Afsar says. “But once I started working and doing my hospitalist job day in and day out, I realized that there were many aspects of our care where I knew we could do better.”

Dr. Harte, president of South Pointe Hospital in Cleveland, says he never really thought about hospital administration as a career ambition. But, “opportunities presented themselves.”

Dr. Torcson says he was so firmly disinterested in administrative positions that when he was asked to join the Medical Executive Committee at his hospital, his first thought was “no way … I’m a doctor, not an administrator.” But after talking to some senior colleagues about it, they reminded him that he was basically obliged to say “yes.” And it ended up being a crucial component in his ascent through the ranks.

Dr. Narang imagined having a career that impacted value fairly early on, after making observations during his pediatric residency. But even he was surprised when he got the call to be CEO, after less than two years on the job.

Now, in retrospect, they all see their years working as a rank-and-file hospitalist as formative.

As a leader in a hospital, you have to be good at recruiting physicians, retaining them and developing them professionally, Dr. Harte says. That requires having clinical credibility, being a decent mentor, being a good role model, and “wearing your integrity on your sleeve.”

“I think one of the things that makes hospitalists fairly natural fits for the hospital leadership positions is that a hospital is a very complicated environment,” Dr. Harte notes. “You have pockets of enormous expertise that sometimes function like silos.

“Being a hospitalist actually trains you well for those things. By nature of what we do, we tend to be folks who do multi-disciplinary rounds. We can sit around a table or walk rounds with nurses, case managers, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and the like, and actually develop a plan of care that recognizes the expertise of the other individuals within that group. That is a very good incubator for that kind of thinking.”

Hospital leaders also have to know how everything works together within the hospital.

“Hospital medicine has this overlap with that domain as it is,” Dr. Harte continues. “We work in hospitals. It is not such a stretch then, to think that we could be running a hospital.”

Golden Opportunity

Dr. Torcson says the opportunities to lead in the hospital setting abound. A former internist, he says hospitalists are primed to “improve quality and service at the hospital level because of the system-based approach to hospital care.”

Dealing with incomplete information and uncertainty are important challenges for hospital leaders, something Dr. Afsar says are daily hurdles for hospitalists.

“By nature when you’re a hospitalist, you are a problem solver,” she says. “You don’t shy away from problems that you don’t understand.”

That problem-solver outlook is what prompted Neil Martin, MD, chief of neurosurgery at UCLA, to ask Dr. Afsar to join a quality improvement program within the department—first as a participant and then as its leader.

“She was always one of the most active and vocal and solution-oriented people on the committees that I was participating in,” Dr. Martin says. “She was not the kind of person who would describe all of the problems and leave it at that. But, rather, [she] would help identify problems and then propose solutions and then help follow through to implement solutions.”

Hospitalist C-suiters describe days dominated by meetings with executive teams, staff, and individual physicians or groups. Meetings are a necessity, as executives are tasked with crafting a vision, constantly assessing progress, and refining the approach when necessary.

Continuing at least some clinical work is important, Dr. Harte says. It depends on the organization, but he says he sees benefits that help him in his administrative duties.

“It changes the dynamic of the interaction with some of the naysayers on the medical staff,” he says. “That’s still something that I enjoy doing. I think it’s important for me, it’s important for the credibility of my job, and particularly for the organization that I work at.”

A lot of C-suiters sought out formal training in administrative areas—though not necessarily an MBA—once they realized they had an interest in administration.

Dr. Torcson says getting a master’s in medical management degree was “absolutely invaluable.”

“It was obvious to me that I had some needs to develop some additional competencies and capabilities, a different skill set than I gained in medical school and residency,” he says. “The same skill set that makes one a successful or quality physician isn’t necessarily the same skill set that you need to be an effective manager or administrator.”

Dr. Afsar completed an advanced quality improvement training program at Intermountain Healthcare, and Dr. Narang received a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard.

Dr. Harte, who does not have an advanced management degree, says that at some institutions, such as Cleveland Clinic, you can learn on the job the non-clinical areas needed to be a top leader in a hospital, including finance and strategy.

Dr. Zipper says a related degree can be a big leg up.

“If one is specifically looking to enter the C-suite, an advanced business or management degree will make that barrier a lot lower,” he says. Whether that degree is a master’s in business administration, healthcare administration, medical management, or a similar degree doesn’t seem to matter much, he adds.

When she was looking for a new CEO for Good Samaritan Medical Center, Bollinger says that she preferred to hire a physician. That candidate, she says, had to have certain leadership qualities, including the ability to create a suitable vision, curiosity, an “executive presence,” and a “tolerance of ambiguity.”

As it turns out, the value of having a physician CEO has been “probably three times what I anticipated,” she says.

If you’re a hospitalist and have an interest in rising up the leadership ladder, getting involved and getting exposure to areas of interest is where it begins.

“I would say go for it,” Dr. Afsar says. “Raising your hand and being willing to take on responsibility are kind of the first steps in getting involved. I think it’s just as much making sure that you’re the right fit for that type of work, as it is to excel and do well. Not everyone, I think, will thrive and enjoy this type of work. So I think having the opportunity to get exposed to it and see if it’s something that you enjoy is a critical piece.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

University of Chicago Hospitalist Evan Lyon, MD, Chats about Rational Testing and Social Context in Low-Resource Areas

Hospitalists Are Uniquely Qualified for Global Health Initiatives

Hospitalist Vincent DeGennaro, Jr., MD, MPH, didn’t train as an oncologist. But during the course of his daily duties at the Hospital Bernard Mevs in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, he administers chemotherapy at the hospital’s women’s cancer center.

“Chemotherapy was outside the realm of my specialty, but under the training and remote consultation of U.S. oncologists, I have become more comfortable with it,” says Dr. DeGennaro, an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville. Along with performing echocardiograms and working in Haiti’s only ICU, it’s an example of how global health forces him to be a “true generalist.” That’s also true of hospital medicine. In fact, the flexible schedule hospital medicine offers was a deciding factor in his career choice. Shift work in a discrete time period would allow him, he reasoned, to also follow his passion of global health.

Volunteering in low-resource settings was something that “felt right to me from the beginning,” Dr. DeGennaro says. He worked in Honduras and the Dominican Republic during medical school, mostly through medical missions organizations. Work with Partners in Health during medical school and in Rwanda after residency exposed him to the capacity-building goals of that organization. He now spends seven months of the academic year in Haiti, where he is helping Project Medishare (www.projectmedishare.org) in its efforts to build capacity and infrastructure at the country’s major trauma hospital. In July, he will be supervising clinical fellows as the director of the University of Florida’s first HM global health fellowship program.

Haitian patients have to pay for their own tests, so Dr. DeGennaro must carefully choose those that will guide his management decisions for patients. “Low-resource utilization forces you to become a better clinician,” he says. “I think we have gotten intellectually lazy in the United States, where we can order a dozen tests and let the results guide us instead of using our clinical skills to narrow what tests to order.”

Delivering care in under-resourced countries, he adds, has changed him: “I’m a much better doctor for it.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Hospitalist Vincent DeGennaro, Jr., MD, MPH, didn’t train as an oncologist. But during the course of his daily duties at the Hospital Bernard Mevs in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, he administers chemotherapy at the hospital’s women’s cancer center.

“Chemotherapy was outside the realm of my specialty, but under the training and remote consultation of U.S. oncologists, I have become more comfortable with it,” says Dr. DeGennaro, an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville. Along with performing echocardiograms and working in Haiti’s only ICU, it’s an example of how global health forces him to be a “true generalist.” That’s also true of hospital medicine. In fact, the flexible schedule hospital medicine offers was a deciding factor in his career choice. Shift work in a discrete time period would allow him, he reasoned, to also follow his passion of global health.

Volunteering in low-resource settings was something that “felt right to me from the beginning,” Dr. DeGennaro says. He worked in Honduras and the Dominican Republic during medical school, mostly through medical missions organizations. Work with Partners in Health during medical school and in Rwanda after residency exposed him to the capacity-building goals of that organization. He now spends seven months of the academic year in Haiti, where he is helping Project Medishare (www.projectmedishare.org) in its efforts to build capacity and infrastructure at the country’s major trauma hospital. In July, he will be supervising clinical fellows as the director of the University of Florida’s first HM global health fellowship program.

Haitian patients have to pay for their own tests, so Dr. DeGennaro must carefully choose those that will guide his management decisions for patients. “Low-resource utilization forces you to become a better clinician,” he says. “I think we have gotten intellectually lazy in the United States, where we can order a dozen tests and let the results guide us instead of using our clinical skills to narrow what tests to order.”

Delivering care in under-resourced countries, he adds, has changed him: “I’m a much better doctor for it.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Hospitalist Vincent DeGennaro, Jr., MD, MPH, didn’t train as an oncologist. But during the course of his daily duties at the Hospital Bernard Mevs in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, he administers chemotherapy at the hospital’s women’s cancer center.

“Chemotherapy was outside the realm of my specialty, but under the training and remote consultation of U.S. oncologists, I have become more comfortable with it,” says Dr. DeGennaro, an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville. Along with performing echocardiograms and working in Haiti’s only ICU, it’s an example of how global health forces him to be a “true generalist.” That’s also true of hospital medicine. In fact, the flexible schedule hospital medicine offers was a deciding factor in his career choice. Shift work in a discrete time period would allow him, he reasoned, to also follow his passion of global health.

Volunteering in low-resource settings was something that “felt right to me from the beginning,” Dr. DeGennaro says. He worked in Honduras and the Dominican Republic during medical school, mostly through medical missions organizations. Work with Partners in Health during medical school and in Rwanda after residency exposed him to the capacity-building goals of that organization. He now spends seven months of the academic year in Haiti, where he is helping Project Medishare (www.projectmedishare.org) in its efforts to build capacity and infrastructure at the country’s major trauma hospital. In July, he will be supervising clinical fellows as the director of the University of Florida’s first HM global health fellowship program.

Haitian patients have to pay for their own tests, so Dr. DeGennaro must carefully choose those that will guide his management decisions for patients. “Low-resource utilization forces you to become a better clinician,” he says. “I think we have gotten intellectually lazy in the United States, where we can order a dozen tests and let the results guide us instead of using our clinical skills to narrow what tests to order.”

Delivering care in under-resourced countries, he adds, has changed him: “I’m a much better doctor for it.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Global Health Hospitalists Share a Passion for Their Work

Global health hospitalists are passionate about their work. The Hospitalist asked them to expand on the reasons they choose this work.

“Working in Haiti has been the most compelling work in my life,” says Michelle Morse, MD, MPH, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and deputy chief medical officer for Partners in Health (PIH) in Boston. She has worked with the Navajo Nation in conjunction with PIH’s Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment (COPE) program. The sharing of information is “bi-directional,” Dr. Morse says.

Her Haitian colleagues, she says, have developed “transformative” systems improvements, and she’s found that her own diagnostic and physical exam skills have strengthened because of her work abroad.

“You really have to think bigger than your group of patients and bigger than your community, and think about the whole system to make things better around the world,” she says. “I think that is a fundamental part of becoming a physician.”

UCSF clinical fellow Varun Verma, MD, says he was tired of working in “fragmented volunteer assignments” with relief organizations. Three-month clinical rotations, in which he essentially functions as a teaching attending, have solved the “filling in” feeling he’d grown weary of.

“Here at St. Thérèse Hospital [in Hinche, Haiti], they do not need us to take care of patients on a moment-to-moment basis. There are Haitian clinicians for that,” he says. “Part of our job is to do medical teaching of residents and try to involve everyone in quality improvement projects. It’s sometimes challenging discussing best practices of managing conditions, given the resources at hand, but I find that the Haitian doctors are always interested in learning how we do things in the U.S.”

Evan Lyon, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the section of hospital medicine, supervises clinical fellows in the department of medicine at the University of Chicago. He believes hospitalists who take on global health assignments gain a deeper appreciation for assessing patients’ social histories.

“There’s no better way to deepen your learning of physical exam and history-taking skills than to be out here on the edge and have to rely on those skills,” he says. “Back in the states, you might order an echocardiogram before you listen to the patient’s heart. I think all of us have a different relationship to labs, testing, and X-rays when we return. But the deepest influence for me has been around understanding patients’ social histories and their social context, which is a neglected piece of American medicine.”

Sharing resources and knowledge is what drives Marwa Shoeb MD, MS, assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF. “I see this as an extension of our daily work,” she says. “We are just taking it to a different context.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in southern California.

Global health hospitalists are passionate about their work. The Hospitalist asked them to expand on the reasons they choose this work.

“Working in Haiti has been the most compelling work in my life,” says Michelle Morse, MD, MPH, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and deputy chief medical officer for Partners in Health (PIH) in Boston. She has worked with the Navajo Nation in conjunction with PIH’s Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment (COPE) program. The sharing of information is “bi-directional,” Dr. Morse says.

Her Haitian colleagues, she says, have developed “transformative” systems improvements, and she’s found that her own diagnostic and physical exam skills have strengthened because of her work abroad.

“You really have to think bigger than your group of patients and bigger than your community, and think about the whole system to make things better around the world,” she says. “I think that is a fundamental part of becoming a physician.”

UCSF clinical fellow Varun Verma, MD, says he was tired of working in “fragmented volunteer assignments” with relief organizations. Three-month clinical rotations, in which he essentially functions as a teaching attending, have solved the “filling in” feeling he’d grown weary of.

“Here at St. Thérèse Hospital [in Hinche, Haiti], they do not need us to take care of patients on a moment-to-moment basis. There are Haitian clinicians for that,” he says. “Part of our job is to do medical teaching of residents and try to involve everyone in quality improvement projects. It’s sometimes challenging discussing best practices of managing conditions, given the resources at hand, but I find that the Haitian doctors are always interested in learning how we do things in the U.S.”

Evan Lyon, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the section of hospital medicine, supervises clinical fellows in the department of medicine at the University of Chicago. He believes hospitalists who take on global health assignments gain a deeper appreciation for assessing patients’ social histories.

“There’s no better way to deepen your learning of physical exam and history-taking skills than to be out here on the edge and have to rely on those skills,” he says. “Back in the states, you might order an echocardiogram before you listen to the patient’s heart. I think all of us have a different relationship to labs, testing, and X-rays when we return. But the deepest influence for me has been around understanding patients’ social histories and their social context, which is a neglected piece of American medicine.”

Sharing resources and knowledge is what drives Marwa Shoeb MD, MS, assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF. “I see this as an extension of our daily work,” she says. “We are just taking it to a different context.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in southern California.

Global health hospitalists are passionate about their work. The Hospitalist asked them to expand on the reasons they choose this work.

“Working in Haiti has been the most compelling work in my life,” says Michelle Morse, MD, MPH, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and deputy chief medical officer for Partners in Health (PIH) in Boston. She has worked with the Navajo Nation in conjunction with PIH’s Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment (COPE) program. The sharing of information is “bi-directional,” Dr. Morse says.

Her Haitian colleagues, she says, have developed “transformative” systems improvements, and she’s found that her own diagnostic and physical exam skills have strengthened because of her work abroad.

“You really have to think bigger than your group of patients and bigger than your community, and think about the whole system to make things better around the world,” she says. “I think that is a fundamental part of becoming a physician.”

UCSF clinical fellow Varun Verma, MD, says he was tired of working in “fragmented volunteer assignments” with relief organizations. Three-month clinical rotations, in which he essentially functions as a teaching attending, have solved the “filling in” feeling he’d grown weary of.

“Here at St. Thérèse Hospital [in Hinche, Haiti], they do not need us to take care of patients on a moment-to-moment basis. There are Haitian clinicians for that,” he says. “Part of our job is to do medical teaching of residents and try to involve everyone in quality improvement projects. It’s sometimes challenging discussing best practices of managing conditions, given the resources at hand, but I find that the Haitian doctors are always interested in learning how we do things in the U.S.”

Evan Lyon, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the section of hospital medicine, supervises clinical fellows in the department of medicine at the University of Chicago. He believes hospitalists who take on global health assignments gain a deeper appreciation for assessing patients’ social histories.

“There’s no better way to deepen your learning of physical exam and history-taking skills than to be out here on the edge and have to rely on those skills,” he says. “Back in the states, you might order an echocardiogram before you listen to the patient’s heart. I think all of us have a different relationship to labs, testing, and X-rays when we return. But the deepest influence for me has been around understanding patients’ social histories and their social context, which is a neglected piece of American medicine.”

Sharing resources and knowledge is what drives Marwa Shoeb MD, MS, assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF. “I see this as an extension of our daily work,” she says. “We are just taking it to a different context.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in southern California.

Brett Hendel-Paterson, MD, Discusses Advantages of Needs Assessments

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Hendel-Paterson, as he discusses the advantages of a good needs assessment.

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Hendel-Paterson, as he discusses the advantages of a good needs assessment.

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Hendel-Paterson, as he discusses the advantages of a good needs assessment.

Problem Solving In Multi-Site Hospital Medicine Groups

Serving as the lead physician for a hospital medicine group (HMG) makes for challenging work. And the challenges and complexity only increase for anyone who serves as the physician leader for multiple practice sites in the same hospital system. In my November 2013 column on multi-site HMG leaders, I listed a few of the tricky issues they face and will mention a few more here.

Large-Small Friction

Unfortunately, tension between hospitalists at the big hospital and doctors at the small, “feeder” hospitals seems pretty common, and I think it’s due largely to high stress and a wide variation in workload, neither of which are in our direct control. At facilities where there is significant tension, I’m impressed by how vigorously the hospitalists at both the small and large hospitals argue that their own site faces the most stress and challenges. (This is a little like the endless debate about who works harder, those who work with residents and those who don’t.)

The hospitalists at the small site point out that they work with little or no subspecialty help and might even have to take night call from home while working during the day. Those at the big hospital say they are the ones with the very large scope of clinical practice and that, rather than making their life easier, the presence of lots of subspecialists makes for additional work coordinating care and communicating with all parties.

Where it exists, this tension is most evident during a transfer from one of the small hospitals to the large one. After all, one of the reasons to form a system of hospitals is so that nearly all patient needs can be met at one of the facilities in the system. Yet, for many reasons, the hospitalists at the large hospital are—sometimes—not as receptive to transfers as might be ideal. They might be short staffed or facing a high census or an unusually high number of admissions from their own ED. Or, perhaps, they’re concerned that the subspecialty services for which the patient is being transferred (e.g. to be scoped by a GI doctor) won’t be as helpful or prompt as needed. Or maybe they’ve felt “burned” by their colleagues at the small hospital for past transfers that didn’t seem necessary.

The result can be that the doctors at the smaller hospital complain that the “mother ship” hospitalists often are unfriendly and unreceptive to transfer requests. Although there may not be a definitive “cure” for this issue, there are several ways to help address the problem.

- In my last column, I mentioned the value of one or more in-person meetings between those who tend to be on the sending and receiving end of transfers, to establish some criteria regarding transfers that are appropriate and review the process of requesting a transfer and making the associated arrangements. In most cases there will be value in the parties meeting routinely—perhaps two to four times annually—to review how the system is working and address any difficulties.

- Periodic social meetings among the hospitalists at each site will help to form relationships that can make it less likely that any conversation about transfers will go in an unhelpful direction. Things can be very different when the people on each end of the phone call know each other personally.

- Record the phone calls between those seeking and accepting/declining each transfer. Scott Rissmiller, MD, the lead hospitalist for the 17 practice sites in Carolinas Healthcare, has said that having underperforming doctors listen to recordings of their phone calls about transfers has, in most cases he’s been involved with, proven to be a very effective way to encourage improvement.

Shared Staffing

The small hospitals in many systems sometimes struggle to find a way to provide economical night coverage. Hospitals below a certain size find it very difficult to justify a separate, in-house night provider. Some hospital systems have had success sharing night staffing, with the large hospital’s night hospitalist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant providing telephone coverage for “cross cover” issues that arise after hours.

For example, when a nurse at the small hospital needs to contact a night hospitalist, staff will page the provider at the big hospital, and, in many cases, the issue can be managed effectively by phone. This works best when both hospitals are on the same electronic medical record, so that the responding provider can look through the record as needed.

The hospitalist at the small hospital typically stays on back-up call and is contacted if bedside attention is required.

Or, if the large and small hospitals are a short drive apart, the night hospitalist at the large facility might make the short drive to the small hospital when needed. In the case of emergencies (i.e., a code blue), the in-house night ED physician is relied on as the first responder.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Serving as the lead physician for a hospital medicine group (HMG) makes for challenging work. And the challenges and complexity only increase for anyone who serves as the physician leader for multiple practice sites in the same hospital system. In my November 2013 column on multi-site HMG leaders, I listed a few of the tricky issues they face and will mention a few more here.

Large-Small Friction

Unfortunately, tension between hospitalists at the big hospital and doctors at the small, “feeder” hospitals seems pretty common, and I think it’s due largely to high stress and a wide variation in workload, neither of which are in our direct control. At facilities where there is significant tension, I’m impressed by how vigorously the hospitalists at both the small and large hospitals argue that their own site faces the most stress and challenges. (This is a little like the endless debate about who works harder, those who work with residents and those who don’t.)

The hospitalists at the small site point out that they work with little or no subspecialty help and might even have to take night call from home while working during the day. Those at the big hospital say they are the ones with the very large scope of clinical practice and that, rather than making their life easier, the presence of lots of subspecialists makes for additional work coordinating care and communicating with all parties.

Where it exists, this tension is most evident during a transfer from one of the small hospitals to the large one. After all, one of the reasons to form a system of hospitals is so that nearly all patient needs can be met at one of the facilities in the system. Yet, for many reasons, the hospitalists at the large hospital are—sometimes—not as receptive to transfers as might be ideal. They might be short staffed or facing a high census or an unusually high number of admissions from their own ED. Or, perhaps, they’re concerned that the subspecialty services for which the patient is being transferred (e.g. to be scoped by a GI doctor) won’t be as helpful or prompt as needed. Or maybe they’ve felt “burned” by their colleagues at the small hospital for past transfers that didn’t seem necessary.

The result can be that the doctors at the smaller hospital complain that the “mother ship” hospitalists often are unfriendly and unreceptive to transfer requests. Although there may not be a definitive “cure” for this issue, there are several ways to help address the problem.

- In my last column, I mentioned the value of one or more in-person meetings between those who tend to be on the sending and receiving end of transfers, to establish some criteria regarding transfers that are appropriate and review the process of requesting a transfer and making the associated arrangements. In most cases there will be value in the parties meeting routinely—perhaps two to four times annually—to review how the system is working and address any difficulties.

- Periodic social meetings among the hospitalists at each site will help to form relationships that can make it less likely that any conversation about transfers will go in an unhelpful direction. Things can be very different when the people on each end of the phone call know each other personally.

- Record the phone calls between those seeking and accepting/declining each transfer. Scott Rissmiller, MD, the lead hospitalist for the 17 practice sites in Carolinas Healthcare, has said that having underperforming doctors listen to recordings of their phone calls about transfers has, in most cases he’s been involved with, proven to be a very effective way to encourage improvement.

Shared Staffing

The small hospitals in many systems sometimes struggle to find a way to provide economical night coverage. Hospitals below a certain size find it very difficult to justify a separate, in-house night provider. Some hospital systems have had success sharing night staffing, with the large hospital’s night hospitalist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant providing telephone coverage for “cross cover” issues that arise after hours.

For example, when a nurse at the small hospital needs to contact a night hospitalist, staff will page the provider at the big hospital, and, in many cases, the issue can be managed effectively by phone. This works best when both hospitals are on the same electronic medical record, so that the responding provider can look through the record as needed.

The hospitalist at the small hospital typically stays on back-up call and is contacted if bedside attention is required.

Or, if the large and small hospitals are a short drive apart, the night hospitalist at the large facility might make the short drive to the small hospital when needed. In the case of emergencies (i.e., a code blue), the in-house night ED physician is relied on as the first responder.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Serving as the lead physician for a hospital medicine group (HMG) makes for challenging work. And the challenges and complexity only increase for anyone who serves as the physician leader for multiple practice sites in the same hospital system. In my November 2013 column on multi-site HMG leaders, I listed a few of the tricky issues they face and will mention a few more here.

Large-Small Friction

Unfortunately, tension between hospitalists at the big hospital and doctors at the small, “feeder” hospitals seems pretty common, and I think it’s due largely to high stress and a wide variation in workload, neither of which are in our direct control. At facilities where there is significant tension, I’m impressed by how vigorously the hospitalists at both the small and large hospitals argue that their own site faces the most stress and challenges. (This is a little like the endless debate about who works harder, those who work with residents and those who don’t.)

The hospitalists at the small site point out that they work with little or no subspecialty help and might even have to take night call from home while working during the day. Those at the big hospital say they are the ones with the very large scope of clinical practice and that, rather than making their life easier, the presence of lots of subspecialists makes for additional work coordinating care and communicating with all parties.

Where it exists, this tension is most evident during a transfer from one of the small hospitals to the large one. After all, one of the reasons to form a system of hospitals is so that nearly all patient needs can be met at one of the facilities in the system. Yet, for many reasons, the hospitalists at the large hospital are—sometimes—not as receptive to transfers as might be ideal. They might be short staffed or facing a high census or an unusually high number of admissions from their own ED. Or, perhaps, they’re concerned that the subspecialty services for which the patient is being transferred (e.g. to be scoped by a GI doctor) won’t be as helpful or prompt as needed. Or maybe they’ve felt “burned” by their colleagues at the small hospital for past transfers that didn’t seem necessary.

The result can be that the doctors at the smaller hospital complain that the “mother ship” hospitalists often are unfriendly and unreceptive to transfer requests. Although there may not be a definitive “cure” for this issue, there are several ways to help address the problem.

- In my last column, I mentioned the value of one or more in-person meetings between those who tend to be on the sending and receiving end of transfers, to establish some criteria regarding transfers that are appropriate and review the process of requesting a transfer and making the associated arrangements. In most cases there will be value in the parties meeting routinely—perhaps two to four times annually—to review how the system is working and address any difficulties.

- Periodic social meetings among the hospitalists at each site will help to form relationships that can make it less likely that any conversation about transfers will go in an unhelpful direction. Things can be very different when the people on each end of the phone call know each other personally.

- Record the phone calls between those seeking and accepting/declining each transfer. Scott Rissmiller, MD, the lead hospitalist for the 17 practice sites in Carolinas Healthcare, has said that having underperforming doctors listen to recordings of their phone calls about transfers has, in most cases he’s been involved with, proven to be a very effective way to encourage improvement.

Shared Staffing

The small hospitals in many systems sometimes struggle to find a way to provide economical night coverage. Hospitals below a certain size find it very difficult to justify a separate, in-house night provider. Some hospital systems have had success sharing night staffing, with the large hospital’s night hospitalist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant providing telephone coverage for “cross cover” issues that arise after hours.

For example, when a nurse at the small hospital needs to contact a night hospitalist, staff will page the provider at the big hospital, and, in many cases, the issue can be managed effectively by phone. This works best when both hospitals are on the same electronic medical record, so that the responding provider can look through the record as needed.

The hospitalist at the small hospital typically stays on back-up call and is contacted if bedside attention is required.

Or, if the large and small hospitals are a short drive apart, the night hospitalist at the large facility might make the short drive to the small hospital when needed. In the case of emergencies (i.e., a code blue), the in-house night ED physician is relied on as the first responder.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Federal Grant Extends Anti-Infection Initiative

The American Hospital Association’s Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET) recently obtained a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to expand CUSP, the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program for reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) and other healthcare-associated infections, to nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities nationwide.

CUSP has posted a 40% reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) in 1,000 participating hospitals by providing education and support and an evidence-based protocol. The grant will be administered by HRET in partnership with others, including the University of Michigan Health System, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, and SHM.

Meanwhile, a study published in the American Journal of Infection Control found that rates of catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adult patients given urinary catheter placements dropped nationwide to 5.3% in 2010 from 9.4% in 2001.3 The retrospective analysis of data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey found that CAUTI-related mortality and associated length of hospital stay also declined during the same period.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

The American Hospital Association’s Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET) recently obtained a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to expand CUSP, the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program for reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) and other healthcare-associated infections, to nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities nationwide.

CUSP has posted a 40% reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) in 1,000 participating hospitals by providing education and support and an evidence-based protocol. The grant will be administered by HRET in partnership with others, including the University of Michigan Health System, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, and SHM.

Meanwhile, a study published in the American Journal of Infection Control found that rates of catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adult patients given urinary catheter placements dropped nationwide to 5.3% in 2010 from 9.4% in 2001.3 The retrospective analysis of data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey found that CAUTI-related mortality and associated length of hospital stay also declined during the same period.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

The American Hospital Association’s Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET) recently obtained a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to expand CUSP, the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program for reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) and other healthcare-associated infections, to nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities nationwide.

CUSP has posted a 40% reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) in 1,000 participating hospitals by providing education and support and an evidence-based protocol. The grant will be administered by HRET in partnership with others, including the University of Michigan Health System, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, and SHM.

Meanwhile, a study published in the American Journal of Infection Control found that rates of catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adult patients given urinary catheter placements dropped nationwide to 5.3% in 2010 from 9.4% in 2001.3 The retrospective analysis of data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey found that CAUTI-related mortality and associated length of hospital stay also declined during the same period.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

Patient Activation Measure Tool Helps Patients Avoid Hospital Readmissions

–Dr. Hibbard

A recent article in the Journal of Internal Medicine draws a strong link between readmission rates and the degree to which patients are activated—possessing the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage their own health post-discharge.2 Co-author Judith Hibbard, DrPh, professor of health policy at the University of Oregon, is the lead inventor of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), an eight-item tool that assigns patients to one of four levels of activation.

In a sample of 700 patients discharged from Boston Medical Center, those with the lowest levels of activation had 1.75 times the risk of 30-day readmissions, more ED visits, and greater utilization of health services, even after adjusting for severity of illness and demographics.

“Contrary to what some may assume, patients who demonstrate a lower level of activation do not fall into any specific racial, economic, or educational demographic,” Dr. Hibbard says, adding that providers should not expect to be able to reliably judge their patients’ ability to self-manage outside of the hospital. “We know that people who measure low tend to have little confidence in their ability to manage their own health. They feel overwhelmed, show poor problem-solving skills, don’t understand what professionals are telling them, and, as a result, may not pay close attention.”

Dr. Hibbard says higher activation scores reflect greater focus on personal health and the effort to monitor it—with more confidence.

The take-home message for hospitalists, she says, is to understand the importance of their patients’ activation level and to tailor interventions accordingly.

“Those with low activation may need more support,” such as post-discharge home visits instead of just a phone call. Low-activation patients should not be overwhelmed with information but should instead be given just a few prioritized key points, combined with the use of reinforcing communications techniques such as teach-back.

“Someone should sit with them and help negotiate their health behaviors,” she adds. “That’s how they get more activated. It doesn’t have to be a doctor going through these things. But just using the clinical lens to understand your patients is not enough.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

–Dr. Hibbard

A recent article in the Journal of Internal Medicine draws a strong link between readmission rates and the degree to which patients are activated—possessing the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage their own health post-discharge.2 Co-author Judith Hibbard, DrPh, professor of health policy at the University of Oregon, is the lead inventor of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), an eight-item tool that assigns patients to one of four levels of activation.

In a sample of 700 patients discharged from Boston Medical Center, those with the lowest levels of activation had 1.75 times the risk of 30-day readmissions, more ED visits, and greater utilization of health services, even after adjusting for severity of illness and demographics.

“Contrary to what some may assume, patients who demonstrate a lower level of activation do not fall into any specific racial, economic, or educational demographic,” Dr. Hibbard says, adding that providers should not expect to be able to reliably judge their patients’ ability to self-manage outside of the hospital. “We know that people who measure low tend to have little confidence in their ability to manage their own health. They feel overwhelmed, show poor problem-solving skills, don’t understand what professionals are telling them, and, as a result, may not pay close attention.”

Dr. Hibbard says higher activation scores reflect greater focus on personal health and the effort to monitor it—with more confidence.

The take-home message for hospitalists, she says, is to understand the importance of their patients’ activation level and to tailor interventions accordingly.

“Those with low activation may need more support,” such as post-discharge home visits instead of just a phone call. Low-activation patients should not be overwhelmed with information but should instead be given just a few prioritized key points, combined with the use of reinforcing communications techniques such as teach-back.

“Someone should sit with them and help negotiate their health behaviors,” she adds. “That’s how they get more activated. It doesn’t have to be a doctor going through these things. But just using the clinical lens to understand your patients is not enough.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

–Dr. Hibbard

A recent article in the Journal of Internal Medicine draws a strong link between readmission rates and the degree to which patients are activated—possessing the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage their own health post-discharge.2 Co-author Judith Hibbard, DrPh, professor of health policy at the University of Oregon, is the lead inventor of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), an eight-item tool that assigns patients to one of four levels of activation.

In a sample of 700 patients discharged from Boston Medical Center, those with the lowest levels of activation had 1.75 times the risk of 30-day readmissions, more ED visits, and greater utilization of health services, even after adjusting for severity of illness and demographics.