User login

MINIDEP: A simple, self-administered depression screening tool

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

Venlafaxine discontinuation syndrome: Prevention and management

Most antidepressants lead to adverse discontinuation symptoms when they are abruptly stopped or rapidly tapered. Antidepressants with a short half-life, such as paroxetine and venlafaxine, can cause significantly more severe discontinuation symptoms compared with antidepressants with a longer half-life.

One culprit in particular

Among serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), venlafaxine is notorious for severe discontinuation symptoms. Venlafaxine has a half-life of 3 to 7 hours, and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, possesses a half-life of 9 to 13 hours. Higher frequency of discontinuation symptoms is associated with the use of higher dosages of venlafaxine and longer duration of treatment.

Venlafaxine is available in immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) formulations. Venlafaxine XR has a slower release, extending the time to peak plasma concentration and, therefore, has once daily dosing and fewer side effects; however, it offers no substantial advantage over IR formulation in terms of diminished withdrawal effects. Desvenlafaxine also is marketed as an antidepressant and, although one can speculate that the drug would have a lower rate of discontinuation symptoms than venlafaxine, no evidence supports this hypothesis.

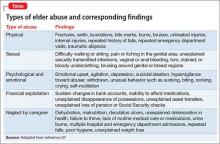

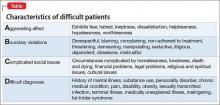

A range of venlafaxine discontinuation symptoms have been reported (Table).1

Preventing discontinuation symptoms

Patients for whom venlafaxine is prescribed should be informed about discontinuation symptoms, especially those who have a history of noncompliance. Monitor patients closely for discontinuation symptoms when venlafaxine is stopped—even if the patient is switched to another antidepressant. A gradual dosage reduction is recommended rather than abrupt termination or rapid dosage reduction. Immediately switching from venlafaxine to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) generally is not recommended, although it could alleviate some discontinuation symptoms2; cross-taper medication over 2 to 3 weeks.

Switching from venlafaxine to another SNRI, such as duloxetine, is less well studied. At venlafaxine dosages of <150 mg/d, an immediate switch to another SNRI of equivalent dosage generally is well-tolerated. For higher dosages, a gradual cross-taper is advised.2

Most patients tolerate a venlafaxine dosage reduction by 75 mg/d, at 1-week intervals. For patients who experience severe discontinuation symptoms with a minor dosage reduction, venlafaxine can be tapered over 10 months with approximately 1% dosage reduction every 3 days. Stahl3 recommends dissolving the tablet in 100 mL of juice, discarding 1 mL, and drinking the rest. After 3 days, 2 mL can be discarded, etc.

Another strategy to prevent discontinuation syndrome is to initiate fluoxetine—an SSRI with a long half-life—before taper; maintain fluoxetine dosage while venlafaxine is tapered; and then taper fluoxetine.

Managing discontinuation symptoms

If your patient experiences significant discontinuation symptoms, resume the last prescribed venlafaxine dosage, with a plan for a more gradual taper. Acute discontinuation syndrome also can be treated by initiating fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d; after symptoms resolve, fluoxetine can be tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Effexor (venlafaxine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012.

2. Hirsch M, Birnbaum RJ. Antidepressant medication in adults: switching and discontinuing medication. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/antidepressant-medicationin-adults-switching-and-discontinuing-medication. Updated January 16, 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

3. Stahl SM. Venlafaxine. In: Stahl SM. The prescriber’s guide (Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology). 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011:637-638.

Most antidepressants lead to adverse discontinuation symptoms when they are abruptly stopped or rapidly tapered. Antidepressants with a short half-life, such as paroxetine and venlafaxine, can cause significantly more severe discontinuation symptoms compared with antidepressants with a longer half-life.

One culprit in particular

Among serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), venlafaxine is notorious for severe discontinuation symptoms. Venlafaxine has a half-life of 3 to 7 hours, and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, possesses a half-life of 9 to 13 hours. Higher frequency of discontinuation symptoms is associated with the use of higher dosages of venlafaxine and longer duration of treatment.

Venlafaxine is available in immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) formulations. Venlafaxine XR has a slower release, extending the time to peak plasma concentration and, therefore, has once daily dosing and fewer side effects; however, it offers no substantial advantage over IR formulation in terms of diminished withdrawal effects. Desvenlafaxine also is marketed as an antidepressant and, although one can speculate that the drug would have a lower rate of discontinuation symptoms than venlafaxine, no evidence supports this hypothesis.

A range of venlafaxine discontinuation symptoms have been reported (Table).1

Preventing discontinuation symptoms

Patients for whom venlafaxine is prescribed should be informed about discontinuation symptoms, especially those who have a history of noncompliance. Monitor patients closely for discontinuation symptoms when venlafaxine is stopped—even if the patient is switched to another antidepressant. A gradual dosage reduction is recommended rather than abrupt termination or rapid dosage reduction. Immediately switching from venlafaxine to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) generally is not recommended, although it could alleviate some discontinuation symptoms2; cross-taper medication over 2 to 3 weeks.

Switching from venlafaxine to another SNRI, such as duloxetine, is less well studied. At venlafaxine dosages of <150 mg/d, an immediate switch to another SNRI of equivalent dosage generally is well-tolerated. For higher dosages, a gradual cross-taper is advised.2

Most patients tolerate a venlafaxine dosage reduction by 75 mg/d, at 1-week intervals. For patients who experience severe discontinuation symptoms with a minor dosage reduction, venlafaxine can be tapered over 10 months with approximately 1% dosage reduction every 3 days. Stahl3 recommends dissolving the tablet in 100 mL of juice, discarding 1 mL, and drinking the rest. After 3 days, 2 mL can be discarded, etc.

Another strategy to prevent discontinuation syndrome is to initiate fluoxetine—an SSRI with a long half-life—before taper; maintain fluoxetine dosage while venlafaxine is tapered; and then taper fluoxetine.

Managing discontinuation symptoms

If your patient experiences significant discontinuation symptoms, resume the last prescribed venlafaxine dosage, with a plan for a more gradual taper. Acute discontinuation syndrome also can be treated by initiating fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d; after symptoms resolve, fluoxetine can be tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Most antidepressants lead to adverse discontinuation symptoms when they are abruptly stopped or rapidly tapered. Antidepressants with a short half-life, such as paroxetine and venlafaxine, can cause significantly more severe discontinuation symptoms compared with antidepressants with a longer half-life.

One culprit in particular

Among serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), venlafaxine is notorious for severe discontinuation symptoms. Venlafaxine has a half-life of 3 to 7 hours, and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, possesses a half-life of 9 to 13 hours. Higher frequency of discontinuation symptoms is associated with the use of higher dosages of venlafaxine and longer duration of treatment.

Venlafaxine is available in immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) formulations. Venlafaxine XR has a slower release, extending the time to peak plasma concentration and, therefore, has once daily dosing and fewer side effects; however, it offers no substantial advantage over IR formulation in terms of diminished withdrawal effects. Desvenlafaxine also is marketed as an antidepressant and, although one can speculate that the drug would have a lower rate of discontinuation symptoms than venlafaxine, no evidence supports this hypothesis.

A range of venlafaxine discontinuation symptoms have been reported (Table).1

Preventing discontinuation symptoms

Patients for whom venlafaxine is prescribed should be informed about discontinuation symptoms, especially those who have a history of noncompliance. Monitor patients closely for discontinuation symptoms when venlafaxine is stopped—even if the patient is switched to another antidepressant. A gradual dosage reduction is recommended rather than abrupt termination or rapid dosage reduction. Immediately switching from venlafaxine to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) generally is not recommended, although it could alleviate some discontinuation symptoms2; cross-taper medication over 2 to 3 weeks.

Switching from venlafaxine to another SNRI, such as duloxetine, is less well studied. At venlafaxine dosages of <150 mg/d, an immediate switch to another SNRI of equivalent dosage generally is well-tolerated. For higher dosages, a gradual cross-taper is advised.2

Most patients tolerate a venlafaxine dosage reduction by 75 mg/d, at 1-week intervals. For patients who experience severe discontinuation symptoms with a minor dosage reduction, venlafaxine can be tapered over 10 months with approximately 1% dosage reduction every 3 days. Stahl3 recommends dissolving the tablet in 100 mL of juice, discarding 1 mL, and drinking the rest. After 3 days, 2 mL can be discarded, etc.

Another strategy to prevent discontinuation syndrome is to initiate fluoxetine—an SSRI with a long half-life—before taper; maintain fluoxetine dosage while venlafaxine is tapered; and then taper fluoxetine.

Managing discontinuation symptoms

If your patient experiences significant discontinuation symptoms, resume the last prescribed venlafaxine dosage, with a plan for a more gradual taper. Acute discontinuation syndrome also can be treated by initiating fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d; after symptoms resolve, fluoxetine can be tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Effexor (venlafaxine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012.

2. Hirsch M, Birnbaum RJ. Antidepressant medication in adults: switching and discontinuing medication. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/antidepressant-medicationin-adults-switching-and-discontinuing-medication. Updated January 16, 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

3. Stahl SM. Venlafaxine. In: Stahl SM. The prescriber’s guide (Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology). 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011:637-638.

1. Effexor (venlafaxine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012.

2. Hirsch M, Birnbaum RJ. Antidepressant medication in adults: switching and discontinuing medication. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/antidepressant-medicationin-adults-switching-and-discontinuing-medication. Updated January 16, 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

3. Stahl SM. Venlafaxine. In: Stahl SM. The prescriber’s guide (Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology). 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011:637-638.

Botulinum toxin for depression? An idea that’s raising some eyebrows

Psychiatry is experiencing a major paradigm shift.1 No longer is depression a disease of norepinephrine and serotonin deficiency. Today, we are exploring inflammation, methylation, epigenetics, and neuroplasticity as major players; we are using innovative treatment interventions such as ketamine, magnets, psilocin, anti-inflammatories, and even botulinum toxin.

In 2006, dermatologist Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, reported a case series of 10 depressed patients who were given a single course of botulinum toxin A (BTA, onabotulinum-toxinA) injections in the forehead.2 After 2 months, 9 out of the 10 patients were no longer depressed. The 10th patient, who reported improvement in symptoms but not remission, was the only patient with bipolar depression.

As a psychiatrist (M.M.) and a dermatologist (J.R.), we conducted a randomized controlled trial3 to challenge the difficult-to-swallow notion that a cosmetic intervention could help severely depressed patients. After reporting our positive findings and hearing numerous encouraging patient testimonials, we present a favorable review on the treatment of depression using BTA. We also present the top 10 questions we are asked at lectures about this novel treatment.

A deadly toxin used to treat medical conditions

Botulinum toxin is one of the deadliest substance known to man.4 It was named after the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which causes so-called floppy baby syndrome in infants who eat contaminated honey. Botulinum toxin prevents nerves from releasing acetylcholine, which causes muscle paralysis.

In the wrong hands, botulinum toxin can be exploited for chemical warfare.4 However, doctors are using it to treat >50 medical conditions, including migraine, cervical dystonia, strabismus, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, excessive sweating, muscle spasm, and now depression.5,6 In 2014, BTA was the top cosmetic treatment in the United States, with >3 million procedures performed, generating more than 1 billion dollars in revenue.7

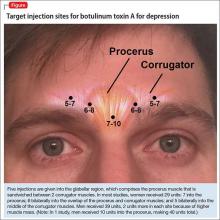

The most common site injected with BTA for cosmetic treatments is the glabellar region, which is the area directly above and in between the eyebrows (ie, the lower forehead). The glabella comprises 2 main muscles: the central procerus flanked by a pair of corrugators (Figure). When expressing fear, anger, sadness, or anguish, these muscles contract, causing the appearance of 2 vertical wrinkles, referred to as the “11s.” The wrinkles also can form the shape of an upside-down “U,” known as the omega sign.8 BTA prevents contraction of these muscles and therefore prevents the appearance of a furrowed brow. During cosmetic procedures, approximately 20 to 50 units of BTA are spread out over 5 glabellar injection sites.9 A similar technique is being used in studies of BTA for depression2,3,10,11 (Figure).

BTA for depression is new to the mental health world but, before psychiatrists caught on, dermatologists were aware that BTA could improve quality of life,12 reduce negative emotions,13 and increase feelings of well-being.14

The evidence

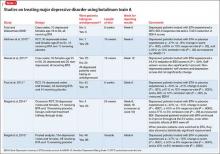

To date, there have been 2 case series,2,15 3 randomized control trials (RCTs),3,10,11 1 pooled analysis,16,17 and 1 meta-analysis18 looking at botulinum for depression (Table 1).2,10,11,15-17 In each trial, a single treatment of BTA (ie, 1 doctor’s visit; 29 to 40 units of BTA distributed into 5 glabellar injections sites), was the intervention studied.2

The first case series, by Finzi and Wasserman2 is described above. A second case series, published in 2013, describes 50 female patients, one-half depressed and one-half non-depressed, all of whom received 20 units of BTA into the glabella.15 At 12 weeks, depression scores in the depressed group had decreased by 54% (14.9 point drop on Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], P < .001) and self-esteem scores had increased significantly. In non-depressed participants, depression scores and self-esteem scores remained constant throughout the 12 weeks.

A pooled analysis reported results of 3 RCTs16,17 consisting of a total of 134 depressed patients, males and females age 18 to 65 who received BTA (n = 59) or placebo (n = 74) into the glabellar region. At the end of 6 weeks, BDI scores in the depressed group had decreased by 47.4% (14.3 points) compared with a 16.2% decrease (5.1 points) in the placebo group. This corresponds to a 52.5% vs 8.0% response rate and a 42.4% vs 8.0% remission rate, respectively (Table 1,1,2,10,11,15-17). There was no difference between the 2 groups in sex, age, depression severity, and number of antidepressants being taken. Females received 29 units and males received 10 to 11 units more to account for higher muscle mass (Figure).

Depression as measured by the physician-administered Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale showed similar reduction in overall scores (−45.7% vs −14.6%), response rates (54.2% vs 10.7%) and remission rates (30.5% vs 6.7%) with BTA.

Although these improvements in depression scores do not reach those seen with electroconvulsive therapy,19,20 they are comparable to placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants.21,22

Doesn’t this technique work because people who look better, feel better?

Aesthetic improvement alone is unlikely to explain the entire story. A recent study showed that improvement in wrinkle score did not correlate with improvement in mood.23 Furthermore, some patients in RCTs did not like the cosmetic effects of BTA but still reported feeling less depressed after treatment.10

How might it work?

Several theories about the mechanism of action have been proposed:

• The facial feedback hypothesis dates to Charles Darwin in 1872: Facial movements influence emotional states. Numerous studies have confirmed this. Strack et al24 found that patients asked to smile while reading comics found them to be funnier. Ekman et al25 found that imitating angry facial expressions made body temperature and heart rate rise. Dialectical behavioral therapy expert Marsha Linehan recognized the importance of modifying facial expressions (from grimacing to smiling) and posture (from clenched fists to open hands) when feeling distressed, because it is hard to feel “willful” when your “mind is going one way and your body is going another.”26 Accordingly, for a person who continuously “looks” depressed or distressed, reducing the anguished facial expression using botulinum toxin might diminish the entwined negative emotions.

• A more pleasant facial expression improves social interactions, which leads to improvement in self-esteem and mood. Social biologists argue that (1) we are attracted to those who have more pleasant facial expressions and (2) we steer clear of those who appear angry or depressed (a negative facial expression, such as a growling dog, is perceived as a threat). Therefore, anyone who looks depressed might have less rewarding interpersonal interactions, which can contribute to a poor mood.

On a similar note, mirror neurons are regions in the brain that are activated by witnessing another person’s emotional cues. When our mirror neurons light up, we can feel an observed experience, which is why we often feel nervous around anxious people, or cringe when we see others get hurt, or why we might prefer engaging with people who appear happier. It is possible that, after BTA injection, a person’s social connectivity is improved because of a more positive reciprocal firing of mirror neurons.

• BTA leads to direct and indirect neurochemical changes in the brain that can reduce depression. Functional MRI studies have shown that after glabellar BTA injections, the amygdala was less responsive to negative stimuli.27,28 For example, patients who were treated with BTA and then shown pictures of angry people had an attenuated amygdala response to the photos.

This is an important finding, especially for patients who have been traumatized. After a traumatic event, the amygdala “remembers” what happened, which is good, in some ways (it prevents us from getting into a similar dangerous situation), but bad in others (the traumatized amygdala may falsely perceive a non-threatening stimuli as threatening). A hypervigilant amygdala can lead to an out-of-proportion fear response, depression, and anxiety. Therefore, quelling an overactive amygdala with BTA could improve emotional dysregulation and posttraumatic disorders.

Many of our patients reported that, after BTA injection, “traumatic events didn’t feel as traumatizing,” as one said. The emotional pain and rumination that often follow a life stressor “does not overstay its welcome” and patients are able to “move on” more quickly.

It is unknown why the amygdala is quieted after BTA; researchers hypothesize that BTA suppresses facial feedback signals from the forehead branch of the trigeminal nerve to the brain. Another hypothesis is that BTA is directly transported by the trigeminal nerve into the brain and exerts central pharmacological effects on the amygdala.29 This theory has only been studied in rat models.30

When does it start working? How long does it last?

From what we know, BTA for depression could start working as early as 2 weeks and could last as long as 6 months. In one RCT, the earliest follow-up was 2 weeks,10 at which time the depressed patients had responded to botulinum toxin (P ≤ .05). In the other 2 controlled trials, the earliest follow-up was 3 weeks, at which time a more robust response was seen (P < .001). Aesthetically, BTA usually lasts 3 months. It is unclear how long the antidepressant effects last but, in the longest trial,3 depression symptoms continued to improve at 6 months, after cosmetic effects had worn off.

These findings raise a series of questions:

• Do mood effects outlast cosmetic effects? If so, why?

• Does botulinum toxin start to work sooner than 2 weeks?

• Will adherence improve if a patient has to be treated only every 6 months?

In our clinical experience, depressed patients who responded to BTA injection report a slow resurfacing of depressive symptoms 4 to 6 months after treatment, at which point they usually return for “maintenance treatment” (same dosing, same injection configuration).

Will psychiatrists administer the treatment?

Any physician or physician extender can, when properly trained, inject BTA. The question is: Do psychiatrists want to? Administrating botulinum toxin requires more labor and preparation than prescribing a drug (Table 2,31) and requires placing hands on patients. Depending on the type of psychiatric practice, this may be a “deal-breaker” for some providers, such as those in a psychoanalytic practice who might worry about boundaries.

As a basis for comparison, despite several indications for BTA for headache and neurologic conditions, few neurologists have added botulinum toxin to their practice. Dermatologists who are comfortable seeing psychiatric patients or family practitioners, who are already set up for injection procedures, could become custodians of this intervention.

Which patients are candidates for the treatment?

Patients with anxious or agitated depression might be ideal candidates for BTA injection. A recent study looked at predictors of response: Patients with a high agitation score (as measured on item 9 of the HAM-D) were more likely to respond, with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 56%, and an overall precision of 78%.32 So far, no other predictors of response have been clearly identified. Higher baseline wrinkle scores do not predict better response.23 Sex and age do not have any predictive value. The treatment appears to be equally effective in males and females; because only a handful of males have been treated (n = 14), however, these patients need to be studied further.

Is botulinum toxin better as monotherapy or augmentation strategy?

So far, it appears to be equally effective as monotherapy or augmentation strategy,16 but more studies are needed.

How expensive is it?

Estimates of patient cost include the cost of the product and the professional fee for injection. As a point of reference, for cosmetic purposes, depending on practice location, dermatologists charge $11 to $20 per unit of BTA. Therefore, 1 treatment of BTA for depression (29 to 40 units) can cost a patient $319 to $800.

When treating a patient with BTA for medical indications, such as tension headache, insurance often reimburses the physician for the BTA at cost (paid with a J code: J0585) and pay an injection fee (a procedure code) of $150 to $200. A recent analysis of cost-effectiveness estimated that BTA for depression would cost a patient $1,200 to $1,600 annually.33 Compared with the price of branded medications (eg, $500 to $2,000 annually)33 plus weekly psychotherapy (eg, $2,000 to $5,000 annually), BTA may be a cost-effective option for patients who do not respond to conventional treatments. Of course, for patients who tolerate and respond to generic medications or have a therapist who charges on a sliding scale, BTA is not the most cost-effective option.

What about injecting other areas of the face?

We’ve thought about it but haven’t tried it. There are several muscles around the mouth that allow us to smile and frown. BTA injections in the depressor anguli oris, a muscle around the mouth that is largely responsible for frowning, could treat depression. However, if the mechanism of action is via amygdala desensitization through the trigeminal nerve, treating mouth frown muscles might not work.

Is it safe?

BTA in the glabella has an exceptionally good safety profile.9,31,34 Adverse reactions, which include eyelid droop, pain, bruising, and redness at the injection site, are minor and temporary.9 In addition, BTA has few drug–drug interactions. The biggest complaint for most patients is discomfort upon injection, which often is described as feeling like “an ant bite.”

In the pooled analysis of RCTs, apart from local irritation immediately after injection, temporary headache was the only relevant, and possibly treatment-related, adverse event. Headache occurred in 13.6% (n = 8) of the BTA group and 9.3% (n = 7) of the placebo group (P = .44). Compared with antidepressants such as citalopram, where approximately 38.6% of patients report a moderate or severe side-effect burden,21 BTA is well tolerated.

Are other studies underway?

Larger studies are being conducted,35 mainly to confirm what pilot studies have shown. It would be interesting to discover other predictors of response and if different dosing and injection configurations could strengthen the response rate and extend the duration of effect.

Because of the cosmetic effects of BTA, further studies are needed to address the problem of blinding. In earlier studies, raters were blinded during appointments because patients wore surgical caps that covered their glabellar region.3,10 Patients did not know their treatment intervention, but 52% to 90% of patients guessed correctly.3,10,11 Although unblinding is a common problem in “blinded” trials in which some researchers have reported >75% of participants and raters guessed the intervention correctly,36 it is a particularly sensitive area in studies that involve a change in appearance because it is almost impossible to prevent someone from looking in a mirror.

Summing up

Botulinum toxin for depression is not ready for prime time. The FDA has not approved its use for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure as a treatment for depression. Patients who request BTA for depression must be informed that this use is off-label.

For now, we recommend psychotherapy or medication management, or both, for most patients with major depression. In addition, until larger studies are done, we recommend that patients who are interested in BTA for depression use it as an add-on to conventional treatment. However, if larger studies replicate the findings of the smaller studies we have described, botulinum toxin could become a novel therapeutic agent in the fight against depression.

Bottom Line

In pilot studies, botulinum toxin A (BTA) has shown efficacy in improving symptoms of depression. Although considered safe, BTA is not FDA-approved for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure for depression. Larger studies are underway to determine if this novel treatment can be introduced into practice.

Related Resources

• Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger THC. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al, eds. Practical psychodermatology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014:216-219.

• Botox for depression. www.botoxfordepression.com.

• Botox and depression. www.botoxanddepression.com.

Drug Brand Names

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Citalopram • Celexa

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for granting Dr. Magid a young investigator award and for continuing to invest in innovative research ideas. We thank Dr. Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, Axel Wollmer, MD, and Tillmann Krüger, MD, for their continued collaboration in this area of research.

Disclosures

In July 2011, Dr. Magid received a young investigator award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for her study on treating depression using botulinum toxin (Grant number 17648). In November 2012, after completion and as a result of the study on treating depression using botulinum toxin, Dr. Magid became a consultant with Allergan to discuss study findings. In September 2015, Dr. Magid became a speaker for IPSEN Innovation. Dr. Reichenberg is married to Dr. Magid. Dr. Reichenberg has no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

2. Finzi E, Wasserman E. Treatment of depression with botulinum toxin A: a case series. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(5):645-649; discussion 649-650.

3. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

4. Koussoulakos S. Botulinum neurotoxin: the ugly duckling. Eur Neurol. 2008;61(6):331-342.

5. Chen S. Clinical uses of botulinum neurotoxins: current indications, limitations and future developments. Toxins (Basel). 2012;4(10):913-939.

6. Bhidayasiri R, Truong DD. Expanding use of botulinum toxin. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235(1-1):1-9.

7. Cosmetic surgery national data bank statistics. American Society for Asethetic Plastic Surgery. http://www.surgery. org/sites/default/files/2014-Stats.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 30, 2015.

8. Shorter E. Darwin’s contribution to psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):473-474.

9. Winter L, Spiegel J. Botulinum toxin type-A in the treatment of glabellar lines. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;3:1-4.

10. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

11. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

12. Hexsel D, Brum C, Porto MD, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction of patients after full-face injections of abobotulinum toxin type A: a randomized, phase IV clinical trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(12):1363-1367.

13. Lewis MB, Bowler PJ. Botulinum toxin cosmetic therapy correlates with a more positive mood. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(1):24-26.

14. Sommer B, Zschocke I, Bergfeld D, et al. Satisfaction of patients after treatment with botulinum toxin for dynamic facial lines. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(5):456-460.

15. Hexsel D, Brum C, Siega C, et al. Evaluation of self‐esteem and depression symptoms in depressed and nondepressed subjects treated with onabotulinumtoxina for glabellar lines. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(7):1088-1096.

16. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Finzi E, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: update and meta-analysis from clinic trials. Paper presented at: XVI World Congress of Psychiatry; September 14-18, 2014; Madrid, Spain.

17. Magid M, Finzi E, Kruger TH, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(6):205-210.

18. Parsaik A, Mascarenhas S, Hashmi A, et al. Role of botulinum toxin in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. In press.

19. Scott AI, ed. The ECT handbook, 2nd ed. The third report of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Special Committee of ECT. London, United Kingdom: The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005.

20. Ren J, Li H, Palaniyappan L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation versus electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;51:181-189.

21. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al; STAR*D Study Team. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR* D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

22. Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, et al. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):572-579.

23. Reichenberg JS, Magid M, Keeling B. Botulinum toxin for depression: does the presence of rhytids predict response? Presented at: Texas Dermatology Society; May 2015; Bastrop, Texas.

24. Strack F, Martin LL, Stepper S. Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: a nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):768-777.

25. Ekman P, Levenson RW, Friesen WV. Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science. 1983;221(4616):1208-1210.

26. Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2014.

27. Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, et al. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion—new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537-542.

28. Kim MJ, Neta M, Davis FC, et al. Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception of emotional expressions: preliminary findings from an A-B-A design. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:11.

29. Mazzocchio R, Caleo M. More than at the neuromuscular synapse: actions of botulinum neurotoxin A in the central nervous system. Neuroscientist. 2015;21(1):44-61.

30. Antonucci F, Rossi C, Gianfranceschi L, et al. Long-distance retrograde effects of botulinum neurotoxin A. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3689-3696.

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Medication guide: botox. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/ucm176360.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed June 7, 2015.

32. Wollmer MA, Kalak N, Jung S, et al. Agitation predicts response of depression to botulinum toxin treatment in a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:36.

33. Beer K. Cost effectiveness of botulinum toxins for the treatment of depression: preliminary observations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):27-30.

34. Brin MF, Boodhoo TI, Pogoda JM, et al. Safety and tolerability of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of facial lines: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from global clinical registration studies in 1678 participants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(6):961-970.e1-11.

35. Botulinum toxin and depression. ClinicalTrials.gov. https:// clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=botulinum+toxin+and+ depression&Search=Search. Accessed June 1, 2015.

36. Rabkin JG, Markowitz JS, Stewart J, et al. How blind is blind? Assessment of patient and doctor medication guesses in a placebo-controlled trial of imipramine and phenelzine. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(1):75-86.

Psychiatry is experiencing a major paradigm shift.1 No longer is depression a disease of norepinephrine and serotonin deficiency. Today, we are exploring inflammation, methylation, epigenetics, and neuroplasticity as major players; we are using innovative treatment interventions such as ketamine, magnets, psilocin, anti-inflammatories, and even botulinum toxin.

In 2006, dermatologist Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, reported a case series of 10 depressed patients who were given a single course of botulinum toxin A (BTA, onabotulinum-toxinA) injections in the forehead.2 After 2 months, 9 out of the 10 patients were no longer depressed. The 10th patient, who reported improvement in symptoms but not remission, was the only patient with bipolar depression.

As a psychiatrist (M.M.) and a dermatologist (J.R.), we conducted a randomized controlled trial3 to challenge the difficult-to-swallow notion that a cosmetic intervention could help severely depressed patients. After reporting our positive findings and hearing numerous encouraging patient testimonials, we present a favorable review on the treatment of depression using BTA. We also present the top 10 questions we are asked at lectures about this novel treatment.

A deadly toxin used to treat medical conditions

Botulinum toxin is one of the deadliest substance known to man.4 It was named after the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which causes so-called floppy baby syndrome in infants who eat contaminated honey. Botulinum toxin prevents nerves from releasing acetylcholine, which causes muscle paralysis.

In the wrong hands, botulinum toxin can be exploited for chemical warfare.4 However, doctors are using it to treat >50 medical conditions, including migraine, cervical dystonia, strabismus, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, excessive sweating, muscle spasm, and now depression.5,6 In 2014, BTA was the top cosmetic treatment in the United States, with >3 million procedures performed, generating more than 1 billion dollars in revenue.7

The most common site injected with BTA for cosmetic treatments is the glabellar region, which is the area directly above and in between the eyebrows (ie, the lower forehead). The glabella comprises 2 main muscles: the central procerus flanked by a pair of corrugators (Figure). When expressing fear, anger, sadness, or anguish, these muscles contract, causing the appearance of 2 vertical wrinkles, referred to as the “11s.” The wrinkles also can form the shape of an upside-down “U,” known as the omega sign.8 BTA prevents contraction of these muscles and therefore prevents the appearance of a furrowed brow. During cosmetic procedures, approximately 20 to 50 units of BTA are spread out over 5 glabellar injection sites.9 A similar technique is being used in studies of BTA for depression2,3,10,11 (Figure).

BTA for depression is new to the mental health world but, before psychiatrists caught on, dermatologists were aware that BTA could improve quality of life,12 reduce negative emotions,13 and increase feelings of well-being.14

The evidence

To date, there have been 2 case series,2,15 3 randomized control trials (RCTs),3,10,11 1 pooled analysis,16,17 and 1 meta-analysis18 looking at botulinum for depression (Table 1).2,10,11,15-17 In each trial, a single treatment of BTA (ie, 1 doctor’s visit; 29 to 40 units of BTA distributed into 5 glabellar injections sites), was the intervention studied.2

The first case series, by Finzi and Wasserman2 is described above. A second case series, published in 2013, describes 50 female patients, one-half depressed and one-half non-depressed, all of whom received 20 units of BTA into the glabella.15 At 12 weeks, depression scores in the depressed group had decreased by 54% (14.9 point drop on Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], P < .001) and self-esteem scores had increased significantly. In non-depressed participants, depression scores and self-esteem scores remained constant throughout the 12 weeks.

A pooled analysis reported results of 3 RCTs16,17 consisting of a total of 134 depressed patients, males and females age 18 to 65 who received BTA (n = 59) or placebo (n = 74) into the glabellar region. At the end of 6 weeks, BDI scores in the depressed group had decreased by 47.4% (14.3 points) compared with a 16.2% decrease (5.1 points) in the placebo group. This corresponds to a 52.5% vs 8.0% response rate and a 42.4% vs 8.0% remission rate, respectively (Table 1,1,2,10,11,15-17). There was no difference between the 2 groups in sex, age, depression severity, and number of antidepressants being taken. Females received 29 units and males received 10 to 11 units more to account for higher muscle mass (Figure).

Depression as measured by the physician-administered Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale showed similar reduction in overall scores (−45.7% vs −14.6%), response rates (54.2% vs 10.7%) and remission rates (30.5% vs 6.7%) with BTA.

Although these improvements in depression scores do not reach those seen with electroconvulsive therapy,19,20 they are comparable to placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants.21,22

Doesn’t this technique work because people who look better, feel better?

Aesthetic improvement alone is unlikely to explain the entire story. A recent study showed that improvement in wrinkle score did not correlate with improvement in mood.23 Furthermore, some patients in RCTs did not like the cosmetic effects of BTA but still reported feeling less depressed after treatment.10

How might it work?

Several theories about the mechanism of action have been proposed:

• The facial feedback hypothesis dates to Charles Darwin in 1872: Facial movements influence emotional states. Numerous studies have confirmed this. Strack et al24 found that patients asked to smile while reading comics found them to be funnier. Ekman et al25 found that imitating angry facial expressions made body temperature and heart rate rise. Dialectical behavioral therapy expert Marsha Linehan recognized the importance of modifying facial expressions (from grimacing to smiling) and posture (from clenched fists to open hands) when feeling distressed, because it is hard to feel “willful” when your “mind is going one way and your body is going another.”26 Accordingly, for a person who continuously “looks” depressed or distressed, reducing the anguished facial expression using botulinum toxin might diminish the entwined negative emotions.

• A more pleasant facial expression improves social interactions, which leads to improvement in self-esteem and mood. Social biologists argue that (1) we are attracted to those who have more pleasant facial expressions and (2) we steer clear of those who appear angry or depressed (a negative facial expression, such as a growling dog, is perceived as a threat). Therefore, anyone who looks depressed might have less rewarding interpersonal interactions, which can contribute to a poor mood.

On a similar note, mirror neurons are regions in the brain that are activated by witnessing another person’s emotional cues. When our mirror neurons light up, we can feel an observed experience, which is why we often feel nervous around anxious people, or cringe when we see others get hurt, or why we might prefer engaging with people who appear happier. It is possible that, after BTA injection, a person’s social connectivity is improved because of a more positive reciprocal firing of mirror neurons.

• BTA leads to direct and indirect neurochemical changes in the brain that can reduce depression. Functional MRI studies have shown that after glabellar BTA injections, the amygdala was less responsive to negative stimuli.27,28 For example, patients who were treated with BTA and then shown pictures of angry people had an attenuated amygdala response to the photos.

This is an important finding, especially for patients who have been traumatized. After a traumatic event, the amygdala “remembers” what happened, which is good, in some ways (it prevents us from getting into a similar dangerous situation), but bad in others (the traumatized amygdala may falsely perceive a non-threatening stimuli as threatening). A hypervigilant amygdala can lead to an out-of-proportion fear response, depression, and anxiety. Therefore, quelling an overactive amygdala with BTA could improve emotional dysregulation and posttraumatic disorders.

Many of our patients reported that, after BTA injection, “traumatic events didn’t feel as traumatizing,” as one said. The emotional pain and rumination that often follow a life stressor “does not overstay its welcome” and patients are able to “move on” more quickly.

It is unknown why the amygdala is quieted after BTA; researchers hypothesize that BTA suppresses facial feedback signals from the forehead branch of the trigeminal nerve to the brain. Another hypothesis is that BTA is directly transported by the trigeminal nerve into the brain and exerts central pharmacological effects on the amygdala.29 This theory has only been studied in rat models.30

When does it start working? How long does it last?

From what we know, BTA for depression could start working as early as 2 weeks and could last as long as 6 months. In one RCT, the earliest follow-up was 2 weeks,10 at which time the depressed patients had responded to botulinum toxin (P ≤ .05). In the other 2 controlled trials, the earliest follow-up was 3 weeks, at which time a more robust response was seen (P < .001). Aesthetically, BTA usually lasts 3 months. It is unclear how long the antidepressant effects last but, in the longest trial,3 depression symptoms continued to improve at 6 months, after cosmetic effects had worn off.

These findings raise a series of questions:

• Do mood effects outlast cosmetic effects? If so, why?

• Does botulinum toxin start to work sooner than 2 weeks?

• Will adherence improve if a patient has to be treated only every 6 months?

In our clinical experience, depressed patients who responded to BTA injection report a slow resurfacing of depressive symptoms 4 to 6 months after treatment, at which point they usually return for “maintenance treatment” (same dosing, same injection configuration).

Will psychiatrists administer the treatment?

Any physician or physician extender can, when properly trained, inject BTA. The question is: Do psychiatrists want to? Administrating botulinum toxin requires more labor and preparation than prescribing a drug (Table 2,31) and requires placing hands on patients. Depending on the type of psychiatric practice, this may be a “deal-breaker” for some providers, such as those in a psychoanalytic practice who might worry about boundaries.

As a basis for comparison, despite several indications for BTA for headache and neurologic conditions, few neurologists have added botulinum toxin to their practice. Dermatologists who are comfortable seeing psychiatric patients or family practitioners, who are already set up for injection procedures, could become custodians of this intervention.

Which patients are candidates for the treatment?

Patients with anxious or agitated depression might be ideal candidates for BTA injection. A recent study looked at predictors of response: Patients with a high agitation score (as measured on item 9 of the HAM-D) were more likely to respond, with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 56%, and an overall precision of 78%.32 So far, no other predictors of response have been clearly identified. Higher baseline wrinkle scores do not predict better response.23 Sex and age do not have any predictive value. The treatment appears to be equally effective in males and females; because only a handful of males have been treated (n = 14), however, these patients need to be studied further.

Is botulinum toxin better as monotherapy or augmentation strategy?

So far, it appears to be equally effective as monotherapy or augmentation strategy,16 but more studies are needed.

How expensive is it?

Estimates of patient cost include the cost of the product and the professional fee for injection. As a point of reference, for cosmetic purposes, depending on practice location, dermatologists charge $11 to $20 per unit of BTA. Therefore, 1 treatment of BTA for depression (29 to 40 units) can cost a patient $319 to $800.

When treating a patient with BTA for medical indications, such as tension headache, insurance often reimburses the physician for the BTA at cost (paid with a J code: J0585) and pay an injection fee (a procedure code) of $150 to $200. A recent analysis of cost-effectiveness estimated that BTA for depression would cost a patient $1,200 to $1,600 annually.33 Compared with the price of branded medications (eg, $500 to $2,000 annually)33 plus weekly psychotherapy (eg, $2,000 to $5,000 annually), BTA may be a cost-effective option for patients who do not respond to conventional treatments. Of course, for patients who tolerate and respond to generic medications or have a therapist who charges on a sliding scale, BTA is not the most cost-effective option.

What about injecting other areas of the face?

We’ve thought about it but haven’t tried it. There are several muscles around the mouth that allow us to smile and frown. BTA injections in the depressor anguli oris, a muscle around the mouth that is largely responsible for frowning, could treat depression. However, if the mechanism of action is via amygdala desensitization through the trigeminal nerve, treating mouth frown muscles might not work.

Is it safe?

BTA in the glabella has an exceptionally good safety profile.9,31,34 Adverse reactions, which include eyelid droop, pain, bruising, and redness at the injection site, are minor and temporary.9 In addition, BTA has few drug–drug interactions. The biggest complaint for most patients is discomfort upon injection, which often is described as feeling like “an ant bite.”

In the pooled analysis of RCTs, apart from local irritation immediately after injection, temporary headache was the only relevant, and possibly treatment-related, adverse event. Headache occurred in 13.6% (n = 8) of the BTA group and 9.3% (n = 7) of the placebo group (P = .44). Compared with antidepressants such as citalopram, where approximately 38.6% of patients report a moderate or severe side-effect burden,21 BTA is well tolerated.

Are other studies underway?

Larger studies are being conducted,35 mainly to confirm what pilot studies have shown. It would be interesting to discover other predictors of response and if different dosing and injection configurations could strengthen the response rate and extend the duration of effect.

Because of the cosmetic effects of BTA, further studies are needed to address the problem of blinding. In earlier studies, raters were blinded during appointments because patients wore surgical caps that covered their glabellar region.3,10 Patients did not know their treatment intervention, but 52% to 90% of patients guessed correctly.3,10,11 Although unblinding is a common problem in “blinded” trials in which some researchers have reported >75% of participants and raters guessed the intervention correctly,36 it is a particularly sensitive area in studies that involve a change in appearance because it is almost impossible to prevent someone from looking in a mirror.

Summing up

Botulinum toxin for depression is not ready for prime time. The FDA has not approved its use for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure as a treatment for depression. Patients who request BTA for depression must be informed that this use is off-label.

For now, we recommend psychotherapy or medication management, or both, for most patients with major depression. In addition, until larger studies are done, we recommend that patients who are interested in BTA for depression use it as an add-on to conventional treatment. However, if larger studies replicate the findings of the smaller studies we have described, botulinum toxin could become a novel therapeutic agent in the fight against depression.

Bottom Line

In pilot studies, botulinum toxin A (BTA) has shown efficacy in improving symptoms of depression. Although considered safe, BTA is not FDA-approved for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure for depression. Larger studies are underway to determine if this novel treatment can be introduced into practice.

Related Resources

• Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger THC. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al, eds. Practical psychodermatology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014:216-219.

• Botox for depression. www.botoxfordepression.com.

• Botox and depression. www.botoxanddepression.com.

Drug Brand Names

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Citalopram • Celexa

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for granting Dr. Magid a young investigator award and for continuing to invest in innovative research ideas. We thank Dr. Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, Axel Wollmer, MD, and Tillmann Krüger, MD, for their continued collaboration in this area of research.

Disclosures

In July 2011, Dr. Magid received a young investigator award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for her study on treating depression using botulinum toxin (Grant number 17648). In November 2012, after completion and as a result of the study on treating depression using botulinum toxin, Dr. Magid became a consultant with Allergan to discuss study findings. In September 2015, Dr. Magid became a speaker for IPSEN Innovation. Dr. Reichenberg is married to Dr. Magid. Dr. Reichenberg has no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Psychiatry is experiencing a major paradigm shift.1 No longer is depression a disease of norepinephrine and serotonin deficiency. Today, we are exploring inflammation, methylation, epigenetics, and neuroplasticity as major players; we are using innovative treatment interventions such as ketamine, magnets, psilocin, anti-inflammatories, and even botulinum toxin.

In 2006, dermatologist Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, reported a case series of 10 depressed patients who were given a single course of botulinum toxin A (BTA, onabotulinum-toxinA) injections in the forehead.2 After 2 months, 9 out of the 10 patients were no longer depressed. The 10th patient, who reported improvement in symptoms but not remission, was the only patient with bipolar depression.

As a psychiatrist (M.M.) and a dermatologist (J.R.), we conducted a randomized controlled trial3 to challenge the difficult-to-swallow notion that a cosmetic intervention could help severely depressed patients. After reporting our positive findings and hearing numerous encouraging patient testimonials, we present a favorable review on the treatment of depression using BTA. We also present the top 10 questions we are asked at lectures about this novel treatment.

A deadly toxin used to treat medical conditions

Botulinum toxin is one of the deadliest substance known to man.4 It was named after the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which causes so-called floppy baby syndrome in infants who eat contaminated honey. Botulinum toxin prevents nerves from releasing acetylcholine, which causes muscle paralysis.

In the wrong hands, botulinum toxin can be exploited for chemical warfare.4 However, doctors are using it to treat >50 medical conditions, including migraine, cervical dystonia, strabismus, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, excessive sweating, muscle spasm, and now depression.5,6 In 2014, BTA was the top cosmetic treatment in the United States, with >3 million procedures performed, generating more than 1 billion dollars in revenue.7

The most common site injected with BTA for cosmetic treatments is the glabellar region, which is the area directly above and in between the eyebrows (ie, the lower forehead). The glabella comprises 2 main muscles: the central procerus flanked by a pair of corrugators (Figure). When expressing fear, anger, sadness, or anguish, these muscles contract, causing the appearance of 2 vertical wrinkles, referred to as the “11s.” The wrinkles also can form the shape of an upside-down “U,” known as the omega sign.8 BTA prevents contraction of these muscles and therefore prevents the appearance of a furrowed brow. During cosmetic procedures, approximately 20 to 50 units of BTA are spread out over 5 glabellar injection sites.9 A similar technique is being used in studies of BTA for depression2,3,10,11 (Figure).

BTA for depression is new to the mental health world but, before psychiatrists caught on, dermatologists were aware that BTA could improve quality of life,12 reduce negative emotions,13 and increase feelings of well-being.14

The evidence

To date, there have been 2 case series,2,15 3 randomized control trials (RCTs),3,10,11 1 pooled analysis,16,17 and 1 meta-analysis18 looking at botulinum for depression (Table 1).2,10,11,15-17 In each trial, a single treatment of BTA (ie, 1 doctor’s visit; 29 to 40 units of BTA distributed into 5 glabellar injections sites), was the intervention studied.2

The first case series, by Finzi and Wasserman2 is described above. A second case series, published in 2013, describes 50 female patients, one-half depressed and one-half non-depressed, all of whom received 20 units of BTA into the glabella.15 At 12 weeks, depression scores in the depressed group had decreased by 54% (14.9 point drop on Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], P < .001) and self-esteem scores had increased significantly. In non-depressed participants, depression scores and self-esteem scores remained constant throughout the 12 weeks.

A pooled analysis reported results of 3 RCTs16,17 consisting of a total of 134 depressed patients, males and females age 18 to 65 who received BTA (n = 59) or placebo (n = 74) into the glabellar region. At the end of 6 weeks, BDI scores in the depressed group had decreased by 47.4% (14.3 points) compared with a 16.2% decrease (5.1 points) in the placebo group. This corresponds to a 52.5% vs 8.0% response rate and a 42.4% vs 8.0% remission rate, respectively (Table 1,1,2,10,11,15-17). There was no difference between the 2 groups in sex, age, depression severity, and number of antidepressants being taken. Females received 29 units and males received 10 to 11 units more to account for higher muscle mass (Figure).

Depression as measured by the physician-administered Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale showed similar reduction in overall scores (−45.7% vs −14.6%), response rates (54.2% vs 10.7%) and remission rates (30.5% vs 6.7%) with BTA.

Although these improvements in depression scores do not reach those seen with electroconvulsive therapy,19,20 they are comparable to placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants.21,22

Doesn’t this technique work because people who look better, feel better?

Aesthetic improvement alone is unlikely to explain the entire story. A recent study showed that improvement in wrinkle score did not correlate with improvement in mood.23 Furthermore, some patients in RCTs did not like the cosmetic effects of BTA but still reported feeling less depressed after treatment.10

How might it work?

Several theories about the mechanism of action have been proposed:

• The facial feedback hypothesis dates to Charles Darwin in 1872: Facial movements influence emotional states. Numerous studies have confirmed this. Strack et al24 found that patients asked to smile while reading comics found them to be funnier. Ekman et al25 found that imitating angry facial expressions made body temperature and heart rate rise. Dialectical behavioral therapy expert Marsha Linehan recognized the importance of modifying facial expressions (from grimacing to smiling) and posture (from clenched fists to open hands) when feeling distressed, because it is hard to feel “willful” when your “mind is going one way and your body is going another.”26 Accordingly, for a person who continuously “looks” depressed or distressed, reducing the anguished facial expression using botulinum toxin might diminish the entwined negative emotions.

• A more pleasant facial expression improves social interactions, which leads to improvement in self-esteem and mood. Social biologists argue that (1) we are attracted to those who have more pleasant facial expressions and (2) we steer clear of those who appear angry or depressed (a negative facial expression, such as a growling dog, is perceived as a threat). Therefore, anyone who looks depressed might have less rewarding interpersonal interactions, which can contribute to a poor mood.

On a similar note, mirror neurons are regions in the brain that are activated by witnessing another person’s emotional cues. When our mirror neurons light up, we can feel an observed experience, which is why we often feel nervous around anxious people, or cringe when we see others get hurt, or why we might prefer engaging with people who appear happier. It is possible that, after BTA injection, a person’s social connectivity is improved because of a more positive reciprocal firing of mirror neurons.

• BTA leads to direct and indirect neurochemical changes in the brain that can reduce depression. Functional MRI studies have shown that after glabellar BTA injections, the amygdala was less responsive to negative stimuli.27,28 For example, patients who were treated with BTA and then shown pictures of angry people had an attenuated amygdala response to the photos.

This is an important finding, especially for patients who have been traumatized. After a traumatic event, the amygdala “remembers” what happened, which is good, in some ways (it prevents us from getting into a similar dangerous situation), but bad in others (the traumatized amygdala may falsely perceive a non-threatening stimuli as threatening). A hypervigilant amygdala can lead to an out-of-proportion fear response, depression, and anxiety. Therefore, quelling an overactive amygdala with BTA could improve emotional dysregulation and posttraumatic disorders.

Many of our patients reported that, after BTA injection, “traumatic events didn’t feel as traumatizing,” as one said. The emotional pain and rumination that often follow a life stressor “does not overstay its welcome” and patients are able to “move on” more quickly.

It is unknown why the amygdala is quieted after BTA; researchers hypothesize that BTA suppresses facial feedback signals from the forehead branch of the trigeminal nerve to the brain. Another hypothesis is that BTA is directly transported by the trigeminal nerve into the brain and exerts central pharmacological effects on the amygdala.29 This theory has only been studied in rat models.30

When does it start working? How long does it last?