User login

Atypical hyperplasia of the breast: Cancer risk-reduction strategies

Of the approximately 1 million benign breast biopsies obtained annually from US women, some 10% yield a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia, microscopically classified as ductal or lobular. Atypical hyperplasia represents a “proliferation of dysplastic, monotonous epithelial-cell populations that include clonal subpopulations. In models of breast carcinogenesis, atypical hyperplasia occupies a transitional zone between benign and malignant disease,” write Hartmann and colleagues, the authors of a recent special report in the New England Journal of Medicine.1

Long-term follow-up studies have found atypical hyperplasia to confer a relative risk for breast cancer of 4.0. Although these findings are well established, the cumulative absolute risk for breast cancer conferred by a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia only recently has been described. Hartmann and colleagues note that it approaches 30% over 25 years.1

Recommendations for clinical practice

The authors of this special report do a service to women and their clinicians by pointing out the high long-term risk of malignancy faced by women with atypical hyperplasia of the breast. They also make a number of important recommendations for practice:

- When counseling patients with this diagnosis, it is preferable to use cumulative incidence data because the most commonly used breast cancer risk-prediction models do not accurately estimate the risk for breast malignancy in women with atypical hyperplasia.

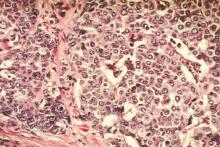

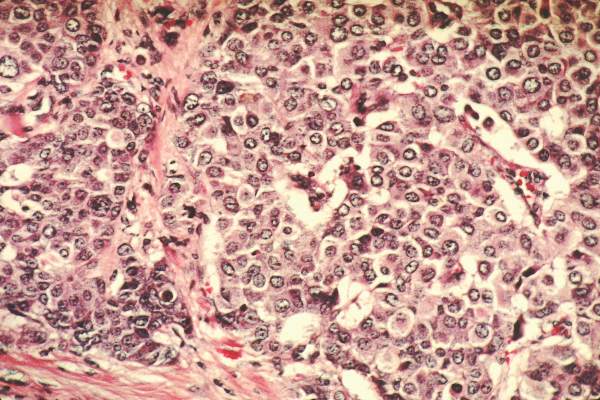

- When atypical hyperplasia of the breast is found after core-needle biopsy (FIGURE), surgical excision of the site is recommended to ensure that cancer was not missed as a result of a sampling error. This recommendation derives from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.2 “In the case of atypical ductal hyperplasia, the frequency of finding breast cancer (‘upgrading’) with surgical excision is 15% to 30% or even higher, despite the use of large-gauge (9- or 11-gauge) core-needle biopsy with vacuum-assisted devices,” Hartmann and colleagues note.

- Women with atypical hyperplasia clearly should receive annual mammographic screening. Although screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may play a role in assessing women with this diagnosis, no prospective trial data have evaluated its utility in this setting. Screening MRI’s low specificity may lead to many unnecessary biopsies with benign findings. This in turn can generate so much anxiety that women may pursue prophylactic bilateral mastectomy to avoid a lifetime of stress related to breast cancer concerns. Women with atypical hyperplasia should be included in future trials of new breast imaging technologies.

- As with other high-risk women, those who have been diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia are well served by being referred to and followed by a physician with special expertise in breast disease who can arrange appropriate screening and follow-up. (See the sidebar, “Here’s how I counsel women with atypical hyperplasia about their management options.”)

- Women with a history of atypical hyperplasia who are considering initiation of systemic menopausal hormone therapyshould be aware that they have a higher baseline risk for invasive breast cancer than other women. Accordingly, the absolute risk of invasive breast cancer associated with use of estrogen-progestin menopausal hormone therapy (EPT) is also likely substantially higher than in average-risk women. Therefore, among women with a history of atypical hyperplasia of the breast who have an intact uterus, use of EPT should be minimized.

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators such as tamoxifen and raloxifene should be more widely used by women with atypical hyperplasia because of their ability to reduce breast cancer risk. Aromatase inhibitors also should be prescribed more widely in this population. (Again, see the sidebar, “Here’s how I counsel women with atypical hyperplasia about their management options.”)

When chemoprevention may be in order

If the 5-year risk of breast cancer by the Gail model is greater than 1.7%, and the patient is older than 35 years, I counsel her that she qualifies for chemoprevention with prophylactic endocrine therapy with the selective estrogen receptor modulators tamoxifen or raloxifene, or the aromatase inhibitor exemestane.1 The choice of drug depends on her menopausal status, bone mineral density, and presence of other comorbidities.

Although tamoxifen is indicated for breast cancer chemoprophylaxis in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, raloxifene is only approved for risk reduction in postmenopausal women. Likewise, aromatase inhibitors (which have shown high efficacy in chemoprophylaxis but are not FDA-approved for this indication) should be used only in postmenopausal women.

Who might gain the most from tamoxifen? The tamoxifen risk/benefit calculator2,3 can be used to weigh the benefit of breast cancer prevention against the risk of the drug’s adverse effects. Life-threatening adverse effects can include thromboembolic events and endometrial malignancy.2,3 Based on recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force, women with a 5-year risk of breast cancer equal to or greater than 3% are most likely to benefit from 5 years of prophylactic endocrine therapy.2 In women who are posthysterectomy, the benefit/risk ratio associated with tamoxifen use is higher.

When is annual MRI appropriate?

The decision to perform annual screening breast MRI should be based on a strong family history rather than strictly a biopsy diagnosis of atypia. The Claus and BRCAPRO models are more appropriate here, as they use only family history information and do not incorporate biopsy results. There are no data to support the use of screening breast MRI in patients with atypia who do not have a strong family history or a deleterious genetic mutation.4,5

Patients with proliferative breast disease tend to have a substantial amount of vague glandular enhancement on breast MRI. Screening MRI in patients with atypia is more likely to lead to frequent false-positive results and unnecessary benign biopsies and cause significant patient anxiety. Without endocrine blockade, breast MRI in this population tends to be nondiagnostic, with a very low yield for breast cancer diagnosis (positive predictive value, 20%).6 Repeated false-positive results of screening MRI in this population can cause patient anxiety, culminating in unnecessary mastectomies. If the Claus or BRCAPRO models yield a lifetime risk for breast cancer above 20%, or the breasts are extremely dense, I discuss with my patient the possibility of adding screening breast MRI.

When ordering breast MRI, it’s important to be aware that this imaging requires gadolinium intravenous contrast, which is excreted through the kidney and requires adequate renal function. This contrast agent can lead to nephrosclerosis in patients with renal insufficiency. In patients with hypertension, diabetes, age over 60, or prior chemotherapy, a recent serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine level is required. Therefore, the decision to perform annual breast MRI for the rest of a woman’s life should not be taken lightly.

As a part of comprehensive risk assessment, it is important to identify patients who qualify for genetic testing. The addition of screening breast MRI should be heavily dependent on family history, results of BRCA testing and, possibly, mammographic breast density.

Make sure your patient knows that her condition places her at elevated risk, and refer her to a breast specialist

It’s also important to involve the patient in decision making to help ensure that she is proactive and adherent when choosing the best way to manage her risk. The key is to educate her about the importance of atypia.

Many women are told that their follow-up surgical excision was “benign,” and the subject of “atypia” or risk reduction is never addressed. It’s important that the right diagnostic terminology and coding are documented in the medical record so that the finding of atypia is not downgraded to a “benign breast biopsy.”

Finally, due to the complexities of this issue, evaluation by a qualified breast specialist or high-risk cancer program is recommended.

—Laila Samiian, MD

References

1. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Bonanni B, et al. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators in prevention of breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2013;381(9880):1827–1834.

2. Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2327–2333.

3. Gail MH, Costantino JP, Bryant J, et al. Weighing the risks and benefits of tamoxifen treatment for preventing breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(21):1829–1846.

4. Port ER, Park A, Borgen PI, Morris E, Montgomery LL. Results of MRI screening for breast cancer in high-risk patients with LCIS and atypical hyperplasia. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(3):1051–1057.

5. Hartmann LC, Degnim AC, Santen RJ, Dupont WD, Ghosh K. Special report: atypical hyperplasia of the breast—risk assessment and management options. N Eng J Med. 2015;372(1):78–89.

6. Schwartz T, Cyr A, Margenthaler J. Screening breast magnetic resonance imaging in women with atypia or lobular carcinoma in situ. J Surg Res. 2015;193(2):519–522.

Most women will not develop breast malignancy

As Hartmann and colleagues point out, all is not dire once a woman is diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia of the breast. In most of these women, breast cancer will not develop—and if it does develop, it may occur at an age when mortality from other causes is more likely than from breast cancer. In this respect, women with atypical hyperplasia of the breast are different from carriers of BRCA mutations. Although women with atypical hyperplasia as well as mutation carriers are both at high lifetime risk for breast cancer, breast malignancies occur at an earlier age in mutation carriers. Accordingly, as the authors of this special report advise, in general, a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia should not be considered an indication for risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Hartman LC, Degnim AC Santen RJ, Dupont WD, Ghosh K. Special report: atypical hyperplasia of the breast—risk assessment and management options. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):78–89.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines: breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 1. 2014. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#detection. Accessed March 24, 2015.

Of the approximately 1 million benign breast biopsies obtained annually from US women, some 10% yield a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia, microscopically classified as ductal or lobular. Atypical hyperplasia represents a “proliferation of dysplastic, monotonous epithelial-cell populations that include clonal subpopulations. In models of breast carcinogenesis, atypical hyperplasia occupies a transitional zone between benign and malignant disease,” write Hartmann and colleagues, the authors of a recent special report in the New England Journal of Medicine.1

Long-term follow-up studies have found atypical hyperplasia to confer a relative risk for breast cancer of 4.0. Although these findings are well established, the cumulative absolute risk for breast cancer conferred by a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia only recently has been described. Hartmann and colleagues note that it approaches 30% over 25 years.1

Recommendations for clinical practice

The authors of this special report do a service to women and their clinicians by pointing out the high long-term risk of malignancy faced by women with atypical hyperplasia of the breast. They also make a number of important recommendations for practice:

- When counseling patients with this diagnosis, it is preferable to use cumulative incidence data because the most commonly used breast cancer risk-prediction models do not accurately estimate the risk for breast malignancy in women with atypical hyperplasia.

- When atypical hyperplasia of the breast is found after core-needle biopsy (FIGURE), surgical excision of the site is recommended to ensure that cancer was not missed as a result of a sampling error. This recommendation derives from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.2 “In the case of atypical ductal hyperplasia, the frequency of finding breast cancer (‘upgrading’) with surgical excision is 15% to 30% or even higher, despite the use of large-gauge (9- or 11-gauge) core-needle biopsy with vacuum-assisted devices,” Hartmann and colleagues note.

- Women with atypical hyperplasia clearly should receive annual mammographic screening. Although screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may play a role in assessing women with this diagnosis, no prospective trial data have evaluated its utility in this setting. Screening MRI’s low specificity may lead to many unnecessary biopsies with benign findings. This in turn can generate so much anxiety that women may pursue prophylactic bilateral mastectomy to avoid a lifetime of stress related to breast cancer concerns. Women with atypical hyperplasia should be included in future trials of new breast imaging technologies.

- As with other high-risk women, those who have been diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia are well served by being referred to and followed by a physician with special expertise in breast disease who can arrange appropriate screening and follow-up. (See the sidebar, “Here’s how I counsel women with atypical hyperplasia about their management options.”)

- Women with a history of atypical hyperplasia who are considering initiation of systemic menopausal hormone therapyshould be aware that they have a higher baseline risk for invasive breast cancer than other women. Accordingly, the absolute risk of invasive breast cancer associated with use of estrogen-progestin menopausal hormone therapy (EPT) is also likely substantially higher than in average-risk women. Therefore, among women with a history of atypical hyperplasia of the breast who have an intact uterus, use of EPT should be minimized.

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators such as tamoxifen and raloxifene should be more widely used by women with atypical hyperplasia because of their ability to reduce breast cancer risk. Aromatase inhibitors also should be prescribed more widely in this population. (Again, see the sidebar, “Here’s how I counsel women with atypical hyperplasia about their management options.”)

When chemoprevention may be in order

If the 5-year risk of breast cancer by the Gail model is greater than 1.7%, and the patient is older than 35 years, I counsel her that she qualifies for chemoprevention with prophylactic endocrine therapy with the selective estrogen receptor modulators tamoxifen or raloxifene, or the aromatase inhibitor exemestane.1 The choice of drug depends on her menopausal status, bone mineral density, and presence of other comorbidities.

Although tamoxifen is indicated for breast cancer chemoprophylaxis in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, raloxifene is only approved for risk reduction in postmenopausal women. Likewise, aromatase inhibitors (which have shown high efficacy in chemoprophylaxis but are not FDA-approved for this indication) should be used only in postmenopausal women.

Who might gain the most from tamoxifen? The tamoxifen risk/benefit calculator2,3 can be used to weigh the benefit of breast cancer prevention against the risk of the drug’s adverse effects. Life-threatening adverse effects can include thromboembolic events and endometrial malignancy.2,3 Based on recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force, women with a 5-year risk of breast cancer equal to or greater than 3% are most likely to benefit from 5 years of prophylactic endocrine therapy.2 In women who are posthysterectomy, the benefit/risk ratio associated with tamoxifen use is higher.

When is annual MRI appropriate?

The decision to perform annual screening breast MRI should be based on a strong family history rather than strictly a biopsy diagnosis of atypia. The Claus and BRCAPRO models are more appropriate here, as they use only family history information and do not incorporate biopsy results. There are no data to support the use of screening breast MRI in patients with atypia who do not have a strong family history or a deleterious genetic mutation.4,5

Patients with proliferative breast disease tend to have a substantial amount of vague glandular enhancement on breast MRI. Screening MRI in patients with atypia is more likely to lead to frequent false-positive results and unnecessary benign biopsies and cause significant patient anxiety. Without endocrine blockade, breast MRI in this population tends to be nondiagnostic, with a very low yield for breast cancer diagnosis (positive predictive value, 20%).6 Repeated false-positive results of screening MRI in this population can cause patient anxiety, culminating in unnecessary mastectomies. If the Claus or BRCAPRO models yield a lifetime risk for breast cancer above 20%, or the breasts are extremely dense, I discuss with my patient the possibility of adding screening breast MRI.

When ordering breast MRI, it’s important to be aware that this imaging requires gadolinium intravenous contrast, which is excreted through the kidney and requires adequate renal function. This contrast agent can lead to nephrosclerosis in patients with renal insufficiency. In patients with hypertension, diabetes, age over 60, or prior chemotherapy, a recent serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine level is required. Therefore, the decision to perform annual breast MRI for the rest of a woman’s life should not be taken lightly.

As a part of comprehensive risk assessment, it is important to identify patients who qualify for genetic testing. The addition of screening breast MRI should be heavily dependent on family history, results of BRCA testing and, possibly, mammographic breast density.

Make sure your patient knows that her condition places her at elevated risk, and refer her to a breast specialist

It’s also important to involve the patient in decision making to help ensure that she is proactive and adherent when choosing the best way to manage her risk. The key is to educate her about the importance of atypia.

Many women are told that their follow-up surgical excision was “benign,” and the subject of “atypia” or risk reduction is never addressed. It’s important that the right diagnostic terminology and coding are documented in the medical record so that the finding of atypia is not downgraded to a “benign breast biopsy.”

Finally, due to the complexities of this issue, evaluation by a qualified breast specialist or high-risk cancer program is recommended.

—Laila Samiian, MD

References

1. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Bonanni B, et al. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators in prevention of breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2013;381(9880):1827–1834.

2. Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2327–2333.

3. Gail MH, Costantino JP, Bryant J, et al. Weighing the risks and benefits of tamoxifen treatment for preventing breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(21):1829–1846.

4. Port ER, Park A, Borgen PI, Morris E, Montgomery LL. Results of MRI screening for breast cancer in high-risk patients with LCIS and atypical hyperplasia. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(3):1051–1057.

5. Hartmann LC, Degnim AC, Santen RJ, Dupont WD, Ghosh K. Special report: atypical hyperplasia of the breast—risk assessment and management options. N Eng J Med. 2015;372(1):78–89.

6. Schwartz T, Cyr A, Margenthaler J. Screening breast magnetic resonance imaging in women with atypia or lobular carcinoma in situ. J Surg Res. 2015;193(2):519–522.

Most women will not develop breast malignancy

As Hartmann and colleagues point out, all is not dire once a woman is diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia of the breast. In most of these women, breast cancer will not develop—and if it does develop, it may occur at an age when mortality from other causes is more likely than from breast cancer. In this respect, women with atypical hyperplasia of the breast are different from carriers of BRCA mutations. Although women with atypical hyperplasia as well as mutation carriers are both at high lifetime risk for breast cancer, breast malignancies occur at an earlier age in mutation carriers. Accordingly, as the authors of this special report advise, in general, a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia should not be considered an indication for risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Of the approximately 1 million benign breast biopsies obtained annually from US women, some 10% yield a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia, microscopically classified as ductal or lobular. Atypical hyperplasia represents a “proliferation of dysplastic, monotonous epithelial-cell populations that include clonal subpopulations. In models of breast carcinogenesis, atypical hyperplasia occupies a transitional zone between benign and malignant disease,” write Hartmann and colleagues, the authors of a recent special report in the New England Journal of Medicine.1

Long-term follow-up studies have found atypical hyperplasia to confer a relative risk for breast cancer of 4.0. Although these findings are well established, the cumulative absolute risk for breast cancer conferred by a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia only recently has been described. Hartmann and colleagues note that it approaches 30% over 25 years.1

Recommendations for clinical practice

The authors of this special report do a service to women and their clinicians by pointing out the high long-term risk of malignancy faced by women with atypical hyperplasia of the breast. They also make a number of important recommendations for practice:

- When counseling patients with this diagnosis, it is preferable to use cumulative incidence data because the most commonly used breast cancer risk-prediction models do not accurately estimate the risk for breast malignancy in women with atypical hyperplasia.

- When atypical hyperplasia of the breast is found after core-needle biopsy (FIGURE), surgical excision of the site is recommended to ensure that cancer was not missed as a result of a sampling error. This recommendation derives from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.2 “In the case of atypical ductal hyperplasia, the frequency of finding breast cancer (‘upgrading’) with surgical excision is 15% to 30% or even higher, despite the use of large-gauge (9- or 11-gauge) core-needle biopsy with vacuum-assisted devices,” Hartmann and colleagues note.

- Women with atypical hyperplasia clearly should receive annual mammographic screening. Although screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may play a role in assessing women with this diagnosis, no prospective trial data have evaluated its utility in this setting. Screening MRI’s low specificity may lead to many unnecessary biopsies with benign findings. This in turn can generate so much anxiety that women may pursue prophylactic bilateral mastectomy to avoid a lifetime of stress related to breast cancer concerns. Women with atypical hyperplasia should be included in future trials of new breast imaging technologies.

- As with other high-risk women, those who have been diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia are well served by being referred to and followed by a physician with special expertise in breast disease who can arrange appropriate screening and follow-up. (See the sidebar, “Here’s how I counsel women with atypical hyperplasia about their management options.”)

- Women with a history of atypical hyperplasia who are considering initiation of systemic menopausal hormone therapyshould be aware that they have a higher baseline risk for invasive breast cancer than other women. Accordingly, the absolute risk of invasive breast cancer associated with use of estrogen-progestin menopausal hormone therapy (EPT) is also likely substantially higher than in average-risk women. Therefore, among women with a history of atypical hyperplasia of the breast who have an intact uterus, use of EPT should be minimized.

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators such as tamoxifen and raloxifene should be more widely used by women with atypical hyperplasia because of their ability to reduce breast cancer risk. Aromatase inhibitors also should be prescribed more widely in this population. (Again, see the sidebar, “Here’s how I counsel women with atypical hyperplasia about their management options.”)

When chemoprevention may be in order

If the 5-year risk of breast cancer by the Gail model is greater than 1.7%, and the patient is older than 35 years, I counsel her that she qualifies for chemoprevention with prophylactic endocrine therapy with the selective estrogen receptor modulators tamoxifen or raloxifene, or the aromatase inhibitor exemestane.1 The choice of drug depends on her menopausal status, bone mineral density, and presence of other comorbidities.

Although tamoxifen is indicated for breast cancer chemoprophylaxis in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, raloxifene is only approved for risk reduction in postmenopausal women. Likewise, aromatase inhibitors (which have shown high efficacy in chemoprophylaxis but are not FDA-approved for this indication) should be used only in postmenopausal women.

Who might gain the most from tamoxifen? The tamoxifen risk/benefit calculator2,3 can be used to weigh the benefit of breast cancer prevention against the risk of the drug’s adverse effects. Life-threatening adverse effects can include thromboembolic events and endometrial malignancy.2,3 Based on recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force, women with a 5-year risk of breast cancer equal to or greater than 3% are most likely to benefit from 5 years of prophylactic endocrine therapy.2 In women who are posthysterectomy, the benefit/risk ratio associated with tamoxifen use is higher.

When is annual MRI appropriate?

The decision to perform annual screening breast MRI should be based on a strong family history rather than strictly a biopsy diagnosis of atypia. The Claus and BRCAPRO models are more appropriate here, as they use only family history information and do not incorporate biopsy results. There are no data to support the use of screening breast MRI in patients with atypia who do not have a strong family history or a deleterious genetic mutation.4,5

Patients with proliferative breast disease tend to have a substantial amount of vague glandular enhancement on breast MRI. Screening MRI in patients with atypia is more likely to lead to frequent false-positive results and unnecessary benign biopsies and cause significant patient anxiety. Without endocrine blockade, breast MRI in this population tends to be nondiagnostic, with a very low yield for breast cancer diagnosis (positive predictive value, 20%).6 Repeated false-positive results of screening MRI in this population can cause patient anxiety, culminating in unnecessary mastectomies. If the Claus or BRCAPRO models yield a lifetime risk for breast cancer above 20%, or the breasts are extremely dense, I discuss with my patient the possibility of adding screening breast MRI.

When ordering breast MRI, it’s important to be aware that this imaging requires gadolinium intravenous contrast, which is excreted through the kidney and requires adequate renal function. This contrast agent can lead to nephrosclerosis in patients with renal insufficiency. In patients with hypertension, diabetes, age over 60, or prior chemotherapy, a recent serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine level is required. Therefore, the decision to perform annual breast MRI for the rest of a woman’s life should not be taken lightly.

As a part of comprehensive risk assessment, it is important to identify patients who qualify for genetic testing. The addition of screening breast MRI should be heavily dependent on family history, results of BRCA testing and, possibly, mammographic breast density.

Make sure your patient knows that her condition places her at elevated risk, and refer her to a breast specialist

It’s also important to involve the patient in decision making to help ensure that she is proactive and adherent when choosing the best way to manage her risk. The key is to educate her about the importance of atypia.

Many women are told that their follow-up surgical excision was “benign,” and the subject of “atypia” or risk reduction is never addressed. It’s important that the right diagnostic terminology and coding are documented in the medical record so that the finding of atypia is not downgraded to a “benign breast biopsy.”

Finally, due to the complexities of this issue, evaluation by a qualified breast specialist or high-risk cancer program is recommended.

—Laila Samiian, MD

References

1. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Bonanni B, et al. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators in prevention of breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2013;381(9880):1827–1834.

2. Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2327–2333.

3. Gail MH, Costantino JP, Bryant J, et al. Weighing the risks and benefits of tamoxifen treatment for preventing breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(21):1829–1846.

4. Port ER, Park A, Borgen PI, Morris E, Montgomery LL. Results of MRI screening for breast cancer in high-risk patients with LCIS and atypical hyperplasia. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(3):1051–1057.

5. Hartmann LC, Degnim AC, Santen RJ, Dupont WD, Ghosh K. Special report: atypical hyperplasia of the breast—risk assessment and management options. N Eng J Med. 2015;372(1):78–89.

6. Schwartz T, Cyr A, Margenthaler J. Screening breast magnetic resonance imaging in women with atypia or lobular carcinoma in situ. J Surg Res. 2015;193(2):519–522.

Most women will not develop breast malignancy

As Hartmann and colleagues point out, all is not dire once a woman is diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia of the breast. In most of these women, breast cancer will not develop—and if it does develop, it may occur at an age when mortality from other causes is more likely than from breast cancer. In this respect, women with atypical hyperplasia of the breast are different from carriers of BRCA mutations. Although women with atypical hyperplasia as well as mutation carriers are both at high lifetime risk for breast cancer, breast malignancies occur at an earlier age in mutation carriers. Accordingly, as the authors of this special report advise, in general, a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia should not be considered an indication for risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Hartman LC, Degnim AC Santen RJ, Dupont WD, Ghosh K. Special report: atypical hyperplasia of the breast—risk assessment and management options. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):78–89.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines: breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 1. 2014. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#detection. Accessed March 24, 2015.

1. Hartman LC, Degnim AC Santen RJ, Dupont WD, Ghosh K. Special report: atypical hyperplasia of the breast—risk assessment and management options. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):78–89.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines: breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 1. 2014. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#detection. Accessed March 24, 2015.

In this Article

- Dr. Samiian: How I counsel patients about their management options

- Mammography shows microcalcifications

Insurance, location, income drive breast cancer surgery choices

The rates of breast-conserving surgery have increased over the last 2 decades among women with early-stage breast cancers in the United States, but disparities persist, based on an analysis of data from the National Cancer Data Base.

The rate of breast-conserving surgery has risen from approximately 54% in 1998 to 60% in 2011, but this rate may have been affected by “technical advances and changes in societal norms [that] include genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation, advances in reconstruction techniques, breast magnetic resonance imaging, and increased patient interest in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy,” Dr. Meeghan Lautner and her colleagues at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Care Center, Houston, wrote.

“Among the most encouraging findings from our analysis is the considerable improvement of disparities based on facility type and the options afforded to older populations … however, insurance, income, and travel distance to treatment facilities persist as key barriers to [breast-conserving therapy] use,” the researchers said.

Their analysis of a cohort of 727,927 women, published online June 17 in JAMA Surgery, showed that women with early breast cancer were less likely to receive breast-conserving surgery if they had a low educational level, public or no health insurance, and low income.

Women aged 52-61 years were 14% more likely to be treated with breast-conserving surgery, compared with younger women. White race, fewer comorbidities, and living closer to a treatment facility were all positively associated with being treated with breast-conserving surgery.

Those in southern regions of the United States were significantly less likely to receive breast-conserving surgery, compared with those in the Northeast. The researchers said their data suggest the lower rates are because of the greater travel distances to treatment facilities in the South.

Women with no insurance were 25% less likely than those with private insurance to have breast-conserving therapy (JAMA Surgery 2015 June 17 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1102]).

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

Optimal breast-conserving surgery for most lumpectomy-eligible patients requires a commitment to whole-breast radiation, which also requires access to a radiation oncologist and specialized treatment facility. This is an often insurmountable barrier for patients who lack transportation, have job or family responsibilities, or who live a considerable distance from a radiation facility.

Document

|

Dr. Lisa A. Newman |

Socioeconomically disadvantaged patients are typically the ones who face these obstacles, and these burdens of financial deprivation are disproportionately faced by minority racial/ethnic groups and rural communities.

Tragically, disadvantage will continue to breed more disadvantage.

Dr. Lisa A. Newman is director of the Breast Care Center at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Care Center, Ann Arbor, Mich. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Surgery 2015 June 17 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1114]). Dr. Newman declared no conflicts of interest.

Optimal breast-conserving surgery for most lumpectomy-eligible patients requires a commitment to whole-breast radiation, which also requires access to a radiation oncologist and specialized treatment facility. This is an often insurmountable barrier for patients who lack transportation, have job or family responsibilities, or who live a considerable distance from a radiation facility.

Document

|

Dr. Lisa A. Newman |

Socioeconomically disadvantaged patients are typically the ones who face these obstacles, and these burdens of financial deprivation are disproportionately faced by minority racial/ethnic groups and rural communities.

Tragically, disadvantage will continue to breed more disadvantage.

Dr. Lisa A. Newman is director of the Breast Care Center at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Care Center, Ann Arbor, Mich. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Surgery 2015 June 17 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1114]). Dr. Newman declared no conflicts of interest.

Optimal breast-conserving surgery for most lumpectomy-eligible patients requires a commitment to whole-breast radiation, which also requires access to a radiation oncologist and specialized treatment facility. This is an often insurmountable barrier for patients who lack transportation, have job or family responsibilities, or who live a considerable distance from a radiation facility.

Document

|

Dr. Lisa A. Newman |

Socioeconomically disadvantaged patients are typically the ones who face these obstacles, and these burdens of financial deprivation are disproportionately faced by minority racial/ethnic groups and rural communities.

Tragically, disadvantage will continue to breed more disadvantage.

Dr. Lisa A. Newman is director of the Breast Care Center at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Care Center, Ann Arbor, Mich. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Surgery 2015 June 17 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1114]). Dr. Newman declared no conflicts of interest.

The rates of breast-conserving surgery have increased over the last 2 decades among women with early-stage breast cancers in the United States, but disparities persist, based on an analysis of data from the National Cancer Data Base.

The rate of breast-conserving surgery has risen from approximately 54% in 1998 to 60% in 2011, but this rate may have been affected by “technical advances and changes in societal norms [that] include genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation, advances in reconstruction techniques, breast magnetic resonance imaging, and increased patient interest in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy,” Dr. Meeghan Lautner and her colleagues at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Care Center, Houston, wrote.

“Among the most encouraging findings from our analysis is the considerable improvement of disparities based on facility type and the options afforded to older populations … however, insurance, income, and travel distance to treatment facilities persist as key barriers to [breast-conserving therapy] use,” the researchers said.

Their analysis of a cohort of 727,927 women, published online June 17 in JAMA Surgery, showed that women with early breast cancer were less likely to receive breast-conserving surgery if they had a low educational level, public or no health insurance, and low income.

Women aged 52-61 years were 14% more likely to be treated with breast-conserving surgery, compared with younger women. White race, fewer comorbidities, and living closer to a treatment facility were all positively associated with being treated with breast-conserving surgery.

Those in southern regions of the United States were significantly less likely to receive breast-conserving surgery, compared with those in the Northeast. The researchers said their data suggest the lower rates are because of the greater travel distances to treatment facilities in the South.

Women with no insurance were 25% less likely than those with private insurance to have breast-conserving therapy (JAMA Surgery 2015 June 17 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1102]).

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

The rates of breast-conserving surgery have increased over the last 2 decades among women with early-stage breast cancers in the United States, but disparities persist, based on an analysis of data from the National Cancer Data Base.

The rate of breast-conserving surgery has risen from approximately 54% in 1998 to 60% in 2011, but this rate may have been affected by “technical advances and changes in societal norms [that] include genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation, advances in reconstruction techniques, breast magnetic resonance imaging, and increased patient interest in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy,” Dr. Meeghan Lautner and her colleagues at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Care Center, Houston, wrote.

“Among the most encouraging findings from our analysis is the considerable improvement of disparities based on facility type and the options afforded to older populations … however, insurance, income, and travel distance to treatment facilities persist as key barriers to [breast-conserving therapy] use,” the researchers said.

Their analysis of a cohort of 727,927 women, published online June 17 in JAMA Surgery, showed that women with early breast cancer were less likely to receive breast-conserving surgery if they had a low educational level, public or no health insurance, and low income.

Women aged 52-61 years were 14% more likely to be treated with breast-conserving surgery, compared with younger women. White race, fewer comorbidities, and living closer to a treatment facility were all positively associated with being treated with breast-conserving surgery.

Those in southern regions of the United States were significantly less likely to receive breast-conserving surgery, compared with those in the Northeast. The researchers said their data suggest the lower rates are because of the greater travel distances to treatment facilities in the South.

Women with no insurance were 25% less likely than those with private insurance to have breast-conserving therapy (JAMA Surgery 2015 June 17 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1102]).

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Insurance status, income, and travel distance to treatment facilities are associated with the likelihood of having breast-conserving surgery.

Major finding: Women with no health insurance were 25% less likely than those with private insurance to receive breast-conserving surgery.

Data source: Analysis of data from 727,927 women in the National Cancer Data Base.

Disclosures: The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

ASCO: HR-deficient breast cancers more likely to respond to carboplatin

CHICAGO – Homologous recombination (HR) deficiency is a biomarker for benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), suggest data from the GeparSixto trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Roughly two-thirds of women were found to have HR-deficient tumors, impairing their ability to repair DNA and thereby rendering them susceptible to DNA-damaging agents. These women had more than double the odds of a pathologic complete response (pCR).

“HR deficiency in triple-negative breast cancer appears to be an independent predictor of high pCR rates to the chemotherapies that were given in this study,” summarized Dr. Gunter von Minckwitz on behalf of the German Breast Group and Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynakologische Onkologie-B (AGO-B) study group.

However, the findings were somewhat inconsistent. Additionally, although the highest pCR rate, at about 65%, was seen in women who had HR-deficient tumors and received carboplatin, women whose tumors were nondeficient also had some benefit from addition of this agent.

“This is why these data have to be confirmed by other studies, for example, the same measurements are currently ongoing in the CALGB 40603 study,” commented Dr. von Minckwitz, a senior physician at the University Women’s Hospital in Frankfurt. “And finally, they have to be set into the context with survival data that we expect at the end of 2015 or beginning of 2016.”

Invited discussant Dr. Pamela N. Munster, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, noted, “Homologous recombination deficiency mediated through the host or tumor predicts for high responses to chemotherapy and platinum salts in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer.” However, “the role of carboplatin and its optimal setting remains complex.”

She asked about the prevailing clinical practice regarding this agent’s use. “Based on your presentation and your work, what’s the landscape in Europe on the incorporation of carboplatin in the neoadjuvant therapy in triple-negative breast cancer or a subselect group?”

“We made a survey in our group half a year ago, and all members said that they are using carboplatin in triple-negative disease when they get neoadjuvant treatment,” Dr. von Minckwitz replied. “I’m not sure if this was 100% of patients, but I believe it was a more general quote, and this is in concordance with our AGO guideline, which allows the use of carboplatin in general in triple-negative [breast cancer]. It still says in patients with germline mutations, there is a somewhat stronger recommendation to use it, but it’s of course not a must.”

Session attendee Dr. Rebecca Dent of the National Cancer Centre Singapore and the University of Toronto asked whether oncologists should begin clinically applying HR deficiency for patient selection.

“I don’t think that currently these data or the sample size is sufficient to support clinical use tomorrow. … We have to wait for a confirmative study,” Dr. von Minckwitz replied.

Dr. Munster, the discussant, agreed, saying, “I think the HRD percentage is actually quite high in [this] set, so the test may not be as robust as we like to see. So I think part of it is refinement of biomarkers has to be the focus of what we do in the next 10 years.”

Previous results of the randomized phase 2/3 GeparSixto trial have shown that adding carboplatin to a neoadjuvant chemotherapy backbone (paclitaxel, liposomal doxorubicin, and bevacizumab) improves the pCR rate in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, but at the cost of added toxicity (Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:747-56). “Therefore it is of importance to better define the group of patients that might have a higher benefit from the addition of carboplatin,” Dr. von Minckwitz explained.

“We know from previous studies that tumors with a decreased DNA repair capacity, for example, due to a mutation of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are expected to have a higher sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents like platinum compounds. A more extensive way to measure DNA repair capacity is now possible using the HRD assay,” he noted.

The investigators assessed tumor HR deficiency among the 315 trial participants with triple-negative breast cancer. Overall, 70.5% had tumors that were HR deficient (meaning they had a high HRD score or a tumor BRCA mutation).

In the entire cohort, women with HR-deficient tumors were more likely to have a pCR, defined as absence of invasive residual disease in the breast or nodes (ypT0/is ypN0), than peers with HR-nondeficient tumors (55.9% vs. 29.8%). In multivariate analysis, HR deficiency independently predicted pCR (odds ratio, 2.51; P = .009).

Adding carboplatin improved the pCR rate significantly in women who had HR-deficient tumors (from 45.2% to 64.9%, P = .025) but also somewhat in women who had HR-nondeficient tumors (from 20.0% and 40.7%, P = .146). And there was no significant interaction between HR deficiency and carboplatin benefit.

In further analyses, carboplatin had a significant benefit in patients with a high HRD score but intact tumor BRCA, but not in patients with mutated tumor BRCA.

Findings differed slightly when the investigators repeated analyses but instead used a stricter definition of pCR that calls for absence of both invasive and noninvasive (ductal carcinoma in situ) residual disease in the breast and nodes (ypT0 ypN0), according to Dr. von Minckwitz.

Given that the majority of HR-deficient tumors did not have a BRCA mutation, the investigators plan to assess other drivers of HR deficiency, he said.

Dr. von Minckwitz disclosed employment, leadership, and stock ownership relationships with GBG Forschungs GmbH and research funding to his institution by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. The trial was funded by Teva, Roche Pharma AG, and GlaxoSmithKline.

CHICAGO – Homologous recombination (HR) deficiency is a biomarker for benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), suggest data from the GeparSixto trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Roughly two-thirds of women were found to have HR-deficient tumors, impairing their ability to repair DNA and thereby rendering them susceptible to DNA-damaging agents. These women had more than double the odds of a pathologic complete response (pCR).

“HR deficiency in triple-negative breast cancer appears to be an independent predictor of high pCR rates to the chemotherapies that were given in this study,” summarized Dr. Gunter von Minckwitz on behalf of the German Breast Group and Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynakologische Onkologie-B (AGO-B) study group.

However, the findings were somewhat inconsistent. Additionally, although the highest pCR rate, at about 65%, was seen in women who had HR-deficient tumors and received carboplatin, women whose tumors were nondeficient also had some benefit from addition of this agent.

“This is why these data have to be confirmed by other studies, for example, the same measurements are currently ongoing in the CALGB 40603 study,” commented Dr. von Minckwitz, a senior physician at the University Women’s Hospital in Frankfurt. “And finally, they have to be set into the context with survival data that we expect at the end of 2015 or beginning of 2016.”

Invited discussant Dr. Pamela N. Munster, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, noted, “Homologous recombination deficiency mediated through the host or tumor predicts for high responses to chemotherapy and platinum salts in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer.” However, “the role of carboplatin and its optimal setting remains complex.”

She asked about the prevailing clinical practice regarding this agent’s use. “Based on your presentation and your work, what’s the landscape in Europe on the incorporation of carboplatin in the neoadjuvant therapy in triple-negative breast cancer or a subselect group?”

“We made a survey in our group half a year ago, and all members said that they are using carboplatin in triple-negative disease when they get neoadjuvant treatment,” Dr. von Minckwitz replied. “I’m not sure if this was 100% of patients, but I believe it was a more general quote, and this is in concordance with our AGO guideline, which allows the use of carboplatin in general in triple-negative [breast cancer]. It still says in patients with germline mutations, there is a somewhat stronger recommendation to use it, but it’s of course not a must.”

Session attendee Dr. Rebecca Dent of the National Cancer Centre Singapore and the University of Toronto asked whether oncologists should begin clinically applying HR deficiency for patient selection.

“I don’t think that currently these data or the sample size is sufficient to support clinical use tomorrow. … We have to wait for a confirmative study,” Dr. von Minckwitz replied.

Dr. Munster, the discussant, agreed, saying, “I think the HRD percentage is actually quite high in [this] set, so the test may not be as robust as we like to see. So I think part of it is refinement of biomarkers has to be the focus of what we do in the next 10 years.”

Previous results of the randomized phase 2/3 GeparSixto trial have shown that adding carboplatin to a neoadjuvant chemotherapy backbone (paclitaxel, liposomal doxorubicin, and bevacizumab) improves the pCR rate in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, but at the cost of added toxicity (Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:747-56). “Therefore it is of importance to better define the group of patients that might have a higher benefit from the addition of carboplatin,” Dr. von Minckwitz explained.

“We know from previous studies that tumors with a decreased DNA repair capacity, for example, due to a mutation of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are expected to have a higher sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents like platinum compounds. A more extensive way to measure DNA repair capacity is now possible using the HRD assay,” he noted.

The investigators assessed tumor HR deficiency among the 315 trial participants with triple-negative breast cancer. Overall, 70.5% had tumors that were HR deficient (meaning they had a high HRD score or a tumor BRCA mutation).

In the entire cohort, women with HR-deficient tumors were more likely to have a pCR, defined as absence of invasive residual disease in the breast or nodes (ypT0/is ypN0), than peers with HR-nondeficient tumors (55.9% vs. 29.8%). In multivariate analysis, HR deficiency independently predicted pCR (odds ratio, 2.51; P = .009).

Adding carboplatin improved the pCR rate significantly in women who had HR-deficient tumors (from 45.2% to 64.9%, P = .025) but also somewhat in women who had HR-nondeficient tumors (from 20.0% and 40.7%, P = .146). And there was no significant interaction between HR deficiency and carboplatin benefit.

In further analyses, carboplatin had a significant benefit in patients with a high HRD score but intact tumor BRCA, but not in patients with mutated tumor BRCA.

Findings differed slightly when the investigators repeated analyses but instead used a stricter definition of pCR that calls for absence of both invasive and noninvasive (ductal carcinoma in situ) residual disease in the breast and nodes (ypT0 ypN0), according to Dr. von Minckwitz.

Given that the majority of HR-deficient tumors did not have a BRCA mutation, the investigators plan to assess other drivers of HR deficiency, he said.

Dr. von Minckwitz disclosed employment, leadership, and stock ownership relationships with GBG Forschungs GmbH and research funding to his institution by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. The trial was funded by Teva, Roche Pharma AG, and GlaxoSmithKline.

CHICAGO – Homologous recombination (HR) deficiency is a biomarker for benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), suggest data from the GeparSixto trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Roughly two-thirds of women were found to have HR-deficient tumors, impairing their ability to repair DNA and thereby rendering them susceptible to DNA-damaging agents. These women had more than double the odds of a pathologic complete response (pCR).

“HR deficiency in triple-negative breast cancer appears to be an independent predictor of high pCR rates to the chemotherapies that were given in this study,” summarized Dr. Gunter von Minckwitz on behalf of the German Breast Group and Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynakologische Onkologie-B (AGO-B) study group.

However, the findings were somewhat inconsistent. Additionally, although the highest pCR rate, at about 65%, was seen in women who had HR-deficient tumors and received carboplatin, women whose tumors were nondeficient also had some benefit from addition of this agent.

“This is why these data have to be confirmed by other studies, for example, the same measurements are currently ongoing in the CALGB 40603 study,” commented Dr. von Minckwitz, a senior physician at the University Women’s Hospital in Frankfurt. “And finally, they have to be set into the context with survival data that we expect at the end of 2015 or beginning of 2016.”

Invited discussant Dr. Pamela N. Munster, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, noted, “Homologous recombination deficiency mediated through the host or tumor predicts for high responses to chemotherapy and platinum salts in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer.” However, “the role of carboplatin and its optimal setting remains complex.”

She asked about the prevailing clinical practice regarding this agent’s use. “Based on your presentation and your work, what’s the landscape in Europe on the incorporation of carboplatin in the neoadjuvant therapy in triple-negative breast cancer or a subselect group?”

“We made a survey in our group half a year ago, and all members said that they are using carboplatin in triple-negative disease when they get neoadjuvant treatment,” Dr. von Minckwitz replied. “I’m not sure if this was 100% of patients, but I believe it was a more general quote, and this is in concordance with our AGO guideline, which allows the use of carboplatin in general in triple-negative [breast cancer]. It still says in patients with germline mutations, there is a somewhat stronger recommendation to use it, but it’s of course not a must.”

Session attendee Dr. Rebecca Dent of the National Cancer Centre Singapore and the University of Toronto asked whether oncologists should begin clinically applying HR deficiency for patient selection.

“I don’t think that currently these data or the sample size is sufficient to support clinical use tomorrow. … We have to wait for a confirmative study,” Dr. von Minckwitz replied.

Dr. Munster, the discussant, agreed, saying, “I think the HRD percentage is actually quite high in [this] set, so the test may not be as robust as we like to see. So I think part of it is refinement of biomarkers has to be the focus of what we do in the next 10 years.”

Previous results of the randomized phase 2/3 GeparSixto trial have shown that adding carboplatin to a neoadjuvant chemotherapy backbone (paclitaxel, liposomal doxorubicin, and bevacizumab) improves the pCR rate in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, but at the cost of added toxicity (Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:747-56). “Therefore it is of importance to better define the group of patients that might have a higher benefit from the addition of carboplatin,” Dr. von Minckwitz explained.

“We know from previous studies that tumors with a decreased DNA repair capacity, for example, due to a mutation of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are expected to have a higher sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents like platinum compounds. A more extensive way to measure DNA repair capacity is now possible using the HRD assay,” he noted.

The investigators assessed tumor HR deficiency among the 315 trial participants with triple-negative breast cancer. Overall, 70.5% had tumors that were HR deficient (meaning they had a high HRD score or a tumor BRCA mutation).

In the entire cohort, women with HR-deficient tumors were more likely to have a pCR, defined as absence of invasive residual disease in the breast or nodes (ypT0/is ypN0), than peers with HR-nondeficient tumors (55.9% vs. 29.8%). In multivariate analysis, HR deficiency independently predicted pCR (odds ratio, 2.51; P = .009).

Adding carboplatin improved the pCR rate significantly in women who had HR-deficient tumors (from 45.2% to 64.9%, P = .025) but also somewhat in women who had HR-nondeficient tumors (from 20.0% and 40.7%, P = .146). And there was no significant interaction between HR deficiency and carboplatin benefit.

In further analyses, carboplatin had a significant benefit in patients with a high HRD score but intact tumor BRCA, but not in patients with mutated tumor BRCA.

Findings differed slightly when the investigators repeated analyses but instead used a stricter definition of pCR that calls for absence of both invasive and noninvasive (ductal carcinoma in situ) residual disease in the breast and nodes (ypT0 ypN0), according to Dr. von Minckwitz.

Given that the majority of HR-deficient tumors did not have a BRCA mutation, the investigators plan to assess other drivers of HR deficiency, he said.

Dr. von Minckwitz disclosed employment, leadership, and stock ownership relationships with GBG Forschungs GmbH and research funding to his institution by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. The trial was funded by Teva, Roche Pharma AG, and GlaxoSmithKline.

AT THE 2015 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: HR deficiency is a biomarker for benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with TNBC.

Major finding: Women with HR-deficient tumors had 2.51-fold higher multivariate odds of pathologic complete response.

Data source: An analysis of 315 women with TNBC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in a randomized trial.

Disclosures: Dr. von Minckwitz disclosed employment, leadership, and stock ownership relationships with GBG Forschungs GmbH and research funding to his institution by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. The trial was funded by Teva, Roche Pharma AG, and GlaxoSmithKline.

VIDEO: Consider cost in anastrozole vs. tamoxifen for DCIS

CHICAGO – Anastrozole may top tamoxifen in reducing the risk of disease recurrence in postmenopausal ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), particularly in younger women, but which drug holds a cost advantage?

“How much do you want to pay in dollars or in side effects to achieve the extra benefit is an individual decision that a woman has to make with her physician,” said Dr. Richard Margolese, professor of surgical oncology at Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Dr. Margolese discussed the cost and side effect considerations that could determine a decision between anastrozole and tamoxifen.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Anastrozole may top tamoxifen in reducing the risk of disease recurrence in postmenopausal ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), particularly in younger women, but which drug holds a cost advantage?

“How much do you want to pay in dollars or in side effects to achieve the extra benefit is an individual decision that a woman has to make with her physician,” said Dr. Richard Margolese, professor of surgical oncology at Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Dr. Margolese discussed the cost and side effect considerations that could determine a decision between anastrozole and tamoxifen.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Anastrozole may top tamoxifen in reducing the risk of disease recurrence in postmenopausal ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), particularly in younger women, but which drug holds a cost advantage?

“How much do you want to pay in dollars or in side effects to achieve the extra benefit is an individual decision that a woman has to make with her physician,” said Dr. Richard Margolese, professor of surgical oncology at Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Dr. Margolese discussed the cost and side effect considerations that could determine a decision between anastrozole and tamoxifen.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE 2015 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Obesity boosts postmenopausal breast cancer risk

Women who are overweight and obese have a significantly higher risk of invasive breast cancer after menopause compared with normal-weight women, according to secondary analysis of data from the Women’s Health Initiative.

An analysis of data from 67,142 postmenopausal women aged 50-79 years found that women with a body mass index greater than 35 had a 58% increased risk of invasive breast cancer, compared with women with a BMI lower than 25. Obese women with a BMI of greater than 35 were also at increased risk for estrogen- and progesterone-receptor–positive breast cancer compared to normal-weight women (hazard ratio, 1.86), but they were not at increased risk for hormone receptor–negative breast cancer.

This group also had a twofold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with a larger tumor, and significantly higher risk of having positive lymph nodes, regional and/or distant stage, and also of dying after breast cancer, according to an article published June 11 in JAMA Oncology.

“Well-designed clinical trials are needed to definitively test whether weight loss and body composition changes in overweight and obese women or obesity prevention in women of normal weight will reduce breast cancer risk,” wrote Marian L. Neuhouser, Ph.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, and her colleagues (JAMA Oncol. 2015. June 11 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol. 2015.1546]).

The Women’s Health Initiative programs are supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health. One of the researchers disclosed having financial relationships with Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Genetech, and Amgen. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

This article makes an important contribution in extending and refining our understanding of one particular risk associated with overweight and obesity; namely the increase in postmenopausal, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

The researchers also made the frustrating observation that weight loss is not protective, which challenges the notion that patients who are overweight or obese should lose weight to reduce their cancer risk. The study highlights the need for clinical trials to explore whether weight loss or body composition changes in overweight and obesity can reduce breast cancer risk.

Dr. Clifford A. Hudis is from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and Dr. Andrew Dannenberg is from the Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. These comments are adapted from an editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2015 June 11 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol. 2015.1547]). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

This article makes an important contribution in extending and refining our understanding of one particular risk associated with overweight and obesity; namely the increase in postmenopausal, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

The researchers also made the frustrating observation that weight loss is not protective, which challenges the notion that patients who are overweight or obese should lose weight to reduce their cancer risk. The study highlights the need for clinical trials to explore whether weight loss or body composition changes in overweight and obesity can reduce breast cancer risk.

Dr. Clifford A. Hudis is from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and Dr. Andrew Dannenberg is from the Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. These comments are adapted from an editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2015 June 11 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol. 2015.1547]). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

This article makes an important contribution in extending and refining our understanding of one particular risk associated with overweight and obesity; namely the increase in postmenopausal, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

The researchers also made the frustrating observation that weight loss is not protective, which challenges the notion that patients who are overweight or obese should lose weight to reduce their cancer risk. The study highlights the need for clinical trials to explore whether weight loss or body composition changes in overweight and obesity can reduce breast cancer risk.

Dr. Clifford A. Hudis is from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and Dr. Andrew Dannenberg is from the Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. These comments are adapted from an editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2015 June 11 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol. 2015.1547]). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Women who are overweight and obese have a significantly higher risk of invasive breast cancer after menopause compared with normal-weight women, according to secondary analysis of data from the Women’s Health Initiative.

An analysis of data from 67,142 postmenopausal women aged 50-79 years found that women with a body mass index greater than 35 had a 58% increased risk of invasive breast cancer, compared with women with a BMI lower than 25. Obese women with a BMI of greater than 35 were also at increased risk for estrogen- and progesterone-receptor–positive breast cancer compared to normal-weight women (hazard ratio, 1.86), but they were not at increased risk for hormone receptor–negative breast cancer.

This group also had a twofold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with a larger tumor, and significantly higher risk of having positive lymph nodes, regional and/or distant stage, and also of dying after breast cancer, according to an article published June 11 in JAMA Oncology.

“Well-designed clinical trials are needed to definitively test whether weight loss and body composition changes in overweight and obese women or obesity prevention in women of normal weight will reduce breast cancer risk,” wrote Marian L. Neuhouser, Ph.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, and her colleagues (JAMA Oncol. 2015. June 11 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol. 2015.1546]).

The Women’s Health Initiative programs are supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health. One of the researchers disclosed having financial relationships with Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Genetech, and Amgen. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Women who are overweight and obese have a significantly higher risk of invasive breast cancer after menopause compared with normal-weight women, according to secondary analysis of data from the Women’s Health Initiative.

An analysis of data from 67,142 postmenopausal women aged 50-79 years found that women with a body mass index greater than 35 had a 58% increased risk of invasive breast cancer, compared with women with a BMI lower than 25. Obese women with a BMI of greater than 35 were also at increased risk for estrogen- and progesterone-receptor–positive breast cancer compared to normal-weight women (hazard ratio, 1.86), but they were not at increased risk for hormone receptor–negative breast cancer.

This group also had a twofold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with a larger tumor, and significantly higher risk of having positive lymph nodes, regional and/or distant stage, and also of dying after breast cancer, according to an article published June 11 in JAMA Oncology.

“Well-designed clinical trials are needed to definitively test whether weight loss and body composition changes in overweight and obese women or obesity prevention in women of normal weight will reduce breast cancer risk,” wrote Marian L. Neuhouser, Ph.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, and her colleagues (JAMA Oncol. 2015. June 11 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol. 2015.1546]).

The Women’s Health Initiative programs are supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health. One of the researchers disclosed having financial relationships with Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Genetech, and Amgen. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Women who are overweight and obese have a significantly higher risk of postmenopausal invasive breast cancer, particularly hormone receptor–positive cancer.

Major finding: Postmenopausal women with a body mass index of 35 or greater had an 86% increase in the risk of estrogen- and progesterone-receptor–positive breast cancer, compared to normal-weight women.

Data source: Analysis of data from 67,142 postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trials.

Disclosures: The Women’s Health Initiative programs are supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One of the researchers disclosed ties with Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Genetech, and Amgen. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

ASCO: Adjuvant denosumab halves fracture risk for breast cancer patients on AIs

CHICAGO – Adjuvant denosumab is efficacious and safe for reducing fracture risk among women taking aromatase inhibitors (AIs) as part of their treatment for early breast cancer, finds the Austrian Breast & Colorectal Cancer Study Group’s study 18 (ABCSG-18).

Compared with peers randomized to placebo in the phase III trial, women randomized to the antiresorptive monoclonal antibody at the dose typically used to treat osteoporosis were half as likely to experience a first clinical fracture, first author Dr. Michael Gnant reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The benefit was similar whether women had normal bone mineral density at baseline or already had osteopenia.

Patients in the denosumab group did not have a significantly higher rate of adverse events, including the much-feared complication of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

“The actual fracture risk of postmenopausal breast cancer patients on AIs is substantial and may have been underestimated until today,” commented Dr. Gnant, professor of surgery at the Medical University of Vienna. “In these patients with only a modest risk of disease recurrence, adjuvant denosumab significantly reduced the bone side effects of AI treatment. We therefore believe that denosumab 60 mg every 6 months should be considered for clinical practice.”

“Today, several clinical practice guidelines advocate the use of bisphosphonates for breast cancer patients receiving AIs, however, only if they are at high risk for fractures,” he further noted. However, “patients with normal baseline bone mineral density showed a similar fracture risk but also similar benefit from denosumab as compared to patients with baseline T scores below –1, indicating that DEXA scans may be an insufficient way to assess the individual patient’s fracture risk. In view of the benefits in this particular patient subgroup, we may have to rediscuss our current clinical practice guidelines.”

Invited discussant Dr. Robert E. Coleman of the University of Sheffield and Weston Park Hospital in England, said, “It’s very important to dissect out fractures related to subsequent recurrence from fractures due to poor bone health.” Most of the reduction in fracture risk in ABCSG-18 appeared to be because of prevention of fractures before any recurrence, whereas most of that in the AZURE trial (Adjuvant Zoledronic Acid to Reduce Recurrence) of an adjuvant bisphosphonate, another type of antiresorptive agent, appeared to be because of prevention of fractures from bone metastases. “So I think we are seeing something very different with denosumab to what we’ve seen to date with a bisphosphonate,” he said.

“As oncologists, we are somewhat wedded to measuring bone mineral density as the reason for giving bone-targeted therapy to protect [against] bone loss, but there are much better ways of predicting fracture with online algorithms such as FRAX [Fracture Risk Assessment Tool] and others,” Dr. Coleman further commented. “And bone mineral density is a pretty poor predictor of fracture, so it’s perhaps not surprising that the risk reductions were fairly similar” across bone mineral density subgroups.

During a question and answer period, session attendee Dr. Toru Watanabe, Hamamatsu (Japan) Oncology Center, said, “It is really clear that the osteoporosis-related fracture is prevented by denosumab at the dose usually used for the treatment of osteoporosis. That part is very clear. My question is, the same dose is being tested for modifying overall survival or progression-free survival. Don’t you think it’s necessary to conduct some kind of dose-finding trial?”

Two studies are addressing the impact of denosumab on breast cancer outcomes, according to Dr. Gnant: the investigators’ ABCSG-18 study and the Study of Denosumab as Adjuvant Treatment for Women With High-Risk Early Breast Cancer Receiving Neoadjuvant or Adjuvant Therapy (D-CARE), which is using a higher initial dose and tapering after 1 year. “So we will have that indirect comparison at least. My personal expectation would be that there is a trade-off potentially between efficacy and tolerability,” he commented.

The 3,425 postmenopausal breast cancer patients in ABCSG-18 were randomized evenly to receive 60 mg of denosumab or placebo every 6 months. Denosumab is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention and treatment of fractures due to bone metastases (brand name Xgeva) and osteoporosis after menopause (brand name Prolia), as well as other indications. The study used the dose for postmenopausal osteoporosis, which is much lower than that typically used for bone metastases (120 mg every 4 weeks), Dr. Gnant noted.

Main results showed that denosumab was highly efficacious in reducing the risk of first clinical fractures, meaning those that were clinically evident and causing symptoms (hazard ratio, 0.50; P less than .0001), according to data presented at the meeting and simultaneously published (Lancet 2015 May 31).

The estimated 6-year fracture rate was about 10% in the denosumab group and 20% in the placebo group. “Please note that the frequency of clinical fractures reported in this trial that is focusing on bone health is markedly higher than fracture rates reported in previous large AI trials. Obviously, we had a tendency to underreport them in those trials,” Dr. Gnant commented. “The true magnitude of the problem in clinical practice is likely reflected in the placebo group … with approximately one out of five patients experiencing a new clinical fracture within 5-6 years of adjuvant AI treatment.”

Benefit was similar across numerous patient subgroups studied, including the subgroups of women who had a baseline bone mineral density T-score of less than –1 and women who had a baseline bone mineral density T-score of –1 or greater.