User login

Double Vision From a Rare Gastrointestinal Tumor

A 78-year-old man with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia had double vision for 7 weeks. He also had pain in the right side of the face, altered taste, headaches that were worse when he was lying down, and lower abdominal lymphadenopathy.

His clinicians, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, say neurological examination revealed palsies of the right V, VI, VII, and XII cranial nerves. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a clival mass and multiple lesions in the vertebrae. Radionuclide studies showed extensive tumor burden in the patient’s liver and peritoneum.

Because it is the most common cause of clival metastases, the clinicians initially suspected prostate cancer was the source of the symptoms. Moreover, the patient’s prostate-specific antigen was modestly elevated, a finding the clinicians called a red herring. The patient was instead diagnosed with a clival tumor, which is extremely rare—and made even more rare due to upper gastrointestinal (GI), the clinicians say. Only 5 cases have been reported of upper GI malignancy with clival metastasis.

Related: Cancer Prevention and Gastrointestinal Risk

The clivus is a bony structure located where the occipital and sphenoid bones meet, close to the long course of the abducens nerve. Double vision, caused by palsy at that nerve, is a prominent sign of a clival lesion, seen in > 40% of cases, the clinicians note. They suggest considering clival pathology as the cause of an abducens palsy or multiple cranial neuropathies.

The patient underwent several cycles of radiation therapy but ultimately decided on hospice care.

Source:

Lee C, Thon JM, Dhand A. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017: pii: bcr-2017-222725

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222725.

A 78-year-old man with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia had double vision for 7 weeks. He also had pain in the right side of the face, altered taste, headaches that were worse when he was lying down, and lower abdominal lymphadenopathy.

His clinicians, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, say neurological examination revealed palsies of the right V, VI, VII, and XII cranial nerves. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a clival mass and multiple lesions in the vertebrae. Radionuclide studies showed extensive tumor burden in the patient’s liver and peritoneum.

Because it is the most common cause of clival metastases, the clinicians initially suspected prostate cancer was the source of the symptoms. Moreover, the patient’s prostate-specific antigen was modestly elevated, a finding the clinicians called a red herring. The patient was instead diagnosed with a clival tumor, which is extremely rare—and made even more rare due to upper gastrointestinal (GI), the clinicians say. Only 5 cases have been reported of upper GI malignancy with clival metastasis.

Related: Cancer Prevention and Gastrointestinal Risk

The clivus is a bony structure located where the occipital and sphenoid bones meet, close to the long course of the abducens nerve. Double vision, caused by palsy at that nerve, is a prominent sign of a clival lesion, seen in > 40% of cases, the clinicians note. They suggest considering clival pathology as the cause of an abducens palsy or multiple cranial neuropathies.

The patient underwent several cycles of radiation therapy but ultimately decided on hospice care.

Source:

Lee C, Thon JM, Dhand A. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017: pii: bcr-2017-222725

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222725.

A 78-year-old man with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia had double vision for 7 weeks. He also had pain in the right side of the face, altered taste, headaches that were worse when he was lying down, and lower abdominal lymphadenopathy.

His clinicians, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, say neurological examination revealed palsies of the right V, VI, VII, and XII cranial nerves. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a clival mass and multiple lesions in the vertebrae. Radionuclide studies showed extensive tumor burden in the patient’s liver and peritoneum.

Because it is the most common cause of clival metastases, the clinicians initially suspected prostate cancer was the source of the symptoms. Moreover, the patient’s prostate-specific antigen was modestly elevated, a finding the clinicians called a red herring. The patient was instead diagnosed with a clival tumor, which is extremely rare—and made even more rare due to upper gastrointestinal (GI), the clinicians say. Only 5 cases have been reported of upper GI malignancy with clival metastasis.

Related: Cancer Prevention and Gastrointestinal Risk

The clivus is a bony structure located where the occipital and sphenoid bones meet, close to the long course of the abducens nerve. Double vision, caused by palsy at that nerve, is a prominent sign of a clival lesion, seen in > 40% of cases, the clinicians note. They suggest considering clival pathology as the cause of an abducens palsy or multiple cranial neuropathies.

The patient underwent several cycles of radiation therapy but ultimately decided on hospice care.

Source:

Lee C, Thon JM, Dhand A. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017: pii: bcr-2017-222725

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222725.

TAP an alternative to epidural for colorectal surgery

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – In colorectal surgery, transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block was associated with shorter hospital stays than epidural, according to a study that was conducted in patients undergoing both open and laparoscopic surgeries. TAP fared well in both groups.

There were higher rates of nausea/vomiting in the TAP group, suggesting the need for preoperative management in patients preparing to undergo TAP block. Urine retention was higher in the epidural group.

Physicians used liposomal bupivacaine, which is more costly than alternatives, and that fact met some resistance in the audience when the study was presented at the annual meeting of the Western Surgical Association. But patients receiving TAP had a 0.5-day shorter length of stay, which should reduce costs overall, and the drug component cost of TAP was less than $100 more than for the epidural.

“The biggest conclusion we drew from this study was that in patients where you would always consider an epidural historically, like an open procedure or a laparoscopic procedure where the conversion risk to open was higher, [favoring epidural] is now being called into question. We really believe that TAP block affords the length of stay benefit with no change in the pain control regimen after surgery,” Shawn Obi, DO, chief of surgery at Henry Ford Allegiance Health, Jackson, Mich., said in an interview.

The findings dovetail with an overall trend of improved protocols in colon surgery. “I think we’re working toward colorectal surgery as an outpatient operation, similar to what has happened in the joint arena,” said Dr. Obi.

His colleague, Matt Torgeson, DO, who is a surgical resident at Henry Ford Allegiance Health, noted that the hospital stay following colorectal surgery was once 6-8 days, and it has been shortened to 3-3.5 days. Enhanced recovery protocols made the biggest impact, shaving about 3 days. “Now we’re going to be seeing small, incremental changes,” said Dr. Torgeson.

The researchers randomized patients undergoing open or laparoscopic colorectal surgery to receive either an epidural (n = 37) or TAP block (n = 41). All patients entered an enhanced recovery pathway following surgery, with standardized discharge criteria. The two groups had similar times to return to normal bowel function (TAP, 1.7 days; epidural, 1.9 days) but the length of hospital stay was lower in the TAP group (2.8 days vs. 3.3 days; P = .023; 74.9 hours vs. 86.3 hours; P = .045). Subjects in the epidural group had a higher frequency of urinary retention (29.7% vs. 14.6%), though this did not reach statistical significance (P = .11). Postoperative nausea occurred at a higher rate in the TAP group (31.7% vs. 13.5%; odds ratio, 2.97), though this result just missed significance (P = .06).

In patients who had open surgery or laparoscopic surgery that converted to open, the length of stay was 2.9 days in the TAP group (n = 9) and 4.4 days in the epidural group (n = 5). Those numbers are small, but they suggest that TAP is effective even in open surgery. The cost of TAP was about $80 more than epidural medication ($406.16 vs. $322.73).

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Torgeson and Dr. Obi reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – In colorectal surgery, transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block was associated with shorter hospital stays than epidural, according to a study that was conducted in patients undergoing both open and laparoscopic surgeries. TAP fared well in both groups.

There were higher rates of nausea/vomiting in the TAP group, suggesting the need for preoperative management in patients preparing to undergo TAP block. Urine retention was higher in the epidural group.

Physicians used liposomal bupivacaine, which is more costly than alternatives, and that fact met some resistance in the audience when the study was presented at the annual meeting of the Western Surgical Association. But patients receiving TAP had a 0.5-day shorter length of stay, which should reduce costs overall, and the drug component cost of TAP was less than $100 more than for the epidural.

“The biggest conclusion we drew from this study was that in patients where you would always consider an epidural historically, like an open procedure or a laparoscopic procedure where the conversion risk to open was higher, [favoring epidural] is now being called into question. We really believe that TAP block affords the length of stay benefit with no change in the pain control regimen after surgery,” Shawn Obi, DO, chief of surgery at Henry Ford Allegiance Health, Jackson, Mich., said in an interview.

The findings dovetail with an overall trend of improved protocols in colon surgery. “I think we’re working toward colorectal surgery as an outpatient operation, similar to what has happened in the joint arena,” said Dr. Obi.

His colleague, Matt Torgeson, DO, who is a surgical resident at Henry Ford Allegiance Health, noted that the hospital stay following colorectal surgery was once 6-8 days, and it has been shortened to 3-3.5 days. Enhanced recovery protocols made the biggest impact, shaving about 3 days. “Now we’re going to be seeing small, incremental changes,” said Dr. Torgeson.

The researchers randomized patients undergoing open or laparoscopic colorectal surgery to receive either an epidural (n = 37) or TAP block (n = 41). All patients entered an enhanced recovery pathway following surgery, with standardized discharge criteria. The two groups had similar times to return to normal bowel function (TAP, 1.7 days; epidural, 1.9 days) but the length of hospital stay was lower in the TAP group (2.8 days vs. 3.3 days; P = .023; 74.9 hours vs. 86.3 hours; P = .045). Subjects in the epidural group had a higher frequency of urinary retention (29.7% vs. 14.6%), though this did not reach statistical significance (P = .11). Postoperative nausea occurred at a higher rate in the TAP group (31.7% vs. 13.5%; odds ratio, 2.97), though this result just missed significance (P = .06).

In patients who had open surgery or laparoscopic surgery that converted to open, the length of stay was 2.9 days in the TAP group (n = 9) and 4.4 days in the epidural group (n = 5). Those numbers are small, but they suggest that TAP is effective even in open surgery. The cost of TAP was about $80 more than epidural medication ($406.16 vs. $322.73).

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Torgeson and Dr. Obi reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – In colorectal surgery, transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block was associated with shorter hospital stays than epidural, according to a study that was conducted in patients undergoing both open and laparoscopic surgeries. TAP fared well in both groups.

There were higher rates of nausea/vomiting in the TAP group, suggesting the need for preoperative management in patients preparing to undergo TAP block. Urine retention was higher in the epidural group.

Physicians used liposomal bupivacaine, which is more costly than alternatives, and that fact met some resistance in the audience when the study was presented at the annual meeting of the Western Surgical Association. But patients receiving TAP had a 0.5-day shorter length of stay, which should reduce costs overall, and the drug component cost of TAP was less than $100 more than for the epidural.

“The biggest conclusion we drew from this study was that in patients where you would always consider an epidural historically, like an open procedure or a laparoscopic procedure where the conversion risk to open was higher, [favoring epidural] is now being called into question. We really believe that TAP block affords the length of stay benefit with no change in the pain control regimen after surgery,” Shawn Obi, DO, chief of surgery at Henry Ford Allegiance Health, Jackson, Mich., said in an interview.

The findings dovetail with an overall trend of improved protocols in colon surgery. “I think we’re working toward colorectal surgery as an outpatient operation, similar to what has happened in the joint arena,” said Dr. Obi.

His colleague, Matt Torgeson, DO, who is a surgical resident at Henry Ford Allegiance Health, noted that the hospital stay following colorectal surgery was once 6-8 days, and it has been shortened to 3-3.5 days. Enhanced recovery protocols made the biggest impact, shaving about 3 days. “Now we’re going to be seeing small, incremental changes,” said Dr. Torgeson.

The researchers randomized patients undergoing open or laparoscopic colorectal surgery to receive either an epidural (n = 37) or TAP block (n = 41). All patients entered an enhanced recovery pathway following surgery, with standardized discharge criteria. The two groups had similar times to return to normal bowel function (TAP, 1.7 days; epidural, 1.9 days) but the length of hospital stay was lower in the TAP group (2.8 days vs. 3.3 days; P = .023; 74.9 hours vs. 86.3 hours; P = .045). Subjects in the epidural group had a higher frequency of urinary retention (29.7% vs. 14.6%), though this did not reach statistical significance (P = .11). Postoperative nausea occurred at a higher rate in the TAP group (31.7% vs. 13.5%; odds ratio, 2.97), though this result just missed significance (P = .06).

In patients who had open surgery or laparoscopic surgery that converted to open, the length of stay was 2.9 days in the TAP group (n = 9) and 4.4 days in the epidural group (n = 5). Those numbers are small, but they suggest that TAP is effective even in open surgery. The cost of TAP was about $80 more than epidural medication ($406.16 vs. $322.73).

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Torgeson and Dr. Obi reported having no financial disclosures.

AT WSA 2017

Key clinical point: In appropriately selected patients, TAP may be a good alternative to epidural.

Major finding: TAP block was associated with a 0.5-day shorter hospital stay than epidurals.

Data source: Randomized, controlled trial (n = 78).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. Dr. Torgeson and Dr. Obi reported having no financial disclosures.

Regional differences in surgical outcomes could unfairly skew bundled payments

Risk-adjusted adverse outcomes for elective colorectal surgery vary significantly across regions in the United States, and, therefore, regionally based Medicare payments could disadvantage some hospitals.

The findings, presented at the annual Central Surgical Association meeting, suggest that alternative payment models (APMs) should consider regional benchmarks as a variable when evaluating quality and pricing of episodes of care to level the playing field among hospitals, the study authors said.

All hospitals with a minimum of 20 evaluable colorectal resection cases from the master data set regardless of coding quality were identified for comparative outcomes. For hospital analysis, the total number of patients with one or more adverse outcomes (AOs) was tabulated. The total predicted AOs were then set equal to the number of observed events for each hospital by multiplication of the hospital-specific predicted value by the ratio of observed-to-predicted events for the entire final hospital population of patients.

Hospitals were then sorted by the nine Census Bureau regions: region 1 (New England), region 2 (Middle Atlantic), region 3 (South Atlantic), region 4 (East South Central), region 5 (West South Central), region 6 (East North Central), region 7 (West North Central), region 8 (Mountain), and region 9 (Pacific).

Within each region, total patients, total observed AOs, and total predicted AOs were derived from the prediction models. Region-specific standard deviations (SDs) were computed and overall region z scores and risk-adjusted AO rates were calculated for comparison.

A total of 1,497 hospitals had 86,624 patients for the comparative analysis of hospitals with 20 or more qualifying cases. Hospitals averaged 57.9 cases with a median of 43 for the study period. Among the AOs, there were 947 IpD (1.1%), 7,268 prLOS (8.4%), 762 PD90 (0.9%), and 14,552 RA90 (16.8%) patients. An additional 1,130 patients died during or following readmission within the 90-day postdischarge period for total postoperative deaths including inpatient and 90 days following discharge of 2,839 (3.3%). Total patients with one or more AOs were 21,064 (24.3%).

Among the hospitals, 49 (3.3%) had z scores of –2.0 or less. These best-performing hospitals had a median z score of –2.24 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 10.8%. A total of 159 hospitals (10.6%) had z scores that were greater than –2.0 but less than or equal to –1.0. These hospitals had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 15.1%. There were 66 hospitals (4.4%) with z scores greater than +2.0. These suboptimal-performing hospitals had a z score of +2.39 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 38.8%. A total of 209 hospitals (14.0%) had z scores greater than or equal to +1.0 but less than +2.0. They had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 32.5%.

Findings showed a nearly 5-SD difference between the Pacific region and the New England region. In addition, the results showed a 2.5% absolute risk–adjusted adverse outcome rate difference between the top- and the lowest-performing regions.

What findings could mean for bundled payments

The findings raise concerns about a lopsided playing field for hospitals when it comes to bundled payments, according to the study authors.

“What that means is if you have more readmissions and more complications and your historical profile is being used to pay for care going forward, regions of the country with poorer outcomes would get higher prices than those areas with better outcomes,” Dr. Fry, executive vice president, clinical outcomes management, MPA Healthcare Solutions, Chicago, said in an interview.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has used performance of the Census Bureau region as a major factor in defining target price at the beginning of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment program. Regional performance will become the exclusive basis for the target price as the program matures into successive years, the study authors noted. A colorectal surgery bundle has not yet been proposed by Medicare, but because it’s a common operation with relatively high adverse outcomes rates, it is expected to be included in a future bundled payment strategy, according to the investigators.

Dr. Fry and his coauthors concluded that hospitals and surgeons may find meeting the target price of a bundled payment to improve margins or avoid losses more difficult for any inpatient operation if they are in a best-performing region.

A 2.5% adverse outcome rate difference between regions may not seem like much, but the variance could mean a wide disparity in payments, Dr. Fry said.

“We have done previous research with colon operations and identified that a readmission after an elective colon operation costs about an additional $30,000,” he said. “If cases being done in poorer-performing areas of the country have two or three more readmissions per 100 patients, then it means those areas are going to be paid on average $1,000 more per case than would be the circumstance for those areas where outcomes are better.”

By these parameters, the CMS would basically be rewarding care that is suboptimal in the regions with high adverse outcome rates, he said.

“APMs are going to evolve in health care,” Dr. Fry said. “I feel that regional and local outcomes, as illustrated in this article, are different, and that a national standard for expected outcomes needs to be the benchmark. The national benchmark becomes a method to stimulate hospitals and surgeons to know what the results of their care really are and how they compare nationally.”

Perspectives on the study

However, it remains unclear whether adjustment for quality measures should be based on regions, and, if so, how those regions should be broken down, said Dr. Whitcomb, who is cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Another question is whether adjustments should take into consideration the characteristics of hospitals, he said, for example, the general demographics of patients who visit academic medical centers, compared with the demographics of community hospitals. Dr. Whitcomb also noted that programs such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program has faced criticism for not factoring in the disproportionately high share of low socioeconomic status patients at some hospitals.

“The paper raises the important issue of comparing apples to apples when quality measures are used to determine payment under alternative payment models,” Dr. Whitcomb said in an interview. “But a number of questions remain about how risk should be adjusted and how benchmarking should occur between hospitals.”

“The overall average adverse outcome in the study was 24.3%, but 16.8% of that 24% is due to readmissions,” he said in an interview. “Length of stay and readmissions are correlated – people who tend to have long lengths of stay tend to be readmitted. If you add those two rates together in the study, almost all of the outcome rate is the length of stay and readmissions. You could argue [that] mortality [should] be more heavily weighted than length of stay and readmissions.”

In regard to adjusting risk by region, there is good research that utilization of procedures varies dramatically by region and that some of this variation may have more to do with overutilization of procedures, Dr. Pitt added.

“I would think that risk adjusting for type of operation, diagnosis, and socioeconomic status –across the country – would be more appropriate than risk adjusting by region where there may be major differences in patient selection and indication for operation,” he said.

For example, there is currently an international debate about the management of diverticulitis, including whether and when to operate as well as what procedure(s) to perform.

“It may be in one region, there’s a very low threshold to operate, whereas in another region, there’s a high threshold to operate,” he said. “And the operations that are done may be very different in one region than another.”

Dr. Fry and his colleagues are planning future research in this area, and he said he hopes their studies will impact how the CMS rolls out its bundled payment programs in the future.

“What we’re trying to stimulate is for payment models to be nationally indexed and not regionally indexed,” he said. “CMS is doing that now with [Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups]. They are paying a price for a total joint replacement, a price for a colon resection, a price for a heart operation – and they do make adjustments based on the local wage and price index, but the core payment is linked to a national payment model, and that’s what we would like to see happen with the bundled payment initiative.”

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

Risk-adjusted adverse outcomes for elective colorectal surgery vary significantly across regions in the United States, and, therefore, regionally based Medicare payments could disadvantage some hospitals.

The findings, presented at the annual Central Surgical Association meeting, suggest that alternative payment models (APMs) should consider regional benchmarks as a variable when evaluating quality and pricing of episodes of care to level the playing field among hospitals, the study authors said.

All hospitals with a minimum of 20 evaluable colorectal resection cases from the master data set regardless of coding quality were identified for comparative outcomes. For hospital analysis, the total number of patients with one or more adverse outcomes (AOs) was tabulated. The total predicted AOs were then set equal to the number of observed events for each hospital by multiplication of the hospital-specific predicted value by the ratio of observed-to-predicted events for the entire final hospital population of patients.

Hospitals were then sorted by the nine Census Bureau regions: region 1 (New England), region 2 (Middle Atlantic), region 3 (South Atlantic), region 4 (East South Central), region 5 (West South Central), region 6 (East North Central), region 7 (West North Central), region 8 (Mountain), and region 9 (Pacific).

Within each region, total patients, total observed AOs, and total predicted AOs were derived from the prediction models. Region-specific standard deviations (SDs) were computed and overall region z scores and risk-adjusted AO rates were calculated for comparison.

A total of 1,497 hospitals had 86,624 patients for the comparative analysis of hospitals with 20 or more qualifying cases. Hospitals averaged 57.9 cases with a median of 43 for the study period. Among the AOs, there were 947 IpD (1.1%), 7,268 prLOS (8.4%), 762 PD90 (0.9%), and 14,552 RA90 (16.8%) patients. An additional 1,130 patients died during or following readmission within the 90-day postdischarge period for total postoperative deaths including inpatient and 90 days following discharge of 2,839 (3.3%). Total patients with one or more AOs were 21,064 (24.3%).

Among the hospitals, 49 (3.3%) had z scores of –2.0 or less. These best-performing hospitals had a median z score of –2.24 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 10.8%. A total of 159 hospitals (10.6%) had z scores that were greater than –2.0 but less than or equal to –1.0. These hospitals had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 15.1%. There were 66 hospitals (4.4%) with z scores greater than +2.0. These suboptimal-performing hospitals had a z score of +2.39 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 38.8%. A total of 209 hospitals (14.0%) had z scores greater than or equal to +1.0 but less than +2.0. They had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 32.5%.

Findings showed a nearly 5-SD difference between the Pacific region and the New England region. In addition, the results showed a 2.5% absolute risk–adjusted adverse outcome rate difference between the top- and the lowest-performing regions.

What findings could mean for bundled payments

The findings raise concerns about a lopsided playing field for hospitals when it comes to bundled payments, according to the study authors.

“What that means is if you have more readmissions and more complications and your historical profile is being used to pay for care going forward, regions of the country with poorer outcomes would get higher prices than those areas with better outcomes,” Dr. Fry, executive vice president, clinical outcomes management, MPA Healthcare Solutions, Chicago, said in an interview.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has used performance of the Census Bureau region as a major factor in defining target price at the beginning of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment program. Regional performance will become the exclusive basis for the target price as the program matures into successive years, the study authors noted. A colorectal surgery bundle has not yet been proposed by Medicare, but because it’s a common operation with relatively high adverse outcomes rates, it is expected to be included in a future bundled payment strategy, according to the investigators.

Dr. Fry and his coauthors concluded that hospitals and surgeons may find meeting the target price of a bundled payment to improve margins or avoid losses more difficult for any inpatient operation if they are in a best-performing region.

A 2.5% adverse outcome rate difference between regions may not seem like much, but the variance could mean a wide disparity in payments, Dr. Fry said.

“We have done previous research with colon operations and identified that a readmission after an elective colon operation costs about an additional $30,000,” he said. “If cases being done in poorer-performing areas of the country have two or three more readmissions per 100 patients, then it means those areas are going to be paid on average $1,000 more per case than would be the circumstance for those areas where outcomes are better.”

By these parameters, the CMS would basically be rewarding care that is suboptimal in the regions with high adverse outcome rates, he said.

“APMs are going to evolve in health care,” Dr. Fry said. “I feel that regional and local outcomes, as illustrated in this article, are different, and that a national standard for expected outcomes needs to be the benchmark. The national benchmark becomes a method to stimulate hospitals and surgeons to know what the results of their care really are and how they compare nationally.”

Perspectives on the study

However, it remains unclear whether adjustment for quality measures should be based on regions, and, if so, how those regions should be broken down, said Dr. Whitcomb, who is cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Another question is whether adjustments should take into consideration the characteristics of hospitals, he said, for example, the general demographics of patients who visit academic medical centers, compared with the demographics of community hospitals. Dr. Whitcomb also noted that programs such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program has faced criticism for not factoring in the disproportionately high share of low socioeconomic status patients at some hospitals.

“The paper raises the important issue of comparing apples to apples when quality measures are used to determine payment under alternative payment models,” Dr. Whitcomb said in an interview. “But a number of questions remain about how risk should be adjusted and how benchmarking should occur between hospitals.”

“The overall average adverse outcome in the study was 24.3%, but 16.8% of that 24% is due to readmissions,” he said in an interview. “Length of stay and readmissions are correlated – people who tend to have long lengths of stay tend to be readmitted. If you add those two rates together in the study, almost all of the outcome rate is the length of stay and readmissions. You could argue [that] mortality [should] be more heavily weighted than length of stay and readmissions.”

In regard to adjusting risk by region, there is good research that utilization of procedures varies dramatically by region and that some of this variation may have more to do with overutilization of procedures, Dr. Pitt added.

“I would think that risk adjusting for type of operation, diagnosis, and socioeconomic status –across the country – would be more appropriate than risk adjusting by region where there may be major differences in patient selection and indication for operation,” he said.

For example, there is currently an international debate about the management of diverticulitis, including whether and when to operate as well as what procedure(s) to perform.

“It may be in one region, there’s a very low threshold to operate, whereas in another region, there’s a high threshold to operate,” he said. “And the operations that are done may be very different in one region than another.”

Dr. Fry and his colleagues are planning future research in this area, and he said he hopes their studies will impact how the CMS rolls out its bundled payment programs in the future.

“What we’re trying to stimulate is for payment models to be nationally indexed and not regionally indexed,” he said. “CMS is doing that now with [Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups]. They are paying a price for a total joint replacement, a price for a colon resection, a price for a heart operation – and they do make adjustments based on the local wage and price index, but the core payment is linked to a national payment model, and that’s what we would like to see happen with the bundled payment initiative.”

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

Risk-adjusted adverse outcomes for elective colorectal surgery vary significantly across regions in the United States, and, therefore, regionally based Medicare payments could disadvantage some hospitals.

The findings, presented at the annual Central Surgical Association meeting, suggest that alternative payment models (APMs) should consider regional benchmarks as a variable when evaluating quality and pricing of episodes of care to level the playing field among hospitals, the study authors said.

All hospitals with a minimum of 20 evaluable colorectal resection cases from the master data set regardless of coding quality were identified for comparative outcomes. For hospital analysis, the total number of patients with one or more adverse outcomes (AOs) was tabulated. The total predicted AOs were then set equal to the number of observed events for each hospital by multiplication of the hospital-specific predicted value by the ratio of observed-to-predicted events for the entire final hospital population of patients.

Hospitals were then sorted by the nine Census Bureau regions: region 1 (New England), region 2 (Middle Atlantic), region 3 (South Atlantic), region 4 (East South Central), region 5 (West South Central), region 6 (East North Central), region 7 (West North Central), region 8 (Mountain), and region 9 (Pacific).

Within each region, total patients, total observed AOs, and total predicted AOs were derived from the prediction models. Region-specific standard deviations (SDs) were computed and overall region z scores and risk-adjusted AO rates were calculated for comparison.

A total of 1,497 hospitals had 86,624 patients for the comparative analysis of hospitals with 20 or more qualifying cases. Hospitals averaged 57.9 cases with a median of 43 for the study period. Among the AOs, there were 947 IpD (1.1%), 7,268 prLOS (8.4%), 762 PD90 (0.9%), and 14,552 RA90 (16.8%) patients. An additional 1,130 patients died during or following readmission within the 90-day postdischarge period for total postoperative deaths including inpatient and 90 days following discharge of 2,839 (3.3%). Total patients with one or more AOs were 21,064 (24.3%).

Among the hospitals, 49 (3.3%) had z scores of –2.0 or less. These best-performing hospitals had a median z score of –2.24 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 10.8%. A total of 159 hospitals (10.6%) had z scores that were greater than –2.0 but less than or equal to –1.0. These hospitals had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 15.1%. There were 66 hospitals (4.4%) with z scores greater than +2.0. These suboptimal-performing hospitals had a z score of +2.39 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 38.8%. A total of 209 hospitals (14.0%) had z scores greater than or equal to +1.0 but less than +2.0. They had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 32.5%.

Findings showed a nearly 5-SD difference between the Pacific region and the New England region. In addition, the results showed a 2.5% absolute risk–adjusted adverse outcome rate difference between the top- and the lowest-performing regions.

What findings could mean for bundled payments

The findings raise concerns about a lopsided playing field for hospitals when it comes to bundled payments, according to the study authors.

“What that means is if you have more readmissions and more complications and your historical profile is being used to pay for care going forward, regions of the country with poorer outcomes would get higher prices than those areas with better outcomes,” Dr. Fry, executive vice president, clinical outcomes management, MPA Healthcare Solutions, Chicago, said in an interview.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has used performance of the Census Bureau region as a major factor in defining target price at the beginning of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment program. Regional performance will become the exclusive basis for the target price as the program matures into successive years, the study authors noted. A colorectal surgery bundle has not yet been proposed by Medicare, but because it’s a common operation with relatively high adverse outcomes rates, it is expected to be included in a future bundled payment strategy, according to the investigators.

Dr. Fry and his coauthors concluded that hospitals and surgeons may find meeting the target price of a bundled payment to improve margins or avoid losses more difficult for any inpatient operation if they are in a best-performing region.

A 2.5% adverse outcome rate difference between regions may not seem like much, but the variance could mean a wide disparity in payments, Dr. Fry said.

“We have done previous research with colon operations and identified that a readmission after an elective colon operation costs about an additional $30,000,” he said. “If cases being done in poorer-performing areas of the country have two or three more readmissions per 100 patients, then it means those areas are going to be paid on average $1,000 more per case than would be the circumstance for those areas where outcomes are better.”

By these parameters, the CMS would basically be rewarding care that is suboptimal in the regions with high adverse outcome rates, he said.

“APMs are going to evolve in health care,” Dr. Fry said. “I feel that regional and local outcomes, as illustrated in this article, are different, and that a national standard for expected outcomes needs to be the benchmark. The national benchmark becomes a method to stimulate hospitals and surgeons to know what the results of their care really are and how they compare nationally.”

Perspectives on the study

However, it remains unclear whether adjustment for quality measures should be based on regions, and, if so, how those regions should be broken down, said Dr. Whitcomb, who is cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Another question is whether adjustments should take into consideration the characteristics of hospitals, he said, for example, the general demographics of patients who visit academic medical centers, compared with the demographics of community hospitals. Dr. Whitcomb also noted that programs such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program has faced criticism for not factoring in the disproportionately high share of low socioeconomic status patients at some hospitals.

“The paper raises the important issue of comparing apples to apples when quality measures are used to determine payment under alternative payment models,” Dr. Whitcomb said in an interview. “But a number of questions remain about how risk should be adjusted and how benchmarking should occur between hospitals.”

“The overall average adverse outcome in the study was 24.3%, but 16.8% of that 24% is due to readmissions,” he said in an interview. “Length of stay and readmissions are correlated – people who tend to have long lengths of stay tend to be readmitted. If you add those two rates together in the study, almost all of the outcome rate is the length of stay and readmissions. You could argue [that] mortality [should] be more heavily weighted than length of stay and readmissions.”

In regard to adjusting risk by region, there is good research that utilization of procedures varies dramatically by region and that some of this variation may have more to do with overutilization of procedures, Dr. Pitt added.

“I would think that risk adjusting for type of operation, diagnosis, and socioeconomic status –across the country – would be more appropriate than risk adjusting by region where there may be major differences in patient selection and indication for operation,” he said.

For example, there is currently an international debate about the management of diverticulitis, including whether and when to operate as well as what procedure(s) to perform.

“It may be in one region, there’s a very low threshold to operate, whereas in another region, there’s a high threshold to operate,” he said. “And the operations that are done may be very different in one region than another.”

Dr. Fry and his colleagues are planning future research in this area, and he said he hopes their studies will impact how the CMS rolls out its bundled payment programs in the future.

“What we’re trying to stimulate is for payment models to be nationally indexed and not regionally indexed,” he said. “CMS is doing that now with [Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups]. They are paying a price for a total joint replacement, a price for a colon resection, a price for a heart operation – and they do make adjustments based on the local wage and price index, but the core payment is linked to a national payment model, and that’s what we would like to see happen with the bundled payment initiative.”

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

Right Paraduodenal Hernia

Paraduodenal hernia, also called mesocolic hernia, is a type of internal hernia that is thought to be caused by a congenital defect involving abnormal retroperitoneal fixation of the mesentery due to abnormal rotation of the midgut.1 Internal hernias account for only 1% of all hernias, and paraduodenal hernias make up 50% of those.2

Paraduodenal hernias can be classified as left or right with left being far more common than right, 75% and 25%, respectively.2 Due to the fixation abnormalities in the midgut, fossae are formed that help to classify left vs right paraduodenal hernias. Herniation through Landzert fossae results in a left paraduodenal hernia with the primary constituents of the hernia sac being the inferior mesenteric artery and vein.1 This result is due to an in utero defect of the small intestine herniated between the inferior mesenteric vein and posterior parietal attachments of the descending mesocolon to the retroperitoneal.3

In a right paraduodenal hernia, herniation occurs through Waldeyer fossae with the main contents of the hernia sac being the iliocolic, right colic, and middle colic vessels within the anterior wall and the superior mesenteric artery along the medial border of the hernia.1 Since there is a failure of rotation around the superior mesenteric artery, the majority of the small intestine remains to the right of the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in the small intestine being trapped between the posteriolateral peritoneum.3 Regardless of the type of paraduodenal hernia, patients usually will present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In these types of hernias, a computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast may suggest evidence of obstruction between the duodenum and jejunum, but this may be unclear. Although rare, clinical suspicion of paraduodenal hernia is necessary to prevent ensuing complications and mortality.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, intermittent epigastric abdominal pain, and obstipation, which were suggestive of a small bowel obstruction. The patient reported similar intermittent episodes over the past 10 years that had resolved without surgery. The patient had no history of abdominal surgeries. A nasogastric tube was inserted and immediately drew out a significant amount of bilious contents. A CT scan indicated an obstruction at the proximal jejunum with suspicion of an internal hernia.

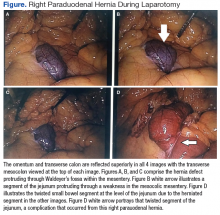

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy soon after, which confirmed a right paraduodenal hernia (Figure). The surgery began laproscopically by retracting the omentum and transverse colon cranially to expose the ligament of Treitz. The hernia defect was identified on the mesentery where the proximal jejunum twisted on itself in a loop. The hernia was untwisted, and adhesions were removed. The posterior attachment of the hernia sac was freed with harmonic cautery and blunt dissection along with its attachment to the ligament of Treitz. In the process of freeing the herniation, a 1-cm enterotomy ensued, which did not contain succus or spillage of luminal contents at that time. Due to difficulties in visualizing the remainder of the small bowel, the procedure was converted to a laparotomy. This allowed complete freeing of the twisted loop of bowel.

Afterward, there was succus and bile draining from the enterotomy, so it was closed transversely in 2 layers, making sure there was a lumen between the layers. The first and second parts of the duodenum were examined followed by palpitation of the duodenal sweep. The remainder of the small bowel was visualized to the cecum, and the retroperitoneal space was dissected out of the hernia sac space. The abdomen was irrigated, and the omentum was draped back over the intestines. The fascia was closed followed by skin reapproximation with staples. The patient experienced an uneventful recovery and was discharged on day 6 with resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Paraduodenal hernias are a type of internal hernia and a rare cause of intestinal obstruction accounting for about 0.5% of all hernias. Right paraduodenal hernias are far less common than left paraduodenal hernias and occur due to a defect in the jejunum mesentery called Waldeyer fossae.4 This is located at the third part of the duodenum and behind the superior mesenteric artery.4 Symptoms of paraduodenal hernias are nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, and intermittent cramping. Symptoms of obstruction can be intermittent due to the small bowel herniating through the fossae and then retracting.1 Computed tomography has good specificity and aides in the diagnosis of an internal hernia, but physicians must have a high index of suspicion as well.5

Definitive diagnosis and treatment of paraduodenal hernias involves laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy to visualize the internal hernia and its surrounding sac.4,5 All hernias should be repaired to prevent strangulation of the bowel, but internal hernias are even more important to fix because these hernias may not present until there is severe injury to the bowel.5 On identification of the paraduodenal hernia, it is important to release the bowel from the hernia sac, free up adhesions, and place small bowel segments back into the correct anatomical position.4,5

In the event of bowel injury, resection with reanastomosis is indicated. Careful dissection is important to prevent injury to the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies most of the small bowel and ascending colon.4,5 Injury to the superior mesenteric artery could lead to ischemia and gangrenous bowel.2 Immediate detection and early surgery intervention of these congenital hernias can prevent such complications.2 The literature includes reports of paraduodenal hernias with complications of gangrenous bowel that required small bowel resection.2 These complications further emphasize the need to proceed immediately with surgery if a paraduodenal hernia is suspected.

Conclusion

This rare cause of bowel obstruction was documented in order to emphasize the importance of having a high clinical suspicion for a paraduodenal hernia. This particular patient with no history of abdominal surgeries had previously dealt with bowel obstruction and would likely have this complication again without surgical intervention. Patients with paraduodenal hernias also are at risk for bowel ischemia, other high-risk complications, and even death.5 Although a CT scan provided information about an approximate location of the obstruction, laparoscopy confirmed the diagnosis. Going into the operation with paraduodenal hernia in the differential allowed the surgeon to be prepared for the appropriate anatomy involved with this procedure to minimize damage to important structures, such as the superior mesenteric artery and its branches.

1. Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

2. Fukada T, Mukai H, Shimamura F, Furukawa T, Miyazaki M. A causal relationship between right paraduodenal hernia and superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:159.

3. Skandalakis JE. Peritoneum, omenta, and internal hernias. In: Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, eds. Skandalakis Surgical Anatomy: The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. 1st ed. Athens, Greece: Paschalidis Medical Publications; 2004:chap 10.

4. Papaziogas B, Souparis A, Makris J, Alexandrakis A, Papaziogas T. Surgical images: soft tissue. Right paraduodenal hernia. Can J Surg. 2004;47(3):195-196.

5. Manfredelli S, Andrea Z, Stefano P, et al. Rare small bowel obstruction: right paraduodenal hernia. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(4):412-415.

Paraduodenal hernia, also called mesocolic hernia, is a type of internal hernia that is thought to be caused by a congenital defect involving abnormal retroperitoneal fixation of the mesentery due to abnormal rotation of the midgut.1 Internal hernias account for only 1% of all hernias, and paraduodenal hernias make up 50% of those.2

Paraduodenal hernias can be classified as left or right with left being far more common than right, 75% and 25%, respectively.2 Due to the fixation abnormalities in the midgut, fossae are formed that help to classify left vs right paraduodenal hernias. Herniation through Landzert fossae results in a left paraduodenal hernia with the primary constituents of the hernia sac being the inferior mesenteric artery and vein.1 This result is due to an in utero defect of the small intestine herniated between the inferior mesenteric vein and posterior parietal attachments of the descending mesocolon to the retroperitoneal.3

In a right paraduodenal hernia, herniation occurs through Waldeyer fossae with the main contents of the hernia sac being the iliocolic, right colic, and middle colic vessels within the anterior wall and the superior mesenteric artery along the medial border of the hernia.1 Since there is a failure of rotation around the superior mesenteric artery, the majority of the small intestine remains to the right of the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in the small intestine being trapped between the posteriolateral peritoneum.3 Regardless of the type of paraduodenal hernia, patients usually will present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In these types of hernias, a computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast may suggest evidence of obstruction between the duodenum and jejunum, but this may be unclear. Although rare, clinical suspicion of paraduodenal hernia is necessary to prevent ensuing complications and mortality.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, intermittent epigastric abdominal pain, and obstipation, which were suggestive of a small bowel obstruction. The patient reported similar intermittent episodes over the past 10 years that had resolved without surgery. The patient had no history of abdominal surgeries. A nasogastric tube was inserted and immediately drew out a significant amount of bilious contents. A CT scan indicated an obstruction at the proximal jejunum with suspicion of an internal hernia.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy soon after, which confirmed a right paraduodenal hernia (Figure). The surgery began laproscopically by retracting the omentum and transverse colon cranially to expose the ligament of Treitz. The hernia defect was identified on the mesentery where the proximal jejunum twisted on itself in a loop. The hernia was untwisted, and adhesions were removed. The posterior attachment of the hernia sac was freed with harmonic cautery and blunt dissection along with its attachment to the ligament of Treitz. In the process of freeing the herniation, a 1-cm enterotomy ensued, which did not contain succus or spillage of luminal contents at that time. Due to difficulties in visualizing the remainder of the small bowel, the procedure was converted to a laparotomy. This allowed complete freeing of the twisted loop of bowel.

Afterward, there was succus and bile draining from the enterotomy, so it was closed transversely in 2 layers, making sure there was a lumen between the layers. The first and second parts of the duodenum were examined followed by palpitation of the duodenal sweep. The remainder of the small bowel was visualized to the cecum, and the retroperitoneal space was dissected out of the hernia sac space. The abdomen was irrigated, and the omentum was draped back over the intestines. The fascia was closed followed by skin reapproximation with staples. The patient experienced an uneventful recovery and was discharged on day 6 with resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Paraduodenal hernias are a type of internal hernia and a rare cause of intestinal obstruction accounting for about 0.5% of all hernias. Right paraduodenal hernias are far less common than left paraduodenal hernias and occur due to a defect in the jejunum mesentery called Waldeyer fossae.4 This is located at the third part of the duodenum and behind the superior mesenteric artery.4 Symptoms of paraduodenal hernias are nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, and intermittent cramping. Symptoms of obstruction can be intermittent due to the small bowel herniating through the fossae and then retracting.1 Computed tomography has good specificity and aides in the diagnosis of an internal hernia, but physicians must have a high index of suspicion as well.5

Definitive diagnosis and treatment of paraduodenal hernias involves laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy to visualize the internal hernia and its surrounding sac.4,5 All hernias should be repaired to prevent strangulation of the bowel, but internal hernias are even more important to fix because these hernias may not present until there is severe injury to the bowel.5 On identification of the paraduodenal hernia, it is important to release the bowel from the hernia sac, free up adhesions, and place small bowel segments back into the correct anatomical position.4,5

In the event of bowel injury, resection with reanastomosis is indicated. Careful dissection is important to prevent injury to the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies most of the small bowel and ascending colon.4,5 Injury to the superior mesenteric artery could lead to ischemia and gangrenous bowel.2 Immediate detection and early surgery intervention of these congenital hernias can prevent such complications.2 The literature includes reports of paraduodenal hernias with complications of gangrenous bowel that required small bowel resection.2 These complications further emphasize the need to proceed immediately with surgery if a paraduodenal hernia is suspected.

Conclusion

This rare cause of bowel obstruction was documented in order to emphasize the importance of having a high clinical suspicion for a paraduodenal hernia. This particular patient with no history of abdominal surgeries had previously dealt with bowel obstruction and would likely have this complication again without surgical intervention. Patients with paraduodenal hernias also are at risk for bowel ischemia, other high-risk complications, and even death.5 Although a CT scan provided information about an approximate location of the obstruction, laparoscopy confirmed the diagnosis. Going into the operation with paraduodenal hernia in the differential allowed the surgeon to be prepared for the appropriate anatomy involved with this procedure to minimize damage to important structures, such as the superior mesenteric artery and its branches.

Paraduodenal hernia, also called mesocolic hernia, is a type of internal hernia that is thought to be caused by a congenital defect involving abnormal retroperitoneal fixation of the mesentery due to abnormal rotation of the midgut.1 Internal hernias account for only 1% of all hernias, and paraduodenal hernias make up 50% of those.2

Paraduodenal hernias can be classified as left or right with left being far more common than right, 75% and 25%, respectively.2 Due to the fixation abnormalities in the midgut, fossae are formed that help to classify left vs right paraduodenal hernias. Herniation through Landzert fossae results in a left paraduodenal hernia with the primary constituents of the hernia sac being the inferior mesenteric artery and vein.1 This result is due to an in utero defect of the small intestine herniated between the inferior mesenteric vein and posterior parietal attachments of the descending mesocolon to the retroperitoneal.3

In a right paraduodenal hernia, herniation occurs through Waldeyer fossae with the main contents of the hernia sac being the iliocolic, right colic, and middle colic vessels within the anterior wall and the superior mesenteric artery along the medial border of the hernia.1 Since there is a failure of rotation around the superior mesenteric artery, the majority of the small intestine remains to the right of the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in the small intestine being trapped between the posteriolateral peritoneum.3 Regardless of the type of paraduodenal hernia, patients usually will present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In these types of hernias, a computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast may suggest evidence of obstruction between the duodenum and jejunum, but this may be unclear. Although rare, clinical suspicion of paraduodenal hernia is necessary to prevent ensuing complications and mortality.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, intermittent epigastric abdominal pain, and obstipation, which were suggestive of a small bowel obstruction. The patient reported similar intermittent episodes over the past 10 years that had resolved without surgery. The patient had no history of abdominal surgeries. A nasogastric tube was inserted and immediately drew out a significant amount of bilious contents. A CT scan indicated an obstruction at the proximal jejunum with suspicion of an internal hernia.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy soon after, which confirmed a right paraduodenal hernia (Figure). The surgery began laproscopically by retracting the omentum and transverse colon cranially to expose the ligament of Treitz. The hernia defect was identified on the mesentery where the proximal jejunum twisted on itself in a loop. The hernia was untwisted, and adhesions were removed. The posterior attachment of the hernia sac was freed with harmonic cautery and blunt dissection along with its attachment to the ligament of Treitz. In the process of freeing the herniation, a 1-cm enterotomy ensued, which did not contain succus or spillage of luminal contents at that time. Due to difficulties in visualizing the remainder of the small bowel, the procedure was converted to a laparotomy. This allowed complete freeing of the twisted loop of bowel.

Afterward, there was succus and bile draining from the enterotomy, so it was closed transversely in 2 layers, making sure there was a lumen between the layers. The first and second parts of the duodenum were examined followed by palpitation of the duodenal sweep. The remainder of the small bowel was visualized to the cecum, and the retroperitoneal space was dissected out of the hernia sac space. The abdomen was irrigated, and the omentum was draped back over the intestines. The fascia was closed followed by skin reapproximation with staples. The patient experienced an uneventful recovery and was discharged on day 6 with resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Paraduodenal hernias are a type of internal hernia and a rare cause of intestinal obstruction accounting for about 0.5% of all hernias. Right paraduodenal hernias are far less common than left paraduodenal hernias and occur due to a defect in the jejunum mesentery called Waldeyer fossae.4 This is located at the third part of the duodenum and behind the superior mesenteric artery.4 Symptoms of paraduodenal hernias are nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, and intermittent cramping. Symptoms of obstruction can be intermittent due to the small bowel herniating through the fossae and then retracting.1 Computed tomography has good specificity and aides in the diagnosis of an internal hernia, but physicians must have a high index of suspicion as well.5

Definitive diagnosis and treatment of paraduodenal hernias involves laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy to visualize the internal hernia and its surrounding sac.4,5 All hernias should be repaired to prevent strangulation of the bowel, but internal hernias are even more important to fix because these hernias may not present until there is severe injury to the bowel.5 On identification of the paraduodenal hernia, it is important to release the bowel from the hernia sac, free up adhesions, and place small bowel segments back into the correct anatomical position.4,5

In the event of bowel injury, resection with reanastomosis is indicated. Careful dissection is important to prevent injury to the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies most of the small bowel and ascending colon.4,5 Injury to the superior mesenteric artery could lead to ischemia and gangrenous bowel.2 Immediate detection and early surgery intervention of these congenital hernias can prevent such complications.2 The literature includes reports of paraduodenal hernias with complications of gangrenous bowel that required small bowel resection.2 These complications further emphasize the need to proceed immediately with surgery if a paraduodenal hernia is suspected.

Conclusion

This rare cause of bowel obstruction was documented in order to emphasize the importance of having a high clinical suspicion for a paraduodenal hernia. This particular patient with no history of abdominal surgeries had previously dealt with bowel obstruction and would likely have this complication again without surgical intervention. Patients with paraduodenal hernias also are at risk for bowel ischemia, other high-risk complications, and even death.5 Although a CT scan provided information about an approximate location of the obstruction, laparoscopy confirmed the diagnosis. Going into the operation with paraduodenal hernia in the differential allowed the surgeon to be prepared for the appropriate anatomy involved with this procedure to minimize damage to important structures, such as the superior mesenteric artery and its branches.

1. Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

2. Fukada T, Mukai H, Shimamura F, Furukawa T, Miyazaki M. A causal relationship between right paraduodenal hernia and superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:159.

3. Skandalakis JE. Peritoneum, omenta, and internal hernias. In: Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, eds. Skandalakis Surgical Anatomy: The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. 1st ed. Athens, Greece: Paschalidis Medical Publications; 2004:chap 10.

4. Papaziogas B, Souparis A, Makris J, Alexandrakis A, Papaziogas T. Surgical images: soft tissue. Right paraduodenal hernia. Can J Surg. 2004;47(3):195-196.

5. Manfredelli S, Andrea Z, Stefano P, et al. Rare small bowel obstruction: right paraduodenal hernia. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(4):412-415.

1. Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

2. Fukada T, Mukai H, Shimamura F, Furukawa T, Miyazaki M. A causal relationship between right paraduodenal hernia and superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:159.

3. Skandalakis JE. Peritoneum, omenta, and internal hernias. In: Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, eds. Skandalakis Surgical Anatomy: The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. 1st ed. Athens, Greece: Paschalidis Medical Publications; 2004:chap 10.

4. Papaziogas B, Souparis A, Makris J, Alexandrakis A, Papaziogas T. Surgical images: soft tissue. Right paraduodenal hernia. Can J Surg. 2004;47(3):195-196.

5. Manfredelli S, Andrea Z, Stefano P, et al. Rare small bowel obstruction: right paraduodenal hernia. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(4):412-415.

Improving Access to Care and Patient Satisfaction With Disease- Specific Colorectal Cancer Navigation

Purpose: Quality improvement project to decrease duration from diagnosis to clinic visit and definitive therapy while improving patient satisfaction within the healthcare system.

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of death in the United States. VISN Quality, Safety & Value standards were set with objective for all patients with a CRC diagnosis to be seen in a general or colorectal cancer surgery clinic within 30 days. The healthcare system provides oncology care to a large geographic region. The healthcare system instituted CRCspecific navigation in 2016.

Methods: Time from pathologic diagnosis of CRC to initial surgical oncology and/or medical oncology clinic visit was collected from 2013 to 2016 using the Cancer Data Management Program. Pathologic diagnosis was defined as the date when the pathology report was signed. All CRC stages (I-IV) were included, as were inpatients and outpatients. Patient satisfaction surveys were mailed to applicable patients over 3-month period to gauge their experience with nurse navigation. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze data.

Results: The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) time to start of therapy decreased by 12 days between 2016 (36 ± 19 days, n = 22) and 2013 to 2015 (48 ± 32, n = 55) though this did not reach statistical significance (P = .16). Similarly, the mean ± SD time to clinic decreased by 7 days from 2016 (11 ± 10 days) compared with 2013 to 2016 (18 ± 19) (P = .16). The percentage of patients seen within 30 days increased after navigation (95%) compared with prior (85%). Moreover, no patients postnavigation waited 90 or more days to receive therapy compared to 11% before navigation. Patient satisfaction data will be presented.

Conclusions: The implementation of nurse navigation was associated with decrease in mean time to clinic visit, mean time to treatment, and decreased outliers of prolonged time to treatment, though the study’s power was limited to a small sample size. We encourage further investigations into how nurse navigation can be used to improve Veterans’ cancer outcomes.

Purpose: Quality improvement project to decrease duration from diagnosis to clinic visit and definitive therapy while improving patient satisfaction within the healthcare system.

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of death in the United States. VISN Quality, Safety & Value standards were set with objective for all patients with a CRC diagnosis to be seen in a general or colorectal cancer surgery clinic within 30 days. The healthcare system provides oncology care to a large geographic region. The healthcare system instituted CRCspecific navigation in 2016.

Methods: Time from pathologic diagnosis of CRC to initial surgical oncology and/or medical oncology clinic visit was collected from 2013 to 2016 using the Cancer Data Management Program. Pathologic diagnosis was defined as the date when the pathology report was signed. All CRC stages (I-IV) were included, as were inpatients and outpatients. Patient satisfaction surveys were mailed to applicable patients over 3-month period to gauge their experience with nurse navigation. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze data.

Results: The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) time to start of therapy decreased by 12 days between 2016 (36 ± 19 days, n = 22) and 2013 to 2015 (48 ± 32, n = 55) though this did not reach statistical significance (P = .16). Similarly, the mean ± SD time to clinic decreased by 7 days from 2016 (11 ± 10 days) compared with 2013 to 2016 (18 ± 19) (P = .16). The percentage of patients seen within 30 days increased after navigation (95%) compared with prior (85%). Moreover, no patients postnavigation waited 90 or more days to receive therapy compared to 11% before navigation. Patient satisfaction data will be presented.

Conclusions: The implementation of nurse navigation was associated with decrease in mean time to clinic visit, mean time to treatment, and decreased outliers of prolonged time to treatment, though the study’s power was limited to a small sample size. We encourage further investigations into how nurse navigation can be used to improve Veterans’ cancer outcomes.

Purpose: Quality improvement project to decrease duration from diagnosis to clinic visit and definitive therapy while improving patient satisfaction within the healthcare system.

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of death in the United States. VISN Quality, Safety & Value standards were set with objective for all patients with a CRC diagnosis to be seen in a general or colorectal cancer surgery clinic within 30 days. The healthcare system provides oncology care to a large geographic region. The healthcare system instituted CRCspecific navigation in 2016.

Methods: Time from pathologic diagnosis of CRC to initial surgical oncology and/or medical oncology clinic visit was collected from 2013 to 2016 using the Cancer Data Management Program. Pathologic diagnosis was defined as the date when the pathology report was signed. All CRC stages (I-IV) were included, as were inpatients and outpatients. Patient satisfaction surveys were mailed to applicable patients over 3-month period to gauge their experience with nurse navigation. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze data.

Results: The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) time to start of therapy decreased by 12 days between 2016 (36 ± 19 days, n = 22) and 2013 to 2015 (48 ± 32, n = 55) though this did not reach statistical significance (P = .16). Similarly, the mean ± SD time to clinic decreased by 7 days from 2016 (11 ± 10 days) compared with 2013 to 2016 (18 ± 19) (P = .16). The percentage of patients seen within 30 days increased after navigation (95%) compared with prior (85%). Moreover, no patients postnavigation waited 90 or more days to receive therapy compared to 11% before navigation. Patient satisfaction data will be presented.

Conclusions: The implementation of nurse navigation was associated with decrease in mean time to clinic visit, mean time to treatment, and decreased outliers of prolonged time to treatment, though the study’s power was limited to a small sample size. We encourage further investigations into how nurse navigation can be used to improve Veterans’ cancer outcomes.

Treatment Rates and Outcomes for Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer at a Single VA Hospital: An Exploratory Analysis

Background: Under-treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) continues to be a problem. Recent data presented at AVAHO 2016 (poster 21) by Ahmed et al showed patients in the VA system with MPC had treatment rates substantially lower than ACOS certified hospitals (41.5% vs 53.2%).

Objective: We aim to determine the treatment rate of MPC at the Stratton VA Medical Center (SVAMC), an ACOS-certified VA hospital, compare it with the national VAH and ACOS hospitals, and conduct a root-cause analysis for this under-treatment.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of MPC patients at the SVAMC between January 2010 and December 2016. All patients who presented to SVAMC with biopsy-proven MPC were included. Charts were reviewed to determine whether patients received systemic therapy, the specific type of therapy each patient received, survival rates, and the stated reason for not receiving chemotherapy.

Results: Thirty-five patients were identified to have had likely MPC. Three were excluded as they did not have a tissue biopsy. Of the remaining 32, 19 (59.4%) received systemic therapy. Thirteen (40.6%) were found not to have been treated with systemic chemotherapy. The stated reasons for non-treatment were low functional status (8 patients, 61.5%), patient refusal (3 patients, 23.1%) and other reasons (2 patients, 15.4%). Median survival of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 233 days in the Chemotherapy group vs 60 days in the group that did not receive systemic therapy (P = .012 for mean survival). The treatment rate for MPC at SVAMC was determined to be 59.4%, which is higher than both VAH (41.5%) and ACOS certified hospitals (53.2%).

Conclusions: Our study showed that treatment rates for MPC at the SVAMC was higher than national average VA data. The vast majority of non-treatments (patient refusal, diminished ECOG status) were appropriate and in line with NCCN guidelines. National averaged data may mask regional trends and heterogeneity in practice in various VA centers. Further studies should explore this heterogeneity and identify possible causes.

Background: Under-treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) continues to be a problem. Recent data presented at AVAHO 2016 (poster 21) by Ahmed et al showed patients in the VA system with MPC had treatment rates substantially lower than ACOS certified hospitals (41.5% vs 53.2%).

Objective: We aim to determine the treatment rate of MPC at the Stratton VA Medical Center (SVAMC), an ACOS-certified VA hospital, compare it with the national VAH and ACOS hospitals, and conduct a root-cause analysis for this under-treatment.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of MPC patients at the SVAMC between January 2010 and December 2016. All patients who presented to SVAMC with biopsy-proven MPC were included. Charts were reviewed to determine whether patients received systemic therapy, the specific type of therapy each patient received, survival rates, and the stated reason for not receiving chemotherapy.

Results: Thirty-five patients were identified to have had likely MPC. Three were excluded as they did not have a tissue biopsy. Of the remaining 32, 19 (59.4%) received systemic therapy. Thirteen (40.6%) were found not to have been treated with systemic chemotherapy. The stated reasons for non-treatment were low functional status (8 patients, 61.5%), patient refusal (3 patients, 23.1%) and other reasons (2 patients, 15.4%). Median survival of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 233 days in the Chemotherapy group vs 60 days in the group that did not receive systemic therapy (P = .012 for mean survival). The treatment rate for MPC at SVAMC was determined to be 59.4%, which is higher than both VAH (41.5%) and ACOS certified hospitals (53.2%).

Conclusions: Our study showed that treatment rates for MPC at the SVAMC was higher than national average VA data. The vast majority of non-treatments (patient refusal, diminished ECOG status) were appropriate and in line with NCCN guidelines. National averaged data may mask regional trends and heterogeneity in practice in various VA centers. Further studies should explore this heterogeneity and identify possible causes.

Background: Under-treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) continues to be a problem. Recent data presented at AVAHO 2016 (poster 21) by Ahmed et al showed patients in the VA system with MPC had treatment rates substantially lower than ACOS certified hospitals (41.5% vs 53.2%).

Objective: We aim to determine the treatment rate of MPC at the Stratton VA Medical Center (SVAMC), an ACOS-certified VA hospital, compare it with the national VAH and ACOS hospitals, and conduct a root-cause analysis for this under-treatment.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of MPC patients at the SVAMC between January 2010 and December 2016. All patients who presented to SVAMC with biopsy-proven MPC were included. Charts were reviewed to determine whether patients received systemic therapy, the specific type of therapy each patient received, survival rates, and the stated reason for not receiving chemotherapy.

Results: Thirty-five patients were identified to have had likely MPC. Three were excluded as they did not have a tissue biopsy. Of the remaining 32, 19 (59.4%) received systemic therapy. Thirteen (40.6%) were found not to have been treated with systemic chemotherapy. The stated reasons for non-treatment were low functional status (8 patients, 61.5%), patient refusal (3 patients, 23.1%) and other reasons (2 patients, 15.4%). Median survival of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 233 days in the Chemotherapy group vs 60 days in the group that did not receive systemic therapy (P = .012 for mean survival). The treatment rate for MPC at SVAMC was determined to be 59.4%, which is higher than both VAH (41.5%) and ACOS certified hospitals (53.2%).

Conclusions: Our study showed that treatment rates for MPC at the SVAMC was higher than national average VA data. The vast majority of non-treatments (patient refusal, diminished ECOG status) were appropriate and in line with NCCN guidelines. National averaged data may mask regional trends and heterogeneity in practice in various VA centers. Further studies should explore this heterogeneity and identify possible causes.

Staging and Survival of Colorectal Cancer in Octogenarians: Nationwide Study of U.S. Veterans

Background: USPSTF recommends against continuing screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) past 75 years in adequately screened individuals. Research has shown that onetime screening for elderly who have never been screened appears to be cost effective until 86 years of age. Survival and staging data that compare elderly vs younger populations has not been published.