User login

Aortic aneurysm: Fluoroquinolones, genetic counseling

To the Editor: The review of thoracic aortic aneurysm by Cikach et al1 was excellent. However, we noted that referral for clinical genetic counseling and testing is suggested only if 1 or more first-degree relatives have aneurysmal disease.

Absence of a family history does not rule out syndromic aortopathy, which can occur de novo. In addition, a clinical diagnosis of syndromic aortopathy can be made on the basis of physical features that can be very subtle, such as pectus deformities, scoliosis, dolichostenomelia, joint hypermobility or contractures, craniofacial features, or skin fragility.2

Genetic counseling is paramount even if molecular testing is negative or inconclusive, which can occur in more than 50% of patients referred.3 Clinical genetic evaluation would also facilitate testing for other family members who may be affected, and would help to coordinate care for nonvascular conditions that may be associated with the syndrome.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. OMIM. Online mendelian inheritance in man. https://omim.org. Accessed July 31, 2018.

- Mazine A, Moryousef-Abitbol JH, Faghfoury H, Meza JM, Morel C, Ouzounian M. Yield of genetic testing in patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(11):2005. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(17)35394-9

To the Editor: The review of thoracic aortic aneurysm by Cikach et al1 was excellent. However, we noted that referral for clinical genetic counseling and testing is suggested only if 1 or more first-degree relatives have aneurysmal disease.

Absence of a family history does not rule out syndromic aortopathy, which can occur de novo. In addition, a clinical diagnosis of syndromic aortopathy can be made on the basis of physical features that can be very subtle, such as pectus deformities, scoliosis, dolichostenomelia, joint hypermobility or contractures, craniofacial features, or skin fragility.2

Genetic counseling is paramount even if molecular testing is negative or inconclusive, which can occur in more than 50% of patients referred.3 Clinical genetic evaluation would also facilitate testing for other family members who may be affected, and would help to coordinate care for nonvascular conditions that may be associated with the syndrome.

To the Editor: The review of thoracic aortic aneurysm by Cikach et al1 was excellent. However, we noted that referral for clinical genetic counseling and testing is suggested only if 1 or more first-degree relatives have aneurysmal disease.

Absence of a family history does not rule out syndromic aortopathy, which can occur de novo. In addition, a clinical diagnosis of syndromic aortopathy can be made on the basis of physical features that can be very subtle, such as pectus deformities, scoliosis, dolichostenomelia, joint hypermobility or contractures, craniofacial features, or skin fragility.2

Genetic counseling is paramount even if molecular testing is negative or inconclusive, which can occur in more than 50% of patients referred.3 Clinical genetic evaluation would also facilitate testing for other family members who may be affected, and would help to coordinate care for nonvascular conditions that may be associated with the syndrome.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. OMIM. Online mendelian inheritance in man. https://omim.org. Accessed July 31, 2018.

- Mazine A, Moryousef-Abitbol JH, Faghfoury H, Meza JM, Morel C, Ouzounian M. Yield of genetic testing in patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(11):2005. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(17)35394-9

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. OMIM. Online mendelian inheritance in man. https://omim.org. Accessed July 31, 2018.

- Mazine A, Moryousef-Abitbol JH, Faghfoury H, Meza JM, Morel C, Ouzounian M. Yield of genetic testing in patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(11):2005. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(17)35394-9

In reply: Aortic aneurysm: Fluoroquinolones, genetic counseling

In Reply: We thank Drs. Goldstein and Mascitelli for their comments regarding fluoroquinolones and thoracic aortic aneurysms. We acknowledge that fluoroquinolones (particularly ciprofloxacin) have been associated with a risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection based on large observational studies from Taiwan, Canada, and Sweden. Although all of the studies have shown an association between ciprofloxacin and aortic aneurysm, the causative role is not well established. In addition, the numbers of events were very small in these large cohorts of patients. In our large tertiary care practice at Cleveland Clinic, we have very few patients with aortic aneurysm or dissection who have used fluoroquinolones.

We recognize the association; however, our paper was intended to emphasize the more common causes and treatment options that primary care physicians are likely to encounter in routine practice.

We also thank Drs. Ayoubieh and MacCarrick for their comments about genetic counseling. We agree that genetic counseling is important, as is a detailed physical examination for subtle features of genetically mediated aortic aneurysm. In fact, we incorporate the physical examination when patients are seen at our aortic center so as to recognize the physical features. We do routinely recommend screening of first-degree relatives even without significant family history on an individual basis and make appropriate referrals for other conditions that can be seen in these patients. Our article, however, is primarily intended to emphasize the importance of referring these patients for more-focused care at a specialized center, where we incorporate all of the suggestions that were made.

In Reply: We thank Drs. Goldstein and Mascitelli for their comments regarding fluoroquinolones and thoracic aortic aneurysms. We acknowledge that fluoroquinolones (particularly ciprofloxacin) have been associated with a risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection based on large observational studies from Taiwan, Canada, and Sweden. Although all of the studies have shown an association between ciprofloxacin and aortic aneurysm, the causative role is not well established. In addition, the numbers of events were very small in these large cohorts of patients. In our large tertiary care practice at Cleveland Clinic, we have very few patients with aortic aneurysm or dissection who have used fluoroquinolones.

We recognize the association; however, our paper was intended to emphasize the more common causes and treatment options that primary care physicians are likely to encounter in routine practice.

We also thank Drs. Ayoubieh and MacCarrick for their comments about genetic counseling. We agree that genetic counseling is important, as is a detailed physical examination for subtle features of genetically mediated aortic aneurysm. In fact, we incorporate the physical examination when patients are seen at our aortic center so as to recognize the physical features. We do routinely recommend screening of first-degree relatives even without significant family history on an individual basis and make appropriate referrals for other conditions that can be seen in these patients. Our article, however, is primarily intended to emphasize the importance of referring these patients for more-focused care at a specialized center, where we incorporate all of the suggestions that were made.

In Reply: We thank Drs. Goldstein and Mascitelli for their comments regarding fluoroquinolones and thoracic aortic aneurysms. We acknowledge that fluoroquinolones (particularly ciprofloxacin) have been associated with a risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection based on large observational studies from Taiwan, Canada, and Sweden. Although all of the studies have shown an association between ciprofloxacin and aortic aneurysm, the causative role is not well established. In addition, the numbers of events were very small in these large cohorts of patients. In our large tertiary care practice at Cleveland Clinic, we have very few patients with aortic aneurysm or dissection who have used fluoroquinolones.

We recognize the association; however, our paper was intended to emphasize the more common causes and treatment options that primary care physicians are likely to encounter in routine practice.

We also thank Drs. Ayoubieh and MacCarrick for their comments about genetic counseling. We agree that genetic counseling is important, as is a detailed physical examination for subtle features of genetically mediated aortic aneurysm. In fact, we incorporate the physical examination when patients are seen at our aortic center so as to recognize the physical features. We do routinely recommend screening of first-degree relatives even without significant family history on an individual basis and make appropriate referrals for other conditions that can be seen in these patients. Our article, however, is primarily intended to emphasize the importance of referring these patients for more-focused care at a specialized center, where we incorporate all of the suggestions that were made.

Thoracic aortic aneurysm: How to counsel, when to refer

Thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) needs to be detected, monitored, and managed in a timely manner to prevent a serious consequence such as acute dissection or rupture. But only about 5% of patients experience symptoms before an acute event occurs, and for the other 95% the first “symptom” is often death.1 Most cases are detected either incidentally with echocardiography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during workup for another condition. Patients may also be diagnosed during workup of a murmur or after a family member is found to have an aneurysm. Therefore, its true incidence is difficult to determine.2

With these facts in mind, how would you manage the following 2 cases?

Case 1: Bicuspid aortic valve, ascending aortic aneurysm

A 45-year-old man with stage 1 hypertension presents for evaluation of a bicuspid aortic valve and ascending aortic aneurysm. He has several first-degree relatives with similar conditions, and his brother recently underwent elective aortic repair. At the urging of his primary care physician, he underwent screening echocardiography, which demonstrated a “dilated root and ascending aorta” 4.6 cm in diameter. He presents today to discuss management options and how the aneurysm could affect his everyday life.

Case 2: Marfan syndrome in a young woman

A 24-year-old woman with Marfan syndrome diagnosed in adolescence presents for annual follow-up. She has many family members with the same condition, and several have undergone prophylactic aortic root repair. Her aortic root has been monitored annually for progression of dilation, and today it is 4.6 cm in diameter, a 3-mm increase from the last measurement. She has grade 2+ aortic insufficiency (on a scale of 1+ to 4+) based on echocardiography, but she has no symptoms. She is curious about what size her aortic root will need to reach for surgery to be considered.

LIKELY UNDERDETECTED

TAA is being detected more often than in the past thanks to better detection methods and heightened awareness among physicians and patients. While an incidence rate of 10.4 per 100,000 patient-years is often cited,3 this figure likely underestimates the true incidence of this clinically silent condition. The most robust data come from studies based on in-hospital diagnostic codes coupled with data from autopsies for out-of-hospital deaths.

Olsson et al,4 in a 2016 study in Sweden, found the incidence of TAA and aortic dissection to be 16.3 per 100,000 per year for men and 9.1 per 100,000 per year for women.

Clouse et al5 reported the incidence of thoracic aortic dissection as 3.5 per 100,000 patient-years, and the same figure for thoracic aortic rupture.

Aneurysmal disease accounts for 52,000 deaths per year in the United States, making it the 19th most common cause of death.6 These figures are likely lower than the true mortality rate for this condition, given that aortic dissection is often mistaken for acute myocardial infarction or other acute event if an autopsy is not done to confirm the cause of death.7

RISK FACTORS FOR THORACIC AORTIC ANEURYSM

Risk factors for TAA include genetic conditions that lead to aortic medial weakness or destruction such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome and Marfan syndrome.2 In addition, family history is important even in the absence of known genetic mutations. Other risk factors include conditions that increase aortic wall stress, such as hypertension, cocaine abuse, extreme weightlifting, trauma, and aortic coarctation.2

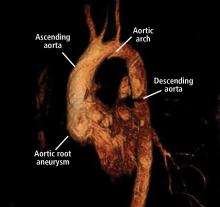

DIAMETER INCREASES WITH AGE, BODY SURFACE AREA

Normal dimensions for the aortic segments differ depending on age, sex, and body surface area.8,44,45 The size of the aortic root may also vary depending on how it is measured, due to the root’s trefoil shape. Measured sinus to sinus, the root is larger than when measured sinus to commissure on CT angiography or cardiac MRI. It is also larger when measured leading edge to leading edge than inner edge to inner edge on echocardiography.10

TAA is defined as an aortic diameter at least 50% greater than the upper limit of normal.8

Geometric changes in the curvature of the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending thoracic aorta can occur as the result of hypertension, atherosclerosis, or connective tissue disease.

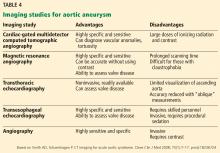

HOW IS TAA DIAGNOSED?

Imaging tests

It is particularly important to obtain a gated CTA image in patients with aortic root aneurysm to avoid motion artifact and possible erroneous measurements. Gated CTA is done with electrocardiographic synchronization and allows for image processing to correct for cardiac motion.

HOW IS TAA CLASSIFIED?

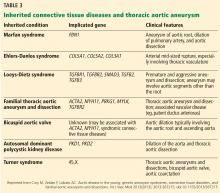

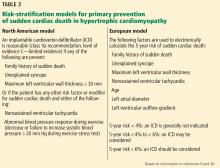

TAA can be caused by a variety of inherited and sporadic conditions. These differences in pathogenesis lend themselves to classification of aneurysms into groups. Table 3 highlights the most common conditions associated with TAA.13

Bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy

From 1% to 2% of people have a bicuspid aortic valve, with a 3-to-1 male predominance.14,15 Aortic dilation occurs in 35% to 80% of people who have a bicuspid aortic valve, conferring a risk of dissection 8 times higher than in the general population.16–18

The pathogenic mechanisms that lead to this condition are widely debated, although a combination of genetic defects leading to intrinsic weakening of the aortic wall and hemodynamic effects likely contribute.19 Evidence of hemodynamic contributions to aortic dilation comes from findings that particular patterns of cusp fusion of the bicuspid aortic valve result in changes in transvalvular flow, placing more stress on specific regions of the ascending aorta.20,21 These hemodynamic alterations result in patterns of aortic dilation that depend on cusp fusion and the presence of valvular disease.

Multiple small studies found that replacing bicuspid aortic valves reduced the rate of aortic dilation, suggesting that hemodynamic factors may play a larger role than intrinsic wall properties in genetically susceptible individuals.22,23 However, larger studies are needed before any definitive conclusions can be made.

HOW IS ANEURYSM MANAGED ON AN OUTPATIENT BASIS?

Patients with a new diagnosis of TAA should be referred to a cardiologist with expertise in managing aortic disease or to a cardiac surgeon specializing in aortic surgery, depending on the initial size of the aneurysm.

Control blood pressure with beta-blockers

Medical management for patients with TAA has historically been limited to strict blood pressure control aimed at reducing aortic wall stress, mainly with beta-blockers.

Are angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) beneficial? Studies in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome revealed that the ARB losartan attenuated aortic root growth.24 The results of early, small studies in humans were promising,25–27 but larger randomized trials have shown no advantage of losartan over beta-blockers in slowing aortic root growth.28 These negative results led many to question the effectiveness of losartan, although some point out that no studies have shown even beta-blockers to be beneficial in reducing the clinical end points of death or dissection.29 On the other hand, patients with certain FBN1 mutations respond more readily than others to losartan.30 Additional clinical trials of ARBs in Marfan syndrome are ongoing.

Current guidelines recommend stringent blood pressure control and smoking cessation for patients with a small aneurysm not requiring surgery and for those who are considered unsuitable for surgical or percutaneous intervention (level of evidence C, the lowest).2 For patients with TAA, it is considered reasonable to give beta-blockers. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or ARBs may be used in combination with beta-blockers, titrated to the lowest tolerable blood pressure without adverse effects (level of evidence B).2

The recommended target blood pressure is less than 140/90 mm Hg, or 130/80 mm Hg in those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease (level of evidence B).2 However, we recommend more stringent blood pressure control: ie, less than 130/80 mm Hg for all patients with aortic aneurysm and a heart rate goal of 70 beats per minute or less, as tolerated.

Activity restriction

Activity restrictions for patients with TAA are largely based on theory, and certain activities may require more modification than others. For example, heavy lifting should be discouraged, as it may increase blood pressure significantly for short periods of time.2,31 The increased wall stress, in theory, could initiate dissection or rupture. However, moderate-intensity aerobic activity is rarely associated with significant elevations in blood pressure and should be encouraged. Stressful emotional states have been anecdotally associated with aortic dissection; thus, measures to reduce stress may offer some benefit.31

Our recommendations. While there are no published guidelines regarding activity restrictions in patients with TAA, we use a graded approach based on aortic diameter:

- 4.0 to 4.4 cm—lift no more than 75 pounds

- 4.5 to 5 cm—lift no more than 50 pounds

- 5 cm—lift no more than 25 pounds.

We also recommend not lifting anything heavier than half of one’s body weight and to avoid breath-holding or performing the Valsalva maneuver while lifting. Although these recommendations are somewhat arbitrary, based on theory and a large clinical experience at our aortic center, they seem reasonable and practical.

Activity restrictions should be stringent and individualized in patients with Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to increased risk of dissection or rupture even if the aorta is normal in size.

We sometimes recommend exercise stress testing to assess the heart rate and blood pressure response to exercise, and we are developing research protocols to help tailor activity recommendations.

WHEN SHOULD A PATIENT BE REFERRED?

To a cardiologist at the time of diagnosis

As soon as TAA is diagnosed, the patient should be referred to a cardiologist who has special interest in aortic disease. This will allow for appropriate and timely decisions about medical management, imaging, follow-up, and referral to surgery. Additional recommendations for screening of family members and referral to clinical geneticists can be discussed at this juncture. Activity restrictions should be reviewed at the initial evaluation.

To a surgeon relatively early

Size thresholds for surgical intervention are discussed below, but one should not wait until these thresholds are reached to send the patient for surgical consultation. It is beneficial to the state of mind of a potential surgical candidate to have early discussions pertaining to the types of operations available, their outcomes, and associated risks and benefits. If a patient’s aortic size remains stable over time, he or she may be followed by the cardiologist until significant size or growth has been documented, at which time the patient and surgeon can reconvene to discuss options for definitive treatment.

To a clinical geneticist

If 1 or more first-degree relatives of a patient with TAA or dissection are found to have aneurysmal disease, referral to a clinical geneticist is very important for genetic testing of multiple genes that have been implicated in thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection.

WHEN SHOULD TAA BE REPAIRED?

Surgery to prevent rupture or dissection remains the definitive treatment of TAA when size thresholds are reached, and symptomatic aneurysm should be operated on regardless of the size. However, rarely are thoracic aneurysms symptomatic unless they rupture or dissect. The size criteria are based on underlying genetic etiology if known and on the behavior and natural course of TAA.

Size and other factors

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s clinical scenario, family history, and estimated risk of rupture or dissection, balanced against the individual center’s outcomes of elective aortic replacement.32 For example, young and otherwise healthy patients with TAA and a family history of aortic dissection (who may be more likely to have connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, or vascular Ehler-Danlos syndrome) may elect to undergo repair when the aneurysm reaches or nearly reaches the diameter of that of the family member’s aorta when dissection occurred.2 On the other hand, TAA of degenerative etiology (eg, related to smoking or hypertension) measuring less than 5.5 cm in an older patient with comorbidities poses a lower risk of a catastrophic event such as dissection or rupture than the risk of surgery.11

Thresholds for surgery. Once the diameter of the ascending aorta reaches 6 cm, the likelihood of an acute dissection is 31%.11 A similar threshold is reached for the descending aorta at a size of 7 cm.11 Therefore, to avoid high-risk emergency surgery on an acutely dissected aorta, surgery on an ascending aortic aneurysm of degenerative etiology is usually suggested when the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm or a documented growth rate greater than 0.5 cm/year.2,33

Additionally, in patients already undergoing surgery for valvular or coronary disease, prophylactic aortic replacement is recommended if the ascending aorta is larger than 4.5 cm. The threshold for intervention is lower in patients with connective tissue disease (> 5.0 cm for Marfan syndrome, 4.4–4.6 cm for Loeys-Dietz syndrome).2,33

Observational studies suggest that the risk of aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy is low overall, though significantly greater than in the general population.18,34,35 These findings led to changes in the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on valvular heart disease,36 suggesting a surgical threshold of 5.5 cm in the absence of significant valve disease or family history of dissection of an aorta of smaller diameter.

A 2015 study of dissection risk in patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy by our group found a dramatic increase in risk of aortic dissection for ascending aortic diameters greater than 5.3 cm, and a gradual increase in risk for aortic root diameters greater than 5.0 cm.37 In addition, a near-constant 3% to 4% risk of dissection was present for aortic diameters ranging from 4.7 cm to 5.0 cm, revealing that watchful waiting carries its own inherent risks.37 In our surgical experience with this population, the hospital mortality rate and risk of stroke from aortic surgery were 0.25% and 0.75%, respectively.37 Thus, the decision to operate for aortic aneurysm in the setting of a bicuspid aortic valve should take into account patient-specific factors and institutional outcomes.

A statement of clarification in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines was published in 2015, recommending surgery for patients with an aortic diameter of 5.0 cm or greater if the patient is at low risk and the surgery is performed by an experienced surgical team at a center with established surgical expertise in this condition.38 However, current recommendations are for surgery at 5.5 cm if the above conditions are not met.

Ratio of aortic cross-sectional area to height

Although size alone has long been used to guide surgical intervention, a recent review from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection revealed that 59% of patients suffered aortic dissection at diameters less than 5.5 cm, and that patients with certain connective tissue diseases such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome or familial thoracic aneurysm and dissection had a documented propensity for dissection at smaller diameters.39–41

Size indices such as the aortic cross-sectional area indexed to height have been implemented in guidelines for certain patient populations (eg, 10 cm2/m in Marfan syndrome) and provide better risk stratification than size cutoffs alone.2,42

The ratio of aortic cross-sectional area to the patient’s height has also been applied to patients with bicuspid aortic valve-associated aortopathy and to those with a dilated aorta and a tricuspid aortic valve.43,44 Notably, a ratio greater than 10 cm2/m has been associated with aortic dissection in these groups, and this cutoff provides better stratification for prediction of death than traditional size metrics.27,28

HOW SHOULD PATIENTS BE SCREENED? WHAT FOLLOW-UP IS NECESSARY?

Initial screening and follow-up

Follow-up of TAA depends on the initial aortic size or rate of growth, or both. For patients presenting for the first time with TAA, it is reasonable to obtain definitive aortic imaging with CT or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), then to repeat imaging at 6 months to document stability. If the aortic dimensions remain stable, then annual follow-up with CT or MRA is reasonable.2

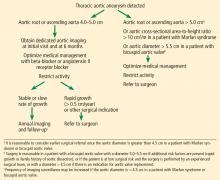

Our flow chart of initial screening and follow-up is shown in Figure 5.

Screening of family members

In our center, we routinely recommend screening of all first-degree relatives of patients with TAA. Aortic imaging with echocardiography plus CT or MRI should be considered to detect asymptomatic disease.2 In patients with a strong family history (ie, multiple relatives affected with aortic aneurysm, dissection, or sudden cardiac death), genetic screening and testing for known mutations are recommended for the patient as well as for the family members.

If a mutation is identified in a family, then first-degree relatives should undergo genetic screening for the mutation and aortic imaging.2 Imaging in second-degree relatives may also be considered if one or more first-degree relatives are found to have aortic dilation.2

We recommend similar screening of first-degree family members of patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy. In patients with young children, we recommend obtaining an echocardiogram of the child to look for a bicuspid aortic valve or aortic dilation. If an abnormality is detected or suspected, dedicated imaging with MRA to assess aortic dimensions is warranted.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT WITH A BICUSPID AORTIC VALVE

Our patient with a bicuspid aortic valve had a 4.6-cm root, an ascending aortic aneurysm, and several affected family members.

We would obtain dedicated aortic imaging at this patient’s initial visit with either gated CT with contrast or MRA, and we would obtain a cardioaortic surgery consult. We would repeat these studies at a follow-up visit 6 months later to detect any aortic growth compared with initial studies, and follow up annually thereafter. Echocardiography can also be done at the initial visit to determine if valvular disease is present that may influence clinical decisions.

Surgery would likely be recommended once the root reached a maximum area-to-height ratio greater than 10 cm2/m, or if the valve became severely dysfunctional during follow-up.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT WITH MARFAN SYNDROME

The young woman with Marfan syndrome has a 4.6-cm aortic root aneurysm and 2+ aortic insufficiency. Her question pertains to the threshold at which an operation would be considered. This question is complicated and is influenced by several concurrent clinical features in her presentation.

Starting with size criteria, patients with Marfan syndrome should be considered for elective aortic root repair at a diameter greater than 5 cm. However, an aortic cross-sectional area-to-height ratio greater than 10 cm2/m may provide a more robust metric for clinical decision-making than aortic diameter alone. Additional factors such as degree of aortic insufficiency and deleterious left ventricular remodeling may urge one to consider aortic root repair at a diameter of 4.5 cm.

These factors, including rate of growth and the surgeon’s assessment about his or her ability to preserve the aortic valve during repair, should be considered collectively in this scenario.

- Elefteriades JA, Farkas EA. Thoracic aortic aneurysm clinically pertinent controversies and uncertainties. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55(9):841–857. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.084

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease: executive summary. Anesth Analg 2010; 111(2):279–315. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181dd869b

- Clouse WD, Hallett JW Jr, Schaff HV, Gayari MM, Ilstrup DM, Melton LJ 3rd. Improved prognosis of thoracic aortic aneurysms: a population-based study. JAMA 1998; 280(22):1926–1929. pmid:9851478

- Olsson C, Thelin S, Ståhle E, Ekbom A, Granath F. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: increasing prevalence and improved outcomes reported in a nationwide population-based study of more than 14,000 cases from 1987 to 2002. Circulation 2006; 114(24):2611–2618. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630400

- Clouse WD, Hallett JW Jr, Schaff HV, et al. Acute aortic dissection: population-based incidence compared with degenerative aortic aneurysm rupture. Mayo Clin Proc 2004; 79(2):176–180. pmid:14959911

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. WISQARS leading causes of death reports, 1999 – 2007. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10.html. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- Hansen MS, Nogareda GJ, Hutchison SJ. Frequency of and inappropriate treatment of misdiagnosis of acute aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol 2007; 99(6):852–856. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.10.055

- Goldfinger JZ, Halperin JL, Marin ML, Stewart AS, Eagle KA, Fuster V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64(16):1725–1739. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.025

- Kumar V, Abbas A, Aster J. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2015.

- Wolak A, Gransar H, Thomson LE, et al. Aortic size assessment by noncontrast cardiac computed tomography: normal limits by age, gender, and body surface area. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2008; 1(2):200–209. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2007.11.005

- Elefteriades JA. Natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysms: indications for surgery, and surgical versus nonsurgical risks. Ann Thorac Surg 2002; 74(5):S1877–S1880; discussion S1892–S1898. pmid:12440685

- Smith AD, Schoenhagen P. CT imaging for acute aortic syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2008; 75(1):7–17. pmid:18236724

- Cury M, Zeidan F, Lobato AC. Aortic disease in the young: genetic aneurysm syndromes, connective tissue disorders, and familial aortic aneurysms and dissections. Int J Vasc Med 2013(2013); 2013:267215. doi:10.1155/2013/267215

- Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39(12):1890–1900. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01886-7

- Fedak PW, Verma S, David TE, Leask RL, Weisel RD, Butany J. Clinical and pathophysiological implications of a bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation 2002; 106(8):900–904. pmid:12186790

- Della Corte A, Bancone C, Quarto C, et al. Predictors of ascending aortic dilatation with bicuspid aortic valve: a wide spectrum of disease expression. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007; 31(3):397–405. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.12.006

- Jackson V, Petrini J, Caidahl K, et al. Bicuspid aortic valve leaflet morphology in relation to aortic root morphology: a study of 300 patients undergoing open-heart surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011; 40(3):e118–e124. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.04.014

- Michelena HI, Khanna AD, Mahoney D, et al. Incidence of aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. JAMA 2011; 306(10):1104–1112. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1286

- Verma S, Siu SC. Aortic dilatation in patients with bicuspid aortic valve. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(20):1920–1929. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1207059

- Barker AJ, Markl M, Bürk J, et al. Bicuspid aortic valve is associated with altered wall shear stress in the ascending aorta. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 5(4):457–466. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.973370

- Hope MD, Hope TA, Meadows AK, et al. Bicuspid aortic valve: four-dimensional MR evaluation of ascending aortic systolic flow patterns. Radiology 2010; 255(1):53–61. doi:10.1148/radiol.09091437

- Abdulkareem N, Soppa G, Jones S, Valencia O, Smelt J, Jahangiri M. Dilatation of the remaining aorta after aortic valve or aortic root replacement in patients with bicuspid aortic valve: a 5-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96(1):43–49. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.086

- Regeer MV, Versteegh MI, Klautz RJ, et al. Effect of aortic valve replacement on aortic root dilatation rate in patients with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valves. Ann Thorac Surg 2016; 102(6):1981–1987. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.05.038

- Habashi JP, Judge DP, Holm TM, et al. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science 2006; 312(5770):117–121. doi:10.1126/science.1124287

- Brooke BS, Habashi JP, Judge DP, Patel N, Loeys B, Dietz HC 3rd. Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(26):2787–2795. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706585

- Chiu HH, Wu MH, Wang JK, et al. Losartan added to ß-blockade therapy for aortic root dilation in Marfan syndrome: a randomized, open-label pilot study. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88(3):271–276. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.11.005

- Groenink M, den Hartog AW, Franken R, et al. Losartan reduces aortic dilatation rate in adults with Marfan syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J 2013; 34(45):3491–3500. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht334

- Lacro RV, Dietz HC, Sleeper LA, et al; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators. Atenolol versus losartan in children and young adults with Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(22):2061–2071. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1404731

- Ziganshin BA, Mukherjee SK, Elefteriades JA, et al. Atenolol versus losartan in Marfan’s syndrome (letters). N Engl J Med 2015; 372(10):977–981. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1500128

- Franken R, den Hartog AW, Radonic T, et al. Beneficial outcome of losartan therapy depends on type of FBN1 mutation in Marfan syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2015; 8(2):383–388. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000950

- Elefteriades JA. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: reading the enemy’s playbook. Curr Probl Cardiol 2008; 33(5):203–277. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2008.01.004

- Idrees JJ, Roselli EE, Lowry AM, et al. Outcomes after elective proximal aortic replacement: a matched comparison of isolated versus multicomponent operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2016; 101(6):2185–2192. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.12.026

- Hiratzka LF, Creager MA, Isselbacher EM, et al. Surgery for aortic dilatation in patients with bicuspid aortic valves: a statement of clarification from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016; 151(4):959–966. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.12.001

- Tzemos N, Therrien J, Yip J, et al. Outcomes in adults with bicuspid aortic valves. JAMA 2008; 300(11):1317–1325. doi:10.1001/jama.300.11.1317

- Davies RR, Goldstein LJ, Coady MA, et al. Yearly rupture or dissection rates for thoracic aortic aneurysms: simple prediction based on size. Ann Thorac Surg 2002; 73(1):17–28. pmid:11834007

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bono RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129(23):2440–2492. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000029

- Wojnarski CM, Svensson LG, Roselli EE, et al. Aortic dissection in patients with bicuspid aortic valve–associated aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 100(5):1666–1674. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.04.126

- Hiratzka LF, Creager MA, Isselbacher EM, et al. Surgery for aortic dilatation in patients with bicuspid aortic valves: a statement of clarification from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2016; 133(7):680–686. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000331

- Pape LA, Tsai TT, Isselbacher EM, et al; International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Investigators. Aortic diameter > or = 5.5 cm is not a good predictor of type A aortic dissection: observations from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation 2007; 116(10):1120–1127. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.702720

- Loeys BL, Schwarze U, Holm T, et al. Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-beta receptor. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(8):788–798. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055695

- Guo DC, Pannu H, Tran-Fadulu V, et al. Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) lead to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Nat Genet 2007; 39(12):1488–1493. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.6

- Svensson LG, Khitin L. Aortic cross-sectional area/height ratio timing of aortic surgery in asymptomatic patients with Marfan syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 123(2):360–361. pmid:11828302

- Svensson LG, Kim KH, Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM. Relationship of aortic cross-sectional area to height ratio and the risk of aortic dissection in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 126(3):892–893. pmid:14502185

- Masri A, Kalahasti V, Svensson LG, et al. Aortic cross-sectional area/height ratio and outcomes in patients with a trileaflet aortic valve and a dilated aorta. Circulation 2016; 134(22):1724–1737. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022995

Thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) needs to be detected, monitored, and managed in a timely manner to prevent a serious consequence such as acute dissection or rupture. But only about 5% of patients experience symptoms before an acute event occurs, and for the other 95% the first “symptom” is often death.1 Most cases are detected either incidentally with echocardiography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during workup for another condition. Patients may also be diagnosed during workup of a murmur or after a family member is found to have an aneurysm. Therefore, its true incidence is difficult to determine.2

With these facts in mind, how would you manage the following 2 cases?

Case 1: Bicuspid aortic valve, ascending aortic aneurysm

A 45-year-old man with stage 1 hypertension presents for evaluation of a bicuspid aortic valve and ascending aortic aneurysm. He has several first-degree relatives with similar conditions, and his brother recently underwent elective aortic repair. At the urging of his primary care physician, he underwent screening echocardiography, which demonstrated a “dilated root and ascending aorta” 4.6 cm in diameter. He presents today to discuss management options and how the aneurysm could affect his everyday life.

Case 2: Marfan syndrome in a young woman

A 24-year-old woman with Marfan syndrome diagnosed in adolescence presents for annual follow-up. She has many family members with the same condition, and several have undergone prophylactic aortic root repair. Her aortic root has been monitored annually for progression of dilation, and today it is 4.6 cm in diameter, a 3-mm increase from the last measurement. She has grade 2+ aortic insufficiency (on a scale of 1+ to 4+) based on echocardiography, but she has no symptoms. She is curious about what size her aortic root will need to reach for surgery to be considered.

LIKELY UNDERDETECTED

TAA is being detected more often than in the past thanks to better detection methods and heightened awareness among physicians and patients. While an incidence rate of 10.4 per 100,000 patient-years is often cited,3 this figure likely underestimates the true incidence of this clinically silent condition. The most robust data come from studies based on in-hospital diagnostic codes coupled with data from autopsies for out-of-hospital deaths.

Olsson et al,4 in a 2016 study in Sweden, found the incidence of TAA and aortic dissection to be 16.3 per 100,000 per year for men and 9.1 per 100,000 per year for women.

Clouse et al5 reported the incidence of thoracic aortic dissection as 3.5 per 100,000 patient-years, and the same figure for thoracic aortic rupture.

Aneurysmal disease accounts for 52,000 deaths per year in the United States, making it the 19th most common cause of death.6 These figures are likely lower than the true mortality rate for this condition, given that aortic dissection is often mistaken for acute myocardial infarction or other acute event if an autopsy is not done to confirm the cause of death.7

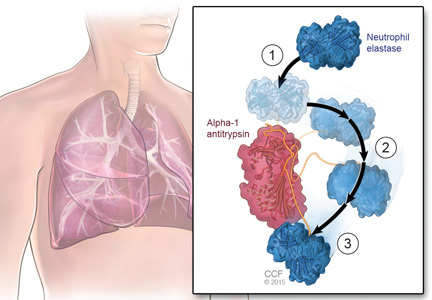

RISK FACTORS FOR THORACIC AORTIC ANEURYSM

Risk factors for TAA include genetic conditions that lead to aortic medial weakness or destruction such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome and Marfan syndrome.2 In addition, family history is important even in the absence of known genetic mutations. Other risk factors include conditions that increase aortic wall stress, such as hypertension, cocaine abuse, extreme weightlifting, trauma, and aortic coarctation.2

DIAMETER INCREASES WITH AGE, BODY SURFACE AREA

Normal dimensions for the aortic segments differ depending on age, sex, and body surface area.8,44,45 The size of the aortic root may also vary depending on how it is measured, due to the root’s trefoil shape. Measured sinus to sinus, the root is larger than when measured sinus to commissure on CT angiography or cardiac MRI. It is also larger when measured leading edge to leading edge than inner edge to inner edge on echocardiography.10

TAA is defined as an aortic diameter at least 50% greater than the upper limit of normal.8

Geometric changes in the curvature of the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending thoracic aorta can occur as the result of hypertension, atherosclerosis, or connective tissue disease.

HOW IS TAA DIAGNOSED?

Imaging tests

It is particularly important to obtain a gated CTA image in patients with aortic root aneurysm to avoid motion artifact and possible erroneous measurements. Gated CTA is done with electrocardiographic synchronization and allows for image processing to correct for cardiac motion.

HOW IS TAA CLASSIFIED?

TAA can be caused by a variety of inherited and sporadic conditions. These differences in pathogenesis lend themselves to classification of aneurysms into groups. Table 3 highlights the most common conditions associated with TAA.13

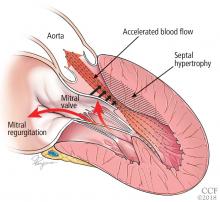

Bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy

From 1% to 2% of people have a bicuspid aortic valve, with a 3-to-1 male predominance.14,15 Aortic dilation occurs in 35% to 80% of people who have a bicuspid aortic valve, conferring a risk of dissection 8 times higher than in the general population.16–18

The pathogenic mechanisms that lead to this condition are widely debated, although a combination of genetic defects leading to intrinsic weakening of the aortic wall and hemodynamic effects likely contribute.19 Evidence of hemodynamic contributions to aortic dilation comes from findings that particular patterns of cusp fusion of the bicuspid aortic valve result in changes in transvalvular flow, placing more stress on specific regions of the ascending aorta.20,21 These hemodynamic alterations result in patterns of aortic dilation that depend on cusp fusion and the presence of valvular disease.

Multiple small studies found that replacing bicuspid aortic valves reduced the rate of aortic dilation, suggesting that hemodynamic factors may play a larger role than intrinsic wall properties in genetically susceptible individuals.22,23 However, larger studies are needed before any definitive conclusions can be made.

HOW IS ANEURYSM MANAGED ON AN OUTPATIENT BASIS?

Patients with a new diagnosis of TAA should be referred to a cardiologist with expertise in managing aortic disease or to a cardiac surgeon specializing in aortic surgery, depending on the initial size of the aneurysm.

Control blood pressure with beta-blockers

Medical management for patients with TAA has historically been limited to strict blood pressure control aimed at reducing aortic wall stress, mainly with beta-blockers.

Are angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) beneficial? Studies in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome revealed that the ARB losartan attenuated aortic root growth.24 The results of early, small studies in humans were promising,25–27 but larger randomized trials have shown no advantage of losartan over beta-blockers in slowing aortic root growth.28 These negative results led many to question the effectiveness of losartan, although some point out that no studies have shown even beta-blockers to be beneficial in reducing the clinical end points of death or dissection.29 On the other hand, patients with certain FBN1 mutations respond more readily than others to losartan.30 Additional clinical trials of ARBs in Marfan syndrome are ongoing.

Current guidelines recommend stringent blood pressure control and smoking cessation for patients with a small aneurysm not requiring surgery and for those who are considered unsuitable for surgical or percutaneous intervention (level of evidence C, the lowest).2 For patients with TAA, it is considered reasonable to give beta-blockers. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or ARBs may be used in combination with beta-blockers, titrated to the lowest tolerable blood pressure without adverse effects (level of evidence B).2

The recommended target blood pressure is less than 140/90 mm Hg, or 130/80 mm Hg in those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease (level of evidence B).2 However, we recommend more stringent blood pressure control: ie, less than 130/80 mm Hg for all patients with aortic aneurysm and a heart rate goal of 70 beats per minute or less, as tolerated.

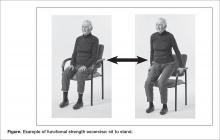

Activity restriction

Activity restrictions for patients with TAA are largely based on theory, and certain activities may require more modification than others. For example, heavy lifting should be discouraged, as it may increase blood pressure significantly for short periods of time.2,31 The increased wall stress, in theory, could initiate dissection or rupture. However, moderate-intensity aerobic activity is rarely associated with significant elevations in blood pressure and should be encouraged. Stressful emotional states have been anecdotally associated with aortic dissection; thus, measures to reduce stress may offer some benefit.31

Our recommendations. While there are no published guidelines regarding activity restrictions in patients with TAA, we use a graded approach based on aortic diameter:

- 4.0 to 4.4 cm—lift no more than 75 pounds

- 4.5 to 5 cm—lift no more than 50 pounds

- 5 cm—lift no more than 25 pounds.

We also recommend not lifting anything heavier than half of one’s body weight and to avoid breath-holding or performing the Valsalva maneuver while lifting. Although these recommendations are somewhat arbitrary, based on theory and a large clinical experience at our aortic center, they seem reasonable and practical.

Activity restrictions should be stringent and individualized in patients with Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to increased risk of dissection or rupture even if the aorta is normal in size.

We sometimes recommend exercise stress testing to assess the heart rate and blood pressure response to exercise, and we are developing research protocols to help tailor activity recommendations.

WHEN SHOULD A PATIENT BE REFERRED?

To a cardiologist at the time of diagnosis

As soon as TAA is diagnosed, the patient should be referred to a cardiologist who has special interest in aortic disease. This will allow for appropriate and timely decisions about medical management, imaging, follow-up, and referral to surgery. Additional recommendations for screening of family members and referral to clinical geneticists can be discussed at this juncture. Activity restrictions should be reviewed at the initial evaluation.

To a surgeon relatively early

Size thresholds for surgical intervention are discussed below, but one should not wait until these thresholds are reached to send the patient for surgical consultation. It is beneficial to the state of mind of a potential surgical candidate to have early discussions pertaining to the types of operations available, their outcomes, and associated risks and benefits. If a patient’s aortic size remains stable over time, he or she may be followed by the cardiologist until significant size or growth has been documented, at which time the patient and surgeon can reconvene to discuss options for definitive treatment.

To a clinical geneticist

If 1 or more first-degree relatives of a patient with TAA or dissection are found to have aneurysmal disease, referral to a clinical geneticist is very important for genetic testing of multiple genes that have been implicated in thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection.

WHEN SHOULD TAA BE REPAIRED?

Surgery to prevent rupture or dissection remains the definitive treatment of TAA when size thresholds are reached, and symptomatic aneurysm should be operated on regardless of the size. However, rarely are thoracic aneurysms symptomatic unless they rupture or dissect. The size criteria are based on underlying genetic etiology if known and on the behavior and natural course of TAA.

Size and other factors

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s clinical scenario, family history, and estimated risk of rupture or dissection, balanced against the individual center’s outcomes of elective aortic replacement.32 For example, young and otherwise healthy patients with TAA and a family history of aortic dissection (who may be more likely to have connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, or vascular Ehler-Danlos syndrome) may elect to undergo repair when the aneurysm reaches or nearly reaches the diameter of that of the family member’s aorta when dissection occurred.2 On the other hand, TAA of degenerative etiology (eg, related to smoking or hypertension) measuring less than 5.5 cm in an older patient with comorbidities poses a lower risk of a catastrophic event such as dissection or rupture than the risk of surgery.11

Thresholds for surgery. Once the diameter of the ascending aorta reaches 6 cm, the likelihood of an acute dissection is 31%.11 A similar threshold is reached for the descending aorta at a size of 7 cm.11 Therefore, to avoid high-risk emergency surgery on an acutely dissected aorta, surgery on an ascending aortic aneurysm of degenerative etiology is usually suggested when the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm or a documented growth rate greater than 0.5 cm/year.2,33

Additionally, in patients already undergoing surgery for valvular or coronary disease, prophylactic aortic replacement is recommended if the ascending aorta is larger than 4.5 cm. The threshold for intervention is lower in patients with connective tissue disease (> 5.0 cm for Marfan syndrome, 4.4–4.6 cm for Loeys-Dietz syndrome).2,33

Observational studies suggest that the risk of aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy is low overall, though significantly greater than in the general population.18,34,35 These findings led to changes in the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on valvular heart disease,36 suggesting a surgical threshold of 5.5 cm in the absence of significant valve disease or family history of dissection of an aorta of smaller diameter.

A 2015 study of dissection risk in patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy by our group found a dramatic increase in risk of aortic dissection for ascending aortic diameters greater than 5.3 cm, and a gradual increase in risk for aortic root diameters greater than 5.0 cm.37 In addition, a near-constant 3% to 4% risk of dissection was present for aortic diameters ranging from 4.7 cm to 5.0 cm, revealing that watchful waiting carries its own inherent risks.37 In our surgical experience with this population, the hospital mortality rate and risk of stroke from aortic surgery were 0.25% and 0.75%, respectively.37 Thus, the decision to operate for aortic aneurysm in the setting of a bicuspid aortic valve should take into account patient-specific factors and institutional outcomes.

A statement of clarification in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines was published in 2015, recommending surgery for patients with an aortic diameter of 5.0 cm or greater if the patient is at low risk and the surgery is performed by an experienced surgical team at a center with established surgical expertise in this condition.38 However, current recommendations are for surgery at 5.5 cm if the above conditions are not met.

Ratio of aortic cross-sectional area to height

Although size alone has long been used to guide surgical intervention, a recent review from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection revealed that 59% of patients suffered aortic dissection at diameters less than 5.5 cm, and that patients with certain connective tissue diseases such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome or familial thoracic aneurysm and dissection had a documented propensity for dissection at smaller diameters.39–41

Size indices such as the aortic cross-sectional area indexed to height have been implemented in guidelines for certain patient populations (eg, 10 cm2/m in Marfan syndrome) and provide better risk stratification than size cutoffs alone.2,42

The ratio of aortic cross-sectional area to the patient’s height has also been applied to patients with bicuspid aortic valve-associated aortopathy and to those with a dilated aorta and a tricuspid aortic valve.43,44 Notably, a ratio greater than 10 cm2/m has been associated with aortic dissection in these groups, and this cutoff provides better stratification for prediction of death than traditional size metrics.27,28

HOW SHOULD PATIENTS BE SCREENED? WHAT FOLLOW-UP IS NECESSARY?

Initial screening and follow-up

Follow-up of TAA depends on the initial aortic size or rate of growth, or both. For patients presenting for the first time with TAA, it is reasonable to obtain definitive aortic imaging with CT or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), then to repeat imaging at 6 months to document stability. If the aortic dimensions remain stable, then annual follow-up with CT or MRA is reasonable.2

Our flow chart of initial screening and follow-up is shown in Figure 5.

Screening of family members

In our center, we routinely recommend screening of all first-degree relatives of patients with TAA. Aortic imaging with echocardiography plus CT or MRI should be considered to detect asymptomatic disease.2 In patients with a strong family history (ie, multiple relatives affected with aortic aneurysm, dissection, or sudden cardiac death), genetic screening and testing for known mutations are recommended for the patient as well as for the family members.

If a mutation is identified in a family, then first-degree relatives should undergo genetic screening for the mutation and aortic imaging.2 Imaging in second-degree relatives may also be considered if one or more first-degree relatives are found to have aortic dilation.2

We recommend similar screening of first-degree family members of patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy. In patients with young children, we recommend obtaining an echocardiogram of the child to look for a bicuspid aortic valve or aortic dilation. If an abnormality is detected or suspected, dedicated imaging with MRA to assess aortic dimensions is warranted.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT WITH A BICUSPID AORTIC VALVE

Our patient with a bicuspid aortic valve had a 4.6-cm root, an ascending aortic aneurysm, and several affected family members.

We would obtain dedicated aortic imaging at this patient’s initial visit with either gated CT with contrast or MRA, and we would obtain a cardioaortic surgery consult. We would repeat these studies at a follow-up visit 6 months later to detect any aortic growth compared with initial studies, and follow up annually thereafter. Echocardiography can also be done at the initial visit to determine if valvular disease is present that may influence clinical decisions.

Surgery would likely be recommended once the root reached a maximum area-to-height ratio greater than 10 cm2/m, or if the valve became severely dysfunctional during follow-up.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT WITH MARFAN SYNDROME

The young woman with Marfan syndrome has a 4.6-cm aortic root aneurysm and 2+ aortic insufficiency. Her question pertains to the threshold at which an operation would be considered. This question is complicated and is influenced by several concurrent clinical features in her presentation.

Starting with size criteria, patients with Marfan syndrome should be considered for elective aortic root repair at a diameter greater than 5 cm. However, an aortic cross-sectional area-to-height ratio greater than 10 cm2/m may provide a more robust metric for clinical decision-making than aortic diameter alone. Additional factors such as degree of aortic insufficiency and deleterious left ventricular remodeling may urge one to consider aortic root repair at a diameter of 4.5 cm.

These factors, including rate of growth and the surgeon’s assessment about his or her ability to preserve the aortic valve during repair, should be considered collectively in this scenario.

Thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) needs to be detected, monitored, and managed in a timely manner to prevent a serious consequence such as acute dissection or rupture. But only about 5% of patients experience symptoms before an acute event occurs, and for the other 95% the first “symptom” is often death.1 Most cases are detected either incidentally with echocardiography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during workup for another condition. Patients may also be diagnosed during workup of a murmur or after a family member is found to have an aneurysm. Therefore, its true incidence is difficult to determine.2

With these facts in mind, how would you manage the following 2 cases?

Case 1: Bicuspid aortic valve, ascending aortic aneurysm

A 45-year-old man with stage 1 hypertension presents for evaluation of a bicuspid aortic valve and ascending aortic aneurysm. He has several first-degree relatives with similar conditions, and his brother recently underwent elective aortic repair. At the urging of his primary care physician, he underwent screening echocardiography, which demonstrated a “dilated root and ascending aorta” 4.6 cm in diameter. He presents today to discuss management options and how the aneurysm could affect his everyday life.

Case 2: Marfan syndrome in a young woman

A 24-year-old woman with Marfan syndrome diagnosed in adolescence presents for annual follow-up. She has many family members with the same condition, and several have undergone prophylactic aortic root repair. Her aortic root has been monitored annually for progression of dilation, and today it is 4.6 cm in diameter, a 3-mm increase from the last measurement. She has grade 2+ aortic insufficiency (on a scale of 1+ to 4+) based on echocardiography, but she has no symptoms. She is curious about what size her aortic root will need to reach for surgery to be considered.

LIKELY UNDERDETECTED

TAA is being detected more often than in the past thanks to better detection methods and heightened awareness among physicians and patients. While an incidence rate of 10.4 per 100,000 patient-years is often cited,3 this figure likely underestimates the true incidence of this clinically silent condition. The most robust data come from studies based on in-hospital diagnostic codes coupled with data from autopsies for out-of-hospital deaths.

Olsson et al,4 in a 2016 study in Sweden, found the incidence of TAA and aortic dissection to be 16.3 per 100,000 per year for men and 9.1 per 100,000 per year for women.

Clouse et al5 reported the incidence of thoracic aortic dissection as 3.5 per 100,000 patient-years, and the same figure for thoracic aortic rupture.

Aneurysmal disease accounts for 52,000 deaths per year in the United States, making it the 19th most common cause of death.6 These figures are likely lower than the true mortality rate for this condition, given that aortic dissection is often mistaken for acute myocardial infarction or other acute event if an autopsy is not done to confirm the cause of death.7

RISK FACTORS FOR THORACIC AORTIC ANEURYSM

Risk factors for TAA include genetic conditions that lead to aortic medial weakness or destruction such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome and Marfan syndrome.2 In addition, family history is important even in the absence of known genetic mutations. Other risk factors include conditions that increase aortic wall stress, such as hypertension, cocaine abuse, extreme weightlifting, trauma, and aortic coarctation.2

DIAMETER INCREASES WITH AGE, BODY SURFACE AREA

Normal dimensions for the aortic segments differ depending on age, sex, and body surface area.8,44,45 The size of the aortic root may also vary depending on how it is measured, due to the root’s trefoil shape. Measured sinus to sinus, the root is larger than when measured sinus to commissure on CT angiography or cardiac MRI. It is also larger when measured leading edge to leading edge than inner edge to inner edge on echocardiography.10

TAA is defined as an aortic diameter at least 50% greater than the upper limit of normal.8

Geometric changes in the curvature of the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending thoracic aorta can occur as the result of hypertension, atherosclerosis, or connective tissue disease.

HOW IS TAA DIAGNOSED?

Imaging tests

It is particularly important to obtain a gated CTA image in patients with aortic root aneurysm to avoid motion artifact and possible erroneous measurements. Gated CTA is done with electrocardiographic synchronization and allows for image processing to correct for cardiac motion.

HOW IS TAA CLASSIFIED?

TAA can be caused by a variety of inherited and sporadic conditions. These differences in pathogenesis lend themselves to classification of aneurysms into groups. Table 3 highlights the most common conditions associated with TAA.13

Bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy

From 1% to 2% of people have a bicuspid aortic valve, with a 3-to-1 male predominance.14,15 Aortic dilation occurs in 35% to 80% of people who have a bicuspid aortic valve, conferring a risk of dissection 8 times higher than in the general population.16–18

The pathogenic mechanisms that lead to this condition are widely debated, although a combination of genetic defects leading to intrinsic weakening of the aortic wall and hemodynamic effects likely contribute.19 Evidence of hemodynamic contributions to aortic dilation comes from findings that particular patterns of cusp fusion of the bicuspid aortic valve result in changes in transvalvular flow, placing more stress on specific regions of the ascending aorta.20,21 These hemodynamic alterations result in patterns of aortic dilation that depend on cusp fusion and the presence of valvular disease.

Multiple small studies found that replacing bicuspid aortic valves reduced the rate of aortic dilation, suggesting that hemodynamic factors may play a larger role than intrinsic wall properties in genetically susceptible individuals.22,23 However, larger studies are needed before any definitive conclusions can be made.

HOW IS ANEURYSM MANAGED ON AN OUTPATIENT BASIS?

Patients with a new diagnosis of TAA should be referred to a cardiologist with expertise in managing aortic disease or to a cardiac surgeon specializing in aortic surgery, depending on the initial size of the aneurysm.

Control blood pressure with beta-blockers

Medical management for patients with TAA has historically been limited to strict blood pressure control aimed at reducing aortic wall stress, mainly with beta-blockers.

Are angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) beneficial? Studies in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome revealed that the ARB losartan attenuated aortic root growth.24 The results of early, small studies in humans were promising,25–27 but larger randomized trials have shown no advantage of losartan over beta-blockers in slowing aortic root growth.28 These negative results led many to question the effectiveness of losartan, although some point out that no studies have shown even beta-blockers to be beneficial in reducing the clinical end points of death or dissection.29 On the other hand, patients with certain FBN1 mutations respond more readily than others to losartan.30 Additional clinical trials of ARBs in Marfan syndrome are ongoing.

Current guidelines recommend stringent blood pressure control and smoking cessation for patients with a small aneurysm not requiring surgery and for those who are considered unsuitable for surgical or percutaneous intervention (level of evidence C, the lowest).2 For patients with TAA, it is considered reasonable to give beta-blockers. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or ARBs may be used in combination with beta-blockers, titrated to the lowest tolerable blood pressure without adverse effects (level of evidence B).2

The recommended target blood pressure is less than 140/90 mm Hg, or 130/80 mm Hg in those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease (level of evidence B).2 However, we recommend more stringent blood pressure control: ie, less than 130/80 mm Hg for all patients with aortic aneurysm and a heart rate goal of 70 beats per minute or less, as tolerated.

Activity restriction

Activity restrictions for patients with TAA are largely based on theory, and certain activities may require more modification than others. For example, heavy lifting should be discouraged, as it may increase blood pressure significantly for short periods of time.2,31 The increased wall stress, in theory, could initiate dissection or rupture. However, moderate-intensity aerobic activity is rarely associated with significant elevations in blood pressure and should be encouraged. Stressful emotional states have been anecdotally associated with aortic dissection; thus, measures to reduce stress may offer some benefit.31

Our recommendations. While there are no published guidelines regarding activity restrictions in patients with TAA, we use a graded approach based on aortic diameter:

- 4.0 to 4.4 cm—lift no more than 75 pounds

- 4.5 to 5 cm—lift no more than 50 pounds

- 5 cm—lift no more than 25 pounds.

We also recommend not lifting anything heavier than half of one’s body weight and to avoid breath-holding or performing the Valsalva maneuver while lifting. Although these recommendations are somewhat arbitrary, based on theory and a large clinical experience at our aortic center, they seem reasonable and practical.

Activity restrictions should be stringent and individualized in patients with Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome due to increased risk of dissection or rupture even if the aorta is normal in size.

We sometimes recommend exercise stress testing to assess the heart rate and blood pressure response to exercise, and we are developing research protocols to help tailor activity recommendations.

WHEN SHOULD A PATIENT BE REFERRED?

To a cardiologist at the time of diagnosis

As soon as TAA is diagnosed, the patient should be referred to a cardiologist who has special interest in aortic disease. This will allow for appropriate and timely decisions about medical management, imaging, follow-up, and referral to surgery. Additional recommendations for screening of family members and referral to clinical geneticists can be discussed at this juncture. Activity restrictions should be reviewed at the initial evaluation.

To a surgeon relatively early

Size thresholds for surgical intervention are discussed below, but one should not wait until these thresholds are reached to send the patient for surgical consultation. It is beneficial to the state of mind of a potential surgical candidate to have early discussions pertaining to the types of operations available, their outcomes, and associated risks and benefits. If a patient’s aortic size remains stable over time, he or she may be followed by the cardiologist until significant size or growth has been documented, at which time the patient and surgeon can reconvene to discuss options for definitive treatment.

To a clinical geneticist

If 1 or more first-degree relatives of a patient with TAA or dissection are found to have aneurysmal disease, referral to a clinical geneticist is very important for genetic testing of multiple genes that have been implicated in thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection.

WHEN SHOULD TAA BE REPAIRED?

Surgery to prevent rupture or dissection remains the definitive treatment of TAA when size thresholds are reached, and symptomatic aneurysm should be operated on regardless of the size. However, rarely are thoracic aneurysms symptomatic unless they rupture or dissect. The size criteria are based on underlying genetic etiology if known and on the behavior and natural course of TAA.

Size and other factors

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s clinical scenario, family history, and estimated risk of rupture or dissection, balanced against the individual center’s outcomes of elective aortic replacement.32 For example, young and otherwise healthy patients with TAA and a family history of aortic dissection (who may be more likely to have connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, or vascular Ehler-Danlos syndrome) may elect to undergo repair when the aneurysm reaches or nearly reaches the diameter of that of the family member’s aorta when dissection occurred.2 On the other hand, TAA of degenerative etiology (eg, related to smoking or hypertension) measuring less than 5.5 cm in an older patient with comorbidities poses a lower risk of a catastrophic event such as dissection or rupture than the risk of surgery.11

Thresholds for surgery. Once the diameter of the ascending aorta reaches 6 cm, the likelihood of an acute dissection is 31%.11 A similar threshold is reached for the descending aorta at a size of 7 cm.11 Therefore, to avoid high-risk emergency surgery on an acutely dissected aorta, surgery on an ascending aortic aneurysm of degenerative etiology is usually suggested when the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm or a documented growth rate greater than 0.5 cm/year.2,33

Additionally, in patients already undergoing surgery for valvular or coronary disease, prophylactic aortic replacement is recommended if the ascending aorta is larger than 4.5 cm. The threshold for intervention is lower in patients with connective tissue disease (> 5.0 cm for Marfan syndrome, 4.4–4.6 cm for Loeys-Dietz syndrome).2,33

Observational studies suggest that the risk of aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy is low overall, though significantly greater than in the general population.18,34,35 These findings led to changes in the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on valvular heart disease,36 suggesting a surgical threshold of 5.5 cm in the absence of significant valve disease or family history of dissection of an aorta of smaller diameter.

A 2015 study of dissection risk in patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy by our group found a dramatic increase in risk of aortic dissection for ascending aortic diameters greater than 5.3 cm, and a gradual increase in risk for aortic root diameters greater than 5.0 cm.37 In addition, a near-constant 3% to 4% risk of dissection was present for aortic diameters ranging from 4.7 cm to 5.0 cm, revealing that watchful waiting carries its own inherent risks.37 In our surgical experience with this population, the hospital mortality rate and risk of stroke from aortic surgery were 0.25% and 0.75%, respectively.37 Thus, the decision to operate for aortic aneurysm in the setting of a bicuspid aortic valve should take into account patient-specific factors and institutional outcomes.

A statement of clarification in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines was published in 2015, recommending surgery for patients with an aortic diameter of 5.0 cm or greater if the patient is at low risk and the surgery is performed by an experienced surgical team at a center with established surgical expertise in this condition.38 However, current recommendations are for surgery at 5.5 cm if the above conditions are not met.

Ratio of aortic cross-sectional area to height

Although size alone has long been used to guide surgical intervention, a recent review from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection revealed that 59% of patients suffered aortic dissection at diameters less than 5.5 cm, and that patients with certain connective tissue diseases such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome or familial thoracic aneurysm and dissection had a documented propensity for dissection at smaller diameters.39–41

Size indices such as the aortic cross-sectional area indexed to height have been implemented in guidelines for certain patient populations (eg, 10 cm2/m in Marfan syndrome) and provide better risk stratification than size cutoffs alone.2,42

The ratio of aortic cross-sectional area to the patient’s height has also been applied to patients with bicuspid aortic valve-associated aortopathy and to those with a dilated aorta and a tricuspid aortic valve.43,44 Notably, a ratio greater than 10 cm2/m has been associated with aortic dissection in these groups, and this cutoff provides better stratification for prediction of death than traditional size metrics.27,28

HOW SHOULD PATIENTS BE SCREENED? WHAT FOLLOW-UP IS NECESSARY?

Initial screening and follow-up

Follow-up of TAA depends on the initial aortic size or rate of growth, or both. For patients presenting for the first time with TAA, it is reasonable to obtain definitive aortic imaging with CT or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), then to repeat imaging at 6 months to document stability. If the aortic dimensions remain stable, then annual follow-up with CT or MRA is reasonable.2

Our flow chart of initial screening and follow-up is shown in Figure 5.

Screening of family members

In our center, we routinely recommend screening of all first-degree relatives of patients with TAA. Aortic imaging with echocardiography plus CT or MRI should be considered to detect asymptomatic disease.2 In patients with a strong family history (ie, multiple relatives affected with aortic aneurysm, dissection, or sudden cardiac death), genetic screening and testing for known mutations are recommended for the patient as well as for the family members.

If a mutation is identified in a family, then first-degree relatives should undergo genetic screening for the mutation and aortic imaging.2 Imaging in second-degree relatives may also be considered if one or more first-degree relatives are found to have aortic dilation.2

We recommend similar screening of first-degree family members of patients with bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy. In patients with young children, we recommend obtaining an echocardiogram of the child to look for a bicuspid aortic valve or aortic dilation. If an abnormality is detected or suspected, dedicated imaging with MRA to assess aortic dimensions is warranted.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT WITH A BICUSPID AORTIC VALVE

Our patient with a bicuspid aortic valve had a 4.6-cm root, an ascending aortic aneurysm, and several affected family members.

We would obtain dedicated aortic imaging at this patient’s initial visit with either gated CT with contrast or MRA, and we would obtain a cardioaortic surgery consult. We would repeat these studies at a follow-up visit 6 months later to detect any aortic growth compared with initial studies, and follow up annually thereafter. Echocardiography can also be done at the initial visit to determine if valvular disease is present that may influence clinical decisions.

Surgery would likely be recommended once the root reached a maximum area-to-height ratio greater than 10 cm2/m, or if the valve became severely dysfunctional during follow-up.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT WITH MARFAN SYNDROME

The young woman with Marfan syndrome has a 4.6-cm aortic root aneurysm and 2+ aortic insufficiency. Her question pertains to the threshold at which an operation would be considered. This question is complicated and is influenced by several concurrent clinical features in her presentation.

Starting with size criteria, patients with Marfan syndrome should be considered for elective aortic root repair at a diameter greater than 5 cm. However, an aortic cross-sectional area-to-height ratio greater than 10 cm2/m may provide a more robust metric for clinical decision-making than aortic diameter alone. Additional factors such as degree of aortic insufficiency and deleterious left ventricular remodeling may urge one to consider aortic root repair at a diameter of 4.5 cm.