User login

Should breast cancer screening guidelines be tailored to a patient’s race and ethnicity?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Breast cancer screening is an important aspect of women’s preventative health care, with proven mortality benefits.1,2 Different recommendations have been made for the age at initiation and the frequency of breast cancer screening in an effort to maximize benefit while minimizing unnecessary health care costs and harms of screening.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend initiating mammography screening at age 40, with annual screening (although ACOG offers deferral of screening to age 50 and biennial screening through shared decision making).3,4 The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends offering annual mammography at ages 40 to 44 and recommends routinely starting annual mammography from 45 to 54, followed by either annual or biennial screening for women 55 and older.1 Finally, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends biennial mammography screening starting at age 50.5 No organization alters screening recommendations based on a woman’s race/ethnicity.

Details of the study

Stapleton and colleagues recently performed a retrospective population-based cohort study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database to evaluate the age and stage at breast cancer diagnosis across different racial groups in the United States.6 The study (timeframe, January 1, 1973 to December 31, 2010) included 747,763 women, with a racial/ethnic distribution of 77.0% white, 9.3% black, 7.0% Hispanic, and 6.2% Asian.

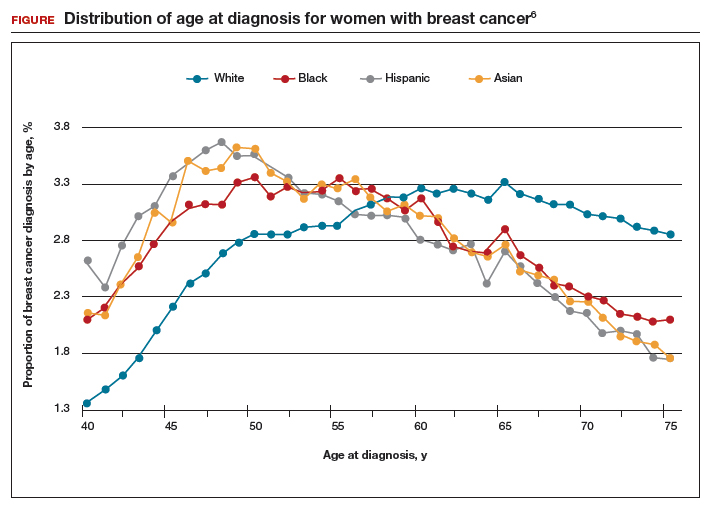

The investigators found 2 distinct age distributions of breast cancer based on race. Among nonwhite women, the highest peak of breast cancer diagnoses occurred between 45 and 50 years (FIGURE). By contrast, breast cancer diagnoses peaked at 60 to 65 years in white women.

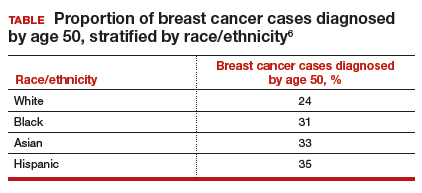

Similarly, a higher proportion of nonwhite women were diagnosed with their breast cancer prior to age 50 compared with white women. While one-quarter of white women with breast cancer develop disease prior to age 50, approximately one-third of black, Asian, and Hispanic women with breast cancer will be diagnosed before age 50 (TABLE).

These data suggest that the peak proportion of breast cancer diagnoses in nonwhite women occurs prior to the age of initiation of screening recommended by the USPSTF. Based on these results, Stapleton and colleagues recommend reconsideration of the current USPSTF guidelines to incorporate race/ethnicity–based differences. To diagnose the same proportion of breast cancer cases among nonwhite women as is currently possible among white women at age 50, initiation of breast cancer screening would need to be adjusted to age 47 for black women, age 46 for Hispanic women, and age 47 for Asian women.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is a unique study that uses the SEER database to capture a large cross section of the American population. The SEER database is a valuable tool because it gathers data from numerous major US metropolitan areas, creating a diverse representative population that minimizes confounding from geographical trends. Nevertheless, any study utilizing a large database is limited by the accuracy and completeness of the data collected at the level of the individual cancer registry. Furthermore, information regarding medical comorbidities and access and adherence to breast cancer screening is lacking in the SEER database; this provides an opportunity for confounding.

Approximately one-third of breast cancer cases in nonwhite women, and one-quarter of cases in white women, occur prior to the age of initiation of screening (50 years) recommended by the USPSTF.

While some screening organizations do recommend that breast cancer screening be initiated prior to age 50, no organizations alter the recommendations for screening based on a woman's race/ethnicity.

Health care providers should be aware that initiation of breast cancer screening at age 50 in nonwhite women misses a disproportionate number of breast cancer cases compared with white women.

Providers should counsel nonwhite women about these differences in age of diagnosis and include that in their consideration of initiating breast cancer screening prior to the age of 50, more in accordance with recommendations of ACOG, NCCN, and ACS.

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614.

- Arleo EK, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Sickles EA. Comparison of recommendations for screening mammography using CISNET models. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3673–3680.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 179: Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e1–e16.

- Bevers TB, Anderson BO, Bonaccio E, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(10):1060–1096.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–726.

- Stapleton SM, Oseni TO, Bababekov YJ, Hung Y-C, Chang DC. Race/ethnicity and age distribution of breast cancer diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Surg. Published online March 7, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0035.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Breast cancer screening is an important aspect of women’s preventative health care, with proven mortality benefits.1,2 Different recommendations have been made for the age at initiation and the frequency of breast cancer screening in an effort to maximize benefit while minimizing unnecessary health care costs and harms of screening.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend initiating mammography screening at age 40, with annual screening (although ACOG offers deferral of screening to age 50 and biennial screening through shared decision making).3,4 The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends offering annual mammography at ages 40 to 44 and recommends routinely starting annual mammography from 45 to 54, followed by either annual or biennial screening for women 55 and older.1 Finally, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends biennial mammography screening starting at age 50.5 No organization alters screening recommendations based on a woman’s race/ethnicity.

Details of the study

Stapleton and colleagues recently performed a retrospective population-based cohort study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database to evaluate the age and stage at breast cancer diagnosis across different racial groups in the United States.6 The study (timeframe, January 1, 1973 to December 31, 2010) included 747,763 women, with a racial/ethnic distribution of 77.0% white, 9.3% black, 7.0% Hispanic, and 6.2% Asian.

The investigators found 2 distinct age distributions of breast cancer based on race. Among nonwhite women, the highest peak of breast cancer diagnoses occurred between 45 and 50 years (FIGURE). By contrast, breast cancer diagnoses peaked at 60 to 65 years in white women.

Similarly, a higher proportion of nonwhite women were diagnosed with their breast cancer prior to age 50 compared with white women. While one-quarter of white women with breast cancer develop disease prior to age 50, approximately one-third of black, Asian, and Hispanic women with breast cancer will be diagnosed before age 50 (TABLE).

These data suggest that the peak proportion of breast cancer diagnoses in nonwhite women occurs prior to the age of initiation of screening recommended by the USPSTF. Based on these results, Stapleton and colleagues recommend reconsideration of the current USPSTF guidelines to incorporate race/ethnicity–based differences. To diagnose the same proportion of breast cancer cases among nonwhite women as is currently possible among white women at age 50, initiation of breast cancer screening would need to be adjusted to age 47 for black women, age 46 for Hispanic women, and age 47 for Asian women.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is a unique study that uses the SEER database to capture a large cross section of the American population. The SEER database is a valuable tool because it gathers data from numerous major US metropolitan areas, creating a diverse representative population that minimizes confounding from geographical trends. Nevertheless, any study utilizing a large database is limited by the accuracy and completeness of the data collected at the level of the individual cancer registry. Furthermore, information regarding medical comorbidities and access and adherence to breast cancer screening is lacking in the SEER database; this provides an opportunity for confounding.

Approximately one-third of breast cancer cases in nonwhite women, and one-quarter of cases in white women, occur prior to the age of initiation of screening (50 years) recommended by the USPSTF.

While some screening organizations do recommend that breast cancer screening be initiated prior to age 50, no organizations alter the recommendations for screening based on a woman's race/ethnicity.

Health care providers should be aware that initiation of breast cancer screening at age 50 in nonwhite women misses a disproportionate number of breast cancer cases compared with white women.

Providers should counsel nonwhite women about these differences in age of diagnosis and include that in their consideration of initiating breast cancer screening prior to the age of 50, more in accordance with recommendations of ACOG, NCCN, and ACS.

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Breast cancer screening is an important aspect of women’s preventative health care, with proven mortality benefits.1,2 Different recommendations have been made for the age at initiation and the frequency of breast cancer screening in an effort to maximize benefit while minimizing unnecessary health care costs and harms of screening.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend initiating mammography screening at age 40, with annual screening (although ACOG offers deferral of screening to age 50 and biennial screening through shared decision making).3,4 The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends offering annual mammography at ages 40 to 44 and recommends routinely starting annual mammography from 45 to 54, followed by either annual or biennial screening for women 55 and older.1 Finally, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends biennial mammography screening starting at age 50.5 No organization alters screening recommendations based on a woman’s race/ethnicity.

Details of the study

Stapleton and colleagues recently performed a retrospective population-based cohort study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database to evaluate the age and stage at breast cancer diagnosis across different racial groups in the United States.6 The study (timeframe, January 1, 1973 to December 31, 2010) included 747,763 women, with a racial/ethnic distribution of 77.0% white, 9.3% black, 7.0% Hispanic, and 6.2% Asian.

The investigators found 2 distinct age distributions of breast cancer based on race. Among nonwhite women, the highest peak of breast cancer diagnoses occurred between 45 and 50 years (FIGURE). By contrast, breast cancer diagnoses peaked at 60 to 65 years in white women.

Similarly, a higher proportion of nonwhite women were diagnosed with their breast cancer prior to age 50 compared with white women. While one-quarter of white women with breast cancer develop disease prior to age 50, approximately one-third of black, Asian, and Hispanic women with breast cancer will be diagnosed before age 50 (TABLE).

These data suggest that the peak proportion of breast cancer diagnoses in nonwhite women occurs prior to the age of initiation of screening recommended by the USPSTF. Based on these results, Stapleton and colleagues recommend reconsideration of the current USPSTF guidelines to incorporate race/ethnicity–based differences. To diagnose the same proportion of breast cancer cases among nonwhite women as is currently possible among white women at age 50, initiation of breast cancer screening would need to be adjusted to age 47 for black women, age 46 for Hispanic women, and age 47 for Asian women.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is a unique study that uses the SEER database to capture a large cross section of the American population. The SEER database is a valuable tool because it gathers data from numerous major US metropolitan areas, creating a diverse representative population that minimizes confounding from geographical trends. Nevertheless, any study utilizing a large database is limited by the accuracy and completeness of the data collected at the level of the individual cancer registry. Furthermore, information regarding medical comorbidities and access and adherence to breast cancer screening is lacking in the SEER database; this provides an opportunity for confounding.

Approximately one-third of breast cancer cases in nonwhite women, and one-quarter of cases in white women, occur prior to the age of initiation of screening (50 years) recommended by the USPSTF.

While some screening organizations do recommend that breast cancer screening be initiated prior to age 50, no organizations alter the recommendations for screening based on a woman's race/ethnicity.

Health care providers should be aware that initiation of breast cancer screening at age 50 in nonwhite women misses a disproportionate number of breast cancer cases compared with white women.

Providers should counsel nonwhite women about these differences in age of diagnosis and include that in their consideration of initiating breast cancer screening prior to the age of 50, more in accordance with recommendations of ACOG, NCCN, and ACS.

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614.

- Arleo EK, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Sickles EA. Comparison of recommendations for screening mammography using CISNET models. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3673–3680.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 179: Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e1–e16.

- Bevers TB, Anderson BO, Bonaccio E, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(10):1060–1096.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–726.

- Stapleton SM, Oseni TO, Bababekov YJ, Hung Y-C, Chang DC. Race/ethnicity and age distribution of breast cancer diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Surg. Published online March 7, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0035.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614.

- Arleo EK, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Sickles EA. Comparison of recommendations for screening mammography using CISNET models. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3673–3680.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 179: Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e1–e16.

- Bevers TB, Anderson BO, Bonaccio E, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(10):1060–1096.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–726.

- Stapleton SM, Oseni TO, Bababekov YJ, Hung Y-C, Chang DC. Race/ethnicity and age distribution of breast cancer diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Surg. Published online March 7, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0035.

FDA approves estradiol vaginal inserts for dyspareunia*

, in a 4-mcg and 10-mcg dose. The 4-mcg dose is a lower dose than any currently available.

The hormone treatment is intended for dyspareunia resulting from menopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. The patient places a soft gel capsule in the lower part of the vagina, daily for 2 weeks, then at a reduced rate of twice per week. The capsule dissolves and reintroduces estrogen to the tissue.

The manufacturer of the product, TherapeuticsMD, has committed to conduct a postapproval observational study, as a condition of approval.

Estradiol comes with a boxed warning of risks of endometrial cancer, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, breast cancer, and “probable dementia.” The most common adverse reaction to the estradiol vaginal inserts was headache.

Editor's Note: This article has been corrected to state that the 4-mcg dose showed significant improvement in severity of dyspareunia.

dwatson@mdedge.com

, in a 4-mcg and 10-mcg dose. The 4-mcg dose is a lower dose than any currently available.

The hormone treatment is intended for dyspareunia resulting from menopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. The patient places a soft gel capsule in the lower part of the vagina, daily for 2 weeks, then at a reduced rate of twice per week. The capsule dissolves and reintroduces estrogen to the tissue.

The manufacturer of the product, TherapeuticsMD, has committed to conduct a postapproval observational study, as a condition of approval.

Estradiol comes with a boxed warning of risks of endometrial cancer, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, breast cancer, and “probable dementia.” The most common adverse reaction to the estradiol vaginal inserts was headache.

Editor's Note: This article has been corrected to state that the 4-mcg dose showed significant improvement in severity of dyspareunia.

dwatson@mdedge.com

, in a 4-mcg and 10-mcg dose. The 4-mcg dose is a lower dose than any currently available.

The hormone treatment is intended for dyspareunia resulting from menopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. The patient places a soft gel capsule in the lower part of the vagina, daily for 2 weeks, then at a reduced rate of twice per week. The capsule dissolves and reintroduces estrogen to the tissue.

The manufacturer of the product, TherapeuticsMD, has committed to conduct a postapproval observational study, as a condition of approval.

Estradiol comes with a boxed warning of risks of endometrial cancer, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, breast cancer, and “probable dementia.” The most common adverse reaction to the estradiol vaginal inserts was headache.

Editor's Note: This article has been corrected to state that the 4-mcg dose showed significant improvement in severity of dyspareunia.

dwatson@mdedge.com

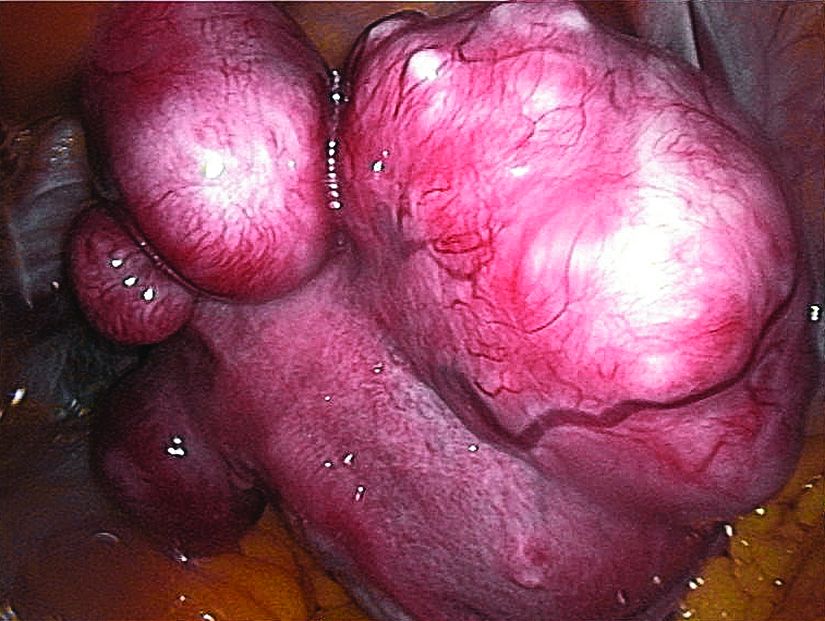

Uterine fibroids registry looks to provide comparative treatment data

Early findings from a uterine fibroids registry suggest more than half of enrolled women chose an alternative to hysterectomy, underscoring the need to study the efficacy of these uterine-sparing treatment options, said Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates.

There is very little evidence on the comparative efficacy of uterine fibroid treatment options so the COMPARE-UF (Comparing Options for Management: Patient-Centered Results for Uterine Fibroids) registry was initiated for women who choose procedural therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Data at the nine clinical centers – representing rural and urban populations – are being collected regarding hysterectomy, myomectomy (abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal, and laparoscopic/robotic), endometrial ablation, radiofrequency fibroid ablation, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound, and therapeutic use of progestin-releasing intrauterine devices.

A total of 16% of the women were under age 35, and 40% were aged 40 years or younger. “The fact that a sizable proportion of women are under age 40 suggests that with long-term follow-up, data on reproductive outcomes can be obtained as these women seek pregnancy,” Dr. Stewart and her associates noted.

Although African American women make up only 13% of the U.S. population, they constitute 42% of enrollment in COMPARE-UF, the investigators reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. African American women chose similar or greater numbers of each type of myomectomy and uterine embolization as white women chose.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The registry is supported by AHRQ and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

Early findings from a uterine fibroids registry suggest more than half of enrolled women chose an alternative to hysterectomy, underscoring the need to study the efficacy of these uterine-sparing treatment options, said Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates.

There is very little evidence on the comparative efficacy of uterine fibroid treatment options so the COMPARE-UF (Comparing Options for Management: Patient-Centered Results for Uterine Fibroids) registry was initiated for women who choose procedural therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Data at the nine clinical centers – representing rural and urban populations – are being collected regarding hysterectomy, myomectomy (abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal, and laparoscopic/robotic), endometrial ablation, radiofrequency fibroid ablation, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound, and therapeutic use of progestin-releasing intrauterine devices.

A total of 16% of the women were under age 35, and 40% were aged 40 years or younger. “The fact that a sizable proportion of women are under age 40 suggests that with long-term follow-up, data on reproductive outcomes can be obtained as these women seek pregnancy,” Dr. Stewart and her associates noted.

Although African American women make up only 13% of the U.S. population, they constitute 42% of enrollment in COMPARE-UF, the investigators reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. African American women chose similar or greater numbers of each type of myomectomy and uterine embolization as white women chose.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The registry is supported by AHRQ and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

Early findings from a uterine fibroids registry suggest more than half of enrolled women chose an alternative to hysterectomy, underscoring the need to study the efficacy of these uterine-sparing treatment options, said Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates.

There is very little evidence on the comparative efficacy of uterine fibroid treatment options so the COMPARE-UF (Comparing Options for Management: Patient-Centered Results for Uterine Fibroids) registry was initiated for women who choose procedural therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Data at the nine clinical centers – representing rural and urban populations – are being collected regarding hysterectomy, myomectomy (abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal, and laparoscopic/robotic), endometrial ablation, radiofrequency fibroid ablation, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound, and therapeutic use of progestin-releasing intrauterine devices.

A total of 16% of the women were under age 35, and 40% were aged 40 years or younger. “The fact that a sizable proportion of women are under age 40 suggests that with long-term follow-up, data on reproductive outcomes can be obtained as these women seek pregnancy,” Dr. Stewart and her associates noted.

Although African American women make up only 13% of the U.S. population, they constitute 42% of enrollment in COMPARE-UF, the investigators reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. African American women chose similar or greater numbers of each type of myomectomy and uterine embolization as white women chose.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The registry is supported by AHRQ and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the initial 2,031 women enrolled in the registry, hysterectomy was chosen by 38%, and myomectomies were chosen by 46%.

Study details: Initial results from the COMPARE-UF registry.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

FP can perform the circumcision

FP can perform the circumcision

I enjoyed Dr. Lerner's brief review but was puzzled by the question of who should perform the circumcision. The most obvious and one of the most frequent answers was ignored. It should be done by the family physician who delivered the baby, is caring for him in the nursery, and will be caring for him another couple of decades.

John R. Carroll, MD

Corpus Christi, Texas

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

FP can perform the circumcision

I enjoyed Dr. Lerner's brief review but was puzzled by the question of who should perform the circumcision. The most obvious and one of the most frequent answers was ignored. It should be done by the family physician who delivered the baby, is caring for him in the nursery, and will be caring for him another couple of decades.

John R. Carroll, MD

Corpus Christi, Texas

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

FP can perform the circumcision

I enjoyed Dr. Lerner's brief review but was puzzled by the question of who should perform the circumcision. The most obvious and one of the most frequent answers was ignored. It should be done by the family physician who delivered the baby, is caring for him in the nursery, and will be caring for him another couple of decades.

John R. Carroll, MD

Corpus Christi, Texas

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Tip for when using phenazophyridine

Tip for when using phenazophyridine

I enjoyed the review by Dr. Iglesia on agents that are used to demonstrate ureteral patency. I like phenazopyridine because it is cheap and readily available. It works great if you remember one thing: drain the bladder first so the orange color stands out in the colorless saline irrigant. Otherwise, the orange-dyed urine obscures the orange ureteral jets.

John H. Sand, MD

Ellensburg, Washington

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Tip for when using phenazophyridine

I enjoyed the review by Dr. Iglesia on agents that are used to demonstrate ureteral patency. I like phenazopyridine because it is cheap and readily available. It works great if you remember one thing: drain the bladder first so the orange color stands out in the colorless saline irrigant. Otherwise, the orange-dyed urine obscures the orange ureteral jets.

John H. Sand, MD

Ellensburg, Washington

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Tip for when using phenazophyridine

I enjoyed the review by Dr. Iglesia on agents that are used to demonstrate ureteral patency. I like phenazopyridine because it is cheap and readily available. It works great if you remember one thing: drain the bladder first so the orange color stands out in the colorless saline irrigant. Otherwise, the orange-dyed urine obscures the orange ureteral jets.

John H. Sand, MD

Ellensburg, Washington

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Rash goes undetected

Rash goes undetected

As a urogynecologist, in the past 5 years I have had 2 urgent emergency department referrals from 2 towns. The patients had excruciating flank pain and had a negative computed tomography scan and normal pelvic and renal examinations, but no physical exam. They were subsequently found to have shingles!

Bunan Alnaif, MD

Chesapeake, Virginia

Physical exam revealed suspicious mass

Two years ago a regular gynecologic patient of mine came in 2 months early for her Pap test because she was concerned about a pressure in her genital area. I had delivered her 3 children. She was now in her mid-40s. She had visited her usual physician about the problem; she was not physically examined but was advised to see a gastrointestinal specialist, since the pressure caused constipation with discomfort. She then consulted a gastroenterologist, who performed a colonoscopy that was reported as normal. The patient related that she had no pelvic or rectal examination at that time, although it is possible that one could have been done while she was under anesthesia.

She arrived at my office 3 weeks later, and while doing the pelvic and rectal exam, I noted she had a 3- to 4-cm perirectal mass, which I thought was a Bartholin’s tumor. I referred her to a gynecologic oncologist who happened to write a paper on this subject. My diagnosis was wrong—she had a rectal carcinoma, which fortunately was Stage 1.

The patient subsequently has done well. The delay in diagnosis could have been averted if a simple rectal examination had been performed by the first doctor.

James Moran, MD

Santa Monica, California

Case of an almost missed diagnosis

I have many examples of how not performing a physical examination can cause problems, but here is a recent one. This involved a 70-year-old woman who had been seeing only her primary care physician for the past 30 years, with no pelvic examinations done. She had symptoms of vaginal discharge and itch for which she was given multiple courses of antifungals and topical steroids. Finally, she was referred to me. Examination revealed findings of extensive raised, erythematous, hyperkeratotic, macerated lesions throughout the vulva. A punch biopsy revealed severe vulvar dysplasia with areas suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma. I referred the patient to a gynecologic oncologist, who performed a simple vulvectomy. There were extensive foci of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3.

Susan Richman, MD

New Haven, Connecticut

Lack of physical exam leads to tortuous dx course

Here is a story of a patient who must have gone without having a pelvic examination or any evaluation for years. This 83-year-old woman had a previous transvaginal hysterectomy at age 49 for fibroids and bleeding. She is quite healthy and active for her age. She had problems with recurrent urinary tract infection for several years before being referred to a gynecologist. She had emergency room visits and multiple urgent care visits. She saw her primary care physician 3 times in 4 weeks for bladder pain and a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying. She reported that when she got up in the morning, it felt like her urine slowly leaked out for several hours. She was referred to a urologist, who saw her twice and did pelvic ultrasonography and postvoid residual urine testing—without a pelvic exam.

After 2 months of regular visits, an examination by her primary care physician revealed a complete fusion of the labia. Six months after her initial urology visit, the patient had an examination with a plan for cystoscopy, and the urologist ended up doing a “dilation of labial fusion” in the office. The patient’s urinary symptoms were improved slightly, and she had visits to the emergency room or urgent care once monthly for dysuria after dilation of the labia.

At that point she was referred to me. We tried topical estrogen for several months with minimal improvement in symptoms, and I performed a surgical separation of labial fusion in the operating room under monitored anesthesia care. After surgery the patient said that she felt like “I got my life back,” and she never knew how happy she could be to pee in the morning.

Theresa Gipps, MD

Walnut Creek, California

Agrees with importance of clinical exam

I fully agree that clinical examination skill is a dying art. But the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has issued guidelines stating that pelvic examination is not required, especially in asymptomatic women. Another area of concern is hair removal procedures like waxing and laser treatments in the pubic area, and whether these do harm in any way or increase the likelihood of skin problems.

Manju Hotchandani, MD

New Delhi, India

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Alnaif, Moran, Richman, Gipps, and Hotchandani for sharing their comments and important clinical vignettes concerning the primacy of the physical examination with our readers. In clinical practice there are many competing demands on the time of clinicians, but we should strive to preserve time for a good physical examination. If not us, who is going to perform a competent physical examination?

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Rash goes undetected

As a urogynecologist, in the past 5 years I have had 2 urgent emergency department referrals from 2 towns. The patients had excruciating flank pain and had a negative computed tomography scan and normal pelvic and renal examinations, but no physical exam. They were subsequently found to have shingles!

Bunan Alnaif, MD

Chesapeake, Virginia

Physical exam revealed suspicious mass

Two years ago a regular gynecologic patient of mine came in 2 months early for her Pap test because she was concerned about a pressure in her genital area. I had delivered her 3 children. She was now in her mid-40s. She had visited her usual physician about the problem; she was not physically examined but was advised to see a gastrointestinal specialist, since the pressure caused constipation with discomfort. She then consulted a gastroenterologist, who performed a colonoscopy that was reported as normal. The patient related that she had no pelvic or rectal examination at that time, although it is possible that one could have been done while she was under anesthesia.

She arrived at my office 3 weeks later, and while doing the pelvic and rectal exam, I noted she had a 3- to 4-cm perirectal mass, which I thought was a Bartholin’s tumor. I referred her to a gynecologic oncologist who happened to write a paper on this subject. My diagnosis was wrong—she had a rectal carcinoma, which fortunately was Stage 1.

The patient subsequently has done well. The delay in diagnosis could have been averted if a simple rectal examination had been performed by the first doctor.

James Moran, MD

Santa Monica, California

Case of an almost missed diagnosis

I have many examples of how not performing a physical examination can cause problems, but here is a recent one. This involved a 70-year-old woman who had been seeing only her primary care physician for the past 30 years, with no pelvic examinations done. She had symptoms of vaginal discharge and itch for which she was given multiple courses of antifungals and topical steroids. Finally, she was referred to me. Examination revealed findings of extensive raised, erythematous, hyperkeratotic, macerated lesions throughout the vulva. A punch biopsy revealed severe vulvar dysplasia with areas suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma. I referred the patient to a gynecologic oncologist, who performed a simple vulvectomy. There were extensive foci of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3.

Susan Richman, MD

New Haven, Connecticut

Lack of physical exam leads to tortuous dx course

Here is a story of a patient who must have gone without having a pelvic examination or any evaluation for years. This 83-year-old woman had a previous transvaginal hysterectomy at age 49 for fibroids and bleeding. She is quite healthy and active for her age. She had problems with recurrent urinary tract infection for several years before being referred to a gynecologist. She had emergency room visits and multiple urgent care visits. She saw her primary care physician 3 times in 4 weeks for bladder pain and a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying. She reported that when she got up in the morning, it felt like her urine slowly leaked out for several hours. She was referred to a urologist, who saw her twice and did pelvic ultrasonography and postvoid residual urine testing—without a pelvic exam.

After 2 months of regular visits, an examination by her primary care physician revealed a complete fusion of the labia. Six months after her initial urology visit, the patient had an examination with a plan for cystoscopy, and the urologist ended up doing a “dilation of labial fusion” in the office. The patient’s urinary symptoms were improved slightly, and she had visits to the emergency room or urgent care once monthly for dysuria after dilation of the labia.

At that point she was referred to me. We tried topical estrogen for several months with minimal improvement in symptoms, and I performed a surgical separation of labial fusion in the operating room under monitored anesthesia care. After surgery the patient said that she felt like “I got my life back,” and she never knew how happy she could be to pee in the morning.

Theresa Gipps, MD

Walnut Creek, California

Agrees with importance of clinical exam

I fully agree that clinical examination skill is a dying art. But the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has issued guidelines stating that pelvic examination is not required, especially in asymptomatic women. Another area of concern is hair removal procedures like waxing and laser treatments in the pubic area, and whether these do harm in any way or increase the likelihood of skin problems.

Manju Hotchandani, MD

New Delhi, India

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Alnaif, Moran, Richman, Gipps, and Hotchandani for sharing their comments and important clinical vignettes concerning the primacy of the physical examination with our readers. In clinical practice there are many competing demands on the time of clinicians, but we should strive to preserve time for a good physical examination. If not us, who is going to perform a competent physical examination?

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Rash goes undetected

As a urogynecologist, in the past 5 years I have had 2 urgent emergency department referrals from 2 towns. The patients had excruciating flank pain and had a negative computed tomography scan and normal pelvic and renal examinations, but no physical exam. They were subsequently found to have shingles!

Bunan Alnaif, MD

Chesapeake, Virginia

Physical exam revealed suspicious mass

Two years ago a regular gynecologic patient of mine came in 2 months early for her Pap test because she was concerned about a pressure in her genital area. I had delivered her 3 children. She was now in her mid-40s. She had visited her usual physician about the problem; she was not physically examined but was advised to see a gastrointestinal specialist, since the pressure caused constipation with discomfort. She then consulted a gastroenterologist, who performed a colonoscopy that was reported as normal. The patient related that she had no pelvic or rectal examination at that time, although it is possible that one could have been done while she was under anesthesia.

She arrived at my office 3 weeks later, and while doing the pelvic and rectal exam, I noted she had a 3- to 4-cm perirectal mass, which I thought was a Bartholin’s tumor. I referred her to a gynecologic oncologist who happened to write a paper on this subject. My diagnosis was wrong—she had a rectal carcinoma, which fortunately was Stage 1.

The patient subsequently has done well. The delay in diagnosis could have been averted if a simple rectal examination had been performed by the first doctor.

James Moran, MD

Santa Monica, California

Case of an almost missed diagnosis

I have many examples of how not performing a physical examination can cause problems, but here is a recent one. This involved a 70-year-old woman who had been seeing only her primary care physician for the past 30 years, with no pelvic examinations done. She had symptoms of vaginal discharge and itch for which she was given multiple courses of antifungals and topical steroids. Finally, she was referred to me. Examination revealed findings of extensive raised, erythematous, hyperkeratotic, macerated lesions throughout the vulva. A punch biopsy revealed severe vulvar dysplasia with areas suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma. I referred the patient to a gynecologic oncologist, who performed a simple vulvectomy. There were extensive foci of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3.

Susan Richman, MD

New Haven, Connecticut

Lack of physical exam leads to tortuous dx course

Here is a story of a patient who must have gone without having a pelvic examination or any evaluation for years. This 83-year-old woman had a previous transvaginal hysterectomy at age 49 for fibroids and bleeding. She is quite healthy and active for her age. She had problems with recurrent urinary tract infection for several years before being referred to a gynecologist. She had emergency room visits and multiple urgent care visits. She saw her primary care physician 3 times in 4 weeks for bladder pain and a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying. She reported that when she got up in the morning, it felt like her urine slowly leaked out for several hours. She was referred to a urologist, who saw her twice and did pelvic ultrasonography and postvoid residual urine testing—without a pelvic exam.

After 2 months of regular visits, an examination by her primary care physician revealed a complete fusion of the labia. Six months after her initial urology visit, the patient had an examination with a plan for cystoscopy, and the urologist ended up doing a “dilation of labial fusion” in the office. The patient’s urinary symptoms were improved slightly, and she had visits to the emergency room or urgent care once monthly for dysuria after dilation of the labia.

At that point she was referred to me. We tried topical estrogen for several months with minimal improvement in symptoms, and I performed a surgical separation of labial fusion in the operating room under monitored anesthesia care. After surgery the patient said that she felt like “I got my life back,” and she never knew how happy she could be to pee in the morning.

Theresa Gipps, MD

Walnut Creek, California

Agrees with importance of clinical exam

I fully agree that clinical examination skill is a dying art. But the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has issued guidelines stating that pelvic examination is not required, especially in asymptomatic women. Another area of concern is hair removal procedures like waxing and laser treatments in the pubic area, and whether these do harm in any way or increase the likelihood of skin problems.

Manju Hotchandani, MD

New Delhi, India

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Alnaif, Moran, Richman, Gipps, and Hotchandani for sharing their comments and important clinical vignettes concerning the primacy of the physical examination with our readers. In clinical practice there are many competing demands on the time of clinicians, but we should strive to preserve time for a good physical examination. If not us, who is going to perform a competent physical examination?

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Treatment includes surgery

Treatment includes surgery

Thank you for the great article about hidradenitis suppurativa. It was very informative as usual, but a little shortsighted. As ObGyns we tend not to focus so much on these dermatologic conditions. However, I think something very important is missing in the article. I do not see it mentioned that hidradenitis suppurativa is a type of acne, also called acne inversa. As such, it should be treated like acne, with special attention to diet with zero dairy products as a prevention measure. Also, metformin is very important, as noted in the article. Retinoids are also needed, maybe for years.

According to experts, the primary approach to this condition is surgical, with punch biopsies and unroofing of the lesions, with medical therapies as prevention strategies. Fortunately, special task forces are now tackling this condition, especially in Europe. I strongly recommend the book, Acne: Causes and Practical Management, by F. William Danby.

Ivan Valencia, MD

Quito, Ecuador

Dr. Barbieri responds

Dr. Valencia provides an important perspective on the surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). I agree that surgery is an important treatment for Stage III HS, but nonsurgical approaches are preferred and often effective for Stage I HS, a stage most likely to be treated by a gynecologist.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Treatment includes surgery

Thank you for the great article about hidradenitis suppurativa. It was very informative as usual, but a little shortsighted. As ObGyns we tend not to focus so much on these dermatologic conditions. However, I think something very important is missing in the article. I do not see it mentioned that hidradenitis suppurativa is a type of acne, also called acne inversa. As such, it should be treated like acne, with special attention to diet with zero dairy products as a prevention measure. Also, metformin is very important, as noted in the article. Retinoids are also needed, maybe for years.

According to experts, the primary approach to this condition is surgical, with punch biopsies and unroofing of the lesions, with medical therapies as prevention strategies. Fortunately, special task forces are now tackling this condition, especially in Europe. I strongly recommend the book, Acne: Causes and Practical Management, by F. William Danby.

Ivan Valencia, MD

Quito, Ecuador

Dr. Barbieri responds

Dr. Valencia provides an important perspective on the surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). I agree that surgery is an important treatment for Stage III HS, but nonsurgical approaches are preferred and often effective for Stage I HS, a stage most likely to be treated by a gynecologist.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Treatment includes surgery

Thank you for the great article about hidradenitis suppurativa. It was very informative as usual, but a little shortsighted. As ObGyns we tend not to focus so much on these dermatologic conditions. However, I think something very important is missing in the article. I do not see it mentioned that hidradenitis suppurativa is a type of acne, also called acne inversa. As such, it should be treated like acne, with special attention to diet with zero dairy products as a prevention measure. Also, metformin is very important, as noted in the article. Retinoids are also needed, maybe for years.

According to experts, the primary approach to this condition is surgical, with punch biopsies and unroofing of the lesions, with medical therapies as prevention strategies. Fortunately, special task forces are now tackling this condition, especially in Europe. I strongly recommend the book, Acne: Causes and Practical Management, by F. William Danby.

Ivan Valencia, MD

Quito, Ecuador

Dr. Barbieri responds

Dr. Valencia provides an important perspective on the surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). I agree that surgery is an important treatment for Stage III HS, but nonsurgical approaches are preferred and often effective for Stage I HS, a stage most likely to be treated by a gynecologist.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Incision site for cesarean delivery is important in infection prevention

Incision site for cesarean delivery is important in infection prevention

Dr. Barbieri’s editorial very nicely explained strategies to reduce the risk of post–cesarean delivery surgical site infection (SSI). However, what was not mentioned, in my opinion, is the most important preventive strategy. Selecting the site for the initial skin incision plays a great role in whether or not the patient will develop an infection postoperatively.

Pfannenstiel incisions are popular because of their obvious cosmetic benefit. In nonemergent cesarean deliveries, most ObGyns try to use this incision. However, exactly where the incision is placed plays a large role in the genesis of a postoperative wound infection. The worst place for such incisions is in the crease above the pubis and below the panniculus. Invariably, this area remains moist and macerated, especially in obese patients, thus providing a fertile breeding ground for bacteria. This problem can be avoided by incising the skin approximately 2 cm cranial to and parallel to the aforementioned crease, provided that the panniculus is not too large. The point is that the incision should be placed in an area where it has a chance to stay dry.

Sometimes patients who are hugely obese require great creativity in the placement of their transverse skin incision. I recall one patient, pregnant with triplets, whose abdomen was so large that her umbilicus was over the region of the lower uterine segment when she was supine on the operating room table. Some would have lifted up her immense panniculus and placed the incision in the usual crease site. This would be problematic for obtaining adequate exposure to deliver the babies, and the risk of developing an incisional infection would be very high. Therefore, a transverse incision was made just below her umbilicus. The panniculus was a nonissue regarding gaining adequate exposure and, when closed, the incision remained completely dry and uninfected. The patient did extremely well postoperatively and had no infectious sequelae.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Extraperitoneal approach should be considered

I enjoyed the editorial on reducing surgical site infection, especially the references to the historical Halsted principles of surgery. “He was the first in this country to promulgate the philosophy of ‘safe’ surgery.”1 Regarding surgical principles of cesarean delivery, the pioneering German obstetricians in the 1930s were keenly aware that avoiding the peritoneal cavity was instrumental in reducing morbidity and mortality. They championed the safety of the extraperitoneal approach as the fundamental principle of cesarean delivery for maternal safety.2

I learned to embrace the principles of Kaboth while learning the technique in 1968–1972. Thus, for more than 30 years, I used the extraperitoneal approach to access the lower uterine segment, avoiding entrance into the abdominal cavity. My patients seemed to benefit. As the surgeon, I also benefited: with short operative delivery times, less postoperative pain and minor morbidities, fewer phone calls from nursing staff, and less difficulty for my patients. I had not contaminated the peritoneal cavity and avoided all those inherent problems. The decision to open the peritoneal cavity has not been subjected to the rigors of critical analysis.3 I think that Kaboth’s principles remain worthy of consideration even today.

Contemporary experiences in large populations such as in India and China that use the extraperitoneal cesarean approach seem to implicitly support Kaboth’s principles. However, in the milieu of evidence-based medicine, extraperitoneal cesarean delivery has not been adequately studied.4 Just maybe the extraperitoneal approach should be considered and understood as a primary surgical technique for cesarean deliveries; just maybe it deserves a historical asterisk alongside the Halsted dicta.

Hedric Hanson, MD

Anchorage, Alaska

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Zisow and Hanson for their great recommendations and clinical pearls. I agree with Dr. Zisow that I should have mentioned the importance of optimal placement of the transverse skin incision. Incision in a skin crease that is perpetually moist increases the risk for a postoperative complication. When the abdomen is prepped for surgery, the skin crease above the pubis appears to be very inviting for placement of the skin incision. Dr. Hanson highlights the important option of an extraperitoneal approach to cesarean delivery. I have not thought about using this approach since the mid-1980s. Dr. Hanson’s recommendation that a randomized trial be performed comparing the SSI rate and other outcomes for extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal cesarean delivery is a great idea.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cameron JL. William Steward Halsted: our surgical heritage. Ann Surg. 1997;225(5):445–458.

- Kaboth G. Die Technik des extraperitonealen Entibindungschnittes. Zentralblatt fur Gynakologie.1934;58(6):310–311.

- Berghella V, Baxter JK Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1607–1617.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Mathai M, Shah AN, Novikova N. Techniques for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; CD004662.

Incision site for cesarean delivery is important in infection prevention

Dr. Barbieri’s editorial very nicely explained strategies to reduce the risk of post–cesarean delivery surgical site infection (SSI). However, what was not mentioned, in my opinion, is the most important preventive strategy. Selecting the site for the initial skin incision plays a great role in whether or not the patient will develop an infection postoperatively.

Pfannenstiel incisions are popular because of their obvious cosmetic benefit. In nonemergent cesarean deliveries, most ObGyns try to use this incision. However, exactly where the incision is placed plays a large role in the genesis of a postoperative wound infection. The worst place for such incisions is in the crease above the pubis and below the panniculus. Invariably, this area remains moist and macerated, especially in obese patients, thus providing a fertile breeding ground for bacteria. This problem can be avoided by incising the skin approximately 2 cm cranial to and parallel to the aforementioned crease, provided that the panniculus is not too large. The point is that the incision should be placed in an area where it has a chance to stay dry.

Sometimes patients who are hugely obese require great creativity in the placement of their transverse skin incision. I recall one patient, pregnant with triplets, whose abdomen was so large that her umbilicus was over the region of the lower uterine segment when she was supine on the operating room table. Some would have lifted up her immense panniculus and placed the incision in the usual crease site. This would be problematic for obtaining adequate exposure to deliver the babies, and the risk of developing an incisional infection would be very high. Therefore, a transverse incision was made just below her umbilicus. The panniculus was a nonissue regarding gaining adequate exposure and, when closed, the incision remained completely dry and uninfected. The patient did extremely well postoperatively and had no infectious sequelae.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Extraperitoneal approach should be considered

I enjoyed the editorial on reducing surgical site infection, especially the references to the historical Halsted principles of surgery. “He was the first in this country to promulgate the philosophy of ‘safe’ surgery.”1 Regarding surgical principles of cesarean delivery, the pioneering German obstetricians in the 1930s were keenly aware that avoiding the peritoneal cavity was instrumental in reducing morbidity and mortality. They championed the safety of the extraperitoneal approach as the fundamental principle of cesarean delivery for maternal safety.2

I learned to embrace the principles of Kaboth while learning the technique in 1968–1972. Thus, for more than 30 years, I used the extraperitoneal approach to access the lower uterine segment, avoiding entrance into the abdominal cavity. My patients seemed to benefit. As the surgeon, I also benefited: with short operative delivery times, less postoperative pain and minor morbidities, fewer phone calls from nursing staff, and less difficulty for my patients. I had not contaminated the peritoneal cavity and avoided all those inherent problems. The decision to open the peritoneal cavity has not been subjected to the rigors of critical analysis.3 I think that Kaboth’s principles remain worthy of consideration even today.

Contemporary experiences in large populations such as in India and China that use the extraperitoneal cesarean approach seem to implicitly support Kaboth’s principles. However, in the milieu of evidence-based medicine, extraperitoneal cesarean delivery has not been adequately studied.4 Just maybe the extraperitoneal approach should be considered and understood as a primary surgical technique for cesarean deliveries; just maybe it deserves a historical asterisk alongside the Halsted dicta.

Hedric Hanson, MD

Anchorage, Alaska

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Zisow and Hanson for their great recommendations and clinical pearls. I agree with Dr. Zisow that I should have mentioned the importance of optimal placement of the transverse skin incision. Incision in a skin crease that is perpetually moist increases the risk for a postoperative complication. When the abdomen is prepped for surgery, the skin crease above the pubis appears to be very inviting for placement of the skin incision. Dr. Hanson highlights the important option of an extraperitoneal approach to cesarean delivery. I have not thought about using this approach since the mid-1980s. Dr. Hanson’s recommendation that a randomized trial be performed comparing the SSI rate and other outcomes for extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal cesarean delivery is a great idea.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Incision site for cesarean delivery is important in infection prevention

Dr. Barbieri’s editorial very nicely explained strategies to reduce the risk of post–cesarean delivery surgical site infection (SSI). However, what was not mentioned, in my opinion, is the most important preventive strategy. Selecting the site for the initial skin incision plays a great role in whether or not the patient will develop an infection postoperatively.

Pfannenstiel incisions are popular because of their obvious cosmetic benefit. In nonemergent cesarean deliveries, most ObGyns try to use this incision. However, exactly where the incision is placed plays a large role in the genesis of a postoperative wound infection. The worst place for such incisions is in the crease above the pubis and below the panniculus. Invariably, this area remains moist and macerated, especially in obese patients, thus providing a fertile breeding ground for bacteria. This problem can be avoided by incising the skin approximately 2 cm cranial to and parallel to the aforementioned crease, provided that the panniculus is not too large. The point is that the incision should be placed in an area where it has a chance to stay dry.

Sometimes patients who are hugely obese require great creativity in the placement of their transverse skin incision. I recall one patient, pregnant with triplets, whose abdomen was so large that her umbilicus was over the region of the lower uterine segment when she was supine on the operating room table. Some would have lifted up her immense panniculus and placed the incision in the usual crease site. This would be problematic for obtaining adequate exposure to deliver the babies, and the risk of developing an incisional infection would be very high. Therefore, a transverse incision was made just below her umbilicus. The panniculus was a nonissue regarding gaining adequate exposure and, when closed, the incision remained completely dry and uninfected. The patient did extremely well postoperatively and had no infectious sequelae.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Extraperitoneal approach should be considered

I enjoyed the editorial on reducing surgical site infection, especially the references to the historical Halsted principles of surgery. “He was the first in this country to promulgate the philosophy of ‘safe’ surgery.”1 Regarding surgical principles of cesarean delivery, the pioneering German obstetricians in the 1930s were keenly aware that avoiding the peritoneal cavity was instrumental in reducing morbidity and mortality. They championed the safety of the extraperitoneal approach as the fundamental principle of cesarean delivery for maternal safety.2

I learned to embrace the principles of Kaboth while learning the technique in 1968–1972. Thus, for more than 30 years, I used the extraperitoneal approach to access the lower uterine segment, avoiding entrance into the abdominal cavity. My patients seemed to benefit. As the surgeon, I also benefited: with short operative delivery times, less postoperative pain and minor morbidities, fewer phone calls from nursing staff, and less difficulty for my patients. I had not contaminated the peritoneal cavity and avoided all those inherent problems. The decision to open the peritoneal cavity has not been subjected to the rigors of critical analysis.3 I think that Kaboth’s principles remain worthy of consideration even today.

Contemporary experiences in large populations such as in India and China that use the extraperitoneal cesarean approach seem to implicitly support Kaboth’s principles. However, in the milieu of evidence-based medicine, extraperitoneal cesarean delivery has not been adequately studied.4 Just maybe the extraperitoneal approach should be considered and understood as a primary surgical technique for cesarean deliveries; just maybe it deserves a historical asterisk alongside the Halsted dicta.

Hedric Hanson, MD

Anchorage, Alaska

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Zisow and Hanson for their great recommendations and clinical pearls. I agree with Dr. Zisow that I should have mentioned the importance of optimal placement of the transverse skin incision. Incision in a skin crease that is perpetually moist increases the risk for a postoperative complication. When the abdomen is prepped for surgery, the skin crease above the pubis appears to be very inviting for placement of the skin incision. Dr. Hanson highlights the important option of an extraperitoneal approach to cesarean delivery. I have not thought about using this approach since the mid-1980s. Dr. Hanson’s recommendation that a randomized trial be performed comparing the SSI rate and other outcomes for extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal cesarean delivery is a great idea.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cameron JL. William Steward Halsted: our surgical heritage. Ann Surg. 1997;225(5):445–458.

- Kaboth G. Die Technik des extraperitonealen Entibindungschnittes. Zentralblatt fur Gynakologie.1934;58(6):310–311.

- Berghella V, Baxter JK Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1607–1617.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Mathai M, Shah AN, Novikova N. Techniques for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; CD004662.

- Cameron JL. William Steward Halsted: our surgical heritage. Ann Surg. 1997;225(5):445–458.

- Kaboth G. Die Technik des extraperitonealen Entibindungschnittes. Zentralblatt fur Gynakologie.1934;58(6):310–311.

- Berghella V, Baxter JK Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1607–1617.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Mathai M, Shah AN, Novikova N. Techniques for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; CD004662.

Product Update: FUJIFILM; Freemie, Preventeza, and C-Panty

NEW VISUALIZATION SYSTEMS FROM FUJIFILM

FUJIFILM New Development, USA, has introduced 2 visualization systems for minimally invasive surgery. Using proprietary technology, the Ultra-Slim Video Laparoscope System (EL-580FN) delivers enhanced image resolution, color fidelity, and display quality, says FUJIFILM. The product features include “Chip on the Tip” high-definition digital imaging processing, less fogging, autoclave sterilization reprocessing, and a low profile, lightweight ergonomic handle. The 3.8-mm-diameter distal end was designed to improve workflow, reduce physician fatigue, and potentially reduce the size of incisions. The accompanying Digital Video Processor System is used for endoscopic procedures with automatic light control, an anti-blur function for motion images, and digital zoom.

FUJIFILM reports that the Full High Definition Surgical Visualization System is designed for a wide variety of surgical applications and offers edge enhancement, automatic gain control, dynamic contrast function, selective color enhancement, smoke reduction, and grid removal features. It includes a portfolio of rigid scopes, cameras, and video processing systems.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.fujifilmusa.com

FREEMIE BREAST MILK COLLECTION SYSTEM

Freemie® offers a hands-free breast-milk collection system with the Freemie Liberty Mobile Hands Free Breast Pump System and Next Generation Freemie Closed System Collection Cups.

The concealable pump has a rechargeable battery and hospital-power suction for single or double pumping. Programmable memory buttons allow the mother to preset or adjust speed and suction functions. Tubing lengths can be changed so that the pump can be placed on a desk, worn with a detachable belt clip, or carried in a bag.

Freemie says the cups are lower-profile and more compact than other pump system cups, and when placed on the breast under the mother’s bra, can be easily removed so that milk can be transferred to storage. Each cup, with a 25 mm or 28 mm funnel and valve, holds 8 oz of milk.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.freemie.com

PREVENTEZA: EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTIVE

Combe, Inc, the maker of Vagisil®, has launched Preventeza™ (levonorgestrel tablet, 1.5 mg), an emergency contraceptive for the prevention of pregnancy if unprotected sex or failed birth control occurs.

Available online or over-the-counter as a single tablet, Preventeza is a proven option to help women prevent pregnancy before it starts by using a higher dose of levonorgestrel than most birth control pills. It must be used within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, and is not intended to be used as regular birth control. Combe says that Preventeza works mainly by stopping the release of an egg from the ovary and may also prevent fertilization of an egg or prevent a fertilized egg from implanting in the uterus. Combe also says that levonorgestrel 1.5 mg will not work if the woman is already pregnant and will not affect an existing pregnancy.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.vagisil.com/products/preventeza-emergency-contraceptive

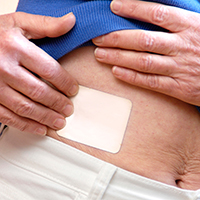

UPSPRING’S C-PANTY FOR POSTCESAREAN RECOVERY

UpSpring® says that its patented C-Panty® undergarment provides medical-grade compression and speeds recovery after cesarean delivery. C-Panty helps to reduce swelling and discomfort, supports weakened muscles, and reduces the incision bulge without hooks, straps, or Velcro that might irritate the incision area.

C-Panty’s medical-grade silicone panel suppresses the formation of excess or improperly formed collagen, which can contribute to scarring, says UpSpring. The silicone may help reduce itchiness, and can lessen the chance of infection at the incision area. The silicone is durable, washable, and integrated into the panty, eliminating the need for scar gel or scar gel pads.

The C-Panty can be worn immediately after birth and for up to 12 months. If worn when the incision is not healed, the silicone panel should be covered with a panty liner or pad. Once the incision has healed, the covering can be discontinued.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.upspringbaby.com/cpanty

NEW VISUALIZATION SYSTEMS FROM FUJIFILM

FUJIFILM New Development, USA, has introduced 2 visualization systems for minimally invasive surgery. Using proprietary technology, the Ultra-Slim Video Laparoscope System (EL-580FN) delivers enhanced image resolution, color fidelity, and display quality, says FUJIFILM. The product features include “Chip on the Tip” high-definition digital imaging processing, less fogging, autoclave sterilization reprocessing, and a low profile, lightweight ergonomic handle. The 3.8-mm-diameter distal end was designed to improve workflow, reduce physician fatigue, and potentially reduce the size of incisions. The accompanying Digital Video Processor System is used for endoscopic procedures with automatic light control, an anti-blur function for motion images, and digital zoom.

FUJIFILM reports that the Full High Definition Surgical Visualization System is designed for a wide variety of surgical applications and offers edge enhancement, automatic gain control, dynamic contrast function, selective color enhancement, smoke reduction, and grid removal features. It includes a portfolio of rigid scopes, cameras, and video processing systems.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.fujifilmusa.com

FREEMIE BREAST MILK COLLECTION SYSTEM

Freemie® offers a hands-free breast-milk collection system with the Freemie Liberty Mobile Hands Free Breast Pump System and Next Generation Freemie Closed System Collection Cups.

The concealable pump has a rechargeable battery and hospital-power suction for single or double pumping. Programmable memory buttons allow the mother to preset or adjust speed and suction functions. Tubing lengths can be changed so that the pump can be placed on a desk, worn with a detachable belt clip, or carried in a bag.

Freemie says the cups are lower-profile and more compact than other pump system cups, and when placed on the breast under the mother’s bra, can be easily removed so that milk can be transferred to storage. Each cup, with a 25 mm or 28 mm funnel and valve, holds 8 oz of milk.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.freemie.com

PREVENTEZA: EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTIVE

Combe, Inc, the maker of Vagisil®, has launched Preventeza™ (levonorgestrel tablet, 1.5 mg), an emergency contraceptive for the prevention of pregnancy if unprotected sex or failed birth control occurs.

Available online or over-the-counter as a single tablet, Preventeza is a proven option to help women prevent pregnancy before it starts by using a higher dose of levonorgestrel than most birth control pills. It must be used within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, and is not intended to be used as regular birth control. Combe says that Preventeza works mainly by stopping the release of an egg from the ovary and may also prevent fertilization of an egg or prevent a fertilized egg from implanting in the uterus. Combe also says that levonorgestrel 1.5 mg will not work if the woman is already pregnant and will not affect an existing pregnancy.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.vagisil.com/products/preventeza-emergency-contraceptive

UPSPRING’S C-PANTY FOR POSTCESAREAN RECOVERY

UpSpring® says that its patented C-Panty® undergarment provides medical-grade compression and speeds recovery after cesarean delivery. C-Panty helps to reduce swelling and discomfort, supports weakened muscles, and reduces the incision bulge without hooks, straps, or Velcro that might irritate the incision area.

C-Panty’s medical-grade silicone panel suppresses the formation of excess or improperly formed collagen, which can contribute to scarring, says UpSpring. The silicone may help reduce itchiness, and can lessen the chance of infection at the incision area. The silicone is durable, washable, and integrated into the panty, eliminating the need for scar gel or scar gel pads.

The C-Panty can be worn immediately after birth and for up to 12 months. If worn when the incision is not healed, the silicone panel should be covered with a panty liner or pad. Once the incision has healed, the covering can be discontinued.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.upspringbaby.com/cpanty

NEW VISUALIZATION SYSTEMS FROM FUJIFILM

FUJIFILM New Development, USA, has introduced 2 visualization systems for minimally invasive surgery. Using proprietary technology, the Ultra-Slim Video Laparoscope System (EL-580FN) delivers enhanced image resolution, color fidelity, and display quality, says FUJIFILM. The product features include “Chip on the Tip” high-definition digital imaging processing, less fogging, autoclave sterilization reprocessing, and a low profile, lightweight ergonomic handle. The 3.8-mm-diameter distal end was designed to improve workflow, reduce physician fatigue, and potentially reduce the size of incisions. The accompanying Digital Video Processor System is used for endoscopic procedures with automatic light control, an anti-blur function for motion images, and digital zoom.

FUJIFILM reports that the Full High Definition Surgical Visualization System is designed for a wide variety of surgical applications and offers edge enhancement, automatic gain control, dynamic contrast function, selective color enhancement, smoke reduction, and grid removal features. It includes a portfolio of rigid scopes, cameras, and video processing systems.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.fujifilmusa.com

FREEMIE BREAST MILK COLLECTION SYSTEM

Freemie® offers a hands-free breast-milk collection system with the Freemie Liberty Mobile Hands Free Breast Pump System and Next Generation Freemie Closed System Collection Cups.

The concealable pump has a rechargeable battery and hospital-power suction for single or double pumping. Programmable memory buttons allow the mother to preset or adjust speed and suction functions. Tubing lengths can be changed so that the pump can be placed on a desk, worn with a detachable belt clip, or carried in a bag.

Freemie says the cups are lower-profile and more compact than other pump system cups, and when placed on the breast under the mother’s bra, can be easily removed so that milk can be transferred to storage. Each cup, with a 25 mm or 28 mm funnel and valve, holds 8 oz of milk.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.freemie.com