User login

FDA Approves Skyrizi for Ulcerative Colitis

This approval makes it the first specific anti-interleukin 23 monoclonal antibody indicated for both ulcerative colitis and moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

The drug is also approved in the United States for the treatment of adults with active psoriatic arthritis and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

The safety and efficacy of Skyrizi for ulcerative colitis is supported by data from two phase 3 clinical trials: a 12-week induction study (INSPIRE) and a 52-week maintenance study (COMMAND).

The data showed that clinical remission, the primary endpoint in both the induction and maintenance studies, was achieved along with endoscopic improvement, which was a key secondary endpoint.

“When treating patients with ulcerative colitis, it’s important to prioritize both early and sustained clinical remission as well as endoscopic improvement,” Edward V. Loftus Jr., MD, AGAF, gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said in a news release. “This approval for Skyrizi is an important step toward addressing these treatment goals.”

For the treatment of ulcerative colitis, dosing includes a 12-week induction period with three 1200-mg doses delivered every 4 weeks followed by maintenance therapy of either 180 mg or 360 mg delivered every 8 weeks.

After the induction period, Skyrizi treatment can be maintained at home using an on-body injector (OBI). “The OBI is a hands-free device designed with patients in mind that adheres to the body and takes about 5 minutes to deliver the medication following preparation steps,” according to the news release.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This approval makes it the first specific anti-interleukin 23 monoclonal antibody indicated for both ulcerative colitis and moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

The drug is also approved in the United States for the treatment of adults with active psoriatic arthritis and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

The safety and efficacy of Skyrizi for ulcerative colitis is supported by data from two phase 3 clinical trials: a 12-week induction study (INSPIRE) and a 52-week maintenance study (COMMAND).

The data showed that clinical remission, the primary endpoint in both the induction and maintenance studies, was achieved along with endoscopic improvement, which was a key secondary endpoint.

“When treating patients with ulcerative colitis, it’s important to prioritize both early and sustained clinical remission as well as endoscopic improvement,” Edward V. Loftus Jr., MD, AGAF, gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said in a news release. “This approval for Skyrizi is an important step toward addressing these treatment goals.”

For the treatment of ulcerative colitis, dosing includes a 12-week induction period with three 1200-mg doses delivered every 4 weeks followed by maintenance therapy of either 180 mg or 360 mg delivered every 8 weeks.

After the induction period, Skyrizi treatment can be maintained at home using an on-body injector (OBI). “The OBI is a hands-free device designed with patients in mind that adheres to the body and takes about 5 minutes to deliver the medication following preparation steps,” according to the news release.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This approval makes it the first specific anti-interleukin 23 monoclonal antibody indicated for both ulcerative colitis and moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

The drug is also approved in the United States for the treatment of adults with active psoriatic arthritis and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

The safety and efficacy of Skyrizi for ulcerative colitis is supported by data from two phase 3 clinical trials: a 12-week induction study (INSPIRE) and a 52-week maintenance study (COMMAND).

The data showed that clinical remission, the primary endpoint in both the induction and maintenance studies, was achieved along with endoscopic improvement, which was a key secondary endpoint.

“When treating patients with ulcerative colitis, it’s important to prioritize both early and sustained clinical remission as well as endoscopic improvement,” Edward V. Loftus Jr., MD, AGAF, gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said in a news release. “This approval for Skyrizi is an important step toward addressing these treatment goals.”

For the treatment of ulcerative colitis, dosing includes a 12-week induction period with three 1200-mg doses delivered every 4 weeks followed by maintenance therapy of either 180 mg or 360 mg delivered every 8 weeks.

After the induction period, Skyrizi treatment can be maintained at home using an on-body injector (OBI). “The OBI is a hands-free device designed with patients in mind that adheres to the body and takes about 5 minutes to deliver the medication following preparation steps,” according to the news release.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Autonomous AI Outperforms Humans in Optical Diagnosis of Colorectal Polyps

, while providing greater alignment with pathology-based surveillance intervals, based on a randomized controlled trial.

These findings suggest that autonomous AI may one day replace histologic assessment of diminutive polyps, reported lead author Roupen Djinbachian, MD, of the Montreal University Hospital Research Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and colleagues.Optical diagnosis of diminutive colorectal polyps has been proposed as a cost-effective alternative to histologic diagnosis, but its implementation in general clinical practice has been hindered by endoscopists’ concerns about incorrect diagnoses, the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.“AI-based systems (CADx) have been proposed as a solution to these barriers to implementation, with studies showing high adherence to Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) thresholds when using AI-H,” they wrote. “However, the efficacy and safety of autonomous AI-based diagnostic platforms have not yet been evaluated.”

To address this knowledge gap, Dr. Djinbachian and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled noninferiority trial involving 467 patients, all of whom underwent elective colonoscopies at a single academic institution.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first group received an optical diagnosis of diminutive (1-5 mm) colorectal polyps using an autonomous AI-based CADx system without any human input. The second group had diagnoses performed by endoscopists who used AI-H to make their optical diagnoses.

The primary outcome was the accuracy of optical diagnosis compared with the gold standard of histologic evaluation. Secondarily, the investigators explored associations between pathology-based surveillance intervals and various measures of accuracy, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

The results showed that the accuracy of optical diagnosis for diminutive polyps was similar between the two groups, supporting noninferiority. Autonomous AI achieved an accuracy rate of 77.2%, while the AI-H group had an accuracy of 72.1%, which was not statistically significant (P = .86).

But when it came to pathology-based surveillance intervals, autonomous AI showed a clear advantage; the autonomous AI system achieved a 91.5% agreement rate, compared with 82.1% for the AI-H group (P = .016).

“These findings indicate that autonomous AI not only matches but also surpasses AI-H in accuracy for determining surveillance intervals,” the investigators wrote, noting that this finding highlights the “complexities of human interaction with AI modules where human intervention could lead to worse outcomes.”

Further analysis revealed that the sensitivity of autonomous AI for identifying adenomas was 84.8%, slightly higher than the 83.6% sensitivity of the AI-H group. Specificity was 64.4% for autonomous AI vs 63.8% for AI-H. While PPV was higher in the autonomous AI group (85.6%), compared with the AI-H group (78.6%), NPV was lower for autonomous AI than AI-H (63.0% vs 71.0%).

Dr. Djinbachian and colleagues suggested that future research should focus on larger, multicenter trials to validate these findings and further explore the integration of autonomous AI systems in clinical practice. They also noted that improving AI algorithms to accurately diagnose sessile serrated lesions could enhance the overall effectiveness of AI-based optical diagnosis.

“The performance of autonomous AI in accurately diagnosing diminutive polyps and determining appropriate surveillance intervals suggests that it could play a crucial role in streamlining colorectal cancer screening processes, reducing the burden on pathologists, and potentially lowering healthcare costs,” the investigators concluded.The study was supported by Fujifilm, which had no role in the study design or data analysis. Dr. von Renteln reported additional research funding from Vantage and Fujifilm.

In the era of computer vision for endoscopy and colonoscopy, current paradigms rely on AI as a co-pilot or second observer, with the physician serving as the final arbiter in procedure-related decision-making. This study by Djinbachian and Haumesser et al brings up the interesting wrinkle of autonomous AI as a potentially superior (or noninferior) option in narrow, task-specific use cases.

In this study, human input from the endoscopist after CADx diagnosis led to lower agreement between the AI-predicted diagnosis and corresponding surveillance intervals; human oversight more often incorrectly changed the resultant diagnosis and led to shorter than recommended surveillance intervals.

This study offers a small but very important update to the growing body of literature on CADx in colonoscopy. So far, prospective validation of CADx compared with the human eye for in-situ diagnosis of polyps has provided mixed results. This study is one of the first to examine the potential role of “automatic” CADx without additional human input and sheds light on the importance of the AI-human hybrid in medical care. How do the ways in which humans interact with the user interface and output of AI lead to changes in outcome? How can we optimize the AI-human interaction in order to provide optimal results?

Jeremy R. Glissen Brown is an assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine and Division of Gastroenterology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina. He has served as a consultant for Medtronic and Olympus, and on the advisory board for Odin Vision.

In the era of computer vision for endoscopy and colonoscopy, current paradigms rely on AI as a co-pilot or second observer, with the physician serving as the final arbiter in procedure-related decision-making. This study by Djinbachian and Haumesser et al brings up the interesting wrinkle of autonomous AI as a potentially superior (or noninferior) option in narrow, task-specific use cases.

In this study, human input from the endoscopist after CADx diagnosis led to lower agreement between the AI-predicted diagnosis and corresponding surveillance intervals; human oversight more often incorrectly changed the resultant diagnosis and led to shorter than recommended surveillance intervals.

This study offers a small but very important update to the growing body of literature on CADx in colonoscopy. So far, prospective validation of CADx compared with the human eye for in-situ diagnosis of polyps has provided mixed results. This study is one of the first to examine the potential role of “automatic” CADx without additional human input and sheds light on the importance of the AI-human hybrid in medical care. How do the ways in which humans interact with the user interface and output of AI lead to changes in outcome? How can we optimize the AI-human interaction in order to provide optimal results?

Jeremy R. Glissen Brown is an assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine and Division of Gastroenterology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina. He has served as a consultant for Medtronic and Olympus, and on the advisory board for Odin Vision.

In the era of computer vision for endoscopy and colonoscopy, current paradigms rely on AI as a co-pilot or second observer, with the physician serving as the final arbiter in procedure-related decision-making. This study by Djinbachian and Haumesser et al brings up the interesting wrinkle of autonomous AI as a potentially superior (or noninferior) option in narrow, task-specific use cases.

In this study, human input from the endoscopist after CADx diagnosis led to lower agreement between the AI-predicted diagnosis and corresponding surveillance intervals; human oversight more often incorrectly changed the resultant diagnosis and led to shorter than recommended surveillance intervals.

This study offers a small but very important update to the growing body of literature on CADx in colonoscopy. So far, prospective validation of CADx compared with the human eye for in-situ diagnosis of polyps has provided mixed results. This study is one of the first to examine the potential role of “automatic” CADx without additional human input and sheds light on the importance of the AI-human hybrid in medical care. How do the ways in which humans interact with the user interface and output of AI lead to changes in outcome? How can we optimize the AI-human interaction in order to provide optimal results?

Jeremy R. Glissen Brown is an assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine and Division of Gastroenterology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina. He has served as a consultant for Medtronic and Olympus, and on the advisory board for Odin Vision.

, while providing greater alignment with pathology-based surveillance intervals, based on a randomized controlled trial.

These findings suggest that autonomous AI may one day replace histologic assessment of diminutive polyps, reported lead author Roupen Djinbachian, MD, of the Montreal University Hospital Research Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and colleagues.Optical diagnosis of diminutive colorectal polyps has been proposed as a cost-effective alternative to histologic diagnosis, but its implementation in general clinical practice has been hindered by endoscopists’ concerns about incorrect diagnoses, the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.“AI-based systems (CADx) have been proposed as a solution to these barriers to implementation, with studies showing high adherence to Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) thresholds when using AI-H,” they wrote. “However, the efficacy and safety of autonomous AI-based diagnostic platforms have not yet been evaluated.”

To address this knowledge gap, Dr. Djinbachian and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled noninferiority trial involving 467 patients, all of whom underwent elective colonoscopies at a single academic institution.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first group received an optical diagnosis of diminutive (1-5 mm) colorectal polyps using an autonomous AI-based CADx system without any human input. The second group had diagnoses performed by endoscopists who used AI-H to make their optical diagnoses.

The primary outcome was the accuracy of optical diagnosis compared with the gold standard of histologic evaluation. Secondarily, the investigators explored associations between pathology-based surveillance intervals and various measures of accuracy, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

The results showed that the accuracy of optical diagnosis for diminutive polyps was similar between the two groups, supporting noninferiority. Autonomous AI achieved an accuracy rate of 77.2%, while the AI-H group had an accuracy of 72.1%, which was not statistically significant (P = .86).

But when it came to pathology-based surveillance intervals, autonomous AI showed a clear advantage; the autonomous AI system achieved a 91.5% agreement rate, compared with 82.1% for the AI-H group (P = .016).

“These findings indicate that autonomous AI not only matches but also surpasses AI-H in accuracy for determining surveillance intervals,” the investigators wrote, noting that this finding highlights the “complexities of human interaction with AI modules where human intervention could lead to worse outcomes.”

Further analysis revealed that the sensitivity of autonomous AI for identifying adenomas was 84.8%, slightly higher than the 83.6% sensitivity of the AI-H group. Specificity was 64.4% for autonomous AI vs 63.8% for AI-H. While PPV was higher in the autonomous AI group (85.6%), compared with the AI-H group (78.6%), NPV was lower for autonomous AI than AI-H (63.0% vs 71.0%).

Dr. Djinbachian and colleagues suggested that future research should focus on larger, multicenter trials to validate these findings and further explore the integration of autonomous AI systems in clinical practice. They also noted that improving AI algorithms to accurately diagnose sessile serrated lesions could enhance the overall effectiveness of AI-based optical diagnosis.

“The performance of autonomous AI in accurately diagnosing diminutive polyps and determining appropriate surveillance intervals suggests that it could play a crucial role in streamlining colorectal cancer screening processes, reducing the burden on pathologists, and potentially lowering healthcare costs,” the investigators concluded.The study was supported by Fujifilm, which had no role in the study design or data analysis. Dr. von Renteln reported additional research funding from Vantage and Fujifilm.

, while providing greater alignment with pathology-based surveillance intervals, based on a randomized controlled trial.

These findings suggest that autonomous AI may one day replace histologic assessment of diminutive polyps, reported lead author Roupen Djinbachian, MD, of the Montreal University Hospital Research Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and colleagues.Optical diagnosis of diminutive colorectal polyps has been proposed as a cost-effective alternative to histologic diagnosis, but its implementation in general clinical practice has been hindered by endoscopists’ concerns about incorrect diagnoses, the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.“AI-based systems (CADx) have been proposed as a solution to these barriers to implementation, with studies showing high adherence to Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) thresholds when using AI-H,” they wrote. “However, the efficacy and safety of autonomous AI-based diagnostic platforms have not yet been evaluated.”

To address this knowledge gap, Dr. Djinbachian and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled noninferiority trial involving 467 patients, all of whom underwent elective colonoscopies at a single academic institution.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first group received an optical diagnosis of diminutive (1-5 mm) colorectal polyps using an autonomous AI-based CADx system without any human input. The second group had diagnoses performed by endoscopists who used AI-H to make their optical diagnoses.

The primary outcome was the accuracy of optical diagnosis compared with the gold standard of histologic evaluation. Secondarily, the investigators explored associations between pathology-based surveillance intervals and various measures of accuracy, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

The results showed that the accuracy of optical diagnosis for diminutive polyps was similar between the two groups, supporting noninferiority. Autonomous AI achieved an accuracy rate of 77.2%, while the AI-H group had an accuracy of 72.1%, which was not statistically significant (P = .86).

But when it came to pathology-based surveillance intervals, autonomous AI showed a clear advantage; the autonomous AI system achieved a 91.5% agreement rate, compared with 82.1% for the AI-H group (P = .016).

“These findings indicate that autonomous AI not only matches but also surpasses AI-H in accuracy for determining surveillance intervals,” the investigators wrote, noting that this finding highlights the “complexities of human interaction with AI modules where human intervention could lead to worse outcomes.”

Further analysis revealed that the sensitivity of autonomous AI for identifying adenomas was 84.8%, slightly higher than the 83.6% sensitivity of the AI-H group. Specificity was 64.4% for autonomous AI vs 63.8% for AI-H. While PPV was higher in the autonomous AI group (85.6%), compared with the AI-H group (78.6%), NPV was lower for autonomous AI than AI-H (63.0% vs 71.0%).

Dr. Djinbachian and colleagues suggested that future research should focus on larger, multicenter trials to validate these findings and further explore the integration of autonomous AI systems in clinical practice. They also noted that improving AI algorithms to accurately diagnose sessile serrated lesions could enhance the overall effectiveness of AI-based optical diagnosis.

“The performance of autonomous AI in accurately diagnosing diminutive polyps and determining appropriate surveillance intervals suggests that it could play a crucial role in streamlining colorectal cancer screening processes, reducing the burden on pathologists, and potentially lowering healthcare costs,” the investigators concluded.The study was supported by Fujifilm, which had no role in the study design or data analysis. Dr. von Renteln reported additional research funding from Vantage and Fujifilm.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Targeting Enteroendocrine Cells Could Hold Promise for IBD

, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that restoring EEC function could alleviate some of the more general abdominal symptoms associated with IBD, reported lead author Zachariah Raouf, MD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“The symptoms experienced by patients with IBD, especially ulcerative colitis, may include those that are colonic in nature, such as bloody stools, abdominal pain, and weight loss, as well as those that are more general in nature, such as severe nausea and abdominal bloating,” the investigators wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology . “Although the first set of symptoms may be attributable to the effects of colonic inflammation itself, those that are more vague seem to overlap with the symptoms that patients with small intestinal dysmotility experience, such as occur in response to medications, or diabetes.”

Supporting this notion, several previous studies have reported the onset of intestinal dysmotility in experimental models of colitis, which is believed to be caused by impaired enteric nervous system function. But the precise mechanisms behind the impaired intestinal motility observed in colitis patients remain unclear.

To learn more, Dr. Raouf and colleagues conducted experiments involving three groups of mice: wild-type mice, mice genetically engineered to overexpress EECs, and mice lacking EECs.

To induce colitis, the mice were administered dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water at concentrations of 2.5% or 5% for 7 days. Small intestinal motility was evaluated by measuring the transit of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran. Immunohistochemical analyses were conducted to assess EEC number and differentiation, while quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was used to examine the expression of genes related to serotonin synthesis and transport.

The researchers examined colon length and signs of colonic inflammation, monitored weight loss, and measured the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Histological analyses of colon and small intestine tissues were performed to further understand the effects of colitis. The presence and number of EEC cells was evaluated using chromogranin A (ChgA) staining, while apoptosis in EECs was measured via TUNEL staining. The expression of serotonin-related genes was also assessed.

These experiments revealed that DSS-induced colitis led to significant small-bowel hypomotility and a reduction in EEC density. Of note, genetic overexpression of EECs or treatment with prucalopride, a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 agonist, improved small intestinal motility.

“It is noteworthy that there were no significant changes in the density of other intestinal epithelial cells, or in other cell types that are linked to motility, such as enteric glia and neurons, suggesting the specificity of the effect,” the investigators wrote. “Importantly, treatment with a serotonin agonist ameliorated the colitis-induced, small-bowel hypomotility and attenuated the severity of colitis, providing potential clinical relevance of the current findings. Taken together, these results identify mechanisms to explain the intestinal hypomotility observed in the setting of colitis.”Dr. Raouf and colleagues called for human clinical trials to their findings. Specifically, they suggested exploring therapies targeting enteroendocrine cells or serotonin pathways and examining the role of different EEC types in gut motility during inflammation. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) typically manifests with colonic symptoms but is also associated with intestinal inflammation and dysmotility of the small intestine. Clinical research debates whether IBD causes small intestine hypermotility or hypomotility, but these motility dysfunctions are often attributed to alterations of the gut’s intrinsic nervous system.

Dr. Raouf and colleagues focus on the role of enteroendocrine cells, an epithelial cell subtype with neuron-like features that secrete serotonin, one of the most important regulators of intestinal motility. Their population is reduced in colitis, and the subsequent alteration of serotonin signaling induces small intestine dysmotility. The observed loss of enteroendocrine cells in the small bowel may result from low-grade local inflammation increasing enteroendocrine cell apoptosis, or impaired gene expression in their differentiation pathways. However, more research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of this loss.

This study enhances our understanding of the small intestine dysfunction associated with colitis and raises the exciting possibility of enteroendocrine cell-based therapeutic approaches in IBD.

Jacques A. Gonzales, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Gulbransen laboratory at Michigan State University, East Lansing. He has no conflicts of interest.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) typically manifests with colonic symptoms but is also associated with intestinal inflammation and dysmotility of the small intestine. Clinical research debates whether IBD causes small intestine hypermotility or hypomotility, but these motility dysfunctions are often attributed to alterations of the gut’s intrinsic nervous system.

Dr. Raouf and colleagues focus on the role of enteroendocrine cells, an epithelial cell subtype with neuron-like features that secrete serotonin, one of the most important regulators of intestinal motility. Their population is reduced in colitis, and the subsequent alteration of serotonin signaling induces small intestine dysmotility. The observed loss of enteroendocrine cells in the small bowel may result from low-grade local inflammation increasing enteroendocrine cell apoptosis, or impaired gene expression in their differentiation pathways. However, more research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of this loss.

This study enhances our understanding of the small intestine dysfunction associated with colitis and raises the exciting possibility of enteroendocrine cell-based therapeutic approaches in IBD.

Jacques A. Gonzales, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Gulbransen laboratory at Michigan State University, East Lansing. He has no conflicts of interest.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) typically manifests with colonic symptoms but is also associated with intestinal inflammation and dysmotility of the small intestine. Clinical research debates whether IBD causes small intestine hypermotility or hypomotility, but these motility dysfunctions are often attributed to alterations of the gut’s intrinsic nervous system.

Dr. Raouf and colleagues focus on the role of enteroendocrine cells, an epithelial cell subtype with neuron-like features that secrete serotonin, one of the most important regulators of intestinal motility. Their population is reduced in colitis, and the subsequent alteration of serotonin signaling induces small intestine dysmotility. The observed loss of enteroendocrine cells in the small bowel may result from low-grade local inflammation increasing enteroendocrine cell apoptosis, or impaired gene expression in their differentiation pathways. However, more research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of this loss.

This study enhances our understanding of the small intestine dysfunction associated with colitis and raises the exciting possibility of enteroendocrine cell-based therapeutic approaches in IBD.

Jacques A. Gonzales, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Gulbransen laboratory at Michigan State University, East Lansing. He has no conflicts of interest.

, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that restoring EEC function could alleviate some of the more general abdominal symptoms associated with IBD, reported lead author Zachariah Raouf, MD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“The symptoms experienced by patients with IBD, especially ulcerative colitis, may include those that are colonic in nature, such as bloody stools, abdominal pain, and weight loss, as well as those that are more general in nature, such as severe nausea and abdominal bloating,” the investigators wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology . “Although the first set of symptoms may be attributable to the effects of colonic inflammation itself, those that are more vague seem to overlap with the symptoms that patients with small intestinal dysmotility experience, such as occur in response to medications, or diabetes.”

Supporting this notion, several previous studies have reported the onset of intestinal dysmotility in experimental models of colitis, which is believed to be caused by impaired enteric nervous system function. But the precise mechanisms behind the impaired intestinal motility observed in colitis patients remain unclear.

To learn more, Dr. Raouf and colleagues conducted experiments involving three groups of mice: wild-type mice, mice genetically engineered to overexpress EECs, and mice lacking EECs.

To induce colitis, the mice were administered dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water at concentrations of 2.5% or 5% for 7 days. Small intestinal motility was evaluated by measuring the transit of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran. Immunohistochemical analyses were conducted to assess EEC number and differentiation, while quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was used to examine the expression of genes related to serotonin synthesis and transport.

The researchers examined colon length and signs of colonic inflammation, monitored weight loss, and measured the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Histological analyses of colon and small intestine tissues were performed to further understand the effects of colitis. The presence and number of EEC cells was evaluated using chromogranin A (ChgA) staining, while apoptosis in EECs was measured via TUNEL staining. The expression of serotonin-related genes was also assessed.

These experiments revealed that DSS-induced colitis led to significant small-bowel hypomotility and a reduction in EEC density. Of note, genetic overexpression of EECs or treatment with prucalopride, a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 agonist, improved small intestinal motility.

“It is noteworthy that there were no significant changes in the density of other intestinal epithelial cells, or in other cell types that are linked to motility, such as enteric glia and neurons, suggesting the specificity of the effect,” the investigators wrote. “Importantly, treatment with a serotonin agonist ameliorated the colitis-induced, small-bowel hypomotility and attenuated the severity of colitis, providing potential clinical relevance of the current findings. Taken together, these results identify mechanisms to explain the intestinal hypomotility observed in the setting of colitis.”Dr. Raouf and colleagues called for human clinical trials to their findings. Specifically, they suggested exploring therapies targeting enteroendocrine cells or serotonin pathways and examining the role of different EEC types in gut motility during inflammation. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that restoring EEC function could alleviate some of the more general abdominal symptoms associated with IBD, reported lead author Zachariah Raouf, MD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“The symptoms experienced by patients with IBD, especially ulcerative colitis, may include those that are colonic in nature, such as bloody stools, abdominal pain, and weight loss, as well as those that are more general in nature, such as severe nausea and abdominal bloating,” the investigators wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology . “Although the first set of symptoms may be attributable to the effects of colonic inflammation itself, those that are more vague seem to overlap with the symptoms that patients with small intestinal dysmotility experience, such as occur in response to medications, or diabetes.”

Supporting this notion, several previous studies have reported the onset of intestinal dysmotility in experimental models of colitis, which is believed to be caused by impaired enteric nervous system function. But the precise mechanisms behind the impaired intestinal motility observed in colitis patients remain unclear.

To learn more, Dr. Raouf and colleagues conducted experiments involving three groups of mice: wild-type mice, mice genetically engineered to overexpress EECs, and mice lacking EECs.

To induce colitis, the mice were administered dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water at concentrations of 2.5% or 5% for 7 days. Small intestinal motility was evaluated by measuring the transit of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran. Immunohistochemical analyses were conducted to assess EEC number and differentiation, while quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was used to examine the expression of genes related to serotonin synthesis and transport.

The researchers examined colon length and signs of colonic inflammation, monitored weight loss, and measured the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Histological analyses of colon and small intestine tissues were performed to further understand the effects of colitis. The presence and number of EEC cells was evaluated using chromogranin A (ChgA) staining, while apoptosis in EECs was measured via TUNEL staining. The expression of serotonin-related genes was also assessed.

These experiments revealed that DSS-induced colitis led to significant small-bowel hypomotility and a reduction in EEC density. Of note, genetic overexpression of EECs or treatment with prucalopride, a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 agonist, improved small intestinal motility.

“It is noteworthy that there were no significant changes in the density of other intestinal epithelial cells, or in other cell types that are linked to motility, such as enteric glia and neurons, suggesting the specificity of the effect,” the investigators wrote. “Importantly, treatment with a serotonin agonist ameliorated the colitis-induced, small-bowel hypomotility and attenuated the severity of colitis, providing potential clinical relevance of the current findings. Taken together, these results identify mechanisms to explain the intestinal hypomotility observed in the setting of colitis.”Dr. Raouf and colleagues called for human clinical trials to their findings. Specifically, they suggested exploring therapies targeting enteroendocrine cells or serotonin pathways and examining the role of different EEC types in gut motility during inflammation. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Gastroenterology Data Trends 2024

In this issue:

- Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Beyond EoE

Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, AGAF, FACG - The Changing Face of IBD: Beyond the Western World

Gilaad G. Kaplan, MD, MPH, AGAF; Paulo Kotze, MD, MS, PhD; Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, AGAF - Role of Non-invasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of MASLD

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH - The Emerging Role of Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis and Management of CRC

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF - Cannabinoids and Digestive Disorders

Jami A. Kinnucan, MD, AGAF, FACG - AI and Machine Learning in IBD: Promising Applications and Remaining Challenges

Shirley Cohen-Mekelburg, MD, MS - Simulation-Based Training in Endoscopy: Benefits and Challenges

Richa Shukla, MD - Fluid Management in Acute Pancreatitis

Jorge D. Machicado, MD, MPH

In this issue:

- Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Beyond EoE

Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, AGAF, FACG - The Changing Face of IBD: Beyond the Western World

Gilaad G. Kaplan, MD, MPH, AGAF; Paulo Kotze, MD, MS, PhD; Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, AGAF - Role of Non-invasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of MASLD

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH - The Emerging Role of Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis and Management of CRC

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF - Cannabinoids and Digestive Disorders

Jami A. Kinnucan, MD, AGAF, FACG - AI and Machine Learning in IBD: Promising Applications and Remaining Challenges

Shirley Cohen-Mekelburg, MD, MS - Simulation-Based Training in Endoscopy: Benefits and Challenges

Richa Shukla, MD - Fluid Management in Acute Pancreatitis

Jorge D. Machicado, MD, MPH

In this issue:

- Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Beyond EoE

Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, AGAF, FACG - The Changing Face of IBD: Beyond the Western World

Gilaad G. Kaplan, MD, MPH, AGAF; Paulo Kotze, MD, MS, PhD; Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, AGAF - Role of Non-invasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of MASLD

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH - The Emerging Role of Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis and Management of CRC

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF - Cannabinoids and Digestive Disorders

Jami A. Kinnucan, MD, AGAF, FACG - AI and Machine Learning in IBD: Promising Applications and Remaining Challenges

Shirley Cohen-Mekelburg, MD, MS - Simulation-Based Training in Endoscopy: Benefits and Challenges

Richa Shukla, MD - Fluid Management in Acute Pancreatitis

Jorge D. Machicado, MD, MPH

Cannabinoids and Digestive Disorders

- Leung J, Chan G, Stjepanović D, Chung JYC, Hall W, Hammond D. Prevalence and self-reported reasons of cannabis use for medical purposes in USA and Canada. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239(5):1509-1519. doi:10.1007/s00213-021-06047-8

- Ahmed W, Katz S. Therapeutic use of cannabis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2016;12(11):668-679.

- Ravikoff Allegretti J, Courtwright A, Lucci M, Korzenik JR, Levine J. Marijuana use patterns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(13):2809-2814. doi:10.1097/01.MIB.0000435851.94391.37

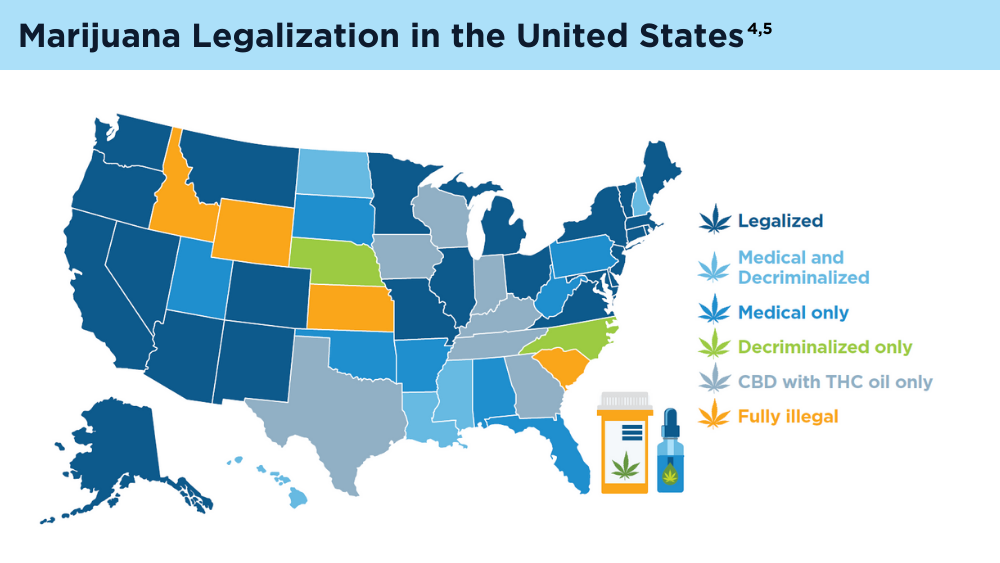

- Marijuana legality by state - updated February 1, 2024. DISA. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://disa.com/marijuana-legality-by-state

- The Cannigma Staff. Where is weed legal around the globe? The Cannigma. Updated July 3, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://cannigma.com/regulation/cannabis-regulation-around-the-world/

- Zou S, Kumar U. Cannabinoid receptors and the endocannabinoid system: signaling and function in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):833. doi:10.3390/ijms19030833

- Maselli DB, Camilleri M. Pharmacology, clinical effects, and therapeutic potential of cannabinoids for gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(9):1748-1758.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.020

- Buckley MC, Kumar A, Swaminath A. Inflammatory bowel disease and cannabis: a practical approach for clinicians. Adv Ther. 2021;38(7):4152- 4161. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01805-8

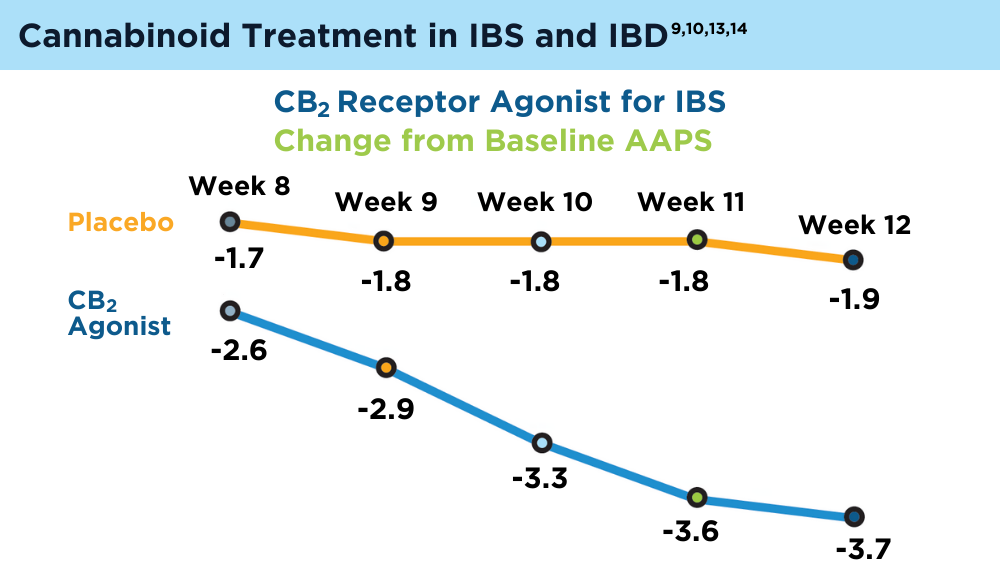

- Chang L, Cash BD, Lembo A, et al. Efficacy and safety of olorinab, a full agonist of the cannabinoid receptor 2, for the treatment of abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a phase 2b randomized placebo-controlled trial (CAPTIVATE). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(5):e14539. doi:10.1111/nmo.14539

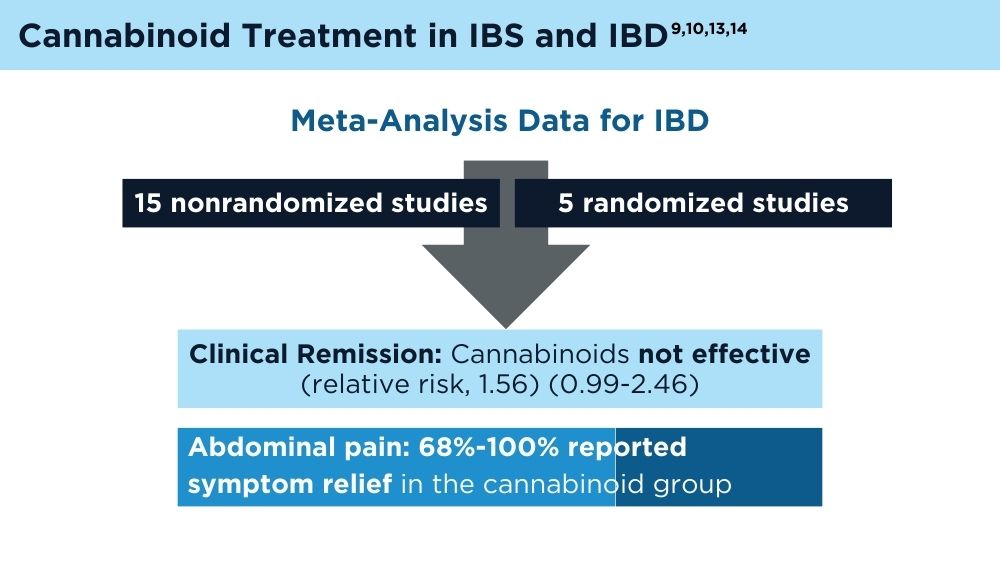

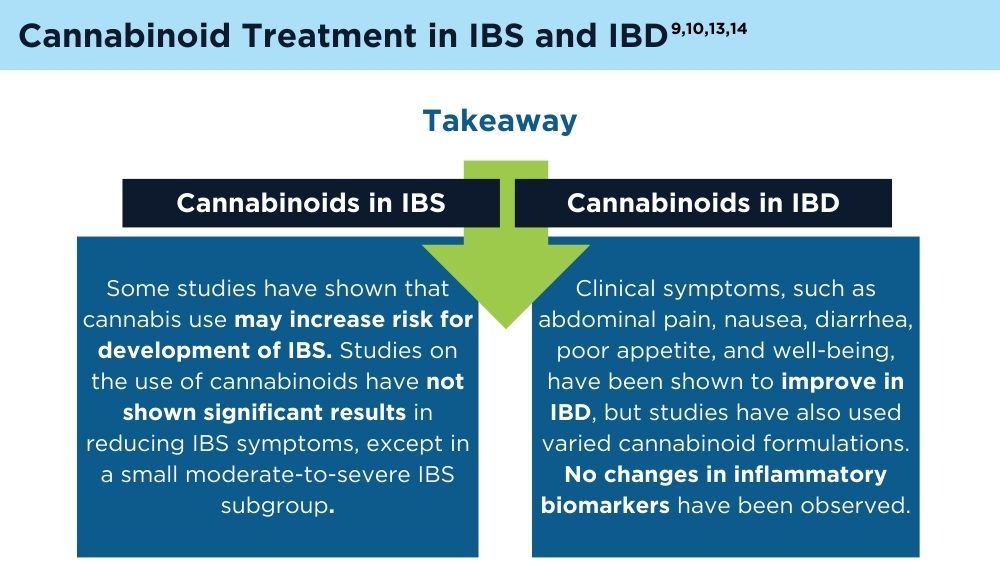

- Doeve BH, van de Meeberg MM, van Schaik FDM, Fidder HH. A systematic review with meta-analysis of the efficacy of cannabis and cannabinoids for inflammatory bowel disease: what can we learn from randomized and nonrandomized studies? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(9):798-809. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001393

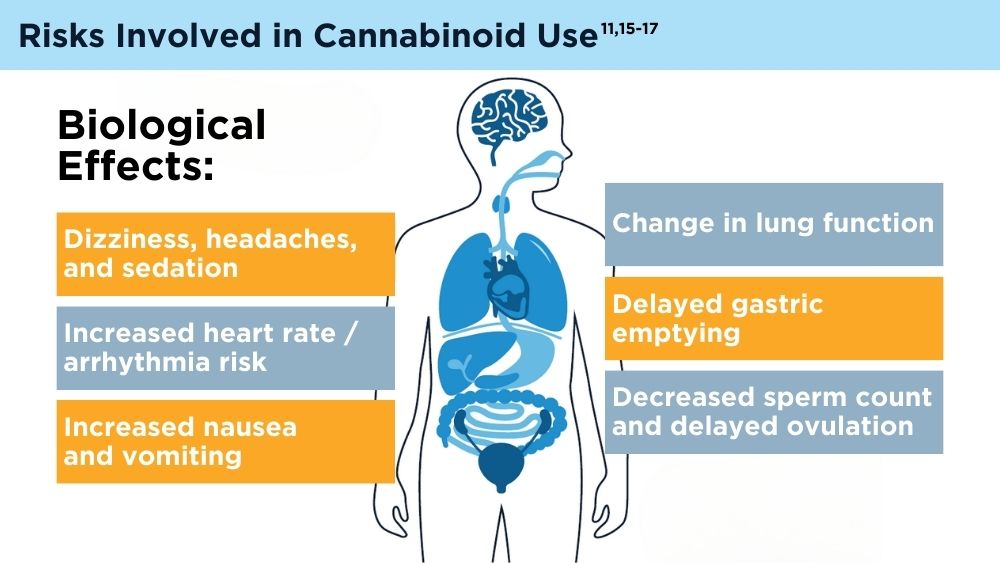

- Gotfried J, Naftali T, Schey R. Role of cannabis and its derivatives in gastrointestinal and hepatic disease [published correction appears in Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1904]. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):62-80. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.087

- Goyal H, Singla U, Gupta U, May E. Role of cannabis in digestive disorders. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(2):135-143. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000779

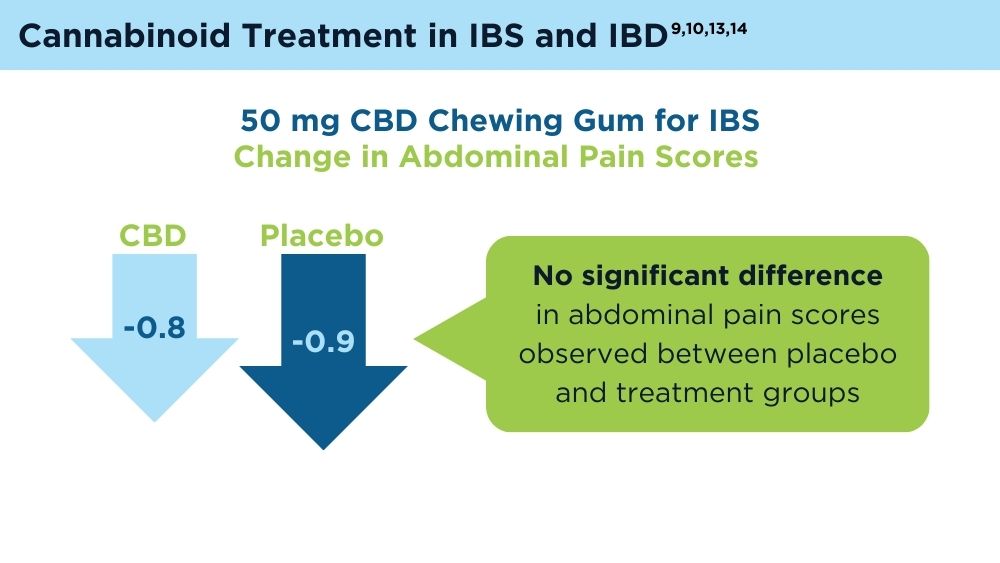

- van Orten-Luiten AB, de Roos NM, Majait S, Witteman BJM, Witkamp RF. Effects of cannabidiol chewing gum on perceived pain and well-being of irritable bowel syndrome patients: a placebo-controlled crossover exploratory intervention study with symptom-driven dosing. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022;7(4):436-444. doi:10.1089/can.2020.0087

- Adejumo AC, Ajayi TO, Adegbala OM, Bukong TN. Higher odds of irritable bowel syndrome among hospitalized patients using cannabis: a propensity matched analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(7):756-765. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000001382

- Antoniou T, Bodkin J, Ho JM. Drug interactions with cannabinoids. CMAJ. 2020;192(9):E206. doi:10.1503/cmaj.191097

- Karila L, Roux P, Rolland B, et al. Acute and long-term effects of cannabis use: a review. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4112-4118. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990620

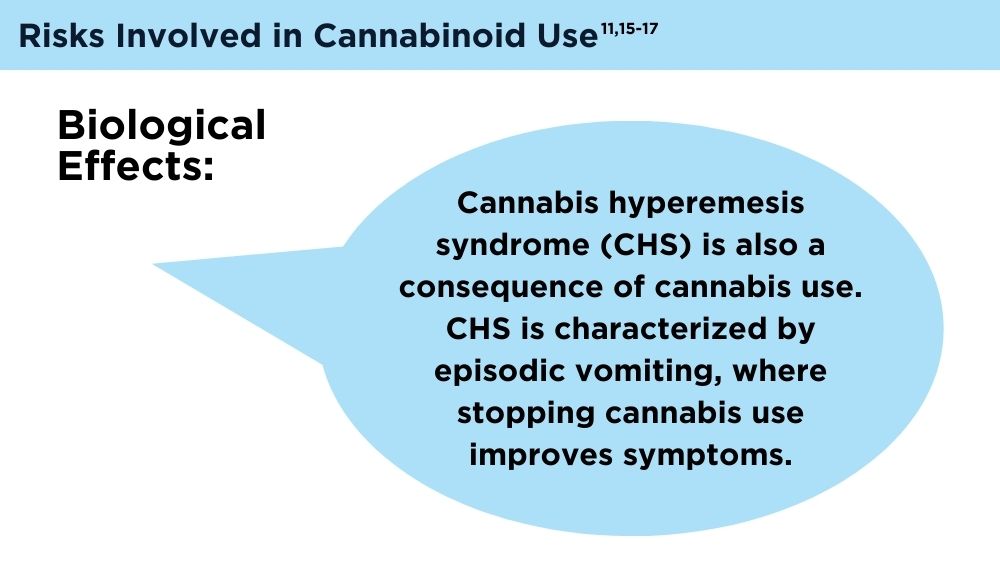

- Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Li BUK, et al. Role of chronic cannabis use: cyclic vomiting syndrome vs cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(suppl 2):e13606. doi:10.1111/nmo.13606

- Leung J, Chan G, Stjepanović D, Chung JYC, Hall W, Hammond D. Prevalence and self-reported reasons of cannabis use for medical purposes in USA and Canada. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239(5):1509-1519. doi:10.1007/s00213-021-06047-8

- Ahmed W, Katz S. Therapeutic use of cannabis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2016;12(11):668-679.

- Ravikoff Allegretti J, Courtwright A, Lucci M, Korzenik JR, Levine J. Marijuana use patterns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(13):2809-2814. doi:10.1097/01.MIB.0000435851.94391.37

- Marijuana legality by state - updated February 1, 2024. DISA. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://disa.com/marijuana-legality-by-state

- The Cannigma Staff. Where is weed legal around the globe? The Cannigma. Updated July 3, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://cannigma.com/regulation/cannabis-regulation-around-the-world/

- Zou S, Kumar U. Cannabinoid receptors and the endocannabinoid system: signaling and function in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):833. doi:10.3390/ijms19030833

- Maselli DB, Camilleri M. Pharmacology, clinical effects, and therapeutic potential of cannabinoids for gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(9):1748-1758.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.020

- Buckley MC, Kumar A, Swaminath A. Inflammatory bowel disease and cannabis: a practical approach for clinicians. Adv Ther. 2021;38(7):4152- 4161. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01805-8

- Chang L, Cash BD, Lembo A, et al. Efficacy and safety of olorinab, a full agonist of the cannabinoid receptor 2, for the treatment of abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a phase 2b randomized placebo-controlled trial (CAPTIVATE). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(5):e14539. doi:10.1111/nmo.14539

- Doeve BH, van de Meeberg MM, van Schaik FDM, Fidder HH. A systematic review with meta-analysis of the efficacy of cannabis and cannabinoids for inflammatory bowel disease: what can we learn from randomized and nonrandomized studies? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(9):798-809. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001393

- Gotfried J, Naftali T, Schey R. Role of cannabis and its derivatives in gastrointestinal and hepatic disease [published correction appears in Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1904]. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):62-80. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.087

- Goyal H, Singla U, Gupta U, May E. Role of cannabis in digestive disorders. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(2):135-143. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000779

- van Orten-Luiten AB, de Roos NM, Majait S, Witteman BJM, Witkamp RF. Effects of cannabidiol chewing gum on perceived pain and well-being of irritable bowel syndrome patients: a placebo-controlled crossover exploratory intervention study with symptom-driven dosing. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022;7(4):436-444. doi:10.1089/can.2020.0087

- Adejumo AC, Ajayi TO, Adegbala OM, Bukong TN. Higher odds of irritable bowel syndrome among hospitalized patients using cannabis: a propensity matched analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(7):756-765. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000001382

- Antoniou T, Bodkin J, Ho JM. Drug interactions with cannabinoids. CMAJ. 2020;192(9):E206. doi:10.1503/cmaj.191097

- Karila L, Roux P, Rolland B, et al. Acute and long-term effects of cannabis use: a review. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4112-4118. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990620

- Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Li BUK, et al. Role of chronic cannabis use: cyclic vomiting syndrome vs cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(suppl 2):e13606. doi:10.1111/nmo.13606

- Leung J, Chan G, Stjepanović D, Chung JYC, Hall W, Hammond D. Prevalence and self-reported reasons of cannabis use for medical purposes in USA and Canada. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239(5):1509-1519. doi:10.1007/s00213-021-06047-8

- Ahmed W, Katz S. Therapeutic use of cannabis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2016;12(11):668-679.

- Ravikoff Allegretti J, Courtwright A, Lucci M, Korzenik JR, Levine J. Marijuana use patterns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(13):2809-2814. doi:10.1097/01.MIB.0000435851.94391.37

- Marijuana legality by state - updated February 1, 2024. DISA. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://disa.com/marijuana-legality-by-state

- The Cannigma Staff. Where is weed legal around the globe? The Cannigma. Updated July 3, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://cannigma.com/regulation/cannabis-regulation-around-the-world/

- Zou S, Kumar U. Cannabinoid receptors and the endocannabinoid system: signaling and function in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):833. doi:10.3390/ijms19030833

- Maselli DB, Camilleri M. Pharmacology, clinical effects, and therapeutic potential of cannabinoids for gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(9):1748-1758.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.020

- Buckley MC, Kumar A, Swaminath A. Inflammatory bowel disease and cannabis: a practical approach for clinicians. Adv Ther. 2021;38(7):4152- 4161. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01805-8

- Chang L, Cash BD, Lembo A, et al. Efficacy and safety of olorinab, a full agonist of the cannabinoid receptor 2, for the treatment of abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a phase 2b randomized placebo-controlled trial (CAPTIVATE). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(5):e14539. doi:10.1111/nmo.14539

- Doeve BH, van de Meeberg MM, van Schaik FDM, Fidder HH. A systematic review with meta-analysis of the efficacy of cannabis and cannabinoids for inflammatory bowel disease: what can we learn from randomized and nonrandomized studies? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(9):798-809. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001393

- Gotfried J, Naftali T, Schey R. Role of cannabis and its derivatives in gastrointestinal and hepatic disease [published correction appears in Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1904]. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):62-80. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.087

- Goyal H, Singla U, Gupta U, May E. Role of cannabis in digestive disorders. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(2):135-143. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000779

- van Orten-Luiten AB, de Roos NM, Majait S, Witteman BJM, Witkamp RF. Effects of cannabidiol chewing gum on perceived pain and well-being of irritable bowel syndrome patients: a placebo-controlled crossover exploratory intervention study with symptom-driven dosing. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022;7(4):436-444. doi:10.1089/can.2020.0087

- Adejumo AC, Ajayi TO, Adegbala OM, Bukong TN. Higher odds of irritable bowel syndrome among hospitalized patients using cannabis: a propensity matched analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(7):756-765. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000001382

- Antoniou T, Bodkin J, Ho JM. Drug interactions with cannabinoids. CMAJ. 2020;192(9):E206. doi:10.1503/cmaj.191097

- Karila L, Roux P, Rolland B, et al. Acute and long-term effects of cannabis use: a review. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4112-4118. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990620

- Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Li BUK, et al. Role of chronic cannabis use: cyclic vomiting syndrome vs cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(suppl 2):e13606. doi:10.1111/nmo.13606

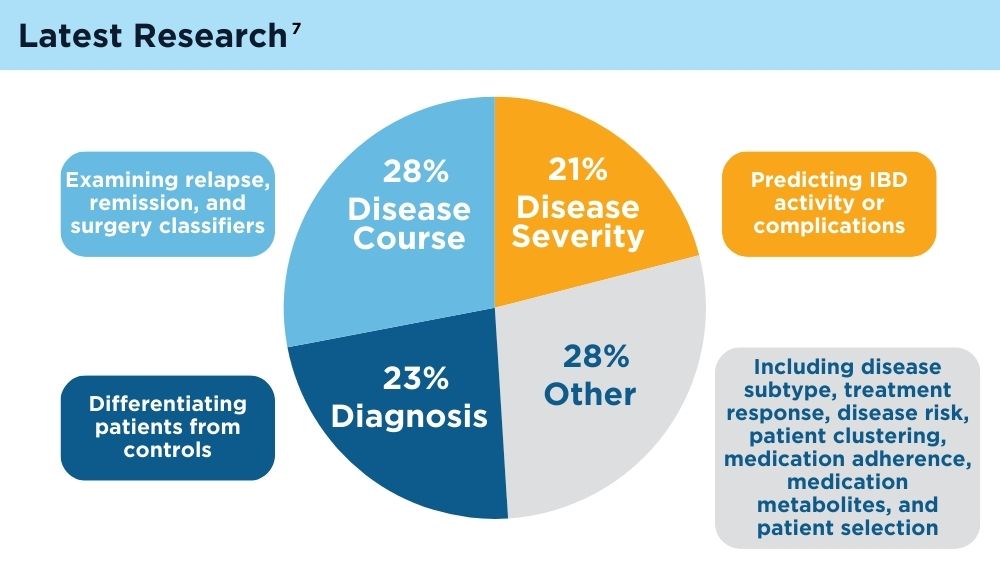

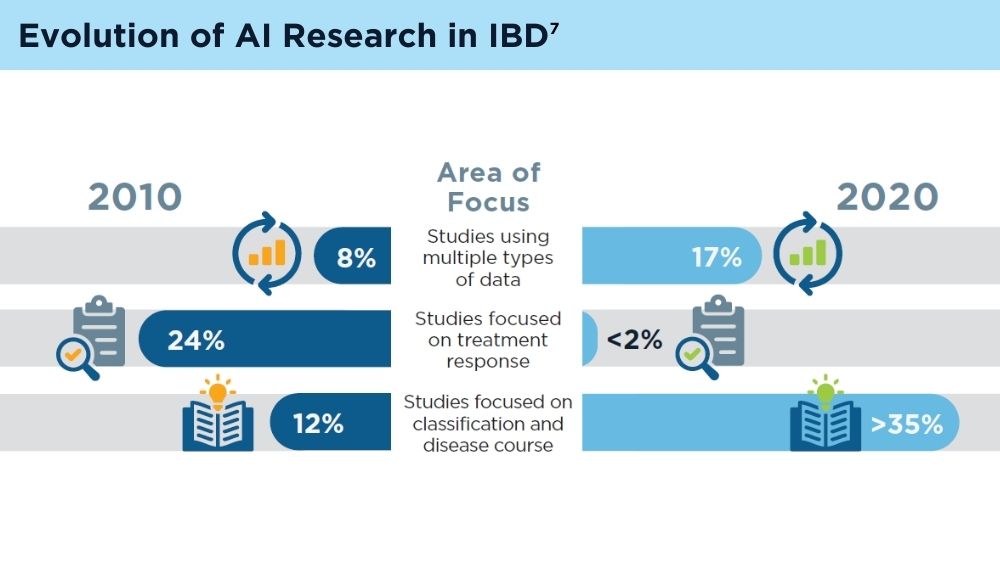

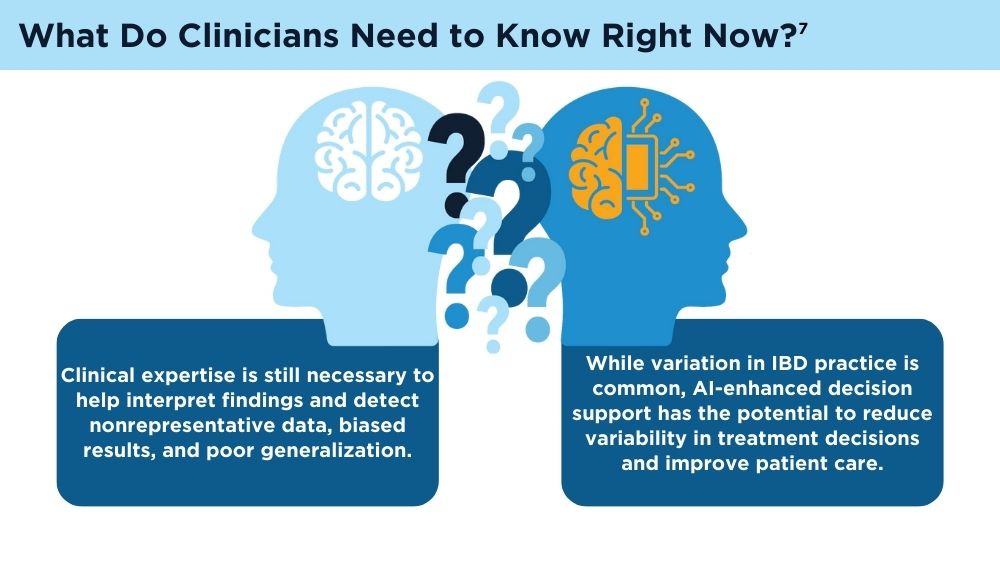

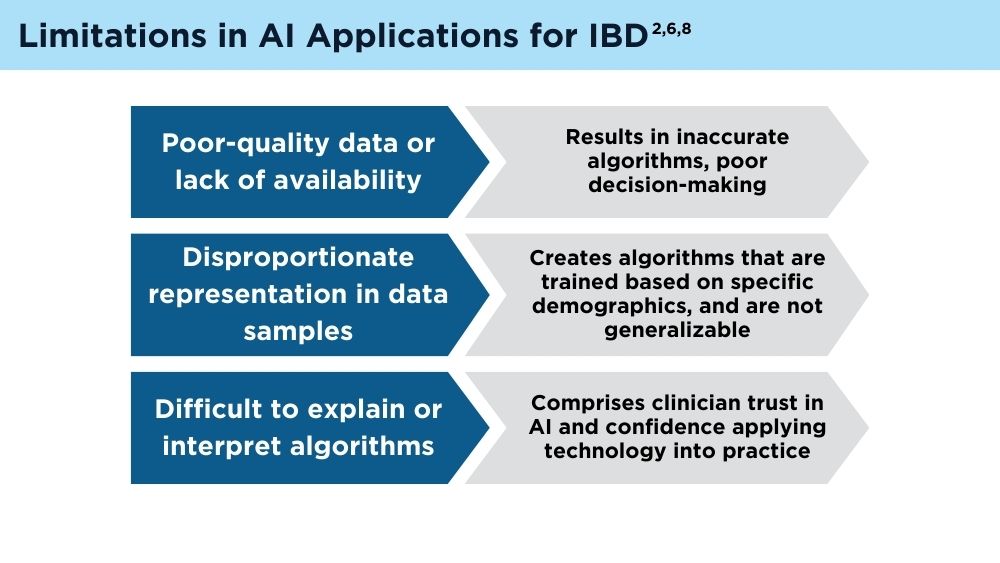

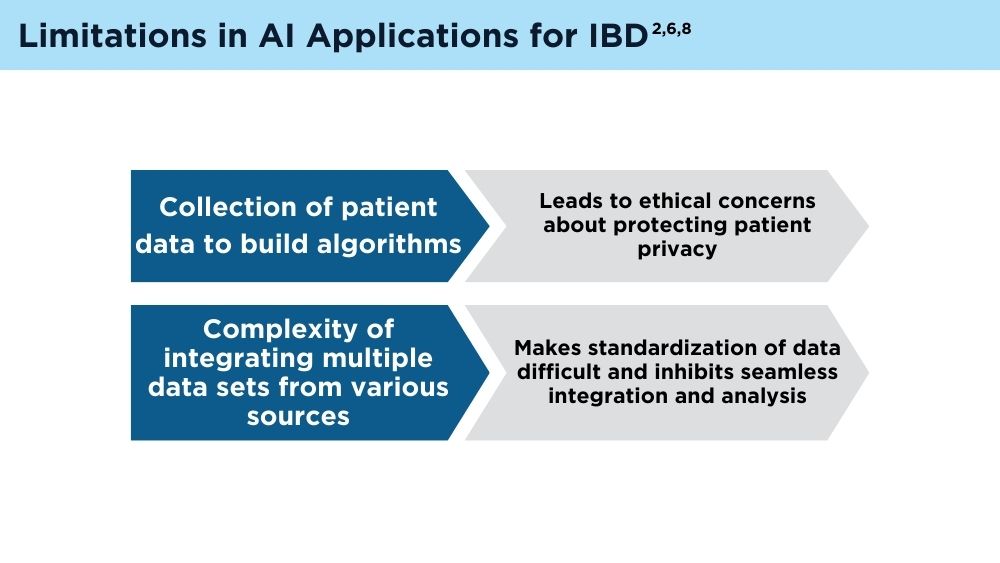

AI and Machine Learning in IBD: Promising Applications and Remaining Challenges

- Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003

- Sharma P. AI shows promise in diagnosis, treatment of IBD, but limitations, concerns remain. Healio. Published June 19, 2023. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.healio.com/news/gastroenterology/20230606/ai-shows-promise-in-diagnosis-treatment-of-ibd-but-limitations-concerns-remain

- Artificial intelligence (AI) vs. machine learning. Columbia Engineering.Accessed January 5, 2024. https://ai.engineering.columbia.edu/ai-vs-machine-learning/

- Zhang B, Shi H, Wang H. Machine learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment selection: a critical approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:1779-1791. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S410301

- Cohen-Mekelburg S, Berry S, Stidham RW, Zhu J, Waljee AK. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning-based methods in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(2):279-285. doi:10.1111/jgh.15405

- Uche-Anya E, Anyane-Yeboa A, Berzin TM, Ghassemi M, May FP. Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology and hepatology: how to advance clinical practice while ensuring health equity. Gut. 2022;71(9):1909-1915. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326271

- Stafford IS, Gosink MM, Mossotto E, Ennis S, Hauben M. A systematic review of artificial intelligence and machine learning applications to inflammatory bowel disease, with practical guidelines for interpretation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(10):1573-1583. doi:10.1093/ibd/izac115

- Gubatan J, Levitte S, Patel A, Balabanis T, Wei MT, Sinha SR. Artificial intelligence applications in inflammatory bowel disease: emerging technologies and future directions. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(17):1920-1935. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i17.1920

- Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003

- Sharma P. AI shows promise in diagnosis, treatment of IBD, but limitations, concerns remain. Healio. Published June 19, 2023. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.healio.com/news/gastroenterology/20230606/ai-shows-promise-in-diagnosis-treatment-of-ibd-but-limitations-concerns-remain

- Artificial intelligence (AI) vs. machine learning. Columbia Engineering.Accessed January 5, 2024. https://ai.engineering.columbia.edu/ai-vs-machine-learning/

- Zhang B, Shi H, Wang H. Machine learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment selection: a critical approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:1779-1791. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S410301

- Cohen-Mekelburg S, Berry S, Stidham RW, Zhu J, Waljee AK. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning-based methods in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(2):279-285. doi:10.1111/jgh.15405

- Uche-Anya E, Anyane-Yeboa A, Berzin TM, Ghassemi M, May FP. Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology and hepatology: how to advance clinical practice while ensuring health equity. Gut. 2022;71(9):1909-1915. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326271

- Stafford IS, Gosink MM, Mossotto E, Ennis S, Hauben M. A systematic review of artificial intelligence and machine learning applications to inflammatory bowel disease, with practical guidelines for interpretation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(10):1573-1583. doi:10.1093/ibd/izac115

- Gubatan J, Levitte S, Patel A, Balabanis T, Wei MT, Sinha SR. Artificial intelligence applications in inflammatory bowel disease: emerging technologies and future directions. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(17):1920-1935. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i17.1920

- Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003

- Sharma P. AI shows promise in diagnosis, treatment of IBD, but limitations, concerns remain. Healio. Published June 19, 2023. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.healio.com/news/gastroenterology/20230606/ai-shows-promise-in-diagnosis-treatment-of-ibd-but-limitations-concerns-remain

- Artificial intelligence (AI) vs. machine learning. Columbia Engineering.Accessed January 5, 2024. https://ai.engineering.columbia.edu/ai-vs-machine-learning/

- Zhang B, Shi H, Wang H. Machine learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment selection: a critical approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:1779-1791. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S410301

- Cohen-Mekelburg S, Berry S, Stidham RW, Zhu J, Waljee AK. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning-based methods in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(2):279-285. doi:10.1111/jgh.15405

- Uche-Anya E, Anyane-Yeboa A, Berzin TM, Ghassemi M, May FP. Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology and hepatology: how to advance clinical practice while ensuring health equity. Gut. 2022;71(9):1909-1915. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326271

- Stafford IS, Gosink MM, Mossotto E, Ennis S, Hauben M. A systematic review of artificial intelligence and machine learning applications to inflammatory bowel disease, with practical guidelines for interpretation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(10):1573-1583. doi:10.1093/ibd/izac115

- Gubatan J, Levitte S, Patel A, Balabanis T, Wei MT, Sinha SR. Artificial intelligence applications in inflammatory bowel disease: emerging technologies and future directions. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(17):1920-1935. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i17.1920

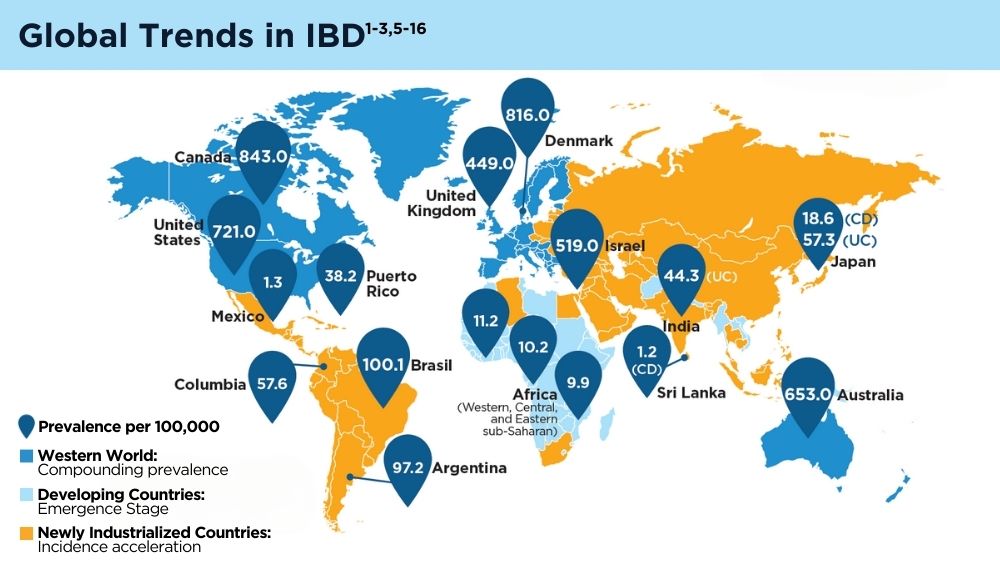

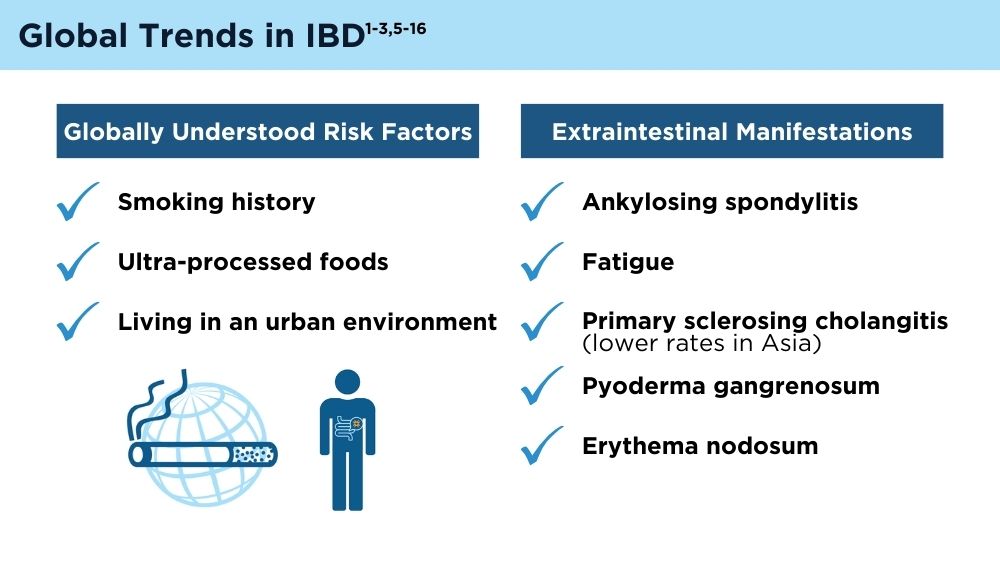

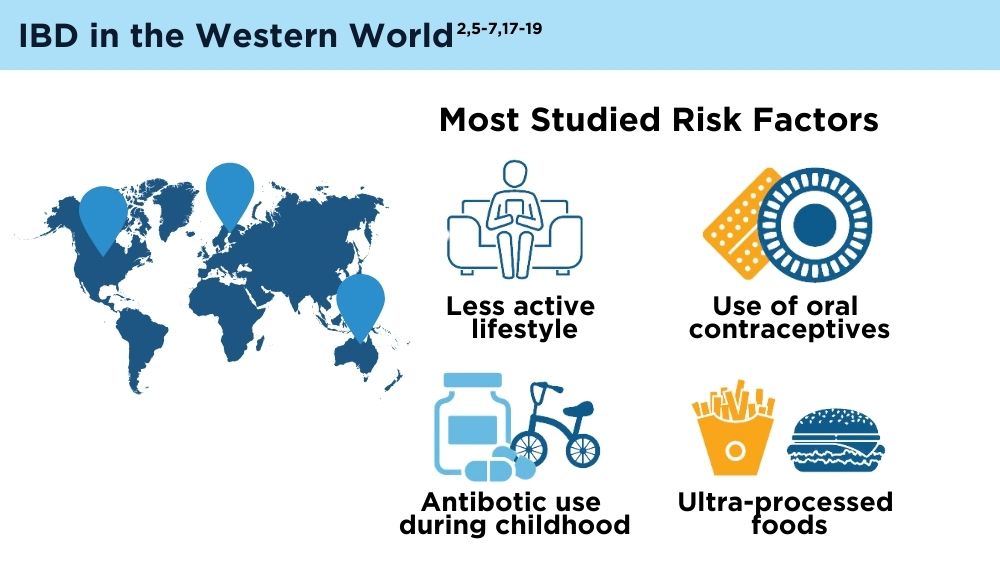

The Changing Face of IBD: Beyond the Western World

- Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):56-66. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x

- Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease [published correction appears in Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):2084]. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):313-321.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020

- Balderramo D, Quaresma AB, Olivera PA, et al. Challenges in diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in Latin America. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024; 9(3):263-272. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00284-4

- Song EM, Na SY, Hong SN, Ng SC, Hisamatsu T, Ye BD. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease–Asian perspectives: the results of a multinational web-based survey in the 8th Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis meeting. Intest Res. 2023;21(3):339-352. doi:10.5217/ir.2022.00135

- GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17-30. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30333-4

- Chen X, Xiang X, Xia W, et al. Evolving trends and burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia, 1990-2019: a comprehensive analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023;13(4):725-739. doi:10.1007/s44197-023-00145-w

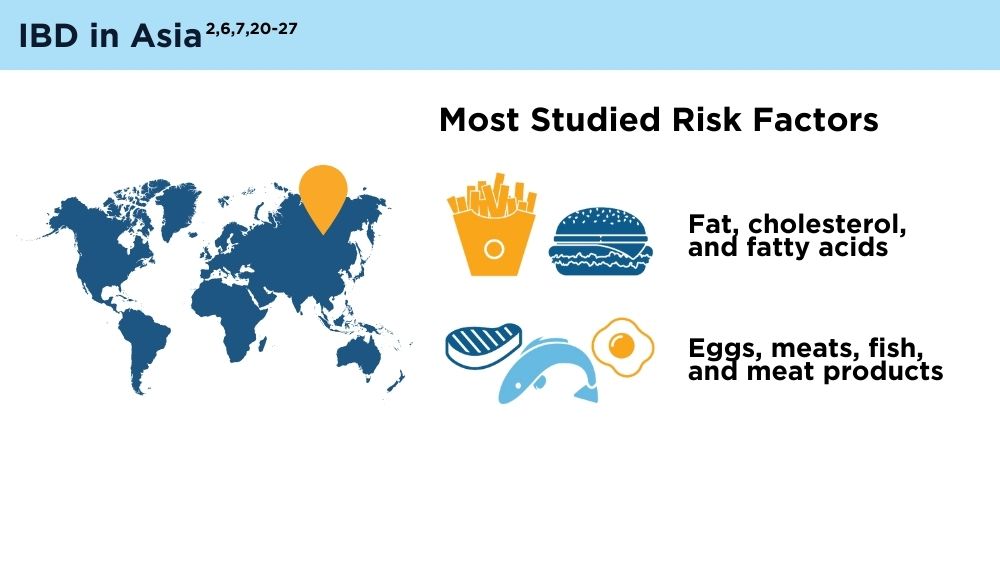

- Zhao M, Feng R, Ben-Horin S, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: environmental and dietary differences of inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern and Western populations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(3):266-276. doi:10.1111/apt.16703

- Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003

- Quaresma AB, Damiao AOMC, Coy CSR, et al. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the public healthcare system in Brazil: a large population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100298. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100298

- Gordon H, Burisch J, Ellul P, et al. ECCO guidelines on extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(1):1-37. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad108

- Coward S, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al; Canadian Gastro-Intestinal Epidemiology Consortium (CanGIEC). Forecasting the Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Canadian Nationwide Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 18. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002687. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38299598.

- Dorn-Rasmussen M, Lo B, Zhao M, Kaplan GG, Malham M, Wewer V, Burisch J. The Incidence and Prevalence of Paediatric- and Adult-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Denmark During a 37-Year Period: A Nationwide Cohort Study (1980-2017). J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(2):259- 268. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac138. PMID: 36125076.

- Watermeyer G, Katsidzira L, Setshedi M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiology, risk factors, and challenges in diagnosis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(10):952-961. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00047-4

- Stulman MY, Asayag N, Focht G, et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Israel: A Nationwide Epi-Israeli IBD Research Nucleus Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(11):1784-1794. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa341

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020;396(10256):e56]. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-2778. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0

- Busingye D, Pollack A, Chidwick K. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Australian general practice population: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0252458. Published 2021 May 27. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0252458

- Gecse KB, Vermeire S. Differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: imitations and complications. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(9):644-653. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30159-6

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): comorbidities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Last reviewed April 14, 2022. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/data-and-statistics/comorbidities.html

- Mosli MH, Alsahafi M, Alsanea MN, Alhasani F, Ahmed M, Saadah O. Multimorbidity among inflammatory bowel disease patients in a tertiary care center: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):487. doi:10.1186/s12876-022-02578-2

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Mayo Clinic. September 3, 2022. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/inflammatory-bowel-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353320

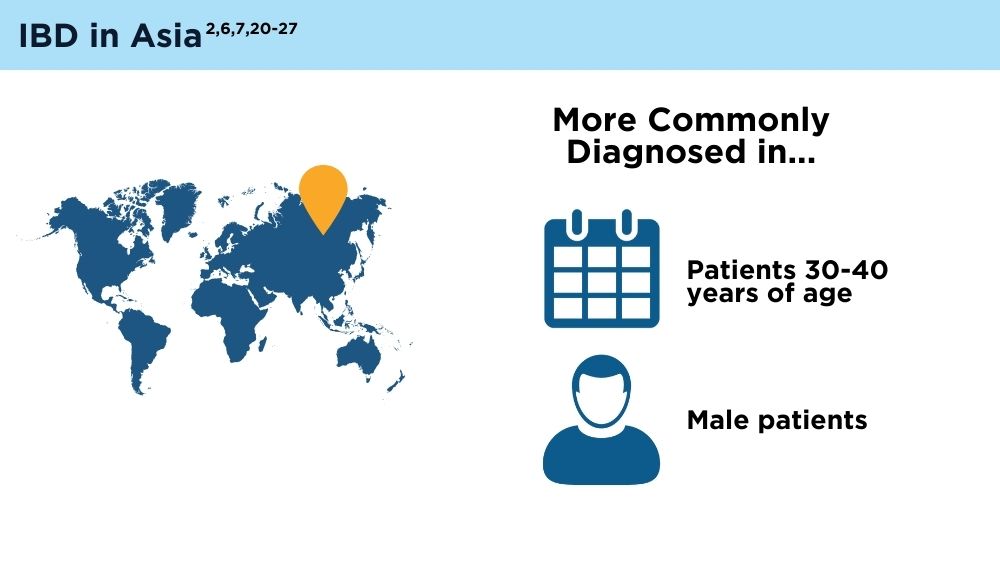

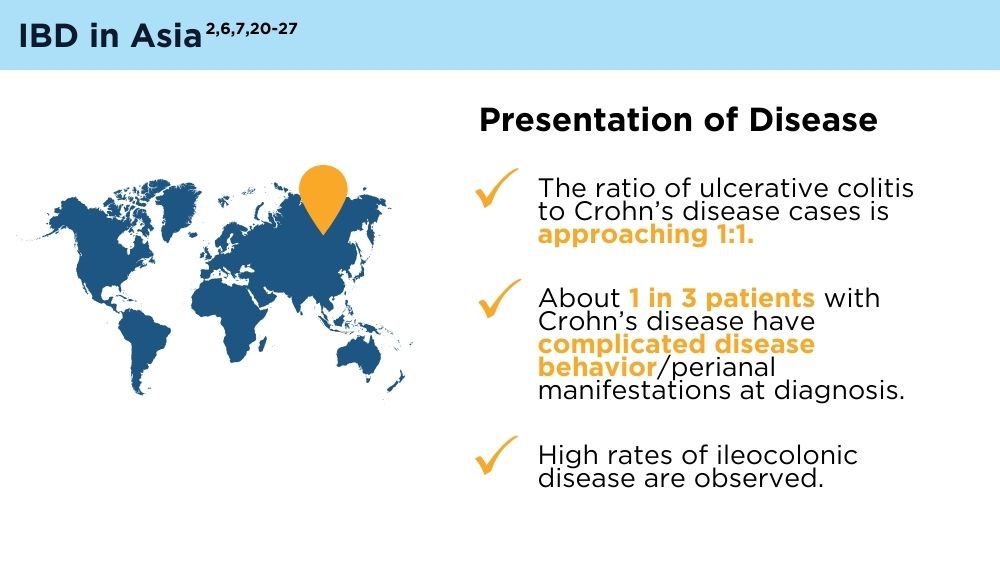

- Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):158-165.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007

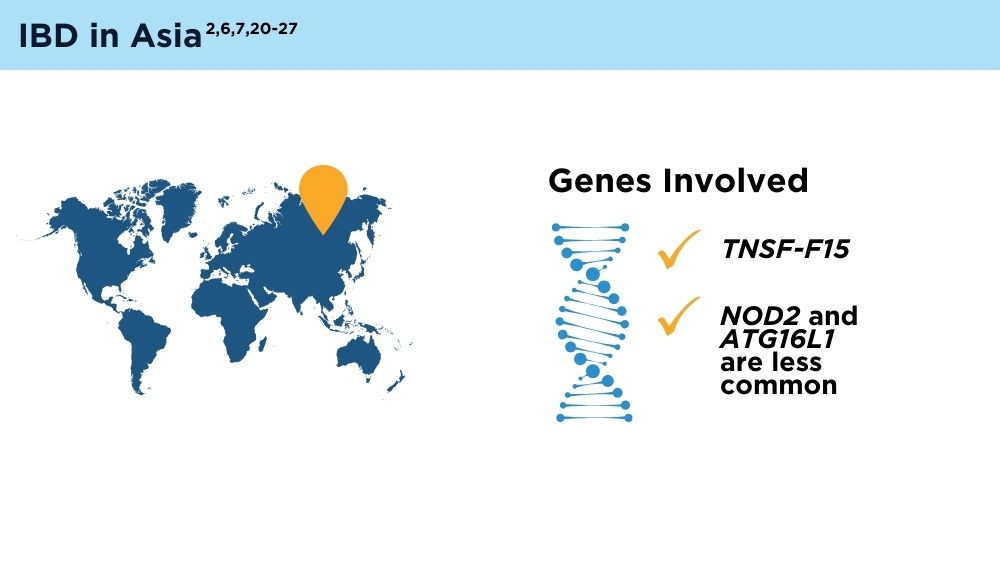

- Ng SC, Tsoi KK, Kamm MA, et al. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(6):1164-1176. doi:10.1002/ibd.21845

- Banerjee R, Pal P, Mak JWY, Ng SC. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease in resource-limited settings in Asia. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(12):1076-1088. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30299-5

- Ng SC, Mak JWY, Pal P, Banerjee R. Optimising management strategies of inflammatory bowel disease in resource-limited settings in Asia. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(12):1089-1100. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30298-3

- Ng SC. Emerging trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2016;12(3):193-196. PMID: 27231449

- Ran Z, Wu K, Matsuoka K, et al. Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis and Asia Pacific Association of Gastroenterology practice recommendations for medical management and monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(3):637-645. doi:10.1111/jgh.15185

- Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):979-986. doi:10.1038/ng.3359

- Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Parra-Holguín NN, Juliao-Baños F, et al; for the EPILATAM study group. Clinical differentiation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Latin America and the Caribbean. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(3):e28624. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000028624

- Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):56-66. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x

- Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease [published correction appears in Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):2084]. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):313-321.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020

- Balderramo D, Quaresma AB, Olivera PA, et al. Challenges in diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in Latin America. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024; 9(3):263-272. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00284-4

- Song EM, Na SY, Hong SN, Ng SC, Hisamatsu T, Ye BD. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease–Asian perspectives: the results of a multinational web-based survey in the 8th Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis meeting. Intest Res. 2023;21(3):339-352. doi:10.5217/ir.2022.00135

- GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17-30. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30333-4

- Chen X, Xiang X, Xia W, et al. Evolving trends and burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia, 1990-2019: a comprehensive analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023;13(4):725-739. doi:10.1007/s44197-023-00145-w

- Zhao M, Feng R, Ben-Horin S, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: environmental and dietary differences of inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern and Western populations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(3):266-276. doi:10.1111/apt.16703

- Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003

- Quaresma AB, Damiao AOMC, Coy CSR, et al. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the public healthcare system in Brazil: a large population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100298. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100298

- Gordon H, Burisch J, Ellul P, et al. ECCO guidelines on extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(1):1-37. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad108

- Coward S, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al; Canadian Gastro-Intestinal Epidemiology Consortium (CanGIEC). Forecasting the Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Canadian Nationwide Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 18. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002687. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38299598.

- Dorn-Rasmussen M, Lo B, Zhao M, Kaplan GG, Malham M, Wewer V, Burisch J. The Incidence and Prevalence of Paediatric- and Adult-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Denmark During a 37-Year Period: A Nationwide Cohort Study (1980-2017). J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(2):259- 268. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac138. PMID: 36125076.

- Watermeyer G, Katsidzira L, Setshedi M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiology, risk factors, and challenges in diagnosis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(10):952-961. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00047-4

- Stulman MY, Asayag N, Focht G, et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Israel: A Nationwide Epi-Israeli IBD Research Nucleus Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(11):1784-1794. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa341

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020;396(10256):e56]. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-2778. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0

- Busingye D, Pollack A, Chidwick K. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Australian general practice population: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0252458. Published 2021 May 27. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0252458

- Gecse KB, Vermeire S. Differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: imitations and complications. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(9):644-653. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30159-6

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): comorbidities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Last reviewed April 14, 2022. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/data-and-statistics/comorbidities.html

- Mosli MH, Alsahafi M, Alsanea MN, Alhasani F, Ahmed M, Saadah O. Multimorbidity among inflammatory bowel disease patients in a tertiary care center: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):487. doi:10.1186/s12876-022-02578-2

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Mayo Clinic. September 3, 2022. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/inflammatory-bowel-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353320

- Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):158-165.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007

- Ng SC, Tsoi KK, Kamm MA, et al. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(6):1164-1176. doi:10.1002/ibd.21845

- Banerjee R, Pal P, Mak JWY, Ng SC. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease in resource-limited settings in Asia. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(12):1076-1088. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30299-5

- Ng SC, Mak JWY, Pal P, Banerjee R. Optimising management strategies of inflammatory bowel disease in resource-limited settings in Asia. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(12):1089-1100. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30298-3

- Ng SC. Emerging trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2016;12(3):193-196. PMID: 27231449

- Ran Z, Wu K, Matsuoka K, et al. Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis and Asia Pacific Association of Gastroenterology practice recommendations for medical management and monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(3):637-645. doi:10.1111/jgh.15185

- Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):979-986. doi:10.1038/ng.3359

- Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Parra-Holguín NN, Juliao-Baños F, et al; for the EPILATAM study group. Clinical differentiation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Latin America and the Caribbean. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(3):e28624. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000028624

- Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):56-66. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x

- Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease [published correction appears in Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):2084]. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):313-321.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020

- Balderramo D, Quaresma AB, Olivera PA, et al. Challenges in diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in Latin America. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024; 9(3):263-272. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00284-4

- Song EM, Na SY, Hong SN, Ng SC, Hisamatsu T, Ye BD. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease–Asian perspectives: the results of a multinational web-based survey in the 8th Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis meeting. Intest Res. 2023;21(3):339-352. doi:10.5217/ir.2022.00135

- GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17-30. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30333-4

- Chen X, Xiang X, Xia W, et al. Evolving trends and burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia, 1990-2019: a comprehensive analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023;13(4):725-739. doi:10.1007/s44197-023-00145-w

- Zhao M, Feng R, Ben-Horin S, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: environmental and dietary differences of inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern and Western populations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(3):266-276. doi:10.1111/apt.16703

- Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003

- Quaresma AB, Damiao AOMC, Coy CSR, et al. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the public healthcare system in Brazil: a large population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100298. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100298

- Gordon H, Burisch J, Ellul P, et al. ECCO guidelines on extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(1):1-37. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad108

- Coward S, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al; Canadian Gastro-Intestinal Epidemiology Consortium (CanGIEC). Forecasting the Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Canadian Nationwide Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 18. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002687. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38299598.

- Dorn-Rasmussen M, Lo B, Zhao M, Kaplan GG, Malham M, Wewer V, Burisch J. The Incidence and Prevalence of Paediatric- and Adult-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Denmark During a 37-Year Period: A Nationwide Cohort Study (1980-2017). J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(2):259- 268. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac138. PMID: 36125076.

- Watermeyer G, Katsidzira L, Setshedi M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiology, risk factors, and challenges in diagnosis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(10):952-961. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00047-4

- Stulman MY, Asayag N, Focht G, et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Israel: A Nationwide Epi-Israeli IBD Research Nucleus Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(11):1784-1794. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa341

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020;396(10256):e56]. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-2778. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0

- Busingye D, Pollack A, Chidwick K. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Australian general practice population: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0252458. Published 2021 May 27. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0252458

- Gecse KB, Vermeire S. Differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: imitations and complications. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(9):644-653. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30159-6

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): comorbidities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Last reviewed April 14, 2022. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/data-and-statistics/comorbidities.html

- Mosli MH, Alsahafi M, Alsanea MN, Alhasani F, Ahmed M, Saadah O. Multimorbidity among inflammatory bowel disease patients in a tertiary care center: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):487. doi:10.1186/s12876-022-02578-2

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Mayo Clinic. September 3, 2022. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/inflammatory-bowel-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353320

- Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):158-165.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007

- Ng SC, Tsoi KK, Kamm MA, et al. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(6):1164-1176. doi:10.1002/ibd.21845

- Banerjee R, Pal P, Mak JWY, Ng SC. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease in resource-limited settings in Asia. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(12):1076-1088. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30299-5

- Ng SC, Mak JWY, Pal P, Banerjee R. Optimising management strategies of inflammatory bowel disease in resource-limited settings in Asia. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(12):1089-1100. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30298-3

- Ng SC. Emerging trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2016;12(3):193-196. PMID: 27231449

- Ran Z, Wu K, Matsuoka K, et al. Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis and Asia Pacific Association of Gastroenterology practice recommendations for medical management and monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(3):637-645. doi:10.1111/jgh.15185

- Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):979-986. doi:10.1038/ng.3359

- Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Parra-Holguín NN, Juliao-Baños F, et al; for the EPILATAM study group. Clinical differentiation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Latin America and the Caribbean. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(3):e28624. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000028624

Spondyloarthritis Screening Study Finds ‘High Burden of Need’ in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease

More than 40% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) screened positive for joint pain symptomatic of spondyloarthritis (SpA), according to a new study.

Of these patients, 75% did not have any history of arthritis.

“What we know is that a substantial proportion of patients with IBD do report musculoskeletal symptoms, and inflammatory back pain stands out as being one of the more frequent symptoms reported,” said Reem Jan, MBBS, a rheumatologist at the University of Chicago Medicine. She presented the study findings during the annual meeting of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN) in Cleveland.

“Yet a minority of these patients are evaluated by rheumatologists. So that suggests there’s a high burden of need in the IBD population to have this joint pain evaluated and addressed,” she said during her presentation.

She presented preliminary data from an ongoing project to better understand the prevalence of inflammatory arthritis in IBD — estimates range from 17% to 39%— and the risk factors for developing arthritis in this patient population.

Study Details

Researchers enrolled patients from outpatient gastroenterology clinics or procedure units at NYU Langone Health, New York City; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; University of Chicago Medicine Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Chicago; and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City. Additional patients were recruited from Mercy Health, a community health system in Ohio.

Upon entry into the study, participants completed a survey documenting their history with joint pain. The survey combined questions from the DETAIL and the IBIS questionnaires.