User login

Study Questions Relationship Between Crohn’s Strictures and Cancer Risk

, according to investigators.

Although 8% of patients with strictures in a multicenter study were diagnosed with CRC, this diagnosis was made either simultaneously or within 1 year of stricture diagnosis, suggesting that cancer may have driven stricture development, and not the other way around, lead author Thomas Hunaut, MD, of Université de Champagne-Ardenne, Reims, France, and colleagues reported.

“The occurrence of colonic stricture in CD always raises concerns about the risk for dysplasia/cancer,” the investigators wrote in Gastro Hep Advances, noting that no consensus approach is currently available to guide stricture management. “Few studies with conflicting results have evaluated the frequency of CRC associated with colonic stricture in CD, and the natural history of colonic stricture in CD is poorly known.”The present retrospective study included 88 consecutive CD patients with 96 colorectal strictures who were managed at three French referral centers between 1993 and 2022.

Strictures were symptomatic in 62.5% of cases, not passable by scope in 61.4% of cases, and ulcerated in 70.5% of cases. Colonic resection was needed in 47.7% of patients, while endoscopic balloon dilation was performed in 13.6% of patients.

After a median follow-up of 21.5 months, seven patients (8%) were diagnosed with malignant stricture, including five cases of colonic adenocarcinoma, one case of neuroendocrine carcinoma, and one case of B-cell lymphoproliferative neoplasia.

Malignant strictures were more common among older patients with longer disease duration and frequent obstructive symptoms; however, these factors were not supported by multivariate analyses, likely due to sample size, according to the investigators.

Instead, Dr. Hunaut and colleagues highlighted the timing of the diagnoses. In four out of seven patients with malignant stricture, both stricture and cancer were diagnosed at the same time. In the remaining three patients, cancer was diagnosed at 3 months, 8 months, and 12 months after stricture diagnosis. No cases of cancer were diagnosed later than 1 year after the stricture diagnosis.

“We believe that this result is important for the management of colonic strictures complicating CD in clinical practice,” Dr. Hunaut and colleagues wrote.

The simultaneity or proximity of the diagnoses suggests that the “strictures observed are already a neoplastic complication of the colonic inflammatory disease,” they explained.

In other words, common concerns about strictures causing cancer at the same site could be unfounded.

This conclusion echoes a recent administrative database study that reported no independent association between colorectal stricture and CRC, the investigators noted.

“Given the recent evidence on the risk of cancer associated with colonic strictures in CD, systematic colectomy is probably no longer justified,” they wrote. “Factors such as a long disease duration, primary sclerosing cholangitis, a history of dysplasia, and nonpassable and/or symptomatic stricture despite endoscopic dilation tend to argue in favor of surgery — especially if limited resection is possible.”

In contrast, patients with strictures who have low risk of CRC may be better served by a conservative approach, including endoscopy and systematic biopsies, followed by close endoscopic surveillance, according to the investigators. If the stricture is impassable, they recommended endoscopic balloon dilation, followed by intensification of medical therapy if ulceration is observed.

The investigators disclosed relationships with MSD, Ferring, Biogen, and others.

, according to investigators.

Although 8% of patients with strictures in a multicenter study were diagnosed with CRC, this diagnosis was made either simultaneously or within 1 year of stricture diagnosis, suggesting that cancer may have driven stricture development, and not the other way around, lead author Thomas Hunaut, MD, of Université de Champagne-Ardenne, Reims, France, and colleagues reported.

“The occurrence of colonic stricture in CD always raises concerns about the risk for dysplasia/cancer,” the investigators wrote in Gastro Hep Advances, noting that no consensus approach is currently available to guide stricture management. “Few studies with conflicting results have evaluated the frequency of CRC associated with colonic stricture in CD, and the natural history of colonic stricture in CD is poorly known.”The present retrospective study included 88 consecutive CD patients with 96 colorectal strictures who were managed at three French referral centers between 1993 and 2022.

Strictures were symptomatic in 62.5% of cases, not passable by scope in 61.4% of cases, and ulcerated in 70.5% of cases. Colonic resection was needed in 47.7% of patients, while endoscopic balloon dilation was performed in 13.6% of patients.

After a median follow-up of 21.5 months, seven patients (8%) were diagnosed with malignant stricture, including five cases of colonic adenocarcinoma, one case of neuroendocrine carcinoma, and one case of B-cell lymphoproliferative neoplasia.

Malignant strictures were more common among older patients with longer disease duration and frequent obstructive symptoms; however, these factors were not supported by multivariate analyses, likely due to sample size, according to the investigators.

Instead, Dr. Hunaut and colleagues highlighted the timing of the diagnoses. In four out of seven patients with malignant stricture, both stricture and cancer were diagnosed at the same time. In the remaining three patients, cancer was diagnosed at 3 months, 8 months, and 12 months after stricture diagnosis. No cases of cancer were diagnosed later than 1 year after the stricture diagnosis.

“We believe that this result is important for the management of colonic strictures complicating CD in clinical practice,” Dr. Hunaut and colleagues wrote.

The simultaneity or proximity of the diagnoses suggests that the “strictures observed are already a neoplastic complication of the colonic inflammatory disease,” they explained.

In other words, common concerns about strictures causing cancer at the same site could be unfounded.

This conclusion echoes a recent administrative database study that reported no independent association between colorectal stricture and CRC, the investigators noted.

“Given the recent evidence on the risk of cancer associated with colonic strictures in CD, systematic colectomy is probably no longer justified,” they wrote. “Factors such as a long disease duration, primary sclerosing cholangitis, a history of dysplasia, and nonpassable and/or symptomatic stricture despite endoscopic dilation tend to argue in favor of surgery — especially if limited resection is possible.”

In contrast, patients with strictures who have low risk of CRC may be better served by a conservative approach, including endoscopy and systematic biopsies, followed by close endoscopic surveillance, according to the investigators. If the stricture is impassable, they recommended endoscopic balloon dilation, followed by intensification of medical therapy if ulceration is observed.

The investigators disclosed relationships with MSD, Ferring, Biogen, and others.

, according to investigators.

Although 8% of patients with strictures in a multicenter study were diagnosed with CRC, this diagnosis was made either simultaneously or within 1 year of stricture diagnosis, suggesting that cancer may have driven stricture development, and not the other way around, lead author Thomas Hunaut, MD, of Université de Champagne-Ardenne, Reims, France, and colleagues reported.

“The occurrence of colonic stricture in CD always raises concerns about the risk for dysplasia/cancer,” the investigators wrote in Gastro Hep Advances, noting that no consensus approach is currently available to guide stricture management. “Few studies with conflicting results have evaluated the frequency of CRC associated with colonic stricture in CD, and the natural history of colonic stricture in CD is poorly known.”The present retrospective study included 88 consecutive CD patients with 96 colorectal strictures who were managed at three French referral centers between 1993 and 2022.

Strictures were symptomatic in 62.5% of cases, not passable by scope in 61.4% of cases, and ulcerated in 70.5% of cases. Colonic resection was needed in 47.7% of patients, while endoscopic balloon dilation was performed in 13.6% of patients.

After a median follow-up of 21.5 months, seven patients (8%) were diagnosed with malignant stricture, including five cases of colonic adenocarcinoma, one case of neuroendocrine carcinoma, and one case of B-cell lymphoproliferative neoplasia.

Malignant strictures were more common among older patients with longer disease duration and frequent obstructive symptoms; however, these factors were not supported by multivariate analyses, likely due to sample size, according to the investigators.

Instead, Dr. Hunaut and colleagues highlighted the timing of the diagnoses. In four out of seven patients with malignant stricture, both stricture and cancer were diagnosed at the same time. In the remaining three patients, cancer was diagnosed at 3 months, 8 months, and 12 months after stricture diagnosis. No cases of cancer were diagnosed later than 1 year after the stricture diagnosis.

“We believe that this result is important for the management of colonic strictures complicating CD in clinical practice,” Dr. Hunaut and colleagues wrote.

The simultaneity or proximity of the diagnoses suggests that the “strictures observed are already a neoplastic complication of the colonic inflammatory disease,” they explained.

In other words, common concerns about strictures causing cancer at the same site could be unfounded.

This conclusion echoes a recent administrative database study that reported no independent association between colorectal stricture and CRC, the investigators noted.

“Given the recent evidence on the risk of cancer associated with colonic strictures in CD, systematic colectomy is probably no longer justified,” they wrote. “Factors such as a long disease duration, primary sclerosing cholangitis, a history of dysplasia, and nonpassable and/or symptomatic stricture despite endoscopic dilation tend to argue in favor of surgery — especially if limited resection is possible.”

In contrast, patients with strictures who have low risk of CRC may be better served by a conservative approach, including endoscopy and systematic biopsies, followed by close endoscopic surveillance, according to the investigators. If the stricture is impassable, they recommended endoscopic balloon dilation, followed by intensification of medical therapy if ulceration is observed.

The investigators disclosed relationships with MSD, Ferring, Biogen, and others.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Subcutaneous Infliximab Beats Placebo for IBD Maintenance Therapy

These two randomized trials should increase confidence in SC infliximab as a convenient alternative to intravenous delivery, reported co–lead authors Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, AGAF, of Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, and Bruce E. Sands, MD, AGAF, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and colleagues.

Specifically, the trials evaluated CT-P13, an infliximab biosimilar, which was Food and Drug Administration approved for intravenous (IV) use in 2016. The SC formulation was approved in the United States in 2023 as a new drug, requiring phase 3 efficacy confirmatory trials.

“Physicians and patients may prefer SC to IV treatment for IBD, owing to the convenience and flexibility of at-home self-administration, a different exposure profile with high steady-state levels, reduced exposure to nosocomial infection, and health care system resource benefits,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

One trial included patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), while the other enrolled patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Eligibility depended upon inadequate responses or intolerance to corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

All participants began by receiving open-label IV CT-P13, at a dosage of 5 mg/kg, at weeks 0, 2, and 6. At week 10, those who responded to the IV induction therapy were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to continue with either the SC formulation of CT-P13 (120 mg) or switch to placebo, administered every 2 weeks until week 54.

The CD study randomized 343 patients, while the UC study had a larger cohort, with 438 randomized. Median age of participants was in the mid-30s to late 30s, with a majority being White and male. Baseline disease severity, assessed by the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) for CD and the modified Mayo score for UC, was similar across treatment groups.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical remission at week 54, defined as a CDAI score of less than 150 for CD and a modified Mayo score of 0-1 for UC.

In the CD study, 62.3% of patients receiving CT-P13 SC achieved clinical remission, compared with 32.1% in the placebo group, with a treatment difference of 32.1% (95% CI, 20.9-42.1; P < .0001). In addition, 51.1% of CT-P13 SC-treated patients achieved endoscopic response, compared with 17.9% in the placebo group, yielding a treatment difference of 34.6% (95% CI, 24.1-43.5; P < .0001).

In the UC study, 43.2% of patients on CT-P13 SC achieved clinical remission at week 54, compared with 20.8% of those on placebo, with a treatment difference of 21.1% (95% CI, 11.8-29.3; P < .0001). Key secondary endpoints, including endoscopic-histologic mucosal improvement, also favored CT-P13 SC over placebo with statistically significant differences.

The safety profile of CT-P13 SC was comparable with that of IV infliximab, with no new safety concerns emerging during the trials.

“Our results demonstrate the superior efficacy of CT-P13 SC over placebo for maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active CD or UC after induction with CT-P13 IV,” the investigators wrote. “Importantly, the findings confirm that CT-P13 SC is well tolerated in this population, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety profile, compared with placebo. Overall, the results support CT-P13 SC as a treatment option for maintenance therapy in patients with IBD.”

The LIBERTY studies were funded by Celltrion. The investigators disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Gilead, Takeda, and others.

Intravenous (IV) infliximab-dyyb, also called CT-P13 in clinical trials, is a biosimilar that was approved in the United States in 2016 under the brand name Inflectra. It received approval in Europe and elsewhere under the brand name Remsima.

The study from Hanauer and colleagues represents a milestone in biosimilar development as the authors studied an injectable form of the approved IV biosimilar, infliximab-dyyb. How might efficacy compare amongst the two formulations? The LIBERTY studies did not include an active IV infliximab comparator to answer this question. Based on a phase 1, open label trial, subcutaneous (SC) infliximab appears noninferior to IV infliximab.

It is remarkable that we have progressed from creating highly similar copies of older biologics whose patents have expired, to reimagining and modifying biosimilars to potentially improve on efficacy, dosing, tolerability, or as in the case of SC infliximab-dyyb, providing a new mode of delivery. For SC infliximab, whether the innovator designation will cause different patterns of use based on cost or other factors, compared with places where the injectable and intravenous formulations are both considered biosimilars, remains to be seen.

Fernando S. Velayos, MD, MPH, AGAF, is director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program, The Permanente Group Northern California; adjunct investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; and chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Intravenous (IV) infliximab-dyyb, also called CT-P13 in clinical trials, is a biosimilar that was approved in the United States in 2016 under the brand name Inflectra. It received approval in Europe and elsewhere under the brand name Remsima.

The study from Hanauer and colleagues represents a milestone in biosimilar development as the authors studied an injectable form of the approved IV biosimilar, infliximab-dyyb. How might efficacy compare amongst the two formulations? The LIBERTY studies did not include an active IV infliximab comparator to answer this question. Based on a phase 1, open label trial, subcutaneous (SC) infliximab appears noninferior to IV infliximab.

It is remarkable that we have progressed from creating highly similar copies of older biologics whose patents have expired, to reimagining and modifying biosimilars to potentially improve on efficacy, dosing, tolerability, or as in the case of SC infliximab-dyyb, providing a new mode of delivery. For SC infliximab, whether the innovator designation will cause different patterns of use based on cost or other factors, compared with places where the injectable and intravenous formulations are both considered biosimilars, remains to be seen.

Fernando S. Velayos, MD, MPH, AGAF, is director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program, The Permanente Group Northern California; adjunct investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; and chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Intravenous (IV) infliximab-dyyb, also called CT-P13 in clinical trials, is a biosimilar that was approved in the United States in 2016 under the brand name Inflectra. It received approval in Europe and elsewhere under the brand name Remsima.

The study from Hanauer and colleagues represents a milestone in biosimilar development as the authors studied an injectable form of the approved IV biosimilar, infliximab-dyyb. How might efficacy compare amongst the two formulations? The LIBERTY studies did not include an active IV infliximab comparator to answer this question. Based on a phase 1, open label trial, subcutaneous (SC) infliximab appears noninferior to IV infliximab.

It is remarkable that we have progressed from creating highly similar copies of older biologics whose patents have expired, to reimagining and modifying biosimilars to potentially improve on efficacy, dosing, tolerability, or as in the case of SC infliximab-dyyb, providing a new mode of delivery. For SC infliximab, whether the innovator designation will cause different patterns of use based on cost or other factors, compared with places where the injectable and intravenous formulations are both considered biosimilars, remains to be seen.

Fernando S. Velayos, MD, MPH, AGAF, is director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program, The Permanente Group Northern California; adjunct investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; and chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center. He reported no conflicts of interest.

These two randomized trials should increase confidence in SC infliximab as a convenient alternative to intravenous delivery, reported co–lead authors Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, AGAF, of Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, and Bruce E. Sands, MD, AGAF, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and colleagues.

Specifically, the trials evaluated CT-P13, an infliximab biosimilar, which was Food and Drug Administration approved for intravenous (IV) use in 2016. The SC formulation was approved in the United States in 2023 as a new drug, requiring phase 3 efficacy confirmatory trials.

“Physicians and patients may prefer SC to IV treatment for IBD, owing to the convenience and flexibility of at-home self-administration, a different exposure profile with high steady-state levels, reduced exposure to nosocomial infection, and health care system resource benefits,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

One trial included patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), while the other enrolled patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Eligibility depended upon inadequate responses or intolerance to corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

All participants began by receiving open-label IV CT-P13, at a dosage of 5 mg/kg, at weeks 0, 2, and 6. At week 10, those who responded to the IV induction therapy were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to continue with either the SC formulation of CT-P13 (120 mg) or switch to placebo, administered every 2 weeks until week 54.

The CD study randomized 343 patients, while the UC study had a larger cohort, with 438 randomized. Median age of participants was in the mid-30s to late 30s, with a majority being White and male. Baseline disease severity, assessed by the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) for CD and the modified Mayo score for UC, was similar across treatment groups.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical remission at week 54, defined as a CDAI score of less than 150 for CD and a modified Mayo score of 0-1 for UC.

In the CD study, 62.3% of patients receiving CT-P13 SC achieved clinical remission, compared with 32.1% in the placebo group, with a treatment difference of 32.1% (95% CI, 20.9-42.1; P < .0001). In addition, 51.1% of CT-P13 SC-treated patients achieved endoscopic response, compared with 17.9% in the placebo group, yielding a treatment difference of 34.6% (95% CI, 24.1-43.5; P < .0001).

In the UC study, 43.2% of patients on CT-P13 SC achieved clinical remission at week 54, compared with 20.8% of those on placebo, with a treatment difference of 21.1% (95% CI, 11.8-29.3; P < .0001). Key secondary endpoints, including endoscopic-histologic mucosal improvement, also favored CT-P13 SC over placebo with statistically significant differences.

The safety profile of CT-P13 SC was comparable with that of IV infliximab, with no new safety concerns emerging during the trials.

“Our results demonstrate the superior efficacy of CT-P13 SC over placebo for maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active CD or UC after induction with CT-P13 IV,” the investigators wrote. “Importantly, the findings confirm that CT-P13 SC is well tolerated in this population, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety profile, compared with placebo. Overall, the results support CT-P13 SC as a treatment option for maintenance therapy in patients with IBD.”

The LIBERTY studies were funded by Celltrion. The investigators disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Gilead, Takeda, and others.

These two randomized trials should increase confidence in SC infliximab as a convenient alternative to intravenous delivery, reported co–lead authors Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, AGAF, of Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, and Bruce E. Sands, MD, AGAF, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and colleagues.

Specifically, the trials evaluated CT-P13, an infliximab biosimilar, which was Food and Drug Administration approved for intravenous (IV) use in 2016. The SC formulation was approved in the United States in 2023 as a new drug, requiring phase 3 efficacy confirmatory trials.

“Physicians and patients may prefer SC to IV treatment for IBD, owing to the convenience and flexibility of at-home self-administration, a different exposure profile with high steady-state levels, reduced exposure to nosocomial infection, and health care system resource benefits,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

One trial included patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), while the other enrolled patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Eligibility depended upon inadequate responses or intolerance to corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

All participants began by receiving open-label IV CT-P13, at a dosage of 5 mg/kg, at weeks 0, 2, and 6. At week 10, those who responded to the IV induction therapy were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to continue with either the SC formulation of CT-P13 (120 mg) or switch to placebo, administered every 2 weeks until week 54.

The CD study randomized 343 patients, while the UC study had a larger cohort, with 438 randomized. Median age of participants was in the mid-30s to late 30s, with a majority being White and male. Baseline disease severity, assessed by the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) for CD and the modified Mayo score for UC, was similar across treatment groups.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical remission at week 54, defined as a CDAI score of less than 150 for CD and a modified Mayo score of 0-1 for UC.

In the CD study, 62.3% of patients receiving CT-P13 SC achieved clinical remission, compared with 32.1% in the placebo group, with a treatment difference of 32.1% (95% CI, 20.9-42.1; P < .0001). In addition, 51.1% of CT-P13 SC-treated patients achieved endoscopic response, compared with 17.9% in the placebo group, yielding a treatment difference of 34.6% (95% CI, 24.1-43.5; P < .0001).

In the UC study, 43.2% of patients on CT-P13 SC achieved clinical remission at week 54, compared with 20.8% of those on placebo, with a treatment difference of 21.1% (95% CI, 11.8-29.3; P < .0001). Key secondary endpoints, including endoscopic-histologic mucosal improvement, also favored CT-P13 SC over placebo with statistically significant differences.

The safety profile of CT-P13 SC was comparable with that of IV infliximab, with no new safety concerns emerging during the trials.

“Our results demonstrate the superior efficacy of CT-P13 SC over placebo for maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active CD or UC after induction with CT-P13 IV,” the investigators wrote. “Importantly, the findings confirm that CT-P13 SC is well tolerated in this population, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety profile, compared with placebo. Overall, the results support CT-P13 SC as a treatment option for maintenance therapy in patients with IBD.”

The LIBERTY studies were funded by Celltrion. The investigators disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Gilead, Takeda, and others.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

New Associations Identified Between IBD and Extraintestinal Manifestations

, according to a recent study.

For instance, antinuclear cytoplastic antibody is associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in Crohn’s disease, and CPEB4 genetic variation is associated with skin manifestations.

“Up to 40% of people with IBD suffer with symptoms from inflammation that occurs outside the gut, particularly affecting the liver, skin, and joints. These symptoms can often have a bigger impact on quality of life than the gut inflammation itself and can actually be life-threatening,” said senior author Dermot McGovern, MD, PhD, AGAF, director of translational medicine at the F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Immunobiology Research Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“With the advances in therapies for IBD, including availability of gut-selective agents, treatment choices often incorporate whether a patient has one of these manifestations or not,” he said. “We need to understand who is at increased risk of these and why.”

The study was published in Gastroenterology .

Analyzing Associations

Dr. McGovern and colleagues analyzed data for 12,083 unrelated European ancestry IBD cases with presence or absence of EIMs across four cohorts in the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center IBD Research Repository, National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases IBD Genetics Consortium, Sinai Helmsley Alliance for Research Excellence Consortium, and Risk Stratification and Identification of Immunogenetic and Microbial Markers of Rapid Disease Progression in Children with Crohn’s Disease.

In particular, the researchers looked at EIM phenotypes such as ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis, PSC, peripheral arthritis, and skin and ocular manifestations. They analyzed clinical and serologic parameters through regression analyses using a mixed-effects model, as well as within-case logistic regression for genetic associations.

Overall, 14% of patients had at least one EIM. Contrary to previous reports, only 2% had multiple EIMs, and most co-occurrences were negatively correlated. Nearly all EIMs were more common in Crohn’s disease, except for PSC, which was more common in ulcerative colitis.

In general, EIMs occurred more often in women, particularly with Crohn’s disease and colonic disease location, and in patients who required surgery. Jewish ancestry was associated with psoriasis and overall skin manifestations.

Smoking increased the risk for multiple EIMs, except for PSC, where there appeared to be a “protective” effect. Older age at diagnosis and a family history of IBD were associated with increased risk for certain EIMs as well.

In addition, the research team noted multiple serologic associations, such as immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgA, perinuclear antinuclear cytoplastic antibodies, and anti–Pseudomonas fluorescens–associated sequences with any EIM, as well as particular associations with PSC, such as anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies and anti-flagellin.

There were also genome-wide significant associations within the major histocompatibility complex and CPEB4. Genetic associations implicated tumor necrosis factor, Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription, and interleukin 6 as potential targets for EIMs.

“We are working with colleagues across the world to increase the sample size, as we believe there is more to find,” Dr. McGovern said. “Importantly, this includes non-European ancestry subjects, as there is an urgent need to increase the diversity of populations we study so advances in clinical care are available to all communities.”

Considering Target Therapies

As medicine becomes more specialized, physicians should remember to consider the whole patient while choosing treatment strategies.

“Sometimes doctors wear blinders to the whole person, and it’s important to be aware of a holistic approach, where a gastroenterologist also asks about potential joint inflammation or a rheumatologist asks about bowel inflammation,” said David Rubin, MD, AGAF, chief of the Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at the University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago.

Dr. Rubin, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched and published on EIMs in IBD. He and colleagues analyzed the prevalence, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation of EIMs to better understand possibilities for disease management.

“As we’ve gotten a better understanding of the immune system, we’ve learned that an EIM can sometimes provide a clue to the treatment we might use,” he said. “Given a similar amount of bowel inflammation, if one patient also has joint pain and another doesn’t, we might choose different treatments based on the immune pathway that might be involved.”

In future studies, researchers may consider whether these genetic or serologic markers could predict EIM manifestation before it occurs clinically, Dr. Rubin said. He and colleagues are also studying the links between IBD and mental health associations.

“So far, we don’t have a blood test or biopsy test that tells you which treatment is more or less likely to work, so we need to think carefully as clinicians and look to other organ systems for clues,” he said. “It’s not only more efficient to pick a single therapy to treat both the skin and bowel, but it may actually be more effective if both have a particular dominant pathway.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel and Immunobiology Research Institute. Several authors reported consultant roles or other associations with pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Rubin reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a recent study.

For instance, antinuclear cytoplastic antibody is associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in Crohn’s disease, and CPEB4 genetic variation is associated with skin manifestations.

“Up to 40% of people with IBD suffer with symptoms from inflammation that occurs outside the gut, particularly affecting the liver, skin, and joints. These symptoms can often have a bigger impact on quality of life than the gut inflammation itself and can actually be life-threatening,” said senior author Dermot McGovern, MD, PhD, AGAF, director of translational medicine at the F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Immunobiology Research Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“With the advances in therapies for IBD, including availability of gut-selective agents, treatment choices often incorporate whether a patient has one of these manifestations or not,” he said. “We need to understand who is at increased risk of these and why.”

The study was published in Gastroenterology .

Analyzing Associations

Dr. McGovern and colleagues analyzed data for 12,083 unrelated European ancestry IBD cases with presence or absence of EIMs across four cohorts in the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center IBD Research Repository, National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases IBD Genetics Consortium, Sinai Helmsley Alliance for Research Excellence Consortium, and Risk Stratification and Identification of Immunogenetic and Microbial Markers of Rapid Disease Progression in Children with Crohn’s Disease.

In particular, the researchers looked at EIM phenotypes such as ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis, PSC, peripheral arthritis, and skin and ocular manifestations. They analyzed clinical and serologic parameters through regression analyses using a mixed-effects model, as well as within-case logistic regression for genetic associations.

Overall, 14% of patients had at least one EIM. Contrary to previous reports, only 2% had multiple EIMs, and most co-occurrences were negatively correlated. Nearly all EIMs were more common in Crohn’s disease, except for PSC, which was more common in ulcerative colitis.

In general, EIMs occurred more often in women, particularly with Crohn’s disease and colonic disease location, and in patients who required surgery. Jewish ancestry was associated with psoriasis and overall skin manifestations.

Smoking increased the risk for multiple EIMs, except for PSC, where there appeared to be a “protective” effect. Older age at diagnosis and a family history of IBD were associated with increased risk for certain EIMs as well.

In addition, the research team noted multiple serologic associations, such as immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgA, perinuclear antinuclear cytoplastic antibodies, and anti–Pseudomonas fluorescens–associated sequences with any EIM, as well as particular associations with PSC, such as anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies and anti-flagellin.

There were also genome-wide significant associations within the major histocompatibility complex and CPEB4. Genetic associations implicated tumor necrosis factor, Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription, and interleukin 6 as potential targets for EIMs.

“We are working with colleagues across the world to increase the sample size, as we believe there is more to find,” Dr. McGovern said. “Importantly, this includes non-European ancestry subjects, as there is an urgent need to increase the diversity of populations we study so advances in clinical care are available to all communities.”

Considering Target Therapies

As medicine becomes more specialized, physicians should remember to consider the whole patient while choosing treatment strategies.

“Sometimes doctors wear blinders to the whole person, and it’s important to be aware of a holistic approach, where a gastroenterologist also asks about potential joint inflammation or a rheumatologist asks about bowel inflammation,” said David Rubin, MD, AGAF, chief of the Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at the University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago.

Dr. Rubin, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched and published on EIMs in IBD. He and colleagues analyzed the prevalence, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation of EIMs to better understand possibilities for disease management.

“As we’ve gotten a better understanding of the immune system, we’ve learned that an EIM can sometimes provide a clue to the treatment we might use,” he said. “Given a similar amount of bowel inflammation, if one patient also has joint pain and another doesn’t, we might choose different treatments based on the immune pathway that might be involved.”

In future studies, researchers may consider whether these genetic or serologic markers could predict EIM manifestation before it occurs clinically, Dr. Rubin said. He and colleagues are also studying the links between IBD and mental health associations.

“So far, we don’t have a blood test or biopsy test that tells you which treatment is more or less likely to work, so we need to think carefully as clinicians and look to other organ systems for clues,” he said. “It’s not only more efficient to pick a single therapy to treat both the skin and bowel, but it may actually be more effective if both have a particular dominant pathway.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel and Immunobiology Research Institute. Several authors reported consultant roles or other associations with pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Rubin reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a recent study.

For instance, antinuclear cytoplastic antibody is associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in Crohn’s disease, and CPEB4 genetic variation is associated with skin manifestations.

“Up to 40% of people with IBD suffer with symptoms from inflammation that occurs outside the gut, particularly affecting the liver, skin, and joints. These symptoms can often have a bigger impact on quality of life than the gut inflammation itself and can actually be life-threatening,” said senior author Dermot McGovern, MD, PhD, AGAF, director of translational medicine at the F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Immunobiology Research Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“With the advances in therapies for IBD, including availability of gut-selective agents, treatment choices often incorporate whether a patient has one of these manifestations or not,” he said. “We need to understand who is at increased risk of these and why.”

The study was published in Gastroenterology .

Analyzing Associations

Dr. McGovern and colleagues analyzed data for 12,083 unrelated European ancestry IBD cases with presence or absence of EIMs across four cohorts in the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center IBD Research Repository, National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases IBD Genetics Consortium, Sinai Helmsley Alliance for Research Excellence Consortium, and Risk Stratification and Identification of Immunogenetic and Microbial Markers of Rapid Disease Progression in Children with Crohn’s Disease.

In particular, the researchers looked at EIM phenotypes such as ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis, PSC, peripheral arthritis, and skin and ocular manifestations. They analyzed clinical and serologic parameters through regression analyses using a mixed-effects model, as well as within-case logistic regression for genetic associations.

Overall, 14% of patients had at least one EIM. Contrary to previous reports, only 2% had multiple EIMs, and most co-occurrences were negatively correlated. Nearly all EIMs were more common in Crohn’s disease, except for PSC, which was more common in ulcerative colitis.

In general, EIMs occurred more often in women, particularly with Crohn’s disease and colonic disease location, and in patients who required surgery. Jewish ancestry was associated with psoriasis and overall skin manifestations.

Smoking increased the risk for multiple EIMs, except for PSC, where there appeared to be a “protective” effect. Older age at diagnosis and a family history of IBD were associated with increased risk for certain EIMs as well.

In addition, the research team noted multiple serologic associations, such as immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgA, perinuclear antinuclear cytoplastic antibodies, and anti–Pseudomonas fluorescens–associated sequences with any EIM, as well as particular associations with PSC, such as anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies and anti-flagellin.

There were also genome-wide significant associations within the major histocompatibility complex and CPEB4. Genetic associations implicated tumor necrosis factor, Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription, and interleukin 6 as potential targets for EIMs.

“We are working with colleagues across the world to increase the sample size, as we believe there is more to find,” Dr. McGovern said. “Importantly, this includes non-European ancestry subjects, as there is an urgent need to increase the diversity of populations we study so advances in clinical care are available to all communities.”

Considering Target Therapies

As medicine becomes more specialized, physicians should remember to consider the whole patient while choosing treatment strategies.

“Sometimes doctors wear blinders to the whole person, and it’s important to be aware of a holistic approach, where a gastroenterologist also asks about potential joint inflammation or a rheumatologist asks about bowel inflammation,” said David Rubin, MD, AGAF, chief of the Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at the University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago.

Dr. Rubin, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched and published on EIMs in IBD. He and colleagues analyzed the prevalence, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation of EIMs to better understand possibilities for disease management.

“As we’ve gotten a better understanding of the immune system, we’ve learned that an EIM can sometimes provide a clue to the treatment we might use,” he said. “Given a similar amount of bowel inflammation, if one patient also has joint pain and another doesn’t, we might choose different treatments based on the immune pathway that might be involved.”

In future studies, researchers may consider whether these genetic or serologic markers could predict EIM manifestation before it occurs clinically, Dr. Rubin said. He and colleagues are also studying the links between IBD and mental health associations.

“So far, we don’t have a blood test or biopsy test that tells you which treatment is more or less likely to work, so we need to think carefully as clinicians and look to other organ systems for clues,” he said. “It’s not only more efficient to pick a single therapy to treat both the skin and bowel, but it may actually be more effective if both have a particular dominant pathway.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel and Immunobiology Research Institute. Several authors reported consultant roles or other associations with pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Rubin reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Top-Down Treatment Appears Better for Patients With Crohn’s Disease

according to a recent study.

Top-down treatment achieved substantially better outcomes at one year after diagnosis than step-up treatment, with nearly 80% of those receiving top-down therapy having both symptoms and inflammatory markers controlled, as compared with only 15% of those receiving accelerated step-up therapy.

“Up until now, the view has been: ‘Why would you use a more expensive treatment strategy and potentially overtreat people if there’s a chance they might do fine anyway?’ ” asked senior author Miles Parkes, MBBS, professor of translational gastroenterology at the University of Cambridge in England and director of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

“As we’ve shown, and as previous studies have demonstrated, there’s actually a pretty high risk that an individual with Crohn’s disease will experience disease flares and complications even in the first year after diagnosis,” he said. “We now know we can prevent the majority of adverse outcomes, including need for urgent surgery, by providing a treatment strategy that is safe and becoming increasingly affordable.”

The study was published in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

Comparing Treatments

Dr. Parkes and colleagues conducted a multicenter, open-label, biomarker-stratified randomized controlled trial among adults with newly diagnosed active Crohn’s disease. Participants were tested for a prognostic biomarker derived from T-cell transcriptional signatures and randomly assigned to a top-down or accelerated step-up treatment based on biomarker subgroup, endoscopic inflammation (mild, moderate, or severe), and extent (colonic or other).

The primary endpoint was sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission after completing a steroid induction (maximum 8-week course) to week 48. Remission was defined by a composite of symptoms and inflammatory markers at all visits, with a Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) score of less than 5 or resolved inflammatory markers or both, while a flare was defined as active symptoms (HBI ≥ 5) and raised inflammatory markers.

Across 40 UK hospitals, 386 patients (mean age, 33.6 years; 54% male) were randomized, with 193 receiving a top-down therapy of combination intravenous infliximab plus immunomodulator (azathioprine, low-dose mercaptopurine with allopurinol, or methotrexate) and 193 receiving an accelerated step-up therapy of an immunomodulator and then infliximab if further flares occurred after the steroid course. In the step-up group, 85% required escalation to an immunomodulator, and 41% required infliximab by week 48.

Overall, sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission was significantly more frequent in the top-down group than in the accelerated step-up group (among 149 of 189 patients vs 29 of 190 patients), at 79% vs 15%, marking an absolute difference of 64 percentage points.

Top-down treatment also showed greater efficacy in achieving endoscopic remission (67% vs 44%), improved quality of life, lower need for steroids, and reduced number of flares requiring treatment escalation.

In addition, there were fewer adverse events (168 vs 315) and fewer serious adverse events (15 vs 42) in the top-down group than in the step-up group. There were also fewer complications that required urgent abdominal surgery, with one in the top-down group for gallstone ileus and nine in the step-up group requiring intestinal resection for structuring or fistulating complications.

However, the biomarker showed no clinical utility, and none of the baseline measurements predicted which patients were at risk of adverse outcomes with the step-up approach, Dr. Parkes said.

“The key message is that Crohn’s is unpredictable, hence you are better off treating everyone who has significant disease at diagnosis with combo therapy (anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] plus immunomodulator) rather than ‘wait and see,’ as bad things happen to people with uncontrolled inflammation during that ‘wait and see’ stage,” he said.

Additional Considerations

In the PROFILE trial, the need for a prognostic biomarker was based on the lack of an effective, safe, and affordable treatment strategy for newly diagnosed patients, the study authors wrote, but effective top-down management could reduce the need for a biomarker.

“In one sense, this is a negative study as the blood-based CD8+ T-cell transcriptomic biomarker that was being studied was not predictive of outcomes at all. But PROFILE makes it very clear that early effective therapy leads to better outcomes than accelerated step-up therapy,” said Neeraj Narula, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and staff gastroenterologist focused on inflammatory bowel disease at Hamilton Health Sciences.

Dr. Narula, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the comparative effectiveness of biologics for endoscopic healing of the ileum and colon in Crohn’s disease. He and colleagues found that anti-TNF biologics were effective in achieving 1-year endoscopic healing in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

“These findings likely aren’t specific to infliximab/azathioprine, and I suspect similar outcomes would be shown for other advanced therapies used early in the course of disease,” he said. “There does remain a concern that using this strategy for all patients may lead to overtreatment of some, but perhaps any harm done by overtreatment of a minority may be offset by the harm resulting from undertreatment of the majority. It’s hard to say for sure, but it certainly gives us some food for thought.”

The study was funded by Wellcome and PredictImmune and jointly sponsored by the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Parkes and several authors declared fees and grants from numerous companies outside of this study. Dr. Narula reported no relevant disclosures.

according to a recent study.

Top-down treatment achieved substantially better outcomes at one year after diagnosis than step-up treatment, with nearly 80% of those receiving top-down therapy having both symptoms and inflammatory markers controlled, as compared with only 15% of those receiving accelerated step-up therapy.

“Up until now, the view has been: ‘Why would you use a more expensive treatment strategy and potentially overtreat people if there’s a chance they might do fine anyway?’ ” asked senior author Miles Parkes, MBBS, professor of translational gastroenterology at the University of Cambridge in England and director of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

“As we’ve shown, and as previous studies have demonstrated, there’s actually a pretty high risk that an individual with Crohn’s disease will experience disease flares and complications even in the first year after diagnosis,” he said. “We now know we can prevent the majority of adverse outcomes, including need for urgent surgery, by providing a treatment strategy that is safe and becoming increasingly affordable.”

The study was published in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

Comparing Treatments

Dr. Parkes and colleagues conducted a multicenter, open-label, biomarker-stratified randomized controlled trial among adults with newly diagnosed active Crohn’s disease. Participants were tested for a prognostic biomarker derived from T-cell transcriptional signatures and randomly assigned to a top-down or accelerated step-up treatment based on biomarker subgroup, endoscopic inflammation (mild, moderate, or severe), and extent (colonic or other).

The primary endpoint was sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission after completing a steroid induction (maximum 8-week course) to week 48. Remission was defined by a composite of symptoms and inflammatory markers at all visits, with a Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) score of less than 5 or resolved inflammatory markers or both, while a flare was defined as active symptoms (HBI ≥ 5) and raised inflammatory markers.

Across 40 UK hospitals, 386 patients (mean age, 33.6 years; 54% male) were randomized, with 193 receiving a top-down therapy of combination intravenous infliximab plus immunomodulator (azathioprine, low-dose mercaptopurine with allopurinol, or methotrexate) and 193 receiving an accelerated step-up therapy of an immunomodulator and then infliximab if further flares occurred after the steroid course. In the step-up group, 85% required escalation to an immunomodulator, and 41% required infliximab by week 48.

Overall, sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission was significantly more frequent in the top-down group than in the accelerated step-up group (among 149 of 189 patients vs 29 of 190 patients), at 79% vs 15%, marking an absolute difference of 64 percentage points.

Top-down treatment also showed greater efficacy in achieving endoscopic remission (67% vs 44%), improved quality of life, lower need for steroids, and reduced number of flares requiring treatment escalation.

In addition, there were fewer adverse events (168 vs 315) and fewer serious adverse events (15 vs 42) in the top-down group than in the step-up group. There were also fewer complications that required urgent abdominal surgery, with one in the top-down group for gallstone ileus and nine in the step-up group requiring intestinal resection for structuring or fistulating complications.

However, the biomarker showed no clinical utility, and none of the baseline measurements predicted which patients were at risk of adverse outcomes with the step-up approach, Dr. Parkes said.

“The key message is that Crohn’s is unpredictable, hence you are better off treating everyone who has significant disease at diagnosis with combo therapy (anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] plus immunomodulator) rather than ‘wait and see,’ as bad things happen to people with uncontrolled inflammation during that ‘wait and see’ stage,” he said.

Additional Considerations

In the PROFILE trial, the need for a prognostic biomarker was based on the lack of an effective, safe, and affordable treatment strategy for newly diagnosed patients, the study authors wrote, but effective top-down management could reduce the need for a biomarker.

“In one sense, this is a negative study as the blood-based CD8+ T-cell transcriptomic biomarker that was being studied was not predictive of outcomes at all. But PROFILE makes it very clear that early effective therapy leads to better outcomes than accelerated step-up therapy,” said Neeraj Narula, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and staff gastroenterologist focused on inflammatory bowel disease at Hamilton Health Sciences.

Dr. Narula, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the comparative effectiveness of biologics for endoscopic healing of the ileum and colon in Crohn’s disease. He and colleagues found that anti-TNF biologics were effective in achieving 1-year endoscopic healing in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

“These findings likely aren’t specific to infliximab/azathioprine, and I suspect similar outcomes would be shown for other advanced therapies used early in the course of disease,” he said. “There does remain a concern that using this strategy for all patients may lead to overtreatment of some, but perhaps any harm done by overtreatment of a minority may be offset by the harm resulting from undertreatment of the majority. It’s hard to say for sure, but it certainly gives us some food for thought.”

The study was funded by Wellcome and PredictImmune and jointly sponsored by the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Parkes and several authors declared fees and grants from numerous companies outside of this study. Dr. Narula reported no relevant disclosures.

according to a recent study.

Top-down treatment achieved substantially better outcomes at one year after diagnosis than step-up treatment, with nearly 80% of those receiving top-down therapy having both symptoms and inflammatory markers controlled, as compared with only 15% of those receiving accelerated step-up therapy.

“Up until now, the view has been: ‘Why would you use a more expensive treatment strategy and potentially overtreat people if there’s a chance they might do fine anyway?’ ” asked senior author Miles Parkes, MBBS, professor of translational gastroenterology at the University of Cambridge in England and director of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

“As we’ve shown, and as previous studies have demonstrated, there’s actually a pretty high risk that an individual with Crohn’s disease will experience disease flares and complications even in the first year after diagnosis,” he said. “We now know we can prevent the majority of adverse outcomes, including need for urgent surgery, by providing a treatment strategy that is safe and becoming increasingly affordable.”

The study was published in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

Comparing Treatments

Dr. Parkes and colleagues conducted a multicenter, open-label, biomarker-stratified randomized controlled trial among adults with newly diagnosed active Crohn’s disease. Participants were tested for a prognostic biomarker derived from T-cell transcriptional signatures and randomly assigned to a top-down or accelerated step-up treatment based on biomarker subgroup, endoscopic inflammation (mild, moderate, or severe), and extent (colonic or other).

The primary endpoint was sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission after completing a steroid induction (maximum 8-week course) to week 48. Remission was defined by a composite of symptoms and inflammatory markers at all visits, with a Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) score of less than 5 or resolved inflammatory markers or both, while a flare was defined as active symptoms (HBI ≥ 5) and raised inflammatory markers.

Across 40 UK hospitals, 386 patients (mean age, 33.6 years; 54% male) were randomized, with 193 receiving a top-down therapy of combination intravenous infliximab plus immunomodulator (azathioprine, low-dose mercaptopurine with allopurinol, or methotrexate) and 193 receiving an accelerated step-up therapy of an immunomodulator and then infliximab if further flares occurred after the steroid course. In the step-up group, 85% required escalation to an immunomodulator, and 41% required infliximab by week 48.

Overall, sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission was significantly more frequent in the top-down group than in the accelerated step-up group (among 149 of 189 patients vs 29 of 190 patients), at 79% vs 15%, marking an absolute difference of 64 percentage points.

Top-down treatment also showed greater efficacy in achieving endoscopic remission (67% vs 44%), improved quality of life, lower need for steroids, and reduced number of flares requiring treatment escalation.

In addition, there were fewer adverse events (168 vs 315) and fewer serious adverse events (15 vs 42) in the top-down group than in the step-up group. There were also fewer complications that required urgent abdominal surgery, with one in the top-down group for gallstone ileus and nine in the step-up group requiring intestinal resection for structuring or fistulating complications.

However, the biomarker showed no clinical utility, and none of the baseline measurements predicted which patients were at risk of adverse outcomes with the step-up approach, Dr. Parkes said.

“The key message is that Crohn’s is unpredictable, hence you are better off treating everyone who has significant disease at diagnosis with combo therapy (anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] plus immunomodulator) rather than ‘wait and see,’ as bad things happen to people with uncontrolled inflammation during that ‘wait and see’ stage,” he said.

Additional Considerations

In the PROFILE trial, the need for a prognostic biomarker was based on the lack of an effective, safe, and affordable treatment strategy for newly diagnosed patients, the study authors wrote, but effective top-down management could reduce the need for a biomarker.

“In one sense, this is a negative study as the blood-based CD8+ T-cell transcriptomic biomarker that was being studied was not predictive of outcomes at all. But PROFILE makes it very clear that early effective therapy leads to better outcomes than accelerated step-up therapy,” said Neeraj Narula, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and staff gastroenterologist focused on inflammatory bowel disease at Hamilton Health Sciences.

Dr. Narula, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the comparative effectiveness of biologics for endoscopic healing of the ileum and colon in Crohn’s disease. He and colleagues found that anti-TNF biologics were effective in achieving 1-year endoscopic healing in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

“These findings likely aren’t specific to infliximab/azathioprine, and I suspect similar outcomes would be shown for other advanced therapies used early in the course of disease,” he said. “There does remain a concern that using this strategy for all patients may lead to overtreatment of some, but perhaps any harm done by overtreatment of a minority may be offset by the harm resulting from undertreatment of the majority. It’s hard to say for sure, but it certainly gives us some food for thought.”

The study was funded by Wellcome and PredictImmune and jointly sponsored by the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Parkes and several authors declared fees and grants from numerous companies outside of this study. Dr. Narula reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE LANCET GASTROENTEROLOGY & HEPATOLOGY

Family Size, Dog Ownership Linked With Reduced Risk of Crohn’s

, according to investigators.

Those who live with a pet bird may be more likely to develop CD, although few participants in the study lived with birds, requiring a cautious interpretation of this latter finding, lead author Mingyue Xue, PhD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and colleagues reported.

“Environmental factors, such as smoking, large families, urban environments, and exposure to pets, have been shown to be associated with the risk of CD development,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, most of these studies were based on a retrospective study design, which makes it challenging to understand when and how environmental factors trigger the biological changes that lead to disease.”

The present study prospectively followed 4289 asymptomatic first-degree relatives (FDRs) of patients with CD. Environmental factors were identified via regression models that also considered biological factors, including gut inflammation via fecal calprotectin (FCP) levels, altered intestinal permeability measured by urinary fractional excretion of lactulose to mannitol ratio (LMR), and fecal microbiome composition through 16S rRNA sequencing.

After a median follow-up period of 5.62 years, 86 FDRs (1.9%) developed CD.

Living in a household of at least three people in the first year of life was associated with a 57% reduced risk of CD development (hazard ratio [HR], 0.43; P = .019). Similarly, living with a pet dog between the ages of 5 and 15 also demonstrated a protective effect, dropping risk of CD by 39% (HR, 0.61; P = .025).

“Our analysis revealed a protective trend of living with dogs that transcends the age of exposure, suggesting that dog ownership could confer health benefits in reducing the risk of CD,” the investigators wrote. “Our study also found that living in a large family during the first year of life is significantly associated with the future onset of CD, aligning with prior research that indicates that a larger family size in the first year of life can reduce the risk of developing IBD.”

In contrast, the study identified bird ownership at time of recruitment as a risk factor for CD, increasing risk almost three-fold (HR, 2.84; P = .005). The investigators urged a careful interpretation of this latter finding, however, as relatively few FDRs lived with birds.

“[A]lthough our sample size can be considered large, some environmental variables were uncommon, such as the participants having birds as pets, and would greatly benefit from replication of our findings in other cohorts,” Dr. Xue and colleagues noted.

They suggested several possible ways in which the above environmental factors may impact CD risk, including effects on subclinical inflammation, microbiome composition, and gut permeability.

“Understanding the relationship between CD-related environmental factors and these predisease biomarkers may shed light on the underlying mechanisms by which environmental factors impact host health and ultimately lead to CD onset,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, and others. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, according to investigators.

Those who live with a pet bird may be more likely to develop CD, although few participants in the study lived with birds, requiring a cautious interpretation of this latter finding, lead author Mingyue Xue, PhD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and colleagues reported.

“Environmental factors, such as smoking, large families, urban environments, and exposure to pets, have been shown to be associated with the risk of CD development,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, most of these studies were based on a retrospective study design, which makes it challenging to understand when and how environmental factors trigger the biological changes that lead to disease.”

The present study prospectively followed 4289 asymptomatic first-degree relatives (FDRs) of patients with CD. Environmental factors were identified via regression models that also considered biological factors, including gut inflammation via fecal calprotectin (FCP) levels, altered intestinal permeability measured by urinary fractional excretion of lactulose to mannitol ratio (LMR), and fecal microbiome composition through 16S rRNA sequencing.

After a median follow-up period of 5.62 years, 86 FDRs (1.9%) developed CD.

Living in a household of at least three people in the first year of life was associated with a 57% reduced risk of CD development (hazard ratio [HR], 0.43; P = .019). Similarly, living with a pet dog between the ages of 5 and 15 also demonstrated a protective effect, dropping risk of CD by 39% (HR, 0.61; P = .025).

“Our analysis revealed a protective trend of living with dogs that transcends the age of exposure, suggesting that dog ownership could confer health benefits in reducing the risk of CD,” the investigators wrote. “Our study also found that living in a large family during the first year of life is significantly associated with the future onset of CD, aligning with prior research that indicates that a larger family size in the first year of life can reduce the risk of developing IBD.”

In contrast, the study identified bird ownership at time of recruitment as a risk factor for CD, increasing risk almost three-fold (HR, 2.84; P = .005). The investigators urged a careful interpretation of this latter finding, however, as relatively few FDRs lived with birds.

“[A]lthough our sample size can be considered large, some environmental variables were uncommon, such as the participants having birds as pets, and would greatly benefit from replication of our findings in other cohorts,” Dr. Xue and colleagues noted.

They suggested several possible ways in which the above environmental factors may impact CD risk, including effects on subclinical inflammation, microbiome composition, and gut permeability.

“Understanding the relationship between CD-related environmental factors and these predisease biomarkers may shed light on the underlying mechanisms by which environmental factors impact host health and ultimately lead to CD onset,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, and others. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, according to investigators.

Those who live with a pet bird may be more likely to develop CD, although few participants in the study lived with birds, requiring a cautious interpretation of this latter finding, lead author Mingyue Xue, PhD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and colleagues reported.

“Environmental factors, such as smoking, large families, urban environments, and exposure to pets, have been shown to be associated with the risk of CD development,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, most of these studies were based on a retrospective study design, which makes it challenging to understand when and how environmental factors trigger the biological changes that lead to disease.”

The present study prospectively followed 4289 asymptomatic first-degree relatives (FDRs) of patients with CD. Environmental factors were identified via regression models that also considered biological factors, including gut inflammation via fecal calprotectin (FCP) levels, altered intestinal permeability measured by urinary fractional excretion of lactulose to mannitol ratio (LMR), and fecal microbiome composition through 16S rRNA sequencing.

After a median follow-up period of 5.62 years, 86 FDRs (1.9%) developed CD.

Living in a household of at least three people in the first year of life was associated with a 57% reduced risk of CD development (hazard ratio [HR], 0.43; P = .019). Similarly, living with a pet dog between the ages of 5 and 15 also demonstrated a protective effect, dropping risk of CD by 39% (HR, 0.61; P = .025).

“Our analysis revealed a protective trend of living with dogs that transcends the age of exposure, suggesting that dog ownership could confer health benefits in reducing the risk of CD,” the investigators wrote. “Our study also found that living in a large family during the first year of life is significantly associated with the future onset of CD, aligning with prior research that indicates that a larger family size in the first year of life can reduce the risk of developing IBD.”

In contrast, the study identified bird ownership at time of recruitment as a risk factor for CD, increasing risk almost three-fold (HR, 2.84; P = .005). The investigators urged a careful interpretation of this latter finding, however, as relatively few FDRs lived with birds.

“[A]lthough our sample size can be considered large, some environmental variables were uncommon, such as the participants having birds as pets, and would greatly benefit from replication of our findings in other cohorts,” Dr. Xue and colleagues noted.

They suggested several possible ways in which the above environmental factors may impact CD risk, including effects on subclinical inflammation, microbiome composition, and gut permeability.

“Understanding the relationship between CD-related environmental factors and these predisease biomarkers may shed light on the underlying mechanisms by which environmental factors impact host health and ultimately lead to CD onset,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, and others. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Environment More Than Genes Affects Age of IBD Diagnosis

a large study of IBD patients reported.

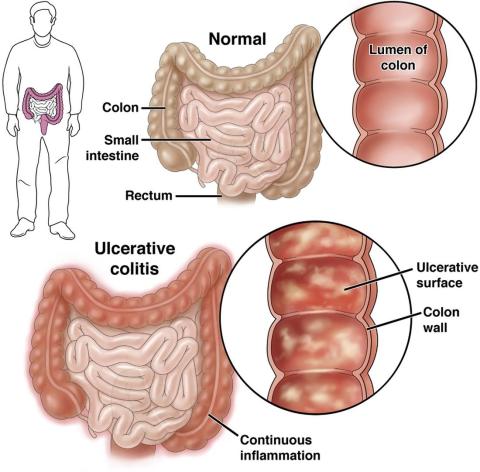

Published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology , the study found that environment influences the onset of both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), and exposures typical in Western society lower the age of diagnosis. These factors include birth in a developed nation, delivery by C-section, and more bathrooms in the home, according to Oriana M. Damas, MD, MSCTI, an associate professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida and colleagues.

Environmental factors explained 21% of the variance in age of CD diagnosis and 39% of the variance in age of UC diagnosis. In models incorporating both genetic and environmental risk scores, the environment was the only significant factor associated with younger age of IBD diagnosis in all groups.

Several epidemiologic studies have examined environmental culprits in IBD, and others have examined genetic risk factors, Dr. Damas said in an interview. “But we had not seen any studies that examined the influence of both [of] these on age of IBD development.” Her group’s working hypothesis that environment would have a greater effect than genetics was borne out.

“Additionally, very few studies have examined the contribution of genetics or environmental factors in Hispanic individuals, and our study examined the contribution of these factors in this understudied population,” she added.

According to Dr. Damas, the findings’ most immediate clinical relevance is for counseling people with a family history of IBD. “I think it’s important for concerned patients to know that IBD is not solely genetic and that several environmental factors can shape disease risk to a greater extent than genetic predisposition,” she said

Westernization is increasingly considered a contributor to the global increase in IBD, which has been diagnosed in an estimated 2.39 million Americans . In genetically predisposed individuals, environmental culprits in developed countries are thought to negatively shape the intestinal microbiome’s composition into a less tolerant and more proinflammatory state, the authors noted.

According to the “hygiene hypothesis,” the oversanitization of life in the developed world is partly to blame. “A cleaner environment at home, part of the hygiene hypothesis, has been postulated as a theory to help explain the rise of autoimmune diseases in the 21st century and may play an important part in explaining our study findings,” the authors wrote.

Population-based studies have also pointed to antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, smoking, cesarean delivery, lack of breastfeeding, and nonexposure to farm animals as other risk factors for IBD.

Study Details

To compare the effect of environmental vs genetic risk factors, the questionnaire-based study surveyed 2952 IBD patients from a tertiary care referral center — 58.9% with CD, 45.83% of Hispanic background, and 53.18% of non-Hispanic White (NHW) ethnicity. There were too few available Black and Asian patients to be included in the cohort. Data were collected from 2017 to 2022.

The mean age of patients was 39.71 years, and 34.14% were defined as born outside of the US mainland. Foreign-born patients were further characterized as from developed nations vs developing nations; 81.3% in this subgroup came from the latter. A detailed questionnaire probed 13 potential environmental factors from type of birth to domestic living conditions, medications, and smoking across several different age groups. Blood was drawn to genotype participants and to create a genetic risk score.

Early plastic water bottle use — which has been linked to inflammatory microplastics in the intestines — and residing in homes with more than one bathroom (and presumably less exposure to infections) were also associated with younger age at diagnosis. Susceptibility to environmental exposures was similar in Hispanic and NHW patients.

“It was interesting to find an association between reported plastic water bottle use and younger age of IBD diagnosis,” said Dr. Damas. “Because this is a self-reported intake, we need more studies to confirm this. However, this finding falls in line with other recent studies showing a potential association between microplastics and disease states, including IBD. The next step is to measure for traces of environmental contaminants in human samples of patients with IBD.”

Unlike previous studies, this analysis did not find parasitic infections, pets, and antibiotics to be associated with age of IBD diagnosis.

“This is an interesting and important study,” commented Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MBBS, MPH, AGAF, director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the study. “There are few environmental risk factor studies looking at non-White populations and to that end, this is a very large and well-done analysis looking at environmental factors among Hispanic patients with IBD.”

He added that, while most studies have just compared factors between cases and controls, “this is an interesting examination of the impact of such factors on age of onset.”

Dr. Ananthakrishnan stressed, however, that further work is needed to expand on these findings.” The addition of a control group would help determine how these factors actually modify disease risk. It is also intriguing that environmental factors more strongly predict age of onset than genetic risk. That only highlights the fact that IBD is in large part an environmentally influenced disease, suggesting there is exciting opportunity for environmental modification to address disease onset.”

Offering another outsider’s perspective, Manasi Agrawal, MD, MS, an assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and not a participant in the study, agreed that the findings highlight the contribution of early life and childhood environmental factors to IBD risk relative to genetic variants. “The relative importance of the environment compared to genetic risk toward IBD, timing of exposure, and impact on age at IBD diagnosis is a novel and important finding. These data will help contextualize how we communicate disease risk and potential prevention approaches.”

She added that future research should measure various exposures, such as pollutants in preclinical biological samples. “Mechanistic data on their downstream effects are needed to understand IBD pathogenesis and develop prevention efforts.”

According to the authors, theirs is the first study of its kind to examine the contribution of cumulative environmental factors, age-dependent exposures, and genetic predisposition to age of IBD diagnosis in a diverse IBD cohort.

The authors listed no specific funding for this study and had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Ananthakrishnan and Dr. Agrawal had no relevant competing interests.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

a large study of IBD patients reported.