User login

Academic hospitals offer better AML survival

ORLANDO – Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) initially treated at an academic center lived significantly longer than those treated at nonacademic centers, a database analysis shows.

Median overall survival increased from 7 months at a nonacademic center to 12.6 months at an academic center (P less than .001).

One-year overall survival rates were also significantly better at 51% vs. 39% (P less than .001).

The difference remained significant even after controlling for important confounders including age, comorbidity burden, receipt of chemotherapy, transplant, and delay between diagnosis and treatment, Mr. Smith Giri reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“From a policy perspective, it may be useful to know whether these results are due to higher volume of cases, more advanced technology, expanded role of specialists, or greater, round-the-clock availability of resident physicians,” said Mr. Giri of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis.

Prior studies in cancer have suggested better overall survival among breast cancer patients treated at academic centers, but this is the first study looking at outcomes in AML, the most common acute leukemia in adults.

Using the National Cancer Database Participant User File, the investigators identified 7,823 patients with AML who received their initial therapy at the reporting facility from 1998 to 2011. The database collects information from more than 1,500 Commission on Cancer (CoC)–accredited facilities. Of the 7,823 patients, 4,681 (60%) were treated at an AC (academic/research program) and 3,142 at a non-AC (community cancer program/comprehensive community cancer program).

Patients treated at an AC were significantly younger than those treated at a non-AC (median 62 years vs. 67 years), tended to be of nonwhite race, less educated, have a lower income, and more comorbidities.

Receipt of chemotherapy (97.4% vs. 94.5%) and transplant (9% vs. 2.4%) were significantly higher at an AC than a non-AC (both P less than .001).

Kaplan Meier survival curves suggested disparate survival curves between the two groups, mainly within the first 5 years of follow-up (P less than .001), Mr. Giri said.

In multivariate model analysis, the non-AC group had significantly worse risk adjusted 30-day mortality than the AC group (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval 1.33-1.74; P less than .001) and worse overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% CI 1.07-1.19; P less than .001).

The study (Ab. 533) findings should be interpreted with caution because of its limitations, including the lack of information on AML risk type in the database, the fact that administrative datasets are prone to coding errors, and because the analysis did not adjust for hospital volume, which has been shown to affect survival, he said. Also, because there are more than 3,500 non–Coc approved hospitals, the sample may not be representative of overall U.S. hospitals.

During a discussion of the results, Mr. Giri acknowledged that patients treated at academic centers may have greater access to clinical trials and experimental agents. Future analyses should also distinguish patients with a diagnosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia, a distinct subset of AML.

ORLANDO – Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) initially treated at an academic center lived significantly longer than those treated at nonacademic centers, a database analysis shows.

Median overall survival increased from 7 months at a nonacademic center to 12.6 months at an academic center (P less than .001).

One-year overall survival rates were also significantly better at 51% vs. 39% (P less than .001).

The difference remained significant even after controlling for important confounders including age, comorbidity burden, receipt of chemotherapy, transplant, and delay between diagnosis and treatment, Mr. Smith Giri reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“From a policy perspective, it may be useful to know whether these results are due to higher volume of cases, more advanced technology, expanded role of specialists, or greater, round-the-clock availability of resident physicians,” said Mr. Giri of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis.

Prior studies in cancer have suggested better overall survival among breast cancer patients treated at academic centers, but this is the first study looking at outcomes in AML, the most common acute leukemia in adults.

Using the National Cancer Database Participant User File, the investigators identified 7,823 patients with AML who received their initial therapy at the reporting facility from 1998 to 2011. The database collects information from more than 1,500 Commission on Cancer (CoC)–accredited facilities. Of the 7,823 patients, 4,681 (60%) were treated at an AC (academic/research program) and 3,142 at a non-AC (community cancer program/comprehensive community cancer program).

Patients treated at an AC were significantly younger than those treated at a non-AC (median 62 years vs. 67 years), tended to be of nonwhite race, less educated, have a lower income, and more comorbidities.

Receipt of chemotherapy (97.4% vs. 94.5%) and transplant (9% vs. 2.4%) were significantly higher at an AC than a non-AC (both P less than .001).

Kaplan Meier survival curves suggested disparate survival curves between the two groups, mainly within the first 5 years of follow-up (P less than .001), Mr. Giri said.

In multivariate model analysis, the non-AC group had significantly worse risk adjusted 30-day mortality than the AC group (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval 1.33-1.74; P less than .001) and worse overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% CI 1.07-1.19; P less than .001).

The study (Ab. 533) findings should be interpreted with caution because of its limitations, including the lack of information on AML risk type in the database, the fact that administrative datasets are prone to coding errors, and because the analysis did not adjust for hospital volume, which has been shown to affect survival, he said. Also, because there are more than 3,500 non–Coc approved hospitals, the sample may not be representative of overall U.S. hospitals.

During a discussion of the results, Mr. Giri acknowledged that patients treated at academic centers may have greater access to clinical trials and experimental agents. Future analyses should also distinguish patients with a diagnosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia, a distinct subset of AML.

ORLANDO – Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) initially treated at an academic center lived significantly longer than those treated at nonacademic centers, a database analysis shows.

Median overall survival increased from 7 months at a nonacademic center to 12.6 months at an academic center (P less than .001).

One-year overall survival rates were also significantly better at 51% vs. 39% (P less than .001).

The difference remained significant even after controlling for important confounders including age, comorbidity burden, receipt of chemotherapy, transplant, and delay between diagnosis and treatment, Mr. Smith Giri reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“From a policy perspective, it may be useful to know whether these results are due to higher volume of cases, more advanced technology, expanded role of specialists, or greater, round-the-clock availability of resident physicians,” said Mr. Giri of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis.

Prior studies in cancer have suggested better overall survival among breast cancer patients treated at academic centers, but this is the first study looking at outcomes in AML, the most common acute leukemia in adults.

Using the National Cancer Database Participant User File, the investigators identified 7,823 patients with AML who received their initial therapy at the reporting facility from 1998 to 2011. The database collects information from more than 1,500 Commission on Cancer (CoC)–accredited facilities. Of the 7,823 patients, 4,681 (60%) were treated at an AC (academic/research program) and 3,142 at a non-AC (community cancer program/comprehensive community cancer program).

Patients treated at an AC were significantly younger than those treated at a non-AC (median 62 years vs. 67 years), tended to be of nonwhite race, less educated, have a lower income, and more comorbidities.

Receipt of chemotherapy (97.4% vs. 94.5%) and transplant (9% vs. 2.4%) were significantly higher at an AC than a non-AC (both P less than .001).

Kaplan Meier survival curves suggested disparate survival curves between the two groups, mainly within the first 5 years of follow-up (P less than .001), Mr. Giri said.

In multivariate model analysis, the non-AC group had significantly worse risk adjusted 30-day mortality than the AC group (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval 1.33-1.74; P less than .001) and worse overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% CI 1.07-1.19; P less than .001).

The study (Ab. 533) findings should be interpreted with caution because of its limitations, including the lack of information on AML risk type in the database, the fact that administrative datasets are prone to coding errors, and because the analysis did not adjust for hospital volume, which has been shown to affect survival, he said. Also, because there are more than 3,500 non–Coc approved hospitals, the sample may not be representative of overall U.S. hospitals.

During a discussion of the results, Mr. Giri acknowledged that patients treated at academic centers may have greater access to clinical trials and experimental agents. Future analyses should also distinguish patients with a diagnosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia, a distinct subset of AML.

AT ASH 2015

Key clinical point: Academic hospitals tend to have better short- and long-term mortality for patients with AML than nonacademic hospitals.

Major finding: Median overall survival was 12.6 months at an academic center vs. 7 months at a nonacademic center (P less than .001).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 7,823 patients with AML.

Disclosures: The research was supported in part by a grant from the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The National Cancer Database is jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons and American Cancer Society. Mr. Giri reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Surprising finding in upfront use of idelalisib monotherapy

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators have observed early fulminant hepatotoxicity in a subset of primarily younger chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with idelalisib monotherapy in the frontline setting.

In a phase 2 study of idelalisib plus ofatumumab, 52% of the 24 patients enrolled experienced grade 3 or higher hepatotoxicity shortly after idelalisib was started.

The investigators say this may occur because a proportion of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood decreases while patients are on idelalisib. The team believes this early hepatotoxicity is immune-mediated.

Benjamin Lampson, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, described these surprising findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 497.*

Study design and patient demographics

Patients received 150 mg of idelalisib twice daily as monotherapy on days 1 through 56. They then received combination therapy with idelalisib plus ofatumumab for 8 weekly infusions, followed by 4 monthly infusions through day 225, and then idelalisib monotherapy indefinitely.

The primary endpoint of overall response rate was assessed 2 months after the completion of combination therapy.

“This dosing strategy is slightly different than what has been previously used in trials combining these particular drugs,” Dr Lampson said. “Specifically, previously reported trials started these agents simultaneously without a lead-in period of monotherapy.”

The investigators monitored the patients weekly for toxicities during the 2-month monotherapy lead-in period.

Three-quarters of the patients are male. Their median age is 67.4 years (range, 57.6–84.9), 54% have unmutated IgHV, 17% have deletion 17p or TP53 mutation, 4% have deletion 11q, and 54% have deletion 13q.

The patients received no prior therapies.

Results

The trial is currently ongoing.

The 24 patients enrolled as of early November have been on therapy a median of 7.7 months, for a median follow-up time of 14.7 months.

“What we began to notice after enrolling just a few subjects on the trial was that severe hepatotoxicity was occurring shortly after initiating idelalisib,” Dr Lampson said.

In the first 2 months of therapy, 52% of patients developed transaminitis, and 13% developed colitis or diarrhea, all grade 3 or higher. Thirteen percent developed pneumonitis of any grade.

Younger age is a risk factor for early hepatotoxicity, Dr Lampson said, with a significance of P=0.02. All subjects age 65 or younger (n=7) required systemic steroids to treat their toxicities.

Hepatotoxicity developed in a median of 28 days, he said, “and the hepatotoxicity is typically occurring before the first dose of ofatumumab is administered at week 8, suggesting that idelalisib alone is the cause of the hepatotoxicity.”

Dr Lampson noted that toxicities resolved rapidly with steroids.

“I do want to point out that all subjects evaluable for a response have had a response,” he added. “Additionally, in all subjects where treatment has been discontinued, the discontinuation was due to adverse events rather than disease progression.”

Twelve patients with grade 2 or higher transaminitis were re-challenged with idelalisib after holding the drug for toxicity.

Five patients were re-challenged while off steroids, and 4 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days. Seven patients were re-challenged while on steroids, and 2 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days.

“In general, our experience has been, if idelalisib is resumed while the subject remains on steroids, the drug is more likely to be tolerated and the subject can eventually be taken off steroids,” Dr Lampson said.

Comparison with earlier studies

The investigators compared the frequency of toxicity in their trial to earlier studies of idelalisib (Brown, Blood 2014; Coutre, EHA 2015, abstr P588; O’Brien, Blood 2015).

They found that grade 3 or higher transaminitis (52%) and any grade pneumonitis (13%) were higher in their trial than in the 3 other trials.

Colitis/diarrhea was about the same in 2 of the 3 other trials. But in the paper by O’Brien et al, 42% of patients experienced grade 3 or greater colitis/diarrhea.

The lower rate of colitis in the present trial may be due to the shorter follow-up, Dr Lampson said, as colitis is a late adverse event.

The O’Brien trial was also an upfront study, so patients had no prior therapies. The investigators observed that toxicities appeared to be more common in less heavily pretreated patients.

“As the median number of prior therapies decreases,” Dr Lampson said, “the frequency of adverse events increases.”

He noted that, in the O’Brien trial, idelalisib was started simultaneously with the other drugs, perhaps accounting for its somewhat lower rate (21%) of grade 3 or higher transaminitis.

Additionally, the patient population in the O’Brien trial was older than the population in the current trial, which could account for the higher rate of transaminitis, as younger age is a risk factor.

Decrease in regulatory T cells

Investigators noted a decrease in regulatory T cells while patients were on therapy. Eleven of 15 patients (73%) with matched samples had a significant (P<0.05) decrease in the percentage of T cells over time.

This, they say, could provide a possible explanation for the development of early hepatotoxicity.

The trial is investigator-initiated and funded by Gilead Sciences. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differs from the abstract.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators have observed early fulminant hepatotoxicity in a subset of primarily younger chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with idelalisib monotherapy in the frontline setting.

In a phase 2 study of idelalisib plus ofatumumab, 52% of the 24 patients enrolled experienced grade 3 or higher hepatotoxicity shortly after idelalisib was started.

The investigators say this may occur because a proportion of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood decreases while patients are on idelalisib. The team believes this early hepatotoxicity is immune-mediated.

Benjamin Lampson, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, described these surprising findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 497.*

Study design and patient demographics

Patients received 150 mg of idelalisib twice daily as monotherapy on days 1 through 56. They then received combination therapy with idelalisib plus ofatumumab for 8 weekly infusions, followed by 4 monthly infusions through day 225, and then idelalisib monotherapy indefinitely.

The primary endpoint of overall response rate was assessed 2 months after the completion of combination therapy.

“This dosing strategy is slightly different than what has been previously used in trials combining these particular drugs,” Dr Lampson said. “Specifically, previously reported trials started these agents simultaneously without a lead-in period of monotherapy.”

The investigators monitored the patients weekly for toxicities during the 2-month monotherapy lead-in period.

Three-quarters of the patients are male. Their median age is 67.4 years (range, 57.6–84.9), 54% have unmutated IgHV, 17% have deletion 17p or TP53 mutation, 4% have deletion 11q, and 54% have deletion 13q.

The patients received no prior therapies.

Results

The trial is currently ongoing.

The 24 patients enrolled as of early November have been on therapy a median of 7.7 months, for a median follow-up time of 14.7 months.

“What we began to notice after enrolling just a few subjects on the trial was that severe hepatotoxicity was occurring shortly after initiating idelalisib,” Dr Lampson said.

In the first 2 months of therapy, 52% of patients developed transaminitis, and 13% developed colitis or diarrhea, all grade 3 or higher. Thirteen percent developed pneumonitis of any grade.

Younger age is a risk factor for early hepatotoxicity, Dr Lampson said, with a significance of P=0.02. All subjects age 65 or younger (n=7) required systemic steroids to treat their toxicities.

Hepatotoxicity developed in a median of 28 days, he said, “and the hepatotoxicity is typically occurring before the first dose of ofatumumab is administered at week 8, suggesting that idelalisib alone is the cause of the hepatotoxicity.”

Dr Lampson noted that toxicities resolved rapidly with steroids.

“I do want to point out that all subjects evaluable for a response have had a response,” he added. “Additionally, in all subjects where treatment has been discontinued, the discontinuation was due to adverse events rather than disease progression.”

Twelve patients with grade 2 or higher transaminitis were re-challenged with idelalisib after holding the drug for toxicity.

Five patients were re-challenged while off steroids, and 4 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days. Seven patients were re-challenged while on steroids, and 2 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days.

“In general, our experience has been, if idelalisib is resumed while the subject remains on steroids, the drug is more likely to be tolerated and the subject can eventually be taken off steroids,” Dr Lampson said.

Comparison with earlier studies

The investigators compared the frequency of toxicity in their trial to earlier studies of idelalisib (Brown, Blood 2014; Coutre, EHA 2015, abstr P588; O’Brien, Blood 2015).

They found that grade 3 or higher transaminitis (52%) and any grade pneumonitis (13%) were higher in their trial than in the 3 other trials.

Colitis/diarrhea was about the same in 2 of the 3 other trials. But in the paper by O’Brien et al, 42% of patients experienced grade 3 or greater colitis/diarrhea.

The lower rate of colitis in the present trial may be due to the shorter follow-up, Dr Lampson said, as colitis is a late adverse event.

The O’Brien trial was also an upfront study, so patients had no prior therapies. The investigators observed that toxicities appeared to be more common in less heavily pretreated patients.

“As the median number of prior therapies decreases,” Dr Lampson said, “the frequency of adverse events increases.”

He noted that, in the O’Brien trial, idelalisib was started simultaneously with the other drugs, perhaps accounting for its somewhat lower rate (21%) of grade 3 or higher transaminitis.

Additionally, the patient population in the O’Brien trial was older than the population in the current trial, which could account for the higher rate of transaminitis, as younger age is a risk factor.

Decrease in regulatory T cells

Investigators noted a decrease in regulatory T cells while patients were on therapy. Eleven of 15 patients (73%) with matched samples had a significant (P<0.05) decrease in the percentage of T cells over time.

This, they say, could provide a possible explanation for the development of early hepatotoxicity.

The trial is investigator-initiated and funded by Gilead Sciences. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differs from the abstract.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators have observed early fulminant hepatotoxicity in a subset of primarily younger chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with idelalisib monotherapy in the frontline setting.

In a phase 2 study of idelalisib plus ofatumumab, 52% of the 24 patients enrolled experienced grade 3 or higher hepatotoxicity shortly after idelalisib was started.

The investigators say this may occur because a proportion of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood decreases while patients are on idelalisib. The team believes this early hepatotoxicity is immune-mediated.

Benjamin Lampson, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, described these surprising findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 497.*

Study design and patient demographics

Patients received 150 mg of idelalisib twice daily as monotherapy on days 1 through 56. They then received combination therapy with idelalisib plus ofatumumab for 8 weekly infusions, followed by 4 monthly infusions through day 225, and then idelalisib monotherapy indefinitely.

The primary endpoint of overall response rate was assessed 2 months after the completion of combination therapy.

“This dosing strategy is slightly different than what has been previously used in trials combining these particular drugs,” Dr Lampson said. “Specifically, previously reported trials started these agents simultaneously without a lead-in period of monotherapy.”

The investigators monitored the patients weekly for toxicities during the 2-month monotherapy lead-in period.

Three-quarters of the patients are male. Their median age is 67.4 years (range, 57.6–84.9), 54% have unmutated IgHV, 17% have deletion 17p or TP53 mutation, 4% have deletion 11q, and 54% have deletion 13q.

The patients received no prior therapies.

Results

The trial is currently ongoing.

The 24 patients enrolled as of early November have been on therapy a median of 7.7 months, for a median follow-up time of 14.7 months.

“What we began to notice after enrolling just a few subjects on the trial was that severe hepatotoxicity was occurring shortly after initiating idelalisib,” Dr Lampson said.

In the first 2 months of therapy, 52% of patients developed transaminitis, and 13% developed colitis or diarrhea, all grade 3 or higher. Thirteen percent developed pneumonitis of any grade.

Younger age is a risk factor for early hepatotoxicity, Dr Lampson said, with a significance of P=0.02. All subjects age 65 or younger (n=7) required systemic steroids to treat their toxicities.

Hepatotoxicity developed in a median of 28 days, he said, “and the hepatotoxicity is typically occurring before the first dose of ofatumumab is administered at week 8, suggesting that idelalisib alone is the cause of the hepatotoxicity.”

Dr Lampson noted that toxicities resolved rapidly with steroids.

“I do want to point out that all subjects evaluable for a response have had a response,” he added. “Additionally, in all subjects where treatment has been discontinued, the discontinuation was due to adverse events rather than disease progression.”

Twelve patients with grade 2 or higher transaminitis were re-challenged with idelalisib after holding the drug for toxicity.

Five patients were re-challenged while off steroids, and 4 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days. Seven patients were re-challenged while on steroids, and 2 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days.

“In general, our experience has been, if idelalisib is resumed while the subject remains on steroids, the drug is more likely to be tolerated and the subject can eventually be taken off steroids,” Dr Lampson said.

Comparison with earlier studies

The investigators compared the frequency of toxicity in their trial to earlier studies of idelalisib (Brown, Blood 2014; Coutre, EHA 2015, abstr P588; O’Brien, Blood 2015).

They found that grade 3 or higher transaminitis (52%) and any grade pneumonitis (13%) were higher in their trial than in the 3 other trials.

Colitis/diarrhea was about the same in 2 of the 3 other trials. But in the paper by O’Brien et al, 42% of patients experienced grade 3 or greater colitis/diarrhea.

The lower rate of colitis in the present trial may be due to the shorter follow-up, Dr Lampson said, as colitis is a late adverse event.

The O’Brien trial was also an upfront study, so patients had no prior therapies. The investigators observed that toxicities appeared to be more common in less heavily pretreated patients.

“As the median number of prior therapies decreases,” Dr Lampson said, “the frequency of adverse events increases.”

He noted that, in the O’Brien trial, idelalisib was started simultaneously with the other drugs, perhaps accounting for its somewhat lower rate (21%) of grade 3 or higher transaminitis.

Additionally, the patient population in the O’Brien trial was older than the population in the current trial, which could account for the higher rate of transaminitis, as younger age is a risk factor.

Decrease in regulatory T cells

Investigators noted a decrease in regulatory T cells while patients were on therapy. Eleven of 15 patients (73%) with matched samples had a significant (P<0.05) decrease in the percentage of T cells over time.

This, they say, could provide a possible explanation for the development of early hepatotoxicity.

The trial is investigator-initiated and funded by Gilead Sciences. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differs from the abstract.

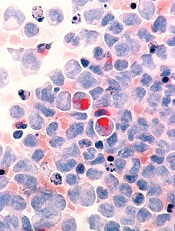

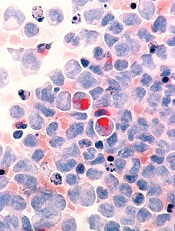

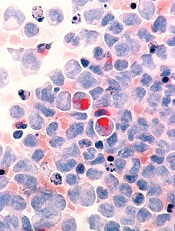

Genes can stop onset of AML, study suggests

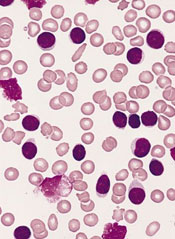

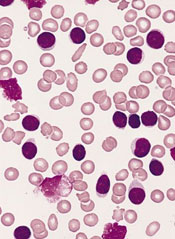

Image by Lance Liotta

Two genes can stop the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The work suggests that Hif-1α and Hif-2α work together to stop the formation of leukemic stem cells, and blocking either Hif-2α or both genes

accelerates AML development.

Investigators said these findings are surprising because previous research suggested that blocking Hif-1α or Hif-2α might stop AML progression.

But their study suggests that therapies designed to block these genes might worsen AML or at least have no impact on the disease.

Conversely, designing new therapies that promote the activity of Hif-1α and Hif-2α could help treat AML or stop relapse after chemotherapy.

“Our discovery that Hif-1α and Hif-2α molecules act together to stop leukemia development is a major milestone in our efforts to combat leukemia,” said study author Kamil R. Kranc, DPhil, of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

“We now intend to harness this knowledge to develop curative therapies that eliminate leukemic stem cells, which are the underlying cause of AML.” ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

Two genes can stop the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The work suggests that Hif-1α and Hif-2α work together to stop the formation of leukemic stem cells, and blocking either Hif-2α or both genes

accelerates AML development.

Investigators said these findings are surprising because previous research suggested that blocking Hif-1α or Hif-2α might stop AML progression.

But their study suggests that therapies designed to block these genes might worsen AML or at least have no impact on the disease.

Conversely, designing new therapies that promote the activity of Hif-1α and Hif-2α could help treat AML or stop relapse after chemotherapy.

“Our discovery that Hif-1α and Hif-2α molecules act together to stop leukemia development is a major milestone in our efforts to combat leukemia,” said study author Kamil R. Kranc, DPhil, of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

“We now intend to harness this knowledge to develop curative therapies that eliminate leukemic stem cells, which are the underlying cause of AML.” ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

Two genes can stop the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The work suggests that Hif-1α and Hif-2α work together to stop the formation of leukemic stem cells, and blocking either Hif-2α or both genes

accelerates AML development.

Investigators said these findings are surprising because previous research suggested that blocking Hif-1α or Hif-2α might stop AML progression.

But their study suggests that therapies designed to block these genes might worsen AML or at least have no impact on the disease.

Conversely, designing new therapies that promote the activity of Hif-1α and Hif-2α could help treat AML or stop relapse after chemotherapy.

“Our discovery that Hif-1α and Hif-2α molecules act together to stop leukemia development is a major milestone in our efforts to combat leukemia,” said study author Kamil R. Kranc, DPhil, of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

“We now intend to harness this knowledge to develop curative therapies that eliminate leukemic stem cells, which are the underlying cause of AML.” ![]()

Group finds inconsistencies in genome sequencing procedures

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Researchers say they have identified substantial differences in the procedures and quality of cancer genome sequencing between sequencing centers.

And this led to dramatic discrepancies in the number and types of somatic mutations detected when using the same cancer genome sequences for analysis.

The group’s study involved 83 researchers from 78 institutions participating in the International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC).

The ICGC is an international effort to establish a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in 50 different tumor types and/or subtypes that are thought to be of clinical and societal importance across the globe.

The consortium is characterizing more than 25,000 cancer genomes and carrying out 78 projects supported by different national and international funding agencies.

For the current project, which was published in Nature Communications, researchers studied a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and a patient with medulloblastoma.

The team analyzed the entire tumor genome of each patient and compared it to the normal genome of the same patient to decipher the molecular causes for these cancers.

The researchers said they saw “widely varying mutation call rates and low concordance among analysis pipelines.”

So they established a reference mutation dataset to assess analytical procedures. They said this “gold-set” reference database has helped the ICGC community improve procedures for identifying more true somatic mutations in cancer genomes and making fewer false-positive calls.

“The findings of our study have far-reaching implications for cancer genome analysis,” said Ivo Gut, of Centro Nacional de Analisis Genómico in Barcelona, Spain.

“We have found many inconsistencies in both the sequencing of cancer genomes and the data analysis at different sites. We are making our findings available to the scientific and diagnostic community so that they can improve their systems and generate more standardized and consistent results.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Researchers say they have identified substantial differences in the procedures and quality of cancer genome sequencing between sequencing centers.

And this led to dramatic discrepancies in the number and types of somatic mutations detected when using the same cancer genome sequences for analysis.

The group’s study involved 83 researchers from 78 institutions participating in the International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC).

The ICGC is an international effort to establish a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in 50 different tumor types and/or subtypes that are thought to be of clinical and societal importance across the globe.

The consortium is characterizing more than 25,000 cancer genomes and carrying out 78 projects supported by different national and international funding agencies.

For the current project, which was published in Nature Communications, researchers studied a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and a patient with medulloblastoma.

The team analyzed the entire tumor genome of each patient and compared it to the normal genome of the same patient to decipher the molecular causes for these cancers.

The researchers said they saw “widely varying mutation call rates and low concordance among analysis pipelines.”

So they established a reference mutation dataset to assess analytical procedures. They said this “gold-set” reference database has helped the ICGC community improve procedures for identifying more true somatic mutations in cancer genomes and making fewer false-positive calls.

“The findings of our study have far-reaching implications for cancer genome analysis,” said Ivo Gut, of Centro Nacional de Analisis Genómico in Barcelona, Spain.

“We have found many inconsistencies in both the sequencing of cancer genomes and the data analysis at different sites. We are making our findings available to the scientific and diagnostic community so that they can improve their systems and generate more standardized and consistent results.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Researchers say they have identified substantial differences in the procedures and quality of cancer genome sequencing between sequencing centers.

And this led to dramatic discrepancies in the number and types of somatic mutations detected when using the same cancer genome sequences for analysis.

The group’s study involved 83 researchers from 78 institutions participating in the International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC).

The ICGC is an international effort to establish a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in 50 different tumor types and/or subtypes that are thought to be of clinical and societal importance across the globe.

The consortium is characterizing more than 25,000 cancer genomes and carrying out 78 projects supported by different national and international funding agencies.

For the current project, which was published in Nature Communications, researchers studied a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and a patient with medulloblastoma.

The team analyzed the entire tumor genome of each patient and compared it to the normal genome of the same patient to decipher the molecular causes for these cancers.

The researchers said they saw “widely varying mutation call rates and low concordance among analysis pipelines.”

So they established a reference mutation dataset to assess analytical procedures. They said this “gold-set” reference database has helped the ICGC community improve procedures for identifying more true somatic mutations in cancer genomes and making fewer false-positive calls.

“The findings of our study have far-reaching implications for cancer genome analysis,” said Ivo Gut, of Centro Nacional de Analisis Genómico in Barcelona, Spain.

“We have found many inconsistencies in both the sequencing of cancer genomes and the data analysis at different sites. We are making our findings available to the scientific and diagnostic community so that they can improve their systems and generate more standardized and consistent results.” ![]()

Oncology 2015: new therapies and new transitions toward value-based cancer care

The past year has been an exciting one for new oncology and hematology drug approvals and the continued evolution of our oncology delivery system toward high quality and value. In all, at press time in mid-November, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved or granted expanded indications for 24 drugs, compared with 19 in the 2 preceding years. Of those 24 approvals, 7 were accelerated and 6 were expanded approvals, and 3 alone were for the immunotherapeutic drug, nivolumab – 2 for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 1 for metastatic melanoma.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

The past year has been an exciting one for new oncology and hematology drug approvals and the continued evolution of our oncology delivery system toward high quality and value. In all, at press time in mid-November, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved or granted expanded indications for 24 drugs, compared with 19 in the 2 preceding years. Of those 24 approvals, 7 were accelerated and 6 were expanded approvals, and 3 alone were for the immunotherapeutic drug, nivolumab – 2 for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 1 for metastatic melanoma.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

The past year has been an exciting one for new oncology and hematology drug approvals and the continued evolution of our oncology delivery system toward high quality and value. In all, at press time in mid-November, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved or granted expanded indications for 24 drugs, compared with 19 in the 2 preceding years. Of those 24 approvals, 7 were accelerated and 6 were expanded approvals, and 3 alone were for the immunotherapeutic drug, nivolumab – 2 for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 1 for metastatic melanoma.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Combination offers ‘important new option’ for CLL, team says

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Idelalisib, the first-in-class PI3Kδ inhibitor, combined with bendamustine and rituximab (BR) for relapsed/refractory chronic

lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) offers “an important new option over the standard of care,” according to Andrew Zelenetz, MD, a member of the

international research team that conducted the phase 3 study of this combination.

Patients who received idelalisib plus BR experienced a much longer progression-free survival (PFS) than those who received BR alone, 23.1

months versus 11.1 months, respectively.

“And the benefit was seen across risk groups,” Dr Zelenetz said.

He pointed out that the trial was stopped early in October because of the “overwhelming benefit” of idelalisib compared to the conventional therapy arm.

Dr Zelenetz, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York, presented the findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as LBA-5.

Idelalisib had already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsed/refractory CLL.

“Many people refer to this [idelalisib] as a B-cell receptor drug,” Dr Zelenetz said, “but it is more than that. It is involved in signaling of very key pathways in cell survival and migration.”

The investigators hoped that by combining idelalisib with BR, they would be able to improve PFS and maintain tolerable toxicity. So they conducted Study 115 to find out.

Study 115 design and population

Study 115 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study.

The idelalisib arm consisted of 207 patients randomized to receive bendamustine at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks for 6 cycles, rituximab at 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 and 500 mg/m2 cycles 2 through 6, and idelalisib at 150 mg twice daily until progression.

The BR arm consisted of 209 patients randomized to the same BR regimen plus placebo twice daily until progression.

Investigators stratified patients according to 17p deletion and/or TP52 mutation, IGHV mutation status, and refractory versus relapsed disease.

The primary endpoint was PFS and the secondary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR), nodal response, overall survival (OS), and complete response (CR) rate.

Patients had to have disease progression within less than 36 months from their last therapy, measurable disease, and no history of CLL transformation. They could not have progressed in less than 6 months from their last bendamustine treatment and they could not have had any prior inhibitors of BTK, PI3Kδ, or SYK.

Patient disposition and demographics

One hundred fifteen patients (56%) in the idelalisib arm are still on study, and 52% are on treatment. In the BR arm, 63 patients (30%) are still on study, and 29% are on treatment.

Patient characteristics were well balanced between the arms. Most patients (76%) were male, 58% were younger than 65 years and 42% were 65 or older. About half were Rai stage III/IV and the median number of prior regimens was 2 (range, 1–13).

The most common prior regimens in both arms were fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab, fludarabine/cyclophosphamide, and chlorambucil. Fifteen percent of patients in the idelalisib arm and 8% in the BR arm had prior BR.

A third of patients in each arm had either 17p deletion or TP53 mutation, and two-thirds had neither. Most patients did not have IGHV mutation—84% in the idelalisib group and 83% in the BR group.

Thirty-one percent of the idelalisib-treated patients and 29% of the placebo patients had refractory disease, and 69% and 71%, respectively, had relapsed disease.

Efficacy

Median PFS, as assessed by independent review committee, “was highly statistically significant,” Dr Zelenetz said, at 23.1 months for idelalisib and 11.1 for BR (P<0.0001).

In addition, all subgroups analyzed favored idelalisib—refractory or relapsed disease, mutation status, cytogenetics, gender, age, and race.

Patients with neither deletion 17p nor TP53 had a hazard ratio of 0.22 favoring the idelalisib group, and patients with either one or the other of those mutations had a hazard ratio of 0.50 favoring idelalisib.

ORR was 68% and 45% for idelalisib and placebo, respectively, with 5% in the idelalisib arm and none in the placebo arm achieving a CR.

Dr Zelenetz pointed out that the CR rate was low largely due to missing confirmatory biopsies.

Ninety-six percent of patients in the idelalisib arm experienced 50% or more reduction in lymph nodes, compared with 61% in the placebo arm.

Patients in the idelalisib arm also experienced a significant improvement in OS of P=0.008 when stratified and P=0.023 when unstratified. Median OS has not been reached in either arm.

There was no difference in survival benefit in patients with refractory disease.

Safety

All patients in the idelalisib arm and 97% in the BR arm experienced an adverse event (AE), with 93% and 76% grade 3 or higher in the idelalisib and BR arms, respectively.

Serious AEs occurred in 66% of idelalisib-treated patients and 44% of placebo patients.

Fifty-four patients (26%) in the idelalisib arm discontinued the study drug due to AEs, and 22 (11%) required a study drug dose reduction. This was compared with 28 patients (13%) discontinuing and 13 patients requiring dose reductions in the placebo arm.

The most frequent AE occurring in more than 10% of patients was neutropenia. Grade 3 or higher neutropenia occurred in 60% of idelalisib patients and 46% of placebo patients.

Most AEs were higher in the idelalisib arm compared with the BR arm, including grade 3 or higher events, such as febrile neutropenia (20%, 6%), anemia (15%, 12%), thrombocytopenia (13%, 12%), pneumonia (11%, 6%), ALT increase (11%, <1%), pyrexia (7%, 3%), diarrhea (7%, 2%), and rash (3%, 0), among others.

Serious AEs occurring in more than 2% of patients were also higher in the idelalisib arm than the BR arm, and included febrile neutropenia (18%, 5%), pneumonia (14%, 6%), pyrexia (12%, 6%), neutropenia (4%, 1%), sepsis (4%, 1%), anemia (2%, 2%), lower respiratory tract infection (2%, 2%), diarrhea (4%, <1%), and neutropenic sepsis (1%, 3%).

The remainder of the serious AEs—urinary tract infection, bronchitis, septic shock, and squamous cell carcinoma—occurred in 2% or fewer patients in either arm.

Dr Zelenetz pointed out that the safety profile is consistent with previously reported studies.

Gilead Sciences developed idelalisib and funded Study 115. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ slightly from data presented at the meeting.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Idelalisib, the first-in-class PI3Kδ inhibitor, combined with bendamustine and rituximab (BR) for relapsed/refractory chronic

lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) offers “an important new option over the standard of care,” according to Andrew Zelenetz, MD, a member of the

international research team that conducted the phase 3 study of this combination.

Patients who received idelalisib plus BR experienced a much longer progression-free survival (PFS) than those who received BR alone, 23.1

months versus 11.1 months, respectively.

“And the benefit was seen across risk groups,” Dr Zelenetz said.

He pointed out that the trial was stopped early in October because of the “overwhelming benefit” of idelalisib compared to the conventional therapy arm.

Dr Zelenetz, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York, presented the findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as LBA-5.

Idelalisib had already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsed/refractory CLL.

“Many people refer to this [idelalisib] as a B-cell receptor drug,” Dr Zelenetz said, “but it is more than that. It is involved in signaling of very key pathways in cell survival and migration.”

The investigators hoped that by combining idelalisib with BR, they would be able to improve PFS and maintain tolerable toxicity. So they conducted Study 115 to find out.

Study 115 design and population

Study 115 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study.

The idelalisib arm consisted of 207 patients randomized to receive bendamustine at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks for 6 cycles, rituximab at 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 and 500 mg/m2 cycles 2 through 6, and idelalisib at 150 mg twice daily until progression.

The BR arm consisted of 209 patients randomized to the same BR regimen plus placebo twice daily until progression.

Investigators stratified patients according to 17p deletion and/or TP52 mutation, IGHV mutation status, and refractory versus relapsed disease.

The primary endpoint was PFS and the secondary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR), nodal response, overall survival (OS), and complete response (CR) rate.

Patients had to have disease progression within less than 36 months from their last therapy, measurable disease, and no history of CLL transformation. They could not have progressed in less than 6 months from their last bendamustine treatment and they could not have had any prior inhibitors of BTK, PI3Kδ, or SYK.

Patient disposition and demographics

One hundred fifteen patients (56%) in the idelalisib arm are still on study, and 52% are on treatment. In the BR arm, 63 patients (30%) are still on study, and 29% are on treatment.

Patient characteristics were well balanced between the arms. Most patients (76%) were male, 58% were younger than 65 years and 42% were 65 or older. About half were Rai stage III/IV and the median number of prior regimens was 2 (range, 1–13).

The most common prior regimens in both arms were fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab, fludarabine/cyclophosphamide, and chlorambucil. Fifteen percent of patients in the idelalisib arm and 8% in the BR arm had prior BR.

A third of patients in each arm had either 17p deletion or TP53 mutation, and two-thirds had neither. Most patients did not have IGHV mutation—84% in the idelalisib group and 83% in the BR group.

Thirty-one percent of the idelalisib-treated patients and 29% of the placebo patients had refractory disease, and 69% and 71%, respectively, had relapsed disease.

Efficacy

Median PFS, as assessed by independent review committee, “was highly statistically significant,” Dr Zelenetz said, at 23.1 months for idelalisib and 11.1 for BR (P<0.0001).

In addition, all subgroups analyzed favored idelalisib—refractory or relapsed disease, mutation status, cytogenetics, gender, age, and race.

Patients with neither deletion 17p nor TP53 had a hazard ratio of 0.22 favoring the idelalisib group, and patients with either one or the other of those mutations had a hazard ratio of 0.50 favoring idelalisib.

ORR was 68% and 45% for idelalisib and placebo, respectively, with 5% in the idelalisib arm and none in the placebo arm achieving a CR.

Dr Zelenetz pointed out that the CR rate was low largely due to missing confirmatory biopsies.

Ninety-six percent of patients in the idelalisib arm experienced 50% or more reduction in lymph nodes, compared with 61% in the placebo arm.

Patients in the idelalisib arm also experienced a significant improvement in OS of P=0.008 when stratified and P=0.023 when unstratified. Median OS has not been reached in either arm.

There was no difference in survival benefit in patients with refractory disease.

Safety

All patients in the idelalisib arm and 97% in the BR arm experienced an adverse event (AE), with 93% and 76% grade 3 or higher in the idelalisib and BR arms, respectively.

Serious AEs occurred in 66% of idelalisib-treated patients and 44% of placebo patients.

Fifty-four patients (26%) in the idelalisib arm discontinued the study drug due to AEs, and 22 (11%) required a study drug dose reduction. This was compared with 28 patients (13%) discontinuing and 13 patients requiring dose reductions in the placebo arm.

The most frequent AE occurring in more than 10% of patients was neutropenia. Grade 3 or higher neutropenia occurred in 60% of idelalisib patients and 46% of placebo patients.

Most AEs were higher in the idelalisib arm compared with the BR arm, including grade 3 or higher events, such as febrile neutropenia (20%, 6%), anemia (15%, 12%), thrombocytopenia (13%, 12%), pneumonia (11%, 6%), ALT increase (11%, <1%), pyrexia (7%, 3%), diarrhea (7%, 2%), and rash (3%, 0), among others.

Serious AEs occurring in more than 2% of patients were also higher in the idelalisib arm than the BR arm, and included febrile neutropenia (18%, 5%), pneumonia (14%, 6%), pyrexia (12%, 6%), neutropenia (4%, 1%), sepsis (4%, 1%), anemia (2%, 2%), lower respiratory tract infection (2%, 2%), diarrhea (4%, <1%), and neutropenic sepsis (1%, 3%).

The remainder of the serious AEs—urinary tract infection, bronchitis, septic shock, and squamous cell carcinoma—occurred in 2% or fewer patients in either arm.

Dr Zelenetz pointed out that the safety profile is consistent with previously reported studies.

Gilead Sciences developed idelalisib and funded Study 115. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ slightly from data presented at the meeting.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Idelalisib, the first-in-class PI3Kδ inhibitor, combined with bendamustine and rituximab (BR) for relapsed/refractory chronic

lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) offers “an important new option over the standard of care,” according to Andrew Zelenetz, MD, a member of the

international research team that conducted the phase 3 study of this combination.

Patients who received idelalisib plus BR experienced a much longer progression-free survival (PFS) than those who received BR alone, 23.1

months versus 11.1 months, respectively.

“And the benefit was seen across risk groups,” Dr Zelenetz said.

He pointed out that the trial was stopped early in October because of the “overwhelming benefit” of idelalisib compared to the conventional therapy arm.

Dr Zelenetz, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York, presented the findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as LBA-5.

Idelalisib had already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsed/refractory CLL.

“Many people refer to this [idelalisib] as a B-cell receptor drug,” Dr Zelenetz said, “but it is more than that. It is involved in signaling of very key pathways in cell survival and migration.”

The investigators hoped that by combining idelalisib with BR, they would be able to improve PFS and maintain tolerable toxicity. So they conducted Study 115 to find out.

Study 115 design and population

Study 115 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study.

The idelalisib arm consisted of 207 patients randomized to receive bendamustine at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks for 6 cycles, rituximab at 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 and 500 mg/m2 cycles 2 through 6, and idelalisib at 150 mg twice daily until progression.

The BR arm consisted of 209 patients randomized to the same BR regimen plus placebo twice daily until progression.

Investigators stratified patients according to 17p deletion and/or TP52 mutation, IGHV mutation status, and refractory versus relapsed disease.

The primary endpoint was PFS and the secondary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR), nodal response, overall survival (OS), and complete response (CR) rate.

Patients had to have disease progression within less than 36 months from their last therapy, measurable disease, and no history of CLL transformation. They could not have progressed in less than 6 months from their last bendamustine treatment and they could not have had any prior inhibitors of BTK, PI3Kδ, or SYK.

Patient disposition and demographics

One hundred fifteen patients (56%) in the idelalisib arm are still on study, and 52% are on treatment. In the BR arm, 63 patients (30%) are still on study, and 29% are on treatment.

Patient characteristics were well balanced between the arms. Most patients (76%) were male, 58% were younger than 65 years and 42% were 65 or older. About half were Rai stage III/IV and the median number of prior regimens was 2 (range, 1–13).

The most common prior regimens in both arms were fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab, fludarabine/cyclophosphamide, and chlorambucil. Fifteen percent of patients in the idelalisib arm and 8% in the BR arm had prior BR.

A third of patients in each arm had either 17p deletion or TP53 mutation, and two-thirds had neither. Most patients did not have IGHV mutation—84% in the idelalisib group and 83% in the BR group.

Thirty-one percent of the idelalisib-treated patients and 29% of the placebo patients had refractory disease, and 69% and 71%, respectively, had relapsed disease.

Efficacy

Median PFS, as assessed by independent review committee, “was highly statistically significant,” Dr Zelenetz said, at 23.1 months for idelalisib and 11.1 for BR (P<0.0001).

In addition, all subgroups analyzed favored idelalisib—refractory or relapsed disease, mutation status, cytogenetics, gender, age, and race.

Patients with neither deletion 17p nor TP53 had a hazard ratio of 0.22 favoring the idelalisib group, and patients with either one or the other of those mutations had a hazard ratio of 0.50 favoring idelalisib.

ORR was 68% and 45% for idelalisib and placebo, respectively, with 5% in the idelalisib arm and none in the placebo arm achieving a CR.

Dr Zelenetz pointed out that the CR rate was low largely due to missing confirmatory biopsies.

Ninety-six percent of patients in the idelalisib arm experienced 50% or more reduction in lymph nodes, compared with 61% in the placebo arm.

Patients in the idelalisib arm also experienced a significant improvement in OS of P=0.008 when stratified and P=0.023 when unstratified. Median OS has not been reached in either arm.

There was no difference in survival benefit in patients with refractory disease.

Safety

All patients in the idelalisib arm and 97% in the BR arm experienced an adverse event (AE), with 93% and 76% grade 3 or higher in the idelalisib and BR arms, respectively.

Serious AEs occurred in 66% of idelalisib-treated patients and 44% of placebo patients.

Fifty-four patients (26%) in the idelalisib arm discontinued the study drug due to AEs, and 22 (11%) required a study drug dose reduction. This was compared with 28 patients (13%) discontinuing and 13 patients requiring dose reductions in the placebo arm.

The most frequent AE occurring in more than 10% of patients was neutropenia. Grade 3 or higher neutropenia occurred in 60% of idelalisib patients and 46% of placebo patients.

Most AEs were higher in the idelalisib arm compared with the BR arm, including grade 3 or higher events, such as febrile neutropenia (20%, 6%), anemia (15%, 12%), thrombocytopenia (13%, 12%), pneumonia (11%, 6%), ALT increase (11%, <1%), pyrexia (7%, 3%), diarrhea (7%, 2%), and rash (3%, 0), among others.

Serious AEs occurring in more than 2% of patients were also higher in the idelalisib arm than the BR arm, and included febrile neutropenia (18%, 5%), pneumonia (14%, 6%), pyrexia (12%, 6%), neutropenia (4%, 1%), sepsis (4%, 1%), anemia (2%, 2%), lower respiratory tract infection (2%, 2%), diarrhea (4%, <1%), and neutropenic sepsis (1%, 3%).

The remainder of the serious AEs—urinary tract infection, bronchitis, septic shock, and squamous cell carcinoma—occurred in 2% or fewer patients in either arm.

Dr Zelenetz pointed out that the safety profile is consistent with previously reported studies.

Gilead Sciences developed idelalisib and funded Study 115. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ slightly from data presented at the meeting.

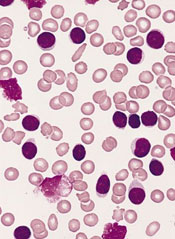

Group recommends adding rituximab to ALL therapy

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators from the Group for Research on Adult Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAALL) recommend integrating rituximab into the treatment of adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) based on results of the GRAALL-R 2005 study.

Patients who received rituximab as part of their therapy had a median event-free survival (EFS) at 2 years of 65%, compared to 52% for patients who did not receive rituximab. After censoring for stem cell transplant in first complete remission, the benefit was even greater.

Sébastien Maury, MD, PhD, of Hȏpital Hénri Mondor in Creteil, France, presented the results during the plenary session of the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 1.

Dr Maury said GRAALL-R 2005 is the first phase 3, randomized study to evaluate the role of rituximab in the treatment of B-cell precursor (BCP) ALL.

Only one previous study, he said, suggested a potential benefit of adding rituximab compared to historic controls of chemotherapy alone.

He explained that, because the CD20 antigen is expressed at diagnosis in 30% to 40% of patients with BCP-ALL, investigators undertook to evaluate whether adding the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab to the ALL treatment regimen could be beneficial for newly diagnosed Ph-negative BCP-ALL patients.

Study design & population

Investigators randomized 105 patients to receive the pediatric-inspired GRAALL protocol plus rituximab and 104 patients to the same regimen without rituximab.

Patients had to have 20% or more CD20-positive leukemic blasts.

Patients in the rituximab arm received 375 mg/m2 during induction on days 1 and 7, during salvage reinduction (if needed) on days 1 and 7, during consolidation blocks (6 infusions), during late intensification on days 1 and 7, and during the first year of maintenance (6 infusions), for a total of 16 to 18 infusions.

“In this trial, allogeneic transplantation was offered in first remission to high-risk patients who were those patients with at least one of these baseline or response-related criteria,” Dr Maury said.

Investigators defined high-risk at baseline as having a white blood cell count of 30 x 109/L or higher, CNS involvement, CD10-negative disease, or unfavorable cytogenetics.

And response-related criteria for high-risk disease included poor peripheral blast clearance after the 1-week steroid pre-phase, poor bone marrow blast clearance after the first week of chemotherapy, or no hematologic complete response after the first induction course.

Patient characteristics were well balanced between the arms, with a median age for the entire group of 40.2 years. Rituximab-treated patients had 61% CD20-positive blasts, and the no-rituximab arm had 69%.

More patients in the rituximab arm had a better ECOG performance status, although the difference was not significant. Thirteen percent were assessed as being grade 2 or higher in the rituximab arm, compared with 18% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.06).

“The proportion of high-risk patients was comparable in both arms,” Dr Maury said, “representing around two-thirds of the study population.”

In the rituximab arm, 70% were considered high-risk, compared with 64% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.46).

“However, despite this,” he said, “a significantly higher proportion of patients received allo transplant at first remission in the rituximab arm, 34% versus 20%. And since this was not explained by a different proportion of high-risk patients, this was probably due to differences in donor availability.”

Dr Maury noted that compliance to treatment was “quite good.”

Efficacy

The median follow-up was 30 months, and the primary endpoint was EFS.

The EFS rate for rituximab-treated patients at 2 years was 65%, compared with 52% for the non-rituximab patients (hazard ratio=0.66, P=0.038).

EFS was also significantly better with rituximab when patients were censored at allogeneic transplant, with a hazard ratio of 0.59 and a significance of 0.021.

However, there were no significant differences in early complete response rates, minimal residual disease (MRD) after induction, and MRD after consolidation.

“[O]nly 40% of patients could be centrally analyzed [for MRD],” Dr Maury explained, “which may be the reason why we could not detect any impact of rituximab on MRD.”

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 18% in the rituximab arm and 32% in the no-rituximab arm (hazard ratio=0.52, P=0.017). And after censoring for stem cell transplant in first complete remission, the hazard ratio was 0.49 in favor of rituximab (P=0.018).

Overall survival (OS) was not significantly different between the arms. Rituximab-treated patients had an OS rate of 71%, compared with 64% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.095).

“However, this difference became significant when censoring patients at time of allo-transplant,” Dr Maury said.

There was a 12% cumulative incidence of death in first complete remission at 2 years in each arm.

Investigators performed multivariate analysis and found that treatment with rituximab (P=0.020), age (P=0.022), white blood cell count of 30 x 109/L or higher (P=0.005), and CNS involvement all significantly impacted EFS.

When they introduced stem cell transplant in first remission as a covariable, the same factors remained significant. Allogeneic stem cell transplant in first remission did not make a significant difference on EFS (P=0.62).

Safety

One hundred twenty-four patients reported 246 severe adverse events, the most frequent of which was infection—71 in the rituximab arm and 55 in the no-rituximab arm, a difference that was not significant (P=0.16).

Severe allergic events were significantly different between the arms, with 2 severe allergic events reported in the rituximab arm and 14 in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.002). Of these 16 events, all but one were due to asparaginase.

“We believe that this may reflect the protective effect of rituximab that might inhibit B-cell protection of antibodies against asparaginase,” Dr Maury said, although the investigators did not actually measure the antibodies.

Severe lab abnormalities, neurologic and pulmonary events, coagulopathy, cardiologic and gastrointestinal events were not significantly different between the arms.

Dr Maury emphasized that the addition of rituximab to standard intensive chemotherapy is well tolerated, significantly improves EFS, and prolongs OS in patients not receiving allogeneic transplant in first remission.

While the optimal dose schedule of rituximab still remains to be determined, the GRAALL investigators believe that “the addition of rituximab should be the new standard of care for these patients,” Dr Maury declared. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators from the Group for Research on Adult Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAALL) recommend integrating rituximab into the treatment of adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) based on results of the GRAALL-R 2005 study.

Patients who received rituximab as part of their therapy had a median event-free survival (EFS) at 2 years of 65%, compared to 52% for patients who did not receive rituximab. After censoring for stem cell transplant in first complete remission, the benefit was even greater.

Sébastien Maury, MD, PhD, of Hȏpital Hénri Mondor in Creteil, France, presented the results during the plenary session of the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 1.

Dr Maury said GRAALL-R 2005 is the first phase 3, randomized study to evaluate the role of rituximab in the treatment of B-cell precursor (BCP) ALL.

Only one previous study, he said, suggested a potential benefit of adding rituximab compared to historic controls of chemotherapy alone.

He explained that, because the CD20 antigen is expressed at diagnosis in 30% to 40% of patients with BCP-ALL, investigators undertook to evaluate whether adding the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab to the ALL treatment regimen could be beneficial for newly diagnosed Ph-negative BCP-ALL patients.

Study design & population

Investigators randomized 105 patients to receive the pediatric-inspired GRAALL protocol plus rituximab and 104 patients to the same regimen without rituximab.

Patients had to have 20% or more CD20-positive leukemic blasts.

Patients in the rituximab arm received 375 mg/m2 during induction on days 1 and 7, during salvage reinduction (if needed) on days 1 and 7, during consolidation blocks (6 infusions), during late intensification on days 1 and 7, and during the first year of maintenance (6 infusions), for a total of 16 to 18 infusions.

“In this trial, allogeneic transplantation was offered in first remission to high-risk patients who were those patients with at least one of these baseline or response-related criteria,” Dr Maury said.

Investigators defined high-risk at baseline as having a white blood cell count of 30 x 109/L or higher, CNS involvement, CD10-negative disease, or unfavorable cytogenetics.

And response-related criteria for high-risk disease included poor peripheral blast clearance after the 1-week steroid pre-phase, poor bone marrow blast clearance after the first week of chemotherapy, or no hematologic complete response after the first induction course.

Patient characteristics were well balanced between the arms, with a median age for the entire group of 40.2 years. Rituximab-treated patients had 61% CD20-positive blasts, and the no-rituximab arm had 69%.

More patients in the rituximab arm had a better ECOG performance status, although the difference was not significant. Thirteen percent were assessed as being grade 2 or higher in the rituximab arm, compared with 18% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.06).

“The proportion of high-risk patients was comparable in both arms,” Dr Maury said, “representing around two-thirds of the study population.”

In the rituximab arm, 70% were considered high-risk, compared with 64% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.46).

“However, despite this,” he said, “a significantly higher proportion of patients received allo transplant at first remission in the rituximab arm, 34% versus 20%. And since this was not explained by a different proportion of high-risk patients, this was probably due to differences in donor availability.”

Dr Maury noted that compliance to treatment was “quite good.”

Efficacy

The median follow-up was 30 months, and the primary endpoint was EFS.

The EFS rate for rituximab-treated patients at 2 years was 65%, compared with 52% for the non-rituximab patients (hazard ratio=0.66, P=0.038).

EFS was also significantly better with rituximab when patients were censored at allogeneic transplant, with a hazard ratio of 0.59 and a significance of 0.021.

However, there were no significant differences in early complete response rates, minimal residual disease (MRD) after induction, and MRD after consolidation.

“[O]nly 40% of patients could be centrally analyzed [for MRD],” Dr Maury explained, “which may be the reason why we could not detect any impact of rituximab on MRD.”

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 18% in the rituximab arm and 32% in the no-rituximab arm (hazard ratio=0.52, P=0.017). And after censoring for stem cell transplant in first complete remission, the hazard ratio was 0.49 in favor of rituximab (P=0.018).

Overall survival (OS) was not significantly different between the arms. Rituximab-treated patients had an OS rate of 71%, compared with 64% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.095).

“However, this difference became significant when censoring patients at time of allo-transplant,” Dr Maury said.

There was a 12% cumulative incidence of death in first complete remission at 2 years in each arm.

Investigators performed multivariate analysis and found that treatment with rituximab (P=0.020), age (P=0.022), white blood cell count of 30 x 109/L or higher (P=0.005), and CNS involvement all significantly impacted EFS.

When they introduced stem cell transplant in first remission as a covariable, the same factors remained significant. Allogeneic stem cell transplant in first remission did not make a significant difference on EFS (P=0.62).

Safety

One hundred twenty-four patients reported 246 severe adverse events, the most frequent of which was infection—71 in the rituximab arm and 55 in the no-rituximab arm, a difference that was not significant (P=0.16).

Severe allergic events were significantly different between the arms, with 2 severe allergic events reported in the rituximab arm and 14 in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.002). Of these 16 events, all but one were due to asparaginase.

“We believe that this may reflect the protective effect of rituximab that might inhibit B-cell protection of antibodies against asparaginase,” Dr Maury said, although the investigators did not actually measure the antibodies.

Severe lab abnormalities, neurologic and pulmonary events, coagulopathy, cardiologic and gastrointestinal events were not significantly different between the arms.

Dr Maury emphasized that the addition of rituximab to standard intensive chemotherapy is well tolerated, significantly improves EFS, and prolongs OS in patients not receiving allogeneic transplant in first remission.

While the optimal dose schedule of rituximab still remains to be determined, the GRAALL investigators believe that “the addition of rituximab should be the new standard of care for these patients,” Dr Maury declared. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators from the Group for Research on Adult Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAALL) recommend integrating rituximab into the treatment of adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) based on results of the GRAALL-R 2005 study.

Patients who received rituximab as part of their therapy had a median event-free survival (EFS) at 2 years of 65%, compared to 52% for patients who did not receive rituximab. After censoring for stem cell transplant in first complete remission, the benefit was even greater.

Sébastien Maury, MD, PhD, of Hȏpital Hénri Mondor in Creteil, France, presented the results during the plenary session of the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 1.

Dr Maury said GRAALL-R 2005 is the first phase 3, randomized study to evaluate the role of rituximab in the treatment of B-cell precursor (BCP) ALL.

Only one previous study, he said, suggested a potential benefit of adding rituximab compared to historic controls of chemotherapy alone.

He explained that, because the CD20 antigen is expressed at diagnosis in 30% to 40% of patients with BCP-ALL, investigators undertook to evaluate whether adding the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab to the ALL treatment regimen could be beneficial for newly diagnosed Ph-negative BCP-ALL patients.

Study design & population

Investigators randomized 105 patients to receive the pediatric-inspired GRAALL protocol plus rituximab and 104 patients to the same regimen without rituximab.

Patients had to have 20% or more CD20-positive leukemic blasts.

Patients in the rituximab arm received 375 mg/m2 during induction on days 1 and 7, during salvage reinduction (if needed) on days 1 and 7, during consolidation blocks (6 infusions), during late intensification on days 1 and 7, and during the first year of maintenance (6 infusions), for a total of 16 to 18 infusions.

“In this trial, allogeneic transplantation was offered in first remission to high-risk patients who were those patients with at least one of these baseline or response-related criteria,” Dr Maury said.

Investigators defined high-risk at baseline as having a white blood cell count of 30 x 109/L or higher, CNS involvement, CD10-negative disease, or unfavorable cytogenetics.

And response-related criteria for high-risk disease included poor peripheral blast clearance after the 1-week steroid pre-phase, poor bone marrow blast clearance after the first week of chemotherapy, or no hematologic complete response after the first induction course.

Patient characteristics were well balanced between the arms, with a median age for the entire group of 40.2 years. Rituximab-treated patients had 61% CD20-positive blasts, and the no-rituximab arm had 69%.

More patients in the rituximab arm had a better ECOG performance status, although the difference was not significant. Thirteen percent were assessed as being grade 2 or higher in the rituximab arm, compared with 18% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.06).

“The proportion of high-risk patients was comparable in both arms,” Dr Maury said, “representing around two-thirds of the study population.”

In the rituximab arm, 70% were considered high-risk, compared with 64% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.46).

“However, despite this,” he said, “a significantly higher proportion of patients received allo transplant at first remission in the rituximab arm, 34% versus 20%. And since this was not explained by a different proportion of high-risk patients, this was probably due to differences in donor availability.”

Dr Maury noted that compliance to treatment was “quite good.”

Efficacy

The median follow-up was 30 months, and the primary endpoint was EFS.

The EFS rate for rituximab-treated patients at 2 years was 65%, compared with 52% for the non-rituximab patients (hazard ratio=0.66, P=0.038).

EFS was also significantly better with rituximab when patients were censored at allogeneic transplant, with a hazard ratio of 0.59 and a significance of 0.021.

However, there were no significant differences in early complete response rates, minimal residual disease (MRD) after induction, and MRD after consolidation.

“[O]nly 40% of patients could be centrally analyzed [for MRD],” Dr Maury explained, “which may be the reason why we could not detect any impact of rituximab on MRD.”

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 18% in the rituximab arm and 32% in the no-rituximab arm (hazard ratio=0.52, P=0.017). And after censoring for stem cell transplant in first complete remission, the hazard ratio was 0.49 in favor of rituximab (P=0.018).

Overall survival (OS) was not significantly different between the arms. Rituximab-treated patients had an OS rate of 71%, compared with 64% in the no-rituximab arm (P=0.095).

“However, this difference became significant when censoring patients at time of allo-transplant,” Dr Maury said.

There was a 12% cumulative incidence of death in first complete remission at 2 years in each arm.

Investigators performed multivariate analysis and found that treatment with rituximab (P=0.020), age (P=0.022), white blood cell count of 30 x 109/L or higher (P=0.005), and CNS involvement all significantly impacted EFS.

When they introduced stem cell transplant in first remission as a covariable, the same factors remained significant. Allogeneic stem cell transplant in first remission did not make a significant difference on EFS (P=0.62).

Safety

One hundred twenty-four patients reported 246 severe adverse events, the most frequent of which was infection—71 in the rituximab arm and 55 in the no-rituximab arm, a difference that was not significant (P=0.16).