User login

Mind the Gap: Case Study in Toxicology

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

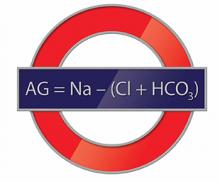

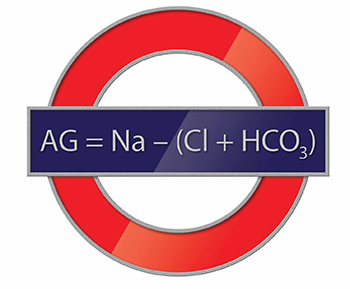

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome on the rise

The percentage of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) was nearly twice as high in 2012 as it was 2011, report Dr. S. W. Patrick and coauthors from the department of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University.

In a retrospective, serial, cross-sectional analysis, NAS occurred in 5.8 per 1,000 hospital births in 2012, compared with 3.4 per 1,000 hospital births in 2009. Aggregate hospital charges for NAS also increased significantly, from $732 million to $1.5 billion (P < .001), the investigators found.

Additionally, infants diagnosed with NAS were more likely than infants without NAS to have complications including low birth weight, transient tachypnea, jaundice, feeding difficulty, respiratory distress syndrome, and sepsis, Dr. Patrick and colleagues reported.

“NAS results in longer, more costly and complicated hospital stays, compared with other hospital births,” the investigators wrote in the paper. “The rapid rise in NAS parallels the increase in [opioid pain reliever] use in the United States, suggesting that preventing opioid overuse and misuse, especially before pregnancy, may prevent NAS.”

Read the full study in Journal of Perinatology (doi:10.1038/jp.2015.36).

The percentage of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) was nearly twice as high in 2012 as it was 2011, report Dr. S. W. Patrick and coauthors from the department of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University.

In a retrospective, serial, cross-sectional analysis, NAS occurred in 5.8 per 1,000 hospital births in 2012, compared with 3.4 per 1,000 hospital births in 2009. Aggregate hospital charges for NAS also increased significantly, from $732 million to $1.5 billion (P < .001), the investigators found.

Additionally, infants diagnosed with NAS were more likely than infants without NAS to have complications including low birth weight, transient tachypnea, jaundice, feeding difficulty, respiratory distress syndrome, and sepsis, Dr. Patrick and colleagues reported.

“NAS results in longer, more costly and complicated hospital stays, compared with other hospital births,” the investigators wrote in the paper. “The rapid rise in NAS parallels the increase in [opioid pain reliever] use in the United States, suggesting that preventing opioid overuse and misuse, especially before pregnancy, may prevent NAS.”

Read the full study in Journal of Perinatology (doi:10.1038/jp.2015.36).

The percentage of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) was nearly twice as high in 2012 as it was 2011, report Dr. S. W. Patrick and coauthors from the department of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University.

In a retrospective, serial, cross-sectional analysis, NAS occurred in 5.8 per 1,000 hospital births in 2012, compared with 3.4 per 1,000 hospital births in 2009. Aggregate hospital charges for NAS also increased significantly, from $732 million to $1.5 billion (P < .001), the investigators found.

Additionally, infants diagnosed with NAS were more likely than infants without NAS to have complications including low birth weight, transient tachypnea, jaundice, feeding difficulty, respiratory distress syndrome, and sepsis, Dr. Patrick and colleagues reported.

“NAS results in longer, more costly and complicated hospital stays, compared with other hospital births,” the investigators wrote in the paper. “The rapid rise in NAS parallels the increase in [opioid pain reliever] use in the United States, suggesting that preventing opioid overuse and misuse, especially before pregnancy, may prevent NAS.”

Read the full study in Journal of Perinatology (doi:10.1038/jp.2015.36).

PAS: Screen for postpartum depression during infant hospitalization

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Screening for maternal postpartum depression during an infant’s hospitalization captures large numbers of previously unscreened women.

Major finding: Twenty-eight percent of women screened during their infant’s hospital admission were deemed at risk for postpartum depression.

Data source: The study included 310 mothers, only 18% of whom had been screened for postpartum depression during their infant’s routine office visits as guidelines recommend.

Disclosures: This study was conducted free of commercial support. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

PAS: Screen for postpartum depression during infant hospitalization

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening mothers for postpartum depression during an infant’s routine office visits. Realistically, that often doesn’t happen, because of time constraints, because of physician discomfort with diagnosing the illness, or because an infant with prolonged hospitalization for severe illness misses the scheduled office visits, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening mothers for postpartum depression during an infant’s routine office visits. Realistically, that often doesn’t happen, because of time constraints, because of physician discomfort with diagnosing the illness, or because an infant with prolonged hospitalization for severe illness misses the scheduled office visits, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening mothers for postpartum depression during an infant’s routine office visits. Realistically, that often doesn’t happen, because of time constraints, because of physician discomfort with diagnosing the illness, or because an infant with prolonged hospitalization for severe illness misses the scheduled office visits, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Screening for maternal postpartum depression during an infant’s hospitalization captures large numbers of previously unscreened women.

Major finding: Twenty-eight percent of women screened during their infant’s hospital admission were deemed at risk for postpartum depression.

Data source: The study included 310 mothers, only 18% of whom had been screened for postpartum depression during their infant’s routine office visits as guidelines recommend.

Disclosures: This study was conducted free of commercial support. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Cesarean intervention reduces rates in low-risk pregnancies

An intervention involving audits of indications for cesarean delivery, feedback for health professionals, and implementation of best practices has resulted in a small but significant reduction in the rate of cesarean deliveries without negatively impacting maternal or neonatal outcomes.

A cluster-randomized controlled trial in 32 Quebec hospitals showed introduction of the 1.5-year intervention – involving 52,265 women – was associated with a 10% reduction in cesarean delivery rates (which went from 22.5% to 21.8%, for an adjusted odds ratio of 0.90, P = 0.04) in the year after introduction of the intervention, compared with the year before, according to the study (N. Eng. J. Med. 2015;372:1710-21).

The reduction in the rate of cesarean deliveries was even greater among low-risk pregnancies (adjusted OR, 0.80; P = .03), but was not significant among high-risk pregnancies, with the only impact on complications being a significant increase in maternal blood transfusion rates. Also, there was a significant reduction in minor and major neonatal morbidity in the intervention group.

“The QUARISMA program was designed to allow health professionals to assess care relative to operational standards (algorithms), to detect cases in which care could have been improved and an unnecessary cesarean delivery avoided, and to standardize clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Nils Chaillet of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (Que.) and his associates.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

An intervention involving audits of indications for cesarean delivery, feedback for health professionals, and implementation of best practices has resulted in a small but significant reduction in the rate of cesarean deliveries without negatively impacting maternal or neonatal outcomes.

A cluster-randomized controlled trial in 32 Quebec hospitals showed introduction of the 1.5-year intervention – involving 52,265 women – was associated with a 10% reduction in cesarean delivery rates (which went from 22.5% to 21.8%, for an adjusted odds ratio of 0.90, P = 0.04) in the year after introduction of the intervention, compared with the year before, according to the study (N. Eng. J. Med. 2015;372:1710-21).

The reduction in the rate of cesarean deliveries was even greater among low-risk pregnancies (adjusted OR, 0.80; P = .03), but was not significant among high-risk pregnancies, with the only impact on complications being a significant increase in maternal blood transfusion rates. Also, there was a significant reduction in minor and major neonatal morbidity in the intervention group.

“The QUARISMA program was designed to allow health professionals to assess care relative to operational standards (algorithms), to detect cases in which care could have been improved and an unnecessary cesarean delivery avoided, and to standardize clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Nils Chaillet of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (Que.) and his associates.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

An intervention involving audits of indications for cesarean delivery, feedback for health professionals, and implementation of best practices has resulted in a small but significant reduction in the rate of cesarean deliveries without negatively impacting maternal or neonatal outcomes.

A cluster-randomized controlled trial in 32 Quebec hospitals showed introduction of the 1.5-year intervention – involving 52,265 women – was associated with a 10% reduction in cesarean delivery rates (which went from 22.5% to 21.8%, for an adjusted odds ratio of 0.90, P = 0.04) in the year after introduction of the intervention, compared with the year before, according to the study (N. Eng. J. Med. 2015;372:1710-21).

The reduction in the rate of cesarean deliveries was even greater among low-risk pregnancies (adjusted OR, 0.80; P = .03), but was not significant among high-risk pregnancies, with the only impact on complications being a significant increase in maternal blood transfusion rates. Also, there was a significant reduction in minor and major neonatal morbidity in the intervention group.

“The QUARISMA program was designed to allow health professionals to assess care relative to operational standards (algorithms), to detect cases in which care could have been improved and an unnecessary cesarean delivery avoided, and to standardize clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Nils Chaillet of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (Que.) and his associates.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Audits of indications for cesarean delivery and feedback for health professionals can reduce the rate of cesarean deliveries, especially in low-risk pregnancies.

Major finding: A multifaceted intervention resulted in an overall 10% reduction in the rate of cesarean deliveries.

Data source: A cluster-randomized controlled trial in 32 Quebec hospitals, involving a total of 184,952 women.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

To drink or not to drink – What do you tell your patients?

It has been more than 40 years since fetal alcohol syndrome was first recognized as a brain disorder leading to a wide range of learning and behavior problems – fetal alcohol spectrum disorders – in children prenatally exposed to alcohol.

Over that time, obstetric providers have played a key role in counseling patients, both preconception and during pregnancy, about the risks associated with various amounts and patterns of alcohol consumption. This advice is critical as about half of women of reproductive age in the United States consume some alcohol, and about half of pregnancies are not planned, leading to a high prevalence of exposure to alcohol prior to pregnancy recognition.

But how much alcohol at what specific time in early pregnancy leads to a known risk of learning and behavior problems as children reach school age?

The U.S. Surgeon General’s Office and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that alcohol be avoided entirely during all weeks of pregnancy, as there is no known safe amount, type of beverage, or timing in gestation that a woman can consume alcohol. However, in recent years, a number of publications have suggested that “low to moderate” alcohol consumption in pregnancy is not demonstrably harmful to the developing fetus, at least in terms of learning ability.

Three recently published studies exemplify the dilemma. Colleen M. O’Leary et. al. examined educational achievement in 8- to 9-year olds in Western Australia (Pediatrics 2013;132:e468-75). The sample was a population-based cohort of 4,056 infants randomly ascertained with births between 1995 and 1997 whose mothers had responded to a postnatal survey about health behaviors including alcohol consumption. Researchers linked these infants to a midwives database to obtain birth details and to an educational testing database to obtain measures of school achievement.

Children were not evaluated for the physical features or a diagnosis of FAS or something on the FASD spectrum. Low alcohol consumption was defined as 1-2 standard drinks (10 g alcohol per standard drink in Australia) per occasion and fewer than 7 drinks per week. Moderate alcohol consumption was defined as 3-4 standard drinks per occasion and no more than 7 drinks per week. Binge drinking was defined as 5 or more drinks per occasion less frequently than weekly, and heavy drinking was defined as more than 7 standard drinks per week including binge drinking weekly or more often.

Underachievement in reading and writing was significantly associated with either heavy first trimester or binge drinking in late pregnancy. However, achievement in numeracy, reading, spelling and writing was not significantly impaired with low to moderate prenatal alcohol exposure.

In a study of a sample derived from the Danish National Birth Cohort, 1,628 women and their children were sampled from the original cohort based on maternal alcohol drinking patterns reported in pregnancy (BJOG 2012;119:1191-1200). The child’s IQ was assessed at 5 years of age.

Children were not specifically evaluated for the physical features of FAS or a diagnosis of something on the FASD spectrum. Levels of alcohol consumption were categorized as none, average intake of 1-4 standard drinks per week (12 g alcohol per standard drink in Denmark), 5-8 standard drinks per week, and more than 8 standard drinks per week. There were no differences in the performance of children whose mothers consumed up to 8 standard drinks per week at some point in pregnancy compared to children whose mothers abstained.

In a subsequently published study in which researchers used the same sample, the parent and teacher versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, a standard behavioral screening tool, were completed by the mothers and the preschool teachers (BJOG 2013;120:1042-50). After adjustment for confounders, overall there were no significant associations found for any drinking category compared to abstainers.

Many experts asked to comment on these findings emphasized that these studies were limited to a few measures of learning and behavior in young children that may not be reflective of the range of alcohol-related developmental effects. They also pointed out the great difficulty in obtaining an accurate report of alcohol exposure in the absence of a sensitive and specific biomarker.

For example, recall of specific quantities, frequencies, and timing of alcohol consumption either after delivery (the Australian study) or in a single prenatal interview that was conducted sometime between 7 and 39 weeks’ gestation (the Danish study) may be inaccurate. This could be because of difficulty in remembering these details, as well as the influence of the social unacceptability of drinking during pregnancy.