User login

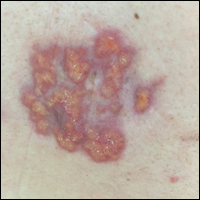

Irregular Yellow-Brown Plaques on the Trunk and Thighs

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

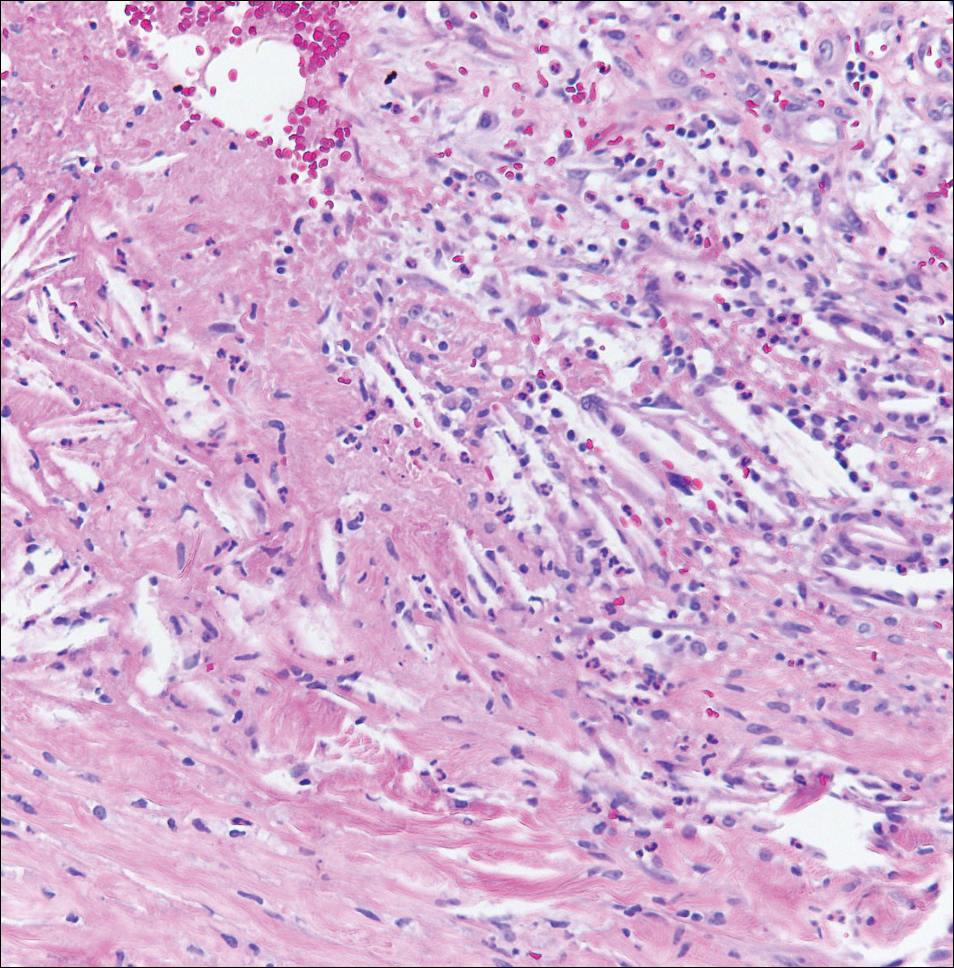

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

A 40-year-old man presented with tender lesions on the back, abdomen, and thighs of 10 years' duration. His medical history was remarkable for follicular lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance diagnosed 5 years after the onset of skin symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous irregularly shaped, yellow plaques on the back, abdomen, and thighs with overlying telangiectasia. A single lesion was noted to extend from a scar.

Scaly Plaque With Pustules and Anonychia on the Middle Finger

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

A 69-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a persistent rash on the right middle finger of 5 years’ duration (left). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated scaly plaque with pustules and anonychia localized to the right middle finger (right). Fungal and bacterial cultures revealed sterile pustules. The patient was successfully treated with an occluded superpotent topical steroid alternating with a topical vitamin D analogue.