User login

Join an SHM committee!

Opportunities to develop new mentoring relationships

Society of Hospital Medicine committee participation is an exciting opportunity available to all medical students and resident physicians. Whether you are hoping to explore new facets of hospital medicine, or take the next step in shaping your career, committee involvement creates opportunities for individuals to share their insight and work collaboratively on key SHM priorities to shape the future of hospital medicine.

If you are interested, the application is short and straightforward. Requisite SHM membership is free for students and discounted for resident members. And the benefits of committee participation are far reaching.

SHM committee opportunities will cater to most interests and career paths. Our personal interest in academic hospital medicine and medical education led us to the Physicians-In-Training (PIT) committee, but seventeen committees are available (see the complete list below). Review the committee descriptions online and select the one that best aligns with your individual interests. A mentor’s insight may be valuable in determining which committee is the best opportunity.

SHM Committee Opportunities:

- Academic Hospitalist Committee

- Annual Meeting Committee

- Awards Committee

- Chapter Support Committee

- Communications Strategy Committee

- Digital Learning Committee

- Education Committee

- Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee

- Membership Committee

- Patient Experience Committee

- Performance Measurement & Reporting Committee

- Physicians in Training Committee

- Practice Analysis Committee

- Practice Management Committee

- Public Policy Committee

- Research Committee

- Special Interest Group Support Committee

Membership is a boon. While opportunities for personal and professional growth are less tangible than committee work products, they remain vitally important for trainees. Through their engagement, medical students and resident physicians will have the opportunity to develop new mentoring relationships beyond the confines of their training site. We believe that committee engagement offers a “leg up” on the competition for residency and fellowship applications. Moreover, networking with hospital medicine leaders from across the country has allowed us to meet and engage with current and future colleagues, as well as potential future employers. In the long term, these experiences are sure to shape our future careers. More than a line on one’s curriculum vitae, meaningful contributions will open doors to new and exciting opportunities at our home institutions and nationally through SHM.

Balancing your training requirements with committee involvement is feasible with a little foresight and flexibility. Committee participation typically requires no more than 3-5 hours per month. Monthly committee calls account for 1 hour. Time is also spent preparing for committee calls as well as working on the action items you volunteered to complete. Individual scheduling is flexible, and contributions can occur offline if one is temporarily unavailable because of training obligations. Commitments are for at least 1 year and attendance at the SHM annual conference is highly encouraged but not required. Akin to other facets of life, the degree of participation will be linked with the value derived from the experience.

SHM committees are filled by seasoned hospitalists with dizzying accomplishments. This inherent strength can lead to feelings of uncertainty among newcomers (i.e., impostor syndrome). What can I offer? Does my perspective matter? Reflecting on these fears, we are certain that we could not have been welcomed with more enthusiasm. Our committee colleagues have been 110% supportive, receptive of our viewpoints, committed to our professional growth, and genuine when reaching out to collaborate. Treated as peers, we believe that members are valued based on their commitment and not their level of training or experience.

Committees are looking for capable individuals who have a demonstrated commitment to hospital medicine, as well as specific interests and value-added skills that will enhance the objectives of the committee they are applying for. For medical students and resident physicians, selection to a committee is competitive. While not required, a letter of support from a close mentor may be beneficial. Experience has demonstrated time and again that SHM is looking to engage and cultivate future hospital medicine leaders. To that end, all should take advantage.

Ultimately, we believe that our participation has helped motivate and influence our professional paths. We encourage all medical students and resident physicians to take the next step in their hospital medicine career by applying for committee membership. Our voice as trainees is one that needs further representation within SHM. We hope this call to action will encourage you to apply to a committee. The application can be found at the following link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership/committees/#Apply_for_a_Committee.

Dr. Bartlett is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque. Mr. Namavar is a medical student at Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University Chicago.

Opportunities to develop new mentoring relationships

Opportunities to develop new mentoring relationships

Society of Hospital Medicine committee participation is an exciting opportunity available to all medical students and resident physicians. Whether you are hoping to explore new facets of hospital medicine, or take the next step in shaping your career, committee involvement creates opportunities for individuals to share their insight and work collaboratively on key SHM priorities to shape the future of hospital medicine.

If you are interested, the application is short and straightforward. Requisite SHM membership is free for students and discounted for resident members. And the benefits of committee participation are far reaching.

SHM committee opportunities will cater to most interests and career paths. Our personal interest in academic hospital medicine and medical education led us to the Physicians-In-Training (PIT) committee, but seventeen committees are available (see the complete list below). Review the committee descriptions online and select the one that best aligns with your individual interests. A mentor’s insight may be valuable in determining which committee is the best opportunity.

SHM Committee Opportunities:

- Academic Hospitalist Committee

- Annual Meeting Committee

- Awards Committee

- Chapter Support Committee

- Communications Strategy Committee

- Digital Learning Committee

- Education Committee

- Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee

- Membership Committee

- Patient Experience Committee

- Performance Measurement & Reporting Committee

- Physicians in Training Committee

- Practice Analysis Committee

- Practice Management Committee

- Public Policy Committee

- Research Committee

- Special Interest Group Support Committee

Membership is a boon. While opportunities for personal and professional growth are less tangible than committee work products, they remain vitally important for trainees. Through their engagement, medical students and resident physicians will have the opportunity to develop new mentoring relationships beyond the confines of their training site. We believe that committee engagement offers a “leg up” on the competition for residency and fellowship applications. Moreover, networking with hospital medicine leaders from across the country has allowed us to meet and engage with current and future colleagues, as well as potential future employers. In the long term, these experiences are sure to shape our future careers. More than a line on one’s curriculum vitae, meaningful contributions will open doors to new and exciting opportunities at our home institutions and nationally through SHM.

Balancing your training requirements with committee involvement is feasible with a little foresight and flexibility. Committee participation typically requires no more than 3-5 hours per month. Monthly committee calls account for 1 hour. Time is also spent preparing for committee calls as well as working on the action items you volunteered to complete. Individual scheduling is flexible, and contributions can occur offline if one is temporarily unavailable because of training obligations. Commitments are for at least 1 year and attendance at the SHM annual conference is highly encouraged but not required. Akin to other facets of life, the degree of participation will be linked with the value derived from the experience.

SHM committees are filled by seasoned hospitalists with dizzying accomplishments. This inherent strength can lead to feelings of uncertainty among newcomers (i.e., impostor syndrome). What can I offer? Does my perspective matter? Reflecting on these fears, we are certain that we could not have been welcomed with more enthusiasm. Our committee colleagues have been 110% supportive, receptive of our viewpoints, committed to our professional growth, and genuine when reaching out to collaborate. Treated as peers, we believe that members are valued based on their commitment and not their level of training or experience.

Committees are looking for capable individuals who have a demonstrated commitment to hospital medicine, as well as specific interests and value-added skills that will enhance the objectives of the committee they are applying for. For medical students and resident physicians, selection to a committee is competitive. While not required, a letter of support from a close mentor may be beneficial. Experience has demonstrated time and again that SHM is looking to engage and cultivate future hospital medicine leaders. To that end, all should take advantage.

Ultimately, we believe that our participation has helped motivate and influence our professional paths. We encourage all medical students and resident physicians to take the next step in their hospital medicine career by applying for committee membership. Our voice as trainees is one that needs further representation within SHM. We hope this call to action will encourage you to apply to a committee. The application can be found at the following link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership/committees/#Apply_for_a_Committee.

Dr. Bartlett is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque. Mr. Namavar is a medical student at Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University Chicago.

Society of Hospital Medicine committee participation is an exciting opportunity available to all medical students and resident physicians. Whether you are hoping to explore new facets of hospital medicine, or take the next step in shaping your career, committee involvement creates opportunities for individuals to share their insight and work collaboratively on key SHM priorities to shape the future of hospital medicine.

If you are interested, the application is short and straightforward. Requisite SHM membership is free for students and discounted for resident members. And the benefits of committee participation are far reaching.

SHM committee opportunities will cater to most interests and career paths. Our personal interest in academic hospital medicine and medical education led us to the Physicians-In-Training (PIT) committee, but seventeen committees are available (see the complete list below). Review the committee descriptions online and select the one that best aligns with your individual interests. A mentor’s insight may be valuable in determining which committee is the best opportunity.

SHM Committee Opportunities:

- Academic Hospitalist Committee

- Annual Meeting Committee

- Awards Committee

- Chapter Support Committee

- Communications Strategy Committee

- Digital Learning Committee

- Education Committee

- Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee

- Membership Committee

- Patient Experience Committee

- Performance Measurement & Reporting Committee

- Physicians in Training Committee

- Practice Analysis Committee

- Practice Management Committee

- Public Policy Committee

- Research Committee

- Special Interest Group Support Committee

Membership is a boon. While opportunities for personal and professional growth are less tangible than committee work products, they remain vitally important for trainees. Through their engagement, medical students and resident physicians will have the opportunity to develop new mentoring relationships beyond the confines of their training site. We believe that committee engagement offers a “leg up” on the competition for residency and fellowship applications. Moreover, networking with hospital medicine leaders from across the country has allowed us to meet and engage with current and future colleagues, as well as potential future employers. In the long term, these experiences are sure to shape our future careers. More than a line on one’s curriculum vitae, meaningful contributions will open doors to new and exciting opportunities at our home institutions and nationally through SHM.

Balancing your training requirements with committee involvement is feasible with a little foresight and flexibility. Committee participation typically requires no more than 3-5 hours per month. Monthly committee calls account for 1 hour. Time is also spent preparing for committee calls as well as working on the action items you volunteered to complete. Individual scheduling is flexible, and contributions can occur offline if one is temporarily unavailable because of training obligations. Commitments are for at least 1 year and attendance at the SHM annual conference is highly encouraged but not required. Akin to other facets of life, the degree of participation will be linked with the value derived from the experience.

SHM committees are filled by seasoned hospitalists with dizzying accomplishments. This inherent strength can lead to feelings of uncertainty among newcomers (i.e., impostor syndrome). What can I offer? Does my perspective matter? Reflecting on these fears, we are certain that we could not have been welcomed with more enthusiasm. Our committee colleagues have been 110% supportive, receptive of our viewpoints, committed to our professional growth, and genuine when reaching out to collaborate. Treated as peers, we believe that members are valued based on their commitment and not their level of training or experience.

Committees are looking for capable individuals who have a demonstrated commitment to hospital medicine, as well as specific interests and value-added skills that will enhance the objectives of the committee they are applying for. For medical students and resident physicians, selection to a committee is competitive. While not required, a letter of support from a close mentor may be beneficial. Experience has demonstrated time and again that SHM is looking to engage and cultivate future hospital medicine leaders. To that end, all should take advantage.

Ultimately, we believe that our participation has helped motivate and influence our professional paths. We encourage all medical students and resident physicians to take the next step in their hospital medicine career by applying for committee membership. Our voice as trainees is one that needs further representation within SHM. We hope this call to action will encourage you to apply to a committee. The application can be found at the following link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership/committees/#Apply_for_a_Committee.

Dr. Bartlett is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque. Mr. Namavar is a medical student at Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University Chicago.

US Dermatology Residency Program Rankings Based on Academic Achievement

Rankings of US residency programs based on academic achievement are a resource for fourth-year medical students applying for residency through the National Resident Matching Program. They also highlight the leading academic training programs in each medical specialty. Currently, the Doximity Residency Navigator (https://residency.doximity.com) provides rankings of US residency programs based on either subjective or objective criteria. The subjective rankings utilize current resident and recent alumni satisfaction surveys as well as nominations from board-certified Doximity members who were asked to nominate up to 5 residency programs in their specialty that offer the best clinical training. The objective rankings are based on measurement of research output, which is calculated from the collective h-index of publications authored by graduating alumni within the last 15 years as well as the amount of research funding awarded.1

Aquino et al2 provided a ranking of US dermatology residency programs using alternative objective data measures (as of December 31, 2008) from the Doximity algorithm, including National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Dermatology Foundation (DF) funding, number of publications by full-time faculty members, number of faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies, and number of full-time faculty members serving on the editorial boards of 6 dermatology journals. The current study is an update to those rankings utilizing data from 2014.

Methods

The following data for each dermatology residency program were obtained to formulate the rankings: number of full-time faculty members, amount of NIH funding received in 2014 (https://report.nih.gov/), number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), and the number of faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies in 2014 (American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, the American Society of Dermatopathology, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, and the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery). This study was approved by the institutional review board at Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

The names of all US dermatology residency programs were obtained as of December 31, 2014, from FREIDA Online using the search term dermatology. An email was sent to a representative from each residency program (eg, residency program coordinator, program director, full-time faculty member) requesting confirmation of a list of full-time faculty members in the program, excluding part-time and volunteer faculty. If a response was not obtained or the representative declined to participate, a list was compiled using available information from that residency program’s website.

National Institutes of Health funding for 2014 was obtained for individual faculty members from the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools expenditures and reports (https://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm) by searching the first and last name of each full-time faculty member along with their affiliated institution. The search results were filtered to only include NIH funding for full-time faculty members listed as principal investigators rather than as coinvestigators. The fiscal year total cost by institute/center for each full-time faculty member’s projects was summated to obtain the total NIH funding for the program.

The total number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014 was obtained utilizing a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using each faculty member’s first and last name. The authors’ affiliations were verified for each publication, and the number of publications was summed for all full-time faculty members at each residency program. If multiple authors from the same program coauthored an article, it was only counted once toward the total number of faculty publications from that program.

Program brochures for the 2014 meetings of the 5 societies were reviewed to quantify the number of lectures given by full-time faculty members in each program.

Each residency program was assigned a score from 0 to 1.0 for each of the 4 factors of academic achievement analyzed. The program with the highest number of faculty publications was assigned a score of 1.0 and the program with the lowest number of publications was assigned a score of 0. The programs in between were subsequently assigned scores from 0 to 1.0 based on the number of publications as a percentage of the number of publications from the program with the most publications.

A weighted ranking scheme was used to rank residency programs based on the relative importance of each factor. There were 3 factors that were deemed to be the most reflective of academic achievement among dermatology residency programs: amount of NIH funding received in 2014, number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014, and number of faculty lectures given at society meetings in 2014; thus, these factors were given a weight of 1.0. The remaining factor— total number of full-time faculty members—was given a weight of 0.5. Values were totaled and programs were ranked based on the sum of these values. All quantitative analyses were performed using an electronic spreadsheet program.

Results

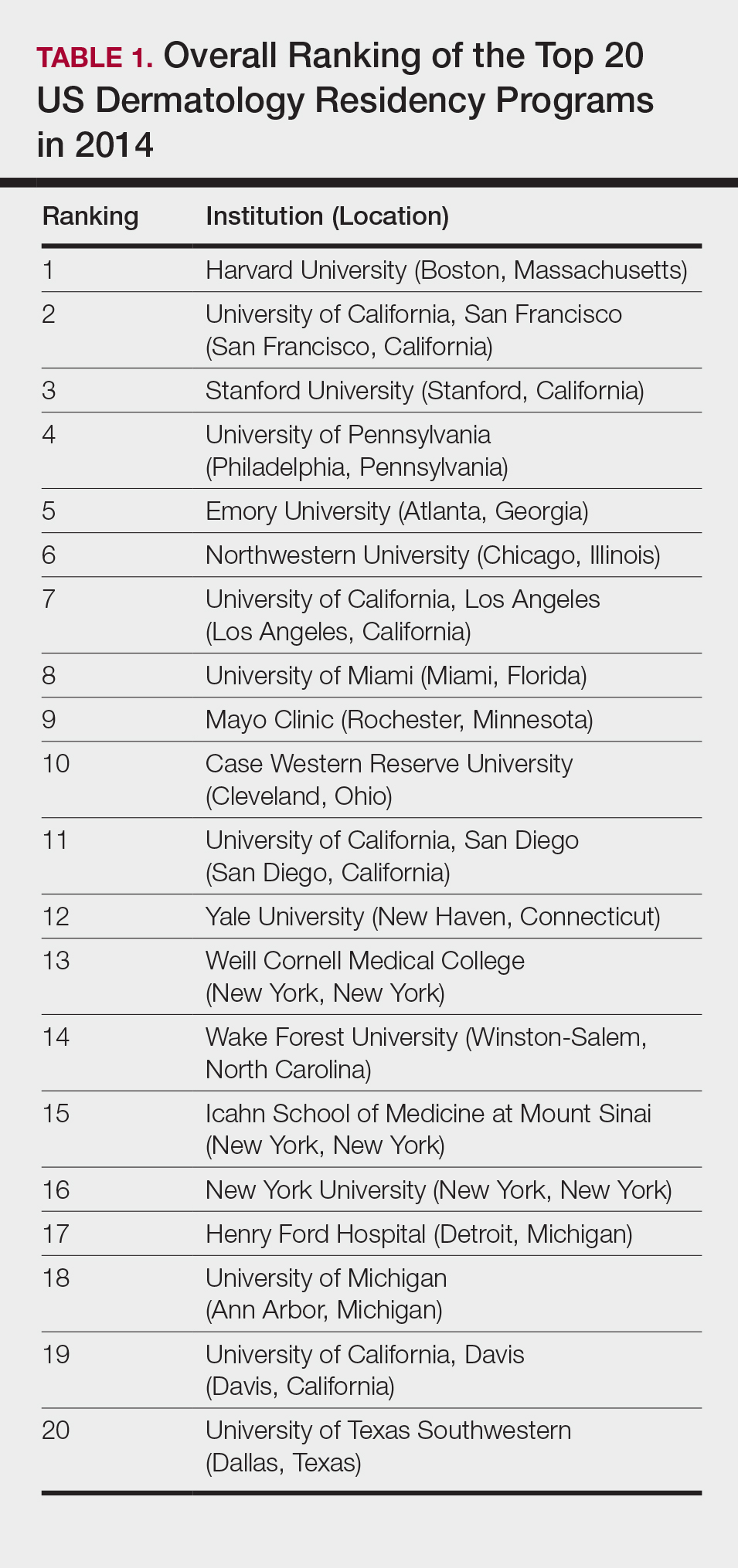

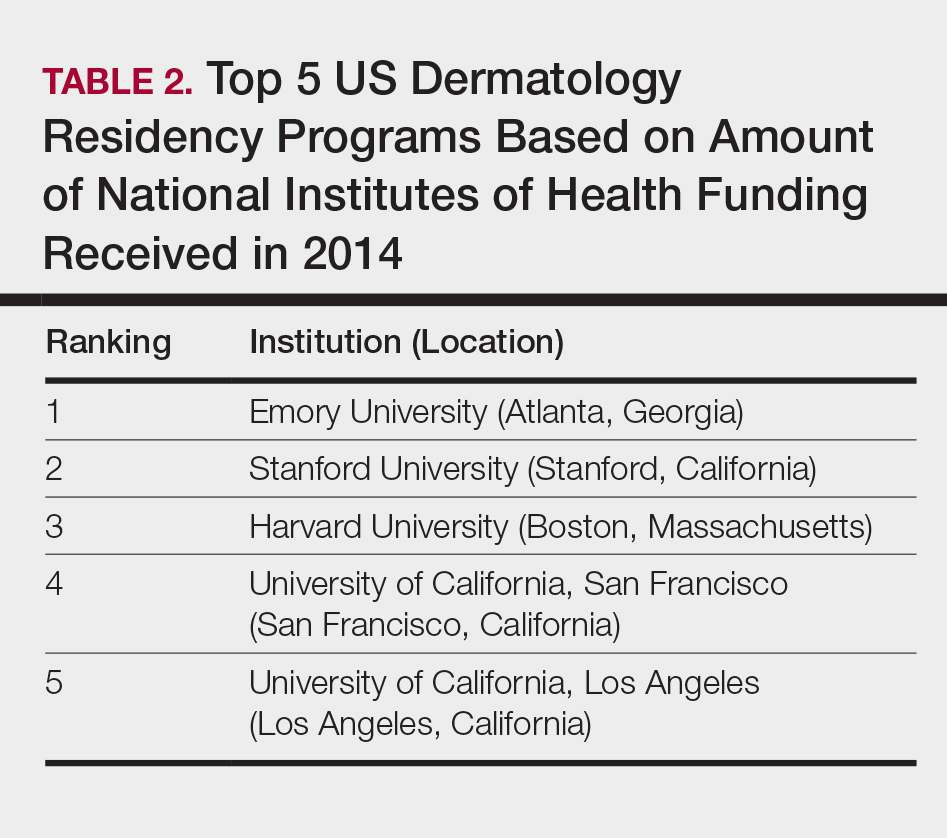

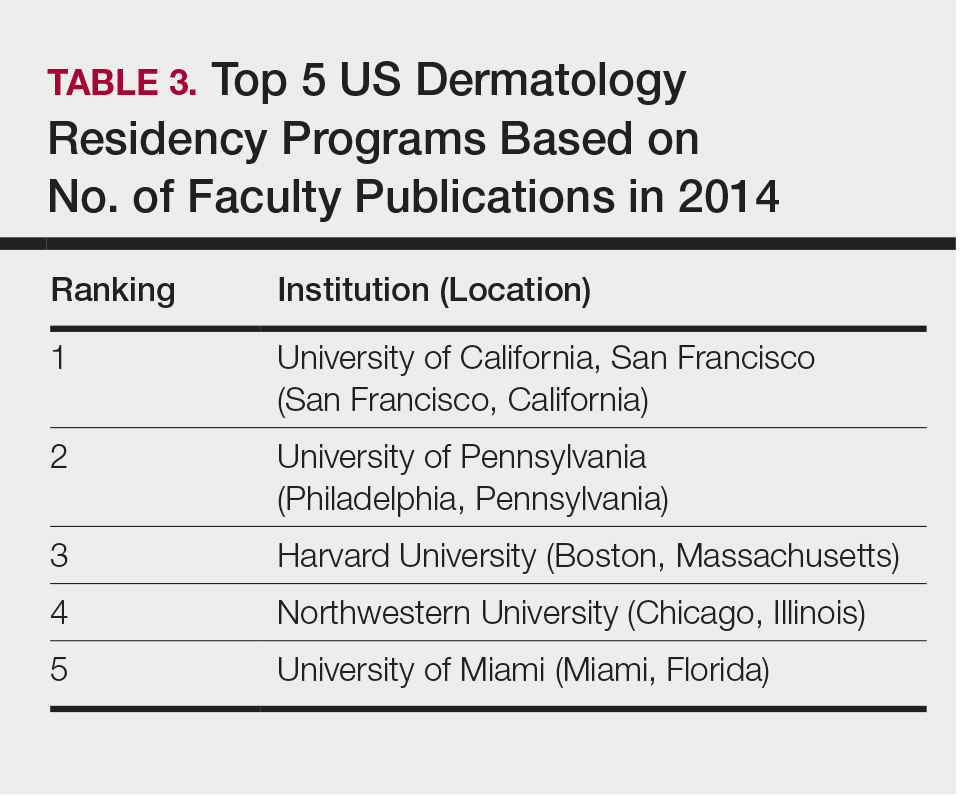

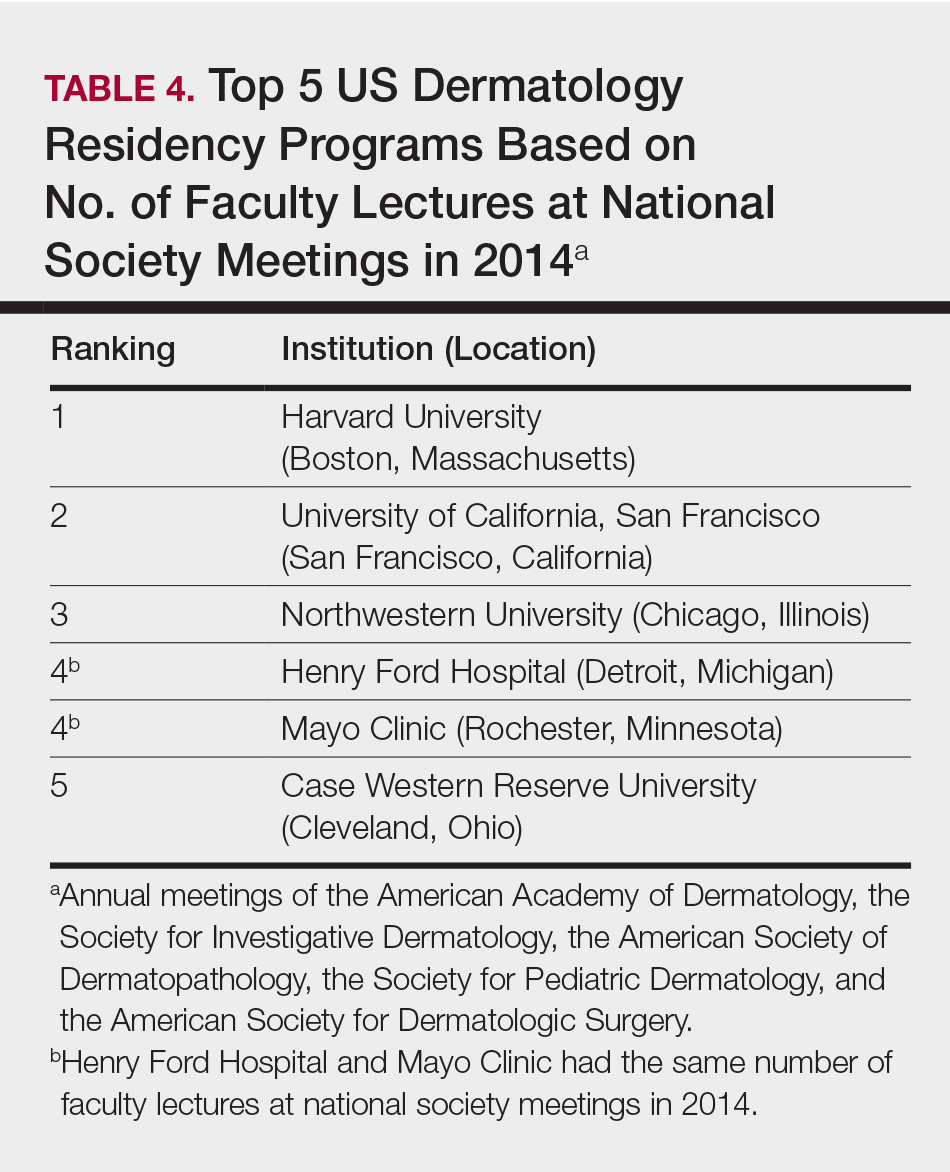

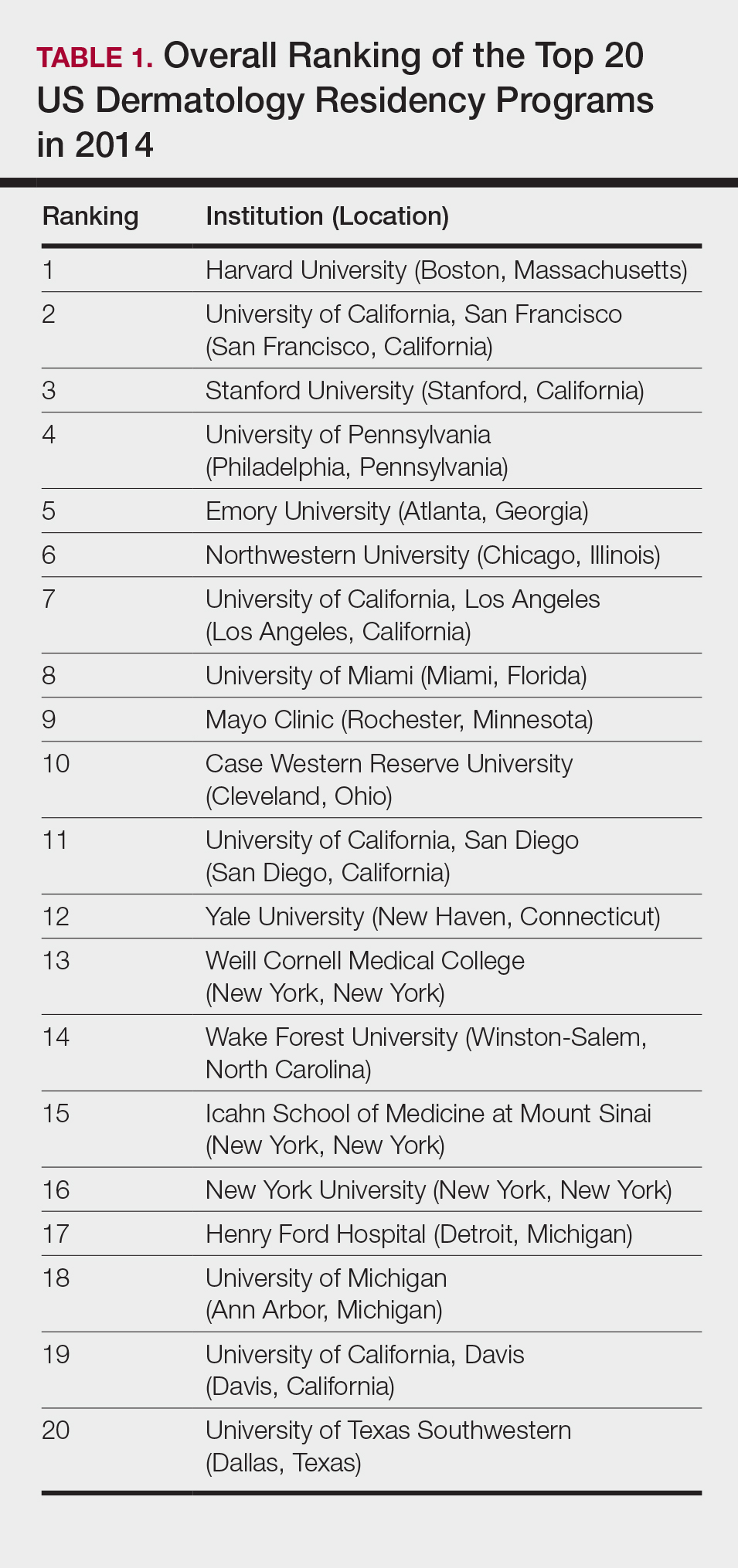

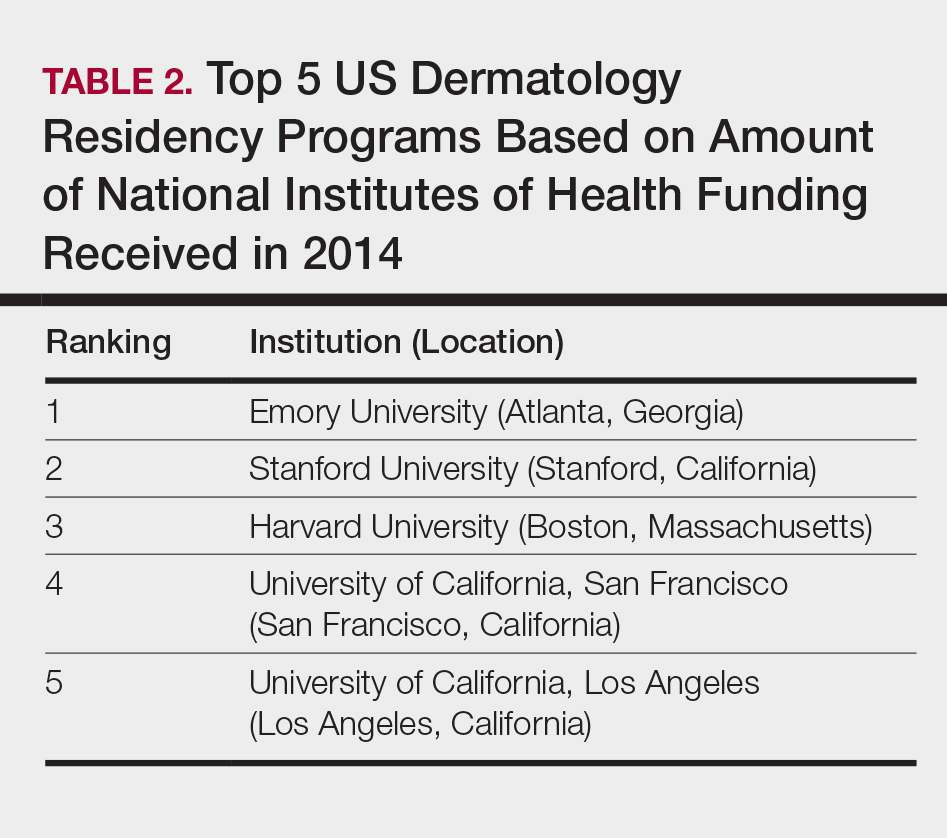

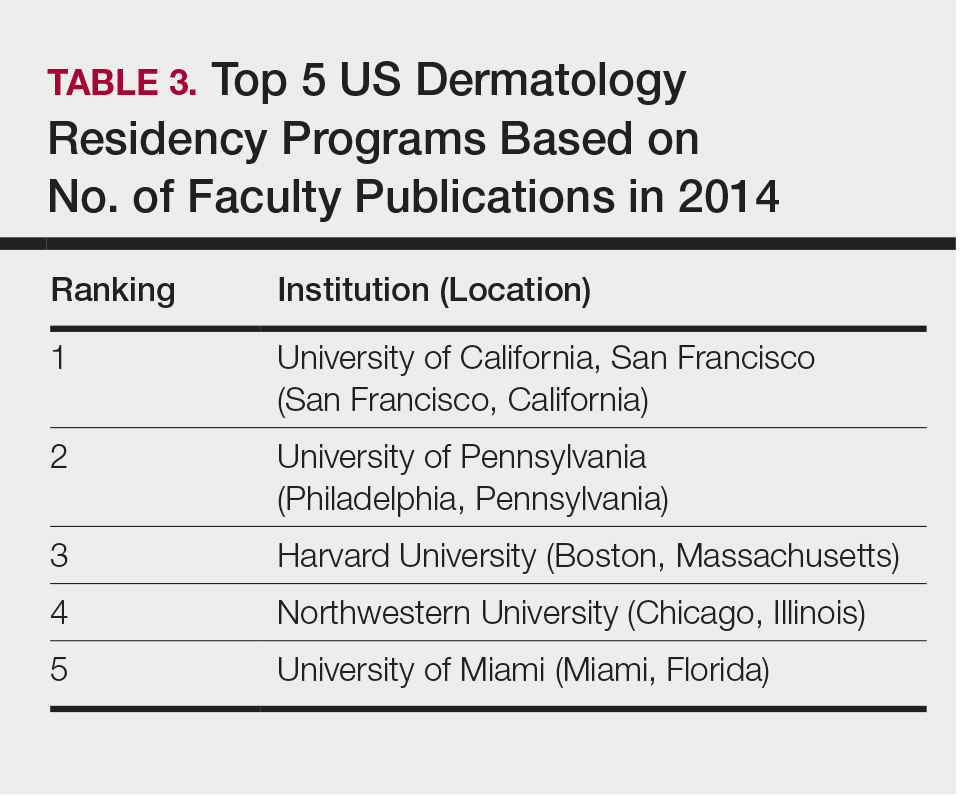

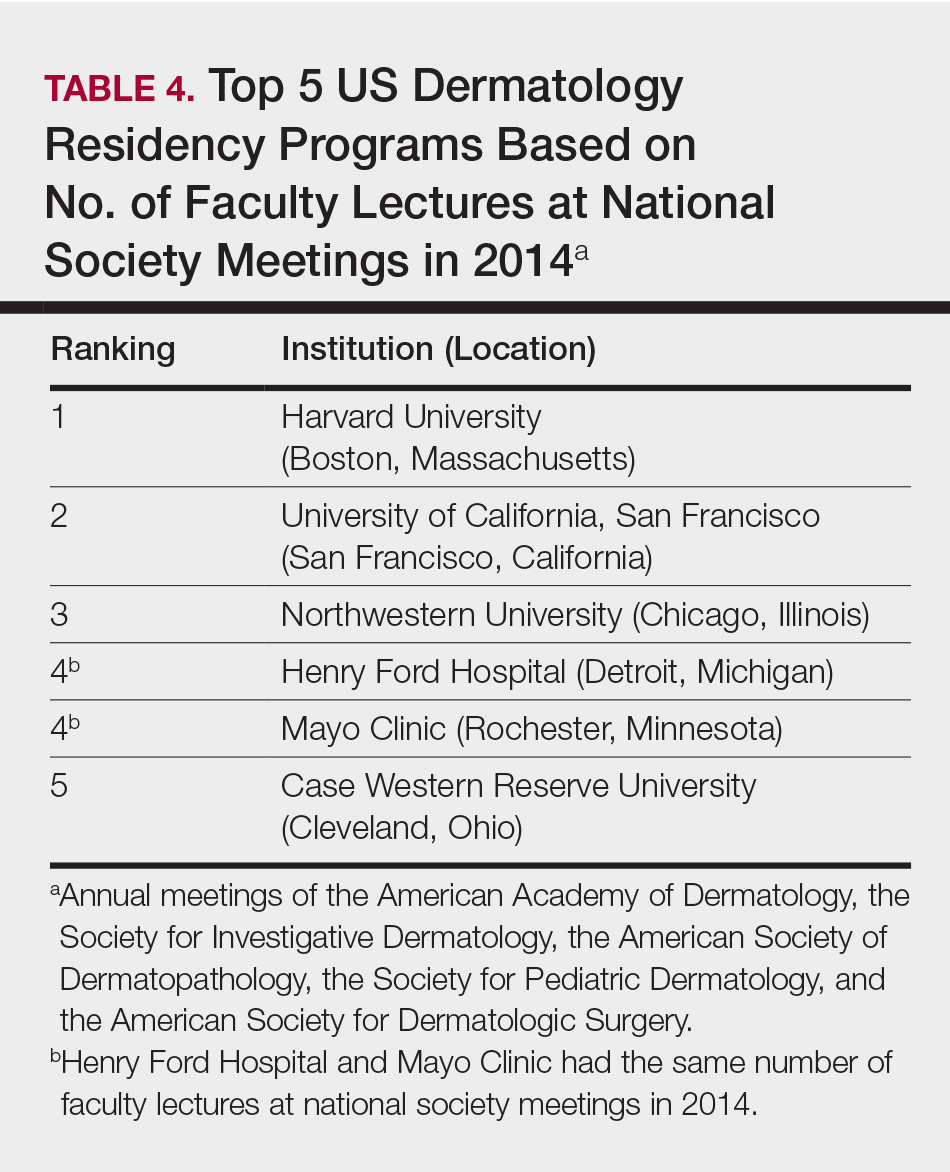

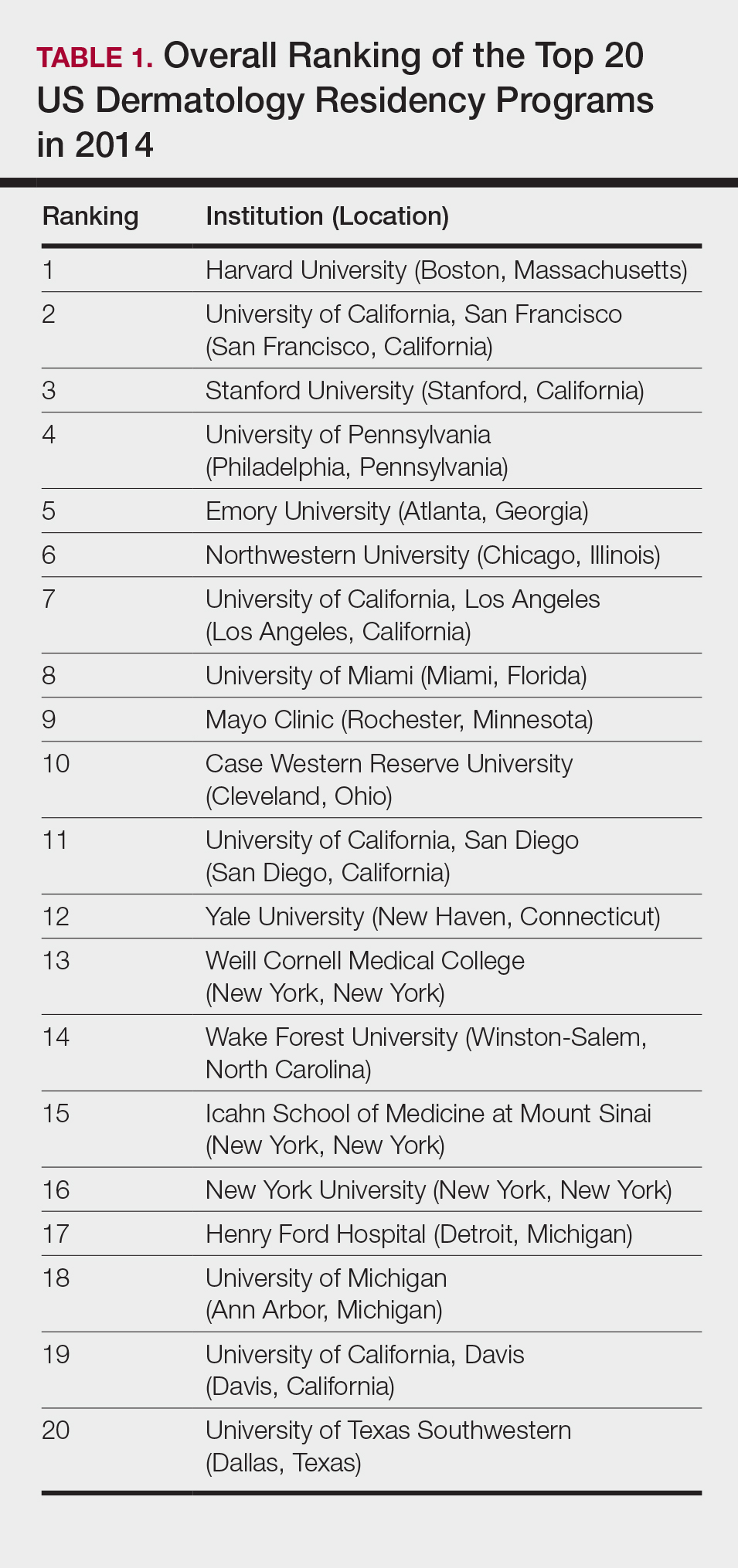

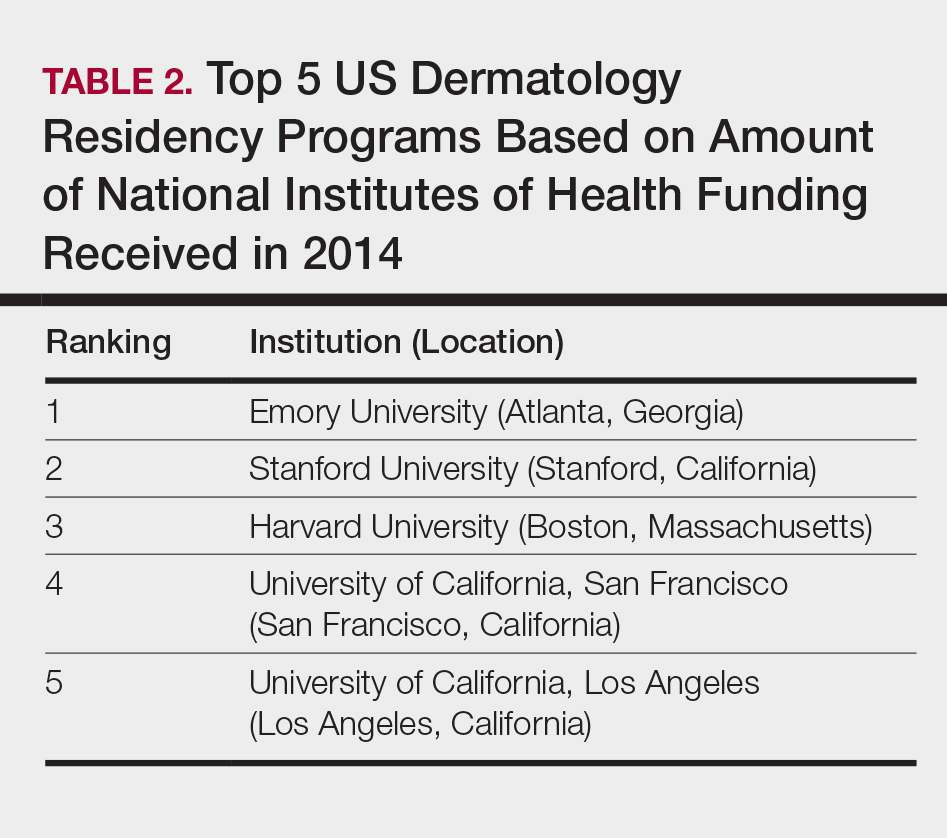

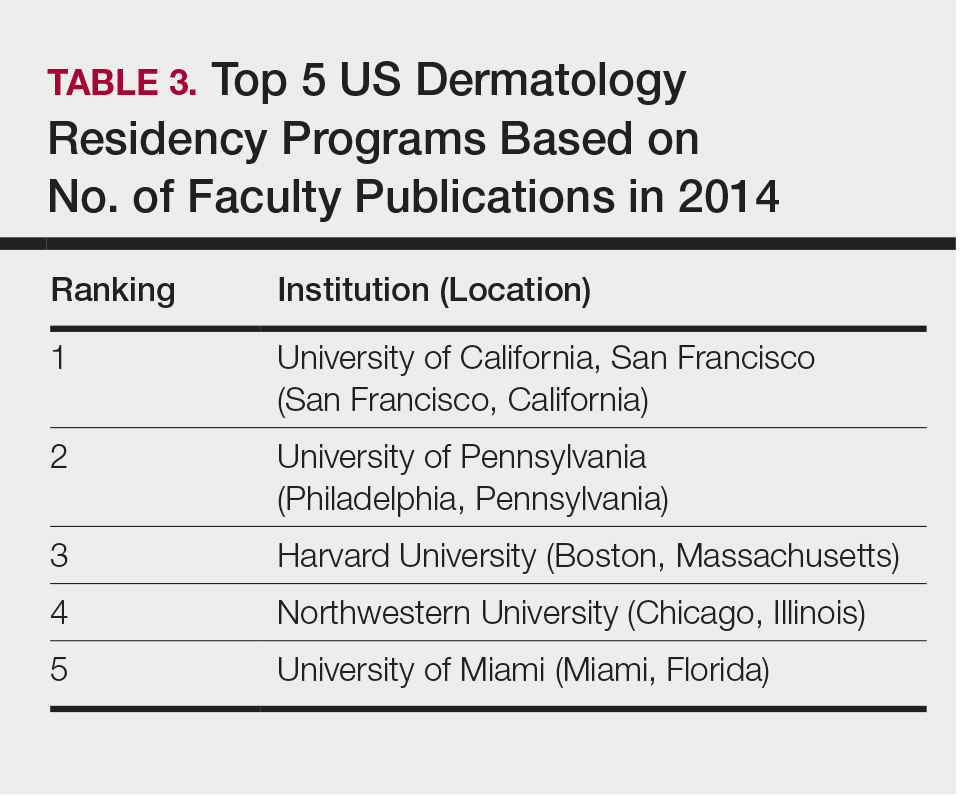

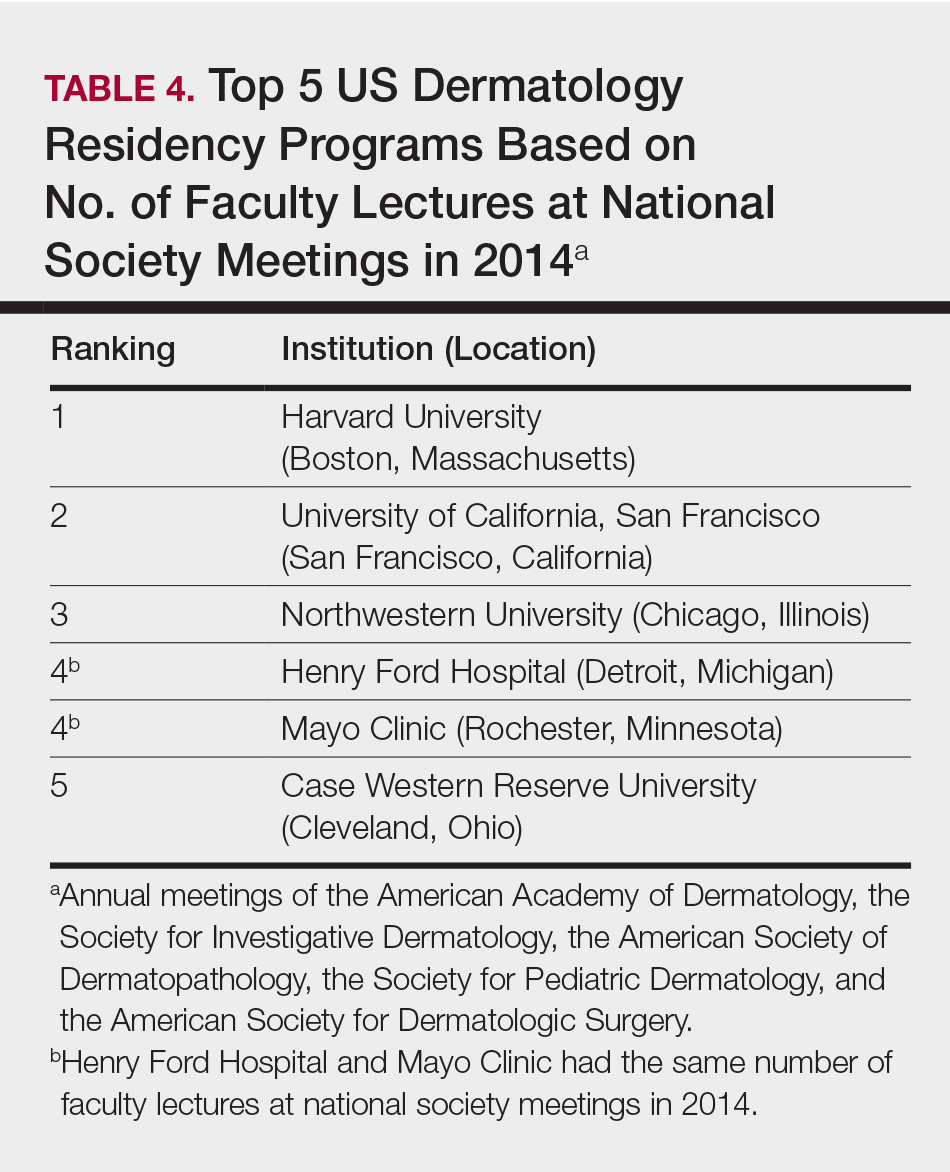

The overall ranking of the top 20 US dermatology residency programs in 2014 is presented in Table 1. The top 5 programs based on each of the 3 factors most reflective of academic achievement used in the weighted ranking algorithm are presented in Tables 2 through 4.

Comment

The ranking of US residency programs involves using data in an unbiased manner while also accounting for important subjective measures. In a 2015 survey of residency applicants (n=6285), the 5 most important factors for applicants in selecting a program were the program’s ability to prepare residents for future training or position, resident esprit de corps, faculty availability and involvement in teaching, depth and breadth of faculty, and variety of patients and clinical resources.3 However, these subjective measures are difficult to quantify in a standardized fashion. In its ranking of residency programs, the Doximity Residency Navigator utilizes surveys of current residents and recent alumni as well as nominations from board-certified Doximity members.1

One of the main issues in utilizing survey data to rank residency programs is the inherent bias that most residents and alumni possess toward their own program. Moreover, the question arises whether most residents, faculty members, or recent alumni of residency programs have sufficient knowledge of other programs to rank them in a well-informed manner.

Wu et al4 used data from 2004 to perform the first algorithmic ranking of US dermatology programs, which was based on publications in 2001 to 2004, the amount of NIH funding in 2004, DF grants in 2001 to 2004, faculty lectures delivered at national conferences in 2004, and number of full-time faculty members on the editorial boards of the top 3 US dermatology journals and the top 4 subspecialty journals. Aquino et al2 provided updated rankings that utilized a weighted algorithm to collect data from 2008 related to a number of factors, including annual amount of NIH and DF funding received, number of publications by full-time faculty members, number of faculty lectures given at 5 annual society meetings, and number of full-time faculty members who were on the editorial boards of 6 dermatology journals with the highest impact factors. The top 5 ranked programs based on the 2008 data were the University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, California); Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut); and Stanford University (Stanford, California).2

The current ranking algorithm is more indicative of a residency program’s commitment to research and scholarship, with an assumption that successful clinical training is offered. Leading researchers in the field also are usually known to be clinical experts, but the current data does not take into account the frequency, quality, or methodology of teaching provided to residents. Perhaps the most objective measure reflecting the quality of resident education would be American Board of Dermatology examination scores, but these data are not publically available. Additional factors such as the percentage of residents who received fellowship positions; diversity of the patient population; and number and extent of surgical, cosmetic, or laser procedures performed also are not readily available. Doximity provides board pass rates for each residency program, but these data are self-reported and are not taken into account in their rankings.1

The current study aimed to utilize publicly available data to rank US dermatology residency programs based on objective measures of academic achievement. A recent study showed that 531 of 793 applicants (67%) to emergency medicine residency programs were aware of the Doximity residency rankings.One-quarter of these applicants made changes to their rank list based on this data, demonstrating that residency rankings may impact applicant decision-making.5 In the future, the most accurate and unbiased rankings may be performed if each residency program joins a cooperative effort to provide more objective data about the training they provide and utilizes a standardized survey system for current residents and recent graduates to evaluate important subjective measures.

Conclusion

Based on our weighted ranking algorithm, the top 5 dermatology residency programs in 2014 were Harvard University (Boston, Massachusetts); University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, California); Stanford University (Stanford, California); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); and Emory University (Atlanta, Georgia).

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the program coordinators, full-time faculty members, program directors, and chairs who provided responses to our inquiries for additional information about their residency programs.

- Residency navigator 2017-2018. Doximity website. https://residency.doximity.com. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- Aquino LL, Wen G, Wu JJ. US dermatology residency program rankings. Cutis. 2014;94:189-194.

- Phitayakorn R, Macklin EA, Goldsmith J, et al. Applicants’ self-reported priorities in selecting a residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:21-26.

- Wu JJ, Ramirez CC, Alonso CA, et al. Ranking the dermatology programs based on measurements of academic achievement. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:3.

- Peterson WJ, Hopson LR, Khandelwal S. Impact of Doximity residency rankings on emergency medicine applicant rank lists [published online May 5, 2016]. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17:350-354.

Rankings of US residency programs based on academic achievement are a resource for fourth-year medical students applying for residency through the National Resident Matching Program. They also highlight the leading academic training programs in each medical specialty. Currently, the Doximity Residency Navigator (https://residency.doximity.com) provides rankings of US residency programs based on either subjective or objective criteria. The subjective rankings utilize current resident and recent alumni satisfaction surveys as well as nominations from board-certified Doximity members who were asked to nominate up to 5 residency programs in their specialty that offer the best clinical training. The objective rankings are based on measurement of research output, which is calculated from the collective h-index of publications authored by graduating alumni within the last 15 years as well as the amount of research funding awarded.1

Aquino et al2 provided a ranking of US dermatology residency programs using alternative objective data measures (as of December 31, 2008) from the Doximity algorithm, including National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Dermatology Foundation (DF) funding, number of publications by full-time faculty members, number of faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies, and number of full-time faculty members serving on the editorial boards of 6 dermatology journals. The current study is an update to those rankings utilizing data from 2014.

Methods

The following data for each dermatology residency program were obtained to formulate the rankings: number of full-time faculty members, amount of NIH funding received in 2014 (https://report.nih.gov/), number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), and the number of faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies in 2014 (American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, the American Society of Dermatopathology, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, and the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery). This study was approved by the institutional review board at Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

The names of all US dermatology residency programs were obtained as of December 31, 2014, from FREIDA Online using the search term dermatology. An email was sent to a representative from each residency program (eg, residency program coordinator, program director, full-time faculty member) requesting confirmation of a list of full-time faculty members in the program, excluding part-time and volunteer faculty. If a response was not obtained or the representative declined to participate, a list was compiled using available information from that residency program’s website.

National Institutes of Health funding for 2014 was obtained for individual faculty members from the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools expenditures and reports (https://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm) by searching the first and last name of each full-time faculty member along with their affiliated institution. The search results were filtered to only include NIH funding for full-time faculty members listed as principal investigators rather than as coinvestigators. The fiscal year total cost by institute/center for each full-time faculty member’s projects was summated to obtain the total NIH funding for the program.

The total number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014 was obtained utilizing a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using each faculty member’s first and last name. The authors’ affiliations were verified for each publication, and the number of publications was summed for all full-time faculty members at each residency program. If multiple authors from the same program coauthored an article, it was only counted once toward the total number of faculty publications from that program.

Program brochures for the 2014 meetings of the 5 societies were reviewed to quantify the number of lectures given by full-time faculty members in each program.

Each residency program was assigned a score from 0 to 1.0 for each of the 4 factors of academic achievement analyzed. The program with the highest number of faculty publications was assigned a score of 1.0 and the program with the lowest number of publications was assigned a score of 0. The programs in between were subsequently assigned scores from 0 to 1.0 based on the number of publications as a percentage of the number of publications from the program with the most publications.

A weighted ranking scheme was used to rank residency programs based on the relative importance of each factor. There were 3 factors that were deemed to be the most reflective of academic achievement among dermatology residency programs: amount of NIH funding received in 2014, number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014, and number of faculty lectures given at society meetings in 2014; thus, these factors were given a weight of 1.0. The remaining factor— total number of full-time faculty members—was given a weight of 0.5. Values were totaled and programs were ranked based on the sum of these values. All quantitative analyses were performed using an electronic spreadsheet program.

Results

The overall ranking of the top 20 US dermatology residency programs in 2014 is presented in Table 1. The top 5 programs based on each of the 3 factors most reflective of academic achievement used in the weighted ranking algorithm are presented in Tables 2 through 4.

Comment

The ranking of US residency programs involves using data in an unbiased manner while also accounting for important subjective measures. In a 2015 survey of residency applicants (n=6285), the 5 most important factors for applicants in selecting a program were the program’s ability to prepare residents for future training or position, resident esprit de corps, faculty availability and involvement in teaching, depth and breadth of faculty, and variety of patients and clinical resources.3 However, these subjective measures are difficult to quantify in a standardized fashion. In its ranking of residency programs, the Doximity Residency Navigator utilizes surveys of current residents and recent alumni as well as nominations from board-certified Doximity members.1

One of the main issues in utilizing survey data to rank residency programs is the inherent bias that most residents and alumni possess toward their own program. Moreover, the question arises whether most residents, faculty members, or recent alumni of residency programs have sufficient knowledge of other programs to rank them in a well-informed manner.

Wu et al4 used data from 2004 to perform the first algorithmic ranking of US dermatology programs, which was based on publications in 2001 to 2004, the amount of NIH funding in 2004, DF grants in 2001 to 2004, faculty lectures delivered at national conferences in 2004, and number of full-time faculty members on the editorial boards of the top 3 US dermatology journals and the top 4 subspecialty journals. Aquino et al2 provided updated rankings that utilized a weighted algorithm to collect data from 2008 related to a number of factors, including annual amount of NIH and DF funding received, number of publications by full-time faculty members, number of faculty lectures given at 5 annual society meetings, and number of full-time faculty members who were on the editorial boards of 6 dermatology journals with the highest impact factors. The top 5 ranked programs based on the 2008 data were the University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, California); Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut); and Stanford University (Stanford, California).2

The current ranking algorithm is more indicative of a residency program’s commitment to research and scholarship, with an assumption that successful clinical training is offered. Leading researchers in the field also are usually known to be clinical experts, but the current data does not take into account the frequency, quality, or methodology of teaching provided to residents. Perhaps the most objective measure reflecting the quality of resident education would be American Board of Dermatology examination scores, but these data are not publically available. Additional factors such as the percentage of residents who received fellowship positions; diversity of the patient population; and number and extent of surgical, cosmetic, or laser procedures performed also are not readily available. Doximity provides board pass rates for each residency program, but these data are self-reported and are not taken into account in their rankings.1

The current study aimed to utilize publicly available data to rank US dermatology residency programs based on objective measures of academic achievement. A recent study showed that 531 of 793 applicants (67%) to emergency medicine residency programs were aware of the Doximity residency rankings.One-quarter of these applicants made changes to their rank list based on this data, demonstrating that residency rankings may impact applicant decision-making.5 In the future, the most accurate and unbiased rankings may be performed if each residency program joins a cooperative effort to provide more objective data about the training they provide and utilizes a standardized survey system for current residents and recent graduates to evaluate important subjective measures.

Conclusion

Based on our weighted ranking algorithm, the top 5 dermatology residency programs in 2014 were Harvard University (Boston, Massachusetts); University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, California); Stanford University (Stanford, California); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); and Emory University (Atlanta, Georgia).

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the program coordinators, full-time faculty members, program directors, and chairs who provided responses to our inquiries for additional information about their residency programs.

Rankings of US residency programs based on academic achievement are a resource for fourth-year medical students applying for residency through the National Resident Matching Program. They also highlight the leading academic training programs in each medical specialty. Currently, the Doximity Residency Navigator (https://residency.doximity.com) provides rankings of US residency programs based on either subjective or objective criteria. The subjective rankings utilize current resident and recent alumni satisfaction surveys as well as nominations from board-certified Doximity members who were asked to nominate up to 5 residency programs in their specialty that offer the best clinical training. The objective rankings are based on measurement of research output, which is calculated from the collective h-index of publications authored by graduating alumni within the last 15 years as well as the amount of research funding awarded.1

Aquino et al2 provided a ranking of US dermatology residency programs using alternative objective data measures (as of December 31, 2008) from the Doximity algorithm, including National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Dermatology Foundation (DF) funding, number of publications by full-time faculty members, number of faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies, and number of full-time faculty members serving on the editorial boards of 6 dermatology journals. The current study is an update to those rankings utilizing data from 2014.

Methods

The following data for each dermatology residency program were obtained to formulate the rankings: number of full-time faculty members, amount of NIH funding received in 2014 (https://report.nih.gov/), number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), and the number of faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies in 2014 (American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, the American Society of Dermatopathology, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, and the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery). This study was approved by the institutional review board at Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

The names of all US dermatology residency programs were obtained as of December 31, 2014, from FREIDA Online using the search term dermatology. An email was sent to a representative from each residency program (eg, residency program coordinator, program director, full-time faculty member) requesting confirmation of a list of full-time faculty members in the program, excluding part-time and volunteer faculty. If a response was not obtained or the representative declined to participate, a list was compiled using available information from that residency program’s website.

National Institutes of Health funding for 2014 was obtained for individual faculty members from the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools expenditures and reports (https://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm) by searching the first and last name of each full-time faculty member along with their affiliated institution. The search results were filtered to only include NIH funding for full-time faculty members listed as principal investigators rather than as coinvestigators. The fiscal year total cost by institute/center for each full-time faculty member’s projects was summated to obtain the total NIH funding for the program.

The total number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014 was obtained utilizing a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using each faculty member’s first and last name. The authors’ affiliations were verified for each publication, and the number of publications was summed for all full-time faculty members at each residency program. If multiple authors from the same program coauthored an article, it was only counted once toward the total number of faculty publications from that program.

Program brochures for the 2014 meetings of the 5 societies were reviewed to quantify the number of lectures given by full-time faculty members in each program.

Each residency program was assigned a score from 0 to 1.0 for each of the 4 factors of academic achievement analyzed. The program with the highest number of faculty publications was assigned a score of 1.0 and the program with the lowest number of publications was assigned a score of 0. The programs in between were subsequently assigned scores from 0 to 1.0 based on the number of publications as a percentage of the number of publications from the program with the most publications.

A weighted ranking scheme was used to rank residency programs based on the relative importance of each factor. There were 3 factors that were deemed to be the most reflective of academic achievement among dermatology residency programs: amount of NIH funding received in 2014, number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014, and number of faculty lectures given at society meetings in 2014; thus, these factors were given a weight of 1.0. The remaining factor— total number of full-time faculty members—was given a weight of 0.5. Values were totaled and programs were ranked based on the sum of these values. All quantitative analyses were performed using an electronic spreadsheet program.

Results

The overall ranking of the top 20 US dermatology residency programs in 2014 is presented in Table 1. The top 5 programs based on each of the 3 factors most reflective of academic achievement used in the weighted ranking algorithm are presented in Tables 2 through 4.

Comment

The ranking of US residency programs involves using data in an unbiased manner while also accounting for important subjective measures. In a 2015 survey of residency applicants (n=6285), the 5 most important factors for applicants in selecting a program were the program’s ability to prepare residents for future training or position, resident esprit de corps, faculty availability and involvement in teaching, depth and breadth of faculty, and variety of patients and clinical resources.3 However, these subjective measures are difficult to quantify in a standardized fashion. In its ranking of residency programs, the Doximity Residency Navigator utilizes surveys of current residents and recent alumni as well as nominations from board-certified Doximity members.1

One of the main issues in utilizing survey data to rank residency programs is the inherent bias that most residents and alumni possess toward their own program. Moreover, the question arises whether most residents, faculty members, or recent alumni of residency programs have sufficient knowledge of other programs to rank them in a well-informed manner.

Wu et al4 used data from 2004 to perform the first algorithmic ranking of US dermatology programs, which was based on publications in 2001 to 2004, the amount of NIH funding in 2004, DF grants in 2001 to 2004, faculty lectures delivered at national conferences in 2004, and number of full-time faculty members on the editorial boards of the top 3 US dermatology journals and the top 4 subspecialty journals. Aquino et al2 provided updated rankings that utilized a weighted algorithm to collect data from 2008 related to a number of factors, including annual amount of NIH and DF funding received, number of publications by full-time faculty members, number of faculty lectures given at 5 annual society meetings, and number of full-time faculty members who were on the editorial boards of 6 dermatology journals with the highest impact factors. The top 5 ranked programs based on the 2008 data were the University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, California); Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut); and Stanford University (Stanford, California).2

The current ranking algorithm is more indicative of a residency program’s commitment to research and scholarship, with an assumption that successful clinical training is offered. Leading researchers in the field also are usually known to be clinical experts, but the current data does not take into account the frequency, quality, or methodology of teaching provided to residents. Perhaps the most objective measure reflecting the quality of resident education would be American Board of Dermatology examination scores, but these data are not publically available. Additional factors such as the percentage of residents who received fellowship positions; diversity of the patient population; and number and extent of surgical, cosmetic, or laser procedures performed also are not readily available. Doximity provides board pass rates for each residency program, but these data are self-reported and are not taken into account in their rankings.1

The current study aimed to utilize publicly available data to rank US dermatology residency programs based on objective measures of academic achievement. A recent study showed that 531 of 793 applicants (67%) to emergency medicine residency programs were aware of the Doximity residency rankings.One-quarter of these applicants made changes to their rank list based on this data, demonstrating that residency rankings may impact applicant decision-making.5 In the future, the most accurate and unbiased rankings may be performed if each residency program joins a cooperative effort to provide more objective data about the training they provide and utilizes a standardized survey system for current residents and recent graduates to evaluate important subjective measures.

Conclusion

Based on our weighted ranking algorithm, the top 5 dermatology residency programs in 2014 were Harvard University (Boston, Massachusetts); University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, California); Stanford University (Stanford, California); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); and Emory University (Atlanta, Georgia).

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the program coordinators, full-time faculty members, program directors, and chairs who provided responses to our inquiries for additional information about their residency programs.

- Residency navigator 2017-2018. Doximity website. https://residency.doximity.com. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- Aquino LL, Wen G, Wu JJ. US dermatology residency program rankings. Cutis. 2014;94:189-194.

- Phitayakorn R, Macklin EA, Goldsmith J, et al. Applicants’ self-reported priorities in selecting a residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:21-26.

- Wu JJ, Ramirez CC, Alonso CA, et al. Ranking the dermatology programs based on measurements of academic achievement. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:3.

- Peterson WJ, Hopson LR, Khandelwal S. Impact of Doximity residency rankings on emergency medicine applicant rank lists [published online May 5, 2016]. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17:350-354.

- Residency navigator 2017-2018. Doximity website. https://residency.doximity.com. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- Aquino LL, Wen G, Wu JJ. US dermatology residency program rankings. Cutis. 2014;94:189-194.

- Phitayakorn R, Macklin EA, Goldsmith J, et al. Applicants’ self-reported priorities in selecting a residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:21-26.

- Wu JJ, Ramirez CC, Alonso CA, et al. Ranking the dermatology programs based on measurements of academic achievement. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:3.

- Peterson WJ, Hopson LR, Khandelwal S. Impact of Doximity residency rankings on emergency medicine applicant rank lists [published online May 5, 2016]. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17:350-354.

Practice Points

- Dermatology is not among the many hospital-based adult specialties that are routinely ranked annually by US News & World Report.

- In the current study, US dermatology residency programs were ranked based on various academic factors, including the number of full-time faculty members, amount of National Institutes of Health funding received in 2014, number of publications by full-time faculty members in 2014, and the number of faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies in 2014.

EHR Impact on Patient Experience

Delivering patient‐centered care is at the core of ensuring patient engagement and active participation that will lead to positive outcomes. Physician‐patient interaction has become an area of increasing focus in an effort to optimize the patient experience. Positive patient‐provider communication has been shown to increase satisfaction,[1, 2, 3, 4] decrease the likelihood of medical malpractice lawsuits,[5, 6, 7, 8] and improve clinical outcomes.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13] Specifically, a decrease in psychological symptoms such as anxiety and stress, as well as perception of physical symptoms have been correlated with improved communication.[9, 12] Furthermore, objective health outcomes, such as improvement in hypertension and glycosylated hemoglobin, have also been correlated with improved physician‐patient communication.[10, 11, 13] The multifaceted effects of improved communication are impactful to both the patient and the physician; therefore, it is essential that we understand how to optimize this interaction.

Patient‐centered care is a critical objective for many high‐quality healthcare systems.[14] In recent years, the use of electronic health records (EHRs) has been increasingly adopted by healthcare systems nationally in an effort to improve the quality of care delivered. The positive benefits of EHRs on the facilitation of healthcare, including consolidation of information, reduction of medical errors, easily transferable medical records,[15, 16, 17] as well as their impact on healthcare spending,[18] are well‐documented and have been emphasized as reasons for adoption of EHRs by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. However, EHR implementation has encountered some resistance regarding its impact on the patient experience.

As EHR implementation is exponentially increasing in the United States, there is limited literature on the consequences of this technology.[19] Barriers reported during EHR implementation include the limitations of standardization, attitudinal and organizational constraints, behavior of individuals, and resistance to change.[20] Additionally, poor EHR system design and improper use can cause errors that jeopardize the integrity of the information inputted, leading to inaccuracies that endanger patient safety or decrease the quality of care.[21]

One of the limitations of EHRs has been the reported negative impact on patient‐centered care by decreasing communication during the hospital visit.[22] Although the EHR has enhanced internal provider communication,[23] the literature suggests a lack of focus on the patient sitting in front of the provider. Due to perceived physician distraction during the visit, patients report decreased satisfaction when physicians spend a considerable period of time during the visit at the computer.[22] Furthermore, the average hospital length of stay has been increased due to the use of EHRs.[22]

Although some physicians report that EHR use impedes patient workflow and decreases time spent with patients,[23] previous literature suggests that EHRs decrease the time to develop a synopsis and improve communication efficiency.[19] Some studies have also noted an increase in the ability for medical history retrieval and analysis, which will ultimately increase the quality of care provided to the patient.[24] Physicians who use the EHR adopted a more active role in clarifying information, encouraging questions, and ensuring completeness at the end of a visit.[25] Finally, studies show that the EHR has a positive return on investment from savings in drug expenditures, radiology tests, and billing errors.[26] Given the significant financial and time commitment that health systems and physicians must invest to implement EHRs, it is vital that we understand the multifaceted effects of EHRs on the field of medicine.

METHODS

The purpose of this study was to assess the physician‐patient communication patterns associated with the implementation and use of an EHR in a hospital setting.

ARC Medical Program

In 2006, the Office of Patient Experience at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Health, in conjunction with the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, launched the Assessing Residents' CI‐CARE (ARC) Medical Program. CI‐CARE is a protocol that emphasizes for medical staff and providers to Connect with their patients, Introduce themselves, Communicate their purpose, Ask or anticipate patients' needs, Respond to questions with immediacy, and to Exit courteously. CI‐CARE represents the standards for staff and providers in any encounter with patients or their families. The goals of the ARC Medical Program are to monitor housestaff performance and patient satisfaction while improving trainee education through timely and patient‐centered feedback. The ARC Medical Program's survey has served as an important tool to assess and improve physician professionalism and interpersonal skills and communication, 2 of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies.[27]

The ARC program is a unique and innovative volunteer program that provides timely and patient‐centered feedback from trainees' daily encounters with hospitalized patients. The ARC Medical Program has an established infrastructure to conduct evaluations on a system‐wide scale, including 9 departments within UCLA Health. ARC volunteers interview patients using a CI‐CARE Questionnaire (ARC survey) to assess their resident physician's communication patterns. The ARC Survey targets specific areas of the residents' care as outlined by the CI‐CARE Program of UCLA Health.

As part of UCLA Health's mission to ensure the highest level of patient‐centered care, the CI‐CARE standards were introduced in 2006, followed by implementation of the EHR system. Given the lack of previous research and conflicting results on the impact of EHRs on the patient experience, this article uses ARC data to assess whether or not there was a significant difference following implementation of the EHR on March 2, 2013.

The materials and methods of this study are largely based on those of a previous study, also published by the ARC Medical Program.[27]

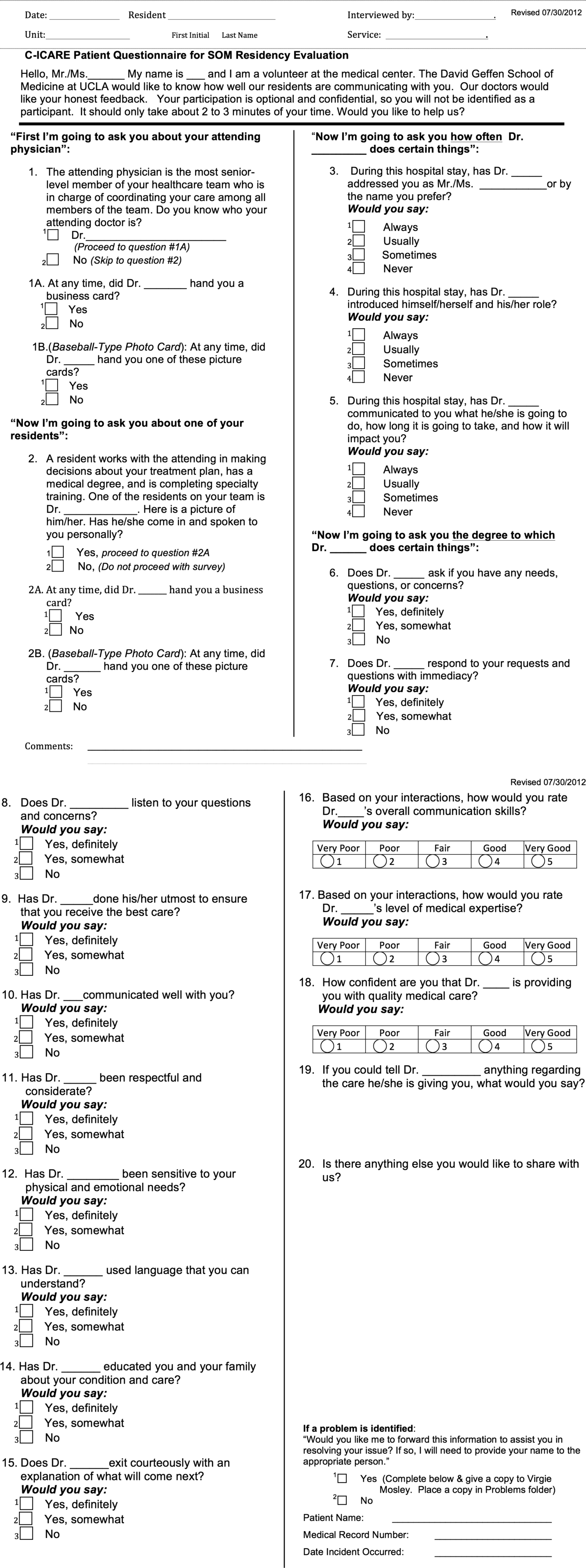

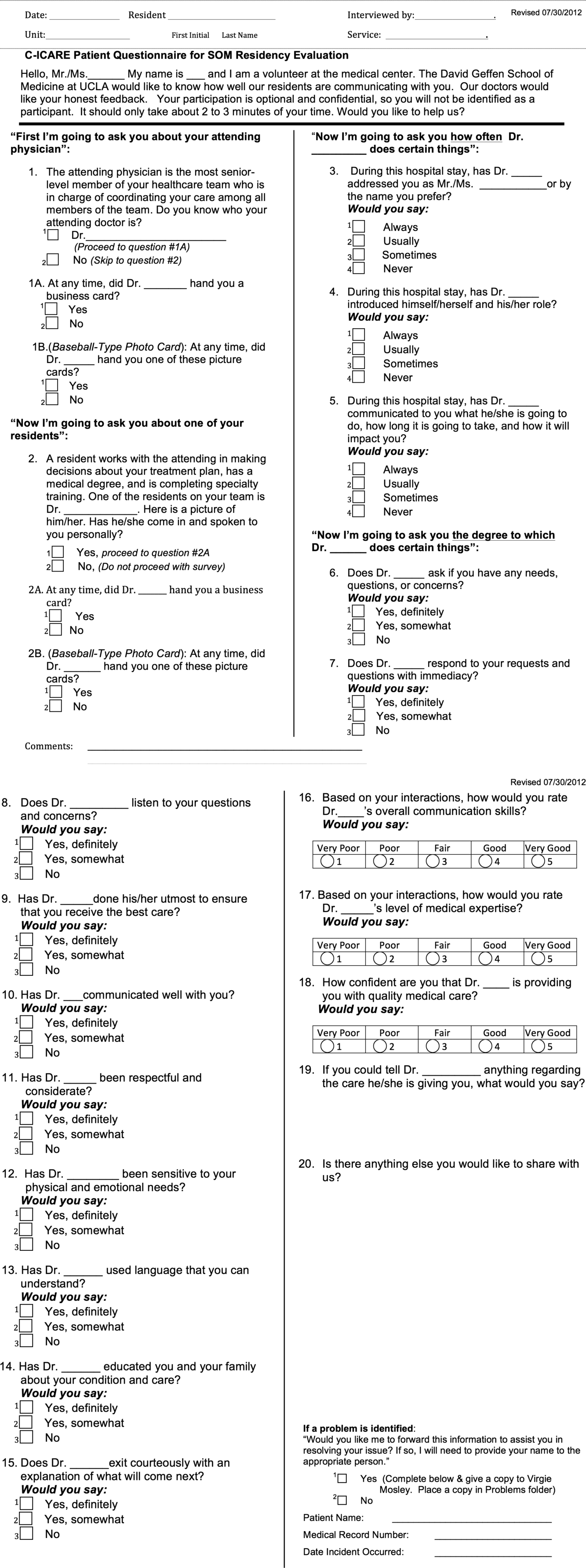

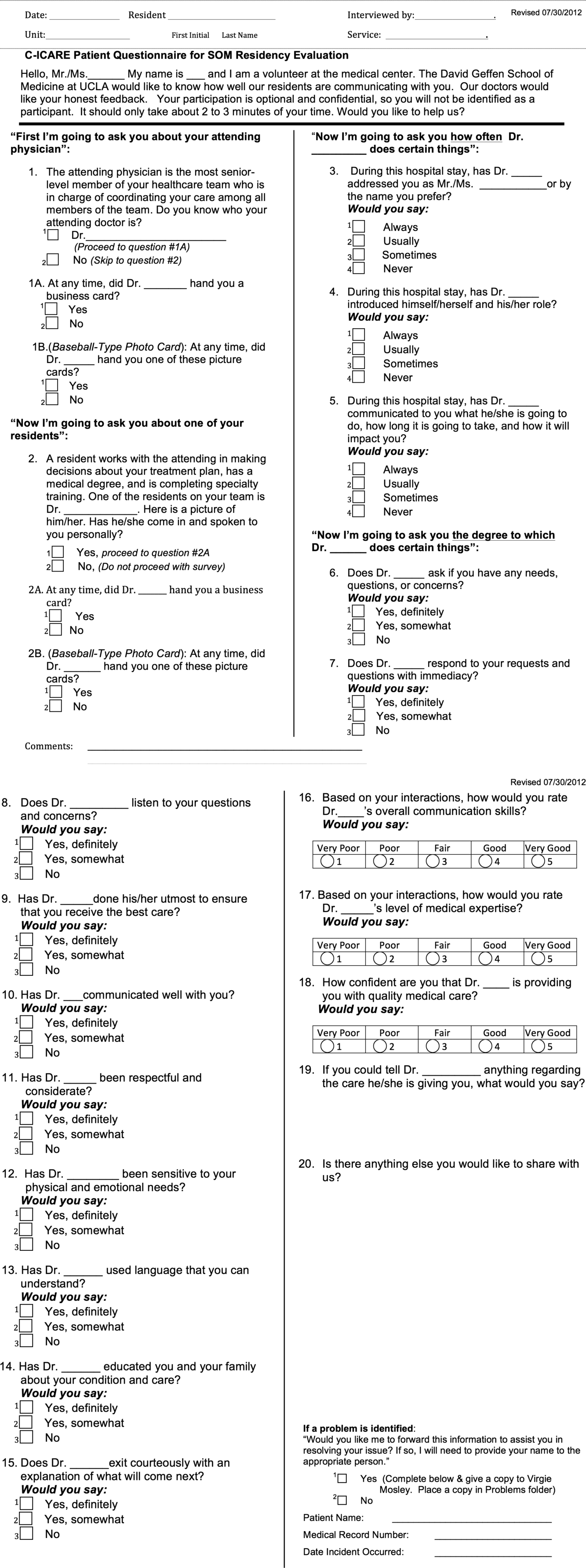

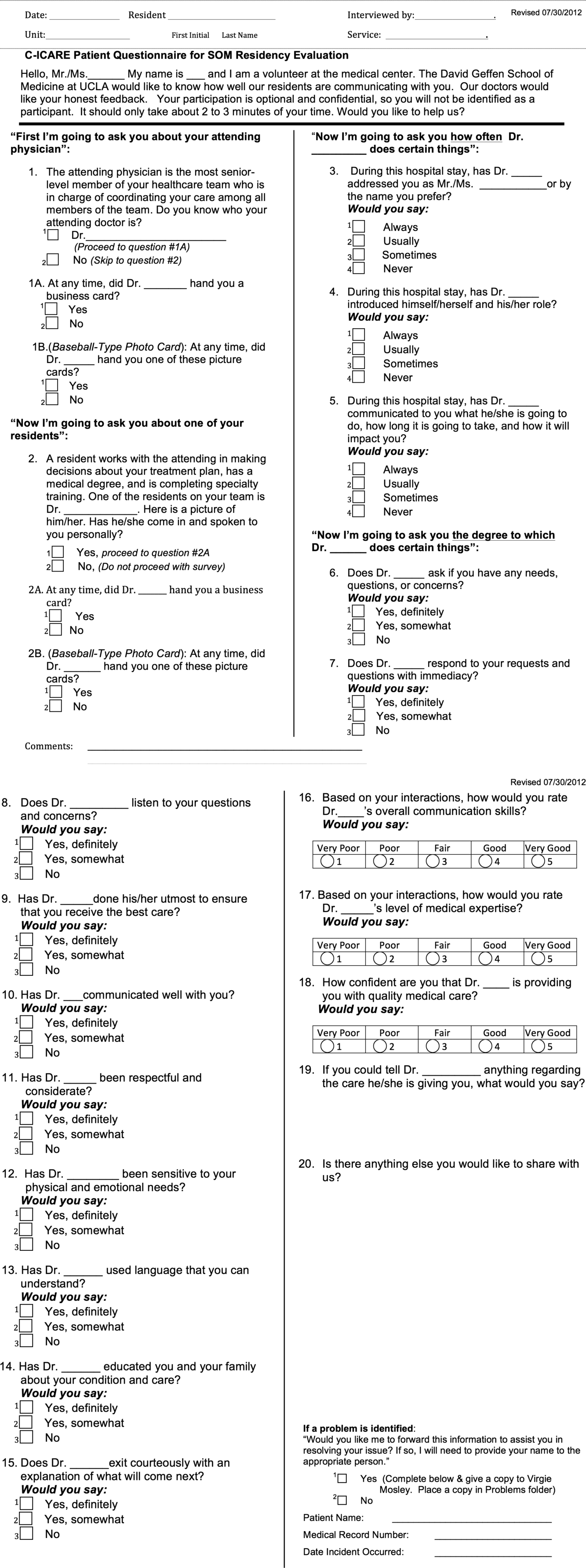

CI‐CARE QuestionnaireARC Survey

The CI‐CARE Questionnaire is a standardized audit tool consisting of a total of 20 questions used by the facilitators who work with ARC. There are a total of 20 items on the ARC survey, including 18 multiple‐choice, polar, and Likert‐scale questions, and 2 free‐response questions that assess the patients' overall perception of their resident physician and their hospital experience. Questions 1 and 2 pertain to the recognition of attending physicians and resident physicians, respectively. Questions 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 are Likert‐scalebased questions assessing the residents' professionalism. Questions 9 through 14 are Likert‐scalebased items included to evaluate the quality of communication between patient and provider. We categorized questions 5 and 15 as relating to diagnostics.[27] In 2012, ARC implemented 3 additional questions that assessed residents' communication skills (question 16), level of medical expertise (question 17), and quality of medical care (question 18). We chose to examine the CI‐CARE Questionnaire instead of a standard survey such as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), because it examines the physician‐patient interaction in more detail. The survey can be reviewed in Figure 1.

Interview Procedure

The ARC Medical Program is comprised of 47 premedical UCLA students who conducted the surveys. New surveyors were trained by the senior surveyors for a minimum of 12 hours before conducting a survey independently. All surveyors were evaluated biyearly by their peers and the program director for quality assurance and to ensure uniform procedures. The volunteers' surveying experience on December 1, 2012 was as follows: (=10 months [237 months], =10 months).

Prior to the interview, the surveyor introduces himself or herself, the purpose and length of the interview, and that the patient's anonymous participation is optional and confidential. Upon receiving verbal consent from the patient, the surveyor presents a picture card to the patient and asks him or her to identify a resident who was on rotation who treated them. If the patient is able to identify the resident who treated them, the surveyor asks each question and records each response verbatim. The surveyors are trained not to probe for responses, and to ensure that the patients answer in accordance with the possible responses. Although it has not been formally studied, the inter‐rater reliability of the survey is likely to be very high due to the verbatim requirements.

Population Interviewed

A total of 3414 surveys were collected from patients seen in the departments of internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, general surgery, head and neck surgery, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, neurology, and obstetrics and gynecology in this retrospective cohort study. Exclusion criteria included patients who were not awake, were not conscious, could not confidently identify a resident, or stated that they were not able to confidently complete the survey.

Data Analysis

The researchers reviewed and evaluated all data gathered using standard protocols. Statistical comparisons were made using [2] tests. All quantitative analyses were performed in Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Institutional Review Board

This project received an exemption by the UCLA institutional review board.

RESULTS

There were a total of 3414 interviews conducted and completed from December 1, 2012 to May 30, 2013. Altogether, 1567 surveys were collected 3 months prior to EHR implementation (DecemberFebruary), and 1847 surveys were collected 3 months following implementation (MarchMay). The survey breakdown is summarized in Table 1.

| Department | Pre (N) | Post (N) | Total (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Family medicine | 65 | 128 | 193 |

| General surgery | 226 | 246 | 472 |

| Head and neck surgery | 43 | 65 | 108 |

| Internal medicine | 439 | 369 | 808 |

| Neurology | 81 | 98 | 179 |

| Neurosurgery | 99 | 54 | 153 |

| OB/GYN | 173 | 199 | 372 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 117 | 128 | 245 |

| Pediatrics | 324 | 563 | 887 |

| Totals | 1,567 | 1,850 | 3,417 |

2 analysis revealed that the residents received significantly better feedback in the 3 months following EHR implementation, compared to the 3 months prior to implementation on questions 3, addressing the patient by their preferred name; 4, introducing themselves and their role; 5, communicating what they will do, how long it will take, and how it will impact the patient; 7, responding to the patient's requests and questions with immediacy; 8, listening to the patient's questions and concerns; 9, doing their utmost to ensure the patient receives the best care; 10, communicating well with the patient; 11, being respectful and considerate; and 12, being sensitive to the patient's physical and emotional needs (P<0.05) (Table 2).

| Question | Pre‐EHR % Responses (n=1,567) | Post‐EHR % Responses (n=1,850) | 2 Significance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| ||||||||||||

| 3 | Address you by preferred name? | 90.1 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 91.5 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 0.032* | ||

| 4 | Introduce himself/herself? | 88.3 | 6.4 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 93.1 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.000* | ||

| 5 | Communicate what he/she will do? | 83.1 | 9.3 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 86.9 | 6.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 0.006* | ||

| 6 | Ask if you have any questions? | 90.9 | 6.2 | 2.9 | 92.4 | 4.9 | 2.7 | 0.230 | ||||

| 7 | Respond with immediacy? | 92.5 | 5.4 | 2.2 | 94.6 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 0.015* | ||||

| 8 | Listens to your questions and concerns? | 94.8 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 96.6 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.022* | ||||

| 9 | Ensure you received the best care? | 92.4 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 95.2 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 0.003* | ||||

| 10 | Communicates well with you? | 92.3 | 6.3 | 1.5 | 94.8 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.009* | ||||

| 11 | Is respectful and considerate? | 96.5 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 98.0 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.025* | ||||

| 12 | Sensitive to your physical and emotional needs? | 90.4 | 6.9 | 2.7 | 94.5 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 0.000* | ||||

| 13 | Uses language that you can understand? | 96.5 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 96.9 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 0.431 | ||||

| 14 | Educated you/family about condition/care? | 84.0 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 86.6 | 7.4 | 6.0 | 0.111 | ||||

| 15 | Exit courteously? | 89.7 | 6.6 | 3.6 | 91.7 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 0.130 | ||||

| 16 | Communication skills? | 75.6 | 19.5 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 78.6 | 16.9 | 3.9 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.077 |

| 17 | Medical expertise? | 79.5 | 15.9 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 80.0 | 16.5 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.398 |

| 18 | Quality medical care? | 82.5 | 13.0 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 82.6 | 13.6 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.754 |

ARC surveyed for 10 weeks prior to our reported sample (OctoberDecember) and 22 weeks prior to EHR implementation total (OctoberMarch). To rule out resident improvement due to the confounding effects of time and experience, we compared the data from the first 11 weeks (OctoberDecember) to the second 11 weeks (DecemberMarch) prior to EHR implementation. [2] analysis revealed that only 6 of the 16 questions showed improvement in this period, and just 1 of these improvements (question 3) was significant. Furthermore, 10 of the 16 questions actually received worse responses in this period, and 2 of these declines (questions 9 and 12) were significant (Table 3).

| Question | First 11 Weeks' Responses (n=897) | Second 11 Weeks' Responses (n=1,338) | 2 Significance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| ||||||||||||

| 3 | Address you by preferred name? | 87.1 | 6.4 | 4.6 | 2.0 | 90.7 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 0.000* | ||

| 4 | Introduce himself/herself? | 87.7 | 6.9 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 88.3 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 0.174 | ||

| 5 | Communicate what he/she will do? | 82.9 | 8.2 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 83.2 | 9.1 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 0.698 | ||

| 6 | Ask if you have any questions? | 92.0 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 90.7 | 6.1 | 3.1 | 0.336 | ||||

| 7 | Respond with immediacy? | 91.2 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 92.8 | 5.2 | 2.1 | 0.353 | ||||

| 8 | Listens to your questions and concerns? | 94.6 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 95.0 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 0.868 | ||||

| 9 | Ensure you received the best care? | 94.4 | 5.0 | 0.6 | 92.1 | 6.5 | 1.4 | 0.049* | ||||

| 10 | Communicates well with you? | 93.3 | 5.9 | 0.8 | 92.4 | 5.9 | 1.7 | 0.167 | ||||

| 11 | Is respectful and considerate? | 97.3 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 96.4 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.455 | ||||

| 12 | Sensitive to your physical and emotional needs? | 93.2 | 5.5 | 1.3 | 90.3 | 6.9 | 2.8 | 0.022* | ||||

| 13 | Uses language that you can understand? | 96.2 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 96.4 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 0.327 | ||||

| 14 | Educated you/family about condition/care? | 85.7 | 8.9 | 5.4 | 83.8 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 0.141 | ||||

| 15 | Exit courteously? | 89.7 | 7.8 | 2.5 | 89.6 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 0.124 | ||||

| 16 | Communication skills? | 78.7 | 17.1 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 75.9 | 19 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.633 |

| 17 | Medical expertise? | 82.3 | 13.3 | 3.9 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 78.9 | 16.1 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.062 |

| 18 | Quality medical care? | 82.7 | 13.5 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 82.1 | 13.0 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.456 |

DISCUSSION

The adoption of EHRs has been fueled by their suggested improvement on healthcare quality and spending.[15, 16, 17, 18] Few studies have investigated the patient experience and its relation to EHR implementation. Furthermore, these studies have not yielded consistent results,[19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25] raising uncertainty about the effects of EHRs on the patient experience. Possible barriers that may contribute to the scarcity of literature include the relatively recent large‐scale implementation of EHRs and a lack of programs in place to collect extensive data on the physician‐patient relationship.

In a field with increasing demands on patient‐centered care, we need to find ways to preserve and foster the patient‐physician relationship. Given that improvements in the delivery of compassionate care can positively impact clinical outcomes, the likelihood of medical malpractice lawsuits, and patient satisfaction,[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] the need to improve the patient‐provider relationship is tremendously important. Following EHR implementation, residents were perceived to provide more frequent diagnostics information including the nature, impact, and treatment of conditions. Furthermore, they were perceived to provide significantly better communication quality following implementation, through care monitoring, respectful and sensitive communication, and enhanced patient and family education. Residents were also perceived as being more professional following implementation, as indicated by positive assessments of several interpersonal communication questions. These results suggest that implementing an EHR may be an effective way to meet these increasing demands on patient‐centered care.

Limitations to this study should be considered. The ARC Medical Program is primarily used as an education tool for resident physicians, so all of our data are specific to resident physicians. It would be interesting and important to observe if EHRs affect nurse or attending‐patient interactions. Furthermore, we did not have access to any patient demographic or clinical data. However, we did not anticipate a significant change in the patient population that would alter the survey responses during this 6‐month period. Patients were required to recognize their resident on a photo card presented to them by the surveyor, which likely favored patients with strong feelings toward their residents. Due to this, our population sampled may not be indicative of the entire patient population. All findings were simply correlational. Due to the nature of our data collection, we were unable to control for many confounding variables, thus causal conclusions are difficult to draw from these results.

There are a few important trends to note. No question on the ARC survey received lower scores following implementation of the EHR. Furthermore, 9 of the 16 questions under investigation received significantly higher scores following implementation. The residents largely received positive responses both before and after EHR implementation, so despite the statistically significant improvements, the absolute differences are relatively small. These significant differences were likely not due to the residents improving through time and experience. We observed relatively insignificant and nonuniform changes in responses between the two 11‐week periods prior to implementation.

One possible reason for the observed significant improvements is that EHRs may increase patient involvement in the healthcare setting,[28] and this collaboration might improve resident‐patient communication.[29] Providing patients with an interactive tablet that details their care has been suggested to increase patient satisfaction and comfort in an inpatient setting.[30] In this light, the EHR can be used as a tool to increase these interactions by inviting patients to view the computer screen and electronic charts during data entry, which allows them to have a participatory role in their care and decision‐making process.[31] Although the reasons for our observed improvements are unclear, they are noteworthy and warrant further study. The notion that implementing an EHR might enhance provider‐patient communication is a powerful concept.

This study not only suggests the improvement of resident‐patient communication due to the implementation of an EHR, but it also reveals the value of the ARC Medical Program for studying the patient experience. The controlled, prolonged, and efficient nature of the ARC Medical Program's data collection was ideal for comparing a change in resident‐patient communication before and after EHR implementation at UCLA Health. ARC and UCLA Health's EHR can serve as a model for residency programs nationwide. Future studies can assess the changes of the patient‐provider interaction for any significant event, as demonstrated by this study and its investigation of the implementation of UCLA Health's EHR.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the UCLA Health Office of the Patient Experience and UCLA Health for allowing for this unique partnership with the David Geffen School of Medicine to improve physician‐patient communication. Furthermore, the authors thank the student volunteers and interns of the ARC Medical program for their commitment and effort to optimize the patient experience. Additionally, the authors thank the program directors of the David Geffen School of Medicine residency physician training programs for their outstanding support of the ARC Medical Program.

Disclosures: C.W.M. and A.A.N. contributed equally to this manuscript. C.W.M. and A.A.N. collected data, performed statistical analyses, and drafted and revised the manuscript. A.A.N. and V.N.M. oversaw the program. N.A. provided faculty support and revised the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Doctor‐patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Pract. 1998;15(5):480–492.

- . Patient satisfaction in primary health care: a literature review and analysis. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6:185–210.

- , . The significance of patients' perceptions of physician conduct. J Community Health. 1980;6(1):18–34.

- , , , . Predicting patient satisfaction from physicians' nonverbal communication skills. Med Care. 1980;18(4):376–387.

- , , . Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives. Lancet. 1994;343:1609–1613.

- , , . Reducing legal risk by practicing patient‐centered medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(11):1217–1219.

- , . Listening and talking. West J Med. 1993;158:268–272.

- , , . Medical malpractice: the effect of doctor‐patient relations on medical patient perceptions and malpractice intentions. West J Med. 2000;173(4):244–250.

- . Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423–1433.

- , , , , . Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Intern Med. 1988;3:448–457.

- , , . Assessing the effects of physician‐patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27(3 suppl):S110–S127.

- , , . Expanding patient involvement in care. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–528.

- , , , , . Patient exposition and provider explanation in routine interviews and hypertensive patients' blood control. Health Psychol. 1987;6(1):29–42.

- , , . A framework for making patient‐centered care front and center. Perm J. 2012;16(3):49–53.

- . Interoperability: the key to the future health care system. Health Aff. 2005;5(21):19–21.

- , . Physicians' use of electronic medical records: barriers and solutions. Health Aff. 2004;23(2):116–126.

- , . Do hospitals with electronic medical records (EMRs) provide higher quality care?: an examination of three clinical conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(4):496–513.

- , , , et al. Can electronic medical record systems transform health care? Potential health benefits, savings, and costs. Health Aff. 2005;24(5):1103–1117.

- , , , . An electronic medical record in primary care: impact on satisfaction, work efficiency and clinic processes. AMIA Annu Symp.2006:394–398.

- , . Barriers to implement electronic health records (EHRs). Mater Sociomed. 2013;25(3):213–215.

- . Impact of electronic health record systems on information integrity: quality and safety implications. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2013;10:1c.eCollection 2013.

- , , , , . Electronic medical record use and physician–patient communication: an observational study of Israeli primary care encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:134–141.

- , , , et al. EHR implementation in a new clinic: a case study of clinician perceptions. J Med Syst. 2013;37(9955):1–6.

- , , . Accuracy and speed of electronic health record versus paper‐based ophthalmic documentation strategies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(1):165–172.

- , , . The use of electronic medical records communication patterns in outpatient encounters. J Am Informatics Assoc. 2001:610–616.

- , , . Cost‐benefit analysis of electronic medical record system at a tertiary care hospital. Healthc Inform Res. 2013;19(3):205–214.

- , , , . Promoting patient‐centred care through trainee feedback: assessing residents' C‐I‐CARE (ARC) program. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(3):225–233.

- . Electronic health records?: can we maximize their benefits and minimize their risks? Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1456–1457.

- , . Let the left hand know what the right is doing: a vision for care coordination and electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(1):13–16.

- , , , et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428–1435.

- , . Enhancing patient‐centered communication and collaboration by using the electronic health record in the examination room. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309(22):2327–2328.

Delivering patient‐centered care is at the core of ensuring patient engagement and active participation that will lead to positive outcomes. Physician‐patient interaction has become an area of increasing focus in an effort to optimize the patient experience. Positive patient‐provider communication has been shown to increase satisfaction,[1, 2, 3, 4] decrease the likelihood of medical malpractice lawsuits,[5, 6, 7, 8] and improve clinical outcomes.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13] Specifically, a decrease in psychological symptoms such as anxiety and stress, as well as perception of physical symptoms have been correlated with improved communication.[9, 12] Furthermore, objective health outcomes, such as improvement in hypertension and glycosylated hemoglobin, have also been correlated with improved physician‐patient communication.[10, 11, 13] The multifaceted effects of improved communication are impactful to both the patient and the physician; therefore, it is essential that we understand how to optimize this interaction.

Patient‐centered care is a critical objective for many high‐quality healthcare systems.[14] In recent years, the use of electronic health records (EHRs) has been increasingly adopted by healthcare systems nationally in an effort to improve the quality of care delivered. The positive benefits of EHRs on the facilitation of healthcare, including consolidation of information, reduction of medical errors, easily transferable medical records,[15, 16, 17] as well as their impact on healthcare spending,[18] are well‐documented and have been emphasized as reasons for adoption of EHRs by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. However, EHR implementation has encountered some resistance regarding its impact on the patient experience.

As EHR implementation is exponentially increasing in the United States, there is limited literature on the consequences of this technology.[19] Barriers reported during EHR implementation include the limitations of standardization, attitudinal and organizational constraints, behavior of individuals, and resistance to change.[20] Additionally, poor EHR system design and improper use can cause errors that jeopardize the integrity of the information inputted, leading to inaccuracies that endanger patient safety or decrease the quality of care.[21]

One of the limitations of EHRs has been the reported negative impact on patient‐centered care by decreasing communication during the hospital visit.[22] Although the EHR has enhanced internal provider communication,[23] the literature suggests a lack of focus on the patient sitting in front of the provider. Due to perceived physician distraction during the visit, patients report decreased satisfaction when physicians spend a considerable period of time during the visit at the computer.[22] Furthermore, the average hospital length of stay has been increased due to the use of EHRs.[22]

Although some physicians report that EHR use impedes patient workflow and decreases time spent with patients,[23] previous literature suggests that EHRs decrease the time to develop a synopsis and improve communication efficiency.[19] Some studies have also noted an increase in the ability for medical history retrieval and analysis, which will ultimately increase the quality of care provided to the patient.[24] Physicians who use the EHR adopted a more active role in clarifying information, encouraging questions, and ensuring completeness at the end of a visit.[25] Finally, studies show that the EHR has a positive return on investment from savings in drug expenditures, radiology tests, and billing errors.[26] Given the significant financial and time commitment that health systems and physicians must invest to implement EHRs, it is vital that we understand the multifaceted effects of EHRs on the field of medicine.

METHODS

The purpose of this study was to assess the physician‐patient communication patterns associated with the implementation and use of an EHR in a hospital setting.

ARC Medical Program