User login

Hypertension in older adults: What is the target blood pressure?

We should aim for a standard office systolic pressure lower than 130 mm Hg in most adults age 65 and older if the patient can take multiple antihypertensive medications and be followed closely for adverse effects.

This recommendation is part of the 2017 hypertension guideline from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.1 This new guideline advocates drug treatment of hypertension to a target less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients of all ages for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and for primary prevention in those at high risk (ie, an estimated 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease of 10% or higher). The target blood pressure for those at lower risk is less than 140/90 mm Hg.

There are multiple tools to estimate the 10-year risk. All tools incorporate major predictors such as age, blood pressure, cholesterol profile, and other markers, depending on the tool. Although risk increases with age, the tools are inaccurate once the patient is approximately 80 years of age.

The recommendation for older adults omits a target diastolic pressure, since treating elevated systolic pressure has more data supporting it than treating elevated diastolic blood pressure in older people. These recommendations apply only to older adults who can walk and are living in the community, not in an institution, and includes the subset of older adults who have mild cognitive impairment and frailty. The goals of treatment should be patient-centered.

DATA BEHIND THE GUIDELINE: THE SPRINT TRIAL

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT)2 enrolled 9,361 patients who, to enter, had to be at least 50 years old (the mean age was 67.9), have a systolic blood pressure of 130 to 180 mm Hg (the mean was 139.7 mm Hg), and be at risk of cardiovascular disease due to chronic kidney disease, clinical or subclinical cardiovascular disease, a 10-year Framingham risk score of at least 15%, or age 75 or older. They had few comorbidities, and patients with diabetes mellitus or prior stroke were excluded. The objective was to see if intensive blood pressure treatment reduced the incidence of adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with standard control.

The participants were randomized to either an intensive treatment goal of systolic pressure less than 120 mm Hg or a standard treatment goal of less than 140 mm Hg. Investigators chose drugs and doses according to their clinical judgment. The study protocol called for blood pressure measurement using an untended automated cuff, which probably resulted in systolic pressure readings 5 to 10 mm Hg lower than with typical methods used in the office.3

The intensive treatment group achieved a mean systolic pressure of 121.5 mm Hg, which required an average of 3 drugs. In contrast, the standard treatment group achieved a systolic pressure of 136.2 mm Hg, which required an average of 1.9 drugs.

Due to an absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular events and mortality, SPRINT was discontinued early after a median follow-up of 3.3 years. In the entire cohort, 61 patients needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 cardiovascular event, and 90 needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 death.2

Favorable outcomes in the oldest subgroup

The oldest patients in the SPRINT trial tolerated the intensive treatment as well as the youngest.2,4

Exploratory analysis of the subgroup of patients age 75 and older, who constituted 28% of the patients in the trial, demonstrated significant benefit from intensive treatment. In this subgroup, 27 patients needed to be treated aggressively (compared with standard treatment) to prevent 1 cardiovascular event, and 41 needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 death.4 The lower numbers needing to be treated in the older subgroup than in the overall trial reflect the higher absolute risk in this older population.

Serious adverse events were more common with intensive treatment than with standard treatment in the subgroup of older patients who were frail.4 Emergency department visits or serious adverse events were more likely when gait speed (a measure of frailty) was missing from the medical record in the intensive treatment group compared with the standard treatment group. Hyponatremia (serum sodium level < 130 mmol/L) was more likely in the intensively treated group than in the standard treatment group. Although the rate of falls was higher in the oldest subgroup than in the overall SPRINT population, within this subgroup the rate of injurious falls resulting in an emergency department visit was lower with intensive treatment than with standard treatment (11.6% vs 14.1%, P = .04).4

Most of the oldest patients scored below the nominal cutoff for normal (26 points)5 on the 30-point Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and about one-quarter scored below 19, which may be consistent with a major neurocognitive disorder.6

The SPRINT investigators validated a frailty scale in the study patients and found that the most frail benefited from intensive blood pressure control, as did the slowest walkers.

SPRINT results do not apply to very frail, sick patients

For older patients with hypertension, a high burden of comorbidity, and a limited life expectancy, the 2017 guidelines defer treatment decisions to clinical judgment and patient preference.

There have been no randomized trials of blood pressure management for older adults with substantial comorbidities or dementia. The “frail” older adults in the SPRINT trial were still living in the community, without dementia. The intensively treated frail older adults had more serious adverse events than with standard treatment. Those who were documented as being unable to walk at the time of enrollment also had more serious adverse events. Institutionalized older adults and nonambulatory adults in the community would likely have even higher rates of serious adverse events with intensive treatment than the SPRINT patients, and there is concern for excessive adverse effects from intensive blood pressure control in more debilitated older patients.

DOES TREATING HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE PREVENT FRAILTY OR DEMENTIA?

Aging without frailty is an important goal of geriatric care and is likely related to cardiovascular health.7 An older adult who becomes slower physically or mentally, with diminished strength and energy, is less likely to be able to live independently.

Would treating systolic blood pressure to a target of 120 to 130 mm Hg reduce the risk of prefrailty or frailty? Unfortunately, the 3-year SPRINT follow-up of the adults age 75 and older did not show any effect of intensive treatment on gait speed or mobility limitation.8 It is possible that the early termination of the study limited outcomes.

Regarding cognition, the new guidelines say that lowering blood pressure in adults with hypertension to prevent cognitive decline and dementia is reasonable, giving it a class IIa (moderate) recommendation, but they do not offer a particular blood pressure target.

Two systematic reviews of randomized placebo-controlled trials9,10 suggested that pharmacologic treatment of hypertension reduces the progression of cognitive impairment. The trials did not use an intensive treatment goal.

The impact of intensive treatment of hypertension (to a target of 120–130 mm Hg) on the development or progression of cognitive impairment is not known at this time. The SPRINT Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension analysis may shed light on the effect of intensive treatment of blood pressure on the incidence of dementia, although the early termination of SPRINT may limit its conclusions as well.

GOALS SHOULD BE PATIENT-CENTERED

The new hypertension guideline gives clinicians 2 things to think about when treating hypertensive, ambulatory, noninstitutionalized, nondemented older adults, including those age 75 and older:

- Older adults tolerate intensive blood pressure treatment as well as standard treatment. In particular, the fall rate is not increased and may even be less with intensive treatment.

- Older adults have better cardiovascular outcomes with blood pressure less than 130 mm Hg than with higher levels.

Adherence to the new guidelines would require many older adults without significant multimorbidity to take 3 drugs and undergo more frequent monitoring. This burden may align with the goals of care for many older adults. However, data do not exist to prove a benefit from intensive blood pressure control in debilitated elderly patients, and there may be harm. Lowering the medication burden may be a more important goal than lowering the pressure for this population. Blood pressure targets and hypertension management should reflect patient-centered goals of care.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017. Epub ahead of print.

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2103–2116.

- Bakris GL. The implications of blood pressure measurement methods on treatment targets for blood pressure. Circulation 2016; 134:904–905.

- Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al; SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315:2673–2682.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:695–699.

- Borland E, Nagga K, Nilsson PM, Minthon L, Nilsson ED, Palmqvist S. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: normative data from a large Swedish population-based cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 59:893–901.

- Graciani A, Garcia-Esquinas E, Lopez-Garcia E, Banegas JR, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Ideal cardiovascular health and risk of frailty in older adults. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016; 9:239–245.

- Odden MC, Peralta CA, Berlowitz DR, et al; Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) Research Group. Effect of intensive blood pressure control on gait speed and mobility limitation in adults 75 years or older: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:500–507.

- Tully PJ, Hanon O, Cosh S, Tzourio C. Diuretic antihypertensive drugs and incident dementia risk: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of prospective studies. J Hypertens 2016; 34:1027–1035.

- Rouch L, Cestac P, Hanon O, et al. Antihypertensive drugs, prevention of cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review of observational studies, randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, with discussion of potential mechanisms. CNS Drugs 2015; 29:113–130.

We should aim for a standard office systolic pressure lower than 130 mm Hg in most adults age 65 and older if the patient can take multiple antihypertensive medications and be followed closely for adverse effects.

This recommendation is part of the 2017 hypertension guideline from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.1 This new guideline advocates drug treatment of hypertension to a target less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients of all ages for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and for primary prevention in those at high risk (ie, an estimated 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease of 10% or higher). The target blood pressure for those at lower risk is less than 140/90 mm Hg.

There are multiple tools to estimate the 10-year risk. All tools incorporate major predictors such as age, blood pressure, cholesterol profile, and other markers, depending on the tool. Although risk increases with age, the tools are inaccurate once the patient is approximately 80 years of age.

The recommendation for older adults omits a target diastolic pressure, since treating elevated systolic pressure has more data supporting it than treating elevated diastolic blood pressure in older people. These recommendations apply only to older adults who can walk and are living in the community, not in an institution, and includes the subset of older adults who have mild cognitive impairment and frailty. The goals of treatment should be patient-centered.

DATA BEHIND THE GUIDELINE: THE SPRINT TRIAL

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT)2 enrolled 9,361 patients who, to enter, had to be at least 50 years old (the mean age was 67.9), have a systolic blood pressure of 130 to 180 mm Hg (the mean was 139.7 mm Hg), and be at risk of cardiovascular disease due to chronic kidney disease, clinical or subclinical cardiovascular disease, a 10-year Framingham risk score of at least 15%, or age 75 or older. They had few comorbidities, and patients with diabetes mellitus or prior stroke were excluded. The objective was to see if intensive blood pressure treatment reduced the incidence of adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with standard control.

The participants were randomized to either an intensive treatment goal of systolic pressure less than 120 mm Hg or a standard treatment goal of less than 140 mm Hg. Investigators chose drugs and doses according to their clinical judgment. The study protocol called for blood pressure measurement using an untended automated cuff, which probably resulted in systolic pressure readings 5 to 10 mm Hg lower than with typical methods used in the office.3

The intensive treatment group achieved a mean systolic pressure of 121.5 mm Hg, which required an average of 3 drugs. In contrast, the standard treatment group achieved a systolic pressure of 136.2 mm Hg, which required an average of 1.9 drugs.

Due to an absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular events and mortality, SPRINT was discontinued early after a median follow-up of 3.3 years. In the entire cohort, 61 patients needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 cardiovascular event, and 90 needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 death.2

Favorable outcomes in the oldest subgroup

The oldest patients in the SPRINT trial tolerated the intensive treatment as well as the youngest.2,4

Exploratory analysis of the subgroup of patients age 75 and older, who constituted 28% of the patients in the trial, demonstrated significant benefit from intensive treatment. In this subgroup, 27 patients needed to be treated aggressively (compared with standard treatment) to prevent 1 cardiovascular event, and 41 needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 death.4 The lower numbers needing to be treated in the older subgroup than in the overall trial reflect the higher absolute risk in this older population.

Serious adverse events were more common with intensive treatment than with standard treatment in the subgroup of older patients who were frail.4 Emergency department visits or serious adverse events were more likely when gait speed (a measure of frailty) was missing from the medical record in the intensive treatment group compared with the standard treatment group. Hyponatremia (serum sodium level < 130 mmol/L) was more likely in the intensively treated group than in the standard treatment group. Although the rate of falls was higher in the oldest subgroup than in the overall SPRINT population, within this subgroup the rate of injurious falls resulting in an emergency department visit was lower with intensive treatment than with standard treatment (11.6% vs 14.1%, P = .04).4

Most of the oldest patients scored below the nominal cutoff for normal (26 points)5 on the 30-point Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and about one-quarter scored below 19, which may be consistent with a major neurocognitive disorder.6

The SPRINT investigators validated a frailty scale in the study patients and found that the most frail benefited from intensive blood pressure control, as did the slowest walkers.

SPRINT results do not apply to very frail, sick patients

For older patients with hypertension, a high burden of comorbidity, and a limited life expectancy, the 2017 guidelines defer treatment decisions to clinical judgment and patient preference.

There have been no randomized trials of blood pressure management for older adults with substantial comorbidities or dementia. The “frail” older adults in the SPRINT trial were still living in the community, without dementia. The intensively treated frail older adults had more serious adverse events than with standard treatment. Those who were documented as being unable to walk at the time of enrollment also had more serious adverse events. Institutionalized older adults and nonambulatory adults in the community would likely have even higher rates of serious adverse events with intensive treatment than the SPRINT patients, and there is concern for excessive adverse effects from intensive blood pressure control in more debilitated older patients.

DOES TREATING HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE PREVENT FRAILTY OR DEMENTIA?

Aging without frailty is an important goal of geriatric care and is likely related to cardiovascular health.7 An older adult who becomes slower physically or mentally, with diminished strength and energy, is less likely to be able to live independently.

Would treating systolic blood pressure to a target of 120 to 130 mm Hg reduce the risk of prefrailty or frailty? Unfortunately, the 3-year SPRINT follow-up of the adults age 75 and older did not show any effect of intensive treatment on gait speed or mobility limitation.8 It is possible that the early termination of the study limited outcomes.

Regarding cognition, the new guidelines say that lowering blood pressure in adults with hypertension to prevent cognitive decline and dementia is reasonable, giving it a class IIa (moderate) recommendation, but they do not offer a particular blood pressure target.

Two systematic reviews of randomized placebo-controlled trials9,10 suggested that pharmacologic treatment of hypertension reduces the progression of cognitive impairment. The trials did not use an intensive treatment goal.

The impact of intensive treatment of hypertension (to a target of 120–130 mm Hg) on the development or progression of cognitive impairment is not known at this time. The SPRINT Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension analysis may shed light on the effect of intensive treatment of blood pressure on the incidence of dementia, although the early termination of SPRINT may limit its conclusions as well.

GOALS SHOULD BE PATIENT-CENTERED

The new hypertension guideline gives clinicians 2 things to think about when treating hypertensive, ambulatory, noninstitutionalized, nondemented older adults, including those age 75 and older:

- Older adults tolerate intensive blood pressure treatment as well as standard treatment. In particular, the fall rate is not increased and may even be less with intensive treatment.

- Older adults have better cardiovascular outcomes with blood pressure less than 130 mm Hg than with higher levels.

Adherence to the new guidelines would require many older adults without significant multimorbidity to take 3 drugs and undergo more frequent monitoring. This burden may align with the goals of care for many older adults. However, data do not exist to prove a benefit from intensive blood pressure control in debilitated elderly patients, and there may be harm. Lowering the medication burden may be a more important goal than lowering the pressure for this population. Blood pressure targets and hypertension management should reflect patient-centered goals of care.

We should aim for a standard office systolic pressure lower than 130 mm Hg in most adults age 65 and older if the patient can take multiple antihypertensive medications and be followed closely for adverse effects.

This recommendation is part of the 2017 hypertension guideline from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.1 This new guideline advocates drug treatment of hypertension to a target less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients of all ages for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and for primary prevention in those at high risk (ie, an estimated 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease of 10% or higher). The target blood pressure for those at lower risk is less than 140/90 mm Hg.

There are multiple tools to estimate the 10-year risk. All tools incorporate major predictors such as age, blood pressure, cholesterol profile, and other markers, depending on the tool. Although risk increases with age, the tools are inaccurate once the patient is approximately 80 years of age.

The recommendation for older adults omits a target diastolic pressure, since treating elevated systolic pressure has more data supporting it than treating elevated diastolic blood pressure in older people. These recommendations apply only to older adults who can walk and are living in the community, not in an institution, and includes the subset of older adults who have mild cognitive impairment and frailty. The goals of treatment should be patient-centered.

DATA BEHIND THE GUIDELINE: THE SPRINT TRIAL

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT)2 enrolled 9,361 patients who, to enter, had to be at least 50 years old (the mean age was 67.9), have a systolic blood pressure of 130 to 180 mm Hg (the mean was 139.7 mm Hg), and be at risk of cardiovascular disease due to chronic kidney disease, clinical or subclinical cardiovascular disease, a 10-year Framingham risk score of at least 15%, or age 75 or older. They had few comorbidities, and patients with diabetes mellitus or prior stroke were excluded. The objective was to see if intensive blood pressure treatment reduced the incidence of adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with standard control.

The participants were randomized to either an intensive treatment goal of systolic pressure less than 120 mm Hg or a standard treatment goal of less than 140 mm Hg. Investigators chose drugs and doses according to their clinical judgment. The study protocol called for blood pressure measurement using an untended automated cuff, which probably resulted in systolic pressure readings 5 to 10 mm Hg lower than with typical methods used in the office.3

The intensive treatment group achieved a mean systolic pressure of 121.5 mm Hg, which required an average of 3 drugs. In contrast, the standard treatment group achieved a systolic pressure of 136.2 mm Hg, which required an average of 1.9 drugs.

Due to an absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular events and mortality, SPRINT was discontinued early after a median follow-up of 3.3 years. In the entire cohort, 61 patients needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 cardiovascular event, and 90 needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 death.2

Favorable outcomes in the oldest subgroup

The oldest patients in the SPRINT trial tolerated the intensive treatment as well as the youngest.2,4

Exploratory analysis of the subgroup of patients age 75 and older, who constituted 28% of the patients in the trial, demonstrated significant benefit from intensive treatment. In this subgroup, 27 patients needed to be treated aggressively (compared with standard treatment) to prevent 1 cardiovascular event, and 41 needed to be treated intensively to prevent 1 death.4 The lower numbers needing to be treated in the older subgroup than in the overall trial reflect the higher absolute risk in this older population.

Serious adverse events were more common with intensive treatment than with standard treatment in the subgroup of older patients who were frail.4 Emergency department visits or serious adverse events were more likely when gait speed (a measure of frailty) was missing from the medical record in the intensive treatment group compared with the standard treatment group. Hyponatremia (serum sodium level < 130 mmol/L) was more likely in the intensively treated group than in the standard treatment group. Although the rate of falls was higher in the oldest subgroup than in the overall SPRINT population, within this subgroup the rate of injurious falls resulting in an emergency department visit was lower with intensive treatment than with standard treatment (11.6% vs 14.1%, P = .04).4

Most of the oldest patients scored below the nominal cutoff for normal (26 points)5 on the 30-point Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and about one-quarter scored below 19, which may be consistent with a major neurocognitive disorder.6

The SPRINT investigators validated a frailty scale in the study patients and found that the most frail benefited from intensive blood pressure control, as did the slowest walkers.

SPRINT results do not apply to very frail, sick patients

For older patients with hypertension, a high burden of comorbidity, and a limited life expectancy, the 2017 guidelines defer treatment decisions to clinical judgment and patient preference.

There have been no randomized trials of blood pressure management for older adults with substantial comorbidities or dementia. The “frail” older adults in the SPRINT trial were still living in the community, without dementia. The intensively treated frail older adults had more serious adverse events than with standard treatment. Those who were documented as being unable to walk at the time of enrollment also had more serious adverse events. Institutionalized older adults and nonambulatory adults in the community would likely have even higher rates of serious adverse events with intensive treatment than the SPRINT patients, and there is concern for excessive adverse effects from intensive blood pressure control in more debilitated older patients.

DOES TREATING HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE PREVENT FRAILTY OR DEMENTIA?

Aging without frailty is an important goal of geriatric care and is likely related to cardiovascular health.7 An older adult who becomes slower physically or mentally, with diminished strength and energy, is less likely to be able to live independently.

Would treating systolic blood pressure to a target of 120 to 130 mm Hg reduce the risk of prefrailty or frailty? Unfortunately, the 3-year SPRINT follow-up of the adults age 75 and older did not show any effect of intensive treatment on gait speed or mobility limitation.8 It is possible that the early termination of the study limited outcomes.

Regarding cognition, the new guidelines say that lowering blood pressure in adults with hypertension to prevent cognitive decline and dementia is reasonable, giving it a class IIa (moderate) recommendation, but they do not offer a particular blood pressure target.

Two systematic reviews of randomized placebo-controlled trials9,10 suggested that pharmacologic treatment of hypertension reduces the progression of cognitive impairment. The trials did not use an intensive treatment goal.

The impact of intensive treatment of hypertension (to a target of 120–130 mm Hg) on the development or progression of cognitive impairment is not known at this time. The SPRINT Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension analysis may shed light on the effect of intensive treatment of blood pressure on the incidence of dementia, although the early termination of SPRINT may limit its conclusions as well.

GOALS SHOULD BE PATIENT-CENTERED

The new hypertension guideline gives clinicians 2 things to think about when treating hypertensive, ambulatory, noninstitutionalized, nondemented older adults, including those age 75 and older:

- Older adults tolerate intensive blood pressure treatment as well as standard treatment. In particular, the fall rate is not increased and may even be less with intensive treatment.

- Older adults have better cardiovascular outcomes with blood pressure less than 130 mm Hg than with higher levels.

Adherence to the new guidelines would require many older adults without significant multimorbidity to take 3 drugs and undergo more frequent monitoring. This burden may align with the goals of care for many older adults. However, data do not exist to prove a benefit from intensive blood pressure control in debilitated elderly patients, and there may be harm. Lowering the medication burden may be a more important goal than lowering the pressure for this population. Blood pressure targets and hypertension management should reflect patient-centered goals of care.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017. Epub ahead of print.

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2103–2116.

- Bakris GL. The implications of blood pressure measurement methods on treatment targets for blood pressure. Circulation 2016; 134:904–905.

- Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al; SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315:2673–2682.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:695–699.

- Borland E, Nagga K, Nilsson PM, Minthon L, Nilsson ED, Palmqvist S. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: normative data from a large Swedish population-based cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 59:893–901.

- Graciani A, Garcia-Esquinas E, Lopez-Garcia E, Banegas JR, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Ideal cardiovascular health and risk of frailty in older adults. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016; 9:239–245.

- Odden MC, Peralta CA, Berlowitz DR, et al; Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) Research Group. Effect of intensive blood pressure control on gait speed and mobility limitation in adults 75 years or older: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:500–507.

- Tully PJ, Hanon O, Cosh S, Tzourio C. Diuretic antihypertensive drugs and incident dementia risk: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of prospective studies. J Hypertens 2016; 34:1027–1035.

- Rouch L, Cestac P, Hanon O, et al. Antihypertensive drugs, prevention of cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review of observational studies, randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, with discussion of potential mechanisms. CNS Drugs 2015; 29:113–130.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017. Epub ahead of print.

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2103–2116.

- Bakris GL. The implications of blood pressure measurement methods on treatment targets for blood pressure. Circulation 2016; 134:904–905.

- Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al; SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315:2673–2682.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:695–699.

- Borland E, Nagga K, Nilsson PM, Minthon L, Nilsson ED, Palmqvist S. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: normative data from a large Swedish population-based cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 59:893–901.

- Graciani A, Garcia-Esquinas E, Lopez-Garcia E, Banegas JR, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Ideal cardiovascular health and risk of frailty in older adults. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016; 9:239–245.

- Odden MC, Peralta CA, Berlowitz DR, et al; Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) Research Group. Effect of intensive blood pressure control on gait speed and mobility limitation in adults 75 years or older: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:500–507.

- Tully PJ, Hanon O, Cosh S, Tzourio C. Diuretic antihypertensive drugs and incident dementia risk: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of prospective studies. J Hypertens 2016; 34:1027–1035.

- Rouch L, Cestac P, Hanon O, et al. Antihypertensive drugs, prevention of cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review of observational studies, randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, with discussion of potential mechanisms. CNS Drugs 2015; 29:113–130.

Geriatrics update 2012: What parts of our practice to change, what to ‘think about’

A number of new studies and guidelines published over the last few years are changing the way we treat older patients. This article summarizes these recent developments in a variety of areas—from prevention of falls to targets for hypertension therapy—relevant to the treatment of geriatric patients.

A MULTICOMPONENT APPROACH TO PREVENTING FALS

The American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society’s 2010 Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls in Older Persons1 has added an important new element since the 2001 guideline: in addition to asking older patients about a fall, clinicians should also ask whether a gait or balance problem has developed.

A complete falls evaluation and multicomponent intervention is indicated for patients who in the past year or since the previous visit have had one fall with an injury or more than one fall, or for patients who report or have been diagnosed with a gait or balance problem. A falls risk assessment is not indicated for a patient with no gait or balance problem and who has had only one noninjurious fall in the previous year that did not require medical attention.

The multicomponent evaluation detailed in the guideline is very thorough and comprises more elements than can be done in a follow-up office visit. In addition to the relevant medical history, physical examination, and cognitive and functional assessment, the fall-risk evaluation includes a falls history, medication review, visual acuity testing, gait and balance assessment, postural and heart-rate evaluation, examination of the feet and footwear, and, if appropriate, a referral for home assessment of environmental hazards.

Intervention consists of many aspects

Of the interventions, exercise has the strongest correlation with falls prevention, and a prescription should include exercises for balance, gait, and strength. Tai chi is specifically recommended.

Medications should be reduced or withdrawn. The previous guideline recommended reducing medications for patients taking four or more medications, but the current guideline applies to everyone.

First cataract removal is associated with reducing the risk of falls.

Postural hypotension should be treated if present.

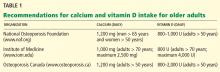

Vitamin D at 800 U per day is recommended for all elderly people at risk. For elderly people in long-term care, giving vitamin D for proven or suspected deficiency is by itself correlated with risk reduction.

Interventions that by themselves are not associated with risk reduction include education (eg, providing a handout on preventing falls) and having vision checked. For adults who are cognitively impaired, there is insufficient evidence that even the multicomponent intervention helps prevent falls.

CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D MAY NOT BE HARMLESS

Calcium supplements: A cause of heart attack?

Questions have arisen in recent studies about the potential risks of calcium supplementation.

A meta-analysis of 11 trials with nearly 12,000 participants found that the risk of myocardial infarction was significantly higher in people taking calcium supplementation (relative risk 1.27; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.59, P = .038).2 Patients were predominantly postmenopausal women and were followed for a mean of 4 years. The incidence of stroke and death were also higher in people who took calcium, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. The dosages were primarily 1,000 mg per day (range 600 mg to 2 g). Risk was independent of age, sex, and type of supplement.

The authors concluded (somewhat provocatively, because only the risk of myocardial infarction reached statistical significance) that if 1,000 people were treated with calcium supplementation for 5 years, 26 fractures would be prevented but 14 myocardial infarctions, 10 strokes, and 13 deaths would be caused.

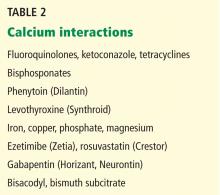

Comments. These data suggest that physicians may wish to prescribe calcium to supplement (not replace) dietary calcium to help patients reach but not exceed current guidelines for total calcium intake for age and sex. They may also want to advise the patient to take the calcium supplement separately from medications, as indicated in Table 2.

Benefits of vitamin D may depend on dosing

Studies show that the risk of hip fracture can be reduced with modest daily vitamin D supplementation, up to 800 U daily, regardless of calcium intake.3 Some vitamin D dosing regimens, however, may also entail risk.

Sanders et al4 randomized women age 70 and older to receive an annual injection of a high dose of vitamin D (500,000 U) or placebo for 3 to 5 years. Women in the vitamin D group had 15% more falls and 25% more fractures than those in the placebo group. The once-yearly dose of 500,000 U equates to 1,370 U/day, which is not much higher than the recommended daily dosage. The median baseline serum level was 49 nmol/L and reached 120 nmol/L at 30 days in the treatment group, which was not in the toxic range.

Comments. This study cautions physicians against giving large doses of vitamin D at long intervals. Future studies should focus on long-term clinical outcomes of falls and fractures for dosing regimens currently in practice, such as 50,000 units weekly or monthly.

BISPHOSPHONATES AND NONTRAUMATIC THICK BONE FRACTURES

Bisphosphonates have been regarded as the best drugs for preventing hip fracture. But in 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning that bisphosphonates have been associated with “atypical” femoral fractures. The atypical fracture pattern is a clean break through the thick bone of the shaft that occurs after minimal or no trauma.5 This pattern contrasts with the splintering “typical” fracture in the proximal femur in osteoporotic bone, usually after a fall.

Another characteristic of the atypical fractures is a higher incidence of postoperative complications requiring revision surgery. In more than 14,000 women in secondary analyses of three large randomized bisphosphonate trials, 12 fractures in 10 patients were found that were classified as atypical, averaging to an incidence of 2.3 per 10,000 patient-years.6

A population-based, nested case-control study7 using Canadian pharmacy records evaluated more than 200,000 women at least 68 years old who received bisphosphonate therapy. Of these, 716 (0.35%) sustained an atypical femoral fracture and 9,723 (4.7%) had a typical osteoporotic femoral fracture. Comparing the duration of bisphosphonate use between the two groups, the authors found that the risk of an atypical fracture increased with years of usage (at 5 years or more, the adjusted odds ratio was 2.74, 95% CI 1.25–6.02), but the risk of a typical fracture decreased (at 5 years or more, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.76, 95% CI 0.63–0.93). The study suggests that for every 100 hip fractures that bisphosphonate therapy prevents, it causes one atypical hip fracture.

Comments. These studies have caused some experts to advocate periodic bisphosphonate “vacations,”8 but for how long remains an open question because the risk of a typical fracture will increase. It is possible that a biomarker can help establish the best course, but that has yet to be determined.

DENOSUMAB: A NEW DRUG FOR OSTEOPOROSIS WITH A BIG PRICE TAG

Denosumab (Prolia, Xgeva), a newly available injectable drug, is a monoclonal antibody member of the tumor necrosis factor super-family.9 It is FDA-approved for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at a dosage of 60 mg every 6 months and for skeletal metastases from solid tumors (120 mg every 4 weeks). It is also being used off-label for skeletal protection in women taking aromatase inhibitors and for men with androgen deficiency.

This drug is expensive, costing $850 per 60-mg dose wholesale, and no data are yet available on its long-term effects.

Since the drug is not cleared via renal mechanisms, there is some hope that it can be used to treat osteoporosis in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, since bisphosphonates are contraindicated in those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 to 35 mL/min. However, the major study of denosumab to date, the Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months (FREEDOM) study, had no patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or on dialysis), and too few with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (GFR 15–29) to demonstrate either the safety or efficacy of denosumab in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease.10

HYPERTENSION TREATMENT

A secondary analysis of a recent large hypertension study confirmed the benefits of antihypertensive therapy in very old adults and suggested new targets for systolic and diastolic blood pressures.11,12

The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) trial,13 the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) trial,14 and the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)15 are the major, randomized, placebo-controlled antihypertensive trials in older adults. They all showed a reduction in the risk of stroke and cardiovascular events. The diuretic studies (SHEP and HYVET)13,15 also showed a lower risk of heart failure and death.

Most recently, secondary analysis of the International Verapamil-Trandolapril (INVEST) study11,12 showed that adults in the oldest groups (age 70–79 and 80 and older), experienced a greater risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes if systolic blood pressure was lowered to below about 130 mm Hg. As diastolic blood pressure was lowered to about the 65–70 mm Hg range, all age groups in the study experienced an increased risk of cardiovascular events. These results confirm the findings of a secondary analysis of the SHEP trial,16 showing an increased risk of cardiovascular events when diastolic pressure was lowered to below approximately 65 mm Hg.

These studies have been incorporated into 75 pages of the 2011 Expert Consensus Document on Hypertension in the Elderly issued by the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association.17 In a nutshell, the guidelines suggest that older adults less than 80 years of age be treated comparably to middle-aged adults. However, for adults age 80 and older:

- A target for systolic blood pressure of 140 to 145 mm Hg “can be acceptable.”

- Initiating treatment with monotherapy (with a low-dose thiazide, calcium channel blocker, or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system drug) is reasonable. A second drug may be added if needed.

- Patients should be monitored for “excessive” orthostasis.

- Systolic blood pressure lower than 130 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure lower than 65 mm Hg should be avoided.

TRANSCATHETER AORTIC VALVE IMPLANTATION APPROVED BY THE FDA

An estimated 2% to 9% of the elderly have aortic stenosis. Aortic valve replacement reduces mortality rates and improves function in all age groups, including octogenarians. Those with asymptomatic aortic stenosis tend to decline very quickly once they develop heart failure, syncope, or angina. Aortic valve replacement has been shown to put people back on the course they were on before they became symptomatic.

Transcatheter self-expanding transaortic valve implantation was approved by the FDA in November 2011. The procedure does not require open surgery and involves angioplasty of the old valve, with the new valve being passed into place through a catheter and expanded. Access is either transfemoral or transapical.

Transaortic valve implantation has been rapidly adopted in Europe since 2002 without any randomized control trials. The Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial18 in 2011 was the first randomized trial of this therapy. It was conducted at 25 centers, with nearly 700 patients with severe aortic stenosis randomized to undergo either transcatheter aortic valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve (244 via the transfemoral and 104 via the transapical approach) or surgical replacement. The mean age of the patients was 84 years, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons mean score was 12%, indicating high perioperative risk.

At 30 days after the procedure, the rates of death were 3.4% with transcatheter implantation and 6.5% with surgical replacement (P = .07). At 1 year, the rates were 24.2% and 26.8%, respectively (P = 0.44, and P = .001 for noninferiority). However, the rate of major stroke was higher in the transcatheter implantation group: 3.8% vs 2.1% in the surgical group (P = .20) at 1 month and 5.1% vs 2.4% (P = .07) at 1 year. Vascular complications were significantly more frequent in the transcatheter implantation group, and the new onset of atrial fibrillation and major bleeding were significantly higher in the surgical group.

Patients in the transcatheter implantation group had a significantly shorter length of stay in the intensive care unit and a shorter index hospitalization. At 30 days, the transcatheter group also had a significant improvement in New York Heart Association functional status and a better 6-minute walk performance, although at 1 year, these measures were similar between the two groups and were greatly improved over baseline. Quality of life, measured using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, was higher both at 6 months and at 1 year in the transcatheter implantation group compared with those who underwent the open surgical procedure.19

Comments. The higher risk of stroke with the transcatheter implantation procedure remains a concern. More evaluation is also needed with respect to function and cognition in the very elderly, and of efficacy and safety in higher- and lower-risk patients.

DEPRESSION CAN BE EFFECTIVELY TREATED WITH MEDICATION

Many placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of treating depression with medications in elderly people who are cognitively intact and living in the community. A Cochrane Review20 found that in placebo-controlled trials, the number needed to treat to produce one recovery with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors was less than 10 for each of the drug classes.

Since the newer drugs appear to be safer and to have fewer adverse effects than the older drugs, more older adults have been treated with antidepressants, including patients with comorbidities such as dementia that were exclusion criteria in early studies. For example, the number of older adults treated with antidepressants has increased 25% since 1992; at the same time the number being referred for cognitive-based therapies has been reduced by 43%.21 Similar trends are apparent in elderly people in long-term care. In 1999, about one-third of people in long-term care were diagnosed with depression; in 2007 more than one-half were.22

Treating depression is less effective when dementia is present

Up to half of adults age 85 and older living in the community may have dementia. In long-term care facilities, most residents likely have some cognitive impairment or are diagnosed with dementia. Many of these are also taking antidepressive agents.

A review of studies in the Medline and Cochrane registries found seven trials that treated 330 patients with antidepressants for combined depression and dementia. Efficacy was not confirmed.23

After this study was published, Banerjee et al24 treated 218 patients who had depression and dementia in nine centers in the United Kingdom. Patients received sertraline (Zoloft), mirtazapine (Remeron), or placebo. Reductions in depression scores at 13 weeks and at 39 weeks did not differ between the groups, and adverse events were more frequent in the treatment groups than in the placebo groups.

Comments. The poor performance of antidepressants in patients with dementia may be due to misdiagnosis, such as mistaking apathy for depression.25 It is also possible that better criteria than we have now are needed to diagnose depression in patients with dementia, or that current outcome measures are not sensitive for depression when dementia is present.

It may also be unsafe to treat older adults long-term with antidepressive agents. For example, although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the most commonly prescribed antidepressive agents, are considered safe, their side effects are numerous and include sexual dysfunction, bleeding (due to platelet dysfunction), hyponatremia, early weight loss, tremor (mostly with paroxetine [Paxil]), sedation, apathy (especially with high doses), loose stools (with sertraline), urinary incontinence, falls, bone loss, and QTc prolongation.

Citalopram: Maximum dosage in elderly

In August 2011, an FDA Safety Communication was issued for citalopram (Celexa), stating that the daily dose should not exceed 40 mg in the general population and should not exceed 20 mg in patients age 60 and older. The dose should also not exceed 20 mg for a patient at any age who has hepatic impairment, who is known to be a poor metabolizer of CYP 2C19, or who takes cimetidine (Tagamet), since that drug inhibits the metabolism of citalopram at the CYP 2C19 enzyme site.

Although the FDA warning specifically mentions only cimetidine, physicians may have concerns about other drugs that inhibit CYP 2C19, such as proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole [Prilosec]) when taken concomitantly with citalopram. Also, escitalopram (Lexapro) and sertraline are quite similar to citalopram; although they were not mentioned in the FDA Safety Communication, higher doses of these drugs may put patients at similar risk.

ALZHEIMER DISEASE: NEED TO BETTER IDENTIFY PEOPLE AT RISK

The definition of dementia is essentially the presence of a cognitive problem that affects the ability to function. For people with Alzheimer disease, impairment of cognitive performance precedes functional decline. Those with a cognitive deficit who still function well have, by definition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Although MCI could be caused by a variety of vascular and other neurologic processes, the most common cause of MCI in the United States is Alzheimer disease.

Unfortunately, the population with MCI currently enrolled in clinical trials to reduce the risk of progression to Alzheimer disease is heterogeneous. Many study participants may never get dementia, and others may have had the pathology present for decades and are progressing rapidly. Imaging and biomarkers are emerging as good indicators that predict progression and could help to better define populations for clinical trials.26

Studies now indicate that people with MCI that is ultimately due to Alzheimer disease are likely to have amyloid beta peptide 42 evident in the cerebrospinal fluid 10 to 20 years before symptoms arise. At the same time, amyloid is also likely to be evident in the brain with amyloid-imaging positron emission tomography (PET). Some time later, abnormalities in metabolism are also evident on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET, as are changes such as reduced hippocampal volume on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The 1984 criteria for diagnosing MCI due to Alzheimer disease were recently revised to incorporate the evolving availability of biomarkers.27,28 The diagnosis of MCI itself is still based on clinical ascertainment including history, physical examination, and cognitive testing. It requires diagnosis of a cognitive decline from a prior level but maintenance of activities of daily living with no or minimal assistance. This diagnosis is certainly challenging since it requires ascertainment of a prior level of function and corroboration, when feasible, with an informant. Blood tests and imaging, which are readily available, constitute an important part of the assessment.

Attributing the MCI to Alzheimer disease requires consistency of the disease course—a gradual decline in Alzheimer disease, rather than a stroke, head injury, neurologic disease such as Parkinson disease, or mixed causes.

Knowledge of genetic factors, such as the presence of a mutation in APP, PS1, or PS2, can be predictive with young patients. The presence of one or two 34 alleles in the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is the only genetic variant broadly accepted as increasing the risk for late-onset Alzheimer dementia, whereas the 32 allele decreases risk.

Refining the risk attribution to Alzheimer disease requires biomarkers, currently available only in research settings:

- High likelihood—amyloid beta peptide detected by PET or cerebrospinal fluid analysis and evidence of neuronal degeneration or injury (elevated tau in the cerebrospinal fluid, decreased FDG uptake on PET, and atrophy evident by structural MRI)

- Intermediate likelihood—presence of amyloid beta peptide or evidence of neuronal degeneration or injury

- Unlikely—biomarkers tested and negative

- No comment—biomarkers not tested or reporting is indeterminate.

Comments. There is significant potential for misunderstanding the new definition for MCI. Patients who are concerned about their memory may request biomarker testing in an effort to determine if they currently have or will acquire Alzheimer disease. Doctors may be tempted to refer patients for biomarker testing (via imaging or lumbar puncture) to “screen” for MCI or Alzheimer disease.

It should be emphasized that MCI itself is still a clinical diagnosis, with the challenges noted above of determining whether there has been a cognitive decline from a prior level of function but preservation of activities of daily living. The biomarkers are not proposed to diagnose MCI, but only to help identify the subset of MCI patients most likely to progress rapidly to Alzheimer disease.

At present, the best use of biomarker testing is to aid research by identifying high-risk people among those with MCI who enroll in prospective trials for testing interventions to reduce the progression of Alzheimer disease.

- Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:148–157.

- Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: metaanalysis. BMJ 2010; 341:c3691.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:551–561.

- Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010; 303:1815–1822.

- Kuehn BM. Prolonged bisphosphonate use linked to rare fractures, esophageal cancer. JAMA 2010; 304:2114–2115.

- Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, et al; Fracture Intervention Trial Steering Committee; HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial Steering Committee. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1761–1771.

- Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA 2011; 305:783–789.

- Ott SM. What is the optimal duration of bisphosphonate therapy? Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:619–630.

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al; for the FREEDOM trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:756–765.

- Jamal SA, Ljunggren O, Stehman-Breen C, et al. Effects of denosumab on fracture and bone mineral density by level of kidney function. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26:1829–1835.

- Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-Dehoff RM, et al. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290:2805–2816.

- Denardo SJ, Gong Y, Nichols WW, et al. Blood pressure and outcomes in very old hypertensive coronary artery disease patients: an INVEST substudy. Am J Med 2010; 123:719–726.

- SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 1991; 265:3255–3264.

- Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al; for the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension (erratum published in Lancet 1997; 350:1636). Lancet 1997; 350:757–764.

- Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al; for the HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1887–1898.

- Somes G, Pahor M, Shorr R, Cushman WC, Applegate WB. The role of diastolic blood pressure when treating isolated systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:2004–2009.

- Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:2037–2114.

- Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2187–2198.

- Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Lei Y, et al; Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) Investigators. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in inoperable patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2011; 124:1964–1972.

- Wilson K, Mottram P, Sivanranthan A, Nightingale A. Antidepressant versus placebo for depressed elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(2):CD000561.

- Akincigil A, Olfson M, Walkup JT, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in older community-dwelling adults: 1992–2005. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:1042–1051.

- Gaboda D, Lucas J, Siegel M, Kalay E, Crystal S. No longer undertreated? Depression diagnosis and antidepressant therapy in elderly long-stay nursing home residents, 1999 to 2007. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:673–680.

- Nelson JC, Devanand DP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled antidepressant studies in peoloe with depression and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:577–585.

- Banerjee S, Hellier J, Dewey M, et al. Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 378:403–411.

- Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, Geldmacher DS. Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:1700–1707.

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Revising the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9:1118–1127.

- Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: preventing Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline. Ann Intern Med 2010; 153:176–181.

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7:263–269.

A number of new studies and guidelines published over the last few years are changing the way we treat older patients. This article summarizes these recent developments in a variety of areas—from prevention of falls to targets for hypertension therapy—relevant to the treatment of geriatric patients.

A MULTICOMPONENT APPROACH TO PREVENTING FALS

The American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society’s 2010 Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls in Older Persons1 has added an important new element since the 2001 guideline: in addition to asking older patients about a fall, clinicians should also ask whether a gait or balance problem has developed.

A complete falls evaluation and multicomponent intervention is indicated for patients who in the past year or since the previous visit have had one fall with an injury or more than one fall, or for patients who report or have been diagnosed with a gait or balance problem. A falls risk assessment is not indicated for a patient with no gait or balance problem and who has had only one noninjurious fall in the previous year that did not require medical attention.

The multicomponent evaluation detailed in the guideline is very thorough and comprises more elements than can be done in a follow-up office visit. In addition to the relevant medical history, physical examination, and cognitive and functional assessment, the fall-risk evaluation includes a falls history, medication review, visual acuity testing, gait and balance assessment, postural and heart-rate evaluation, examination of the feet and footwear, and, if appropriate, a referral for home assessment of environmental hazards.

Intervention consists of many aspects

Of the interventions, exercise has the strongest correlation with falls prevention, and a prescription should include exercises for balance, gait, and strength. Tai chi is specifically recommended.

Medications should be reduced or withdrawn. The previous guideline recommended reducing medications for patients taking four or more medications, but the current guideline applies to everyone.

First cataract removal is associated with reducing the risk of falls.

Postural hypotension should be treated if present.

Vitamin D at 800 U per day is recommended for all elderly people at risk. For elderly people in long-term care, giving vitamin D for proven or suspected deficiency is by itself correlated with risk reduction.

Interventions that by themselves are not associated with risk reduction include education (eg, providing a handout on preventing falls) and having vision checked. For adults who are cognitively impaired, there is insufficient evidence that even the multicomponent intervention helps prevent falls.

CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D MAY NOT BE HARMLESS

Calcium supplements: A cause of heart attack?

Questions have arisen in recent studies about the potential risks of calcium supplementation.

A meta-analysis of 11 trials with nearly 12,000 participants found that the risk of myocardial infarction was significantly higher in people taking calcium supplementation (relative risk 1.27; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.59, P = .038).2 Patients were predominantly postmenopausal women and were followed for a mean of 4 years. The incidence of stroke and death were also higher in people who took calcium, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. The dosages were primarily 1,000 mg per day (range 600 mg to 2 g). Risk was independent of age, sex, and type of supplement.

The authors concluded (somewhat provocatively, because only the risk of myocardial infarction reached statistical significance) that if 1,000 people were treated with calcium supplementation for 5 years, 26 fractures would be prevented but 14 myocardial infarctions, 10 strokes, and 13 deaths would be caused.

Comments. These data suggest that physicians may wish to prescribe calcium to supplement (not replace) dietary calcium to help patients reach but not exceed current guidelines for total calcium intake for age and sex. They may also want to advise the patient to take the calcium supplement separately from medications, as indicated in Table 2.

Benefits of vitamin D may depend on dosing

Studies show that the risk of hip fracture can be reduced with modest daily vitamin D supplementation, up to 800 U daily, regardless of calcium intake.3 Some vitamin D dosing regimens, however, may also entail risk.

Sanders et al4 randomized women age 70 and older to receive an annual injection of a high dose of vitamin D (500,000 U) or placebo for 3 to 5 years. Women in the vitamin D group had 15% more falls and 25% more fractures than those in the placebo group. The once-yearly dose of 500,000 U equates to 1,370 U/day, which is not much higher than the recommended daily dosage. The median baseline serum level was 49 nmol/L and reached 120 nmol/L at 30 days in the treatment group, which was not in the toxic range.

Comments. This study cautions physicians against giving large doses of vitamin D at long intervals. Future studies should focus on long-term clinical outcomes of falls and fractures for dosing regimens currently in practice, such as 50,000 units weekly or monthly.

BISPHOSPHONATES AND NONTRAUMATIC THICK BONE FRACTURES

Bisphosphonates have been regarded as the best drugs for preventing hip fracture. But in 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning that bisphosphonates have been associated with “atypical” femoral fractures. The atypical fracture pattern is a clean break through the thick bone of the shaft that occurs after minimal or no trauma.5 This pattern contrasts with the splintering “typical” fracture in the proximal femur in osteoporotic bone, usually after a fall.

Another characteristic of the atypical fractures is a higher incidence of postoperative complications requiring revision surgery. In more than 14,000 women in secondary analyses of three large randomized bisphosphonate trials, 12 fractures in 10 patients were found that were classified as atypical, averaging to an incidence of 2.3 per 10,000 patient-years.6

A population-based, nested case-control study7 using Canadian pharmacy records evaluated more than 200,000 women at least 68 years old who received bisphosphonate therapy. Of these, 716 (0.35%) sustained an atypical femoral fracture and 9,723 (4.7%) had a typical osteoporotic femoral fracture. Comparing the duration of bisphosphonate use between the two groups, the authors found that the risk of an atypical fracture increased with years of usage (at 5 years or more, the adjusted odds ratio was 2.74, 95% CI 1.25–6.02), but the risk of a typical fracture decreased (at 5 years or more, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.76, 95% CI 0.63–0.93). The study suggests that for every 100 hip fractures that bisphosphonate therapy prevents, it causes one atypical hip fracture.

Comments. These studies have caused some experts to advocate periodic bisphosphonate “vacations,”8 but for how long remains an open question because the risk of a typical fracture will increase. It is possible that a biomarker can help establish the best course, but that has yet to be determined.

DENOSUMAB: A NEW DRUG FOR OSTEOPOROSIS WITH A BIG PRICE TAG

Denosumab (Prolia, Xgeva), a newly available injectable drug, is a monoclonal antibody member of the tumor necrosis factor super-family.9 It is FDA-approved for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at a dosage of 60 mg every 6 months and for skeletal metastases from solid tumors (120 mg every 4 weeks). It is also being used off-label for skeletal protection in women taking aromatase inhibitors and for men with androgen deficiency.

This drug is expensive, costing $850 per 60-mg dose wholesale, and no data are yet available on its long-term effects.

Since the drug is not cleared via renal mechanisms, there is some hope that it can be used to treat osteoporosis in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, since bisphosphonates are contraindicated in those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 to 35 mL/min. However, the major study of denosumab to date, the Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months (FREEDOM) study, had no patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or on dialysis), and too few with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (GFR 15–29) to demonstrate either the safety or efficacy of denosumab in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease.10

HYPERTENSION TREATMENT

A secondary analysis of a recent large hypertension study confirmed the benefits of antihypertensive therapy in very old adults and suggested new targets for systolic and diastolic blood pressures.11,12

The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) trial,13 the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) trial,14 and the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)15 are the major, randomized, placebo-controlled antihypertensive trials in older adults. They all showed a reduction in the risk of stroke and cardiovascular events. The diuretic studies (SHEP and HYVET)13,15 also showed a lower risk of heart failure and death.

Most recently, secondary analysis of the International Verapamil-Trandolapril (INVEST) study11,12 showed that adults in the oldest groups (age 70–79 and 80 and older), experienced a greater risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes if systolic blood pressure was lowered to below about 130 mm Hg. As diastolic blood pressure was lowered to about the 65–70 mm Hg range, all age groups in the study experienced an increased risk of cardiovascular events. These results confirm the findings of a secondary analysis of the SHEP trial,16 showing an increased risk of cardiovascular events when diastolic pressure was lowered to below approximately 65 mm Hg.

These studies have been incorporated into 75 pages of the 2011 Expert Consensus Document on Hypertension in the Elderly issued by the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association.17 In a nutshell, the guidelines suggest that older adults less than 80 years of age be treated comparably to middle-aged adults. However, for adults age 80 and older:

- A target for systolic blood pressure of 140 to 145 mm Hg “can be acceptable.”

- Initiating treatment with monotherapy (with a low-dose thiazide, calcium channel blocker, or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system drug) is reasonable. A second drug may be added if needed.

- Patients should be monitored for “excessive” orthostasis.

- Systolic blood pressure lower than 130 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure lower than 65 mm Hg should be avoided.

TRANSCATHETER AORTIC VALVE IMPLANTATION APPROVED BY THE FDA

An estimated 2% to 9% of the elderly have aortic stenosis. Aortic valve replacement reduces mortality rates and improves function in all age groups, including octogenarians. Those with asymptomatic aortic stenosis tend to decline very quickly once they develop heart failure, syncope, or angina. Aortic valve replacement has been shown to put people back on the course they were on before they became symptomatic.

Transcatheter self-expanding transaortic valve implantation was approved by the FDA in November 2011. The procedure does not require open surgery and involves angioplasty of the old valve, with the new valve being passed into place through a catheter and expanded. Access is either transfemoral or transapical.

Transaortic valve implantation has been rapidly adopted in Europe since 2002 without any randomized control trials. The Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial18 in 2011 was the first randomized trial of this therapy. It was conducted at 25 centers, with nearly 700 patients with severe aortic stenosis randomized to undergo either transcatheter aortic valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve (244 via the transfemoral and 104 via the transapical approach) or surgical replacement. The mean age of the patients was 84 years, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons mean score was 12%, indicating high perioperative risk.

At 30 days after the procedure, the rates of death were 3.4% with transcatheter implantation and 6.5% with surgical replacement (P = .07). At 1 year, the rates were 24.2% and 26.8%, respectively (P = 0.44, and P = .001 for noninferiority). However, the rate of major stroke was higher in the transcatheter implantation group: 3.8% vs 2.1% in the surgical group (P = .20) at 1 month and 5.1% vs 2.4% (P = .07) at 1 year. Vascular complications were significantly more frequent in the transcatheter implantation group, and the new onset of atrial fibrillation and major bleeding were significantly higher in the surgical group.

Patients in the transcatheter implantation group had a significantly shorter length of stay in the intensive care unit and a shorter index hospitalization. At 30 days, the transcatheter group also had a significant improvement in New York Heart Association functional status and a better 6-minute walk performance, although at 1 year, these measures were similar between the two groups and were greatly improved over baseline. Quality of life, measured using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, was higher both at 6 months and at 1 year in the transcatheter implantation group compared with those who underwent the open surgical procedure.19

Comments. The higher risk of stroke with the transcatheter implantation procedure remains a concern. More evaluation is also needed with respect to function and cognition in the very elderly, and of efficacy and safety in higher- and lower-risk patients.

DEPRESSION CAN BE EFFECTIVELY TREATED WITH MEDICATION

Many placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of treating depression with medications in elderly people who are cognitively intact and living in the community. A Cochrane Review20 found that in placebo-controlled trials, the number needed to treat to produce one recovery with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors was less than 10 for each of the drug classes.

Since the newer drugs appear to be safer and to have fewer adverse effects than the older drugs, more older adults have been treated with antidepressants, including patients with comorbidities such as dementia that were exclusion criteria in early studies. For example, the number of older adults treated with antidepressants has increased 25% since 1992; at the same time the number being referred for cognitive-based therapies has been reduced by 43%.21 Similar trends are apparent in elderly people in long-term care. In 1999, about one-third of people in long-term care were diagnosed with depression; in 2007 more than one-half were.22

Treating depression is less effective when dementia is present

Up to half of adults age 85 and older living in the community may have dementia. In long-term care facilities, most residents likely have some cognitive impairment or are diagnosed with dementia. Many of these are also taking antidepressive agents.

A review of studies in the Medline and Cochrane registries found seven trials that treated 330 patients with antidepressants for combined depression and dementia. Efficacy was not confirmed.23

After this study was published, Banerjee et al24 treated 218 patients who had depression and dementia in nine centers in the United Kingdom. Patients received sertraline (Zoloft), mirtazapine (Remeron), or placebo. Reductions in depression scores at 13 weeks and at 39 weeks did not differ between the groups, and adverse events were more frequent in the treatment groups than in the placebo groups.

Comments. The poor performance of antidepressants in patients with dementia may be due to misdiagnosis, such as mistaking apathy for depression.25 It is also possible that better criteria than we have now are needed to diagnose depression in patients with dementia, or that current outcome measures are not sensitive for depression when dementia is present.

It may also be unsafe to treat older adults long-term with antidepressive agents. For example, although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the most commonly prescribed antidepressive agents, are considered safe, their side effects are numerous and include sexual dysfunction, bleeding (due to platelet dysfunction), hyponatremia, early weight loss, tremor (mostly with paroxetine [Paxil]), sedation, apathy (especially with high doses), loose stools (with sertraline), urinary incontinence, falls, bone loss, and QTc prolongation.

Citalopram: Maximum dosage in elderly

In August 2011, an FDA Safety Communication was issued for citalopram (Celexa), stating that the daily dose should not exceed 40 mg in the general population and should not exceed 20 mg in patients age 60 and older. The dose should also not exceed 20 mg for a patient at any age who has hepatic impairment, who is known to be a poor metabolizer of CYP 2C19, or who takes cimetidine (Tagamet), since that drug inhibits the metabolism of citalopram at the CYP 2C19 enzyme site.

Although the FDA warning specifically mentions only cimetidine, physicians may have concerns about other drugs that inhibit CYP 2C19, such as proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole [Prilosec]) when taken concomitantly with citalopram. Also, escitalopram (Lexapro) and sertraline are quite similar to citalopram; although they were not mentioned in the FDA Safety Communication, higher doses of these drugs may put patients at similar risk.

ALZHEIMER DISEASE: NEED TO BETTER IDENTIFY PEOPLE AT RISK

The definition of dementia is essentially the presence of a cognitive problem that affects the ability to function. For people with Alzheimer disease, impairment of cognitive performance precedes functional decline. Those with a cognitive deficit who still function well have, by definition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Although MCI could be caused by a variety of vascular and other neurologic processes, the most common cause of MCI in the United States is Alzheimer disease.