User login

Effect of Alirocumab Monotherapy vs Ezetimibe Plus Statin Therapy on LDL-C Lowering in Veterans With History of ASCVD

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. ASCVD involves the buildup of cholesterol plaque in arteries and includes acute coronary syndrome, peripheral arterial disease, and events such as myocardial infarction and stroke.1 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors include high cholesterol levels, elevated blood pressure, insulin resistance, elevated blood glucose levels, smoking, poor dietary habits, and a sedentary lifestyle.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 86 million adults aged ≥ 20 years have total cholesterol levels > 200 mg/dL. More than half (54.5%) who could benefit are currently taking cholesterol-lowering medications.3 Controlling high cholesterol in American adults, especially veterans, is essential for reducing CVD morbidity and mortality.

The 2018 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline recommends a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) target goal of < 70 mg/dL for patients at high risk for ASCVD. Very high-risk ASCVD includes a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions (eg, age ≥ 65 years, smoking, or diabetes).4 Major ASCVD events include recent acute coronary syndrome (within the past 12 months), a history of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, and symptomatic peripheral artery disease.

The ACC/AHA guideline suggests that if the LDL-C level remains ≥ 70 mg/dL, adding ezetimibe (a dietary cholesterol absorption inhibitor) to maximally tolerated statin therapy is reasonable. If LDL-C levels remain ≥ 70 mg/dL, adding a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor, such as alirocumab, is reasonable.4 The US Departments of Veterans Affairs/US Department of Defense guidelines recommend using maximally tolerated statins and ezetimibe before PCSK9 inhibitors due to established long-term safety and reduction in CVD events.

Generic statins and ezetimibe are administered orally and widely available. In contrast, PCSK9 inhibitors have unknown long-term safety profiles, require subcutaneous injection once or twice monthly, and are significantly more expensive. They also require patient education on proper use while providing comparable or lesser relative risk reductions.2

These 3 classes of medication vary in their mechanisms of action to reduce LDL.5,6 Ezetimibe and several statin medications are included on the Veterans Affairs Sioux Falls Health Care System (VASFHCS) formulary and do not require review prior to prescribing. Alirocumab is available at VASFHCS but is restricted to patients with a history of ASCVD or a diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia, and who are receiving maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy but require further LDL-C lowering to reduce their ASCVD risk.

Studies have found ezetimibe monotherapy reduces LDL-C in patients with dyslipidemia by 18% after 12 weeks.7 One found that the percentage reduction in LDL-C was significantly greater (P < .001) with all doses of ezetimibe plus simvastatin (46% to 59%) compared with either atorvastatin 10 mg (37%) or simvastatin 20 mg (38%) monotherapy after 6 weeks.8

Although alirocumab can be added to other lipid therapies, most VASFHCS patients are prescribed alirocumab monotherapy. In the ODYSSEY CHOICE II study, patients were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo or alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks or alirocumab 75 mg every 2 weeks. The primary efficacy endpoint was LDL-C percentage change from baseline to week 24. In the alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks and 75 mg every 2 weeks groups, the least-squares mean LDL-C changes from baseline to week 24 were 51.7% and 53.5%, respectively, compared to a 4.7% increase in the placebo group (both groups P < .001 vs placebo). The authors also reported that alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks as monotherapy demonstrated a 47.4% reduction in LDL-C levels from baseline in a phase 1 study.9Although alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy have been shown to effectively decrease LDL-C independently, a direct comparison of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy has not been assessed, to our knowledge. Understanding the differences in effectiveness and safety between these 2 regimens will be valuable for clinicians when selecting a medication regimen for veterans with a history of ASCVD.

METHODS

This retrospective, single-center chart review used VASFHCS Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and Joint Longitudinal Viewer (JLV) records to compare patients with a history of ASCVD events who were treated with alirocumab monotherapy or ezetimibe plus statin. The 2 groups were randomized in a 1:3 ratio. The primary endpoint was achieving LDL-C < 70 mg/dL after 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks. Secondary endpoints included the mean percentage change from baseline in total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL-C, and triglycerides (TG) over 52 weeks. The incidence of ASCVD events during this period was also assessed. If LDL-C < 70 mg/dL was achieved > 1 time during each time frame, only 1 incident was counted for analysis. Safety was assessed based on the incidence of any adverse event (AE) that led to treatment discontinuation.

Patients were identified by screening the prescription fill history between October 1, 2019, and December 31, 2022. The 52-week data collection period was counted from the first available fill date. Additionally, the prior authorization drug request file from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2022, was used to obtain a list of patients prescribed alirocumab. Patients were included if they were veterans aged ≥ 18 years and had a history of an ASCVD event, had a alirocumab monotherapy or ezetimibe plus statin prescription between October 1, 2019, and December 31, 2022, or had an approved prior authorization drug request for alirocumab between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2022. Patients missing a baseline or follow-up lipid panel and those with concurrent use of alirocumab and ezetimibe and/or statin were excluded.

Baseline characteristics collected for patients included age, sex, race, weight, body mass index, lipid parameters (LDL-C, TC, HDL-C, and TG), dosing of each type of statin before adding ezetimibe, and use of any other antihyperlipidemic medication. We also collected histories of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, and smoking or tobacco use status. The baseline lipid panel was the most recent lipid panel documented before starting alirocumab or ezetimibe plus statin therapy. Follow-up lipid panel values were gathered at 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks following initiation of either therapy.

High-, moderate-, and low-intensity dosing of statin therapy and alirocumab dosing (75 mg every 2 weeks, 150 mg every 2 weeks, or 300 mg every 4 weeks) were recorded at the specified intervals. However, no patients in this study received the latter dosing regimen. ASCVD events and safety endpoints were recorded based on a review of clinical notes over the 52 weeks following the first available start date.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of achieving the LDL-C < 70 mg/dL goal from baseline to 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks after initiation was compared between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy using the χ² test. Mean percentage change from baseline in TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and TG were compared using the independent t test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Incidence of ASCVD events and the safety endpoint (incidence of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation) were also compared using the χ² test. Continuous baseline characteristics were reported mean (SD) and nominal baseline characteristics were reported as a percentage.

RESULTS

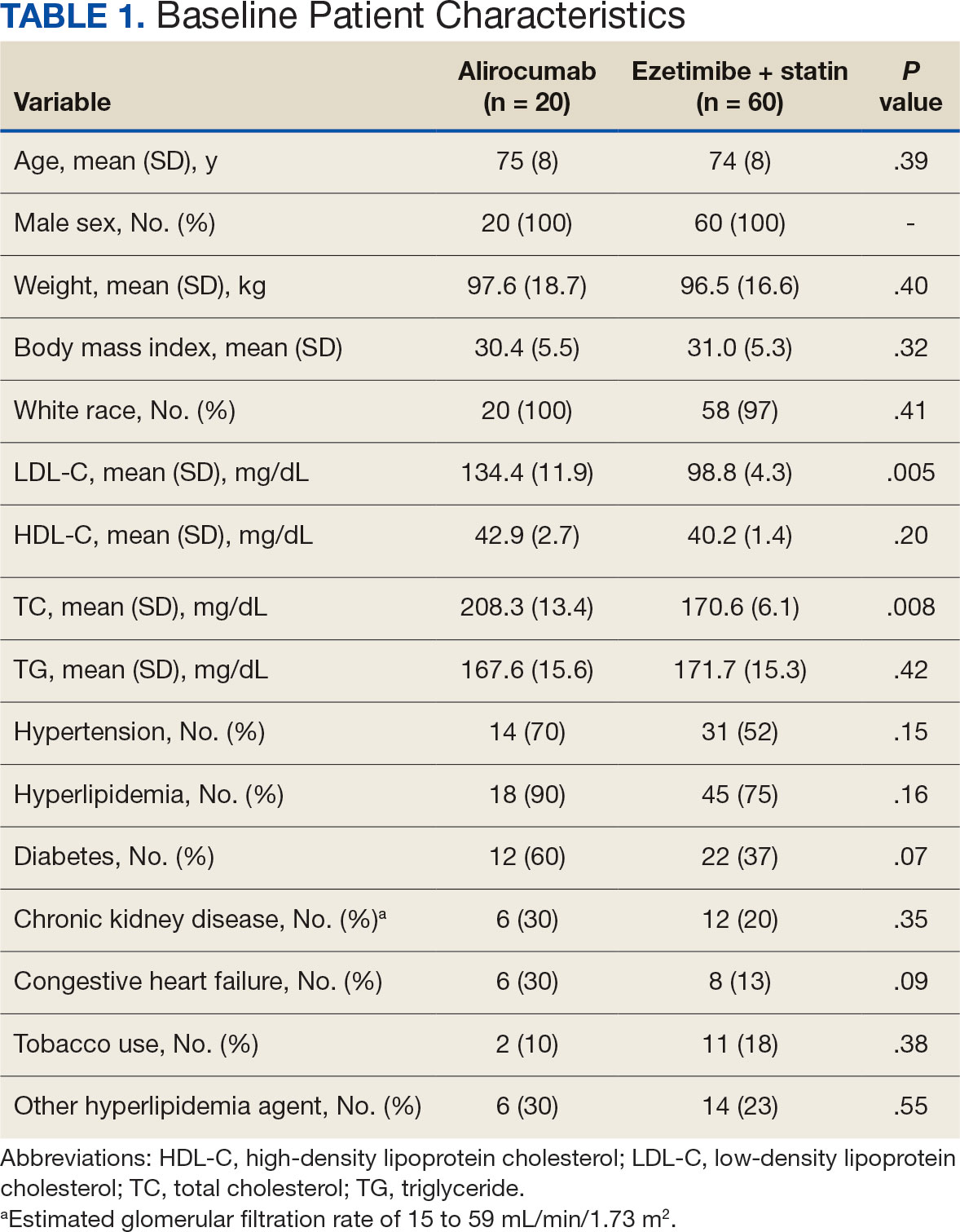

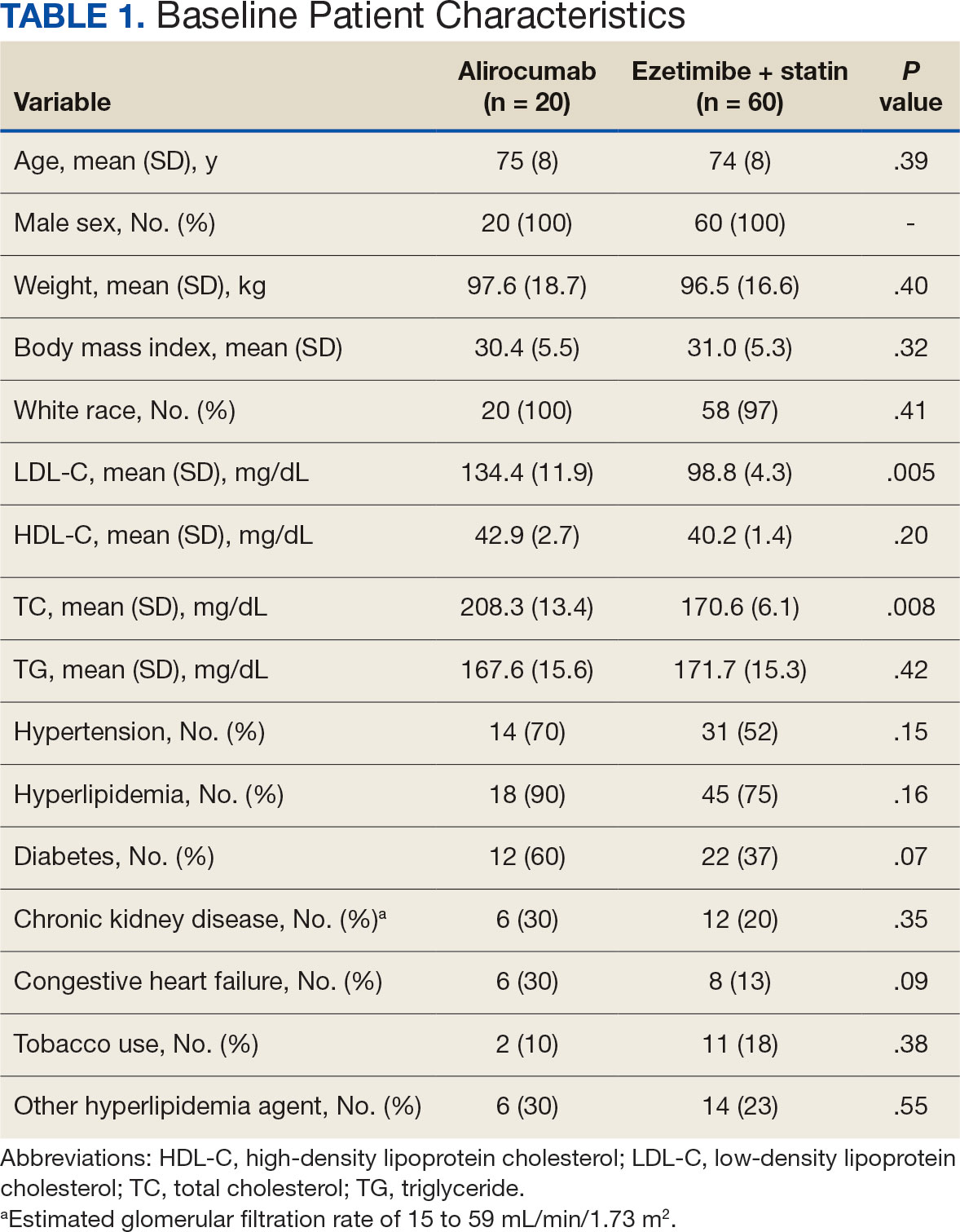

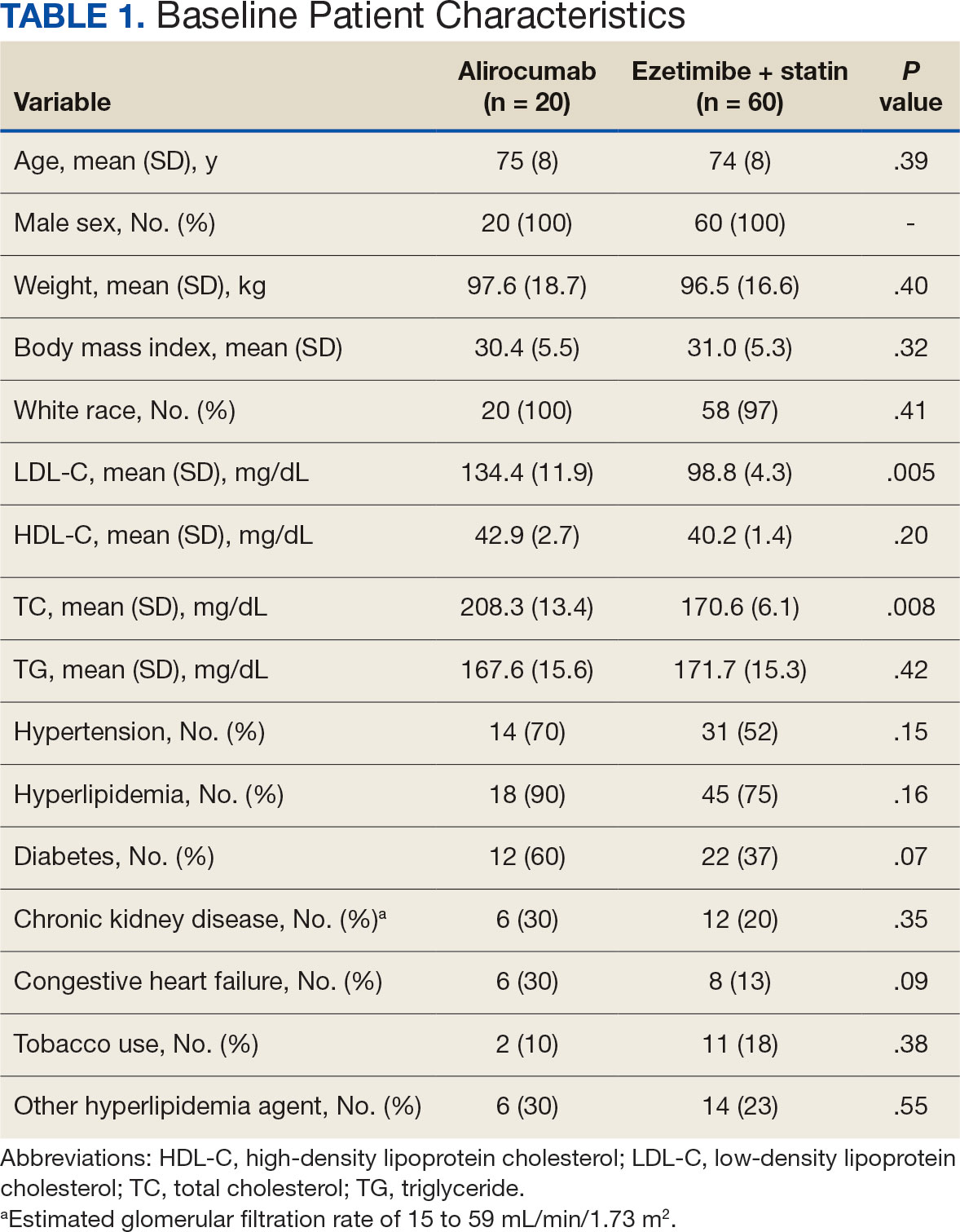

There were 80 participants in this study: 20 in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 60 in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. More than 100 patients did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria and were excluded. Mean (SD) age was 75 (8) years in the alirocumab group and 74 (8) years in the ezetimibe plus statin group. There was no significant differences in mean (SD) weight or mean (SD) body mass index. All study participants identified as White and male except for 2 patients in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group whose race was not documented. Differences in lipid parameters were observed between groups, with mean baseline LDL-C, HDL-C, and TC higher in the alirocumab monotherapy group than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, with significant differences in LDL-C and TC (Table 1).

Fourteen patients (70%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group had hypertension, compared with 31 (52%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. In both groups, most patients had previously been diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. More patients (60%) in the alirocumab group had diabetes than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (37%). The alirocumab monotherapy group also had a higher percentage of patients with diagnoses of congestive heart failure and used other antihyperlipidemic medications than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. Five patients (25%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 12 patients (20%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group took fish oil. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 2 patients (3%) took gemfibrozil, and 2 patients (3%) took fenofibrate. Six (30%) patients in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 12 (20%) patients in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group had chronic kidney disease. Although the majority of patients in each group did not use tobacco products, there were more tobacco users in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group.

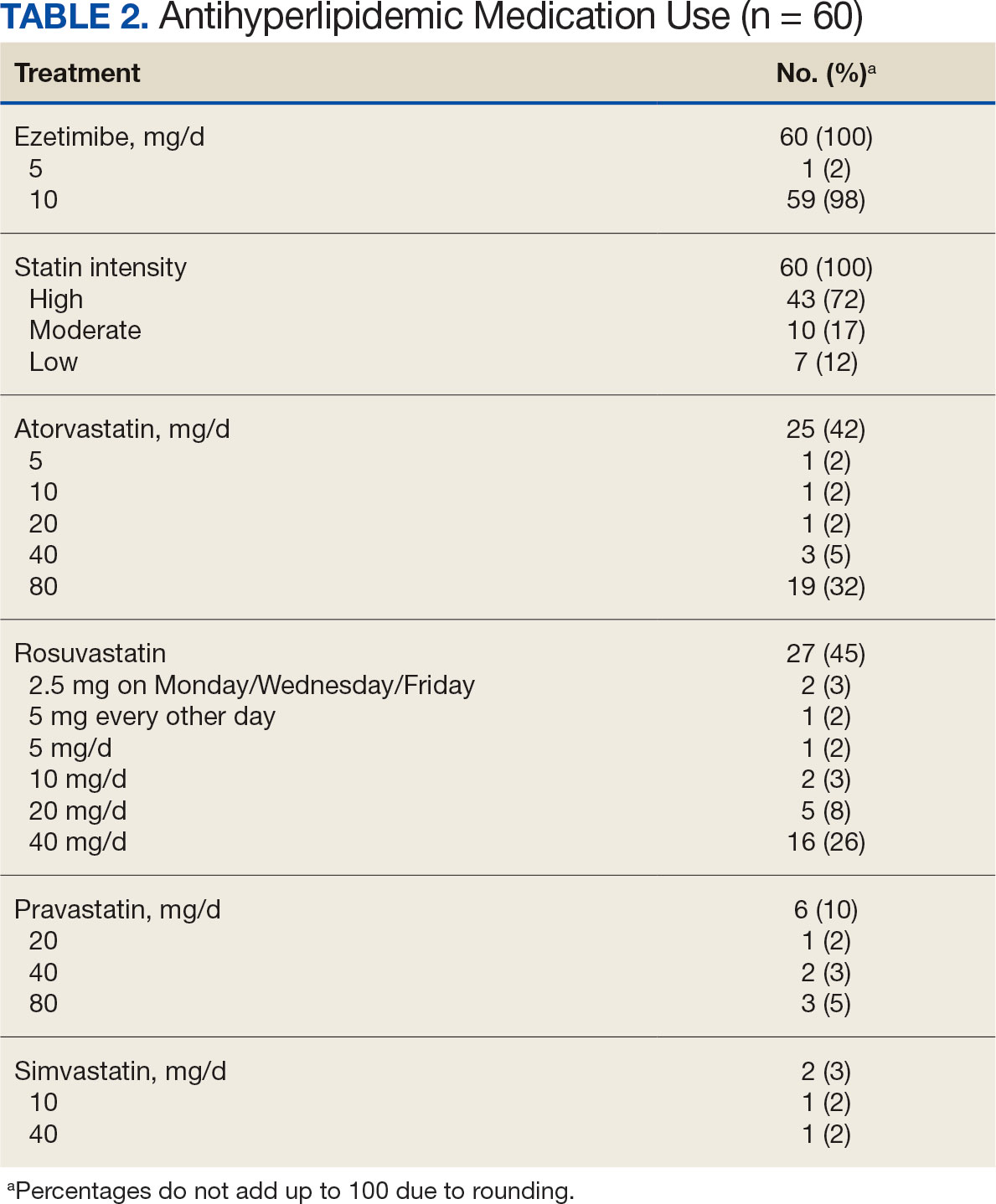

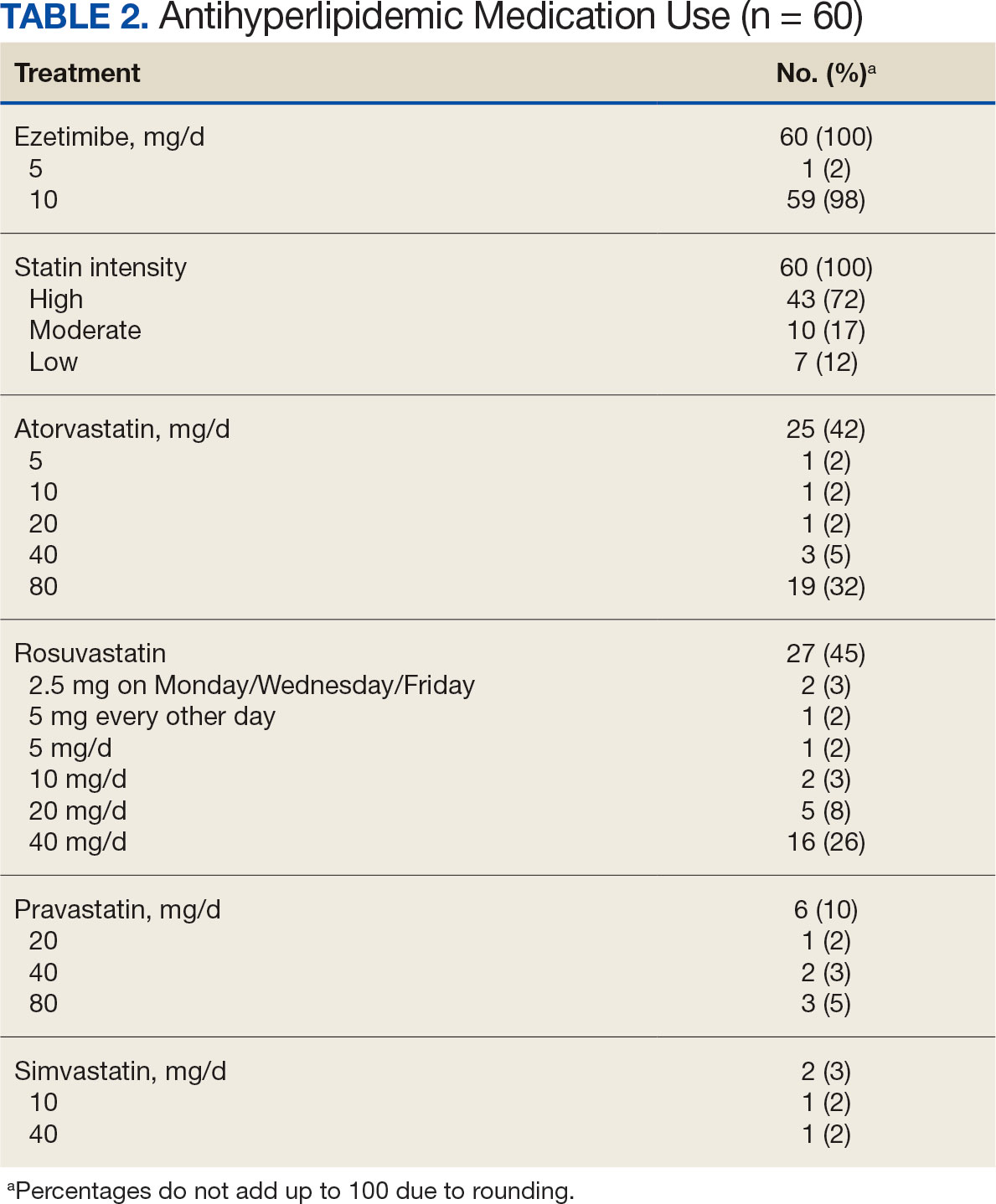

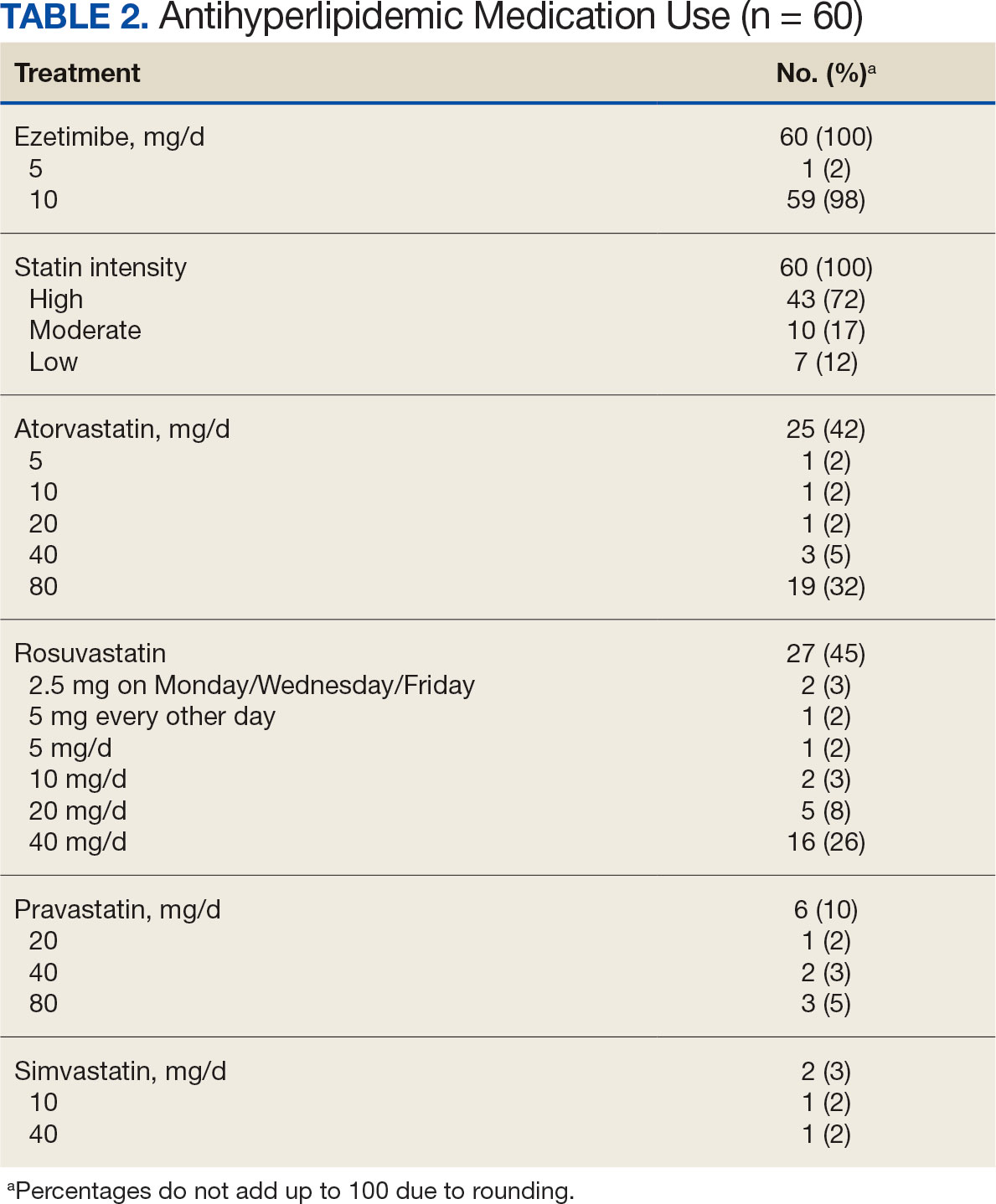

In the alirocumab monotherapy group, 15 patients (75%) were prescribed 75 mg every 2 weeks and 5 patients (25%) were prescribed 150 mg every 2 weeks. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 59 patients (98%) were prescribed ezetimibe 10 mg/d (Table 2). Forty-three patients (72%) were prescribed a high-intensity statin 10 received moderate-intensity (17%) and 7 received low-intensity statin (12%). Most patients were prescribed rosuvastatin (45%), followed by atorvastatin (42%), pravastatin (10%), and simvastatin (3%).

Primary Endpoint

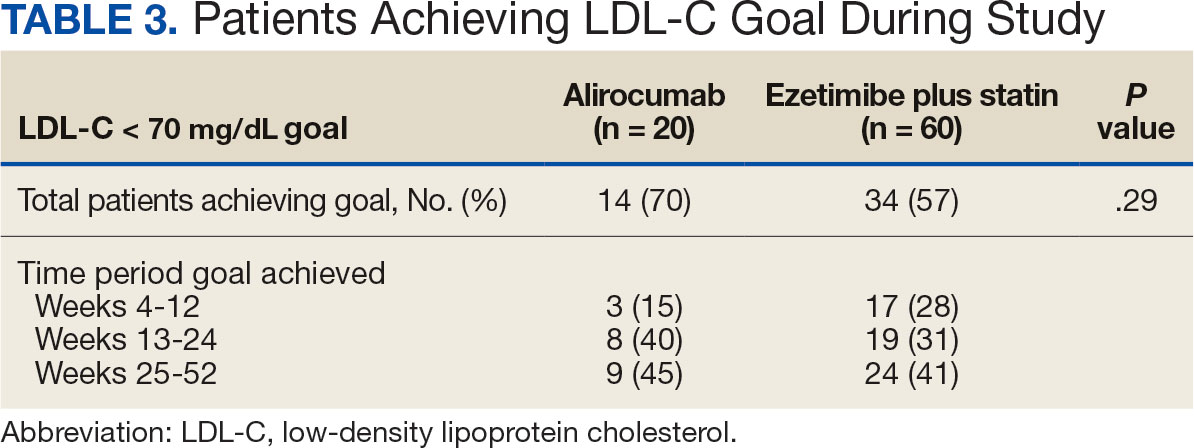

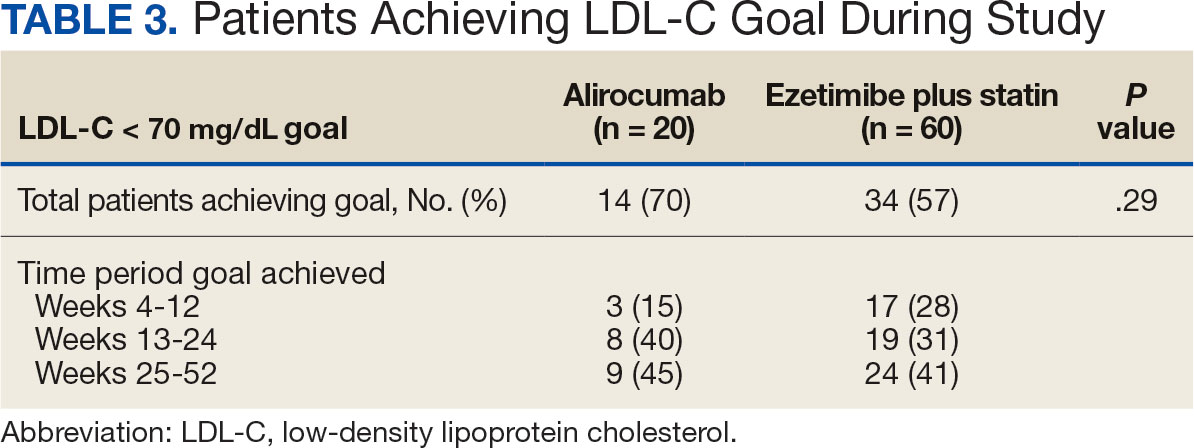

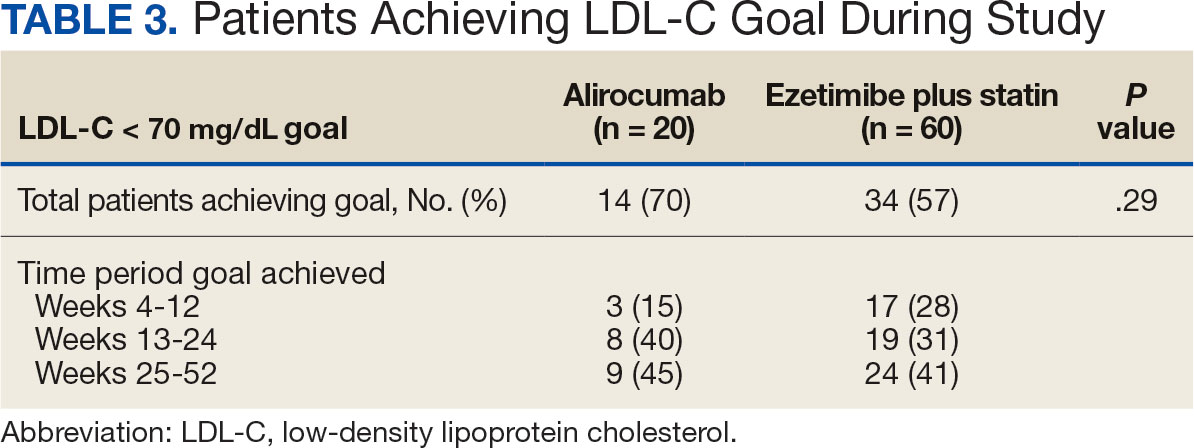

During the 52-week study, more patients met the LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL in the alirocumab monotherapy group (70%) than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (57%); however, the difference was not significant (P = .29). Of the patients prescribed alirocumab monotherapy who achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL, 15% achieved this goal in 4 to 12 weeks, 40% in 13 to 24 weeks, and 45% in 25 to 52 weeks. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 28% of patients achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL in 4 to 12 weeks, 31% in 13 to 24 weeks, and 41% in 25 to 52 weeks (Table 3).

Secondary Endpoints

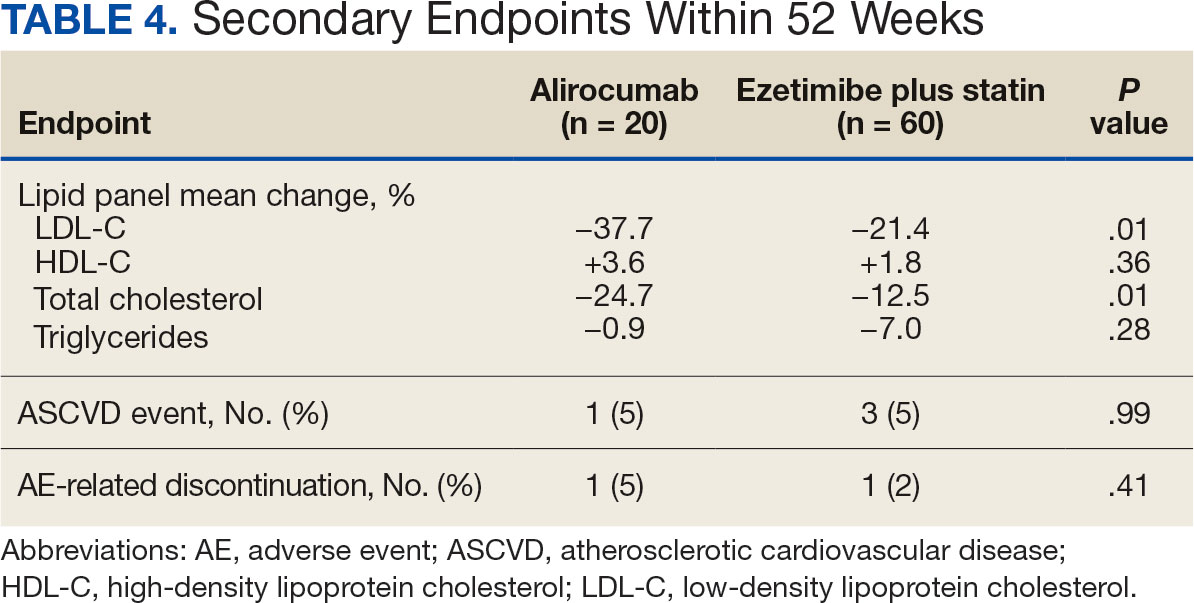

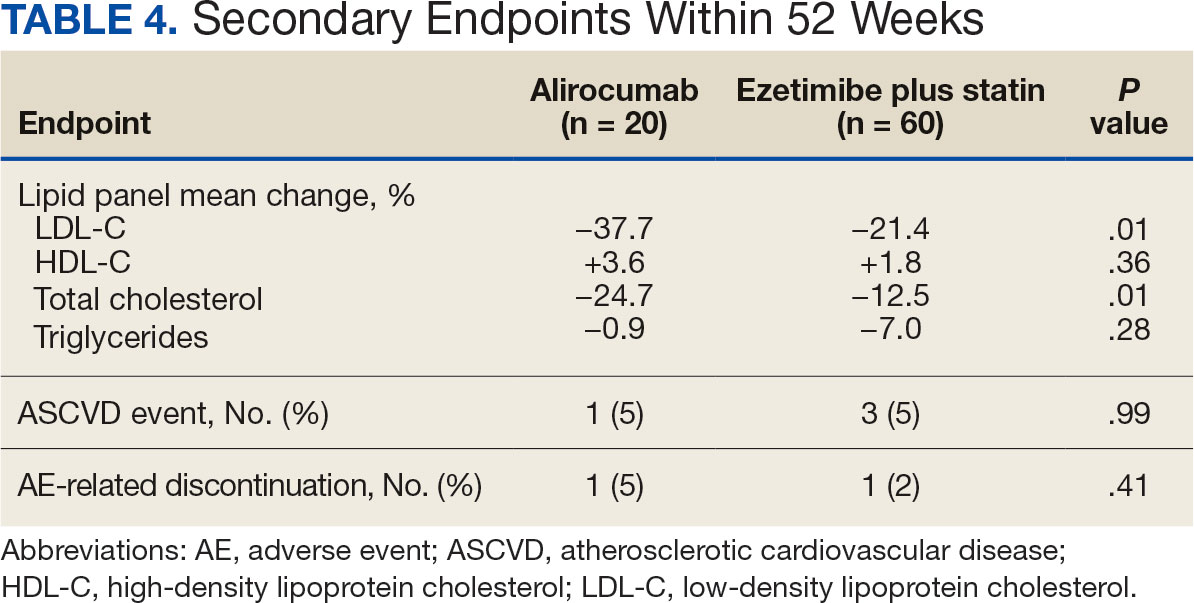

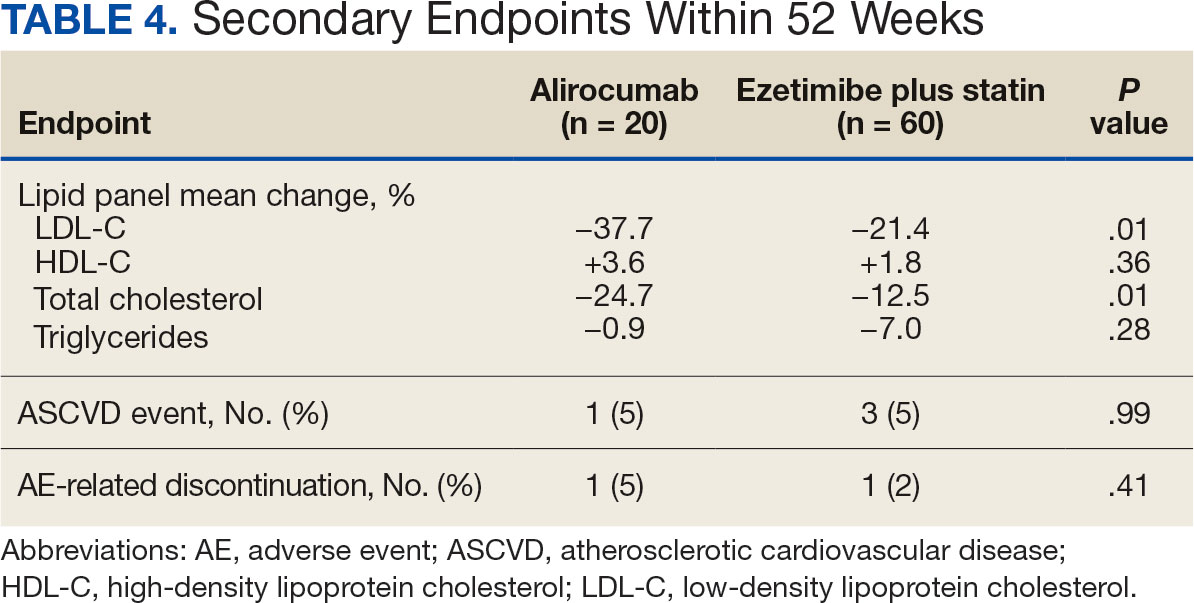

During weeks 4 to 52 of treatment, the mean percentage change decreased in LDL-C (37.7% vs 21.4%; P = .01), TC (24.7% vs 12.5%; P = .01), and TG (0.9% vs 7.0%; P = .28) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, respectively (Table 4). The mean percentage change increased in HDL-C by 3.6% in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 1.8% in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (P = .36). During the study, ASCVD events occurred in 1 patient (5%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 3 patients (5%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (P = .99). The patient in the alirocumab monotherapy group had unstable angina 1 month after taking alirocumab. One patient in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group had coronary artery disease and 2 patients had coronary heart disease that required stents during the 52-week period. There was 1 patient in each group who reported an AE that led to treatment discontinuation (P = .41). One patient stopped alirocumab after a trial of 2 months due to intolerance, but no specific AE was reported in the CPRS. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 1 patient requested to discontinue ezetimibe after a trial of 3 months without a specific reason noted in the medical record.

DISCUSSION

This study found no statistically significant difference in the incidence of reaching an LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL after alirocumab monotherapy initiation compared with ezetimibe plus statin therapy. This occurred despite baseline LDL-C being lower in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, which required a smaller reduction in LDL-C to reach the primary goal. Most patients on alirocumab monotherapy were prescribed a lower initial dose of 75 mg every 2 weeks. Of those patients, 30% did not achieve the LDL-C goal < 70 mg/dL. Thus, a higher dose may have led to more patients achieving the LDL-C goal.

Secondary endpoints, including mean percentage change in HDL-C and TG and incidence of ASCVD events during 52 weeks of treatment, were not statistically significant. The mean percentage increase in HDL-C was negligible in both groups, while the mean percentage reduction in TG favored the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, patients who also took fenofibrate experienced a significant reduction in TG while none of the patients in the alirocumab group were prescribed fenofibrate. Although the alirocumab monotherapy group had a statistically significant greater reduction in LDL-C and TC compared with those prescribed ezetimibe plus statin, the mean baseline LDL-C and TC were significantly greater in the alirocumab monotherapy group, which could contribute to higher reductions in LDL-C and TC after alirocumab monotherapy.Based on the available literature, we expected greater reductions in LDL-C in both study groups compared with statin therapy alone.8,9 However, it was unclear whether the LDL-C and TC reductions were clinically significant.

Limitations

The study design did not permit randomization prior to the treatments, restricting our ability to account for some confounding factors, such as diet, exercise, other antihyperlipidemic medication, and medication adherence, which may have affected LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, and TC levels. Differences in baseline characteristics—particularly major risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use—also could have confounding affect on lipid levels and ASCVD events. Additionally, patients prescribed alirocumab monotherapy may have switched from statin or ezetimibe therapy, and the washout period was not reviewed or recorded, which could have affected the lipid panel results.

The small sample size of this study also may have limited the ability to detect significant differences between groups. A direct comparison of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy has not been performed, making it difficult to prospectively evaluate what sample size would be needed to power this study. A posthoc analysis was used to calculate power, which was found to be only 17%. Many patients were excluded due to a lack of laboratory results within the study period, contributing to the small sample size.

Another limitation was the reliance on documentation in CPRS and JLV. For example, having documentation of the specific AEs for the 2 patients who discontinued alirocumab or ezetimibe could have helped determine the severity of the AEs. Several patients were followed by non-VA clinicians, which could have contributed to limited documentation in the CPRS and JLV. It is difficult to draw any conclusions regarding ASCVD events and AEs that led to treatment discontinuation between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy based on the results of this retrospective study due to the limited number of events within the 52-week period.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found that there was no statistically significant difference in LDL-C reduction to < 70 mg/dL between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy in a small population of veterans with ASCVD, with a higher percentage of participants in both groups achieving that goal in 25 to 52 weeks. There also was no significant difference in percentage change in HDL-C or TG or in incidence of ASCVD events and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation. However, there was a statistically significant difference in percentage reduction for LDL-C and TC during 52 weeks of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy.

Although there was no significant difference in LDL-C reduction to < 70 mg/dL, targeting this goal in patients with ASCVD is still clinically warranted. This study does not support a change in current VA criteria for use of alirocumab or a change in current guidelines for secondary prevention of ASCVD. Still, this study does indicate that the efficacy of alirocumab monotherapy is similar to that of ezetimibe plus statin therapy in patients with a history of ASCVD and may be useful in clinical settings when an alternative to ezetimibe plus statin therapy is needed. Alirocumab also may be more effective in lowering LDL-C and TC than ezetimibe plus statin therapy in veterans with ASCVD and could be added to statin therapy or ezetimibe when additional LDL-C or TC reduction is needed.

Lucchi T. Dyslipidemia and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Minerva Med. 2021;112:804-816. doi:10.23736/S0026-4806.21.07347-X

The Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction. Version 4.0. June 2020. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/lipids/VADoDDyslipidemiaCPG5087212020.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High Cholesterol Facts. May 15, 2024. Accessed October 3, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082-e1143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

Vavlukis M, Vavlukis A. Statins alone or in combination with ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease protection. IntechOpen. January 24, 2019. doi:10.5772/intechopen.82520

Alirocumab. Prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2024. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/praluent_pi.pdf

Pandor A, Ara RM, Tumur I, et al. Ezetimibe monotherapy for cholesterol lowering in 2,722 people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intern Med. 2009;265(5):568-580. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02062.x

McKenney J, Ballantyne CM, Feldman TA, et al. LDL-C goal attainment with ezetimibe plus simvastatin coadministration vs atorvastatin or simvastatin monotherapy in patients at high risk of CHD. MedGenMed. 2005;7(3):3.

Stroes E, Guyton JR, Lepor N, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks in patients with hypercholesterolemia not on statin therapy: the ODYSSEY CHOICE II study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(9):e003421. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003421

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. ASCVD involves the buildup of cholesterol plaque in arteries and includes acute coronary syndrome, peripheral arterial disease, and events such as myocardial infarction and stroke.1 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors include high cholesterol levels, elevated blood pressure, insulin resistance, elevated blood glucose levels, smoking, poor dietary habits, and a sedentary lifestyle.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 86 million adults aged ≥ 20 years have total cholesterol levels > 200 mg/dL. More than half (54.5%) who could benefit are currently taking cholesterol-lowering medications.3 Controlling high cholesterol in American adults, especially veterans, is essential for reducing CVD morbidity and mortality.

The 2018 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline recommends a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) target goal of < 70 mg/dL for patients at high risk for ASCVD. Very high-risk ASCVD includes a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions (eg, age ≥ 65 years, smoking, or diabetes).4 Major ASCVD events include recent acute coronary syndrome (within the past 12 months), a history of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, and symptomatic peripheral artery disease.

The ACC/AHA guideline suggests that if the LDL-C level remains ≥ 70 mg/dL, adding ezetimibe (a dietary cholesterol absorption inhibitor) to maximally tolerated statin therapy is reasonable. If LDL-C levels remain ≥ 70 mg/dL, adding a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor, such as alirocumab, is reasonable.4 The US Departments of Veterans Affairs/US Department of Defense guidelines recommend using maximally tolerated statins and ezetimibe before PCSK9 inhibitors due to established long-term safety and reduction in CVD events.

Generic statins and ezetimibe are administered orally and widely available. In contrast, PCSK9 inhibitors have unknown long-term safety profiles, require subcutaneous injection once or twice monthly, and are significantly more expensive. They also require patient education on proper use while providing comparable or lesser relative risk reductions.2

These 3 classes of medication vary in their mechanisms of action to reduce LDL.5,6 Ezetimibe and several statin medications are included on the Veterans Affairs Sioux Falls Health Care System (VASFHCS) formulary and do not require review prior to prescribing. Alirocumab is available at VASFHCS but is restricted to patients with a history of ASCVD or a diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia, and who are receiving maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy but require further LDL-C lowering to reduce their ASCVD risk.

Studies have found ezetimibe monotherapy reduces LDL-C in patients with dyslipidemia by 18% after 12 weeks.7 One found that the percentage reduction in LDL-C was significantly greater (P < .001) with all doses of ezetimibe plus simvastatin (46% to 59%) compared with either atorvastatin 10 mg (37%) or simvastatin 20 mg (38%) monotherapy after 6 weeks.8

Although alirocumab can be added to other lipid therapies, most VASFHCS patients are prescribed alirocumab monotherapy. In the ODYSSEY CHOICE II study, patients were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo or alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks or alirocumab 75 mg every 2 weeks. The primary efficacy endpoint was LDL-C percentage change from baseline to week 24. In the alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks and 75 mg every 2 weeks groups, the least-squares mean LDL-C changes from baseline to week 24 were 51.7% and 53.5%, respectively, compared to a 4.7% increase in the placebo group (both groups P < .001 vs placebo). The authors also reported that alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks as monotherapy demonstrated a 47.4% reduction in LDL-C levels from baseline in a phase 1 study.9Although alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy have been shown to effectively decrease LDL-C independently, a direct comparison of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy has not been assessed, to our knowledge. Understanding the differences in effectiveness and safety between these 2 regimens will be valuable for clinicians when selecting a medication regimen for veterans with a history of ASCVD.

METHODS

This retrospective, single-center chart review used VASFHCS Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and Joint Longitudinal Viewer (JLV) records to compare patients with a history of ASCVD events who were treated with alirocumab monotherapy or ezetimibe plus statin. The 2 groups were randomized in a 1:3 ratio. The primary endpoint was achieving LDL-C < 70 mg/dL after 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks. Secondary endpoints included the mean percentage change from baseline in total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL-C, and triglycerides (TG) over 52 weeks. The incidence of ASCVD events during this period was also assessed. If LDL-C < 70 mg/dL was achieved > 1 time during each time frame, only 1 incident was counted for analysis. Safety was assessed based on the incidence of any adverse event (AE) that led to treatment discontinuation.

Patients were identified by screening the prescription fill history between October 1, 2019, and December 31, 2022. The 52-week data collection period was counted from the first available fill date. Additionally, the prior authorization drug request file from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2022, was used to obtain a list of patients prescribed alirocumab. Patients were included if they were veterans aged ≥ 18 years and had a history of an ASCVD event, had a alirocumab monotherapy or ezetimibe plus statin prescription between October 1, 2019, and December 31, 2022, or had an approved prior authorization drug request for alirocumab between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2022. Patients missing a baseline or follow-up lipid panel and those with concurrent use of alirocumab and ezetimibe and/or statin were excluded.

Baseline characteristics collected for patients included age, sex, race, weight, body mass index, lipid parameters (LDL-C, TC, HDL-C, and TG), dosing of each type of statin before adding ezetimibe, and use of any other antihyperlipidemic medication. We also collected histories of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, and smoking or tobacco use status. The baseline lipid panel was the most recent lipid panel documented before starting alirocumab or ezetimibe plus statin therapy. Follow-up lipid panel values were gathered at 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks following initiation of either therapy.

High-, moderate-, and low-intensity dosing of statin therapy and alirocumab dosing (75 mg every 2 weeks, 150 mg every 2 weeks, or 300 mg every 4 weeks) were recorded at the specified intervals. However, no patients in this study received the latter dosing regimen. ASCVD events and safety endpoints were recorded based on a review of clinical notes over the 52 weeks following the first available start date.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of achieving the LDL-C < 70 mg/dL goal from baseline to 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks after initiation was compared between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy using the χ² test. Mean percentage change from baseline in TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and TG were compared using the independent t test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Incidence of ASCVD events and the safety endpoint (incidence of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation) were also compared using the χ² test. Continuous baseline characteristics were reported mean (SD) and nominal baseline characteristics were reported as a percentage.

RESULTS

There were 80 participants in this study: 20 in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 60 in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. More than 100 patients did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria and were excluded. Mean (SD) age was 75 (8) years in the alirocumab group and 74 (8) years in the ezetimibe plus statin group. There was no significant differences in mean (SD) weight or mean (SD) body mass index. All study participants identified as White and male except for 2 patients in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group whose race was not documented. Differences in lipid parameters were observed between groups, with mean baseline LDL-C, HDL-C, and TC higher in the alirocumab monotherapy group than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, with significant differences in LDL-C and TC (Table 1).

Fourteen patients (70%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group had hypertension, compared with 31 (52%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. In both groups, most patients had previously been diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. More patients (60%) in the alirocumab group had diabetes than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (37%). The alirocumab monotherapy group also had a higher percentage of patients with diagnoses of congestive heart failure and used other antihyperlipidemic medications than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. Five patients (25%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 12 patients (20%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group took fish oil. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 2 patients (3%) took gemfibrozil, and 2 patients (3%) took fenofibrate. Six (30%) patients in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 12 (20%) patients in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group had chronic kidney disease. Although the majority of patients in each group did not use tobacco products, there were more tobacco users in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group.

In the alirocumab monotherapy group, 15 patients (75%) were prescribed 75 mg every 2 weeks and 5 patients (25%) were prescribed 150 mg every 2 weeks. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 59 patients (98%) were prescribed ezetimibe 10 mg/d (Table 2). Forty-three patients (72%) were prescribed a high-intensity statin 10 received moderate-intensity (17%) and 7 received low-intensity statin (12%). Most patients were prescribed rosuvastatin (45%), followed by atorvastatin (42%), pravastatin (10%), and simvastatin (3%).

Primary Endpoint

During the 52-week study, more patients met the LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL in the alirocumab monotherapy group (70%) than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (57%); however, the difference was not significant (P = .29). Of the patients prescribed alirocumab monotherapy who achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL, 15% achieved this goal in 4 to 12 weeks, 40% in 13 to 24 weeks, and 45% in 25 to 52 weeks. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 28% of patients achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL in 4 to 12 weeks, 31% in 13 to 24 weeks, and 41% in 25 to 52 weeks (Table 3).

Secondary Endpoints

During weeks 4 to 52 of treatment, the mean percentage change decreased in LDL-C (37.7% vs 21.4%; P = .01), TC (24.7% vs 12.5%; P = .01), and TG (0.9% vs 7.0%; P = .28) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, respectively (Table 4). The mean percentage change increased in HDL-C by 3.6% in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 1.8% in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (P = .36). During the study, ASCVD events occurred in 1 patient (5%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 3 patients (5%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (P = .99). The patient in the alirocumab monotherapy group had unstable angina 1 month after taking alirocumab. One patient in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group had coronary artery disease and 2 patients had coronary heart disease that required stents during the 52-week period. There was 1 patient in each group who reported an AE that led to treatment discontinuation (P = .41). One patient stopped alirocumab after a trial of 2 months due to intolerance, but no specific AE was reported in the CPRS. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 1 patient requested to discontinue ezetimibe after a trial of 3 months without a specific reason noted in the medical record.

DISCUSSION

This study found no statistically significant difference in the incidence of reaching an LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL after alirocumab monotherapy initiation compared with ezetimibe plus statin therapy. This occurred despite baseline LDL-C being lower in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, which required a smaller reduction in LDL-C to reach the primary goal. Most patients on alirocumab monotherapy were prescribed a lower initial dose of 75 mg every 2 weeks. Of those patients, 30% did not achieve the LDL-C goal < 70 mg/dL. Thus, a higher dose may have led to more patients achieving the LDL-C goal.

Secondary endpoints, including mean percentage change in HDL-C and TG and incidence of ASCVD events during 52 weeks of treatment, were not statistically significant. The mean percentage increase in HDL-C was negligible in both groups, while the mean percentage reduction in TG favored the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, patients who also took fenofibrate experienced a significant reduction in TG while none of the patients in the alirocumab group were prescribed fenofibrate. Although the alirocumab monotherapy group had a statistically significant greater reduction in LDL-C and TC compared with those prescribed ezetimibe plus statin, the mean baseline LDL-C and TC were significantly greater in the alirocumab monotherapy group, which could contribute to higher reductions in LDL-C and TC after alirocumab monotherapy.Based on the available literature, we expected greater reductions in LDL-C in both study groups compared with statin therapy alone.8,9 However, it was unclear whether the LDL-C and TC reductions were clinically significant.

Limitations

The study design did not permit randomization prior to the treatments, restricting our ability to account for some confounding factors, such as diet, exercise, other antihyperlipidemic medication, and medication adherence, which may have affected LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, and TC levels. Differences in baseline characteristics—particularly major risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use—also could have confounding affect on lipid levels and ASCVD events. Additionally, patients prescribed alirocumab monotherapy may have switched from statin or ezetimibe therapy, and the washout period was not reviewed or recorded, which could have affected the lipid panel results.

The small sample size of this study also may have limited the ability to detect significant differences between groups. A direct comparison of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy has not been performed, making it difficult to prospectively evaluate what sample size would be needed to power this study. A posthoc analysis was used to calculate power, which was found to be only 17%. Many patients were excluded due to a lack of laboratory results within the study period, contributing to the small sample size.

Another limitation was the reliance on documentation in CPRS and JLV. For example, having documentation of the specific AEs for the 2 patients who discontinued alirocumab or ezetimibe could have helped determine the severity of the AEs. Several patients were followed by non-VA clinicians, which could have contributed to limited documentation in the CPRS and JLV. It is difficult to draw any conclusions regarding ASCVD events and AEs that led to treatment discontinuation between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy based on the results of this retrospective study due to the limited number of events within the 52-week period.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found that there was no statistically significant difference in LDL-C reduction to < 70 mg/dL between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy in a small population of veterans with ASCVD, with a higher percentage of participants in both groups achieving that goal in 25 to 52 weeks. There also was no significant difference in percentage change in HDL-C or TG or in incidence of ASCVD events and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation. However, there was a statistically significant difference in percentage reduction for LDL-C and TC during 52 weeks of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy.

Although there was no significant difference in LDL-C reduction to < 70 mg/dL, targeting this goal in patients with ASCVD is still clinically warranted. This study does not support a change in current VA criteria for use of alirocumab or a change in current guidelines for secondary prevention of ASCVD. Still, this study does indicate that the efficacy of alirocumab monotherapy is similar to that of ezetimibe plus statin therapy in patients with a history of ASCVD and may be useful in clinical settings when an alternative to ezetimibe plus statin therapy is needed. Alirocumab also may be more effective in lowering LDL-C and TC than ezetimibe plus statin therapy in veterans with ASCVD and could be added to statin therapy or ezetimibe when additional LDL-C or TC reduction is needed.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. ASCVD involves the buildup of cholesterol plaque in arteries and includes acute coronary syndrome, peripheral arterial disease, and events such as myocardial infarction and stroke.1 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors include high cholesterol levels, elevated blood pressure, insulin resistance, elevated blood glucose levels, smoking, poor dietary habits, and a sedentary lifestyle.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 86 million adults aged ≥ 20 years have total cholesterol levels > 200 mg/dL. More than half (54.5%) who could benefit are currently taking cholesterol-lowering medications.3 Controlling high cholesterol in American adults, especially veterans, is essential for reducing CVD morbidity and mortality.

The 2018 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline recommends a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) target goal of < 70 mg/dL for patients at high risk for ASCVD. Very high-risk ASCVD includes a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions (eg, age ≥ 65 years, smoking, or diabetes).4 Major ASCVD events include recent acute coronary syndrome (within the past 12 months), a history of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, and symptomatic peripheral artery disease.

The ACC/AHA guideline suggests that if the LDL-C level remains ≥ 70 mg/dL, adding ezetimibe (a dietary cholesterol absorption inhibitor) to maximally tolerated statin therapy is reasonable. If LDL-C levels remain ≥ 70 mg/dL, adding a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor, such as alirocumab, is reasonable.4 The US Departments of Veterans Affairs/US Department of Defense guidelines recommend using maximally tolerated statins and ezetimibe before PCSK9 inhibitors due to established long-term safety and reduction in CVD events.

Generic statins and ezetimibe are administered orally and widely available. In contrast, PCSK9 inhibitors have unknown long-term safety profiles, require subcutaneous injection once or twice monthly, and are significantly more expensive. They also require patient education on proper use while providing comparable or lesser relative risk reductions.2

These 3 classes of medication vary in their mechanisms of action to reduce LDL.5,6 Ezetimibe and several statin medications are included on the Veterans Affairs Sioux Falls Health Care System (VASFHCS) formulary and do not require review prior to prescribing. Alirocumab is available at VASFHCS but is restricted to patients with a history of ASCVD or a diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia, and who are receiving maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy but require further LDL-C lowering to reduce their ASCVD risk.

Studies have found ezetimibe monotherapy reduces LDL-C in patients with dyslipidemia by 18% after 12 weeks.7 One found that the percentage reduction in LDL-C was significantly greater (P < .001) with all doses of ezetimibe plus simvastatin (46% to 59%) compared with either atorvastatin 10 mg (37%) or simvastatin 20 mg (38%) monotherapy after 6 weeks.8

Although alirocumab can be added to other lipid therapies, most VASFHCS patients are prescribed alirocumab monotherapy. In the ODYSSEY CHOICE II study, patients were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo or alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks or alirocumab 75 mg every 2 weeks. The primary efficacy endpoint was LDL-C percentage change from baseline to week 24. In the alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks and 75 mg every 2 weeks groups, the least-squares mean LDL-C changes from baseline to week 24 were 51.7% and 53.5%, respectively, compared to a 4.7% increase in the placebo group (both groups P < .001 vs placebo). The authors also reported that alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks as monotherapy demonstrated a 47.4% reduction in LDL-C levels from baseline in a phase 1 study.9Although alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy have been shown to effectively decrease LDL-C independently, a direct comparison of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy has not been assessed, to our knowledge. Understanding the differences in effectiveness and safety between these 2 regimens will be valuable for clinicians when selecting a medication regimen for veterans with a history of ASCVD.

METHODS

This retrospective, single-center chart review used VASFHCS Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and Joint Longitudinal Viewer (JLV) records to compare patients with a history of ASCVD events who were treated with alirocumab monotherapy or ezetimibe plus statin. The 2 groups were randomized in a 1:3 ratio. The primary endpoint was achieving LDL-C < 70 mg/dL after 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks. Secondary endpoints included the mean percentage change from baseline in total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL-C, and triglycerides (TG) over 52 weeks. The incidence of ASCVD events during this period was also assessed. If LDL-C < 70 mg/dL was achieved > 1 time during each time frame, only 1 incident was counted for analysis. Safety was assessed based on the incidence of any adverse event (AE) that led to treatment discontinuation.

Patients were identified by screening the prescription fill history between October 1, 2019, and December 31, 2022. The 52-week data collection period was counted from the first available fill date. Additionally, the prior authorization drug request file from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2022, was used to obtain a list of patients prescribed alirocumab. Patients were included if they were veterans aged ≥ 18 years and had a history of an ASCVD event, had a alirocumab monotherapy or ezetimibe plus statin prescription between October 1, 2019, and December 31, 2022, or had an approved prior authorization drug request for alirocumab between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2022. Patients missing a baseline or follow-up lipid panel and those with concurrent use of alirocumab and ezetimibe and/or statin were excluded.

Baseline characteristics collected for patients included age, sex, race, weight, body mass index, lipid parameters (LDL-C, TC, HDL-C, and TG), dosing of each type of statin before adding ezetimibe, and use of any other antihyperlipidemic medication. We also collected histories of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, and smoking or tobacco use status. The baseline lipid panel was the most recent lipid panel documented before starting alirocumab or ezetimibe plus statin therapy. Follow-up lipid panel values were gathered at 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks following initiation of either therapy.

High-, moderate-, and low-intensity dosing of statin therapy and alirocumab dosing (75 mg every 2 weeks, 150 mg every 2 weeks, or 300 mg every 4 weeks) were recorded at the specified intervals. However, no patients in this study received the latter dosing regimen. ASCVD events and safety endpoints were recorded based on a review of clinical notes over the 52 weeks following the first available start date.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of achieving the LDL-C < 70 mg/dL goal from baseline to 4 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks, and 25 to 52 weeks after initiation was compared between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy using the χ² test. Mean percentage change from baseline in TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and TG were compared using the independent t test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Incidence of ASCVD events and the safety endpoint (incidence of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation) were also compared using the χ² test. Continuous baseline characteristics were reported mean (SD) and nominal baseline characteristics were reported as a percentage.

RESULTS

There were 80 participants in this study: 20 in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 60 in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. More than 100 patients did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria and were excluded. Mean (SD) age was 75 (8) years in the alirocumab group and 74 (8) years in the ezetimibe plus statin group. There was no significant differences in mean (SD) weight or mean (SD) body mass index. All study participants identified as White and male except for 2 patients in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group whose race was not documented. Differences in lipid parameters were observed between groups, with mean baseline LDL-C, HDL-C, and TC higher in the alirocumab monotherapy group than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, with significant differences in LDL-C and TC (Table 1).

Fourteen patients (70%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group had hypertension, compared with 31 (52%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. In both groups, most patients had previously been diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. More patients (60%) in the alirocumab group had diabetes than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (37%). The alirocumab monotherapy group also had a higher percentage of patients with diagnoses of congestive heart failure and used other antihyperlipidemic medications than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. Five patients (25%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 12 patients (20%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group took fish oil. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 2 patients (3%) took gemfibrozil, and 2 patients (3%) took fenofibrate. Six (30%) patients in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 12 (20%) patients in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group had chronic kidney disease. Although the majority of patients in each group did not use tobacco products, there were more tobacco users in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group.

In the alirocumab monotherapy group, 15 patients (75%) were prescribed 75 mg every 2 weeks and 5 patients (25%) were prescribed 150 mg every 2 weeks. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 59 patients (98%) were prescribed ezetimibe 10 mg/d (Table 2). Forty-three patients (72%) were prescribed a high-intensity statin 10 received moderate-intensity (17%) and 7 received low-intensity statin (12%). Most patients were prescribed rosuvastatin (45%), followed by atorvastatin (42%), pravastatin (10%), and simvastatin (3%).

Primary Endpoint

During the 52-week study, more patients met the LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL in the alirocumab monotherapy group (70%) than in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (57%); however, the difference was not significant (P = .29). Of the patients prescribed alirocumab monotherapy who achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL, 15% achieved this goal in 4 to 12 weeks, 40% in 13 to 24 weeks, and 45% in 25 to 52 weeks. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 28% of patients achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL in 4 to 12 weeks, 31% in 13 to 24 weeks, and 41% in 25 to 52 weeks (Table 3).

Secondary Endpoints

During weeks 4 to 52 of treatment, the mean percentage change decreased in LDL-C (37.7% vs 21.4%; P = .01), TC (24.7% vs 12.5%; P = .01), and TG (0.9% vs 7.0%; P = .28) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, respectively (Table 4). The mean percentage change increased in HDL-C by 3.6% in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 1.8% in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (P = .36). During the study, ASCVD events occurred in 1 patient (5%) in the alirocumab monotherapy group and 3 patients (5%) in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group (P = .99). The patient in the alirocumab monotherapy group had unstable angina 1 month after taking alirocumab. One patient in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group had coronary artery disease and 2 patients had coronary heart disease that required stents during the 52-week period. There was 1 patient in each group who reported an AE that led to treatment discontinuation (P = .41). One patient stopped alirocumab after a trial of 2 months due to intolerance, but no specific AE was reported in the CPRS. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, 1 patient requested to discontinue ezetimibe after a trial of 3 months without a specific reason noted in the medical record.

DISCUSSION

This study found no statistically significant difference in the incidence of reaching an LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL after alirocumab monotherapy initiation compared with ezetimibe plus statin therapy. This occurred despite baseline LDL-C being lower in the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, which required a smaller reduction in LDL-C to reach the primary goal. Most patients on alirocumab monotherapy were prescribed a lower initial dose of 75 mg every 2 weeks. Of those patients, 30% did not achieve the LDL-C goal < 70 mg/dL. Thus, a higher dose may have led to more patients achieving the LDL-C goal.

Secondary endpoints, including mean percentage change in HDL-C and TG and incidence of ASCVD events during 52 weeks of treatment, were not statistically significant. The mean percentage increase in HDL-C was negligible in both groups, while the mean percentage reduction in TG favored the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group. In the ezetimibe plus statin therapy group, patients who also took fenofibrate experienced a significant reduction in TG while none of the patients in the alirocumab group were prescribed fenofibrate. Although the alirocumab monotherapy group had a statistically significant greater reduction in LDL-C and TC compared with those prescribed ezetimibe plus statin, the mean baseline LDL-C and TC were significantly greater in the alirocumab monotherapy group, which could contribute to higher reductions in LDL-C and TC after alirocumab monotherapy.Based on the available literature, we expected greater reductions in LDL-C in both study groups compared with statin therapy alone.8,9 However, it was unclear whether the LDL-C and TC reductions were clinically significant.

Limitations

The study design did not permit randomization prior to the treatments, restricting our ability to account for some confounding factors, such as diet, exercise, other antihyperlipidemic medication, and medication adherence, which may have affected LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, and TC levels. Differences in baseline characteristics—particularly major risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use—also could have confounding affect on lipid levels and ASCVD events. Additionally, patients prescribed alirocumab monotherapy may have switched from statin or ezetimibe therapy, and the washout period was not reviewed or recorded, which could have affected the lipid panel results.

The small sample size of this study also may have limited the ability to detect significant differences between groups. A direct comparison of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy has not been performed, making it difficult to prospectively evaluate what sample size would be needed to power this study. A posthoc analysis was used to calculate power, which was found to be only 17%. Many patients were excluded due to a lack of laboratory results within the study period, contributing to the small sample size.

Another limitation was the reliance on documentation in CPRS and JLV. For example, having documentation of the specific AEs for the 2 patients who discontinued alirocumab or ezetimibe could have helped determine the severity of the AEs. Several patients were followed by non-VA clinicians, which could have contributed to limited documentation in the CPRS and JLV. It is difficult to draw any conclusions regarding ASCVD events and AEs that led to treatment discontinuation between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy based on the results of this retrospective study due to the limited number of events within the 52-week period.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found that there was no statistically significant difference in LDL-C reduction to < 70 mg/dL between alirocumab monotherapy and ezetimibe plus statin therapy in a small population of veterans with ASCVD, with a higher percentage of participants in both groups achieving that goal in 25 to 52 weeks. There also was no significant difference in percentage change in HDL-C or TG or in incidence of ASCVD events and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation. However, there was a statistically significant difference in percentage reduction for LDL-C and TC during 52 weeks of alirocumab monotherapy vs ezetimibe plus statin therapy.

Although there was no significant difference in LDL-C reduction to < 70 mg/dL, targeting this goal in patients with ASCVD is still clinically warranted. This study does not support a change in current VA criteria for use of alirocumab or a change in current guidelines for secondary prevention of ASCVD. Still, this study does indicate that the efficacy of alirocumab monotherapy is similar to that of ezetimibe plus statin therapy in patients with a history of ASCVD and may be useful in clinical settings when an alternative to ezetimibe plus statin therapy is needed. Alirocumab also may be more effective in lowering LDL-C and TC than ezetimibe plus statin therapy in veterans with ASCVD and could be added to statin therapy or ezetimibe when additional LDL-C or TC reduction is needed.

Lucchi T. Dyslipidemia and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Minerva Med. 2021;112:804-816. doi:10.23736/S0026-4806.21.07347-X

The Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction. Version 4.0. June 2020. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/lipids/VADoDDyslipidemiaCPG5087212020.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High Cholesterol Facts. May 15, 2024. Accessed October 3, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082-e1143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

Vavlukis M, Vavlukis A. Statins alone or in combination with ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease protection. IntechOpen. January 24, 2019. doi:10.5772/intechopen.82520

Alirocumab. Prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2024. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/praluent_pi.pdf

Pandor A, Ara RM, Tumur I, et al. Ezetimibe monotherapy for cholesterol lowering in 2,722 people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intern Med. 2009;265(5):568-580. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02062.x

McKenney J, Ballantyne CM, Feldman TA, et al. LDL-C goal attainment with ezetimibe plus simvastatin coadministration vs atorvastatin or simvastatin monotherapy in patients at high risk of CHD. MedGenMed. 2005;7(3):3.

Stroes E, Guyton JR, Lepor N, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks in patients with hypercholesterolemia not on statin therapy: the ODYSSEY CHOICE II study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(9):e003421. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003421

Lucchi T. Dyslipidemia and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Minerva Med. 2021;112:804-816. doi:10.23736/S0026-4806.21.07347-X

The Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction. Version 4.0. June 2020. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/lipids/VADoDDyslipidemiaCPG5087212020.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High Cholesterol Facts. May 15, 2024. Accessed October 3, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082-e1143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

Vavlukis M, Vavlukis A. Statins alone or in combination with ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease protection. IntechOpen. January 24, 2019. doi:10.5772/intechopen.82520

Alirocumab. Prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2024. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/praluent_pi.pdf

Pandor A, Ara RM, Tumur I, et al. Ezetimibe monotherapy for cholesterol lowering in 2,722 people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intern Med. 2009;265(5):568-580. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02062.x

McKenney J, Ballantyne CM, Feldman TA, et al. LDL-C goal attainment with ezetimibe plus simvastatin coadministration vs atorvastatin or simvastatin monotherapy in patients at high risk of CHD. MedGenMed. 2005;7(3):3.

Stroes E, Guyton JR, Lepor N, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab 150 mg every 4 weeks in patients with hypercholesterolemia not on statin therapy: the ODYSSEY CHOICE II study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(9):e003421. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003421