User login

Getting the most out of a psychiatric consultation

You’ve been struggling with what to do for a patient who has a significant mental health problem and really would love to have some help. You’re willing to fill out the requisite referral forms and wait your turn for what seems like an excruciating amount of time. But how do you ensure that you, your patient, and the family get the most out of the consultative experience so that everyone’s questions are answered and ongoing care, if needed, can continue?

To be fair, most of the burden of doing a good psychiatric or mental health consultation rests on the consultant, not the person making the request. It is their job to do a thorough evaluation and to identify any additional pieces of information that may be missing before a strong conclusion can be made. That said, however, this is the real world where everyone is busy and few have the time to track down every loose end that may exist regarding a patient’s history.

To that end, here are some recommendations for how to increase the chance that the outcome of your consultation with a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional will be maximally helpful for everyone involved. These tips are based on having been on the receiving end of psychiatric consultations for almost 2 decades and having worked closely with primary care clinicians in a number of different capacities.

The first question to ask yourself, and this may be the most important one of all, is whether or not you really need an actual psychiatrist at all at this stage versus another type of mental health professional. Physicians often are most comfortable dealing with other physicians. If a pediatrician has a question about a patient’s heart, it’s logical to consult a cardiologist. Thus if there’s a question about mental health, the knee-jerk reaction is to consult a psychiatrist. While understandable, looking first to a psychiatrist to help with a patient’s mental health struggles often is not the best move. Psychiatrists make up only one small part of all mental health professionals that also include psychologists, counselors, and clinical social workers, among others. The availability of child and adolescent psychiatrists can been exceedingly sparse while other types of mental health professionals generally are much more available. Moreover, these other types of mental health professionals also can do a great job at assessment and treatment. It is true that most can’t prescribe medication, but best practice recommendations for most of the common mental health diagnoses in youth (anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, etc.) explicitly outline that nonpharmacologic treatments should be used first. It breaks my heart every time I do a consult for a family who has waited 6 months only to have me recommend a good therapist they could have seen right off in a week.

Get to know the mental health resources of your community beyond the small number of psychiatrists who might be there. And if you aren’t sure whether or not a referral might best go first to a mental health professional who is not a psychiatrist, just ask. That quick phone call or email might save the family a needless delay in treatment and a lot of aggravation for you.

If you are confident that it is a child & adolescent psychiatrist you want your patient to see, here are some things that will help you get the most out of that consultation and help you avoid the disappointment (for both you and the family) of an evaluation that completely misses the mark.

Select the best site (if you have an option)

Broadly speaking, psychiatrists often can be found in three main areas: academic clinics, private practice, and community mental health centers. While of course there is huge variation of clinicians at each of the sites, some generalizations regarding typical advantages and disadvantages of each setting are probably fair.

Academic settings often have psychiatrists who are local or even national experts on particular topics and can be good places to get evaluations for patients with complicated histories. At the same time, however, these settings typically rely on trainees to do much of the actual work. Many of the residents and fellows are excellent, but they turn over quickly because of graduation and finishing rotations, which can force patients to get to know a lot of different people. Academic centers also can be quite a distance from a family’s home, which often makes follow-up care a challenge (especially when we go back to more in-person visits).

Private practice psychiatrists can provide a more local option and can give families access to experienced clinicians, but many of these practices (especially the ones that take insurance) have practice models that involve seeing a lot of patients for short amounts of time and with less coordination with other types of services.

Finally, psychiatrists working at community mental health centers often work in teams that can help families get access to a lot of useful ancillary services (case management, home supports, etc.) but are part of a public mental health system that sadly is all too often overstretched and underfunded.

If you have choices for where to go for psychiatric services, keeping these things in mind can help you find the best fit for families.

Provide a medication history

While I’m not a big fan of the “what medicine do I try next?” consultation, don’t rely on families to provide this information accurately. Medications are confusing, and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard: “I tried the little blue pill and then the big white capsule.” Nobody feels good if the end result of a long consultative process includes a recommendation for a medication that the patient has already tried and failed. Some EMRs now have this information in a way that can be more easily packaged and shared.

State what you are looking for

If you really want the psychiatrist to take over the care of the patient, are just looking for some guidance for what to do next, or are seeking a second opinion for a patient that already works with a psychiatrist, stating so specifically can help tailor the consultation to best address the situation.

Send along past evaluations

Many patients have accumulated detailed psychological or educational evaluations over time that can include some really important information like cognitive profiles, other diagnostic impressions, and past treatment recommendations that may or may not have been implemented. Having these available to the consulting psychiatrist (of course parents need to give permission to send these along) can help the consultant avoid asking redundant questions or recommend things that already have been tried.

Rule outs of medical causes

There are a lot of psychiatric symptoms that can be caused by nonpsychiatric causes. Sometimes, there can be an assumption on the part of the psychiatrist that the pediatrician already has evaluated for these possibilities while the pediatrician assumes that the psychiatrist will work those up if needed. This is how the care of some patients fall through the cracks, and how those unflattering stories of how patients were forced to live with undiagnosed ailments (seizures, encephalopathy, Lyme disease, etc.) for years are generated. Being clear what work-up and tests already have been done to look for other causes can help everyone involved decide what should be done next and who should do it.

Yes, it is true that most of the recommendations specified here involve more work that the quick “behavioral problems: eval and treat” note that may be tempting to write when consulting with a mental health professional, but they will help avoid a lot of headaches for you down the road and, most importantly, get patients and families the timely and comprehensive care they deserve.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rettew at pdnews@mdedge.com.

You’ve been struggling with what to do for a patient who has a significant mental health problem and really would love to have some help. You’re willing to fill out the requisite referral forms and wait your turn for what seems like an excruciating amount of time. But how do you ensure that you, your patient, and the family get the most out of the consultative experience so that everyone’s questions are answered and ongoing care, if needed, can continue?

To be fair, most of the burden of doing a good psychiatric or mental health consultation rests on the consultant, not the person making the request. It is their job to do a thorough evaluation and to identify any additional pieces of information that may be missing before a strong conclusion can be made. That said, however, this is the real world where everyone is busy and few have the time to track down every loose end that may exist regarding a patient’s history.

To that end, here are some recommendations for how to increase the chance that the outcome of your consultation with a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional will be maximally helpful for everyone involved. These tips are based on having been on the receiving end of psychiatric consultations for almost 2 decades and having worked closely with primary care clinicians in a number of different capacities.

The first question to ask yourself, and this may be the most important one of all, is whether or not you really need an actual psychiatrist at all at this stage versus another type of mental health professional. Physicians often are most comfortable dealing with other physicians. If a pediatrician has a question about a patient’s heart, it’s logical to consult a cardiologist. Thus if there’s a question about mental health, the knee-jerk reaction is to consult a psychiatrist. While understandable, looking first to a psychiatrist to help with a patient’s mental health struggles often is not the best move. Psychiatrists make up only one small part of all mental health professionals that also include psychologists, counselors, and clinical social workers, among others. The availability of child and adolescent psychiatrists can been exceedingly sparse while other types of mental health professionals generally are much more available. Moreover, these other types of mental health professionals also can do a great job at assessment and treatment. It is true that most can’t prescribe medication, but best practice recommendations for most of the common mental health diagnoses in youth (anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, etc.) explicitly outline that nonpharmacologic treatments should be used first. It breaks my heart every time I do a consult for a family who has waited 6 months only to have me recommend a good therapist they could have seen right off in a week.

Get to know the mental health resources of your community beyond the small number of psychiatrists who might be there. And if you aren’t sure whether or not a referral might best go first to a mental health professional who is not a psychiatrist, just ask. That quick phone call or email might save the family a needless delay in treatment and a lot of aggravation for you.

If you are confident that it is a child & adolescent psychiatrist you want your patient to see, here are some things that will help you get the most out of that consultation and help you avoid the disappointment (for both you and the family) of an evaluation that completely misses the mark.

Select the best site (if you have an option)

Broadly speaking, psychiatrists often can be found in three main areas: academic clinics, private practice, and community mental health centers. While of course there is huge variation of clinicians at each of the sites, some generalizations regarding typical advantages and disadvantages of each setting are probably fair.

Academic settings often have psychiatrists who are local or even national experts on particular topics and can be good places to get evaluations for patients with complicated histories. At the same time, however, these settings typically rely on trainees to do much of the actual work. Many of the residents and fellows are excellent, but they turn over quickly because of graduation and finishing rotations, which can force patients to get to know a lot of different people. Academic centers also can be quite a distance from a family’s home, which often makes follow-up care a challenge (especially when we go back to more in-person visits).

Private practice psychiatrists can provide a more local option and can give families access to experienced clinicians, but many of these practices (especially the ones that take insurance) have practice models that involve seeing a lot of patients for short amounts of time and with less coordination with other types of services.

Finally, psychiatrists working at community mental health centers often work in teams that can help families get access to a lot of useful ancillary services (case management, home supports, etc.) but are part of a public mental health system that sadly is all too often overstretched and underfunded.

If you have choices for where to go for psychiatric services, keeping these things in mind can help you find the best fit for families.

Provide a medication history

While I’m not a big fan of the “what medicine do I try next?” consultation, don’t rely on families to provide this information accurately. Medications are confusing, and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard: “I tried the little blue pill and then the big white capsule.” Nobody feels good if the end result of a long consultative process includes a recommendation for a medication that the patient has already tried and failed. Some EMRs now have this information in a way that can be more easily packaged and shared.

State what you are looking for

If you really want the psychiatrist to take over the care of the patient, are just looking for some guidance for what to do next, or are seeking a second opinion for a patient that already works with a psychiatrist, stating so specifically can help tailor the consultation to best address the situation.

Send along past evaluations

Many patients have accumulated detailed psychological or educational evaluations over time that can include some really important information like cognitive profiles, other diagnostic impressions, and past treatment recommendations that may or may not have been implemented. Having these available to the consulting psychiatrist (of course parents need to give permission to send these along) can help the consultant avoid asking redundant questions or recommend things that already have been tried.

Rule outs of medical causes

There are a lot of psychiatric symptoms that can be caused by nonpsychiatric causes. Sometimes, there can be an assumption on the part of the psychiatrist that the pediatrician already has evaluated for these possibilities while the pediatrician assumes that the psychiatrist will work those up if needed. This is how the care of some patients fall through the cracks, and how those unflattering stories of how patients were forced to live with undiagnosed ailments (seizures, encephalopathy, Lyme disease, etc.) for years are generated. Being clear what work-up and tests already have been done to look for other causes can help everyone involved decide what should be done next and who should do it.

Yes, it is true that most of the recommendations specified here involve more work that the quick “behavioral problems: eval and treat” note that may be tempting to write when consulting with a mental health professional, but they will help avoid a lot of headaches for you down the road and, most importantly, get patients and families the timely and comprehensive care they deserve.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rettew at pdnews@mdedge.com.

You’ve been struggling with what to do for a patient who has a significant mental health problem and really would love to have some help. You’re willing to fill out the requisite referral forms and wait your turn for what seems like an excruciating amount of time. But how do you ensure that you, your patient, and the family get the most out of the consultative experience so that everyone’s questions are answered and ongoing care, if needed, can continue?

To be fair, most of the burden of doing a good psychiatric or mental health consultation rests on the consultant, not the person making the request. It is their job to do a thorough evaluation and to identify any additional pieces of information that may be missing before a strong conclusion can be made. That said, however, this is the real world where everyone is busy and few have the time to track down every loose end that may exist regarding a patient’s history.

To that end, here are some recommendations for how to increase the chance that the outcome of your consultation with a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional will be maximally helpful for everyone involved. These tips are based on having been on the receiving end of psychiatric consultations for almost 2 decades and having worked closely with primary care clinicians in a number of different capacities.

The first question to ask yourself, and this may be the most important one of all, is whether or not you really need an actual psychiatrist at all at this stage versus another type of mental health professional. Physicians often are most comfortable dealing with other physicians. If a pediatrician has a question about a patient’s heart, it’s logical to consult a cardiologist. Thus if there’s a question about mental health, the knee-jerk reaction is to consult a psychiatrist. While understandable, looking first to a psychiatrist to help with a patient’s mental health struggles often is not the best move. Psychiatrists make up only one small part of all mental health professionals that also include psychologists, counselors, and clinical social workers, among others. The availability of child and adolescent psychiatrists can been exceedingly sparse while other types of mental health professionals generally are much more available. Moreover, these other types of mental health professionals also can do a great job at assessment and treatment. It is true that most can’t prescribe medication, but best practice recommendations for most of the common mental health diagnoses in youth (anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, etc.) explicitly outline that nonpharmacologic treatments should be used first. It breaks my heart every time I do a consult for a family who has waited 6 months only to have me recommend a good therapist they could have seen right off in a week.

Get to know the mental health resources of your community beyond the small number of psychiatrists who might be there. And if you aren’t sure whether or not a referral might best go first to a mental health professional who is not a psychiatrist, just ask. That quick phone call or email might save the family a needless delay in treatment and a lot of aggravation for you.

If you are confident that it is a child & adolescent psychiatrist you want your patient to see, here are some things that will help you get the most out of that consultation and help you avoid the disappointment (for both you and the family) of an evaluation that completely misses the mark.

Select the best site (if you have an option)

Broadly speaking, psychiatrists often can be found in three main areas: academic clinics, private practice, and community mental health centers. While of course there is huge variation of clinicians at each of the sites, some generalizations regarding typical advantages and disadvantages of each setting are probably fair.

Academic settings often have psychiatrists who are local or even national experts on particular topics and can be good places to get evaluations for patients with complicated histories. At the same time, however, these settings typically rely on trainees to do much of the actual work. Many of the residents and fellows are excellent, but they turn over quickly because of graduation and finishing rotations, which can force patients to get to know a lot of different people. Academic centers also can be quite a distance from a family’s home, which often makes follow-up care a challenge (especially when we go back to more in-person visits).

Private practice psychiatrists can provide a more local option and can give families access to experienced clinicians, but many of these practices (especially the ones that take insurance) have practice models that involve seeing a lot of patients for short amounts of time and with less coordination with other types of services.

Finally, psychiatrists working at community mental health centers often work in teams that can help families get access to a lot of useful ancillary services (case management, home supports, etc.) but are part of a public mental health system that sadly is all too often overstretched and underfunded.

If you have choices for where to go for psychiatric services, keeping these things in mind can help you find the best fit for families.

Provide a medication history

While I’m not a big fan of the “what medicine do I try next?” consultation, don’t rely on families to provide this information accurately. Medications are confusing, and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard: “I tried the little blue pill and then the big white capsule.” Nobody feels good if the end result of a long consultative process includes a recommendation for a medication that the patient has already tried and failed. Some EMRs now have this information in a way that can be more easily packaged and shared.

State what you are looking for

If you really want the psychiatrist to take over the care of the patient, are just looking for some guidance for what to do next, or are seeking a second opinion for a patient that already works with a psychiatrist, stating so specifically can help tailor the consultation to best address the situation.

Send along past evaluations

Many patients have accumulated detailed psychological or educational evaluations over time that can include some really important information like cognitive profiles, other diagnostic impressions, and past treatment recommendations that may or may not have been implemented. Having these available to the consulting psychiatrist (of course parents need to give permission to send these along) can help the consultant avoid asking redundant questions or recommend things that already have been tried.

Rule outs of medical causes

There are a lot of psychiatric symptoms that can be caused by nonpsychiatric causes. Sometimes, there can be an assumption on the part of the psychiatrist that the pediatrician already has evaluated for these possibilities while the pediatrician assumes that the psychiatrist will work those up if needed. This is how the care of some patients fall through the cracks, and how those unflattering stories of how patients were forced to live with undiagnosed ailments (seizures, encephalopathy, Lyme disease, etc.) for years are generated. Being clear what work-up and tests already have been done to look for other causes can help everyone involved decide what should be done next and who should do it.

Yes, it is true that most of the recommendations specified here involve more work that the quick “behavioral problems: eval and treat” note that may be tempting to write when consulting with a mental health professional, but they will help avoid a lot of headaches for you down the road and, most importantly, get patients and families the timely and comprehensive care they deserve.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rettew at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Pediatricians take on more mental health care

Assessment and treatment of many of the more common behavioral disorders in childhood, such as ADHD and anxiety, should be considered within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, a stance made very clear by a recent policy statement published by the American Academy of Pediatrics entitled “Mental health competencies for pediatric practice.”1 These competencies include medication treatment. As stated in the article, “certain disorders (ADHD, common anxiety disorders, depression), if associated with no more than moderate impairment, are amenable to primary care medication management because there are indicated medications with a well-established safety profile.”

This shift to shared ownership when it comes to mental health care is likely coming from multiple sources, not the least of them being necessity and an acknowledgment that there simply aren’t enough psychiatrists to take over the mental health care of every youth with a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. While the number of child and adolescent psychiatrists remains relatively flat, the youth suicide rate is rising, as are the numbers presenting to emergency departments in crisis – all for reasons still to be fully understood. And these trends all are occurring as the medical community overall is appreciating more and more that good mental health is a cornerstone of all health.

The response from the pediatric community, whether it be because of personal conviction or simply a lack of options, largely has been to step up to the plate and take on these new responsibilities and challenges while trying to get up to speed with the latest information about mental health best practices. From my own experience doing evaluations and consultations from area primary care clinicians for over 15 years, the shift is noticeable. The typical patient now coming in has already seen a mental health counselor and tried at least one medication, while evaluations for diagnosis and treatment recommendations for things like uncomplicated and treatment-naive ADHD symptoms, for example, are becoming much more infrequent – although still far from extinct.

Nevertheless, there remain concerns about the extent of these new charges. Joe Nasca, MD, an experienced pediatrician who has been practicing in rural Vermont for decades, is worried that there is simply too much already for pediatricians to know and do to be able to add extensive mental health care. “There is so much to know in general peds [pediatrics] that I would guess a year or more of additional residency and experience would adequately prepare me to take this on,” he said in an interview. In comparing psychiatric care to other specialties, Dr. Nasca went on to say that, “I would not presume to treat chronic renal failure without the help of a nephrologist or a dilated aortic arch without a cardiologist.”

In a similar vein, however, it also is true that a significant percentage of children presenting to pediatricians for orthopedic problems, infections, asthma, and rashes are managed without referrals to specialists. The right balance, of course, will vary from clinician to clinician based on that pediatrician’s level of interest, experience, and available resources in the community. The AAP position papers don’t mandate or even encourage the notion that all pediatricians need to be at the same place when it comes to competency in assessment and treatment of mental health problems, although it is probably fair to say that there is a push for the pediatric community as a whole to raise the collective bar at least a notch or two.

In response, the mental health community has moved to support the primary care community in their expanded role. These efforts have taken many forms, most notably the model of integrated care, in which mental health clinicians of various types see patients in primary care offices rather than making patients come to them. There also are new consultation programs that provide easy access to a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional for case-related questions delivered by phone, email, or for single in-person consultations. Additional training and educational offerings also are now available for pediatricians either in training and for those already in practice. These initiatives are bolstered by research showing that, not only can good mental health care be delivered in pediatric settings, but there are cost savings that can be realized, particularly for nonpsychiatric medical care.2 Despite these promising leads, however, there will remain some for whom anything less than the increased availability of a psychiatrist to “take over” a patient’s mental health care will be seen as a falling short of the clinical need.

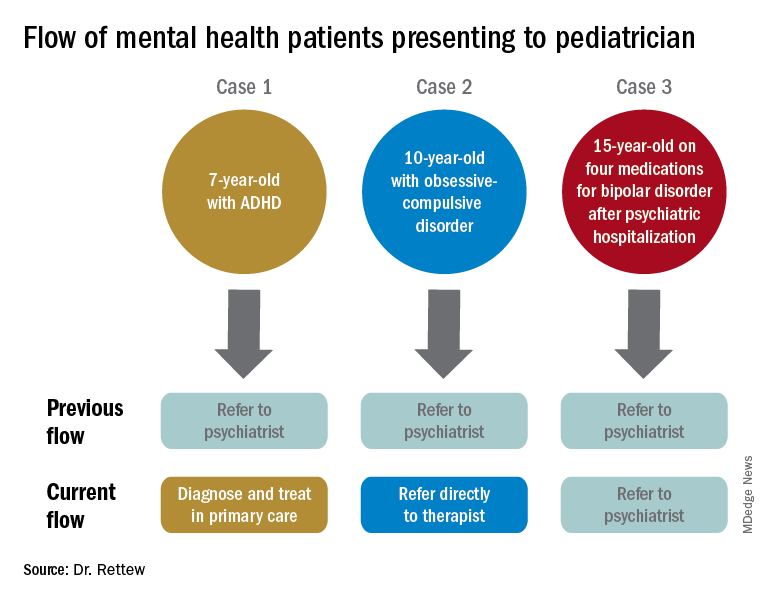

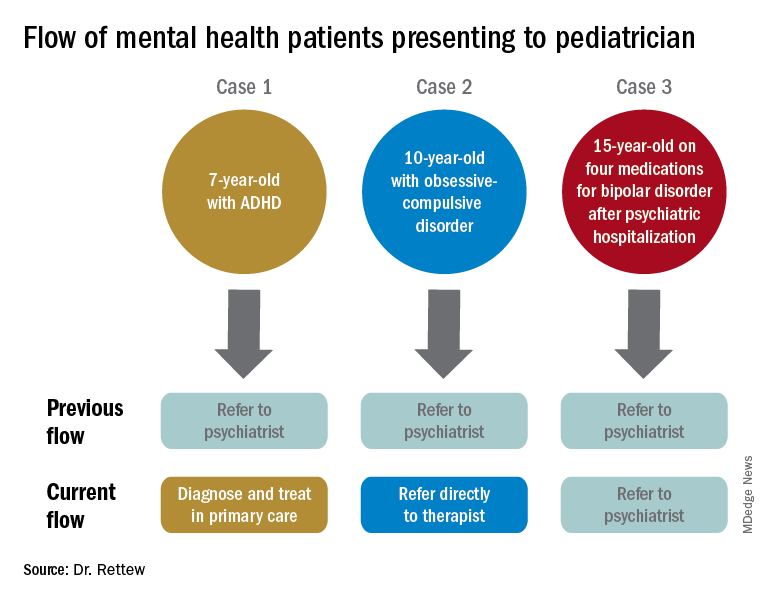

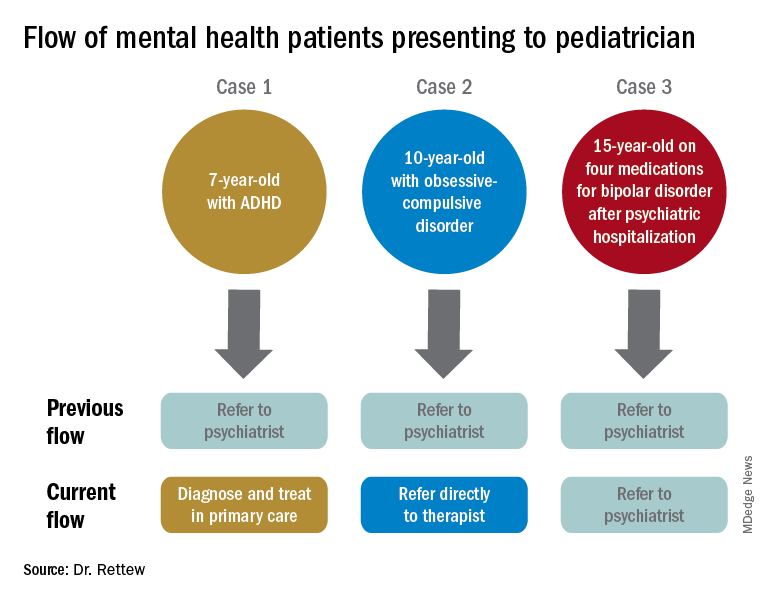

To illustrate how things have and continue to change, consider the following three common clinical scenarios that generally present to a pediatrician:

- New presentation of ADHD symptoms.

- Anxiety or obsessive-compulsive problems.

- Return of a patient who has been psychiatrically hospitalized and now is taking multiple medications.

In the past, all three cases often would have resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist. Today, however, it is quite likely that only one of these cases would be referred because ADHD could be well diagnosed and managed within the primary care setting, and problems like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder are sent first not to a psychiatrist but to a non-MD psychotherapist.

Moving forward, today’s pediatricians are expected to do more for the mental health care of patients themselves instead of referring to a psychiatrist. Most already do, despite having had little in the way of formal training. As the evidence grows that the promotion of mental well-being can be a key to future overall health, as well as to the cost of future health care, there are many reasons to be optimistic that support for pediatricians and collaborative care models for clinicians trying to fulfill these new responsibilities will get only stronger.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov;144(5). pii: e20192757.

2. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul;144(1). pii: e20183243.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 14th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington on May 8, 2020 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Assessment and treatment of many of the more common behavioral disorders in childhood, such as ADHD and anxiety, should be considered within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, a stance made very clear by a recent policy statement published by the American Academy of Pediatrics entitled “Mental health competencies for pediatric practice.”1 These competencies include medication treatment. As stated in the article, “certain disorders (ADHD, common anxiety disorders, depression), if associated with no more than moderate impairment, are amenable to primary care medication management because there are indicated medications with a well-established safety profile.”

This shift to shared ownership when it comes to mental health care is likely coming from multiple sources, not the least of them being necessity and an acknowledgment that there simply aren’t enough psychiatrists to take over the mental health care of every youth with a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. While the number of child and adolescent psychiatrists remains relatively flat, the youth suicide rate is rising, as are the numbers presenting to emergency departments in crisis – all for reasons still to be fully understood. And these trends all are occurring as the medical community overall is appreciating more and more that good mental health is a cornerstone of all health.

The response from the pediatric community, whether it be because of personal conviction or simply a lack of options, largely has been to step up to the plate and take on these new responsibilities and challenges while trying to get up to speed with the latest information about mental health best practices. From my own experience doing evaluations and consultations from area primary care clinicians for over 15 years, the shift is noticeable. The typical patient now coming in has already seen a mental health counselor and tried at least one medication, while evaluations for diagnosis and treatment recommendations for things like uncomplicated and treatment-naive ADHD symptoms, for example, are becoming much more infrequent – although still far from extinct.

Nevertheless, there remain concerns about the extent of these new charges. Joe Nasca, MD, an experienced pediatrician who has been practicing in rural Vermont for decades, is worried that there is simply too much already for pediatricians to know and do to be able to add extensive mental health care. “There is so much to know in general peds [pediatrics] that I would guess a year or more of additional residency and experience would adequately prepare me to take this on,” he said in an interview. In comparing psychiatric care to other specialties, Dr. Nasca went on to say that, “I would not presume to treat chronic renal failure without the help of a nephrologist or a dilated aortic arch without a cardiologist.”

In a similar vein, however, it also is true that a significant percentage of children presenting to pediatricians for orthopedic problems, infections, asthma, and rashes are managed without referrals to specialists. The right balance, of course, will vary from clinician to clinician based on that pediatrician’s level of interest, experience, and available resources in the community. The AAP position papers don’t mandate or even encourage the notion that all pediatricians need to be at the same place when it comes to competency in assessment and treatment of mental health problems, although it is probably fair to say that there is a push for the pediatric community as a whole to raise the collective bar at least a notch or two.

In response, the mental health community has moved to support the primary care community in their expanded role. These efforts have taken many forms, most notably the model of integrated care, in which mental health clinicians of various types see patients in primary care offices rather than making patients come to them. There also are new consultation programs that provide easy access to a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional for case-related questions delivered by phone, email, or for single in-person consultations. Additional training and educational offerings also are now available for pediatricians either in training and for those already in practice. These initiatives are bolstered by research showing that, not only can good mental health care be delivered in pediatric settings, but there are cost savings that can be realized, particularly for nonpsychiatric medical care.2 Despite these promising leads, however, there will remain some for whom anything less than the increased availability of a psychiatrist to “take over” a patient’s mental health care will be seen as a falling short of the clinical need.

To illustrate how things have and continue to change, consider the following three common clinical scenarios that generally present to a pediatrician:

- New presentation of ADHD symptoms.

- Anxiety or obsessive-compulsive problems.

- Return of a patient who has been psychiatrically hospitalized and now is taking multiple medications.

In the past, all three cases often would have resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist. Today, however, it is quite likely that only one of these cases would be referred because ADHD could be well diagnosed and managed within the primary care setting, and problems like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder are sent first not to a psychiatrist but to a non-MD psychotherapist.

Moving forward, today’s pediatricians are expected to do more for the mental health care of patients themselves instead of referring to a psychiatrist. Most already do, despite having had little in the way of formal training. As the evidence grows that the promotion of mental well-being can be a key to future overall health, as well as to the cost of future health care, there are many reasons to be optimistic that support for pediatricians and collaborative care models for clinicians trying to fulfill these new responsibilities will get only stronger.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov;144(5). pii: e20192757.

2. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul;144(1). pii: e20183243.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 14th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington on May 8, 2020 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Assessment and treatment of many of the more common behavioral disorders in childhood, such as ADHD and anxiety, should be considered within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, a stance made very clear by a recent policy statement published by the American Academy of Pediatrics entitled “Mental health competencies for pediatric practice.”1 These competencies include medication treatment. As stated in the article, “certain disorders (ADHD, common anxiety disorders, depression), if associated with no more than moderate impairment, are amenable to primary care medication management because there are indicated medications with a well-established safety profile.”

This shift to shared ownership when it comes to mental health care is likely coming from multiple sources, not the least of them being necessity and an acknowledgment that there simply aren’t enough psychiatrists to take over the mental health care of every youth with a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. While the number of child and adolescent psychiatrists remains relatively flat, the youth suicide rate is rising, as are the numbers presenting to emergency departments in crisis – all for reasons still to be fully understood. And these trends all are occurring as the medical community overall is appreciating more and more that good mental health is a cornerstone of all health.

The response from the pediatric community, whether it be because of personal conviction or simply a lack of options, largely has been to step up to the plate and take on these new responsibilities and challenges while trying to get up to speed with the latest information about mental health best practices. From my own experience doing evaluations and consultations from area primary care clinicians for over 15 years, the shift is noticeable. The typical patient now coming in has already seen a mental health counselor and tried at least one medication, while evaluations for diagnosis and treatment recommendations for things like uncomplicated and treatment-naive ADHD symptoms, for example, are becoming much more infrequent – although still far from extinct.

Nevertheless, there remain concerns about the extent of these new charges. Joe Nasca, MD, an experienced pediatrician who has been practicing in rural Vermont for decades, is worried that there is simply too much already for pediatricians to know and do to be able to add extensive mental health care. “There is so much to know in general peds [pediatrics] that I would guess a year or more of additional residency and experience would adequately prepare me to take this on,” he said in an interview. In comparing psychiatric care to other specialties, Dr. Nasca went on to say that, “I would not presume to treat chronic renal failure without the help of a nephrologist or a dilated aortic arch without a cardiologist.”

In a similar vein, however, it also is true that a significant percentage of children presenting to pediatricians for orthopedic problems, infections, asthma, and rashes are managed without referrals to specialists. The right balance, of course, will vary from clinician to clinician based on that pediatrician’s level of interest, experience, and available resources in the community. The AAP position papers don’t mandate or even encourage the notion that all pediatricians need to be at the same place when it comes to competency in assessment and treatment of mental health problems, although it is probably fair to say that there is a push for the pediatric community as a whole to raise the collective bar at least a notch or two.

In response, the mental health community has moved to support the primary care community in their expanded role. These efforts have taken many forms, most notably the model of integrated care, in which mental health clinicians of various types see patients in primary care offices rather than making patients come to them. There also are new consultation programs that provide easy access to a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional for case-related questions delivered by phone, email, or for single in-person consultations. Additional training and educational offerings also are now available for pediatricians either in training and for those already in practice. These initiatives are bolstered by research showing that, not only can good mental health care be delivered in pediatric settings, but there are cost savings that can be realized, particularly for nonpsychiatric medical care.2 Despite these promising leads, however, there will remain some for whom anything less than the increased availability of a psychiatrist to “take over” a patient’s mental health care will be seen as a falling short of the clinical need.

To illustrate how things have and continue to change, consider the following three common clinical scenarios that generally present to a pediatrician:

- New presentation of ADHD symptoms.

- Anxiety or obsessive-compulsive problems.

- Return of a patient who has been psychiatrically hospitalized and now is taking multiple medications.

In the past, all three cases often would have resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist. Today, however, it is quite likely that only one of these cases would be referred because ADHD could be well diagnosed and managed within the primary care setting, and problems like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder are sent first not to a psychiatrist but to a non-MD psychotherapist.

Moving forward, today’s pediatricians are expected to do more for the mental health care of patients themselves instead of referring to a psychiatrist. Most already do, despite having had little in the way of formal training. As the evidence grows that the promotion of mental well-being can be a key to future overall health, as well as to the cost of future health care, there are many reasons to be optimistic that support for pediatricians and collaborative care models for clinicians trying to fulfill these new responsibilities will get only stronger.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov;144(5). pii: e20192757.

2. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul;144(1). pii: e20183243.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 14th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington on May 8, 2020 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Consider caffeine effects on children and adolescents

Less clinical attention has been paid to caffeine lately as the medical community works to overcome the negative effects of substances such as opiates and cannabis. Quietly, however, caffeine continues to be widely consumed among children and adolescents, and its use often flies under the radar for pediatricians who have so many other topics to address. To help clinicians decide whether more focus on caffeine use is needed, a review was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2019;58[1]:36-45). A synopsis of this paper which summarizes 90 individual studies on caffeine use in children and adolescents is provided here.

Caffeine usage in children and adolescents

Caffeine continues to be one of the most commonly used substances in youth, with about 75% of older children and adolescents consuming it regularly, often at an average dose of about 25 mg/day for children aged 6-11 years and 50 mg/day for adolescents. Because most people have trouble quickly converting commonly used products into milligrams of caffeine, the following guide can be useful:

- Soda (12 oz). About 40 mg caffeine.

- Coffee (8 oz). About 100 mg caffeine.

- Tea (8 oz). About 48 mg caffeine.

- Energy drinks (12 oz). About 150 mg caffeine plus, with 5-Hour Energy being around 215 mg caffeine, according to a Consumer Reports study.

It is important to pay attention to the serving size, as the actual volume consumed of products like coffee or soft drinks often are much higher.

With regards to caffeine trends over time, a surprising observation is that total caffeine consumption among youth over the past decade or so looks relatively flat and may even be decreasing. This trend has occurred despite the aggressive marketing to youth of many energy drinks that contain high amounts of caffeine. In many ways, the pattern of caffeine use fits with what we know about substance use in general in adolescents, with rates dropping for many commonly used substances – with the exception of cannabis.

Effects of caffeine

As many know, caffeine is a stimulant and is known to increase arousal, alertness, and amount of motor behavior. While many youth drink caffeine in an effort to improve cognitive performance, the evidence that it does so directly is modest. There are some studies that show improvements on some cognitive tests when children take moderate doses of caffeine, but these effects tend to be most pronounced for kids who are more naive to caffeine at baseline. Of course, caffeine also can temporarily reduce feelings of fatigue and sleepiness.

Anecdotally, many youth and parents will report that caffeine is a way to “self-medicate” various symptoms of ADHD. While many will report some benefit, there is a surprising lack of rigorous data about the effects of caffeine for youth who meet criteria for ADHD, according to this review.

There also are some well-known negative effects of caffeine use. One of the most important ones is that caffeine can interfere with sleep onset, thereby inducing a cycle that reinforces more caffeine use in the day in an effort to compensate for poor sleep at night. A less obvious negative effect that has been documented is that caffeine added to sweetened beverages can increase consumption of similar sugary foods, even if they don’t have caffeine.

A number of adverse effects have been observed when youth consume caffeine at excessive doses, which tend to be around a threshold of 400 mg/day for teens and about 100 mg/day for younger children. These can include both behavioral and nonbehavioral changes such as agitation or irritability, anxiety, heart arrhythmias, and hypertension. Concern over high caffeine intake also was raised in relation to a number of cases of sudden death, although these events fortunately are rare. The review mentions that one factor that could increase the risk of a serious medical event related to caffeine use is the presence of an underlying cardiac problem which may go undetected until a negative outcome occurs. In thinking about these risks associated with “excessive” caffeine consumption, it can be important to go back to the guides and see just how easily an adolescent can get to a level of 400 mg or more. A couple large cups of coffee per day or two to three specific “energy-boosting” products can be all that it takes.

There also are a few large longitudinal studies that have shown a significant association between increased caffeine consumption and future problems with anger, aggression, risky sexual behavior, and substance use. Energy drinks, which can deliver a lot of caffeine quickly, were singled out as particularly problematic in some of these studies, although these naturalistic studies are unable to determine causation, and it also is possible that teens who are already prone towards behavioral problems tend to consume more caffeine. However, the review also mentions animal studies that have demonstrated that caffeine may prime the brain to use other substances like amphetamines or cocaine. Finally, another concern raised about energy drinks in particular is that they also often contain other substances which may have similar physiological effects but are relatively untested when it comes to safety.

Conclusions

This review, like the current position of the Food and Drug Administration, considers caffeine as generally safe at low doses because there does not appear to be much evidence that low or moderate use in youth leads to significant problems. The conclusion changes, however, with higher levels of consumption, as more frequent and more serious risks are encountered. The article recommends that both parents and doctors be more vigilant in monitoring the amount of caffeine that a child consumes as well as the timing of that use during the day. Some quick calculations can be done to give adolescents and their parents an estimate of their caffeine use in milligrams. And while caffeine may not rise to the level of public health concern as substances like opiates or alcohol, there is evidence that it can cause some real problems in children and teens, especially in higher amounts, and thus shouldn’t be given a total pass by parents and doctors alike.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 13th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, Vt., May 3, 2019 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Less clinical attention has been paid to caffeine lately as the medical community works to overcome the negative effects of substances such as opiates and cannabis. Quietly, however, caffeine continues to be widely consumed among children and adolescents, and its use often flies under the radar for pediatricians who have so many other topics to address. To help clinicians decide whether more focus on caffeine use is needed, a review was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2019;58[1]:36-45). A synopsis of this paper which summarizes 90 individual studies on caffeine use in children and adolescents is provided here.

Caffeine usage in children and adolescents

Caffeine continues to be one of the most commonly used substances in youth, with about 75% of older children and adolescents consuming it regularly, often at an average dose of about 25 mg/day for children aged 6-11 years and 50 mg/day for adolescents. Because most people have trouble quickly converting commonly used products into milligrams of caffeine, the following guide can be useful:

- Soda (12 oz). About 40 mg caffeine.

- Coffee (8 oz). About 100 mg caffeine.

- Tea (8 oz). About 48 mg caffeine.

- Energy drinks (12 oz). About 150 mg caffeine plus, with 5-Hour Energy being around 215 mg caffeine, according to a Consumer Reports study.

It is important to pay attention to the serving size, as the actual volume consumed of products like coffee or soft drinks often are much higher.

With regards to caffeine trends over time, a surprising observation is that total caffeine consumption among youth over the past decade or so looks relatively flat and may even be decreasing. This trend has occurred despite the aggressive marketing to youth of many energy drinks that contain high amounts of caffeine. In many ways, the pattern of caffeine use fits with what we know about substance use in general in adolescents, with rates dropping for many commonly used substances – with the exception of cannabis.

Effects of caffeine

As many know, caffeine is a stimulant and is known to increase arousal, alertness, and amount of motor behavior. While many youth drink caffeine in an effort to improve cognitive performance, the evidence that it does so directly is modest. There are some studies that show improvements on some cognitive tests when children take moderate doses of caffeine, but these effects tend to be most pronounced for kids who are more naive to caffeine at baseline. Of course, caffeine also can temporarily reduce feelings of fatigue and sleepiness.

Anecdotally, many youth and parents will report that caffeine is a way to “self-medicate” various symptoms of ADHD. While many will report some benefit, there is a surprising lack of rigorous data about the effects of caffeine for youth who meet criteria for ADHD, according to this review.

There also are some well-known negative effects of caffeine use. One of the most important ones is that caffeine can interfere with sleep onset, thereby inducing a cycle that reinforces more caffeine use in the day in an effort to compensate for poor sleep at night. A less obvious negative effect that has been documented is that caffeine added to sweetened beverages can increase consumption of similar sugary foods, even if they don’t have caffeine.

A number of adverse effects have been observed when youth consume caffeine at excessive doses, which tend to be around a threshold of 400 mg/day for teens and about 100 mg/day for younger children. These can include both behavioral and nonbehavioral changes such as agitation or irritability, anxiety, heart arrhythmias, and hypertension. Concern over high caffeine intake also was raised in relation to a number of cases of sudden death, although these events fortunately are rare. The review mentions that one factor that could increase the risk of a serious medical event related to caffeine use is the presence of an underlying cardiac problem which may go undetected until a negative outcome occurs. In thinking about these risks associated with “excessive” caffeine consumption, it can be important to go back to the guides and see just how easily an adolescent can get to a level of 400 mg or more. A couple large cups of coffee per day or two to three specific “energy-boosting” products can be all that it takes.

There also are a few large longitudinal studies that have shown a significant association between increased caffeine consumption and future problems with anger, aggression, risky sexual behavior, and substance use. Energy drinks, which can deliver a lot of caffeine quickly, were singled out as particularly problematic in some of these studies, although these naturalistic studies are unable to determine causation, and it also is possible that teens who are already prone towards behavioral problems tend to consume more caffeine. However, the review also mentions animal studies that have demonstrated that caffeine may prime the brain to use other substances like amphetamines or cocaine. Finally, another concern raised about energy drinks in particular is that they also often contain other substances which may have similar physiological effects but are relatively untested when it comes to safety.

Conclusions

This review, like the current position of the Food and Drug Administration, considers caffeine as generally safe at low doses because there does not appear to be much evidence that low or moderate use in youth leads to significant problems. The conclusion changes, however, with higher levels of consumption, as more frequent and more serious risks are encountered. The article recommends that both parents and doctors be more vigilant in monitoring the amount of caffeine that a child consumes as well as the timing of that use during the day. Some quick calculations can be done to give adolescents and their parents an estimate of their caffeine use in milligrams. And while caffeine may not rise to the level of public health concern as substances like opiates or alcohol, there is evidence that it can cause some real problems in children and teens, especially in higher amounts, and thus shouldn’t be given a total pass by parents and doctors alike.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 13th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, Vt., May 3, 2019 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Less clinical attention has been paid to caffeine lately as the medical community works to overcome the negative effects of substances such as opiates and cannabis. Quietly, however, caffeine continues to be widely consumed among children and adolescents, and its use often flies under the radar for pediatricians who have so many other topics to address. To help clinicians decide whether more focus on caffeine use is needed, a review was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2019;58[1]:36-45). A synopsis of this paper which summarizes 90 individual studies on caffeine use in children and adolescents is provided here.

Caffeine usage in children and adolescents

Caffeine continues to be one of the most commonly used substances in youth, with about 75% of older children and adolescents consuming it regularly, often at an average dose of about 25 mg/day for children aged 6-11 years and 50 mg/day for adolescents. Because most people have trouble quickly converting commonly used products into milligrams of caffeine, the following guide can be useful:

- Soda (12 oz). About 40 mg caffeine.

- Coffee (8 oz). About 100 mg caffeine.

- Tea (8 oz). About 48 mg caffeine.

- Energy drinks (12 oz). About 150 mg caffeine plus, with 5-Hour Energy being around 215 mg caffeine, according to a Consumer Reports study.

It is important to pay attention to the serving size, as the actual volume consumed of products like coffee or soft drinks often are much higher.

With regards to caffeine trends over time, a surprising observation is that total caffeine consumption among youth over the past decade or so looks relatively flat and may even be decreasing. This trend has occurred despite the aggressive marketing to youth of many energy drinks that contain high amounts of caffeine. In many ways, the pattern of caffeine use fits with what we know about substance use in general in adolescents, with rates dropping for many commonly used substances – with the exception of cannabis.

Effects of caffeine

As many know, caffeine is a stimulant and is known to increase arousal, alertness, and amount of motor behavior. While many youth drink caffeine in an effort to improve cognitive performance, the evidence that it does so directly is modest. There are some studies that show improvements on some cognitive tests when children take moderate doses of caffeine, but these effects tend to be most pronounced for kids who are more naive to caffeine at baseline. Of course, caffeine also can temporarily reduce feelings of fatigue and sleepiness.

Anecdotally, many youth and parents will report that caffeine is a way to “self-medicate” various symptoms of ADHD. While many will report some benefit, there is a surprising lack of rigorous data about the effects of caffeine for youth who meet criteria for ADHD, according to this review.

There also are some well-known negative effects of caffeine use. One of the most important ones is that caffeine can interfere with sleep onset, thereby inducing a cycle that reinforces more caffeine use in the day in an effort to compensate for poor sleep at night. A less obvious negative effect that has been documented is that caffeine added to sweetened beverages can increase consumption of similar sugary foods, even if they don’t have caffeine.

A number of adverse effects have been observed when youth consume caffeine at excessive doses, which tend to be around a threshold of 400 mg/day for teens and about 100 mg/day for younger children. These can include both behavioral and nonbehavioral changes such as agitation or irritability, anxiety, heart arrhythmias, and hypertension. Concern over high caffeine intake also was raised in relation to a number of cases of sudden death, although these events fortunately are rare. The review mentions that one factor that could increase the risk of a serious medical event related to caffeine use is the presence of an underlying cardiac problem which may go undetected until a negative outcome occurs. In thinking about these risks associated with “excessive” caffeine consumption, it can be important to go back to the guides and see just how easily an adolescent can get to a level of 400 mg or more. A couple large cups of coffee per day or two to three specific “energy-boosting” products can be all that it takes.

There also are a few large longitudinal studies that have shown a significant association between increased caffeine consumption and future problems with anger, aggression, risky sexual behavior, and substance use. Energy drinks, which can deliver a lot of caffeine quickly, were singled out as particularly problematic in some of these studies, although these naturalistic studies are unable to determine causation, and it also is possible that teens who are already prone towards behavioral problems tend to consume more caffeine. However, the review also mentions animal studies that have demonstrated that caffeine may prime the brain to use other substances like amphetamines or cocaine. Finally, another concern raised about energy drinks in particular is that they also often contain other substances which may have similar physiological effects but are relatively untested when it comes to safety.

Conclusions

This review, like the current position of the Food and Drug Administration, considers caffeine as generally safe at low doses because there does not appear to be much evidence that low or moderate use in youth leads to significant problems. The conclusion changes, however, with higher levels of consumption, as more frequent and more serious risks are encountered. The article recommends that both parents and doctors be more vigilant in monitoring the amount of caffeine that a child consumes as well as the timing of that use during the day. Some quick calculations can be done to give adolescents and their parents an estimate of their caffeine use in milligrams. And while caffeine may not rise to the level of public health concern as substances like opiates or alcohol, there is evidence that it can cause some real problems in children and teens, especially in higher amounts, and thus shouldn’t be given a total pass by parents and doctors alike.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 13th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, Vt., May 3, 2019 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Anxiety disorders: Psychopharmacologic treatment update

Anxiety disorders, including separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, are some of the most common psychiatric conditions of childhood and adolescence, affecting up to 20% of youth.1 Patients commonly present with a mix of symptoms that often span multiple anxiety disorder diagnoses. While this pattern can present somewhat of a diagnostic conundrum, it can be reassuring to know that such constellations of symptoms are the rule rather than the exception. Further, given that both the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment strategies don’t change much among the various anxiety disorders, the lack of a definitive single diagnosis should not delay intervention. Be alert to the possibility that anxiety and anxiety disorders can be the engine that drives what on the surface appears to be more disruptive and oppositional behavior.

Although medications can be a useful part of treatment, they are not recommended as a stand-alone intervention. Nonpharmacologic treatments generally should be tried before medications are considered. Among the different types of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the most empirical support from research trials, although other modalities such as mindfulness-based treatments show some promise. As anxiety disorders often run in families, it also can be very useful to explore the possibility that one or more parents also struggle with an anxiety disorder, which, if untreated, might complicate the child’s course.

With regard to medications, it is being increasingly appreciated that, despite SSRIs being most popularly known as antidepressants, these medications actually may be as efficacious or even more efficacious in the management of anxiety disorders. This class remains the cornerstone of medication treatment, and a brief review of current options follows.

SSRIs and SNRIs

A 2015 meta-analysis that examined nine randomized controlled trials of SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for pediatric anxiety disorders concluded that these agents provided a benefit of modest effect size. No significant increase in treatment-emergent suicidality was found, and the medications were generally well tolerated.2 This analysis also found some evidence that greater efficacy was related to a medication with more specific serotonergic properties, suggesting improved response with “true” SSRIs versus SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine. One major study using sertraline found that, at least in the short term, combined use of sertraline with CBT resulted in better efficacy than either treatment alone.3 Dosing of SSRIs should start low: A general rule is to begin at half of the smallest dosage made, depending on the age and size of the patient. One question that often comes up after a successful trial is how long to continue the medications. A recent meta-analysis in adults concluded that there was evidence that stopping medication prior to 1 year resulted in an increased risk of relapse with little to guide clinicians after that 1-year mark.4

Benzodiazepines

Even though benzodiazepines have been around for a long time, data supporting their efficacy and safety in pediatric populations remain extremely limited, and what has been reported has not been particularly positive. Thus, most experts do not suggest using benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders, with the exception of helping children through single or rare events, such as medical procedures or enabling an adolescent who has been fearful of attending school to get to the building on the first day back after a long absence.

Guanfacine

In a recent exploratory trial of guanfacine for children with mixed anxiety disorders,5 the medication was well tolerated overall but did not result in statistically significant improvement relative to placebo on primary anxiety rating scales. However, a higher number of children were rated as improved on a clinician-rated scale. This medication is usually started at 0.5 mg/day and increased as tolerated, while checking vital signs, to a maximum of 4 mg/day.

Atomoxetine

A randomized control trial of pediatric patients with both ADHD and an anxiety disorder showed reductions in both symptom domains with atomoxetine dosed at an average of 1.3 mg/kg per day.6 There is little evidence to suggest its use in primary anxiety disorders without comorbid ADHD.

Buspirone

This 5-hydroxytryptamine 1a agonist has Food and Drug Administration approval for generalized anxiety disorder in adults and is generally well tolerated. Unfortunately, two randomized controlled studies in children and adolescents did not find statistically significant improvement relative to placebo, although some methodological problems may have played a role.7

Antipsychotics

Although sometimes used to augment an SSRI in adult anxiety disorders, there are little data to support the use of antipsychotics in pediatric populations, especially given the antecedent risks of the drugs.

Summary

Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders often includes the advice that, if medications are indicated in conjunction with psychotherapy, to start with an SSRI; and if that is not effective to try a different one.7 An SNRI such as venlafaxine or duloxetine may then be a third-line alternative, although for youth with comorbid ADHD, consideration of either atomoxetine or guanfacine is also reasonable. Beyond that point, there unfortunately are little systematic data to guide pharmacologic decision making, and increased potential risks of other classes of medications suggest the need for caution and consultation.

Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 12th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, on May 4, 2018,organized by the University of Vermont with Dr. Rettew as course director. Go to http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences.

References

1. Merikangas KR et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;49(10):980-9.

2. Strawn JR et al. Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32(3):149-57.

3. Walkup J et al. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 25;359(26):2753-66.

4. Batelaan N et al. BMJ. 2017 Sep 13;358:j3927.

5. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;27(1): 29-37..

6. Geller D et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;46(9):1119-27.

7. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;28(1): 2-9.

Anxiety disorders, including separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, are some of the most common psychiatric conditions of childhood and adolescence, affecting up to 20% of youth.1 Patients commonly present with a mix of symptoms that often span multiple anxiety disorder diagnoses. While this pattern can present somewhat of a diagnostic conundrum, it can be reassuring to know that such constellations of symptoms are the rule rather than the exception. Further, given that both the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment strategies don’t change much among the various anxiety disorders, the lack of a definitive single diagnosis should not delay intervention. Be alert to the possibility that anxiety and anxiety disorders can be the engine that drives what on the surface appears to be more disruptive and oppositional behavior.

Although medications can be a useful part of treatment, they are not recommended as a stand-alone intervention. Nonpharmacologic treatments generally should be tried before medications are considered. Among the different types of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the most empirical support from research trials, although other modalities such as mindfulness-based treatments show some promise. As anxiety disorders often run in families, it also can be very useful to explore the possibility that one or more parents also struggle with an anxiety disorder, which, if untreated, might complicate the child’s course.

With regard to medications, it is being increasingly appreciated that, despite SSRIs being most popularly known as antidepressants, these medications actually may be as efficacious or even more efficacious in the management of anxiety disorders. This class remains the cornerstone of medication treatment, and a brief review of current options follows.

SSRIs and SNRIs

A 2015 meta-analysis that examined nine randomized controlled trials of SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for pediatric anxiety disorders concluded that these agents provided a benefit of modest effect size. No significant increase in treatment-emergent suicidality was found, and the medications were generally well tolerated.2 This analysis also found some evidence that greater efficacy was related to a medication with more specific serotonergic properties, suggesting improved response with “true” SSRIs versus SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine. One major study using sertraline found that, at least in the short term, combined use of sertraline with CBT resulted in better efficacy than either treatment alone.3 Dosing of SSRIs should start low: A general rule is to begin at half of the smallest dosage made, depending on the age and size of the patient. One question that often comes up after a successful trial is how long to continue the medications. A recent meta-analysis in adults concluded that there was evidence that stopping medication prior to 1 year resulted in an increased risk of relapse with little to guide clinicians after that 1-year mark.4

Benzodiazepines

Even though benzodiazepines have been around for a long time, data supporting their efficacy and safety in pediatric populations remain extremely limited, and what has been reported has not been particularly positive. Thus, most experts do not suggest using benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders, with the exception of helping children through single or rare events, such as medical procedures or enabling an adolescent who has been fearful of attending school to get to the building on the first day back after a long absence.

Guanfacine

In a recent exploratory trial of guanfacine for children with mixed anxiety disorders,5 the medication was well tolerated overall but did not result in statistically significant improvement relative to placebo on primary anxiety rating scales. However, a higher number of children were rated as improved on a clinician-rated scale. This medication is usually started at 0.5 mg/day and increased as tolerated, while checking vital signs, to a maximum of 4 mg/day.

Atomoxetine

A randomized control trial of pediatric patients with both ADHD and an anxiety disorder showed reductions in both symptom domains with atomoxetine dosed at an average of 1.3 mg/kg per day.6 There is little evidence to suggest its use in primary anxiety disorders without comorbid ADHD.

Buspirone

This 5-hydroxytryptamine 1a agonist has Food and Drug Administration approval for generalized anxiety disorder in adults and is generally well tolerated. Unfortunately, two randomized controlled studies in children and adolescents did not find statistically significant improvement relative to placebo, although some methodological problems may have played a role.7

Antipsychotics

Although sometimes used to augment an SSRI in adult anxiety disorders, there are little data to support the use of antipsychotics in pediatric populations, especially given the antecedent risks of the drugs.

Summary

Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders often includes the advice that, if medications are indicated in conjunction with psychotherapy, to start with an SSRI; and if that is not effective to try a different one.7 An SNRI such as venlafaxine or duloxetine may then be a third-line alternative, although for youth with comorbid ADHD, consideration of either atomoxetine or guanfacine is also reasonable. Beyond that point, there unfortunately are little systematic data to guide pharmacologic decision making, and increased potential risks of other classes of medications suggest the need for caution and consultation.

Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 12th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, on May 4, 2018,organized by the University of Vermont with Dr. Rettew as course director. Go to http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences.

References

1. Merikangas KR et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;49(10):980-9.

2. Strawn JR et al. Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32(3):149-57.

3. Walkup J et al. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 25;359(26):2753-66.

4. Batelaan N et al. BMJ. 2017 Sep 13;358:j3927.

5. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;27(1): 29-37..

6. Geller D et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;46(9):1119-27.

7. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;28(1): 2-9.

Anxiety disorders, including separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, are some of the most common psychiatric conditions of childhood and adolescence, affecting up to 20% of youth.1 Patients commonly present with a mix of symptoms that often span multiple anxiety disorder diagnoses. While this pattern can present somewhat of a diagnostic conundrum, it can be reassuring to know that such constellations of symptoms are the rule rather than the exception. Further, given that both the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment strategies don’t change much among the various anxiety disorders, the lack of a definitive single diagnosis should not delay intervention. Be alert to the possibility that anxiety and anxiety disorders can be the engine that drives what on the surface appears to be more disruptive and oppositional behavior.

Although medications can be a useful part of treatment, they are not recommended as a stand-alone intervention. Nonpharmacologic treatments generally should be tried before medications are considered. Among the different types of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the most empirical support from research trials, although other modalities such as mindfulness-based treatments show some promise. As anxiety disorders often run in families, it also can be very useful to explore the possibility that one or more parents also struggle with an anxiety disorder, which, if untreated, might complicate the child’s course.

With regard to medications, it is being increasingly appreciated that, despite SSRIs being most popularly known as antidepressants, these medications actually may be as efficacious or even more efficacious in the management of anxiety disorders. This class remains the cornerstone of medication treatment, and a brief review of current options follows.

SSRIs and SNRIs